National Energy Storage Initiative

The next administration should establish a national initiative built around ambitious goals to accelerate development and deployment of dramatically improved energy-storage technologies. Developing such technologies would help establish a strategic new domestic manufacturing sector. Deploying such technologies would expand the range of low-carbon pathways available to fight climate change—especially those relying on variable renewable energy resources, like wind and solar power. Deploying such technologies would also improve the performance of smartphones, drones, and other vital electronic tools of the 21st century.

Challenge and Opportunity

Electricity systems, no matter how big or small, must instantaneously balance supply and demand, generation and load—or suffer blackouts. This imperative has long motivated scientists and technologists to seek the holy grail of affordable, reliable, durable, and safe energy storage. Yet, despite many decades of efforts, batteries remain expensive, fickle, short-lived, and dangerous for many applications. Other forms of energy storage, like thermal and compressed-air storage, suffer from major drawbacks as well.

Radically improved energy-storage technologies would help the nation and the world solve some of their most pressing problems. Most urgently, improved energy storage would expand the range of low-carbon pathways to fight climate change and reduce dependence on fossil fuels by allowing the electricity grid to accommodate higher levels of renewable energy. Improved energy storage would allow electric vehicles (EVs) to better meet drivers’ expectations for value and performance, thereby speeding up EV adoption and further helping to address the climate challenge. Better batteries would also let people stop worrying about whether their electronic devices are charged, improving security and strengthening the economy in a world where these and other connected devices are ubiquitous.

Given the importance and magnitude of these opportunities, energy storage has become a critical industry of the future—one that nations around the world seek to capture. China and the European Union, for instance, are making significant strategic investments to build domestic capabilities for development and manufacturing of energy storage technologies. These and other international competitors are challenging the U.S. energy innovation ecosystem—our research universities, national laboratories, start-up companies, and established technology firms to invent, commercialize, and scale-up next-generation energy-storage technologies.

Opportunities by sector

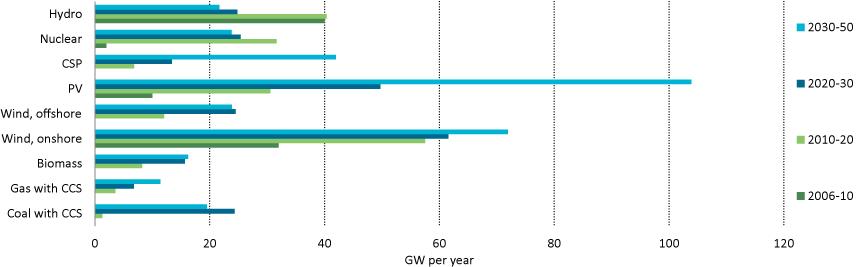

Electric power

The rapidly dropping cost of wind and solar power has opened major pathways to decarbonize electricity systems. But these power generation technologies are variable: that is, their output fluctuates by the hour, day, and season. As the renewable share of generation rises on a grid, such fluctuations make balancing supply and demand increasingly difficult, threatening brownouts and blackouts. Grid-scale energy storage has the potential to address this challenge. Although one energy-storage technology (lithium-ion batteries) has been improved to the point that it has begun to make a significant impact on the grid, major gaps remain. Fully solving the grid-storage problem requires technologies that are much cheaper and last much longer than current systems. Grid-storage technologies must be able to hold enough electricity to power a grid for a week or more at a cost of just a few cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh), while operating only a few times each year.

Transportation

Lithium-ion batteries are also kick-starting the electrification of transportation. Their declining cost is one of the key factors helping to bring EVs into the mainstream. EVs are cleaner than gasoline-powered cars if they are charged on low-carbon electricity grids. EVs are also easier to maintain and cheaper to operate. However, the ultimate triumph of EVs in the auto market is far from assured. Batteries that are safer, rely on more abundant materials, allow vehicles to go 500 miles or more on a charge, last for at least a decade, and are easily recharged and recycled would make the success of EVs more likely, with huge payoffs for the global climate.

Electronics

The suite of technologies sometimes lumped together as the “fourth industrial revolution” is another broad domain that would benefit from advances in energy storage. Robots, drones, sensors, and smartphones—and the systems by which they process and exchange information—have become essential tools in modern society.

Most of these electronics are more useful when they can operate without having to maintain a constant connection to the grid. Although batteries are becoming lighter and more efficient, the demands being placed on them are also rising, straining the limits of lithium-ion technology. An order-of-magnitude leap in the energy density of batteries— the amount of electricity stored in a given mass or volume—would unlock a diverse array of valuable new applications for a wide range of electronic devices. For instance, drones, whether they are being used by combat forces, farmers, or utility crews, would be able to stay aloft for days and carry more sophisticated payloads, such as weapons or sensors.

Domestic manufacturing

Paradigm-shifting improvements in energy storage technologies would also create opportunities to build domestic manufacturing capacity in a growing industry of the future. The supply chain for making lithium-ion batteries migrated to East Asia years ago. The largest battery factory for EVs in the United States, Tesla’s “giga-factory” in Reno, NV, is run by a joint venture with the Japanese-headquartered firm Panasonic. Tesla has been unable to fully master the finicky methods used to make battery cells. Other U.S.- based EV assembly plants rely on Asian-headquartered battery contractors as well.

Nonetheless, the United States continues to generate new energy storage technologies, including some that could supplant the current generation of lithium-ion batteries. For example, Sila Nanotechnologies, founded in 2011 and based in the San Francisco Bay Area, raised $215 million in 2019 to scale up its manufacturing activity. A half-dozen other U.S.-based battery start-ups have also raised large funding rounds in the past year. Investors include not only venture-capital firms, but also big companies based in Europe and Asia as well as North America. It remains to be seen where the battery supply chain of the future will be located.

Plan of Action

The next administration, building on the Department of Energy’s (DOE) recently announced “Energy Storage Grand Challenge,” should establish a National Energy Storage Initiative (NESI) built around ambitious goals to accelerate development and deployment of dramatically improved energy-storage technologies. These goals should include widespread adoption of:

- Grid-scale systems that can provide at least 500 megawatts (MW) of power for a week at a cost of three cents per kWh or less.

- Vehicle-scale energy-storage systems with performance, safety, and cost characteristics as good as or better than internal-combustion systems (including lifespan and recharging speed).

- Batteries for small devices exhibiting energy density an order of magnitude greater than current lithium-ion batteries.

The NESI should also seek to achieve economic and international goals such as:

- A positive international trade balance in energy-storage technologies and components.

- Global adoption of energy-storage technologies invented and commercialized in the United States across major application domains.

The NESI will require deep collaboration among key federal agencies and with the private sector, academia, and states and localities. This initiative would galvanize the still-thriving energy-storage science and technology community in the United States, spurring the development of better energy-storage technologies and ensuring that the next generation of storage devices are built here. The case for the NESI is two-fold. First, expanded research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) funding is needed to address market failures in the energy-storage domain. Expanded funding would enable scientific and mission agencies to pursue a diverse array of promising opportunities that have gone un- or under-explored. The result would be new energy-storage materials and concepts, breaking through barriers that have limited current technologies. Second, federal resources and leadership—as well as deep engagement with the private industrial and financial sectors and with key states and localities—are crucial for domestic scale-up and manufacturing made possible by this expanded RD&D portfolio. International competition surrounding energy storage is already fierce. China, in particular, has made no secret of its plan to dominate the global battery and EV industries. The United States must assert leadership on energy storage or risk being left behind.

Implementation

The NESI should include four key components: (1) White House leadership and coordination, (2) a federal RD&D budget commitment, (3) increased agency participation and use of an array of policy tools, and (4) mobilization of non-federal actors to undertake aligned actions.

White House leadership and coordination

An Executive Order (EO) from the White House, implemented by the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), would be the foundational action to launch the NESI. White House leadership and attention would catalyze implementing agencies to identify lead units and staff members for the interagency initiative and to undertake internal coordination among their component units (e.g., the science and applied energy offices within DOE). OSTP, NSTC, and agency staff would spearhead the initiative, driving its progress throughout the executive branch and mobilizing support in Congress, industry, science, and the public.

