Protecting Infant Nutrition Security:

Shifting the Paradigm on Breastfeeding to Build a Healthier Future for all Americans

The health and wellbeing of American babies have been put at risk in recent years, and we can do better. Recent events have revealed deep vulnerabilities in our nation’s infant nutritional security. For example: Pandemic-induced disruptions in maternity care practices that support the establishment of breastfeeding; the infant formula recall and resulting shortage; and a spate of weather-related natural disasters have demonstrated infrastructure gaps and a lack of resilience to safety and supply chain challenges. All put babies in danger during times of crisis.

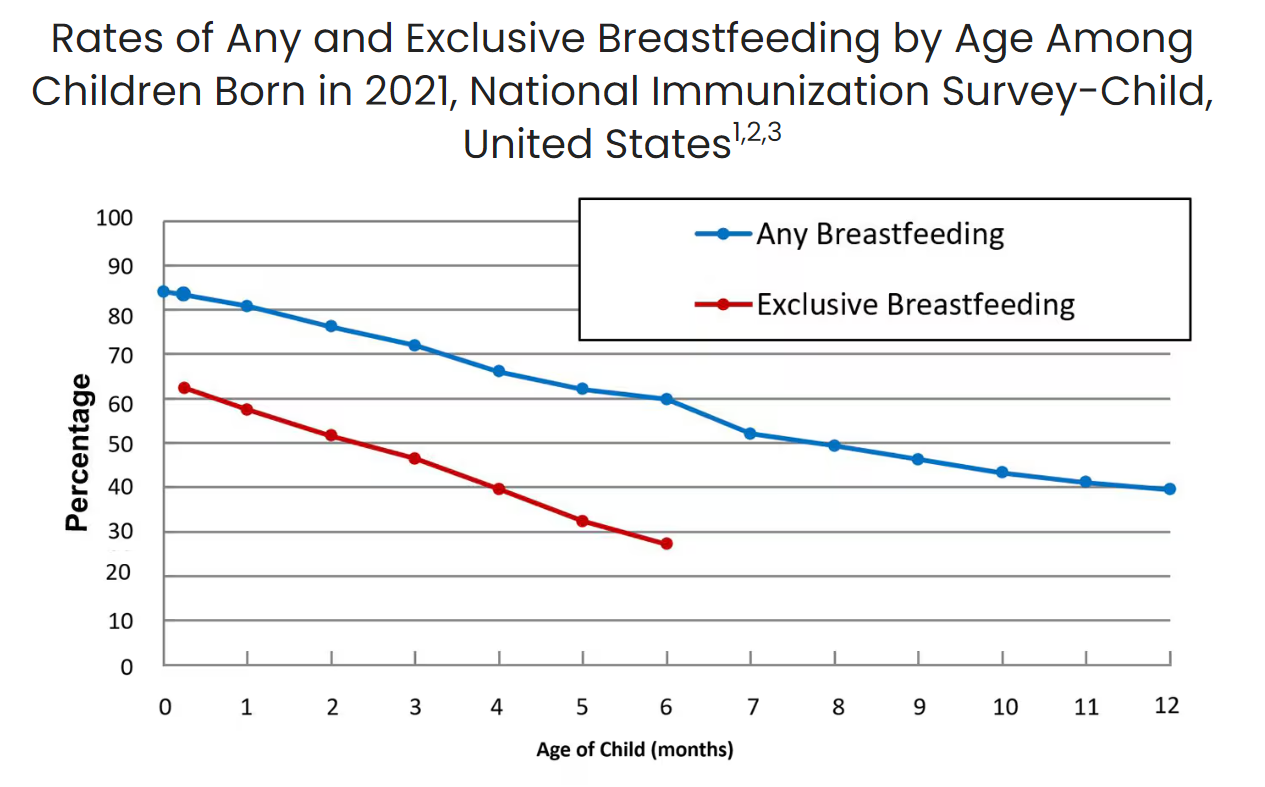

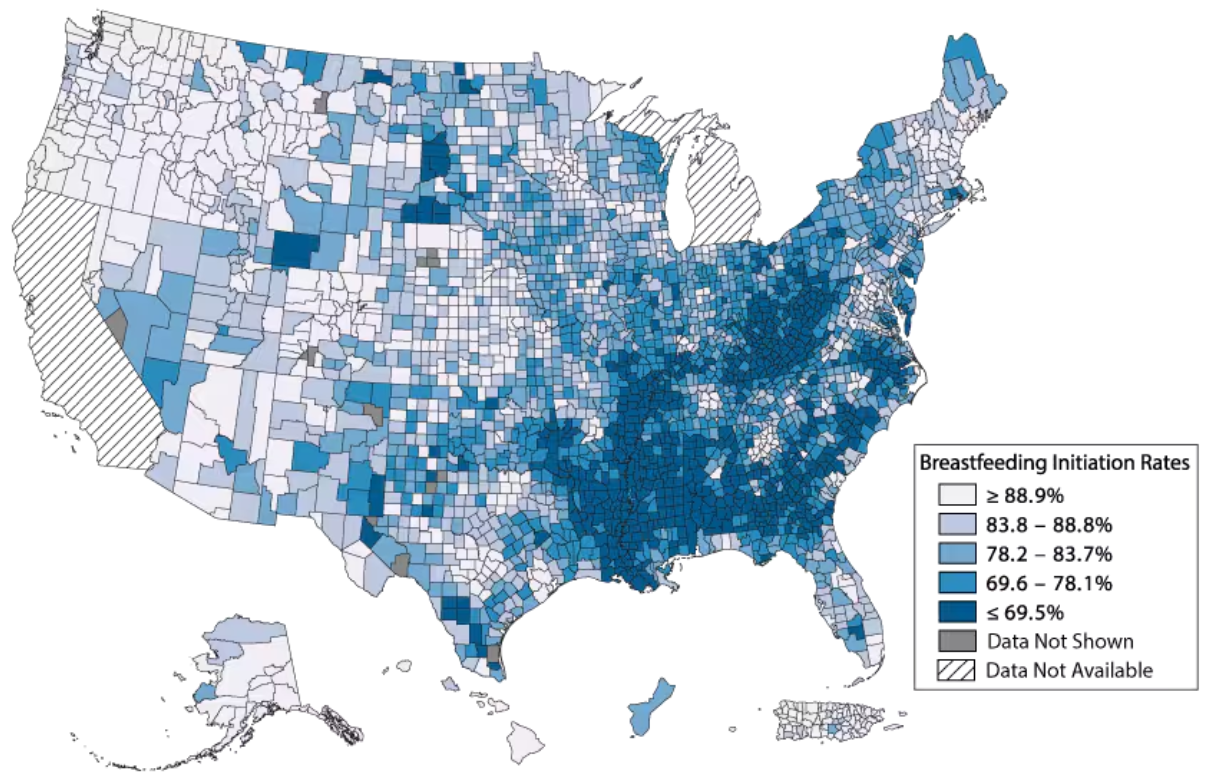

Breastfeeding is foundational to lifelong health and wellness, but systemic barriers prevent many families from meeting their breastfeeding goals. The policies and infrastructure surrounding postpartum families often limit their ability to succeed in breastfeeding. Despite important benefits, new data from the CDC shows that while 84.1% of infants start out breastfeeding, these numbers fall dramatically in the weeks after birth, with only 57.5% of infants breastfeeding exclusively at one month of age. Disparities persist across geographic location, and other sociodemographic factors, including race/ethnicity, maternal age, and education. Breastfeeding rates in North America are the lowest in the world. Longstanding evidence shows that it is not a lack of desire but rather a lack of support, access, and resources that creates these barriers.

This administration has an opportunity to take a systems approach to increasing support for breastfeeding and making parenting easier for new mothers. Key policy changes to address systemic barriers include providing guidance to states on expanding Medicaid coverage of donor milk, building breastfeeding support and protection into the existing emergency response framework at the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and expressing support for establishing a national paid leave program.

