Behavioral Economics Megastudies are Necessary to Make America Healthy

Through partnership with the Doris Duke Foundation, FAS is advancing a vision for healthcare innovation that centers safety, equity, and effectiveness in artificial intelligence. Inspired by work from the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) and Arizona State University (ASU) symposiums, this memo explores new research models such as large-scale behavioral “megastudies” and how they can transform our understanding of what drives healthier choices for longer lives. Through policy entrepreneurship FAS engages with key actors in government, research, academia and industry. These recommendations align with ongoing efforts to integrate human-centered design, data interoperability, and evidence-based decision-making into health innovation.

By shifting funding from small underpowered randomized control trials to large field experiments in which many different treatments are tested synchronously in a large population using the same objective measure of success, so-called megastudies can start to drive people toward healthier lifestyles. Megastudies will allow us to more quickly determine what works, in whom, and when for health-related behavioral interventions, saving tremendous dollars over traditional randomized controlled trial (RCT) approaches because of the scalability. But doing so requires the government to back the establishment of a research platform that sits on top of a large, diverse cohort of people with deep demographic data.

Challenge and Opportunity

According to the National Research Council, almost half of premature deaths (< 86 years of age) are caused by behavioral factors. Poor diet, high blood pressure, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and tobacco use are the primary causes of early death for most of these people. Yet, despite studying these factors for decades, we know surprisingly little about what can be done to turn these unhealthy behaviors into healthier ones. This has not been due to a lack of effort. Thousands of randomized controlled trials intended to uncover messaging and incentives that can be used to steer people towards healthier behaviors have failed to yield impactful steps that can be broadly deployed to drive behavioral change across our diverse population. For sure, changing human behavior through such mechanisms is controversial, and difficult. Nonetheless studying how to bend behavior should be a national imperative if we are to extend healthspan and address the declining lifespan of Americans at scale.

Limitations of RCTs

Traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which usually test a single intervention, are often underpowered, and expensive, and short-lived, limiting their utility even though RCTs remain the gold standard for determining the validity of behavioral economics studies. In addition, because the diversity of our population in terms of biology, and culture are severely limiting factors for study design, RCTs are often conducted on narrow, well-defined populations. What works for a 24-year-old female African American attorney in Los Angeles may not be effective for a 68-year-old male white fisherman living in Mississippi. Overcoming such noise in the system means either limiting the population you are examining through demographics, or deploying raw power of numbers of study participants that can allow post study stratification and hypothesis development. It also means that health data alone is not enough. Such studies require deep personal demographic data to be combined with health data, and wearables. In essence, we need a very clear picture of the lives of participants to properly identify interventions that work and apply them appropriately post-study on broader populations. Similarly, testing a single intervention means that you cannot be sure that it is the most cost-effective or impactful intervention for a desired outcome. This further limits the ability to deploy RCTs at scale. Finally, the data sometimes implies spurious associations. Therefore, preregistration of endpoints, interventions, and analysis of such studies will make for solid evidence development even if the most tantalizing outcomes come from sifting through the data later to develop new hypotheses that can be further tested.

Value of Megastudies

Professors Angela Duckworth and Katherine Milkman, at the University of Pennsylvania, have proposed an expansion of the use of megastudies to gain deeper behavioral insights from larger populations. In essence, megastudies are “massive field experiments in which many different treatments are tested synchronously in a large sample using a common objective outcome.” This sort of paradigm allows independent researchers to develop interventions to test in parallel against other teams. Participants are randomly assigned across a large cohort to determine the most impactful and cost-effective interventions. In essence, the teams are competing against each other to develop the most effective and practical interventions on the same population for the same measurable outcome.

Using this paradigm, we can rapidly assess interventions, accelerate scientific progress by saving time and money, all while making more appropriate comparisons to bend behavior towards healthier lifestyles. Due to the large sample sizes involved and deep knowledge of the demographics of participants, megastudies allow for the noise that is normal in a broad population that normally necessitates narrowing the demographics of participants. Further, post study analysis allows for rich hypothesis generation on what interventions are likely to work in more narrow populations. This enables tailored messaging and incentives to the individual. A centralized entity managing the population data reduces costs and makes it easier to try a more diverse set of risk-tolerant interventions. A centralized entity also opens the door to smaller labs to participate in studies. Finally, the participants in these megastudies are normally part of ongoing health interactions through a large cohort study or directly through care providers. Thus, they benefit directly from participation and tailored messages and incentives. Additionally, dataset scale allows for longer term study design because of the reduction in overall costs. This enables study designers to determine if their interventions work well over a longer period of time or if the impact of interventions wane and need to be adjusted.

Funding and Operational Challenges

But this kind of “apples to apples” comparison has serious drawbacks that have prevented megastudies from being used routinely in science despite their inherent advantage. First, megastudies require access to a large standing cohort of study participants that will remain in the cohort long term. Ideally, the organizer of such studies should be vested in having positive outcomes. Here, larger insurance companies are poor targets for organizing. Similarly, they have to be efficient, thus, government run cohorts, which tend to be highly bureaucratic, expensive, and inefficient are not ideal. Not everything need go through a committee. (Looking at you, All of Us at NIH and Million Veterans Program at the VA).

Companies like third party administrators of healthcare plans might be an ideal organizing body, but so can companies that aim to lower healthcare costs as a means of generating revenue through cost savings. These companies tend to have access to much deeper data than traditional cohorts run by government and academic institutions and could leverage that data for better stratifying participants and results. However, if the goal of government and philanthropic research efforts is to improve outcomes, then they should open the aperture on available funds to stand up a persistent cohort that can be used by many researchers rather than continuing the one-off paradigm, which in the end is far more expensive and inefficient. Finally, we do not imply that all intervention types should be run through megastudies. They are an essential, albeit underutilized tool in the arsenal, but not a silver bullet for testing behavioral interventions.

Fear of Unauthorized Data Access or Misuse

There is substantial risk when bringing together such deep personal data on a large population of people. While companies compile deep data all the time, it is unusual to do so for research purposes and will, for sure, raise some eyebrows, as has been the case for large studies like the aforementioned All of Us and the Million Veteran’s Program.

Patients fear misuse of their data, inaccurate recommendations, and biased algorithms—especially among historically marginalized populations. Patients must trust that their data is being used for good, not for marketing purposes and determining their insurance rates.

Icons © 2024 by Jae Deasigner is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Need for Data Interoperability

Many healthcare and community systems operate in data silos and data integration is a perennial challenge in healthcare. Patient-generated data from wearables, apps, or remote sensors often do not integrate with electronic health record data or demographic data gathered from elsewhere, limiting the precision and personalization of behavior-change interventions. This lack of interoperability undermines both provider engagement and user benefit. Data fragmentation and poor usability requires designing cloud-based data connectors and integration, creating shared feedback dashboards linking self-generated data to provider workflows, and creating and promoting policies that move towards interoperability. In short, given the constantly evolving data integration challenge and lack of real standards for data formats and integration requirements, a dedicated and persistent effort will have to be made to ensure that data can be seamlessly integrated if we are to draw value from combining data from many sources for each patient.

Additional Barriers

One of the largest barriers to using behavioral economics is that some rural, tribal, low-income, and older adults face access barriers. These could include device affordability, broadband coverage, and other usability and digital literacy limitations. Megastudies are not generally designed to bridge this gap leaving a significant limitation of applicability for these populations. Complicating matters, these populations also happen to have significant and specific health challenges unique to their cohorts. As the use of behavioral economic levers are developed, these communities are in danger of being left behind, further exacerbating health disparities. Nonetheless, insight into how to reach these populations can be gained for individuals in these populations that do have access to technology platforms. Communications will have to be tailored accordingly.

