The Two-Hundred Billion Dollar Boondoggle

Nearly one year after the Pentagon certified the Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile program to continue after it incurred critical cost and schedule overruns, the new nuclear missile could once again be in trouble.1

An April 16th article from Defense Daily broke the news that the Air Force will have to dig new holes for the Sentinel silos.2 The service had been planning to refurbish the existing 450 Minuteman silos but recently discovered, as noted in a follow-up article from Breaking Defense, that the silos will “largely not be reusable after all.”3 Brig. Gen. William Rogers, the Air Force’s director of the ICBM Systems Directorate, cited asbestos, lead paint, and other issues with the existing silos that make refurbishment difficult.4 Air Force officials also stated that an ongoing study into missileer cancer rates played a role in the decision to build new silos.5

This news comes shortly after reports that the Air Force is planning to extend the life of the currently deployed Minuteman III ICBMs until “at least” 2050—roughly 20 years beyond their intended service lives—due to delays in the Sentinel program.6

For those who have been tracking the Sentinel development since the Air Force first conceptualized a new ICBM in the early 2010s, the reports of Minuteman life-extension likely made them pause and recall the common refrain from Sentinel proponents over the years that life-extending Minuteman III missiles would be too expensive or even impossible. “You cannot life-extend Minuteman III,” then-commander of US Strategic Command Adm. Charles Richard told reporters in 2021.7 In 2016, the Air Force told Congress that the Minuteman III was aging out, therefore the “GBSD solution” was necessary to ensure the future viability of the ICBM force (GBSD is short for Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent, the programmatic name for the ICBM before Sentinel was chosen in 2022). Air Force officials still maintain that a life-extension program for Minuteman is not possible. In their words, Minuteman will be “sustain[ed] to keep it viable until Sentinel is delivered.”8 Regardless of how the Air Force refers to the effort, it appears that Minuteman III will be made to operate well beyond its planned service life.

For some, like our team at the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project, Sentinel’s newest struggles came as no surprise at all. For years, it has been clear to observers that this program has suffered from chronic unaccountability, overconfidence, poor performance, and mismanagement. Project benchmarks were cherry-picked, viable alternatives were prematurely dismissed, competition was discouraged, and goalposts were continuously moved. Ultimately, it will be U.S. taxpayers who pay the increasingly rising costs, and other—more critical—priorities will suffer as Sentinel continuously sucks money away from other programs.

It comes as no surprise that Sentinel was specifically named in the White House’s recent memo requiring all Major Defense Acquisition Programs more than 15% over-budget or behind schedule to be “reviewed for cancellation;” Sentinel is the poster-child for inefficiency, which the administration claims to be obsessed with eliminating.9 In order to prevent this type of mismanagement for future programs, we must first understand how Sentinel went so wrong.

How We Got Here

The Federation of American Scientists has been intensively tracking the progress of the Sentinel program for years. Throughout the acquisition process, the Air Force clung to its fundamental and counterintuitive assumption that building an entirely new ICBM from scratch would be cheaper than life-extending the current system. We now know that this assumption was wildly incorrect, but how did it reach this point?

Cherry-picked project benchmarks

When seeking to plug a capability gap, the Pentagon is required to consider a range of procurement options before proceeding with its acquisition. This process takes place over several years and culminates in an “Analysis of Alternatives”—a comparative evaluation of the operational effectiveness, suitability, risk, and life-cycle costs of the various options under consideration. This assessment can have tremendous implications for an acquisition program, as it documents the rationale for recommending a particular course of action.

The Air Force’s Analysis of Alternatives for the program that would eventually become Sentinel was conducted between 2013 and 2014, and concluded that the costs of pursuing a Minuteman III life-extension would be nearly the same as those projected for Sentinel.10 Crucially, this cost comparison was pegged to a predetermined requirement to continue deploying the same number of missiles until the year 2075.11

These benchmarks, despite having no apparent inalterable national security imperative, appear to have played a significant role in shaping perceptions of the two options. While it is now clear that Minuteman III could be—and likely will be—life-extended for several more decades, the Air Force does not have enough airframes to keep at least 400 of them in service through 2075 and maintain the testing campaign needed to ensure reliability. As a result, in order to push the ICBM force beyond 2075, the Air Force would need to life-extend Minuteman III and pursue a follow-on system after that point.

This was reportedly reflected in the Air Force’s cost analysis, which explains why the cost of the Minuteman III life-extension option was estimated by the Air Force to be roughly the same as the cost of building an entirely new ICBM.12 The service was not simply comparing the costs of a life-extension and a brand-new system; it was instead comparing the costs of pursuing Sentinel immediately on the one hand, versus a Minuteman III life-extension and development of a follow-on system on the other hand.

Of course, policymakers require benchmarks in order to make estimates: it would not be reasonable to analyze the feasibility of a particular system without considering how long and at what level that system needs to perform. However, in the case of the Sentinel, selecting those particular benchmarks at the beginning of the process essentially pre-baked the analysis before it even began in earnest.

Let’s say a different evaluation benchmark had been selected—2050, for example, rather than 2075.

In January 2025, Defense Daily reported that the Air Force would likely have to keep portions of the Minuteman III fleet in service until 2050 or later.13 This may require altering certain aspects of the Minuteman III’s deployment—such as reducing the number of deployed ICBMs or annual test launches in order to preserve airframes. While no final decisions have been made, the Air Force is clearly evaluating continued reliance on Minuteman III as a potential option, despite years of high-ranking military and political officials stating that doing so was impossible.14

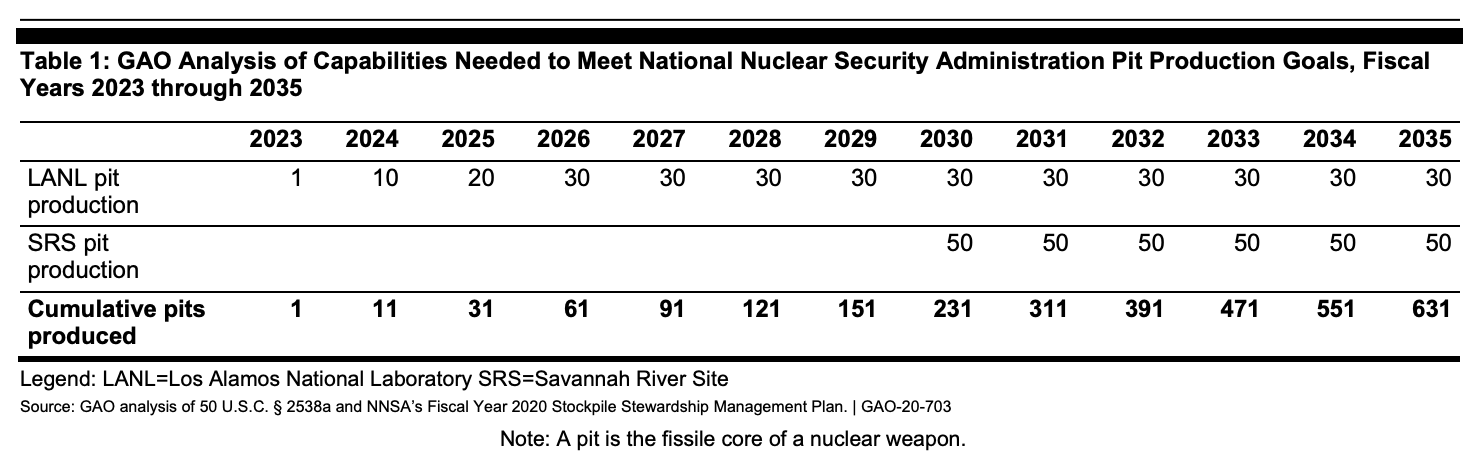

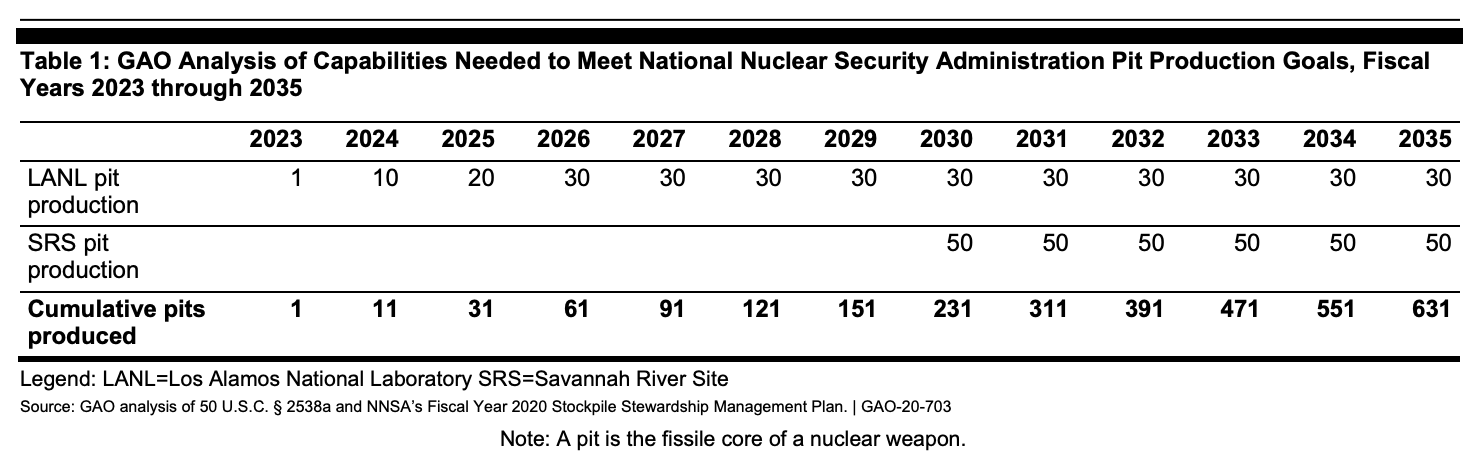

Benchmarking the cost analysis at 2050 rather than 2075 would have thus yielded wildly different results. In 2012, the Air Force admitted that it cost only $7 billion to modernize its Minuteman III ICBMs into “basically new missiles except for the shell.”15 While getting those same missiles past 2050 would certainly add additional cost and complexity—particularly to replace parts whose manufacturers no longer exist—it is unfathomable that the costs would come anywhere close to those of the Sentinel program, which was estimated by the Pentagon’s Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) in 2020 (before the critical cost overrun) to have a total lifecycle cost of $264 billion in then-year dollars.