Policymakers on both sides of the aisle agree that no baby should ever go hungry, as evidenced by the bipartisan passage of recent breastfeeding legislation (detailed below) and widely supported regulations. However, significant barriers remain. This administration has the power to address long-standing inequities and set the stage for the next generation of parents and infants to thrive. Ensuring that every family has the support they need to make the best decisions for their child’s health and wellness benefits the individual, the family, the community, and the economy.

Challenge and Opportunity

Breastfeeding plays an essential role in establishing good nutrition and healthy weight, reducing the risk of chronic disease and infant mortality, and improving maternal and infant health outcomes. Breastfed children have a decreased risk of obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes, asthma, and childhood leukemia. Women who breastfeed reduce their risk of specific chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and breast and ovarian cancers. On a relational level, the hormones produced while breastfeeding, like oxytocin, enhance the maternal-infant bond and emotional well-being. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends infants be exclusively breastfed for approximately six months with continued breastfeeding while introducing complementary foods for two years or as long as mutually desired by the mother and child.

Despite the well-documented health benefits of breastfeeding, deep inequities in healthcare, community, and employment settings impede success. Systemic barriers disproportionately impact Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color, as well as families in rural and economically distressed areas. These populations already bear the weight of numerous health inequities, including limited access to nutritious foods and higher rates of chronic disease—issues that breastfeeding could help mitigate.

Breastfeeding Saves Dollars and Makes Sense

Low breastfeeding rates in the United States cost our nation millions of dollars through higher health system costs, lost productivity, and higher household expenditures. Not breastfeeding is associated with economic losses of about $302 billion annually or 0.49% of world gross national income. At the national level, improving breastfeeding practices through programs and policies is one of the best investments a country can make, as every dollar invested is estimated to result in a $35 economic return.

In the United States, chronic disease management results in trillions of dollars in annual healthcare costs, which increased breastfeeding rates could help reduce. In the workplace setting, employers see significant cost savings when their workers are able to maintain breastfeeding after returning to work. Increased breastfeeding rates are also associated with reduced environmental impact and associated expenses. Savings can be seen at home as well, as following optimal breastfeeding practices reduces household expenditures. Investments in infant nutrition last a lifetime, paying long-term dividends critical for economic and human development. Economists have completed cost-benefit analyses, finding that investments in nutrition are one of the best value-for-money development actions, laying the groundwork for the success of investments in other sectors.

Ongoing trends in breastfeeding outcomes indicate that there are entrenched policy-level challenges and barriers that need to be addressed to ensure that all infants have an opportunity to benefit from access to human milk. Currently, for too many families, the odds are stacked against them. It’s not a question of individual choice but one of systemic injustice. Families are often forced into feeding decisions that do not reflect their true desires due to a lack of accessible resources, support, and infrastructure.

While the current landscape is rife with challenges, the solutions are known and the potential benefits are tremendous. This administration has the opportunity to realize these benefits and implement a smart and strategic response to the urgent situation that our nation is facing just as the political will is at an all-time high.

The History of Breastfeeding Policy

In the late 1960s and early 1970s less than 30 percent of infants were breastfed. The concerted efforts of individuals and organizations and the emergence of the field of lactation have worked to counteract or remove many barriers, and policymakers have sent a clear and consistent message that breastfeeding is bipartisan. This is evident in the range of recent lactation-friendly legislation, including:

- Bottles and Breastfeeding Equipment Screening Act (BABES Act) in 2016

- Friendly Airports for Mothers (FAM) Act in 2018

- Fairness for Breastfeeding Mothers Act in 2019

- Providing Urgent Maternal Protections (PUMP) for Nursing Mothers Act in 2022

Administrative efforts ranging from the Business Case for Breastfeeding to The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding and the armed services updates on uniform requirements for lactating soldiers demonstrate a clear commitment to breastfeeding support across the decades.

These policy changes have made a difference. But additional attention and investment, with a particular focus on the birth and early postpartum period, as well as during and after emergencies, is needed to secure the potential health and economic benefits of comprehensive societal support for breastfeeding. This administration can take considerable steps toward improving U.S. health and wellness and protecting infant nutrition security.

Plan of Action

A range of federal agencies coordinate programs, services, and initiatives impacting the breastfeeding journey for new parents. Expanding and building on existing efforts through the following steps can help address some of today’s most pressing barriers to breastfeeding.

Each of the recommended actions can be implemented independently and would create meaningful, incremental change for families. However, a comprehensive approach that implements all these recommendations would create the marked shift in the landscape needed to improve breastfeeding initiation and duration rates and establish this administration as a champion for breastfeeding families.

Recommendation 1. Increase access to pasteurized donor human milk by directing the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to provide guidance to states on expanding Medicaid coverage.

Pasteurized donor human milk is lifesaving for vulnerable infants, particularly those born preterm or with serious health complications. Across the United States, milk banks gently pasteurize donated human milk and distribute it to fragile infants in need. This lifesaving liquid gold reduces mortality rates, lowers healthcare costs, and shortens hospital stays. Specifically, the use of donor milk is associated with increased survival rates and lowered rates of infections, sepsis, serious lung disease, and gastrointestinal complications. In 2022, there were 380,548 preterm births in the United States, representing 10.4% of live births, so the potential for health and cost savings is substantial. Data from one study shows that the cost of a neonatal intensive care unit stay for infants at very low birth weight is nearly $220,000 for 56 days. The use of donor human milk can reduce hospital length of stay by 18-50 days by preventing the development of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. The benefits of human milk extend beyond the inpatient stay, with infants receiving all human milk diets in the NICU experiencing fewer hospital readmissions and better overall long-term outcomes.

Although donor milk has important health implications for vulnerable infants in all communities and can result in significant economic benefit, donor milk is not equitably accessible. While milk banks serve all states, not all communities have easy access to donated human milk. Moreover, many insurers are not required to cover the cost, creating significant barriers to access and contributing to racial and geographic disparities.

To ensure that more babies in need have access to lifesaving donor milk, the administration should work with CMS to expand donor milk coverage under state Medicaid programs. Medicaid covers approximately 40% of all US births and 50% of all early preterm births. Medicaid programs in at least 17 states and the District of Columbia already include coverage of donor milk. The administration can expand access to this precious milk, help reduce health care costs, and address racial and geographic disparities by releasing guidance for the remaining states regarding coverage options in Medicaid.

Recommendation 2. Include infant feeding in Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) emergency planning and response.

Infants and children are among the most vulnerable in an emergency, so it is critical that their unique needs are considered and included in emergency planning and response guidance. Breastfeeding provides clean, optimal nutrition, requires no fuel, water, or electricity, and is available, even in the direst circumstances. Human milk contains antibodies that fight infection, including diarrhea and respiratory infections common among infants in emergency situations. Yet efforts to protect infant and young child feeding in emergencies are sorely lacking, particularly in the immediate aftermath of disasters and emergencies.

Ensuring access to lactation support and supplies as part of emergency response efforts is essential for protecting the health and safety of infants. Active support and coordination between federal, state, and local governments, the commercial milk formula industry, lactation support providers, and all other relevant actors involved in response to emergencies is needed to ensure safe infant and young child feeding practices and equitable access to support. There are two simple, cost-effective steps that FEMA can take to protect breastfeeding, preserve resources, and thus save additional lives during emergencies.

- Require FEMA to participate in the Federal Interagency Breastfeeding Workgroup, a collection of federal agencies that come together to connect and collaborate on breastfeeding issues, to ensure coordination across agencies.

- Update the FEMA Public Assistance Program and Policy Guide (PAPPG) to include breastfeeding and lactation as a functional need in the section on Congregate Shelter Services so that emergency response efforts can include services from lactation support providers and be reimbursed for the associated costs.

Recommendation 3. Expand access to paid family & medical leave by including paid leave as a priority in the President’s Budget and supporting the efforts of the bipartisan, bicameral congressional Paid Leave Working Group.

