Agenda for an American Renewal

Imperative for a Renewed Economic Paradigm

So far, President Trump’s tariff policies have generated significant turbulence and appear to lack a coherent strategy. His original tariff schedule included punitive tariffs on friends and foes alike on the mistaken basis that trade deficits are necessarily the result of an unhealthy relationship. Although they have been gradually paused or reduced since April 2, the uneven rollout (and subsequent rollback) of tariffs continues to generate tremendous uncertainty for policymakers, consumers, and businesses alike. This process has weakened America’s geopolitical standing by encouraging other countries to seek alternative trade, financial, and defense arrangements.

However, notwithstanding the uncoordinated approach to date, President Trump’s mistaken instinct for protectionism belies an underlying truth: that American manufacturing communities have not fared well in the last 25 years and that China’s dominance in manufacturing poses an ever-growing threat to national security. After China’s admission to the WTO in 2001, its share of global manufacturing grew from less than 10% to over 35% today. At the same time, America’s share of manufacturing shrank from almost 25% to less than 15%, with employment shrinking from more than 17 million at the turn of the century to under 13 million today. These trends also create a deep geopolitical vulnerability for America, as in the event of a conflict with China, we would be severely outmatched in our ability to build critical physical goods: for example, China produces over 80% of the world’s batteries, over 90% of consumer drones, and has a 200:1 shipbuilding capacity advantage over the U.S. While not all manufacturing is geopolitically valuable, the erosion in strategic industries, which went hand-in-hand with the loss of key manufacturing skills in recent decades, poses potential long-term challenges for America.

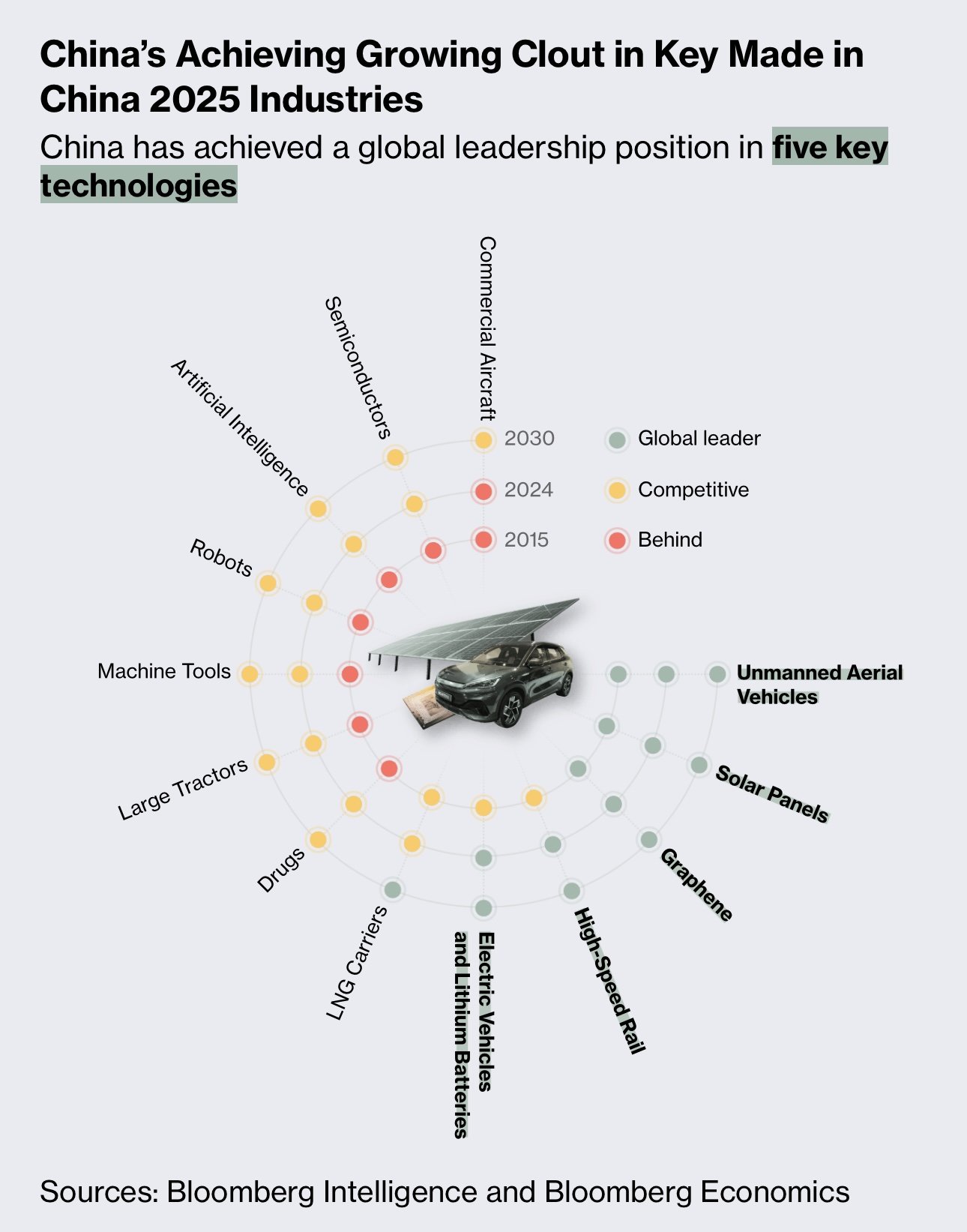

In addition to its growing manufacturing dominance, China is now competing with America’s preeminence in technology leadership, having leveraged many of the skills gained in science, engineering, and manufacturing for lower-value add industries to compete in higher-end sectors. DeepSeek demonstrated that China can natively generate high-quality artificial intelligence models, an area in which the U.S. took its lead for granted. Meanwhile, BYD rocketed past Tesla in EV sales and accounted for 22% of global sales in 2024 as compared to Tesla’s 10%. China has also been operating an extensive satellite-enabled secure quantum communications channel since 2016, preventing others from eavesdropping.

China’s growing leadership in advanced research may give it a sustained edge beyond its initial gains: according to one recent analysis of frontier research publications across 64 critical technologies, global leadership has shifted dramatically to China, which now leads in 57 research domains. These are not recent developments: they have been part of a series of five year plans, the most well known of which is Made in China 2025, giving China an edge in many critical technologies that will continue to grow if not addressed by an equally determined American response.

An Integrated Innovation, Economic Foreign Policy, and Community Development Approach

Despite China’s growing challenge and recent self-inflicted damage to America’s economic and geopolitical relationships, America still retains many ingrained advantages. The U.S. still has the largest economy, the deepest public and private capital pools for promising companies and technologies, and the world’s leading universities; it has the most advanced military, continues to count most of the world’s other leading armed forces as formal treaty allies, and remains the global reserve currency. Ordinary Americans have benefited greatly from these advantages in the form of access to cutting edge products and cheaper goods that increase their effective purchasing power and quality of life – notwithstanding Secretary Bessent’s statements to the contrary.

The U.S. would be wise to leverage its privileged position in high-end innovation and in global financial markets to build “industries of the future.” However, the next economic and geopolitical paradigm must be genuinely equitable, especially to domestic communities that have been previously neglected or harmed by globalization. For these communities, policies such as the now-defunct Trade Adjustment Assistance program were too slow and too reactive to help workers displaced by the “China Shock,” which is estimated to have caused up to 2.4 million direct and indirect job losses.

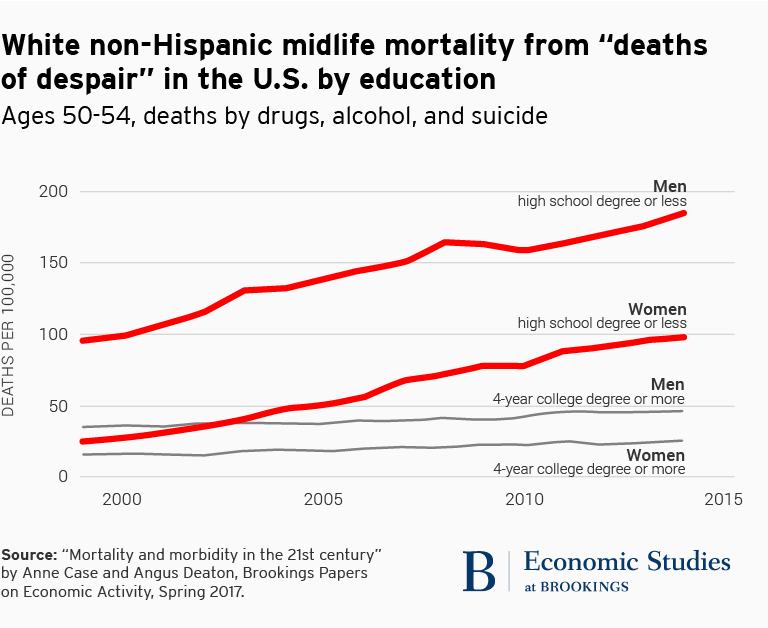

Although jobs in trade-affected communities were eventually “replaced,” the jobs that came after were disproportionately lower-earning roles, accrued largely to individuals who had college degrees, and were taken by new labor force entrants rather than providing new opportunities for those who had originally been displaced. Moreover, as a result of ineffective policy responses, this replacement took over a decade and has contributed to heinous effects: look no further than the rate at which “deaths of despair” for white individuals without a college degree skyrocketed after 2000.