It is particularly troubling that very few public or independent government-sponsored analyses were conducted to look into the Sentinel program’s flawed assumptions, nor the realistic possibility of a Minuteman III life-extension. Countless congressional and non-governmental attempts to push for one were stymied at every turn. In 2019, for example, dozens of lobbyists from the Sentinel contract bidders successfully helped to eliminate a proposed amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act calling for an independent study on a Minuteman III life-extension program.16

The most comprehensive public study on this issue was a 2022 report published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace under contract from the Pentagon; however, the study noted that “the iterative process through which we received information, the unclassified nature of our study, and the limited time available for investigating DOD conclusions left us unable to assess the DOD’s position regarding the technical and cost feasibility of an extended Minuteman III alternative to GBSD;” the authors ultimately concluded that a more detailed technical analysis was required in order to answer these questions.17

While the findings of such a study will never be known, it is likely that they would have supported what was clear to government watchdogs at the time and has been validated in spades since then: the assumptions baked into this program were flawed from the start, and the system’s costs would be significantly larger than initially expected. Given that the Pentagon ultimately went in the opposite direction, taxpayers are now on the hook for both a de facto Minuteman III life-extension program as well as the substantial costs associated with acquiring Sentinel—with limited further possibilities for near-term cost mitigation.

Failure to predict the true costs and needs of the program

In addition to the cherry-picked benchmarks that tipped the scales towards a brand-new ICBM, when comparing costs the Air Force made a key error in its assumptions: it assumed that the Sentinel would be able to reuse much of the original Minuteman launch infrastructure.

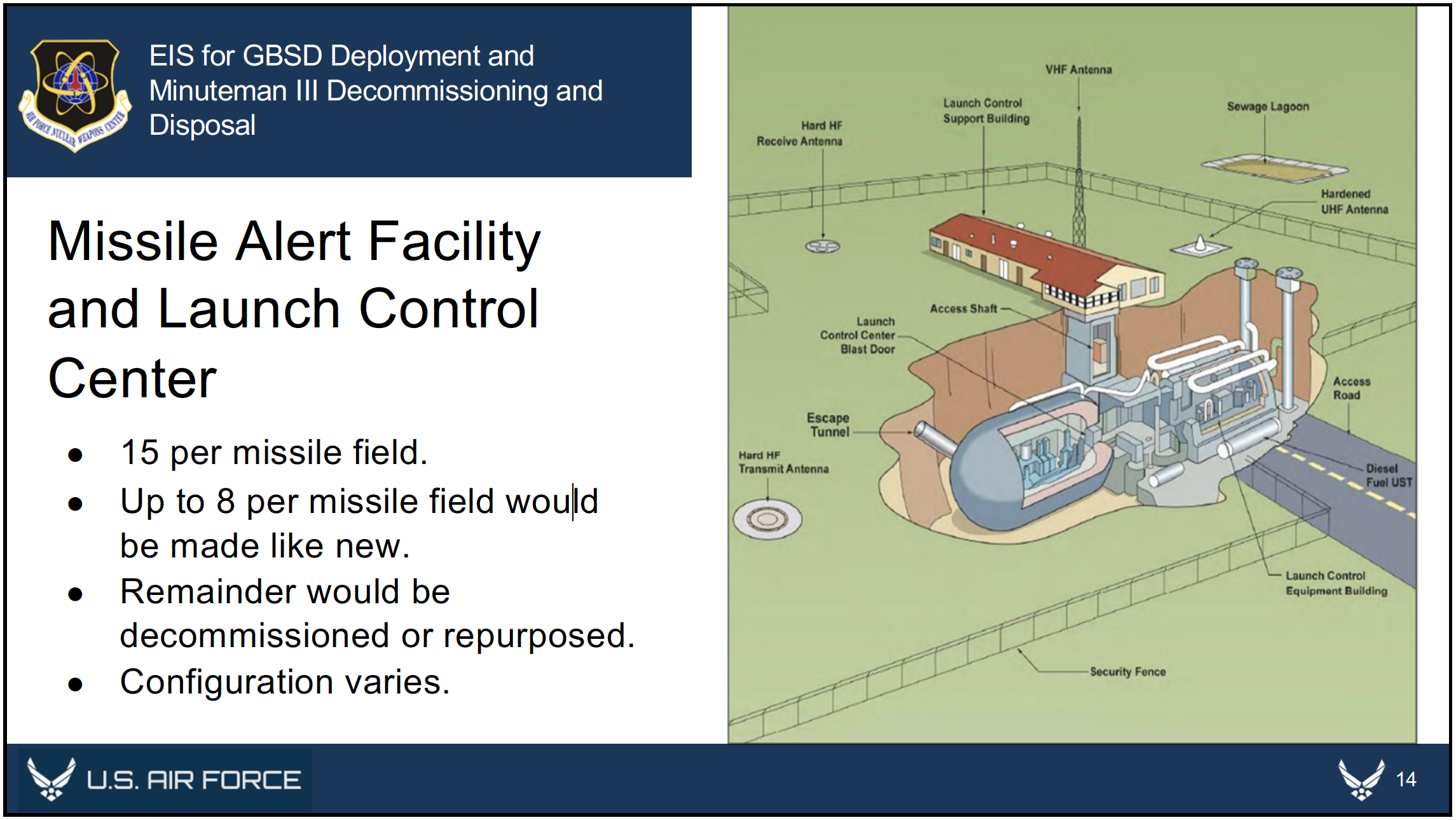

Some level of infrastructure modernization for the Sentinel was always planned, including building entirely new launch control centers and additional infrastructure for the launch facilities.18 However, the original plans called for reusing existing copper command and control cabling and the refurbishment—not reconstruction—of 450 silos. Both assumptions have proven incorrect, and perhaps more than anything else, now represent the single greatest driver of Sentinel’s skyrocketing costs.

While both the current cabling and launch facilities work fine for the existing Minuteman III and would presumably function similarly following a life-extension, they are apparently incompatible with Sentinel’s increasingly complex design.

The Air Force must now dig up and replace 7,500 miles of cabling with the latest fiber optic cables. Much of these cables are buried underneath private property, meaning that local landowners must lease 100-foot-wide lines on their property to the Pentagon to be dug up for multi-year periods.19

In addition, both the Air Force and Northrop Grumman have now recognized that it will take more than simple refurbishments to make the existing Minuteman III launch facilities compatible with Sentinel. Both the service and the contractor have stated that several of the assumptions regarding the conversion process that went into the 2020 baseline review have now proved to be incorrect.20

As a result, the Air Force is apparently now planning to build entirely new launch facilities to house the Sentinel, most of which will require digging new holes in the ground.21 As one Northrop Grumman official explained, “When you multiply that by 450, if every silo is a little bit bigger or has an extra component, that actually drives a lot of cost because of the sheer number of them that are being updated.”22 It is unclear whether the costs will increase beyond the new estimate released with the Nunn-McCurdy decision, but the program is clearly trending in the wrong direction.

The Air Force had been publicly teasing the prospect of digging new holes for nearly a year. At the Triad Symposium in Washington, D.C., in September 2024, Maj. Gen. Colin Connor, director of ICBM Modernization at Barksdale Air Force Base, responded to an audience question about the new silos rumor by saying, “we’re looking at all of our options.” Despite the noncommittal answer, the decision to dig new silos seems to have already been made by the time of Connor’s statement.

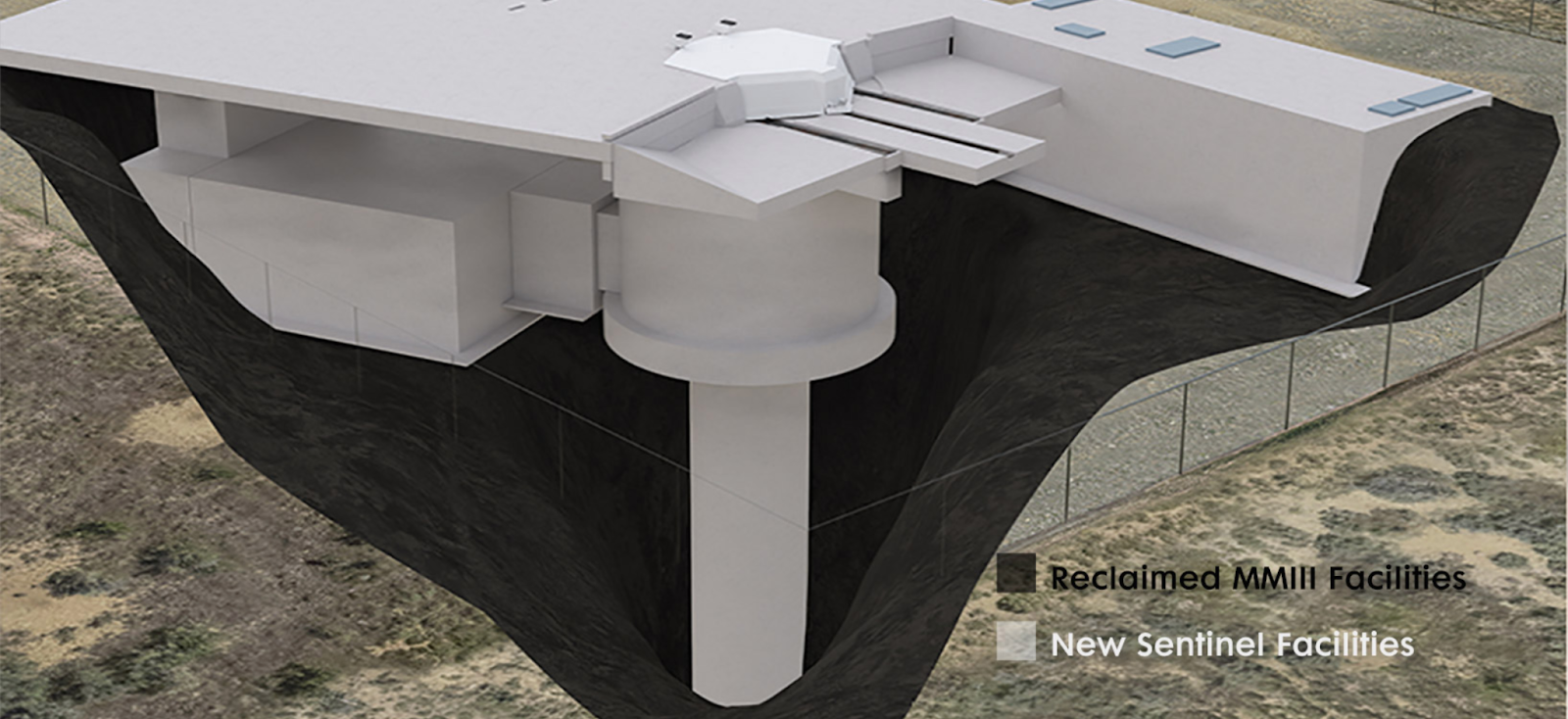

Firstly, it has since been revealed that the estimated costs of the new silos were included in the Nunn-McCurdy review process which concluded in July 2024. Additionally, although the decision was not made public until the April 16 Defense News article, Northrop Grumman may have inadvertently revealed the news much earlier. Included in the gallery of images of the Sentinel program on Northrop’s website is a digital mockup of a Sentinel launch facility. The first version of the image (see Figure A below) illustrates the Air Force’s original plan to refurbish the Minuteman III silos for Sentinel, with a key indicating the silo and silo lid as “Reclaimed MMIII Facilities.” A newer version of the image (see Figure B below) was uploaded to the gallery as early as February 2024 and shows the entire launch facility—including the silo and silo lid—as “New Sentinel Facilities.”

