A National Blueprint for Whole Health Transformation

Despite spending over 17% of GDP on health care, Americans live shorter and less healthy lives than their peers in other high-income countries. Rising chronic disease and mental health challenges as well as clinician burnout expose the limits of a system built to treat illness rather than create health. Addressing chronic disease while controlling healthcare costs is a bipartisan goal, the question now is how to achieve this shared goal? A policy window is opening now as Congress debates health care again – and in our view, it’s time for a “whole health” upgrade.

Whole Health is a proven, evidence-based framework that integrates medical care, behavioral health, public health, and community support so that people can live healthier, longer, and more meaningful lives. Pioneered by the Veterans Health Administration, Whole Health offers a redesign to U.S. health and social systems: it organizes how health is created and supported across sectors, shifting power and responsibility from institutions to people and communities. It begins with what matters most to people–their purpose, aspirations, and connections–and aligns prevention, clinical care, and social supports accordingly. Treating Whole Health as a shared public priority would help ensure that every community has the conditions to thrive.

Challenge and Opportunity

The U.S. health system spends over $4 trillion annually, more per capita than any other nation, yet underperforms on life expectancy, infant mortality, and chronic disease management. The prevailing fee-for-service model fragments care across medical, behavioral, and social domains, rewarding treatment over prevention. This fragmentation drives costs upward, fuels clinician burnout, and leaves many communities without coordinated support.

At this inflection point in our declining health outcomes and growing public awareness of the failures of our health system, federal prevention and public health programs are under review, governors are seeking cost-effective chronic disease solutions, and the National Academies is advocating for new healthcare models. Additionally, public demand for evidence-based well-being is growing, with 65% of Americans prioritizing mental and social health. There is clear demand for transformation in our health care system to deliver results in a much more efficient and cost effective way.

Veterans Health Administration’s Whole Health System Debuted in 2011

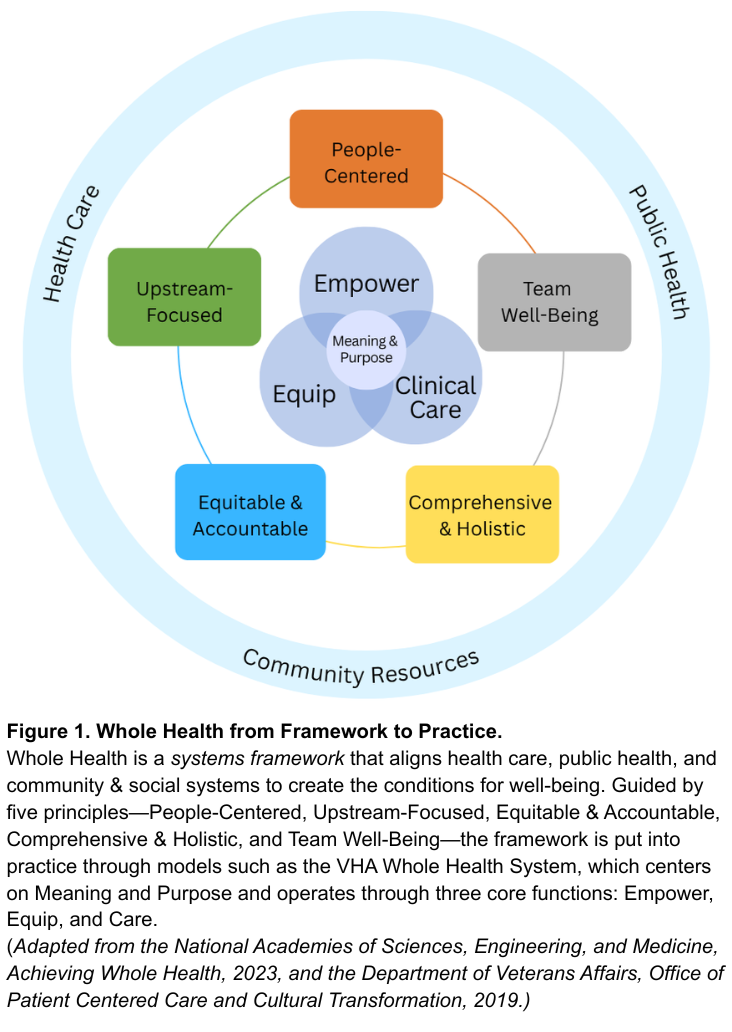

Whole Health offers a system-wide redesign for the challenge at hand. As defined by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Whole Health is a framework for organizing how health is created and supported across sectors. It integrates medical care, behavioral health, public health, and community resources. As shown in Figure 1, the framework connects five system principles—People-Centered, Upstream-Focused, Equitable & Accountable, Comprehensive & Holistic, and Team Well-Being–that guide implementation across health and social support systems. The nation’s largest health system, the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA), has demonstrated this framework in clinical practice through their Whole Health System since 2011. The VHA’s Whole Health System operates through three core functions: Empower (helping individuals define purpose), Equip (providing community resources like peer support), and Clinical Care (delivering coordinated, team-based care). Together, these elements align with what matters most to people, shifting the locus of control from expert-driven systems to shared agency through partnerships. The Whole Health System at the VHA has reduced opioid use and improved chronic disease outcomes.

Successful State Examples

Beyond the VHA, states have also demonstrated the possibility and benefits of Whole Health models. North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots extended Medicaid coverage to housing, food, and transportation, showing fewer emergency visits and savings of about $85 per member per month. Vermont’s Blueprint for Health links primary care practices with community health teams and social services, reducing expenditures by about $480 per person annually and boosting preventive screenings. Finally, the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), currently being implemented in 33 states, utilizes both Medicare and Medicaid funding to coordinate medical and social care for older adults with complex medical needs. While improvements can be made to national program-wide evaluation, states like Kansas have done evaluations that have found that the PACE program is less expensive than nursing homes per beneficiary and that nursing home admissions decline by 5% to 15% for beneficiaries.

Success across each of these examples relies on three pillars: (1) integrating medical, behavioral, social, and public health resources; (2) sustainable financing that prioritizes prevention and coordination; and (3) rigorous evaluation of outcomes that matter to people and communities. While these programs are early signs of success of Whole Health models, without coordinated leadership, efforts will fragment into isolated pilots and it will be challenging to learn and evolve.

A policy window for rethinking the health care system is opening. At this national inflection point, the U.S. can work to build a unified Whole Health strategy that enables a more effective, affordable and resilient health system.

Plan of Action

To act on this opportunity, federal and state leaders can take the following coordinated actions to embed Whole Health as a unifying framework across health, social, and wellbeing systems.

Recommendation 1. Declare Whole Health a Federal and State Priority.

Whole Health should become a unifying value across federal and state government action on health and wellbeing, embedding prevention, connection, and integration into how health and social systems are organized, financed, and delivered. Actions include:

- Federal Executive Action. The Executive Office of the President should create a Whole Health Strategic Council that brings together Veterans Affairs (VA), Health and Human Services (e.g. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)), Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to align strategies, budgets, and programs with Whole Health principles through cross-agency guidance and joint planning. This council should also work with Governors to establish evidence-based benchmarks for Whole Health operations and evaluation (e.g., person-centered planning, peer support, team integration) and shared outcome metrics for well-being and population health.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Authorize whole health benefits, like housing assistance, nutrition counseling, transportation to appointments, peer support programs, and well-being centers as reimbursable services under Medicare, Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act health subsidies.

- State Action. Adopt Whole Health models through Medicaid managed-care contracts and through CDC and HRSA grant implementation. States should also develop support for Whole Health services in trusted local settings such as libraries, faith-based organizations, senior centers, to reach people where they live and gather.