Nonetheless, surrendering America’s hard-won advantages in technology and international commerce, especially in the face of a growing challenge from China, would be an existential error. Rather, our goal is to address the shortcomings of previous policy approaches to the negative externalities caused by globalization. Previous approaches have focused on maximizing growth and redistributing the gains, but in practice, America failed to do either by underinvesting in the foundational policies that enable both. Thus, we are proposing a two-pronged approach that focuses on spurring cutting-edge technologies, growing novel industries, and enhancing production capabilities while investing in communities in a way that provides family-supporting, upwardly mobile jobs as well as critical childcare, education, housing, and healthcare services. By investing in broad-based prosperity and productivity, we can build a more equitable and dynamic economy.

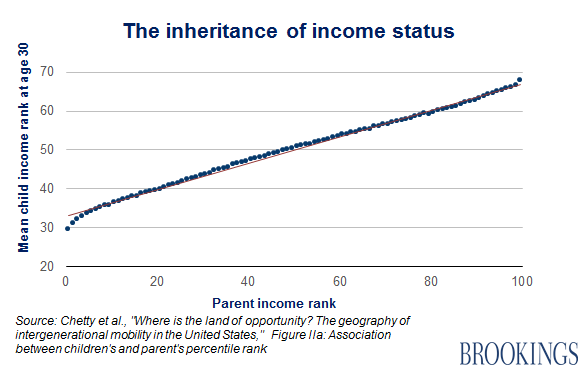

Our agenda is intentionally broad (and correspondingly ambitious) rather than narrow in focus on manufacturing communities, even though current discourse is focused on trade. This is not simply a “political bargain” that provides greater welfare or lip-service concessions to hollowed-out communities in exchange for a return to the prior geoeconomic paradigm. Rather, we genuinely believe that economic dynamism which is led by an empowered middle-class worker, whether they work in manufacturing or in a service industry, is essential to America’s future prosperity and national security – one in which economic outcomes are not determined by parental income and one where black-white disparities are closed in far less than the current pace of 150+ years.

Thus, the ideas and agenda presented here are neither traditionally “liberal” nor “conservative,” “Democrat” nor “Republican.” Instead, we draw upon the intellectual traditions of both segments of the political spectrum. We agree with Ezra Klein’s and Derek Thompson’s vision in Abundance for a technology-enabled future in which America remembers how to build; at the same time, we take seriously Oren Cass’s view in The Once and Future Worker that the dignity of work is paramount and that public policy should empower the middle-class worker. What we offer in the sections below is our vision for a renewed America that crosses traditional policy boundaries to create an economic and political paradigm that works for all.

Policy Recommendations

Investing in American Innovation

Given recent trends, it is clear that there is no better time to re-invigorate America’s innovation edge by investing in R&D to create and capture “industries of the future,” re-shoring capital and expertise, and working closely with allies to expand our capabilities while safeguarding those technologies that are critical to our security. These investments will enable America to grow its economic potential, providing fertile ground for future shared prosperity. We emphasize five key components to renewing America’s technological edge and manufacturing base:

Invest in R&D. Increase federally funded R&D, which has declined from 1.8% of GDP in the 1960s to 0.6% of GDP today. Of the $200 billion federal R&D budget, just $16 billion is allocated to non-healthcare basic science, an area in which the government is better suited to fund than the private sector due to positive spillover effects from public funding. A good start is fully funding the CHIPS and Science Act, which authorized over $200 billion over 10 years for competitiveness-enhancing R&D investments that Congress has yet to appropriate. Funding these efforts will be critical to developing and winning the race for future-defining technologies, such as next-gen battery chemistries, quantum computing, and robotics, among others.

Capability-Building. Develop a coordinated mechanism for supporting translation and early commercialization of cutting-edge technologies. Otherwise, the U.S. will cede scale-up in “industries of the future” to competitors: for example, Exxon developed the lithium-ion battery, but lost commercialization to China due to the erosion of manufacturing skills in America that are belatedly being rebuilt. However, these investments are not intended to be a top-down approach that selects winners and losers: rather, America should set a coordinated list of priorities (leveraging roadmaps such as the DoD’s Critical Technology Areas), foster competition amongst many players, and then provide targeted, lightweight financial support to industry clusters and companies that bubble to the top.

Financial support could take the form of a federally-funded strategic investment fund (SIF) that partners with private sector actors by providing catalytic funding (e.g., first-loss loans). This fund would focus on bridging the financing gap in the “valley of death” as companies transition from prototype to first-of-a-kind / “nth-of-a-kind” commercial product. In contrast to previous attempts at industrial policy, such as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) or CHIPS Act, they should have minimal compliance burdens and focus on rapidly deploying capital to communities and organizations that have proven to possess a durable competitive advantage.

Encourage Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Provide tax incentives and matching funds (potentially from the SIF) for companies who build manufacturing plants in America. This will bring critical expertise that domestic manufacturers can adopt, especially in industries that require deep technical expertise that America would need to redevelop (e.g., shipbuilding). By striking investment deals with foreign partners, America can “learn from the best” and subsequently improve upon them domestically. In some cases, it may be more efficient to “share” production, with certain components being manufactured or assembled abroad, while America ramps up its own capabilities.

For example, in shipbuilding, the U.S. could focus on developing propulsion, sensor, and weapon systems, while allies such as South Korea and Japan, who together build almost as much tonnage as China, convert some shipyards to defense production and send technical experts to accelerate development of American shipyards. In exchange, they would receive select additional access to cutting-edge systems and financially benefit from investing in American shipbuilding facilities and supply chains.

Immigration. America has long been described as a “nation of immigrants.” Their role in innovation is impossible to deny: 46% of companies in the Fortune 500 were founded by immigrants and accounted for 24% of all founders; they are 19% of the overall STEM workforce but account for nearly 60% of doctorates in computer science, mathematics, and engineering. Rather than spurning them, the U.S. should attract more highly educated immigrants by removing barriers to working in STEM roles and offering accelerated paths to citizenship. At the same time, American policymakers should acknowledge the challenges caused by illegal immigration. One such solution is to pass legislation such as the Border Control Act of 2024, which had bipartisan support and increased border security, supplemented by a “points-based” immigration system such as Canada’s which emphasizes educational credentials and in-country work experience.

Create Targeted Fences. Employ tariffs and export controls to defend nascent, strategically important industries such as advanced chips, fusion energy, or quantum communications. However, rather than employing these indiscriminately, tariffs and export controls should be focused on ensuring that only America and its allies have access to cutting-edge technologies that shape the global economic and security landscape. They are not intended to keep foreign competition out wholesale; rather, they should ensure that burgeoning technology developers gain sufficient scale and traction by accelerating through the “learn curve.”

