ALI Releases Statement on the President’s FY2024

WASHINGTON, D.C. — The Alliance for Learning Innovation (ALI) applauds the increases proposed for education research and development (R&D) and innovation in the President’s budget request. These include the $870.9 million proposed for the Institute of Education Sciences (IES), including $75 million for a National Center for Advanced Development in Education (NCADE), the $405 million proposed for the Education Innovation and Research (EIR) program and the $1.4 billion for the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Directorate for STEM Education. These investments represent real commitments to advancing an inclusive education research system that centers students, teachers, and communities.

These recommendations build upon the bipartisan interest in utilizing education R&D to accelerate learning recovery, increase student achievement, and ensure students and teachers are prepared for the continued impact technology will have on teaching and learning. National and economic security depends on the success of our students and ALI appreciates the priorities this budget request places on fostering innovations in education that will support U.S. competitiveness.

Dan Correa, CEO of the Federation of American Scientists and co-lead of ALI notes, “Investments in education research and development hold so much promise for dramatically improving gaps in student achievement. Learning recovery, workforce development, and global competition all demand a pool of talent that can only come from an education system that meets the needs of diverse learners. The President’s budget request recognizes that more robust education R&D is needed to support bold innovations that meet the needs of students, teachers, families, and communities.”

This budget will allow IES and other federal agencies the ability to build on boundary-pushing efforts like the National AI Institute for Exceptional Education, which is supporting advancements in AI, human-AI interaction, and learning science to improve educational outcomes for children with speech and language related challenges.

For too long, federal support for education R&D has languished while resources and attention have been devoted to R&D in health care, defense, energy, and other fields. Today’s budget represents a critical step forward in addressing this deficiency. The Alliance for Learning Innovation looks forward to championing the continued development of an education R&D ecosystem that will lead to the types of groundbreaking developments and advancements we see in health care and defense; thus affording students everywhere access to fulfilling futures.

For more information about the Alliance for Learning Innovation, please visit https://www.alicoalition.org/.

A Bipartisan Health Agenda to Unite America: Innovative Ideas to Strengthen American Wellbeing

As the COVID-19 pandemic has clearly shown – American health is crucial to the health of our nation. Yet American health is under threat from all angles, from escalating chronic deadly diseases like cancer to rising mental health challenges and the growing overdose epidemic. All of these threats contribute to the United States ranking 31st in life expectancy at birth, one of the lowest in the developed world, despite having the highest health spending per capita.

At the State of the Union, the Biden Administration presented a bipartisan platform dedicated to securing the health and wellbeing of the American people, from our Veterans to our youth. An agenda is a first step – unified action on public health comes next. Evidence-based science policy can bring us closer to a healthier future. Since 2020, policy entrepreneurs have developed innovative implementation-ready policy proposals through the Day One Project (D1P) to tackle some of the biggest societal problems. Here are a few that speak to the current moment:

To combat cancer…

With the median monthly cost of cancer drugs topping $10,000, many families cannot afford the costs of caring for their loved ones. Yet, there are 1,100 FDA-approved off-patent generics that could be used for treating cancer, at a fraction of the cost. Congress should appropriate $100 million into Phase III clinical trials of off-patent generics for treating a variety of cancers. This funding can go towards the National Cancer Institute and be implemented through an open-source pharmaceutical R&D framework through accelerated progress towards accessible and affordable cures.

Environmental hazards are a growing driver of cancers, and disproportionately impact rural and disadvantaged communities. Air pollution has been linked to lung cancer, the most deadly cancer for both men and women in the US. An interagency collaboration led by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and leveraging funds from the Inflation Reduction Act could deploy a network on low-cost, real-time, ground-based sensors in all 300 US cities with a population above 100,000 to track particulate matter rates. Connecting this data to relevant providers in these cities, such as federally-qualified community health centers, could inform physicians of high-risk sites to target early screening interventions. Further, materials composing American homes, from housing materials to pipe materials, and even water running in the faucets, have been identified as possible sources of carcinogens. The Biden Administration should launch the President’s Task Force on Healthy Housing and Water for Cancer Prevention to coordinate research, develop the statistical database, and prepare for regulatory actions.

Finally, innovations in primary care can also catch cancer at earlier stages in disease progression. Yet, many rural and disadvantaged communities lack access to primary care. The NIH’s $23 million investment investigating telehealth for cancer care will develop the best care strategies – but labor-market, technical, financial/regulatory barriers, and data barriers will remain for scaling to the broad population. The Biden Administration and Congress will need to collaborate to unlock barriers to delivering healthcare services directly to the American home, through reforming licensure, expanding broadband access, investing in new mobile healthcare devices, expanding Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements, and ensuring data interoperability.

To strengthen mental health…

Digital mental health technologies have enormous potential to combat the growing mental health crisis, as evidenced by the Administration’s plan on mental health research and development. Yet more work remains to build a national infrastructure for successful implementation of digital mental health services. The vast majority of digital mental health technologies are unregulated, as existing FDA standards fail to cover these emerging technologies because many do not make treatment claims. Congress should authorize Health and Human Services (HHS) to develop standards for digital mental health products to ensure clinical effectiveness, data safety, and mitigate risk. Technologies that meet these standards should then be reimbursable through Medicare and Medicaid, which will require further congressional action. Finally, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) should create a National Center for Digital Mental Health to maintain a database of approved digital products, provide training to providers, and ensure compliance of developers with national standards.

Knowing that tech platforms can be harmful to the youth’s wellbeing, the Congress and the Administration can take several steps to protect children’s privacy. Congress can expand the technological expertise at the Department of Education (ED) to protect children’s privacy and security in schools as well as appropriate $160 million funding to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to expand Children’s Online Protection Privacy Act (COPPA) enforcement and further investigate technology companies extracting children’s data. The Administration can commission a task force to identify ways to protect children’s data through existing legislation such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and COPPA.

To tackle the opioid crisis…

The opioid crisis is claiming thousands of lives every year, and there is bipartisan consensus on action. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) has sought strategies to prevent opioid use disorders – which will require reforms to the insurance reimbursement model which less generously covers preventative services. The Biden Administration should pilot a multidisciplinary study group to implement payment for prevention, using opioid use disorders as the test case. Following the guidance of the study group, CMS should provide guidelines to contracts between states and managed care organizations (MCOs) and between MCOs and providers and provide necessary technical assistance to implement these guidelines.

To deliver on care for Veterans…

Five million veterans live in rural areas, and of those, 45% lack access to reliable broadband internet, reducing access to vital health services. To ensure Veterans remain connected to healthcare services wherever they are, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) should partner with the Postal Service and/or Department of Agriculture to pilot telehealth hubs in rural communities using existing FY23 appropriations for telehealth. An initial focus of care delivery could be on digital mental health and suicide prevention. Going forward, care delivery innovations like this one, if successful, can inspire new policies for the broader population, if the VHA’s health policy mission is expanded. VHA should be added to strategic interagency health policy coalitions such as the ACA interagency working group on healthcare quality and Healthy People 2030 to share data, develop innovative projects, and evaluate progress.

There’s more work to be done to build a healthier future for all Americans – these ideas can be jumping off points for Executive and Congressional action. FAS will continue to develop and surface evidence-based policies that can make a difference, and submissions to the Day One project are always welcome.

Tilling the Federal SOIL for Transformative R&D: The Solution Oriented Innovation Liaison

Summary

The federal government is increasingly embracing Advanced Research Projects Agencies (ARPAs) and other transformative research and engagement enterprises (TREEs) to connect innovators and create the breakthroughs needed to solve complex problems. Our innovation ecosystem needs more of these TREEs, especially for societal challenges that have not historically benefited from solution-oriented research and development. And because the challenges we face are so interwoven, we want them to work and grow together in a solution-oriented mode.

The National Science Foundation (NSF)’s new Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships should establish a new Office of the Solution-Oriented Innovation Liaison (SOIL) to help TREEs share knowledge about complementary initiatives, establish a community of practice among breakthrough innovators, and seed a culture for exploring new models of research and development within the federal government. The SOIL would have two primary goals: (1) provide data, information, and knowledge-sharing services across existing TREEs; and (2) explore opportunities to pilot R&D models of the future and embed breakthrough innovation models in underleveraged agencies.

