A Research, Learning, and Opportunity Agenda for Rebuilding Trust in Government

American trust in government institutions is at historic lows. You’ve heard that so many times – we get it! Our series on trust in government functions has given you all the context you might ever desire on why that matters. What we haven’t done yet (and what too few do) is talk about what may be needed to rebuild trust in government institutions, broadly, but also specifically.

At a recent workshop hosted by the Federal of American Scientists, we explored the nature of trust in specific government functions, the risk and implications of breaking trust in those systems, and how we’d known we were getting close to specific trust breaking points. The scenarios we developed were not only meant as cautionary tales, but to serve as reference foundations to plan against for any future reform efforts, should trust continue to decline generally or specifically. But we also started to explore the question of what actions may be needed to rebuild trust from a total breakdown – or, absent that, what we need to know to make that rebuilding possible.

What follows is an opportunity agenda for those invested in rebuilding trust in government functions. Instead of admiring the problem with another dozen think pieces on how dire the situation has been for decades, there’s homework we can do now to build our our trust toolkit. This includes:

- Research Opportunities: questions we don’t know the answer to

- Learning Opportunities: Areas where pilots, experiments, explorations or iteration can test what works

- Design Opportunities: Spaces where we already know enough to start building solutions, but need creativity, co-design, champions, and implementation pathways.

This is just the start, reflecting the dozens of suggestions by workshop participants in our too-short session. You undoubtedly have more (let us know!). What we hope it offers is a list of possibilities for policymakers, academics, funders, and practitioners to deepen understanding and test reforms.

Workforce: Trust as a System-Level Challenge

Research Questions

- How does American’s trust vary between career civil servants, short-term experts, and political appointees?

- What is the relationship between negative news coverage about an agency (e.g., performance or layoffs) and different measures of public engagement with that agency (e.g., application rates to that agency?)

- What incentives might make a national service requirement acceptable to Americans?

- What are current views by college age and early career Americans on public service? How has public service motivation changed?

- What are public and key stakeholder views on “merit,” and do expectations of merit drive trust?

- Are there examples of senior leaders who highlight the work of public servants in the United States, and are trust measures in those locations notably different?

- What approaches may better communicate the compliance and oversight barriers civil servants face (both as a means showing anti-corruption/anti-waste and potentially incentivizing support for barrier reduction)?

- How might Americans better understand the “risk management” or “preventative” role that public servants play?

Learning Opportunities

- Pilot programs: test and learn (or document prior learning from) initiatives like civilian mid-career recruitment (e.g., AI leaders in civilian roles, building on military parallels), national and targeted hiring fairs that generate long-term interests.

- Experiment with models of “frictionless” federal applications and one-stop hiring actions.

- Explore early-career exposure to inspiring public servants as a way to seed pride and long-term interest.

- Explore what would be required to restart proven pathways like PMF and broaden service corps models beyond college grads.

- In states with fewer public sector workforce protections, explore what hiring incentives are most in use/most effective

Design Challenges

- Campaigns to highlight federal workers at local/state/national levels, including “famous names” doing stints in public service.

- Meet mission on a specific, high-salience task (ex. Philly I-95) and connect with a “join us” campaign.

- Expand representation of communicators about federal work and workers beyond spokespeople, encouraging all federal workers to take responsibility of public engagement.

- Instill recruitment and overall workforce health as an SES competency.

Procurement: Trust Through Smarter Buying and Clearer Accountability

Research Needs

- What does a sophisticated sourcing strategy look like (market shaping, competition), and what capacities are missing?

- How might AI reshape procurement—and how might it affect perceptions of fairness and accountability?

- Where should procurement risk and responsibility lie to encourage creative but accountable strategies?

- Consider differentiation between “hard”procurement and “bad”procurement and how to productively learn from each.

Learning Opportunities

- Transparently evaluate agile and creative sourcing pilots.

- Develop, refine, and use vendor and bidder experience surveys as part of trust-building.

- Study the impacts of various kinds of procurement transparency on public confidence (e.g.,taking different approaches around contracts, bids, subcontractors, progress, cost overruns, and past performance)

Design Challenges

- Elevate acquisitions professionals as strategic leaders and outcomes builders, not compliance gatekeepers.

- Begin to build in capacity in priority agencies better oversee modern digital contracts.

- Invest in capacity in key areas for strategic insourcing.

Customer Experience: Trust as an Exercise in Proactive Service and Listening

Research Needs

- How does diminished service quality affect public trust, and how hard is it to earn back?

- Can community trust be influenced by CX improvements? How?

- What role does casework play in shaping congressional perspectives on service delivery?

- Where do Americans think priority public services come from?

Learning Opportunities

- Pilot outcome-driven legislation toolkits to help Congress set goals that agencies are trusted to deliver.

- Pilot agency field-office expansion or deployment opportunities to better meet people where they are for service needs and benefit questions

- Expand testing of approaches to embed resources like user experience, equity impact assessments and trauma-informed practices into service design.

- Pilot casework supports (e.g., staff details) and casework connectivity to federal service communities to better connect Congressional casework and federal services.

- Support communities of practice among CX experts.

Design Challenges

- Educate congressional staffs on appointee CX responsibilities to improve oversight.

- Reduce administrative burdens: plain language, translation, integration across agencies.

- Embed use of authentic co-design and public engagement (including with AI tools) to close feedback loops.

- Expand civic education and change management campaigns to reframe government as a source of pride.

- Link CX and public outcomes transparently through KPIs tied to delivery.

Data: Trust in Evidence, Transparency, Reliability, and Capacity

Research Needs

- How might government (and champions of good government) communicate the importance of federal data to the public in ways that build trust and legitimacy?

- Which datasets are of highest public value (beyond economic value), and what is their role? What are upstream and downstream impacts of changes those data sets?

- How do we evaluate and communicate the staffing and technical capacity needed for robust statistical functions (as a point of comparison, like military readiness)?

- How might we forecast or scenario plan around disappearance of data sets, and how might we plan for future potential reintegration of such datasets? With what sort of governance models?

Learning Opportunities

- Test public AI tools with strong user interfaces to make data more accessible and usable – both increasing utility and also public awareness and investment.

- Pilot, learn from, and grow robust public engagement opportunities around public sector data governance.

- Explore public participation pilots in data collection and governance, particularly among underrepresented groups. Assess what works, what generates impact, what captures imagination.

- As external groups take on data collection, governance, and analytic roles previously held by government, explore and test different models for public governance, ownership, oversight and potential transition plans.

Design Challenges

- Develop public-facing data maps (e.g., Sankey charts of data flows and uses) to visualize and communicate government’s role.

- Strengthen public data governance, potentially through new institutions (e.g., equivalent of the National Assessment Governing Board for education).

- Invest in public sector career development pathways where data skills are rewarded.

Cross-Cutting Directions

Research Needs

- Communicating accountability: What are different successful and unsuccessful models of communicating accountability measures and actions in public sector functions?

- Participatory accountability, oversight, and performance measures: What are more participatory or community based efforts to engage citizens in public oversight, accountability and performance measurement?

- Absence of trust: What are the compliance-based costs of absence of trust in government?

Conclusion

The actions surfaced by participants reflect more than tactical fixes—they point to a research and design agenda for the field. Trust is not just the hoped-for outcome of reform, but the principle that should shape how reforms are tested and evaluated. By pursuing these questions, piloting these ideas, and designing around trust, the government capacity community can help rebuild institutions that are not only effective but also respected, legitimate, and deeply connected to the people they serve.

In Remembrance of Dearly Departed Federal Datasets

On this All Hallow’s Eve, let us recognize the losses of datasets that served the American people

There’s been lots of talk – and some numbers (often in the thousands) – about disappearing federal datasets, especially after many went dark last January when agencies rushed to scrub the perceived spectre of data on gender, DEI, and climate from the public record. Most of those datasets have returned from the dead, some permanently changed by the experience.

Though it’s premature to breathe a sigh of relief – the future of federal data remains in jeopardy – we thought Halloween was an opportune time to ask, which federal datasets have left this mortal realm?

Here’s what we found.

The good news

For the most part, the vast majority of the hundreds of thousands of datasets produced by the federal government are still alive, and have so far escaped mutilation1 or termination. By our rough counts, the datasets that have been truly axed number perhaps in the dozens (not hundreds or thousands).