External motivators have been consistently shown to be the essential drivers of behavioral change. But motivation to sustain a behavior change and continue using technology often wanes over time. Embedding intrinsic-value rewards and workplace incentives may not be enough. Therefore, external motivations likely have to be adjusted over time in a dynamic system to ensure that adjustments to the behavior of the individual can be rooted in evidence. Indeed, study of the dynamic nature of driving behavioral change will be necessary due to the likelihood of waning influence of static messaging. By designing reward systems that tie personal values and workplace wellness programs sustained engagement through social incentives and tailored nudges may keep users engaged.

Plan of Action

By enabling a private sector entity to create a research platform using patient data combined with deep demographic data, and an ethical framework for access and use, we can create a platform for megastudies. This would allow the rapid testing of behavioral interventions that steer people towards healthier lifestyles, saving money, accelerating progress, and better understanding what works, in whom, and when for changing human behavior.

This could have been done through either the All of Us program or Million Veterans program or a different large cohort study, but neither program has the deep demographic and lifestyle data required to stratify their population. Both are mired in bureaucratic lethargy that is common in large scale government programs. Health insurance companies and third-party administrators of health insurance can gather such data, be nimbler, create a platform for communicating directly with patients, coordinate with their clinical providers. But one could argue that neither entity has a real incentive to bend behavior and encourage healthy lifestyles. Simply put, that is not their business.

Recommendation 1. Issue a directive to agencies to invest in the development of a megastudy platform for health behavioral economics studies.

The White House of HHS Secretary should direct the NIH or ARPA-H to develop a plan for funding the creation of a behavioral economics megastudy platform. The directive should include details on the ethical and technical framework requirements as well as directions for development of oversight of the platform once it is created. The platform should be required to establish a sustainability plan as part of the application for a contract to create the megastudy platform.

Recommendation 2. Government should fund the establishment of a megastudy platform.

ARPA-H and/or DARPA should develop a program to establish a broad research platform in the private sector that will allow for megastudies to be conducted. Then research teams can, in parallel, test dozens of behavioral interventions on populations and access patient data. This platform should have required ethical rules and be grounded in data sovereignty that allows patients to opt out of participation and having their data shared.

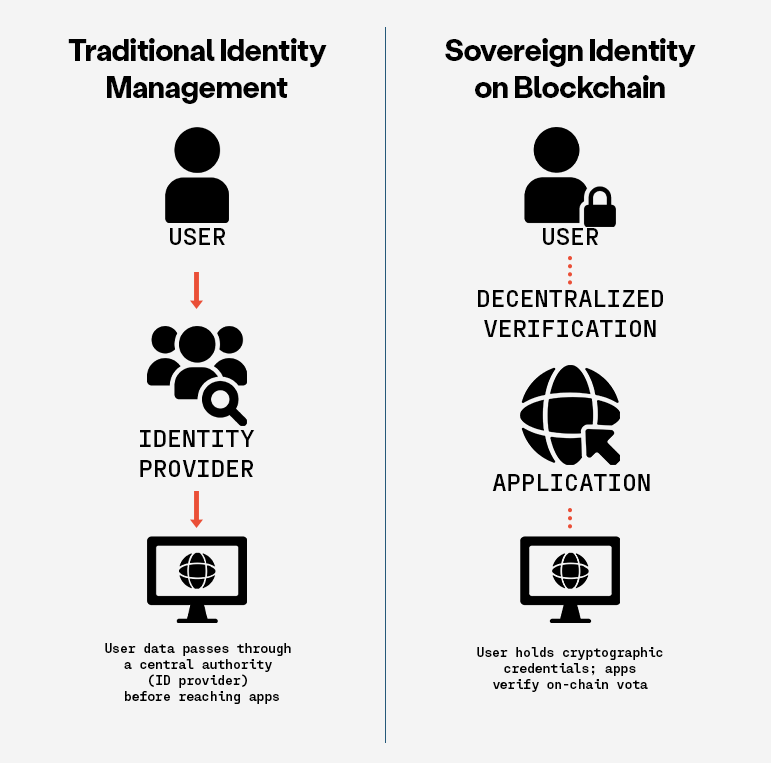

Data sovereignty is one solution to the trust challenge. Simply put, data sovereignty means that patients have access to the data on themselves (without having to pay a fee that physicians’ offices now routinely charge for access) and control over who sees and keeps that data. So, if at any time, a participant changes their mind, they can get their data and force anyone in possession of that data to delete it (with notable exceptions, like their healthcare providers). Patients would have ultimate control of their data in a ‘trust-less’ way that they never need to surrender, going well past the rather weak privacy provisions of HIPAA, so there is no question that they are in charge.

We suggest that using blockchain and token systems for data transfer would certainly be appropriate. Data held in a federated network to limit the danger of a breach would also be appropriate.

Recommendation 3. The NIH should fund behavioral economics megastudies using the platform.

Once the megastudy platform(s) are established, the NIH should make dedicated funds available for researchers to test for behavioral interventions using the platform to decrease costs, increase study longevity, and improve speed and efficiency for behavioral economics studies on behavioral health interventions.

Conclusion

Randomized controlled trials have been the gold standard for behavioral research but are not well suited for health behavioral interventions on a broad and diverse population because of the required number of participants, typical narrow population, recruiting challenges, and cost. Yet, there is an urgent need to encourage and incentivize d health related behaviors to make Americans healthier. Simply put, we cannot start to grow healthspan and lifespan unless we change behaviors towards healthier choices and habits. When the U.S. government funds the establishment of a platform for testing hundreds of behavioral interventions on a large diverse population, we will start to better understand the interventions that will have an efficient and lasting impact on health behavior. Doing so requires private sector cooperation and strict ethical rules to ensure public trust.

This memo produced as part of Strengthening Pathways to Disease Prevention and Improved Health Outcomes.

Making Healthcare AI Human-Centered through the Requirement of Clinician Input

Through partnership with the Doris Duke Foundation, FAS is advancing a vision for healthcare innovation that centers safety, equity, and effectiveness in artificial intelligence. Informed by the NYU Langone Health symposium on transforming health systems into learning health systems, FAS seeks to ensure that AI tools are developed, deployed, and evaluated in ways that reflect real-world clinical practice. FAS is leveraging its role in policy entrepreneurship to promote responsible innovation by engaging with key actors in government, research, and software development. These recommendations align with emerging efforts across health systems to integrate human-centered AI and evidence-based decision-making into digital transformation. By shaping AI grant requirements and post-market evaluation standards, these ideas aim to accelerate safe, equitable implementation while supporting ongoing learning and improvement.

The United States must ensure AI improves healthcare while safeguarding patient safety and clinical expertise. There are three priority needs:

- Embedding clinician involvement in the development and testing of AI tools

- Using representative data and promoting human-centered design

- Maintaining continuous oversight through post-market evaluation and outcomes-based contracting

This memo examines the challenges and opportunities related to integrating AI tools into healthcare. It emphasizes how human-centered design must ensure these technologies are tailored to real-world clinical environments. As AI adoption grows in healthcare, it is essential that clinician feedback is embedded into the federal grant requirements for AI development to ensure these systems are effective and aligned with real-world needs. Embedding clinician feedback into grant requirements for healthcare AI development and ensuring the use of representative data will assist with promoting safety, accuracy, and equity in healthcare tools. In addition, regular updates to these tools based on evolving clinical practices and patient populations must be part of the development lifecycle to maintain long-term reliability. Continuous post-market surveillance is necessary to ensure these tools remain both accurate and equitable. By taking these steps, healthcare systems can harness the full potential of AI while safeguarding patient safety and clinician expertise. Federal agencies such as the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can incentivize clinician involvement through outcomes-based contracting approaches that link funding to measurable improvements in patient care. This strategy ensures that grant recipients embed clinician expertise at key stages of development and testing, ultimately aligning incentives with real-world health outcomes.

