Not Accessible: Federal Policies Unnecessarily Complicate Funding to Support Differently Abled Researchers. We Can Change That.

Persons with disabilities (PWDs) are considered the largest minority in the nation and in the world. There are existing policies and procedures from agencies, directorates, or funding programs that provide support for Accessibility and Accommodations (A&A) in federally funded research efforts. Unfortunately, these policies and procedures all have different requirements, processes, deadlines, and restrictions. This lack of standardization can make it difficult to acquire the necessary support for PWDs by placing the onus on them or their Principal Investigators (PIs) to navigate complex and unique application processes for the same types of support.

This memo proposes the development of a standardized, streamlined, rolling, post-award support mechanism to provide access and accommodations for PWDs as they conduct research and disseminate their work through conferences and convenings. The best case scenario is one wherein a PI or their institution can simply submit the identifying information for the award that has been made and then make a direct request for the support needed for a given PWD to work on the project. In a multi-year award such a request should be possible at any time within the award period.

This could be implemented by a single, streamlined policy adopted by all agencies with the process handled internally. Or, by a new process across agencies under Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) or Office of Management and Budget (OMB) that handles requests for accessibility and accommodations at federally funded research sites and at federally funded convenings. An alternative to a single streamlined policy across these agencies might be a new section in the uniform guidance for federal funding agencies, also known as 2 CFR 200.

This memo focuses on Federal Open Science funding programs to illustrate the challenges in getting A&A funding requests supported. The authors have taken an informal look at agencies outside of science and technology funding. We found similar challenges across federal grantmaking in the Arts and Humanities, Social Services, and Foreign Relations and Aid entities. Similar issues likely exist in private philanthropy as well.

Challenge and Opportunity

Deaf/hard-of-hearing (DHH), Blind/low-vision (BLV), and other differently abled academicians, senior personnel, students, and post-doctoral fellows engaged in federally funded research face challenges in acquiring accommodations for accessibility. These include, but are not limited to:

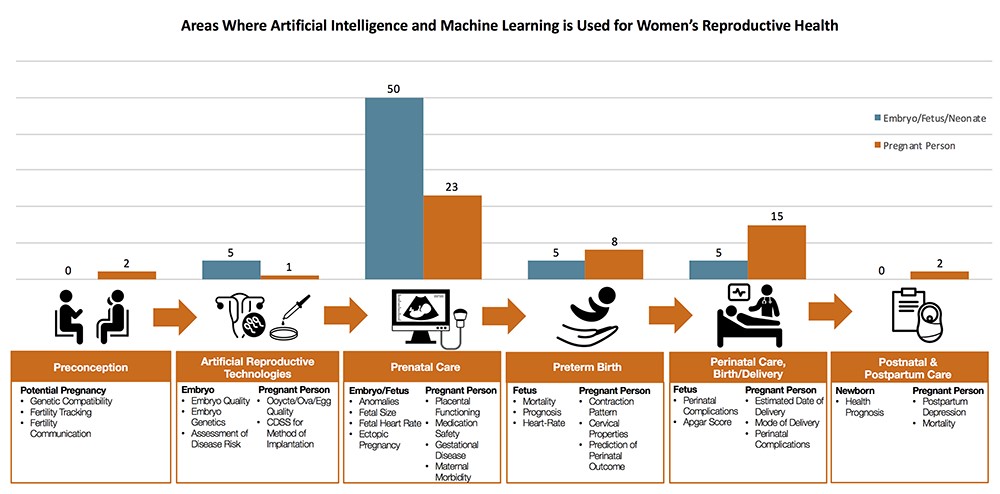

- Human-provided ASL-English interpreting and interview transcription services for the DHH and non-DHH participants. While there are some applications of artificial intelligence (AI) that show promise on the transcription side, there’s a long way to go on ASL interpretation in an AI provided model versus the use of human interpreters.

- Visual and Pro-tactile interpreting/descriptive services for the BLV participants

- Adaptive lab equipment and computing peripherals

- Accessibility support or remediation for physical sites

Having these services available is crucial for promoting an inclusive research environment on a larger scale.

Moving to a common, post-award process:

- Allows the PI and the reviewers more time and space to focus on the core research efforts being described in the initial proposal

- Removes any chance of the proposal funding being taken out of consideration due to higher costs in comparison to similar proposals in the pool

- Creates a standard, replicable pathway for seeking accommodations once the overall proposal has been funded. This is especially true if the support comes from a single process across all federal funding programs rather than within each agency.

- Allows for flexibility in accommodations. Needs vary from person-to-person and case-to-case. For example, in the case of workplace accommodations for DHH team members, one full-time researcher may request full-time ASL interpretation on-site, while another might prefer to work primarily through digital text channels; only requiring ASL interpretation for staff meetings and other group activities.

- Potentially reduces federal government financial and human resources currently expended in supporting such requests by eliminating duplication of effort across agencies or, at minimum streamlining processes within agencies.

Such a process might follow these steps below. The example below is from the National Science Foundation (NSF), but the same, or similar process could be done within any agency:

- PI receives notification of grant award from NSF. PI identifies need for A & A services at start, or at any time during the grant period

- PI (or SRS staff) submits request for A&A funding support to NSF. Request includes NSF program name and award number, the specifics of the requested A & A support, a budget justification and three vendor quotes (if needed)

- Use of funds is authorized, and funding is released to PI’s institution and acquisition would follow their standard purchasing or contracting procedures

- PI submits receipts/ paid vendor invoice to funding body

- PI cites and documents use of funds in annual report, or equivalent, to NSF

Current Policies and Practices

Pre-Award Funding

Principal Investigators (PIs) who request A&A support for themselves or for other members of the research team are sometimes required to apply for it in their initial grant proposals. This approach has several flaws.

First and foremost, this funding process reduces the direct application of research dollars for these PIs and their teams compared to other researchers in the same program. Simply put, if two applicants are applying for a $100,000 grant, and one needs to fund $10,000 worth of accommodations, services, and equipment out of the award, they have $10,000 less to pursue the proposed research activities. This essentially creates a “10% A & A tax” on the overall research funding request.

Lived Experience Example

In a real world example, the author and his colleague, the late Dr. Mel Chua, were awarded a $60,000, one year grant to do a qualitative research case study as part of the Ford Foundation Critical Digital Infrastructure Research cohort. As Dr. Chua was Deaf, the PIs pointed out to Ford that $10,000 worth of support services would be needed to cover costs for

- American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters during the qualitative interviews and advisory committee meetings

- Transcription of the interviews

- ASL Interpreting for conference dissemination and collection of comments at formal and informal meetings during those conferences

We communicated the fact that spending general research award money on those services would reduce the research work the funds were awarded to support. The Ford Foundation understood and provided an additional $10,000 as post-award funding to cover those services. Ford did not inform the PIs as to whether that support came from another directed set of funds for A&A support or from discretionary dollars within the foundation.

Second, it can be limiting for the funded project to work with or hire PWDs as co-PIs, students, or if they weren’t already part of the original grant proposal. For example, suppose a research project is initially awarded funding for four years without A&A support and then a promising team member who is a PWD appears on the scene in year three who would require it. In this case, PIs then must:

- Reallocate research dollars meant for other uses within the grant to support A&A;

- Find other funding to support those needs within their institution;

- Navigate the varied post-award support landscape, sometimes going so far as to write an entirely new full proposal with a significant review timeline, to try to get support. If this happens off cycle, the funding might not even arrive until the last few months of the fourth year.

- Or, not hire the person in question because they can’t provide the needed A&A.

Post-Award Funding

Some agencies have programs for post-award supplemental funding that address the challenges described above. While these are well-intentioned, many are complicated and often have different timelines, requirements, etc. In some cases, a single supplemental funding source may be addressing all aspects of diversity, equity and inclusion as well as A&A. The needs and costs in the first three categories are significantly different than in the last. Some post-award pools come from the same agency’s annual allocation program-wide. If those funds have been primarily expended on the initial awards for the solicitation, there may be little, or no money left to support post-award funding for needed accommodations. The table below briefly illustrates the range of variability across a subset of representative supplemental funding programs. There are links in the top row of the table to access the complete program information. Beyond the programs in this table, more extensive lists of NSF and NIH offerings are provided by those agencies. One example is the NSF Dear Colleague Letter Persons with Disabilities – STEM Engagement and Access.

