Goodbye IRS Direct File, Hello Inefficiency

Decision to Sunset IRS’ Direct File Previews Worse Taxpayer Experience in 2026

Yesterday, tens of thousands of taxpayers filed their returns using IRS Direct File, the agency’s new free, public, online tax filing service now in its second filing season. They joined hundreds of thousands who have used the service, and who have been nearly-unanimously thrilled to fulfill their tax obligations easily and directly. It seems we have finally done the impossible: make Tax Day anything but the most dreaded day of the year. At least we did.

Today, the Associated Press reported that the Treasury Department will discontinue the program. “Cutting costs and saving money for families were just empty campaign promises,” says Adam Ruben, a vice president at the Economic Security Project of the administration’s decision to end the program.

I was an original architect of Direct File from 2021 until just a few months ago, and got to see its impact on government and on taxpayers directly. Make no mistake: Direct File is a shining example of government capacity and government efficiency. By providing a critical government service for free, and helping taxpayers file more timely and more accurate returns, it is projected to eventually generate $11 billion in net savings for taxpayers every year.

The dismantling of the program is not, at all, a step toward government efficiency. This is a move that will degrade our government services, incurring massive costs for people trying to file their taxes, further damaging the capacity of the nation’s revenue-collection agency, and making our institutions less robust and less capable.

It’s no secret: Americans do not love tax season.

The Direct File story started for me, personally, when I moved back to the U.S. after living in London for 9 years. I had already spent years working in digital services: I had built the first in-house digital team at the brand-new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in 2010, and then worked on multiple projects in London, culminating in helping the London Borough of Camden digitally transform its entire operations practically overnight during the pandemic. I moved back to the States and joined the US Digital Service to help rebuild after Covid, bringing the lessons I had learned from the UK. My first project at USDS was leading our efforts on Child Tax Credit expansion — ensuring that families across the country could access the enormous new child benefit that was created in the March 2021 American Rescue Plan.

But there was a problem: families naturally had to file a tax return to claim their tax credit. And I was pretty surprised to learn that our government still did not, in 2021, offer a free, online way to file your taxes directly with the government. Around the world, tax collection is seen as an inherent government function and, as such, tax filing is a service that the government offers free of charge. I thought we should too, especially if we were going to make such critical social supports contingent on it during a crisis.

Instead, in the U.S., we relied on a confusing — and sometimes costly — mishmash of private offerings and support from non-profits designed to ensure most people could maybe, sort of, file a return for free if they needed to. It made the barrier to entry high, both in terms of trying to navigate how to simply file a return, nevermind to do so without cost. Tax filing, I thought, is a core function of government, and making it free and easy to use would cut through this waste and deliver for the American people.

I wasn’t the only one who thought this way. By 2021, a free public filing service was already the “white whale” of civic tech; everyone knew this was the critical government function to bring into a modern digital product, and yet it was too big, too daunting, too much of a change. Honestly, never in a million years did I think we would pull it off, either. The IRS, for all its genuine accomplishments in the face of constantly shrinking budgets and aging technology, had no real experience launching an enormous, high-stakes tech product designed to simplify the mind-numbing complexities of an American tax return. This was government capacity we would have to create.

But, we did. Since Direct File launched as a pilot in March 2023, hundreds of thousands of people have now filed their returns with it, to stunning results. In its pilot year, 86% of users said that Direct File increased their trust in the IRS. In its second year, it is winning awards and killing it with users, with a Net Promoter Score in the +80s, up from +74 last year (Apple’s, which is considered astronomically high, is +72). Direct File is a wildly successful government startup. Not only that, but the IRS now has its own in-house capacity to continue building awesome digital experiences — capacity that could have gone toward cost savings and experience improvements in all matter of IRS operations. This is all capacity, needless to say, that has gone away, all in the name of “efficiency.”

The impact for taxpayers from Direct File alone are, and would have been, enormous. In the U.S., the IRS estimates that it takes the average person over 9 hours and costs $160 to file your taxes each year. We even heard anecdotally from Direct File users who had paid thousands of dollars to do what Direct File does for free. There also remain millions of households who, every year, don’t file their returns at all, leaving sizable refunds on the table, because they can’t navigate the confusing tax filing “offers” advertising tax filing services. These households would have stood to finally access billions of dollars they leave unclaimed every year.

Not only are taxpayers saving these hundreds of dollars, they also feel newly empowered to interact with their government and take control of their tax situations. For decades, Americans have been told that they are not smart enough to do your own taxes; only highly-paid specialists that you have to pay for, can do it for you. Direct File stripped away the noise and showed taxpayers that filing can be simple and easy. The valuable trust this creates in government and public institutions is impossible to quantify.

Finally, there is the issue of data privacy and security. Taxpayers filing via private services must expose their most sensitive personal and financial information to third parties that monetize their data, sometimes illegally and without taxpayers’ consent. Without a public filing option, taxpayers are more or less required to sacrifice their privacy and the security of their data just to fulfill their filing obligations. Direct File gives taxpayers the option to protect their data and provide it straight to the tax agency, without a middleman.

All this — the in-house capacity to modernize the IRS, billions of dollars in cost savings, an empowered public — is what is cancelled today. But they have it exactly backwards. It’s a functional, high-quality government that’s efficient. The chaos they are sowing is anything but.

Reforming the Federal Advisory Committee Landscape for Improved Evidence-based Decision Making and Increasing Public Trust

Federal Advisory Committees (FACs) are the single point of entry for the American public to provide consensus-based advice and recommendations to the federal government. These Advisory Committees are composed of experts from various fields who serve as Special Government Employees (SGEs), attending committee meetings, writing reports, and voting on potential government actions.

Advisory Committees are needed for the federal decision-making process because they provide additional expertise and in-depth knowledge for the Agency on complex topics, aid the government in gathering information from the public, and allow the public the opportunity to participate in meetings about the Agency’s activities. As currently organized, FACs are not equipped to provide the best evidence-based advice. This is because FACs do not meet transparency requirements set forth by GAO: making pertinent decisions during public meetings, reporting inaccurate cost data, providing official meeting documents publicly available online, and more. FACs have also experienced difficulty with recruiting and retaining top talent to assist with decision making. For these reasons, it is critical that FACs are reformed and equipped with the necessary tools to continue providing the government with the best evidence-based advice. Specifically, advice as it relates to issues such as 1) decreasing the burden of hiring special government employees 2) simplifying the financial disclosure process 3) increasing understanding of reporting requirements and conflict of interest processes 4) expanding training for Advisory Committee members 5) broadening the roles of Committee chairs and designated federal officials 6) increasing public awareness of Advisory Committee roles 7) engaging the public outside of official meetings 8) standardizing representation from Committee representatives 9) ensuring that Advisory Committees are meeting per their charters and 10) bolstering Agency budgets for critical Advisory Committee issues.

Challenge and Opportunity

Protecting the health and safety of the American public and ensuring that the public has the opportunity to participate in the federal decision-making process is crucial. We must evaluate the operations and activities of federal agencies that require the government to solicit evidence-based advice and feedback from various experts through the use of federal Advisory Committees (FACs). These Committees are instrumental in facilitating transparent and collaborative deliberation between the federal government, the advisory body, and the American public and cannot be done through the use of any other mechanism. Advisory Committee recommendations are integral to strengthening public trust and reinforcing the credibility of federal agencies. Nonetheless, public trust in government has been waning and efforts should be made to increase public trust. Public trust is known as the pillar of democracy and fosters trust between parties, particularly when one party is external to the federal government. Therefore, the use of Advisory Committees, when appropriately used, can assist with increasing public trust and ensuring compliance with the law.

There have also been many success stories demonstrating the benefits of Advisory Committees. When Advisory Committees are appropriately staffed based on their charge, they can decrease the workload of federal employees, assist with developing policies for some of our most challenging issues, involve the public in the decision-making process, and more. However, the state of Advisory Committees and the need for reform have been under question, and even more so as we transition to a new administration. Advisory Committees have contributed to the improvement in the quality of life for some Americans through scientific advice, as well as the monitoring of cybersecurity. For example, an FDA Advisory Committee reviewed data and saw promising results for the treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD) which has been a debilitating disease with limited treatment for years. The Committee voted in favor of gene therapy drugs Casgevy and Lyfgenia which were the first to be approved by the FDA for SCD.