Employment policies in the United States make breastfeeding harder than it needs to be. The United States is one of the only countries in the world without a national paid family and medical leave program. Many parents return to work quickly after birth, before a strong breastfeeding relationship is established, because they cannot afford to take unpaid leave or because they do not qualify for paid leave programs with their employer or through state or local programs. Nearly 1 in 4 employed mothers return to work within two weeks of childbirth.

Paid family leave programs make it possible for employees to take time for childbirth recovery, bond with their baby, establish feeding routines, and adjust to life with a new child without threatening their family’s economic well-being. This precious time provides the foundation for success, contributing to improved rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration, yet only a small portion of workers are able to access it. There are significant disparities in access to paid leave among racial and ethnic groups, with Black and Hispanic employees less likely than their white non-Hispanic counterparts to have access to paid parental leave. There are similar disparities in breastfeeding outcomes among racial groups.

The momentum is building substantially to improve the paid family and medical leave landscape in the United States. Thirteen states and the District of Columbia have established mandatory state paid family leave systems. Supporting paid leave has become an important component of candidate campaign plans, and bipartisan support for establishing a national program remains strong among voters. The formation of Bipartisan Paid Family Leave Working Groups in both the House and Senate demonstrate commitment from policymakers on both sides of the aisle.

By directing the Office of Management and Budget to include funding for paid leave in the President’s Budget recommendation and working collaboratively with the Congressional Paid Leave Working Groups, the administration can advance federal efforts to increase access to paid family and medical leave, improving public health and helping American businesses.

Conclusion

These three strategies offer the opportunity for the White House to make an immediate and lasting impact by protecting infant nutrition security and addressing disparities in breastfeeding rates, on day one of the Presidential term. A systems approach that utilizes multiple strategies for integrating breastfeeding into existing programs and efforts would help shift the paradigm for new families by addressing long-standing barriers that disproportionately affect marginalized communities—particularly Black, Indigenous, and families of color. A clear and concerted effort from the Administration, as outlined, offers the opportunity to benefit all families and future generations of American babies.

The administration’s focused and strategic efforts will create a healthier, more supportive world for babies, families, and breastfeeding parents, improve maternal and child health outcomes, and strengthen the economy. This administration has the chance to positively shape the future for generations of American families, ensuring that every baby gets the best possible start in life and that every parent feels empowered and supported.

Now is the time to build on recent momentum and create a world where families have true autonomy in infant feeding decisions. A world where paid family leave allows parents the time to heal, bond, and establish feeding routines; communities provide equitable access to donor milk; and federal, state, and local agencies have formal plans to protect infant feeding during emergencies, ensuring no baby is left vulnerable. Every family deserves to feel empowered and supported in making the best choices for their children, with equitable access to resources and support systems.

This policy memo was written with support from Suzan Ajlouni, Public Health Writing Specialist at the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee. The policy recommendations have been identified through the collective learning, idea sharing, and expertise of USBC members and partners.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Rather than being a matter of personal choice, infant feeding practice is informed by circumstance and level (or lack) of support. When roadblocks exist at every turn, families are backed into a decision because the alternatives are not available, attainable, or viable. United States policies and infrastructure were not built with the realities of breastfeeding in mind. Change is needed to ensure that all who choose to breastfeed are able to meet their personal breastfeeding goals, and society at large reaps the beneficial social and economic outcomes.

The Fiscal Year 2024 President’s Budget proposed to establish a national, comprehensive paid family and medical leave program, providing up to 12 weeks of leave to allow eligible workers to take time off to care for and bond with a new child; care for a seriously ill loved one; heal from their own serious illness; address circumstances arising from a loved one’s military deployment; or find safety from domestic violence, sexual assault, or stalking. The budget recommendation included $325 billion for this program. It’s important to look at this with the return on investment in mind, including improved labor force attachment and increased earnings for women; better outcomes and reduced health care costs for ill, injured, or disabled loved ones; savings to other tax-funded programs, including Medicaid, SNAP, and other forms of public assistance; and national economic growth, jobs growth, and increased economic activity.

There are a variety of national monitoring and surveillance efforts tracking breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity rates that will inform how well these actions are working for the American people, including the National Immunization Survey (NIS), Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System (PRAMS), Infant Feeding Practices Study, and National Vital Statistics System. The CDC Breastfeeding Report card is published biannually to bring these key data points together and place them into context. Significant improvements in the data have already been seen across recent decades, with breastfeeding initiation rates increasing from 73.1 percent in 2004 to 84.1 percent in 2021.

The U.S. Breastfeeding Committee is a coalition bringing together approximately 140 organizations from coast to coast representing the grassroots to the treetops – including federal agencies, national, state, tribal, and territorial organizations, and for-profit businesses – that support the USBC mission to create a landscape of breastfeeding support across the United States. Nationwide, a network of hundreds of thousands of grassroots advocates from across the political spectrum support efforts like these. Together, we are committed to ensuring that all families in the U.S. have the support, resources, and accommodations to achieve their breastfeeding goals in the communities where they live, learn, work, and play. The U.S. Breastfeeding Committee and our network stand ready to work with the administration to advance this plan of action.

Clearing the Path for New Uses for Generic Drugs

The labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA pathway for non-manufacturers to seek FDA approval

Repurposing generic drugs as new treatments for life-threatening diseases is an exciting yet largely overlooked opportunity due to a lack of market-driven incentives. The low profit margins for generic drugs mean that pharmaceutical companies rarely invest in research, regulatory efforts, and marketing for new uses. Nonprofit organizations and other non-commercial non-manufacturers are increasing efforts to repurpose widely available generic drugs and rapidly expand affordable treatment options for patients. However, these non-manufacturers find it difficult to obtain regulatory approval in the U.S. They face significant challenges in using the existing approval pathways, specifically in: 1) providing the FDA with required chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) data, 2) providing the FDA with product samples, and 3) conducting post-marketing surveillance. Without a straightforward path for approval and updating drug labeling, non-manufacturers have relied on off-label use of repurposed drugs to drive uptake. This practice results in outdated labeling for generics and hinders widespread clinical adoption, limiting patient access to these potentially life-saving treatments.

To encourage greater adoption of generic drugs in clinical practice – that is, to encourage the repurposing of these drugs – the FDA should implement a dedicated regulatory pathway for non-manufacturers to seek approval of new indications for repurposed generic drugs. A potential solution is an extension of the existing 505(b)(2) new drug application (NDA) approval pathway. This extension, the “labeling-only” 505(b)(2) NDA, would be a dedicated pathway for non-manufacturers to seek FDA approval of new indications for well-established small molecule drugs when multiple generic products are already available. The labeling-only 505(b)(2) pathway would be applicable for repurposing drugs for any disease. Creating a regulatory pathway for non-manufacturers would unlock access to innovative therapies and enable the public to benefit from the enormous potential of low-cost generic drugs.

Challenge and Opportunity

The opportunity for generic drug repurposing

On-patent, branded drugs are often unaffordable for Americans. Due to the high cost of care, 42% of patients in the U.S. exhaust their life savings within two years of a cancer diagnosis. Generic drug repurposing – the process of finding new uses for FDA-approved generic drugs – is a major opportunity to quickly create low-cost and accessible treatment options for many diseases. In oncology, hundreds of generic drugs approved for non-cancer uses have been tested as cancer treatments in published preclinical and clinical studies.

The untapped potential for generic drug repurposing in cancer and other diseases is not being realized because of the lack of market incentives. Pharmaceutical companies are primarily focused on de novo drug development to create new molecular and chemical entities. Typically, pharmaceutical companies will invest in repurposing only when the drugs are protected by patents or statutory market exclusivities, or when modification to the drugs can create new patent protection or exclusivities (e.g., through new formulations, dosage forms, or routes of administration). Once patents and exclusivities expire, the introduction of generic drugs creates competition in the marketplace. Generics can be up to 80-85% less expensive than their branded counterparts, driving down overall drug prices. The steep decline in prices means that pharmaceutical companies have little motivation to invest in research and marketing for new uses of off-patent drugs, and this loss of interest often starts in the years preceding generic entry.