Ideally these policies and procedures, and others like them, would be replaced by a common, post-award process. PIs or their institutions would simply submit the identifying information on the grant that had been awarded and the needs for Accommodations and Accessibility to support team members with disabilities at any time during the grant period.

Plan of Action

The OSTP, possibly in a National Science and Technology Council interworking group process,, should conduct an internal review of the A&A policies and procedures for grant programs from federal scientific research aligned agencies. This could be led by OSTP directly or under their auspices and led by either NSF or the National Institute of Health (NIH). Participants would be relevant personnel from DOE, DOD, NASA, USDA, EPA, NOAA, NIST and HHS, at minimum. The goal should be to create a draft of a single, streamlined policy and process, post-award, for all federal grant programs or a new section in the uniform guidance for federal funding agencies.

There should be an analysis of the percentages, size and amounts of awards currently being made to support A&A in research funding grant programs. It’s not clear how the various funding ranges and caps listed in the table above were determined or if they meet the needs. One goal of this analysis would be to determine how well current needs within and across agencies are being met and what future needs might be.

A second goal would be to look at the level of duplication of effort and scope of manpower savings that might be attained by moving to a single, streamlined policy. This might be a coordinated process between OMB and OSTP or a separate one done by OMB. No matter how it is coordinated, an understanding of these issues should inform whatever new policies or new additions to 2 CFR 200 would emerge.

A third goal of this evaluation could be to consider if the support for A&A post-award funding might best be served by a single entity across all federal grants, consolidating the personnel expertise and policy and process recommendations in one place. It would be a significant change, and could require an act of Congress to achieve, but from the point of view of the authors it might be the most efficient way to serve grantees who are PWDs.

Once the initial reviews as described above, or a similar process is completed, the next step should be a convening of stakeholders outside of the federal government with the purpose of providing input to the streamlined draft policy. These stakeholder entities could include, but should not be limited to, the National Association for the Deaf, The American Foundation for the Blind, The American Association of People with Disabilities and the American Diabetes Association. One of the goals of that convening should be a discussion, and decision, as to whether a period of public comment should be put in place as well, before the new policy is adopted.

Conclusion

The above plan of action should be pursued so that more PWDS will be able to participate, or have their participation improved, in federally funded research. A policy like the one described above lays the groundwork and provides a more level playing field for Open Science to become more accessible and accommodating.It also opens the door for streamlined processes, reduced duplication of effort and greater efficiency within the engine of Federal Science support.

Acknowledgments

The roots of this effort began when the author and Dr. Mel Chua and Stephen Jacobs received funding for their research as part of the first Critical Digital Infrastructure research cohort and were able to negotiate for accessibility support services outside their award. Those who provided input on the position paper this was based on are:

- Dr. Mel Chua, Independent Researcher

- Dr. Liz Hare, Quantitative Geneticist, Dog Genetics LLC

- Dr. Christopher Kurz, Professor and Director of Mathematics and Science Language and Learning Lab, National Technical Institute for the Deaf

- Luticha Andre-Doucette, Catalyst Consulting

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Based on the percentage of PWDs in the general population size, conference funders should assume that some of their presenters or attendees will need accommodations. Funding from federal agencies should be made available to provide an initial minimum-level of support for necessary A & A. The event organizers should be able to apply for additional support above the minimum level if needed, provided participant requests are made within a stated time before the event. For example, a stipulated deadline of six weeks before the event to request supplemental accommodation, so that the organizers can acquire what’s needed within thirty days of the event.

Yes, in several ways. In general, most of the support needed for these is in service provision vs. hardware/software procurement. However, understanding the breadth and depth of issues surrounding human services support is more complex and outside the experience of most PIs running a conference in their own scientific discipline.

Again, using the example of DHH researchers who are attending a conference. A conference might default to providing a team of two interpreters during the conference sessions, as two per hour is the standard used. Should a group of DHH researchers attend the conference and wish to go to different sessions or meetings during the same convening, the organizers may not have provided enough interpreters to support those opportunities.

By providing interpretation for formal sessions only, DHH attendees are excluded from a key piece of these events, conversations outside of scheduled sessions. This applies to both formally planned and spontaneous ones. They might occur before, during, or after official sessions, during a meal offsite, etc. Ideally interpreters would be provided for these as well.

These issues, and others related to other groups of PWDs, are beyond the experience of most PIs who have received event funding.

There are some federal agency guides produced for addressing interpreting and other concerns, such as the “Guide to Developing a Language Access Plan” Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). These are often written to address meeting needs of full-time employees on site in office settings. These generally cover various cases not needed by a conference convener and may not address what they need for their specific use case. It might be that the average conference chair and their logistics committee is a simply stated set of guidelines to address their short-term needs for their event. Additionally, a directory of where to hire providers with the appropriate skill sets and domain knowledge to meet the needs of PWDs attending their events would be an incredible aid to all concerned.

The policy review process outlined above should include research to determine a base level of A & A support for conferences. They might recommend a preferred federal guide to these resources or identify an existing one.

Using Title 1 to Unlock Equity-Focused Innovation for Students

Congress should approve a new allowable use of Title I spending that specifically enables and encourages school districts to use funds for activities that support and drive equity-focused innovation. The persistent equity gap between wealthy and poor students in our country, and the continuing challenges caused by the pandemic, demand new, more effective strategies to help the students who are most underserved by our public education system.

Efforts focused on the distribution of all education funding, and Title I in particular, have focused on ensuring that funds flow to students and districts with the highest need. Given the persistence of achievement and opportunity gaps across race, class, and socioeconomic status, there is still work to be done on this front. Further, rapidly developing technologies such as artificial intelligence and immersive technologies are opening up new possibilities for students and teachers. However, these solutions are not enough. Realizing the full potential of funding streams and emerging technologies to transform student outcomes requires new solutions designed alongside the communities they are intended to serve.

To finally close the equity gap, districts must invest in developing, evaluating, and implementing new solutions to meet the needs of students and families today and in a rapidly changing future. Using Title I funding to create a continuous, improvement-oriented research and development (R&D) infrastructure supporting innovations at scale will generate the systemic changes needed to reach the students in highest need of new, creative, and more effective solutions to support their learning.

Challenge and Opportunity

Billions of dollars of federal funding have been distributed to school districts since the authorization of Title I federal funding under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), introduced in 1965 (later reauthorized under the Every Student Succeeds Act [ESSA]). In 2023 alone, Congress approved $18.4 billion in Title I funding. This funding is designed to provide targeted resources to school districts to ensure that students from low-income families can meet rigorous academic standards and have access to post-secondary opportunities. ESEA was authorized during the height of the Civil Rights Movement with the intent of addressing the two primary goals of (1) ensuring traditionally disadvantaged students were better served in an effort to create more equitable public education, and (2) addressing the funding disparities created by differences in local property taxes, the predominant source of education funding in most districts. These dual purposes were ultimately aimed at ensuring that a student’s zip code did not define their destiny.

The passing of ESEA was a watershed moment. Prior to its authorization, education policy was left mostly up to states and localities. In authorizing ESEA, the federal government launched ongoing involvement in public education and initiated a focus on principles of equity in education.

Further, research shows that school spending matters: Increased funding has been found to be associated with higher levels of student achievement. However, despite the increased spending for students from low-income families via Title I, the literature on outcomes of Title 1 funding is mixed. The limited impact of Title I funds on outcomes may be a result of municipalities using Title I funding to supplant or fill gaps in their overall funding and programs, instead of being used as an additive funding stream meant to equalize funding between poorer and richer districts. Additionally, while a taxonomy of options is provided to bring rigor and research to how districts use Title funding, the narrow set of options has not yielded the intended outcomes at scale. For instance, studies have repeatedly shown that school turnaround efforts have proven particularly stubborn and not shown the hoped-for outcomes.