Challenge and Opportunity

The use of AI tools such as predictive triage classifiers and large language models (LLMs) have the potential to improve care delivery. However, there are significant challenges in integrating these tools effectively into daily clinical workflows without meaningful clinician involvement. As just one example, AI tools used in chronic illness triage can be particularly useful in helping to prioritize patients based on the severity of their condition, which can lead to timely care delivery. However, without direct involvement from clinicians in validating, interpreting, and guiding AI recommendations, these tools can suffer from poor usability and limited real-world effectiveness. Even highly accurate tools can become irrelevant if they are not adopted and clinicians do not engage with them, thereby reducing the positive impact they can have on patient outcomes.

Mysterious Inner Workings

The mysterious box of AI has fueled skepticism among healthcare providers and undermined trust among patients. Moreover, when AI systems lack clear and interpretable explanations, clinicians are more likely to avoid or distrust them. This response is attributed to what’s known as algorithm aversion. Algorithm aversion occurs when clinicians lose trust in a tool after seeing it make errors, making future use less likely, even if the tool is usually accurate. Designing AI with human-centered principles, particularly offering clinicians a role where they can validate, interpret, and guide AI recommendations, will help build trust and ensure decisions remain grounded in clinical expertise. A key approach to increasing trust and usability would be institutionalizing clinician engagement in the early stages of the development process. By involving clinicians during the development and testing phases, AI developers can ensure the tools fit seamlessly into clinical workflows. This will also help to mitigate concerns about the tool’s real-world effectiveness, as clinicians will be more likely to adopt tools they feel confident in. Without this collaborative approach, AI tools risk being sidelined or misused, preventing health systems from becoming genuinely adaptive and learning oriented.

Lack of Interoperability

A significant challenge in deploying AI tools across healthcare systems is the issue of interoperability. Most patients receive care across multiple providers and healthcare settings, making it essential for AI tools to be able to seamlessly integrate with electronic health records (EHR) and other clinical systems. Not having this integration could lead to tools losing their clinical relevance, effectiveness, and ability to be adopted on a larger scale. This lack of connectivity can lead to inefficiencies, duplicate testing, and other harmful errors. One way to address this is through a contracting process called Outcomes-based contracting (OBC), discussed shortly.

Trust in AI and Skill Erosion

Beyond trust and usability, there are broader risks associated with sidelining clinicians during AI integration. The use of AI tools without clinician input also presents the risk of clinician deskilling. Deskilling refers to the occurrence where clinicians’ skills and decision-making abilities erode over time due to their reliance on AI tools. This skill erosion leads to a decline in the judgement in situations where AI may not be readily available or suitable. Recent evidence from the ACCEPT trial shows that endoscopists’ performance dropped in non-AI settings after months of AI-assisted procedures. This presents a troubling phenomenon that we should aimt to prevent. AI-induced skill erosion also raises ethical concerns, particularly in complex environments where over-reliance on AI could erode clinical judgement and autonomy. If clinicians become too dependent on automated outputs, their ability to make critical decisions may be compromised, potentially impacting patient safety.

Embedded Biases

In addition to the erosion of human skills, AI systems also risk embedding biases if trained on unrepresentative data, leading to unfair or inaccurate outcomes across different patient groups. AI tools may present errors that appear plausible, such as generating nonexistent terms, which pose serious safety concerns, especially when clinicians don’t catch those mistakes. A systematic review of AI tools found that 22% of studies involved clinicians throughout the development phase. This lack of early clinician involvement has contributed to usability and integration issues across AI healthcare tools.

All of these issues underscore how critical clinician involvement is in the development of AI tools to ensure they are usable, effective, and safe. Clinician involvement should include defining relevant clinical tasks, evaluating interpretability of the system, validating performance across diverse patient groups, and setting standards for handoff between AI and clinician decision-making. Therefore, funding agencies should require AI developers to incorporate representative data and meaningful clinician involvement in order to mitigate these risks. Recognizing these challenges, it’s crucial to understand that implementing and maintaining AI requires continual human oversight and substantial infrastructure. Many health systems find this infrastructure too resource-intensive to properly sustain. Given the complexity of these challenges, without adequate governance, transparency, clinician training, and ethical safeguards, AI may hinder rather than help the transition to an enhanced learning health system.

Outcome-based Models (OBM)

To ensure that AI tools deliver properly, the federal contracting process should reinforce clinical involvement through measurable incentives. Outcomes-based contracting (OBC), a model where payments or grants are tied to demonstrated improvements in patient outcomes, can be a powerful tool. This model is not only a financing mechanism, but serves as a lever to institutionalize clinician engagement. By tying funding to real-world clinical impact, this compels developers to design tools that clinicians will use and find value in, ultimately increasing usability, trust, and adoption. This model provides a clear reward for impact rather than just for building tools or producing novel methods.

Leveraging outcomes-based models could also help institutionalize clinician engagement in the funding lifecycle. This would ensure developers demonstrate explicit plans for clinician participation through staff integration or formal consultation as a prerequisite for funding. Although AI tools may be safe and effective at the initial onset of their use, performance can change over time due to various patient populations, changes in clinical practice, and updates to software. This is known as model degradation. Therefore, a crucial component of using these AI tools needs to be regular surveillance to ensure the tools remain accurate, responsive to real-world use with clinicians and patients, and equitable. However, while clinician involvement is essential, it is important to acknowledge that including clinicians in all stages of the AI tool development, testing, deployment, and evaluation may not be realistic given the significant time cost for clinicians, their competing clinical responsibilities, and their limited familiarity with AI technology. Despite these factors, there are ways to engage clinicians effectively at key decision points during the AI development and testing process without requiring their presence at every stage.

Urgency and Federal Momentum

Major challenges associated with integrating AI into clinical workflows due to poor usability, algorithm aversion, clinician skepticism, and the potential for embedded biases in these tools highlight a need for thoughtful deployment of these tools. These challenges have presented a sense of urgency in light of recent healthcare shifts, particularly with the rapid acceleration of AI adoption after the COVID-19 pandemic. This drove breakthroughs in the areas of telemedicine, diagnostics, and pharmaceutical innovation that simply weren’t possible before. However, with the rapid pace of integration also comes the risk of unregulated deployment, potentially embedding safety vulnerabilities. Federal momentum supports this growth, with directives placing emphasis on AI safety, transparency, and responsible deployment, including the authorization of over 1,200 AI powered medical devices, primarily used in radiology, cardiology, and pathology, which tend to be areas that are complex in nature. However, without clinician involvement and the use of representative data for training, algorithms for devices such as the ones mentioned may remain biased and fail to integrate smoothly into care delivery. This disconnect could delay adoption, reduce clinical impact, and increase the risk of patient harm. Therefore, it’s imperative we set standards, embed clinician expertise in AI design, and ensure safe, effective deployment for the specific use of care delivery.

Furthermore, this moment of federal momentum aligns with broader policy shifts. As highlighted by a recent CMS announcement, the White House and national health agencies are working with technology leaders to create a patient-centric healthcare ecosystem. This includes a push for interoperability, clinical collaboration, and outcomes-driven innovation, all of which bolster the case for clinician engagement being woven into the very fabric of AI development. AI can potentially improve patient outcomes dramatically, as well as increase cost-efficiency in healthcare. Yet, without structured safeguards, these tools may deepen existing health inequities. However, with proper input from clinicians, these tools can reduce diagnostic errors, improve accuracy in high-stakes cases such as cancer detection, and streamline workflows, ultimately saving lives and reducing unnecessary costs.

