Safeguarding Agricultural Research and Development Capacity

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) experienced a dramatic reduction in staff capacity in the first few months of the second Trump administration. More than 15,000 employees departed the agency through a combination of firings of probationary staff and two rounds of a deferred resignation program, shrinking USDA’s total workforce by 15%.

The administration’s government downsizing campaign is just getting started. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins recently unveiled a reorganization plan aimed at moving key agency functions outside of the National Capital Region. While the plan does not include new reduction in force targets, further staff attrition is expected as positions are relocated.

The agency’s reorganization plan is not just an organizational change in the name of shrinking the administrative state or reducing bureaucracy. The reorganization, replete with planned office closures and an explicit shrinking of agricultural research capacity, is poised to reshape the American food system, a driver of public health, environment, and economic outcomes across the country.

Why Agricultural R&D is a Crucial Investment

The federal government has historically played a significant role in improving the productivity of U.S. agriculture. By boosting yields and output, public agricultural research and development (R&D) has in turn reduced food prices, enhanced food security, and enabled farmers to produce more with less land and other inputs. Today, with farmers facing high input costs relative to returns, growing pest and disease pressures, and a rapidly shifting trade landscape, new innovations are needed to help producers face challenges.

Every dollar invested in public agricultural R&D has generated $20 in returns—a huge historic return on USDA’s already small research budget. This is especially true relative to other industries. The Department of Energy spends roughly 7 times more on R&D than the Department of Agriculture. When it comes to climate-focused funding in particular, the federal government spent 22 times more on clean energy innovation than R&D agencies spent on climate mitigation in agriculture.

Continued agricultural R&D investments are expected to generate significant economic returns on investments and contribute to improved climate resilience, food security, and regional and rural economic development outcomes. For example, doubling public agricultural R&D funding over the next decade would increase U.S. productivity by about 60% compared to a business-as-usual scenario, while also expanding crop and livestock output more than 40%, reducing prices by more than a third, and substantially cutting greenhouse gas emissions, particularly from avoided deforestation.

Despite the value for farmers and consumers alike, public investment in U.S. agricultural research from USDA, other federal agencies, and states declined significantly from $7.64 billion in 2002 to $5.16 billion in 2019—a nearly 30% reduction, adjusting for inflation. This decline is the leading contributor to a slowdown in agricultural productivity growth. The 2024 Global Agricultural Productivity Report found that U.S. agriculture has not been growing more productive, while India, for example, has a robust annual productivity growth rate of 1.7 percent.

Instead of doubling down to strengthen the nation’s agricultural research capacity and reverse this trend, the administration’s reorganization plan bets on consolidation as a path to efficiency.

Region-Specific Research is at Stake

Preceding USDA’s reorganization announcement, the Office of Management and Budget sent a memo advising all federal agencies to develop plans for programmatic reorganization and significant reductions in force. The memo emphasized several key principles to guide a government-wide reduction in force, including a reduced real property footprint. It is therefore no surprise that several branches of USDA that have vast networks of local and regional offices spanning the nation, including the Agricultural Research Service and Forest Service, would come under scrutiny.

The Agricultural Research Service (ARS) is USDA’s in-house research agency. At the start of 2025, there were 95 ARS laboratories and research units across 42 states employing 8,000 scientists and support staff. This vast network includes soil scientists improving crop water productivity in Texas, experts leading dairy forage systems research in Wisconsin, and plant breeders developing improved protein content in soybeans in North Carolina. On the surface, the real estate footprint of ARS could look inefficient. But, this interpretation fails to recognize the importance of region-specific research and the ability of researchers to deliver farmer-focused, regionally-relevant breakthroughs, exactly the type of service to USDA’s customers the Secretary claims as a goal in the reorganization plan.

The administration justified the overhaul by citing the need to locate agency functions closer to USDA customers. However, more than 90% of USDA’s employees already work outside the National Capital Region, including all but one ARS site. The ARS site slated for closure in the reorganization plan is located in Beltsville, Maryland, outside of Washington, DC.

Appearing before the Senate Agriculture Committee, Deputy Secretary of Agriculture Stephen Vaden assured Senators that only four research centers would be affected by USDA’s reorganization in addition to the closure of the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center.

USDA has yet to announce which four ARS sites will be affected and whether the research done at the ARS location in Beltsville will be relocated and continued, or cancelled entirely.

USDA’s reorganization comes as the agency implements a broader funding freeze on competitive research grants, further threatening the non-federal agricultural scientific research workforce. The administration’s decision to conduct an extended program-by-program review that significantly delayed research grant cycles impacts agricultural research programs at land grant universities across the country. ARS sites are often co-located with public Land Grant institutions, with both benefiting from shared resources and often partnering on research efforts. These delays and ongoing uncertainty threaten the economic returns that publicly funded research has consistently generated for both farmers and consumers.

Consolidation is Not Always a Solution for Efficiency

The Trump administration has often cited consolidation as a path to efficiency. But history shows that USDA reorganizations have weakened, not strengthened, the agency’s capacity. From the Obama administration’s 2012 “Blueprint for Better Services” to the 2019 Trump administration relocation of USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) and National Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIFA), past efforts framed as efficiency measures instead led to staff attrition, loss of institutional knowledge, and setbacks in core research and grantmaking functions. The reorganization now under consideration risks repeating those mistakes at a far greater scale.

For example, the 2019 relocation of ERS and NIFA to Kansas City led to significant staff attrition and a loss of institutional knowledge. This worsened productivity at all levels, a performance hit that took years to bounce back. In fact, it took USDA more than two years to recover from mass staff attrition and the agency is still facing challenges from the decision to relocate two of its major research facilities from Washington, DC. Two years after relocating, ERS and NIFA’s workforce size and productivity declined significantly. Many of the positions that were lost or left vacant were central to the agency’s functions. As a direct result, the relocation reduced the number of ERS reports and NIFA took longer to process scientific research grants. The Government Accountability Office found that USDA did not account for the cost of staff attrition that results from moving federal facilities and did not follow best practices for effective agency reforms and strategic human capital management. The 2019 relocation effort minimally involved USDA employees, Congress, and other key stakeholders. In addition, both agencies did not follow best practices related to strategic workforce planning, training, and development, which may have contributed to the time it took to recover to baseline staffing levels.

We’re seeing a similar scenario replay in real time with the reorganization plan that was announced in July, but at a much broader scale that can have severe impacts to U.S. agriculture. So far, USDA has not released a detailed reorganization plan or provided any economic or workforce analysis to evaluate how relocation and consolidation would affect its mission or the communities it serves. USDA’s decision to shutter the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, its flagship research site near Washington, D.C., has drawn criticism from Congress, farm groups, and scientists alike. The agency conceded it had no supporting analysis for the closure, even as the decision threatens to upend vital research programs and dismantle longstanding collaborations.

Unlike the Obama administration’s 2012 proposal to end a dozen ARS programs, which was a direct response to a significant 12% reduction in discretionary funding from Congress, the current reorganization proposal has been announced during a period of strong bipartisan support for agricultural research. Thanks to this support, USDA’s R&D funding has recently rebounded, with funding for ARS and other research agencies surpassing $3.6 billion in 2024, just shy of the funding levels in the early- and mid-2000s. The administration’s reorganization plan threatens to stall or reverse this progress, jeopardizing whether the agency will be able to administer research funding allocated by Congress. Willingness to push forward a reorganization with little regard for legal or procedural constraints or Congressional oversight will cause staff and mission capacity to bear the brunt of the fallout.