The equity gap that ESEA was created to address has not been erased. There is still a persistent achievement gap between high- and low-income students in the nation. The emergence of COVID in 2020 uprooted the public education system, and its impact on student learning, as measured by test scores, is profound. Students lost ground across all focus areas and grades. Now, in the post-pandemic era, students have continued to lose ground. The “COVID Generation” of students are behind where they should be, and many are disengaged or questioning the value of their public education. Chronic absenteeism is increasing across all grades, races, and incomes. These challenges create an imperative for schools and districts to deepen their understanding of the interests and needs of students and families. The quick technological advancements in the education market are changing what is possible and available to students, while also raising important questions around ethics, student agency, and equitable access to technology. It is a moment of immense potential in public education.

Title I funds are a key mechanism to addressing the array of challenges in education ranging from equity to fast-paced advancements in technology transforming the field. In its current form, Title I allocation occurs via four distribution criteria. The majority of funding is allocated via basic grants that are determined entirely on individual student income eligibility. The other three criteria allocate funding based on the concentration of student financial need within a district. Those looking to rethink allocation often argue for considering impact per dollar allocated, beyond solely need as a qualifying indicator for funding, essentially taking into account cost of living and services in an area to understand how far additional funding will stretch in order to more accurately equalize funding. It is essential that Title I is redesigned beyond redoing the distribution formula. The money allocated must be spent differently—more creatively, innovatively, and wisely—in order to ensure that the needs of the most vulnerable students are finally met.

Plan of Action

Title I needs a new allowable spending category approved that specifically enables and encourages districts to use funds for activities that drive equity-focused innovation. Making room for innovation grounded in equity is particularly important in this present moment. Equity has always been important, but there are now tools to better understand and implement systems to address it. As school districts continue to recover from the pandemic-related disruptions, explore new edtech learning options, and prepare for an increasingly diverse population of students for the future, they must be encouraged to drive the creation of better solutions for students via adding a spending category that indicates the value the federal government sees in innovating for equity. Some of the spending options highlighted below are feasible under the current Title I language. By encouraging these options tethered specifically to innovation, district leadership will feel more flexibility to spend on programs that can foster equity-driven innovation and create space for the new solutions that are needed to improve outcomes for students.

Innovation, in this context, is any systemic change that brings new services, tools, or ways of working into school districts that improve the learning opportunities and experience for students. Equity-focused innovation refers to innovation efforts that are specifically focused on improving equity within school systems. It is a solution-finding process to meet the needs of students and families. Innovation can be new, technology-driven tools for students, teachers, or others who support student learning. But innovation is not limited to technology. Allowing Title I funding to be used for activities that support and foster equity-driven innovation could also include:

- Improving data systems and usage: Ensure that school districts have agile data systems equipped to identify student weaknesses and determine the effectiveness of solutions. As more solutions come to market and are developed internally, both AI and otherwise, school systems will be able to better serve students qualifying for Title I funding if they can meaningfully assess what is and is not working and use that information to guide strategy and decision-making.

- Leadership development: Support the research and development, futurist, and equitable design skills of systems to enable leaders to guide innovation from within districts alongside students and families.

- Testing new solutions: Title I funding currently can be spent primarily on evidence-based programs; enabling the use of funding for innovative pilots that have community support would provide space to discover more effective solutions.

- Incentivizing systemic district innovation: School districts could use funding to support the creation of innovation offices within their administration structure that are tasked with developing an innovation agenda rooted in district and student needs and spearheading solutions.

- Building networks for change: District leaders charged with creating and sustaining new learning models, school models, and programs often do so in isolation. Allowing districts to fund the creation of new programs and support existing organizations that bring together school system innovators and researchers to capture and share best practices, promising new solutions, and lessons learned from testing can lead to better adoption and scale of promising new models. There are already networks that exist, for instance, the Regional Education Laboratory Program. Funding could be used to support these existing networks or to develop new networks specifically tailored to meet the needs of leaders driving these innovations.

Expanding Title I funding to make room for innovative ideas and solutions within school systems has the potential to unlock new, more effective solutions that will help close equity gaps, but spending available education funds on unproven ideas can be risky. It is essential that the Department of Education issues carefully constructed guardrails to allow ample space for new solutions to emerge and scale, while also protecting students and ensuring their educational needs are still met. These guardrails and design principles would ensure that funds are spent in impactful ways that support innovation and building an evidence base. Examples of guardrails for a school system spending Title I funding on innovation could include:

- Innovation agenda: There should be a clearly articulated, publicly available innovation agenda that lays out how needs are being identified using quantitative and qualitative data and research, the methods of how innovations are being developed and selected, the goals of the innovation and how the work will grow (or not) based on clearly defined metrics of success.

- Clear research & development process: New ideas, tools, and ways of working must come into the district with a clear R&D process that begins with student and community needs and then regularly interrogates what is and is not working, tries to understand the why behind what is working, and expands promising practices.

- Pilot size limits: Unproven and innovative ideas should begin as pilots in order to ensure they are tested, evaluated, and proven before being used more broadly.

- Timeline requirements for results: New innovation funded via Title I funding should have a limited timeline during which the system needs to show improvement and evidence of impact.

- Clear outcomes that the innovation is aiming for: Innovation is not about something new for the sake of something new. Innovation funding via Title I funding must be linked to specific outcomes that will help achieve the overarching programmatic goal of increasing educational equity in our country.

While creating an authorized funding category for equity-focused innovation through Title I would have the most widespread impact, other ways to drive equitable innovation should also be pursued in the short term, such as through the new Comprehensive Center (CC), set to open in fall 2024, that will focus on equitable funding. It should prioritize developing the skills in district leaders to enable and drive equity-driven innovation.

Conclusion

Investment in innovation through Title I funding can feel high risk compared to the more comfortable route of spending only on proven solutions. However, many ways of traditional spending are not currently working at scale. Investing in innovation creates the space to find solutions that actually work for students—especially those that are farthest from opportunity and whom Title I funding is intended to support. Despite the perceived risk, investing in innovation is not a high-risk path when coupled with a clear sense of the community need, guardrails to promote responsible R&D and piloting processes, predetermined outcome goals, and the data systems to support transparency on progress. Large-scale, federal investment in creating space for innovation through Title I funding in—an already well-known mode of district funding not currently realizing its desired impact—will create solutions within public education that give students the opportunities they need and deserve.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

This memo was developed in partnership with the Alliance for Learning Innovation, a coalition dedicated to advocating for building a better research and development infrastructure in education for the benefit of all students. Read more education R&D memos developed in partnership with ALI here.

How A Defunct Policy Is Still Impacting 11 Million People 90 Years Later

Have you ever noticed a lack of tree cover in certain areas of a city? Have you ever visited a city and been advised to avoid certain districts or communities? Perhaps you even recall these visual shifts occurring immediately after crossing a particular road or highway?

If so, what you experienced was likely by design:

In the early 20th century, Black communities across the U.S. were subjected to economic constraint and social isolation through housing policies that mandated segregation. Black communities were systematically excluded from the housing benefits offered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). The HOLC served as the basis of the National Housing Act of 1934, which ratified the Federal Housing Authority (FHA).

Housing policy discrimination was further exacerbated by the FHA refusing to insure mortgages near and within Black neighborhoods. The HOLC provided lenders with maps that circled areas with sizeable black populations with red markers—a practice now referred to as redlining. While the systematic practice of redlining ended in 1968 under The Fair Housing Act of 1968, redlining continues to economically impair over 11 million Americans—and less than half are Black.

You are probably thinking (1) how is this possible? (2) How could a defunct 20th-century policy designed to discriminate against Black communities still impact over 11 million—mostly non-Black—Americans today? The answer is the same for both questions: place-based discrimination.

Policies such as redlining are designed to worsen the material conditions of a target group by preventing investment in the places where they live. Over time, this results in physical locations that are systemically denied access to features such as loans, enterprise, and ecosystem services simply due to their location or place. Place-based discrimination is the principal mechanism of redlining effects, and consequently, costs taxpayers millions of dollars per year.

What is the problem?