The bad news

All federal datasets are currently at risk of death by a thousand cuts, weakened by the loss of staff and expertise, contracts, and scientific advisory committees. Just because a given dataset hasn’t been explicitly killed off, doesn’t mean that an agency still has the capacity to collect, protect, process, and publish that data. Also, datasets and variables that do not align with Administration priorities, or might reflect poorly on Administration policy impacts, seem to be especially in the cross-hairs.

The details

We’ve identified three types of data decedents. Examples are below, but visit the Dearly Departed Dataset Graveyard at EssentialData.US for a more complete tally and relevant links.

- Terminated datasets. These are data that used to be collected and published on a regular basis (for example, every year) and will no longer be collected. When an agency terminates a collection, historical data are usually still available on federal websites. This includes the well-publicized terminations of USDA’s Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement, and EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, as well as the less-publicized demise of SAMHSA’s Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN). Meanwhile, the Community Resilience Estimates Equity Supplement that identified neighborhoods most socially vulnerable to disasters has both been terminated and pulled from the Census Bureau’s website.

- Removed variables. With some datasets, agencies have taken out specific data columns, generally to remove variables not aligned with Administration priorities. That includes Race/Ethnicity (OPM’s Fedscope data on the federal workforce) and Gender Identity (DOJ’s National Crime Victimization Survey, the Bureau of Prison’s Inmate Statistics, and many more datasets across agencies).

- Discontinued tools. Digital tools can help a broader audience of Americans make use of federal datasets. Departed tools include EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping tool – known to friends as “EJ Screen” – which shined a light on communities overburdened by environmental harms, and also Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level Data (HIFLD) Open, a digital go-bag of ~300 critical infrastructure datasets from across federal agencies relied on by emergency managers around the country.

Forever in our hearts, and in some cases, given a second life

Another pattern we saw is that some tools have been reincarnated in civil society. Climate Central breathed life back into the U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters database, Public Environmental Data Partners did the same for EJScreen, and Fulton Ring brought back FEMA’s Future Risk Index. All of these tools still depend on the federal data underlying them. Beware, without fresh data to feed on, these tools will turn into the walking dead.

Lurking in the shadows

While our focus now is on deceased federal datasets, other threats loom heavy on the horizon. For example, there are a growing number of examples where the primary federal data remain, but the Administration’s interpretation of that data has veered away from science and toward politics (cases in point: Department of Energy’s July report on the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions on the climate or the CDC’s September guidance on COVID vaccines for children). The data systems aren’t dead, but the implications certainly are scary.

We invite you to take a moment to click through the graveyard of the federal datasets, variables, and tools mentioned above, and more, at the Dearly Departed Dataset Graveyard at EssentialData.US. And if we missed a dataset, please let us know.

Happy Halloween 🎃

Huge thanks to colleagues in the Federation of American Scientists and EssentialData.US, The Impact Project, and Public Environmental Data Partners for the collaboration on this project, and for all who submitted obituaries of their dearly departed datasets.

This analysis includes data, variables, and tools that have been terminated or removed before their time. It represents an attempt to capture substantive data losses and changes above baseline. For example, most data collections for evaluation purposes are not intended to go on indefinitely, and their termination is not included. Additionally, administrations often stand up websites and interactive tools to advance specific policies. We are not cataloging the breadth of such tools that disappeared.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this post described the “System Name” column in the Federal AI Use Case Inventory as missing. In fact, the dataset had been restructured, but still retained that column. We’ll scratch that one off our list of datasets to light a candle for

Innovation Ecosystem Job Board Launches to Connect Federal Talent to Opportunities

In a previous post, we announced an initiative to connect scientists, engineers, technologists, and skilled federal workers and contractors who have recently departed government service with the emerging innovation ecosystems across America that could use their expertise. With the support of FAS, we are now excited to share the launch of the Innovation Ecosystem Job Board. This unique job board contains opportunities from across the nation with the explicit goal of matching in-demand science and technology talent with open positions across the nation’s innovation ecosystems, in roles ranging from lab researchers and data scientists to workforce development practitioners and science communicators.

These innovation ecosystems – namely Tech Hubs and NSF Engines – are advancing critical technologies spanning from advanced manufacturing to quantum computing to biotech, all vital for our national and economic security. To accomplish this work, they operate as multi-stakeholder coalitions that bring together universities, industry, nonprofits, and other partners, all searching for talent to help them fulfill their missions.

These coalitions face growing talent needs, particularly for mission-driven roles that can help drive progress across critical technology areas. Meanwhile, we’re witnessing an exodus of thousands of experienced federal talent from agencies like the National Science Foundation, National Institutes for Health, and the Department of Energy whose knowledge gained from years of managing and working in multimillion-dollar technical programs could be lost entirely if not effectively redeployed.

This initiative directly addresses both challenges by collaborating with innovation ecosystems to identify their immediate talent needs while simultaneously engaging displaced federal workers through job fairs and targeted outreach to understand their backgrounds and geographic preferences. It’s a purposeful approach that ensures mission-driven federal talent can continue contributing to America’s technological leadership. By connecting talent to need, we help strategically imperative innovation ecosystems access the experienced professionals necessary for success.

We will be updating this job board regularly with opportunities from additional Tech Hubs, NSF Engines, and other innovation ecosystems. While our outreach is specifically to former federal workers and contractors, this job board is open to all, and we encourage others on the job hunt to take a look.

As economic policy wonks, we understand that there are often frictions that hinder matching between individuals with the right skills and geographic preferences and the jobs that exist. We are taking this seriously and will engage in what we’re calling “light-touch matching”. Please feel free to fill out this interest form (whether you have applied to a listing on the job board or not), and we will flag profiles that generally align with relevant innovation ecosystems and their needs.

Our process:

We spent the last several months talking to and learning from other talent connectors, innovation ecosystem builders, and the talent themselves. Through facilitated federal roundtables with former federal workers, we understood more deeply their diverse skill sets, their unwavering commitment to mission-driven work, and the unique challenges they face in their current job transition. Work for America’s research on federal workers also validated our hypotheses: these are experienced professionals (59% of survey respondents have a decade or more of experience), are geographically distributed (53% already live outside the DC-Virginia-Maryland area), and are mobile (54% are open to relocating). Job fairs additionally provided us an opportunity to meet individuals leaving the federal government and hear about their backgrounds and interests.

Simultaneously, we reached out to several innovation ecosystems to explore if they had immediate talent needs. Some ecosystems shared their most critical postings among their partners; others had recently conducted surveys of their coalitions to assess available positions and passed that information on to us; still others are actively developing comprehensive approaches to capture all the talent needs across their expansive coalitions. We reviewed and aggregated these opportunities into the job board which is now available and will be regularly updated. We are grateful for all these ecosystems that have engaged in this initiative and we look forward to continuing the conversation with more ecosystems and skilled former federal professionals alike.

Like anything new, this is an experiment. Does this effort in the end successfully match candidates and employers based on skills and geography? If you use this tool, please let us know how it goes!

Maryam Janani-Flores (mjananiflores@fas.org) is a Senior Fellow at FAS and former Chief of Staff at the U.S. Economic Development Administration. Meron Yohannes (myohannes@fas.org) is a Digital Services Alumni Fellow at FAS and most recently served as Senior Policy Advisor for the U.S. Secretary of Commerce.