As AI systems become further embedded into clinical practice, they will help to shape standards of care, influencing clinical guidelines and decision-making pathways. Furthermore, interoperability is essential when using these tools because most patients receive care from multiple providers across systems. Therefore, AI tools must be designed to communicate and integrate data from various sources, including electronic health records (EHR), lab databases, imaging systems, and more. Enabling shared access can enhance the coordination of care and reduce redundant testing or conflicting diagnoses. To ensure this functionality, clinicians must help design AI tools that account for real-world care delivery across what is currently a fragmented system.

Reshaping Healthcare AI

These challenges and risks culminate in a moment of opportunity where we can reshape and revolutionize the way AI supports healthcare delivery to ensure that its design is trustworthy and focused on outcomes. To fully realize this opportunity, clinicians must be embedded into various stages of AI development technology to improve its safety, usability, and adoption in healthcare settings. While some developers do involve clinicians during development, this practice is not the standard. Bridging this gap requires targeted action to ensure clinical expertise is consistently incorporated from the start. One way to achieve this is through federal agencies requiring AI developers to integrate representative data and clinician feedback into their AI tools as a condition of funding eligibility. This approach would improve the usability of the tool and enhance its contextual relevance to diverse patient populations and practice environments. Further, it would address current shortcomings as evidence has shown that some AI tools are poorly integrated into clinical workflows, which not only reduces their impact, but also undermines broader adoption and clinician confidence in the systems. Moreover, creating a clinician feedback loop for these systems will reduce the clerical burden that many clinicians experience and allow them to spend more dedicated time with their patients. Through the incorporation of human-centered design, we can mitigate issues that would normally arise by using clinician expertise during the development and testing process. This approach would build trust amongst clinicians and improve patient safety, which is most important when aiming to reduce errors and misinterpretations of diagnoses. With strong requirements and funding standards in place as safeguards, AI can transform health systems into adaptable learning environments that produce evidence and deliver equitable and higher quality care. This is a pivotal opportunity to showcase how innovation can support human expertise and strengthen trust in healthcare.

AI has the potential to dramatically improve patient outcomes and healthcare cost-efficiency, particularly in high-stakes diagnostic and treatment decisions like oncology, and critical care. In these areas, AI can analyze imaging, lab, and genomic data to uncover patterns that may not be immediately apparent to clinicians. For example, AI tools have shown promise in improving diagnostic accuracy in cancer detection and reducing the time clinicians spend on tasks like charting, allowing for more face-to-face time with patients.

However, these tools must be designed with clinician input at key stages, especially for higher-risk conditions, or tools may be prone to errors or fail to integrate into clinical workflows. By embedding outcome-based contracting (OBC) into federal funding and aligning financial incentives with clinical effectiveness, we are encouraging the development and use of AI tools that have the ability to improve patient outcomes and strengthen the healthcare system’s shift toward value-based care. This supports a broader shift toward value-based care where outcomes, not just outputs, define success.

The connection between OBC and clinician involvement is straightforward. When clinicians are involved in the design and testing of AI tools, these tools are more likely to be effective in real-world settings, thereby improving outcomes and justifying the financial incentives tied to OBC. AI tools can provide significant value for healthcare use in high-stakes, diagnostic and treatment decisions (oncology, cardiology, and critical care) where errors have large consequences on patient outcomes. In those settings, AI can assist by analyzing imaging, lab, and genomic data to uncover patterns that may not be immediately apparent to clinicians. However, these tools should not function autonomously, and input from clinicians is critical to validate AI outputs, specifically for issues where mortality or morbidity is high. In contrast, for lower-risk or routine care of common colds or minor dermatologic conditions, AI may be useful as a time-saving tool that does not require the same depth of clinician oversight.

Plan of Action

These actionable recommendations aim to help federal agencies and health systems embed clinician involvement, representative data, and continuous oversight into the lifecycle of healthcare AI.

Recommendation 1. Federal Agencies Should Require Clinician Involvement in the Development and Testing of AI Tools used in Clinical Settings.

Federal agencies should require clinician involvement in all aspects of the development and testing of AI healthcare tools. This mechanism could be enforced through a combination of agency guidance and tying funding eligibility to specific roles and checkpoints for clinicians. Specifically, agencies like the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can issue guidance mandating clinician participation, and can tie AI tool development funding to the inclusion of clinicians in the design and testing phases. Guidance can mandate clinician involvement at critical stages for: (1) defining clinical tasks and user interface requirements (2) validating interpretability and performance for diverse populations (3) piloting in real workflows and (4) reviewing for safety and bias metrics. This would ensure AI tools used in clinical settings are human-centered, effective, and safe.

Key stakeholders who may wish to be consulted in this process include offices underneath the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) such as the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). ONC and FDA should work to issue guidance encouraging clinician engagement during the premarket review. This would allow experts thorough review of scientific data and real-world evidence to ensure that the tools used are human-centered and have the ability to improve the quality of care.

Recommendation 2. Incentivize Clinician Involvement Through Outcomes-Based Contracting

Federal agencies such as the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) should incorporate outcomes-based contracting requirements into AI-related healthcare grant programs. Funding should be awarded to grantees who: (1) include clinicians as part of their AI design teams or advisory boards, (2) develop formal clinician feedback loops, and (3) demonstrate measurable outcomes such as improved diagnostic accuracy or workflow efficiency. These outcomes are essential when thinking about clinician engagement and how it will improve the usability of AI tools and their clinical impact.

Key stakeholders include HHS, CMS, ONC, AHRQ, as well as clinicians, AI developers, and potentially patient advocacy organizations. These requirements should prioritize funding for entities that demonstrate clear clinician involvement at key development and testing phases, with metrics tied to improvements in patient outcomes and clinician satisfaction. This model would align with CMS’s ongoing efforts to foster a patient-centered, data-driven healthcare ecosystem that uses tools designed with clinical needs in mind, as recently emphasized during the health tech ecosystem initiative meeting. Embedding outcomes-based contracting into the federal grant process will link funding to clinical effectiveness and incentivize developers to work alongside clinicians through the lifecycle of their AI tools.

Recommendation 3. Develop Standards for AI Interoperability

ONC should develop interoperability guidelines that enable AI systems to share information across platforms while simultaneously protecting patient privacy. As the challenge of healthcare data fragmentation has become evident, AI tools must seamlessly integrate with diverse electronic healthcare records (EHRs) and other clinical platforms to ensure their effectiveness.

An example of successful interoperability frameworks can be seen through the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA), which aims to establish a nationwide interoperability infrastructure for the exchange of health information. Using a model such as this one can establish seamless integration across different healthcare settings and EHR systems, ultimately promoting efficient and accurate patient care. This effort would involve the consultation of clinicians, electronic health record vendors, patients, and AI developers. These guidelines will help ensure that AI tools can be used safely and effectively across clinical settings.

Recommendation 4. Establish Post-Market Surveillance and Evaluation of Healthcare AI Tools to Enhance Performance and Reliability

Federal agencies such as FDA and AHRQ should establish frameworks that can be used for the continuous monitoring of AI tools in clinical settings. These frameworks for privacy-protected data collection should incorporate feedback loops that allow real-world data from clinicians and patients to inform ongoing updates and improvements to the systems. This ensures the effectiveness and accuracy of the tools over time. Special emphasis should be placed on bias audits that can detect disparities in the system’s performance across different patient groups. Bias audits will be key to identifying whether AI tools inadvertently present disadvantages to specific populations based on the data they were trained on. Agencies should require that these audits be conducted routinely as part of the post-market surveillance process. The surveillance data collected can be used for future development cycles where AI tools are updated or re-trained to address shortcomings.