Recommendation 2. Realign Financing and Payment to Reward Prevention and Team-Based Care.

Federal payment modalities need to shift from a fee-for-service model toward hybrid value-based models. Models such as per-member-per-month payments with quality incentives, can sustain comprehensive, team-based care while delivering outcomes that matter, like reductions in chronic disease and overall perceived wellbeing. Actions include:

- Federal Executive Action. Expand Advanced Primary Care Management (APCM) payments to include Whole Health teams, including clinicians, peer coaches, and community health workers. Ensure that this funding supports coordination, person-centered planning, and upstream prevention, such as food as medicine programs. Further, CMS can expand reimbursements to community health workers and peer support roles and standardize their scope-of-practice rules across states.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Invest in Medicare and Medicaid innovation programs, such as the CMS Innovation Center (CMMI), that reward prevention and chronic disease reduction. Additionally, expand tools for payment flexibility, through Medicaid waivers and state innovation funds, to help states adapt Whole Health models to local needs.

- State Action. Require Medicaid managed-care contracts to reimburse Whole Health services, particularly in underserved and rural areas, and encourage payers to align benefit designs and performance measures around well-being. States should also leverage their state insurance departments to guide and incentivize private health insurers to adopt Whole Health payment models.

Recommendation 3. Strengthen and Expand the Whole Health Workforce.

Whole Health practice needs a broad team to be successful: clinicians, community health workers, peer coaches, community organizations, nutritionists, and educators. To build this workforce, governments need to modernize training, assess the workforce and workplace quality, and connect the fast-growing well-being sector with health and community systems. Actions include:

- Federal Executive Action. Through VA and HRSA establish Whole Health Workforce Centers of Excellence to develop national curricula, set standards, and disseminate evidence on effective Whole Health team-building. Further, CMS should track workforce outcomes such as retention, burnout, and team integration, and evaluate the benefits for health professionals working in Whole Health systems versus traditional health systems.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Expand CMS Graduate Medical Education Funds and HRSA workforce programs to support Whole Health training, certifications, and placements across clinical and community settings.

- State Action. As a part of initiatives to grow the health workforce, state governments should expand the definition of a “health professional” to include Whole Health practitioners. Further, states can leverage their role as a licensure for professionals by creating a “whole health” licensing process that recognizes professionals that meet evidence-based standards for Whole Health.

Recommendation 4. Build a National Learning and Research Infrastructure.

Whole Health programs across the country are proving effective, but lessons remain siloed. A coordinated national system should link evidence, evaluation, and implementation so that successful models can scale quickly and sustainably.

- Federal Executive Action. Direct the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health, and partner agencies (VA, HUD, USDA) to run pragmatic trials and cost-effectiveness studies of Whole Health interventions that measure well-being across clinical, biomedical, behavioral, and social domains. The federal government should also embed Whole Health frameworks into government-wide research agendas to sustain a culture of evidence-based improvement.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Charter a quasi-governmental entity, modeled on Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), to coordinate Whole Health demonstration sites and research. This new entity should partner with CMMI, HRSA and VA to test Whole Health payment and delivery models under real-world conditions. This entity should also establish an interagency team as well as state network to address payment, regulatory, and privacy barriers identified by sites and pilots.

- State Action. Partner with federal agencies through innovation waivers (e.g. 1115 waivers and 1332 waivers) and learning collaboratives to test Whole Health models and share data across state systems and with the federal government.

Conclusion

The United States spends more on health care than any other nation yet delivers poorer outcomes. Whole Health offers a proven path to reverse this trend, reframing care around prevention, purpose, and integration across health and social systems. Embedding Whole Health as the operating system for America’s health requires three shifts: (1) redefining the purpose from treating disease to optimizing health and well-being; (2) restructuring care to empower, equip, and treat through team-based and community-linked approaches; and (3) rebalancing control from expert-driven systems to partnerships guided by what matters most to people and communities. Federal and state leaders have the opportunity to turn scattered Whole Health pilots to a coordinated national strategy. The cost of inaction is continued fragmentation; the reward of action is a healthier and more resilient nation.

This memo produced as part of Strengthening Pathways to Disease Prevention and Improved Health Outcomes.

Both approaches emphasize caring for people as integrated beings rather than as a collection of diseases, but they differ in scope and application. Whole Person Health, as used by NIH, focuses on the biological, psychological, and behavioral systems within an individual—it is primarily a research framework for understanding health across body systems. Whole Health is a systems framework that extends beyond the individual to include families, communities, and environments. It integrates medical care, behavioral health, public health, and social support around what matters most to each person. In short, Whole Person Health is about how the body and mind work together; Whole Health is about how health, social, and community systems work together to create the conditions for well-being. Policymakers can use Whole Health to guide financing, workforce, and infrastructure reforms that translate Whole Person Health science into everyday practice.

Integrative Health combines evidence-based conventional and complementary approaches such as mindfulness, acupuncture, yoga, and nutrition to support healing of the whole person. Whole Health extends further. It includes prevention, self-care, and personal agency, and moves beyond the clinic to connect medical care with social, behavioral, and community dimensions of health. Whole Health uses integrative approaches when evidence supports them, but it is ultimately a systems model that aligns health, social, and community supports around what matters most to people. For policymakers, it provides a structure for integrating clinical and community services within financing and workforce strategies.

They share a common foundation but differ in scope and audience. The VA Whole Health System, developed by the Department of Veterans Affairs, is an operational model, a way of delivering care that helps veterans identify what matters most, supports self-care and skill building, and provides team-based clinical treatment. The National Academies’ Whole Health framework builds on the VA’s experience and expands it to the national level. It is a policy and systems framework that applies Whole Health principles across all populations and connects health care with public health, behavioral health, and community systems. In short, the VA model shows how Whole Health works in practice, while the National Academies framework shows how it can guide national policy and system alignment.

In Honor of Patient Safety Day, Four Recommendations to Improve Healthcare Outcomes

Through partnership with the Doris Duke Foundation, FAS is working to ensure that rigorous, evidence-based ideas on the cutting edge of disease prevention and health outcomes are reaching decision makers in an effective and timely manner. To that end, we have been collaborating with the Strengthening Pathways effort, a series of national conversations held in spring 2025 to surface research questions, incentives, and overlooked opportunities for innovation with potential to prevent disease and improve outcomes of care in the United States. FAS is leveraging its skills in policy entrepreneurship, working with session organizers, to ensure that ideas surfaced in these symposia reach decision-makers to drive impact in active policy windows.

On this World Patient Safety Day 2025, we share a set of recommendations that align with the National Quality Strategy of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) goal for zero preventable harm in healthcare. Working with Patients for Patient Safety US, which co-led one of Strengthening Pathways conversations this spring with the Johns Hopkins University Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, the issue brief below outlines a bold, modernized approach that uses Artificial Intelligence technology to empower patients and drive change. FAS continues to explore the rapidly evolving AI and healthcare nexus.

Patient safety is an often-overlooked challenge in our healthcare systems. Whether safety events are caused by medical error, missed or delayed diagnoses, deviations from standards of care, or neglect, hundreds of billions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of lives are lost each year due to patient safety lapses in our healthcare settings. But most patient safety challenges are not really captured and there are not enough tools to empower clinicians to improve. Here we present four critical proposals for improving patient safety that are worthy of attention and action.