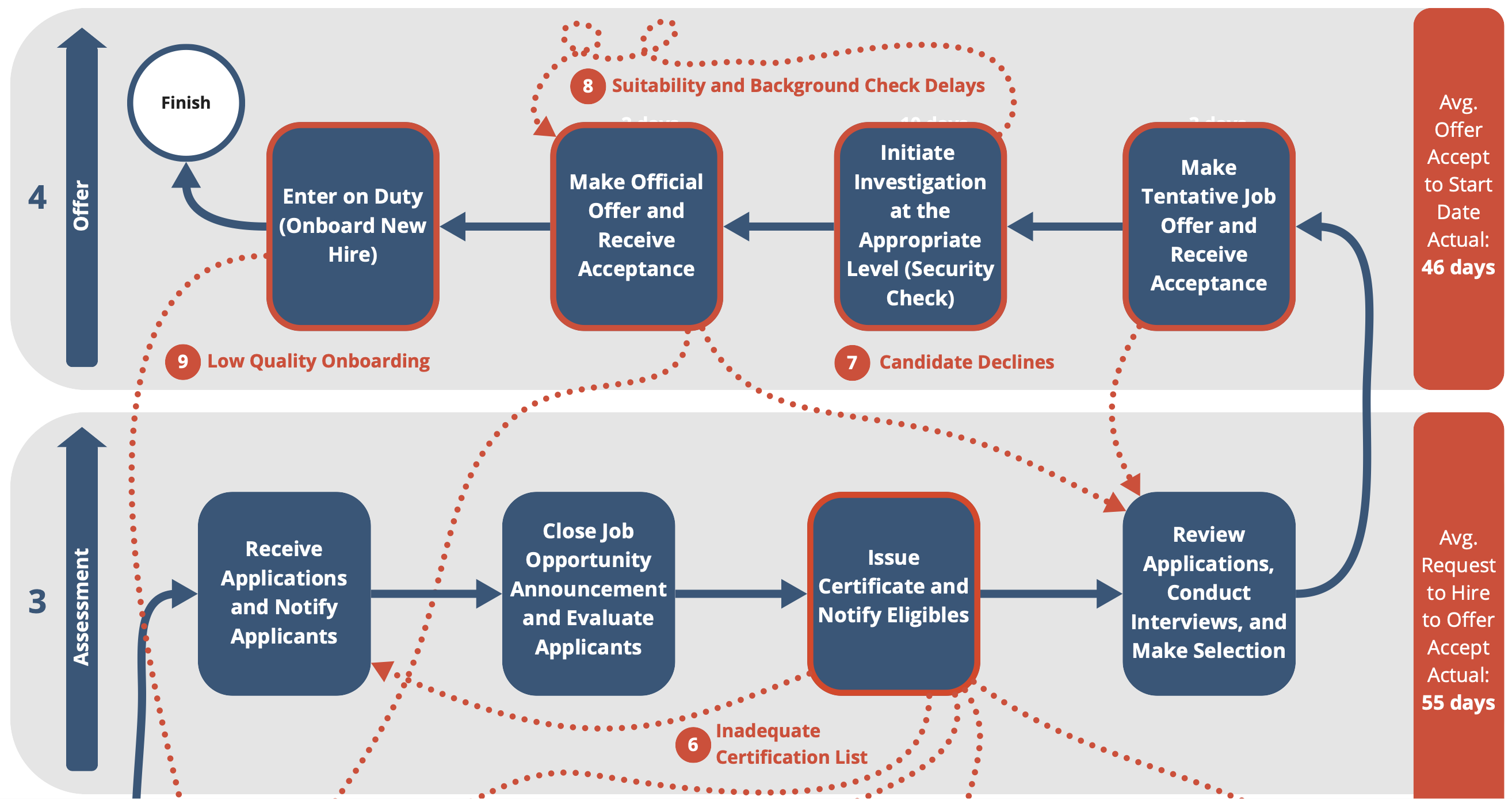

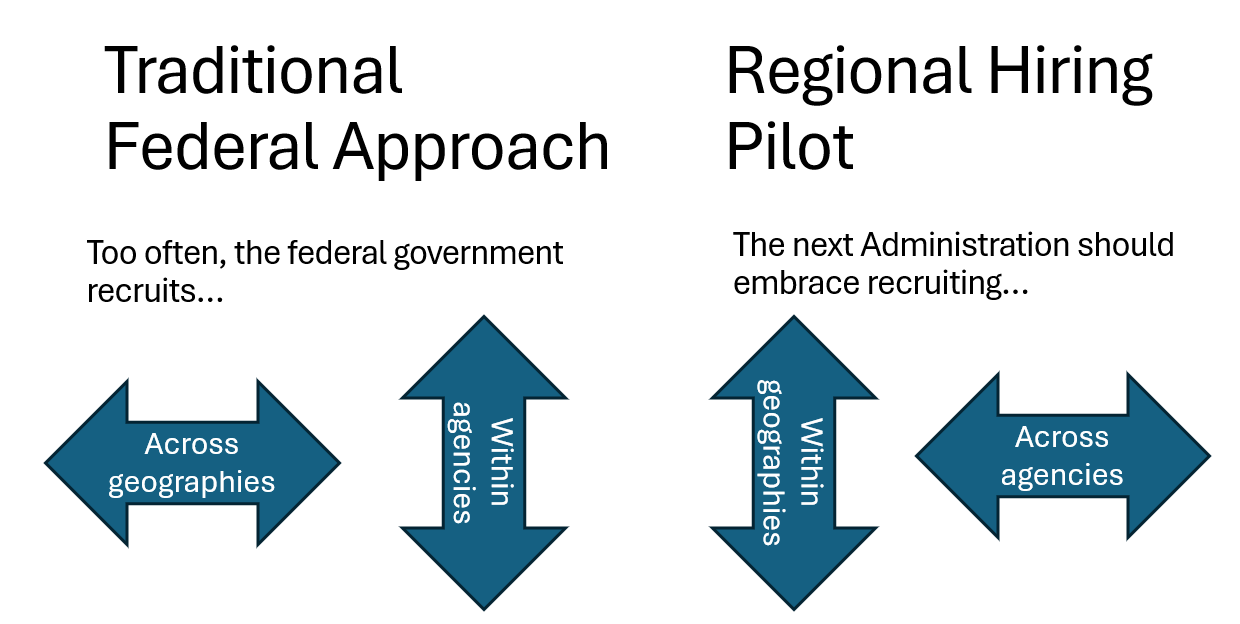

Breaking Down the New Memos on Federal Hiring

On May 29, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) published two memoranda that could substantially reshape federal hiring. The first–“Merit Hiring Plan”–issued with the White House Domestic Policy Council—implements Executive Order 14170. The second provides guidance on “Hiring and Talent Development for the Senior Executive Service”. Spanning 53 pages, the documents are written in dense HR jargon that can overwhelm even seasoned practitioners. To clarify their meaning and impact, the Niskanen Center and the Federation of American Scientists have teamed up to translate both memos for journalists, researchers, and the general public.

The Memos Generally: Lots To Like, Dangerous Partisanship, & A Long Road Ahead

The memos, at their core, attempt to address well-documented and long-existing challenges: federal hiring is too sluggish, procedural, and opaque. Both of our organizations have long argued for the need to move faster, hire better, and hold poor performing employees accountable while still adhering to the merit system principles. A high-performing, agile, and engaged federal workforce is essential if Americans are to trust if Americans are to trust that laws passed by Congress will be executed quickly, competently and efficiently.

These memos are the latest in a long line of efforts by Presidents of both parties to bring common sense to federal hiring and performance – speed up the hiring process, focus on the skills to do the job, evaluate those skills objectively, and share resources across agencies to economize on effort and investment. These memos push that agenda further than earlier efforts, delivering several long‑sought wins such as streamlined applications and résumés more in line with private‑sector norms.

They also venture further than any recent initiative in politicizing the civil service. Mandatory training and essay questions tied to the current Administration’s executive orders—and explicit political sign‑off on certain hiring actions—risk blurring the firewall between career professionals and partisan appointees. We have discussed the dangers associated with this type of partisan drift in other places, including in response to the recent OPM rulemaking on “Schedule Policy/Career”.

Implementing even the non-controversial portions will be daunting. Reforming the federal government–the largest employer in the country–requires sustained, years-long effort from OPM and OMB.

The memos themselves are only the starting gun. Notably absent is a realistic plan to resource this work: for example, OPM has fired or lost nearly all of its enterprise data analytics team, limiting its ability to supply the metrics needed for oversight and accountability. Additionally, the inclusion of extremely ideological and partisan goals politicizes the entire agenda and risks overshadowing the rest of the positive reform agenda, threatening its ability to succeed anywhere.

In evaluating these documents, we have to weigh each part of the Administration’s strategy separately and objectively – there is a lot to like in these documents, there are things that are deeply troubling, and there are things that desperately need leadership attention in implementation.