Evaluation methods should track clinician satisfaction, error rates, diagnostic accuracy, and reportability of failures. During this ongoing evaluation process, incorporating routine bias audits into post-market surveillance will ensure that these tools remain equitable and effective over time. Funding for this initiative could potentially be provided through a zero-cost, fee-based structure or federally appropriated grants. Key stakeholders in this process could include clinicians, AI developers, and patients, all of whom would be responsible for providing oversight.

Conclusion

Integrating AI tools into healthcare has an immense amount of potential to improve patient outcomes, streamline clinical workflows, and reduce errors and bias. However, without clinician involvement in the development and testing of these tools, we risk continual system degradation and patient harm. Requiring that all AI systems used for healthcare are human-centered through clinician input will ensure these systems are effective, safe, and align with real-world clinical needs. This human-centered approach is critical not only for usability, but also for building trust among clinicians and patients, fostering the adoption of AI tools, and ensuring they function properly in real-world clinical settings.

In addition, aligning funding and clinical outcomes through outcomes-based contracting adds a mechanism that forces accountability and ensures lasting impact. When developers are rewarded for improving safety, usability, and equity through clinician involvement, we can transform AI tools into safer care. There is an urgency to address these challenges due to the rapid adoption of AI tools which will require safeguards and ethical oversight. By embedding these recommendations into funding opportunities, we will move America toward building trustworthy healthcare systems that enhance patient safety, clinician expertise, and are adaptive while maximizing AI’s potential for improving patient outcomes. Clinician engagement, both in the development process and through ongoing feedback loops will be the foundation of this transformation. With the right structures in place, we can ensure AI becomes a trusted partner in healthcare and not a risk to it.

This memo produced as part of Strengthening Pathways to Disease Prevention and Improved Health Outcomes.

A National Blueprint for Whole Health Transformation

Despite spending over 17% of GDP on health care, Americans live shorter and less healthy lives than their peers in other high-income countries. Rising chronic disease and mental health challenges as well as clinician burnout expose the limits of a system built to treat illness rather than create health. Addressing chronic disease while controlling healthcare costs is a bipartisan goal, the question now is how to achieve this shared goal? A policy window is opening now as Congress debates health care again – and in our view, it’s time for a “whole health” upgrade.

Whole Health is a proven, evidence-based framework that integrates medical care, behavioral health, public health, and community support so that people can live healthier, longer, and more meaningful lives. Pioneered by the Veterans Health Administration, Whole Health offers a redesign to U.S. health and social systems: it organizes how health is created and supported across sectors, shifting power and responsibility from institutions to people and communities. It begins with what matters most to people–their purpose, aspirations, and connections–and aligns prevention, clinical care, and social supports accordingly. Treating Whole Health as a shared public priority would help ensure that every community has the conditions to thrive.

Challenge and Opportunity

The U.S. health system spends over $4 trillion annually, more per capita than any other nation, yet underperforms on life expectancy, infant mortality, and chronic disease management. The prevailing fee-for-service model fragments care across medical, behavioral, and social domains, rewarding treatment over prevention. This fragmentation drives costs upward, fuels clinician burnout, and leaves many communities without coordinated support.

At this inflection point in our declining health outcomes and growing public awareness of the failures of our health system, federal prevention and public health programs are under review, governors are seeking cost-effective chronic disease solutions, and the National Academies is advocating for new healthcare models. Additionally, public demand for evidence-based well-being is growing, with 65% of Americans prioritizing mental and social health. There is clear demand for transformation in our health care system to deliver results in a much more efficient and cost effective way.

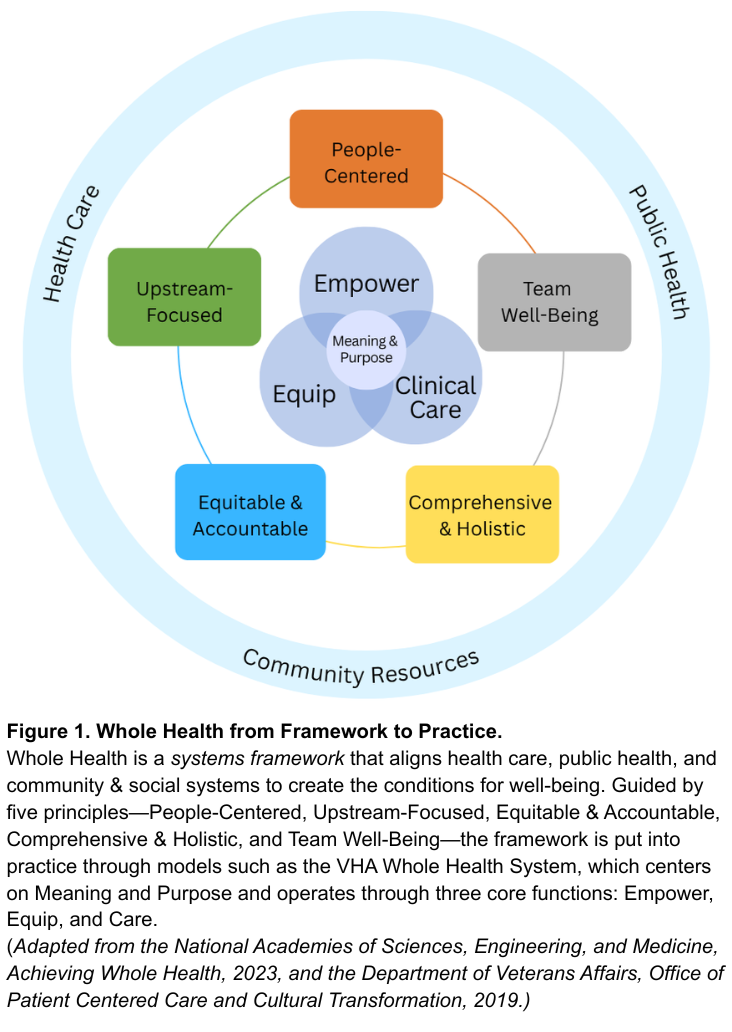

Veterans Health Administration’s Whole Health System Debuted in 2011

Whole Health offers a system-wide redesign for the challenge at hand. As defined by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Whole Health is a framework for organizing how health is created and supported across sectors. It integrates medical care, behavioral health, public health, and community resources. As shown in Figure 1, the framework connects five system principles—People-Centered, Upstream-Focused, Equitable & Accountable, Comprehensive & Holistic, and Team Well-Being–that guide implementation across health and social support systems. The nation’s largest health system, the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA), has demonstrated this framework in clinical practice through their Whole Health System since 2011. The VHA’s Whole Health System operates through three core functions: Empower (helping individuals define purpose), Equip (providing community resources like peer support), and Clinical Care (delivering coordinated, team-based care). Together, these elements align with what matters most to people, shifting the locus of control from expert-driven systems to shared agency through partnerships. The Whole Health System at the VHA has reduced opioid use and improved chronic disease outcomes.