In theory, pharmaceutical companies could repurpose generics without changing the drugs and apply for method-of-use patents, which should provide exclusivity for new indications and the potential for higher pricing. However, due to substitution of generic drugs at the pharmacy level, method-of-use patents are of little to no practical value when there are already therapeutically equivalent products on the market. Pharmacists can dispense a generic version instead of the patent-protected drug product, even if the substituted generic does not have the specific indication in its labeling. Currently, nearly all U.S. states permit substitution by the pharmacy, and over a third have regulations that require generic substitution when available.

Nonprofits like Reboot Rx and other non-commercial non-manufacturers are therefore stepping in to advance the use of repurposed generic drugs across many diseases. Non-manufacturers, which do not manufacture or distribute drugs, aim to ensure there is substantial evidence for new indications of generic drugs and then advocate for their clinical use. Regulatory approval would accelerate adoption. However, even with substantial evidence to support regulatory review, non-manufacturers find it difficult or impossible to seek approval for new indications of generic drugs. There is no straightforward pathway to do so within the current U.S. regulatory framework without offering a specific, manufactured version of the drug. This challenge is not unique to the U.S.; recent efforts in the European Union (EU) have sought to address the regulatory gap. In the 2023 EU reform of pharmaceutical legislation, Article 48 is currently under review by the European Parliament as a potential solution to allow nonprofit entities to spearhead submissions for the approval of new indications for authorized medicinal products with the European Medicines Agency. To maximize the patient impact of generic drugs in America, non-manufacturers should be able to drive updates to FDA drug labeling, enabling widespread clinical adoption of repurposed drugs in a formal, predictable, and systematic manner.

The importance of FDA approval

Drugs that are FDA-approved can be prescribed for any indication not listed on the product labeling, often referred to as “off-label use”. Since non-manufacturers face significant challenges pursuing regulatory approval for new indications, they often must rely on advocating for off-label use of repurposed drugs.

While off-label use is widely accepted and helpful for specific circumstances, there are significant advantages to having FDA approval of new drug indications included in labeling. FDA drug labeling is intended to contain up-to-date information about drug products and ensures that the necessary conditions of use (including dosing, warnings, and precautions) are communicated for the specific indications. It is the primary authoritative source for making informed treatment decisions and is heavily valued by the medical community. Approval may increase the likelihood of uptake by clinical guidelines, pathways systems, and healthcare payers. Indications with FDA approval may generate greater awareness of the treatment options, leading to a broader and more rapid impact on clinical practice.

Clinical practice guidelines are often the leading authority for prescribers and patients regarding off-label use. In oncology, for example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines are commonly used guidelines that include many off-label uses. However, guidelines do not exist for every disease and medical specialty, which can make it more difficult to gain acceptance for off-label uses. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) policy routinely covers off-label drug uses if they are listed in certain compendia. The NCCN Compendia, which is based on the NCCN Guidelines, is the only accepted compendium that is disease-specific.

Off-label use requires more effort from individual prescribers and patients to independently evaluate new drug data, thereby slowing uptake of the treatments. This can be especially difficult for community-based physicians, who need to remain up-to-date on new treatment options across many diseases. Off-label prescribing can also introduce medico-legal risks, such as malpractice. These burdens and risks limit off-label prescribing, even when there is supportive evidence for the new uses.

As new uses for generic drugs are discovered, it is crucial to update the labeling to ensure alignment with current clinical practice. Outdated generic drug labeling means that prescribers and patients may not have access to all the necessary information to understand the full risk-benefit profile. Americans deserve to have access to all effective treatment options – especially low-cost and widely available generic drugs that could help mitigate the financial toxicity and health inequities faced by many patients. For the public benefit, the FDA should support approaches that remove regulatory barriers for non-manufacturers and modernize drug labeling.

Existing pathways for manufacturers to obtain FDA approval

The current FDA approval system is based on the idea that sponsors have discrete physical drug products. Traditionally, sponsors seeking FDA approval are pharmaceutical companies or drug manufacturers that intend to produce (or contract for production), distribute, and sell the finished drug product. For the purposes of FDA regulation, “drug” refers to a substance intended for use in the treatment or prevention of disease; “drug product” is the final dosage form that contains a drug substance and inactive ingredients made and sold by a specific manufacturer. One drug can be present on the market in multiple drug products. In the current regulatory framework, drug products are approved through one of the following:

- 505(b)(1) NDA: New drug products, including new molecular entities, are first submitted for FDA review through the 505(b)(1) new drug application (NDA) pathway. In this pathway, the sponsor either generates all necessary clinical data or owns the right of reference to the clinical data needed to support the NDA. FDA approval of an NDA establishes a reference listed drug (RLD), based on the FDA’s determinations of safety and effectiveness for the drug.

- 505(b)(2) NDA: For new drug products or formulations utilizing or related to previously approved drugs or drug substances, the 505(b)(2) NDA pathway offers a streamlined alternative to the 505(b)(1) NDA. By allowing the sponsor to reference the FDA’s findings of safety and effectiveness for previously approved drugs and published literature, the sponsor can submit data they do not own or for which they do not have the right of reference, once any exclusivities expire.

- ANDA: Generic drug equivalents are approved through the 505(j) abbreviated NDA (ANDA) pathway. The RLD serves as the standard that other manufacturers may reference when seeking approval for generic versions of the drug. Upon approval, ANDA products receive a therapeutic equivalence designation in the FDA’s Orange Book, indicating the generic drug products are interchangeable for and substitutable with the RLD.

- BLA: Biological products are approved through the biologics license application (BLA). There is currently no provision analogous to section 505(b)(2) under the law governing the approval of biological products. While the FDA is authorized to approve biosimilars, including interchangeable biosimilars akin to generics, no current pathway permits the addition of new indications for use to a biosimilar product short of submitting a complete, original BLA with full preclinical and clinical data. Our proposed regulatory pathway is relevant for small molecule drugs and would not be applicable to biological products under current law.

Manufacturers can add new indications to their approved labeling without modifying the drug product through existing pathways. With supportive clinical evidence for the new indication, the NDA holder can file a supplemental NDA (sNDA), while an ANDA holder may submit a 505(b)(2) NDA as a supplement to their existing ANDA. As previously discussed, the drug product will likely be subject to pharmacy-level substitution with any available therapeutically equivalent generic. The marketing exclusivities that sponsors may receive from the FDA do not protect against this substitution. Therefore, these pathways are rarely, if ever, used by pharmaceutical companies when there are already multiple generic manufacturers of the product.

Challenges for non-manufacturers in using existing pathways

Since manufacturers are not incentivized to seek regulatory approval for new indications, labeling changes are more likely to happen if driven by non-manufacturers. Yet non-manufacturers face significant challenges in utilizing the existing regulatory pathways. Sponsors must submit the following information for all NDAs for the FDA’s review: 1) clinical and nonclinical data on the safety and effectiveness of the drug for the proposed indication; 2) the proposed labeling; and 3) chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) data describing the methods of manufacturing and the controls to maintain the drug product’s quality.

To submit and maintain NDAs, non-manufacturer sponsors would need to address the following challenges:

- Providing the FDA with required CMC data. NDA sponsors must provide CMC data for FDA review. Non-manufacturers would not produce physical drug products, and therefore they would not have information on the manufacturing process.

- Providing the FDA with product samples. If requested, NDA sponsors must have the drug products and other samples (e.g., drug substances or reference standards) available to support the FDA review process and must make available for inspection the facilities where the drug substances and drug products are manufactured. Non-manufacturers would not have physical drug products to provide as samples, the capabilities to produce them, or access to the facilities where they are made.

- Conducting post-marketing surveillance. Post-marketing responsibilities to maintain an NDA include conducting annual safety reporting and maintaining a toll-free number for the public to call with questions or concerns. Non-manufacturers, such as small nonprofits, may not have the bandwidth or resources to meet these requirements.