Challenge and Opportunity

Climate change. Food security. Social justice. There is no shortage of complex challenges before us—all intersecting, all demanding civil action, and all waiting for us to share knowledge. Such challenges remain intractable because they are broader than the particular mental models that any one individual or organization holds. To develop solutions, we need science that is more connected to social needs and to other ways of knowing. Our problem is not a deficit of scientific capital. It is a deficit of connection.

Connectivity is what defines a growing number of approaches to the public administration of science and technology, alternatively labeled as transformative innovation, mission-oriented innovation, or solutions R&D. Connectivity is what makes DARPA, IARPA, and ARPA-E work, and it is why new ARPAs are being created for health and proposed for infrastructure, labor, and education. Connectivity is also a common element among an explosion of emerging R&D models, including Focused Research Organizations (FROs) and Distributed Autonomous Organizations (DAOs). And connectivity is the purpose of NSF’s new Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP), which includes “fostering innovation ecosystems” in its mission. New transformative research and engagement enterprises (TREEs) could be especially valuable in research domains at the margins, where “the benefits of innovation do not simply trickle down.

The history of ARPAs and other TREEs shows that solutions R&D is successfully conducted by entities that combine both research and engagement. If grown carefully, such organisms bear fruit. So why just plant one here or there when we could grow an entire forest? The metaphor is apt. To grow an innovation ecosystem, we must intentionally sow the seeds of TREEs, nurture their growth, and cultivate symbiotic relationships—all while giving each the space to thrive.

Plan of Action

NSF’s TIP directorate should create a new Office of Solution-Oriented Innovation (SOIL) to foster a thriving community of TREEs. SOIL would have two primary goals: (1) nurture more TREEs of more varieties in more mission spaces; and (2) facilitate more symbiosis among TREEs of increasing number and variety.

Goal 1: More TREEs of more varieties in more mission spaces

SOIL would shepherd the creation of TREEs wherever they are needed, whether in a federal department, a state or local agency, or in the private, nonprofit, or academic sectors. Key to this is codifying the lessons of successful TREEs and translating them to new contexts. Not all such knowledge is codifiable; much is tacit. As such, SOIL would draw upon a cadre of research-management specialists who have a deep familiarity with different organizational forms (e.g., ARPAs, FROs, DAOs) and could work with the leaders of departments, businesses, universities, consortia, etc. to determine which form best suits the need of the entity in question and provide technical assistance in establishment.

An essential part of this work would be helping institutions create mission-appropriate governance models and cultures. Administering TREEs is neither easy nor typical. Indeed, the very fact that they are managed differently from normal R&D programs makes them special. Former DARPA Director Arati Prabhakar has emphasized the importance of such tailored structures to the success of TREEs. To this end, SOIL would also create a Community of Cultivators comprising former TREE leaders, principal investigators (PIs), and staff. Members of this community would provide those seeking to establish new TREEs with guidance during the scoping, launch, and management phases.

SOIL would also provide opportunities for staff at different TREEs to connect with each other and with collective resources. It could, for example, host dedicated liaison officers at agencies (as DARPA has with its service lines) to coordinate access to SOIL resources and other TREEs and support the documentation of lessons learned for broader use. SOIL could also organize periodic TREE conventions for affiliates to discuss strategic directions and possibly set cross-cutting goals. Similar to the SBIR office at the Small Business Administration, SOIL would also report annually to Congress on the state of the TREE system, as well as make policy recommendations.

Goal 2: More symbiosis among TREEs of increasing number and variety

Success for SOIL would be a community of TREEs that is more than the sum of its parts. It is already clear how the defense and intelligence missions of DARPA and IARPA intersect. There are also energy programs at DARPA that might benefit from deeper engagement with programs at ARPA-E. In the future, transportation-infrastructure programs at ARPA-E could work alongside similar programs at an ARPA for infrastructure. Fostering stronger connections between entities with overlapping missions would minimize redundant efforts and yield shared platform technologies that enable sector-specific advances.

Indeed, symbiotic relationships could spawn untold possibilities. What if researchers across different TREEs could build knowledge together? Exchange findings, data, algorithms, and ideas? Co-create shared models of complex phenomena and put competing models to the test against evidence? Collaborate across projects, and with stakeholders, to develop and apply digital technologies as well as practices to govern their use? A common digital infrastructure and virtual research commons would enable faster, more reliable production (and reproduction) of research across domains. This is the logic underlying the Center for Open Science and the National Secure Data Service.

To this end, SOIL should build a digital Mycelial Network (MyNet), a common virtual space that would harness the cognitive diversity across TREEs for more robust knowledge and tools. MyNet would offer a set of digital services and resources that could be accessed by TREE managers, staff, and PIs. Its most basic function could be to depict the ecosystem of challenges and solutions, search for partners, and deconflict programs. Once partnerships are made, higher-level functions would include secure data sharing, co-creation of solutions, and semantic interconnection. MyNet could replace the current multitude of ad hoc, sector-specific systems for sharing research resources, giving more researchers access to more knowledge about complex systems and fewer obstacles from paywalls. And the larger the network, the bigger the network effects. If the MyNet infrastructure proves successful for TREEs, it could ultimately be expanded more broadly to all research institutions—just as ARPAnet expanded into the public internet.

For users, MyNet would have three layers:

- A data layer for archive and access

- An information layer for analysis and synthesis

- A knowledge layer for creating meaning in terms of problems and solutions

These functions would collectively require:

- Physical structures: The facilities, equipment, and workforce for data storage, routing, and cloud computing

- Virtual structures: The applications and digital environments for sharing data, algorithms, text, and other media, as well as for remote collaboration in virtual laboratories and discourse across professional networks

- Institutional structures: The practices and conventions to promote a robust research enterprise, prohibit dangerous behavior, and enforce community data and information standards.

How might MyNet be applied? Consider three hypothetical programs, all focused on microplastics: a medical program that maps how microplastics are metabolized and impact health; a food-security program that maps how microplastics flow through food webs and supply chains; and a social justice program that maps which communities produce and consume microplastics. In the data layer, researchers at the three programs could combine data on health records, supply logistics, food inspections, municipal records, and demographics. In the information layer, they might collaborate on coding and evaluating quantitative models. Finally, in the knowledge layer, they could work together to validate claims regarding who is impacted, how much, and by what means.

Initial Steps

First, Congress should authorize and appropriate the NSF TIP Directorate with $500 million over four years for a new Office of the Solution-Oriented Innovation Liaison. Congress should view SOIL as an opportunity to create a shared service among emergent, transformative federal R&D efforts that will empower—rather than bureaucratically stifle—the science and technological advances we need most. This mission fits squarely under the NSF TIP Directorate’s mandate to “mobilize the collective power of the nation” by serving as “a crosscutting platform that collaboratively integrates with NSF’s existing directorates and fosters partnerships—with government, industry, nonprofits, civil society and communities of practice—to leverage, energize and rapidly bring to society use-inspired research and innovation.”