Challenge and Opportunity

Reducing patient death and harm from medical error surfaced as a U.S. public health priority at the turn of the century with the landmark National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System (2000). Research shows that medical error is the 3rd largest cause of preventable death in the U.S. Analysis of Medicare claims data and electronic health records by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Office of the Inspector General (OIG) in a series of reports from 2008 to 2025 consistently finds that 25-30% of Medicare recipients experience harm events across multiple healthcare settings, from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities to long term care hospitals to rehab centers. Research on the broader population finds similar rates for adult patients in hospitals. The most recent study on preventable harm in ambulatory care found that 7% of patients experienced at least one adverse event, with wide variation of 1.8% to 23.6% from clinical setting to clinical setting. Improving diagnostic safety has emerged as the largest opportunity for patient harm prevention. New research estimates 795,000 patients in the U.S. annually experience death or harm due to missed, delayed or ineffectively communicated diagnoses. The annual cost to the health care system of preventable harm and its health care cascades is conservatively estimated to exceed $200 billion. This cost is ultimately borne by families and taxpayers.

In its National Quality Strategy, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) articulated an aspirational goal of zero preventable harm in healthcare. The National Action Alliance for Patient and Workforce Safety, now managed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), has a goal of 50% reduction in preventable harm by 2026. These goals cannot be achieved without a bold, modernized approach that uses AI technology to empower patients and drive change. Under-reporting negative outcomes and patient harms keeps clinicians and staff from identifying and implementing solutions to improve care. In its latest analysis (July 2025), the OIG finds that fewer than 5% of medical errors are ever reported to the systems designed to gather insights from them. Hospitals failed to capture half of harm events identified via medical record review, and even among captured events, few led to investigation or safety improvements. Only 16% of events required to be reported externally to CMS or State entities were actually reported, meaning critical oversight systems are missing safety signals entirely.

Multiple research papers over the last 20 years find that patients will report things that providers do not. But there has been no simple, trusted way for patient observations to reach the right people at the right time in a way that supports learning and Improvement. Patients could be especially effective in reporting missed or delayed diagnoses, which often manifest across the continuum of care, not in one healthcare setting or a single patient visit. The advent of AI systems provides an unprecedented opportunity to address patient safety and improve patient outcomes if we can improve the data available on the frequency and nature of medical errors. Here we present four ideas for improving patient safety.

Recommendation 1. Create AI-Empowered Safety Event Reporting and Learning System With and For Patients

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) can, through CMS, AHRQ or another HHS agency, develop an AI-empowered National Patient Safety Learning and Reporting System that enables anyone, including patients and families, to directly report harm events or flag safety concerns for improvement, including in real or near real time. Doing so would make sure everyone in the system has the full picture — so healthcare providers can act quickly, learn faster, and protect more patients.

This system will:

- Develop a reporting portal to collect, triage and analyze patient reported data directly from beneficiaries to improve patient and diagnostic safety.

- Redesign and modernize Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems

(CAHPS) surveys to include questions that capture beneficiaries’ experiences and outcomes related to patient and diagnostic safety events.

- Redefine the Beneficiary and Family Centered Care Quality Improvement Organizations (BFCC QIO) scope of work to integrate the QIOs into the National Patient Safety Learning and Reporting System.

The learning system will:

- Use advanced triage (including AI) to distinguish high-signal events and route credible

reports directly to the care team and oversight bodies that can act on them.

- Solicit timely feedback and insights in support of hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes to prevent recurrence, as well as feedback over time on patient outcomes that manifest later, e.g. as a result of missed or delayed diagnoses.

- Protect patients and providers by focusing on efficacy of solutions, not blame assignment.

- Feed anonymized, interoperable data into a national learning network that will spot systemic risks sooner and make aggregated data available for transparency and system learning.

Recommendation 2. Create a Real-time ‘Patient Safety Dashboard’ using AI

HHS should build an AI-driven platform that integrates patient-reported safety data — including data from the new National Patient Reporting and Learning System, recommended above — with clinical data from electronic health records to create a real-time ‘patient safety dashboard’ for hospitals and clinics. This dashboard will empower providers to improve care in real time, and will:

- Assist health care providers make accurate and timely diagnoses and avoid errors.

- Make patient reporting easy, effective, and actionable.

- Use AI to triage harm signals and detect systemic risk in real time.

- Build shared national infrastructure for healthcare reporting for all stakeholders.

- Align incentives to reward harm reduction and safety.

By harnessing the power of AI providers will be able to respond faster, identify patients at risk more effectively, and prevent harm thereby improving outcomes. This “central nervous system” for patient safety will be deployed nationally to help detect safety signals in real time, connect information across settings, and alert teams before harm occurs.

Recommendation 3. Mine Billing Data for Deviations from Standards of Care

Standards of care are guidelines that define the process, procedures and treatments that patients should receive in various medical and professional contexts. Standards ensure that individuals receive appropriate and effective care based on established practices. Most standards of care are developed and promulgated by medical societies. But not all clinicians and clinical settings adhere to standards of care, and deviations from standards of care are normal depending upon the case before them. Nonetheless, standards of care exist for a reason and deviations from standards of care should be noted when medical errors result in negative outcomes for patients so that clinicians can learn from these outcomes and improve.

Some patient safety challenges are evident right in the billing data submitted to CMS and insurers. For example, deviations from standards of care can be captured in billing data by comparing clinical diagnosis codes with billing codes and then compared to widely accepted standards of care. By using CMS billing data, the government could identify opportunities for driving the development, augmentation, and wider adoption of standards of care by showing variability and compliance with standards of care for patients, reducing medical error and improving outcomes.

Giving standard setters real data to adapt and develop new standards of care is a powerful tool for improving patient outcomes.

Recommendation 4. Create a Patient Safety AI Testbed

HHS can also establish a Patient Safety AI Testbed to evaluate how AI tools used in diagnosis, monitoring, and care coordination perform in real-world settings. This testbed will ensure that AI improves safety, not just efficiency — and can be co-led by patients, clinicians, and independent safety experts. This is an expansion of the testbeds in the HHS AI Strategic Plan.

The Patient Safety Testbed could include:

- Funding for independent AI test environments to monitor real-world safety and performance over time.

- Public reliability benchmarks and “AI safety labeling”.

- Required participation by AI vendors and provider systems.

Conclusion

There are several key steps that the government can take to address the major loss of health, dollars, and lives due to medical errors, while simultaneously bolstering treatment guidelines, driving the development of new transparent data, and holding the medical establishment accountable for improving care. Here we present four proposals. None of them are particularly expensive when juxtaposed against the tremendous savings they will drive throughout our healthcare system. We can only hope that the Administration’s commitment to patient safety is such that they will adopt them and drive a new era where caregivers, healthcare systems and insurance payers work together to improve patient safety and care standards.

This memo produced as part of Strengthening Pathways to Disease Prevention and Improved Health Outcomes.

Terminal Patients Need Better Access to Drugs and Clinical Trial Information

Editor’s note: This policy memo was written by Jake Seliger and his wife Bess Stillman. Jake passed away before meeting his child, Athena, born on October 31, 2024. Except where indicated, the first-person voice is that of Jake. This memo advocates for user-centric technology modernization and data interoperability. More crucially, he urges expanded patient rights to opt-in to experimental drug trials and FDA rule revisions to enable terminal patients to take more risks on behalf of themselves, for the benefit of others.

The FDA is supposed to ensure that treatments are safe and effective, but terminal cancer patients like me are already effectively dead. If I don’t receive advanced treatment quickly, I will die. My hope, in the time I have remaining, is to promote policies that will speed up access to treatments and clinical trials for cancer patients throughout the U.S.