Original rendering of Sentinel launch facility. (Source: Northrop Grumman)

New rendering of Sentinel launch facility. (Source: Northrop Grumman)

Unwarranted overconfidence

Despite the clear concerns outlined above, the Pentagon was remarkably confident in its and Northrop Grumman’s abilities to deliver the Sentinel on-time and on-budget.

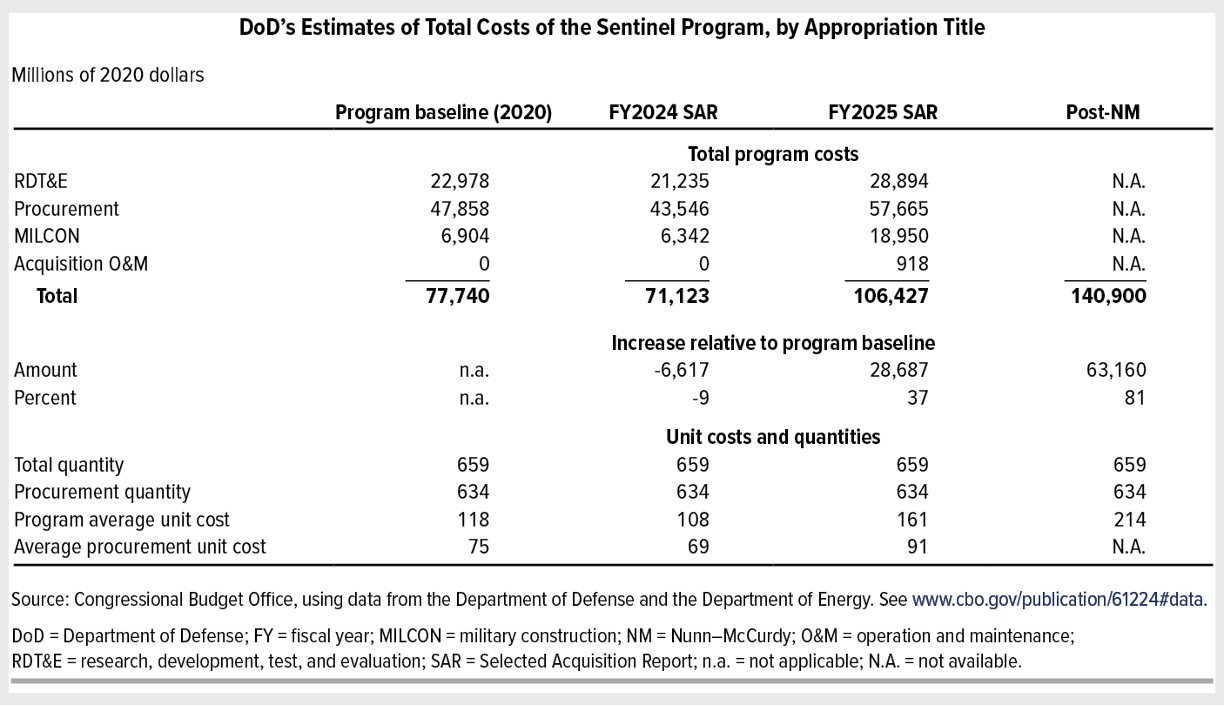

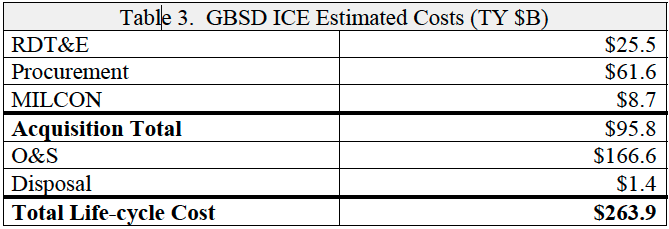

In September 2020, the Pentagon delivered its Milestone B summary report to Congress—a key decision point at which acquisition programs are authorized to enter the Engineering and Manufacturing Development phase, considered to be the official start of a program. The Milestone B report included an estimate of $95.8 billion in then-year dollars to acquire the Sentinel—a significant increase from previous estimates, but not yet the dire situation that we find ourselves in today (Figure C).

The above table from the Congressional Budget Office shows the cost growth for the Sentinel’s acquisition program between the Sentinel’s Milestone B assessment in 2020 and the post-Nunn-McCurdy review process in 2025. All costs are reflected in FY2020 dollars to allow for an accurate comparison between years.

We now know, however, based on recent statements from Pentagon and Air Force officials, that there were “some gaps in maturity” in the Milestone B report.23 Specifically, “in September of 2020, the knowledge of the ground-based segment of this program was insufficient in hindsight to have a high-quality cost estimate.” What this means is that at the most consequential stage of the program to-date, it was approved without a comprehensive understanding of the likely cost growth.

Furthermore, the Air Force was heavily delayed in creating an integrated master schedule for the Sentinel program. An integrated master schedule includes the planned work, the resources necessary to accomplish that work, and the associated budget; from the government’s perspective, it is considered to be the keystone for program management.24 Although the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment testified to Congress that “By the time you’re six months after Milestone B, you should have an integrated master schedule,” the Air Force had not met this mark.25 If the Air Force did manage to create such a schedule, it became obsolete with the Nunn-McCurdy Act’s requirement to restructure the program and rescind its Milestone B approval.

During that same hearing, the Air Force’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration also admitted that at that time, the service had been experiencing poor communication with Northrop Grumman, the primary contractor for the ICBM.

Performance issues also appear to have had an impact on the program. In June 2024, the Air Force removed the colonel in charge of its Sentinel program—reportedly for a “failure to follow operational procedures”—and replaced him with a two-star general, with the rank change indicating a need for greater high-level attention.26

Throughout this time, the Air Force remained overconfident in its abilities to deliver the program; in December 2020, the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics told reporters that the Air Force had “godlike insight into all things GBSD.”27 And in September 2022, the Air Force Major General responsible for Sentinel’s strategic planning and requirements said in a Breaking Defense interview that the program was “on cost, on schedule, and the acquisition program baseline is being met.”28

Given everything we now know about the state of the Sentinel program, these statements were either clear obfuscations or just pure fantasy.

Non-competitive disadvantages

When addressing concerns about the rising projected costs of the Sentinel program, Air Force leaders were confident that a competitive and healthy industrial base would be able to keep the overall price tag down. As Gen. Timothy Ray, then-Commander of Air Force Global Strike Command, told reporters in 2019, “our estimates are in the billions of savings over the lifespan of the weapon.”29

These expected savings clearly never materialized, however, nor did the Pentagon help facilitate the conditions for them to be realized. In March 2018, the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center submitted a document justifying its intention to restrict competition for the Sentinel contract to just two suppliers—Boeing and Northrop Grumman—stating that this limitation would still constrain costs because the two companies would be in competition with one another.30

However, this specter of competition evaporated when Boeing withdrew from the competition following Northrop Grumman’s acquisition of Orbital ATK—one of two independent producers of large solid rocket motors left in the US market.31 As these motors are necessary to make ICBMs fly, the merger put Northrop Grumman in the driver’s seat: it could restrict access to those motors from Boeing, thus tanking its competitor’s chances at the Sentinel bid.

Doing so would not have been allowed by the terms of the Federal Trade Commission, which permitted the merger in 2018 but subsequently investigated it in 2022 under the Biden administration, and also subsequently blocked a similar attempted merger between Lockheed Martin and Aerojet Rocketdyne that same year.32 However, the Pentagon, which had initially included non-exclusionary and pro-competition language in its requirements for an earlier phase of the Sentinel contract, removed that language from future phases.33 By refusing to wield its own power to preserve competition—initially a key driver for promoting Sentinel over a Minuteman III life-extension—the Air Force essentially left the state of the competition in Northrop Grumman’s hands. According to Boeing’s CEO, Northrop Grumman subsequently slow-walked the process of hammering out a competition arrangement with Boeing—apparently not leaving enough time for Boeing to negotiate a competitive price for solid rocket motors before the Sentinel deadline.34

As a result, Boeing pulled out of the competition altogether, and the Air Force awarded the Sentinel engineering and manufacturing development contract to Northrop Grumman through an unprecedented single-source bidding process. As the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment admitted during 2024 testimony to Congress, what this amounted to was that “effectively there was not, at the end of the day, competition in this program.”35

Reflecting on the Sentinel procurement process, House Armed Services Committee chairman Adam Smith—who has a sizable Boeing presence in his home state of Washington—suggested in October 2019 that the Air Force is “way too close to the contractors they are working with,” and implied that the service was biased towards Northrop Grumman.36

Predictably, the evaporation of competition has coincided with skyrocketing Sentinel acquisition costs. In July 2024, the Air Force’s acquisition chief Andrew Hunter reportedly told reporters that the Air Force was considering reopening parts of the Sentinel contract to bids. “I think there are elements of the ground infrastructure where there may be opportunities for competition that we can add to the acquisition strategy for Sentinel,” Hunter said.37

The Nunn-McCurdy Saga

In January 2024, the Air Force notified Congress that the Sentinel program had incurred a critical breach of the Nunn-McCurdy Act, legislation designed to keep expensive programs in check.38 One week after notifying Congress of the breach, the Air Force fired the head of the Sentinel program, but said the move was “not directly related” to the Nunn-McCurdy breach.39

At the time of the notification, the Air Force stated that the program was 37% over budget and two years behind schedule. Six months later, after conducting the cost reassessment mandated by Nunn-McCurdy, the Pentagon announced that the Sentinel program would cost 81% more than projected and be delayed by several years.40 Nevertheless, the Secretary of Defense certified the program to continue.