Starting in the 1990s, during the Clinton Administration, billions of dollars in tax credits were devoted towards community development and economic growth through the use of special tax credits that attract private investments (Table 1). One of the principal agents from this funding to address place-based discrimination was the creation of Community Development Entities (CDEs). According to the New Markets Tax Credit Coalition, CDEs are private entities that have “demonstrated” an interest in serving or providing capital to low-income- communities (LICs) and individuals (LIIs). Once certified, CDEs are eligible to apply for a special tax credit, New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC), through the Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) Fund.

However, this program, and others like it, have had a negligible impact on addressing the systemic implications of redlining . A recent Urban Institute report found that inequity in capital flow and investment trends within cities (i.e., Chicago) is driven by residential lending patterns. Highlighting the inequalities that exist between investment among neighborhoods with different racial and income demographics, the analysts surmise that redressing economic downturn involves expanding investments into divested neighborhoods. To date, more than $71 billion have been awarded to CDE’s, and yet, historically-redlined areas remain economically desolate. If these programs are intended to economically revitalize historically-redlined areas, then these programs are not doing what they are supposed to do.

One example of this is the city of Philadelphia:

Philadelphia, a city in the top ten for redlined populations, possesses tens of thousands of vacant buildings and lots that are overlaid by redlining and riddled with brownfield sites. According to the Philadelphia Office of the Controller, historically redlined communities of Philadelphia continue to experience disproportionate amounts of poverty, poor health outcomes, limited educational attainment, unemployment, and violent crime compared to non-redlined areas in the city.