Under the first Trump administration, Executive Order (EO) 13875 resulted in a significant decrease in the number of federal advisory meetings. This limited agencies’ ability to convene external advisors. Federal science advisory committees met less during this administration than any prior administration, met less than what was required from their charter, disbanded long standing Advisory Committees, and scientists receiving agency grants were barred from serving on Advisory Committees. Federal Advisory Committee membership also decreased by 14%, demonstrating the issue of recruiting and retaining top talent. The disbandment of Advisory Committees, exclusion of key scientific external experts from Advisory Committees, and burdensome procedures can potentially trigger severe consequences that affect the health and safety of Americans.

Going into a second Trump administration, it is imperative that Advisory Committees have the opportunity to assist federal agencies with the evidence-based advice needed to make critical decisions that affect the American public. The suggested reforms that follow can work to improve the overall operations of Advisory Committees while still providing the government with necessary evidence-based advice. With successful implementation of the following recommendations, the federal government will be able to reduce administrative burden on staff through the recruitment, onboarding, and conflict of interest processes.

The U.S. Open Government Initiative encourages the promotion and participation of public and community engagement in governmental affairs. However, individual Agencies can and should do more to engage the public. This policy memo identifies several areas of potential reform for Advisory Committees and aims to provide recommendations for improving the overall process without compromising Agency or Advisory Committee membership integrity.

Plan of Action

The proposed plan of action identifies several policy recommendations to reform the federal Advisory Committee (Advisory Committee) process, improving both operations and efficiency. Successful implementation of these policies will 1) improve the Advisory Committee member experience, 2) increase transparency in federal government decision-making, and 3) bolster trust between the federal government, its Advisory Committees, and the public.

Streamline Joining Advisory Committees

Recommendation 1. Decrease the burden of hiring special government employees in an effort to (1) reduce the administrative burden for the Agency and (2) encourage Advisory Committee members, who are also known as special government employees (SGEs), to continue providing the best evidence-based advice to the federal government through reduced onerous procedures

The Ethics in Government Act of 1978 and Executive Order 12674 lists OGE-450 reporting as the required public financial disclosure for all executive branch and special government employees. This Act provides the Office of Government Ethics (OGE) the authority to implement and regulate a financial disclosure system for executive branch and special government employees whose duties have “heightened risk of potential or actual conflicts of interest”. Nonetheless, the reporting process becomes onerous when Advisory Committee members have to complete the OGE-450 before every meeting even if their information remains unchanged. This presents a challenge for Advisory Committee members who wish to continue serving, but are burdened by time constraints. The process also burdens federal staff who manage the financial disclosure system.

Policy Pathway 1. Increase funding for enhanced federal staffing capacity to undertake excessive administrative duties for financial reporting.

Policy Pathway 2. All federal agencies that deploy Advisory Committees can conduct a review of the current OGC-450 process, budget support for this process, and work to develop an electronic process that will eliminate the use of forms and allow participants to select dropdown options indicating if their financial interests have changed.

Recommendation 2. Create and use public platforms such as OpenPayments by CMS to (1) aid in simplifying the financial disclosure reporting process and (2) increase transparency for disclosure procedures

Federal agencies should create a financial disclosure platform that streamlines the process and allows Advisory Committee members to submit their disclosures and easily make updates. This system should also be created to monitor and compare financial conflicts. In addition, agencies that utilize the expertise of Advisory Committees for drugs and devices should identify additional ways in which they can promote financial transparency. These agencies can use Open Payments, a system operated by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), to “promote a more financially transparent and accountable healthcare system”. The Open Payments system makes payments from medical and drug device companies to individuals, healthcare providers, and teaching hospitals accessible to the public. If for any reason financial disclosure forms are called into question, the Open Payments platform can act as a check and balance in identifying any potential financial interests of Advisory Committee members. Further steps that can be taken to simplify the financial disclosure process would be to utilize conflict of interest software such as Ethico which is a comprehensive tool that allows for customizable disclosure forms, disclosure analytics for comparisons, and process automation.

Policy Pathway. The Office of Government Ethics should require all federal agencies that operate Advisory Committees to develop their own financial disclosure system and include a second step in the financial disclosure reporting process as due diligence, which includes reviewing the Open Payments by CMS system for potential financial conflicts or deploying conflict of interest monitoring software to streamline the process.

Streamline Participation in an Advisory Committee

Recommendation 3. Increase understanding of annual reporting requirements for conflict of interest (COI)

Agencies should develop guidance that explicitly states the roles of Ethics Officers, also known as Designated Agency Ethics Officials (DAEO), within the federal government. Understanding the roles and responsibilities of Advisory Committee members and the public will help reduce the spread of misinformation regarding the purpose of Advisory Committees. In addition, agencies should be encouraged by the Office of Government Ethics to develop guidance that indicates the criteria for inclusion or exclusion of participation in Committee meetings. Currently, there is no public guidance that states what types of conflicts of interests are granted waivers for participation. Full disclosure of selection and approval criteria will improve transparency with the public and draw clear delineations between how Agencies determine who is eligible to participate.

Policy Pathway. Develop conflict of interest (COI) and financial disclosure guidance specifically for SGEs that states under what circumstances SGEs are allowed to receive waivers for participation in Advisory Committee meetings.

Recommendation 4. Expand training for Advisory Committee members to include (1) ethics and (2) criteria for making good recommendations to policymakers

Training should be expanded for all federal Advisory Committee members to include ethics training which details the role of Designated Agency Ethics Officials, rules and regulations for financial interest disclosures, and criteria for making evidence-based recommendations to policymakers. Training for incoming Advisory Committee members ensures that all members have the same knowledge base and can effectively contribute to the evidence-based recommendations process.

Policy Pathway. Agencies should collaborate with the OGE and Agency Heads to develop comprehensive training programs for all incoming Advisory Committee members to ensure an understanding of ethics as contributing members, best practices for providing evidence-based recommendations, and other pertinent areas that are deemed essential to the Advisory Committee process.

Leverage Advisory Committee Membership

Recommendation 5. Uplifting roles of the Committee Chairs and Designated Federal Officials

Expanding the roles of Committee Chairs and Designated Federal Officers (DFOs) may assist federal Agencies with recruiting and retaining top talent and maximizing the Committee’s ability to stay abreast of critical public concerns. Considering the fact that the General Services Administration has to be consulted for the formation of new Committees, renewal, or alteration of Committees, they can be instrumental in this change.

Policy Pathway. The General Services Administration (GSA) should encourage federal Agencies to collaborate with Committee Chairs and DFOs to recruit permanent and ad hoc Committee members who may have broad network reach and community ties that will bolster trust amongst Committees and the public.

Recommendation 6. Clarify intended roles for Advisory Committee members and the public

There are misconceptions among the public and Advisory Committee members about Advisory Committee roles and responsibilities. There is also ambiguity regarding the types of Advisory Committee roles such as ad hoc members, consulting, providing feedback for policies, or making recommendations.

Policy Pathway. GSA should encourage federal Agencies to develop guidance that delineates the differences between permanent and temporary Advisory Committee members, as well as their roles and responsibilities depending on if they’re providing feedback for policies or providing recommendations for policy decision-making.

Recommendation 7. Utilize and engage expertise and the public outside of public meetings

In an effort to continue receiving the best evidence-based advice, federal Agencies should develop alternate ways to receive advice outside of public Committee meetings. Allowing additional opportunities for engagement and feedback from Committee experts or the public will allow Agencies to expand their knowledge base and gather information from communities who their decisions will affect.

Policy Pathway. The General Services Administration should encourage federal Agencies to create opportunities outside of scheduled Advisory Committee meetings to engage Committee members and the public on areas of concern and interest as one form of engagement.

Recommendation 8. Standardize representation from Committee representatives (i.e., industry), as well as representation limits

The Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) does not specify the types of expertise that should be represented on all federal Advisory Committees, but allows for many types of expertise. Incorporating various sets of expertise that are representative of the American public will ensure the government is receiving the most accurate, innovative, and evidence-based recommendations for issues and products that affect Americans.

