Empowering States for Resilient Infrastructure by Diffusing Federal Responsibility for Flood Risk Management

State and local failure to appropriately integrate flood risk into planning is a massive national liability – and a massive contributor to national debt. Though flooding is well recognized as a growing problem, our nation continues to address this threat through reactive, costly disaster responses instead of proactive, cost-saving investments in resilient infrastructure.

President Trump’s Executive Order (EO) on Achieving Efficiency Through State and Local Preparedness introduces a nationally strategic opportunity to rethink how state and local governments manage flood risk. The EO calls for the development and implementation of a National Resilience Strategy and National Risk Register, emphasizing the need for a decentralized approach to preparedness. To support this approach, the Trump Administration should mandate that state governments establish and fund flood infrastructure vulnerability assessment programs as a prerequisite for accessing federal flood mitigation funds. Modeled on the Resilient Florida Program, this policy would both improve coordination among federal, state, and local governments and yield long-term cost savings.

Challenge and Opportunity

President Trump’s aforementioned EO signals a shift in national infrastructure policy. The order moves away from a traditional “all-hazards” approach to a more focused, risk-informed strategy. This new framework prioritizes proactive, targeted measures to address infrastructure risks. It also underscores the crucial role of state and local governments in enhancing national security and building a more resilient nation—emphasizing that preparedness is most effectively managed at subnational levels, with the federal government providing competent, accessible, and efficient support.

A core provision of the EO is the creation of a National Resilience Strategy to guide efforts in strengthening infrastructure against risks. The order mandates a comprehensive review of existing infrastructure policies, with the goal of recommending risk-informed approaches. The EO also directs development of a National Risk Register to document and assess risks to critical infrastructure, thereby providing a foundation for informed decision-making in infrastructure planning and funding.

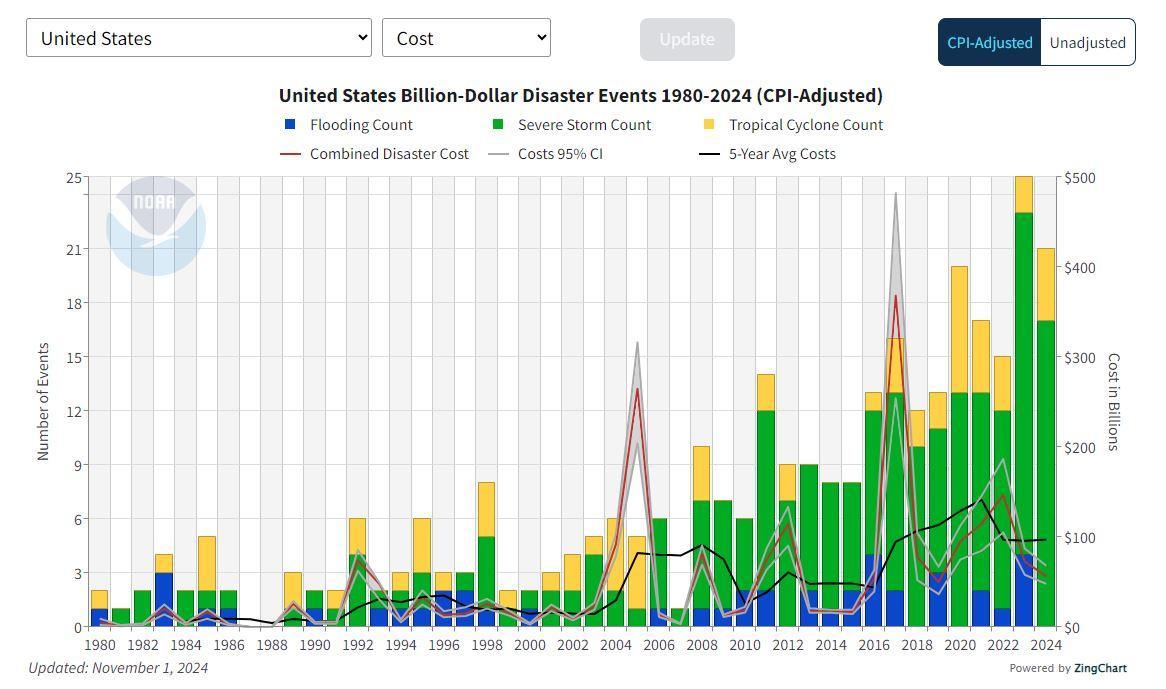

In carrying out these directives, the risks of flooding on critical infrastructure must not be overlooked. The frequency and cost of weather- and flood-related disasters are increasing nationwide due to a combination of heightened exposure (infrastructure growth due to population and economic expansion) and vulnerability (susceptibility to damage). As shown in Figure 1, the cost of responding to disaster events such as flooding, severe storms, and tropical cyclones has risen exponentially since 1980, often reaching hundreds of billions of dollars annually.

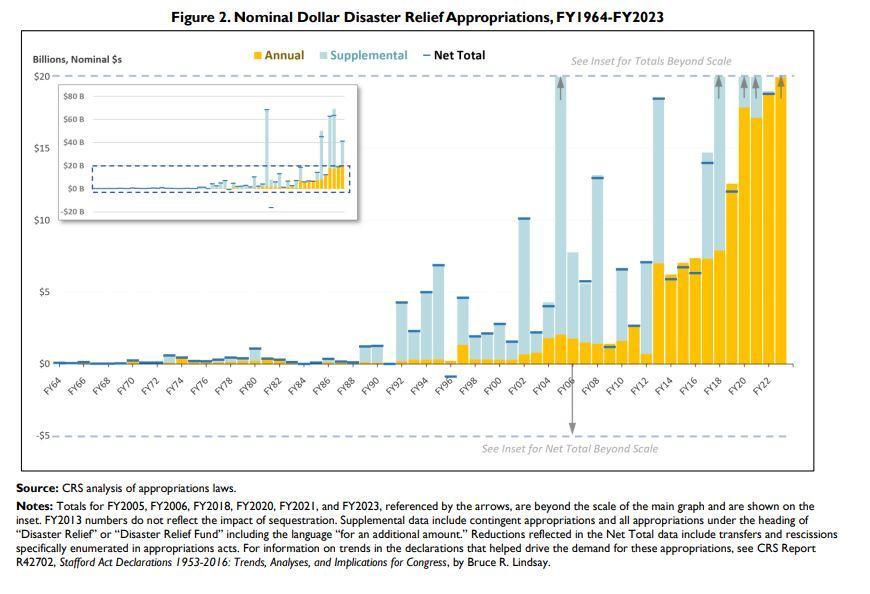

Financial implications for the U.S. budget have also grown. As illustrated in Figure 2, federal appropriations to the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) have surged in recent decades, driven by the demand for critical response and recovery services.

Infrastructure across the United States remains increasingly vulnerable to flooding. Critical infrastructure – including roads, utilities, and emergency services – is often inadequately equipped to withstand these heightened risks. Many critical infrastructure systems were designed decades ago when flood risks were lower, and have not been upgraded or replaced to account for changing conditions. The upshot is that significant deficiencies, reduced performance, and catastrophic economic consequences often result when floods occur today.

The costs of bailing out and patching up this infrastructure time and time again under today’s flood risk environment have become unsustainable. While agencies like the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) maintain and publish extensive flood risk datasets, no federal requirements mandate state and local governments to integrate this data with critical infrastructure data through flood infrastructure vulnerability assessments. This gap in policy demonstrates a disconnect between federal, state, and local efforts to protect critical infrastructure from flooding risks.

The only way to address this disconnect, and the recurring cost problem, is through a new paradigm – one that proactively integrates flood risk management and infrastructure resilience planning through mandatory, comprehensive flood infrastructure vulnerability assessments (FIVAs).

Multiple state programs demonstrate the benefits of such assessments. Most notably, the Resilient Florida Program, established in 2021, represents a significant investment in enhancing the resilience of critical infrastructure to flooding, rainfall, and extreme storms. Section 380.093 of the Florida Statutes requires all municipalities and counties across the state to conduct comprehensive FIVAs in order to qualify for state flood mitigation funding. These assessments identify risks to publicly owned critical and regionally significant assets, including transportation networks; evacuation routes; critical infrastructure; community and emergency facilities; and natural, cultural, and historical resources. To support this requirement, the Florida Legislature allocated funding to ensure municipalities and counties could complete the FIVAs. The findings then quickly informed statewide flood mitigation projects, with over $1.8 billion invested between 2021 and 2024 to reduce flooding risks across 365 implementation projects.

To support the National Resilience Strategy and Risk Register, the Trump Administration should consider leveraging Florida’s model on a national scale. By requiring all states to conduct FIVAs, the federal government can limit its financial liability while advancing a more efficient and effective model of flood resilience that puts states and localities at the fore.