Per the requirements of the Nunn-McCurdy Act, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, who serves as the Milestone Decision Authority for the program, rescinded Sentinel’s Milestone B approval, which is needed for a program to enter the engineering and manufacturing development phase.41 The Air Force must restructure the program to address the root cause of the cost growth before receiving a new milestone approval, a process the service has said will take approximately 18 to 24 months.42

Where Sentinel Stands Now

Work on the Sentinel program has continued while the Air Force carries out the restructuring effort, but the government can’t seem to decide whether things are going well or not.

On February 10, the Air Force told Defense One that parts of the Sentinel program had been “suspended.”43 Due to “evolving” requirements related to Sentinel launch facilities, the Air Force instructed Northrop Grumman to halt “design, testing, and construction work related to the Command & Launch Segment.” There has been no indication of when the stop work order will be lifted. Nevertheless, during an April 10 Air Force town hall on Sentinel in Kimball, Nebraska, Wing Commander of F.E. Warren AFB Col. Johnny Galbert told attendees that Sentinel “is not on hold; it is moving forward.”44

Just under one month after the stop work order was made, the Air Force announced that the Sentinel program had achieved a “modernization milestone” with the successful static fire test of Sentinel’s stage-one solid rocket motor.45 The test marked the successful test firing of each stage of Sentinel’s rocket motor after the second and third stages were tested in 2024.

On March 27, the same day Bloomberg reported that the Air Force was considering a life-extension program for Minuteman III missiles, President Trump’s nominee for Secretary of the Air Force (confirmed by the Senate on May 13), Troy Meinke, committed in his testimony to pushing Sentinel over the finish line, calling the program “foundational to strategic deterrence and defense of the homeland.”46 During the same hearing, Trump’s nominee for undersecretary of Defense for acquisition and sustainment, Michael P. Duffey, also shared his support for the Sentinel program, saying “nuclear modernization is the backbone of our strategic deterrent,” and endorsing Sentinel as “critical.” Yet, two weeks later, on April 9, President Trump signed an executive order to address defense acquisition programs that mandates, “any program more than 15% behind schedule or 15% over cost will be scrutinized for cancellation.”47 This places Sentinel well beyond the threshold for potential cancellation, and the White House fact sheet detailing the order explicitly called out Sentinel’s cost and schedule overruns.

The next day, the Air Force announced that another “key milestone” for the Sentinel program had been met with the stand-up of Detachment 11 at Malmstrom AFB, which will oversee implementation of the Sentinel program at the base.48 But of course, less than thirty days later, Sentinel took a major blow with the Air Force’s admittance that hundreds of new silos would have to be dug up and constructed for the new ICBM.

The Government Accountability Office’s (GAO) latest Weapon Systems Annual Assessment from June 11 reports that Sentinel’s costs “could swell further” as the Air Force “continues to evaluate its options and develop a new schedule as part of restructuring efforts.” The assessment also notes that the Sentinel program alone accounted for over $36 billion of the $49.3 billion increase from 2024 to 2025 in GAO’s combined total estimate of major defense acquisition program costs, and noted that the first flight test now would not take place until March 2028.49 In a sweeping criticism of the program, the GAO report notes that the continued immaturity of the program’s critical technologies more than 4 years into its development phase “calls into question the level of work required to mature these technologies and the validity of the cost estimate used to certify the program.”50

450 Money Pits

We probably will never know how much money could have been saved if the Air Force had elected from the beginning to life-extend the existing ICBMs rather than build an entirely new system from scratch. The opportunity to have a proactive, independent cost comparison and corresponding public debate was eliminated through intense rounds of Pentagon and industry lobbying. But we certainly now know that the Air Force’s assertion—that the Sentinel would be cheaper and easier than a life-extension—was wrong, and that the suppression of an independent review contributed to these rising costs.

The Sentinel saga, with its seemingly unending series of setbacks and continued uncertainties, begs a crucial question: what incentives exist for the Air Force to get it right? That the program, along with numerous other nuclear modernization programs, was green-lighted to continue despite ever-increasing cost and schedule delays exposes a major flaw in U.S. nuclear weapons acquisition programs – they are too big to fail. The government, evidently, will always write a bigger check, will always move the goalposts, because the alternative is either failing to maintain the U.S. strategic deterrent or admitting that U.S. nuclear strategy and force structure is not as immutable and unquestionable as the public has been made to believe. In such a system of blank checks and industry lobbying, what incentivizes the Pentagon to ensure programs are as cost efficient as possible? The only mechanism for oversight and accountability is Congress. Congress must increase oversight of nuclear modernization programs like Sentinel to ensure a limit is placed on how much taxpayer money can be spent on failing programs in the name of national security.

“Critical” Overrun of Sentinel ICBM Program Demands Government Transparency

On January 18th, the Air Force notified Congress that its program for the new Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) being developed by Northrop Grumman will cost 37 percent more than projected and take at least two years longer than estimated–an overrun in ‘critical’ breach of Congress’s Nunn-McCurdy Act. Transparency from the Department of Defense and Congress over the following months will be crucial to understand the causes and consequences and ensure proper public oversight of one of the largest nuclear weapons programs in U.S. history.

What caused the overrun?

While Air Force officials have cited inflation and unexpected infrastructure costs related to command and launch as the primary causes of the overrun, skewed cost estimates since the program’s inception and consequences of unhealthy practices related to industry competition are likely to blame as well.

Infrastructure costs

According to Andrew Hunter, Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, there has been a slight increase in cost of the missile itself, but the cost and schedule growth for the project is largely due to supporting infrastructure costs. The Sentinel program includes not only an entirely new long-range missile but replacement or enhancement of silos, launch command centers, and command and control facilities for the ICBM force. For example, the silos and launch facilities for Sentinel will be significantly larger than for the Minuteman missiles. Additionally, the Air Force had planned to reuse the communications infrastructure from Minuteman III for Sentinel but determined that the system was too old to fully function with the new ICBM, requiring completely new cabling. Kristyn Jones, acting Under Secretary of the Air Force, similarly cited the “massive ‘civil works’ project” as the primary overrun cause.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO)’s annual evaluation of Pentagon weapons programs in June 2023 additionally revealed that the Sentinel program was delayed because Northrop Grumman is experiencing staffing shortfalls, clearance delays, IT infrastructure challenges, and supply chain disruptions. Northrop Grumman was issued a sole-source, $13.3 billion contract for the program in September 2020.

Skewed cost estimates

A 2016 Air Force cost analysis for the Sentinel program (previously known as the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent or GBSD) concluded that replacing the existing force of Minuteman III ICBMs would be cheaper than a life-extension program. The assumptions that led to this assessment, however, were flawed and potentially skewed to favor a full replacement of the ICBM program.

The primary factor leading to the Air Force’s determination that a life-extension of Minuteman ICBMs would be more expensive was the requirement from their Analysis of Alternatives that the ICBM force level be maintained until 2075. This arbitrary requirement for force levels and timeline meant that a life-extension program for Minuteman III ICBMs would have to include the cost of building a follow-on missile to reach the 2075 requirement, ensuring a favorable look for Sentinel. Projections for a program lifespan before or after 2075–like 2050 or 2100–result in cheaper cost estimates for life-extension of Minuteman than development of Sentinel.

As recently as 2021, Air Force Global Strike Command claimed the Sentinel program would be $38 billion cheaper than attempting to upgrade and extend the life of the Minuteman III. After the “critical” cost projection increase was made public, the Air Force insisted that “There is not a viable service life extension program that we can foresee for Minuteman III. It was fielded in the 70s as a 10-year weapon,” even though the Air Force put the Minuteman III through a complete life-extension a decade ago.

The Air Force’s first cost estimate for the Sentinel program in February 2015 was $62.3 billion (in then-year dollars). Just nine months later, the Pentagon’s cost estimation team put the number between $85 billion and $100 billion, already over one-third higher than the original estimate. After setting the estimate at $85 billion in 2016, the Air Force again increased the estimated program cost in 2020 to $95.8 billion. With the recently reported cost overrun of 37 percent, the latest cost estimate for the program––scheduled for release this year––could jump to more than $130 billion.

The Air Force knew that the low cost projection that was used to secure Congressional approval and lock the program in was made with incomplete data. After the newest cost increase was disclosed, the Air Force acknowledged: “Some of the assumptions that were made at the beginning of the program when the initial cost estimates were made were just not particularly valid, and now we have a lot more information that should allow us to stay much closer to the cost estimates that will be developed as part of the Nunn-McCurdy process.”

Industry and competition

One persistent justification for Sentinel voiced by the Air Force is that a new missile program would help protect the large solid rocket motor (LSRM) industrial base that has suffered from consolidation in recent years. In 2018, Northrop Grumman–one of just two competitors for the Sentinel program alongside Boeing–purchased Orbital ATK, one of the two remaining LSRM manufacturers. This acquisition gave Northrop Grumman a significant advantage over Boeing, who ultimately withdrew from the Sentinel competition in 2019, citing “inherently unfair cost, resource and integration advantages.”

With Boeing declining to bid, Northrop Grumman became the sole contract winner for the Sentinel program. Ultimately, the Air Force’s failure to mitigate anti-competitive behavior by Northrop Grumman and its awarding of an unprecedented high-value sole-source contract likely contributed to higher costs for the Sentinel program and a more unhealthy industrial base.

The Nunn-McCurdy process

The Air Force is required to provide the overrun notification to Congress due to the Nunn-McCurdy Act, which mandates that the Pentagon disclose to Congress if a program faces cost or schedule overruns exceeding 15 percent. With a cost overrun of 37 percent, the Sentinel program is in “critical” breach of the Nunn-McCurdy Act, requiring the Secretary of Defense to conduct a root-cause analysis and renewed cost assessment. Following completion of these requirements, the program will be terminated unless the Secretary of Defense certifies the program no later than 60 days after a required Selected Acquisition Report is submitted to Congress.

Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin will engage in these processes over the next several months to uncover the cause of the cost overrun and assess, alongside the Pentagon’s Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation. Together, they will determine:

- the estimated cost of the program if no changes are made to the current requirements,

- the estimated cost of the program if requirements are modified,

- the estimated cost of reasonable alternatives to the program, and

- the extent to which funding from other programs will need to be cut to cover the cost growth of this program.

The certification required to keep the program alive must then certify, in the exact words of the legislation, that: [author context and commentary added below]

- the program is essential to national security, [How will Secretary Austin certify this? Expert analysis has identified cheaper and more efficient alternatives to the Sentinel program and challenged the necessity of ICBMs in the U.S. arsenal.]

- the new cost estimates have been determined by the Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation to be reasonable, [What is the standard for ‘reasonable’? Will this determination consider cheaper alternatives to the Sentinel program, such as a life-extension program of the Minuteman III ICBM? The details of this determination should be made public to ensure proper oversight, given that a Pentagon official will be making the determination for a defense program.]