Successful State Examples

Beyond the VHA, states have also demonstrated the possibility and benefits of Whole Health models. North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots extended Medicaid coverage to housing, food, and transportation, showing fewer emergency visits and savings of about $85 per member per month. Vermont’s Blueprint for Health links primary care practices with community health teams and social services, reducing expenditures by about $480 per person annually and boosting preventive screenings. Finally, the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), currently being implemented in 33 states, utilizes both Medicare and Medicaid funding to coordinate medical and social care for older adults with complex medical needs. While improvements can be made to national program-wide evaluation, states like Kansas have done evaluations that have found that the PACE program is less expensive than nursing homes per beneficiary and that nursing home admissions decline by 5% to 15% for beneficiaries.

Success across each of these examples relies on three pillars: (1) integrating medical, behavioral, social, and public health resources; (2) sustainable financing that prioritizes prevention and coordination; and (3) rigorous evaluation of outcomes that matter to people and communities. While these programs are early signs of success of Whole Health models, without coordinated leadership, efforts will fragment into isolated pilots and it will be challenging to learn and evolve.

A policy window for rethinking the health care system is opening. At this national inflection point, the U.S. can work to build a unified Whole Health strategy that enables a more effective, affordable and resilient health system.

Plan of Action

To act on this opportunity, federal and state leaders can take the following coordinated actions to embed Whole Health as a unifying framework across health, social, and wellbeing systems.

Recommendation 1. Declare Whole Health a Federal and State Priority.

Whole Health should become a unifying value across federal and state government action on health and wellbeing, embedding prevention, connection, and integration into how health and social systems are organized, financed, and delivered. Actions include:

- Federal Executive Action. The Executive Office of the President should create a Whole Health Strategic Council that brings together Veterans Affairs (VA), Health and Human Services (e.g. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)), Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to align strategies, budgets, and programs with Whole Health principles through cross-agency guidance and joint planning. This council should also work with Governors to establish evidence-based benchmarks for Whole Health operations and evaluation (e.g., person-centered planning, peer support, team integration) and shared outcome metrics for well-being and population health.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Authorize whole health benefits, like housing assistance, nutrition counseling, transportation to appointments, peer support programs, and well-being centers as reimbursable services under Medicare, Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act health subsidies.

- State Action. Adopt Whole Health models through Medicaid managed-care contracts and through CDC and HRSA grant implementation. States should also develop support for Whole Health services in trusted local settings such as libraries, faith-based organizations, senior centers, to reach people where they live and gather.

Recommendation 2. Realign Financing and Payment to Reward Prevention and Team-Based Care.

Federal payment modalities need to shift from a fee-for-service model toward hybrid value-based models. Models such as per-member-per-month payments with quality incentives, can sustain comprehensive, team-based care while delivering outcomes that matter, like reductions in chronic disease and overall perceived wellbeing. Actions include:

- Federal Executive Action. Expand Advanced Primary Care Management (APCM) payments to include Whole Health teams, including clinicians, peer coaches, and community health workers. Ensure that this funding supports coordination, person-centered planning, and upstream prevention, such as food as medicine programs. Further, CMS can expand reimbursements to community health workers and peer support roles and standardize their scope-of-practice rules across states.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Invest in Medicare and Medicaid innovation programs, such as the CMS Innovation Center (CMMI), that reward prevention and chronic disease reduction. Additionally, expand tools for payment flexibility, through Medicaid waivers and state innovation funds, to help states adapt Whole Health models to local needs.

- State Action. Require Medicaid managed-care contracts to reimburse Whole Health services, particularly in underserved and rural areas, and encourage payers to align benefit designs and performance measures around well-being. States should also leverage their state insurance departments to guide and incentivize private health insurers to adopt Whole Health payment models.

Recommendation 3. Strengthen and Expand the Whole Health Workforce.

Whole Health practice needs a broad team to be successful: clinicians, community health workers, peer coaches, community organizations, nutritionists, and educators. To build this workforce, governments need to modernize training, assess the workforce and workplace quality, and connect the fast-growing well-being sector with health and community systems. Actions include:

- Federal Executive Action. Through VA and HRSA establish Whole Health Workforce Centers of Excellence to develop national curricula, set standards, and disseminate evidence on effective Whole Health team-building. Further, CMS should track workforce outcomes such as retention, burnout, and team integration, and evaluate the benefits for health professionals working in Whole Health systems versus traditional health systems.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Expand CMS Graduate Medical Education Funds and HRSA workforce programs to support Whole Health training, certifications, and placements across clinical and community settings.

- State Action. As a part of initiatives to grow the health workforce, state governments should expand the definition of a “health professional” to include Whole Health practitioners. Further, states can leverage their role as a licensure for professionals by creating a “whole health” licensing process that recognizes professionals that meet evidence-based standards for Whole Health.

Recommendation 4. Build a National Learning and Research Infrastructure.

Whole Health programs across the country are proving effective, but lessons remain siloed. A coordinated national system should link evidence, evaluation, and implementation so that successful models can scale quickly and sustainably.

- Federal Executive Action. Direct the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health, and partner agencies (VA, HUD, USDA) to run pragmatic trials and cost-effectiveness studies of Whole Health interventions that measure well-being across clinical, biomedical, behavioral, and social domains. The federal government should also embed Whole Health frameworks into government-wide research agendas to sustain a culture of evidence-based improvement.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Charter a quasi-governmental entity, modeled on Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), to coordinate Whole Health demonstration sites and research. This new entity should partner with CMMI, HRSA and VA to test Whole Health payment and delivery models under real-world conditions. This entity should also establish an interagency team as well as state network to address payment, regulatory, and privacy barriers identified by sites and pilots.

- State Action. Partner with federal agencies through innovation waivers (e.g. 1115 waivers and 1332 waivers) and learning collaboratives to test Whole Health models and share data across state systems and with the federal government.

Conclusion

The United States spends more on health care than any other nation yet delivers poorer outcomes. Whole Health offers a proven path to reverse this trend, reframing care around prevention, purpose, and integration across health and social systems. Embedding Whole Health as the operating system for America’s health requires three shifts: (1) redefining the purpose from treating disease to optimizing health and well-being; (2) restructuring care to empower, equip, and treat through team-based and community-linked approaches; and (3) rebalancing control from expert-driven systems to partnerships guided by what matters most to people and communities. Federal and state leaders have the opportunity to turn scattered Whole Health pilots to a coordinated national strategy. The cost of inaction is continued fragmentation; the reward of action is a healthier and more resilient nation.

This memo produced as part of Strengthening Pathways to Disease Prevention and Improved Health Outcomes.

Both approaches emphasize caring for people as integrated beings rather than as a collection of diseases, but they differ in scope and application. Whole Person Health, as used by NIH, focuses on the biological, psychological, and behavioral systems within an individual—it is primarily a research framework for understanding health across body systems. Whole Health is a systems framework that extends beyond the individual to include families, communities, and environments. It integrates medical care, behavioral health, public health, and social support around what matters most to each person. In short, Whole Person Health is about how the body and mind work together; Whole Health is about how health, social, and community systems work together to create the conditions for well-being. Policymakers can use Whole Health to guide financing, workforce, and infrastructure reforms that translate Whole Person Health science into everyday practice.

Integrative Health combines evidence-based conventional and complementary approaches such as mindfulness, acupuncture, yoga, and nutrition to support healing of the whole person. Whole Health extends further. It includes prevention, self-care, and personal agency, and moves beyond the clinic to connect medical care with social, behavioral, and community dimensions of health. Whole Health uses integrative approaches when evidence supports them, but it is ultimately a systems model that aligns health, social, and community supports around what matters most to people. For policymakers, it provides a structure for integrating clinical and community services within financing and workforce strategies.