Policy Pathway. Congress should include standardized language in the FACA that states all federal Advisory Committees should include various sets of expertise depending on their charge. This change should then be enforced by the GSA.

Support a Vibrant and Functioning Advisory Committee System

Recommendation 9. Decrease the burden to creating an Advisory Committee and make sure Advisory Committees are meeting per their charters

The process to establish an Advisory Committee should be simplified in an effort to curtail the amount of onerous processes that lead to a delay in the government receiving evidence based advice.

Advisory Committee charters state the purpose of Advisory Committees, their duties, and all aspirational aspects. These charters are developed by agency staff or DFOs with consultation from their agency Committee Management Office. Charters are needed to forge the path for all FACs.

Policy Pathway. Designated Federal Officers (DFOs) within federal agencies should work with their Agency head to review and modify steps to establishing FACs. Eliminate the requirement for FACs to require consultation and/or approval from GSA for the formation, renewal, or alteration of Advisory Committees.

Recommendation 10. Bolster agency budgets to support FACs on critical issues where regular engagement and trust building with the public is essential for good policy

Federal Advisory Committees are an essential component to receive evidence-based recommendations that will help guide decisions at all stages of the policy process. These Advisory Committees are oftentimes the single entry point external experts and the public have to comment and participate in the decision-making process. However, FACs take considerable resources to operate depending on the frequency of meetings, the number of Advisory Committee members, and supporting FDA staff. Without proper appropriations, they have a diminished ability to recruit and retain top talent for Advisory Committees. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that in 2019, approximately $373 million dollars was spent to operate a total of 960 federal Advisory Committees. Some Agencies have experienced a decrease in the number of Advisory Committee convenings. Individual Agency heads should conduct a budget review of average operating and projected costs and develop proposals for increased funding to submit to the Appropriations Committee.

Policy Pathway. Congress should consider increasing appropriations to support FACs so they can continue to enhance federal decision-making, improve public policy, boost public credibility, and Agency morale.

Conclusion

Advisory Committees are necessary to the federal evidence-based decision-making ecosystem. Enlisting the advice and recommendations of experts, while also including input from the American public, allows the government to continue making decisions that will truly benefit its constituents. Nonetheless, there are areas of FACs that can be improved to ensure it continues to be a participatory, evidence-based process. Additional funding is needed to compensate the appropriate Agency staff for Committee support, provide potential incentives for experts who are volunteering their time, and finance other expenditures.

With reform of Advisory Committees, the process for receiving evidence-based advice will be streamlined, allowing the government to receive this advice in a faster and less burdensome manner. Reform will be implemented by reducing the administrative burden for federal employees through the streamlining of recruitment, financial disclosure, and reporting processes.

A Federal Center of Excellence to Expand State and Local Government Capacity for AI Procurement and Use

The administration should create a federal center of excellence for state and local artificial intelligence (AI) procurement and use—a hub for expertise and resources on public sector AI procurement and use at the state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) government levels. The center could be created by expanding the General Services Administration’s (GSA) existing Artificial Intelligence Center of Excellence (AI CoE). As new waves of AI technologies enter the market, shifting both practice and policy, such a center of excellence would help bridge the gap between existing federal resources on responsible AI and the specific, grounded challenges that individual agencies face. In the decades ahead, new AI technologies will touch an expanding breadth of government services—including public health, child welfare, and housing—vital to the wellbeing of the American people. An AI CoE federal center would equip public sector agencies with sustainable expertise and set a consistent standard for practicing responsible AI procurement and use. This resource ensures that AI truly enhances services, protects the public interest, and builds public trust in AI-integrated state and local government services.

Challenge and Opportunity

State, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) governments provide services that are critical to the welfare of our society. Among these: providing housing, child support, healthcare, credit lending, and teaching. SLTT governments are increasingly interested in using AI to assist with providing these services. However, they face immense challenges in responsibly procuring and using new AI technologies. While grappling with limited technical expertise and budget constraints, SLTT government agencies considering or deploying AI must navigate data privacy concerns, anticipate and mitigate biased model outputs, ensure model outputs are interpretable to workers, and comply with sector-specific regulatory requirements, among other responsibilities.

The emergence of foundation models (large AI systems adaptable to many different tasks) for public sector use exacerbates these existing challenges. Technology companies are now rapidly developing new generative AI services tailored towards public sector organizations. For example, earlier this year, Microsoft announced that Azure OpenAI Service would be newly added to Azure Government—a set of AI services that target government customers. These types of services are not specifically created for public sector applications and use contexts, but instead are meant to serve as a foundation for developing specific applications.

For SLTT government agencies, these generative AI services blur the line between procurement and development: Beyond procuring specific AI services, we anticipate that agencies will increasingly be tasked with the responsible use of general AI services to develop specific AI applications. Moreover, recent AI regulations suggest that responsibility and liability for the use and impacts of procured AI technologies will be shared by the public sector agency that deploys them, rather than just resting with the vendor supplying them.

SLTT agencies must be well-equipped with responsible procurement practices and accountability mechanisms pivotal to moving forward given the shifts across products, practice, and policy. Federal agencies have started to provide guidelines for responsible AI procurement (e.g., Executive Order 13960, OMB-M-21-06, NIST RMF). But research shows that SLTT governments need additional support to apply these resources.: Whereas existing federal resources provide high-level, general guidance, SLTT government agencies must navigate a host of challenges that are context-specific (e.g., specific to regional laws, agency practices, etc.). SLTT government agency leaders have voiced a need for individualized support in accounting for these context-specific considerations when navigating procurement decisions.

Today, private companies are promising state and local government agencies that using their AI services can transform the public sector. They describe diverse potential applications, from supporting complex decision-making to automating administrative tasks. However, there is minimal evidence that these new AI technologies can improve the quality and efficiency of public services. There is evidence, on the other hand, that AI in public services can have unintended consequences, and when these technologies go wrong, they often worsen the problems they are aimed at solving. For example, by increasing disparities in decision-making when attempting to reduce them.

Challenges to responsible technology procurement follow a historical trend: Government technology has frequently been critiqued for failures in the past decades. Because public services such as healthcare, social work, and credit lending have such high stakes, failures in these areas can have far-reaching consequences. They also entail significant financial costs, with millions of dollars wasted on technologies that ultimately get abandoned. Even when subpar solutions remain in use, agency staff may be forced to work with them for extended periods despite their poor performance.

The new administration is presented with a critical opportunity to redirect these trends. Training each relevant individual within SLTT government agencies, or hiring new experts within each agency, is not cost- or resource-effective. Without appropriate training and support from the federal government, AI adoption is likely to be concentrated in well-resourced SLTT agencies, leaving others with fewer resources (and potentially more low income communities) behind. This could lead to disparate AI adoption and practices among SLTT agencies, further exacerbating existing inequalities. The administration urgently needs a plan that supports SLTT agencies in learning how to handle responsible AI procurement and use–to develop sustainable knowledge about how to navigate these processes over time—without requiring that each relevant individual in the public sector is trained. This plan also needs to ensure that, over time, the public sector workforce is transformed in their ability to navigate complicated AI procurement processes and relationships—without requiring constant retraining of new waves of workforces.

In the context of federal and SLTT governments, a federal center of excellence for state and local AI procurement would accomplish these goals through a “hub and spoke” model. This center of excellence would serve as the “hub” that houses a small number of selected experts from academia, non-profit organizations, and government. These experts would then train “spokes”—existing state and local public sector agency workers—in navigating responsible procurement practices. To support public sector agencies in learning from each others’ practices and challenges, this federal center of excellence could additionally create communication channels for information- and resource-sharing across the state and local agencies.

Procured AI technologies in government will serve as the backbone of local public services for decades to come. Upskilling government agencies to make smart decisions about which AI technologies to procure (and which are best avoided) would not only protect the public from harmful AI systems but would also save the government money by decreasing the likelihood of adopting expensive AI technologies that end up getting dropped.

Plan of Action

A federal center of excellence for state and local AI procurement would ensure that procured AI technologies are responsibly selected and used to serve as a strong and reliable backbone for public sector services. This federal center of excellence can support both intra-agency and inter-agency capacity-building and learning about AI procurement and use—that is, mechanisms to support expertise development within a given public sector agency and between multiple public sector agencies. This federal center of excellence would not be deliberative (i.e., SLTT governments would receive guidance and support but would not have to seek approval on their practices). Rather, the goal would be to upskill SLTT agencies so they are better equipped to navigate their own AI procurement and use endeavors.