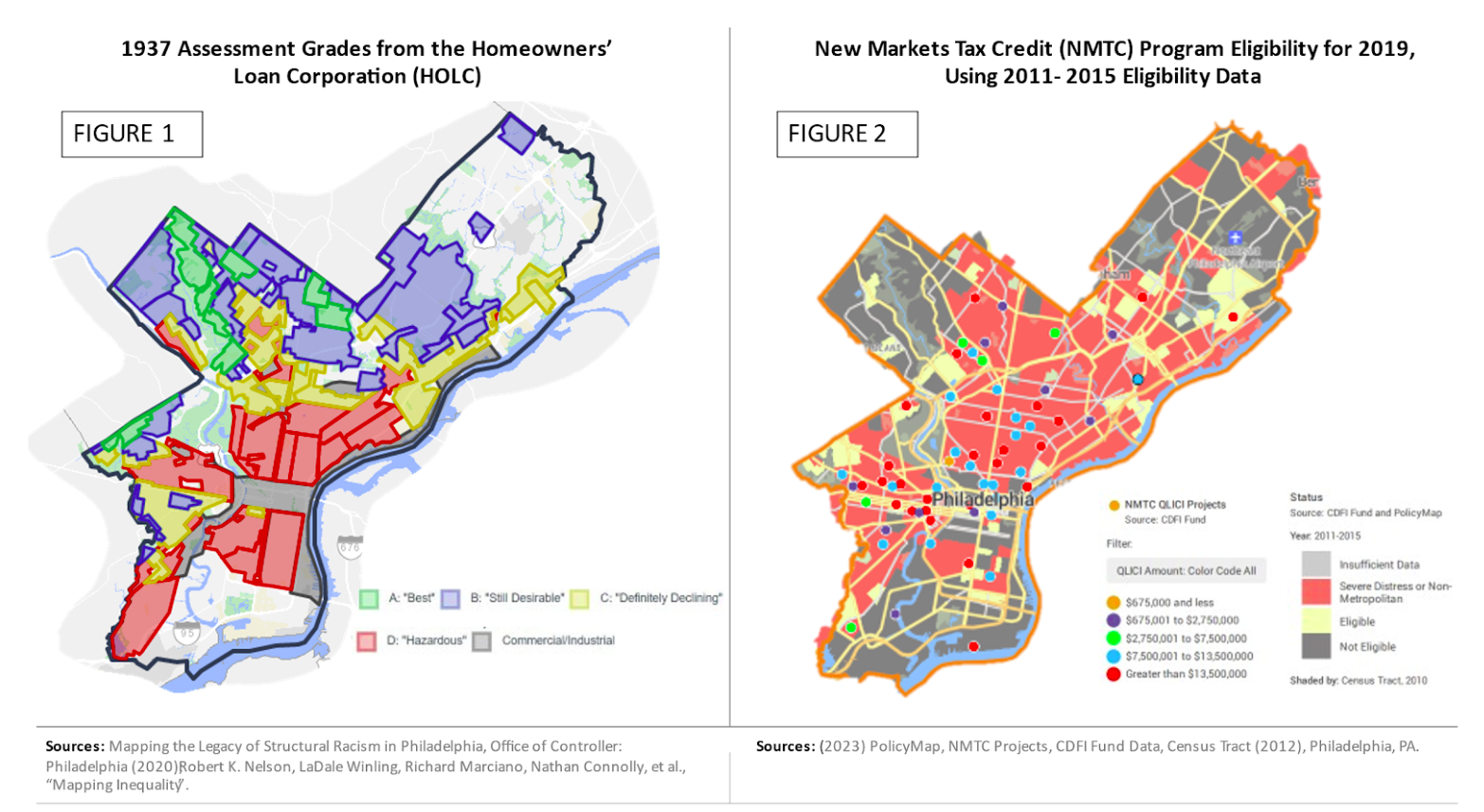

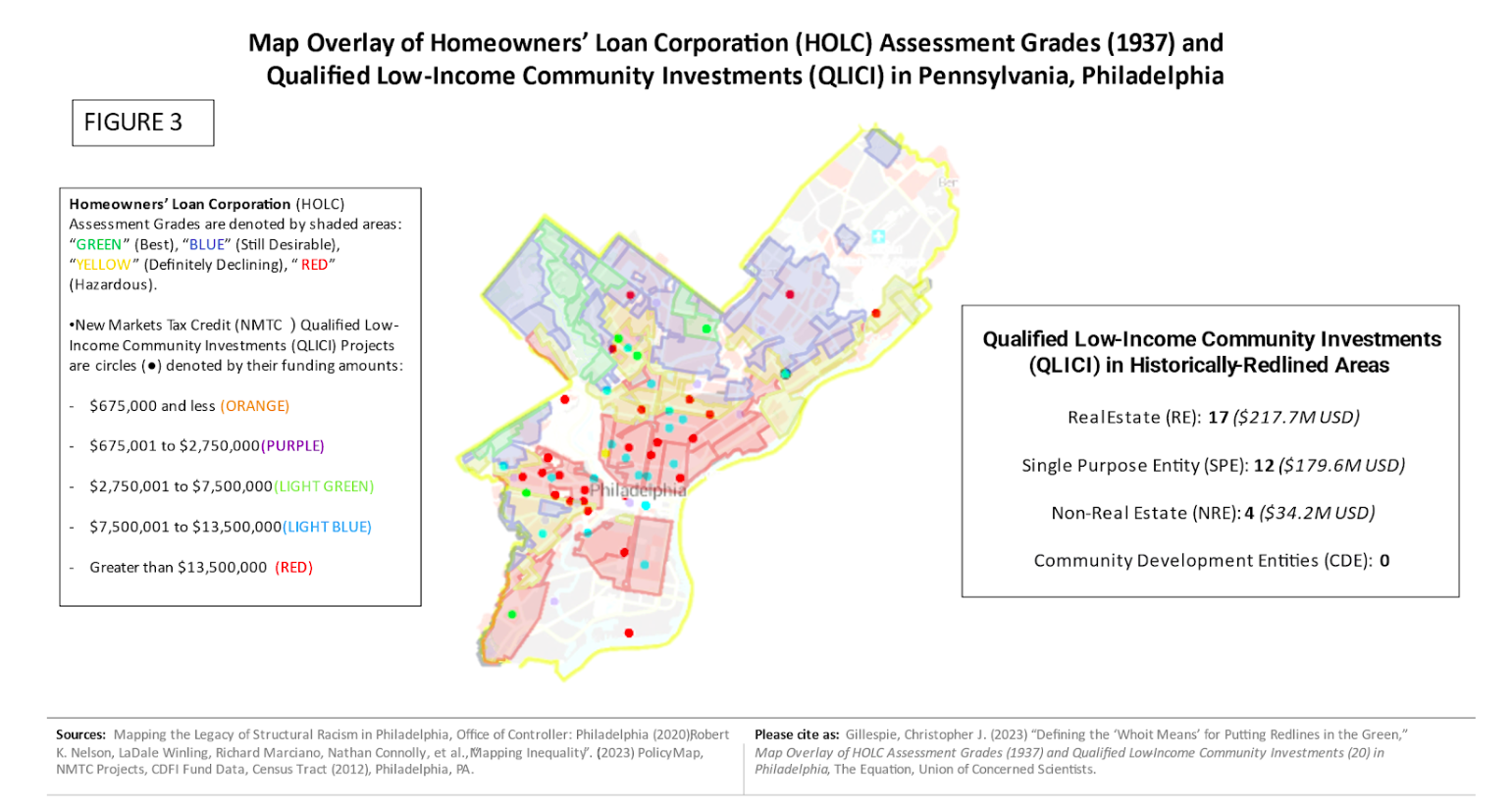

By analyzing HOLC assessment grades (1937) and New Market Tax Credit (NMTC) Program Eligibility (i.e., PolicyMap, projects from 2015-2019) for Philadelphia, PA, I found that of the 30+ Qualified Low-Income Community Investments (QLICIs) in historically-redlined areas, totaling over $400 million in tax credits, none are categorized as Community Development Entities (CDEs).

HOLC assessment grades (1937) vs. New Market Tax Credit (NMTC) Program Eligibility

Of the 30+ Qualified Low-Income Community Investments (QLICIs) in historically-redlined areas, totaling over $400 million in tax credits, none are categorized as Community Development Entities (CDEs).

Meanwhile, the Philadelphia City Council just passed a budget that allocates a record $788 million to the Philadelphia Police Department (PPD). Recent studies show that fatal encounters with police are more likely to occur within historically-redlined areas. It appears the nicest buildings in redlined areas may very well be police stations.

Yet, public investment has been more concerned with maintaining systems of oppression than reversing them. Why continue to invest in systems that do not create wealth? No matter your perception of American policing, the following is clear: policing does not create wealth for distressed communities.

Currently, there are 200+ cities and thousands of communities that are, like Philadelphia, enduring the systemic implications of redlining.

What would happen if public investments were allocated towards restorative policy actions within historically-redlined areas?

A federal program that amalgamates the best elements of community-driven inventiveness into a vehicle for innovative and sustainable economic development. That is, a program that promotes economic revitalization of historically-redlined communities through multipurpose, community-owned enterprises called Innovative Neighborhood Markets (INMs).

What is the policy action?

One thing that urban policy initiatives have made clear, is that distressed communities are prime real-estate targets for private developers . A new federal effort could ensure that investment opportunities are also accessible to community members seeking to launch place-based businesses and enterprises. Businesses and enterprises of this sort will not only reduce urban blight in historically-redlined communities, but also serve as avenues for the direct state, local, and private investment needed to address historical inequities.

The Biden-Harris Administration can combat redlining through a placed-based community investment program, coined Putting Redlines in the Green: Economic Revitalization Through Innovative Neighborhood Markets (PRITG), that affords historically-redlined communities the ability to establish their own profitable enterprise before outside parties (i.e., private developers).

These Innovative Neighborhood Markets (INMs) would be resource hubs that provide affordable grocery items (i.e., fresh produce, meats, dairy, etc.); an outlet for residents of the community to market goods and services (i.e., small businesses); and create cross-sector initiatives that build community enterprise and increase greenspace (i.e., Farm to Neighborhood Model [F2NM], parks, gardens, and tree cover). Most importantly, INM’s are community owned. Through community governance, the community elects and authorizes the types of place-based businesses and enterprises that are present within their INM.

Do you remember the Philadelphia example from earlier?

Under PTRIG, a number of those underutilized structures or vacant spaces are transformed into a vested, profitable, and sustainable community resource. The majority of the financial capital remains within the community, and economic gains are partially earmarked for community revitalization (i.e., soil remediation for brownfield sites, community restoration, and construction of greenspace).

All Taxpayers Benefit

By legally and financially empowering communities with ownership, PRITG will incentivize investment and development that can actually reduce taxpayer liability. For example, the INM can generate the funding to invest in more attractive (and expensive) treecover and landscaping that will reduce the impact of heat islands and imperviousness related to redlining, thereby reducing taxpayer liability by more than $308 million dollars per year. Implementation of PTRIG will decrease taxpayer burden through profit-driven and self-supporting community services.

“Fair and Equal” Access

Another beneficial aspect of this policy involves increasing community access to financial provisions without third-party obstacles (i.e., CDEs and CDFIs). Black and Hispanic home loan applicants are charged higher interest rates than White home loan applicants, resulting in Black and Hispanic borrowers paying $765 million in additional interest per year. Discriminatory practices only succeed in worsening community divestment and increasing the resident displacement which disproportionately impact minority residents. Through the economic-agency provided by PRITG, historically-redlined communities would have heightened protection against lending discrimination, gentrification, and displacement.

Moreover, PTRIG would reinforce the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)’s Combating Redlining Initiative in ensuring that formerly redlined neighborhoods receive “fair and equal access” to the lending opportunities that are—and always have been—available to non-redlined, and majority-White, neighborhoods.

While INMs possess aspects of grocery stores, community banks, business improvement districts (BIDs), and farmers markets, they would differ in one particular area: community wealth.

What is Community Wealth?

As someone who grew up in Champaign, Illinois (Douglas Park), and whose family currently lives in a historically-redlined community (Lansing, MI), it brings me peace to reimagine my community with an INM.

Until my early 20’s, I spent most of my life largely unaware of the importance of community wealth on individual empowerment and its impact on the maintenance of cultural identity. For me, reimagining my community with an INM is not just about correcting the past, it is about enriching the uniqueness of what makes our home, Home.

In general, a community wealth building process needs to address the lack of an asset in a way that builds community sustainability. That is the materialization of a communal epicenter(s) that produces a sense of ownership and pride.

So how would INMs build community wealth? Simple. The community, as a whole, would be defined as the ownership group. Each community member would be legally referenced as a shareholder of this newly acquired, financially-appreciating, community-owned enterprise.

Community Ownership Key to Community Wealth

According to Evan Absher, Chief Executive Officer at Folks Capital, there are currently two broad ways of understanding community ownership.

The first type involves community ownership in the form of trusts or fiduciary arrangements between a community entity and an independent financial establishment. This structure creates a community entity that holds the financial wealth and is subject to some form of community governance. This structure includes entities such as Community Investment Trusts, Community Land Trusts, and Mixed-Income Neighborhood Trust. These structures ensure permanent and lasting control of the land and fidelity to charitable purposes. However, these entities often do not increase actual ownership or produce meaningful wealth at the individual or family levels. Further, they are often nonprofits and can struggle with attracting capital and sustainability.

The second type of community ownership is specifically targeted at individuals and families. These are models that focus on financial agency and ownership of land and property by people within communities. This concept includes models such as employee-ownership, Co-operatives, ROC-USA’s model, and Folks Capital’s Neighborhood Equity Model. These models have an advantage in wealth building and agency for the families involved. The benefit of this second concept of community ownership is that community members have the autonomy to (1) choose to sell their ownership share back to the community fund; (2) receive pro rata (dividend) payments; and/or (3) if the community chooses, sell the enterprise to “would-be gentrifiers.”

Regardless, the community receives more empowerment than was ever offered by previous economic revitalization models (i.e., Opportunity Zones) [See Table 1]. However these models sometimes lack the permanence or control of the other models. If not structured thoughtfully, this lack of control poses a risk of further gentrification.

Regardless of the approach, all models should seek first to center communities and people in the governance and benefits of the model. Institutionalizing models is not the objective. Closing the wealth gap and ending disparities in economic, health, and education outcomes are the ultimate goal.

