Elevate and Strengthen the Presidential Management Fellows Program

Founded in 1977, the Presidential Management Fellows (PMF) program is intended to be “the Federal Government’s premier leadership development program for advanced degree holders across all academic disciplines” with a mission “to recruit and develop a cadre of future government leaders from all segments of society.” The challenges facing our country require a robust pipeline of talented and representative rising leaders across federal agencies. The PMF program has historically been a leading source of such talent.

The next Administration should leverage this storied program to reinvigorate recruitment for a small, highly-skilled management corps of upwardly-mobile public servants and ensure that the PMF program retains its role as the government’s premier pipeline for early-career talent. It should do so by committing to placing all PMF Finalists in federal jobs (rather than only half, as has been common in recent years), creating new incentives for agencies to engage, and enhancing user experience for all PMF stakeholders.

Challenge and Opportunity

Bearing the Presidential Seal, the Presidential Management Fellows (PMF) Program is the Federal Government’s premier leadership development program for advanced degree holders across all academic disciplines. Appropriately for a program created in the President’s name, the application process for the PMF program is rigorous and competitive. Following a resume and transcript review, two assessments, and a structured interview, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) selects and announces PMF Finalists.

Selection as a Finalist is only the first step in a PMF applicant’s journey to a federal position. After they are announced, PMF Finalists have 12 months to find an agency posting by completing a second round of applications to specific positions that agencies have designated as eligible for PMFs. OPM reports that “over the past ten years, on average, 50% of Finalists obtain appointments as Fellows.” Most Finalists who are placed are not appointed until late in the eligibility period: halfway through the 2024 eligibility window, only 85 of 825 finalists (10%) had been appointed to positions in agencies.

For applicants and universities, this reality can be dispiriting and damage the reputation of the program, especially for those not placed. The yearlong waiting period ending without a job offer for about half of Finalists belies the magnitude of the accomplishment of rising to the top of such a competitive pool of candidates eager to serve their country. Additionally, Finalists who are not placed in a timely manner will be likelier to pursue job opportunities outside of federal service. At a moment when the federal government is facing an extraordinary talent crisis with an aging workforce and large-scale retirements, the PMF program must better serve its purpose as a trusted source of high-level, early-career talent.

zThe current program design also affects the experience of agency leaders—such as hiring managers and Chief Human Capital Officers (CHCOs)—as they consider hiring PMFs. When agencies hire a PMF for a 2-year placement, they cover the candidate’s salary plus an $8,000 fee to OPM’s PMF program office to support its operations. Agencies consider hiring PMF Finalists with the knowledge that the PMF has the option to complete a 6-month rotational assignment outside of their hiring unit. These factors may create the impression that hiring a PMF is “costlier” than other staffing options.

Despite these challenges, the reasons for agencies to invest in the PMF program remain numerous:

- It remains intensely competitive and desirable for applicants; in 2024, the program had an 11.5% acceptance rate.

- PMFs are high quality hires: 87% of PMFs took a permanent or term position in government following the completion of their two-year fellowship.

- The PMF alumni network includes celebrated career and political leaders across government.

- The PMF program is a leading source of general management talent, with strong brand equity to reach this population.

The PMF is still correctly understood as the government’s premier onramp program for early career managerial talent. With some thoughtful realignment, it can sustain and strengthen this role and improve experience for all its core stakeholders.

Plan of Action

The next Administration should take a direct hand in supporting the PMF Program. As the President’s appointee overseeing the program, the OPM Director should begin by publicly setting an ambitious placement percentage goal and then driving the below reforms to advance that goal.

Recommendation 1. Increase the Finalist placement rate by reducing the Finalist pool.

The status quo reveals misalignment between the pool of PMF Finalists and demand for PMFs across government. This may be in part due to the scale of demand, but is also a consequence of PMF candidates and finalists with ever-broader skill sets, which makes placement more challenging and complex. Along with the 50% placement rates, the existing imbalance between finalists and placements is reflected in the decision to contract the finalist pool from 1100 in 2022 to 850 in 2023 and 825 in 2024. The next Administration should adjust the size of the Finalist pool further to ensure a near-100% placement rate and double down on its focus on general managerial talent to simplify disciplinary matching. Initially, this might mean shrinking the pool from the 825 advanced in 2024 to 500 or even fewer.

The core principle is simple: PMF Finalists should be a valuable resource for which agencies compete. There should be (modestly) fewer Finalists than realistic agency demand, not more. Critically, this change would not aim to reduce the number of PMFs serving in government. Rather, it seeks to sustain the current numbers while dramatically reducing the number of Finalists not placed and creating a healthier set of incentives for all parties.

When the program can reliably boast high placement rates, then the Federal government can strategize on ways to meaningfully increase the pool of Fellows and use the program to zero in on priority hard-to-hire disciplines outside of general managerial talent.

Recommendation 2. Attach a financial incentive to hiring and retaining a PMF while improving accountability.

To underscore the singular value of PMFs and their role in the hiring ecosystem, the next Administration should attach a financial incentive to hiring a PMF.

Because of the $8,000 placement fee, PMFs are seen as a costlier route than other sources of talent. A financial incentive to hire PMFs would reverse this dynamic. The next Administration might implement a large incentive of $50,000 per Fellow, half of which would be granted when a Fellow is placed and the other half to be granted when the Fellow accepts a permanent full-time job offer in the Federal government. This split payment would signal an investment in Fellows as the future leaders of the federal government.

Assuming an initial cohort of 400 placed Fellows at $50,000 each, OPM would require $20 million plus operating costs for the PMF program office. To secure funds, the Administration could seek appropriations, repurpose funds through normal budget channels, or pursue an agency pass-the-hat model like the financing of the Federal Executive Board and Hiring Experience program offices.

To parallel this incentive, the Administration should also implement accountability measures to ensure agencies more accurately project their PMF needs by assigning a cost to failing to place some minimum proportion–perhaps 70%–of the Finalists projected in a given cycle. This would avoid too many unplaced Finalists. Agencies that fail to meet the threshold should have reduced or delayed access to the PMF pool in subsequent years.

Recommendation 3. Build a Stronger Support Ecosystem

In support of these implementation changes, the next Administration should pursue a series of actions to elevate the program and strengthen the PMF ecosystem.

Even if the Administration pursues the above recommendations, some Finalists would remain unpaired. The PMF program office should embrace the role of a talent concierge for a smaller, more manageably-sized cohort of yet-unpaired Finalists, leveraging relationships across the government, including with PMF Alumni and the Presidential Management Alumni Association (PMAA) and OPM’s position as the government’s strategic talent lead to encourage agencies to consider specific PMF Finalists in a bespoke way. The Federal government should also consider ways to privilege applications from unplaced Finalists who meet criteria for a specific posting.

To strengthen key PMF partnerships in agencies, the Administration should elevate the role of PMF Coordinators beyond “other duties as assigned” to a GS-14 “PMF Director.” With new incentives to encourage placement and consistent strategic orientation from agency partners, agencies will be in a better position to project their placement needs by volume and role and hire PMF Finalists who meet them. PMF Coordinators would have explicit performance measures that reflect ownership over the success of the program.