Within the current statutory framework, a non-manufacturer could sponsor a 505(b)(2) NDA to obtain approval of a new indication by partnering with a current manufacturer of the drug – either an NDA or ANDA holder. The manufacturer would help meet the technical requirements of the 505(b)(2) application that the non-manufacturer could not fulfill independently. Through this partnership, the non-manufacturer would acquire the CMC data and physical drug product samples from the manufacturer and rely on the manufacturer’s facilities to fulfill FDA inspection and quality requirements.

Once approved, the 505(b)(2) NDA would create a new drug product with indication-specific labeling, even though the product would be identical to an existing product under a previous NDA or ANDA. The 505(b)(2) NDA would then be tied to the specific manufacturer due to the use of their CMC data, and that manufacturer would be responsible for producing and distributing the drug product for the new indication.

As a practical matter, this pathway is rarely attainable. Manufacturers of marketed drug products, particularly generic drug manufacturers, lack the incentives needed to partner with non-manufacturers. Manufacturers may not want to provide their CMC data or samples because it may prompt FDA inspection of their facilities, require an update to their CMC information, or open the door to product liability risks. The existing incentive structure strongly discourages generic drug manufacturers from expending any additional resources on researching new uses or making any changes to their product labeling that would deviate from the original RLD product.

Plan of Action

To modernize drug labeling and enhance clinical adoption of generic drugs, the FDA should implement a dedicated regulatory pathway for non-manufacturers to seek approval of new indications for repurposed generic drugs. Ultimately, such a pathway would enable drug repurposing and be a crucial step toward equitable healthcare access for Americans. We propose a potential solution – a “labeling-only” 505(b)(2) NDA – as an extension of the existing 505(b)(2) approval pathway.

Overview of the proposed labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA pathway

The labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA would enable non-manufacturers to reference CMC information from previous FDA determinations and, when necessary, provide the FDA with samples of commercially available drug products. Through this approach, the new indication would not be tied to a specific drug product made by one manufacturer. There is no inherent necessity for a new indication of a generic drug to be exclusively linked to a single manufacturer or drug product when the FDA has already approved multiple therapeutically equivalent generic drugs. Any of these interchangeable drug products would be considered equally safe and effective for the new indication, and patients could receive any of these drug products due to pharmacy-level substitution.

We describe non-manufacturer repurposing sponsors as entities that intend to submit or reference clinical data through a labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA. This pathway is designed to expand the FDA-approved labeling of generic drugs for new indications, including those that may already be considered the standard of care. Non-manufacturers do not have the means to independently produce or distribute drug products. Instead, they intend to show that there is substantial evidence to support the new use through FDA approval, and then advocate for the indication in clinical practice. This evidence may be based on their research or research performed by other entities, including clinical trials and real-world data analyses.

The labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA pathway helps address the three major challenges non-manufacturers face in pursuing regulatory approval. Through this pathway, non-manufacturers would be able to:

- Reference the FDA’s previous determinations on CMC data. Currently, a 505(b)(2) NDA can reference the FDA’s previous determinations of safety and effectiveness for an approved drug product. For eligible generic drugs, the labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA would build on this practice by allowing non-manufacturer sponsors to reference the FDA’s previous determinations on any NDA or ANDA that the manufacturing process and CMC data are adequate to meet regulatory standards.

- Provide the FDA with product samples using commercially available drug product samples. Currently, it is up to the discretion of the FDA whether or not to request samples in the review of an application. With the labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA, non-manufacturers would provide the FDA with samples of commercially available products from generic manufacturers. Given that the FDA would have already evaluated the products and their bioequivalence to the RLD during the previous reviews, it is not expected that the FDA would need to re-examine the product at the level of requesting samples, except potentially to examine the packaging and physical presentation of the product for compatibility with the new indication and conditions of use. The facilities where the drugs are made would remain available for inspection, under the same terms and conditions as the existing, approved marketing applications.

- Manage post-marketing responsibilities. Since most post-marketing surveillance and adverse event reporting are drug product-specific, these obligations would continue to be the responsibility of the manufacturer of the physical drug product dispensed. With the labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA, the non-manufacturer would not have product-specific obligations because they are not putting a new product into the marketplace. However, we anticipate the non-manufacturer would be responsible for the repurposed indication on their labeling, including but not limited to post-marketing surveillance as well as indication-specific adverse event reporting and reasonable follow-up.

Under the labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA, the non-manufacturer sponsor would not introduce a new physical drug product into the market. The new labeling created by the approval would not expressly be associated with one specific product. The non-manufacturer’s labeling would refer to the drug by its established generic name. In that way, the non-manufacturer sponsor’s approval and labeling could be applicable to all equivalent versions of the drug product and would be available for patients to receive from their pharmacy in the same way that generic drugs are typically dispensed at the pharmacy. That is, with the benefit of pharmacy-level substitution, patients could receive any available, therapeutically equivalent drug products from any current manufacturer.

Eligibility criteria

We envision the users of this pathway to be non-manufacturers that conduct drug repurposing research for the public benefit, including organizations like nonprofits and patient advocacy groups. The FDA should implement and enforce additional guardrails on eligibility to ensure that sponsors operate in good faith and cannot otherwise meet traditional NDA requirements. This process may include pre-submission meetings and reviews. The labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA should be held to the FDA’s standard level of rigor and scrutiny of safety and effectiveness for the proposed indication during the review process.

The labeling-only 505(b)(2) would only be suitable for well-established, commercially available small molecule generic drugs, which can be identified as:

- Drugs with a U.S. Pharmacopeia and National Formulary (USP-NF) monograph. The USP-NF monograph system ensures the uniformity of available products on the market by setting a consensus minimum standard of identity, strength, quality, and purity among all marketed versions of a drug. It is expressly recognized in the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act (FDCA). The USP-NF strives to have substance and product monographs for all FDA-approved drugs. USP-NF monographs for generics are commonly available because the drugs have been on the market for a long time and are typically produced by multiple manufacturers. Drug products in the U.S. market must conform to the standards in the USP-NF, when available, to avoid possible charges of adulteration and misbranding.

By statute and regulation, the FDA already allows for NDAs and ANDAs to reference the USP-NF to satisfy some CMC requirements, such as for specifications of the drug substance. As an illustration of the acceptance of the USP-NF, clinical trial protocols requiring the use of background therapy or supportive care, as well as trials testing medical devices requiring the use of a drug product, often will specify that any available version of the drug product meeting USP-NF standards can be used. We propose that products without USP-NF monographs, including certain newer drugs and drugs with especially complicated manufacturing processes that are not conducive to standardization, would not be eligible for the labeling-only 505(b)(2) pathway.

- Drugs with multiple A-rated, therapeutically equivalent products in the FDA Orange Book. The FDA does not regulate which specific products are dispensed or substituted for a given drug prescription. The listing of therapeutic equivalents in the Orange Book facilitates the seamless replacement of drug products from different manufacturers in clinical practice. Therapeutically equivalent drug products: i) have demonstrated bioequivalence to the RLD; ii) have the same strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the RLD; and iii) are labeled for the same conditions of use as the RLD. Therapeutic equivalents that meet these criteria are designated “A-rated” in the Orange Book. A-rated drug products are substitutable for any other version of that A-rated drug product, including the RLD itself.

Implementation

The labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA pathway could be implemented through an FDA guidance document interpreting the current statute and regulations or through legislation that clarifies the FDA’s existing authority. Guidance documents contain the FDA’s interpretation of a given policy on regulatory issues. The FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) could issue new guidance that allows for interpretation of the existing statute, thereby officially authorizing previous FDA determinations of acceptable CMC data to be referenceable for eligible generic drugs and adjusting drug sample requirements. Alternatively, the labeling-only 505(b)(2) could be enacted by Congress through a statutory change by incorporation into FDCA, which is up for reauthorization through the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) in 2027, or other congressional acts as appropriate. FDA guidance would be a faster pathway to adoption, while statutory authorization would offer additional safeguards for the continuance of the pathway long term.

The labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA pathway could be funded through user fees, which are established by PDUFA for the cost to file and maintain NDAs. However, many nonprofit sponsors would not be able to afford the same user fees as for-profit pharmaceutical manufacturers. Relevant statutes will likely need to be updated to create a different fee schema for non-manufacturers who use the labeling-only 505(b)(2) pathway. In a similar spirit to reducing barriers to maintaining up-to-date labeling, the 2017 PDUFA update waived the fee for submitting an sNDA, which is how an existing RLD holder would update their labeling with new indication information.

Conclusion

Patients need new and affordable treatment options for diseases that have a devastating societal impact, and repurposing generic drugs can help address this need. Nonprofits and other non-manufacturers are driving these efforts forward due to a lack of interest from pharmaceutical companies. As momentum gains for generic drug repurposing, the U.S. regulatory system needs a pathway for non-manufacturers to seek FDA approval of new indications for existing generic drugs. Our proposed labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA would eliminate undue administrative burden, enabling non-manufacturers to pursue FDA approval of new indications. It would allow the FDA to provide the public with the most up-to-date drug labeling, improving the ability of patients and physicians to make informed treatment decisions. This dedicated pathway would increase the availability of effective treatment options while reducing costs for the American healthcare system.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

The FDA does not have sufficient bandwidth or resources to meet the opportunity we have with repurposed generic drugs. To be the primary driver of labeling changes for repurposed generic drugs, the FDA would need to identify repurposing opportunities and also thoroughly compile and evaluate the safety and effectiveness data for the new indications. Project Renewal in FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence is working with RLD holders to update the labeling of certain older oncology drugs where the outdated labeling does not reflect their current clinical use. The initial focus of Project Renewal is limited, and newly repurposed treatments are not included within its scope. For newly repurposed treatments, the FDA could evaluate the drugs and post to the Federal Register reports on their safety and effectiveness that could be referenced by manufacturers. However, this approach is burdensome as it would require a significant commitment of FDA resources. By introducing a motivated, third-party non-manufacturer as the primary driver for labeling changes, non-manufacturers can contribute expertise and resources to enable faster data evaluation for more drugs.

The pre-existing NDA sponsor could update their labeling to add the new indication through an sNDA that references the labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA. ANDA holders would then be legally required to match their labeling to that of the RLD. The FDA should determine whether all current manufacturers would be required to update their labeling following approval of the new indication, and if so, the appropriate process.

Generic drugs play a vital role in the U.S. healthcare system by decreasing drug spending and increasing the accessibility of essential medicines. Generics account for 91% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. Expanding the market with generics for new indications could lead to short-term price increases above the inflation rate for off-patent branded and generic drugs in some unlikely circumstances. For example, if a new use for a generic drug substantially increases demand for the drug, there is a short-term risk that prices for the drug or potential substitutes could rise until manufacturers build more capacity to increase supply. To mitigate this risk, generic manufacturers could be notified about potential increases in demand so they can plan for increased production.

Generally, healthcare payers are not required to cover or reimburse for off-label uses of drugs. Unless a drug undergoes utilization management, payers cover most generic drugs for off-label uses because coverage is agnostic of indication. Clinical practice guidelines are highly influential in the widespread adoption of off-label treatments into the standard of care and are often referenced by payers making reimbursement decisions. In oncology, many off-label treatments are included in guidelines; only 62% of treatments in the NCCN are aligned with FDA-approved indications. For example, more than half of the NCCN recommendations for metastatic breast cancer are off-label treatments. Due to the breadth of off-label use, we anticipate payers would continue to cover repurposed generic drugs used off-label, even if there is a pathway available for non-manufacturers to pursue FDA approval.

We do not envision any form of exclusivity being granted for indications pursued via a labeling-only 505(b)(2) NDA. Given that the non-manufacturer sponsor would rely on existing products produced by multiple generic manufacturers, there is no new product to grant exclusivity. Even if some form of exclusivity were given to the non-manufacturer, it would be insufficient to guarantee the use of any particular drug product over another due to pharmacy-level substitution.

Slow Aging, Extend Healthy Life: New incentives to lower the late-life disease burden through the discovery, validation, and approval of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints

The world is aging. Today, some two thirds of the global population is dying from an age-related condition. Biological aging imposes significant socio-economic costs, increasing health expenses, reducing productivity, and straining social systems. Between 2010 and 2030, Medicare spending is projected to nearly double – to $1.2 trillion per year. Yet the costly diseases of aging can be therapeutically targeted before they become late-stage conditions like Alzheimer’s. Slowing aging could alleviate these burdens, reducing unpaid caregivers, medical costs, and mortality rates, while enhancing productivity. But a number of market failures and misaligned incentives stand in the way of extending the healthy lifespan of aging populations worldwide. New solutions are needed to target diseases before they are life-threatening or debilitating, moving from retroactive sick-care towards preventative healthcare.

The new administration should establish a comprehensive framework to incentivize the discovery, validation, and regulatory approval of biomarkers as surrogate endpoints to accelerate clinical trials and increase the availability of health-extending drugs. Reliable biomarkers or surrogate endpoints could meaningfully reduce clinical trial durations, and enable new classes of therapeutics for non-disease conditions (e.g., biological aging). An example is how LDL (a surrogate marker of heart health) helped enable the development of lipid-lowering drugs. The current lack of validated surrogate endpoints for major late-life conditions is a critical bottleneck in clinical research. Because companies do not capture the majority of the benefit from the (expensive) validation of biomarkers, the private sector under-invests in biomarker and surrogate endpoint validation. This leads to countless lives lost and to trillions of public dollars spent on age-related conditions that could be prevented by better-aligned incentives. It should be an R&D priority for the new administration to fund the collection and validation of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints, then gain regulatory approval for them. As we explain below, the existing FNIH Biomarkers Consortium does not fill this role.

Currently, companies are understandably hesitant to invest in validation without clear rewards or regulatory pathways. The proposed framework would encourage private companies and laboratories to contribute their biomarker data to a shared repository. This repository would expedite regulatory approval, moving away from the current product-by-product assessment that discourages data sharing and collaboration. Establishing a broader pathway within the FDA for standardized biomarker approval would allow validated biomarkers to be recognized for use across multiple products, reducing the existing incentives to safeguard data while increasing the supply of validated biomarkers and surrogate endpoints. Importantly, this would accelerate the development of drugs which holistically extend the healthspan of aging populations in the U.S. by preventing instead of treating late-stage conditions. (Statins similarly helped prevent millions of heart attacks.)

Key players such as the FDA, NIH, ARPA-H, and BARDA should collaborate to establish a streamlined pathway for the collection and validation of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints, allowing these to be recognized for use across multiple products. This initiative aligns with the administration’s priorities of accelerating medical innovation and improving public health with the potential to add trillions of dollars in economic value by making treatments and preventatives available sooner. This memo outlines a framework applicable to various diseases and conditions, using biological aging as a case study where the validation of predictive and responsive biomarkers may be vital for significant breakthroughs. Other critical areas include Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), where the lack of validated surrogate endpoints significantly hinders the development of life-saving and life-improving therapies. By addressing these bottlenecks, we can unlock new avenues for medical advancements that will profoundly improve public health and mitigate the fast-growing, nearly trillion-dollar Medicare spend on late-life conditions.

Challenge and Opportunity

By 2029, the United States will spend roughly $3 trillion dollars yearly – half its federal budget – on adults aged 65 and older. A good portion of these funds will go towards Medicare-related expenses that could be prevented. Yet the process of bringing preventative drugs to market is lengthy, costly, and currently lacking in commercial incentives. Even for therapeutics that target late-stage diseases, drug development often takes 10+ years and cost estimates range between $300 million to $2.8 billion. This extensive duration and expense are due, in part, to the reliance on traditional clinical endpoints, which require long-term observation and longitudinal data collection. The burden of chronic diseases is growing, and better biomarkers and surrogate endpoints are needed to accelerate the development of therapeutics that prevent non-communicable diseases and age-related decline. Chronological age, for instance, is a commonly used but inadequate surrogate marker for biological age. This means that, to date, clinical trials on therapeutics designed to improve the biology of aging take decades to validate, rather than years. As a result, pharmaceutical companies find more short-term rewards in treating late-stage diseases, since developing drugs that reduce overall age-related decline requires longer and currently uncertain endpoints.