Policy Implications

Loss of Institutional Knowledge and Capacity

USDA has begun to grapple with the implications of an unprecedented loss of experienced personnel. This mass exodus spans critical agencies from the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and Farm Service Agency to research divisions like ARS, NIFA, and ERS. These losses undermine food safety, rural development, and science-based policymaking. Pressures on staff to take deferred resignation offers earlier this year culled some of the most seasoned and deeply knowledgeable staff. In a letter to Congress, union groups representing USDA employees outlined that “despite the importance of ARS research, 98 out of 167 food safety scientists have recently resigned”, leaving the future of food security research for all Americans at risk.

Reducing staff capacity also risks the agency’s ability to administer its slate of competitive grant programs that fund critical research. Even if Congress continues to fund research programs at existing discretionary spending levels, research funding will backslide if USDA lacks adequate staff to review applications and get funding out the door each year. Such delays could lead to rescission requests for unspent funds despite existing NIFA programs being regularly oversubscribed with applications from scientists at land-grant universities and other research institutions. The loss of experienced staff not only jeopardizes the continuity of ongoing agricultural R&D, but it also hobbles USDA’s capacity to pivot swiftly in crises like disease outbreaks, market shocks, or climate emergencies. Replacing this intellectual capital will be difficult, costly, and time-consuming, with long-lasting ramifications for program effectiveness, policy depth, and trust in USDA’s scientific and operational integrity.

Decline of U.S. Agricultural R&D Capacity

Sweeping freezes and cancellations of USDA research grants are dealing a severe blow to the non-federal agricultural R&D community, with entire programs suddenly paused or eliminated. The National Sustainable Agricultural Coalition estimates that across all programs, $6B of USDA grants have been frozen or terminated. These disruptions to extramural competitive research are compounded by the ongoing exodus of USDA’s most experienced in-house research staff, threatening to set back U.S. agricultural science for years. China already invests more heavily in agricultural R&D than the U.S., and these setbacks further erode America’s ability to compete on food security, climate resilience, and rural innovation. Unlike other scientific fields, agricultural research has direct and immediate end users. Farmers depend on improved cultivars, conservation practices, access to cheap energy, and pest management tools. When R&D pipelines stall, the consequences eventually ripple into the fields, orchards, and markets that sustain rural economies and national resilience. Agricultural research can have long lag times, making it even more dangerous to abandon investments in agricultural innovation today that will leave U.S. producers empty handed and less competitive in the years ahead.

Erosion of Trust and Stability in Rural Communities

Beyond the immediate impacts on research institutions, the sudden freezing and cancellation of USDA programs destabilize the very communities those programs are designed to serve. Farmers, rural co-ops, and community organizations build their planting, labor, and investment decisions around multi-year USDA commitments. When those commitments are abruptly halted, producers face stranded costs, disrupted harvest cycles, and foregone markets. Community-based organizations and local governments lose confidence in USDA as a reliable partner, undermining adoption of conservation practices, renewable energy, and local food initiatives. This breakdown in trust makes it harder to recruit farmers into new R&D pilots or climate-smart initiatives in the future, even if funding is later restored. The long-term result is a weakened feedback loop between federally funded science and its most critical end-users. This could lower the utility and on-farm adoption of tools, technologies and practices informed by future research. This weakens the economic return on taxpayer dollars dedicated to research projects. At worst, this broken feedback loop leaves rural economies more vulnerable to economic shocks.

Policy Recommendations

Congress holds the ultimate authority over federal appropriations and agency oversight, and thus has significant leverage to shape the future of USDA’s reorganization. How lawmakers exercise that authority will determine whether this reorganization strengthens or undermines the nation’s agricultural research and rural service infrastructure. Through targeted oversight, Congress can insist on transparency, protect against unlawful impoundments or relocations, and ensure continuity so that farmers and rural communities continue to benefit from the innovations generated by USDA’s research agencies. Options available to Congress include:

- Directing the USDA Office of Inspector General to assess USDA’s budget and legal authority for reorganization and relocation, ensuring taxpayer dollars are used lawfully and effectively.

- Requiring USDA to conduct an economic and workforce impact analysis with direct engagement of USDA staff to measure how reorganization affects agricultural research, rural economies, and service delivery.

- Calling for USDA to provide transparent justification for its decision to consolidate into five hubs, including criteria, alternatives considered, and implications for farmer access to research, extension services, and technical assistance.

- Requesting details on how USDA plans to retain staff expertise and capacity to operate existing grant programs at their current size, in accordance with funding appropriated by Congress, ensuring the continuity of vital agricultural research and services.

The proposed consolidation and reorganization of USDA illustrate both the risks and the possibilities ahead. Without careful oversight, these moves could erode research capacity, diminish workforce expertise, and disrupt vital services for farmers and rural communities. Yet we also know there are champions inside and outside government, across party lines, who recognize the value of agricultural R&D and its central role in national food security. With their leadership, there remains a pathway to repair what is broken, ensure transparency and accountability in reorganization efforts, and ultimately build an agricultural R&D infrastructure that delivers lasting benefits for all.

Position on the Environmental Protection Agency’s Proposal to Revoke the Endangerment Finding

Yesterday, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed revoking its 2009 “endangerment finding” that greenhouse gases pose a substantial threat to the public. The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) stands in strong opposition.

The science couldn’t be clearer: unchecked emissions of greenhouse gases are increasing the frequency and toll of disasters like flash flooding in Texas, catastrophic wildfires in Los Angeles, and stifling heat domes that repeatedly blanket huge swathes of the country. Revoking the endangerment finding would shove science aside in favor of special interests – and at the expense of American health and wellbeing.

“The Environmental Protection Agency claims that the endangerment finding led to ‘costly burdens’ on American families and businesses, when in reality it is the cost of failing to regulate climate pollution that will hit Americans the hardest,” said Dr. Hannah Safford, Associate Director of Climate and Environment at the Federation of American Scientists. “Climate change is expected to cost each American child born today half a million dollars over their lifetimes. Is that the legacy we want to leave our kids?”

The EPA’s proposal is the latest move by the Trump Administration to gut federal climate policy. This campaign runs counter to public opinion: 4 in 5 of all Americans, across party lines, want to see the government take stronger climate action. At the same time, potential revocation of the endangerment finding underscores the need for a durable new approach to climate policy that integrates innovative regulatory design, complementary policy packages, and attention to real-world implementation capacity. FAS and its partners are leading on this priority alongside state and local leaders.

“Despite the Trump Administration’s short-sighted and ideologically motivated actions, the clean energy transition has unstoppable momentum, and there is tremendous opportunity for innovation on how we design and deliver climate policies that are equitable, efficient, and effective,” added Dr. Safford. “The Trump Administration may be stepping back, but many others are stepping forward to create a world free from climate danger.”

Maintaining American Leadership through Early-Stage Research in Methane Removal

Methane is a potent gas with increasingly alarming effects on the climate, human health, agriculture, and the economy. Rapidly rising concentrations of atmospheric methane have contributed about a third of the global warming we’re experiencing today. Methane emissions also contribute to the formation of ground-level ozone, which causes an estimated 1 million premature deaths around the world annually and poses a significant threat to staple crops like wheat, soybeans, and rice. Overall, methane emissions cost the United States billions of dollars each year.

Most methane mitigation efforts to date have rightly focused on reducing methane emissions. However, the increasingly urgent impacts of methane create an increasingly urgent need to also explore options for methane removal. Methane removal is a new field exploring how methane, once in the atmosphere, could be broken down faster than with existing natural systems alone to help lower peak temperatures, and counteract some of the impact of increasing natural methane emissions. This field is currently in the “earliest stages of knowledge discovery”, meaning that there is a tremendous opportunity for the United States to establish its position as the unrivaled world leader in an emerging critical technology – a top goal of the second Trump Administration. Global interest in methane means that there is a largely untapped market for innovative methane-removal solutions. And investment in this field will also generate spillover knowledge discovery for associated fields, including atmospheric, materials, and biological sciences.