The Administration must commit and sustain senior-level engagement—in the White House and at the senior levels of OMB, OPM, and in senior agency roles including Deputy Secretaries, Assistant Secretaries for Management, and Chief Human Capital Officers—to drive forward these changes. It must seize key leverage points throughout the budget and strategic management cycle, including OPM’s Human Capital Operating Plan process, OMB’s Strategic Reviews process, and the Cross-Agency Priority Goal setting rhythms. And it must sustain focus, recognizing that these new design elements may not succeed in their first cycle, and should provide support for experimentation and innovation.

Conclusion

For decades, the PMF program has consistently delivered top-tier talent to the federal government. However, the past few years have revealed a need for reform to improve the experience of PMF hopefuls and the agencies that will undoubtedly benefit from their skills. With a smaller Finalist pool, healthier incentives, and a more supportive ecosystem, agencies would compete for a subsidized pool of high-quality talent available to them at lower cost than alternative route, and Fellows who clear the significant barrier of the rigorous selection process would have far stronger assurance of a placement. If these reforms are successfully implemented, esteem for the government’s premier onramp for rising managerial talent will rise, contributing to the impression that the Federal government is a leading and prestigious employer of our nation’s rising leaders.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

The PMF program is a 2-year placement with an optional 6-month rotation in another office within the appointing agency or another agency. The rotation is an important and longstanding design element of a program aiming to build a rising cohort of managerial talent with a broad purview. While the current program requires agencies pay OPM the full salary, benefits, and a placement fee for placing a PMF, the one quarter rotation may act as a barrier to embracing PMF talent. This can be addressed by adding a significant subsidy to balance this concern.

In the current program, OPM uses a rule of thumb to set the number of Finalists at approximately 80% of anticipated demand to minimize the number of unplaced Finalists. This is a prudent approach, reflected in shifting Finalist numbers in recent years: from 1100 in 2022 to 850 in 2023 and 825 in 2024. Despite adjusting the Finalist pool, unfortunately placement rates have remained near 50%. Agencies are failing to follow-through on their projected demand for PMFs, which has unfortunate consequences for Finalists and presents management challenges for the PMF program office.

This reform proposal would take a large step by reducing the Finalist pool to well below the stated demand–500 or less–and focus on general managerial talent to make the pairing process simpler. This would be, fundamentally, a temporary reset to raise placement rates and improve user experience for candidates, agencies, and the program management team. As placement rhythms strengthen along the lines described above, there is every reason for the program to grow.

The subsidy proposed for placing a PMF candidate would not require a net increase in federal expenditures. In the status quo, all costs of the PMF program are borne by the government: agencies pay salaries and benefits, and pay a fee to OPM at the point of appointment. This proposal would surface and centralize these costs and create an agency incentive through the subsidy to hire PMFs, either by “recouping” funds collected from agencies through a pass-the-hat revolving fund or “capitalizing” on a central investment from another source. In either case, it would ensure that PMF Finalists are a scarce asset to be competed for, as the program was envisioned, and that the PMF program office manages thoughtful access to this asset for the whole government, rather than needing to be “selling” to recover operational costs.

Reform Government Operations for Significant Savings and Improved Services

The federal government is dramatically inefficient, duplicative, wasteful, and costly in executing the common services required to operate. However, the new Administration has an opportunity to transform government operations to save money, improve customer experience, be more efficient and effective, consolidate, reduce the number of technology platforms across government, and have significantly improved decision-making power. This should be accomplished by adopting and transforming to a government-wide shared service business model involving the collective efforts of Congress, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), General Services Administration (GSA), and oversight agencies, and be supported by the President Management Agenda (PMA). In fact, this is a real opportunity for the newly created Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) to realize a true systemic transformation to a better and more streamlined government.

Challenge and Opportunity

The federal government is the largest employer in the world with many disparate mission-centric functions to serve the American people. To execute mission objectives, varied mission support functions are necessary, yet costly with many disconnected and inefficient layers added over many years. For example, a hiring action costs over $10,000 in the federal government vs. $4,000 in the private sector, and transactions such as paying an invoice cost hundreds of dollars compared to $1–2 in other sectors. Many support functions—such as travel management, FOIA management, background investigations, human resources, financial management, facilities management, and more — are equally costly and inefficient.

While these functions are critical to helping government programs achieve their mission, over many years they have grown costly and inefficient through high staffing ratios, duplication of technology platforms, disparate data systems, lack of standardization, and poor modernization. Congress focuses on individual agencies independently and not holistically on the opportunity for government-wide efficiency. Because improving operations has no mandate and GSA serves only in a coordinating role, agencies are free to approach operations any way they wish, resulting in a lack of standardization and the interoperability of systems. Many systems are still operating on extremely old software code, and the Administration and Congress lack government-wide data capacity to have the facts they need to govern. With a burdening national debt, we need to streamline government. To illustrate this opportunity, the federal government operates hundreds of human resources functions, whereas Walmart, the second largest U.S. employer with two million employees, operates just two, one for American and one for Europe.

There are several small examples in government demonstrating the ability to realize large cost savings and improved services. When the NASA shared services operations were established, it saved over $200 million through consolidation in their first several years. The consolidation of federal payroll services from 24 to 4 functions saved over $3.2 billion. The Technology CEO Council report “The Government We Need” estimated savings of over $1 trillion by the federal government moving to shared services. Commercial sector entities such as Johnson & Johnson saved approximately $2 billion in just two years.

Plan of Action

Over 85% of Fortune 500 companies and growing numbers of public sector governments around the world have committed to shared services as a mainstream business model. Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, Singapore, and others have realized significant reduction in cost and improved delivery. While shared services have been attempted in many forms since the 1980s in the federal government, implementation has been inconsistent and incomplete due to Congressional and Administration inattention. As part of past PMAs, a GSA Office of Shared Solutions and Performance (OSSPI) was established, along with a Technology Management Fund (TMF) to support modernization, yet little action has been taken to set goals and achieve results. Most government shared service centers operate on antiquated technology platforms, are at high risk of failure, and are in critical need of modernization.

Immediate legislative and executive action are necessary to enable robust, cross-government benefits. Transforming government into an efficient and effective operation will take time, measurement, and accountability. It’s important that this be done correctly and begin by building the requisite capacity to realize success and regularly report to the Administration and Congress. To ensure success, the following initial actions should be taken:

- Congress should make the consolidation of common service operating and business models statutorily mandatory and provide resources for GSA to conduct the appropriate analysis, design, and transformation to consolidated common services.

- The Administration should install the leadership with the responsibility, authority, and accountability for transforming government operations. This would be a Senate-confirmed Commissioner of Government Operations at GSA directing operations with policy authority resting with the OPM Deputy Director for Management (DDM).

- The Administration should enhance GSA/OSSPI to create an effective governance structure and increase their capacity and role. Governance would be structured through the DDM, the GSA Commissioner for government operations, the establishment of a Shared Services Advisory Board (SSAB) made up of agency Deputy Secretaries, and the inclusion of the existing chief operating councils. OSSPI would take on the lead role for transformation and operations oversight and have the staff resources and authority necessary to execute.

- Congress should direct and the Administration should conduct a deep analysis and design the most effective operating and business models. It is necessary to identify current resources, cost, and performance as well as benchmarks against other entities. This would be led by GSA and conducted by an independent, non-conflicted entity. Based on this analysis GSA would design optimized models, provide a clear business case, and prepare a transformation/modernization plan. The Commission would then approve and recommend further Congressional and/or executive action required to implement the transformation. In parallel, GSA would develop selected government staff and managers to participate in the analysis and transformation process.