Budget

Delivering on the aforementioned goals would require, at a minimum, tripling current spending on energy storage RD&D programs over five years. The most comprehensive estimate of federal RD&D spending on energy storage comes from a 2015 OMB interagency “crosscut”: $300 million. Increasing spending to $900 million or more per year would allow participating agencies to take the following actions:

- Accelerate fundamental research on promising energy-storage materials and systems.

- Create and expand centers of excellence in RD&D on energy storage at universities and government laboratories.

- Build academic-government-industry partnerships to create energy-storage prototypes and pilot projects.

- Conduct large-scale energy-storage demonstration projects in collaboration with end users, such as urban and rural electricity systems and military bases.

- Establish regional manufacturing innovation centers that facilitate technology development, worker training, and small- and medium-enterprise (SME) engagement related to energy storage

Increased agency participation and use of other policy tools

In addition to DOE, the Departments of Agriculture (USDA), Commerce (DOC), Defense (DOD), Health and Human Services (HHS), Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and Transportation (DOT) as well as the National Science Foundation (NSF) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) should be mobilized to accelerate innovation in energy storage. DOC, DOD, HHS, and NSF should collaborate with DOE in expanding the energy storage RD&D enterprise. The other agencies, along with DOE and DOD, should use policy tools such as procurement, regulation, and investment support (e.g., loan guarantees) to help “pull” nascent energy-storage technologies into markets and to assist in establishing domestic production capacity. Tax incentives, legislated by Congress and administered by executive agencies, may also be helpful to accelerate market growth and drive down costs for particular technologies.

Mobilization of non-federal actors

Academia and industry are critical to the success of energy-storage RD&D, manufacturing, and adoption. The vast scope of energy-storage applications amplifies the importance of engaging with a wide variety of end-user industries—especially power-system vendors, utilities, electronics manufacturers, and automakers—as well as producers of storage technology. States and localities, many of which have announced ambitious goals for grid-scale storage, should also be incorporated into the NESI. A few states could house federally supported manufacturing and innovation “clusters” for energy-storage solutions. All states could accelerate adoption of improved energystorage technologies by fostering receptive markets: for instance, by reforming electricity regulation.

Precedents

The proposed NESI is similar to successful efforts such as the Clinton administration’s nanotechnology initiative and the Obama administration’s advanced manufacturing initiative. Such initiatives mobilize and coordinate multiple agencies in pursuit of technological capabilities that will contribute significantly to a set of broadly agreed national goals. Success depends on strong presidential commitment at the start and cultivation of stakeholders across partisan, regional, and sectoral lines over time. Effective technology initiatives have major on-the-ground impacts and ultimately become self-sustaining. Two keys to success are (1) White House leadership and attention to foster interagency cooperation, and (2) increased agency budgets to limit resistance from incumbent programs.

Federal funding for energy-storage science and technology has a long track record, particularly with regard to basic research. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) expanded federal energy-storage funding considerably in the 2010s. ARRA funding supported establishment of the Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy (ARPA-E), which has become a major source of funding for applied research and prototype development in energy storage. ARRA funding also supported the Joint Center for Energy Storage Research (JCESR) at Argonne National Laboratory; a collaborative demonstration program within DOE’s Office of Electricity that worked with utilities, states, and local governments; and loan guarantees for battery manufacturing and grid-scale storage projects.

Many of these investments have paid off handsomely. For instance, an evaluation by the National Academies found that ARPA-E’s funding of energy-storage technology has been “highly productive with respect to accelerating commercialization” and led to the formation of at least six new companies in the field. JCESR was renewed for an additional five years in 2018. However, the demonstration and manufacturing elements of the ARRA-funded push were not sustained, primarily due to ideological objections by the Congressional majority that came in after the 2010 midterm elections.

The Department of Energy announced an Energy Storage Grand Challenge on January 8, 2020. This initiative is a welcome step toward the broader initiative outlined in this paper. It seeks ambitious advances in technology, rapid commercialization, and the creation of a domestic manufacturing supply chain. But it does not extend beyond DOE, and whether it will be implemented with the appropriate resources and presidential support is uncertain.

International context

Many countries have made energy storage a priority. The European Union has embarked on a multi-billion-dollar battery initiative that led to the establishment of Northvolt, a European-owned battery cell manufacturing start-up. Volkswagen bought 20% of Northvolt and is working with it to build a second cell factory. Energy storage and EVs are among the sectors targeted by China in its Made in China 2025 program. Massive subsidies from all levels of the Chinese government have flowed through a variety of channels to energy storage projects and companies to fulfill this program, helping China become the world’s largest EV market (with more than 50% market share). Korea, Japan, and India are among the other countries undertaking national energy storage initiatives.

Although the global race to advance energy-storage technology is intense, the United States possesses many strengths that would allow a domestic energy-storage effort to succeed. These strengths include outstanding research capabilities at universities and national laboratories, a vibrant start-up ecosystem, and a strong industrial sector. The NESI would provide the leadership, funding, and coordination needed to realize the full potential of these assets. It is also important for the United States to foster international cooperation around science underlying energy-storage technology. Scientific knowledge is a global public good that will be under-provided without the leadership of the world’s top scientific nation.

Stakeholder support

The NESI has a wide range of potential champions and advocates on both sides of the aisle. Congressional Republicans have expressed their support for energy storage through expanded RD&D funding and more ambitious authorizations. The administration’s new grand challenge taps into this legislative support. Environmental advocates on the left of the political spectrum are also supportive, perceiving limited energy storage as the biggest technological barrier to expanded deployment of renewables. Similar enthusiasm may be expected from the research community and investors, as well as from states seeking to build a domestic energy-storage industry. These interests have been frustrated by the “invent here, produce there” outcomes of past breakthroughs, such as lithium-ion batteries.

Technology end users may be less enthusiastic or indifferent. Low prices in the short term may be more important to them than innovation in the long run. They may also see the location and ownership of production facilities as irrelevant or argue that the current global division of labor, in which Asian factories built with cheap public-investment capital supply U.S. needs, is favorable for the United States. Other skeptics may argue that when it comes to supporting expanded deployment of renewables, investing in demand response, larger grids, or other forms of low-carbon electricity generation, such as nuclear power or natural gas plants with carbon capture systems, are better options than energy storage.

Goals and metrics

The overarching (e.g., within 10 years) goal of NESI is to make the United States a major center for energy storage innovation and production.

One essential short-term step towards achieving this goal is establishing key organizational components of the NESI, such as an interagency working group and a mechanism to engage with non-federal stakeholders, including industry, academia, and states. A second critical step is expanding budgets for relevant federal agencies to put them on a pathway to triple federal funding for energy-storage RD&D.

In the medium term, metrics such as growth in scientific publications and patents, formation of new energy-storage companies, equity and project investment, product introduction, and manufacturing-cost reduction will provide insights on progress.

In the long term, success of the NESI should be assessed by the level of market penetration of new energy-storage storage products across application domains including electric power, transportation, and electronics in the context of a growing overall storage market. Success of the NESI should also be assessed through consideration of the international trade balance related to energy storage and adoption of U.S.-developed energy-storage technologies.

Proposed initial steps

The next president should sign an EO establishing the NESI and directing the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy to convene a federal interagency task force. The task force should prepare a strategic plan and develop a budget for the initiative in consultation with key stakeholders. The plan should identify technological needs and opportunities and set specific objectives, taking into account global competition and cooperation with respect to energy storage. Congress should support the NESI by appropriating funding needed to implement the strategic plan, and by providing additional authorization as required.

Implementing agencies should pursue energy-storage RD&D as it relates to their respective missions, while collaborating to manage overlaps and avoid gaps. RD&D activities should strengthen the intramural and extramural research and industrial communities. As innovative storage technologies reach maturity, DOC, DOD, and DOE should work with states and regional economic-development agencies to foster markets and develop manufacturing capabilities. Congress should provide tax incentives that help to pull these technologies into the market, thereby driving down cost and expanding deployment.