The validation of reliable biomarkers and surrogate endpoints offers a promising solution to this challenge. Biological measures often correlate with and predict clinical outcomes, and can therefore provide early indications of whether a treatment is effective. If sufficiently predictive, biomarkers can serve as surrogate clinical endpoints, potentially reducing the duration and cost of clinical trials. Validated biomarkers must accurately predict clinical outcomes and be accepted by regulatory authorities, yet the validation process is underfunded due to insufficient commercial incentives for individual agents to share their biomarkers to be used as a public good. (From a purely financial standpoint, companies are better off targeting diseases with known endpoints.)

The most prominent existing efforts to advance biomarkers and surrogate endpoints are the Foundation for the National Institute of Health’s (FNIH) Biomarkers Consortium and the FDA’s Biomarker Qualification Program. Established in 2006, the Biomarkers Consortium is a public-private partnership aimed at advancing the development and use of biomarkers in medical research. Meanwhile, the FDA’s qualification program was the result of the 21st Century Cures Act, passed in 2016, which underscored the critical role biomarkers play in accelerating medical product development. The Act mandated the FDA to implement a more transparent and efficient process for biomarker qualification.

Despite the Consortium’s ambitious goals, the rate of biomarker qualification by the FDA has been slow. Since its inception in 2006, only a small number of biomarkers have been successfully qualified. This sluggish progress has been a source of criticism for stakeholders, especially given the high level of resources and collaboration involved. For example, the process of validating biomarkers for osteoarthritis under the Consortium’s “PROGRESS OA” project has been ongoing since Phase 1 and still faces hurdles before full qualification. We are of the view that this is the result of two issues. Firstly, the qualification process, which involves FDA approval, is seen as overly complex and time-consuming. Despite the 21st Century Cures Act aiming to streamline the process, resulting in the qualification pathway, it remains a significant challenge. The difficulty in navigating the regulatory landscape can limit the impact of Biomarkers Consortium (BC) projects. The Kidney Safety Project, for example, faced substantial regulatory hurdles before finally achieving the first qualification of a clinical safety biomarker. Secondly, even though the Consortium operates in a precompetitive space, there are ongoing challenges related to data sharing. Companies may still hesitate to share critical data that could advance biomarker validation out of concern for losing a competitive edge, which hampers collaboration. To address these issues, it is crucial to implement a framework that promotes data sharing in the academic and private sectors, providing strong incentives for the validation and regulatory approval of biomarkers, while improving regulatory certainty with a standardized regulatory process for surrogate endpoint validation.

The current boom in biotechnology underscores the urgency of addressing persisting inefficiencies. Without changes, we face a significant bottleneck in proving the efficacy of new drugs. This is exacerbated by Eroom’s Law—the observation that drug discovery is becoming slower and more expensive over time. This growing inefficiency threatens to hinder the development of new, life-saving treatments at a time when the American population is aging and rapid medical advancements are crucial to deter increasing medical and social costs. In just 11 years—between 2018 and 2029—the U.S. mandatory spending on Social Security and Medicare will more than double, from $1.3 trillion to $2.7 trillion per year. Yet the costly diseases of aging can be therapeutically targeted before they become late-stage conditions like Alzheimer’s. For federal policymakers, taking immediate action to improve data sharing and biomarker validation processes is vital. Failure to do so will not only stifle innovation but also delay the availability of critical therapies that could save countless lives and accelerate economic growth in the long run. Prompt policy intervention is essential to capitalize on the current advancements in biotechnology and ensure the development of new life-saving tests, tools, and drugs.

Implementing pull-incentives for data sharing now can help the United States adjust to its new demographic structure, where adults in advanced age prevail, while fertility rates decline. It can also mitigate the escalating costs and timelines of clinical trials, and accelerate the approval of life-saving, health-extending drugs. If our proposed framework is successfully implemented, a robust pool of biomarker data will be established, significantly facilitating the discovery and validation of biomarkers. This will result in several key advancements, including shortened clinical trial durations, increased R&D investment, faster drug approvals, and even increased drug efficacy. Additionally, new drug classes targeting non-disease endpoints, such as biological aging, could be developed. Just as the discovery of LDL as a surrogate marker of heart health was critical in enabling the testing and development of statins, the discovery of clinical-grade biomarkers may unlock new therapeutics designed to target the mechanisms that drive human aging, slowing down the progression of age-related diseases (like cancers) before they become deadly and socio-economically expensive.

Plan of Action

To address the challenge of inefficient data sharing, validation, and approval of biomarkers, we propose implementing a series of pull-incentives aimed at encouraging pharmaceutical companies to contribute their relevant biomarker data to a shared repository and undertake the necessary research and analysis for public validation. These validated biomarkers can then be formally accepted by regulators as surrogate endpoints for drug approval, accelerating the drug development process and reducing late-life costs.

Recommendation 1. An NIH-FDA initiative for Biomarkers and Surrogate Endpoints Within the NIA

Most existing agencies focus on single, often late-stage diseases. This is at odds with a holistic understanding of human biology. A new initiative within the National Institute on Aging (NIA) could be devoted to the discovery, collection, and validation of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints for overall human health and age-related decline. Most National Institutes of Health funds are currently devoted to the diseases of aging (think cancers, Alzheimer’s, heart disease, or Parkinson’s.) Within the NIA, research on Alzheimer’s disease alone receives roughly eight times more funding than the biology of aging, with few human-relevant results. Every federal agency and U.S. individual would benefit from better biomarkers of long-term health and from an understanding of how to measure the biology of aging. Yet no single agent has the incentives to collect and validate this data, for instance by shouldering the costs of validating predictive and responsive biomarkers of aging.

This new initiative could also be devoted to the development of preclinical, human-relevant methodologies that could broadly facilitate or streamline drug development. In 2022, the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 approved the use of in vitro and in silico New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) like cell-based assays (e.g. organs-on-chips) or computer models (like virtual cells) in preclinical development to reduce or replace animal studies, especially “where no pharmacologically relevant animal species exists.” This may be the case for human aging, where no single animal model reflects the full complex biology of our aging process.

At present, these technologies cannot accurately represent the multifactorial processes of aging, and they cannot model entire organisms. Much work remains to be done to even understand how to “code” aging into organs-on-chips. Yet if supplemented by approaches like in vivo pooled screening, next generations of human-relevant in vitro or in silico methodologies (like virtual cells) could be infused with the complex data needed to accelerate clinical trial results and increase drug efficacy. For in vitro and in silico models to reproduce key aspects of aging biology, a better understanding of how human aging works in living organisms — and what markers to include to represent it either virtually or in vitro — may be needed. Yet pharmaceutical companies, startups, health insurance firms, and even research hospitals again lack the incentives to shoulder the costs of collecting and validating this type of data. This means a new office within a federal agency may be needed to supply these incentives.

Recommendation 2. New Data-sharing Incentives

The specific incentives used would need to be developed in collaboration with policymakers and industry stakeholders, but a few are outlined below:

Pull-incentives

One possibility is offering transferable Priority Review Vouchers (PRVs) or similar pull incentives to companies that share their biomarker data. PRVs are currently awarded by the FDA to companies developing drugs for neglected tropical diseases, rare pediatric diseases, or medical countermeasures. A PRV allows the holder to expedite the FDA review of another drug from 10 months to 6 months, and holds significant financial value. Offering transferable PRVs for drugs designed to target biological aging, for instance, could create the incentives needed for pharmaceutical companies to target early-stage age-related conditions before they turn into diseases.