Rather than relying on federal funds to conduct these assessments, the federal government should implement a policy mandate requiring state governments to establish and fund their own FIVA programs. This mandate would diffuse federal responsibility of identifying flood risks to the state and local levels, ensuring that the assessments are tailored to the unique geographic conditions of each region. By decentralizing flood risk management, states can adopt localized strategies that better reflect their specific vulnerabilities and priorities.

These state-led assessments would, in turn, provide a critical foundation for informed decision-making in national infrastructure planning, ensuring that federal investments in flood mitigation and resilience are targeted and effective. Specifically, the federal government would use the compiled data from state and local assessments to prioritize funding for projects that address the most pressing infrastructure vulnerabilities. This would enable federal agencies to allocate resources more efficiently, directing investments to areas with the highest risk exposure and the greatest potential for cost-effective mitigation. A standardized federal FIVA framework would ensure consistency in data collection, risk evaluation, and reporting across states. This would facilitate better coordination among federal, state, and local entities while improving integration of flood risk data into national infrastructure planning.

By implementing this strategy, the Trump Administration would reinforce the principle of shared responsibility in disaster preparedness and resilience, encouraging state and local governments to take the lead in safeguarding critical infrastructure. State-led FIVAs would also deliver significant long-term cost savings, given that investments in resilient infrastructure yield a substantial return on investment. (Studies show a 1:4 ratio of return on investment, meaning every dollar spent on resilience and preparedness saves $4 in future losses.) Finally, requiring FIVAs would build a more resilient nation, ensuring that communities are better equipped to withstand the increasing challenges posed by flooding and that federal investments are safeguarded.

Plan of Action

The Trump Administration can support the National Resilience Strategy and National Risk Register by taking the following actions to promote state-led development and adoption of FIVAs.

Recommendation 1. Create a Standardized FIVA Framework.

President Trump should direct his Administration, through an interagency FIVA Task Force, to create a standardized FIVA framework, drawing on successful models like the Resilient Florida Program. This framework will establish consistent methodologies for data collection, risk evaluation, and reporting, ensuring that assessments are both thorough and adaptable to state and local needs. An essential function of the task force should be to compile and review all existing federally maintained datasets on flood risks, which are maintained by agencies such as FEMA, NOAA, and USACE. By centralizing this information and providing streamlined access to high-quality, accurate data on flood risks, the task force will reduce the burden on state and local agencies.

Recommendation 2. Create Model Legislation.

The FIVA Task Force, working with leading organizations such as the American Flood Coalition (AFC), and Association of State Floodplain Managers (ASFPM), should create model legislation that state governments can adapt and enact to require local development and adoption of FIVAs. This legislation should outline the requirements for conducting assessments, including which infrastructure types need to be evaluated, what flood risk scenarios need to be considered, and how the findings must be used to guide infrastructure planning and investments.

Recommendation 3. Spur Uptake and Establish Accountability and Reporting Mechanisms.

Once the FIVA framework and model legislation are created, the Administration should require states to enact FIVA laws in order to be eligible for receiving federal infrastructure funding. This requirement should be phased in on clear and feasible timelines, with clear criteria for what provisions FIVA laws must include. Regular reporting requirements should also be established, whereby states must provide updates on their progress in conducting FIVAs and integrating findings into infrastructure planning. Updates should be captured in a public tracking system to ensure transparency and hold states accountable for completing assessments on time. Federal agencies should evaluate federal infrastructure funding requests based on the findings from state-led FIVAs to ensure that investments are targeted at areas with the highest flood risks and the greatest potential for resilience improvements.

Recommendation 4. Use State and Local Data to Shape Federal Policy.

Ensure that the results of state-led FIVAs are incorporated into future updates of the National Resilience Strategy and Risk Register, as well as other relevant federal policy and programs. This integration will provide a comprehensive view of national infrastructure risks and help inform federal decision-making and resource allocation for disaster preparedness and response.

Conclusion

The Trump Administration’s EO on Achieving Efficiency Through State and Local Preparedness opens the door to comprehensively rethink how we as a nation approach planning, disaster risk management, and resilience. Scaling successful approaches from states like Florida can deliver on the goals of the EO in at least five ways:

- Empowering state and local governments to take the lead in managing flood risks, ensuring that assessments and strategies are more reflective of local needs and conditions.

- Distributing the responsibility for identifying and mitigating flood risks across all levels of government, reducing the burden on the federal government and allowing more tailored, efficient responses.

- Reducing disaster response costs by prioritizing proactive, risk-informed planning over reactive recovery efforts, leading to long-term savings.

- Strengthening infrastructure resilience by making vulnerability assessments a condition for federal funding, driving investments that protect communities from flooding risks.

- Fostering greater accountability at the state and local levels, as governments will be directly responsible for ensuring that infrastructure is resilient to flooding, leading to more targeted and effective investments.

“Melbourne Florida Flooding” by highlander411 is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

- Several states have enacted policies advancing FIVAs or resilience programming, demonstrating this type of program could readily achieve bipartisan support.

The Resilient Florida Program, established in 2021, marks the state’s largest investment in preparing communities for the impacts of intensified storms and flooding. This program includes mandates and grants to analyze, prepare for, and implement resilience projects across the state. A key element of the program is the required vulnerability assessment, which focuses on identifying risks to critical infrastructure. Counties and municipalities must analyze the vulnerability of regionally significant assets and submit geospatial mapping data to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). This data is used to create a comprehensive, statewide flooding dataset, updated every five years, followed by an annual Resilience Plan to prioritize and fund critical mitigation projects.

In Texas, the State Flood Plan, enacted in 2019, initiated the first-ever regional and state flood planning process. This legislation established the Flood Infrastructure Fund to support financing for flood-related projects. Regional flood planning groups are tasked with submitting their regional flood plans to the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB), starting in January 2023 and every five years thereafter. A central component of these plans is identifying vulnerabilities in communities and critical facilities within each region. Texas has also developed a flood planning data hub with minimum geodatabase standards to ensure consistent data collection across regions, ultimately synthesizing this information into a unified statewide flood plan.

The Massachusetts Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness (MVP) Program, established in 2016, requires all state agencies and authorities, and all cities and town, to assess vulnerabilities and adopt strategies to increase the adaptive capacity and resilience of critical infrastructure assets. The Massachusetts model reflects an incentive-based approach that encourages municipalities to conduct vulnerability assessments and create actionable resilience plans with technical assistance and funding. The state awards communities with funding to complete vulnerability assessments and develop action-oriented resilience plans. Communities that complete the MVP program become certified as an MVP community and are eligible for grant funding and other opportunities.

- Infrastructure vulnerability assessments differ from federally mandated hazard mitigation planning programs in both scope and focus. While both aim to enhance resilience, they target different aspects of risk management.

Infrastructure vulnerability assessments are highly specific, concentrating on the resilience of individual critical infrastructure systems—such as water supply, transportation networks, energy grids, and emergency response systems. These assessments analyze the specific vulnerabilities of these assets to both acute shocks, such as extreme weather events or floods, and chronic stressors, such as aging infrastructure. The process typically involves detailed technical analyses, including simulations, modeling, and system-level evaluations, to identify weaknesses in each asset. The results inform tailored, asset-specific interventions, like reinforcing flood barriers, upgrading infrastructure, or improving emergency response capacity. These assessments are focused on ensuring that essential systems are resilient to specific risks, and they typically involve detailed contingency planning for each identified vulnerability.

In contrast, federally mandated hazard mitigation planning, such as FEMA’s programs under the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000, focuses on community-wide risk reduction. These programs aim to reduce overall exposure to natural hazards, like floods, wildfires, or earthquakes, by developing broad strategies that apply to entire communities or regions. Hazard mitigation planning involves public input, policy changes, and community-wide infrastructure improvements, which may include measures like zoning regulations, public awareness campaigns, or building codes that aim to reduce vulnerability on a large scale. While these plans may identify specific hazards, the solutions they propose are generally community-focused and may not address the nuanced vulnerabilities of individual infrastructure systems. Rather than offering a deep dive into the resilience of specific assets, hazard mitigation planning focuses on reducing overall risk and improving long-term resilience for the community as a whole.

- A proven methodology can be drawn from the Resilient Florida Program’s Standard Vulnerability Assessment Scope of Work Guidance. This methodology integrates geospatial mapping data with modeling outputs for a range of flood risks, including storm surge, tidal flooding, rainfall, and compound flooding. Communities overlay this flood risk data with their local infrastructure information – such as roads, utilities, and bridges – to identify vulnerable assets and prioritize resilience strategies.