Conclusion

Energy-storage technologies in widespread use today are not good enough to meet fundamental 21st-century challenges, including climate change, economic growth, and international security. A national initiative to accelerate domestic development and deployment of dramatically improved energy-storage technologies would position the United States to lead the world in addressing these challenges while building its economy. Although global competition in energy storage is fierce, our nation has strong capabilities that—if used strategically—position the United States to catch up with and ultimately surpass its rivals in this vital emerging industry. The NESI provides a pathway for the next president to translate this vision into reality.

Solutions for mitigating climate change, advances in nuclear energy, and US leadership in high-performance computing discussed in two key House Science Committee hearings

Climate solutions and nuclear energy

The full House Science, Space, and Technology Committee discussed climate hurdles and solutions in a January 15 hearing titled, “An update on the climate crisis: From science to solutions.” Interestingly, the main point of debate during this hearing was not whether climate change was occurring, but rather the economic impacts of climate change mitigation. As predicted, the debate was split down party lines.

While the Democrats emphasized the negative consequences of climate change and the need to act, several Republican members insisted that China and India rein in their greenhouse gas emissions first.

Congressman Mo Brooks (R, AL-05) asked the most heated series of questions during the hearing, related to India and China’s carbon emissions. He asked if there was a way to force both to reduce their emissions, which, according to a report by the European Union, have seen increases of 305% and 354%, respectively, between 1990 and 2017.

Democrats focused their questions to highlight the science behind climate change. Chairwoman Eddie Bernice Johnson (D, TX-30) asked each witness about the biggest hurdles in their fields. Richard Murray, Deputy Director and Vice President for Research at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, said that more investments in large-scale ocean observations and data are needed. Pamela McElwee, Associate Professor of Human Ecology at Rutgers, said that a lot of advances in land conservation can be made with existing technology, but that investments in genetic modification of crops to restore nutrients to the soil, for example, could be developed. Heidi Steltzer, Professor of Environment and Sustainability at Fort Lewis College, encouraged the inclusion of diverse perspectives in climate research to develop the most creative solutions. Congressman Paul Tonko (D, NY-20) summed up the Democrats’ views on climate change by stating that the climate science performed by researchers like the witnesses should inform federal action and that inaction on this issue is costly.

While committee Republicans expressed concerns over the impact of climate regulations on business, members of the committee did emphasize the importance of renewing U.S. leadership in nuclear power, pointing to competition from Russia and China. Nuclear power continues to be the largest source of carbon free electricity in the country.

One of the witnesses, Michael Shellenberger, Founder and President of Environmental Progress noted that the US’ ability to compete internationally in nuclear energy was declining as Russia and China rush to complete new power plants. Losing ground in this area, he added, negatively impacts the U.S.’ reputation as a developer of cutting edge energy technology and dissuades developing countries interested in building nuclear power plants from contracting with the U.S.

As the impacts of climate change take their toll in California, the Caribbean, Australia, and elsewhere, the U.S. Congress remains divided on how to address it.

We thank our community of experts for helping us create an informative resource and questions for the committee.

Supercomputing a high priority for DOE Office of Science

While last week’s House Science Subcommittee on Energy hearing about research supported by the Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science touched on a range of issues, competition with China on high-performance computing took center stage.

The big milestone that world powers are competing to reach in the high-performance computing field is the development of the first-ever exascale computer. An exascale computer would greatly enhance research areas like materials development for next-generation batteries, seismic analysis, weather and climate modeling, and even clinical health studies like “identifying risk factors for suicide and best practices for intervention.” It would be about a million times faster than a consumer desktop computer, operating at a quintillion calculations per second. The U.S., China, Japan, and European Union are all working to complete the first exascale system.

In the competition to develop faster and faster supercomputers, China has made rapid progress. In 2001, none of the 500 fastest supercomputers were made in China. As of June 2019, 219 of the 500 fastest supercomputers had been developed by China, and the US had 116. Notably, when the computational power of all these systems is totaled up for each country, China controls 30 percent of the world’s high-performance computing resources, while the U.S. controls 38 percent. In the past, China had asserted that it would complete an exascale computing system this year; however, it is unclear if the country will meet its goal.

A U.S. exascale system due in 2021 – Aurora – is being built at Argonne National Lab in Illinois, and hopes are high that it will be the world’s first completed exascale computer. During the hearing, Representatives Dan Lipinski (D, IL-03) and Bill Foster (D, IL-11) both raised the issue of progress on the project. According to DOE Office of Science director Dr. Christopher Fall, the Aurora project is meeting its benchmarks, with headway being made not only on the hardware, but also on a “once-in-a-generation” reworking and modernization of the software stack that will run on the system, as well as developing high-speed internet for linking generated data with the computation of that data. DOE believes that the U.S. is in a strong position to complete the first-ever exascale computing system, and that our holistic approach to high-performance computing is something that is missing from competitors’ strategies, giving the U.S. even more of an edge.

In addition to the Aurora project, two more exascale computing projects are underway at U.S. National Labs. Frontier, at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, is also projected to deploy in 2021, while El Capitan, based at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, should launch in 2022. El Capitan will only be used by individuals in the national security field.

In addition to research in high-performance computing, the diverse and impactful science supported by the DOE Office of Science is truly something to protect and promote. To review the full hearing, click here.

JASON Endorses Further Fusion Power Research

The JASON scientific advisory panel cautiously endorsed further research into what is known as Magneto-Inertial Fusion (MIF) as a step towards achieving fusion-generated electricity.

“Magneto-Inertial Fusion (MIF) is a physically plausible approach to studying controlled thermonuclear fusion in a region of parameter space that is less explored than Inertial Confinement Fusion (ICF) or Magnetic Confinement Fusion (MCF).”

“Despite having received ~1% the funding of MCF and ICF, MIF experiments have made rapid progress in recent years toward break-even conditions,” the JASONs said in a report to the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E) late last year.

Even so, “Given the immaturity of the technologies, the future ability of fusion-generated electricity to meet commercial constraints cannot be usefully assessed. Rapidly developing infrastructures for natural gas and renewable energy sources and storage will compete with any future commercial fusion efforts.”

See Prospects for Low Cost Fusion Development, JASON Report JSR-18-011, November 2018.

The fusion report is one of two unclassified reports prepared by the JASONs in 2018. (Release of the second is pending.) The other twelve reports from last year are classified.

The New York Times recently provided an overview of fusion research in Clean, Abundant Energy: Fusion Dreams Never End by C. Claiborne Ray, January 11, 2019.

Meanwhile, the Federation of American Scientists warned that the current shutdown of federal agencies threatens many aspects of U.S. science and technology.

“The partial government shutdown is compromising the very research that is important to the health and security of our nation. Important scientific breakthroughs could be compromised or lost with each and every day that the shutdown continues,” FAS said in a January 16 letter to the White House and Congress.

“We therefore urge you to open the federal government, send researchers back to work at their agencies, and allow science to flourish throughout the United States.”

Trump Admin Would Curtail Carbon Capture Research

The Trump Administration budget request for FY 2018 would “severely reduce” Energy Department funding for development of carbon capture and sequestration technologies intended to combat the climate change effects of burning fossil fuels.

The United States has “more than 250 years’ worth of clean, beautiful coal,” President Trump said last month, implying that remedial measures to diminish the environmental impact of coal power generation are unnecessary.

Research on the carbon capture technology that could make coal use cleaner by removing carbon dioxide from power plant exhaust would be cut by 73% if the Trump Administration has its way.

“The Trump Administration’s approach would be a reversal of Obama Administration and George W. Bush Administration DOE policies, which supported large carbon-capture demonstration projects and large injection and sequestration demonstration projects,” the Congressional Research Service said this week in a new report.

“We have finally ended the war on coal,” President Trump declared.

However, congressional approval of the Administration’s proposal to slash carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) development is not a foregone conclusion.

“The House Appropriations Committee’s FY2018 bill funding DOE disagrees with the Administration budget request and would fund CCS activities at roughly FY2017 levels,” the CRS report said.

