Eliminating the Chassis Requirement to Free Manufactured Homes from Local Discrimination and Regulatory Dead Weight

The coastal housing problem is highly salient in the housing discourse. However, more Americans live in rural areas than in all of California and New York combined. Even in metropolitan areas, most U.S. metros still have median home prices within 125% of construction costs — meaning that construction costs matter more than growth controls and land prices for home prices there.

Unfortunately, from 1987 to 2016, single-family residential construction productivity increased only 12%. Indeed homebuilding productivity has fared uniquely badly compared to the rest of the economy throughout the postwar era. Site-built construction overall, and single-family home construction in particular, remains resistant to productivity-boosting innovations.

Enter manufactured housing, the oft-maligned (or forgotten) housing type quietly providing 8.4 million affordable homes across the country. Modern manufactured homes have strict standards for structural integrity, material durability, and safety. In recent years, administrative changes to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Code that governs manufactured home construction have allowed innovations like higher roof pitch and even limited multifamily designs to enter the market.

The Opportunity

Like cars or airplanes, manufactured homes are factory-built on an assembly line inside a controlled environment. This allows greater efficiency compared to site-built homes, where workers need to perform their duties in all weather conditions and sometimes awkward positions. Because manufactured homes are built indoors, workers can operate more efficiently and safely. This efficiency has a significant cost advantage, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, up 25-65% less than equivalent site-built construction.

Despite their efficiency advantage, manufactured homes face discriminatory barriers to fair competition with site-built construction. Many state laws and local zoning codes restrict or exclude manufactured homes, often based on architectural features common only on manufactured homes, like the congressionally-mandated permanent chassis.

The permanent chassis under every manufactured home must be retained even after permanent installation onto the land. This requirement is meant to retain nominal interstate portability, even though manufactured homes are rarely moved after they are attached to the land. The permanent chassis limits architectural flexibility by requiring the home to be installed higher off the ground to account for the chassis’s vertical height, makes basements less practical, and effectively precludes using HUD Code construction for upper floors due to the weight and bulk of the chassis.

In the past, organizations like the National Association of Homebuilders opposed reforming the HUD Code chassis requirement in an effort to protect home builders from more efficient, factory-made competition. Today, with the construction sector at full employment, this motivation for opposition has subsided.

Congress alone can eliminate the permanent chassis requirement for manufactured homes because the requirement is part of the definition of a manufactured home established by Congress. To do this, Congress must amend the definition of a manufactured home to remove the phrase “on a permanent chassis.” By doing this, Congress can eliminate wasted construction materials, allow new multifamily design options under the HUD Code, and unleash competition from factory-built manufactured housing.

Plan of Action

Identify and engage key stakeholders

- Stakeholders include National Association of Home Builders, National Association of Realtors, Manufactured Housing Institute, and other relevant organizations in the manufactured housing policy space.

- Conduct outreach to stakeholder organizations to ensure positional alignment and efficient use of resources for legislator education.

Educate legislators on the basics of manufactured homes, their role in the housing market, and their inherent efficiencies.

- Member education will take the form of in-person and virtual meetings with member and committee offices in both chambers. Members on relevant committees and a geographically diverse slate of members who are active in housing policy will be prioritized.

- Legislator education will focus on removing a federal barrier to consumer choice and allowing fair competition between different construction methods. Additional talking points will include that the reform requires no appropriation and will improve access to modest and starter homes across the country.

The end goal is to incorporate revised manufactured home definition without permanent chassis requirement into must-pass legislation. An alternative is to pass it as standalone legislation.

Conclusion

Based on conversations with HUD staff, it is our understanding that once the permanent chassis requirement is lifted by Congress, HUD and the Manufactured Housing Consensus Committee will need to revise its existing administrative regulations to incorporate off-chassis construction into the existing HUD Code, or it could develop a parallel HUD Code for off-chassis construction.

After the HUD Code revisions are completed, homebuilders will have more design flexibility, and consumers will have more options beyond local site-built home builders for small and starter homes. Increased uptake for manufactured construction following this policy change will come from allowing HUD Code construction to compete more evenly against site-built construction.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

Redirect Federal Housing Tax Expenditures from “Gated” Cities to “Opportunity” Cities

House prices have surged over the past decade, doubling while general prices have only increased by a third. Numerous municipalities help to fuel this housing cost rise by exercising an overly burdensome regulatory process. These restrictions impose severe costs on potential new residents and the national economy – with one estimate that local zoning laws reduced U.S. growth by 36 percent between 1964 and 2009. Preferential tax benefits for housing — including the mortgage interest and property tax deductions and the exclusion of capital gains on home sales – become especially valuable for landowners in restrictive housing markets where prices are high and new construction is low.

To address this challenge, I propose removing housing-related tax expenditures in cities that excessively limit housing production and redirecting them to incentivize housing growth in nearby cities.

The federal government is projected to spend $604 billion over the next five years in tax benefits for homeowners. Under this proposal, the federal government would remove housing tax benefits for all landowners in identified cities that refuse to build housing at a pace necessary to accommodate our growing nation. To maximize benefits from this policy, these tax savings would then be redirected toward residents and governments (through direct payments or tax credits) of cities that build enough new housing for future residents to migrate to these same metro areas.

Recommendations

Specifically, this proposal would remove housing-related tax benefits for all housing units within “gated” cities and redirect those tax savings toward “opportunity” cities.

- These housing-related tax incentives include the mortgage interest and property tax deductions and the capital gains exclusion for home sales.

- Tax expenditures saved by the removal of these incentives would be tallied and distributed to other within-metro opportunity cities.

- These tax benefits would be removed for all housing units in gated cities – both owner-occupied and rented units.

- Gated cities would be identified as cities where home prices are high and housing growth is low.

- Since regulatory burden is difficult to observe directly, gated cities would be identified based on average home prices and housing unit growth observed in the American Community Survey. My proposed definition is cities where median home values are two-thirds greater than the census division median for metro areas and below two-thirds the median housing unit growth rate for metro areas.

- Opportunity cities would be identified as high-growth cities within each gated city’s metro area that build a relatively high share of housing for their urbanicity status.

- My proposed definition is cities with housing growth more than two-thirds above the metro-area growth rate, while also being above census division average housing growth rate for urban areas.

- Because expected housing growth differs by urbanicity status, the growth threshold value could be conditioned based on the National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural classification scheme.

- Tax expenditure savings from gated city exclusions could flow as a mix of refundable tax credits or direct payments to each resident of opportunity cities and direct payments to municipal governments. These payments would help offset the fixed cost to public goods and infrastructure arising from increased housing while creating a broad constituency to promote and advocate for reducing housing supply barriers.

Should this proposal be implemented, there are important considerations to keep in mind:

- This plan provides billions in housing supply incentives without increasing the federal budget a penny. Housing costs a lot. It accounts for 34% of household spending and aggregate home values top $47 trillion. As a result, it becomes very costly very quickly to meaningfully affect housing supply through subsidizing construction. With this carrot-and-stick policy design – and affecting less than 5% of the population with the above proposal — this policy leverages a precisely targeted punishment to directly incentivize more housing growth in high-value areas at no budgetary cost.

- Overcoming minor preferences: While most people favor policies to expand housing supply, small and determined groups of residents can have outsized power in local politics. By providing a modest incentive to increase growth in desirable metro areas combined with a significant financial cost to obstructionist cities, this legislation creates natural constituencies to better achieve the majority sentiment while helping our nation grow.

- Federal tax benefits for homeowners encourage and reward long-term social and community investments of their residents. By refusing to allow adequate housing growth, gated cities turn their back on future generations. This policy respects a city’s right to make this decision but also helps communicate the harm restrictive zoning produces by withdrawing housing tax benefits.