- The Administration, through OMB and GSA, should implement the multi–year transformation and modernization effort and implement, measure, report results, and realize the requisite Return on Investment (ROI).

These initial activities should cost approximately $80 million and be cost-neutral by allocating funding from existing redundant operational and modernization efforts. This would fund cross-government analysis, GSA operations, government staff training, and transformation planning with an ROI to the taxpayer. Impacted federal staff would be retrained in new associated shared services roles and/or other mission support functions where needed.

Conclusion

The time to act boldly is now. The Administration needs to immediately begin reducing costs and improving services to taxpayers and government programs through the implementation of a shared services business model with strong leadership, a proven approach, and accountability to demonstrate results. Trillions of dollars fed back into supporting governments financial needs are necessary and attainable.

Onboarding Critical Talent in Days: Establishing a Federal STEM Talent Pool

It often takes the federal government months to hire for critical science and technology (STEM) roles, far too slow to respond effectively to the demands of emerging technologies (e.g., artificial intelligence), disasters (COVID), and implementing complex legislation (CHIPS). One solution is for the Federal Government to create a pool of pre-vetted STEM talent to address these needs. This memo outlines how the federal government can leverage existing authorities and hiring mechanisms to achieve this goal, making it easier to respond to staffing needs for emerging policies, technologies, and crises in near-real time.

To lead the effort, the White House should appoint a STEM talent lead (or empower the current Tech Talent Task Force Coordinator or Senior Advisor for Talent Strategy). The STEM talent lead should make a national call to action for scientists and technologists to join the government. They should establish a team in the Executive Office of the President (EOP) to proactively recruit and vet candidates from underrepresented groups, and establish a pool of talent that is available to every agency on-demand.

Challenge and Opportunity

In general, agencies are lagging in adopting best practices for government hiring. This includes the Subject Matter Expert Qualifications Assessment (SMEQA, a hiring process that replaces simple hiring questionnaires with efficient subject-matter-expert-led interviews), shared certificate hiring (which allow qualified but unsuccessful candidates to be hired into similar roles without having to reapply or re-interview), flexible hiring authorities (which allow the government to recruit talent for critical roles (e.g. cybersecurity) more efficiently and allow for alternative work arrangements, such as remote work), proactive sourcing (individual identification and relationship building), and continuous recruiting.

Failure to effectively leverage these hiring tools leads to significant delays in federal hiring, which in turn makes it difficult or impossible for the federal government to nimbly handle rapidly emerging and evolving STEM issue areas (e.g., AI, cybersecurity, extreme weather, quantum computing) and to execute on complex implementation demands.

There is an opportunity to correct this failure by empowering a STEM talent lead in the White House. The talent lead would work with agencies to build a national pool of pre-vetted STEM talent, with the goal of making it possible for federal agencies to fill critical roles in a matter of days – especially when crises strike. This will save the government time, effort, and money while delivering a better candidate experience, which is critical when hiring for in-demand roles.

Plan of Action

The federal government should adopt a four-part plan of action to realize the opportunity described above.

Recommendation 1. Hire and empower a STEM talent lead for critical hiring needs

The next administration should recruit, hire, and empower a STEM talent lead in the Executive Office of the President. The STEM lead should be offered a senior role, either political (Special Assistant to the President) or a senior-level civil service role. The role should sit in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and report to the OSTP director. The STEM talent lead would be tasked with coordinating hiring for critical STEM roles throughout the government. Similar roles currently exist, but are limited to specific subject areas. For instance, the Tech Talent Task Force Coordinator coordinates tech talent policy in an effort to scale hiring and manages a task force that seeks to align agency talent needs. The Senior Advisor for Talent Strategy serves a similar function. The Senior Advisor leads a “tech surge” at the Office of Management and Budget, pulling together workforce and technology policy implementation, including efforts to speed up hiring. Either of these roles could be elevated to the STEM lead, or a new position could be created.

The STEM talent lead would also coordinate government units that have already been established to help deliver STEM talent to federal agencies efficiently. Such units include the United States Digital Service, 18F, Presidential Innovation Fellows, the Lab at the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), the Department of Homeland Security’s Artificial Intelligence Corps, and the Digital Corps at the General Services Administration. The STEM talent lead should be empowered to pull experts from these teams into OSTP for short details to define critical hiring needs. The talent lead should also be responsible for coordinating efforts among the various groups. The goal would not be to supplant the operations of these individual groups, rather to learn from and streamline government-wide efforts in critical fields.

Recommendation 2. Proactive, continuous hiring for key roles across the government

The STEM talent lead should work with the administration and agencies to define the most critical and underrepresented scientific and technical skill sets and identify the highest impact placement for them in the federal government. This is currently being done under the Executive Order on Artificial Intelligence which could be expanded to include all STEM needs. The STEM Lead should establish sourcing strategies and identify prospective hires, possibly building on OPM’s Talent Network goals.

The lead should also collaborate with public and private subject matter experts and use approved and tested hiring processes, such as SMEQA and shared certificates, to pre-vet candidates. These experts would then be placed on a government-wide hiring certificate so that every federal agency could make them a job offer. Once vetted and placed on a government-wide hiring certificate, experts would be available for agencies to onboard within days.

Recommendation 3. Implement a “shared-certificate-by-default” policy

Traditionally, more than one qualified applicant will apply to a federal job opening. In most cases, one applicant will be chosen and the rest rejected, even if the government (even the same agency) has another open role for the same job class. This creates an unnecessary burden on qualified applicants and the government. Qualified applicants should only have to apply once when multiple opportunities exist for the same or similar jobs. This exists, to a limited extent, for excepted service applicants but not for everyone. To achieve this, all critical, scientific, and national security roles should default to shared hiring certificates. Sharing hiring certificates is an approved federal policy but is not the default. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) could issue a policy memo making shared certificates the default, and then work with the OPM to implement it.

Furthermore, the STEM talent lead should coordinate a centralized list of qualified applicants who were not chosen off of shared certificates if they opt-in to receiving job offers from other agencies. This functionality, called “Talent Programs,” has been piloted through USAJobs but has had limited success due to a lack of centralized support.

Recommendation 4. Let departing employees remain available for rapid re-hire into federal roles

Departing staff in critical roles (as determined by the STEM talent lead; see Recommendation 2) with good performance reviews should be offered an opportunity to join a central pool of experts that are available for rehire. The government invests heavily in hiring, training, and providing security clearances to employees with an expectation that they will serve long careers. 20+ year careers, however, are no longer the norm for most applicants. Increasingly, talent is lost to burnout, lack of opportunity inside government, or a desire to do something different. Current policy offers only “reinstatement” benefits, which allow former federal employees to apply for jobs without competing with the broader public. Reinstatement job seekers are still required to apply from scratch to individual positions.

Former employees are a critical group when staffing up quickly. Immediate access to staff with approved security clearances is particularly critical in national emergencies. Former employees also bring their prior training and cultural awareness, making them more effective, quicker than new hires. To incentivize participation from departing employees, the government could offer to maintain their security clearance, give them access to their Thrift Savings Plan and/or medical insurance, and other benefits. This could be piloted through existing authorities (e.g., as intermittent consultants) and OMB and/or OPM could develop a new retention policy based on the outcomes of that pilot.