For the nationwide mandate, this framework can be adapted, with technical assistance from federal agencies like FEMA, NOAA, and USACE to ensure consistency across regions and the integration of up-to-date flood risk data. FEMA could assist localities in adopting this methodology, ensuring that their vulnerability assessments are comprehensive and aligned with the latest flood risk data. This approach would help standardize assessments across the country while allowing for region-specific considerations, ensuring the mandate’s effectiveness in building resilience across the local, state, and national levels.

- This requirement will diffuse the responsibility of flood risk management to state and local governments by requiring them to take the lead in conducting FIVAs. Under this approach, the federal government will shift from being the primary entity responsible for identifying flood risks to a more supportive role, providing resources and guidance to state and local governments.

State governments will be required to establish and fund their own FIVAs, ensuring that each region’s unique geographic, climatic, and socioeconomic factors are considered when identifying and addressing flood risks. By decentralizing the process, states can tailor their strategies to local needs, which improves the efficiency of flood risk management efforts.

Local governments will also play a key role by implementing these assessments at the community level, ensuring that critical infrastructure is evaluated for its vulnerability to flooding. This will allow for more targeted interventions and investments that reflect local priorities and risks.

The federal government will use the data from these state and local assessments to prioritize funding and allocate resources more efficiently, ensuring that infrastructure resilience projects address the highest flood risks with the greatest potential for long-term savings.

Energy Dominance (Already) Starts at the DOE

Earlier this week, the Senate confirmed Chris Wright as the Secretary of Energy, ushering in a new era of the Department of Energy (DOE). In his opening statement before Congress, Wright laid out his vision for the DOE under his leadership—to unleash American energy and restore “energy dominance”, lead the world in innovation by accelerating the work of the National Labs, and remove barriers to building energy projects domestically. Prior to Wright’s nomination, there have already been a range of proposals circulating for how, exactly, to do this.

Of these, a Trump FERC commissioner calls for the reorganization – a complete overhaul – of the DOE as-is. This proposed reorganization would eliminate DOE’s Office of Infrastructure, remove all applied energy programs, strip commercial technology and deployment funding, and rename the agency to be the Department of Energy Security and Advanced Science (DESAS).

This proposal would eliminate crucial DOE offices that are accomplishing vital work across the country, and would give the DOE an unrecognizable facelift. Like other facelifts, the effort would be very costly – paid for by the American taxpayer, unnecessary, and a waste of public resources. Further, reorganizing DOE will waste the precious time and money of the Federal government, and mean that DOE’s incoming Secretary, Chris Wright, will be less effective in accomplishing the goals the President campaigned on – energy reliability, energy affordability, and winning the competition with China. The good news for the Trump Administration is that DOE’s existing organization structure is already well-suited and well-organized to pursue its “energy dominance” agenda.

The Cost of Reorganizing

Since its inception in 1977, the Department of Energy has evolved several times in scope and focus to meet the changing needs of the nation. Each time, there was an intent and purpose behind the reorganization of the agency. For example, during the Clinton Administration, Congress restructured the nuclear weapons program into the semi-autonomous National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to bolster management and oversight.

More recently, in 2022, another reorganization was driven by the need to administer major new Congressionally-authorized programs and taxpayer funds effectively. With the enactment of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), DOE combined existing programs, like the Loan Programs Office, with newly-authorized offices, like the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED). This structure allows DOE to hone a new Congressionally-mandated skill set – demonstration and deployment – while not diluting its traditional competency in managing fundamental research and development.

Even when they make sense, reorganizations have their risks, especially in a complex agency like the DOE. Large-scale changes to agencies inherently disrupt operations, threaten a loss of institutional knowledge, impair employee productivity, and create their own legal and bureaucratic complexities. These inherent risks are exacerbated even further with rushed or unwarranted reorganizations.

The financial costs of reorganizing a large Federal agency alone can be staggering. Lost productivity alone is estimated in the millions, as employees and leadership divert time and focus from mission-critical projects to logistical changes, including union negotiations. These efforts often drag on longer than anticipated, especially when determining how to split responsibilities and reassign personnel. Studies have shown that large-scale reorganizations within government agencies often fail to deliver promised efficiencies, instead introducing unforeseen costs and delays.

These disruptions would be compounded by the impacts an unnecessary reorganization would have on billions of dollars in existing DOE projects already driving economic growth, particularly in rural and often Republican-led districts, which depend on the DOE’s stability to maintain these investments. Given the high stakes, policymakers have consistently recognized the importance of a stable DOE framework to achieve the nation’s energy goals. The bipartisan passage of the 2020 Energy Act in the Senate reflects a shared understanding that DOE needs a well-equipped demonstration and deployment team to advance energy security and achieve American energy dominance.

DOE’s Existing Structure is Already Optimized to Pursue the Energy Dominance Agenda

In President Trump’s second campaign for office, he ran on a platform of setting up the U.S. to compete with China, to improve energy affordability and reliability for Americans, and to address the strain of rising electricity demand on the grid by using artificial intelligence (AI). DOE’s existing organization structure is already optimized to pursue President Trump’s ‘energy dominance’ agenda, most of which being implemented in Republican-represented districts.

Competition with China

As mentioned above, in response to the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), DOE created several new offices, including the Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains Office (MESC) and the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED). Both of these offices are positioning the U.S. to compete with China by focusing on strengthening domestic manufacturing, supply chains, and workforce development for critical energy technologies right here at home.

MESC is spearheading efforts to establish a secure battery manufacturing supply chain within the U.S. In September 2024, the Office announced plans to deliver over $3 billion in investments to more than 25 battery projects across 14 states. The portfolio of selected projects, once fully contracted, are projected to support over 8,000 construction jobs and over 4,000 operating jobs domestically. These projects encompass essential critical mineral processing, battery production, and recycling efforts. By investing in domestic battery infrastructure, the program reduces reliance on foreign sources, particularly China, and enhances the U.S.’s ability to compete and lead on a global scale.

In passing BIL, Congress understood that to compete with China, R&D alone is not sufficient. The United States needs to be building large-scale demonstrations of the newest energy technologies domestically. OCED is ensuring that these technologies, and their supply chains, reach commercial scale in the U.S. to directly benefit American industry and energy consumers. OCED catalyzes private capital by sharing the financial risk of early-stage technologies which speeds up domestic innovation and counters China’s heavy state-backed funding model. In 2024 alone, OCED awarded 91 projects, in 42 U.S. states, to over 160 prize winners. By supporting first-of-a-kind or next-generation projects, OCED de-risks emerging technologies for private sector adoption, enabling quicker commercialization and global competitiveness. With additional or existing funding, OCED could create next-generation geothermal and/or advanced nuclear programs that could help unlock the hundreds of gigawatts of potential domestic energy from each technology area.

Energy Affordability and Reliability

Another BIL-authorized DOE office, the Grid Deployment Office (GDO), is playing a crucial role in improving energy affordability and reliability for Americans through targeted investments to modernize the nation’s power grid. GDO manages billions of dollars in funding under the BIL to improve grid resilience against wildfires, extreme weather, cyberattacks, and other disruptions. Programs like the Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnerships (GRIP) Program aim to enhance the reliability of the grid by supporting state-of-the-art grid infrastructure upgrades and developing new solutions to prevent outages and speed up restoration times in high-risk areas. The U.S. is in dire need of new transmission to keep costs low and maintain reliability for consumers. GDO is addressing the financial, regulatory, and technical barriers that are standing in the way of building vital transmission infrastructure.

The Office of State and Community Energy Programs (SCEP), also part of the Office of Infrastructure, supports energy projects that help upgrade local government and residential infrastructure and lower household energy costs. Investments from BIL and IRA funding have already been distributed to states and communities, and SCEP is working to ensure that this taxpayer money is used as effectively as possible. For example, SCEP administers the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), which helps Americans in all 50 states improve energy efficiency by funding upgrades like insulation, window replacements, and modern heating systems. This program typically saves households $283 or more per year on energy costs.

Addressing Load Growth by Using AI

The DOE’s newest office, the Office of Critical and Emerging Tech (CET), leads the Department’s work on emerging areas important to national security like biotechnology, quantum, microelectronics, and artificial intelligence (AI). In April, CET partnered with several of DOE’s National Labs to produce an AI for Energy report. This report outlines DOE’s ongoing activities and the near-term potential to “safely and ethically implement AI to enable a secure, resilient power grid and drive energy innovation across the economy, while providing a skilled AI-ready energy workforce.”

In addition to co-authoring this publication, CET partners with national labs to deploy AI-powered predictive analytics and simulation tools for addressing long-term load growth.