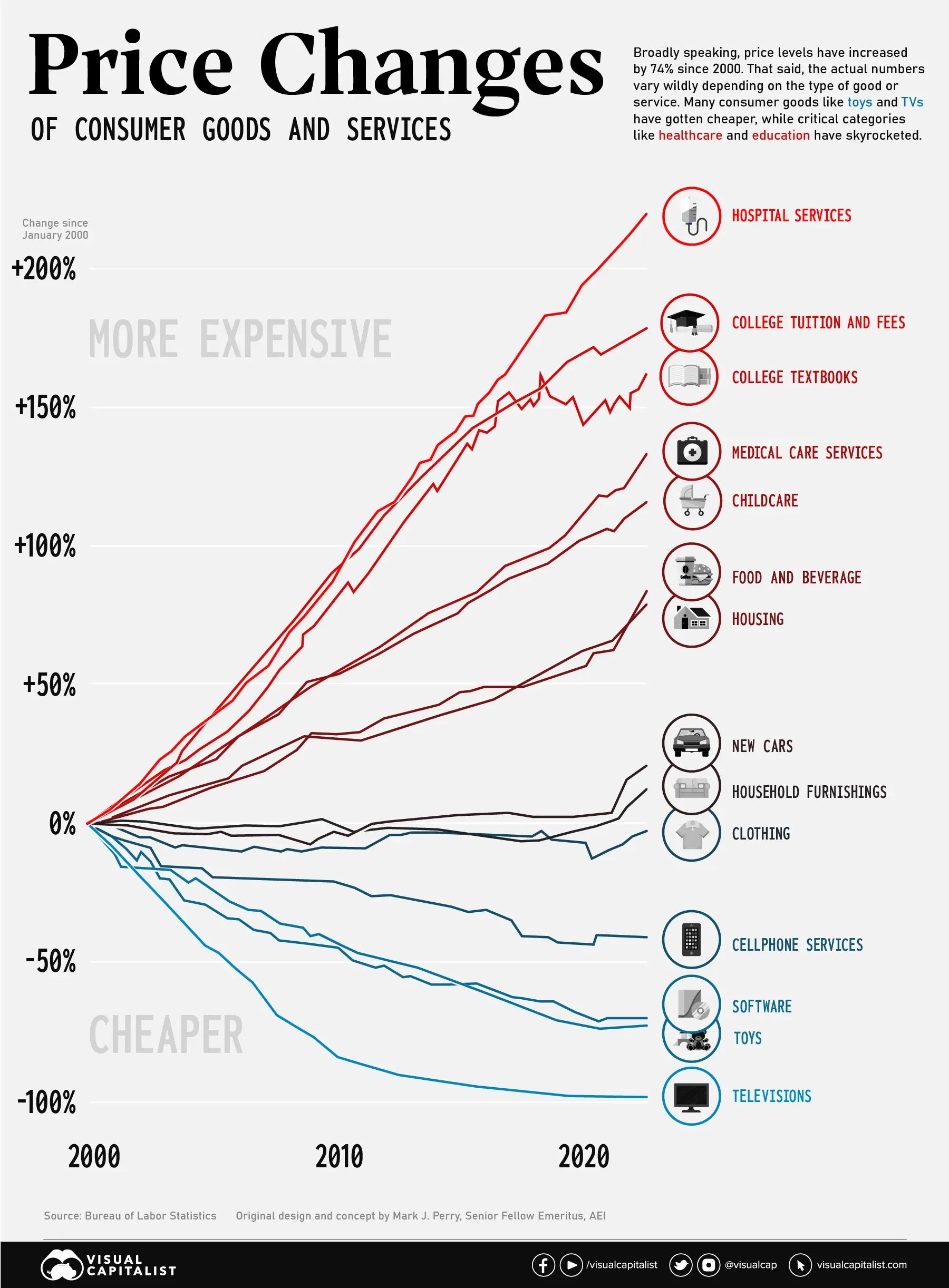

Building Strong Communities

Strong communities are the foundation of a strong workforce, without which new industries will not thrive beyond a small number of established tech hubs. However, strengthening American communities will require the country to address the core needs of a family-sustaining life. Childcare, education, housing, and healthcare are among the largest budget items for families and have been proven time and again to be critical to economic mobility. Nevertheless, they are precisely the areas in which costs have skyrocketed the most, as has been frequently chronicled by the American Enterprise Institute’s “Chart of the Century.” These essential services have been underinvested in for far too long, creating painful shortages for communities that need them most. As such, addressing these issues form the core pillars of our domestic reinvestment plan. Addressing them means grappling with the underlying drivers of their cost and scarcity. These include issues of state capacity, regulatory and licensing barriers, and low productivity growth in service-heavy care sectors. A new policy agenda that addresses the fundamental supply-side issues is needed to reshape the contours of this debate.

Expand Childcare. Inadequate childcare costs the U.S. economy $122 billion in lost wages and productivity as otherwise capable workers, especially women, are forced to reduce hours or leave the labor force. Access is further exacerbated by supply shortages: more than half the population lives in a “childcare desert,” where there are more than three times as many children as licensed slots. Addressing these shortages will alleviate the affordability issue, enabling workers to stay in the workforce and allow families to move up the income ladder.

Fund Early Education. Investments in early childhood education have been demonstrated to generate compelling ROI, with high-quality studies such as the Perry preschool study demonstrating up to $7 – $12 of social return for every $1 invested. While these gains are broadly applicable across the country, they would make an even greater difference in helping to rebuild manufacturing communities by making it easier to grow and sustain families. Given the return on investment and impact on social mobility, American policymakers should consider investing in universal pre-K.

Invest in Workforce Training and Community Colleges. The cost of a four-year college education now exceeds $38K per year, indicating a clear need for cheaper BA degrees but also credible alternatives. At the same time, community colleges can be reimagined and better funded to enable them to focus on high-paying jobs in sectors with critical labor shortages, many of which are in or adjacent to “industries of the future.” Some of these roles, such as IT specialists and skilled tradespeople, are essential to manufacturing. Others, such as nursing and allied healthcare roles, will help build and sustain strong communities.

Build Housing Stock. America has a shortage of 3.2 million homes. Simply put, the country needs to build more houses to address the cost of living and enable Americans to work and raise families. While housing policy is generally decided at lower levels of government, the federal government should provide grants and other incentives to states and municipalities to defray the cost of developing affordable housing; in exchange, state and local jurisdictions should relax zoning regulations to enable more multi-family and high-density single-family housing.

Expand Healthcare Access. American healthcare is plagued with many problems, including uneven access and shortages in primary care. For example, the U.S. has 3.1 primary care physicians (PCPs) per 10,000 people, whereas Germany has 7.1 and France has 9.0. As such, the federal government should focus on expanding the number of healthcare practitioners (especially primary care physicians and nurses), building a physical presence for essential healthcare services in underserved regions, and incentivizing the development of digital care solutions that deliver affordable care.

Allocating Funds to Invest in Tomorrow’s Growth

Investment Requirements

While we view these policies as essential to America’s reinvigoration, they also represent enormous investments that must be paid for at a time when fiscal constraints are likely to tighten. To create a sense of the size of the financial requirements and trade-offs required, we lay out each of the key policy prescriptions above and use bipartisan proposals wherever possible, many of which have been scored by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) or another reputable institution or agency. Where this is not possible, we created estimates based on key policy goals to be accomplished. Although trade deals and targeted tariffs are likely to have some budget impact, we did not evaluate them given multiple countervailing forces and political uncertainties (e.g., currency impacts).

Potential Pay-Fors

Given the budgetary requirements of these proposals, we looked for opportunities to prune the federal budget. The CBO laid out a set of budgetary options that collectively could save several trillion over the next decade. In laying out the potential pay-fors, we used two approaches that focused on streamlining mandatory spending and optimizing tax revenues in an economically efficient manner. Our first approach is to include budgetary options that eliminate unnecessary spending that are distortionary in nature or are unlikely to have a meaningful direct impact on the population that they are trying to serve (e.g., kickback payments to state health plans). Our second approach is to include budgetary options in which the burden would fall upon higher-earning populations (e.g., raising the cap on payroll and Social Security taxes).

As the table below shows, there is a menu of options available to policymakers that raise funding well in excess of the required investment amounts above, allowing them to pick and choose which are most economically efficient and politically viable. In addition, they can modify many of these options to reduce the size or magnitude of the effect of the policy (e.g., adjust the point at which Social Security benefits for “high earners” is tapered or raise capital gains by 1% instead of 2%). While some of these proposals are potentially controversial, there is a clear and pressing need to reexamine America’s foundational policy assumptions without expanding the deficit, which is already more than 6% of GDP.

Conclusion

America is in need of a new economic paradigm that renews and refreshes rather than dismantles its hard-won geopolitical and technological advantages. Trump’s tariffs, should they be fully enacted, would be a self-defeating act that would damage America’s economy while leaving it more vulnerable, not less, to rivals and adversaries. However, we also recognize that the previous free trade paradigm was not truly equitable and did not do enough to support manufacturing communities and their core strengths. We believe that our two-pronged approach of investing in American innovation alongside our allies along with critical community investments in childcare, higher education, housing, and healthcare bridges the gap and provides a framework for re-orienting the economy towards a more prosperous, fair, and secure future.

Restoring U.S. Leadership in Manufacturing

Manufacturing is a critical sector for American economic well-being. The value chains in the American economy that rely on manufactured goods account for 25% of employment, over 40% of gross domestic product (GDP), and almost 80% of research and development (R&D) spending in the United States. Yet U.S. leadership in manufacturing is eroding. U.S. manufacturing employment plummeted by one-third—and 60,000 U.S. factories were closed—between 2000 and 2010 (Bonvillian and Singer, Advanced Manufacturing: The New American Innovation Policies, MIT Press, 2018, 52, 265.) Only some 18% of the production jobs lost in the United States during the Great Recession were recovered in the following decade, and production output only returned to its pre–Great Recession levels in 2018. This hollowing out of U.S. manufacturing has been largely driven by international competition, particularly from China. China passed the United States in 2011 as the largest global manufacturing power in both output and value added. The nations have literally traded places: China now has 31% of world manufacturing output while the U.S. has dropped to 16%. The U.S. has not just lost leadership in low-price commodity goods: As part of its massive trade deficit in 2023 of $733 billion in overall manufactured goods, the U.S. ran a deficit of $218 billion in advanced technology goods.