Congress and the Administration must move quickly to capitalize on this opportunity. Following the recommendations of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM)’s October 2024 report, the federal government should incorporate early-stage methane removal research into its energy and earth systems research programs. This can be achieved through a relatively small investment of $50–80 million annually, over an initial 3–5 year phase. This first phase would focus on building foundational knowledge that lays the groundwork for potential future movement into more targeted, tangible applications.

Challenge and Opportunity

Methane represents an important stability, security, and scientific frontier for the United States. We know that this gas is increasing the risk of severe weather, worsening air quality, harming American health, and reducing crop yields. Yet too much about methane remains poorly understood, including the cause(s) of its recent accelerating rise. A deeper understanding of methane could help scientists better address these impacts – including potentially through methane removal.

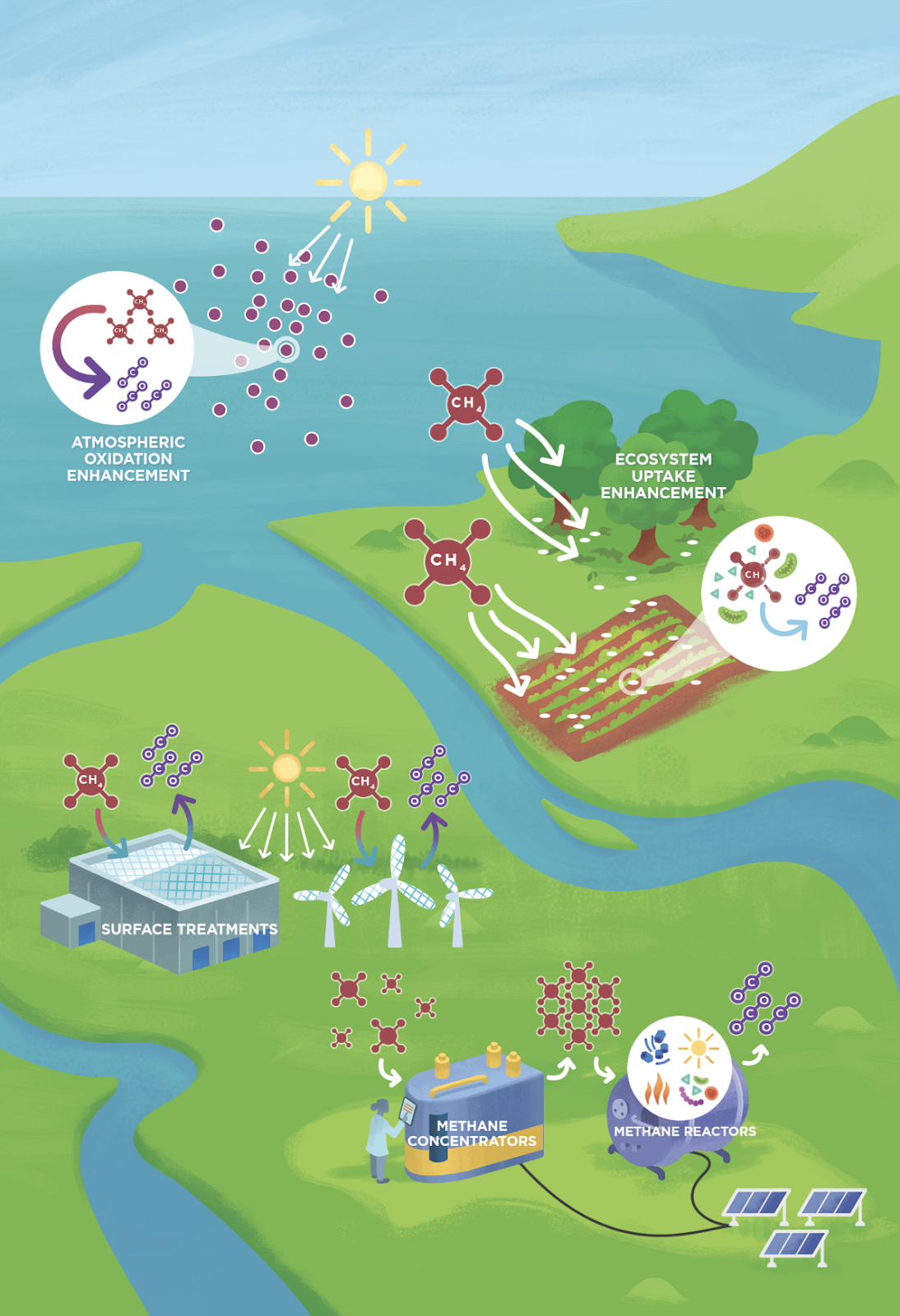

Methane removal is an early-stage research field primed for new American-led breakthroughs and discoveries. To date, four potential methane-removal technologies and one enabling technology have been identified. They are:

- Ecosystem uptake enhancement: Increasing microbes’ consumption of methane in soils and trees or getting plants to do so.

- Surface treatments: Applying special coatings that “eat” methane on panels, rooftops, or other surfaces.

- Atmospheric oxidation enhancement: Increasing atmospheric reactions conducive to methane breakdown.

- Methane reactors: Breaking down methane in closed reactors using catalysts, reactive gases, or microbes.

- Methane concentrators: A potentially enabling technology that would separate or enrich methane from other atmospheric components.

Figure 1. Atmospheric Methane Removal Technologies. (Source: National Academies Research Agenda)

Many of these proposed technologies have analogous traits to existing carbon dioxide removal methods and other interventions. However, much more research is needed to determine the net climate benefit, cost plausibility and social acceptability of all proposed methane removal approaches. The United States has positioned itself to lead on assessing and developing these technologies, such as through NASEM’s 2024 report and language included in the final FY24 appropriations package directing the Department of Energy to produce its own assessment of the field. The United States also has shown leadership with its civil society funding some of the earliest targeted research on methane removal.

But we risk ceding our leadership position – and a valuable opportunity to reap the benefits of being a first-mover on an emergent technology – without continued investment and momentum. Indeed, investing in methane removal research could help to improve our understanding of atmospheric chemistry and thus unlock novel discoveries in air quality improvement and new breakthrough materials for pollution management. Investing in methane removal, in short, would simultaneously improve environmental quality, unlock opportunities for entrepreneurship, and maintain America’s leadership in basic science and innovation. New research would also help the United States avoid possible technological surprises by competitors and other foreign governments, who otherwise could outpace the United States in their understanding of new systems and approaches and leave the country unprepared to assess and respond to deployment of methane removal elsewhere.

Plan of Action

The federal government should launch a five-year Methane Removal Initiative pursuant to the recommendations of the National Academies. A new five-year research initiative will allow the United States to evaluate and potentially develop important new tools and technologies to mitigate security risks arising from the dangerous accumulation of methane in the atmosphere while also helping to maintain U.S. global leadership in innovation. A well-coordinated, broad, cross-cutting federal government effort that fosters collaborations among agencies, research universities, national laboratories, industry, and philanthropy will enable the United States to lead science and technology improvements to meet these goals. To develop any new technologies on timescales most relevant for managing earth system risk, this foundational research should begin this year at an annual level of $50–$80 million per year. Research should last ideally five years and inform a more applied second-phase assessment recommended by the National Academies.