- Existing legislation and precedent: This plan follows a similar design as Opportunity Zones in the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act legislation. Instead of providing tax benefits to distressed areas, however, this legislation would remove tax benefits from gated cities.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

Exclusionary Zoning or Highway Funds, Your Pick: A Viable Mechanism for Federal Action on Zoning

The United States is short 3.8 million units of housing, largely due to artificial limits on housing in high-demand areas driven by outdated zoning and building codes. The mandated underbuilding of US housing in rich coastal cities led to an estimated 36% loss in growth from 1964 to 2009 (newer estimates are smaller but still are significant amounts of lost value). As a result, according to US Housing and Urban Development (HUD) criteria, some 22 million renters qualified as rent-burdened in 2021. We propose that the federal government use highway funding as a legal mechanism to force states to adopt zoning reform. Since the legislative process is slow, we also propose immediate executive action to nudge state and local agencies on minor factors limiting housing supply, including building codes.

Legal precedent for our proposal is 23 U.S.C. §158, which imposed a national minimum drinking age by taking away recalcitrant states’ highway funding. Furthermore, there are ample existing models for federal legislation to take: for example, California’s extensive reforms, including but not limited to allowing by-right construction of Accessory Dwelling Units and preempting San Francisco’s zoning policy, and Montana’s reforms, which require by-right zoning approvals and allowing of up to quadplexes for almost all cities above 5,000 in population. We propose mimicking the New Jersey Mount Laurel doctrine or the California Housing Elements legislation, imposing a requirement for looser regulations on states containing cities with a rent crisis.

Legislative Recommendation

Congress should pass legislation following 23 U.S.C. §158 requiring each state with a Metropolitan Statistical Area where the median renter is rent-burdened (i.e., median rent is at least 30% of area median income) and where area median income exceeds the US median income to submit a plan to HUD detailing how they will address the rent crisis in their state.

- Strategies to submit to HUD may include:

- Requiring every lot allow the construction of four attached units, two attached units, two detached units, or any less dense combination.

- Allowing accessory Dwelling Units to be built without affecting any mandates that apply to the lot.

- Not allowing parking minimums to exceed one space per bedroom for a residential unit.

- Limiting impact fees and other charges cities bring on developers.

- A catch-all clause banning unreasonable burdens on the construction of housing.

- Private right of action similar to California’s builder’s remedy, allowing for a lawsuit to gain by-right approval if the law is violated.

Any state whose proposal is found to not expeditiously move it to a place where the median renter is no longer rent-burdened can lose appropriations from the Highway Trust Fund.

Congress should also appropriate $1 billion to fund planning studies in states affected by this law.

Executive Recommendation

The U.S. Department of Transportation and the Federal Transit Administration should start using allowed population density within a catchment area as a scoring criterion for competitive transit grants.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency should, in its building code modernization project, examine if building code changes can allow for the building of more housing and align with peer countries’ regulations.

- For example, examining whether single stair access designs are safe.

Some might argue that a congressionally driven strategy is too difficult. We disagree, as coalitions for legislative housing reform have been able to form in urban NIMBY and progressive California, rural-Republican dominated Montana, and suburban, new Republican-leaning Florida. We propose fostering an urban-rural coalition by targeting separate messages to each party. Specifically, we would target urban Democrats by focusing on the socioeconomic disparities fostered by exclusionary zoning, and target (rural) Republicans by pointing out that restrictive zoning is an infringement on property rights, and its resultant sprawl threatens the rural character of communities. Some might argue that highway funding and housing are unrelated. However, the federal government has an interest in ensuring its transportation is an efficient use of taxpayer money, and under exclusionary zoning, development is encouraged to unnecessarily sprawl overloading interstate highways, thus forcing expensive highway widenings; essentially, arguing that housing and transportation are inexorably linked.

If our proposed bill is passed, gains on housing affordability will be locked in and restrictions preventing the average American from owning or renting where they want to live will begin to fade, unlocking the potential of the American economy.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

Less Paperwork, More Projects: Streamlining applications for Federal funding in housing development

U.S. housing and planning officials have identified a series of roadblocks that slow down or prevent their cities from being flush with affordable units. In particular, the paperwork is simply too complicated.

Existing federal rules make filing for Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) funds challenging. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) compliance requires one set of paperwork, National Register of Historic Places mandates require another, on top of the paperwork requesting funds. Outside of compliance rules, applications for funding regulations need their own paperwork and require status reports throughout the project.

Opportunity

The programs meant to create housing abundance have instead created a complex network of paperwork that is redundant, rigid, and discouraging. Let’s narrow our lens, and consider how developers use the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) in particular. Developers may pull together as many as 11 sources of funding for a single project, which they are encouraged to do. Many state Qualified Allocation Plans prefer projects that leverage other government funding sources outside of the LIHTC.

But it costs money to make money. According to a 2018 Government Accountability Office report, developer fees were about 10% of the total costs for both new construction and rehabilitation projects. In addition to literal fees, sourcing and applying for diverse funding takes time. A 2021 Terner Center report identified “lack of alignment of deadlines,” multiple application rounds, mismatched priorities (“the city elected to disburse capital funds early in the process to help the project be competitive for state funds, while the housing authority’s approach was to prioritize project “readiness”), and contrasting requirements as massive time sucks that delay critical housing projects.

Plan of Action

Some states already streamline allocation from multiple funding sources to truncate development timelines and contain costs.

In Pennsylvania, a single entity administers multiple programs as a “one-stop shop” – a single application for a nine percent LIHTC automatically marks the applicant for HOME and National Housing Trust Funds, turning three applications into one. The Pennsylvania Housing Affordability and Rehabilitation Enforcement (PHARE) program also consolidates applications: Applying for a four percent LIHTC credit? You are also automatically eligible for other PHARE-distributed funds, like the Realty Transfer Tax and Marcellus Shale Fund. All of the sources that Pennsylvania Housing Finance Authority (PHFA) allocates, it does so in-house and with nearly-identical requirements. Because of this optimization, PHFA can award developers the “optimal mix of funding” in a single application.

Other states consolidate applications to further streamline funding processes. In Minnesota, the state has consolidated multiple housing resources within a single application process. This so-called “Consolidated RFP” has turned $298.9 million of state investment into $883 million in housing development activity, representing over 5,074 affordable units.

If states are able to put these innovations into place, then so should the federal government. The best place to start is HUD. Housing development grants and other affordable housing programs are already centralized at HUD, making it a natural fit for updated practices meant to distribute those programs.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1. Create a federal one-stop shop for affordable housing investments.

In FY23, there were 40 unique HUD funding opportunities, each requiring its own application. About half of these grants are disbursed to individuals seeking assistance for repairs or other programs. The other half, like the Choice Neighborhoods Implementation program or Capital Fund at Risk program, are aimed at communities and developers. In addition to HUD, other agencies earmark or leave open grants and funding opportunities for housing developments. To reduce friction for developers applying to multiple funds, HUD should look to Pennsylvania and Minnesota and create a lean interagency working group to consolidate applications.

This working group would have two goals:

- Enumerate all federal-level housing development grants and funds in a given fiscal year.

- Create a minimum viable universal application.

The first goal would empower HUD to be the keeper of all knowledge regarding housing development grants, which it does not currently do. This makes it easier to capture information about how these disparate grant opportunities are used across the country (something that the Government Accountability Office is extremely interested in). By cataloging developer-level grants, HUD would be a single source of information on Capital Magnet Fund, National Housing Trust Fund, public housing operating funds, and myriad other funding sources.

Recommendation 2. Align requirements and deadlines across grants and funds.

With a minimum application in place, the working group should then align the minimal amount of excess application material required to make an application competitive for the biggest number of grants. This would decrease the burden for developers submitting multiple applications, as well as federal grantmakers reading and grading applications. The working group should consolidate deadlines (or even consider taking applications in limited waves) to accommodate the universal application process.

Recommendation 3. Empower staff to award responsibly.

When more established and active, the working group should empower members to award “optimal mix of funding” to applicants. If an applicant was unaware they qualified for an additional grant, awarding staff should take reasonable action to submit the applicant into the process for the additional grant. With the universal applications, this would require minimal, if any, additional work on behalf of the working group staff or submitters.