They share a common foundation but differ in scope and audience. The VA Whole Health System, developed by the Department of Veterans Affairs, is an operational model, a way of delivering care that helps veterans identify what matters most, supports self-care and skill building, and provides team-based clinical treatment. The National Academies’ Whole Health framework builds on the VA’s experience and expands it to the national level. It is a policy and systems framework that applies Whole Health principles across all populations and connects health care with public health, behavioral health, and community systems. In short, the VA model shows how Whole Health works in practice, while the National Academies framework shows how it can guide national policy and system alignment.

Improve healthcare data capture at the source to build a learning health system

Studies estimate that only one in 10 recommendations made by major professional societies are supported by high-quality evidence. Medical care that is not evidence-based can result in unnecessary care that burdens public finances, harms patients, and damages trust in the medical profession. Clearly, we must do a better job of figuring out the right treatments, for the right patients, at the right time. To meet this challenge, it is essential to improve our ability to capture reusable data at the point of care that can be used to improve care, discover new treatments, and make healthcare more efficient. To achieve this vision, we will need to shift financial incentives to reward data generation, change how we deliver care using AI, and continue improving the technological standards powering healthcare.

The Challenge and Opportunity of health data

Many have hailed health data collected during everyday healthcare interactions as the solution to some of these challenges. Congress directed the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to increase the use of real-world data (RWD) for making decisions about medical products. However, FDA’s own records show that in the most recent year for which data are available, only two out of over one hundred new drugs and biologics approved by FDA were approved based primarily on real-world data.

A major problem is that our current model in healthcare doesn’t allow us to generate reusable data at the point of care. This is even more frustrating because providers face a high burden of documentation, and patients report repetitive questions from providers and questionnaires.

To expand a bit: while large amounts of data are generated at the point of care, these data lack the quality, standardization, and interoperability to enable downstream functions such as clinical trials, quality improvement, and other ways of generating more knowledge about how to improve outcomes.

By better harnessing the power of data, including results of care, we could finally build a learning healthcare system where outcomes drive continuous improvement and where healthcare value leads the way. There are, however, countless barriers to such a transition. To achieve this vision, we need to develop new strategies for the capture of high-quality data in clinical environments, while reducing the burden of data entry on patients and providers.

Efforts to achieve this vision follow a few basic principles:

- Data should be entered only once– by the person or entity most qualified to do so – and be used many times.

- Data capture should be efficient, so as to minimize the burden on those entering the data, allowing them to focus their time on doing what actually matters, like providing patient care.

- Data generated at the point of care needs to be accessible for appropriate secondary uses (quality improvement, trials, registries), while respecting patient autonomy and obtaining informed consent where required. Data should not be stuck in any one system but should flow freely between systems, enabling linkages across different data sources.

- Data need to be used to provide real value to patients and physicians. This is achieved by developing data visualizations, automated data summaries, and decision support (e.g. care recommendations, trial matching) that allow data users to spend less time searching for data and more time on analysis, problem solving, and patient care– and help them see the value in entering data in the first place.

Barriers to capturing high-quality data at the point of care:

- Incentives: Providers and health systems are paid for performing procedures or logging diagnoses. As a result, documentation is optimized for maximizing reimbursement, but not for maximizing the quality, completeness, and accuracy of data generated at the point of care.

- Workflows: Influenced by the prevailing incentives, clinical workflows are not currently optimized to enable data capture at the point of care. Patients are often asked the same questions at multiple stages, and providers document the care provided as part of free-text notes, which are frequently required for billing but can make it challenging to find information.

- Technology: Shaped by incentives and workflows, technology has evolved to capture information in formats that frequently lack standardization and interoperability.

Plan of Action

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Incentivize generation of reusable data at the point of care

Financial incentives are needed to drive the development of workflows and technology to capture high-quality data at the point of care. There are several payment programs already in existence that could provide a template for how these incentives could be structured.

For example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced the Enhancing Oncology Model (EOM), a voluntary model for oncology providers caring for patients with common cancer types. As part of the EOM, providers are required to report certain data fields to CMS, including staging information and hormone receptor status for certain cancer types. These data fields are essential for clinical care, research, quality improvement, and ongoing care observation involving cancer patients. Yet, at present, these data are rarely recorded in a way that makes it easy to exchange and reuse this information. To reduce the burden of reporting this data, CMS has collaborated with the HHS Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy (ASTP) to develop and implement technological tools that can facilitate automated reporting of these data fields.

CMS also has a long-standing program that requires participation in evidence generation as a prerequisite for coverage, known as coverage with evidence development (CED). For example, hospitals that would like to provide Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) are required to participate in a registry that records data on these procedures.

To incentivize evidence generation as part of routine care, CMS should refine these programs and expand their use. This would involve strengthening collaborations across the federal government to develop technological tools for data capture, and increasing the number of payment models that require generation of data at the point of care. Ideally, these models should evolve to reward 1) high-quality chart preparation (assembly of structured data) 2) establishing diagnoses and development of a care plan, and 3) tracking outcomes. These payment policies are powerful tools because they incentivize the generation of reusable infrastructure that can be deployed for many purposes.

Recommendation 2. Improve workflows to capture evidence at the point of care

With the right payment models, providers can be incentivized to capture reusable data at the point of care. However, providers are already reporting being crushed by the burden of documentation and patients are frequently filling out multiple questionnaires with the same information. To usher in the era of the learning health system (a system that includes continuous data collection to improve service delivery), without increasing the burden on providers and patients, we need to redesign how care is provided. Specifically, we must focus on approaches that integrate generation of reusable data into the provision of routine clinical care.

While the advent of AI is an opportunity to do just that, current uses of AI have mainly focused on drafting documentation in free-text formats, essentially replacing human scribes. Instead, we need to figure out how we can use AI to improve the usability of the resulting data. While it is not feasible to capture all data in a structured format on all patients, a core set of data are needed to provide high-quality and safe care. At a minimum, those should be structured and part of a basic core data set across disease types and health maintenance scenarios.

In order to accomplish this, NIH and the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) should fund learning laboratories that develop, pilot, and implement new approaches for data capture at the point of care. These centers would leverage advances in human-centered design and artificial intelligence (AI) to revolutionize care delivery models for different types of care settings, ranging from outpatient to acute care and intensive care settings. Ideally, these centers would be linked to existing federally funded research sites that could implement the new care and discovery processes in ongoing clinical investigations.

The federal government already spends billions of dollars on grants for clinical research- why not use some of that funding to make clinical research more efficient, and improve the experience of patients and physicians in the process?

Recommendation 3. Enable technology systems to improve data standardization and interoperability

Capturing high-quality data at the point of care is of limited utility if the data remains stuck within individual electronic health record (EHR) installations. Closed systems hinder innovation and prevent us from making the most of the amazing trove of health data.

We must create a vibrant ecosystem where health data can travel seamlessly between different systems, while maintaining patient safety and privacy. This will enable an ecosystem of health data applications to flourish. HHS has recently made progress by agreeing to a unified approach to health data exchange, but several gaps remain. To address these we must

- Increase standardization of data elements: The federal government requires certain data elements to be standardized for electronic export from the EHR. However, this list of data elements, called the United States Core Data for Interoperability (USCDI) currently does not include enough data elements for many uses of health data. HHS could rapidly expand the USCDI by working with federal partners and professional societies to determine which data elements are critical for national priorities, like vaccine safety and use, or protection from emerging pathogens.

- Enable writeback into the EHR: While current efforts focused on interoperability have focused on the ability to export EHR data, developing a vibrant ecosystem of health data applications that are available to patients, physicians, and other data users, requires the capability to write data back into the EHR. This would enable the development of a competitive ecosystem of applications that use health data generated in the EHR, much like the app store on our phones.