Conclusion

The federal government needs to establish processes to proactively recruit for key roles, help every qualified candidate get a job, and rapidly respond to STEM staffing needs for critical and complex policies, technologies, and crises. A central pool of science and technology experts can be called upon to fill permanent roles, respond to emergencies, and provide advisory services. Talent can enter and exit the pool as needed, providing the government access to a broad set of skills and experience to pull from immediately.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Yes. It can take several months to establish and execute a government-wide hiring action, especially when relying on OPM for approvals. Once a candidate is vetted and placed on a shared certificate, however, the only delay in hiring is an individual agency’s onboarding procedure. Some agencies are already able to hire in days, others will need support refining their processes if they want the fastest response times.

Yes, both processes are approved by OPM and have been implemented many times with positive results. Despite their success, they remain a small portion of overall hiring processes.

The government has diverse talent, just not enough of it. Pooled and government-wide hiring are ways to leverage limited skill sets to increase the number of experts in any given field. In other words, these are approaches that use critical talent from several agencies to vet potential hires that can be distributed to agencies without the expertise to vet the talent themselves. In this way, talent is seeded throughout the government. Those experts can then ramp up hiring in their own agency, accelerating the hiring of critical skills.

While there are costs to developing these capabilities they will likely be offset in the short term by savings in agencies that no longer need to run time-consuming and labor-intensive job searches. The government will benefit from having fewer people with more expertise operating a centralized service. This program also builds on work that has already been piloted, such as SMEQA and Talent Networks which could also be streamlined to provide greater government-wide efficiency.

Given the government-wide nature of the project, it could be funded in subsequent years through OMB’s Cross Agency Priority (CAP) process, which takes place at the end of the fiscal year. CAP recovers unspent funds from federal agencies to fund key projects. The CAP process was used to successfully scale the SMEQA process and the Digital IT Acquisition Program (DITAP), both of which were similar in scope to this proposal.

It is unlikely that this proposal would increase retirements. The problem recently faced by the Secret Service is a program where agents can retire and then take on part-time work after retirement.

The proposal in this memo, by contrast, focuses on pre-retirement-age personnel who are leaving federal service for a variety of reasons. The goal is to make it easier for this pool to rejoin either permanently (pre-vetted for competitive hiring), temporarily (using non-competitive hiring authorities or political avenues), or as advisors (intermittent consultants).

Reinstatement is the process of rejoining the federal government after having served for a minimum of three years. The benefit of reinstatement is that applicants can apply for non-public jobs, where they compete for jobs against internal candidates rather than the public. Reinstatement requires applicants to apply to individual jobs.

By entering the STEM talent pool, this memo envisions that candidates in critical roles with positive performance reviews would not have to apply for jobs. Instead, agencies looking to hire for critical roles would be able to offer a candidate from this pool a job (without the candidate having to apply). If the candidate accepts, the agency would then be able to onboard them immediately.

Critical roles will and should change over time. Part of the duties of the STEM talent lead would be to continually research and define the emerging needs of the STEM workforce and proactively define what roles are critical for the government.

Yes, but it is often hard to find and decipher. FedScope contains federal hiring data that can be mined for insights. For example, 45% of Federal STEM employees who separated from large agencies from 2020-2024 were people who quit, rather than retired from service. The average length of service has dropped since 2019 and is far below retirement age (11.6 years). Internal federal data has also shown a significant drop in IT employees (2210 series jobs) under the age of 35 across CFO Act agencies.

Where should this office be located in the Federal Government?

The most likely place to pilot the STEM talent team would be in the Executive Office of the President, either as a political role (e.g., Special Assistant to the President) in the Office of Science and Technology Policy or limited-term career role (e.g., Senior Leader or Scientific and Professional). The White House’s authority to coordinate and convene experts from across the government makes it an ideal location to operate from at first. Proximity to the President would make it easier to research critical roles throughout government, coordinate the efforts of disparate hiring programs throughout government, and recruit applicants.

Ultimately, however, the team could be piloted anywhere in the government with sufficient centralized authority. After a defined pilot period, the team may benefit from moving into a less political environment. The team should be founded in an environment that is friendly to iteration, risk-taking, and policy coordination.

Better Hires Faster: Leveraging Competencies for Classifications and Assessments

A federal agency takes over 100 days on average to hire a new employee — with significantly longer time frames for some positions — compared to 36 days in the private sector. Factors contributing to extended timelines for federal hiring include (1) difficulties in quickly aligning position descriptions with workforce needs, and (2) opaque and poor processes for screening applicants.

Fortunately, federal hiring managers and HR staffing specialists already have many tools at their disposal to accelerate the hiring process and improve quality outcomes – to achieve better hires faster. Inside and outside their organizations, agencies are already starting to share position descriptions, job opportunity announcements (JOAs), assessment tools, and certificates of eligibles from which they can select candidates. However, these efforts are largely piecemeal and dependent on individual initiative, not a coordinated approach that can overcome the pervasive federal hiring challenges.

The Office of Personnel Management (OPM), Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Chief Human Capital Officers (CHCO) Council should integrate these tools into a technology platform that makes it easy to access and implement effective hiring practices. Such a platform would alleviate unnecessary burdens on federal hiring staff, transform the speed and quality of federal hiring, and bring trust back into the federal hiring system.

Challenge and Opportunity

This memo focuses on opportunities to improve two stages in the federal hiring process: (1) developing and posting a position description (PD), and (2) conducting a hiring assessment.

Position Descriptions. Though many agencies require managers to review and revise PDs annually, during performance review time, this requirement often goes unheeded. Furthermore, volatile occupations for which job skills change rapidly – think IT or scientific disciplines with frequent changes to how they practice (e.g., meteorology) or new technologies that upend how analytical skills (e.g., data analytics) are practiced – can result in yet more changes to job skills and competencies embedded in PDs.

When a hiring manager has an open position, a current PD for that job is necessary to proceed with the Job Opportunity Announcement (JOA)/posting. When the PD is not current, the hiring manager must work with an HR staffing specialist to determine the necessary revisions. If the revisions are significant, an agency classification specialist is engaged. The specialist conducts interviews with hiring managers and subject-matter experts and/or performs deeper desk audits, job task analyses, or other evaluations to determine the additional or changed job duties. Because classifiers may apply standards in different ways and rate the complexity of a position differently, a hiring manager can rarely predict how long the revision process will take or what the outcome will be. All this delays and complicates the rest of the hiring process.

Hiring Assessments. Despite a 2020 Executive Order and other directives requiring agencies to engage in skills-based hiring, agencies too often still use applicant self-certification on job skills as a primary screening method. This frequently results in certification lists of candidates who do not meet the qualifications to do the job in the eyes of hiring managers. Indeed, a federal hiring manager cannot find a qualified candidate from a certified list approximately 50% of the time when only a self-assessment questionnaire is used for screening. There are alternatives to self-certification, such as writing samples, multiple-choice questions, exercises that test for particular problem-solving or decision-making skills, and simulated job tryouts. Yet hiring managers and even some HR staffing specialists often don’t understand how assessment specialists decide what methods are best for which positions – or even what assessment options exist.

Both of these stages involve a foundation of occupation- and grade-level competencies – that is, the knowledge, skills, abilities, behaviors, and experiences it takes to do the job. When a classifier recommends PD updates, they apply pre-set classification standards comprising job duties for each position or grade. These job duties are built in turn around competencies. Similarly, an assessment specialist considers competencies when deciding how to evaluate a candidate for a job.