By deploying AI to enhance forecasting, manage grid performance, and integrate innovative energy technologies, CET ensures that the U.S. can handle our increasing energy demands while advancing grid reliability and resiliency.

The Path Forward

DOE is already very well set up to pursue an energy dominance agenda for America. There’s simply no need to waste time conducting a large-scale agency reorganization.

In a January 2024 Letter from the CEO, Chris Wright discusses his “straightforward business philosophy” for leading a high-functioning company. As a leader, he strives to “Hire great people and treat them like adults…” which makes Liberty Energy, his company, “successful in attracting and retaining exceptional people who together truly shine.” Secretary Wright knows how to run a successful business. He knows the “secret sauce” lies in employee satisfaction and retention.

To apply this approach in his new role, Wright should resist tinkering with DOE’s structure, and instead, give employees a vision, and get off to the races of achieving the American energy dominance agenda without wasting time, the public’s money, and morale. Instead of redirecting resources to reorganizations, the DOE’s ample resources and existing program infrastructure should be harnessed to pursue initiatives that bolster the nation’s energy resilience and cut costs. Effective governance demands thoughtful consideration and long-term strategic alignment rather than hasty or superficial reorganizations.

Using Pull Finance for Market-driven Infrastructure and Asset Resilience

The incoming administration should establish a $500 million pull-financing facility to ensure infrastructure and asset resiliency with partner nations by catalyzing the private sector to develop cutting-edge technologies. The increasing frequency of extreme weather events, which caused over $200 billion in global economic losses in 2023, is disrupting global supply chains and exacerbating migration pressures, particularly for the U.S. Investing in climate resilience abroad offers a significant opportunity for U.S. businesses in technology, engineering, and infrastructure, while also supporting job creation at home.

Pull-finance mechanisms can maximize the efficiency and impact of U.S. investments, fostering innovation and driving sustainable solutions to address global vulnerabilities. Unlike traditional funding which second-guesses the markets by supporting only selected innovators, pull financing drives results by relying on the market to efficiently allocate resources to achievement, fostering competition and rewarding the most impactful solutions. Managed and steered by the U.S. government, the pull-financing facility would fund infrastructure and asset resiliency results delivered by the world’s cutting-edge innovators, mitigating the effects of extreme weather events and ultimately supporting U.S. interests abroad.

Challenge and Opportunity

The increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events pose significant risks to global economic stability, with direct implications for U.S. interests. In 2023 alone, natural disasters caused over $200 billion in global economic losses with much of the damage concentrated in regions critical to global supply chains. U.S. businesses that depend on these supply chains face rising costs and disruptions, which translate into higher costs for U.S. businesses and consumers, undermining economic competitiveness.

Beyond the economic dimension, these vulnerabilities exacerbate socio-political pressures. Climate-induced displacement is accelerating, with 32.6 million people internally displaced by disasters in 2022. Most displaced individuals that cross borders migrate to countries neighboring their own, which are ill-equipped to handle the influx, often further destabilizing fragile states. For the U.S., this translates into increased migration pressures at its southern border, where natural disasters are already a driving force behind migration from Central America. Addressing these root causes through proactive resiliency investments abroad would reduce long-term strain on the U.S. and bolster stability in strategically important regions.

In addition to economic and social risks, resilience is now a key front in global competition. The People’s Republic of China has rapidly expanded its influence in developing nations through initiatives like the Belt and Road, financing over $200 billion in energy and infrastructure projects since 2013. A significant portion of these projects focus on resiliency investments, enabling China to position itself as a partner of choice for nations with asset and infrastructure exposure. This growing influence comes at the expense of U.S. global leadership.

In the context of these challenges, it is especially concerning that much of the U.S.’s existing spending may not be achieving the results it could. A recent audit of USAID climate initiatives highlights concerns around limited transparency and effectiveness in its development funding. The inefficient use of this funding is leaving opportunities on the table for U.S. businesses and workers. Global investments in adaptation and resiliency are projected to reach $500 billion annually by 2050. Resilience projects abroad could open substantial markets for American engineering, technology, and infrastructure firms. For instance, U.S.-based companies specializing in resilient agriculture, flood defense systems, advanced irrigation technologies, and energy infrastructure stand to benefit from increased demand. Domestically, the manufacturing and export of these solutions could generate significant economic activity, supporting high-quality jobs and revitalizing industrial sectors.

Pull finance presents an opportunity to increase the cost effectiveness of resiliency funding—and ensure this funding achieves U.S. interests. Pull finance mechanisms like results-based financing and Advance Market Commitments (AMC) reward successful solutions that meet specific criteria, promoting private sector engagement and market-driven problem-solving. Unlike traditional “push” financing, which funds chosen teams or projects directly, pull financing sets a goal and allows any innovator who reaches it to claim the reward, fostering competitive problem-solving without pre-selected winners. This approach includes various mechanisms – such as prize challenges, milestone payments, advance market commitments, and subscription models – each suited to different issues and industries.

Pull financing is particularly effective for addressing complex challenges with unclear or emerging solutions, or in areas with limited commercial incentives. It has proven successful in various contexts, such as the first Trump Administration’s rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines through Operation Warp Speed and GAVI’s introduction of the pneumococcal vaccine in low-income countries. These initiatives highlight how pull financing can stimulate breakthrough innovations that efficiently address immediate needs in collaboration with private actors through effective incentives.

Pull finance can be used to efficiently advance infrastructure and asset resilience goals while also providing opportunities for U.S. innovators and industry. By stimulating demand for critically needed technologies for development like resilient seeds and energy storage solutions, as detailed in Box 1, well-designed pull finance would help link U.S. technology innovators to addressing needs of U.S. partners. As such, pull finance can play a critical role in positioning the U.S. as a partner of first choice for countries seeking to access U.S. innovation to meet resilience needs.

What would the design of a pull financing mechanism look like in practice?

Resilient Seeds

Agriculture in Africa is highly susceptible to extreme weather events, with limited adoption of effective farming technologies. Developing new seed varieties capable of withstanding these events and optimizing resource use has the potential to yield significant societal benefits.

While push financing can support the development of resource-efficient and productive seeds, it often lacks the ability to ensure they meet essential quality standards, like flavor and appearance, and are user-friendly across farming, transport and marketing stages. In contrast, pull financing can effectively incentivize private sector innovation across all critical dimensions, including end-user take-up.

A pull mechanism for resilient seeds, using a milestone payment mechanism, could cover a portion of R&D costs initially, with additional payments tied to successful lab trials. Depending on the obstacles to scaling – whether they arise from the innovator/distributor side or the farmer side – a small per-user payment to the innovator or per-user subsidy could help sustain market demand.

The design and scale of a pull financing mechanism to promote the rollout of new seeds and crop varieties will largely depend on the market readiness of the various seed types involved. Establishing effective pull mechanisms for seed development is estimated to cost between $50 million and $100 million, aiming for significant outreach to farmers. Along with supporting improved livelihoods for farmers, this small investment would open opportunities for U.S. technology innovators and companies.

Pull Finance Initiative for Infrastructure and Asset Resiliency in the Caribbean

The Caribbean is one of the regions most vulnerable to extreme weather events, making it critical to engage the private sector in developing and adopting technologies suited to Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Challenges such as limited demand and high costs hinder innovation and investment in these small markets, leaving key areas like agriculture and access underserved. Overcoming these market failures requires innovative approaches to create sustainable incentives for private sector involvement.

Pull finances offers a promising solution to drive resiliency in SIDS. By tying payments to measurable outcomes, this approach will incentivize the development and deployment of technologies that might otherwise remain inaccessible.

For example, pull finance could be used to stimulate the creation of energy storage solutions designed to withstand extreme weather conditions in remote areas. This could be help address the critical needs of SIDS’ such as Guyana which face energy security challenges linked to extreme weather conditions, especially in remote and dispersed areas. Energy storage technologies exist, but companies are not motivated to invest in tailored innovation for local needs because end-users cannot pay prices that compensate for innovation efforts. Pull finance could address this by committing to purchase an amount large enough that nudges companies to develop a tailored product, without raising market prices. Success would require partnerships with local SMEs, caps in installation costs, and specifications on storage capacity, along with relevant technology partners such as those in the U.S.. This approach would support immediate adaptation needs and lay the foundation for sustainable, market-driven solutions that ensure long-term resilience for SIDS.

Plan of Action

The new administration should establish a dedicated pull-financing facility to accelerate the scale-up and deployment of development solutions with partner nations. In line with other major U.S. climate initiatives, this facility could be managed by USAID’s Bureau for Resilience, Environment and Food Security (REFS), with significant support from USAID’s Innovation, Technology, and Research (ITR) Hub, in partnership with the U.S. Department of State. By leveraging USAID’s deep expertise in development and SPEC’s strategic diplomacy, this collaboration would ensure the facility addresses LMIC-specific needs while aligning with broader U.S. objectives.