To upskill SLTT agencies through inter-agency capacity-building, the federal center of excellence would house experts in relevant domain areas (e.g., responsible AI, public interest technology, and related topics). Fellows would work with cohorts of public sector agencies to provide training and consultation services. These fellows, who would come from government, academia, and civil society, would build on their existing expertise and experiences with responsible AI procurement, integrating new considerations proposed by federal standards for responsible AI (e.g., Executive Order 13960, OMB-M-21-06, NIST RMF). The fellows would serve as advisors to help operationalize these guidelines into practical steps and strategies, helping to set a consistent bar for responsible AI procurement and use practices along the way.

Cohorts of SLTT government agency workers, including existing agency leaders, data officers, and procurement experts, would work together with an assigned advisor to receive consultation and training support on specific tasks that their agency is currently facing. For example, for agencies or programs with low AI maturity or familiarity (e.g., departments that are beginning to explore the adoption of new AI tools), the center of excellence can help navigate the procurement decision-making process, help them understand their agency-specific technology needs, draft procurement contracts, select amongst proposals, and negotiate plans for maintenance. For agencies and programs with high AI maturity or familiarity, the advisor can train the programs about unexpected AI behaviors and mitigation strategies, when this arises. These communication pathways would allow federal agencies to better understand the challenges state and local governments face in AI procurement and maintenance, which can help seed ideas for improving existing resources and create new resources for AI procurement support.

To scaffold intra-agency capacity-building, the center of excellence can build the foundations for cross-agency knowledge-sharing. In particular, it would include a communication platform and an online hub of procurement resources, both shared amongst agencies. The communication platform would allow state and local government agency leaders who are navigating AI procurement to share challenges, learned lessons, and tacit knowledge to support each other. The online hub of resources can be collected by the center of excellence and SLTT government agencies. Through the online hub, agencies can upload and learn about new responsible AI resources and toolkits (e.g., such as those created by government and the research community), as well as examples of procurement contracts that agencies themselves used.

To implement this vision, the new administration should expand the U.S. General Services Administration’s (GSA) existing Artificial Intelligence Center of Excellence (AI CoE), which provides resources and infrastructural support for AI adoption across the federal government. We propose expanding this existing AI CoE to include the components of our proposed center of excellence for state and local AI procurement and use. This would direct support towards SLTT government agencies—which are currently unaccounted for in the existing AI CoE—specifically via our proposed capacity-building model.

Over the next 12 months, the goals of expanding the AI CoE would be three-fold:

1. Develop the core components of our proposed center of excellence within the AI CoE.

- Recruit a core set of fellows with expertise in responsible AI, public interest technology, and related topics from government, academia, and civil society for a 1-2 year placement;

- Develop a centralized onboarding and training program for the fellows to set standards for responsible AI procurement and use guidelines and goals;

- Create a research strategy to streamline documentation of SLTT agencies’ on-the-ground practices and challenges for procuring new AI technologies, which could help prepare future fellows.

2. Launch collaborations for the first sample of SLTT government agencies. Focus on building a path for successful collaborations:

- Identify a small set of state and local government agencies who desire federal support in navigating AI procurement and use (e.g., deciding which AI use cases to adopt, how to effectively evaluate AI deployments through time, what organizational policies to create to help govern AI use);

- Ensure there is a clear communication pathway between the agency and their assigned fellow;

- Have each fellow and agency pair create a customized plan of action to ensure the agency is upskilled in their ability to independently navigate AI procurement and use with time.

3. Build a path for our proposed center of excellence to grow and gain experience. If the first few collaborations show strong reviews, design a scaling strategy that will:

- Incorporate the center of excellence’s core budget into future budget planning;

- Identify additional fellows for the program;

- Roll out the program to additional state and local government agencies.

Conclusion

Expanding the existing AI CoE to include our proposed federal center of excellence for AI procurement and use can help ensure that SLTT governments are equipped to make informed, responsible decisions about integrating AI technologies into public services. This body would provide necessary guidance and training, helping to bridge the gap between high-level federal resources and the context-specific needs of SLTT agencies. By fostering both intra-agency and inter-agency capacity-building for responsible AI procurement and use, this approach builds sustainable expertise, promotes equitable AI adoption, and protects public interest. This ensures that AI enhances—rather than harms—the efficiency and quality of public services. As new waves of AI technologies continue to enter the public sector, touching a breadth of services critical to the welfare of the American people, this center of excellence will help maintain high standards for responsible public sector AI for decades to come.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Federal agencies have published numerous resources to support responsible AI procurement, including the Executive Order 13960, OMB-M-21-06, NIST RMF. Some of these resources provide guidance on responsible AI development in organizations broadly, across the public, private, and non-profit sectors. For example, the NIST RMF provides organizations with guidelines to identify, assess, and manage risks in AI systems to promote the deployment of more trustworthy and fair AI systems. Others focus on public sector AI applications. For instance, the OMB Memorandum published by the Office of Management and Budget describes strategies for federal agencies to follow responsible AI procurement and use practices.

Research describes how these forms of resources often require additional skills and knowledge that make it challenging for agencies to effectively use on their own. A federal center of excellence for state and local AI procurement could help agencies learn to use these resources. Adapting these guidelines to specific SLTT agency contexts necessitates a careful task of interpretation which may, in turn, require specialized expertise or resources. The creation of this federal center of excellence to guide responsible SLTT procurement on-the-ground can help bridge this critical gap. Fellows in the center of excellence and SLTT procurement agencies can build on this existing pool of guidance to build a strong theoretical foundation to guide their practices.

The hub and spoke model has been used across a range of applications to support efficient management of resources and services. For instance, in healthcare, providers have used the hub and spoke model to organize their network of services; specialized, intensive services would be located in “hub” healthcare establishments whereas secondary services would be provided in “spoke” establishments, allowing for more efficient and accessible healthcare services. Similar organizational networks have been followed in transportation, retail, and cybersecurity. Microsoft follows a hub and spoke model to govern responsible AI practices and disseminate relevant resources. Microsoft has a single centralized “hub” within the company that houses responsible AI experts—those with expertise on the implementation of the company’s responsible AI goals. These responsible AI experts then train “spokes”—workers residing in product and sales teams across the company, who learn about best practices and support their team in implementing them.

During the training, experts would form a stronger foundation for (1) on-the-ground challenges and practices that public sector agencies grapple with when developing, procuring, and using AI technologies and (2) existing AI procurement and use guidelines provided by federal agencies. The content of the training would be taken from syntheses of prior research on public sector AI procurement and use challenges, as well as existing federal resources available to guide responsible AI development. For example, prior research has explored public sector challenges to supporting algorithmic fairness and accountability and responsible AI design and adoption decisions, amongst other topics.

The experts who would serve as fellows for the federal center of excellence would be individuals with expertise and experience studying the impacts of AI technologies and designing interventions to support more responsible AI development, procurement, and use. Given the interdisciplinary nature of the expertise required for the role, individuals should have an applied, socio-technical background on responsible AI practices, ideally (but not necessarily) for the public sector. The individual would be expected to have the skills needed to share emerging responsible AI practices, strategies, and tacit knowledge with public sector employees developing or procuring AI technologies. This covers a broad range of potential backgrounds.

For example, a professor in academia who studies how to develop public sector AI systems that are more fair and aligned with community needs may be a good fit. A socio-technical researcher in civil society with direct experience studying or developing new tools to support more responsible AI development, who has intuition over which tools and practices may be more or less effective, may also be a good candidate. A data officer in a state government agency who has direct experience procuring and governing AI technologies in their department, with an ability to readily anticipate AI-related challenges other agencies may face, may also be a good fit. The cohort of fellows should include a balanced mix of individuals coming from government, academia, and civil society.

Solutions for an Efficient and Effective Federal Permitting Workforce

The United States faces urgent challenges related to aging infrastructure, vulnerable energy systems, and economic competitiveness. Improving American competitiveness, security, and prosperity depends on private and public stakeholders’ ability to responsibly site, build, and deploy critical energy and infrastructure. Unfortunately, these projects face one common bottleneck: permitting.