Consistent with the recommendations from the National Academies’ Atmospheric Methane Removal Research Agenda and early philanthropic seed funding for methane removal research, the Methane Removal Initiative would:

- Establish a national methane removal research and development program involving key science agencies, primarily the National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, with contributions from other agencies including the US Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Standards and Technology, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Department of Interior, and Environmental Protection Agency.

- Focus early investments in foundational research to advance U.S. interests and close knowledge gaps, specifically in the following areas:

- The “sinks” and sources of methane, including both ground-level and atmospheric sinks as well as human-driven and natural sources (40% of research budget),

- Methane removal technologies, as described below (30% of research budget); and

- Potential applications of methane removal, such as demonstration and deployment systems and their interaction with other climate response strategies (30% of research budget).

The goal of this research program is ultimately to assess the need for and viability of new methods that could break down methane already in the atmosphere faster than natural processes already do alone. This program would be funded through several appropriations subcommittees in Congress, most notably Energy & Water Development and Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies. Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Interior and Environment also have funding recommendations relevant to their subcommittees. As scrutiny grows on the federal government’s fiscal balance, it should be noted that the scale of proposed research funding for methane removal is relatively modest and that no funding has been allocated to this potentially critical area of research to date. Forgoing these investments could result in neglecting this area of innovation at a critical time where there is an opportunity for the United States to demonstrate leadership.

Conclusion

Emissions reductions remain the most cost-effective means of arresting the rise in atmospheric methane, and improvements in methane detection and leak mitigation will also help America increase its production efficiency by reducing losses, lowering costs, and improving global competitiveness. The National Academies confirms that methane removal will not replace mitigation on timescales relevant to limiting peak warming this century, but the world will still likely face “a substantial methane emissions gap between the trajectory of increasing methane emissions (including from anthropogenically amplified natural emissions) and technically available mitigation measures.” This creates a substantial security risk for the United States in the coming decades, especially given large uncertainties around the exact magnitude of heat-trapping emissions from natural systems. A modest annual investment of $50–80 million can pay much larger dividends in future years through new innovative advanced materials, improved atmospheric models, new pollution control methods, and by potentially enhancing security against these natural systems risks. The methane removal field is currently at a bottleneck: ideas for innovative research abound, but they remain resource-limited. The government has the opportunity to eliminate these bottlenecks to unleash prosperity and innovation as it has done for many other fields in the past. The intensifying rise of atmospheric methane presents the United States with a new grand challenge that has a clear path for action.

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas that plays an outsized role in near-term warming. Natural systems are an important source of this gas, and evidence indicates that these sources may be amplified in a warming world and emit even more. Even if we succeed in reducing anthropogenic emissions of methane, we “cannot ignore the possibility of accelerated methane release from natural systems, such as widespread permafrost thaw or release of methane hydrates from coastal systems in the Arctic.” Methane removal could potentially serve as a partial response to such methane-emitting natural feedback loops and tipping elements to reduce how much these systems further accelerate warming.

No. Aggressive emissions reductions—for all greenhouse gases, including methane—are the highest priority. Methane removal cannot be used in place of methane emissions reduction. It’s incredibly urgent and important that methane emissions be reduced to the greatest extent possible, and that further innovation to develop additional methane abatement approaches is accelerated. These have the important added benefit of improving American energy security and preventing waste.

More research is needed to determine the viability and safety of large-scale methane removal. The current state of knowledge indicates several approaches may have the potential to remove >10 Mt of methane per year (~0.8 Gt CO₂ equivalent over a 20 year period), but the research is too early to verify feasibility, safety, and effectiveness. Methane has certain characteristics that suggest that large-scale and cost-effective removal could be possible, including favorable energy dynamics in turning it into CO2 and the lack of a need for storage.

The volume of methane removal “needed” will depend on our overall emissions trajectory, atmospheric methane levels as influenced by anthropogenic emissions and anthropogenically amplified natural systems feedbacks, and target global temperatures. Some evidence indicates we may have already passed warming thresholds that trigger natural system feedbacks with increasing methane emissions. Depending on the ultimate extent of warming, permafrost methane release and enhanced methane emissions from wetland systems are estimated to potentially lead to ~40-200 Mt/yr of additional methane emissions and a further rise in global average temperatures (Zhang 2023, Kleinen 2021, Walter 2018, Turetsky 2020). Methane removal may prove to be the primary strategy to address these emissions.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, 43 times stronger than carbon dioxide molecule for molecule, with an atmospheric lifetime of roughly a decade (IPCC, calculation from Table 7.15). Methane removal permanently removes methane from the atmosphere by oxidizing or breaking down methane into carbon dioxide, water, and other byproducts, or if biological processes are used, into new biomass. These products and byproducts will remain cycling through their respective systems, but without the more potent warming impact of methane. The carbon dioxide that remains following oxidation will still cause warming, but this is no different than what happens to the carbon in methane through natural removal processes. Methane removal approaches accelerate this process of turning the more potent greenhouse gas methane into the less potent greenhouse gas carbon dioxide, permanently removing the methane to reduce warming.

The cost of methane removal will depend on the specific potential approach and further innovation, specific costs are not yet known at this stage. Some approaches have easier paths to cost plausibility, while others will require significant increases in catalytic, thermal or air processing efficiency to achieve cost plausibility. More research is needed to determine credible estimates, and innovation has the potential to significantly lower costs.

Greenhouse gases are not interchangeable. Methane removal cannot be used in place of carbon dioxide removal because it cannot address historical carbon dioxide emissions, manage long-term warming or counteract other effects (e.g., ocean acidification) that are results of humanity’s carbon dioxide emissions. Some methane removal approaches have characteristics that suggest that they may be able to get to scale quickly once developed and validated, should deployment be deemed appropriate, which could augment our near-term warming mitigation capacity on top of what carbon dioxide removal and emissions reductions offer.

Methane has a short atmospheric lifetime due to substantial methane sinks. The primary methane sink is atmospheric oxidation, from hydroxyl radicals (~90% of the total sink) and chlorine radicals (0-5% of the total sink). The rest is consumed by methane-oxidizing bacteria and archaea in soils (~5%). While understood at a high level, there is substantial uncertainty in the strength of the sinks and their dynamics.

Up until about 2000, the growth of methane was clearly driven by growing human-caused emissions from fossil fuels, agriculture, and waste. But starting in the mid-2000s, after a brief pause where global emissions were balanced by sinks, the level of methane in the atmosphere started growing again. At the same time, atmospheric measurements detected an isotopic signal that the new growth in methane may be from recent biological—as opposed to older fossil—origin. Multiple hypotheses exist for what the drivers might be, though the answer is almost certainly some combination of these. Hypotheses include changes in global food systems, growth of wetlands emissions as a result of the changing climate, a reduction in the rate of methane breakdown and/or the growth of fracking. Learn more in Spark’s blog post.

Methane has a significant warming effect for the 9-12 years that it remains in the atmosphere. Given how potent methane is, and how much is currently being emitted, even with a short atmospheric lifetime, methane is accumulating in the atmosphere and the overall warming impact of current and recent methane emissions is 0.5°C. Methane removal approaches may someday be able to bring methane-driven warming down faster than with natural sinks alone. The significant risk of ongoing substantial methane sources, such as natural methane emissions from permafrost and wetlands, would lead to further accumulation. Exploring options to remove atmospheric methane is one strategy to better manage this risk.

Research into all methane removal approaches is just beginning, and there is no known timeline for their development or guarantee that they will prove to be viable and safe.