The recent audit of USAID climate initiatives referenced above highlights concerns on the limited transparency and effectiveness in its climate funding. Thus, we recommend that USAID assesses the impact of its climate spending under the 2020-2024 administration and reallocates a portion of funds from less effective or stalled initiatives to this new facility. We recognize that it may be challenging to quickly identify $500 million in underperforming projects to close and reassign. Therefore, in addition to reallocating existing resources, we strongly recommend appealing to new funding for this initiative. This approach will ensure the new facility has the financial backing it needs to drive meaningful outcomes. Additional resources could also be sourced from large multilateral organizations such as the World Bank.

To enhance the facility’s impact, we recommend the active participation of agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOOA), particularly through the Climate and Societal Interactions Division (CSI) in the Steering Committee,

We propose that this facility draw on the example of the UK’s planned Climate Innovation Pull Facility (CIPF), a £185 million fund which aims to fund development-relevant pull finance projects in LMICs such as those proposed by the Center for Global Development and Instiglio. This can be achieved through the following steps:

Recommendation 1. Establish the pull-finance facility, governance and administration with an initial tranche of $500 million.

The initiative proposes establishing a pull-finance facility with an initial fund of $500 million. This facility will be overseen by a steering board chaired by USAID and comprising senior representatives from USAID, the State Department, NOOA , which will set the strategic direction and make final project selections.

A facility management team, led by USAID, will be responsible for ensuring the successful implementation of the facility, including the selection and delivery of 8 to 16 projects. The final number of projects will depend on the launch readiness of prioritized technologies and their potential impact, with the selection process guided by criteria that align with the facility’s strategic goals. The facility management team will also be responsible for contracting with project and evaluation partners, compliance with regulations, risk management, monitoring and evaluation, as well as payouts. Additionally, the facility management team will provide incubation support for selected initiatives, including technical consultations, financial modeling, contracting expertise, and feasibility assessments.

Designing pull financing mechanisms is complex and requires input from specialized experts, including scientists, economists, and legal advisors, to identify suitable market gaps and targets. An independent Technical Advisory Group (TAG) led by USAID and comprised of such experts should be established to provide technical guidance and quality assurance. The TAG will identify priority resilience topics, such as reducing crop-residue burning or developing resilient crops. It will also focus on sectors where the U.S. can enhance its global competitiveness, which faces high upfront costs and risks. Additionally, the TAG will be responsible for technical review and recommendations of the shortlisted project proposals to inform final selection, as well as provide general advice and challenge to the facility management team and steering board.

We suggest starting with $500 million as the minimum required to be credible and relevant as well as responsive to the scale of global need. Further, experience shows that pull mechanisms need to be of sufficient scale to sustainably shift markets. For instance, GAVI’s pneumococcal vaccine AMC entailed a $1.5 billion commitment and Frontier’s carbon capture AMC likewise entails over $1 billion in commitments.

Recommendation 2. Set up a performance management system to measure, assess and ensure impact.

The U.S. pull financing facility will implement a robust monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) framework to track and enhance its impact and drive ongoing improvement through feedback and learning.

The facility manager will develop a logical framework (logframe) that includes key performance indicators (KPIs) and a progress and risk dashboard to track monthly performance. These tools will enable effective monitoring of progress, assessment of impact, and proactive risk management, allowing for quick responses to unexpected challenges or underperformance.

Monthly check-ins with an independent evaluation partner, along with oversight from a dedicated MEL committee, will ensure consistent and rigorous evaluation as well as continuous learning. Additionally, knowledge management and dissemination activities will facilitate the sharing of insights and best practices across the program.

Recommendation 3. Establish a knowledge management hub to facilitate the sharing of results and insights and ensure coordination across pull-financing projects.

The hub will work closely with community partners and stakeholders – such as industry and tech leaders and manufacturers – in areas like resiliency-focused finance and innovation to build strong support and develop resources on essential topics, including the effectiveness of pull financing and optimal design strategies. Additionally, the hub will promote collaboration across projects focused on similar technological and production advancements, generating synergies that enhance their collective impact and benefits.

Once the proof of concept is established through clear evidence and learning, the facility will likely secure further stakeholder buy-in and attract additional funding for a scale up phase covering a larger portfolio of projects.

Conclusion

The federal government should establish a $500 million pull-financing facility to accelerate technologies for resilience in the face of growing development challenges. This initiative will unlock high-return investments and increase cost effectiveness of resiliency spending, driving economic and geopolitical goals. Managed and steered by USAID and the State Department, with support from NOOA, the facility would foster breakthroughs in critical areas like resilient infrastructure, energy, and technology, benefiting both U.S. businesses and our international partners. By investing strategically, the U.S. can ensure both national and global stability.

The authors thank FAS for the reviews and feedback, along with Ranil Dissanayake, Florence Oberholtzer, and Laura Mejia Villada for their valuable contribution to this piece.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Pull financing mechanisms, such as prize competitions, milestone payments, and Advanced Market Commitments (AMCs) often face regulatory and legal challenges due to their dependency on successful outcomes for funding disbursement (CGD, 2021; CGD, 2023). First, it can make cashflow management challenging as federal law requires that legally binding financial commitments be made if the necessary appropriated funds are available, resulting in upfront scoring of costs, even if the actual expenditures occur years later. The uncertainty surrounding innovation and payouts can also create risk aversion, as most funding accounts are not “no-year” accounts, meaning committed funds can expire if competition goals are unmet within the designated timeframe.

To mitigate these constraints, agencies can use budgetary workarounds like no-year appropriations, allowing them to reallocate de-obligated funds from canceled competitions to new initiatives. Other options include employing credit-type scoring to discount costs based on the likelihood of non-payment and making non-legally binding commitments backed by third parties, such as international institutions, to avoid these challenges altogether.

The entire fund is expected to span a maximum of five () years. The initial 12 months will concentrate on identifying eight (8) to 16 projects through comprehensive due diligence and providing incubation support. In the subsequent four (4) years, the focus will shift to project delivery.

In contrast to the traditional push-funding approach of the CFDA program, our proposed pull-finance initiative introduces a unique market-shaping component aimed at driving key infrastructure and resilience solutions to fruition. In contrast to CFDA, pull finance addresses demand-side risks by providing demand-side guarantees of a future market for the technology or solution. It also mitigates R&D risk by combining incentives for research and development, ensuring that a viable market exists once the technology is developed. This approach helps accelerate market creation and innovation in high-risk, high-innovation sectors where demand or technological maturity is uncertain.

Shifting Federal Investments to Address Extreme Heat Through Green and Resilient Infrastructure

“Under the President’s direction, every Federal department and agency is focused on strengthening the Nation’s climate resilience, including by tightening flood risk standards, strengthening building codes, scaling technology solutions, protecting and restoring our lands and waters, and integrating nature-based solutions.” – National Climate Resilience Framework

Now more than ever, communities across the country need to adopt policies and implement projects that promote climate resilience. As climate change continues to impact the planet, extreme heat has become more frequent. To address this reality, the federal government needs to shift as much of its infrastructure investments as possible away from dark and impervious surfaces and toward cool and pervious “smart surfaces.”

By ensuring that a more substantial portion of federal infrastructure investments are designed to address extreme heat and climate change, instead of exacerbating the problem like many investments are doing now, the government can ensure healthy and livable communities. Making improvements, such as coating black asphalt roads with higher albedo products, installing cool roofs, and increasing tree and vegetative cover, results in positive social, political, and economic effects. Investments in safe and resilient communities provide numerous benefits, including better health outcomes, higher quality of life, an increase in proximal property values, and a reduction in business disruption. By making these changes, policymakers will engender significant long-term benefits within communities.

Challenge and Opportunity

Extreme heat events—a period of high heat and humidity with temperatures above 90°F for at least two to three days—are the leading cause of weather-related fatalities in the United States among natural disasters. Recent surges in extreme heat have led to summers now commonly 5–9°F hotter city-wide, with some neighborhoods experiencing as much as 20°F higher temperatures than rural areas, an outcome commonly referred to as the urban heat island (UHI) effect. More than 80% of the U.S. population lives in cities experiencing these record-breaking temperatures.

Extreme Heat and External Impacts

As populations in urban areas continue to grow, their density will further increase the urban heat island effect and exacerbate heat inequities in the absence of more resilient infrastructure investments. Between 2004 and 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recorded 10,527 heat-related deaths in the United States, an average of 702 per year. In their report, the CDC emphasized that many of these deaths occurred in urban areas, particularly in low-income and communities of color. Lower-income neighborhoods commonly have fewer trees and darker surfaces, resulting in temperatures often 10–20°F hotter than wealthy neighborhoods with more trees and green infrastructure.