Once appropriated and authorized to begin intentionally growing a network of TREEs, NSF’s TIP Directorate should focus on a four-year plan for SOIL. TIP should begin by choosing an appropriate leader for SOIL, such as a former director or directorate manager of an ARPA (or other TREE). SOIL would be tasked with first engaging the management of existing ARPAs in the federal government, such as those at the Departments of Defense and Energy, to form an advisory board. The advisory board would in turn guide the creation of experience-informed operating procedures for SOIL to use to establish and aid new TREEs. These might include discussions geared toward arriving at best practices and mechanisms to operate rapid solutions-focused R&D programs for the following functions:

- Hiring services for temporary employees and program managers, pipelines to technical expertise, and consensus on out-of-government pay scales

- Rapid contracting toolkits to acquire key technology inputs from foreign and domestic suppliers

- Research funding structures than enable program managers to make use of multiple kinds of research dollars in the same project, in a coordinated fashion, managed by one entity, and without needing to engage different parts of different agencies

- Early procurement for demonstration, such that mature technologies and systems can transition smoothly into operational use in the home agency or other application space

- The right vehicles (e.g., FFRDCs) for SOIL to subcontract with to pursue support structures on each of these functions

- The ability to define multiyear programs, portfolios, and governance structures, and execute them at their own pace, off-cycle from the budget of their home agencies

Beyond these structural aspects, the board must also incorporate important cultural aspects of TREES into best practices. In my own research into the managerial heuristics that guide TREEs, I found that managers must be encouraged to “drive change” (critique the status quo, dream big, take action), “be better” (embrace difference, attract excellence, stand out from the crowd), “herd nerds” (focus the creative talent of scientists and engineers), “gather support” (forge relationships with research conductors and potential adversaries), “try and err” (take diverse approaches, expect to fail, learn from failure), and “make it matter” (direct activities to realize outcomes for society, not for science).

The board would also recommend a governance structure and implementation strategy for MyNet. In its first year, SOIL could also start to grow the Community of Cultivators, potentially starting with members of the advisory board. The board chair, in partnership with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, would also convene an initial series of interagency working groups (IWGs) focused on establishing a community of practice around TREEs, including but not limited to representatives from the following R&D agencies, offices, and programs:

- DARPA

- ARPA-E

- IARPA

- NASA

- National Institutes of Health

- National Institute for Standards and Technology

In years two and three, SOIL would focus on growing three to five new TREEs at organizations that have not had solutions-oriented innovation programs before but need them.

- If a potential TREE opportunity is found at another agency, SOIL should collaborate with the agency’s R&D teams to identify how the TREEs might be pursued and consult the advisory board on the new mission space and its potential similarities and differences to existing TREEs. If there is a clear analogue to an existing TREE, the SOIL should use programmatic dollars to detail one or two technical experts for a one-year appointment to the new agency’s R&D teams to explore how to build the new TREE.

- If a potential TREE opportunity is found at a government-adjacent or external organization such as a new Focused Research Organization created around a priority NSF domain, SOIL should leverage programmatic dollars to provide needed seed funding for the organization to pursue near-term milestones. SOIL should then recommend to the TIP Directorate leadership the outcomes of these near-term pilot supports and whether the newly created organization should receive funds to scale. SOIL may also consider convening a round of aligned philanthropic and private funders interested in funding new TREEs.

- If the opportunity concerns an existing TREE, there should be a memorandum of understanding (MOU) and or request for funding process by which the TREE may apply for off-cycle funding with approval from the host agency.

SOIL would also start to build a pilot version of MyNet as a resource for these new TREEs, with a goal of including existing ARPAs and other TREEs as quickly as possible. In establishing MyNet, SOIL should focus on implementing the most appropriate system of data governance by first understanding the nature of the collaborative activities intended. Digital research collaborations can apply and mix a range of different governance patterns, with different amounts of availability and freedoms with respect to digital resources. MyNet should be flexible enough to meet a range of needs for openness and security. To this end, SOIL should coordinate with the recently created National Secure Data Service and apply lessons forward in creating an accessible, secure, and ethical information-sharing environment.

Year four and beyond would be characterized by scaling up. Building on the lessons learned in the prior two years of pilot programs, SOIL would coordinate with new and legacy TREEs to refresh operating procedures and governance structures. It would then work with an even broader set of organizations to increase the number of TREEs beyond the three to five pilots and continue to build out MyNet as well as the Community of Cultivators. Periodic evaluations of SOIL’s programmatic success would shape its evolution after this point. These should be framed in terms of its capacity to create and support programs that yield meaningful technological and socioeconomic outcomes, not just produce traditional research metrics. As such, in its creation of new TREEs, SOIL should apply a major lesson of the National Academies’ evaluation of ARPA-E: explicitly align the (necessarily) robust performance management systems at the project level with strategy and evaluation systems at the program, portfolio, and agency levels. The long-term viability of SOIL and TREEs will depend on their ability to demonstrate value to the public.

The transformative research model typically works like this:

- Engage with stakeholders to understand their needs and set audacious goals for addressing them.

- Establish lean projects run by teams of diverse experts assembled just long enough to succeed or fail in one approach.

- Continuously evaluate projects, build on what works, kill what doesn’t, and repeat as necessary.

In a nutshell, transformative research enterprises exist solely to solve a particular problem, rather than to grow a program or amass a stock of scientific capital.

To get more specific, Bonvillian and Van Atta (2011) identify the unique factors that contribute to the innovative nature of ARPAs. On the personnel front, ARPA program managers are talented managers, experienced in business, and appointed for limited terms. They are “translators,” as opposed to subject-matter experts, who actively engage with allies, rivals, and others. They have great power to choose projects, hire, fire, and contract. On the structure front, projects are driven by specific challenges or visions—co-developed with stakeholders—designed around plausible implementation pathways. Projects are executed extramurally, and managed as portfolios, with clear metrics to asses risk and reward. Success for ARPAs means developing products and services that achieve broad uptake and cost-efficacy, so finding first adopters and creating markets is part of the work.

Some examples come from other Day One proposals. SOIL could work with the Department of Labor to establish a Labor ARPA. It could work with the Department of Education on an Education ARPA. We could imagine a Justice Department ARPA with a program for criminal justice reform, one at Housing and Urban Development aimed at solving homelessness, or one at the State Department for innovations in diplomacy. And there are myriad opportunities beyond the federal government.

TREEs thrive on their independence and flexibility, so SOIL’s functions must be designed to impose minimal interference. Other than ensuring that the TREEs it supports are effectively administered as transformative, mission-oriented organizations, SOIL would be very hands-off. SOIL would help establish TREEs and set them up so they do not operate as typical R&D units. SOIL would give TREE projects and staff the means to connect cross-organizationally with other projects and staff in areas of mutual interest (e.g., via MyNet, the Community of Cultivators, and periodic convenings). And, like the SBIR office at the Small Business Administration, SOIL would report annually to Congress on its operations and progress toward goals.

An excellent model for SOIL is the Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR) system. SBIR is funded by redirecting a small percentage of the budgets of agencies that spend $100 million or more on extramural R&D. Given that SOIL is intended to be relevant to all federal mission spaces, we recommend that SOIL be funded by a small fraction (between 0.1 and 1.0%) of the budgets of all agencies with $1 billion or more in total discretionary spending. This would yield about $15 billion to support SOIL in growing and connecting new TREEs in a vastly widened set of mission spaces.

The risk is the opportunity cost of this budget reallocation to each funding agency. It is worth noting, though, that changes of 0.1–1.0% are less than the amount that the average agency sees as annual perturbations in its budget. Moreover, redirecting these funds may well be worth the opportunity cost, especially as an investment in solving the compounding problems that federal agencies face. By redirecting this small fraction of funds, we can keep agency operations 99–99.9% as effective while simultaneously creating a robust, interconnected, solutions-oriented R&D system.

Advanced Research Priorities in Transportation

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has identified several domains in the transportation and infrastructure space that retain a plethora of unsolved opportunities ripe for breakthrough innovation.

Transportation is not traditionally viewed as a research- and development-led field, with less than 0.7% of the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) annual budget dedicated to R&D activities. The majority of DOT’s R&D funds are disbursed by modal operating administrators mandated to execute on distinct funding priorities rather than a collective, integrated vision of transforming the nation’s infrastructure across 50 states and localities.

Historically, a small percentage of these R&D funds have supported and developed promising, cross-cutting initiatives, such as the Federal Highway Administration’s Exploratory Advanced Research programs deploying artificial intelligence to better understand driver behavior and applying novel data integration techniques to enhance freight logistics. Yet, the scope of these programs has not been designed to scale discoveries into broad deployment, limiting the impact of innovation and technology in transforming transportation and infrastructure in the United States.