Some methane removal and carbon dioxide removal approaches overlap. Some soil amendments may have an impact on both methane and carbon dioxide removal, and are currently being researched. Catalytic methane-oxidizing processes could be added to direct air capture (DAC) systems for carbon dioxide, but more innovation will be needed to make these systems sufficiently efficient to be feasible. If all planned DAC capacity also removed methane, it would make a meaningful difference, but still fall very short of the scale of methane removal that could be needed to address rising natural methane emissions, and additional approaches should be researched in parallel.

Methane emissions destruction refers to the oxidation of methane from higher-methane-concentration air streams from sources, for example air in dairy barns. There is technical overlap between some methane emissions destruction and methane removal approaches, but each area has its own set of constraints that will also lead to non-overlapping approaches, given different methane concentrations to treat, and different form-factor constraints.

Building a Comprehensive NEPA Database to Facilitate Innovation

The Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Innovation and Jobs Act are set to drive $300 billion in energy infrastructure investment by 2030. Without permitting reform, lengthy review processes threaten to make these federal investments one-third less effective at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. That’s why Congress has been grappling with reforming the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) for almost two years. Yet, despite the urgency to reform the law, there is a striking lack of available data on how NEPA actually works. Under these conditions, evidence-based policy making is simply impossible. With access to the right data and with thoughtful teaming, the next administration has a golden opportunity to create a roadmap for permitting software that maximizes the impact of federal investments.

Challenge and Opportunity

NEPA is a cornerstone of U.S. environmental law, requiring nearly all federally funded projects—like bridges, wildfire risk-reduction treatments, and wind farms—to undergo an environmental review. Despite its widespread impact, NEPA’s costs and benefits remain poorly understood. Although academics and the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) have conducted piecemeal studies using limited data, even the most basic data points, like the average duration of a NEPA analysis, remain elusive. Even the Government Accountability Office (GAO), when tasked with evaluating NEPA’s effectiveness in 2014, was unable to determine how many NEPA reviews are conducted annually, resulting in a report aptly titled “National Environmental Policy Act: Little Information Exists on NEPA Analyses.”

The lack of comprehensive data is not due to a lack of effort or awareness. In 2021, researchers at the University of Arizona launched NEPAccess, an AI-driven program aimed at aggregating publicly available NEPA data. While successful at scraping what data was accessible, the program could not create a comprehensive database because many NEPA documents are either not publicly available or too hard to access, namely Environmental Assessments (EAs) and Categorical Exclusions (CEs). The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) also built a language model to analyze NEPA documents but contained their analysis to the least common but most complex category of environmental reviews, Environmental Impact Statements (EISs).

Fortunately, much of the data needed to populate a more comprehensive NEPA database does exist. Unfortunately, it’s stored in a complex network of incompatible software systems, limiting both public access and interagency collaboration. Each agency responsible for conducting NEPA reviews operates its own unique NEPA software. Even the most advanced NEPA software, SOPA used by the Forest Service and ePlanning used by the Bureau of Land Management, do not automatically publish performance data.

Analyzing NEPA outcomes isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s an essential foundation for reform. Efforts to improve NEPA software have garnered bipartisan support from Congress. CEQ recently published a roadmap outlining important next steps to this end. In the report, CEQ explains that organized data would not only help guide development of better software but also foster broad efficiency in the NEPA process. In fact, CEQ even outlines the project components that would be most helpful to track (including unique ID numbers, level of review, document type, and project type).

Put simply, meshing this complex web of existing softwares into a tracking database would be nearly impossible (not to mention expensive). Luckily, advances in large language models, like the ones used by NEPAccess and PNNL, offer a simpler and more effective solution. With properly formatted files of all NEPA documents in one place, a small team of software engineers could harness PolicyAI’s existing program to build a comprehensive analysis dashboard.

Plan of Action

The greatest obstacles to building an AI-powered tracking dashboard are accessing the NEPA documents themselves and organizing their contents to enable meaningful analysis. Although the administration could address the availability of these documents by compelling agencies to release them, inconsistencies in how they’re written and stored would still pose a challenge. That means building a tracking board will require open, ongoing collaboration between technologists and agencies.

- Assemble a strike team: The administration should form a cross-disciplinary team to facilitate collaboration. This team should include CEQ; the Permitting Council; the agencies responsible for conducting the greatest number of NEPA reviews, including the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; technologists from 18F; and those behind the PolicyAI tool developed by PNNL. It should also decide where the software development team will be housed, likely either at CEQ or the Permitting Council.

- Establish submission guidelines: When handling exorbitant amounts of data, uniform formatting ensures quick analysis. The strike team should assess how each agency receives and processes NEPA documents and create standardized submission guidelines, including file format and where they should be sent.

- Mandate data submission: The administration should require all agencies to submit relevant NEPA data annually, adhering to the submission guidelines set by the strike team. This process should be streamlined to minimize the burden on agencies while maximizing the quality and completeness of the data; if possible, the software development team should pull data directly from the agency. Future modernization efforts should include building APIs to automate this process.

- Build the system: Using PolicyAI’s existing framework, the development team should create a language model to feed a publicly available, searchable database and dashboard that tracks vital metadata, including:

- The project components suggested in CEQ’s E-NEPA report, including unique ID numbers, level of review, document type, and project type

- Days spent producing an environmental review (if available; this information may need to be pulled from agency case management materials instead)

- Page count of each environmental review

- Lead and supporting agencies

- Project location (latitude/longitude and acres impacted, or GIS information if possible)

- Other laws enmeshed in the review, including the Endangered Species Act, the National Historic Preservation Act, and the National Forest Management Act

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, cost of producing the review

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, staff hours used to produce the review

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, jobs and revenue created by the project

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, carbon emissions mitigated by the project

Conclusion

The stakes are high. With billions of dollars in federal climate and infrastructure investments on the line, a sluggish and opaque permitting process threatens to undermine national efforts to cut emissions. By embracing cutting-edge technology and prioritizing transparency, the next administration can not only reshape our understanding of the NEPA process but bolster its efficiency too.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

It’s estimated that only 1% of NEPA analyses are Environmental Impact Statements (EISs), 5% are Environmental Assessments (EAs), and 94% are Categorical Exclusions (CEs). While EISs cover the most complex and contentious projects, using only analysis of EISs to understand the NEPA process paints an extremely narrow picture of the current system. In fact, focusing solely on EISs provides an incomplete and potentially misleading understanding of the true scope and effectiveness of NEPA reviews.

The vast majority of projects undergo either an EA or are afforded a CE, making these categories far more representative of the typical environmental review process under NEPA. EAs and CEs often address smaller projects, like routine infrastructure improvements, which are critical to the nation’s broader environmental and economic goals. Ignoring these reviews means disregarding a significant portion of federal environmental decision-making; as a result, policymakers, agency staff, and the public are left with an incomplete view of NEPA’s efficiency and impact.

The Supply-Side Tax Credit: A National Incentive to Reduce the Cost of Affordable Housing

Because affordable developers pay the same price for goods and services as market rate developers, the cost to build affordable housing continues to increase with market conditions, stunting projects and states’ attempt to meet their Regional Housing Needs Assessment goals. One way to address the cost of development is to incentivize manufacturers and consultants to reduce their upfront cost when working on, or supplying materials for, an affordable development. A supply-side tax credit (STC) could offer a tax incentive to material suppliers and professional service consultants that provide goods or services to affordable housing projects.

If consultants and manufacturers are willing to reduce their upfront cost in exchange for a dollar-for-dollar tax credit, the cost of developing affordable projects would significantly decrease. Since the amount of tax credits required for a project to be financially feasible is determined by the cost of construction, also referred to as eligible basis, the reduction in hard and soft costs realized through the STC would reduce the amount of low-income housing tax credits needed for each project. This would increase the number of projects that could receive a low-income housing tax credit allocation annually.