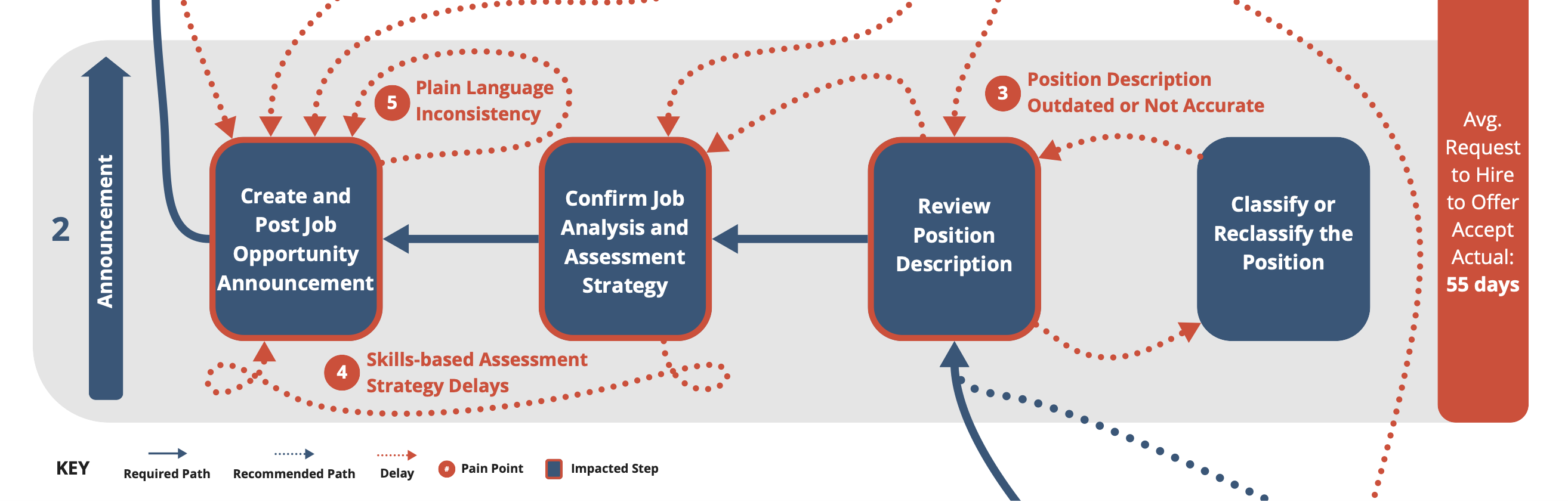

What We Like: Skills-Based Hiring, Resume Reform, Assessments, Sharing Across Agencies

The bulk of both memos represents a bold next step in long‑running federal hiring reforms—initiatives that agencies have piloted for years but often struggled to scale. We commend OPM for learning from past efforts and, in several critical areas, pushing further than any of its predecessors by:

- Recognizing the role of recruiting and sourcing talent – The plan highlights the importance of active recruiting in the hiring process.Agencies have long relied on USAJobs alone as a crutch, hoping the right kinds of talent will be scouring the job board every day and happen upon job postings – this works okay for some roles that are highly-specialized to government, but particularly as agencies have need for emerging talent it they cannot assume critical talent pools are even aware that the federal government wants to hire them.

- Focusing on skills and evaluating for those skills – The memo limits the use of self-assessments to minimum qualifications only and requires agencies to use some form of technical or alternative assessment for all postings, implementing 2024’s bipartisan Chance to Compete Act. This is a critical move forward from the reliance on applicant’s self-assessment,a status quo that disadvantages honesty and self-awareness.

- Implementing ‘Rule of Many’ ranking procedures – OPM will finalize its proposed ‘Rule of Many’ regulation from the last Administration, which empowers agencies to choose the various ways to “cut off” applicants after they are assessed. Finalizing ‘Rule of Many’ will enable agencies to set clear, objective criteria for which applicants it will consider based on test scores (e.g., considering the top 10% of scorers), a numerical approach (e.g., considering the top 50 applicants), and other mechanisms (e.g., clear pass/fail standards) that give hiring managers and HR specialists the flexibility they need to tailor hiring procedures to specific needs.

- Sharing resources and certifications of eligibles across agencies – This expands requirements for agencies to share candidates, position descriptions, and talent pools across agencies, including conducting pooled hiring actions where one candidate can apply once to many similar jobs across government. It builds on recent tremendous success agencies have with recruiting high-quality applicants across government through shared hiring actions, which enables agencies to surge talent in a specific field and advertise as one enterprise to potential applicants.

- Reducing size of referral resumes to two pages – OPM is finally attempting to move away from a “federal resume” format that needlessly burdens members of the public with overly-specific requirements. Previously, applicants that didn’t know to include things like the “average number of hours worked per week” or their complete salary history were unknowingly disqualifying themselves from federal employment and even those that knew better had to maintain two separate resumes, making it harder to jump between sectors.

- Simplifying Senior Executive applications – Applicants for Senior Executive Service roles will no longer be required to write multiple pages of essays describing their experience – a process so unique it has spawned a cottage industry of professional writers – and will be evaluated via resumes and structured interviews like their peers across the economy. This builds on a long history of successful pilots of new selection procedures focusing on resumes and structured interviews rather than the traditional essays.

- Removing unnecessary degree requirements – While efforts have been underway since the first Trump Administration to remove unnecessary degree requirements. The new memos solidify that trajectory, embracing a skills‑first hiring model that prizes demonstrated ability over paper credentials—a trend mirrored in state governments and the private sector. Yet dropping degree rules is only half the battle. To truly broaden the talent pool, agencies must replace résumé shortcuts (like “years of experience”) with rigorous, job‑relevant assessments that let candidates prove what they can actually do.

- Focusing on speed and responsiveness – The memo doesn’t ignore the aspect of the applicant experience that differs most from the private sector: speed and responsiveness, setting a government-wide target of 80 days for hiring actions and requiring timely updates to applicants on their status. This builds on years of work to wrestle down timelines for security clearances and recognizes that one of the biggest reasons the federal government loses amazing applicants is the length of the process, not the pay.

Finally, the memos contain a compendium of useful resources in Appendices that agencies that can use to improve their approach to hiring.

Potential Red Flags: Politicization, Red Tape, & Extra, Unfunded Mandates

While OPM is advancing important nonpartisan reforms, we are concerned that several explicitly ideological provisions could erode the civil service’s neutrality and jeopardize the very hiring‑efficiency agenda OPM seeks to champion:

- Requiring essay questions on political views–Despite reducing applicant burden in other areas, OPM also introduces a requirement for all applicants for jobs above GS-05 (98%+ of jobs) to draft responses to free-response essay questions that describe their views on the present administration, including identifying which of the current president’s Executive Orders are “significant” to them. At best, this is an additional requirement that will be irrelevant for most jobs – there shouldn’t be any impact of EOs on a seasonal wildland firefighter’s strategy for fighting fires, for instance. More realistically, this constitutes a partisan loyalty test for federal employees to evaluate their views on the current President. Federal employees swear their allegiance to the Constitution, not the current President and there are legitimate open questions about the constitutionality of many Executive Orders.

- Introducing extra layers of political approval in the hiring process–While the memo emphasizes time to hire, it also emphasizes that “agency leadership” must either personally approve or designate an official to approve all positions before they are posted and all selections prior to extension of an offer. It also requires that they do an “executive interview” with candidates and opens the door to obvious partisan abuse of the merit hiring process when paired with the free response essay questions. Even without that risk, however, this requirement adds tremendous amounts of friction into a process that is already too full of approvals and pulls the decision-making authority in the wrong direction: to leadership instead of to the line management that knows the needs of a given program best. We are already seeing the problems with this approach play out with a similar requirement for agency leadership to personally approve payments or contracts, leading to extreme slowdowns. Additionally, just as with OPM’s recent rulemaking on Schedule Policy/Career, the opportunity for abuse is extremely obvious: highly partisan agency leaders may see it as their right to disapprove of candidates for purely political reasons–like, for example, donations to opposing candidates.

- Prioritizes political training for the SES corps–While the Administration has closed down training programs like the Federal Executive Institute that were designed to train new generations of federal leaders, it is also adding ideological training to the SES that lacks a clear purpose or evidence that it will improve governing outcomes. Requiring Senior Executives to watch an “80-hour video-based program that provides training regarding President Trump’s Executive Orders” is both offensive to the principle of a nonpartisan civil service and a waste of time for the busiest, most senior leaders across the entire enterprise. While America’s most productive tech companies are trying to reduce the meeting load to free staff to get things done, torching 4% of our senior executives’ working years for ideological training is the opposite of efficient.