As a result, transportation and infrastructure retain a plethora of unaddressed opportunities – from reducing the 40,000 annual vehicle-related fatalities, to improving freight logistics through ports, highways, and rail, to achieving a net zero carbon transportation system, to building infrastructure resilient to the impacts of climate change and severe weather. The reasons for these persistent challenges are numerous: low levels of federal R&D spending, fragmentation across state and local government, risk-averse procurement practices, sluggish commercial markets, and more. When innovations do emerge in this field, they suffer from two valleys of death: one to bring new ideas out of the lab into commercialization, and the second to bring successful deployments of those technologies to scale.

The United States needs a concerted national innovation pipeline designed to fill this gap, exploring early-stage, moonshot research while nurturing breakthroughs from concept to deployment. An Advanced Research Projects Agency-Infrastructure would deliver on this mission. Modeled after the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E), the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Infrastructure (ARPA-I) will operate nimbly and with rigorous program management and deep technical expertise to tackle the biggest infrastructure challenges and overcome entrenched market failures. Solutions would cut across traditional transportation modes (e.g. highways, rail, aviation, maritime, pipelines etc) and would include innovative new infrastructure technologies, materials, systems, capabilities, or processes.

The list of domain areas below reflects priorities for DOT as well as areas where there is significant opportunity for breakthrough innovation:

Key Domain Areas

Metropolitan Safety

Despite progress made since 1975, dramatic reductions in roadway fatalities remain a core, persistent challenge. In 2021, an estimated 42,915 people were killed in motor vehicle crashes, with an estimated 31,785 people killed in the first nine months of 2022. The magnitude of this challenge is articulated in DOT’s most recent National Roadway Safety Strategy, a document that begins with a statement from Secretary Buttigieg: “The status quo is unacceptable, and it is preventable… Zero is the only acceptable number of deaths and serious injuries on our roadways.”

Example topical areas include but are not limited to: urban roadway safety; advanced vehicle driver assistance systems; driver alcohol detection systems; vehicle design; street design; speeding and speed limits; and V2X (vehicle-to-everything) communications and networking technology.

Key Questions for Consideration:

- What steps can be taken to create safer urban mobility spaces for everyone, and what role can technology play in helping create the future we envision?

- What capabilities, systems, and datasets are we missing right now that would unlock more targeted safety interventions?

Rural Safety

Rural communities possess their own unique safety challenges stemming from road design and signage, speed limits, and other factors; and data from the Federal Highway Administration shows that “while only 19% of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, 43% of all roadway fatalities occur on rural roads, and the fatality rate on rural roads is almost 2 times higher than on urban roads.”

Example topical areas include but are not limited to: improved information collection and management systems; design and evaluation tools for two-lane highways and other geometric design decisions; augmented visibility; mitigating or anti-rollover crash solutions; and enhanced emergency response.

Key Questions for Consideration:

- How can rural-based safety solutions address the resource and implementation issues that are faced by local transportation agencies?

- How can existing innovations be leveraged to support the advancement of road safety in rural settings?

Resilient & Climate Prepared Infrastructure

Modern roads, bridges, and transportation are designed to withstand storms that, at the time of their construction, had a probability of occurring once in 100 years; today, climate change has made extreme weather events commonplace. In 2020 alone, the U.S. suffered 22 high-impact weather disasters that each cost over $1 billion in damages. When Hurricane Sandy hit New York City and New Jersey subways with a 14-foot storm surge, millions were left without their primary mode of transportation for a week. Meanwhile, rising sea levels are likely to impact both marine and air transportation, as 13 of the 47 largest U.S. airports have at least one runway within 12 feet of the current sea level. Additionally, the persistent presence of wildfires–which are burning an average of 7 million acres annually across the United States, more than double the average in the 1990s–dramatically reshapes the transportation network in acute ways and causes downstream damage through landslides, flooding, and other natural events.

These trends are likely to continue as climate change exacerbates the intensity and scope of these events. The Department of Transportation is well-positioned to introduce systems-level improvements to the resilience of our nation’s infrastructure.

Example topical areas include but are not limited to: High-performance long-life, advanced materials that increase resiliency and reduce maintenance and reconstruction needs, especially materials for roads, rail, and ports; nature-based protective strategies such as constructed marshes; novel designs for multi-modal hubs or other logistics/supply chain redundancy; efficient and dynamic mechanisms to optimize the relocation of transportation assets; intensive maintenance, preservation, prediction, and degradation analysis methods; and intelligent disaster-resilient infrastructure countermeasures.

Key Questions for Consideration:

- How can we ensure that innovations in this domain yield processes and technologies that are flexible and adaptive enough to ward against future uncertainties related to climate-related disasters?

- How can we factor in the different climate resilience needs of both urban and rural communities?

Digital Infrastructure

Advancing the systems, tools, and capabilities for digital infrastructure to reflect and manage the built environment has the power to enable improved asset maintenance and operations across all levels of government, at scale. Advancements in this field would make using our infrastructure more seamless for transit, freight, pedestrians, and more. Increased data collection from or about vehicle movements, for example, enables user-friendly and demand-responsive traffic management, dynamic curb management for personal vehicles, transit and delivery transportation modes, congestion pricing, safety mapping and targeted interventions, and rail and port logistics. When data is accessible by local departments of transportation and municipalities, it can be harnessed to improve transportation operations and public safety through crash detection as well as to develop Smart Cities and Communities that utilize user-focused mobility services; connected and automated vehicles; electrification across transportation modes, and intelligent, sensor-based infrastructure to measure and manage age-old problems like potholes, air pollution, traffic, parking, and safety.

Example topical areas include but are not limited to: traffic management; curb management; congestion pricing; accessibility; mapping for safety; rail management; port logistics; and transportation system/electric grid coordination.

Key Questions for Consideration:

- How might we leverage data and data systems to radically improve mobility and our transportation system across all modes?

Expediting and Upgrading Construction Methods

Infrastructure projects are fraught with expensive delays and overrun budgets. In the United States, fewer than 1 in 3 contractors report finishing projects on time and within budgets, with 70% citing coordination at the site of construction as the primary reason. In the words of one industry executive, “all [of the nation’s] major projects have cost and schedule issues … the truth is these are very high-risk and difficult projects. Conditions change. It is impossible to estimate it accurately.” But can process improvements and other innovations make construction cheaper, better, faster, and easier?

Example topical areas include but are not limited to: augmented forecasting and modeling techniques; prefabricated or advanced robotic fabrication, modular, and adaptable structures and systems such as bridge sub- and superstructures; real-time quality control and assurance technologies for accelerated construction, materials innovation; new pavement technologies; bioretention; tunneling; underground infrastructure mapping; novel methods for bridge engineering, building information modeling (BIM), coastal, wind, and offshore engineering; stormwater systems; and computational methods in structural engineering, structural sensing, control, and asset management.

Key Questions for Consideration:

- What innovations are more critical to the accelerated construction requirements of the future?

Logistics

Our national economic strength and quality of life depend on the safe and efficient movement of goods throughout our nation’s borders and beyond. Logistic systems—the interconnected webs of businesses, workers, infrastructure processes, and practices that underlie the sorting, transportation, and distribution of goods must operate with efficiency and resilience. . When logistics systems are disrupted by events such as public health crises, extreme weather, workforce challenges, or cyberattacks, goods are delayed, costs increase, and Americans’ daily lives are affected. The Biden Administration issued Executive Order 14017 calling for a review of the transportation and logistics industrial base. DOT released the Freight and Logistics Supply Chain Assessment in February 2022, spotlighting a range of actions that DOT envisions to support a resilient 21st-century freight and logistics supply chain for America.

Topical areas include but are not limited to: freight infrastructure, including ports, roads, airports, and railroads; data and research; rules and regulations; coordination across public and private sectors; and supply chain electrification and intersections with resilient infrastructure.

Key Questions for Consideration:

- How might we design and develop freight infrastructure to maximize efficiency and use of emerging technologies?

- What existing innovations and technologies could be introduced and scaled up at ports to increase the processing of goods and dramatically lower the transaction costs of US freight?

- How can we design systems that optimize for both efficiency and resilience?