Allowing suppliers of affordable housing to claim a tax credit in their annual tax filings would reduce their corporate or individual tax liability, thereby immediately passing savings through to the affordable developer. The table applies a 30% Supply-Side Tax Credit to hard and soft costs of a recent project. In this scenario, the affordable developer will see $4.44 million in project savings.

When the affordable developer requests bids for services or construction of the project, notice will be provided in the Request for Proposals/Qualifications that if the manufacturer or consultant reduces their cost by 30%, they will receive a Supply Side Tax Credit Reservation when the project is awarded either 4% or 9% Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC). The reservation of the LIHTC will simultaneously secure the manufacturer and consultant’s STC until the following tax period.

The STC differs from the LIHTC in that it is not an equity investment in the project but rather a tax incentive for suppliers of affordable housing. The STC also differs in that LIHTCs are earned over a 15-year period, and the STC is earned in the tax year the tax credit reservation is made. This timing allows suppliers to realize the tax benefits as soon as possible since a large portion of consultant costs are incurred well before a tax credit allocation. Because this is a new tax credit, it will be independent of the federal per capita-based LIHTC credit cap. The STC will also reduce the amount of LIHTC credits needed to make a project feasible through a reduction in overall costs. Therefore, implementation of STC would increase the number of projects LIHTC could fund. Administration of this tax credit would fall under the state agency that currently administers the LIHTC program.

Because the STC reduces corporate or individual tax liability, efficacy of the program may be reduced should the allocation of credits exceed a manufacturer’s or consultant’s tax liability. Therefore, the reduction in tax liability may be structured as a 30% reduction, rather than a dollar-for-dollar reduction in tax liability.

State-level support for a Supply-Side Tax Credit may be found in advocacy organizations in the affordable housing arena, like the Non-Profit Housing Association of Northern California, California Housing Partnership, East Bay Housing Associations, California Coalition for Rural Housing, and others. This proposal could be made to the California State Treasurer’s Office, which administers both the 4% and 9% tax credit programs.

Federal support may be found in federal advocacy organizations like the Grounded Solutions Network, the National Housing Conference, and the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment. Political support may be found in the Senate Finance Committee, which proposed the Workforce Housing Tax Credit Act, also known as the Middle-Income Housing Tax Credit, to both houses of Congress to build more middle-income housing.

With the assistance of Congress in drafting and proposing the Supply Side Tax Credit to the Senate Finance Committee and working with the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee and the California Debt Limit Allocation Committee to draft and issue program guidelines for the administration of the credit, we may get closer to solving this crisis. To draft the legislation itself could cost an estimated $150,000 in legal and financial advisor fees and $25,000 for lobbying and advertisement. This $175,000 cost can be raised through a capital campaign to organizations like Enterprise Community Partners that works with nonprofits to push policy change, along with support from the California Community Foundation that provides grants for long-term systematic solutions to the housing crisis in Los Angeles, as well as the grants from the San Francisco Foundation, and the Local Initiative Support Corporation. All of these organizations have the capacity to grant such an award and interest in making affordable housing less costly. This $175,000 cost would be reimbursed on the first deal that utilizes the STC. Additionally, money would naturally be saved long-term by reducing the upfront cost to build and by freeing up additional Low Income Housing Tax Credits due to the reduced cost and thus reduced tax credits needed on each Supply-Side Tax Credit deal.

The STC offers a new way to help control the rising cost of building the affordable housing this nation desperately needs.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

Develop a Housing Production Dashboard to Aid Policymaking and Research

Anyone who wants to understand housing production and its barriers faces crucial information gaps. Legislators, planners, housing developers, researchers, advocates, and citizens alike struggle to track proposed and actual housing production in a community or across communities, understand why proposed units go unconstructed, or determine affordability levels of proposed or approved units. Absent this information, the efficacy of interventions, including zoning reforms, is purely speculative, potentially resulting in inefficient, ineffective, or inequitable policies.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Department of Commerce, and Department of Transportation should jointly develop and manage a data resource—a Housing Production Dashboard—to track housing production within and across states and local jurisdictions to inform policy and research and to ensure that public investments in affordable housing production and preservation are made with maximum efficiency.

There is broad consensus that addressing chronic housing undersupply requires governments to ease constraints on housing production through zoning, finance, and other reforms. Our highly localized and decentralized land-use permitting system, the uniqueness of each local code and processes, and the idiosyncratic nature of local permitting administration obscures this information. Even as states and cities have adopted reforms such as allowing multiple units on single-family residential lots, there is little indication that single-family zoning caused unaffordable housing or that amending it will effectively address the problem.

No federal or state rule requires, and few agencies have developed, methods to track housing production despite this information’s relevance to fair and affordable housing, economic development, and transportation agencies. The few existing resources include the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis’s Housing Indicators website and California’s Statewide Housing Plan Dashboard.

Recommendation

To make housing production data generally available to government agencies, policymakers, researchers, and citizens, we recommend the following:

- The Departments of Housing and Urban Development, Commerce, and Transportation should jointly create and manage an online Housing Production Dashboard with tabular and map displays.

- Data delivery should be a condition of each local government’s receipt of federal housing, economic development, or transportation grants.

- Annualized data submittals, made by local government staff through an online portal, should include the number of housing units proposed, approved, permitted, and completed in the locality, and for units in each category, the type(s) of housing (i.e., whether single-family, two-family, three-family, four-family, or multi-family), affordability levels, and time elapsed between initial application and approval, along with the reason(s) why proposed housing units were not ultimately permitted.

This data resource will facilitate affordable housing production by (1) enabling policymakers and researchers to compare jurisdictions’ regulations and processes, and the reasons housing units go unconstructed, to identify causes of underproduction; (2) substantiating fact-based development decisions by local and state policymakers and reducing the power of anti-development-motivated reasoning; (3) empowering advocates and citizens to apply political and legal pressure on officials that fail to address housing needs or concentrate affordable housing in low-opportunity areas; and (4) informing real estate industry and major employer investment and location decisions prioritizing the most advantageous communities in which to locate and build more housing.

The federal government has a precedent and expertise in providing this type of data through HUD’s CHAS and AFFH Data and Mapping tool, as well as numerous Census products. Federal agencies are best-positioned to incentivize data delivery for the Dashboard and ensure the provision of unbiased factual information. Academic institutions and advocacy nonprofits could partner in the product’s development through a federal request for proposals. In summary, the Dashboard presents an opportunity for more informed policymaking, better economic development, and a powerful public information resource, with particular benefit for small and budget-constrained localities, advocates, and builders without the resources to collect and analyze the data on their own.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

Exempt Affordable Housing from Private Activity Bond Volume Cap

Tax-exempt Private Activity Bonds (PABs) are one of the primary financial tools to build and preserve affordable housing as they generate as-of-right Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC). However, the federal cap on those bonds creates a significant barrier to expanding overall affordable housing supply. By exempting affordable housing from the state volume cap, we can build more housing in states that are fully utilizing their volume cap.

The Housing Shortage Drives Up the Cost of Rental Housing

The United States faces a severe housing affordability crisis due to a shortage in housing supply that has been exacerbated by the pandemic. This shortage places pressure on households across the housing market but disproportionately impacts low-income households. The National Low

Income Housing Coalition found a shortage of over eight million homes affordable to very low-income households, those at or below 50% of the area median income (AMI). In New York State, this shortage is over 712,000 homes, contributing to soaring rents and a homelessness emergency. A renter in New York State needs to make over $40 per hour to afford a two-bedroom apartment at fair market rent as determined by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In New York City and the surrounding suburbs, they would need to make over $47 per hour.