Each agency – and sometimes sub-agency unit – has its own authority to determine job competencies. This has caused different competency analyses, PDs, and assessment methods across agencies to proliferate. Though the job of a marine biologist, Grade 9, at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is unlikely to be considerably different from the job of a marine biologist, Grade 9 at the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), the respective competencies associated with the two positions are unlikely to be aligned. Competency diffusion across agencies is costly, time-consuming, and duplicative.

Plan of Action

An Intergovernmental Platform for Competencies, PDs, Classifications, and Assessment Tools to Accelerate and Improve Hiring

To address the challenges outlined above, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Chief Human Capital Officers (CHCO) should create a web platform that makes it easy for federal agencies to align and exchange competencies, position descriptions, and assessment strategies for common occupations. This platform would help federal hiring managers and staffing specialists quickly compile a unified package that they can use from PD development up to candidate selection when hiring for occupations included on the platform.

To build this platform, the next administration should:

- Invest in creating Position Description libraries starting with the unitary agencies (e.g. the Environmental Protection Agency) then broadening out to the larger, disaggregated ones (e.g., the Department of Health and Human Services). Each agency should assign individuals responsible for keeping PDs in the libraries current at those agencies. Agencies and OPM would look for opportunities to merge common PDs. OPM would then aggregate these libraries into a “master” PD library for use within and across agencies. OPM should also share examples of best-in-class JOAs associated with each PD. This effort could be piloted with the most common occupations by agency.

Adopt competency frameworks and assessment tools already developed by industry associations, professional societies and unions for their professions. These organizations have completed the job task analyses and have developed competency frameworks, definitions, and assessments for the occupations they cover. For example, IEEE has developed competency models and assessment instruments for electrical and computer engineering. Again, this effort could be piloted by starting with the most common occupations by agency, and the occupations for which external organizations have already developed effective competency frameworks and assessment tools. - Create a clearinghouse for assessments at OPM indexed to each occupation associated in the PD Library. Assign responsibility to lead agencies for those occupations responsible for the PDs to keep the assessments current and/or test banks robust to meet the needs of the agencies. Expand USA Hire and funding to provide open access by agencies, hiring managers, HR professionals and program leaders.

- Standardize classification determinations for occupations/grade levels included in the master PD library. This will reduce interagency variation in classification changes by occupation and grade level, increase transparency for hiring managers, and reduce burden on staffing specialists and classifiers.

- Delegate authority to CHCOs to mandate use of shared, common PDs, assessments, competencies, and classification determinations. This means cleaning up the many regulatory mandates that do not already designate the agency-level CHCOs with this delegated authority. The workforce policy and oversight agencies (OPM, OMB, Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)) need to change the regulations, policies, and practices to reduce duplication, delegate decision making, and lower variation (For example, allow the classifiers and assessment professionals to default to external, standardized occupation and grade-level competencies instead of creating/re-creating them in each instance.)

- Share decision frameworks that determine assessment strategy/tool selection. Clear, public, transparent, and shared decision criteria for determining the best fit assessment strategy will help hiring managers and HR staffing specialists participate more effectively in executing assessments.

- Agree to and implement common data elements for interoperability. Many agencies will need to integrate this platform into their own talent acquisition systems such as ServiceNow, Monster, and USA Staffing. To be able to transfer data between them, the agencies will need to accelerate their work on common HR data elements in these areas of position descriptions, competencies, and assessments.

Data analytics from this platform and other HR talent acquisition systems will provide insights on the effectiveness of competency development, classification determinations, effectiveness of common PDs and joint JOAs, assessment quality, and effectiveness of shared certification of eligible lists. This will help HR leaders and program managers improve how agency staff are using common PDs, shared certs, classification consistency, assessment tool effectiveness, and other insights.

Finally, hiring managers, HR specialists, and applicants need to collaborate and share information better to implement any of these ideas well. Too often, siloed responsibilities and opaque specialization set back mutual accountability, effective communications, and trust. These actions entail a significant cultural and behavior change on the part of hiring managers, HR specialists, Industrial/Organizational psychologists, classifiers, and leaders. OPM and the agencies need to support hiring managers and HR specialists in finding assessments, easing the processes that can support adoption of skills-based assessments, agreeing to common PDs, and accelerating an effective hiring process.

Conclusion

The Executive Order on skills-based hiring, recent training from OPM, OMB and the CHCO Council on the federal hiring experience, and potential legislative action (e.g. Chance to Compete Act) are drivers that can improve the hiring process. Though some agencies are using PD libraries, joint postings, and shared referral certificates to improve hiring, these are far from common practice. A common platform for competencies, classifications, PDs, JOAs, and assessment tools, will make it easier for HR specialists, hiring managers and others to adopt these actions – to make hiring better and faster.

Opportunities to move promising hiring practices to habit abound. Position management, predictive workforce planning, workload modeling, hiring flexibilities and authorities, engaging candidates before, during, and after the hiring process are just some of these. Making these practices everyday habits throughout agency regions, states and programs rather than the exception will improve hiring. Looking to the future, greater delegation of human capital authorities to agencies, streamlining the regulations that support merit systems principles, and stronger commitments to customer experience in hiring, will help remove systemic barriers to an effective customer-/and user-oriented federal hiring process.

Taking the above actions on a common platform for competency development, position descriptions, and assessments will make hiring faster and better. With some of these other actions, this can change the relationship of the federal workforce to their jobs and change how the American people feel about opportunities in their government.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Policy Experiment Stations to Accelerate State and Local Government Innovation

The federal government transfers approximately $1.1 trillion dollars every year to state and local governments. Yet most states and localities are not evaluating whether the programs deploying these funds are increasing community well-being. Similarly, achieving important national goals like increasing clean energy production and transmission often requires not only congressional but also state and local policy reform. Yet many states and localities are not implementing the evidence-based policy reforms necessary to achieve these goals.

State and local government innovation is a problem not only of politics but also of capacity. State and local governments generally lack the technical capacity to conduct rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of their programs, search for reliable evidence about programs evaluated in other contexts, and implement the evidence-based programs with the highest chances of improving outcomes in their jurisdictions. This lack of capacity severely constrains the ability of state and local governments to use federal funds effectively and to adopt more effective ways of delivering important public goods and services. To date, efforts to increase the use of evaluation evidence in federal agencies (including the passage of the Evidence Act) have not meaningfully supported the production and use of evidence by state and local governments.

Despite an emerging awareness of the importance of state and local government innovation capacity, there is a shortage of plausible strategies to build that capacity. In the words of journalist Ezra Klein, we spend “too much time and energy imagining the policies that a capable government could execute and not nearly enough time imagining how to make a government capable of executing them.”

Yet an emerging body of research is revealing that an effective strategy to build government innovation capacity is to partner government agencies with local universities on scientifically rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of their programs, curated syntheses of reliable evaluation evidence from other contexts, and implementation of evidence-based programs with the best chances of success. Leveraging these findings, along with recent evidence of the striking efficacy of the national network of university-based “Agriculture Experiment Stations” established by the Hatch Act of 1887, we propose a national network of university-based “Policy Experiment Stations” or policy innovation labs in each state, supported by continuing federal and state appropriations and tasked with accelerating state and local government innovation.

Challenge

Advocates of abundance have identified “failed public policy” as an increasingly significant barrier to economic growth and community flourishing. Of particular concern are state and local policies and programs, including those powered by federal funds, that do not effectively deliver critically important public goods and services like health, education, safety, clean air and water, and growth-oriented infrastructure.