There are about two million cancer diagnoses and 600,000 deaths annually in the United States. Cancer treatments are improved over time via the clinical trial system: thousands of clinical trials are conducted each year (many funded by the government via the National Institutes of Health, or NIH, and many funded by pharmaceutical companies hoping to get FDA approval for their products).

But the clinical trial system is needlessly slow, and as discussed below, is nearly impossible for any layperson to access without skilled consulting. As a result, clinical trials are far less useful than they could be.

The FDA is currently “protecting” me from being harmed or killed by novel, promising, advanced cancer treatments that could save or extend my life, so that I can die from cancer instead. Like most patients, I would prefer a much faster system in which the FDA conditionally approves promising, early-phase advanced cancer treatments, even if those treatments haven’t yet been proven fully effective. Drugmakers will be better incentivized to invest in novel cancer treatments if they can begin receiving payment for those treatments sooner. The true risks to terminal patients like me are low—I’m already dying—and the benefits to both existing terminal patients and future patients of all kinds are substantial.

I would also prefer a clinical trial system that was easy for patients to navigate, rather than next-to-impossible. Easier access for patients could radically lower the cost and time for clinical trials by making recruitment far cheaper and more widespread, rather than including only about 6% of patients. In turn, speeding up the clinical-trial process means that future cancer patients will be helped by more quickly approving novel treatments. About half of pharmaceutical R&D spending goes not to basic research, but to the clinical trial process. If we can cut the costs of clinical trials by streamlining the process to improve access to terminal patients, more treatments will make it to patients, and will be faster in doing so.

Cancer treatment is a non-partisan issue. To my knowledge, both left and right agree that prematurely dying from cancer is bad. Excess safety-ism and excessive caution from the FDA costs lives, including in the near future, my own. Three concrete actions would improve clinical research, particular for terminal cancer patients like me, but for many other patients as well:

Clinical trials should be easier and cheaper. The chief obstacles to this are recruitment and retention.

Congress and NIH should modernize the website ClinicalTrials.gov and vastly expand what drug companies and research sites are required to report there, and the time in which they must report it. Requiring timely updates that include comprehensive eligibility criteria, availability for new participants, and accurate site contact information,would mean that patients and doctors will have much more complete information about what trials are available and for whom.

The process of determining patient eligibility and enrolling in a trial should be easier. Due to narrow eligibility criteria, studies struggle to enroll an adequate number of local patients, which severely delays trial progression. A patient who wishes to participate in a trial must “establish care” with the hospital system hosting the trial, before they are even initially screened for eligibility or told if a slot is available. Due to telemedicine practice restrictions across state lines, this means that patients who aren’t already cared for at that site— patients who are ill and for whom unnecessary travel is a huge burden— must use their limited energy to travel to a site just to find out if they can proceed to requesting a trial slot and starting further eligibility testing. Then, if approved for the study, they must be able to uproot their lives to move to, or spend extensive periods of time at, the study location

Improved access to remote care for clinical trials would solve both these problems. First, by allowing the practice of telemedicine across state lines for visits directly related to screening and enrollment into clinical trials. Second, by incentivizing decentralization—meaning a participant in the study can receive the experimental drug and most monitoring, labs and imaging at a local hospital or infusion clinic—by accepting data from sites that can follow a standardized study protocol.

We should require the FDA to allow companies with prospective treatments for fatal diseases to bring those treatments to market after initial safety studies, with minimal delays and with a lessened burden for demonstrating benefit.

Background

[At the time of writing this] I’m a 40-year-old man whose wife is five months pregnant, and the treatment that may keep me alive long enough to meet my child is being kept from me because of current FDA policies. That drug may be in a clinical trial I cannot access. Or, it may be blocked from coming to market by requirements for additional testing to further prove efficacy that has already been demonstrated.

Instead of giving me a chance to take calculated risks on a new therapy that might allow me to live and to be with my family, current FDA regulations are choosing for me: deciding that my certain death from cancer is somehow less harmful to me than taking a calculated, informed risk that might save or prolong my life. Who is asking the patients being protected what they would rather be protected from? The FDA errs too much on the side of extreme caution around drug safety and efficacy, and that choice leads to preventable deaths.

One group of scholars attempted to model how many lives are lost versus gained from a more or less conservative FDA. They find that “from the patient’s perspective, the approval criteria in [FDA program accelerators] may still seem far too conservative.” Their analysis is consistent with the FDA being too stringent and slow in approving use of drugs for fatal diseases like cancer: “Our findings suggest that conventional standards of statistical significance for approving drugs may be overly conservative for the most deadly diseases.”

Drugmakers also find it difficult to navigate what exactly the FDA wants: “their deliberations are largely opaque—even to industry insiders—and the exact role and weight of patient preferences are unclear.” This exacerbates the difficulty drugmakers face in seeking to get treatments to patients faster. Inaction in the form of delaying patient access to drugs is killing people. Inaction is choosing death for cancer patients.

I’m an example of this; I was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the tongue in Oct. 2022. I had no risk factors, like smoking or alcoholism, that put me at risk for SCC. The original tumor was removed in October 2022, and I then had radiation that was supposed to cure me. It didn’t, and the cancer reappeared in April 2023. At that point, I would’ve been a great candidate for a drug like MCLA-158, which has been stuck in clinical trials, despite “breakthrough therapy designation” by the FDA and impressive data, for more than five years. This, despite the fact that MCLA-158 is much easier to tolerate than chemotherapy and arrests cancer in about 70% of patients. Current standard of care chemotherapy and immunotherapy has a positive response rate of only 20-30%.

Had MCLA-158 been approved, I might have received it in April 2023, and still have my tongue. Instead, in May 2023, my entire tongue was surgically removed in an attempt to save my life, forever altering my ability to speak and eat and live a normal life. That surgery removed the cancer, but two months later it recurred again in July 2023. While clinical-trial drugs are keeping me alive right now, I’m dying in part because promising treatments like MCLA-158 are stuck in clinical trials, and I couldn’t get them in a timely fashion, despite early data showing their efficacy. Merus, the maker of MCLA-158, is planning a phase 3 trial for MCLA-158, despite its initial successes. This is crazy: head and neck cancer patients need MCLA-158 now.

I’m only writing this brief because I was one of the few patients who was indeed, at long last, able to access MCLA-158 in a clinical trial, which incredibly halted my rapidly expanding, aggressive tumors. Without it, I’d have been dead nine months ago. Without it, many other patients already are. Imagine that you, or your spouse, or parent, or child, finds him or herself in a situation like mine. Do you want the FDA to keep testing a drug that’s already been shown to be effective and allow patients who could benefit to suffer and die? Or do you want your loved one to get the drug, and avoid surgical mutilation and death? I know what I’d choose.

Multiply this situation across hundreds of thousands of people per year and you’ll understand the frustration of the dying cancer patients like me.

As noted above, about 600,000 people die annually from cancer—and yet cancer drugs routinely take a decade or more to move from lab to approval. The process is slow: “By the time a drug gets into phase III, the work required to bring it to that point may have consumed half a decade, or longer, and tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars.” If you have a fatal disease today, a treatment that is five to ten years away won’t help. Too few people participate in clinical trials partly because participation is so difficult; one study finds that “across the entire U.S. system, the estimated participation rate to cancer treatment trials was 6.3%.” Given how many people die, the prospect of life is attractive.

There is another option in between waiting decades for a promising drug to come to market and opening the market to untested drugs: Allowing terminal patients to consent to the risk of novel, earlier-phase treatments, instead of defaulting to near-certain death, would potentially benefit those patients as well as generate larger volumes of important data regarding drug safety and efficacy, thus improving the speed of drug approval for future patients. Requiring basic safety data is reasonable, but requiring complete phase 2 and 3 data for terminal cancer patients is unreasonably slow, and results in deaths that could be prevented through faster approval.