In a growing number of states, low-income renters are being priced out of the market with few housing options, forced to pay a large portion of their income towards housing costs and/or living in substandard housing. As renters compete for limited housing options, rent prices increase as a result of this demand.

Tax-Exempt Private Activity Bonds Fuel Affordable Housing Production and the Economy

LIHTC is the single largest and most significant tool to finance affordable housing and often works with tax-exempt PABs. Tax-exempt PABs are state and local bonds for certain “qualified private activities” that exempt the interest earned by holders from federal income taxes. When they are used to finance at least 50% of an affordable rental housing project – a requirement referred to as the “50% test” – they come with as-of-right LIHTC. This provides equity for the development and preservation of affordable housing for low-income households. These federal tax credits leverage additional project funding, including a commercial mortgage, and often other state or local subsidies. At marginal expense to the federal government, PABs boost our country’s housing stock while also creating thousands of jobs and generating new tax revenue and billions in economic spending – in the process shortening economic crises and reducing their severity.

LIHTC generated by PABs help finance most new low-income housing and are critical to meeting affordable housing supply needs. They produce affordable housing that serves incomes from 30 to 80% of AMI, with all LIHTC units in a development averaging at 60% AMI. Since its creation in 1986, the program overall has developed or preserved almost four million homes, generated $257 billion in tax revenue and over $716 billion in wages and business income.

Volume Cap Is a Financing Barrier to Expanding Affordable Housing Supply

Unfortunately, PABS are a finite resource, artificially limited by the federal “volume cap,” which limits the number of tax-exempt private activity bonds each state can issue. The volume cap was imposed as part of a larger effort to restrict the supply and demand for PABs through the Tax Reform Act of 1986. These restrictions were primarily intended to address concerns around cost and tax equity.

Every year, a new cap is allocated to each state based on population using a formula set by Congress. New volume cap that is not used by the end of the year may be carried forward for three years. New York already uses all its cap on affordable housing, financing the creation or preservation of about 10,000 units of affordable housing annually. Demand for additional volume cap is great, outstripping supply. As a result, some shovel-ready projects must wait three or more years before receiving financing, a significant delay that deters affordable housing development.

Volume cap allocation has not kept pace with the growing demand for affordable housing, increasing just 25% over the past decade, even as the nation produced 5.5 million fewer homes in the last 20 years than it did in the previous 20. Meanwhile, construction costs have skyrocketed. The cost of building materials increased over 20% in just one year in 2022, and developers have seen insurance rates double and triple over the past five years.

While PABs have several uses, most recent analysis shows 88% of issuances in 2020 went to multi- and single-family housing, continuing an upward trend of almost a decade, most of which is attributed to the increased demand for affordable rental housing. Nationally, the total amount of multifamily bonds issuances nearly doubled in only a few years from $7.2 billion in 2017 to over $13 billion in 2020. The number of apartments expected to be built from PABs increased by almost 20% from 2019 to 2020.

Further, as communities across the country face housing supply shortages, more states are reaching their maximum allowable PAB issuance. In 2019 and 2020, states like Maine, North Carolina, South Carolina, Utah, and Montana issued record levels of PABs for housing. One in three states have reached their volume cap in recent years, including California, Georgia, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nebraska, New York, New Mexico, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, Texas, Tennessee, Utah, Washington, and Washington DC. Further, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) created two additional uses for PABs – broadband projects and carbon capture facilities – that could compete with housing for usage.

Volume Cap Exemptions Help Achieve the Public Good

There have been exceptions to state volume cap for 17 activities that contribute to the public good. These exceptions allow localities to build critical infrastructure without taking tax-exempt bonds away from other purposes. Congress has structured these exceptions in multiple ways. For example:

- Large public infrastructure such as airports, docks and wharves are exempt from volume cap.

- To address mounting capital needs for school construction and repair, Congress established a separate cap for financing some public educational facilities.

- The 2004 American Jobs Creation Act authorized $2 billion in tax-exempt bonds not subject to volume cap for qualified green building projects.

- Congress authorized $15 billion in tax-exempt bonds not subject to volume cap for highway and surface freight transfer facilities to address challenges in our transportation systems.

- For three uses, only 25% of bonds contribute to the cap. This includes high-speed intercity rail facilities, private projects to expand broadband access to underserved areas and facilities that capture carbon dioxide from the air.

Legislative Recommendations

Given the scale and urgency of the housing affordability crisis and the precedent for volume cap exemptions to address public priorities, we recommend that Congress enact legislation to exempt the development and preservation of multifamily rental housing affordable to low income-households from state volume cap.

There is political will to address the supply shortage. Recent increases in the HUD budget are helpful, but a significant HUD expansion to address our supply shortage will likely not gain congressional support in the immediate future, and the discretionary budget is constrained by the debt ceiling agreement.

We believe a tax-side solution is possible. LIHTC has enjoyed bipartisan support and legislation to meaningfully expand it, the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act (AHCIA), has bipartisan co-sponsors in both the House and Senate. There are several tax side proposals to allow more efficient uses of PABs that would produce meaningful increases in supply. The SAVE Act would create an exception to volume cap for the preservation, improvement, or replacement of federally assisted buildings to aid public and other HUD-assisted housing. The “50% test” unnecessarily limits volume cap as projects often have to allocate more bonds than are needed to finance the project to meet this requirement. The AHCIA would decrease the percentage of bond financing required to generate LIHTC from 50% to 25%, freeing up volume cap for states. However, exempting affordable housing from volume caps would address the underlying issue and have the greatest impact in this housing emergency.

There is also opportunity to provide volume cap relief through tax extenders or “must pass” bills that maintain government funding. Tax changes are often attached to broader bills. For example, we saw changes to LIHTC in the 2015 Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act, the 2018 omnibus spending bill, and the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021.

Even though LIHTC expansion has bipartisan support, the cost to the federal government from increased use of tax credits is a challenge. To limit or offset the costs of the tax credit (which is quantified by a reduction in future tax revenue, not direct federal spending), there are two options: (1) limit the exemption for a 10-year period, or (2) tie the exemption to revenue-generating reforms that are proven to add to the tax base, such as requiring state or local action on removing zoning barriers to access the state volume cap exemption for affordable housing. There has been no analysis on the cost of a complete exemption from volume cap, but AHCIA provisions to reduce the 50% test and expand LIHTC included in an early version of Build Back Better were estimated to cost about $12.7 billion in reduced revenue over 10 years. That investment, a small percentage of the $1.75 trillion proposal, could have housed 1.9 million low-income people while generating more than 1.2 million jobs, $137 billion in wages and business income, and more than $47 billion in tax revenue.

The housing shortage is an emergency affecting the lives of millions of Americans and the stability of our communities. Affordable housing is a public good, and the federal government has an obligation to respond to the needs of millions of low-income Americans. Adding affordable housing to the list of PAB uses exempt from volume cap would allow localities to build and preserve more desperately needed affordable housing.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

Increase Dedicated Resources for the National Housing Trust Fund

The United States faces a shortage of 7.3 million rental homes affordable and available to extremely low income (ELI) renters—those making at or below 30% of area median income (AMI). The private market does not build and operate housing affordable to renters in this income bracket on its own. Subsidies are necessary for landlords to charge rents that these households can afford.