Declining U.S. manufacturing has sharply curtailed a key path to the middle class for those with high school educations or less, thereby exacerbating income inequality nationwide. As a country, we are increasingly leaving a large part of our working class behind an ever-advancing upper middle class. The problems plaguing the domestic manufacturing sector are multifold: American manufacturing productivity is historically low; the supporting ecosystem for small and midsized manufacturers has thinned out so they are slow to adopt process and technology innovations; manufacturing firms lack access to financing when they seek to scale up production for new innovations; manufacturing is poorly supported by our workforce-education system; and we have disconnected our innovation system from our production systems.

The United States can address many of these problems through concerted efforts in advanced manufacturing. Advanced manufacturing means introducing new production technologies and processes to significantly lower production costs and raise efficiency. This would reposition the United States to better compete internationally. Advanced manufacturing also requires that we reconnect innovation with production. A milestone in advanced manufacturing came in 2012, when the federal government established the first of 17 Advanced Manufacturing Institutes with two more planned. Each institute in this network is organized around developing new advanced technologies, from 3D printing to digital production to biofabrication. Each also represents a collaboration among industry, government, and academic institutions. Three federal agencies invest a total of approximately $200 million per year in the institutes—an amount matched by industry and states.

The manufacturing institutes have proven successful to date. But they cannot reboot American manufacturing alone; other efforts are needed. Key U.S. trading partners and competitors spend far more on maintaining their manufacturing base and investing in advanced manufacturing compared to their GDP than the U.S. does. To restore U.S. leadership in manufacturing and rebuild manufacturing as a route to quality jobs for Americans, the federal government must double down on advanced manufacturing nationwide. Specifically, the next administration should:

- Create a White House Office of Advanced Manufacturing to provide centralized agency leadership and develop a strategic plan positioning the United States as world leader in advanced manufacturing.

- Create a new financing mechanism for scale-up of promising advanced manufacturing production.

- Grow the funding for manufacturing institutes and improve the program.

- Multiply the level of R&D in advanced manufacturing at federal agencies and better connect the manufacturing institutes and manufacturers to the strengths of the federal research system.

- Link new technologies emerging from research agencies and the manufacturing institutes to acquisition programs of the Department of Defense for implementation.

- Create a new workforce-education system designed to prepare workers for jobs in advanced manufacturing.

- Develop an ongoing assessment of advanced production capabilities emerging in other nations.

More detail on these and related recommendations is provided below.

Challenge

Obstacles facing U.S. manufacturing

The United States faces multiple obstacles related to manufacturing:

- Low manufacturing productivity. The rate of U.S. manufacturing productivity growth has been in decline for more than a decade. Since 2009, annual U.S. manufacturing productivity growth has averaged less than a quarter of a percent, far behind Germany, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, South Korea, France, and Italy. Low productivity signals a problem with the innovation system underlying the domestic manufacturing sector.

- Thinned-out manufacturing ecosystem. Investment in capital plant, equipment, and information technology is at historically low levels. The U.S. financial sector has pressured firms to lower financial risk by cutting back on the scope of their production activities, vertical integration and connections to suppliers (known as going “asset light”). This has incentivized offshoring, outsourcing, and a thinning of the shared links between firms in areas like training and best production practices—the manufacturing commons. This was particularly problematic for small and midsized manufacturers who relied on this commons. The U.S. has been slow to implement advanced manufacturing—for example, in robots per manufacturing worker, the U.S. is seventh among industrialized nations, far behind Korea, Germany, and China. A large part of this problem is that small and midsized firms, which have close to half of U.S. manufacturing output, are left behind in manufacturing innovation and are slow to adopt new advanced manufacturing technologies.

- Limited capacity to conduct and scale innovation. Small and midsized manufacturers, which tend to be risk-averse and thinly capitalized, have limited capacity to conduct in-house R&D and innovation. Although larger firms have greater capacity for innovation, becoming increasingly globalized has affected U.S. firms’ innovation capacity. And the entrepreneurial, venture-backed startups that have traditionally injected innovation into the U.S. economy have focused overwhelmingly on software, services, and biotechnology. “Hardtech” firms that plan to manufacture received only a small fraction of U.S. venture-capital investments. In contrast, China provides massive financing for its firms to scale up production in critical technology areas and to adopt advanced manufacturing, totaling approximately $500 billion a year. It has also authorized $1.6 trillion in “guidance funds,” private-sector funds with joint private capital and government funding for scaling up manufacturing production. The U.S. has no comparable production scale-up mechanisms.

- Poor support from the workforce-education system. Although a highly skilled workforce is essential to rapidly introduce new technologies, the United States has reduced spending on workforce training, including in manufacturing. The U.S. government also significantly underinvests in workforce-training programs, dedicating just 0.1% of GDP to active labor-market programs—less than half of what it did three decades ago. (By comparison, other Organization for Economic Development governments dedicate an average of 0.6% of GDP to such programs.) The U.S. labor market also lacks a system to help employers and employees learn about and navigate training programs or make connections between school and work to help new entrant workers handle the transition. Labor Department programs focus on underemployed workers, not upskilling incumbent workers with the new skills required in manufacturing, and Education Department programs focus on college education, not workforce education.

- Delinked innovation and production. There is a tendency to think of innovation exclusively as part of R&D. Yet production is a key stage in the innovation pipeline. Production—especially of a new technology—requires creative engineering and iteration with researchers. Investing in basic R&D but not innovative manufacturing technologies and processes makes us strong on technology ideas but lacking the capacity to move these ideas from prototype to production. Because innovation and production are so closely linked, outsourcing production equates to outsourcing innovation—which in turn makes it easier for international competitors to capitalize on American ingenuity and erode American economic strength.

From 2000 to 2010, U.S. manufacturing employment fell precipitously, from about 17 million to under 12 million. While employment declined in all manufacturing sectors, those most prone to globalization (such as textiles and furniture) were especially affected. This is largely attributable to China’s competitive entry into manufacturing, which experts have estimated caused the loss of 2.4 million U.S. manufacturing jobs.

The U.S. manufacturing decline has adversely affected economic well-being in numerous historically industrialized regions—especially for the men without college degrees who have long led U.S. manufacturing employment. Full-year employment of men with a high school diploma but without a college degree dropped from 76% in 1990 to 68% in 2013, and the share of these men who did not work at all rose from 11% to 18%. While real wages have grown over recent decades for men and women with college degrees, they fell for men without college degrees. These trends have affected the working class overall and are particularly worrying for the socioeconomic mobility of minority populations in the United States. African Americans and Hispanics have long comprised a significant portion of the manufacturing workforce, and manufacturing jobs have long been a critical route to enter the middle class. With manufacturing’s decline, this avenue upward has significantly narrowed. While post-COVID workforce shortages slightly improved the economic position of the working class for the past two years, a deep gulf of economic inequality remains.

Opportunity

Although lagging behind countries such as Germany, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and China in manufacturing innovation, the United States is still a world leader on R&D innovation overall. There is a valuable opportunity to leverage domestic capabilities in R&D innovation to bolster manufacturing capabilities in. A variety of cutting-edge technologies—including new sensor and control systems, big data and analytics, robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), complex simulation and modeling, advanced materials and composites, biofabrication, mass customization (the ability to produce small customized lots at mass-production costs through 3D printing and computerized controls), nanofabrication, and photonics—have potential applications in manufacturing. Using such technologies to create new advanced-manufacturing paradigms could transform manufacturing efficiency, productivity, and returns on investment.

A national advanced manufacturing initiative would yield multiple benefits. Investment in advanced manufacturing could restore U.S. manufacturing leadership and therefore help employment; in addition, certain advanced-manufacturing technologies (e.g., 3D printing) could re-localize supply chains and generate additional jobs. Pursuing innovative manufacturing methods could improve production cost efficiency, enabling the United States to compete successfully with nations where labor costs are lower. Production innovation will also generate better products and create new product markets. Finally, robust domestic manufacturing capabilities are increasingly understood to be essential to national security. Advanced manufacturing constitutes a “leap ahead”: If the U.S. could lead on the mix of these new innovative technologies and related processes, it could again be a manufacturing leader.

Plan of Action

A manufacturing transformation requires the following steps:

- Create White House Office of Advanced Manufacturing to coordinate advanced manufacturing policy across agencies and with industry and develop an ongoing strategic manufacturing plan.

- Implement a new financing mechanism to scale up advanced manufacturing in companies.

- Improve and adequately fund the manufacturing institute program.

- Undertake R&D on manufacturing technologies and processes at federal research agencies and connect it to the institutes.

- Link new manufacturing technologies emerging from the R&D agencies and the manufacturing institutes to acquisition by the Department of Defense for implementation.