- the program is a higher priority than programs whose funding will be reduced to cover the increased cost of this program, and [What programs will be cut to pay for the Sentinel program? Will only other defense programs be at risk? That information and the method of determining priority should be available to the public.]

- the management structure is sufficient to control additional cost growth. [The continuous delays and cost growth of the Sentinel program reveal a persistent failure in program management. Any certification presented by Secretary Austin must address this failure and explain how the management structure will be altered to address it.]

If the program avoids termination, the Nunn-McCurdy Act requires that it be restructured to rectify the root cause of the overrun and receive new milestone approval. Even before the review has been completed, the Air Force argues the Sentinel program will not be canceled: “Sentinel will be funded. We’ll make the trades that it takes to make that happen.” Those “trades” may include reduction or even cancellation of other programs or asking Congress to further increase the defense budget.

Implications for force structure

Although the news and forthcoming processes related to the Sentinel overrun are largely focused on cost, the two-year schedule overrun could have critical implications for U.S. nuclear force structure as well.

Pentagon documents have previously indicated that a two-year programmatic slippage could result in up to 35 ICBMs being removed from alert status. While several analysts have questioned the continued U.S. requirement for 400 deployed ICBMs, a provision included in each National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) since FY 2017 legally prohibits the number of deployed ICBMS from dropping below 400. The 2023 Congressional Strategic Posture Commission appeared to acknowledge a possible dip in the ICBM number by recommending the Air Force plan to deploy the Sentinel in a MIRVed configuration.

In order to prevent this slippage, according to senior Air Force and Northrop officials, the two-year delay in achieving initial operational capability (IOC) means the Air Force will have to life-extend some Minuteman III ICBMs, something senior officials have previously argued was not possible. In defense of the Sentinel program in 2021, then-Commander of USSTRATCOM Adm. Charles Richard said, “you cannot life extend the Minuteman 3,” and argued the system is “so old that in some cases the drawings don’t exist any more.” While Sentinel is meant to replace the Minuteman missiles, the two programs will have to operate simultaneously for some time due to the delay, which will add additional cost. This delay also puts Sentinel’s IOC beyond the no-fail IOC date of September 2030 set by Air Force Global Strike Command.

Incomplete data, rosy cost projections, and excessive secrecy appear to have combined to push the Sentinel program deep into the red. Institutional preference of getting a new weapon system rather than operating an existing missile for another decade or two has probably been another factor; the technical-cost assessment of a Minuteman III life-extension has never been made public.

The Pentagon and/or Congress should make all steps and results of this Sentinel review process open to the public to ensure maximum transparency, scrutiny, and oversight. Secretary Austin’s likely certification of the Sentinel program should be open to public interrogation, and Congress must thoroughly examine whether every certification requirement is met. Congress should ask the Government Accountability Office and Congressional Budget Office to make independent reviews. The Sentinel program has been plagued with cost increases, flawed assumptions, and misleading arguments from the beginning; this most recent overrun demands a reassessment of the Pentagon’s justification for Sentinel and hawk-eyed scrutiny of the program’s next steps.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

The U.S. Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Force: A Post-Cold War Timeline

The Pentagon is currently planning to replace its current arsenal of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) with a brand-new missile force, known as the Sentinel (previously called the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent, or GBSD); it was previously estimated to cost approximately $100 billion in acquisition fees and $264 billion throughout its lifecycle until 2075 (in Then-Year dollars); however, the price tag has since risen substantially, calling the program’s future into question.

Below, you will find a comprehensive timeline of all relevant actions taken relating to the ICBM force since the end of the Cold War, including force posture alterations, international treaties, congressional efforts, government studies, and milestones in the Sentinel acquisition process.

The United States and Soviet Union sign the START Treaty.

START prohibited each country from deploying more than 6,000 nuclear warheads deployed on up to 1,600 strategic delivery vehicles. At the time, the United States’ ICBM force comprised 450 single-warhead Minuteman IIs, 500 three-warhead Minuteman IIIs, and 50 ten-warhead Peacekeeper MX missiles––for a total of 2,450 warheads attributed to 1,000 ICBMs.

27 September 1991

President Bush announces the de-alerting and eventual retirement of all 450 Minuteman II ICBMs.

With the Cold War coming to a close, President Bush took the first steps toward reducing the United States’ land-based nuclear force under the direction of the newly-signed START Treaty.

The first Minuteman II ICBM is removed from Ellsworth Air Force Base’s Golf-02 silo near Red Owl, South Dakota.

The last Minuteman II ICBM at Ellsworth Air Force Base was withdrawn from its silo in April 1994, and the 44th Missile Wing became formally inactive in July 1994.

The United States and Russia sign the START II Treaty.

In order to comply with START II’s ban on ICBMs with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), the Pentagon planned to retire its 50 Peacekeeper MX ICBMs and de-MIRV its Minuteman III fleet, for an expected future ICBM force of 500 warheads attributed to 500 Minuteman III ICBMs; however, START II never entered into force. After the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT) was signed in 2002, President George Bush eventually did retire the Peacekeepers and download many of the MIRV’ed warheads from the Minuteman III force.

June 1993

GAO publishes an evaluation of the proposed Minuteman III Guidance Replacement Program.

At the time, the Air Force hoped to begin replacing the Minuteman III’s guidance systems with upgraded versions. The GAO’s evaluation, titled” Minuteman III Guidance Replacement Program Had Not Been Adequately Justified,” noted that the Air Force’s own assessments “are not identifying any Minuteman III missile guidance set system-level performance concerns. To the contrary, for the last several years the Minuteman III missile guidance set flight reliability has improved.”

The study further assessed that “missile guidance set failure rates have remained at an acceptable level, with no adverse failure rate trends,” and quoted a previous Air Force study which suggested that “there is no conclusive evidence of degradation within the Minuteman III missile guidance set that cannot be corrected on a case-by-case basis.”

Ultimately, Congress chose to fully fund the $1.6 billion program, which was completed in December 2008.

10 June 1993

GAO publishes its evaluation of the US nuclear modernization program.

The GAO’s evaluation included several notable passages:

p. 5: “We found that the Soviet threat to the weapon systems of the land and sea legs had also been overstated. For the sea leg, this was reflected in unsubstantiated allegations about likely future breakthroughs in Soviet submarine detection technologies, along with underestimation of the performance and capabilities of our own nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines. The projected threat to the sea leg was, however, used frequently as a justification for costly modernizations in the other legs to ‘hedge’ against SSBN vulnerability. Our specific finding, based on operational test results, was that submerged SSBNs are even less detectable than is generally understood, and that there appear to be no current or long-term technologies that would change this. Moreover, even if such technologies did exist, test and operational data show that the survivability of the SSBN fleet would not be in question.”

pp. 6-7, 14: “Compared to ICBMs, no operationally meaningful difference in time to target was found,” further noting that “SSBNs are in essentially constant communication with national command authorities and, depending on the scenario, SLBMs from submarine platforms would be almost as prompt as ICBMs in hitting enemy targets.”

pp. 7-8: “In comparing performance and cost across the legs and weapon systems of the triad, we were concerned to find little or no prior recent effort by DOD to do what we were doing––that is, evaluate comprehensively the relative effectiveness of similar weapon systems. Yet such agency evaluation is critical if limited budget dollars are to be concentrated on programs that are both needed and effective. With regard to proposed upgrades, we found many instances of dubious support for claims of their high performance; insufficient and often unrealistic testing; understated cost; incomplete or unrepresentative reporting; lack of systematic comparison against the systems they were to replace; and unconvincing rationales for their development in the first place. Where mature programs were concerned, on the other hand, we often found that their performance was understated and that inappropriate claims of obsolescence had been made. […] Perhaps the most important point here is that comparative evaluation across the three legs of the triad–and between individual weapon systems and their proposed upgrades–has been signally lacking. This is unfortunate because it deprives policymakers in both the executive branch and the Congress of information they need for making decisions involving hundreds of billions of dollars.”

p. 14: Nuclear “[command, control, and communications] to SSBNs is about as prompt and as reliable as to ICBMs, under a range of conditions.”

1994

The Clinton administration releases its Nuclear Posture Review.

The first comprehensive review of the United States’ nuclear posture in the post-Cold War era was launched by the Department of Defense under Secretary Les Aspin. The Clinton administration’s Nuclear Posture Review working groups, convened by future Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, considered several proposals that would have eliminated the ICBM force entirely––including Carter’s suggestion to adopt a “monad” of 10 submarines carrying 24 Trident missiles with six warheads each––however, these proposals were quickly shot down. Ultimately, it was decided that ICBMs would remain part of the US nuclear deterrent.

5 December 1994

The START Treaty enters into force.

The START Treaty, signed three years earlier, was the first post-Cold War bilateral arms control treaty to reduce global nuclear arsenals and resulted in an 80 percent reduction of all strategic nuclear weapons in the world at the time of its implementation. The treaty expired in December 2009 and would later be replaced by New START, which was signed by the United States and Russia in 2010.

Rapid Execution and Combat Targeting (REACT) upgrade program completed.

The REACT system, originally conceived in the early 1980s, made it possible to retarget the entire Minuteman fleet in under ten hours, and––most critically––allowed missileers to continuously retarget individual missiles as necessary. Although the upgrade was painted at the time as primarily a means of reducing crew fatigue, it also further entrenched the idea of nuclear weapons as “flexible” tools that could be called upon in warfighting scenarios––a strain of thought that continues to dominate nuclear deterrence thinking to this day.

15 December 1997

The Minuteman II elimination process is completed.

The last Minuteman II silo––Hotel-11, near Dederick, Montana––was imploded on 15 December 1997, formally completing the Minuteman II elimination process.

Propulsion Replacement Program (PRP) begins.

The PRP was a life-extension program for the Minuteman III that extended the service lives of approximately 600 solid rocket motors by re-manufacturing all three stages. The first PRP-extended missile was deployed at Malmstrom in April 2001.*

*David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 395.

Guidance Replacement Program (GRP) begins.

The GRP was a life-extension program for the Minuteman III that replaced both the electronic components of the missile guidance set control and the inertial measurement instruments contained within the gyro-stabilized platform.* The first GRP missile was installed on 3 August 1999 in launch facility I-09 at Malmstrom Air Force Base.**

*David Spires, On Alert: An Operational History of the United States Air Force Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-2011 (Colorado Springs: United States Air Force, 2012), p. 174.