The creation of a new PRV category would require legislative action. Our proposed NIH-FDA initiative would be well positioned to oversee the issuance of PRVs, working with government agencies and think tanks to determine, for instance, what an “aging therapeutic” means, and what a company needs to achieve to gain a PRV for a longevity drug. The Alliance for Longevity Initiatives, for instance, has developed an advanced approval pathway for health-extending drugs that directly target the biology of aging. Another possible strategy would be for the FDA to encourage drugs that target multiple disease indications at once, perhaps offering discounts or incentives for every extra biomarker or surrogate endpoint validated. This could effectively encourage the development of drugs that do more than marginally improve on existing interventions.

We acknowledge that an overabundance of PRVs can saturate the market, decreasing their value and weakening the intended pull-incentive for pharmaceutical innovation. A response would be to demand that proposals to issue additional PRVs include a comprehensive market impact analysis to mitigate unintended economic consequences. Expanding the number of PRVs can also place extra demands on the FDA’s limited resources, potentially leading to longer approval times for other essential medications, even though PRV holders often delay redemption, preventing an immediate influx of priority review applications. The PRV system may inadvertently favor larger, well-established pharmaceutical companies that have the means to acquire and leverage PRVs effectively, creating barriers for smaller firms and startups. These are all spill-over problems worth solving for the potential upshot of mitigating late-life disease costs and encouraging drugs that holistically improve the human healthspan.

Biomarker Data Sharing as a Condition of Federal Funding

Federal funding recipients are legally obligated to make their research publicly accessible through agency-specific policies aimed at advancing open science. This mandate was strengthened by the 2022 OSTP Memorandum. Despite this clear mandate, the implementation of public access policies has been uneven across federal agencies, with progress varying due to differences in resources, technical infrastructure, and agency-specific priorities. The 2022 OSTP Public Access Memorandum aims to accelerate agency efforts to enhance public access infrastructure and policies. This updated guidance presents an opportunity for agencies to not only meet immediate data-sharing requirements but also to expand policy scopes to include essential clinical data, such as biomarker data from clinical trials. To meet these goals, agencies should ensure that funding agreements explicitly require the publication of comprehensive biomarker data and that suitable repositories are available to store and share these critical datasets effectively.

Case Study: Project NextGen

A prime example of the potential success of such initiatives is Project NextGen, a program led by BARDA in collaboration with the NIH to advance the next generation of COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. As part of its vaccine program, Project NextGen includes centralized immunogenicity assays with the overarching goal of establishing correlates of protection, which could serve as surrogate biomarkers for next-gen vaccines. These assays are collected during Phase 2b vaccine studies sponsored by Project NextGen, which have been designed to measure a number of secondary immunogenicity endpoints including systemic and mucosal immune responses. Developers share their assays so that they can be used as a public good, in return for federal funding. This effort demonstrates the feasibility and benefits of a federally led effort to share assay data to advance biomarker validation and drug development.

Recommendation 3. Create and Manage a Data Repository

To enhance collaborative research and ensure the efficient use of publicly funded clinical data, we recommend establishing a secure data repository. This repository will serve as a centralized platform for data submission, storage, and access. Management of the repository could be undertaken by a federal agency, such as the NIH, leveraging their experience with the Biomarkers Consortium, perhaps in partnership with non-governmental organizations like the Biomarkers of Aging Consortium. Drawing from existing models, such as Project NextGen’s assay data management, can provide valuable insights into the implementation and operationalization of the repository.

The cost of establishing and maintaining this repository, including data storage, management, and access controls, would be dwarfed by the socio-economic returns it could provide. This repository can facilitate data sharing, protect sensitive information, and promote a collaborative environment that accelerates biomarker validation and approval, while ensuring pharmaceutical companies that their hard-earned data is safely stored.

The securely stored data in the repository would primarily be accessible to qualified researchers, clinicians, and policymakers involved in biomarker research and development, including academic researchers, pharmaceutical companies, and public health agencies. Access would be granted through an application and review process. The benefits of this repository are multifaceted: it accelerates research by providing a centralized database, enhances collaboration among scientists and institutions, increases efficiency by reducing redundancy and improving data management, ensures data security through robust access controls, offers cost-effectiveness with long-term socio-economic returns, and supports regulatory bodies with comprehensive data sets for more informed decision-making.

Recommendation 4. Create A Regulatory Pathway with Broader Application

To accelerate the adoption of validated biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in drug development, we propose the creation of a streamlined regulatory approval process within the FDA. This new pathway would establish clear criteria and standardized procedures for biomarker evaluation and approval, facilitating their recognition for use across multiple products and therapeutic areas.

Currently, the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) operates the Biomarker Qualification Program (BQP), which allows drug developers to seek regulatory qualification for specific contexts of use. While this program fosters collaboration between the FDA and external stakeholders, biomarkers are qualified on a case-by-case basis, limiting their broader applicability across different drug development programs.

Additionally, the FDA maintains a Table of Surrogate Endpoints that have been used as the basis for drug approvals under the accelerated approval pathway. However, this table primarily serves as a reference and does not comprehensively address the need for a streamlined approval process for biomarkers and surrogate endpoints.

By developing a framework that moves away from traditional product-by-product assessments, the FDA could reduce existing barriers to biomarker and surrogate endpoint discovery and approval. This approach would encourage data sharing and collaboration among pharmaceutical companies and research institutions, leading to faster validation and broader acceptance of these critical tools in drug development.

This proposal builds upon existing legislative efforts, such as the 21st Century Cures Act of 2016, which includes provisions to accelerate medical product development and supports the use of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in the regulatory process. Furthermore, it aligns with the FDA’s ongoing efforts to provide clarity on evidentiary criteria for biomarker qualification, as outlined in the 2018 guidance document “Biomarker Qualification: Evidentiary Framework.”

Inspiration for this approach can be drawn from the Advanced Approval Pathway for Longevity Medicines (AAPLM) proposed by the Alliance for Longevity Initiatives (See AAPLM-Whitepaper). The AAPLM includes provisions such as a special approval track, a priority review voucher system, and indication-by-indication patent term extensions, which align economic incentives with the transformative health improvements that longevity medicines can provide. These measures offer a valuable template for facilitating the recognition and approval of biomarkers. Adding to the existing FDA table of surrogate endpoints that can serve as the basis for drug approval or licensure, and referencing existing collaborations between the NIH and FDA, such as the Biomarkers Consortium, can provide a robust foundation for new biomarker evaluations. Ultimately, this regulatory innovation will support the development of life-saving drugs, enhance public health outcomes, and meaningfully contribute to economic growth by bringing effective treatments to market more quickly.

Conclusion

Today, over two thirds of all deaths in the United States are the result of an age-related condition. The burden of non-communicable diseases is growing, and better biomarkers and surrogate endpoints are needed to target diseases before they are life-threatening or debilitating. The next administration should implement a comprehensive framework to promote data sharing and incentivize the validation and regulatory approval of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints. This aligns directly with the administration’s goal to make Americans healthy. These solutions can substantially reduce the duration and cost of clinical trials, accelerate the development of life-saving drugs, and improve public health outcomes. It is possible and necessary to create an environment that encourages and rewards pharmaceutical companies to share crucial data that accelerates medical innovation. By discovering and validating predictive and responsive biomarkers of health and disease, new therapeutic classes can be developed to directly target biological aging and prevent most forms of cancers, heart disease, frailty, vulnerability to severe infection, and Alzheimer’s. This will enable the United States to remain at the forefront of medical research, and to respond to the growing demographic crisis of aging populations in declining health.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

A number of market failures stand in the way of the discovery and validation of predictive, reliable, and responsive biomarkers. First, it’s currently expensive to test drugs in multiple disease indications, which means pharmaceutical companies are often incentivized to focus on late-stage diseases (e.g. delaying death by a terminal cancer by three months), since this drug class is more easily and quickly trialed. The FDA also strongly assumes that a treatment ought to modulate a single outcome. (Think life/death; heart disease/no heart disease.) Therapeutics that target biological aging, for instance, would take decades to test without validated biomarkers or widely accepted surrogate endpoints.