- How can we reduce the negative externalities associated with our logistics systems, including congestion, air pollution, noise, GHG emissions, and infrastructure degradation?

ARPA-I: Get Involved

FAS is seeking to engage experts from across the transportation infrastructure community who are the right kind of big thinkers to get involved in developing solutions to transportation moonshots.

Widespread engagement of this diverse network is critical to ensuring ARPA-I’s success. So whether you are an academic researcher, startup CEO, safe streets activist, or have experience with federal R&D programs–we are looking for your insights and expertise.

To be considered for opportunities to support future efforts around transportation infrastructure moonshots, please fill out this form and a member of our team will be in touch as opportunities to get involved arise.

ARPA-I: Share an Idea

Do you have ideas that could inform an ambitious Advanced Research Projects Agency-Infrastructure (ARPA-I) portfolio at the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT)? We’re looking for your boldest infrastructure moonshots.

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is seeking to engage experts across the transportation policy space who can leverage their expertise to help FAS identify a set of grand solutions around transportation infrastructure challenges and advanced research priorities for DOT to consider. Priority topic areas include but are not limited to metropolitan safety, rural safety, resilient and climate-prepared infrastructure, digital infrastructure, expediting “mega projects,” and logistics. You can read more about these topic areas in depth here.

What We’re Looking For and How to Submit

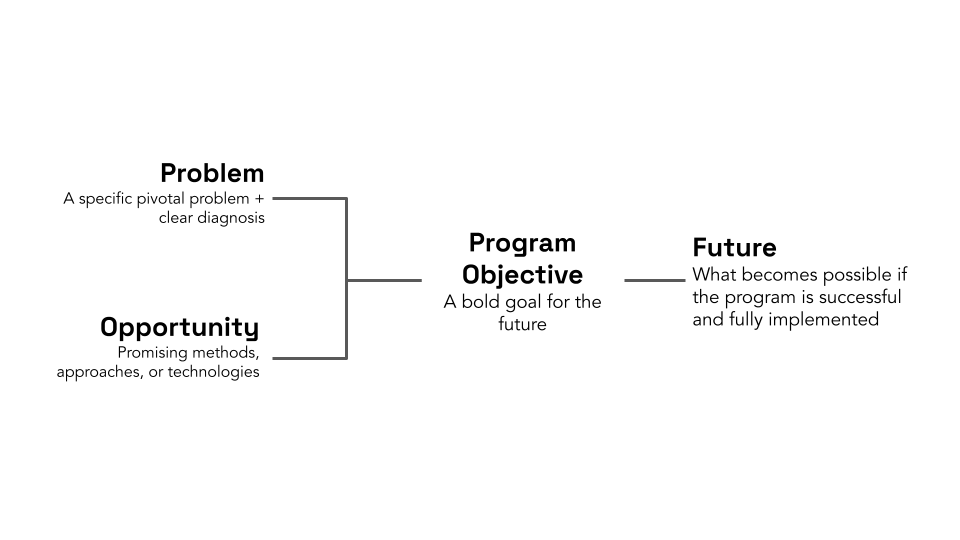

We are looking for experts to develop and submit an initial program design in the form of a wireframe that could inform a future advanced research portfolio at DOT. A wireframe is an outline of a potential program that captures key components that need to be considered in order to assess the program’s fit and potential impact. The template below reflects the components of a program wireframe. Wireframes can be submitted by email here. Please include all four sections of the wireframe shown in the template below in the body of your email submission.

When writing your wireframe, we ask you aim to avoid the following common challenges to ensure that ideas are properly scoped, appropriately ambitious, and are in line with the agency’s goals:

- No clear diagnosis of the problem: Many challenges facing our transportation infrastructure are not defined by a single problem; rather, they are an ecosystem of issues that simultaneously need addressing. An effective program will not only isolate a single “problem” to tackle, but it will approach it at a level where something can actually be done to solve it through root cause analysis.

- Thinking small and narrow: On the other hand, problems being considered for advanced research programs can be isolated down to the point that solving them will not drive transformational change. In this situation, narrow problems would not cater to a series of progressive and complimentary projects that would fit an ARPA.

- Incorrect framing of opportunities: When doing early-stage program design, opportunities are sometimes framed as “an opportunity to tackle a problem.” Rather, an opportunity should reflect a promising method, technology, or approach that is already in existence but would benefit from funding and resources through an advanced research agency program.

- Approaching solutions solely from a regulatory or policy angle: While regulations and policy changes are a necessary and important component of tackling challenges in transportation infrastructure, approaching issues through this lens is not the mandate of an ARPA. ARPAs focus on supporting breakthrough innovations across methods, technologies, and approaches. Additionally, regulatory approaches to problem solving can often be subject to lengthy policy processes.

- No explicit ARPA role: An ARPA should pursue opportunities to solve problems where, without its intervention, breakthroughs may not happen within a reasonable timeframe. If solving a problem already has significant interest from the private or public sector, and they are well on their way to developing a transformational solution in a few years time, then ARPA funding and support might provide a higher value-add elsewhere.

- Lack of throughline: The problems identified for ARPA program consideration should be present as themes throughout the opportunities chosen to solve them as well as how programs are ultimately structured–otherwise, a program may lack a targeted approach to solving a particular challenge.

- Forgetting about end-users: Human-centered design should be at the heart of how ARPA programs are scoped, especially when thinking about the scale at which designers need to think about how solving a problem will provide transformational change for everyday users of transportation infrastructure.

- Being solutions-oriented: Research programs should not be built with pre-determined solutions already in mind; they should be oriented around a specific problem in order to ensure that any solutions put forward are targeted and effective.

For a more detailed primer on ARPA program ideation, please read our publication, “Applying ARPA-I: A Proven Model for Transportation.”

Sample Idea

Informed by input from non-federal subject matter experts

Problem

Urban and suburban environments are complex, with competing uses for public space across modes and functions – drivers, transit users, cyclists, pedestrians, diners, etc. Humans are prone to erratic, unpredictable, and distracted driving behavior, and when coupled with speed, vehicle size, and infrastructure design, such behaviors can cause injury, death, property damage, and transportation system disruption. A decade-old study from NHTSA – at a time when roadway fatalities were approximately 25% lower than current levels – found that the total value of societal harm from crashes in 2010 was $836 billion.

Opportunity

What if the relationships between the driver, the environment (including pedestrians), and the vehicle could be personalized?

- Driver-to-Vehicle: Using novel data gathered from cars’ sensors, driver smartphones, and other collectible data, design a feedback loop that customizes Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) to unique driving behavior signatures.

- Vehicle-to-Environment: Using V2I/V2X and geofencing technologies to govern and harmonize speed and lane operations that optimize max speeds for safety in unique street contexts.

- Driver-to-Environment: Blending both D2V and V2E technologies, develop integrated awareness of the surrounding environment that alerts drivers of potential risks in parked (e.g., car door opening to a bike lane) and moving states (e.g., approaching car).

Program Objective

- Driver-to-Vehicle: (1) Identify the totality of usable driver data within the vehicular environment, from car sensors to phone usage; (2) develop a series of driver profiles that will build the foundation for human-centered, personalized ADAS that can both intervene in an emergency and nudge behavior change through informational updates, intuitive behavioral feedback, or modifying vehicle operations (e.g., acceleration); (3) develop dynamic, intelligent ADAS systems that customize to driver signatures based on preset profiles and experiential, local training of the algorithm; (4) establish this as a proof of concept for a novel, personalized ADAS and architect a grand-challenge for industry to improve upon this personalized, human-centered ADAS with key target metrics; (5) create a regulatory framework mandating Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) to include a baseline level of ADAS, given the results of the grand challenge.

- Vehicle-to-Environment: (1) Design the universal mobile application or geofence trigger that will contour virtual boundaries for a set of diverse, transferrable streets (e.g., school zones) and characteristics (e.g., bike lanes); (2) engage OEMs to design and integrate the geofence triggers with the human-centered ADAS and/or another vehicle-based receiver within a test fleet of different car types to modify vehicle responses to the geofence criteria as outlined by the pilot cities; (3) broker partnerships with 10 cities to identify a menu of geofence criteria, pilot the use of them, and establish a mechanism to measure before-and-after outcomes and comparisons from neighboring regions;

- Driver-to-Environment: integrate ADAS with the geofence trigger to develop an advanced and dynamic situational awareness environment for drivers that is customized to their profile and based on built environment conditions such as bike lanes and school zones, as well as weather, high traffic, and time of day.