Permits and authorizations are required for the use of land and other resources under a series of laws, such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. However, recent court rulings and the Trump Administration’s executive actions have brought uncertainty and promise major disruption to the status quo. The Executive Order (EO) on Unleashing American Energy mandates guidance to agencies on permitting processes be expedited and simplified within 30 days, requires agencies prioritize efficiency and certainty over any other objectives, and revokes the Council of Environmental Quality’s (CEQ) authority to issue binding NEPA regulations. While these changes aim to advance the speed, efficiency, and certainty of permitting, the impact will ultimately depend on implementation by the permitting workforce.

Unfortunately, the permitting workforce is unprepared to swiftly implement changes following shifts in environmental policy and regulations. Teams responsible for permitting have historically been understaffed, overworked, and unable to complete their project backlogs, while demands for permits have increased significantly in recent years. Building workforce capacity is critical for efficient and effective federal permitting.

Project Overview

Our team at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has spent 18 months studying and working to build government capacity for permitting talent. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provided resources to expand the federal permitting workforce, and we partnered with the Permitting Council, which serves as a central body to improve the transparency, predictability, and accountability of the federal environmental review and authorization process, to gain a cross-agency understanding of the hiring challenges experienced in permitting agencies and prioritize key challenges to address. Through two co-hosted webinars for hiring managers, HR specialists, HR leaders, and program leaders within permitting agencies, we shared tactical solutions to improve the hiring process.

We complemented this understanding with voices from agencies (i.e., hiring managers, HR specialists, HR teams, and leaders) by conducting interviews to identify new issues, best practices, and successful strategies for building talent capacity. With this understanding, we developed long-term solutions to build a sustainable, federal permitting workforce for the future. While many of our recommendations are focused on permitting talent specifically, our work naturally uncovered challenges within the broader federal talent ecosystem. As such, we’ve included recommendations to advance federal talent systems and improve federal hiring.

Problem

Building permitting talent capacity across the federal government is not an easy endeavor. There are many stakeholders involved across different agencies with varying levels of influence who need to play a role: the Permitting Council staff, the Permitting Council members-represented by Deputy Secretaries (Deputy Secretaries) of permitting agencies, the Chief Environmental Review and Permitting Officers (CERPOs) in each agency, the Office of Personnel and Management (OPM), the Chief Human Capital Officer (CHCO) in each permitting agency, agency HR teams, agency permitting teams, hiring managers, and HR specialists. Permitting teams and roles are widely dispersed across agencies, regions, states, and programs. The role each agency plays in permitting varies based on their mission and responsibilities, and there are many silos within the broader ecosystem. Few have a holistic view of permitting activities and the permitting workforce across the federal government.

With this complex network of actors, one challenge that arises is a lack of standardization and consistency in both roles and teams across agencies. If agencies are looking to fill specialized roles unique to one permitting need, it means that there will be less opportunity for collaboration and for building efficiencies across the ecosystem. The federal hiring process is challenging, and there are many known bottlenecks that cause delays. If agencies don’t leverage opportunities to work together, these bottlenecks will multiply, impacting staff who need to hire and especially permitting and/or HR teams who are understaffed, which is not uncommon. Additionally, building applicant pools to have access to highly qualified candidates is time consuming and not scalable without more consistency.

Tracking workforce metrics and hiring progress is critical to informing these talent decisions. Yet, the tools available today are insufficient for understanding and identifying gaps in the federal permitting workforce. The uncertainty of long-term, sustainable funding for permitting talent only adds more complexity into these talent decisions. While there are many challenges, we have identified solutions that stakeholders within this ecosystem can take to build the permitting workforce for the future.

There are six key recommendations for addressing permitting workforce capacity outlined in the table below. Each is described in detail with corresponding actions in the Solutions section that follows. Our recommendations are for the Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, and Congress.

Solutions

The six solutions described below include an explanation of the problem and key actions our signal stakeholders (Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, and Congress) can take to build permitting workforce capacity. The table in the appendix specifies the stakeholders responsible for each recommendation.

Enhance the Permitting Council’s Authority to Improve Permitting Processes and Workforce Collaboration

Permitting process, performance, and talent management cut across agencies and their bureaus—but their work is often disaggregated by agency and sub-agency, leading to inefficient and unnecessarily discrete practices. While the Permitting Council plays a critical coordinating role, it lacks the authority and accountability to direct and guide better permitting outcomes and staffing. There is no central authority for influencing and mandating permitting performance. Agency-level CERPOs vary widely in their authority, whereas the Permitting Council is uniquely positioned for this role. Choosing to overlook this entity will lead to another interagency workaround. Congress needs to give the Permitting Council staff greater authority to improve permitting processes and workforce collaboration.

- Enhance Permitting Council Authority for Improved Performance: Enhance provisions in FAST-41 and IRA by passing legislation that empowers the Permitting Council staff to create and enforce consistent performance criteria for permitting outcomes, permitting process metrics, permitting talent acquisition, talent management, and permitting teams KPIs.

- Enhance Permitting Council Authority for Interagency Coordination: Empower the Permitting Council staff to manage interagency coordination and collaboration for defining permitting best practices, establishing frameworks for permitting, and reinforcing those frameworks across agencies. Clarify the roles and responsibilities between Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, and the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ).

- Assign Responsibility for Tracking Changes and Providing Guidance for Permitting Practices: Assign the Permitting Council staff in coordination with OMB responsibility for tracking changes and providing guidance on permitting practices in response to recent and ongoing court rulings that change how permitting outcomes are determined (e.g., Loper Bright/Chevron Deference, CEQ policies, etc.).

- Provide Permitting Council staff with Consistent Funding: Either renew components of IRA and/or IIJA funding that enables the Council to invest in agency technologies, hiring, and workforce development, or provide consistent appropriations for this.

- Enhance CERPO Authority and Position CERPOs for Agency-Wide and Cross-Agency Permitting Actions: Expand CERPO authority beyond the FAST-41 Act to include all permitting work within their agency. Through legislation, policy, and agency-level reporting relationships (e.g., CERPO roles assigned to the Secretary’s office), provide CERPOs with clear authority and accountability for permitting performance.

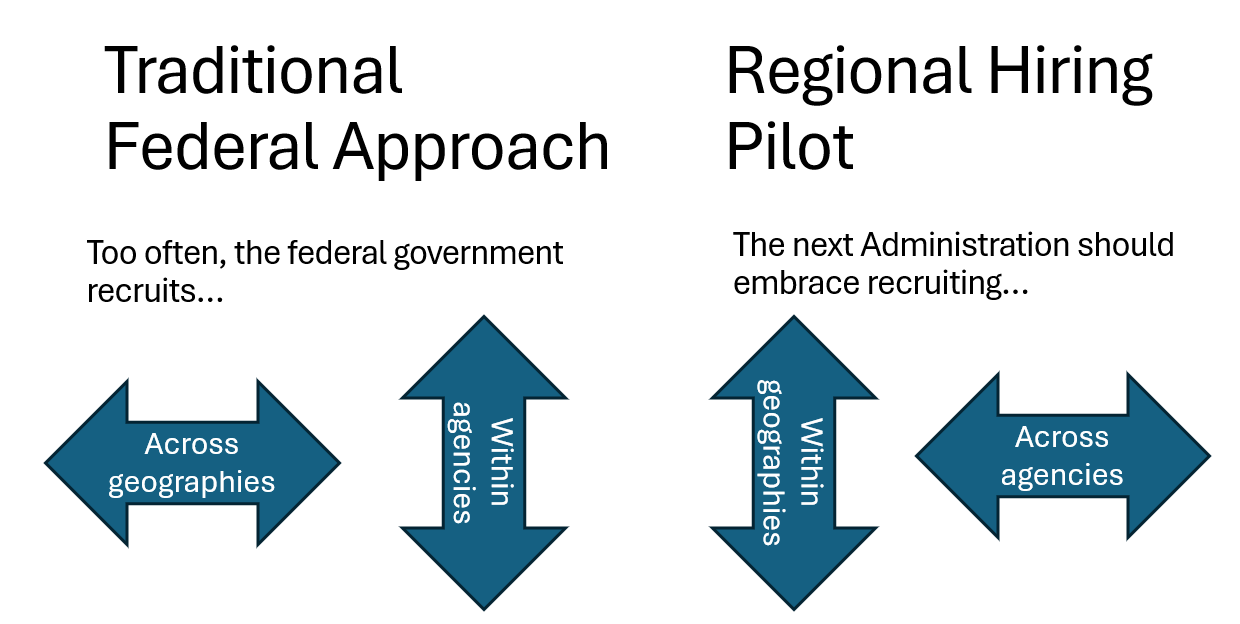

Build Efficient Permitting Teams and Standardize Roles

In our research, we interviewed one program manager who restructured their team to drive efficiency and support continuous improvement. However, this is not common. Rather, there is a lack of standardization in roles engaged in permitting teams within and across agencies, which hinders collaboration and prevents efficiencies. This is likely driven by the different roles played by agencies in permitting processes. These variances are in opposition to shared certifications and standardized job descriptions, complicate workforce planning, hinder staff training and development, and impact report consistency. The Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OMB, and the CHCO Council should improve the performance and consistency of permitting processes by establishing standards in permitting team roles and configurations to support cross-agency collaboration and drive continuous improvements.