A wide range of other consequences result from the rise in urban heat islands. For instance, as we experience hotter days, the warming atmosphere traps in more moisture, resulting in episodes of extreme flooding. Communities are experiencing a variety of impacts such as personal property damage, infrastructure destruction, injury, and increasing morbidity and mortality. In addition to the health impacts of extreme heat, increases in urban flooding also lead to long-term impacts such as disease outbreaks and economic instability due to the destruction of businesses. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), annual damages from flooding are expected to increase by 30% by the end of the century, making it more difficult for communities, particularly low-income and communities of color, to rebuild. Implementing climate-resilient solutions for extreme heat provides multiplicative benefits that extend beyond the singular issue of heat.

Integrating Climate Resilience in All Federal Funding Grants and Investments

As urban heat islands continue to expand in urban communities due to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions and investments in dark and impervious surfaces, it is vital that the federal government integrate climate resilience into all federal funding grants and investments. Great progress has been made by the Biden Administration via the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and other policy interventions that have created regulations and grant programs that promote and adopt climate-resilience policies. However, many federal investments continue to promote dark and impervious surfaces rather than requiring cooler and greener infrastructure in all projects. Investing in more sustainable resilient infrastructure is an important step toward combating urban heat islands and extreme flooding. Therefore, federal agencies such as the EPA, Department of Transportation (DOT), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Department of Energy (DOE), and others should be encouraged to adopt a standard for integrating climate resiliency into all federal projects by funding green infrastructure and cool surface projects within their programs.

Strengthening Climate Policy

To address extreme heat, federal agencies should fund nature-based, light-colored, and pervious surfaces and shift away from investing in darker and more impervious surfaces. This redirection of funds will increase the cost-effectiveness of investments and yield multiplicative co-benefits.

Mitigating extreme heat through investments in green and cool infrastructure will result in better livability, enhanced water and air quality, greater environmental justice outcomes, additional tourism, expansion of good jobs, and a reduction in global warming. As an example, in 2017, New York City initiated the Cool Neighborhoods NYC program to combat heat islands by installing more than 10 million square feet of cool roofs in vulnerable communities, which also resulted in an estimated reduction of internal building temperatures by more than 30%.

Similarly, in the nation’s capital, DC Water’s 2016 revision of its consent decree to integrate green with gray infrastructure in the $2.6 billion Clean Rivers Project is set to cut combined sewer overflows by 96% at a lower cost to ratepayers than a gray-infrastructure-only solution. By implementing nature-based solutions, the DC Water investment also helps to reduce the urban heat island effect and air pollution, as well as localized surface flooding. One dollar invested in green infrastructure provides many dollars’ worth of benefits.

Plan of Action

To combat extreme heat within communities, federal agencies and Congress should take the following steps.

Recommendation 1. FEMA, DOT, EPA, DOE, and other agencies should continue to shift funding to climate-resilient solutions.

Agencies should continue the advancements made in the Inflation Reduction Act and shift away from providing city and state governments with funding for more dark and impervious surfaces, and instead require that all projects include green and cool infrastructure investments in addition to any gray infrastructure deemed absolutely necessary to meet project goals. These agencies should require teams to submit a justification for funding of any dark and impervious surfaces proposed for project funding. Agencies would review the justification document to determine its validity and reject it if found invalid.

The Interagency Working Group on Extreme Heat or a similar multi agency task force should develop a guidance document to formally establish new requirements for green and cool infrastructure investments. Similar to the standards set by the Buy America and Buy Clean initiatives, the “Buy Green” document should create a plan for addressing extreme heat in federally funded projects. Once created, the document would help support additional climate-resilience frameworks such as the Advancing Climate Resilience through Climate-Smart Infrastructure Investments and Implementation Guidance memo that was released by Office of Management and Budget (OMB). While this memo provides much-needed counsel on implementing climate and smart infrastructure, its focus on extreme flooding makes it a narrow tool. The newly established Buy Green guidance will provide necessary support and information on extreme heat to implement related cool and green infrastructure.

Recommendation 2. All federal agencies should factor in the new social cost of carbon.

In December 2023, the EPA announced an updated number for the social cost of carbon – $190 per ton – as part of a new rule to limit methane emissions. The new social cost of carbon number is not yet included in federal projects for all agencies, nor in federal grant funding applications. Not updating the social cost of carbon skews federal funding and grant investments away from more climate-friendly and resilient projects. All federal agencies should move quickly to adopt the new social cost of carbon number and use the number to determine the cost-effectiveness of project concepts at all stages of review, including in environmental impact statements prepared under the National Environmental Policy Act.

Recommendation 3. The Ecosystem Services Guidance should be fully adopted by federal agencies.

In early March 2024, the OMB released guidance to direct federal agencies to provide detailed accounts of how proposed projects, policies, and regulations could impact human welfare from the environment. The Ecosystem Services Guidance is designed to help agencies identify, measure, and discuss how their actions might have an impact on the environment through a benefit-cost analysis (BCA). We recommend that FEMA, DOT, EPA, DOE, and other funding agencies adopt and implement this guidance in their BCAs. This move would complement Recommendation 2, as factoring the new social cost of carbon into the Ecosystem Services Guidance will further encourage federal agencies to consider green infrastructure technologies and move away from funding dark and impervious surfaces.

Recommendation 4. The Federal Highway Administration (FHA) should revise its list of standards to include and then promote green and cool infrastructure.

The FHA has established a list of standards to help guide organizations and agencies on road construction projects. While the standards have made progress on building more resilient roadways, much of the funding that flows through FHA to states and metro areas continues to result in more dark and impervious surfaces. FHA should include standards that promote cool and green infrastructure within their specifications. These standards should include the proposed new social cost of carbon, as well as guidance developed in partnership with other agencies (FEMA, DOT, EPA, and DOE) on a variety of green infrastructure projects, including the implementation of cool pavement products, installation of roadside solar panels, conversions of mowed grass to meadows, raingardens and bioswales, etc. In addition, we also recommend that FHA strongly consider the adoption of the CarbonStar Standard. Designed to quantify the embodied carbon of concrete, the CarbonStar Standard will supplement the FHA standards and encourage the adoption of concrete with lower embodied carbon emissions.

Recommendation 5. EPA and DOE should collaborate to increase the ENERGY STAR standard for roofing materials and issue a design innovation competition for increasing reflectivity in steep slope roofing.

Since 1992, ENERGY STAR products have saved American families and businesses more than five trillion kilowatt-hours of electricity, avoided more than $500 billion in energy costs, and achieved four billion metric tons of greenhouse gas reductions. While this has made a large impact, the current standards for low-slope roofs of initial solar reflectance of 0.65 and three-year aged reflectance of 0.50 are too low. The cool roofing market has advanced rapidly in recent years, and according to the Cool Roof Rating Council database, there are now more than 70 low-slope roof products with an initial solar reflectance above 0.80 and a three-year aged solar reflectance of 0.70 and above. EPA and DOE should increase the requirements of the standard to support higher albedo products and improve outcomes.

Similarly, there have been advancements in the steep slope roofing industry, and there are now more than 20 asphalt shingle products available with initial solar reflectance of 0.27 and above and three-year aged solar reflectance of 0.25 and above. EPA and DOE should consider increasing the ENERGY STAR standard for steep slope roofs to reward the higher performers in the market and incentivize them to develop products with even greater reflectivity in the future.

In addition to increasing the standards, the agency should also issue a design competition to promote greater innovation among manufacturers, in particular for steep slope roofing solutions. Authorized under the COMPETES Act, the competition would primarily focus on steep slope asphalt roofs, helping product designers develop surfaces that have a much higher reflectivity than currently exist in the marketplace (perhaps with a minimum initial solar reflectance target of 0.5, but with an award given to the highest performers).

Recommendation 6. Congress and the IRS should reinstate the tax credit for steep slope ENERGY STAR residential roofing.

ENERGY STAR programs are managed through Congress and the IRS, who are in charge of maintaining the standards and distributing the tax credits. Though the IRA allowed for a short-term extension of the tax credit for steep slope ENERGY STAR residential roofing, the incentive has since expired. Given the massive benefits of cool roofing for energy efficiency, climate mitigation, resilience, health, and urban heat island reduction, Congress along with the IRS should move to reinstate this incentive. Because of the multiplicative benefits, this is fundamentally one of the most important incentives that EPA/DOE/IRS could offer.

Recommendation 7. DOE or DOT should conduct testing for cool pavement products.