**David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 397.

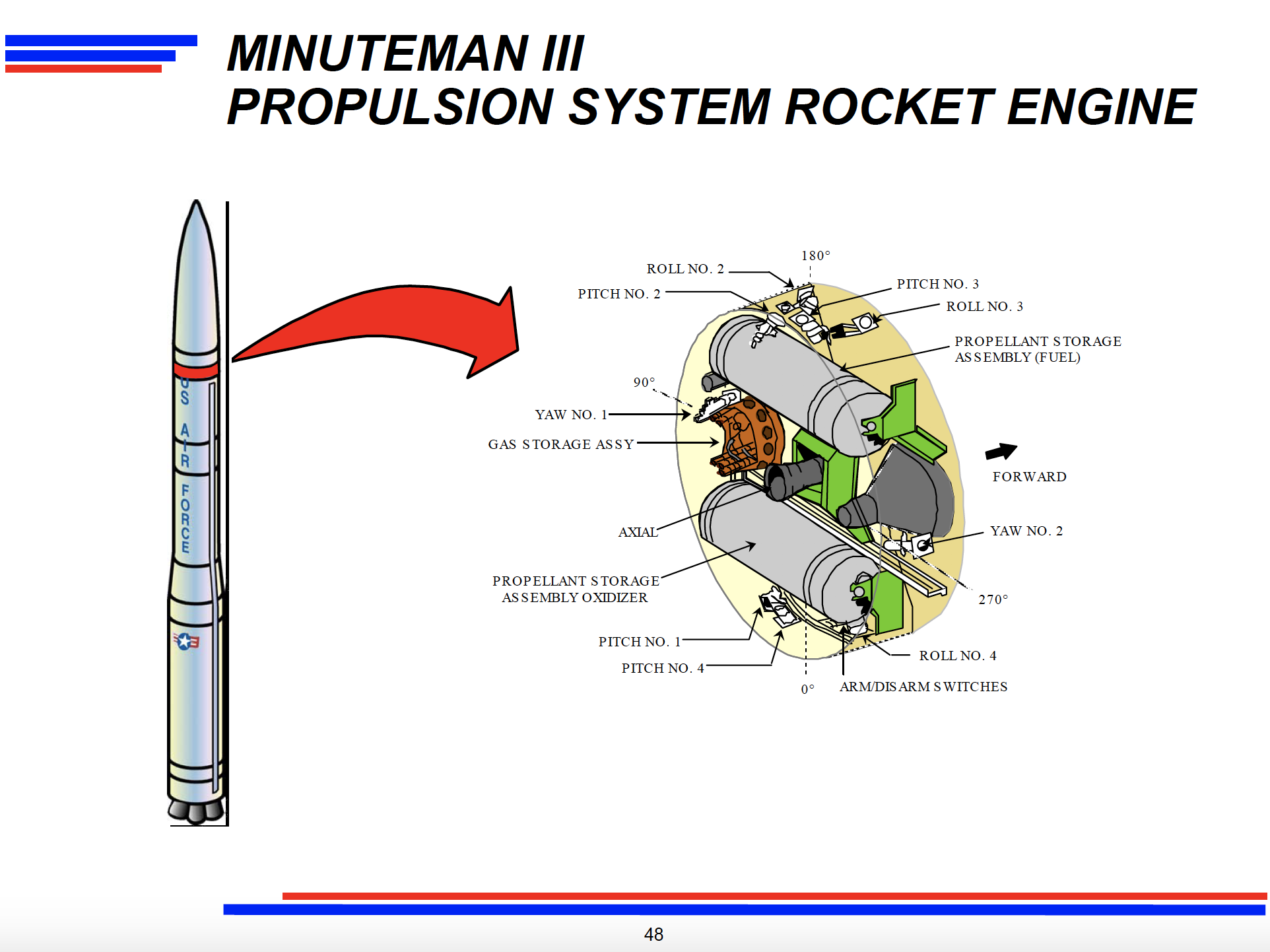

Propulsion System Rocket Engine (PSRE) life-extension program begins.

The PSRE life-extension program was initiated in February 2000 to sustain the Minuteman III missiles’ post-boost propulsion system. The program included the manufacture of 586 PSRE modification kits and cost approximately $107 million to complete.*

*David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 395.

8 January 2002

Bush administration publishes its Nuclear Posture Review.

This review established a “New Triad” composed of nuclear and non-nuclear offensive strike systems, active and passive defenses, and a responsive defense infrastructure. The report also called for a reduction in the US nuclear arsenal.

The United States and Russia sign the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT).

Both parties agreed to reduce their nuclear arsenals to between 1,700 and 2,200 operationally deployed warheads each. SORT entered into force on June 1, 2003, and was eventually superseded by the New START Treaty.

October 2002

The Air Force begins to decommission all 50 Peacekeeper ICBMs.

After almost twenty years of service, the LGM-118 Peacekeeper (MX) was phased out as part of the START II agreement (later bypassed by the SORT Treaty) with Russia.

September 2005

The Air Force deactivates the last remaining Peacekeeper ICBM.

As part of the Peacekeeper deactivation, the rockets were converted and repurpose for exploratory space missions (satellite launchers) and the W87 warheads were deployed on the Minuteman III missiles.

6 February 2006

Quadrennial Defense Review announces the reduction of the deployed Minuteman III force from 500 to 450.

The Department of Defense released the QDR in the fifth year of the War in Afghanistan. This review promoted the “New Triad” strategy proposed by the 2002 Nuclear Posture review and emphasized more tailorable approaches to deterrence. The QDR also announced the elimination of 50 additional ICBMs from service, for a remaining force of 450 ICBMs.

Rapid Execution and Combat Targeting (REACT) Service Life-Extension Program (SLEP) completed.

This upgrade modified the Minuteman launch control centers to combine the communications system and weapons system into one console, thereby reducing the number of keys for a launch and the time needed to retarget the ICBM force. The effort was identified as “essential to the future nuclear force,” according to the 2002 Nuclear Posture Review.*

*David Spires, On Alert: An Operational History of the United States Air Force Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-2011 (Colorado Springs: United States Air Force, 2012), p. 178.

October 2006

As part of the SERV program, the Minuteman III three-warhead MIRVs were converted to the single Mk21 reentry vehicles that were previously carried by the Peacekeeper missile. The first SERV Minuteman III was deployed with the 90th Missile Wing at F.E. Warren Air Force Base and placed on alert on 1 January 2007.*

*David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 396.

17 October 2006

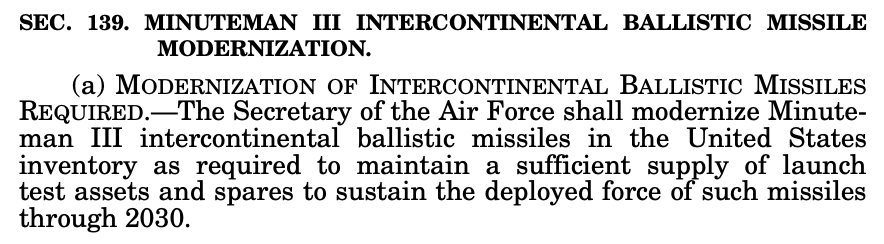

Congress passes the FY 2007 Defense Appropriations Act.

Sec. 139 directs the Secretary of the Air Force to “modernize Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles in the United States inventory as required to maintain a sufficient supply of launch test assets and spares to sustain the deployed force of such missiles through 2030.” This amendment proved to be incredibly 18 consequential because, as Air Force historian David N. Spires describes, “Although Air Force leaders had asserted that incremental upgrades, as prescribed in the analysis of land-based strategic deterrent alternatives, could extend the Minuteman’s life span to 2040, the congressionally mandated target year of 2030 became the new standard.”*

*David Spires, On Alert: An Operational History of the United States Air Force Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-2011 (Colorado Springs: United States Air Force, 2012), pp. 184-185.

12 July 2007

The Air Force begins to deactivate the 50 Minuteman III ICBMs scheduled for retirement.

The 564th Missile Squadron, colloquially known as the “Odd Squad,” used different communications and launch control systems from the rest of the Minuteman III force, and was therefore a clear candidate for decommissioning. The entire decommissioning process was completed in approximately one year, with the final Minuteman III removed from its silo on 28 July 2008.*

*David Spires, On Alert: An Operational History of the United States Air Force Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-2011 (Colorado Springs: United States Air Force, 2012), p. 185-186.

December 2008

Guidance Replacement Program (GRP) completed.

The final GRP missile was installed on 18 February 2008 with the 90th Missile Wing at F.E. Warren Air Force Base, and Boeing delivered the final upgraded missile guidance set to the Air Force in December 2008.*

*David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 397.

7 August 2009

Creation of the Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC).

With major command headquarters at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana, AFGSC is responsible for the three ICBM wings and the entire bomber force. Air Force Global Strike Command is the service component to the United States Strategic Command, and its major command mission was formerly under the direction of Strategic Air Command, which was disestablished in 1992.

November 2009

ICBM Coalition publishes first white paper.

In anticipation of the crucial Senate vote on New START ratification, the white paper implied that the Coalition would deliver the crucial votes to support the treaty if the Obama administration committed to maintaining 450 ICBMs equipped with one warhead each.

March 2010

US Strategic Command sends an ICBM memo to Air Force Global Strike Command calling for an immediate start to a follow-on ICBM.

The memo indicates that the Air Force would have to begin a procurement effort for a follow-on ICBM immediately, if the Air Force planned to deploy it in the 2030 timeframe.*

*Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center, Intelligence and Capabilities Integration Directorate (AFNWC/XR), “Request for Information 12122011” (December 2011), US General Services Administration.

6 April 2010

Obama administration releases its Nuclear Posture Review.

The NPR announced the “deMIRV-ing” of the ICBM force, and called for the Pentagon to begin the Analysis of Alternatives process for a follow-on ICBM in fiscal years 2011 and 2012.

The United States and Russia sign the New START Treaty.

Replacing the START I Treaty, New START placed updated limitations on strategic nuclear arms, including a limit of 1,550 nuclear warheads deployed on no more than 700 strategic delivery vehicles. The treaty was set to have a duration of ten years and was extended in January 2021 for an additional five years.

On the same day as the ratification vote, the Obama administration delivered its intended force posture to Congress: the United States would eliminate 30 ICBMs, ultimately retaining a force level of 420 ICBMs with one warhead each. Of the 71 Senators who voted in favor of New START, six of them were members of the Senate ICBM Coalition.

5 February 2011

New START enters into force.

From the date the treaty entered into force, the United States and Russia had seven years to meet the treaty’s central limits on arms reduction. Both parties were in compliance with the central limits in February 2018.

May 2011

Air Force Global Strike Command completes its Capabilities-Based Assessment for the proposed GBSD program.