- Characterize Types of Permitting Processes: Permitting Council staff should work with Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, and Permitting Program Team leaders to categorize types of permitting processes based on project “footprint”, complexity, regulatory reach (i.e., regulations activated), populations affected and other criteria. Identify the range of team configurations in use for the categories of processes.

- Map Agency Permitting Roles: Permitting Council staff should map and clarify the roles played by each agency in permitting processes (e.g., sponsoring agency, contributing agency) to provide a foundation for understanding the types of teams employed to execute permitting processes.

- Research and Analyze Agency Permitting Staffing: Permitting Council staff should collaborate with OMB to conduct or refine a data call on permitting staffing. Analyze the data to compare the roles and team structures that exist between and across agencies. Conduct focus groups with cross agency teams to identify consistent talent needs, team functions, and opportunities for standardization.

- Develop Permitting Team Case Studies: Permitting Council staff should conduct research to develop a series of case studies that highlight efficient and high performing permitting team structures and processes.

- Develop Permitting Team Models: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop team models for different agency roles (i.e., sponsor, lead agency, coordinating agency) that focus on driving efficiencies through process improvements and technology, and develop guidelines for forming new permitting teams.

- Create Permitting Job Personas: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop personas to showcase the roles needed on each type of permitting team and roles, recognizing that some variance will always remain, and the type of hiring authority that should be used to acquire those roles (e.g., IPA for highly specialized needs). This should also include new roles focused on process improvements; technology and data acquisition, use, and development; and product management for efficiency, improved customer experience, and effectiveness.

- Define Standardized Permitting Roles and Job Analyses: With the support of Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should identify roles that can be standardized across agencies based on the personas, and collaborate with permitting agencies to develop standard job descriptions and job analyses.

- Develop Permitting Practice Guide: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop a primer on federal permitting practices that explains how to efficiently and effectively complete permitting activities.

- Place Organizational Strategy Fellows: Permitting Council staff should hire at least one fellow to their staff to lead this effort and coordinate/liaise between permitting teams at different agencies.

- Mandate Permitting Hiring Forecasts: Permitting Council staff should collaborate with the CHCO Council to mandate permitting hiring forecasts annually with quarterly updates.

- Revise Permitting Funding Requirements: Permitting Council staff should include requirements for the adoption of new team models and roles in the resources and coordination provided to permitting agencies to drive process efficiencies.

Improve Workforce Strategy, Planning, and Decisions through Quality Workforce Metrics

Agency permitting leaders and those working across agencies do not have the information to make informed workforce decisions on hiring, deployment, or workload sharing. Attempts to access accurate permitting workforce data highlighted inefficient methods for collecting, tracking, and reporting on workforce metrics across agencies. This results in a lack of transparency into the permitting workforce, data quality issues, and an opaque hiring progress. With these unknowns, it becomes difficult to prioritize agency needs and support. Permitting provided a purview into this challenge, but it is not unique to the permitting domain. OPM, OMB, the CHCO Council, and Permitting Council staff need to accurately gather and report on hiring metrics for talent surges and workforce metrics by domain.

- Establish Permitting Workforce Data Standards: OPM should create minimum data standards for hiring and expand existing data standards to include permitting roles in employee records, starting with the Request for Personnel Action that initiates hiring (SF52). Permitting Council staff should be consulted in defining standards for the permitting workforce.

- Mandate Agency Data Sharing: OPM and OMB should require agencies share personnel action data; this should be done automatically through APIs or a weekly data pull between existing HR systems. To enable this sharing, agencies must centralize and standardize their personnel action data from their components.

- Create Workforce Dashboards: OPM should create domain-specific workforce dashboards based on most recent agency data and make it accessible to the relevant agencies. This should be done for the permitting workforce.

- Mandate Permitting Hiring Forecasts: The CHCO Council should mandate permitting hiring forecasts annually with quarterly updates. This data should feed into existing agency talent management/acquisition systems to track workforce needs and support adaptive decision making.

Invest in Professional Development and Early Career Pathways

There are few early career pathways and development opportunities for personnel who engage in permitting activities. This limits agencies’ workforce capacity and extends learning curves for new staff. This results in limited applicant pools for hiring, understaffed permitting teams, and limited access to expertise. More recently, many of the roles permitting teams hired for were higher level GS positions. With a greater focus on early career pathways and development, future openings could be filled with more internal personnel. In our research, one hiring manager shared how they established an apprenticeship program for early career staff, which has led 12 interns to continue into permanent federal service positions. The Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, and CERPOs should create more development opportunities and early career pathways for civil servants.

- Invest in Training to Upskill and Reskill Staff: The Permitting Council staff should continue investing in training and development programs (i.e., Permitting University) to upskill and reskill federal employees in critical permitting skills and knowledge. Leveraging the knowledge gained through creating standard permitting team roles and collaborating with permitting leaders, the Permitting Council staff should define critical knowledge and skills needed for permitting and offer additional training to support existing staff in building their expertise and new employees in shortening their learning curve.

- Allocate Permitting Staff Across Offices and Regions: CERPOs and Deputy Secretaries should implement a flexible staffing model to reallocate staff to projects in different offices and regions to build their experience and skill set in key areas, where permitting work is anticipated to grow. This can also help alleviate capacity constraints on projects or in specific locations.

- Invest in Flexible Hiring Opportunities: CERPOs and Deputy Secretaries should invest in a range of flexible hiring options, including 10-year STEM term appointments and other temporary positions, to provide staffing flexibility depending on budget and program needs. Additionally, OPM needs to redefine STEM to include technology positions that do not require a degree (e.g., Environmental Protection Specialists).

- Establish a Permitting Apprenticeship: The Permitting Council staff should establish a 1-year apprenticeship program for early career professionals to gain on-the-job experience and learn about permitting activities. The apprenticeship should focus on common roles shared across agencies and place talent into agency positions. A rotational component could benefit participants in experiencing different types of work.