- Create widespread interoperability of data for multiple purposes: HHS has made great progress towards allowing health data to be exchanged between any two entities in our healthcare system, thanks to the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA). TEFCA could allow any two healthcare sites to exchange data, but unfortunately, participation remains spotty and TEFCA currently does not allow data exchange solely for research. HHS should work to close these gaps by allowing TEFCA to be used for research, and incentivizing participation in TEFCA, for example by making joining TEFCA a condition of participation in Medicare.

Conclusion

The treasure trove of health data generated during routine care has given us a huge opportunity to generate knowledge and improve health outcomes. These data should serve as a shared resource for clinical trials, registries, decision support, and outcome tracking to improve the quality of care. This is necessary for society to advance towards personalized medicine, where treatments are tailored to biology and patient preference. However, to make the most of these data, we must improve how we capture and exchange these data at the point of care.

Essential to this goal is evolving our current payment systems from rewarding documentation of complexity or time spent, to generation of data that supports learning and improvement. HHS should use its payment authorities to encourage data generation at the point of care and promote the tools that enable health data to flow seamlessly between systems, building on the success stories of existing programs like coverage with evidence development. To allow capture of this data without making the lives of providers and patients even more difficult, federal funding bodies need to invest in developing technologies and workflows that leverage AI to create usable data at the point of care. Finally, HHS must continue improving the standards that allow health data to travel seamlessly between systems. This is essential for creating a vibrant ecosystem of applications that leverage the benefits of AI to improve care.

This memo produced as part of the Federation of American Scientists and Good Science Project sprint. Find more ideas at Good Science Project x FAS

A Quantitative Imaging Infrastructure to Revolutionize AI-Enabled Precision Medicine

Medical imaging, a non-invasive method to detect and characterize disease, stands at a crossroads. With the explosive growth of artificial intelligence (AI), medical imaging offers extraordinary potential for precision medicine yet lacks adequate quality standards to safely and effectively fulfill the promise of AI. Now is the time to create a quantitative imaging (QI) infrastructure to drive the development of precise, data-driven solutions that enhance patient care, reduce costs, and unlock the full potential of AI in modern medicine.

Medical imaging plays a major role in healthcare delivery and is an essential tool in diagnosing numerous health issues and diseases (e.g., oncology, neurology, cardiology, hepatology, nephrology, pulmonary, and musculoskeletal). In 2023, there were more than 607 million imaging procedures in the United States and, per a 2021 study, $66 billion (8.9% of the U.S. healthcare budget) is spent on imaging.

Despite the importance and widespread use of medical imaging like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), X-ray, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), it is rarely standardized or quantitative. This leads to unnecessary costs due to repeat scans to achieve adequate image quality, and unharmonized and uncalibrated imaging datasets, which are often unsuitable for AI/machine learning (ML) applications. In the nascent yet exponentially expanding world of AI in medical imaging, a well-defined standards and metrology framework is required to establish robust imaging datasets for true precision medicine, thereby improving patient outcomes and reducing spiraling healthcare costs.

Challenge and Opportunity

The U.S. spends more on healthcare than any other high-income country yet performs worse on measures of health and healthcare. Research has demonstrated that medical imaging could help save money for the health system with every $1 spent on inpatient imaging resulting in approximately $3 total savings in healthcare delivered. However, to generate healthcare savings and improve outcomes, rigorous quality assurance (QA)/quality control(QC) standards are required for true QI and data integrity.

Today, medical imaging suffers two shortcomings inhibiting AI:

- Lack of standardization: Findings or measurements differ based on numerous factors such as system manufacturer, software version, or imaging protocol.

- A reliance on qualitative (subjective) measurements despite the technological capabilities to perform quantitative (objective) measurements.

Both result in variability impacting assessments and reducing the generalizability of, and confidence in, imaging test results and compromise data quality required for AI applications.

The growing field of QI, however, provides accurate and precise (repeatable and reproducible) quantitative-image-based metrics that are consistent across different imaging devices and over time. This benefits patients (fewer scans, biopsies), doctors, researchers, insurers, and hospitals and enables safe, viable development and use of AI/ML tools.

Quantitative imaging metrology and standards are required as a foundation for clinically relevant and useful QI. A change from “this might be a stage 3 tumor” to “this is a stage 3 tumor” will affect how oncologists can treat a patient. Quantitative imaging also has the potential to remove the need for an invasive biopsy and, in some cases, provide valuable and objective information before even the most expert radiologist’s qualitative assessment. This can mean the difference between taking a nonresponding patient off a toxic chemotherapeutic agent or recognizing a strong positive treatment response before a traditional assessment.

Plan of Action

The incoming administration should develop and fund a Quantitative Imaging Infrastructure to provide medical imaging with a foundation of rigorous QA/QC methodologies, metrology, and standards—all essential for AI applications.

Coordinated leadership is essential to achieve such standardization. Numerous medical, radiological, and standards organizations support and recognize the power of QI and the need for rigorous QA/QC and metrology standards (see FAQs). Currently, no single U.S. organization has the oversight capabilities, breadth, mandate, or funding to effectively implement and regulate QI or a standards and metrology framework.

As set forth below, earlier successful approaches to quality and standards in other realms offer inspiration and guidance for medical imaging and this proposal:

- Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA)

- Mammographic Quality Standards Act of 1992 (MQSA)

- Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) Clinical Standardization Program (CSP)

Recommendation 1. Create a Medical Metrology Center of Excellence for Quantitative Imaging.

Establishing a QI infrastructure would transform all medical imaging modalities and clinical applications. Our recommendation is that an autonomous organization be formed, possibly appended to existing infrastructure, with the mandate and responsibility to develop and operationally support the implementation of quantitative QA/QC methodologies for medical imaging in the age of AI. Specifically this fully integrated QI Metrology Center of Excellence would need federal funding to:

- Define a metrology standards framework, in accord with international metrology standards;

- Implement a standards program to oversee:

- approach to sequence definition

- protocol development

- QA/QC methodology

- QIB profiles

- guidance and standards regarding “digital twins”

- applications related to radiomics

- clinical practice and operations

- vendor-neutral applications (where application is agnostic to manufacturer/machine)

- AI/ML validation

- data standardization

- training and continuing education for doctors and technologists.

Once implemented, the Center could focus on self-sustaining approaches such as testing and services provided for a fee to users.

Similar programs and efforts have resulted in funding (public and private) ranging from $90 million (e.g., Pathogen Genomics Centers of Excellence Network) to $150 million (e.g., Biology and Machine Learning – Broad Institute). Importantly, implementing a QI Center of Excellence would augment and complement federal funding currently being awarded through ARPA-H and the Cancer Moonshot, as neither have an overarching imaging framework for intercomparability between projects.

While this list is by no means exhaustive, any organization would need input and buy-in from:

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) (and related organizations such as National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB))

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC)

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)

- U.S. Department of Defense (DoD)

- Radiological Society of North America (RSNA)

- American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM)

- International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM)

- Society of Nuclear Medicine & Molecular Imaging (SNMMI)

- American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM)

- American College of Radiology (ACR)

- ARPA-H

- HHS

International organizations also have relevant programs, guidance, and insight, including:

- European Society of Radiology (ESR)

- European Association of National Metrology Institutes (EURAMET)

- European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI)

- European Society of Radiology’s Imaging Biomarkers Alliance (EIBALL)

- European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM)

- Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine (IPEM)

- Japan Quantitative Imaging Biomarker Alliance (JQIBA)

- National Physical Laboratory (NPL)

- National Imaging Facility (NIF)

Recommendation 2. Implement legislation and/or regulation providing incentives for standardizing all medical imaging.