A Capabilities-Based Assessment (CBA) is one of the earliest elements of the defense acquisition process. It is used to identify the capabilities required to conduct a particular mission, determine whether there are potential capability gaps in the current system and evaluate their associated risks, and provide abstract recommendations for addressing those gaps. This analysis feeds into the subsequent Initial Capabilities Document, which the Air Force completed for the GBSD in May 2012.

December 2011

The Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center issues a Request For Information for the proposed GBSD program.

This RFI – which was based on the conclusions reached in the CBA and still-in-progress Initial Capabilities Document, was intended to solicit “concepts that address modernization or replacement of the ground based leg of the nuclear triad.”* It was one of the first public documents offering significant insight into how the Air Force was imagining the GBSD system at the time. Notably, the Air Force suggested that contractors could “propose innovative deployment and basing strategies, including, but not limited to mobile basing, fixed basing with mobile elements, or hardened silos, in addition to or in place of existing Minuteman III infrastructure.”

*Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center, Intelligence and Capabilities Integration Directorate (AFNWC/XR), “Request for Information RFI-12122011” (December 2011), US General Services Administration.

2012

Safety Enhanced Reentry Vehicle (SERV) conversion for Minuteman III completed.

Although the SERV program was billed as a safety measure due to the new emphasis on configuring the missile fleet with insensitive high explosives, enhanced detonation systems, and other safety features, it also had the practical effect of dramatically improving the Minuteman III’s hard-target kill capability.*

*David Spires, On Alert: An Operational History of the United States Air Force Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-2011 (Colorado Springs: United States Air Force, 2012), pp. 176-178.

May 2012

Joint DOD/DNI Report on Russian strategic forces.

In 2012, the Secretary of Defense and the Director of National Intelligence jointly concluded in a report to Congress that “the only Russian shift in its nuclear forces that could undermine the basic framework of mutual deterrence […] is a scenario that enables Russia to deny the United States the assured ability to respond against a substantial number of highly valued Russian targets following a Russian attempt at a disarming first strike––a scenario that the Department of Defense judges will most likely not occur.”

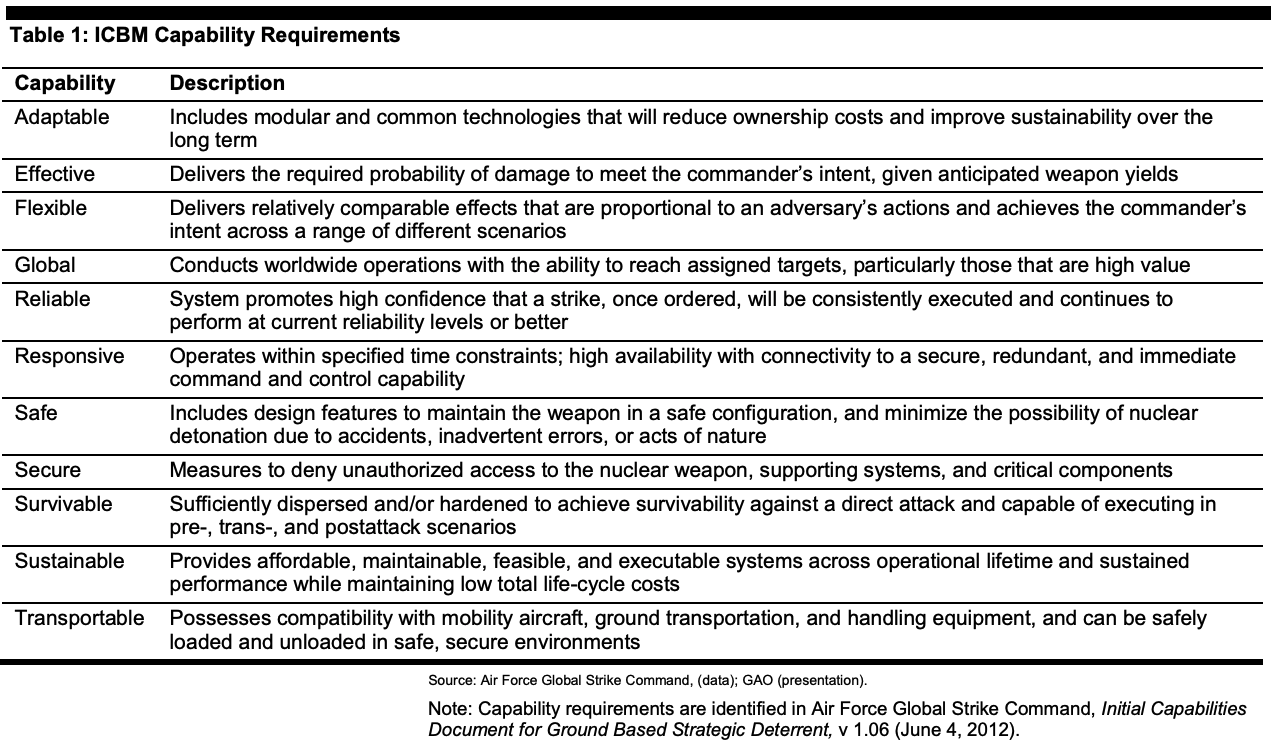

4 June 2012

An Initial Capabilities Document (ICD) further refines the analysis of the Capabilities-Based Assessment, justifies the need for a material change to the system, and provides a list of capabilities that the proposed new system would need to fulfill. This analysis is required for the acquisition process to proceed. The ICD suggested the following capability requirements for the GBSD: adaptable, effective, flexible, global, reliable, responsive, safe, secure, survivable, sustainable, transportable.

July 2012

Revised US nuclear war plan (OPLAN 8010-12) comes into effect.

As Hans Kristensen suggested at the time, “although very different from the [Cold War-era Single Integrated Operational Plan], OPLAN 8010-12 is still thought to be focused on nuclear warfighting scenarios using a Cold War-like Triad of nuclear forces on high alert to hold at risk and, if necessary, hunt down and destroy nuclear (and to a smaller extent chemical and biological) forces, command and control facilities, military and national leadership, and war supporting infrastructure in a myriad of tailored strike scenarios.”

8 August 2012

The Joint Requirements Oversight Council approves the Air Force’s Initial Capabilities Document and directs it to begin the Analysis of Alternatives process.

The Analysis of Alternatives (AoA) process is a critical component of the defense acquisition process. It compares the effectiveness, suitability, and life-cycle costs of each proposed material solution, and is therefore a key document that influences the system’s ultimate development and acquisition.*

*United States Air Force, “Cost Comparison of Extending the Life of the Minuteman III Intercontinental Ballistic Missile to Replacing it with a Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent: Report to Congress,” Department of Defense (July 2016), p. 4.

2013

President Obama directs the Pentagon to reduce the number of circumstances under which the United States would rely on launch-under-attack.

Jon Wolfsthal, former senior director at the National Security Council for arms control and nonproliferation, subsequently described the implications of this decision as follows: “By openly stating that the United States could, and would, sacrifice its ICBMs in a conflict and still fulfill its missions, the country signaled the reliability and strength of its retaliatory forces.”

2013

Propulsion System Rocket Engine (PSRE) life-extension program completed.

This marked the conclusion of the $107 million contract that the Air Force had awarded to TRW in 2000 for refurbishing the Minuteman III’s liquid-propellant, upper-stage engine that operated during the post-boost phase of flight.*

*David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 177.

January 2013

The Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center issues a Broad Agency Announcement for the GBSD program.

The Broad Agency Announcement (BAA) is intended to solicit white papers from industry with the purpose of further developing the GBSD design, specifically with an eye towards exploring new basing concepts. In the BAA, the Air Force listed five basing options for further consideration and refinement: “continued use”, “current fixed”, “new fixed”, “new mobile”, and “new tunnel.”*

*Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center, Program Development and Integration Directorate (AFNWC/XZ), “Broad Agency Announcement BAA-AFNWC-XZ-13-001Rev2” (14 January 2013), US General Services Administration.

30 January 2013

Senate ICBM Coalition writes to incoming Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, critiquing his participation in Global Zero’s 2012 Nuclear Policy Commission Report, which specifically recommended eliminating US ICBMs.

The eight senators wrote to Hagel requesting a clarification regarding his position on ICBMs in a Global Zero report which Hagel had recently co-authored. The letter inquired as to whether Hagel supported eliminating ICBMs and whether he would support the continuation of the Analysis of Alternatives process for the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent.

June 2013

The Obama administration completes its review of US nuclear force posture under New START.

Although the administration ultimately concluded that the United States could reduce its deployed strategic forces by up to “one-third”––down to approximately 1,000-1,100 warheads––press reports indicated that the Pentagon contemplated reducing the arsenal to as low as 500 warheads in a plan known as the “deterrence only” approach.

23 July 2013

Allies of the Senate ICBM Coalition in the House of Representatives help quash an amendment to the FY 2014 National Defense Authorization Act that would reduce the number of ICBMs from 450 to 300.

As Illinois Democrat Rep. Mike Quigley’s amendment was defeated by voice vote, he took to the House floor to lambast his colleagues: “I’ve been here for four years, and I now recognize what the Department of Defense is. It is our jobs program. I respect my colleagues defending jobs in their district. But this isn’t about national security, it’s about job maintenance. That’s not what this is supposed to be about. If we’re going to spend money creating jobs, I want to build bridges, schools, and transit systems.”

25 September 2013

The Senate ICBM Coalition writes to Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel in “strenuous opposition” to the Pentagon’s plan to conduct an environmental assessment on the elimination of ICBM silos.

The environmental assessment would have been prepared as part of the New START implementation process; however, the Coalition called such a move “premature,” suggesting that “Treaty terms do not require the destruction of a single one of the 450 silos housing our Minuteman III force” and that considering such an action “would represent a serious breach of faith.”

18 December 2013

The Senate ICBM Coalition writes another letter to Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, as well as to Pentagon Comptroller Robert Hale, in opposition to the Pentagon’s plan to conduct an environmental assessment on the elimination of ICBM silos.

The letter was very similar in tone and substance to the one sent in September 2013, and advocated for the Pentagon to wait until the passing of the defense appropriations bill before taking any actions related to an ICBM silo environmental assessment.

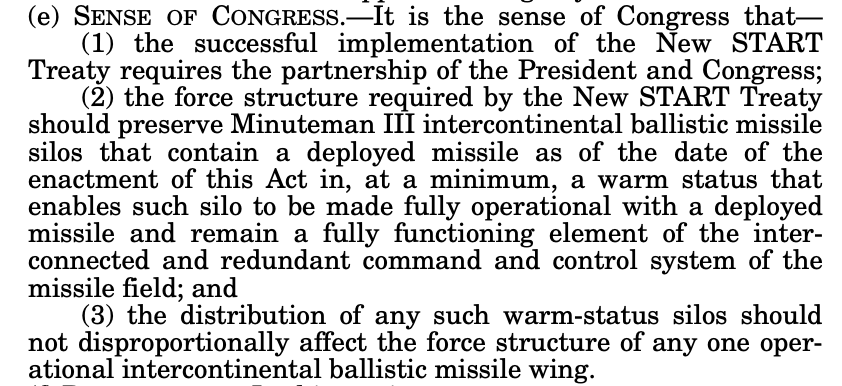

26 December 2013

Congress passes the FY 2014 National Defense Authorization Act.