“This report provides a summary and analysis of the current state of CCS in the United States.” It also includes a primer on how CCS could work, and a profile of previous funding in this area. See Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) in the United States, July 24, 2017.

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Methane and Other Air Pollution Issues in Natural Gas Systems, updated July 27, 2017

The U.S. Export Control System and the Export Control Reform Initiative, updated July 24, 2017

Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS): OECD Tax Proposals, July 24, 2017

Oman: Reform, Security, and U.S. Policy, updated July 25, 2017

Lebanon, updated July 25, 2017

Aviation Bills Take Flight, but Legislative Path Remains Unclear, CRS Insight, July 25, 2017

Military Officers, CRS In Focus, July 3, 2017

Military Enlisted Personnel, CRS In Focus, July 3, 2017

Transgender Servicemembers: Policy Shifts and Considerations for Congress, CRS Insight, July 26, 2017

Systematic, authorized publication of CRS reports on a government website came a step closer to reality yesterday when the Senate Appropriations Committee voted to approve “a provision that will make non-confidential CRS reports available to the public via the Government Publishing Office’s website.”

Energy Policy and National Security: The Need for a Nonpartisan Plan

As I write this president’s message, the U.S. election has just resulted in a resounding victory for the Republican Party, which will have control of both the Senate and House of Representatives when the new Congress convenes in January. While some may despair that these results portend an even more divided federal government with a Democratic president and a Republican Congress, I choose to view this event as an opportunity in disguise in regards to the important and urgent issue of U.S. energy policy.

President Barack Obama has staked a major part of his presidential legacy on combating climate change. He has felt stymied by the inability to convince Congress to pass comprehensive legislation to mandate substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Instead, his administration has leveraged the power of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to craft rules that will, in effect, force the closure of many of the biggest emitters: coal power plants. These new rules will likely face challenges in courts and Congress. To withstand the legal challenge, EPA lawyers are working overtime to make the rules as ironclad as possible.

The Republicans who oppose the EPA rules will have difficulty in overturning the rules with legislation because they do not have the veto-proof supermajority of two-thirds of Congress. Rather, the incoming Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) said before the election that he would try to block appropriations that would be needed to implement the new rules. But this is a risky move because it could result in a budget battle with the White House. The United States cannot afford another grinding halt to the federal budget.

Several environmental organizations have charged many Republican politicians with being climate change deniers. Huge amounts of money were funneled to the political races on both sides of the climate change divide. On the skeptical side, political action groups affiliated with the billionaire brothers Charles and David Koch received tens of millions of dollars; they have cast doubt on the scientific studies of climate change. And on the side of wanting to combat climate change, about $100 million was committed by NextGen Climate, a political action group backed substantially by billionaire Tom Steyer. Could this money have been better spent on investments in shoring up the crumbling U.S. energy infrastructure? Instead of demonizing each side and just focusing on climate change, can the nation try a different approach that can win support from a core group of Democrats and Republicans?

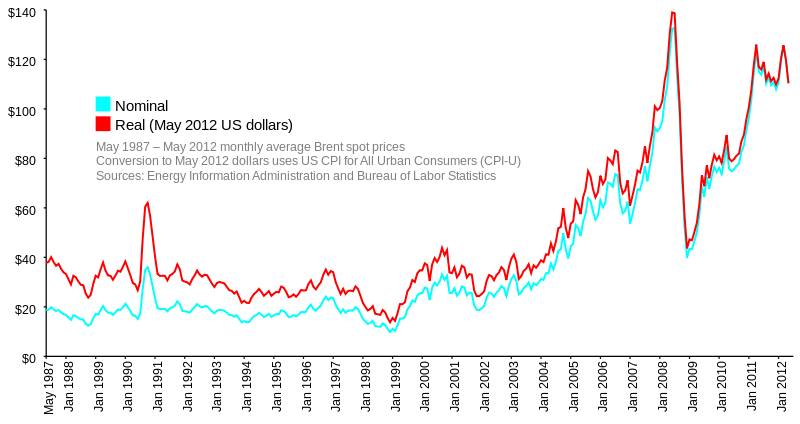

Both Democratic and Republican leaders believe that the United States must have strong national security. Could this form the basis of a bipartisan plan for better energy policy? But this begs another question that would have to be addressed first: What energy policy would strengthen national security? Some politicians, including several former presidents, have called for the United States to be energy independent. Due to the recent energy revolution in technologies to extract so-called unconventional oil and gas from shale and sand geological deposits, the United States is on the verge of becoming a major exporter of natural gas and has dramatically reduced its dependence on outside oil imports (except from the friendly Canadians who are experiencing a bonanza in oil extracted from tar sands). However, these windfall developments do not mean that the United States is energy independent, even including the natural resources in all of North America.

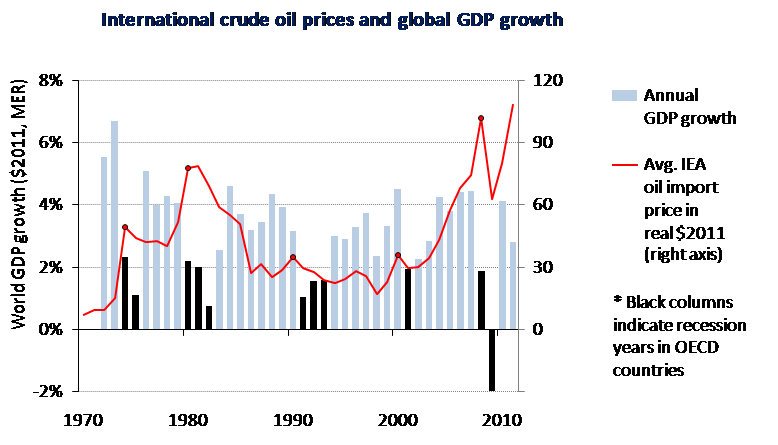

Oil is a globally traded commodity and natural gas (especially in the form of liquefied natural gas) is tending to become this type of commodity. This implies that the United States cannot decouple its oil and gas production and consumption from other countries. For example, a disruption in the Strait of Hormuz leading to the Persian Gulf will affect about 40 percent of the globe’s oil deliveries because of shipments from Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirate. Such a disruption might occur in an armed conflict with Iran, which has been at loggerheads with the United States over its nuclear program. Moreover, while the United States has not been importing significant amounts of oil from the Middle East recently, U.S. allies Japan and South Korea rely heavily on oil from that region. Thus, a major principle for U.S. national security is to work cooperatively with these allies to develop a plan to move away from overreliance on oil and gas from this region and an even longer term plan to transition away from fossil fuels.

Actually, this long term plan is not really that far into the future. According to optimistic estimates (for example, from Cambridge Energy Research Associates) for when global oil production will reach its peak, the world only has until at least 2030 before the peak is reached, and then there will be a gradual decline in production over the next few decades after the peak.1 (Pessimistic views such as from oil expert Colin Campbell predict the peak occurring around 2012 to 2015.2 We thus may already be at the peak.) Once the global decline starts to take effect, price shocks could devastate the world’s economy. Moreover, as the world’s population is projected to increase from seven billion people today to about nine billion by mid-century, the demand for oil will also significantly increase given business as usual practices.

For the broader scope national security reason of having a stable economy, it is imperative to develop a nonpartisan plan for transitioning from the “addiction” to oil that President George W. Bush called attention to in his State of the Union Address in January 2006. While skepticism about the science of climate change will prevail, this should not hold back the United States working together with other nations to craft a comprehensive energy plan that saves money, creates more jobs, and overall strengthens international security.

FAS is developing a new project titled Sustainable Energy and International Security. FAS staff will be contacting experts in our network to form a diverse group with expertise in energy technologies, the social factors that affect energy use, military perspectives, economic assessments, and security alliances. I welcome readers’ advice and donations to start this project; please contact me at cferguson@fas.org. FAS relies on donors like you to help support our projects; I urge you to consider supporting this and other FAS projects.