- No mention of resources to carry out these changes – As with past legislation, EOs, and memos requiring skills-based talent practices, no apparent financial or other resources come with these memos. This has hampered adoption for more than a decade. The Talent Teams at OPM and the agencies, the communications and education support, the changes to OPM and agency systems all need people, money, and IT support. The lack of committed resources will delay, and perhaps scuttle, implementation. We know this because it has happened before. In the Clinton Administration, for example, a major push to de-proceduralize federal hiring fell down because they underresourced agency HR offices to stick the landing. This will happen again on skills-based hiring without commensurate investment, a problem discussed at length in a recent paper from the Niskanen Center.

What’s Missing: A Scalable Implementation Strategy

Executing these reforms will be no small feat, and the toughest tasks are also the most crucial: getting good technical assessments in the hands of managers, conducting strategic workforce planning, changing the culture around hiring to empower managers and not HR, and letting line managers be managers. OPM’s memos are light on details about how they intend to resource and manage implementation, an omission that they have plenty of time to correct but one that needs some serious consideration if they are going to be successful:

- Changing entrenched oversight, HR, and hiring manager policies, practices, and culture – OPM and the agencies will need to focus on how to move decades-learned compliance and risk aversion behaviors embedded in the current hiring and performance management practices into a skills-based future. The change management and consistent leadership required here is a substantial undertaking. Because OPM has conditioned the federal HR profession to be incredibly risk-averse, it won’t immediately embrace these new mandates without coaching, training, and professional development. To facilitate this, OPM should re-submit its uncontroversial legislative proposal from last year to help professionalize and develop the federal HR workforce, and Congress should expeditiously pass it.

- Hiring is just one piece of the effective federal employee puzzle – Though the SES Memo addresses some aspects of performance management, the focus on hiring diminishes other parts of the management system that impact effectiveness and performance. Onboarding, the early job experience, consistent feedback, professional development, challenging assignments, and career paths all help to ensure employees are helping meet agency missions. Implementation needs to take the whole system into account if OPM and the agencies are going to impact effectiveness and accountability.

- An all-of-the-above approach for getting assessments into the hands of agencies – The memo focuses on USAHire but, as we’ve discussed, there are many third-party assessment vendors that offer validated assessments and tools to help lower the unit and marginal cost of using objective assessments. Emerging companies offer things like AI-proctored video interviews that could quickly surface the most promising candidates and are already in use by the private sector for high-volume roles. At the federal level, parts of the Department of Homeland Security and other agencies have already experimented with some of these platforms. We want to see OPM think bigger about how to quickly bring assessments online and recognize that the private sector can play a role in accelerating this transformation.

- Focus on the candidate experience – Job candidates – users of the federal hiring system – complain that the experience of applying for a federal job is neither easy nor seamless, as it can be in the private sector. While the memos make some progress in reducing the burden on candidates (e.g., reducing resume and SES application requirements), the system is still rife with bureaucratic bloat. High-performing candidates have many options; they will go elsewhere if we do not reduce the friction.

- Public accountability & data – According to the hiring plan memo, agencies need to develop a data-driven plan for implementation and report frequently to OPM and OMB on their progress. With the practical dissolution of OPM’s human capital data team and a years-long problem with lagging human capital data releases via Fedscope, OPM should commit to releasing data publicly on their progress: how many people are hired, where they are hired, how many apply, how many pass technical assessments, etc. that will hold agencies accountable for getting this work done, give Congress the insight it needs to trust OPM, and provide the public with a window into progress.

- A plan to staff for success – In the best of times, OPM struggles with capacity for human capital policy work, and it will need every federal human capital expert it can get to pull off implementation of these memos. However, at the same time, OMB’s FY2026 budget proposal outlines a significant reduction in total headcount for OPM that locks in a 25%+ reduction in headcount across all parts of the agency, from policy to direct support for agencies. Given the technical complexity involved in many of these efforts–delivering validated assessments, for example, will likely require bringing in new expertise from outside government–OPM will need a plan to staff itself for success that is missing in these memos today.

In urgent circumstances, agencies have experimented with some of these practices and policies (e.g., cybersecurity hiring and intelligence community hiring, infrastructure and energy development). However, action on skills-based talent practices is far from pervasive. Together with outside experts, we continue to map the obstacles that keep skills‑first hiring from taking root: limited resources, hesitant leadership, and a pervasive fear of downside risk. Many of the opportunities and chokepoints highlighted in the memos came from this work, and we will keep collaborating with all stakeholders to craft practical fixes.

Most of the reforms in these memoranda set federal hiring on a promising trajectory, but their impact will hinge on disciplined execution. Some of them are deeply troubling attacks on the basis of the merit system. We will track OPM’s progress closely—amplifying best practices and calling out any drift from merit‑based, nonpartisan norms. These challenges are not new, yet they have become increasingly existential to building a government that works; OPM must keep that urgency front and center as implementation moves forward.

Reforming the Federal Advisory Committee Landscape for Improved Evidence-based Decision Making and Increasing Public Trust

Federal Advisory Committees (FACs) are the single point of entry for the American public to provide consensus-based advice and recommendations to the federal government. These Advisory Committees are composed of experts from various fields who serve as Special Government Employees (SGEs), attending committee meetings, writing reports, and voting on potential government actions.

Advisory Committees are needed for the federal decision-making process because they provide additional expertise and in-depth knowledge for the Agency on complex topics, aid the government in gathering information from the public, and allow the public the opportunity to participate in meetings about the Agency’s activities. As currently organized, FACs are not equipped to provide the best evidence-based advice. This is because FACs do not meet transparency requirements set forth by GAO: making pertinent decisions during public meetings, reporting inaccurate cost data, providing official meeting documents publicly available online, and more. FACs have also experienced difficulty with recruiting and retaining top talent to assist with decision making. For these reasons, it is critical that FACs are reformed and equipped with the necessary tools to continue providing the government with the best evidence-based advice. Specifically, advice as it relates to issues such as 1) decreasing the burden of hiring special government employees 2) simplifying the financial disclosure process 3) increasing understanding of reporting requirements and conflict of interest processes 4) expanding training for Advisory Committee members 5) broadening the roles of Committee chairs and designated federal officials 6) increasing public awareness of Advisory Committee roles 7) engaging the public outside of official meetings 8) standardizing representation from Committee representatives 9) ensuring that Advisory Committees are meeting per their charters and 10) bolstering Agency budgets for critical Advisory Committee issues.

Challenge and Opportunity

Protecting the health and safety of the American public and ensuring that the public has the opportunity to participate in the federal decision-making process is crucial. We must evaluate the operations and activities of federal agencies that require the government to solicit evidence-based advice and feedback from various experts through the use of federal Advisory Committees (FACs). These Committees are instrumental in facilitating transparent and collaborative deliberation between the federal government, the advisory body, and the American public and cannot be done through the use of any other mechanism. Advisory Committee recommendations are integral to strengthening public trust and reinforcing the credibility of federal agencies. Nonetheless, public trust in government has been waning and efforts should be made to increase public trust. Public trust is known as the pillar of democracy and fosters trust between parties, particularly when one party is external to the federal government. Therefore, the use of Advisory Committees, when appropriately used, can assist with increasing public trust and ensuring compliance with the law.

There have also been many success stories demonstrating the benefits of Advisory Committees. When Advisory Committees are appropriately staffed based on their charge, they can decrease the workload of federal employees, assist with developing policies for some of our most challenging issues, involve the public in the decision-making process, and more. However, the state of Advisory Committees and the need for reform have been under question, and even more so as we transition to a new administration. Advisory Committees have contributed to the improvement in the quality of life for some Americans through scientific advice, as well as the monitoring of cybersecurity. For example, an FDA Advisory Committee reviewed data and saw promising results for the treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD) which has been a debilitating disease with limited treatment for years. The Committee voted in favor of gene therapy drugs Casgevy and Lyfgenia which were the first to be approved by the FDA for SCD.