Future

Digital transportation networks can communicate personalized information with drivers through their cars in a uniform medium and with a goal of augmenting safety in each of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas.

USDOT Workshop: Transportation, Mobility, and the Future of Infrastructure

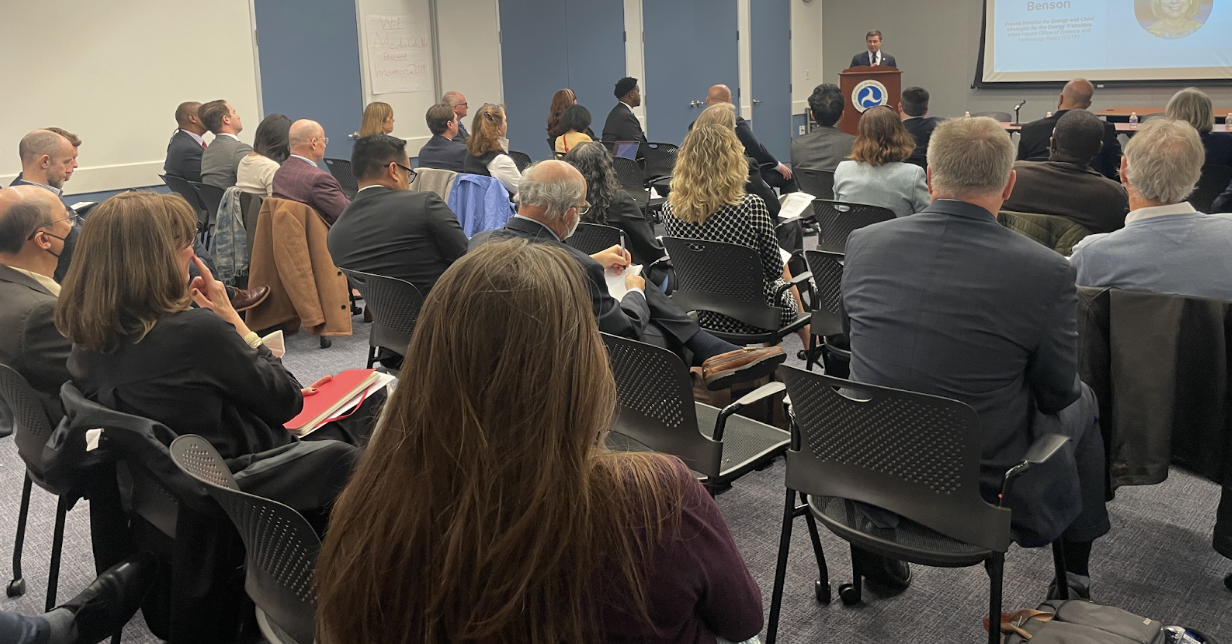

On December 8th, 2022, the U.S. Department of Transportation hosted a workshop, “Transportation, Mobility, and the Future of Infrastructure,” in collaboration with the Federation of American Scientists.

The goal for this event was to bring together innovative thinkers from various sectors of infrastructure and transportation to scope ideas where research, technology, and innovation could drive meaningful change for the Department of Transportation’s strategic priorities.

To provide framing for the day, participants heard from Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg and Deputy Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology Robert Hampshire, who both underscored the potential for a new agency – The Advanced Research Projects Agency – Infrastructure (ARPA-I) to accelerate transformative solutions for the transportation sector. Then, a panel featuring Kei Koizumi, Jennifer Gerbi, and Erwin Gianchandani focused on Federal Research and Development (R&D) explored federal advanced research models that drive innovation in complex sectors and explored how such approaches may accelerate solutions to key priorities in the transportation system.

Workshop participants listening to remarks from U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg.

Participants then participated in separate breakout sessions organized around: 1) safety; 2) digitalization; and 3) climate and resilience. During the breakouts sessions, participants were asked to build on pre-work they had completed before the Workshop by brainstorming future vision statements and using them as the foundation to come up with innovative federal R&D program designs. Participants then regrouped and ended the day by discussing the most promising ideas from their respective breakout sessions, and where their ideas could go next.

The Workshop inspired participants to dig deep to surface meaningful challenges and innovative solutions for USDOT to tackle, whether through ARPA-I or other federal R&D mechanisms, and represents an initial step of a broader process to identify topics and domains in which stakeholders can drive transformational progress for our infrastructure and transportation system. Such an effort will require continued engagement and buy-in from a diverse community of experts.

As such, FAS is seeking to engage experts from across the transportation infrastructure community who are willing to “think big” and creatively about solutions to transportation moonshots. If you’re interested in supporting future efforts around transportation infrastructure moonshots, please visit our “Get Involved” page; if you’re ready to submit an initial program design in the form of a wireframe that could inform a future advanced research portfolio at DOT, please visit our “Share an Idea” page.

Building Momentum for Equity in Medical Devices

Just over a year ago, I found myself pausing during a research lab meeting. “Why were all the subjects in our studies of wearable devices white? And what were the consequences of exclusion?”

This question stuck with me long after the meeting. Digging into the evidence, I was alarmed to find paper after paper signaling embedded biases in key medical technologies.

One device stuck out amongst the rest – the pulse oximeter. Because of its crucial role in diagnosing COVID-19, it had caught the attention of a diverse group of stakeholders: clinicians looking to understand the impacts on patient care, engineers working to build more equitable devices, social scientists tracing the history of device and examining colorism in pulse oximetry, policymakers seeking solutions for their constituents, and the FDA, which was examining racial bias in medical technologies for the first time. But what I found as I scoped out this policy area is that these stakeholders weren’t talking to one another, at the expense of coordinated progress towards equity in pulse oximetry.

With all eyes directed towards the FDA’s Advisory Committee meeting on November 1st, 2022, FAS convened a half-day session of stakeholders on November 2nd to chart a research and policy agenda for near-term mitigation of inequities in pulse oximetry and other medical technologies. Eight experts from medicine, engineering, sociology, and anthropology shared insights with an audience of 60 participants from academia, the private sector, and federal government. Collectively, we developed several key insights for future progress on this issue and outlined a path forward for achieving equity now. You can access the full readout here. We’ll dive into the key highlights below:

Key Insights

Through discussions with experts during the forum, three key themes rose to the surface:

- Racial bias in pulse oximetry cannot be fixed by focusing on “race” alone. Existing evidence suggests reducing bias in pulse oximetry requires replacing devices with less-biased ones. This will take time as new devices are developed and will be a significant cost.

- Better calibration for skin tone is vital, but measurement is complicated. The crux of the problem is a comprehensive standard for quantifying the full range of skin pigmentation. This is vital to understanding how pulse oximeter accuracy varies by melanin content.

- Proactively identifying and addressing bias in medical devices will require system-wide efforts. Identification of bias in medical devices has been piecemeal rather than the outcome of proactive, deliberative efforts. Further efforts to address bias in medical devices should engage diverse stakeholders to establish best practices for ensuring equity in medical devices.