Keeping the Lights on: Fixing Pakistan’s Energy Crisis

A stable and thriving Pakistan is the key to preserving harmony and facilitating progress in the broader South Asia region. Afghanistan, which is to the west of Pakistan, has a long border that divides the Pakhtun people between the countries. As a result of this border, Pakistan not only has a significant role in the Afghan economy, but instability in the loosely governed Pakistani frontier region spills across the border into Afghanistan. Because of this relationship, Pakistan has a direct impact on the outcome on the 13 year U.S. led war in Afghanistan. On the other hand, an unstable Pakistan would not only shatter budding trade relations with India, but could also spark conflict between the two nuclear armed rivals.

From frequent attacks by Islamic militants across the country to a slowing economy, it is clear that there are many issues that threaten Pakistan’s stability. However, the most pressing issue that Pakistan faces today is its deteriorating economy. In particular, a crushing energy shortage across the country significantly constrains economic growth. This fiscal year, Pakistan’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is forecasted to grow by measly 3.4 percent. At the same time, the country’s population is expected to grow by 1.8 percent adding to the 189 million people living there today. If there aren’t jobs available for the millions of young Pakistanis entering the work force, not only will poverty increase, but there is a strong possibly that some of these youth could vent their frustrations by joining the countless Islamic militant groups active in the country.

To build a more prosperous economy, Pakistan needs to address its energy problems. Without a reliable source of electricity or natural gas, how can Pakistani businesses compete on the global market? Large parts of the country today face blackouts lasting an average of 10 hours each day because of the electricity shortage. The current gap between electricity generation and demand is roughly 2500 MW, a shortage large enough to keep a population of 20 million or the city of Karachi in the dark.

These power shortages are only expected to become worse in the coming summer months. This is because demand for electricity peaks in the sizzling heat, while hydroelectric generation decreases as the water flow in the rivers drops due to seasonal fluctuation. This article will focus on the causes of the country’s energy problems involving the electricity sector and explore possible directions Pakistan can take to improve its energy situation, building its economy in the process.

How Does Pakistan Generate its Electricity?

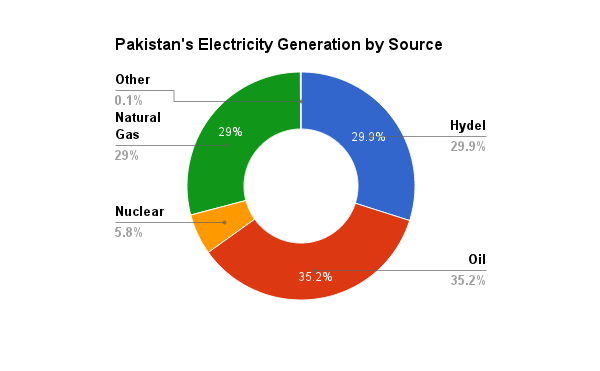

Figure 1 breaks down Pakistan’s electricity generation by source. Thermal power, which includes natural gas, oil, and coal generated electricity, accounts for 70 percent of Pakistan’s total electricity generation, while hydroelectric generation is roughly responsible for the remaining 30 percent.

Electricity generated from furnace oil accounts for slightly over a third of Pakistan electricity. In the early 1990s, the country faced a power shortage of about 2000 MW when there was a peak load on the electricity grid. To resolve the growing crisis, the Pakistani government implemented a new policy in 1994, which was designed to attract foreign investment in the power sector and as a result there was construction of oil based power plants. These power plants were cheaper and faster to construct compared to other electricity generation plants such as hydroelectric dams. At the same time, the relatively low prices (below $17 a barrel) of crude oil meant that these plants generated electricity fairly cheaply. Fast forward to present times, the price of crude oil has risen to hover roughly around $100 a barrel. Unlike nearby Saudi Arabia, Pakistan is naturally not well endowed in crude oil reserves. This means that Pakistan must ship increasing amount of valuable currency abroad to secure the oil it needs to keeps these power plants running.

Along with furnace oil power plants, natural gas is used to generate about another third of electricity; it is provided by domestic reserves, thereby helping Pakistan’s economy and energy security. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, Pakistan has proven natural gas reserves of 24 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) in 2012. These reserves will last Pakistan an estimated 17 years based on the country’s annual consumption rate of 1.382 Tcf in 2012. At the same time, consumption rates are estimated to increase four fold to nearly 8 Tcf per year by the year 2020, further reducing the size of the domestic reserves.

The Pakistani government in 2005 under President Pervez Musharraf promoted the conversion of cars to run on compressed natural gas (CNG) instead of gasoline. The rationale was that this conversion would reduce the amount of money spent on purchasing and importing oil abroad. At the same time, CNG is cleaner for the environment than burning gasoline. As a result of this policy, more than 80 percent of Pakistan’s cars today run on CNG.But because of this surging demand for its limited natural gas, there is a critical shortage of it which has adversely impacted the country’s ability to use this fuel source to generate electricity. Essentially Pakistanis are forced to decide whether to use natural gas to fuel their cars, cook their food, or generate electricity.

Power Theft and the Circular Debt Issue

The reliance on oil and natural gas to generate electricity is incredibly inefficient, but these inefficiencies alone are not responsible for the crippling power shortages. The other source of tension involves the accumulation of circular debt in the electricity sector over the past few years. Circular debt is a situation where consumers, electricity producers and the government all owe each other money and are unable to pay. By June 2013 when the new government led by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif took control, this circular debt had ballooned to $5 billion.

There are several reasons for the accumulation of this debt; the largest problem stems from power theft. Many Pakistani elites and even parts of the government do not pay their electricity bills. The law and order situation also prevent power companies from collecting bills in certain parts of the country. As a result, Pakistani electricity companies currently recover only 76 percent of the money that electricity consumers owe them. In fact, the Pakistani Minister for Water and Power, Mr. Khwaja Muhammad Asif, has acknowledged that the Pakistani government is one of the country’s largest defaulters of electricity bills. As part of recent crackdown, the power ministry cut supplies to the Prime Minister’s home and the Parliament House (among many government offices) because they were delinquent on their electricity bills. While many Pakistanis don’t pay their electricity bills, others steal power by illegally hooking into the power grid. This theft coupled with an inefficient electricity grid and the associated transmission loss means that Pakistan’s electricity generators are left with huge financial losses.

All these losses accumulate to form the circular debt and it places power producers in a position where they are unable to purchase enough fuel from abroad to operate power plants at full capacity. With an installed generation capacity of 22500 MW, Pakistan currently has more than enough installed capacity to meet peak demand levels today. The power producers are in reality only able to generate between 12000MW and 15000MW because of both inefficient energy infrastructure and circular debt. This actual amount of electricity generated is far less than the 17000 MW of demand nationwide during peak hours of electricity usage.

The circular debt also makes it more difficult for power producers to invest in upgrading existing electricity infrastructure. If power producers don’t have the money to operate oil based power plants at full capacity, they certainly do not have enough capital to build newer, more efficient power plants. Even when the lights are on, the inefficient electricity system takes an additional toll on the country’s economy. Pakistanis today pay more than double their Indian neighbors for electricity (16.95 Pakistani Rupees vs. 7.36 Pakistani Rupees per KWh respectively), putting Pakistani firms at a further disadvantage compared to regional competitors.

Fixing Pakistan’s Electricity Problems

One of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s first actions after taking office was to pay off the $5 billion in circular debt that had accumulated by July 2013. Unfortunately, this step alone will not solve the power woes as it does not fix the underlying causes of the country’s power crisis. In fact, the circular debt has accumulate again, and stood at $1.8 billion by January 2014. To sustainably address the power crisis, Pakistanis need to change their attitude towards power theft by forcing the government and those delinquent to clear outstanding bills. At the same time, Pakistan must improve the efficiency of its electricity sector as well as expand and diversify its electricity generating capacity in order to ensure that the country can handle the expected growth in demand over the coming years.

Hydroelectric Generation

Pakistan has tremendous potential to expand its electricity generating capacity by developing its renewable energy resources. At nearly 30 percent, hydroelectricity is already a major source of electricity generation, but according to the Pakistani government, this reflects only 13 percent of the total hydroelectric potential of the country. There are several drawbacks of major hydroelectric projects including that they are capital intensive and require extensive time to build. Furthermore, hydroelectric dams are harmful to the local ecosystem and can displace large populations. The U.S. government is actively investing in helping Pakistan develop its hydroelectric resources; in 2011, USAID funded the renovation of the Tarbela Dam. In the process, this added generation capacity of 128 MW, which is enough electricity for 2 million Pakistanis.