Under the first Trump administration, Executive Order (EO) 13875 resulted in a significant decrease in the number of federal advisory meetings. This limited agencies’ ability to convene external advisors. Federal science advisory committees met less during this administration than any prior administration, met less than what was required from their charter, disbanded long standing Advisory Committees, and scientists receiving agency grants were barred from serving on Advisory Committees. Federal Advisory Committee membership also decreased by 14%, demonstrating the issue of recruiting and retaining top talent. The disbandment of Advisory Committees, exclusion of key scientific external experts from Advisory Committees, and burdensome procedures can potentially trigger severe consequences that affect the health and safety of Americans.

Going into a second Trump administration, it is imperative that Advisory Committees have the opportunity to assist federal agencies with the evidence-based advice needed to make critical decisions that affect the American public. The suggested reforms that follow can work to improve the overall operations of Advisory Committees while still providing the government with necessary evidence-based advice. With successful implementation of the following recommendations, the federal government will be able to reduce administrative burden on staff through the recruitment, onboarding, and conflict of interest processes.

The U.S. Open Government Initiative encourages the promotion and participation of public and community engagement in governmental affairs. However, individual Agencies can and should do more to engage the public. This policy memo identifies several areas of potential reform for Advisory Committees and aims to provide recommendations for improving the overall process without compromising Agency or Advisory Committee membership integrity.

Plan of Action

The proposed plan of action identifies several policy recommendations to reform the federal Advisory Committee (Advisory Committee) process, improving both operations and efficiency. Successful implementation of these policies will 1) improve the Advisory Committee member experience, 2) increase transparency in federal government decision-making, and 3) bolster trust between the federal government, its Advisory Committees, and the public.

Streamline Joining Advisory Committees

Recommendation 1. Decrease the burden of hiring special government employees in an effort to (1) reduce the administrative burden for the Agency and (2) encourage Advisory Committee members, who are also known as special government employees (SGEs), to continue providing the best evidence-based advice to the federal government through reduced onerous procedures

The Ethics in Government Act of 1978 and Executive Order 12674 lists OGE-450 reporting as the required public financial disclosure for all executive branch and special government employees. This Act provides the Office of Government Ethics (OGE) the authority to implement and regulate a financial disclosure system for executive branch and special government employees whose duties have “heightened risk of potential or actual conflicts of interest”. Nonetheless, the reporting process becomes onerous when Advisory Committee members have to complete the OGE-450 before every meeting even if their information remains unchanged. This presents a challenge for Advisory Committee members who wish to continue serving, but are burdened by time constraints. The process also burdens federal staff who manage the financial disclosure system.

Policy Pathway 1. Increase funding for enhanced federal staffing capacity to undertake excessive administrative duties for financial reporting.

Policy Pathway 2. All federal agencies that deploy Advisory Committees can conduct a review of the current OGC-450 process, budget support for this process, and work to develop an electronic process that will eliminate the use of forms and allow participants to select dropdown options indicating if their financial interests have changed.

Recommendation 2. Create and use public platforms such as OpenPayments by CMS to (1) aid in simplifying the financial disclosure reporting process and (2) increase transparency for disclosure procedures

Federal agencies should create a financial disclosure platform that streamlines the process and allows Advisory Committee members to submit their disclosures and easily make updates. This system should also be created to monitor and compare financial conflicts. In addition, agencies that utilize the expertise of Advisory Committees for drugs and devices should identify additional ways in which they can promote financial transparency. These agencies can use Open Payments, a system operated by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), to “promote a more financially transparent and accountable healthcare system”. The Open Payments system makes payments from medical and drug device companies to individuals, healthcare providers, and teaching hospitals accessible to the public. If for any reason financial disclosure forms are called into question, the Open Payments platform can act as a check and balance in identifying any potential financial interests of Advisory Committee members. Further steps that can be taken to simplify the financial disclosure process would be to utilize conflict of interest software such as Ethico which is a comprehensive tool that allows for customizable disclosure forms, disclosure analytics for comparisons, and process automation.

Policy Pathway. The Office of Government Ethics should require all federal agencies that operate Advisory Committees to develop their own financial disclosure system and include a second step in the financial disclosure reporting process as due diligence, which includes reviewing the Open Payments by CMS system for potential financial conflicts or deploying conflict of interest monitoring software to streamline the process.

Streamline Participation in an Advisory Committee

Recommendation 3. Increase understanding of annual reporting requirements for conflict of interest (COI)

Agencies should develop guidance that explicitly states the roles of Ethics Officers, also known as Designated Agency Ethics Officials (DAEO), within the federal government. Understanding the roles and responsibilities of Advisory Committee members and the public will help reduce the spread of misinformation regarding the purpose of Advisory Committees. In addition, agencies should be encouraged by the Office of Government Ethics to develop guidance that indicates the criteria for inclusion or exclusion of participation in Committee meetings. Currently, there is no public guidance that states what types of conflicts of interests are granted waivers for participation. Full disclosure of selection and approval criteria will improve transparency with the public and draw clear delineations between how Agencies determine who is eligible to participate.

Policy Pathway. Develop conflict of interest (COI) and financial disclosure guidance specifically for SGEs that states under what circumstances SGEs are allowed to receive waivers for participation in Advisory Committee meetings.

Recommendation 4. Expand training for Advisory Committee members to include (1) ethics and (2) criteria for making good recommendations to policymakers

Training should be expanded for all federal Advisory Committee members to include ethics training which details the role of Designated Agency Ethics Officials, rules and regulations for financial interest disclosures, and criteria for making evidence-based recommendations to policymakers. Training for incoming Advisory Committee members ensures that all members have the same knowledge base and can effectively contribute to the evidence-based recommendations process.

Policy Pathway. Agencies should collaborate with the OGE and Agency Heads to develop comprehensive training programs for all incoming Advisory Committee members to ensure an understanding of ethics as contributing members, best practices for providing evidence-based recommendations, and other pertinent areas that are deemed essential to the Advisory Committee process.

Leverage Advisory Committee Membership

Recommendation 5. Uplifting roles of the Committee Chairs and Designated Federal Officials

Expanding the roles of Committee Chairs and Designated Federal Officers (DFOs) may assist federal Agencies with recruiting and retaining top talent and maximizing the Committee’s ability to stay abreast of critical public concerns. Considering the fact that the General Services Administration has to be consulted for the formation of new Committees, renewal, or alteration of Committees, they can be instrumental in this change.

Policy Pathway. The General Services Administration (GSA) should encourage federal Agencies to collaborate with Committee Chairs and DFOs to recruit permanent and ad hoc Committee members who may have broad network reach and community ties that will bolster trust amongst Committees and the public.

Recommendation 6. Clarify intended roles for Advisory Committee members and the public

There are misconceptions among the public and Advisory Committee members about Advisory Committee roles and responsibilities. There is also ambiguity regarding the types of Advisory Committee roles such as ad hoc members, consulting, providing feedback for policies, or making recommendations.

Policy Pathway. GSA should encourage federal Agencies to develop guidance that delineates the differences between permanent and temporary Advisory Committee members, as well as their roles and responsibilities depending on if they’re providing feedback for policies or providing recommendations for policy decision-making.

Recommendation 7. Utilize and engage expertise and the public outside of public meetings

In an effort to continue receiving the best evidence-based advice, federal Agencies should develop alternate ways to receive advice outside of public Committee meetings. Allowing additional opportunities for engagement and feedback from Committee experts or the public will allow Agencies to expand their knowledge base and gather information from communities who their decisions will affect.

Policy Pathway. The General Services Administration should encourage federal Agencies to create opportunities outside of scheduled Advisory Committee meetings to engage Committee members and the public on areas of concern and interest as one form of engagement.

Recommendation 8. Standardize representation from Committee representatives (i.e., industry), as well as representation limits

The Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) does not specify the types of expertise that should be represented on all federal Advisory Committees, but allows for many types of expertise. Incorporating various sets of expertise that are representative of the American public will ensure the government is receiving the most accurate, innovative, and evidence-based recommendations for issues and products that affect Americans.

Policy Pathway. Congress should include standardized language in the FACA that states all federal Advisory Committees should include various sets of expertise depending on their charge. This change should then be enforced by the GSA.

Support a Vibrant and Functioning Advisory Committee System

Recommendation 9. Decrease the burden to creating an Advisory Committee and make sure Advisory Committees are meeting per their charters

The process to establish an Advisory Committee should be simplified in an effort to curtail the amount of onerous processes that lead to a delay in the government receiving evidence based advice.