- Reform the manufacturing workforce education system.

- Develop an ongoing assessment of innovation and advanced production capabilities in critical technology areas emerging in other nations.

Recommendation 1. Create a new White House Office of Advanced Manufacturing to coordinate across agencies and develop a strategic plan for positioning the United States as a world leader in advanced manufacturing.

The White House Office of Advanced Manufacturing should work with the National Economic Council and the President’s Council of Advisors for Science and Technology (PCAST)—as well as industry, university, and government leaders—to develop a public/private national advanced manufacturing strategic plan. Staffing and support could come from Manufacturing USA (the network organization for the institutes) and the three federal agencies that fund the institutes (DOD, DOE, and DOC), as well as from other involved agencies. The plan should:

- Outline recommended policies to support overall manufacturing-technology development, expand advanced workforce education, address needed trade measures, and secure a sound manufacturing economic climate.

- Coordinate the manufacturing R&D and development efforts across federal agencies, including the three leading departments (DOD, DOE and DOC) as well as R&D agencies. This should include coordination across the manufacturing institutes and the through the Manufacturing USA network.

- Specify funding levels needed to carry out key advanced-manufacturing efforts and address recommendations listed below.

- Provide specific implementation steps for the President and Congress.

The strategy should also establish a mechanism and timeline for periodic updating of the plan.

Recommendation 2. Create a New Financing Mechanism for Scale-Up of Advanced Manufacturing

While venture capital has been a major force financing innovation in the U.S., it is now focused overwhelmingly on software, biotech, and various services sectors, not on “hard tech” – innovations that must be manufactured. This means there are few mechanisms to scale up manufacturing production in the U.S.

Shifting to advanced manufacturing requires scale-up financing to support it. This is particularly a problem for small and midsized manufacturers who are reluctant to take the risk of significant investments in new advanced manufacturing technologies. We have a number of models for scale-up financing: The CHIPS Act, to reestablish U.S. manufacturing of advanced semiconductor chips because of national security concerns, provided grant authority of $39 billion for new fabrication facilities as well as low-cost financing and investment tax credits. Operation Warp Speed in 2020 used guaranteed contracts to COVID-19 vaccine makers to reduce their risks and assure production. Senator Chris Coons and colleagues have proposed an industrial finance corporation for innovative manufacturing. The DOD in 2022 created a new Office of Strategic Capital for technology scale up, although it appears focused more on national security rather than broader economic security goals. The Biden Administration proposed repurposing an established federal bank, the Ex-Im Bank, to provide manufacturing scale-up support along with its long-standing export financing role. The DOE’s Loan Programs Office has since 2005 provided financing for scale-up of new energy technologies. In addition, states have often provided financing to firms to support regional job creation.

There are a range of possible manufacturing scale-up mechanisms. Because it is an existing bank fluent with industry lending and risk, Ex-Im appears a logical contender for significant expansion of its program into manufacturing scale-up financing. It has a broad authorization that would enable it to do so and has embarked on initial lending in this area. This uses the capability of an existing institution and avoids having to create a new one. Applying this and other mechanisms with expanded lending authority for advanced manufacturing scale up could be a solution to this serious manufacturing system gap.

Recommendation 3. Improve the Advanced Manufacturing Institute Program

A key part of the manufacturing transformation involves improving the federally funded advanced manufacturing institute program, also called Manufacturing USA (a.k.a. the institutes). The institutes, which were formed to help close the gap between R&D innovation and production innovation, involved the critical actors required for developing advanced manufacturing technologies: industry, universities, community colleges, and federal, state, and local government.

Established based on recommendations from the industry- and university-led Advanced Manufacturing Partnership (AMP) in 2012, the 17 institutes are designed to create new production paradigms in different production areas, shared across the supply chains of large and small firms and across industry sectors. The institutes are partially funded by federal agencies: nine are funded by the Department of Defense (DOD), seven by the Department of Energy (DOE), and one (plus the two upcoming institutes funded through the CHIPS Act) by the Department of Commerce (DOC). Total federal funding for the institutes is currently approximately $200 million per year. Each federal dollar is typically matched by about two dollars from industry and state governments.

Why institutes? One key reason is that the great majority of the U.S. manufacturing sector firms are small and midsized, producing nearly half of U.S. output, that—as noted above—typically do not perform in-house R&D and have difficulty accessing the production innovation they need to compete. Challenges facing small and midsize manufacturing firms became even greater in the 2000s, when U.S. manufacturing output stagnated and factories closed. Moreover, even larger firms with R&D capabilities need to collaborate to share the major risks and costs of transitioning to new production paradigms. The institutes address these challenges and needs by acting as test beds—providing a range of industries and firms with opportunities to collaborate on, test, and prove prototypes for advanced production technologies and processes. The institutes also help fill manufacturing talent gaps, training technical workers to use advanced technologies and to develop processes and routines for introducing advanced technologies into established production systems. And, as noted, they can bring the critical actors together (industry, academia, government). Any manufacturing technology program to work has to connect these actors.

In short, the manufacturing institutes help fill gaps in the U.S. manufacturing innovation system by:

- Connecting small and large firms in collaborative innovation to restore the thinned-out manufacturing ecosystem.

- Relinking innovation and production through collaborations between firms and universities.

- Pursuing innovations that improve manufacturing efficiency and productivity.

- Providing shared facilities to support scale-up of promising technologies.

- Training a skilled workforce to use advanced manufacturing technologies.

Although technology development is a long-term project, the institutes have already delivered some notable results. Institute-supported achievements to date include:

- The first foundry for tissue engineering

- Standards to guide implementation of 3D-printing technology

- Optimized sensor networks for smart manufacturing

- Advanced fibers that contain individually controllable electronic devices

- A virtual software tool that replicates supplier tools in order to verify that production can meet highly precise standards

- A suite of online courses to educate technicians and engineers in integrated photonics production

These successes notwithstanding, the current institute program cannot solve the systemic problems plaguing U.S. manufacturing. The next administration should dramatically scale up and expand the role of the institutes as part of an effort to usher in a new era of advanced manufacturing nationwide.

The institutes’ collaborative, cost-shared, public/private model is designed to engage all critical stakeholders. But with U.S. manufacturing contributing $2.3 trillion to GDP, federal spending of just $200 million annually to support the institutes (even if those funds are matched by industry and state governments) will not make a large impact. Specific recommendations for the institutes are:

Increase funding for the Manufacturing USA institute program

The institutes are delivering successes, but they are not funded at a level commensurate with their important role. The level of seed funding has significantly declined in the institutes supported by the DOE and DOD. While the DOC’s single institute has kept up its funding level, the others have faced reductions in the federal share after their initial terms of five years. This has limited, in particular, their programs with small and midsized companies and in workforce education. The federal investment per institute needs to return to well above the $50–70 million level initially awarded per institute over their initial five years. Given what our international competitors are investing, an institute program of at least $500 million a year is needed. The new national strategic plan for advanced manufacturing (described above) could guide funding requests.

Action steps

The next president should seek additional funding for additional institutes, with a goal of increasing the total federal support for institutes of $500 million The next president should also ask other federal agencies with significant research budgets and mission stakes in the industrial economy—such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—to consider sponsoring institutes. Funding levels per institute should be determined by a combination of institute performance, national-strategy recommendations, and the particulars of proposed projects.

Instead of term-limiting institutes, the agencies have been establishing a formal process for determining whether an institute’s term should be extended, but they need to provide funding at least comparable to the institute’s initial term

The institutes were initially established with five-year fixed terms. But the job of the institutes is not done in five years—addressing the deep structural issues in U.S. manufacturing innovation will require sustained effort over decades. Continuing federal seed funding is still needed at least at levels of their initial five-year terms to leverage private sector investment. However, the agencies have been going in different directions on subsequent funding. Congress has recognized that the institutes should not face fixed terms. But this does not mean that all institute terms should be automatically renewed. The federal government should extend those that are working well, end those that aren’t, and require improvements in others. Like any experiment, the institutes will engender successes and failures. The institute network needs a governance process that recognizes that.

Two of the three federal agencies that currently fund and oversee the institutes—DOD, and DOC—have been implementing performance metrics aligned with the strategic goals of the institutes. DOD and DOC have developed a formal evaluation process that each institute must go through when it approaches the end of its term and applies for term renewal. DOE is now following their lead, subject to availability of funding. This review process was specifically recommended by a National Academies study. Agencies should consider elements such as an institute’s progress on its technology-development roadmaps, the impact of its current and planned technology development, the reach of its workforce-education efforts, involvement of small and midsized firms, and continued support from and cost-sharing by industry and states. The evaluation process and criteria should be carefully developed such that they can be conducted by an impartial, third-party expert review team. Finally, the evaluation process should be as consistent as possible across the entire institute network.