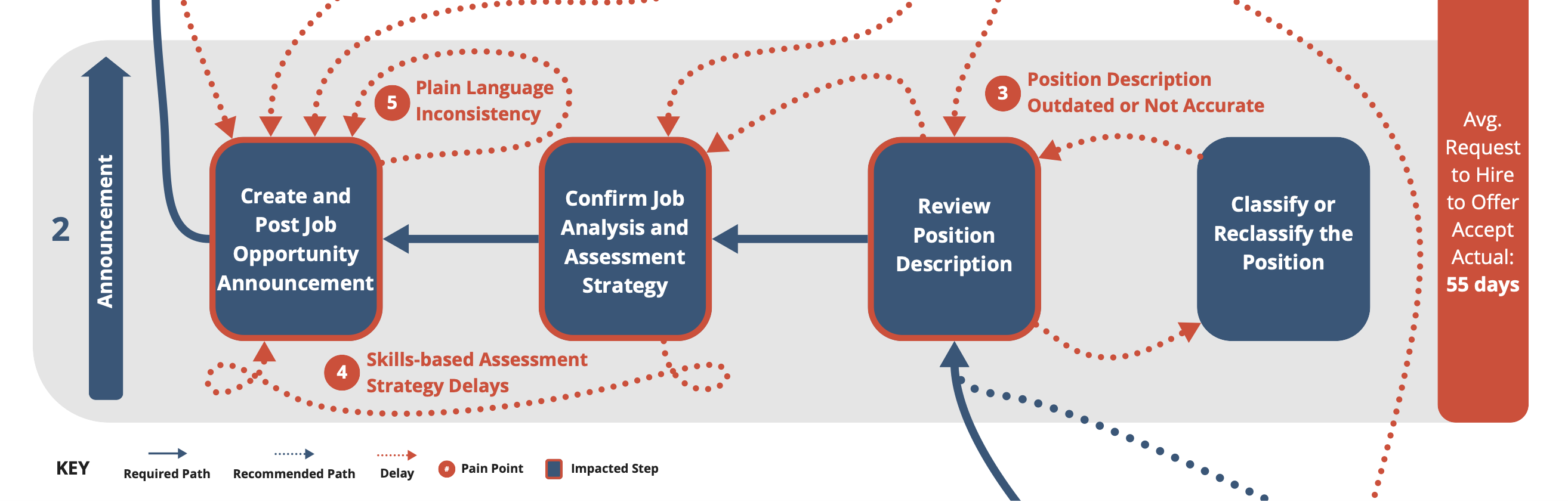

Improve and Invest in Pooled Hiring for Common Positions

Outdated and inaccurate job descriptions slow down and delay the hiring process. Further delays are often caused by the use of non-skills-based assessments, often self-assessments, which reduce the quality of the certificate list, or the list of eligible candidates given to the hiring manager. HR leaders confront barriers in the authority they have to share job announcements, position descriptions (PDs), classification determinations, and certificate lists of eligible candidates (Certs). Coupled with the above ideas on creating consistency in permitting teams and roles and better workforce data, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, and CERPOs should improve and make joint announcements, shared position descriptions, assessments, and certificates of eligibles for common positions a standard practice.

- Provide CHCOs the Delegated Authority to Share Announcements, PDs, Assessments, and Certs: OPM and OMB should lower the barriers for agencies to share key hiring elements and jointly act on common permitting positions by delegating the authority for CHCOs to work together within and across their agencies, including with the Permitting Council staff.

- Revise Shared Certificate Policies: OPM and OMB should revise shared certificate policies to allow agencies to share certificates regardless of locations designated in the original announcement and the type of hire (temporary or permanent). They should require skills-based assessments in all pooled hiring. Additionally, OPM should streamline and clarify the process for sharing certificates across agencies. Agencies need to understand and agree to the process for selecting candidates off the certificate list.

- Create a Government-wide Platform for Permitting Hiring Collaboration: OPM should create a platform to gather and disseminate permitting job announcements, PDs, classification determinations, job/competency evaluations, and cert. lists to support the development of consistent permitting teams and roles.

- Pilot Sharing of Announcements, PDs, Assessments, and Certs for Common Permitting Positions: OPM and the CHCO Council should collaborate with the Permitting Council staff to select most common and consistent permitting team roles (e.g., Environmental Protection Specialist) to pilot sharing within and across agencies.

- Track Permitting Hiring and Workforce Performance through Data Sharing and Dashboards: Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, and CERPOs should leverage the metrics (see Improve Workforce Decisions Through Quality Workforce Metrics) and data actions above to track progress and make adjustments for sharing permitting hiring actions.

- Incorporate Shared Certificates into Performance: OPM and the CHCO Council should incorporate the use of shared certificates into the performance evaluations of HR teams within agencies.

Improve Human Resources Support for Hiring Managers

Hiring managers lack sufficient support in navigating the hiring and recruiting process due to capacity constraints. This causes delays in the hiring process, restricts the agency’s recruiting capabilities, limits the size of the applicant pools, produces low quality candidate assessments, and leads to offer declinations. The CHCO Council, OPM, CERPOs, and the Permitting Council staff need to test new HR resourcing models to implement hiring best practices and offer additional support to hiring managers.

- Develop HR Best Practice Case Studies: OPM should conduct research to develop a series of case studies that highlight HR best practices for recruitment, performance management, hiring, and training to share with CHCOs and provide guidance for implementation.

- Document Surge Hiring Capabilities: In collaboration, the Permitting Council staff and CERPOs should document successful surge hiring structures (e.g., strike teams), including how they are formed, how they operate, what funding is required, and where they sit within an organization, and plan to replicate them for future surge hiring.

- Create Hiring Manager Community of Practice: In collaboration, the Permitting Council staff and Permitting Agency HR Teams with support from the CHCO Council should convene a permitting hiring manager community of practice to share best practices, lessons learned, and opportunities for collaboration across agencies. Participants should include those who engage in hiring, specifically permitting hiring managers, HR specialists, and HR leaders.

- Develop Permitting Talent Training for HR: OPM should collaborate with CERPOs to create a centralized training for HR professionals to learn how to hire permitting staff. This training could be embedded in the Federal HR Institute.

- Contract HR Support for Permitting: The Permitting Council staff should create an omnibus contract for HR support across permitting agencies and coordinate with OPM to ensure the resources are allocated based on capacity needs.

- Establish HR Strike Teams: OPM should create a strike team of HR personnel that can be detailed to agencies to support surge hiring and provide supplemental support to hiring managers.

- Place a Permitting Council HR Fellow: The Permitting Council should place an HR professional fellow on their staff to assist permitting agencies in shared certifications and build out talent pipelines for the key roles needed in permitting teams.

- Establish Talent Centers of Excellence: The CHCO Council should mandate the formation of a Talent Center of Excellence in each agency, which is responsible for providing training, support, and tools to hiring managers across the agency. This could include training on hiring, hiring authorities, and hiring incentives; recruitment network development; career fair support; and the development of a system to track potential candidates.

Next Steps

These recommendations aim to address talent challenges within the federal permitting ecosystem. As you can see, these issues cannot be addressed by one stakeholder, or even one agency, rather it requires effort from stakeholders across government. Collaboration between these stakeholder groups will be key to realizing sustainable permitting workforce capacity.

Setting the Stage for a Positive Employee Experience

Federal hiring ebbs and flows with changes in administrations, legislative mandates, attrition, hiring freezes, and talent surges. The lessons and practices in this blog post series explore the earlier stages of the hiring process. Though anchored in our permitting talent research, the lessons are universal in their application, regardless of the hiring environment. They can be used to accelerate and improve hiring for a single or multiple open positions, and they can be kept in reserve during hiring downturns.