Again, imagine you, your spouse, parent, or child, is in a situation like mine: they’ve exhausted current standard-of-care cancer treatments and are consequently facing certain death. New treatments that could extend or even save their life may exist, or be on the verge of existing, but are held up by the FDA’s requirements that treatments be redundantly proven to be safe and highly effective. Do you want your family member to risk unproven but potentially effective treatments, or do you want your family member to die?

I’d make the same choice. The FDA stands in the way.

Equally important, we need to shorten the clinical trial process: As Alex Telford notes, “Clinical trials are expensive because they are complex, bureaucratic, and reliant on highly skilled labour. Trials now cost as much as $100,000 per patient to run, and sometimes up to $300,000 or even $500,000 per patient.” And as noted above, about half of pharmaceutical R&D spending goes not to basic research, but to the clinical trial process.

Cut the costs of clinical trials, and more treatments will make it to patients, faster. And while it’s not reasonable to treat humans like animal models, a lot of us who have fatal diagnoses have very little to lose and consequently want to try drugs that may help us, and people in the future with similar diseases. Most importantly, we understand the risks of potentially dying from a drug that might help us and generate important data, versus waiting to certainly die from cancer in a way that will not benefit anybody. We are capable of, and willing to give, informed consent. We can do better and move faster than we are now. In the grand scheme of things, “When it comes to clinical trials, we should aim to make them both cheaper and faster. There is as of yet no substitute for human subjects, especially for the complex diseases that are the biggest killers of our time. The best model of a human is (still) a human.” Inaction will lead to the continued deaths of hundreds of thousands of people annually.

Trials need patients, but the process of searching for a trial in which to enroll is archaic. We found ClinicalTrials.gov nearly impossible to navigate. Despite the stakes, from the patient’s perspective, the clinical trial process is impressively broken, obtuse and confusing, and one that we gather no one likes: patients don’t, their families don’t, hospitals and oncologists who run the clinical trials don’t, drug companies must not, and the people who die while waiting to get into a trial probably don’t.

I [Bess] knew that a clinical trial was Jake’s only chance. But how would we find one? I’d initially hoped that a head and neck oncologist would recommend a specific trial, preferably one that they could refer us to. But most doctors didn’t know of trial options outside their institution, or, frequently, within it, unless they were directly involved. ,Most recommended large research institutions that had a good reputation for hard cases, assuming they’d have more studies and one might be a match.

How were they, or we, supposed to find out what trials actually existed?

The only large-scale search option is ClinicalTrials.gov. But many oncologists I spoke with don’t engage with ClinicalTrials.gov, because the information is out-of-date, difficult to navigate, and inaccurate. It can’t be relied on. For example, I shared a summary of Jake’s relevant medical information (with his permission) in a group of physicians who had offered to help us with the clinical trial search. Ten physicians shared their top-five search results. Ominously, none listed the same trials.

How is it that ten doctors can put in the same basic, relevant clinical data into an engine meant to list and search for all existing clinical trials, only for no two to surface the same study? The problem is simple: There’s a lack of keyword standardization.

Instead of a drop-down menu or click-boxes with diagnoses to choose from, the first search “filter” on ClinicalTrials.gov is a text box that says “Condition\Disease.” If I search: “Head and Neck Cancer” I get ___________ results. If I search “Tongue Cancer,” I get _________ results. Although Tongue Cancer is a subset of Head and Neck Cancer, I don’t see the studies listed as “Head and Neck Cancer”, unless I type in both, or the person who created the ClinicalTrials.gov post for the study chose to type out multiple variations on a diagnosis. Nothing says they have to. If I search for both, I will still miss studies filed as: “HNSCC” or “All Solid Tumors” or “Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Tongue.”

The good news is that online retailers solved this problem for us years ago. It’s easier to find a dress to my exact specifications out of thousands on H&M,com than it is to find a clinical trial. I can open a search bar, click “dress,” select my material from another click box (which allows me to select from the same options the people listing the garments chose from), then click on the boxes for my desired color, dry clean or machine wash, fabric, finish, closure, and any other number of pre-selected categories before adding additional search keywords if I choose. I find a handful of options all relevant to my desires within a matter of minutes. H&M provides a list of standardized keywords describing what they are offering, and I can filter from there. This way, H&M and I are speaking the same language. And a dress isn’t life or death. For much more on my difficulties with ClinicalTrials.gov, see here.

Further slowing a patient’s ability to find a relevant clinical trial is a lack of comprehensive, searchable, eligibility criteria. Every study has eligibility criteria, and eligibility criteria—like keywords—aren’t standardized on ClinicalTrials.gov. Nor is it required that an exhaustive explanation of eligibility criteria be provided, which may lead to a patient wasting precious weeks attempting to establish care and enroll in a trial, only to discover there was unpublished eligibility criteria they don’t meet. Instead, the information page for each study outlines inclusion and exclusion criteria using whatever language whoever is typing feels like using. Many have overlapping inclusion and exclusion criteria, but there can be long lists of additional criteria for each arm of a study, and it’s up to the patient or their doctor to read through them line by line—if they’re even listed— to see if prior medications, current medications, certain genomic sequencing findings, numbers of lines of therapy, etc. makes the trial relevant.

In the end, we hired a consultant (Eileen), who leveraged her full-time work helping pharmaceutical companies determine which novel compounds might be worth pouring their R&D efforts into assisting patients find potential clinical trials. She helped us narrow it down to the top 5 candidate trials from the thousands that turned up in initial queries.

- NCT04815720: Pepinemab in Combination With Pembrolizumab in Recurrent or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (KEYNOTE-B84)

- NCT03526835: A Study of Bispecific Antibody MCLA-158 in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors.

- NCT05743270: Study of RP3 in Combination With Nivolumab and Other Therapy in Patients With Locoregionally Advanced or Recurrent SCCHN.”

- NCT03485209: Efficacy and Safety Study of Tisotumab Vedotin for Patients With Solid Tumors (innovaTV 207)

- NCT05094336: AMG 193, Methylthioadenosine (MTA) Cooperative Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) Inhibitor, Alone and in Combination With Docetaxel in Advanced Methylthioadenosine Phosphorylase (MTAP)-Null Solid Tumors (MTAP).

Based on the names alone, you can see why it would be difficult if not impossible for someone without some expertise in cancer oncology to evaluate trials. Even with Eileen’s expertise, two of the trials were stricken from our list when we discovered unlisted eligibility criteria, which excluded Jake. When exceptionally motivated patients, the oncologists who care for them, and even consultants selling highly specialized assistance can’t reliably navigate a system that claims to be desperate to enroll patients into trials, there is a fundamental problem with the system. But this is a mismatch we can solve, to everyone’s benefit.

Plan of Action

We propose three major actions. Congress should:

Recommendation 1. Direct the National Library of Medicine (NLM) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to modernize ClinicalTrials.gov so that patients and doctors have complete and relevant information about available trials, as well as requiring more regular updates from companies as to all the details of available trials, and

Recommendation 2. Allow the practice of telemedicine across state lines for visits related to clinical trials.

Recommendation 3. Require the FDA to allow companies with prospective treatments for fatal diseases to bring those treatments to market after initial safety studies.

Modernizing ClinicalTrials.gov will empower patients, oncologists, and others to better understand what trials are available, where they are available, and their up-to-date eligibility criteria, using standardized search categories to make them more easily discoverable. Allowing telemedicine across state lines for clinical trial care will significantly improve enrollment and retention. Bringing treatments to market after initial safety studies will speed the clinical trial process, and get more patients treatments, sooner. In cancer, delays cause death.