Part of the challenge is that state and local governments lack capacity to conduct rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of their policies and programs. For example, the American Rescue Plan, the largest one-time federal investment in state and local governments in the last century, provided $350 billion in State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds to state, territorial, local, and Tribal governments to accelerate post-pandemic economic recovery. Yet very few of those investments are being evaluated for efficacy. In a recent survey of state policymakers, 59% of those surveyed cited “lack of time for rigorous evaluations” as a key obstacle to innovation. State and local governments also typically lack the time, resources, and technical capacity to canvass evaluation evidence from other settings and assess whether a program proven to improve outcomes elsewhere might also improve outcomes locally. Finally, state and local governments often don’t adopt more effective programs even when they have rigorous evidence that these programs are more effective than the status quo, because implementing new programs disrupts existing workflows.

If state and local policymakers don’t know what works and what doesn’t, and/or aren’t able to overcome even relatively minor implementation challenges when they do know what works, they won’t be able to spend federal dollars more effectively, or more generally to deliver critical public goods and services.

Opportunity

A growing body of research on government innovation is documenting factors that reliably increase the likelihood that governments will implement evidence-based policy reform. First, government decision makers are more likely to adopt evidence-based policy reforms when they are grounded in local evidence and/or recommended by local researchers. Boston-based researchers sharing a Boston-based study showing that relaxing density restrictions reduces rents and house prices will do less to convince San Francisco decision makers than either a San Francisco-based study, or San Francisco-based researchers endorsing the evidence from Boston. Proximity matters for government innovation.

Second, government decision makers are more likely to adopt evidence-based policy reforms when they are engaged as partners in the research projects that produce the evidence of efficacy, helping to define the set of feasible policy alternatives and design new policy interventions. Research partnerships matter for government innovation.

Third, evidence-based policies are significantly more likely to be adopted when the policy innovation is part of an existing implementation infrastructure, or when agencies receive dedicated implementation support. This means that moving beyond incremental policy reforms will require that state and local governments receive more technical support in overcoming implementation challenges. Implementation matters for government innovation.

We know that the implementation of evidence-based policy reform produces returns for communities that have been estimated to be on the order of 17:1. Our partners in government have voiced their direct experience of these returns. In Puerto Rico, for example, decision makers in the Department of Education have attributed the success of evidence-based efforts to help students learn to the “constant communication and effective collaboration” with researchers who possessed a “strong understanding of the culture and social behavior of the government and people of Puerto Rico.” Carrie S. Cihak, the evidence and impact officer for King County, Washington, likewise observes,

“It is critical to understand whether the programs we’re implementing are actually making a difference in the communities we serve. Throughout my career in King County, I’ve worked with County teams and researchers on evaluations across multiple policy areas, including transportation access, housing stability, and climate change. Working in close partnership with researchers has guided our policymaking related to individual projects, identified the next set of questions for continual learning, and has enabled us to better apply existing knowledge from other contexts to our own. In this work, it is essential to have researchers who are committed to valuing local knowledge and experience–including that of the community and government staff–as a central part of their research, and who are committed to supporting us in getting better outcomes for our communities.”

The emerging body of evidence on the determinants of government innovation can help us define a plan of action that galvanizes the state and local government innovation necessary to accelerate regional economic growth and community flourishing.

Plan of Action

An evidence-based plan to increase state and local government innovation needs to facilitate and sustain durable partnerships between state and local governments and neighboring universities to produce scientifically rigorous policy evaluations, adapt evaluation evidence from other contexts, and develop effective implementation strategies. Over a century ago, the Hatch Act of 1887 created a remarkably effective and durable R&D infrastructure aimed at agricultural innovation, establishing university-based Agricultural Experiment Stations (AES) in each state tasked with developing, testing, and translating innovations designed to increase agricultural productivity.

Locating university-based AES in every state ensured the production and implementation of locally-relevant evidence by researchers working in partnership with local stakeholders. Federal oversight of the state AES by an Office of Experiment Stations in the US Department of Agriculture ensured that work was conducted with scientific rigor and that local evidence was shared across sites. Finally, providing stable annual federal appropriations for the AES, with required matching state appropriations, ensured the durability and financial sustainability of the R&D infrastructure. This infrastructure worked: agricultural productivity near the experiment stations increased by 6% after the stations were established.

Congress should develop new legislation to create and fund a network of state-based “Policy Experiment Stations.”

The 119th Congress that will convene on January 3, 2025 can adapt the core elements of the proven-effective network of state-based Agricultural Experiment Stations to accelerate state and local government innovation. Mimicking the structure of 7 USC 14, federal grants to states would support university-based “Policy Experiment Stations” or policy innovation labs in each state, tasked with partnering with state and local governments on (1) scientifically rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of state and local policies and programs; (2) translations of evaluation evidence from other settings; and (3) overcoming implementation challenges.

As in 7 USC 14, grants to support state policy innovation labs would be overseen by a federal office charged with ensuring that work was conducted with scientific rigor and that local evidence was shared across sites. We see two potential paths for this oversight function, paths that in turn would influence legislative strategy.

Pathway 1: This oversight function could be located in the Office of Evaluation Sciences (OES) in the General Services Administration (GSA). In this case, the congressional committees overseeing GSA, namely the House Committee on Oversight and Responsibility and the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, would craft legislation providing for an appropriation to GSA to support a new OES grants program for university-based policy innovation labs in each state. The advantage of this structure is that OES is a highly respected locus of program and policy evaluation expertise.

Pathway 2: Oversight could instead be located in the Directorate of Technology, Innovation, and Partnerships in the National Science Foundation (NSF TIP). In this case, the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology and the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation would craft legislation providing for a new grants program within NSF TIP to support university-based policy innovation labs in each state. The advantage of this structure is that NSF is a highly respected grant-making agency.

Either of these paths is feasible with bipartisan political will. Alternatively, there are unilateral steps that could be taken by the incoming administration to advance state and local government innovation. For example, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) recently released updated Uniform Grants Guidance clarifying that federal grants may be used to support recipients’ evaluation costs, including “conducting evaluations, sharing evaluation results, and other personnel or materials costs related to the effective building and use of evidence and evaluation for program design, administration, or improvement.” The Uniform Grants Guidance also requires federal agencies to assess the performance of grant recipients, and further allows federal agencies to require that recipients use federal grant funds to conduct program evaluations. The incoming administration could further update the Uniform Grants Guidance to direct federal agencies to require that state and local government grant recipients set aside grant funds for impact evaluations of the efficacy of any programs supported by federal funds, and further clarify the allowability of subgrants to universities to support these impact evaluations.

Conclusion

Establishing a national network of university-based “Policy Experiment Stations” or policy innovation labs in each state, supported by continuing federal and state appropriations, is an evidence-based plan to facilitate abundance-oriented state and local government innovation. We already have impressive examples of what these policy labs might be able to accomplish. At MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab North America, the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab and Education Lab, the University of California’s California Policy Lab, and Harvard University’s The People Lab, to name just a few, leading researchers partner with state and local governments on scientifically rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of public policies and programs, the translation of evidence from other settings, and overcoming implementation challenges, leading in several cases to evidence-based policy reform. Yet effective as these initiatives are, they are largely supported by philanthropic funds, an infeasible strategy for national scaling.