Solar Energy

According to the USAID map of solar potential in Pakistan, the country has tremendous potential in harnessing the sun to generate electricity. Pakistan has an average daily insolation rate of 5.3 kWH/m2, which is similar to the average daily insolation rate in Phoenix (5.38 kWH/m2) or Las Vegas (5.3 kWH/m2), which are some of the best locations in the United States for solar generated electricity. So far, Pakistan has begun construction on a photovoltaic power plant in Punjab that will begin to produce 100 MW by the end of 2014.According to the World Bank some 40,000 villages in Pakistan are not electrified. Tapping into these solar resources could easily electrify many of these off the grid villages, while avoiding an increase in demand on the national electricity grid.

Nuclear Energy

Pakistan has three currently active nuclear power plants: two located in Punjab and one in the southern port city of Karachi. The two Chinese built nuclear power plants in Punjab each have a net generation capacity of 300 MW. The Karachi power plant, which was built with a reactor supplied by Canada in 1972, has a net generation capacity of 125 MW, enough to provide power to 2 million Pakistanis. China has been a key supplier and investor in Pakistani nuclear energy, but there are some concerns regarding the transfer of nuclear technology to Pakistan, where A.Q. Khan’s nuclear network was headquartered. Specifically, China argues that its alliance with Pakistan predates its joining of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), which has restricted nuclear sales to Pakistan, so this justifies its desire to supply Pakistan with the technology. The Chinese are helping construct four more nuclear power plants, the first of which is expected to be online starting in 2019. While these plants will add 2,200 MW of generation capacity, these nuclear power projects are expensive; the current nuclear power plants under construction are said to cost about $5 billion per plant, an investment that China is helping finance.

Coal Power

There is a large amount of coal located in the Thar Desert in the southeastern part of the country. While the quality of the coal isn’t the best, Pakistan has a lot of it, nearly 175 billion tons, which is enough to meet current electricity demands for more than 300 years. However, Pakistan currently only has one operational coal power plant.

Pakistan is taking steps to develop this resource. In January 2014, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and former President Zardari broke ground on a $1.6 billion coal power project in the Thar Desert. This particular project is expected to be operational by 2017.

Pakistan has taken some clear steps such as developing its renewable resources and tapping its coal reserves, which can help expand and diversify where and how it generates its electricity. Further harnessing these resources will help alleviate the electricity shortfall. However, these steps alone will not solve the energy crisis. The more difficult solution involves changing the country’s attitude toward power theft, both by private citizens and the government. Convincing people to pay their electricity bills is difficult when even the government itself doesn’t pay its fair share. At the same time, there is less incentive to pay when citizens don’t even have access to a dependable source of electricity when they need it. As long as this attitude is prevalent among Pakistanis from all walks of life as well as the government, the country cannot sustainably solve its energy woes. Circular debt will continue to accumulate and large sections of the country will face hours of darkness each day.

Tackling the energy problem is the first step to strengthening the economy; over time, a growing economy will attract greater investment in the energy sector. Pakistan’s sensitive geographic location could become a strategic asset as it would serve as a bridge linking the economies of Afghanistan and Central Asia with the broader Indian subcontinent. Not only does the population provide Pakistan with a large domestic market, but it also empowers the country with a young, entrepreneurial workforce. This gives Pakistan tremendous potential, but can only be unleashed if the country figures out a way to keep the lights on and the factories humming.

Population Projection Tables by Country: Pakistan. The World Bank. 2014.

“Global Economic Prospects: Pakistan,” The World Bank, 2014. http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects/regional-outlooks/sar

Ghumman, Khawar, “Increased loadshedding worries Prime Minister,” Dawn, April 24 2014. http://www.dawn.com/news/1102953

“Electricity shortfall reaches 2,500MW,” The Nation, Jan 2 2014. http://www.nation.com.pk/national/02-Jan-2014/electricity-shortfall-reaches-2-500mw

“Pakistan Energy Yearbook,” Hydrocarbon Development Institute of Pakistan, 2012. http://www.kpkep.com/documents/Pakistan%20Energy%20Yearbook%202012.pdf

“Policy Framework and Package of Incentives for Private Sector Power Generation Projects in Pakistan,” Government of Pakistan, 1994. http://www.ppib.gov.pk/Power%20Policy%201994.pdf

Beg, Fatima and Fahd Ali, “The History of Private Power in Pakistan,” Sustainable Development Policy Institute, 2007. http://www.sdpi.org/publications/files/A106-A.pdf

“Crude Oil Purchase Price.” U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2014. http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=F004056__3&f=M

Pakistan. U.S. Energy Information Administration. http://www.eia.gov/countries/country-data.cfm?fips=pk

Tirmizi, Farooq, “The Myth of Pakistan’s infinite gas reserves,” The Express Tribune, Mar 14 2011. http://tribune.com.pk/story/132244/the-myth-of-pakistans-infinite-gas-reserves/

“Natural Gas Allocation and Management Policy,” Government of Pakistan: Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Resources, Sept 2005. http://www.ogra.org.pk/images/data/downloads/1389160019.pdf

Boone, Jon, “Pakistan’s government deflates dream of gas-powered cars,” The Guardian, Dec 25 2013. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/25/cars-pakistan-compressed-natural-gas-rationing

Bhutta, Zafar, “Circular debt: Power sector liabilities may cross Rs1 trillion by 2014,” The Express Tribune, May 26 2013. http://tribune.com.pk/story/554370/circular-debt-power-sector-liabilities-may-cross-rs1-trillion-by-2014/

Pakistan’s Energy Crisis: Power Politics. The Economist, May 21 2012.http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2012/05/pakistan%E2%80%99s-energy-crisis

Jamal, Nasir. “Amount of unpaid power bills increases to Rs286bn.” Dawn. Apr 16 2014. http://www.dawn.com/news/1100237

“Govt one of the biggest electricity defaulters, says Khawaja Asif.” Dawn, May 2 2014. http://www.dawn.com/news/1103707

“Pakistan cuts prime minister’s electricity for not paying bills” Reuters. Apr 29 2014. http://in.reuters.com/article/2014/04/29/uk-pakistan-electricity-idINKBN0DF1DL20140429

Kazmi, Shabbir. “Pakistan’s Energy Crisis.” The Diplomat, Aug 31 2013. http://thediplomat.com/2013/08/pakistans-energy-crisis/

Abduhu, Salman. “Lack of funds real reason behind loadshedding.” The Nation, May 9 2014. http://www.nation.com.pk/lahore/09-May-2014/lack-of-funds-real-reason-behind-loadshedding

Electricity Shock: “Pakistanis Paying the Highest Tariffs in Region.” The Express Tribune, Jan 31 2014. http://tribune.com.pk/story/665548/electricity-shock-pakistanis-paying-highest-tariffs-in-region/

Chaudhry, Javed. “Circular Debt: ‘All dues will be cleared by July’.” The Express Tribune, June 14 2013. http://tribune.com.pk/story/563095/circular-debt-all-dues-will-be-cleared-by-july/

“Hydropower Resources of Pakistan.” Private Power and Infrastructure Board, Feb 2011. http://www.ppib.gov.pk/HYDRO.pdf

USAID Issues $6.66 m for Tarbela Units. Dawn. Mar 9 2011. http://www.dawn.com/news/612058/usaid-issues-666m-for-tarbela-units

“Tarbela Dam Project.” USAID, Sept 26 2013. http://www.ppib.gov.pk/HYDRO.pdf

“Pakistan Resource Maps.” National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Aug 2006. http://www.nrel.gov/international/ra_pakistan.html

The Feasibility of Renewable Energy in Pakistan, Triple Bottom-Line, 2012. http://www.tbl.com.pk/the-feasibility-of-renewable-energy-in-pakistan/