However, an important question is raised by this policy: who counts as community—especially when talking about the ownership of an individual building?

Are multiple communities expected to be consolidated into one community for the sake of ease? Would that be fair to those communities?

The challenge is making ownership meaningful. Understandably, a resident may possess more pride if their stake in an INM is $1000 opposed to 20 cents.

Thus, communities that are smaller in size may be most benefited by the establishment of an INM. This is not to say that large historically-redlined areas do not stand to gain from INM establishment. Quite the contrary. INMs are designed to not only enfranchise the local communities , but also revitalize the place through restorative, economic, and environmental justice.

Nevertheless, if PTRIG is to provide communities with tools that guarantee full community empowerment, then factors of community ownership should be considered.

Now, one final question remains, and it can only be answered by those within historically-redlined communities: “Who is your community?”

Addressing Online Harassment and Abuse through a Collaborative Digital Hub

Efforts to monitor and combat online harassment have fallen short due to a lack of cooperation and information-sharing across stakeholders, disproportionately hurting women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ individuals. We propose that the White House Task Force to Address Online Harassment and Abuse convene government actors, civil society organizations, and industry representatives to create an Anti-Online Harassment (AOH) Hub to improve and standardize responses to online harassment and to provide evidence-based recommendations to the Task Force. This Hub will include a data-collection mechanism for research and analysis while also connecting survivors with social media companies, law enforcement, legal support, and other necessary resources. This approach will open pathways for survivors to better access the support and recourse they need and also create standardized record-keeping mechanisms that can provide evidence for and enable long-term policy change.

Challenge and Opportunity

The online world is rife with hate and harassment, disproportionately hurting women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ individuals. A research study by Pew indicated that 47% of women were harassed online for their gender compared to 18% of men, while 54% of Black or Hispanic internet users faced race-based harassment online compared to 17% of White users. Seven in 10 LGBTQ+ adults have experienced online harassment, and 51% faced even more severe forms of abuse. Meanwhile, existing measures to combat online harassment continue to fall short, leaving victims with limited means for recourse or protection.

Numerous factors contribute to these shortcomings. Social media companies are opaque, and when survivors turn to platforms for assistance, they are often met with automated responses and few means to appeal or even contact a human representative who could provide more personalized assistance. Many survivors of harassment face threats that escalate from online to real life, leading them to seek help from law enforcement. While most states have laws against cyberbullying, law enforcement agencies are often ill-trained and ill-equipped to navigate the complex web of laws involved and the available processes through which they could provide assistance. And while there are nongovernmental organizations and companies that develop tools and provide services for survivors of online harassment, the onus continues to lie primarily on the survivor to reach out and navigate what is often both an overwhelming and a traumatic landscape of needs. Although resources exist, finding the correct organizations and reaching out can be difficult and time-consuming. Most often, the burden remains on the victims to manage and monitor their own online presence and safety.

On a larger, systemic scale, the lack of available data to quantitatively analyze the scope and extent of online harassment hinders the ability of researchers and interested stakeholders to develop effective, long-term solutions and to hold social media companies accountable. Lack of large-scale, cross-sector and cross-platform data further hinders efforts to map out the exact scale of the issue, as well as provide evidence-based arguments for changes in policy. As the landscape of online abuse is ever changing and evolving, up-to-date information about the lexicons and phrases that are used in attacks also change.

Forming the AOH Hub will improve the collection and monitoring of online harassment while preserving victims’ privacy; this data can also be used to develop future interventions and regulations. In addition, the Hub will streamline the process of receiving aid for those targeted by online harassment.

Plan of Action

Aim of proposal

The White House Task Force to Address Online Harassment and Abuse should form an Anti-Online Harassment Hub to monitor and combat online harassment. This Hub will center around a database that collects and indexes incidents of online harassment and abuse from technology companies’ self-reporting, through connections civil society groups have with survivors of harassment, and from reporting conducted by the general public and by targets of online abuse. Civil society actors that have conducted past work in providing resources and monitoring harassment incidents, ranging from academics to researchers to nonprofits, will run the AOH Hub in consortium as a steering committee. There are two aims for the creation of this hub.

First, the AOH Hub can promote collaboration within and across sectors, forging bonds among government, the technology sector, civil society, and the general public. This collaboration enables the centralization of connections and resources and brings together diverse resources and expertise to address a multifaceted problem.

Second, the Hub will include a data collection mechanism that can be used to create a record for policy and other structural reform. At present, the lack of data limits the ability of external actors to evaluate whether social media companies have worked adequately to combat harmful behavior on their platforms. An external data collection mechanism enables further accountability and can build the record for Congress and the Federal Trade Commission to take action where social media companies fall short. The allocated federal funding will be used to (1) facilitate the initial convening of experts across government departments and nonprofit organizations; (2) provide support for the engineering structure required to launch the Hub and database; (3) support the steering committee of civil society actors that will maintain this service; and (4) create training units for law enforcement officials on supporting survivors of online harassment.

Recommendation 1. Create a committee for governmental departments.

Survivors of online harassment struggle to find recourse, failed by legal technicalities in patchworks of laws across states and untrained law enforcement. The root of the problem is an outdated understanding of the implications and scale of online harassment and a lack of coordination across branches of government on who should handle online harassment and how to properly address such occurrences. A crucial first step is to examine and address these existing gaps. The Task Force should form a long-term committee of members across governmental departments whose work pertains to online harassment. This would include one person from each of the following organizations, nominated by senior staff:

- Department of Homeland Security

- Department of Justice

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Department of Health and Human Services

- Office on Violence Against Women

- Federal Trade Commission

This committee will be responsible for outlining fallibilities in the existing system and detailing the kind of information needed to fill those gaps. Then, the committee will outline a framework clearly establishing the recourse options available to harassment victims and the kinds of data collection required to prove a case of harassment. The framework should be completed within the first 6 months after the committee has been convened. After that, the committee will convene twice a year to determine how well the framework is working and, in the long term, implement reforms and updates to current laws and processes to increase the success rates of victims seeking assistance from governmental agencies.

Recommendation 2: Establish a committee for civil society organizations.

The Task Force shall also convene civil society organizations to help form the AOH Hub steering committee and gather a centralized set of resources. Victims will be able to access a centralized hotline and information page, and Hub personnel will then triage reports and direct victims to resources most helpful for their particular situation. This should reduce the burden on those who are targets of harassment campaigns to find the appropriate organizations that can help address their issues by matching incidents to appropriate resources.

To create the AOH Hub, members of the Task Force can map out civil society stakeholders in the space and solicit applications to achieve comprehensive and equitable representation across sectors. Relevant organizations include organizations/actors working on (but not limited to):

- Combating domestic violence and intimate partner violence

- Addressing technology-facilitated gender based violence (TF-GBV)

- Developing online tools for survivors of harassment to protect themselves

- Conducting policy work to improve policies on harassment

- Providing mental health support for survivors of harassment

- Servicing pro bono or other forms of legal assistance for survivors of harassment

- Connecting tech company representatives with survivors of harassment

- Researching methods to address online harassment and abuse

The Task Force will convene an initial meeting, during which core members will be selected to create an advisory board, act as a liaison across members, and conduct hiring for the personnel needed to redirect victims to needed services. Other secondary members will take part in collaboratively mapping out and sharing available resources, in order to understand where efforts overlap and complement each other. These resources will be consolidated, reviewed, and published as a public database of resources within a year of the group’s formation.

For secondary members, their primary obligation will be to connect with victims who have been recommended to their services. Core members, meanwhile, will meet quarterly to evaluate gaps in services and assistance provided and examine what more needs to be done to continue growing the robustness of services and aid provided.

Recommendation 3: Convene committee for industry.

After its formation, the AOH steering committee will be responsible for conducting outreach with industry partners to identify a designated team from each company best equipped to address issues pertaining to online abuse. After the first year of formation, the industry committee will provide operational reporting on existing measures within each company to address online harassment and examine gaps in existing approaches. Committee dialogue should also aim to create standardized responses to harassment incidents across industry actors and understandings of how to best uphold community guidelines and terms of service. This reporting will also create a framework for standardized best practices for data collection, in terms of the information collected on flagged cases of online harassment.