To get more specific:

The FDA already has a number of accelerated approval options. Instead of the usual “right to try” legislation, we propose creating a second, provisional market for terminal patients that allows partial approval of a drug while it’s still undergoing trials, making it available to trial-ineligible (or those unable to easily access a trial) patients for whom standard of care doesn’t provide a meaningful chance at remission. This partial approval would ideally allow physicians to prescribe the drug to this subset of patients as they see fit: be that monotherapy or a variety of personalized combination therapies, tailored to a patient’s needs, side-effect profile and goals. This wouldn’t just expand access to patients who are otherwise out of luck, but can give important data about real-world reaction and response.

As an incentive, the FDA could require pharmaceutical companies to provide drug access to terminal patients as a condition of continuing forward in the trial process on the road to a New Drug Application. While this would be federally forced compassion, it would differ from “compassionate use.” To currently access a study drug via compassionate use, a physician has to petition both the drug company and the FDA on the patient’s behalf, which comes with onerous rules and requirements. Most drug companies with compassionate use programs won’t offer a drug until there’s already a large amount of compelling phase 2 data demonstrating efficacy, a patient must have “failed” standard of care and other available treatments, and the drug must (usually) be given as a monotherapy. Even if the drugmaker says yes, the FDA can still say no. Compassionate use is an option available to very small numbers, in limited instances, and with bureaucratic barriers to overcome. Not terribly compassionate, in my opinion.

The benefits of this “terminal patient” market can and should go both ways, much as lovers should benefit from each other instead of trying to create win-lose situations. Providing the drug to patients would come with reciprocal benefits to the pharmaceutical companies. Any physician prescribing the drug to patients should be required to report data regarding how the drug was used, in what combination, and to what effect. This would create a large pool of observational, real-world data gathered from the patients who aren’t ideal candidates for trials, but better represent the large subset of patients who’ve exhausted multiple lines of therapies yet aren’t ready for the end. Promising combinations and unexpected effects might be identified from these observational data sets, and possibly used to design future trials.

Dying patients would get drugs faster, and live longer, healthier lives, if we can get better access to both information about clinical trials, and treatments for diseases. The current system errs too much on proving effectiveness and too little on the importance of speed itself, and of the number of people who die while waiting for new treatments. Patients like me, who have fatal diagnoses and have already failed “standard of care” therapies, routinely die while waiting for new or improved treatments. Moreover, patients like me have little to lose: because cancer is going to kill us anyway, many of us would prefer to roll the dice on an unproven treatment, or a treatment that has early, incomplete data showing its potential to help, than wait to be killed by cancer. Right now, however, the FDA does not consider how many patients will die while waiting for new treatments. Instead, the FDA requires that drugmakers prove both the safety and efficacy of treatments prior to allowing any approval whatsoever.

As for improving ClinicalTrials.gov, we have several ideas:

First, the NIH should hire programmers with UX experience, and should be empowered to pay market rates to software developers with experience at designing websites for, say, Amazon or Shein. Clinicaltrials.gov was designed to be a study registry, but needs an overhaul to be more useful to actual patients and doctors.

Second, UX is far from the only problem. Data itself can be a problem. For example, the NIH could require a patient-friendly summary of each trial; it could standardize the names of drugs and conditions so that patients and doctors could see consistent and complete search results; and it could use a consistent and machine-readable format for inclusion and exclusion criteria.

We are aware of one patient group that, in trying to build an interface to ClinicalTrials.gov, found a remarkable degree of inconsistency and chaos: “We have analyzed the inclusion and exclusion criteria for all the cancer-related trials from clinicaltrials.gov that are recruiting for interventional studies (approximately 8,500 trials). Among these trials, there are over 1,000 ways to indicate the patient must not be pregnant during a trial, and another 1,000 ways to indicate that the patient must use adequate birth control.” ClinicalTrials.gov should use a Domain Specific Language that standardizes all of these terms and conditions, so that patients and doctors can find relevant trials with 100x less effort.

Third, the long-run goal should be a real-time, searchable database that matches patients to studies using EMR data and allows doctors to see what spots are available and where. Pharmaceutical and biotech companies would need to be required to contribute up-to-date information on all extant clinical trials on a regular basis (e.g., monthly).

Conclusion

Indeed, we need a national clinical trial database that EMRs can connect to, in the style of Epic’s Care Everywhere. A patient signs a release to share their information, like Care Everywhere allows hospital A to download a patient’s information from hospital B if the patient signs a release. Trials with open slots could mark themselves as “recruiting” and update in real time. A doctor could press a button and identify potential open studies. A patient available for a trial could flag their EMR profile as actively searching, allowing clinical trial sites to browse patients in their region who are looking for a study. Access to that patient’s EMR would allow them to scan for eligibility.

This would be easy to do. OKCupid can do it. The tech exists. Finding a clinical trial already feels a bit like online dating, except if you get the wrong match, you die.

This memo produced as part of the Federation of American Scientists and Good Science Project sprint. Find more ideas at Good Science Project x FAS

The FDA has created a variety of programs that have promising-sounding names: “Currently, four programs—the fast track, breakthrough therapy, accelerated approval, and priority review designations—provide faster reviews and/or use surrogate endpoints to judge efficacy. However, published descriptions […] do not indicate any differences in the statistical thresholds used in these programs versus the standard approval process, nor do they mention adapting these thresholds to the severity of the disease.” The problem is that these programs do not appear to do much to actually accelerate getting drugs to patients. MCLA-158 is an example of the problem: the drug has been shown to be safe and effective, and yet Merus thinks it needs a Phase 3 trial to get it past the FDA and to patients.

Improve healthcare data capture at the source to build a learning health system

Studies estimate that only one in 10 recommendations made by major professional societies are supported by high-quality evidence. Medical care that is not evidence-based can result in unnecessary care that burdens public finances, harms patients, and damages trust in the medical profession. Clearly, we must do a better job of figuring out the right treatments, for the right patients, at the right time. To meet this challenge, it is essential to improve our ability to capture reusable data at the point of care that can be used to improve care, discover new treatments, and make healthcare more efficient. To achieve this vision, we will need to shift financial incentives to reward data generation, change how we deliver care using AI, and continue improving the technological standards powering healthcare.

The Challenge and Opportunity of health data

Many have hailed health data collected during everyday healthcare interactions as the solution to some of these challenges. Congress directed the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to increase the use of real-world data (RWD) for making decisions about medical products. However, FDA’s own records show that in the most recent year for which data are available, only two out of over one hundred new drugs and biologics approved by FDA were approved based primarily on real-world data.

A major problem is that our current model in healthcare doesn’t allow us to generate reusable data at the point of care. This is even more frustrating because providers face a high burden of documentation, and patients report repetitive questions from providers and questionnaires.

To expand a bit: while large amounts of data are generated at the point of care, these data lack the quality, standardization, and interoperability to enable downstream functions such as clinical trials, quality improvement, and other ways of generating more knowledge about how to improve outcomes.

By better harnessing the power of data, including results of care, we could finally build a learning healthcare system where outcomes drive continuous improvement and where healthcare value leads the way. There are, however, countless barriers to such a transition. To achieve this vision, we need to develop new strategies for the capture of high-quality data in clinical environments, while reducing the burden of data entry on patients and providers.

Efforts to achieve this vision follow a few basic principles:

- Data should be entered only once– by the person or entity most qualified to do so – and be used many times.