Conclusion

Developers, funders, and the bureaucratic teams that sign off and disburse funding — everybody hates paperwork. Opening access to funds does not have to require more person power, as exemplified in the states that use consolidated applications. That access, paired with more streamlined application paperwork, would cut down busy work for developers and get them to what they do best fast: build.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

A National Housing Policy Simulator: A Plan for Modeling Policy Changes to Spur New Housing Supply

By several measures, the United States faces the greatest shortage of housing since World War II. Increasingly stringent local regulatory barriers are often to blame, but we have little way of knowing what specific policies are constraining new housing supply in any given community. Is it overly onerous height limits? Outsized permitting fees? Uncertain approvals? Furthermore, for the federal government to spur local governments to encourage new housing development—e.g., by tying federal transit dollars to local pro-housing actions—it ideally needs to first understand the potential for new housing supply in those communities. In addition, because of the multi-year lag between enacting policies and seeing housing built as a consequence of those changes, modeling which policies will move the dial on production—and by how much—increases the likelihood that policy change will have the intended result. The good news is that the tools, data, and proof of concept all exist today; what is needed now is for the federal government to build, or fund the creation of, a National Housing Policy Simulator. Done right, such a tool would allow users to toggle policy and economic inputs to compare the relative impact of new policies and guide the next generation of land use reform.

Simulators, such as the one built by UC Berkeley’s Terner Center & Labs for the City of Los Angeles, demonstrate the value of connecting zoning data with economic feasibility pro formas for modeling supply impacts. However, successful, validated simulators have been rare and limited to a handful of geographies. With recent efforts to digitize land use data, increased real-time datasets on rents, home prices, financing, and construction costs, combined with remarkable advances in computing power, the federal government could accelerate a scaling of this modeling, bringing forward national adoption within two years.

While this proposal might be seen to compete for federal funding with other housing subsidies, the idea of a national simulator is complementary: first, because it allows for a cost-effective targeting of existing federal pro-housing efforts, and second, because it spotlights low-cost zoning and land use reforms that can result in new unsubsidized housing.

To make this happen, Congress should

- Appropriate $10 million to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Office of Policy Development & Research (PD&R) to build, or fund the creation of, a National Housing Policy Simulator and commission related research.

- Appropriate $500,000 to HUD’s Office of Community Planning & Development (CPD) to update its existing data collection tools and provide technical assistance.

Once funded, HUD should

- Build and/or contract with one or more academic/research organizations to scale the necessary mapping and economic modeling tools and acquire necessary financial datasets (e.g., county assessor data, home price information, construction cost estimates, vacancy rates, census data, capitalization rates, and costs of financing) (via PD&R).

- Amend its Consolidated Annual Performance and Evaluation Report, which is required of all jurisdictions that receive federal housing block grant funding, to report annually on land use and zoning changes in order to complete to build out and ensure the ongoing maintenance of the existing National Zoning Atlas or a similar federally maintained resource (via CPD).

Once built, Congress should

- Direct all federal agencies to look for opportunities to integrate this modeling data and tool into federal pro-housing policies and program development as well as to enable its use by local governments, researchers, advocates, and policymakers.

- Prioritize and commit to funding ongoing reporting and research opportunities.

A National Housing Policy Simulator can unlock an entirely new field of research and drive the next generation of policy innovation. Equally importantly, it will allow a deeper understanding of the policy incentives, levers, regulatory policies, and financial programs that can precisely target incentives and penalties to stimulate housing supply, while also empowering local actors—such as civic leaders, elected officials, and local planners—to effectuate local policy changes that make meaningful improvements to housing supply.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

Building internal staff capacity would help HUD support pro-housing policies

The United States is experiencing a persistent and widespread housing shortage. Over the past several decades, housing supply has become less responsive to changes in demand: growth in population and jobs does not lead to proportional growth in the number of homes, while prices and rents have increased faster than household incomes. While state and local governments have primary responsibility for regulating housing production, the federal government could more effectively support state and local pro-housing policy innovations that are currently underway.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) should designate or hire at least one career staff member to work on housing supply and land use as their primary responsibility.

Because housing supply and land use have not been part of HUD’s historic portfolio of funded programs, the agency has not invested in building consistent staff capacity on these topics. Designated staff should have substantial expertise on the topic, either through direct work experience or research on land use policy, and enough seniority within HUD to be listened to. The Biden Administration has made a good start by appointing a Special Policy Advisor working on housing supply. Integrating this position into a career staff role would help ensure continuity across administrations. The most appropriate division of HUD would be either Policy Development and Research, which is research-focused, or Community Planning and Development, which provides technical assistance to communities.

HUD’s housing supply staff should oversee two primary efforts within the agency: supporting the efforts of state and local policymakers and other stakeholders that are experimenting with pro-housing policies, and disseminating clear, accessible, evidence-based information on the types of policies that support housing production. These roles fall well within HUD’s mission, do not require congressional authorization, and would require relatively modest financial investments (primarily staff time and direct costs of convenings).

First, to support more effective federal engagement, HUD’s housing supply lead should develop and maintain relationships with the extensive network of stakeholders across the country who are already working to understand and increase housing production. Examples of stakeholders include staff in state, regional, and local housing/planning agencies; universities and research organizations; as well as nonprofit and for-profit housing developers. Because of the decentralized nature of land use regulation, there is not an established venue or network for policymakers to connect with their peers. HUD could organize periodic convenings among policymakers and researchers to share their experiences on how policy changes are working in real time and identify knowledge gaps that are most important for policy design and implementation.

Second, HUD should assemble and disseminate clear, accessible guidelines on the types of policies that support housing production. Many local and state policymakers are seeking information and advice on how to design policies that are effective in their local or regional housing markets and how to achieve specific policy goals. Developing and sharing information on best practices as well as “poison pills”—based on research and evaluation—would reduce knowledge gaps, especially for smaller communities with limited staff capacity. Local governments and regional planning agencies would also benefit from federally funded technical assistance when they choose to rewrite their regulations.

Across the country, an increasing number of cities and states are experimenting with changes to zoning and related regulations intended to increase housing supply and create more diverse housing options, especially in high-opportunity communities. Through targeted investment in HUD’s staff capacity, the federal government can better support those efforts by facilitating conversations between stakeholders and sharing information about what policy changes are most effective.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

Unblock Mass Timber by Incentivizing Up-to-date Building Codes

Mass timber can help solve the housing shortage, yet the building material is not widely adopted because old building codes treat it like traditional lumber. The 2021 International Building Code (IBC) addressed this issue, significantly updating mass timber allowances such as increasing height limits. But mass timber use is still broadly limited because state and local building codes usually don’t update automatically. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) could speed the adoption of mass timber through grants that incentivize state and local governments to adopt the latest IBC codes.

Mass timber can help with housing abundance and the climate transition.

Compared to concrete and steel, mass timber buildings are faster to build (therefore often cheaper), just as safe in fires, and create fewer CO2 emissions. Single- and multi-family housing using mass timber components could help with the 7.3 million gap of affordable homes.

Broader adoption could meaningfully increase productivity and thereby reduce construction costs. Constructing the superstructure for a 25-story mass timber building in Milwaukee completed in 2022 took about half as long compared to concrete. Developers have reported cost savings of up to 35% through lower time and labor costs. Mass timber isn’t only for small projects: Walmart is building a new 2.4-million-square-foot office campus from mass timber.

Most states are on older building codes that inhibit use of mass timber.

Use of mass timber is growing. But building codes, often slow to catch up with the latest research, have limited the impact so far. Only in 2021 did amendments to the IBC enable the construction of mass timber buildings taller than six stories Building taller increases the cost savings from building faster.

State and local government adoption of building codes lags further. By 2023, only 20 states had adopted IBC 2021. Eventually builders might lobby governments to catch up, but for now there’s little reason for many builders to consider mass timber when it’s so restricted.

USDA could incentivize the adoption of the latest IBC.

There should be a federal grantmaking program that implicitly requires the latest IBC codes to participate, incentivizing state and local government adoption.

The USDA could house this program due to policy interest in both the timber industry (Forest Service, FS) and housing (Rural Development, RD).

In fact, USDA is already making grants towards mass-timber housing, just not at a scale that directly incentivizes code changes. Since 2015, the Wood Innovations Grant Program has invested more than $93 million in projects that support the wood products economy, including multifamily buildings. USDA also recently partnered with the Softwood Lumber Board to competitively award more than $4 million to 11 mass timber projects. Most of these buildings are in states or cities that have adopted IBC 2021. For example, one winner is a 12-story multifamily building in Denver, which would be impossible without IBC 2021.