The National Housing Trust Fund (HTF) is targeted to increase the supply of ELI rental homes. Ninety percent of HTF dollars must be used for the production, preservation, rehabilitation, or operation of affordable rental housing, and at least 75% of these dollars must support housing that is affordable to ELI renters. By contrast, the nation’s largest housing production program—the Low Income Housing Tax Credit—primarily serves renters at 50-60% AMI.

The HTF is currently funded with a small annual fee (0.042%) on Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae activity. States received their first HTF allocations in 2016, and approximately $3 billion has been allocated to date. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) administers the HTF as a block grant to housing finance agencies in all 50 states and U.S. territories, which create state-level Allocation Plans to determine how HTF dollars are awarded. HUD’s formula for distributing HTF dollars is based on (1) the number of renters making at or below 50% of AMI who are severely cost-burdened, meaning that they pay more than half their income on housing costs, and (2) the shortage of rental homes affordable and available to households making at or below 50% of AMI, with extra weight given to ELI households.

To increase the supply of affordable homes, Congress should make greater investments in the HTF. Expanding the supply of homes affordable to ELI renters will also address the overall housing shortage. If millions of cost-burdened ELI renters could move into subsidized homes, more market-rate housing would become available to higher-income renters.

Recommendations

To avoid competition with other programs in HUD’s annual budget, the HTF is intended to be funded outside of the annual appropriations process. The Build Back Better package that passed the House of Representatives in 2021 included $15 billion for the HTF, but this provision was stripped out of the slimmed-down Inflation Reduction Act that Congress ultimately enacted.

As a new source of revenue, Congress should reform the mortgage interest deduction (MID) to make second homes ineligible and invest the equivalent savings in tax expenditures into the HTF. While Congress reformed the MID in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, this legislation ignored years of bipartisan tax reform proposals that proposed to eliminate the MID for second homes. The proposal would face pushback from second homeowners, but research shows that it is politically popular and bipartisan: a 2012 Quinnipiac poll found that 55% of Democrats, 55% of Republicans, and 58% of independents supported this reform. Elimination of the MID for second homes could win cross-cutting support from deficit hawks seeking to cut back federal spending and progressives who favor federal support for people with the greatest needs.

Conclusion

On its own, the savings from eliminating the MID for second homes will not enable the HTF to entirely close the gap between housing supply and housing needs of the lowest-income renters. However, a substantial boost in resources would enable the HTF to make a greater dent in the housing shortage.

More widespread impact would also make the HTF a more visible federal program, increase its constituency of supporters, and create the political will for even more dedicated funds in the future.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

America Needs a National Housing Loss Rate

The need for a national housing loss rate

Each year, an estimated 10 to 20 million Americans lose their homes through eviction and mortgage foreclosure, tax sales, eminent domain, post-disaster displacement, and other less-studied forms of housing loss. These destabilizing events lead to homelessness, job loss, adverse health impacts, and downward economic mobility. And yet, America neither tracks housing loss nor holds politicians and decision-makers accountable for keeping it low. There is no national database of evictions or foreclosures, and research from New America found that one in three U.S. counties have no available annual eviction figures. Without a clear picture of housing loss across the country, it is nearly impossible to pass data-driven policies that keep people housed.

If the United States wants to get serious about stemming housing loss, then it should establish a national housing loss rate to stand alongside the national unemployment rate as a key indicator of social and economic well-being. The creation of a housing loss rate—a metric of how many people lose their homes involuntarily over a given period of time, and why—would help drive accountability and action among policymakers and improve resource allocation, regulation, and housing supply interventions.

Recommendations

We envision working on two parallel, mutually reinforcing tracks to establish home loss as a regularly tracked indicator, akin to the unemployment rate. The first track would employ a survey-based approach to establish a national housing loss rate, while the second, longer-term effort would build local infrastructure to collect and analyze data on actual incidences of housing loss.

Congressional Action

Congress should direct one of the lead federal housing agencies — most likely the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), or the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) — in consultation with the others to produce a feasibility study of developing and deploying a nationally representative survey to measure housing loss. The feasibility study should assess the most promising data collection strategies, the body responsible for implementing this effort (and whether this effort should be hosted inside or outside of government), and methodological questions such as the desired frequency, geographic coverage, and scope of the survey.

Executive Action

Concurrently, HUD, FHFA, the CFPB and the Census Bureau should use their existing authority to assess the feasibility of including housing loss questions or modules into surveys over which they have jurisdiction. Surveys identified by experts as possible entry points include the Census Pulse Survey, the American Community Survey, the American Survey of Mortgage Borrowers, and the American Housing Survey. Where the insertion of questions is feasible, HUD and Census should work with housing experts to develop and pilot proposed questions.

The Domestic Policy Council (DPC) should convene federal housing agencies to establish a comprehensive housing loss data collection, storage, and sharing strategy (including a plan for free, public access to the data in a way that also protects privacy) in consultation with housing advocates and academics. An interagency process to establish a national housing loss rate would be the strongest lever to achieve meaningful executive action.

Finally, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) should incorporate housing loss into its Life Experiences projects. The Customer Experience Executive Order, enacted in 2021, requires OMB to work with the DPC and the National Economic Council to study salient “life experiences” during which Americans interact with government services, in an effort to improve government efficiency. OMB should explore whether better tracking of housing loss could be incorporated into one of the existing projects—it is most relevant to facing a financial shock and recovering from a disaster—or whether housing loss could be the subject of its own life experience project.

Conclusion

Developing a national housing loss rate will take time and resources, and most likely will require congressional action and funding. A survey effort would likely need a time horizon of at least five years, and collecting and understanding actual incidences of housing loss will take significantly more time. However, as with the U.S. unemployment rate, which took decades to establish, the necessity of such a metric justifies the effort. A housing loss metric, if rigorous, regularly collected, and available at the national, state, and local level, would have profound impacts on our understanding of the causes and consequences of home loss and improve our ability to develop policies and programs that keep people more securely housed.

This idea of merit originated from our Housing Ideas Challenge, in partnership with Learning Collider, National Zoning Atlas, and Cornell’s Legal Constructs Lab. Find additional ideas to address the housing shortage here.

Why Creating an FHA/VA Mortgage Program for Developers Is a Good Idea

Lack of affordable mortgage programs for small businesses and developers contributes to the housing shortage in the United States. Primarily, commercial lenders guarantee and fund mortgages for small businesses and developers. These loans, known as investor and commercial mortgages, are very restrictive, resulting in only small pools of qualified applicants. Creating a federally guaranteed investor mortgage combined with an optional construction loan will assemble a larger base of qualified borrowers financially positioned to purchase and build more housing inventory.

Forming a federally backed investor mortgage and construction loan program does not require a large government expenditure initially. It only needs the full faith and promise of the United States government as a guarantee. Commercial banks could qualify the applicants and issue loans by utilizing existing systems servicing Fair Housing Authority (FHA) and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mortgage programs. The proposed program would be administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the VA, bypassing the need to create a new federal agency.

Creating such a program, however, would require legislative authorization from Congress as it would expand the federal government’s role from guaranteeing primary residential mortgages.

This proposed program would feature:

- No primary occupancy requirements

- 8% down payment

- 5% down payment for honorably discharged veterans

- Honorably discharged veterans allowed to withdraw earned government retirement funds tax free for downpayment

- 750+ credit scores of applicants

- Maximum loan limit of $1.5 million

- Interest rates lower than market available mortgages

- 30-year monthly amortization rates and payment terms

- Mortgage insurance requirements

- Optional construction loan for 80% of the appraised constructed or renovated value combined with the mortgage

- Full borrower recourse

- One loan at a time, previous loans must be paid

- Housing properties only

- Multiple parcels allowed

- Borrower required financial reserves

- No prepayment penalty