- Data capture should be efficient, so as to minimize the burden on those entering the data, allowing them to focus their time on doing what actually matters, like providing patient care.

- Data generated at the point of care needs to be accessible for appropriate secondary uses (quality improvement, trials, registries), while respecting patient autonomy and obtaining informed consent where required. Data should not be stuck in any one system but should flow freely between systems, enabling linkages across different data sources.

- Data need to be used to provide real value to patients and physicians. This is achieved by developing data visualizations, automated data summaries, and decision support (e.g. care recommendations, trial matching) that allow data users to spend less time searching for data and more time on analysis, problem solving, and patient care– and help them see the value in entering data in the first place.

Barriers to capturing high-quality data at the point of care:

- Incentives: Providers and health systems are paid for performing procedures or logging diagnoses. As a result, documentation is optimized for maximizing reimbursement, but not for maximizing the quality, completeness, and accuracy of data generated at the point of care.

- Workflows: Influenced by the prevailing incentives, clinical workflows are not currently optimized to enable data capture at the point of care. Patients are often asked the same questions at multiple stages, and providers document the care provided as part of free-text notes, which are frequently required for billing but can make it challenging to find information.

- Technology: Shaped by incentives and workflows, technology has evolved to capture information in formats that frequently lack standardization and interoperability.

Plan of Action

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Incentivize generation of reusable data at the point of care

Financial incentives are needed to drive the development of workflows and technology to capture high-quality data at the point of care. There are several payment programs already in existence that could provide a template for how these incentives could be structured.

For example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced the Enhancing Oncology Model (EOM), a voluntary model for oncology providers caring for patients with common cancer types. As part of the EOM, providers are required to report certain data fields to CMS, including staging information and hormone receptor status for certain cancer types. These data fields are essential for clinical care, research, quality improvement, and ongoing care observation involving cancer patients. Yet, at present, these data are rarely recorded in a way that makes it easy to exchange and reuse this information. To reduce the burden of reporting this data, CMS has collaborated with the HHS Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy (ASTP) to develop and implement technological tools that can facilitate automated reporting of these data fields.

CMS also has a long-standing program that requires participation in evidence generation as a prerequisite for coverage, known as coverage with evidence development (CED). For example, hospitals that would like to provide Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) are required to participate in a registry that records data on these procedures.

To incentivize evidence generation as part of routine care, CMS should refine these programs and expand their use. This would involve strengthening collaborations across the federal government to develop technological tools for data capture, and increasing the number of payment models that require generation of data at the point of care. Ideally, these models should evolve to reward 1) high-quality chart preparation (assembly of structured data) 2) establishing diagnoses and development of a care plan, and 3) tracking outcomes. These payment policies are powerful tools because they incentivize the generation of reusable infrastructure that can be deployed for many purposes.

Recommendation 2. Improve workflows to capture evidence at the point of care

With the right payment models, providers can be incentivized to capture reusable data at the point of care. However, providers are already reporting being crushed by the burden of documentation and patients are frequently filling out multiple questionnaires with the same information. To usher in the era of the learning health system (a system that includes continuous data collection to improve service delivery), without increasing the burden on providers and patients, we need to redesign how care is provided. Specifically, we must focus on approaches that integrate generation of reusable data into the provision of routine clinical care.

While the advent of AI is an opportunity to do just that, current uses of AI have mainly focused on drafting documentation in free-text formats, essentially replacing human scribes. Instead, we need to figure out how we can use AI to improve the usability of the resulting data. While it is not feasible to capture all data in a structured format on all patients, a core set of data are needed to provide high-quality and safe care. At a minimum, those should be structured and part of a basic core data set across disease types and health maintenance scenarios.

In order to accomplish this, NIH and the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) should fund learning laboratories that develop, pilot, and implement new approaches for data capture at the point of care. These centers would leverage advances in human-centered design and artificial intelligence (AI) to revolutionize care delivery models for different types of care settings, ranging from outpatient to acute care and intensive care settings. Ideally, these centers would be linked to existing federally funded research sites that could implement the new care and discovery processes in ongoing clinical investigations.

The federal government already spends billions of dollars on grants for clinical research- why not use some of that funding to make clinical research more efficient, and improve the experience of patients and physicians in the process?

Recommendation 3. Enable technology systems to improve data standardization and interoperability

Capturing high-quality data at the point of care is of limited utility if the data remains stuck within individual electronic health record (EHR) installations. Closed systems hinder innovation and prevent us from making the most of the amazing trove of health data.

We must create a vibrant ecosystem where health data can travel seamlessly between different systems, while maintaining patient safety and privacy. This will enable an ecosystem of health data applications to flourish. HHS has recently made progress by agreeing to a unified approach to health data exchange, but several gaps remain. To address these we must

- Increase standardization of data elements: The federal government requires certain data elements to be standardized for electronic export from the EHR. However, this list of data elements, called the United States Core Data for Interoperability (USCDI) currently does not include enough data elements for many uses of health data. HHS could rapidly expand the USCDI by working with federal partners and professional societies to determine which data elements are critical for national priorities, like vaccine safety and use, or protection from emerging pathogens.

- Enable writeback into the EHR: While current efforts focused on interoperability have focused on the ability to export EHR data, developing a vibrant ecosystem of health data applications that are available to patients, physicians, and other data users, requires the capability to write data back into the EHR. This would enable the development of a competitive ecosystem of applications that use health data generated in the EHR, much like the app store on our phones.

- Create widespread interoperability of data for multiple purposes: HHS has made great progress towards allowing health data to be exchanged between any two entities in our healthcare system, thanks to the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA). TEFCA could allow any two healthcare sites to exchange data, but unfortunately, participation remains spotty and TEFCA currently does not allow data exchange solely for research. HHS should work to close these gaps by allowing TEFCA to be used for research, and incentivizing participation in TEFCA, for example by making joining TEFCA a condition of participation in Medicare.

Conclusion

The treasure trove of health data generated during routine care has given us a huge opportunity to generate knowledge and improve health outcomes. These data should serve as a shared resource for clinical trials, registries, decision support, and outcome tracking to improve the quality of care. This is necessary for society to advance towards personalized medicine, where treatments are tailored to biology and patient preference. However, to make the most of these data, we must improve how we capture and exchange these data at the point of care.

Essential to this goal is evolving our current payment systems from rewarding documentation of complexity or time spent, to generation of data that supports learning and improvement. HHS should use its payment authorities to encourage data generation at the point of care and promote the tools that enable health data to flow seamlessly between systems, building on the success stories of existing programs like coverage with evidence development. To allow capture of this data without making the lives of providers and patients even more difficult, federal funding bodies need to invest in developing technologies and workflows that leverage AI to create usable data at the point of care. Finally, HHS must continue improving the standards that allow health data to travel seamlessly between systems. This is essential for creating a vibrant ecosystem of applications that leverage the benefits of AI to improve care.

This memo produced as part of the Federation of American Scientists and Good Science Project sprint. Find more ideas at Good Science Project x FAS

Confirming Hope: Validating Surrogate Endpoints to Support FDA Drug Approval Using an Inter-Agency Approach

To enable more timely access to new drugs and biologics, clinical trials are increasingly using surrogate markers in lieu of traditional clinical outcomes that directly measure how patients feel, function, or survive. Surrogate markers, such as imaging findings or laboratory measurements, are expected to predict clinical outcomes of interest. In comparison to clinical outcomes, surrogate markers offer an advantage in reducing the duration, size, and total cost of trials. Surrogate endpoints are considered to be “validated” if they have undergone extensive testing that confirms their ability to predict a clinical outcome. However, reviews of “validated” surrogate markers used as primary endpoints in trials supporting U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals suggest that many lack sufficient evidence of being associated with a clinical outcome.