Where the evaluation concludes that an institute is making adequate progress, the evaluation team should recommend that its funding be renewed for an additional five-year term. If progress is inadequate, the institute could be terminated or recommended for renewal contingent on specific improvements. In cases where an inadequate institute has responsibility for an essential technology area, the evaluation team could also recommend seeking different leadership and organizational changes. All evaluations—even those for institutes deemed to be making adequate progress—could provide recommendations for improvements.

It is not enough to establish a formal review process; if an institute is performing well, it should be extended for an additional term at funding levels at least comparable to the funding level it received for its initial term. The agencies have gone in different directions on this key point. DOC has extended its institute with full funding; DOD and DOE provide only limited funding to the extent that it is available. Given the gravity of U.S. manufacturing problems, this needs to change.

Action steps

When institutes are meeting their mission goals, they should extend their terms at funding levels at least comparable to what these institutes initially received.

Use the institutes to strengthen industry supply chains by bringing all supply-chain participants into demonstration facilities

Most of the institutes have established hands-on and virtual demonstration and design facilities accessible to small and midsized firms participating in the institutes. These facilities are important because smaller firms are less likely to adopt new production technologies unless they can see how those technologies would work within production lines, train employees in using new technologies, and estimate the potential efficiency gains new technologies could yield for them.

But many advanced-manufacturing technologies—such as digital-production technologies—cannot be implemented unless adopted by all participants in a given supply chain. The institutes need to bring in participants of industrial supply chains in addition to individual firms in order to disseminate advanced-manufacturing technologies most successfully.

Action steps

The institutes should develop programs whereby larger manufacturers can bring in other participants in their supply chains as new technologies become ready for adoption. Manufacturing USA should support supply-chain-level demonstration and testing using institute demonstration facilities. NIST’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) programs should be asked to assist in these efforts given their access to small manufacturing firms. In general, the new administration should support expanded collaboration and system-wide thinking at the implementation stage of advanced-manufacturing technologies and ensure that new technologies and processed developed at institutes move deep into the supply chain, not just to larger firms.

Network the manufacturing institutes to package their different technology advances to be integrated and readily useable by manufacturers

Because companies will want to adopt a series of new technologies, collaboration across the institutes will likely be essential to improving workforce education. Cross-institute collaboration will also help private-sector participants build “factories of the future” that integrate multiple advanced-manufacturing technologies. The role of Manufacturing USA needs to be expanded to support collaboration in these areas as well as cost sharing, dissemination of best practices in intellectual property, membership organization, involvement of small and midsized firms, and joint access to facilities and equipment. Yet agency cooperation to sustain the network has been limited at the time when the need for a collaborative network is becoming clearer. Companies, particularly smaller companies, don’t want individual stovepiped technologies. They want robotics and digital production technologies and analytics plus new areas such as 3D printing—and they need to be interoperable. They don’t want one-off technologies. Presenting manufacturers with integrated packages of technologies with demonstrated efficiency increases will be key to adoption. Similarly, companies would like workforce skills packaged and integrated across new technology fields.

Action steps

The next administration should expand the role of Manufacturing USA to help the institutes, participating companies, and the workforce as a whole confront the challenges of implementing advanced manufacturing. In particular integrating multiple advanced-manufacturing technologies from multiple institutes to be offered to manufacturers as a package will be key.

Recommendation 4. Bring the strength of the U.S. early-stage R&D innovation system to bear on advanced manufacturing

Federal R&D agencies do not have significant research portfolios around advanced manufacturing technologies and processes, contributing to a serious innovation gap in U.S. manufacturing. While federal research agencies have made massive contributions to information technologies and life science advances, for example, they have not focused on manufacturing technologies. Given our societal challenge in manufacturing, they need to develop this approach. These new research efforts must be connected to and involve industry to help identify the most significant technology opportunities. Because the institutes work on applied and later-stage research, they rely on “feeder systems” for early-stage research. When the institutes aren’t connected closely enough to early-stage research systems—when they have limited knowledge of what research is being carried out and limited capacity to inform the research agenda—they risk “stranded technology” problems. In other words, they will be limited in their ability to capitalize on new results and/or to keep developing concepts progressing. The incoming administration should strive to better link the federal basic-research system (including DOD’s 6.1–6.3-level research programs, NSF’s engineering and computing research and its new directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships, and DOE research at ARPA-E, OS, and EERE) both to industry and to the institutes and their technology focus areas.

Action steps

The next administration should work through OSTP, with its agency-convening authority, to require federal entities responsible for basic research to develop and implement significant research portfolios around advanced manufacturing. Industry should advise and participate in this research. In addition, OSTP, in cooperation with the proposed White House Advanced Manufacturing Office, should form joint R&D agency and manufacturing institute planning and roadmapping processes to support the institutes’ technology focus areas. Such an effort will assist agencies in developing and highlighting research activities that complement the institutes’ technology-development activities, and vice versa.

Recommendation 5. Link new manufacturing technologies emerging from the R&D agencies and the manufacturing institutes to acquisition by the Department of Defense

DOD has a massive annual procurement program; this program could be used to introduce advanced production technologies and processes that could help DOD lower costs and improve system performance. DOD has done this before. When computer numerically controlled (CNC) equipment was developed at MIT in the 1950s, DOD saw that it could significantly improve the precision and performance in missiles and other technologies. It therefore required its manufacturing suppliers to adopt CNC equipment and helped finance its introduction at these firms. Application at these firms spread CNC equipment to virtually all manufacturers today. We could use this same approach today to get advanced manufacturing technologies in place.

DOD did not select the technology focus areas for its nine manufacturing institutes by accident; these technologies support its industrial base and new systems need them. Thus, the institutes are critical for ensuring that DOD possesses the domestic capacity to produce new innovations at scale. Technologies produced by non-DOD-funded institutes are often relevant to DOD as well. For example, the power electronics coming out of a DOE-funded institute will yield not only improved energy efficiency but improved electronics and power systems in general, which are important to DOD. Another DOE-funded institute is developing advanced composites that could significantly improve DOD operating platforms.

Unlike other agencies, DOD not only has a major acquisition system, but it is connected to its R&D system—it can research, develop, and build new technologies. Most private-sector manufacturing firms, particularly smaller firms, tend to be risk- and cost-averse and are hence often reluctant to lead on production in new areas. DOD can fill this gap by using its acquisition system to support testing, design prototyping, and initial procurement for new technologies coming out of the institutes. This would benefit the nation by jump-starting deployment of emerging innovations and would benefit DOD by providing the agency with early access to technologies not yet available on the private market.

Action steps

The incoming administration should direct DOD to (1) review its relevant demonstration, testing, and acquisition processes so they can be used for implementing advanced manufacturing technologies, (2) identify specific options for the agency to leverage these processes to procure emerging manufacturing technologies it needs, including from the institutes, and (3) identify changes to existing regulations and systems that would help link DOD acquisition with advanced manufacturing innovation emerging from R&D agencies, industry and institutes. ( For example, DOD may be able to reinstitute a form of its industrial/modernization incentive program or apply its Defense Production Act Title III authorities.) The next administration should then take prompt action to implement recommendations arising from the review.

Recommendation 6. Work to create a new workforce education system designed to prepare workers for jobs in advanced manufacturing

Germany has long gained productivity improvements from a famously well-trained manufacturing workforce based on an apprenticeship system. In contrast, U.S. companies have generally tried to get productivity gains from capital plant and equipment investments and ignored the workforce side. German firms understand, however, that productivity gains from new equipment will soon spread worldwide, while a gain from a high-quality workforce will be enduring and provide a long-term competitive edge. Like Germany, the U.S. needs both inputs.

Unfortunately, American workforce-education systems are largely broken. The U.S. has a deep disconnect between the education system and workplaces, which lies at the heart of many of its workforce problems. (See detailed discussion of these issues and corresponding recommendations in Bonvillian and Sarma, Workforce Education.) Other causes include:

- Disinvestment in workforce education by both government and employers in recent decades

- Federal training programs that have limited focus on higher technical skills and incumbent workers

- Federal education programs that have large gaps in filling workforce needs and are not linked or complementary to other federal programs

- A vocational education system in secondary schools that has largely been dismantled.