To unlock the adoption of innovative mass timber construction, Congress should take the following steps:

- Appropriate additional discretionary budget to USDA with direction to invest in mass timber innovation. For example, increasing the Wood Innovations Grant Program by 10 times the FY 2023 amount would be ~$430 million, less than 1.5% of USDA’s discretionary budget.

USDA should then take the following steps:

- Allocate those funds to the FS Wood Innovations Grant Program or a similar program within RD.

- Prioritize grants to multi- and single- family housing projects.

- Write funding priority that necessitates the latest IBC mass timber amendments. For example, priority to building designs over eight stories would only be possible in locations where IBC 2021 is in effect (or comparable amendments).

That funding opportunity incentivizes state and local governments to adopt mass timber amendments.

It’s uncertain how much funding would create a strong incentive. But even if most projects were awarded in states already using IBC 2021, there may still be positive downstream impacts from meaningful investment in the industry. While there are far fewer mass timber projects relative to total construction, there are far more than a grant program of this scale could directly support, so there shouldn’t be a shortage of projects. The goal is not to directly build millions of homes but to bring state building codes up-to-date. Updating building codes is necessary but not sufficient for construction at scale.

A simple mechanism to unlock the potential of mass timber.

A federal USDA grant program incentivizing adoption of the latest IBC amendments related to mass timber requires no new funding mechanisms and no new legislation. The structure is already available with the FS Wood Innovations Grant Program as a clear example. That program had ~$43 million in grants for FY 2023; perhaps an order of magnitude more funding would move more states to the updated IBC. This program would not drive mass timber adoption at scale on its own, but updating building codes is a necessary first step. Because mass timber is faster to build with and results in fewer emissions, it is a crucial building material that could contribute to both housing abundance and the climate transition.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

Incentivizing Developers To Reuse Low Income Housing Tax Credits

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program has been the backbone of new affordable housing construction nationwide for the last 37 years. Developers who receive LIHTC financing are paid twice: they collect a developer fee, and they own the building. They can raise rents to market rate after affordability periods expire. States are unable to leverage any capital gain in the project to develop more housing in the future because those gains have disappeared into the developer’s pockets.

Existing LIHTC incentives for nonprofits do not ensure that profits are recycled to build more housing, because many nonprofits have other, nonhousing missions. For example, the proceeds of the 2007 sale of one large, nonprofit-owned housing project built in the 1960s in Hawaii were donated to schools and hospitals. Those funds were generated from housing subsidies and could have created hundreds of new affordable homes, but they left the housing sector permanently.

Incentivizing organizations to use their profits to build more housing will enable LIHTC to create much more housing in the long term. My proposal would amend 26 U.S. Code §42(m)(1)(B)(ii) to ensure each state’s Qualified Allocation Plan gives preference to applicants that are required to use the profits from their development to construct more below-market housing. States and local governments will also receive preference, as they are mission-driven institutions with no incentive to raise rents to market in the future.

This proposal is based on the Vienna, Austria, housing model. Vienna spends no new taxpayer dollars on housing construction, yet houses 60 percent of its population—all who want it—in well-designed, mixed-income social housing. To produce new social housing, Vienna extends low-interest loans to Limited Profit Housing Associations (LPHAs), corporations that make profits but are required to use them to develop more housing in the future. LPHAs charge tenants an approximately $56,000 buy-in upfront, plus rent. Together, these revenue streams cover the cost of servicing the low-interest loans, enabling each building to be revenue positive, especially after the loan is repaid, and thus allowing the LPHA to build more housing in the future, creating a virtuous, self-sustaining cycle of housing creation.

In lieu of creating a separate, regulated category of business association, the LIHTC program can prioritize entities required to use their profits to construct more housing, such as through restrictions in their organizational documents.

Recommendation

Congress should

- Amend 26 U.S. Code §42(m)(1)(B)(ii) to include in its preferences “(iv) entities obligated to use the profits from their development to construct more below market housing” and;

- Amend 26 U.S. Code §42(m)(1)(C) to include in its selection criteria “(xi) projects that are state- or county owned, in which the state or county is an equity partner, or in which ownership is conveyed to the state or county at a definite time.”

Because states and counties have no incentive to raise rents to market or to pocket the profits from selling such housing, they would also be better recipients of taxpayer financing than for-profit developers.

Political resistance to this concept has come from two main sources. First, state housing finance agencies (HFAs) that administer LIHTC are reluctant to change processes that have been in place for decades. LIHTC currently allows states wide latitude in how to select developers, and HFAs will resist federal restrictions on that flexibility. Second, current LIHTC developers are reluctant to give up any compensation source, even those many years in the future. These arguments have become less persuasive as LIHTC applications have become much more competitive in recent years. If applicants are unwilling to build LIHTC projects without ownership, they will simply forgo those points in the application, and the current system will continue. But if there are applicants willing to use the new structure, as we have anecdotally heard here in Hawaii would be numerous, they will prove the counterarguments wrong.

Persuading Congress to adopt these changes may be challenging. Indeed, private developers successfully lobbied Congress to eliminate support for nonprofit and limited profit cooperatives as early as the Housing Act of 1937. Despite many criticisms over the years, LIHTC is one of the few affordable housing programs with bipartisan support, because it both rewards private sector developers and produces housing for the low income. Yet despite the billions that Congress appropriates year after year, America’s housing shortage has gotten worse and worse. If LIHTC funds created projects that recycled their profits into building more housing, LIHTC would create a virtuous cycle to build more and more housing, moving the needle without additional expenditure of taxpayer funds.

A potential source of support would be the mission-driven nonprofit organizations that would be the beneficiaries of this policy change. As part of their LIHTC applications, they would be very willing to create entities legally required to recycle their profits. They would also likely partner with existing LIHTC developers, who could be paid a fee, to deliver the projects. Existing developers would still be able to profit from producing LIHTC housing, even though they would forgo ownership of the building.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

Expand the Fair Housing Initiatives Program to Enforce Federal and State Housing Supply and Affordability Laws

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) forthcoming Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) final rule and a recent wave of state housing affordability legislation create mechanisms to substantially increase the nation’s affordable housing supply. However, because local noncompliance with these laws poses a crucial obstacle, successful implementation will require robust enforcement. To ensure local governments’ full compliance with AFFH and state housing affordability legislation, Congress and HUD should expand the Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP) to fund external enforcement organizations.

FHIP is a model for enforcement of complementary federal and state housing laws. A “necessary component” of fair housing enforcement, FHIP funds local nonprofit organizations to investigate and raise legal complaints of discrimination in their communities under the Fair Housing Act. FHIP grantees play a “vital role” in Fair Housing Act enforcement because FHIP-initiated civil actions and complaints to enforcement agencies are more likely to be properly filed and successfully resolved.

FHIP should be expanded to enforce a new generation of federal and state laws that promote housing supply and affordability but are at risk of insufficient enforcement. AFFH will require localities to implement equity plans that reduce residential segregation and increase access to affordable housing in high opportunity areas. HUD is empowered to withhold substantial streams of federal funding from noncompliant jurisdictions. Nonetheless, HUD poorly enforced AFFH’s previous iterations, leading to calls for “external, relatively independent” enforcement mechanisms. At the state level, a raft of recent legislation overrides local exclusionary zoning and streamlines local housing development permitting processes. However, many localities have demonstrated fierce resistance to these state laws with efforts designed to avoid compliance, including constitutional challenges, declarations of entire towns as “mountain lion sanctuar[ies],” and proposals to give up public infrastructure. Understaffed state agencies may be strained to strictly enforce such laws against hundreds of statewide localities.

As independent community institutions with extensive legal expertise in the housing field, FHIP grantees are well situated to tailor innovative enforcement of the emerging housing supply and affordability regime to their communities. Grantees could build on their administrative expertise by filing complaints to HUD under §5.170 of the proposed AFFH rule. In addition, grantees could initiate civil actions under state laws and the federal False Claims and Fair Housing Acts against jurisdictions that shirk their housing obligations. Grantees might also use their expertise to educate local policymakers and stakeholders on their responsibilities under emerging laws.