Since 2018, FDA has regularly updated the publicly available “Table of Surrogate Endpoints That Were the Basis of Drug Approval or Licensure”, which includes over 200 surrogate markers that have been or would be accepted by the agency to support approval of a drug or biologic. Not included within the table is information regarding the strength of evidence for each surrogate marker and its association with a clinical outcome. As surrogate markers are increasingly being accepted by FDA to support approval of new drugs and biologics, it is imperative that patients and clinicians understand whether such novel endpoints are reflective of meaningful clinical benefits. Thus, FDA, in collaboration with other agencies, should take steps to increase transparency regarding the strength of evidence for surrogate endpoints used to support product approvals, routinely reassess the evidence behind such endpoints to continue justifying their use in regulatory decision-making, and sunset those that fail to show association with meaningful clinical outcomes. Such transparency would not only benefit the public, clinicians, and the payers responsible for coverage decisions, but also help shape the innovation landscape for drug developers to design clinical trials that assess endpoints truly reflective of clinical efficacy.

Challenge and Opportunity

To receive regulatory approval by FDA, new therapeutics are generally required to be supported by “substantial evidence of effectiveness” from two or more “adequate and well-controlled” pivotal trials. However, FDA has maintained a flexible interpretation of this guidance to enable timely access to new treatments. New drugs and biologics can be approved for specific disease indications based on pivotal trials measuring clinical outcomes (how patients feel, function, or survive). They can also be approved based on pivotal trials measuring surrogate markers that are meant to be proxy measures and expected to predict clinical outcomes. Examples of such endpoints include changes in tumor size as seen on imaging or blood laboratory tests such as cholesterol.

Surrogate markers are considered “validated” when sufficient evidence demonstrates that the endpoint reliably predicts clinical benefit. Such validated surrogate markers are typically the basis of traditional FDA therapeutics approval. However, FDA has also accepted the use of “unvalidated” surrogate endpoints that are reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit as the basis of approval of new therapeutics, particularly if they are being used to treat or prevent a serious or life-threatening disease. Under expedited review pathways, such as accelerated approval that grant drug manufacturers faster FDA market authorization using unvalidated surrogate markers, manufacturers are required to complete an additional clinical trial after approval to confirm the predicted clinical benefit. Should the manufacturer fail to do so, FDA has the authority to withdraw that drug’s particular indication approval.

For drug developers, the use of surrogate markers in clinical trials can shorten the duration, size, and total cost of the pivotal trial. Over time, FDA has increasingly allowed for surrogate markers to be used as primary endpoints in pivotal trials, allowing for shorter clinical trial testing periods and thus faster market access. Moreover, use of unvalidated surrogate markers has grown outside of expedited review pathways such as accelerated approval. One analysis of FDA approved drugs and biologics that received “breakthrough therapy designation” found that among those that received traditional approval, over half were based on pivotal trials using surrogate markers.

While basing FDA approval on surrogate markers can enable more timely market access to novel therapeutics, such endpoints also involve certain trade-offs, including the risk of making erroneous inferences and diminishing certainty about the medical product’s long-term clinical effect. In oncology, evidence suggests that most validation studies of surrogate markers find low correlations with meaningful clinical outcomes such as overall survival or a patient’s quality of life. For instance, in a review of 15 surrogate validation studies conducted by the FDA for oncologic drugs, only one was found to demonstrate a strong correlation between surrogate markers and overall survival. Another study suggested that there are weak or missing correlations between surrogate markers for solid tumors and overall survival. A more recent evaluation found that most surrogate markers used as primary endpoints in clinical trials to support FDA approval of drugs treating non-oncologic chronic disease lack high-strength evidence of associations with clinical outcomes.

Section 3011 of the 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 amended the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to mandate FDA publish a list of “surrogate endpoints which were the basis of approval or licensure (as applicable) of a drug or biological product” under both accelerated and traditional approval pathways. While FDA has posted surrogate endpoint tables for adult and pediatric disease indications that fulfil this legislative requirement, missing within these tables is any justification for surrogate selection, including evidence supporting validation. Without this information, patients, prescribers, and payers are left uncertain about the actual clinical benefit of therapeutics approved by the FDA based on surrogate markers. Instead, drug developers have continued to use this table as a guide in designing their clinical trials, viewing the included surrogate markers as “accepted” by the FDA regardless of the evidence (or lack thereof) undergirding them.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. FDA should make more transparent the strength of evidence of surrogate markers included within the “Adult Surrogate Endpoint Table” as well as the “Pediatric Surrogate Endpoint Table.”

Previously, agency officials stated that the use of surrogate markers to support traditional approvals was usually based, at a minimum, on evidence from meta-analyses of clinical trials demonstrating an association between surrogate markers and clinical outcomes for validation. However, more recently, FDA officials have indicated that they consider a “range of sources, including mechanistic evidence that the [surrogate marker] is on the causal pathway of disease, nonclinical models, epidemiologic data, and clinical trial data, including data from the FDA’s own analyses of patient- and trial-level data to determine the quantitative association between the effect of treatment on the [surrogate marker] and the clinical outcomes.” Nevertheless, what specific evidence and how the agency weighed such evidence is not included as part of their published tables of surrogate endpoints, leaving unclear to drug developers as well as patients, clinicians, and payers the strength of the evidence behind such endpoints. Thus, this serves as an opportunity for the agency to enhance their transparency and communication with the public.

FDA should issue a guidance document detailing their current thinking about how surrogate markers should be validated and evaluated on an ongoing basis. Within the guidance, the agency could detail the types of evidence that would be considered to establish surrogacy.

FDA should also include within the tables of surrogate endpoints, a summary of evidence for each surrogate marker listed. This would provide justification (through citations to relevant articles or internal analyses) so that all stakeholders understand the evidence establishing surrogacy. Moreover, FDA can clearly indicate within the tables which clinical outcomes each surrogate marker listed is thought to predict.

FDA should also publicly report on an annual basis a list of therapeutics approved by the agency based on clinical trials using surrogate markers as primary endpoints. This coupled with the additional information around strength of evidence for each surrogate marker would allow patients and clinicians to make more informed decisions around treatments where there may be uncertainty of the therapeutic’s clinical benefit at the time of FDA approval.

Recently, FDA’s Oncology Center for Excellent through Project Confirm has made additional efforts to communicate that status of required postmarketing studies meant to confirm clinical benefit of drugs for oncologic disease indications that received accelerated approval. FDA could further expand this across therapeutic areas and approval pathways by publishing a list of ongoing postmarketing studies for therapeutics where approval was based on surrogate markers that are intended to confirm clinical benefit.

FDA should also regularly convene advisory committees to allow for independent experts to review and vote on recommendations around the use of new surrogate markers for disease indications. Additionally, FDA should regularly convene these advisory committees to re-evaluate the use of surrogate markers based on current evidence, especially those not supported by high-strength evidence demonstrating their association with clinical outcomes. At a minimum, FDA should convene such advisory committees focused on re-examining surrogate markers listed on their publicly available tables annually. In 2024, FDA convened the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee to discuss the use of the surrogate marker, minimal residual disease as an endpoint for multiple myeloma. Further such meetings including for those “unvalidated” endpoints would provide FDA opportunity to re-examine their use in regulatory decision-making.

Recommendation 2. In collaboration with the FDA, other federal research agencies should contribute evidence generation to determine whether surrogate markers are appropriate for use in regulatory decision-making, including approval of new therapeutic products and indications for use.