- Underfunded community colleges that lack the resources to provide advanced training in emerging fields

- Colleges and universities that could help develop higher-end, new technology skills are disconnected from workforce education and other participants in workforce-education systems (particularly from community colleges)

- The limited scale of those creative, advanced technical education programs that do exist

- A broken labor-market information system that doesn’t effectively serve workers, employers, or educators

Complicating efforts to establish new and improved workforce-education systems is the fact existing systems depend heavily on actors in complex, established “legacy” sectors that are hard to change. At the federal level, only a modest NSF program in Advanced Technological Education (ATE), through community colleges, provides education and training in advanced manufacturing. The manufacturing institutes are also developing workforce education efforts at both the technician and engineering levels, but these are also modest in scope. NIST’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership is encouraging new workforce programs for its SME participants. Neither the Department of Labor (DOL) nor the Department of Education (DOEd), however, has a program dedicated to education or training in advanced manufacturing. These existing programs need to be strengthened. The institutes, for example, through their unique blend of academic, public, and private-sector participation, are well positioned to help build a skilled advanced-manufacturing workforce. The institutes also have the deep technical expertise needed to effectively guide the content and structure of new workforce-education manufacturing modules in emerging technologies.

If the U.S. wants to adopt advanced manufacturing, its workforce must be ready for it. This requires rebuilding much of workforce education. Reforms are needed at all levels. Community colleges must introduce advanced manufacturing curricula, create short programs more adapted to upskilling workers already in the workforce, establish certificates around particular skills that stack toward degrees, and turn around low completion rates. At the federal level, disconnected Labor and Education Department programs need to be integrated and efforts to expand registered apprenticeship programs accelerated. At the industry level, firms must collaborate with each other and with community colleges to build new training and apprenticeship programs, including youth apprenticeships starting in high school. Solutions will have to be pursued in the U.S. federal system, since education is largely state and local government-led. These federal agencies need to improve community college funding and support, integrate advanced manufacturing programs across community colleges, promote apprenticeships and work closely with area firms on reforms and curricula.

Action steps

The White House Office of Advanced Manufacturing (OAM) proposed above, working with Manufacturing USA, DOD, DOL, DOEd, NSF ATE, and NIST, should launch a coordinated effort to identify best practices in workforce education at the involved agencies, institutes, and elsewhere, including for online education. OAM and Manufacturing USA should also develop an education “commons” of shared advanced-manufacturing courses, modules, and materials. OAM, the workforce education agencies noted above and Manufacturing USA should ensure that current and future workforce-education efforts are coordinated for a unified cross-agency effort. Working with existing manufacturing skills standards groups, OAM and these agencies will likely also need to establish standards for certifications in advanced manufacturing fields, so that certifications can be earned at one place and recognized at another. Manufacturing USA Institutes can play an important role because of their expertise in their specific technology areas. Expert teams will need to be assembled to develop these training resources and standards, as well as to evaluate their effectiveness. Because workforce education tends to suffer from the “tragedy of the commons”—many want it but few want to pay for it—the incoming administration should support federal funding for all of the above efforts and ensure that relevant participating agencies include these efforts in their budget requests.

Recommendation 7. Develop an ongoing assessment of advanced production capabilities in critical technologies emerging in other nations

In 2023, pursuant to the CHIPS and Science Act, NSF sponsored a study commission to develop a pilot program to assess international innovation and manufacturing capability in critical technology sectors. The U.S. doesn’t undertake such a systematic critical technology assessment, and it has become a major gap in our capabilities and understanding. We are integrated into an international economy that we helped create and now face massive trade deficits in manufactured and advanced technology goods. The U.S. is failing to track our increasingly innovative competitors and their implementation of emerging technologies. In effect, in a highly competitive world the U.S. is flying blind. The report provides a framework for undertaking this kind of assessment. Adoption of a critical technology assessment of competitor nations and the U.S.’s comparative status is important to both national and economic security; we need a benchmarking system on where we stand and the new approaches others are adopting that we need to pursue.

If located in the intelligence or defense agencies, this would help ensure longer-term sustainable support, and these agencies could also collaborate with key non-defense agencies. Since national security is now so closely tied to economic security, this is an appropriate role for intelligence or defense organizations. It is important to have a sustained assessment effort led by a talented staff team that can build expertise in the complex assessment process, which is also connected to draw on university and industry experts.

Action steps

The next administration should direct the Director of National Intelligence or DOD (working with DOC, NSF, and DOE, which also have relevant technical capabilities) to conduct an ongoing assessment of the progress of other leading nations in critical technologies and advanced manufacturing. The assessment should examine the strategic goals, internal organization, and funding levels of international advanced-manufacturing initiatives. Such an assessment should emphasize aspects of advanced manufacturing where the U.S. industrial base, including from a national security perspective, has a significant stake in future technology, such as advanced materials, semiconductors and computing, composites, photonics, functional fibers, power electronics, biofabrication, and a suite of digital tools that are finding applications in manufacturing and other sectors (e.g., AI, machine learning, the Internet of Things, robotics, simulations and modeling, data analytics, and quantum sensors and computing). Such an assessment would help us understand the status of critical elements of its industrial base and inform the focus areas and technology-development agendas of the various institutes and agencies. The assessment would also benefit the United States as a whole by guiding national manufacturing strategy and ensuring that the institutes are used to maximize the country’s global competitiveness in manufacturing.

Implementation

The need to bolster the U.S. manufacturing has become a political imperative for both parties. Many aspects of the recommendations detailed above could be implemented quickly by presidential directives and would not require legislation. Increasing funding for the institutes and advanced manufacturing generally is, of course, the exception. But congressional approval for increased advanced manufacturing funding seems likely. Despite the sharp political divides of the past decade, Congress overwhelmingly passed bipartisan legislation in 2014 authorizing the institutes and amended that legislation in 2019—a strong political signal of political support around this issue. Congress has also been willing to back advanced manufacturing in appropriations bills each year. A bipartisan congressional manufacturing caucus, and deep understanding by a number of key congressional figures of issues related to advanced manufacturing, provide a solid foundation of expected legislative-branch support for executive-branch actions to further advanced manufacturing.

Conclusion

Production plays a disproportionate role in U.S. economic well-being. As international competitors move rapidly on advanced manufacturing while U.S. manufacturing capabilities stagnate, the U.S. economy is increasingly vulnerable. These are national security issues as well as economic security issues, and the two are increasingly merged. Public-private models, (particularly Manufacturing USA and the manufacturing institutes), organized around advanced manufacturing, offer a promising model for helping reverse these trends and restoring U.S. leadership in manufacturing. The institutes bring together the key actors: industry, universities, community colleges, and government (federal, state, and local). But the institutes as they now stand simply do not have the capacity to affect the U.S. manufacturing sector at the scale needed.

The recommendations detailed here provide the next administration with a roadmap for launching a nationwide effort to strengthen advanced manufacturing—an effort that builds on the institutes’ successes and significantly expands their capabilities, roles, and impacts. Briefly summarized, the recommendations are:

- A White House Office of Advanced Manufacturing to coordinate manufacturing policy across agencies and with industry and to develop an ongoing strategic manufacturing plan;

- A new financing mechanism for scaling-up advanced manufacturing in companies;

- Improving and adequately funding the manufacturing institute program by:

- Increasing funding for the Manufacturing USA institute program;

- Providing ongoing funding at least comparable to the institute’s initial term;

- Strengthening industry supply chains by bringing all supply-chain participants into demonstration facilities;

- Networking the manufacturing institutes to package their different technology advances so they are integrated and readily useable by manufacturers;

- Undertaking R&D on manufacturing technologies and processes at federal research agencies and connecting it to the institutes and industry;

- Linking new manufacturing technologies emerging from the R&D agencies and the manufacturing institutes to acquisition by the Department of Defense for implementation;

- Reforming the manufacturing workforce education system; and

- Developing an ongoing assessment of innovation and advanced production capabilities in critical technology areas emerging in other nations so we understand the competition.

Douglas Brinkley’s book American Moonshot tells how, in 1961, President Kennedy mobilized the American public around a new space mission. The mission was rationalized in part on Cold War competition but also on the dramatic mission-related technology advances—from communication satellites to STEM education to computing—that the president argued would (and did) boost the economy. The direct tie between advanced manufacturing and the future of the American economy is, frankly, far more visible to the public than the space race. Strong presidential leadership could unify public support around a shared goal of manufacturing leadership and building quality jobs in a period of political fracture. There is a dramatic competitive aspect: China has already passed the United States on manufacturing output while we as a nation play catch-up, and China’s increased economic power and the corresponding. decline in the U.S. share of world manufacturing output have important implications for the future of democracy and world leadership. Furthering advanced manufacturing in the United States also involves rethinking and rebuilding our workforce-education systems, another potentially highly popular imperative. And, finally, advanced manufacturing includes not only government but industry, universities, community colleges, and nonprofits as well. In short, advanced manufacturing can unite nearly all American institutions—and nearly all Americans.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

BioNETWORK: The Internet of Distributed Biomanufacturing

Summary

The future of United States industrial growth resides in the establishment of biotechnology as a new pillar of industrial domestic manufacturing, thus enabling delivery of robust supply chains and revolutionary products such as materials, pharmaceuticals, food, energy. Traditional centralized manufacturing of the past is brittle, prone to disruption, and unable to deliver new products that leverage unique attributes of biology. Today, there exists the opportunity to develop the science, infrastructure, and workforce to establish the BioNETWORK to advance domestic distributed biomanufacturing, strengthen U.S.-based supply chain intermediaries, provide workforce development for underserved communities, and achieve our own global independence and viability in biomanufacturing. Implementing the BioNETWORK to create an end-to-end distributed biomanufacturing platform will fulfill the Executive Order on Advancing Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Innovation and White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) Bold Goals for U.S. Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing.