In recent years we’ve made massive investments in communities through federal grants to state and local governments. We’ve also initiated ambitious efforts at growth-oriented regulatory reform which require not only federal but also state and local action. Now it’s time to invest in building state and local capacity to deploy federal investments effectively and to galvanize regional economic growth. Emerging research findings about the determinants of government innovation, and about the efficacy of the R&D infrastructure for agricultural innovation established over a century ago, give us an evidence-based roadmap for state and local government innovation.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

A Public Jobs Board For A Fairer Political Appointee Hiring Process

Current hiring processes for political appointees are opaque and problematic; job openings are essentially closed off except to those in the right networks. To democratize hiring, the next administration should develop a public jobs board for non-Senate-confirmed political appointments, which includes a list of open roles and job descriptions. By serving as a one-stop shop for those interested in serving in an administration, an open jobs board would bring more skilled candidates into the administration, diversify the appointee workforce, expedite the hiring process, and improve government transparency.

Challenge and Opportunity

Hiring for federal political appointee positions is a broken process. Even though political appointees steer some of the federal government’s most essential functions, the way these individuals are hired lacks the rigor and transparency expected in most other fields.

Political appointment hiring processes are opaque, favoring privileged candidates already in policy networks. There is currently no standardized hiring mechanism for filling political appointee roles, even though new administrations must fill thousands of lower-level appointee positions. Openings are often shared only through word-of-mouth or internal networks, meaning that many strong candidates with relevant domain expertise may never be aware of available opportunities to work in an administration. Though the Plum Book (an annually updated list of political appointees) exists, it does not list vacancies, meaning outside candidates must still have insider information on who is hiring.

These closed hiring processes are deeply problematic because they lead to a non-diverse pool of applicants. For example, current networking-based processes benefit graduates of elite universities, and similar networking-based employment processes such as employee referral programs tend to benefit White men more than any other demographic group. We have experienced this opaque process firsthand at the Aspen Tech Policy Hub; though we have trained hundreds of science and technology fellows who are interested in serving as appointees, we are unaware of any that obtained political appointment roles by means other than networking.

Appointee positions often do not include formal job descriptions, making it difficult for outside candidates to identify roles that are a good fit. Most political appointee jobs do not include a written, formalized job description—a standard best practice across every other sector. A lack of job descriptions makes it almost impossible for outside candidates utilizing the Plum Book to understand what a position entails or whether it would be a good fit. Candidates that are being recruited typically learn more about position responsibilities through direct conversations with hiring managers, which again favors candidates who have direct connections to the hiring team.

Hiring processes are inefficient for hiring staff. The current approach is not only problematic for candidates; it is also inefficient for hiring staff. Through the current process, PPO or other hiring staff must sift through tens of thousands of resumes submitted through online resume bank submissions (e.g. the Biden administration’s “Join Us” form) that are not tailored to specific jobs. They may also end up directly reaching out to candidates that may not actually be interested in specific positions, or who lack required specialized skills.

Given these challenges, there is significant opportunity to reform the political appointment hiring process to benefit both applications and hiring officials.

Plan of Action

The next administration’s Presidential Personnel Office (PPO) should pilot a public jobs board for Schedule C and non-career Senior Executive Service political appointment positions and expand the job board to all non-Senate-confirmed appointments if the pilot is successful. This public jobs board should eventually provide a list of currently open vacancies, a brief description for each currently open vacancy that includes a job description and job requirements, and a process for applying to that position.

Having a more transparent and open jobs board with job descriptions would have multiple benefits. It would:

- Bring in more diverse applicants and strengthen the appointee workforce by broadening hiring pools;

- Require hiring managers to write out job descriptions in advance, allowing outside candidates to better understand job opportunities and hiring managers to pinpoint qualifications they are looking for;

- Expedite the hiring process since hiring managers will now have a list of qualified applicants for each position; and

- Improve government transparency and accessibility into critical public sector positions.

Additionally, an open jobs board will allow administration officials to collect key data on applicant background and use these data to improve recruitment going forward. For example, an open application process would allow administration officials to collect aggregate data on education credentials, demographics, and work experience, and modify processes to improve diversity as needed. Having an updated, open list of positions will also allow PPO to refer strong candidates to other open roles that may be a fit, as current processes make it difficult for administration officials or hiring managers to know what other open positions exist.

Implementing this jobs board will require two phases: (1) an initial phase where the transition team and PPO modify their current “Join Us” form to list 50-100 key initial hires the administration will need to make; and (2) a secondary phase where it builds a more fulsome jobs board, launched in late 2025, that includes all open roles going forward.

Phase 1. By early 2025, the transition team (or General Services Administration, in its transition support capacity) should identify 50-100 key Schedule C or non-career Senior Executive service hires they think the PPO will need to fill early in the administration, and launch a revised resume bank to collect applicants for these positions. The transition team should prioritize roles that a) are urgent needs for the new administration, b) require specialized skills not commonly found among campaign and transition staff (for instance technical or scientific knowledge), and c) have no clear candidate already identified. The transition team should then revise the current administration’s “Join Us” form to include this list of 50-100 soon-to-be vacant job roles, as well as provide a 2-3 sentence description of the job responsibilities, and allow outside candidates to explicitly note interest in these positions. This should be a relatively light lift, given the current “Join Us” form is fairly easy to build.

Phase 2. Early in the administration, PPO should build a larger, more comprehensive jobs board that should aim to go live in late 2025 and includes all open Schedule C or non-Senior Executive Service (SES) positions. Upon launch, this jobs board should include open jobs for whom no candidate has been identified, and any new Schedule C and non-SES appointments that are open going forward. As described in further detail in the FAQ section, every job listed should include a brief description of the position responsibilities and qualifications, and additional questions on political affiliation and demographics.

During this second phase, the PPO and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) should identify and track key metrics to determine whether it should be expanded to cover all non-Senate confirmed appointments. For example, PPO and OPM could compare the diversity of applicants, diversity of hires, number of qualified candidates who applied for a position, time-to-hire, and number of vacant positions pre- and post-implementation of the jobs board.

If the jobs board improves key metrics, PPO and OPM should expand the jobs board to all non-Senate confirmed appointments. This would include non-Senate confirmed Senior Executive Service appointee positions.

Conclusion

An open jobs board for political appointee positions is necessary to building a stronger and more diverse appointee workforce, and for improving government transparency. An open jobs board will strengthen and diversify the appointee workforce, require hiring managers to specifically write down job responsibilities and qualifications, reduce hiring time, and ultimately result in more successful hires.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

An open jobs board will attract many applicants, perhaps more than the PPO’s currently small team can handle. If the PPO is overwhelmed by the number of job applicants it can either directly forward resumes to hiring managers — thereby reducing burden on PPO itself — or consider hiring a vetted third-party to sort through submitted resumes and provide a smaller, more focused list of applicants for PPO to consider.

PPO can also include questions to enable candidates to be sorted by political experience and political alignment, so as (for instance) to favor those who worked on the president’s campaign.

Both phases of our recommendation would be a relatively light lift, and most costs would come from staff time. Phase 1 costs will solely include staff time; we suspect it will take ⅓ to ½ of an FTE’s time over 3 months to source the 50-100 high-priority jobs, write the job descriptions, and incorporate them into the existing “Join Us” form.