On a day-to-day basis, industry teams will be available resources for the hub, and cases can be redirected to these teams to provide person-to-person support for handling cases of harassment that require a personalized level of assistance and scale. This committee will aim to increase transparency regarding the reporting process and improve equity in responses to online harassment.

Recommendation 4: Gather committees to provide long-term recommendations for policy change.

On a yearly basis, representatives across the three committees will convene and share insights on existing measures and takeaways. These recommendations will be given to the Task Force and other relevant stakeholders, as well as be accessible by the general public. Three years after the formation of these committees, the groups will publish a report centralizing feedback and takeaway from all committees, and provide recommendations of improvement for moving forward.

Recommendation 5: Create a data-collection mechanism and standard reporting procedures.

The database will be run and maintained by the steering committee with support from the U.S. Digital Service, with funding from the Task Force for its initial development. The data collection mechanism will be informed by the frameworks provided by the committees that compose the Hub to create a trauma-informed and victim-centered framework surrounding the collection, protection, and use of the contained data. The database will be periodically reviewed by the steering committee to ensure that the nature and scope of data collection is necessary and respects the privacy of those whose data it contains. Stakeholders can use this data to analyze and provide evidence of the scale and cross-cutting nature of online harassment and abuse. The database would be populated using a standardized reporting form containing (1) details of the incident; (2) basic demographic data of the victim; (3) platform/means through which the incident occurred; (4) whether it is part of a larger organized campaign; (5) current status of the incident (e.g., whether a message was taken down, an account was suspended, the report is still ongoing); (6) categorization within existing proposed taxonomies indicating the type of abuse. This standardization of data collection would allow advocates to build cases regarding structured campaigns of abuse with well-documented evidence, and the database will archive and collect data across incidents to ensure accountability even if the originals are lost or removed.

The reporting form will be available online through the AOH Hub. Anyone with evidence of online harassment will be able to contribute to the database, including but not limited to victims of abuse, bystanders, researchers, civil society organizations, and platforms. To protect the privacy and safety of targets of harassment, this data will not be publicly available. Access will be limited to: (1) members of the Hub and its committees; (2) affiliates of the aforementioned members; (3) researchers and other stakeholders, after submitting an application stating reasons to access the data, plans for data use, and plans for maintaining data privacy and security. Published reports using data from this database will be nonidentifiable, such as with statistics being published in aggregate, and not be able to be linked back to individuals without express consent.

This database is intended to provide data to inform the committees in and partners of the Hub of the existing landscape of technology-facilitated abuse and violence. The large-scale, cross-domain, and cross-platform nature of the data collected will allow for better understanding and analysis of trends that may not be clear when analyzing specific incidents, and provide evidence regarding disproportionate harms to particular communities (such as women, people of color, LGBTQ+ individuals). Resources permitting, the Hub could also survey those who have been impacted by online abuse and harassment to better understand the needs of victims and survivors. This data aims to provide evidence for and help inform the recommendations made from the committees to the Task Force for policy change and further interventions.

Recommendation 6: Improve law enforcement support.

Law enforcement is often ill-equipped to handle issues of technology-facilitated abuse and violence. To address this, Congress should allocate funding for the Hub to create training materials for law enforcement nationwide. The developed materials will be added to training manuals and modules nationwide, to ensure that 911 operators and officers are aware of how to handle cases of online harassment and how state and federal law can apply to a range of scenarios. As part of the training, operators will also be notified to add records of 911 calls regarding online harassment to the Hub database, with the survivor’s consent.

Conclusion

As technology-facilitated violence and abuse proliferates, we call for funding to create a steering committee in which experts and stakeholders from civil society, academia, industry, and government can collaborate on monitoring and regulating online harassment across sectors and incidents. The resulting Anti-Online Harassment Hub would maintain a data-collection mechanism accessible to researchers to better understand online harassment as well as provide accountability for social media platforms to address the issue. Finally, the Hub would provide accessible resources for targets of harassment in a fashion that would reduce the burden on these individuals. Implementing these measures would create a safer online space where survivors are able to easily access the support they need and establish a basis for evidence-based, longer-term policy change.

Platform policies on hate and harassment differ in the redress and resolution they offer. Twitter’s proactive removal of racist abuse toward members of the England football team after the UEFA Euro 2020 Finals shows that it is technically feasible for abusive content to be proactively detected and removed by the platforms themselves. However, this appears to only be for high-profile situations or for well-known individuals. For the general public, the burden of dealing with abuse usually falls to the targets to report messages themselves, even as they are in the midst of receiving targeted harassment and threats. Indeed, the current processes for reporting incidents of harassment are often opaque and confusing. Once a report is made, targets of harassment have very little control over the resolution of the report or the speed at which it is addressed. Platforms also have different policies on whether and how a user is notified after a moderation decision is made. A lot of these notifications are also conducted through automated systems with no way to appeal, leaving users with limited means for recourse.

Recent years have seen an increase in efforts to combat online harassment. Most notably, in June 2022, Vice President Kamala Harris launched a new White House Task Force to Address Online Harassment and Abuse, co-chaired by the Gender Policy Council and the National Security Council. The Task Force aims to develop policy solutions to enhance accountability of perpetrators of online harm while expanding data collection efforts and increasing access to survivor-centered services. In March 2022, the Biden-Harris Administration also launched the Global Partnership for Action on Gender-Based Online Harassment and Abuse, alongside Australia, Denmark, South Korea, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The partnership works to advance shared principles and attitudes toward online harassment, improve prevention and response measures to gender-based online harassment, and expand data and access on gender-based online harassment.

Efforts focus on technical interventions, such as tools that increase individuals’ digital safety, automatically blur out slurs, or allow trusted individuals to moderate abusive messages directed towards victims’ accounts. There are also many guides that walk individuals through how to better manage their online presence or what to do in response to being targeted. Other organizations provide support for those who are victims and provide next steps, help with reporting, and information on better security practices. However, due to resource constraints, organizations may only be able to support specific types of targets, such as journalists, victims of intimate partner violence, or targets of gendered disinformation. This increases the burden on victims to find support for their specific needs. Academic institutions and researchers have also been developing tools and interventions that measure and address online abuse or improve content moderation. While there are increasing collaborations between academics and civil society, there are still gaps that prevent such interventions from being deployed to their full efficacy.

While complete privacy and security is extremely different to ensure in a technical sense, we envision a database design that preserves data privacy while maintaining its usability. First, the fields of information required for filing an incident report form would minimize the amount of personally identifiable information collected. As some data can be crowdsourced from the public and external observers, this part of the dataset would consist of existing public data. Nonpublicly available data would be entered by only individuals who are sharing incidents that are targeting them (e.g., direct messages), and individuals would be allowed to choose whether it is visible in the database or only shown in summary statistics. Furthermore, the data collection methods and the database structure will be periodically reviewed by the steering committee of civil society organizations, who will make recommendations for improvement as needed.

Data collection and reporting can be conducted internationally, as we recognize that limiting data collection to the U.S. will also undermine our goals of intersectionality. However, the hotline will likely have more comprehensive support for U.S.-based issues. In the long run, however, efforts can also be expanded internationally, as a cross-collaborative effort across multinational governments.

Creating a Fair Work Ombudsman to Bolster Protections for Gig Workers

To increase protections for fair work, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) should create an Office of the Ombudsman for Fair Work. Gig workers are a category of non-employee contract workers who engage in on-demand work, often through online platforms. They have had historic vulnerabilities in the U.S. economy. A large portion of gig workers are people of color, and the nature of their temporary and largely unregulated work can leave them vulnerable to economic instability and workplace abuse. Currently, there is no federal mechanism to protect gig workers, and state-level initiatives have not offered thorough enough policy redress. Establishing an Office of the Ombudsman would provide the Department of Labor with a central entity to investigate worker complaints against gig employers, collect data and evidence about the current gig economy, and provide education to gig workers about their rights. There is strong precedent for this policy solution, since bureaus across the federal government have successfully implemented ombudsmen that are independent and support vulnerable constituents. To ensure its legal and long-lasting status, the Secretary of Labor should establish this Office in an act of internal agency reorganization.