Currently, cities looking to reduce extreme heat are increasingly looking to cool pavement coatings as a solution but do not have the capacity to conduct third-party reviews of the products and manufacturers’ claims, and they need the federal government to provide support. Claims are being made by manufacturers in terms of the aged albedo of products and also their benefits in terms of increasing road surface longevity, but to date there has been no third party analysis to verify the claims. DOE/DOT should conduct an independent third party test of the various cool pavement products available in the marketplace.

Recommendation 8. The Biden Administration should provide support for the Extreme Heat Emergency Act of 2023.

On June 12, 2023, Representative Ruben Gallego (D-AZ) introduced the Extreme Heat Emergency Act of 2023 to amend the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act and include extreme heat in the definition of a major disaster. This bill is a vital piece of climate resilience legislation, as it recognizes the impact of extreme heat and seeks to address it federally. The Biden Administration, and FEMA in particular, should provide political support for the act given its transformative potential in addressing extreme heat in cities. Failing to update the list of hazards that FEMA can respond to with public assistance can amount to a de facto endorsement of policies and projects that harm our environment and economy. Congress should work with FEMA to alter the Stafford Act language to enable designating extreme heat as a major disaster.

Recommendation 9. Create an implementation plan for a National Climate Resilience Framework.

In September 2023, the Biden Administration issued the landmark National Climate Resilience Framework. It is our understanding that an implementation plan for the framework has not yet been developed. If that is the case, the Administration should move forward expeditiously with developing a plan that includes the proposed recommendations above and others. Ideas such as creating a standard guidance for climate resilience projects and factoring the new social cost of carbon should be included and implemented through federal investments, grants, climate action plans, legislation, and more. With help from Congress to formally enact the plan, the bill should require the Administration to issue guidance for all federal agencies referenced in the implementation plan to incorporate climate resilience in all funded projects. This would help standardize climate resilience policies to combat extreme heat and flooding.

Cost Estimates

This proposal is largely focused on redirecting current appropriations to more resilient solutions rather than requiring more budget capacity. Agencies such as FEMA, DOT, EPA, and DOE should redirect funds allocated in infrastructure budgets and grant programs that promote dark and impervious surfaces to green and cool infrastructure projects. Items that will incur additional costs are including heat in FEMA’s definitions of natural disasters, the suggested cool roof design innovation competition, and the analysis of cool pavement technologies.

Conclusion

Combating extreme heat urgently requires us to address climate resilient infrastructure at the federal level. Without the necessary changes to adopt green and cooler technologies and create a national resilience framework implementation plan, urban heat islands will continue to intensify in cities. Without a dedicated focus from the federal government, extreme heat will continue to create dangerous temperatures and also further disparities affecting low-income and communities of color who already do not have the adequate resources to stay cool. Shifting federal investments to address extreme heat through green and resilient infrastructure extends beyond political lines and would greatly benefit from policymaker support.

This idea of merit originated from our Extreme Heat Ideas Challenge. Scientific and technical experts across disciplines worked with FAS to develop potential solutions in various realms: infrastructure and the built environment, workforce safety and development, public health, food security and resilience, emergency planning and response, and data indices. Review ideas to combat extreme heat here.

How A Defunct Policy Is Still Impacting 11 Million People 90 Years Later

Have you ever noticed a lack of tree cover in certain areas of a city? Have you ever visited a city and been advised to avoid certain districts or communities? Perhaps you even recall these visual shifts occurring immediately after crossing a particular road or highway?

If so, what you experienced was likely by design:

In the early 20th century, Black communities across the U.S. were subjected to economic constraint and social isolation through housing policies that mandated segregation. Black communities were systematically excluded from the housing benefits offered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). The HOLC served as the basis of the National Housing Act of 1934, which ratified the Federal Housing Authority (FHA).

Housing policy discrimination was further exacerbated by the FHA refusing to insure mortgages near and within Black neighborhoods. The HOLC provided lenders with maps that circled areas with sizeable black populations with red markers—a practice now referred to as redlining. While the systematic practice of redlining ended in 1968 under The Fair Housing Act of 1968, redlining continues to economically impair over 11 million Americans—and less than half are Black.

You are probably thinking (1) how is this possible? (2) How could a defunct 20th-century policy designed to discriminate against Black communities still impact over 11 million—mostly non-Black—Americans today? The answer is the same for both questions: place-based discrimination.

Policies such as redlining are designed to worsen the material conditions of a target group by preventing investment in the places where they live. Over time, this results in physical locations that are systemically denied access to features such as loans, enterprise, and ecosystem services simply due to their location or place. Place-based discrimination is the principal mechanism of redlining effects, and consequently, costs taxpayers millions of dollars per year.

What is the problem?

Starting in the 1990s, during the Clinton Administration, billions of dollars in tax credits were devoted towards community development and economic growth through the use of special tax credits that attract private investments (Table 1). One of the principal agents from this funding to address place-based discrimination was the creation of Community Development Entities (CDEs). According to the New Markets Tax Credit Coalition, CDEs are private entities that have “demonstrated” an interest in serving or providing capital to low-income- communities (LICs) and individuals (LIIs). Once certified, CDEs are eligible to apply for a special tax credit, New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC), through the Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) Fund.

However, this program, and others like it, have had a negligible impact on addressing the systemic implications of redlining . A recent Urban Institute report found that inequity in capital flow and investment trends within cities (i.e., Chicago) is driven by residential lending patterns. Highlighting the inequalities that exist between investment among neighborhoods with different racial and income demographics, the analysts surmise that redressing economic downturn involves expanding investments into divested neighborhoods. To date, more than $71 billion have been awarded to CDE’s, and yet, historically-redlined areas remain economically desolate. If these programs are intended to economically revitalize historically-redlined areas, then these programs are not doing what they are supposed to do.

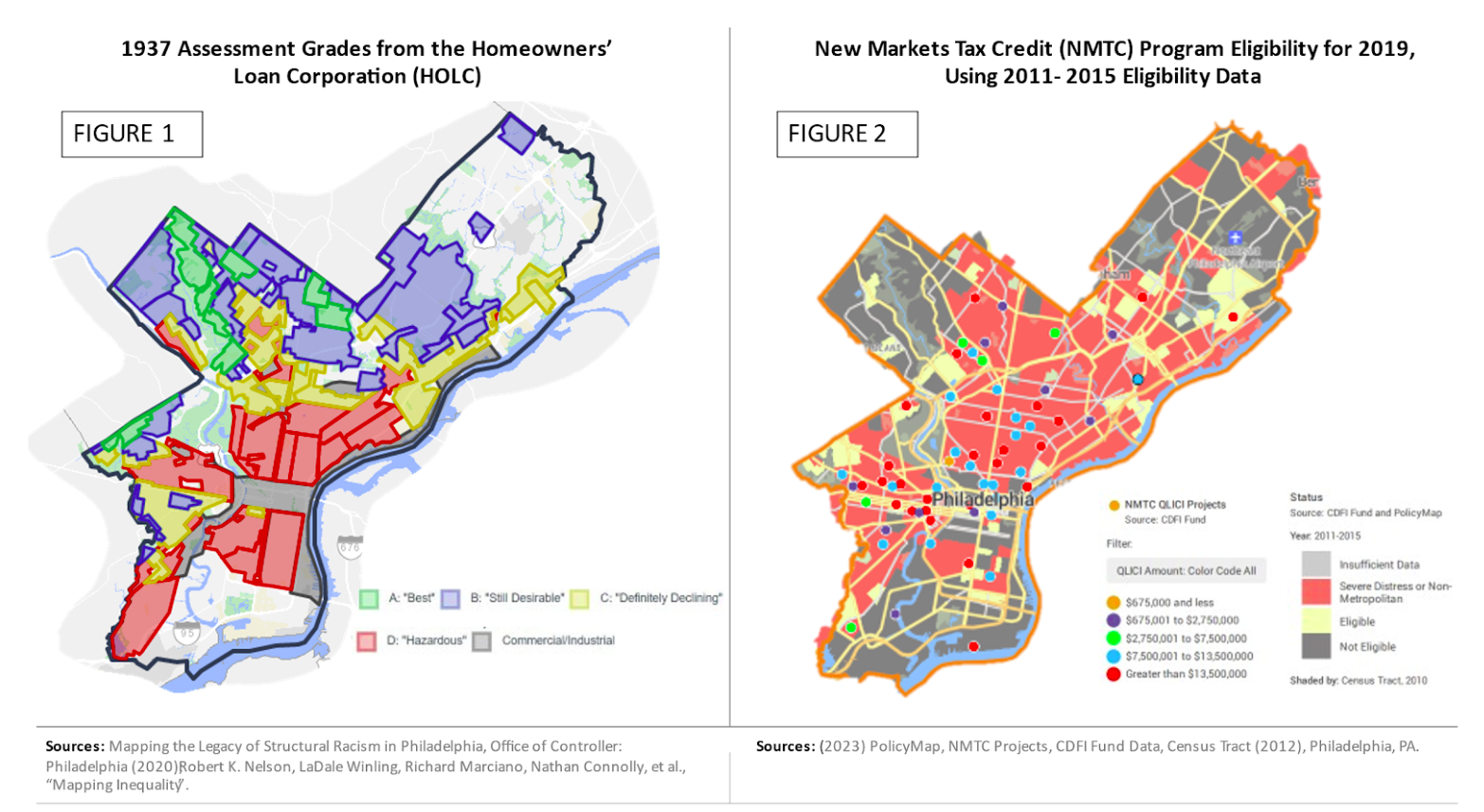

One example of this is the city of Philadelphia:

Philadelphia, a city in the top ten for redlined populations, possesses tens of thousands of vacant buildings and lots that are overlaid by redlining and riddled with brownfield sites. According to the Philadelphia Office of the Controller, historically redlined communities of Philadelphia continue to experience disproportionate amounts of poverty, poor health outcomes, limited educational attainment, unemployment, and violent crime compared to non-redlined areas in the city.