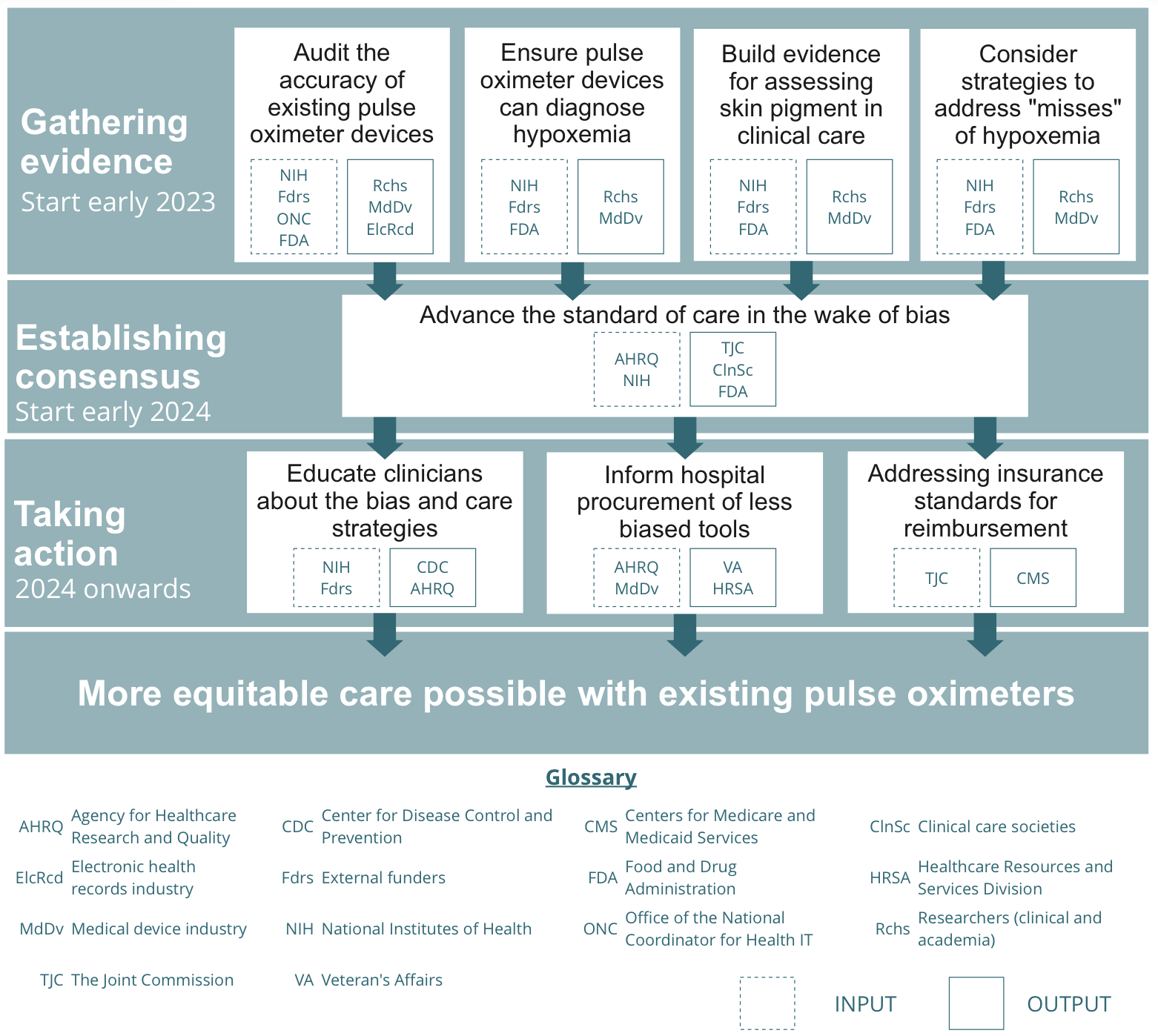

Resolving the problem of bias in pulse oximeter devices will likely take several years. But in the meantime, this issue will continue negatively impacting patients. Our participants urged that we need to think about actions that can be initiated this next year that will advance more equitable care with existing pulse oximeters.

Motivating Action for Equity Now

While a daunting problem, a collaborative, multi-stakeholder effort can bring us closer to solutions. We can work together to advance equity in standards of care by:

- Gathering evidence on existing pulse oximeter devices and their use in care [ASAP, start early 2023]. More evidence is required to identify the best approaches to equitable care with existing devices. This evidence gathering process should be initiated over the next year to inform clinicians on

- Establishing consensus to advance the standard of care [start early 2024]. After growing the body of evidence, there will be a need to convene around key conclusions derived from the evidence. Evidence synthesis will need to be generated and care societies will need to make decisions on how clinicians should use pulse oximeters in their care practice.

- Taking action to ensure equitable care nationwide [2024 onwards]. Once the care standards are changed, there is a need for system-wide efforts to communicate these to clinicians nationwide, inform procurement across federal hospitals, and re-evaluate insurance reimbursement standards.

Looking Ahead

This won’t be easy, but it’s 30 years overdue. We believe correcting the bias will pioneer a model that can be readily applied to combatting biases across the medical device ecosystem, something already underway in the United Kingdom with their Equity in Medical Devices Independent Review. Through a systematic approach, stakeholders can work to close racial disparities in the near-term and advance health equity.

An Overdue Fix for Pulse Oximeters

The invention of pulse oximeters in the 1980s reshaped healthcare. While tracking blood oxygen content (commonly recognized as the “fifth vital sign”) once required a painful blood draw and time-delayed analysis, pulse oximeters deliver nearly instantaneous data by simply sending a pulse of light through the skin. Today, pulse oximeters today are ubiquitous: built into smartwatches, purchased at pharmacies for home health monitoring, and used by clinicians to inform treatment of everything from asthma to heart failure to COVID-19. Emerging algorithms are even incorporating pulse ox data to predict future illness.

There is a huge caveat. Pulse oximeters are medically transformative, but racially biased. The devices work less accurately on dark-skinned populations because melanin, the chemical which gives skin pigment, interferes with light-based pulse ox measurements. This means that dark-skinned individuals can exhibit normal pulse ox readings, but be suffering from hypoxemia or other critical conditions.

But because regulations to this day do not require diversity in medical device evaluation, many pulse ox manufacturers don’t test their devices on diverse populations. And because the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has created streamlined pathways to approve new medical devices based on technology that is “substantially similar” to already-approved technology, the racial bias embedded in ‘80s-era pulse ox technology continues to pervade pulse oximeters on the market today.

COVID-19 illustrated, in devastating fashion, the consequences of this problem. Embedded bias in pulse oximeters demonstrably worsened outcomes for patient populations already disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. Studies show, for instance, that Black COVID-19 patients have been 29% less likely to receive supplemental oxygen on time and three times as likely to suffer occult hypoxemia during the pandemic.

Similar inequities persist across the health-innovation ecosystem. Women suffer from lack of sex-aware prescription drug dosages. Minorities increasingly suffer from biased health risk-assessment algorithms. Children and those with varying body types suffer from medical equipment not built for their physical characteristics. Across the board, inequities create greater risks of morbidity and mortality and contribute to ballooning national healthcare costs.

This need not be the status quo. If health stakeholders—including patient advocates, medtech companies, clinicians, researchers, and policymakers—collectively commit to systematic evaluation and remediation of bias in health technology, change is possible.

An excellent example is eGFR algorithms. These algorithms, used to assess kidney functionality, previously used faulty “correction factors” to account for patient race. But this correction did not actually correlate with biological realities—and instead of treating patients more effectively, it increased disparities in care. Motivated by the data, advocacy and industry organizations issued broad recommendations to avoid using the eGFR calculation. Hospitals and medical systems listened, dropping eGFR from practice, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is now committing funding to investigate alternative calculations.

We as a society must continue to root out bias in health technology, from development to testing to deployment.

When we develop new medical tools, we should consider all the populations who could ultimately need them.

When we test tools, we should rigorously evaluate outcomes across subgroup populations, looking for groups that might fare better or worse from its use in care.

And when we deploy technologies, we need to be ready to track the outcomes of their use at scale.

Engineers, researchers, and clinicians can support these goals by designing medical devices with equity in mind. The UK just launched its evidence-gathering process on equity in medical devices, looking into the impacts of bias and ways to build more equitable solutions. The FDA’s meeting reviewing the evidence on pulse oximetry is a start to auditing technologies for their performance on different populations.

Advocacy organizations can support these goals by providing input to ongoing policy processes. The Federation of American Scientists (FAS), alongside the University of Maryland Medical System, submitted a public comment to the FDA to call for regulations that will encourage the development of low-bias and bias-free tools. FAS is also convening a Forum on Bias in Pulse Oximetry to examine the consequences of bias, build an evidence base for bias-free pulse oximetry, and look ahead to approaches to build more equitable devices.