Congress should:

- Amend the Fair Housing Initiatives Program’s authorizing statute (42 U.S.C. 3616a) to permit the allocation of grants to fair housing enforcement organizations for enforcement of relevant state and local housing supply and affordability laws, as determined by HUD.

HUD should:

- Amend the Fair Housing Initiatives Program regulations (24 C.F.R. 125) to add a new Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Enforcement Initiative (AFFH-EI). The initiative would fund fair housing enforcement organizations to enforce localities’ obligations under AFFH.

- Promulgate administrative guidance and administer technical assistance to AFFH-EI grantees to specify how funds should be used. Grantees should investigate local compliance with AFFH, raise administrative complaints of noncompliance, and pursue affirmative litigation against noncompliant jurisdictions under the Fair Housing Act, False Claims Act, and other relevant federal and state statutes.

If successfully implemented, an expanded FHIP would support the full enforcement of the forthcoming AFFH final rule and recent state housing supply and affordability legislation by bringing administrative complaints to HUD and state agencies, initiating civil enforcement actions, and educating local stakeholders. Indeed, these FHIP grantees would hold local governments accountable to their duties to equitably plan for, and remove legal barriers to, the development of affordable housing in high opportunity areas for all.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

How A Defunct Policy Is Still Impacting 11 Million People 90 Years Later

Have you ever noticed a lack of tree cover in certain areas of a city? Have you ever visited a city and been advised to avoid certain districts or communities? Perhaps you even recall these visual shifts occurring immediately after crossing a particular road or highway?

If so, what you experienced was likely by design:

In the early 20th century, Black communities across the U.S. were subjected to economic constraint and social isolation through housing policies that mandated segregation. Black communities were systematically excluded from the housing benefits offered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). The HOLC served as the basis of the National Housing Act of 1934, which ratified the Federal Housing Authority (FHA).

Housing policy discrimination was further exacerbated by the FHA refusing to insure mortgages near and within Black neighborhoods. The HOLC provided lenders with maps that circled areas with sizeable black populations with red markers—a practice now referred to as redlining. While the systematic practice of redlining ended in 1968 under The Fair Housing Act of 1968, redlining continues to economically impair over 11 million Americans—and less than half are Black.

You are probably thinking (1) how is this possible? (2) How could a defunct 20th-century policy designed to discriminate against Black communities still impact over 11 million—mostly non-Black—Americans today? The answer is the same for both questions: place-based discrimination.

Policies such as redlining are designed to worsen the material conditions of a target group by preventing investment in the places where they live. Over time, this results in physical locations that are systemically denied access to features such as loans, enterprise, and ecosystem services simply due to their location or place. Place-based discrimination is the principal mechanism of redlining effects, and consequently, costs taxpayers millions of dollars per year.

What is the problem?

Starting in the 1990s, during the Clinton Administration, billions of dollars in tax credits were devoted towards community development and economic growth through the use of special tax credits that attract private investments (Table 1). One of the principal agents from this funding to address place-based discrimination was the creation of Community Development Entities (CDEs). According to the New Markets Tax Credit Coalition, CDEs are private entities that have “demonstrated” an interest in serving or providing capital to low-income- communities (LICs) and individuals (LIIs). Once certified, CDEs are eligible to apply for a special tax credit, New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC), through the Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) Fund.

However, this program, and others like it, have had a negligible impact on addressing the systemic implications of redlining . A recent Urban Institute report found that inequity in capital flow and investment trends within cities (i.e., Chicago) is driven by residential lending patterns. Highlighting the inequalities that exist between investment among neighborhoods with different racial and income demographics, the analysts surmise that redressing economic downturn involves expanding investments into divested neighborhoods. To date, more than $71 billion have been awarded to CDE’s, and yet, historically-redlined areas remain economically desolate. If these programs are intended to economically revitalize historically-redlined areas, then these programs are not doing what they are supposed to do.