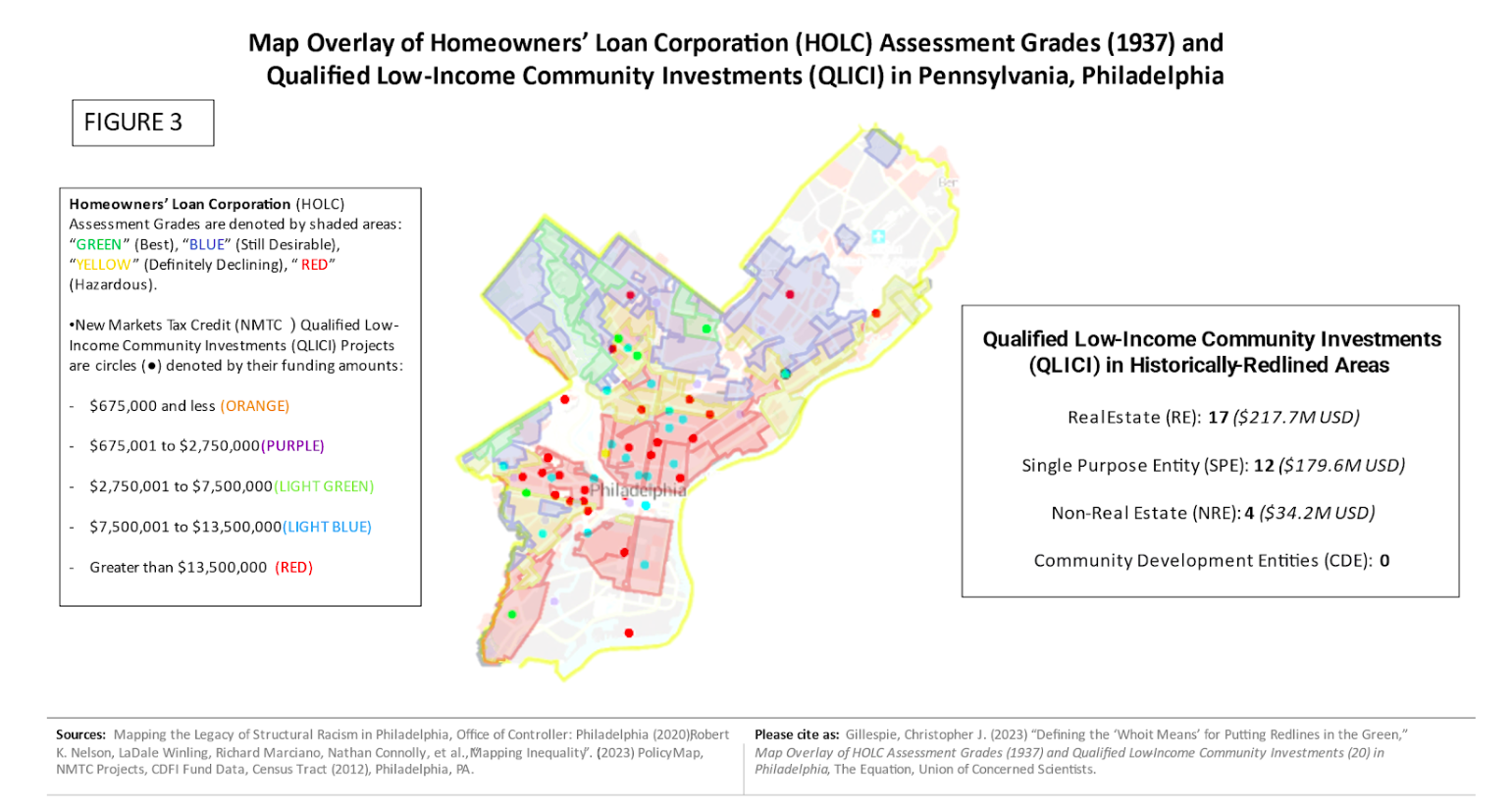

By analyzing HOLC assessment grades (1937) and New Market Tax Credit (NMTC) Program Eligibility (i.e., PolicyMap, projects from 2015-2019) for Philadelphia, PA, I found that of the 30+ Qualified Low-Income Community Investments (QLICIs) in historically-redlined areas, totaling over $400 million in tax credits, none are categorized as Community Development Entities (CDEs).

HOLC assessment grades (1937) vs. New Market Tax Credit (NMTC) Program Eligibility

Of the 30+ Qualified Low-Income Community Investments (QLICIs) in historically-redlined areas, totaling over $400 million in tax credits, none are categorized as Community Development Entities (CDEs).

Meanwhile, the Philadelphia City Council just passed a budget that allocates a record $788 million to the Philadelphia Police Department (PPD). Recent studies show that fatal encounters with police are more likely to occur within historically-redlined areas. It appears the nicest buildings in redlined areas may very well be police stations.

Yet, public investment has been more concerned with maintaining systems of oppression than reversing them. Why continue to invest in systems that do not create wealth? No matter your perception of American policing, the following is clear: policing does not create wealth for distressed communities.

Currently, there are 200+ cities and thousands of communities that are, like Philadelphia, enduring the systemic implications of redlining.

What would happen if public investments were allocated towards restorative policy actions within historically-redlined areas?

A federal program that amalgamates the best elements of community-driven inventiveness into a vehicle for innovative and sustainable economic development. That is, a program that promotes economic revitalization of historically-redlined communities through multipurpose, community-owned enterprises called Innovative Neighborhood Markets (INMs).

What is the policy action?

One thing that urban policy initiatives have made clear, is that distressed communities are prime real-estate targets for private developers . A new federal effort could ensure that investment opportunities are also accessible to community members seeking to launch place-based businesses and enterprises. Businesses and enterprises of this sort will not only reduce urban blight in historically-redlined communities, but also serve as avenues for the direct state, local, and private investment needed to address historical inequities.

The Biden-Harris Administration can combat redlining through a placed-based community investment program, coined Putting Redlines in the Green: Economic Revitalization Through Innovative Neighborhood Markets (PRITG), that affords historically-redlined communities the ability to establish their own profitable enterprise before outside parties (i.e., private developers).

These Innovative Neighborhood Markets (INMs) would be resource hubs that provide affordable grocery items (i.e., fresh produce, meats, dairy, etc.); an outlet for residents of the community to market goods and services (i.e., small businesses); and create cross-sector initiatives that build community enterprise and increase greenspace (i.e., Farm to Neighborhood Model [F2NM], parks, gardens, and tree cover). Most importantly, INM’s are community owned. Through community governance, the community elects and authorizes the types of place-based businesses and enterprises that are present within their INM.

Do you remember the Philadelphia example from earlier?

Under PTRIG, a number of those underutilized structures or vacant spaces are transformed into a vested, profitable, and sustainable community resource. The majority of the financial capital remains within the community, and economic gains are partially earmarked for community revitalization (i.e., soil remediation for brownfield sites, community restoration, and construction of greenspace).

All Taxpayers Benefit

By legally and financially empowering communities with ownership, PRITG will incentivize investment and development that can actually reduce taxpayer liability. For example, the INM can generate the funding to invest in more attractive (and expensive) treecover and landscaping that will reduce the impact of heat islands and imperviousness related to redlining, thereby reducing taxpayer liability by more than $308 million dollars per year. Implementation of PTRIG will decrease taxpayer burden through profit-driven and self-supporting community services.

“Fair and Equal” Access