Challenge and Opportunity

Biotechnology harnesses the power of biology to create new services and products, and the economic activity derived from biotechnology and biomanufacturing is referred to as the bioeconomy. Today, biomanufacturing and most other traditional non-biomanufacturing is centralized. Traditional manufacturing is brittle, does not enhance national economic impact or best use national raw materials/resources, and does not maximize innovation enabled by the unique workforce distributed across the United States. Moreover, in this era of supply chain disruptions due to international competition, climate change, and pandemic-sized threats (both known and unknown), centralized approaches that constitute a single point of attack/failure and necessarily restricted, localized economic impact are themselves a huge risk. While federal government support for biotechnology has increased with recent executive orders and policy papers, the overarching concepts are broad, do not provide actionable steps for the private sector to respond to, and do not provide the proper organization and goals that would drive outcomes of real manufacturing, resulting in processes or products that directly impact consumers. A new program must be developed with clear milestones and deliverables to address the main challenges of biomanufacturing. Centralized biomanufacturing is less secure and does not deliver on the full potential of biotechnology because it is:

- Reliant on a narrow set of feedstocks and reagents that are not local, introducing supply chain vulnerabilities that can halt bioproduction in its earliest steps of manufacturing.

- Inflexible for determining the most effective, stable, scalable, and safe methods of biomanufacturing needed for multiple products in large facilities.

- Serial in scheduling, which introduces large delays in production and limits capacity and product diversity.

- Bespoke and not easily replicated when it comes to selection and design of microbial strains, cell free systems, and sequences of known function outside of the facility that made them. Scale-up and reproducibility of biomanufacturing products are limited.

- Creating waste streams because circular economies are not leveraged.

- Vulnerable to personnel shortages due to shifting economic, health, or other circumstances related to undertraining of a biotechnology specialized workforce.

Single point failures in centralized manufacturing are a root cause of product disruptions and are highlighted by current events. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed that point failures in the workforce or raw materials created disruptions in the centralized manufacturing, and availability of hand sanitizers, rubber gloves, masks, basic medicines, and active pharmaceutical ingredients impacted every American. International conflict with China and other adversarial countries has also created vulnerabilities in the sole source access to rare earth metals used in electronics, batteries, and displays, driving the need for alternate options for manufacturing that do not rely on single points of supply. To offset this situation, the United States has access to workforce, raw materials, and waste streams geographically distributed across the country that can be harnessed by biomanufacturing to produce both health and industrial products needed by U.S. consumers. However, currently there are only limited distributed manufacturing infrastructure development efforts to locally process those raw materials, leaving societal, economic, and unrealized national security risks on the table. Nation-scale parallel production in multiple facilities is needed to robustly create products to meet consumer demand in health, industrial, energy, and food markets.

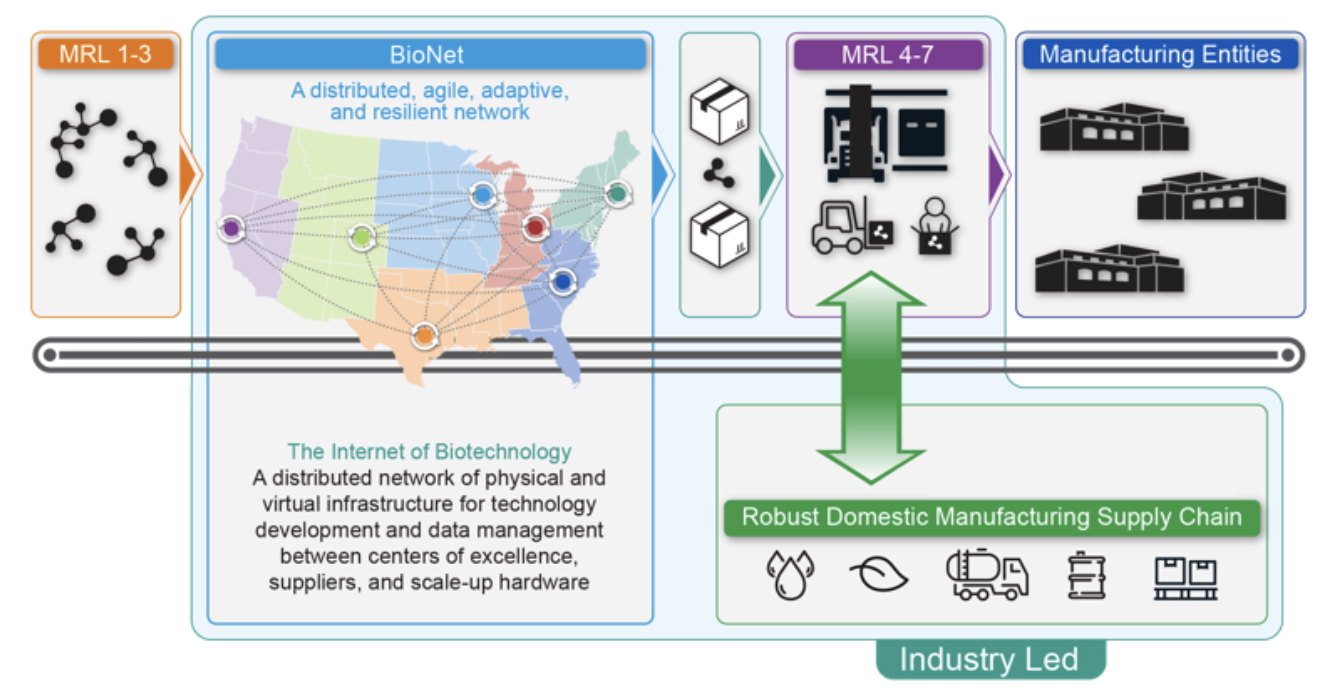

The BioNETWORK inverts the problem of a traditional centralized biomanufacturing facility and expertise paradigm by delivering a decentralized, resilient network enabling members to rapidly access manufacturing facilities, expertise, and data repositories, as needed and wherever they reside within the system, by integrating the substantial existing U.S. bioindustrial capabilities and resources to maximize nationwide outcomes. The BioNETWORK should be constructed as an aggregate of industrial, academic, financial, and nonprofit entities, organized in six regionally-aligned nodes (see figure below for notional regional distribution) of biomanufacturing infrastructure that together form a hub network that cultivates collaboration, rapid technology advances, and workforce development in underserved communities. The BioNETWORK’s fundamental design and construction aligns with the need for new regional technology development initiatives that expand the geographical distribution of innovative activity in the U.S., as stated in the CHIPS and Science Act. The BioNETWORK acts as the physical and information layer of manufacturing innovation, generating market forces, and leveraging ubiquitous data capture and feedback loops to accelerate innovation and scale-up necessary for full-scale production of novel biomaterials, polymers, small molecules, or microbes themselves. As a secure network, BioNETWORK serves as the physical and virtual backbone of the constituent biomanufacturing entities and their customers, providing unified, distributed manufacturing facilities, digital infrastructure to securely and efficiently exchange information/datasets, and enabling automated process development. Together the nodes function in an integrated way to adaptively solve biotechnology infrastructure challenges as well as load balancing supply chain constraints in real-time depending on the need. This includes automated infrastructure provisioning of small, medium, or large biomanufacturing facilities, supply of regional raw materials, customization of process flow across the network, allocation of labor, and optimization of the economic effectiveness. The BioNETWORK also supports the implementation of a national, multi-tenant cloud lab and enables a systematic assessment of supply chain capabilities/vulnerabilities for biomanufacturing.

As a secure network, BioNETWORK serves as the physical and virtual backbone of the constituent biomanufacturing entities and their customers, providing unified, distributed manufacturing facilities, digital infrastructure to securely and efficiently exchange information/datasets, and enabling automated process development.

Plan of Action

Congress should appropriate funding for an interagency coordination office co-chaired by the OSTP and the Department of Commerce (DOC) and provide $500 million to the DOC, Department of Energy (DOE), and Department of Defense (DOD) to initiate the BioNETWORK and use its structure to fulfill economic goals and create industrial growth opportunities within its three themes:

- Provide alternative supply chain pathways via biotechnologies and biomanufacturing to promote economic security. Leverage BioNETWORK R&D opportunities to develop innovative biomanufacturing pathways that could address supply chain bottlenecks for critical drugs, chemicals, and other materials.