Challenge and Opportunity

The proportion of the U.S. workforce engaging in gig work has risen steadily in the past few decades, from 10.1% in 2005 to 15.8% in 2015 to roughly 20% in 2018. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, this trend has only accelerated, and a record number of Americans have now joined the gig economy and rely on its income. In a 2021 Pew Research study, over 16% of Americans reported having made money through online platform work alone, such as on apps like Uber and Doordash, which is merely a subset of gig work jobs. Gig workers in particular are more likely to be Black or Latino compared to the overall workforce.

Though millions of Americans rely on gig work, it does not provide critical employee benefits, such as minimum wage guarantees, parental leave, healthcare, overtime, unemployment insurance, or recourse for injuries incurred during work. According to an NPR survey, in 2018 more than half of contract workers received zero benefits through work. Further, the National Labor Relations Act, which protects employees’ rights to unionize and collectively bargain without retaliation, does not protect gig workers. This lack of benefits, rights, and voice leaves millions of workers more vulnerable than full-time employees to predatory employers, financial instability, and health crises, particularly during emergencies—such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, in 2022, inflation reached a decades-long high, and though the price of necessities has spiked, wages have not increased correspondingly. Extreme inflation hurts lower-income workers without savings the most and is especially dangerous to gig workers, some of whom make less than the federal minimum hourly wage and whose income and work are subject to constant flux.

State-level measures have as yet failed to create protections for all gig workers. In 2020, California passed AB5, legally reclassifying many gig workers as employees instead of independent contractors and thus entitling them to more benefits and protections. But further bills and Proposition 22 reverted several groups of gig workers, including online platform gig workers like Uber and Doordash drivers, to being independent contractors. Ongoing litigation related to Proposition 22 leaves the future status of online platform gig workers in California unclear. In 2022, Washington State passed ESHB 2076 guaranteeing online platform workers—but not all gig workers—the benefits of full-time employees.

This sparse patchwork of state-level measures, which only supports subgroups of gig workers, could trigger a “race to the bottom” in which employers of gig workers relocate to less strict states. Additionally, inconsistencies between state laws make it harder for gig workers to understand their rights and gain redress for grievances, harder for businesses to determine with certainty their duties and liabilities, and harder for states to enforce penalties when an employer is headquartered in one state and the gig worker lives in another. The status quo is also difficult for businesses that strive to be better employers because it creates downward pressure on the entire landscape of labor market competition. Ultimately, only federal policy action can fully address these inconsistencies and broadly increase protections and benefits for all gig workers.

The federal ombudsman’s office outlined in this proposal can serve as a resource for gig workers to understand the scope of their current rights, provide a voice to amplify their grievances and harms, and collect data and evidence to inform policy proposals. It is the first step toward a sustainable and comprehensive national solution that expands the rights of gig workers.

Specifically, clarifying what rights, benefits, and means of recourse gig workers do and do not have would help gig workers better plan for healthcare and other emergent needs. It would also allow better tracking of trends in the labor market and systemic detection of employee misclassification. Hearing gig workers’ complaints in a centralized office can help the Department of Labor more expeditiously address gig workers’ concerns in situations where they legally do have recourse and can otherwise help the Department of Labor better understand the needs of and harms experienced by all workers. Collecting broad-ranging data on gig workers in particular could help inform federal policy change on their rights and protections. Currently, most datasets are survey based and often leave out people who were not working a gig job at the time the survey was conducted but typically otherwise do. More broadly, because of its informal and dynamic nature, the gig economy is difficult to accurately count and characterize, and an entity that is specifically charged with coordinating and understanding this growing sector of the market is key.

Lastly, employees who are not gig workers are sometimes misclassified as such and thus lose out on benefits and protections they are legally entitled to. Having a centralized ombudsman office dedicated to gig work could expedite support of gig workers seeking to correct their classification status, which the Wage and Hour Division already generally deals with, as well as help the Department of Labor and other agencies collect data to clarify the scope of the problem.

Plan of Action

The Department of Labor should establish an Office of the Ombudsman for Fair Work. This office should be independent of Department of Labor agencies and officials, and it should report directly to the Secretary of Labor. The Office would operate on a federal level with authority over states.

The Secretary of Labor should establish the Office in an act of internal agency reorganization. By establishing the Office such that its powers do not contradict the Department of Labor’s statutory limitations, the Secretary can ensure the Office’s status as legal and long-lasting, due to the discretionary power of the Department to interpret its statutes.

The role of the Office of the Ombudsman for Fair Work would be threefold: to serve as a centralized point of contact for hearing complaints from gig workers; to act as a central resource and conduct outreach to gig workers about their rights and protections; and to collect data such as demographic, wage, and benefit trends on the labor practices of the gig economy. Together, these responsibilities ensure that this Office consolidates and augments the actions of the Department of Labor as they pertain to workers in the gig economy, regardless of their classification status.

The functions of the ombudsman should be as follows:

- Establish a clear and centralized mechanism for hearing, collating, and investigating complaints from workers in the gig economy, such as through a helpline or mobile app.

- Establish and administer an independent, neutral, and confidential process to receive, investigate, resolve, and provide redress for cases in which employers misrepresent to individuals that they are engaged as independent contractors when they’re actually engaged as employees.

- Commence court proceedings to enforce fair work practices and entitlements, as they pertain to workers in the gig economy, in conjunction with other offices in the DOL.

- Represent employees or contractors who are or may become a party to proceedings in court over unfair contracting practices, including but not limited to misclassification as independent contractors. The office would refer matters to interagency partners within the Department of Labor and across other organizations engaged in these proceedings, augmenting existing work where possible.

- Provide education, assistance, and advice to employees, employers, and organizations, including best practice guides to workplace relations or workplace practices and information about rights and protections for workers in the gig economy.

- Conduct outreach in multiple languages to gig economy workers informing them of their rights and protections and of the Office’s role to hear and address their complaints and entitlements.

- Serve as the central data collection and publication office for all gig-work-related data. The Office will publish a yearly report detailing demographic, wage, and benefit trends faced by gig workers. Data could be collected through outreach to gig workers or their employers, or through a new data-sharing agreement with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This data report would also summarize anonymized trends based on the complaints collected (as per function 1), including aggregate statistics on wage theft, reports of harassment or discrimination, and misclassification. These trends would also be broken down by demographic group to proactively identify salient inequities. The office may also provide separate data on platform workers, which may be easier to collect and collate, since platform workers are a particular subject of focus in current state legislation and litigation.

Establishing an Office of the Ombudsman for Fair Work within the Department of Labor will require costs of compensation for the ombudsman and staff, other operational costs, and litigation expenses. To reflect the need for a reaction to the rapid ongoing changes in gig economy platforms, a small portion of the Office’s budget should be set aside to support the appointment of a chief innovation officer, aimed at examining how technology can strengthen its operations. Some examples of tasks for this role include investigating and strengthening complaint sorting infrastructure, utilizing artificial intelligence to evaluate contracts for misclassification, and streamlining request for proposal processes.

Due to the continued growth of the gig economy, and the precarious status of gig workers in the onset of an economic recession, this Office should be established in the nearest possible window. Establishing, appointing, and initiating this office will require up to a year of time, and will require budgeting within the DOL.

There are many precedents of ombudsmen in federal office, including the Office of the Ombudsman for the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program within the Department of Labor. Additionally, the IRS established the Office of the Taxpayer Advocate, and the Department of Homeland Security has both a Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman and an Immigration Detention Ombudsman. These offices have helped educate constituents about their rights, resolved issues that an individual might have with that federal agency, and served as independent oversight bodies. The Australian Government has a Fair Work Ombudsman that provides resources to differentiate between an independent contractor and employee and investigates employers who may be engaging in sham contracting or other illegal practices. Following these examples, the Office of the Ombudsman for Fair Work should work within the Department of Labor to educate, assist, and provide redress for workers engaged in the gig economy.

Conclusion