Advisory Committee charters state the purpose of Advisory Committees, their duties, and all aspirational aspects. These charters are developed by agency staff or DFOs with consultation from their agency Committee Management Office. Charters are needed to forge the path for all FACs.

Policy Pathway. Designated Federal Officers (DFOs) within federal agencies should work with their Agency head to review and modify steps to establishing FACs. Eliminate the requirement for FACs to require consultation and/or approval from GSA for the formation, renewal, or alteration of Advisory Committees.

Recommendation 10. Bolster agency budgets to support FACs on critical issues where regular engagement and trust building with the public is essential for good policy

Federal Advisory Committees are an essential component to receive evidence-based recommendations that will help guide decisions at all stages of the policy process. These Advisory Committees are oftentimes the single entry point external experts and the public have to comment and participate in the decision-making process. However, FACs take considerable resources to operate depending on the frequency of meetings, the number of Advisory Committee members, and supporting FDA staff. Without proper appropriations, they have a diminished ability to recruit and retain top talent for Advisory Committees. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that in 2019, approximately $373 million dollars was spent to operate a total of 960 federal Advisory Committees. Some Agencies have experienced a decrease in the number of Advisory Committee convenings. Individual Agency heads should conduct a budget review of average operating and projected costs and develop proposals for increased funding to submit to the Appropriations Committee.

Policy Pathway. Congress should consider increasing appropriations to support FACs so they can continue to enhance federal decision-making, improve public policy, boost public credibility, and Agency morale.

Conclusion

Advisory Committees are necessary to the federal evidence-based decision-making ecosystem. Enlisting the advice and recommendations of experts, while also including input from the American public, allows the government to continue making decisions that will truly benefit its constituents. Nonetheless, there are areas of FACs that can be improved to ensure it continues to be a participatory, evidence-based process. Additional funding is needed to compensate the appropriate Agency staff for Committee support, provide potential incentives for experts who are volunteering their time, and finance other expenditures.

With reform of Advisory Committees, the process for receiving evidence-based advice will be streamlined, allowing the government to receive this advice in a faster and less burdensome manner. Reform will be implemented by reducing the administrative burden for federal employees through the streamlining of recruitment, financial disclosure, and reporting processes.

Solutions for an Efficient and Effective Federal Permitting Workforce

The United States faces urgent challenges related to aging infrastructure, vulnerable energy systems, and economic competitiveness. Improving American competitiveness, security, and prosperity depends on private and public stakeholders’ ability to responsibly site, build, and deploy critical energy and infrastructure. Unfortunately, these projects face one common bottleneck: permitting.

Permits and authorizations are required for the use of land and other resources under a series of laws, such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. However, recent court rulings and the Trump Administration’s executive actions have brought uncertainty and promise major disruption to the status quo. The Executive Order (EO) on Unleashing American Energy mandates guidance to agencies on permitting processes be expedited and simplified within 30 days, requires agencies prioritize efficiency and certainty over any other objectives, and revokes the Council of Environmental Quality’s (CEQ) authority to issue binding NEPA regulations. While these changes aim to advance the speed, efficiency, and certainty of permitting, the impact will ultimately depend on implementation by the permitting workforce.

Unfortunately, the permitting workforce is unprepared to swiftly implement changes following shifts in environmental policy and regulations. Teams responsible for permitting have historically been understaffed, overworked, and unable to complete their project backlogs, while demands for permits have increased significantly in recent years. Building workforce capacity is critical for efficient and effective federal permitting.

Project Overview

Our team at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has spent 18 months studying and working to build government capacity for permitting talent. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provided resources to expand the federal permitting workforce, and we partnered with the Permitting Council, which serves as a central body to improve the transparency, predictability, and accountability of the federal environmental review and authorization process, to gain a cross-agency understanding of the hiring challenges experienced in permitting agencies and prioritize key challenges to address. Through two co-hosted webinars for hiring managers, HR specialists, HR leaders, and program leaders within permitting agencies, we shared tactical solutions to improve the hiring process.

We complemented this understanding with voices from agencies (i.e., hiring managers, HR specialists, HR teams, and leaders) by conducting interviews to identify new issues, best practices, and successful strategies for building talent capacity. With this understanding, we developed long-term solutions to build a sustainable, federal permitting workforce for the future. While many of our recommendations are focused on permitting talent specifically, our work naturally uncovered challenges within the broader federal talent ecosystem. As such, we’ve included recommendations to advance federal talent systems and improve federal hiring.

Problem

Building permitting talent capacity across the federal government is not an easy endeavor. There are many stakeholders involved across different agencies with varying levels of influence who need to play a role: the Permitting Council staff, the Permitting Council members-represented by Deputy Secretaries (Deputy Secretaries) of permitting agencies, the Chief Environmental Review and Permitting Officers (CERPOs) in each agency, the Office of Personnel and Management (OPM), the Chief Human Capital Officer (CHCO) in each permitting agency, agency HR teams, agency permitting teams, hiring managers, and HR specialists. Permitting teams and roles are widely dispersed across agencies, regions, states, and programs. The role each agency plays in permitting varies based on their mission and responsibilities, and there are many silos within the broader ecosystem. Few have a holistic view of permitting activities and the permitting workforce across the federal government.

With this complex network of actors, one challenge that arises is a lack of standardization and consistency in both roles and teams across agencies. If agencies are looking to fill specialized roles unique to one permitting need, it means that there will be less opportunity for collaboration and for building efficiencies across the ecosystem. The federal hiring process is challenging, and there are many known bottlenecks that cause delays. If agencies don’t leverage opportunities to work together, these bottlenecks will multiply, impacting staff who need to hire and especially permitting and/or HR teams who are understaffed, which is not uncommon. Additionally, building applicant pools to have access to highly qualified candidates is time consuming and not scalable without more consistency.

Tracking workforce metrics and hiring progress is critical to informing these talent decisions. Yet, the tools available today are insufficient for understanding and identifying gaps in the federal permitting workforce. The uncertainty of long-term, sustainable funding for permitting talent only adds more complexity into these talent decisions. While there are many challenges, we have identified solutions that stakeholders within this ecosystem can take to build the permitting workforce for the future.

There are six key recommendations for addressing permitting workforce capacity outlined in the table below. Each is described in detail with corresponding actions in the Solutions section that follows. Our recommendations are for the Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, and Congress.

Solutions

The six solutions described below include an explanation of the problem and key actions our signal stakeholders (Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, and Congress) can take to build permitting workforce capacity. The table in the appendix specifies the stakeholders responsible for each recommendation.

Enhance the Permitting Council’s Authority to Improve Permitting Processes and Workforce Collaboration

Permitting process, performance, and talent management cut across agencies and their bureaus—but their work is often disaggregated by agency and sub-agency, leading to inefficient and unnecessarily discrete practices. While the Permitting Council plays a critical coordinating role, it lacks the authority and accountability to direct and guide better permitting outcomes and staffing. There is no central authority for influencing and mandating permitting performance. Agency-level CERPOs vary widely in their authority, whereas the Permitting Council is uniquely positioned for this role. Choosing to overlook this entity will lead to another interagency workaround. Congress needs to give the Permitting Council staff greater authority to improve permitting processes and workforce collaboration.

- Enhance Permitting Council Authority for Improved Performance: Enhance provisions in FAST-41 and IRA by passing legislation that empowers the Permitting Council staff to create and enforce consistent performance criteria for permitting outcomes, permitting process metrics, permitting talent acquisition, talent management, and permitting teams KPIs.

- Enhance Permitting Council Authority for Interagency Coordination: Empower the Permitting Council staff to manage interagency coordination and collaboration for defining permitting best practices, establishing frameworks for permitting, and reinforcing those frameworks across agencies. Clarify the roles and responsibilities between Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, and the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ).

- Assign Responsibility for Tracking Changes and Providing Guidance for Permitting Practices: Assign the Permitting Council staff in coordination with OMB responsibility for tracking changes and providing guidance on permitting practices in response to recent and ongoing court rulings that change how permitting outcomes are determined (e.g., Loper Bright/Chevron Deference, CEQ policies, etc.).

- Provide Permitting Council staff with Consistent Funding: Either renew components of IRA and/or IIJA funding that enables the Council to invest in agency technologies, hiring, and workforce development, or provide consistent appropriations for this.