Phase 2 costs will include staff time and cost of deploying and maintaining the platform. We suspect it will take 4-5 months to build and test the platform, and to source the job descriptions. The cost of maintaining the Phase 2 platform will ultimately depend on the platform chosen. Ideally, this jobs board would be hosted on an easy-to-use platform like Google, Lever, or Greenhouse that can securely hold applicant data. If that proves too difficult, it could also be built on top of the existing USAJobs site.

PPO may be able to use existing government resources to help fund this effort. The PPO may be able to pull on personnel from the General Services Administration in their transition support capacity to assist with sourcing and writing job descriptions. PPO can also work with in-house technology teams at the U.S. Digital Service to actually build the platform, especially given they have considerable expertise in reforming hiring for federal technology positions.

Many Chutes and Few Ladders in the Federal Hiring Process

How hard can it be to hire into the federal government? Unfortunately, for many, it can be very challenging. A recent conversation with a hiring manager at a federal regulatory agency, shed light on some of the difficulties experienced in the hiring process.

A Hiring Experience

This hiring manager – let’s call her Alex – needed to hire someone to join her team and support environmental review efforts (e.g., reviewing the impact of building a road near a wetland) towards the end of 2023. It was a position she had hired for previously, and she had a strong understanding of the skills and knowledge that a candidate would need to be successful in the role.

Luckily, she did not need to create a new job description, classify the position, or create a new assessment. Instead, she was able to use the previous job description, job analysis, and assessment, only making small tweaks. This meant that she just needed to work with the HR Specialist (personnel who provide human resource management services within their agency) to finalize the Job Opportunity Announcement (JOA).

This was happening in December and given the holidays, she decided to wait on posting the JOA until the new year. They posted the announcement in early January and closed the application a week later. Alex publicized the opening through her network on LinkedIn and through other LinkedIn pages.

Anxious to bring a new teammate on board, Alex was quite frustrated to not receive a certified list of candidates from the HR Specialist until four months later. And when she began her review of the candidates, she was surprised to find only one applicant with the experience and skills she was looking for in the role. Alex reached out to the candidate, but learned that they had already accepted a different role.

Feeling disheartened, Alex contacted the HR Specialist to ask for a second list of candidates, explaining the incompatibility of the other applicants in the initial list. Alex waited until June to receive the second list, now six months past the posting date, but she was excited to see several qualified candidates for the role.

Following their evaluation process, Alex made an offer to a candidate from the list. With the tentative offer accepted, they started the background check, which took about two months. The candidate finally started in September, nine months after posting the position.

Now, what happened? Why did it take nine months to fill this position, especially when the job announcement only required small changes?

Mapping the Hiring Process

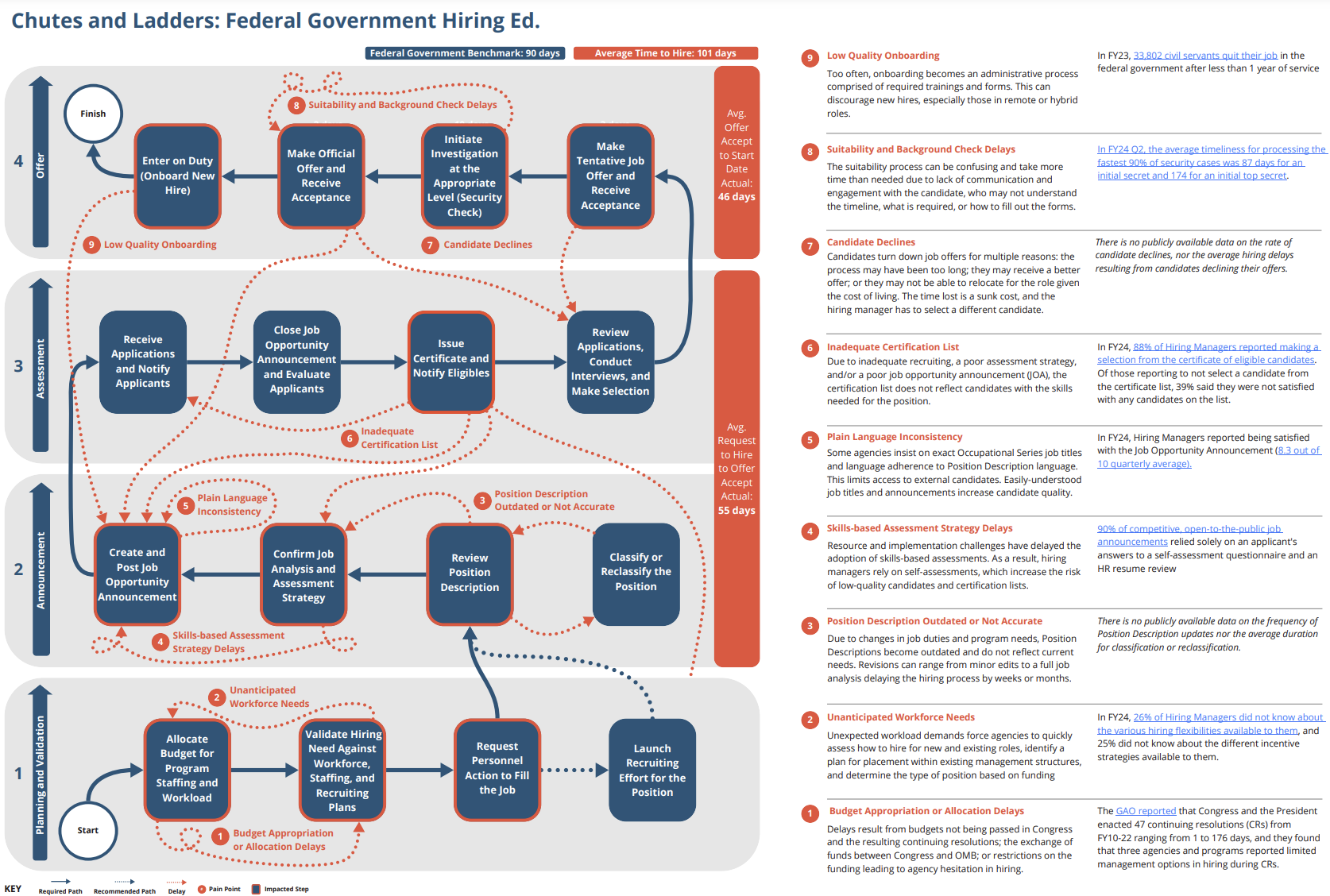

In our recent blog post, we shared how difficult it is to hire into the federal government and cited a number of different challenges (e.g., outdated job descriptions, reclassifying roles, defining an assessment strategy, etc.) hindering the government from building talent capacity. We decided to map out the federal government’s competitive hiring process to illustrate how the hiring process typically works and where pain points often emerge. Through research (e.g., OPM’s Hiring Process Analysis Tool), expert feedback, and practitioner discussions (e.g., interviews with hiring managers, HR specialists, and leaders involved in permitting activities), we outlined the main steps of the hiring process from workforce planning through candidate selection and onboarding. And we found the process to look similar to a game of Chutes and Ladders.

As you’ll see, the hiring process is divided into four major phases: (1) aligning the workforce plan and validating the hiring need, (2) developing and posting a job opportunity announcement, (3) assessing the candidates, and (4) selecting a candidate and making an offer. Distributed throughout this process, we identified nine primary pain points that drive the majority of delays experienced by civil servants.