“Do no harm”, a central oath in medicine, is becoming exceedingly difficult in our technological age. Yet, with an evidence-based approach that ensures technologies equitably serve all groups in a population and works to correct them when they do not, we can come closer to achieving this age-old goal.

What we learned in Mexico City

Moonshots seem impossible—until they’ve hit their target. This was the mantra of our in-person accelerator workshop, hosted with our partners at Unlock Aid in Mexico City. The workshop was just one part of our larger accelerator process where we’re working with innovators to develop moonshots around global development targets. FAS’s largest policy-development convening to date brought together over 70 participants (representing 40+ organizations, 25+ countries, and six continents) to think through creative approaches for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

After years of Zoom calls, phone conferences, and emails, meeting our accelerator cohort in person was a refreshing change of pace. Connecting IRL enabled free-flowing collaboration on big issues like global water security, access, and safety. We saw convergence across organizations: City Taps, Drinkwell, and Evidence Action came together to create the “WaterShot”—a new approach to solving water access with an outcomes marketplace framework. We were reminded anew that policy is powered by people—and that strong interpersonal connections inevitably lead to better and more creative policy ideas.

Brainstorming at the event was inspired by remarks from global development leaders. Project Drawdown spoke about the Drawdown Framework for climate solutions, NPX Advisors demonstrated how to drive better outcomes with advanced market commitments, and Nasra Ismail, a leader in global development strategy, talked about the power of coalition building.

The workshop was an initial opportunity to expose global development experts to the idea that policy, like seed funding or infrastructure investment, is an input that supports scaling. Most individual innovators are understandably hyper-focused on scaling up their individual ideas or products. But good policy is needed to build a flourishing global development environment—a rising tide that lifts all entrepreneurial ships. An underlying theme of the Mexico City workshop was the importance of policy as a growth enabler.

Now that we’re back in DC and over our jetlag, the accelerator continues, and we’re working with workshop participants to inform policymakers on key priorities for global development policy. We’re thinking about pain points in the field and opportunities for systems change, including earmarking funds for innovation, uplifting and incorporating community voices to policy, and setting new standards that focus on results.

The field of global development can be individualized and competitive—grants are few and far between, which doesn’t always foster shared best practices. But achieving the SDGs by 2030 must be a collaborative effort. Problems like climate change and food security are more pressing than ever, and they require an entirely new way of thinking about global development—finding and building on opportunities from proven results. Later this fall, look out for our participants’ moonshot memos as we roll them out. And if you have an idea about meeting the SDGs with a moonshot—or something else—why not submit it? Aiming at the moon is one thing, but getting there takes dedicated and sustained collaboration, and we’re so honored that these daring organizations want to work with us to do just that.

The Day One Project is going international!

The Day One Project is going international! My colleague Josh Schoop and I will be spending this week in Mexico City with our partners at Unlock Aid, where we’ll be co-hosting the Reimagining the Future of Global Development Moonshot Accelerator. This will be our eighth accelerator cohort, and the very first in-person group.

We’re convening a group of 70 entrepreneurs, innovators, policymakers, and funders from around the world to think big about the future of global development and how government, business, industry, and aid can meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. With the recent passage of a historic investment in the transition away from fossil fuels, the time is now to act on the biggest threats facing humanity. Sitting squarely within ‘the decade of delivery’—the remaining years we have to achieve the SDGs— this moonshot accelerator serves as an important call for action.

Our goal for this accelerator is to disrupt. We aim to generate new models to seed, scale, and implement catalytic solutions. The inspiration for the design of this accelerator comes from the “moonshot” model that the Kennedy administration pioneered to put the first man on the moon. A moonshot has since come to mean solving a daunting problem in an accelerated time period, requiring breakthrough, innovative, and radical thinking. If the past decades have not delivered the necessary change, then we have to shoot for the moon.

Over the course of the week, we’ll be working with the accelerator cohort to develop their own moonshots in health, the green economy, biodiversity, food and water insecurity, and more. These moonshots will be the building blocks for a Global Development Outcomes Marketplace, pitching funders and policymakers on new ways to unlock innovation in global development. Innovation here involves so much more than just new technology – it means new systems, processes, cooperation, organizing, and change, while ensuring that diverse perspectives are leading the way forward.

We’re really invested in these ideas and the people driving them, so here’s a sneak peek at a couple innovative groups joining us in Mexico City: Instiglio, headquartered in Bogotá, Colombia, is experimenting with new global development systems, like innovative financing methods, while SwipeRx in Indonesia is dedicated to revolutionizing the pharmacy industry with a tech-based solution. There are, of course, so many more groups who’ll be discussing and testing their ideas in-person, and the goal is to channel this cohort’s diverse expertise to create high-level, actionable recommendations for funders and multilateral organizations that center equity and outcomes.

I’m most excited to hear from experts and entrepreneurs from all over the world on what has been holding back progress despite attempted solutions, and I look forward to collaborating on what a new set of systems could look like. I’m excited to learn from our inspiring cohort, and to build mutual understanding across sectors to find ways to improve current solutions and break ground on a new path forward.I have high hopes that this accelerator will reinvigorate global development and uplift new voices and ideas in order to build a more prosperous planet. I resonate strongly with the voices of young people demanding urgent climate action worldwide–it’s time to harness this momentum to make sustainable, transformative change. Follow the journey of our first in-person accelerator on Twitter.

A Convening on The Future of U.S. Infrastructure Innovation

Background and Purpose

On July 26, 2022, MIT Mobility Initiative, MIT Washington Office, and The Engine hosted a workshop with leaders from the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) and infrastructure stakeholders — industry veterans, startup founders, federal, state and local policymakers and regulators, academics and investors.

The purpose of this convening was to engage a broad, diverse set of stakeholders in a series of ideation exercises to imagine what a set of ambitious advanced research programs could focus on to remake the future of American infrastructure. This read-out builds on a partnership FAS and the Day One Project have with the Department of Transportation to support solutions-based research and development. You can learn more about our work here.

The workshop consisted of two sessions. In the first working session, attendees discussed key challenges in infrastructure and possible research priority areas for ARPA-I. In the second half of the first session, participants were asked to come up with priority program areas that ARPA-I could focus on

During the second working session, participants considered the barriers that prevent the translation of breakthrough science and engineering into infrastructure reality, and opportunities for ARPA-I to smooth some of those frictions as an institution.

Resulting Recommendations

While some of the recommendations below may ultimately fall outside of ARPA-I’s mandate, or may require further Congressional authorization, they emphasize the need for ARPA-I to be strategically coordinating future deployment at scale even at the earliest stages of a project.

Deploying capital strategically

- Use existing or new authorities, such as consortium Other Transactions Authority, prize challenges, and public-private capital matching to ensure maximum flexibility and capital availability to fund complex, capital-intensive infrastructure investments.

- Create an Office of Scale-up within ARPA-I to ensure coordination across all “valleys of death” from early-stage basic research to full scale deployment. Mechanisms can range from early-stage open seed topics to later-stage Scale-up and deployment loan contracting mechanisms.

Establishing development and test infrastructure:

- The costs of infrastructure testbeds are prohibitive for most innovators. Creating government-sponsored testbeds, with participation from standards and regulatory bodies, would decrease the need for private capital and could create early linkages between innovators and those in charge of deployment. Existing national labs may have relevant expertise and equipment. Opening up access to these facilities through consortia, lighter weight Cooperative Research and Development Agreements (CRADAs), or other low-friction mechanisms may also have similar effects.

Catalyzing stakeholder collaboration:

- For early-stage researchers, create a community to share, discuss, and reflect upon the innovative landscape of infrastructure projects. To help reduce later-stage friction, create an Office of Strategic Engagement that would report to the ARPA-I director. This office would coordinate ARPA-I investment areas with external stakeholders, including academia, corporate partners, regulatory bodies, and, perhaps, even local community deployment advocacy.