- Enhance CERPO Authority and Position CERPOs for Agency-Wide and Cross-Agency Permitting Actions: Expand CERPO authority beyond the FAST-41 Act to include all permitting work within their agency. Through legislation, policy, and agency-level reporting relationships (e.g., CERPO roles assigned to the Secretary’s office), provide CERPOs with clear authority and accountability for permitting performance.

Build Efficient Permitting Teams and Standardize Roles

In our research, we interviewed one program manager who restructured their team to drive efficiency and support continuous improvement. However, this is not common. Rather, there is a lack of standardization in roles engaged in permitting teams within and across agencies, which hinders collaboration and prevents efficiencies. This is likely driven by the different roles played by agencies in permitting processes. These variances are in opposition to shared certifications and standardized job descriptions, complicate workforce planning, hinder staff training and development, and impact report consistency. The Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OMB, and the CHCO Council should improve the performance and consistency of permitting processes by establishing standards in permitting team roles and configurations to support cross-agency collaboration and drive continuous improvements.

- Characterize Types of Permitting Processes: Permitting Council staff should work with Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, and Permitting Program Team leaders to categorize types of permitting processes based on project “footprint”, complexity, regulatory reach (i.e., regulations activated), populations affected and other criteria. Identify the range of team configurations in use for the categories of processes.

- Map Agency Permitting Roles: Permitting Council staff should map and clarify the roles played by each agency in permitting processes (e.g., sponsoring agency, contributing agency) to provide a foundation for understanding the types of teams employed to execute permitting processes.

- Research and Analyze Agency Permitting Staffing: Permitting Council staff should collaborate with OMB to conduct or refine a data call on permitting staffing. Analyze the data to compare the roles and team structures that exist between and across agencies. Conduct focus groups with cross agency teams to identify consistent talent needs, team functions, and opportunities for standardization.

- Develop Permitting Team Case Studies: Permitting Council staff should conduct research to develop a series of case studies that highlight efficient and high performing permitting team structures and processes.

- Develop Permitting Team Models: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop team models for different agency roles (i.e., sponsor, lead agency, coordinating agency) that focus on driving efficiencies through process improvements and technology, and develop guidelines for forming new permitting teams.

- Create Permitting Job Personas: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop personas to showcase the roles needed on each type of permitting team and roles, recognizing that some variance will always remain, and the type of hiring authority that should be used to acquire those roles (e.g., IPA for highly specialized needs). This should also include new roles focused on process improvements; technology and data acquisition, use, and development; and product management for efficiency, improved customer experience, and effectiveness.

- Define Standardized Permitting Roles and Job Analyses: With the support of Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should identify roles that can be standardized across agencies based on the personas, and collaborate with permitting agencies to develop standard job descriptions and job analyses.

- Develop Permitting Practice Guide: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop a primer on federal permitting practices that explains how to efficiently and effectively complete permitting activities.

- Place Organizational Strategy Fellows: Permitting Council staff should hire at least one fellow to their staff to lead this effort and coordinate/liaise between permitting teams at different agencies.

- Mandate Permitting Hiring Forecasts: Permitting Council staff should collaborate with the CHCO Council to mandate permitting hiring forecasts annually with quarterly updates.

- Revise Permitting Funding Requirements: Permitting Council staff should include requirements for the adoption of new team models and roles in the resources and coordination provided to permitting agencies to drive process efficiencies.

Improve Workforce Strategy, Planning, and Decisions through Quality Workforce Metrics

Agency permitting leaders and those working across agencies do not have the information to make informed workforce decisions on hiring, deployment, or workload sharing. Attempts to access accurate permitting workforce data highlighted inefficient methods for collecting, tracking, and reporting on workforce metrics across agencies. This results in a lack of transparency into the permitting workforce, data quality issues, and an opaque hiring progress. With these unknowns, it becomes difficult to prioritize agency needs and support. Permitting provided a purview into this challenge, but it is not unique to the permitting domain. OPM, OMB, the CHCO Council, and Permitting Council staff need to accurately gather and report on hiring metrics for talent surges and workforce metrics by domain.

- Establish Permitting Workforce Data Standards: OPM should create minimum data standards for hiring and expand existing data standards to include permitting roles in employee records, starting with the Request for Personnel Action that initiates hiring (SF52). Permitting Council staff should be consulted in defining standards for the permitting workforce.

- Mandate Agency Data Sharing: OPM and OMB should require agencies share personnel action data; this should be done automatically through APIs or a weekly data pull between existing HR systems. To enable this sharing, agencies must centralize and standardize their personnel action data from their components.

- Create Workforce Dashboards: OPM should create domain-specific workforce dashboards based on most recent agency data and make it accessible to the relevant agencies. This should be done for the permitting workforce.

- Mandate Permitting Hiring Forecasts: The CHCO Council should mandate permitting hiring forecasts annually with quarterly updates. This data should feed into existing agency talent management/acquisition systems to track workforce needs and support adaptive decision making.

Invest in Professional Development and Early Career Pathways

There are few early career pathways and development opportunities for personnel who engage in permitting activities. This limits agencies’ workforce capacity and extends learning curves for new staff. This results in limited applicant pools for hiring, understaffed permitting teams, and limited access to expertise. More recently, many of the roles permitting teams hired for were higher level GS positions. With a greater focus on early career pathways and development, future openings could be filled with more internal personnel. In our research, one hiring manager shared how they established an apprenticeship program for early career staff, which has led 12 interns to continue into permanent federal service positions. The Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, and CERPOs should create more development opportunities and early career pathways for civil servants.

- Invest in Training to Upskill and Reskill Staff: The Permitting Council staff should continue investing in training and development programs (i.e., Permitting University) to upskill and reskill federal employees in critical permitting skills and knowledge. Leveraging the knowledge gained through creating standard permitting team roles and collaborating with permitting leaders, the Permitting Council staff should define critical knowledge and skills needed for permitting and offer additional training to support existing staff in building their expertise and new employees in shortening their learning curve.

- Allocate Permitting Staff Across Offices and Regions: CERPOs and Deputy Secretaries should implement a flexible staffing model to reallocate staff to projects in different offices and regions to build their experience and skill set in key areas, where permitting work is anticipated to grow. This can also help alleviate capacity constraints on projects or in specific locations.

- Invest in Flexible Hiring Opportunities: CERPOs and Deputy Secretaries should invest in a range of flexible hiring options, including 10-year STEM term appointments and other temporary positions, to provide staffing flexibility depending on budget and program needs. Additionally, OPM needs to redefine STEM to include technology positions that do not require a degree (e.g., Environmental Protection Specialists).

- Establish a Permitting Apprenticeship: The Permitting Council staff should establish a 1-year apprenticeship program for early career professionals to gain on-the-job experience and learn about permitting activities. The apprenticeship should focus on common roles shared across agencies and place talent into agency positions. A rotational component could benefit participants in experiencing different types of work.

Improve and Invest in Pooled Hiring for Common Positions

Outdated and inaccurate job descriptions slow down and delay the hiring process. Further delays are often caused by the use of non-skills-based assessments, often self-assessments, which reduce the quality of the certificate list, or the list of eligible candidates given to the hiring manager. HR leaders confront barriers in the authority they have to share job announcements, position descriptions (PDs), classification determinations, and certificate lists of eligible candidates (Certs). Coupled with the above ideas on creating consistency in permitting teams and roles and better workforce data, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, and CERPOs should improve and make joint announcements, shared position descriptions, assessments, and certificates of eligibles for common positions a standard practice.

- Provide CHCOs the Delegated Authority to Share Announcements, PDs, Assessments, and Certs: OPM and OMB should lower the barriers for agencies to share key hiring elements and jointly act on common permitting positions by delegating the authority for CHCOs to work together within and across their agencies, including with the Permitting Council staff.

- Revise Shared Certificate Policies: OPM and OMB should revise shared certificate policies to allow agencies to share certificates regardless of locations designated in the original announcement and the type of hire (temporary or permanent). They should require skills-based assessments in all pooled hiring. Additionally, OPM should streamline and clarify the process for sharing certificates across agencies. Agencies need to understand and agree to the process for selecting candidates off the certificate list.

- Create a Government-wide Platform for Permitting Hiring Collaboration: OPM should create a platform to gather and disseminate permitting job announcements, PDs, classification determinations, job/competency evaluations, and cert. lists to support the development of consistent permitting teams and roles.