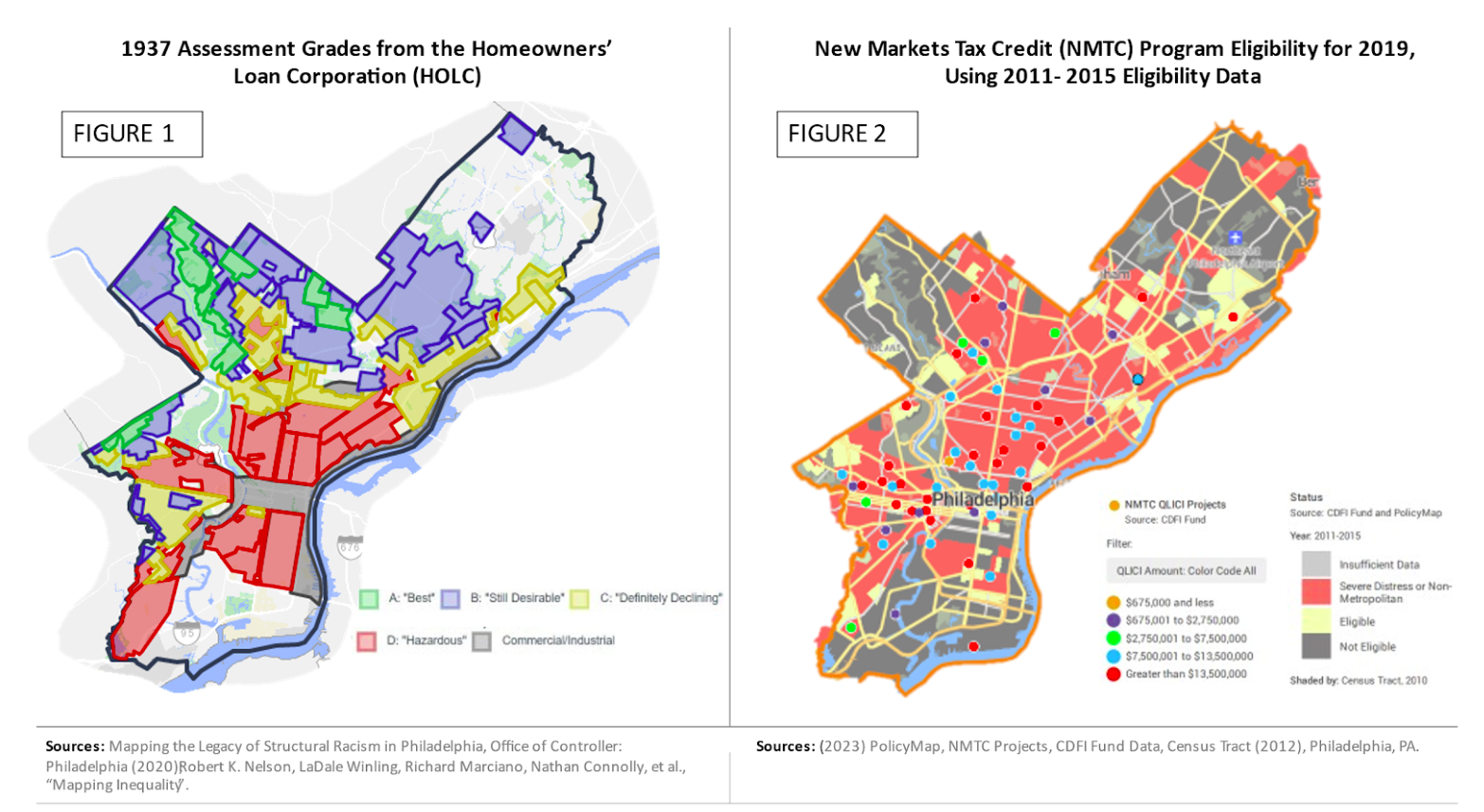

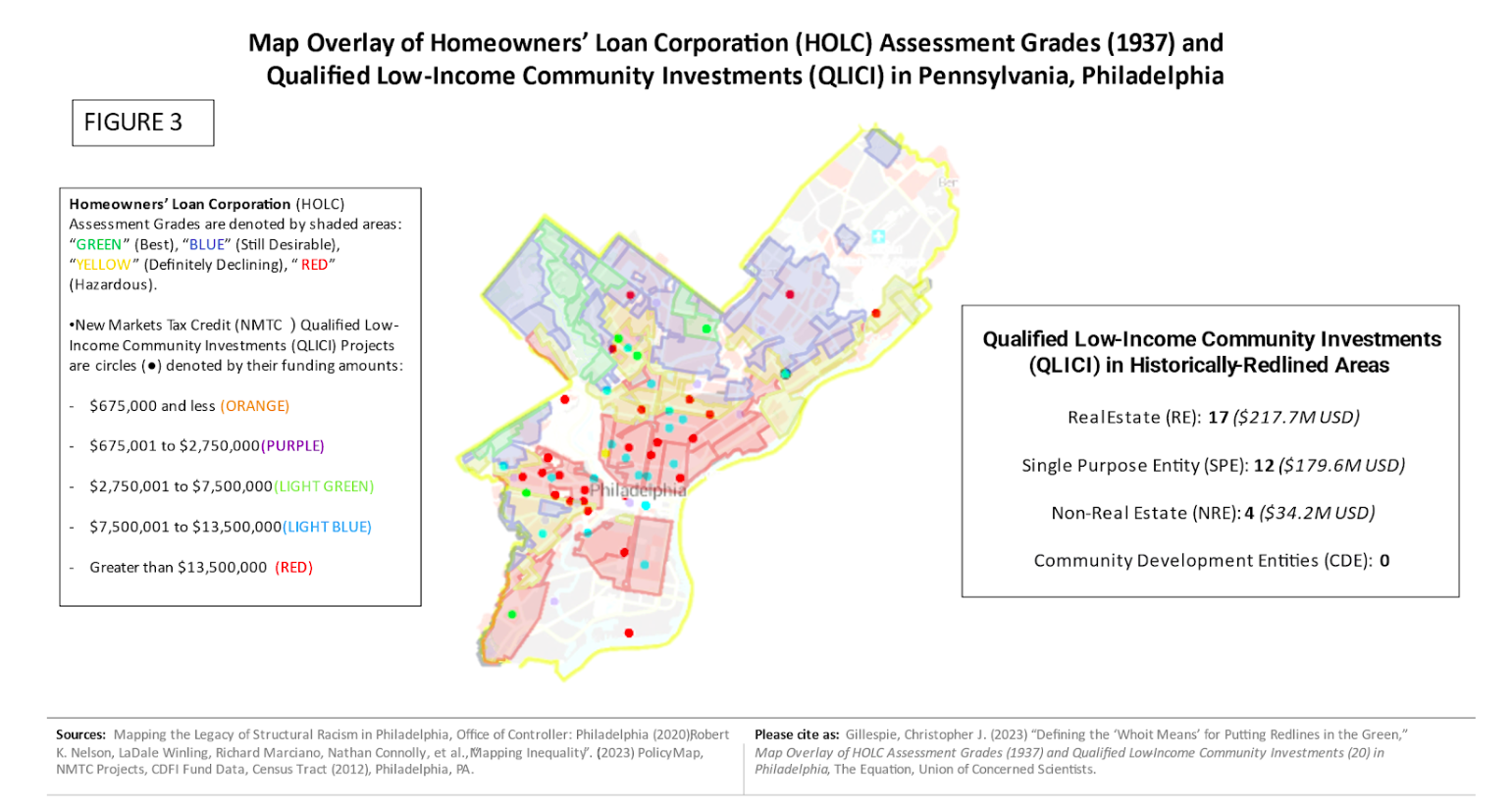

One example of this is the city of Philadelphia:

Philadelphia, a city in the top ten for redlined populations, possesses tens of thousands of vacant buildings and lots that are overlaid by redlining and riddled with brownfield sites. According to the Philadelphia Office of the Controller, historically redlined communities of Philadelphia continue to experience disproportionate amounts of poverty, poor health outcomes, limited educational attainment, unemployment, and violent crime compared to non-redlined areas in the city.

By analyzing HOLC assessment grades (1937) and New Market Tax Credit (NMTC) Program Eligibility (i.e., PolicyMap, projects from 2015-2019) for Philadelphia, PA, I found that of the 30+ Qualified Low-Income Community Investments (QLICIs) in historically-redlined areas, totaling over $400 million in tax credits, none are categorized as Community Development Entities (CDEs).

HOLC assessment grades (1937) vs. New Market Tax Credit (NMTC) Program Eligibility

Of the 30+ Qualified Low-Income Community Investments (QLICIs) in historically-redlined areas, totaling over $400 million in tax credits, none are categorized as Community Development Entities (CDEs).

Meanwhile, the Philadelphia City Council just passed a budget that allocates a record $788 million to the Philadelphia Police Department (PPD). Recent studies show that fatal encounters with police are more likely to occur within historically-redlined areas. It appears the nicest buildings in redlined areas may very well be police stations.

Yet, public investment has been more concerned with maintaining systems of oppression than reversing them. Why continue to invest in systems that do not create wealth? No matter your perception of American policing, the following is clear: policing does not create wealth for distressed communities.

Currently, there are 200+ cities and thousands of communities that are, like Philadelphia, enduring the systemic implications of redlining.

What would happen if public investments were allocated towards restorative policy actions within historically-redlined areas?

A federal program that amalgamates the best elements of community-driven inventiveness into a vehicle for innovative and sustainable economic development. That is, a program that promotes economic revitalization of historically-redlined communities through multipurpose, community-owned enterprises called Innovative Neighborhood Markets (INMs).

What is the policy action?

One thing that urban policy initiatives have made clear, is that distressed communities are prime real-estate targets for private developers . A new federal effort could ensure that investment opportunities are also accessible to community members seeking to launch place-based businesses and enterprises. Businesses and enterprises of this sort will not only reduce urban blight in historically-redlined communities, but also serve as avenues for the direct state, local, and private investment needed to address historical inequities.

The Biden-Harris Administration can combat redlining through a placed-based community investment program, coined Putting Redlines in the Green: Economic Revitalization Through Innovative Neighborhood Markets (PRITG), that affords historically-redlined communities the ability to establish their own profitable enterprise before outside parties (i.e., private developers).

These Innovative Neighborhood Markets (INMs) would be resource hubs that provide affordable grocery items (i.e., fresh produce, meats, dairy, etc.); an outlet for residents of the community to market goods and services (i.e., small businesses); and create cross-sector initiatives that build community enterprise and increase greenspace (i.e., Farm to Neighborhood Model [F2NM], parks, gardens, and tree cover). Most importantly, INM’s are community owned. Through community governance, the community elects and authorizes the types of place-based businesses and enterprises that are present within their INM.

Do you remember the Philadelphia example from earlier?

Under PTRIG, a number of those underutilized structures or vacant spaces are transformed into a vested, profitable, and sustainable community resource. The majority of the financial capital remains within the community, and economic gains are partially earmarked for community revitalization (i.e., soil remediation for brownfield sites, community restoration, and construction of greenspace).

All Taxpayers Benefit

By legally and financially empowering communities with ownership, PRITG will incentivize investment and development that can actually reduce taxpayer liability. For example, the INM can generate the funding to invest in more attractive (and expensive) treecover and landscaping that will reduce the impact of heat islands and imperviousness related to redlining, thereby reducing taxpayer liability by more than $308 million dollars per year. Implementation of PTRIG will decrease taxpayer burden through profit-driven and self-supporting community services.

“Fair and Equal” Access

Another beneficial aspect of this policy involves increasing community access to financial provisions without third-party obstacles (i.e., CDEs and CDFIs). Black and Hispanic home loan applicants are charged higher interest rates than White home loan applicants, resulting in Black and Hispanic borrowers paying $765 million in additional interest per year. Discriminatory practices only succeed in worsening community divestment and increasing the resident displacement which disproportionately impact minority residents. Through the economic-agency provided by PRITG, historically-redlined communities would have heightened protection against lending discrimination, gentrification, and displacement.

Moreover, PTRIG would reinforce the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)’s Combating Redlining Initiative in ensuring that formerly redlined neighborhoods receive “fair and equal access” to the lending opportunities that are—and always have been—available to non-redlined, and majority-White, neighborhoods.

While INMs possess aspects of grocery stores, community banks, business improvement districts (BIDs), and farmers markets, they would differ in one particular area: community wealth.