Assessing, Selecting, and Onboarding the Successful Candidate

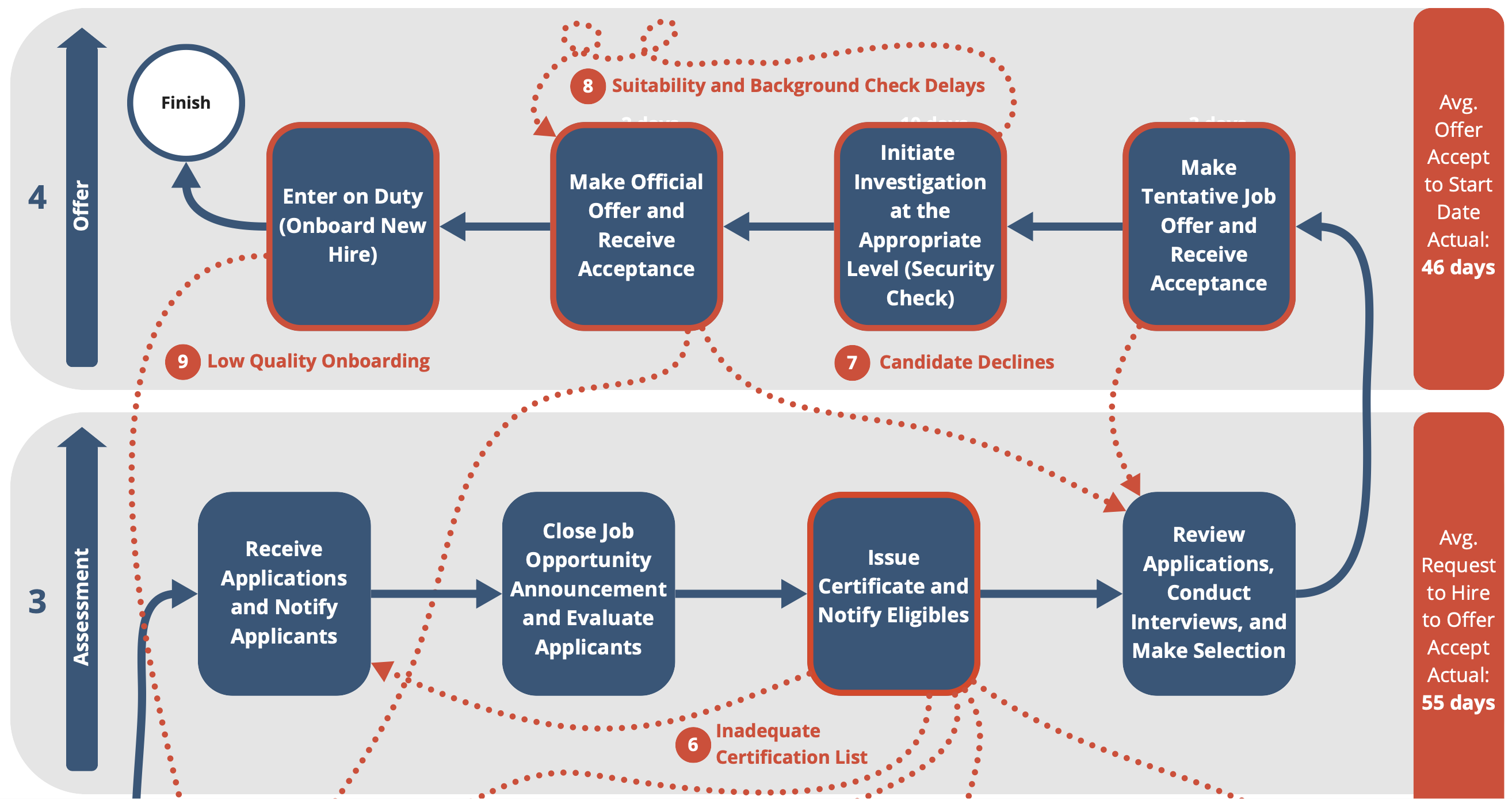

Previously we described the end-to-end hiring process, the importance of getting hiring right from the start, and how sharing resources speeds hiring. This post focuses on the last two phases of the process: Assessment and Offer. While these phases include eight steps, we’ve narrowed down our discussion to five key steps:

- Close Job Opportunity Announcement and Evaluate Applicants

- Review Certificate of Eligibles, Conduct Interviews, and Make Selection

- Make Tentative Job Offer and Receive Acceptance

- Initiate Investigation at the Appropriate Level (Security Check)

- Make Official Offer and Enter on Duty (Onboard New Hire)

Our insights shared in this post are based on extensive interviews with hiring managers, program leaders, staffing specialists, workforce planners, and budget professionals as well as on-the-job experience. These recommendations for improvement focus on process and do not require policy or regulatory changes. They do require adoption of these practices more broadly throughout HR, program, and permitting managers, and staff. These recommendations are not unique to permitting; they apply broadly to federal government hiring. These insights should be considered both for streamlining efforts related to environmental permitting, as well as improving federal hiring.

Breaking Down the Steps

For each step, we provide a description, explain what can go wrong, share what can go right, and provide some examples from our research, where applicable.

Close Job Opportunity Announcement and Evaluate Applicants

Once the announcement period has ended, job announcements close, and HR begins reviewing the applications in the competitive hiring process. HR reviews the applications, materials provided by the applicants, and the completed assessments, which vary depending on the assessment strategy. This selection process is governed by policies in competitive examination and will be determined by whether the agency is following category rating, rule of many, or other acceptable evaluation methods.

If the agency is using a different hiring authority or flexibility, this step will change. For example, if the agency has Direct Hire Authority (DHA), they may not need to provide a rigorous assessment and may be able to proceed to selection after a review of resumes. Most agencies will still engage in some assessment process for these types of positions. After the applicants are evaluated, HR issues a Certificate of Eligibles (or “cert list”) with the ranking of the applicants from which the hiring manager can select, including the implementation of Veterans preference.

What Can Go Wrong

- Most applicant assessments rely on the resume review and candidate self-assessment. Applicants who understand the process rate themselves as highly qualified on all aspects of the job, resulting in a certificate list with unqualified applicants at the top. Agencies are now required by law to use skills-based assessments in the Chance to Compete Act and previous Executive Order guidance to prevent this, but the adoption process will be slow.

- HR staffing resources are frequently strained to immediately review applications and resumes causing delays. This causes applicant and hiring manager dissatisfaction and possibly a loss of attractive, qualified applicants. Within permitting, hiring managers have been struggling to find talent with the required expertise, especially specialized or niche expertise, and this loss is a critical setback.

- Frequently HR specialists do not consult with the program managers to gain a deep understanding of what they’re looking for in a resume or application and rely solely on their interpretation of the qualifications listed in the position description. This can result in poor quality applicants referred to the hiring manager.

What Can Go Right

- If the recruiters and hiring manager have engaged in effective recruiting, applicant quality is likely to be quite high. This eases the HR’s job of finding strong applicants.

- With a strong applicant pool, HR specialist can limit the number of applicants they consider and/or limit how long the job announcement is open. This will expedite the process, as the assessment will be faster. Rigorous assessments reduce the likelihood of unqualified applicants making it to the certificate list. A hiring manager who insists on a skills-based assessment will likely move forward with a successful hire. Using subject-matter experts in a Subject Matter Expert Qualifications Assessment (SME-QA) or similar assessment process can result in a strong list of applicants, and it has the added benefit of building familiarity by engaging the employee’s future peers in the process.

Review Certificate of Eligibles, Conduct Interviews, and Make Selection

HR sends a Certificate of Eligibles (certificate list) to the hiring manager that ranks the applicants who passed the assessment(s). Under competitive hiring rules (as opposed to some of the other hiring authorities), hiring managers are obligated to select from the top of the Certificate of Eligibles list, or those considered to be most qualified.

The Veterans preference rules also require that qualified Veterans move to the top of the list and must be considered first. Outside of competitive hiring and under other hiring authorities, the hiring manager may have more flexibility in the selection of candidates. For example, direct hire authority allows the hiring manager to make a selection decision based on their own review of resumes and applications.

If determined as part of the assessment process beforehand, the hiring manager may choose to conduct final interviews with the top candidates. In this case, the manager then informs HR of their selection decision.

What Can Go Wrong

- If the hiring manager cannot find an applicant they deem qualified on the certificate list, they inform HR, restart the hiring action, and/or re-post the position, further delaying the process. This happens frequently when the assessment tools default to a self-evaluation, or self-assessment. One Hiring Manager we met needed to request a second certificate list, and this extended the hiring process to nine months.

- Lack of resources in HR or the hiring manager’s program often results in evaluation and selection delays. Top applicants in high demand may take other jobs if the process takes longer than anticipated. This was a concern voiced by hiring managers during our interviews.

- In rare circumstances, agency funding could be uncertain and the budget function could rescind the approval to hire at this stage, frustrating hiring managers, applicants, and HR specialists.

What Can Go Right

- Strong recruiting early and throughout the process results in a strong certificate list with excellent candidates. One permitting agency, following best practice, kept a pipeline of potential candidates, including prior applicants to boost the quality of the applicant pool.

- An effective assessment process weeds out unqualified or unsuitable candidates and culls the list of applicants to only those who can do the job.

- A deep partnership between the HR staffing specialist and the hiring manager in which they discuss the skills and “fit” of the top candidates increases the hiring manager’s confidence in the selection.

Make Tentative Job Offer and Receive Acceptance

HR reaches out to the applicant to make a tentative job offer (i.e., tentative based on the applicant’s suitability determination, outlined below) and asks for a decision from the applicant within an acceptable time frame, which is normally a couple of days to a week. The HR staffing specialist will keep in close contact with the hiring manager and HR officials regarding the status of the candidate accepting the position.

What Can Go Wrong