“Surface Meteorology and Solar Energy,” NASA, 2013. https://eosweb.larc.nasa.gov/sse/RETScreen/

Quad-e-Azam Solar Power. http://www.qasolar.com/

Renewable Energy in Pakistan: Opportunities and Challenges, COMSATS-Science Vision, December 2011. http://www.sciencevision.org.pk/BackIssues/Vol16_Vol17/02_Vol16_and_17_Renewable%20Energy%20in%20Pakistan_IrfanAfzalMirza.pdf

CHASNUPP-1. Nuclear Threat Initiative, 2014. http://www.nti.org/facilities/112/

CHASNUPP-2. Nuclear Threat Initiative, 2014. http://www.nti.org/facilities/113/

KANUPP. Nuclear Threat Initiative, 2014. http://www.nti.org/facilities/111/

Shah, Saeed. “Pakistan in Talks to Acquire 3 Nuclear Plants From China.” The Wall Street Journal, Jan 20 2014. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304757004579332460821261146

Mahr, Krista. “How Pakistan and China Are Strengthening Nuclear Ties.” Time, Dec 2 2013. http://world.time.com/2013/12/02/how-pakistan-and-china-are-strengthening-nuclear-ties/

“Pakistan’s Thar Coal Power Generation Potential.” Private Power and Infrastructure Board, July 2008.http://www.embassyofpakistanusa.org/forms/Thar%20Coal%20Power%20Generation.pdf

“Discovery Of Ignite Coal In Thar Desert.” Geological Survey of Pakistan, 2009. http://www.gsp.gov.pk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=30:thar-coal&catid=1:data

“Nawaz, Zardari launch Thar coal power project.” Dawn, Jan 31 2014. http://www.dawn.com/news/1084003

Ravi Patel is a student at Stanford University where he recently completed a B.S. in Biology and is currently pursuing an M.S. in Biology. He completed an honors thesis on developing greater Indo-Pakistan trade under Sec. William Perry at the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC). Patel is the president of the Stanford U.S.-Russia Forum. He also founded the U.S.-Pakistan Partnership, a collaborative research program linking American and Pakistani university students. In the summer of 2012, Patel was a security scholar at the Federation of American Scientists. He also has extensive biomedical research experience focused on growing bone using mesenchymal stem cells through previous work at UCSF’s surgical research laboratory and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Nelson Zhao is a fourth year undergraduate at University of California, Davis pursuing degrees in economics and psychology. Nelson is the Vice-President at the Stanford U.S.-Russia Forum and the Program Director at the U.S.-Pakistan Partnership. At the U.S.-Pakistan Partnership, he aims to develop a platform to convene the brightest students in order to cultivate U.S.-Pakistan’s bilateral relations.

Geopolitical and Cyber Risks to Oil and Gas

Whether an oil and gas company is working in the United States or is spread throughout the world, it will face geopolitical and cyber risks which could affect global energy security.

Geopolitical Risk

There are numerous geopolitical risks for any oil and gas company. Even if a company just works in the United States, it needs to know what is happening in countries all over the world, especially those countries that are large oil and gas producers. Because oil markets are so tightly connected globally, major political events in oil exporting states could seriously affect the price and even availability of oil. An attack on an oil platform in Nigeria, a terrorist event in Iraq, the closing down of port facilities in Libya and many other examples come to mind. Consider the potential effects of a major attack on the Ab Qaiq facility in Saudi Arabia. If this facility is damaged or destroyed on a large scale by rockets or bombs, the world oil market could be out 6-7 million barrels of oil a day- out of the 90-92 millions of barrels a day the world needs. World spare oil production capacity is about 2.3 million barrels a day. It could take some time to get this online. The spare production can be ramped up, but not immediately. Given that the grand majority of excess capacity in the world is located in Saudi Arabia and that this excess capacity could be significantly cut back with damage to Ab Qaiq, the situation is even riskier.

Another major risk nearby is transits through the Straits of Hormuz. About 16-17 million barrels a day goes out of the Straits. Any attempts to close the Straits (even unsuccessful ones) could have significant effects on the prices of various grades of oil. Even with the seemingly warming in relations between the U.S. and Iran, it is still possible that things could take a turn for the worse in the Gulf region. If the present negotiations with Iran break down, tensions could rise to even higher levels than before negotiations began. This could bring discussions of the military option more public. If there is a major conflict involving Gulf countries, the United States and its allies, then all bets are off on where oil prices may go. There could be many scenarios: from oil prices increasing $100 over the pre-conflict base price to well over $200 over the pre-conflict base price.

In many other parts of the world, geopolitical risks going “kinetic” can affect oil markets. Syria is a potential whirlpool of trouble for the entire Middle East. Egypt and Libya are far from stable. Algeria could be heading into some rough times. The Sudan’s will remain problematic and potentially quite violent for some time to come. The East China Sea and South China Sea disputes are not resolved. The Central Sahara could be a source and locale for troubles for some time to come.

Terrorist events can happen anywhere. Google Earth allows terrorists and others to get very close looks at major oil and gas facilities, transport choke points and more. Also, there are not that many tankers plying the vast seas and oceans of the world. Some of the most important routes are between the Gulf region and East Asia and Europe. Others travel from West Africa to Europe, and less so to the United States than before its shale oil revolution. The Mediterranean has many important tanker shipping routes. The Red Sea is a crucial route for both ships going north and south. Over 50 percent of oil trade happens on maritime routes. Many of these tankers cross through vital chokepoints like the Strait of Malacca, the Strait of Hormuz, The Bab al Mandab, The Suez Canal, The Turkish Straits, The Danish Straits, The Panama Canal, and various harbor and river routes where risks may be higher r at sea. Even whilst at sea, ships are at risk as shown by pirate attacks and hijackings off of East Africa, West Africa and previously off of Indonesia. There are about 1,996 crude oil tankers. However, only 623 of these are of the Ultra Large Crude Carrier (ULCC) or Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC) variety that are the most important for transporting crude oil economically over long distances from the Gulf region to places like China (the biggest importer of oil), the United States, Japan, South Korea, and Europe. VLCCs can carry about 2 million barrels of oil while ULCCs can carry up to 2.3 or, rarely, 2.5 million barrels of oil. Normally these massive ships carry crude oil, but sometimes carry many different types of crude oil. Smaller petroleum tankers may carry both crude and refined products depending on their trade routes and the state of the markets at any times. There are about 493 Suez Max tankers, which can hold about 1 million barrels of oil and refined products and about 408 Afrimax vessels, which hold about 500,000 to 800,000 barrels of crude or refined products. Additionally, there are 417 Panamax vessels, which can carry 300,000 to 500,000 barrels of oil or refined products.

This may seem like a lot of ships to some. However, especially in tight markets, the pressure is immense to keep these ships at sea and to keep them on time. Moreover, there are lots of logistical complexities in trying to keep the crude moving at the right times and to the right places. If anything disturbs this complex economic and logistical ballet of behemoths, then the economic effects could be considerable. If the oil does not arrive on time then refinery production and deliveries of refined products to markets could be disturbed. Most countries have crude and product reserves to handle short term disruptions that may result from tanker losses. If the tanker losses are large or other disruptions occur in the supply chains of crude via ships, then those reserves could be worn down. It takes well over a year to build one of these tankers.

If the market for tankers is soft and some available tankers are moored in port, (such as when close to 500 hundred ships and dozens of tankers were moored off Singapore a few years ago), then the chances are better of getting the shipping logistics back to normal faster. However, problems could still arise in getting ships needed in Houston or Ras Tanura from Singapore. The travel times of these massive ships add considerable costs and disruptions.

When disruptions occur, some crude cargos can change direction and can be sold and resold, depending on the sorts of contracts that are in effect, along the way. Sometimes the disruptions are from political events, such as revolutions, insurrections, civil instability, and natural events like hurricanes and tsunamis. For example, when the tsunami hit Japan on March 11, 2011, many cargos were delayed or reconfigured. However, these sorts of events are different from terrorists blowing up a series of ships, as the psychology is different.