What is Community Wealth?

As someone who grew up in Champaign, Illinois (Douglas Park), and whose family currently lives in a historically-redlined community (Lansing, MI), it brings me peace to reimagine my community with an INM.

Until my early 20’s, I spent most of my life largely unaware of the importance of community wealth on individual empowerment and its impact on the maintenance of cultural identity. For me, reimagining my community with an INM is not just about correcting the past, it is about enriching the uniqueness of what makes our home, Home.

In general, a community wealth building process needs to address the lack of an asset in a way that builds community sustainability. That is the materialization of a communal epicenter(s) that produces a sense of ownership and pride.

So how would INMs build community wealth? Simple. The community, as a whole, would be defined as the ownership group. Each community member would be legally referenced as a shareholder of this newly acquired, financially-appreciating, community-owned enterprise.

Community Ownership Key to Community Wealth

According to Evan Absher, Chief Executive Officer at Folks Capital, there are currently two broad ways of understanding community ownership.

The first type involves community ownership in the form of trusts or fiduciary arrangements between a community entity and an independent financial establishment. This structure creates a community entity that holds the financial wealth and is subject to some form of community governance. This structure includes entities such as Community Investment Trusts, Community Land Trusts, and Mixed-Income Neighborhood Trust. These structures ensure permanent and lasting control of the land and fidelity to charitable purposes. However, these entities often do not increase actual ownership or produce meaningful wealth at the individual or family levels. Further, they are often nonprofits and can struggle with attracting capital and sustainability.

The second type of community ownership is specifically targeted at individuals and families. These are models that focus on financial agency and ownership of land and property by people within communities. This concept includes models such as employee-ownership, Co-operatives, ROC-USA’s model, and Folks Capital’s Neighborhood Equity Model. These models have an advantage in wealth building and agency for the families involved. The benefit of this second concept of community ownership is that community members have the autonomy to (1) choose to sell their ownership share back to the community fund; (2) receive pro rata (dividend) payments; and/or (3) if the community chooses, sell the enterprise to “would-be gentrifiers.”

Regardless, the community receives more empowerment than was ever offered by previous economic revitalization models (i.e., Opportunity Zones) [See Table 1]. However these models sometimes lack the permanence or control of the other models. If not structured thoughtfully, this lack of control poses a risk of further gentrification.

Regardless of the approach, all models should seek first to center communities and people in the governance and benefits of the model. Institutionalizing models is not the objective. Closing the wealth gap and ending disparities in economic, health, and education outcomes are the ultimate goal.

However, an important question is raised by this policy: who counts as community—especially when talking about the ownership of an individual building?

Are multiple communities expected to be consolidated into one community for the sake of ease? Would that be fair to those communities?

The challenge is making ownership meaningful. Understandably, a resident may possess more pride if their stake in an INM is $1000 opposed to 20 cents.

Thus, communities that are smaller in size may be most benefited by the establishment of an INM. This is not to say that large historically-redlined areas do not stand to gain from INM establishment. Quite the contrary. INMs are designed to not only enfranchise the local communities , but also revitalize the place through restorative, economic, and environmental justice.

Nevertheless, if PTRIG is to provide communities with tools that guarantee full community empowerment, then factors of community ownership should be considered.

Now, one final question remains, and it can only be answered by those within historically-redlined communities: “Who is your community?”

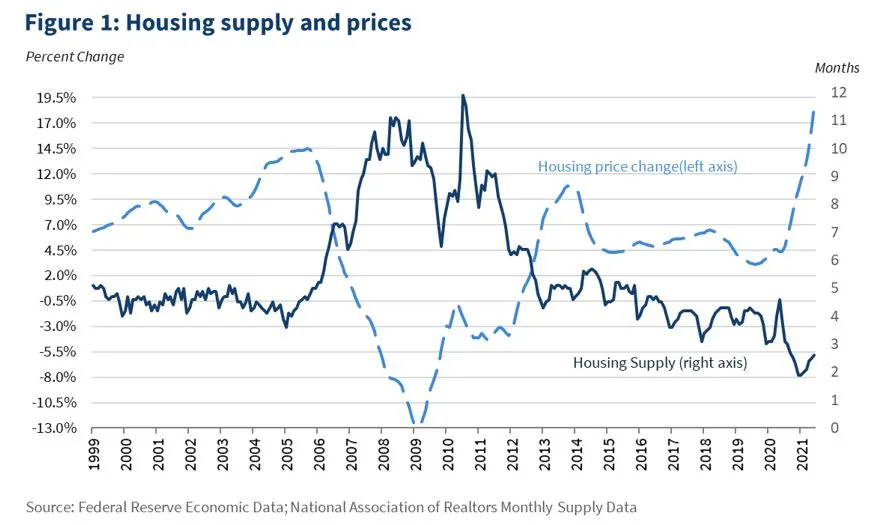

We need to address the housing supply crisis

Housing costs have ballooned, far outpacing the broader cost of living in the U.S. Renters devote more and more of their already limited budget to housing costs and home ownership feels out of reach for many Americans. One key reason for this is the dwindling housing supply across the US.

Addressing the housing crisis is a bipartisan issue. Officials at all levels of government want to ensure that the communities and families they represent have a chance to feel secure in their own home and future. FAS launched our housing policy challenge to uplift ideas that can tackle the crisis and boost housing supply across the country.

The causes of the housing supply crisis are many. Local regulations against density are the main barrier, but there are a host of other important factors. To list a few:

- the difficulties of constructing and organizing public transit systems,

- incentive misalignment for project developers,

- a scarcity of available land in urban areas,

- underfunding of public housing resources,

- lack of access to financing options,

- supply being snatched up by large institutional investors,

- a lack of support for novel arrangements like ADUs and manufactured homes,

- the persistent effects of redlining, and many more.

These challenges to home supply are some of the areas where creative policy thinking could have a meaningful impact. We think the federal government is poised to do more on this issue, and that bipartisan agreement is possible across a range of housing policies. We’re turning to YOU—experts, non-experts, home owners, renters, and neighbors to crowdsource ideas for boosting housing supply.

Creative thinking to boost housing supply

We highlighted the main areas we’re interested in for this challenge but ultimately we’re relying on you to get creative. If you think a given overlooked policy lever could have an impact on housing supply we want to hear about it.

Here are some areas we are excited and motivated by, and there’s always more to discuss.

Construction Innovation

Construction innovation has gotten more attention in recent years. While such innovation only matters if you can build more housing in the first place, construction efficiencies will only grow in importance. Brian Potter of the Institute for Progress writes about the overlooked roles of modular housing, the rise and fall of the mail order home, and building components. Novel ideas on how best to alter restrictive building codes will also be important. The Center for Building in North America has been doing much original work on this subject.

The limited rise of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) is promising, but it seems like more remains to be done to promote familiarity with the opportunity they provide. Are there ways to incentivize folks across urban areas to take advantage of ADUs?

Financing Innovation

Federal financing is another area where creative arrangements, properly designed and communicated, could massively help everyday people. The White House already sought to make Construction to Permanent loans more widely available. Efforts to reform the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) and improve the housing enterprises’ ‘Duty to Serve’ underserved mortgage markets are underway. What other financing needs can be met at the federal level?

Public Land Innovation

The scarcity of available land, especially in urban areas, seems like an insurmountable barrier. However, a closer accounting of public lands and facilities can reveal opportunities and assets that cities may not have realized they could take advantage of to do things like build housing or transit. The Putting Assets to Work initiative is helping cities better account for the value of their physical assets. How can we incentivize locales to assess and use their assets most efficiently?

Effective Measurement

What gets measured gets done. Ways to improve or introduce new federal data resources to measure the housing crisis are critical. There’s a wide range of datasets available from FHFA, Census Bureau, the Federal Reserve, HUD, and more agencies. Organizations like the National Low-Income Housing Center also provide key information . But are there key things like home loss rate that we’re not fully tracking?

Finally, what incentives to boost home supply are we not thinking about in any form right now? We are not looking for the federal government to get directly involved in local zoning issues; instead we want to hear about other productive paths you can help us identify to increase the national housing supply.