The bill included a Sense of Congress inserted by allies of the Senate ICBM Coalition which noted that any silos that would soon be emptied due to New START force restructuring should be kept “warm,” so that the silos could be made fully operational on short notice. The amendment also noted that “the distribution of any such warm-status silos should not disproportionately affect the force structure of any one operational intercontinental ballistic missile wing.” This suggests that the Coalition was more preoccupied with economic interests than strategic ones.

17 January 2014

Congress passes the FY 2014 Defense Appropriations Act.

The bill included language inserted by members of the Senate ICBM Coalition that explicitly blocked the Obama administration from conducting the environmental assessment that would be legally necessary to reduce the number of ICBM silos. In a subsequent statement, Coalition members specifically boasted about how they had overruled the Pentagon on the ICBM issue: “the Defense Department tried to find a way around the Hoeven-Tester language, but pressure from the coalition forced the department to back off.”

16 June 2014

Process of downgrading all Minuteman IIIs from three to one warhead completed.

In order to comply with New START, all remaining Minuteman III ICBMs were downgraded from three warheads to just one per missile.*

*John M. LaForge and Arianne S. Peterson, eds. Nuclear Heartland: Revised Edition (Luck, Wisconsin: The Progressive Foundation, Inc., 2015), p. 9.

July 2014

The Air Force completes its Analysis of Alternatives for the GBSD.

The Air Force’s AoA for the GBSD program recommended a complete replacement of the Minuteman III ICBM with The AoA offered four discrete reasons for its consequential recommendation, noting that a replacement would: address capability gaps and improve performance against current and expected threats; maintain the large solid rocket motor industrial base; share subcomponent commonality with the Navy’s ballistic missiles; and be cheaper than the cost of life-extending the Minuteman IIIs.* In hindsight, and upon further scrutiny, these assumptions appear to have either been flawed, exaggerated, or deprioritized.

*United States Air Force, “Cost Comparison of Extending the Life of the Minuteman III Intercontinental Ballistic Missile to Replacing it with a Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent: Report to Congress,” Department of Defense (July 2016), p. 4.

23 January 2015

The Air Force issues another Request For Information for the GBSD program.

In this RFI, the Air Force offered some additional public information about the proposed GBSD weapon system characteristics, specifically noting that they sought a replacement system that “replaces the entire flight system, retains the silo basing mode while recapitalizing the infrastructure, and implements a new Weapon System Command and Control (WSC2) system.”* Additionally, the RFI stated that the GBSD would utilize the existing Mk12A and Mk21 Reentry Vehicles, in addition to a brand-new missile stack and a potentially reduced number of launch control systems and launch facilities.

*Air Force Materiel Command Lifecycle Management Center, Hill Air Force Base, “Request for Information RFI #1, Ground Based Strategic Deterrent,” Contract Opportunity FA8219-15-R-GBSD-RFI1 (23 January 2015).

February 2015

The Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center completes its initial GBSD cost estimate.

The cost estimate of $62.3 billion (in Then-Year dollars) for 642 missiles over a 30-year period was eventually disclosed to the public on 5 June 2015. The total amount includes $48.5 billion for the missiles themselves, $6.9 billion for command and control systems, and $6.9 billion to renovate and upgrade the launch control centers and launch facilities.

November 2015

The Pentagon’s Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation completes its review of the GBSD Program.

The Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE), the Pentagon’s independent budgetary and cost estimation assessment team, estimated that the GBSD would cost between $85 billion and $100 billion (in Then-Year dollars) – a discrepancy more than one-third higher than the Air Force’s original estimate. The Pentagon ultimately selected the lower $85 billion number for the GBSD program.

25 November 2015

Congress passes the FY 2016 National Defense Authorization Act.

The bill specifically prohibited the Pentagon from further reducing the alert level of the ICBM force, with the exception of changes “that are carried out in compliance with the New START treaty.”

8 July 2016

Senate ICBM Coalition sends a letter to Secretary of Defense Ash Carter about GBSD.

The letter asked Carter to recommit to pursuing the GBSD program “as expeditiously as possible,” in light of concerns “that the Administration now may consider steps to slow down modernization programs or withdraw them from future year defense plans.”

29 July 2016

The Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center releases its Request For Proposals for the GBSD Technology Maturation and Risk Reduction contract.

The Technology Maturation and Risk Reduction phase of a defense acquisition program seeks to reduce technology and list-cycle cost risks, and further refine the requirements of the proposed system. In the RFP, the Air Force noted its intention to award up to two contracts for the TMRR phase of the GBSD program, which was scheduled to last approximately 36 months.

23 August 2016

Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics approves the Milestone A decision for the GBSD program.

With the Under Secretary’s decision, the GBSD program formally entered the Technology Maturation and Risk Reduction phase of the acquisition process.* The Acquisition Decision Memorandum that was produced in conjunction with the decision accepted CAPE’s higher estimate of $85 billion for the production of 666 missiles and associated infrastructure costs.

*Now called the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment.

12 October 2016

Deadline for Technology Maturation and Risk Reduction proposals.

The Air Force received three submissions: Boeing, Northrop Grumman, and Lockheed Martin.

December 2016

Senate ICBM Coalition publishes a white paper: “The Enduring Value of America’s ICBMs.”

The paper argued that “The administration and Congress should reject any proposal to delay GBSD or extend the life of Minuteman III beyond the currently-planned 2030 timeframe.”

23 December 2016

Congress passes the FY 2017 National Defense Authorization Act.

The bill included a prohibition on reducing the alert level and quantity of deployed ICBMs below 400––a provision that has since been included in every subsequent NDAA to date.

2 June 2017

Process of removing 50 Minuteman IIIs from their silos is completed.

In order to comply with New START’s central limits, 50 Minuteman III ICBMs were removed from their silos. As Congress had previously mandated, these silos were kept “warm.”

21 August 2017

The Air Force awards TMRR contracts to Boeing and Northrop Grumman.

The Air Force awarded two 36-month contracts for the TMRR phase of the GBSD program – one to Boeing for $349.2 million (FA8219-17-C-0001) and one to Northrop Grumman for $328.6 million (FA8219-17-C-0002). Nine days later, Lockheed Martin announced its intention not to protest its exclusion from the competition.

17 September 2017

Northrop Grumman agrees to terms of purchase with Orbital ATK for approximately $7.8 billion.

Over the past several decades, corporate consolidation in the defense industry had dramatically reduced the number of large solid rocket motor producers in the United States. In 1990 there were five, by 2017 there were only two remaining––Orbital ATK and Aerojet Rocketdyne. To that end, Northrop Grumman’s acquisition of Orbital ATK offered it a serious bidding advantage over Boeing––its only competitor for the GBSD program.

October 2017

The Congressional Budget Office estimates the cost of US nuclear modernization to be $1.2 trillion.

The CBO estimated that if the United States delayed GBSD for two decades, then approximately $42 billion (in 2017 dollars) of the costs of replacing the Minuteman IIIs would be pushed beyond 2046. This would allow the total costs of nuclear modernization to be spread out over several decades and alleviate significant budgetary pressures over the coming years. If GBSD was ultimately cancelled, the CBO estimated that this would save $120 billion (in 2017 dollars).

12 December 2017

Congress passes the FY 2018 National Defense Authorization Act.

The bill prevented the Air Force from awarding an engineering and manufacturing development contract for the GBSD that would reduce the number of fixed launch control centers below current levels, unless the Commander of STRATCOM overruled it. This provision, however, was not included in subsequent NDAAs and appears to have been overridden, as the Air Force’s recent Environmental Impact Statement announcement appears to indicate a significant reduction in each missile wing’s launch control centers––from the current 15 to an eventual eight per wing.

5 February 2018

Both the United States and Russia reach compliance with New START’s central limits.

By this time the United States and Russia were required to meet the Treaty’s central limits of 800 deployed and non-deployed land-based intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) launchers and deployed and non-deployed nuclear-capable heavy bombers; 700 deployed ICBMs, deployed SLBMs, and deployed nuclear-capable heavy bombers; and 1,550 deployed warheads.

March 2018

The Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center drafts a memo seeking “Justification and Approval (J&A) for Other Than Full and Open Competition” for the GBSD program.

Since “full and open competition” for contracts is required by law, an awarding agency must submit a “Justification and Approval” (J&A) request in order to circumvent this procedure. The Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center’s J&A request suggested that limiting the solicitation of the GBSD’s Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD) contract to just two bidders––Boeing and Northrop Grumman––would be acceptable because “typically, expected cost savings from a competition come from a competition premium––the cost savings which come from competing a contract rather than soliciting a single supplier. In this case, the [Air Force] expects to obtain a competition premium despite the exclusion of sources, because the selection will be a competition between the two TMRR offerors [sic].”* Given that the EMD contract was ultimately sole-sourced to Northrop Grumman in September 2020, these expected cost savings are unlikely to be realized. The J&A request was ultimately approved by Assistant Secretary of the Air Force William B. Roper, Jr. on 26 February 2019.

*“Justification and Approval (J&A) for Other Than Full and Open Competition,” GBSD program document approved by William B. Roper, Jr., Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Acquisition, Technology & Logistics), 26 February 2019.

June 2018

Northrop Grumman acquires Orbital ATK for $7.8 billion.

The Federal Trade Commission investigated the merger over concerns that it could “substantially lessen competition and […] create a monopoly in the relevant market for missile systems.” Specifically, the FTC expressed concerns that “If Northrop were to foreclose its missile system prime contractor competitors in any of these ways, the United States Government would be harmed because cost of missile systems may increase, innovation may be lessened, and/or quality would be reduced because the United States Government would be less likely to obtain the best possible combination of missile system prime contractor and SRM supplier.” The FTC ultimately did not block the acquisition; however, it ruled that Northrop Grumman was required to “not Discriminate in any Missile Competition where Northrop is currently competing to be the Prime Contractor.” Specifically, Northrop Grumman would have to make its solid rocket motor products and services fully available to Boeing and would not be permitted to share Boeing’s proprietary data with other parts of the Northrop Grumman corporation to gain leverage over its competitor in other projects.

March 2019