There is a certain amount of flexibility built into crude tanker transport markets, but a larger question is what would happen if many of them were taken out in various parts of the world. Would such a “black swan event” cause great disruptions? This is most likely. The follow on question would be how the tanker and other connected markets would react to this to help resolve the logistical attacks and how this might affect tanker insurance and lease rates.

Given that the crude and other products feed into other supply chains and markets, there could be cascades of disruptions in many parts of the world from a significant attack on even one large VLCC. Attacks on more ships would become increasingly more complex and costly in their effects.

If even one ship is sunk with a missile, the effects on oil markets and the world economy could far outweigh the mere few hundred millions of dollars in value the tanker and its cargo may represent. Ports, pipelines, refineries, tankers and other parts of the oil, transport and other infrastructures could be affected.

The destruction of an oil facility in a sensitive area that may be worth a few billion dollars could have a negative economic impact globally in the hundreds of billions, if not more. Attacks on the Houston Ship Channel, the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port, Ras Tanura in Saudi Arabia, the Jubail Complex in Saudi Arabia, Kharg or Lavan Island in Saudi Arabia could have considerable impacts economically and even militarily.

The impacts of attacks on these facilities would be stronger when oil and tanker markets are tight, and when the world or salient regional economies are growing quickly. An attack on a major tanker route out of Saudi Arabia heading to China or Japan will have a lot less effect on tanker and oil markets when there are excess tankers at anchor, and when there is excess capacity in oil production to make up in a relatively short time than when both tanker and oil markets are tight and there is little excess capacity. The less elastic the markets, the more effect any attacks will have. If a terrorist group wanted to have the most impact on the world economy it would likely attack in times of high growth in various important economies and when there is little excess oil capacity and no spare tankers. Often these three markets are tied together. When the global economy is growing quickly oil markets are under stress. When oil markets are under stress then tanker markets are stressed.

Looking to the future, some countries could be facing political turmoil such as Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Venezuela. This turmoil is not deterministic, but it is also not completely out of the bounds of probability. Depending on the type of turmoil, damage, and loss of production and export capacity, these events could have significant effects on world oil markets.

If such turmoil is going to happen, it is better for the world oil markets and the world economy that these happen during times of greater excess production and export capacity than the losses in oil production and export capacity from the turmoil. The worst of all possible combinations would be the loss of production and export capacity during very tight market times in a country where most of the excess capacity is found, which is in Saudi Arabia. If the world economy is growing quickly all around, then the effects of such turmoil will be far greater than if the world economy is in a slow growth period.

There are also regional aspects; during the 2011 Libyan Revolution, Europe’s economy was starting to dig itself out of a deep recession that had affected most European countries. Most of Libya’s oil that was cut off for a while was supposed to go to European countries, especially Italy, Spain, and France. Libyan oil production was about 1.7 million barrels a day until the civil war/ revolution began in February 2011. About 1.5 million barrels a day was exported. After the beginning of the conflict, production dropped to about 200,000 barrels a day, and did not recover until the post-civil war “recovery” that began about 8 months later. In the period between the start of the civil war/ revolution and the start of the ramp up, oil production dropped to 100,000 barrels a day and then on down to about zero barrels a day. Very little was exported during the times of the conflict. The fact that many European economies were growing slowly, or in some cases not growing at all, helped alleviate the potential effects of the cutting off of oil shipped from Libya. About 85 percent of Libya’s oil exports before the conflict went to Europe. The countries that relied considerably on Libyan were Italy, Austria, Ireland, Switzerland, Spain, Austria, and France. However, most of these were in slow-growth phases due to the ongoing recession and growing financial crises in their countries. The tanker markets were also soft and there was significant excess capacity of oil production in Saudi Arabia. The Saudis tried to backfill some orders for Libyan crude, but some of these did not work out well due to the heavier, sourer nature of the available Saudi crude compared to the usually light, sweet crude out of Libya. Switzerland is different from the other European countries as its “consumption” of Libyan oil was mostly for trading the oil in hedge funds and the big commodity firms in Geneva. The rest of these countries needed it for their overall economic needs.

Libyan crude production increased to about 1.4-1.5 million barrels a day until further problems occurred in mid-2013 with strikes at the ports and some energy facilities. Production is now down to 200,000 barrels per day. The effects on prices has been a lot less this time than during the civil war due to new, more flexible trading arrangements and better planning for such contingencies out of Libya, but also because the European economy and tanker markets remain weak.

Many Americans may think that they are relatively immune from geopolitical turmoil in oil disruptions because of the shale oil and gas revolution in the United States and Canada. However, there is potential for the increase in trade of oil with Canada which will result in greater access to oil and gas. But, this will not buffer the United States from the vagaries of oil prices caused by geopolitical events. This is mainly due to oil being a globally traded commodity.

Unlike the oil industry, the natural gas industry is not fully globally integrated, but it looks to be heading that way. As more countries invest in both conventional and unconventional reserves production, the development of LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) export and import facilities, and expansions of major international pipeline networks, the world natural gas market will have some great changes. Some of these may include the convergence of prices of natural gas globally. Recent prices of natural gas (FOB – Freight on Board, where the buyer pays for transport costs) in China were about $15 per MMBTU (Million British Thermal Units), a common measurement of natural gas amounts. In Japan they were in the $16-17 ranger per MMTBTU. In many parts of Western Europe LNG (FOB) prices were about $9-11 per MMBTU. Natural gas in the United States recently has sold for about $3 per MMBTU. Qatar could sell at cost for much lower, as it sells to the United States for about $3 MMBTU similar LNG that it sells to China and Japan for much higher prices. With the convergence of prices, the lower cost countries will likely be the survivors. Others may have to drop out if they have to export the LNG at a loss, unless the country subsidizes these exports, which would be problematic under the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements.

Those countries that develop their LNG export facilities the fastest will capture more of the most important markets (such as Japan, South Korea, and especially the potentially gigantic market in China), than those countries that doddle along in their decisions to export or not. The future of global gas markets is more of a very competitive and very expensive 4D chess game played by very powerful people, rather than just some engineering or economics exercise as some look at it.

As the now regional and segmented natural gas markets develop into global integrated markets, they will become more efficient and regional prices will start to converge toward a global price, much like oil. As the global natural gas markets develop, there will be more spot markets developed and less need for long term contracts in many instances. For decades, oil and gas prices were linked. As a global natural gas market develops, and especially with the further spread of the shale gas revolution, fewer and fewer natural gas contracts will be linked to oil prices. However, this integration of the natural gas industry globally also brings the risk of terrorist or political driven turmoil at or near LNG ports, LNG ships, and even in the market trading centers in places far removed from the United States. The more globally integrated the natural gas markets are, the more likely reverberations to prices will occur globally, rather than just locally. It is sort of like dropping a large rock in a pond with many barriers compared to dropping a large rock in a pond without many barriers in it. The waves will have more extensive effects without the barriers.

At the moment, the United States has a special domestic market that is fairly immune from outside events, as one would expect that they would happen in Canada, the United States’ major natural gas trading partner. This will change over time as U.S. natural gas markets get more connected with the world. The United States have some buffers during difficult gas shocks globally due to massive shale gas reserves. However, it could take a long time for these reserves to surge into the domestic markets to make up for the price increases.

Large profits can be made in exporting natural gas to places like China, Japan, South Korea, and Western Europe where gas prices are much higher. Over time those price differentials will decline because more LNG and piped gas will be flowing to the more profitable markets, hence putting pressure on prices. Global gas prices will tend to converge, but not entirely given different extraction, production, liquefaction and gasification prices.

With greater integration there are also new risks to consider. Some of these include potential attacks on major LNG facilities as natural gas becomes a more vital part of the world economy and some countries. There are also increased risks that as the global markets get more integrated in natural gas, events distant from the United States could affect prices in the United States much like what happens now with oil markets.

There are great profits to be made from exporting the potentially massive amounts of natural gas (mostly shale gas), from the United States into these newly developing world markets. (The greatest profits can be made in the first years of the development of these markets prior to the lowering of prices in Asia, Europe and higher priced areas as the markets get integrated.)