To submit an idea, head over to our challenge page.

Smarter Zoning for Fair Housing

Summary

Exclusionary zoning is damaging equity and inhibiting growth and opportunity in many parts of America. Though the Supreme Court struck down expressly racial zoning in 1917, many local governments persist with zoning that discriminates against low-wage families — including many families of color.1 Research shows that has connected such zoning to racial segregation, creating greater disparities in measurable outcomes.2

By contrast, real-world examples show that flexible zoning rules — rules that, for instance, that allow small groups to opt into higher housing density while bypassing veto players, or that permit some small areas to opt out of proposed zoning reforms — can promote housing fairness, supply, and sustainability. Yet bureaucratic and knowledge barriers inhibit broad implementation of such practices. To facilitate zoning reform, the Department of Housing and Urban Development should (i) draft model smarter zoning codes, (ii) fund efforts to evaluate the impact of smarter zoning practices, (iii) support smarter zoning pilot programs at the state and local levels, and (iv) coordinate with other federal programs and agencies on a whole-of-government approach to promote smarter zoning.

Challenge and Opportunity

Economists across the political spectrum agree that restrictive zoning laws banning inclusive, climate-friendly, multi-family housing have made housing less affordable, increased racial segregation and damaged the environment. Better zoning would enable fairer housing outcomes and boost growth across America.

The Biden-Harris administration is actively working to eliminate exclusionary zoning in order to advance the administration’s priorities of racial justice, respect for working-class people, and national unity. But in many states with unaffordable housing, local politics have made zoning reform painfully slow and/or precarious. In California, for instance, zoning-reform activists have garnered significant victories. But a recently launched petition to limit state power over zoning might undo some of the progress made so far. There is an urgent need for strategies to overcome political gridlock limiting or inhibiting zoning reform at the state and local levels.

Fortunately, a suite of new smarter zoning techniques can achieve needed reforms while alleviating political concerns. Consider Houston, TX, which faced resistance in reducing suburban minimum lot sizes to allow more housing. To overcome political obstacles, the city gave individual streets and blocks the option to opt out of the proposed reform. That simple technique reduced resistance and allowed the zoning measure to pass. The powerful incentives from increased land value meant that although opt outs reached nearly 50% in one neighborhood, they were rare in many others.3 The American Planning Association similarly published a proposal to allow opt-ins for upzoning at a street-by-street level — a practice that would allow small groups to bypassing those who currently block reform in order capture the huge incentives of upzoning.

In fact, opt-ins and opt-outs are proven methods of overcoming political obstacles in other policy fields, including parking reform and “play streets” in urban policy. Opt-ins and opt-outs reduce officials’ and politicians’ concerns that a vocal and unrepresentative group will blame them for reforms. While reformers may fear that allowing exemptions may weaken zoning reforms, the enormous increase in land value created by upzoning in unaffordable areas provides powerful incentives for small groups of homeowners to choose upzoning of their own lots. And by offering a pathway to circumvent opposition, flexible smarter zoning reforms can expedite construction of abundant new affordable housing that substantially improves equity, opportunity, and quality of life for working-class Americans.

Absent action by HUD to encourage trials of innovative techniques, the pace of reform will continue to be much slower than it needs to be. Campaigners at state and local government level will continue to face opposition and setbacks. The pace of growth and innovation will be damaged, as bad zoning continues to block the benefits of mobility and opportunity. And disadvantaged minorities will continue to suffer the most from unjust and exclusionary zoning rules.xc

Plan of Action

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) should take the following steps to facilitate zoning reform in the United States:

1. Create a model Smarter Zoning Code

HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research, working with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Office of Community Revitalization, should produce a model Smarter Zoning Code that state and local governments can adopt and adapt. The Smarter Zoning Code would provide a variety of options for state and local governments to minimize backlash against zoning reforms by reducing effects on other streets or blocks. Options could include:4

- Allowing a street or block to opt-in to upzoning by filing a verified petition signed by a qualified majority of the registered voters residing on that street or block.

- If the petition is filed by the residents of a block of houses surrounded by streets, development pursuant to the upzoning should be required to leave untouched the fronts of the houses facing those streets (to minimize impact on residents whose lots are not included in the upzoning).

- Residents can be given the option to attach a design code to their petition.

- Anti-displacement rules. Although most development through smarter zoning will likely happen in neighborhoods dominated by owner-occupied single-family homes, all resident renters should be protected by rules that preserve existing anti-eviction and rent-control provisions. Rules should additionally ensure that no development pursuant to smarter zoning can proceed unless renters are protected, and should include provisions to prevent evasion by landlords.5

- Height restrictions and angled light planes to protect sunlight to other blocks.

- Setback rules that can be waived by adjacent homeowners to allow development of townhouses or multifamily units.

- Compensation payable by a developer to adjoining residents who are adversely affected by development permitted under zoning reform.

- Establishment of controlled parking districts surrounding a street or block that votes to upzone, with free parking stickers issued to residents of adjoining streets to protect their parking access.

- Impact fees, tax increment local transfers6, community-benefit agreements, or other methods to address spillover effects of new developments.

- Where appropriate, provisions to allow each local government to mitigate the scale of change. For example, local governments could limit opt-in upzoning to no more than four floors of housing in areas that are currently zoned exclusively for single-family homes.

A draft of a model Smarter Zoning Code could be developed for $1 million and could be tested by seeking views from a range of stakeholders for $5 million. The model code should be highlighted in HUD’s Regulatory Barriers Clearinghouse.

2. Collect and showcase evidence on effectiveness and impacts of smarter zoning practices

As part of the list of policy-relevant questions in its systematic plan under the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 20187, HUD should include the question of which types of zoning approaches, including smarter zoning, can best (i) help to address or overcome political and other barriers to meeting fair-housing standards, and (ii) support plentiful supplies of affordable housing to address equity and other issues.

HUD should also provide research grants under the Unlocking Possibilities Program8, once passed, to evaluate the impact of Smarter Zoning techniques, suggest improvements to the model Smarter Zoning Code, and prepare and showcase successful case studies of flexible zoning.

Finally, demonstrated thought leadership by the Biden-Harris Administration could kickstart a new wave of innovation in smarter zoning that helps address historic equity issues. HUD should work with the White House and key stakeholder groups (e.g., the American Planning Association, the National League of Cities, the National Governors’ Association) to host a widely publicized event on Planning for Opportunity and Growth. The event would showcase proven, innovative zoning practices that can help state and local government representatives meet housing and growth objectives.

3. Launch smarter-zoning pilot projects

Subject to funding through the Unlocking Possibilities Program, the HUD Secretary should direct HUD’s Office of Technical Assistance and Management to launch a collection of pilot projects for the implementation of the model Smarter Zoning Code. Specifically, HUD would provide planning grants to help states, local governments, and potentially other groups improve skills and technical capacity needed to implement or promote Smarter Zoning reforms. The technical assistance to help a local government adopt smarter zoning, where possible under existing state law, should cost less than $100,000; technical assistance for a state to enable smarter zoning on a state-wide basis should cost less than $500,000.

4. Promote federal incentives and coordination around smarter zoning

Model codes, evidence-based practices, and planning grants can help advance upzoning in areas that are already interested. The federal government could also provide stronger incentives to encourage more reluctant areas to adopt smarter zoning. It is lawful to condition a portion of federal funds upon criteria that are “directly related to one of the main purposes for which [such funds] are expended”, so long as the financial inducement is not “so coercive as to pass the point at which ‘pressure turns into compulsion’”.9 For instance, one of the purposes of highway funds is to reduce congestion in interstate traffic. Failure to allow walkable urban densification limits the opportunities for travel other than by car, which in turn increases congestion on federal highways. It would therefore be constitutional for the federal government to withhold 5% of federal highway funds from states that do not enact smarter zoning provisions. Similarly, funding for affordable home care proposed under the Build Back Better Act will be less effective in areas where exclusionary zoning makes it less affordable for carers to live. A portion of such funding could be withheld from states that do not pass smarter zoning laws. Similar action could be taken on federal funds for education, where unaffordable housing affects the supply of teachers, and on federal funds to fight climate change, because sprawl driven by single-family zoning increases carbon emissions.