Bounty Hunters for Science

Fraud in scientific research is more common than we’d like to think. Such research can mislead entire scientific fields for years, driving futile and wasteful followup studies, and slowing down real scientific discoveries. To truly push the boundaries of knowledge, researchers should be able to base their theories and decisions on a more trustworthy scientific record.

Currently there are insufficient incentives to identify fraud and correct the record. Meanwhile, fraudsters can continue to operate with little chance of being caught. That should change: Scientific funders should establish one or more bounty programs aimed at rewarding people who identify significant problems with federally-funded research, and should particularly reward fraud whistleblowers whose careers are on the line.

Challenge and Opportunity

In 2023 it was revealed that 20 papers from Hoau-Yan Wang, an influential Alzheimer’s researcher, were marred by doctored images and other scientific misconduct. Shockingly, his research led to the development of a drug that was tested on 2,000 patients. A colleague described the situation as “embarrassing beyond words”.

There is a common belief that science is self-correcting. But what’s interesting about this case is that the scientist who uncovered Wang’s fraud was not driven by the usual academic incentives. He was being paid by Wall Street short sellers who were betting against the drug company!

This was not an isolated incident. The most notorious example of Alzheimer’s research misconduct – doctored images in Sylvain Lesné’s papers – was also discovered with the help of short sellers. And as reported in Science, Lesné’s “paper has been cited in about 2,300 scholarly articles—more than all but four other Alzheimer’s basic research reports published since 2006, according to the Web of Science database. Since then, annual NIH support for studies labeled ‘amyloid, oligomer, and Alzheimer’s’ has risen from near zero to $287 million in 2021.” While not all of that research was motivated by Lesné’s paper, it’s inconceivable that a paper with that many citations could not have had some effect on the direction of the field.

These cases show how a critical part of the scientific ecosystem – the exposure of faked research – can be undersupplied by ordinary science. Unmasking fraud is a difficult and awkward task, and few people want to do it. But financial incentives can help close those gaps.

Plan of Action

People who witness scientific fraud often stay silent due to perceived pressure from their colleagues and institutions. Whistleblowing is an undersupplied part of the scientific ecosystem.

We can correct these incentives by borrowing an idea from the Securities and Exchange Commission, whose bounty program around financial fraud pays whistleblowers 10-30% of the fines imposed by the government. The program has been a huge success, catching dozens of fraudsters and reducing the stigma around whistleblowing. The Department of Justice has recently copied the model for other types of fraud, such as healthcare fraud. The model should be extended to scientific fraud.

- Funder: Any U.S. government funding agency, such as NIH or NSF

- Eligibility: Research employees with insider knowledge from having worked in a particular lab

- Cost: The program should ultimately pay for itself, both through the recoupment of grant expenditures and through the impacts on future funding, including, potentially, the trajectory of entire academic fields.

The amount of the bounty should vary with the scientific field and the nature of the whistleblower in question. For example, compare the following two situations:

- An undergraduate whistleblower who identifies a problem in a psychology or education study that hardly anyone had cited, let alone implemented in the real world

- A graduate student or postdoc who calls out their own mentor for academic fraud related to influential papers on Alzheimer’s disease or cancer.

The stakes are higher in the latter case. Few graduate students or post-docs will ever be willing to make the intense personal sacrifice of whistleblowing on their own mentor and adviser, potentially forgoing approval of their dissertation or future recommendation letters for jobs. If we want such people to be empowered to come forward despite the personal stakes, we need to make it worth their while.

Suppose that one of Lesné’s students in 2006 had been rewarded with a significant bounty for direct testimony about the image manipulation and fraud that was occurring. That reward might have saved tens of millions in future NIH spending, and would have been more than worth it. In actuality, as we know, none of Lesné’s students or postdocs ever had the courage to come forward in the face of such immense personal risk.

The Office of Research Integrity at the Department of Health and Human Services should be funded to create a bounty program for all HHS-funded research at NIH, CDC, FDA, or elsewhere. ORI’s budget is currently around $15 million per year. That should be increased by at least $1 million to account for a significant number of bounties plus at least one full-time employee to administer the program.

Conclusion

Some critics might say that science works best when it’s driven by people who are passionate about truth for truth’s sake, not for the money. But by this point it’s clear that like anyone else, scientists can be driven by incentives that are not always aligned with the truth. Where those incentives fall short, bounty programs can help.

This memo produced as part of the Federation of American Scientists and Good Science Project sprint. Find more ideas at Good Science Project x FAS

Measuring Research Bureaucracy to Boost Scientific Efficiency and Innovation

Bureaucracy has become a critical barrier to scientific progress in America. An excess of management and administration efforts pulls researchers away from their core scientific work and consumes resources that could advance discovery. While we lack systematic measures of this inefficiency, the available data is troubling: researchers spend nearly half their time on administrative tasks, and nearly one in five dollars of university research budgets goes to regulatory compliance.

The proposed solution is a three-step effort to measure and roll back the bureaucratic burden. First, we need to create a detailed baseline by measuring administrative personnel, management layers, and associated time/costs across government funding agencies and universities receiving grant funding. Second, we need to develop and apply objective criteria to identify specific bureaucratic inefficiencies and potential improvements, based on direct feedback from researchers and administrators nationwide. Third, we need to quantify the benefits of reducing bureaucratic overhead and implement shared strategies to streamline processes, simplify regulations, and ultimately enhance research productivity.

Through this ambitious yet practical initiative, the administration could free up over a million research days annually and redirect billions of dollars toward scientific pursuits that strengthen America’s innovation capacity.

Challenge and Opportunity

Federally funded university scientists spend much of their time navigating procedures and management layers. Scientists, administrators, and policymakers widely agree that bureaucratic burden hampers research productivity and innovation, yet as the National Academy of Sciences noted in 2016 there is “little rigorous analysis or supporting data precisely quantifying the total burden and cost to investigators and research institutions of complying with federal regulations specific to the conduct of federally funded research.” This continues to be the case, despite evidence suggesting that federally funded faculty spend nearly half of their research time on administrative tasks, and nearly one in every five dollars spent on university research goes to regulatory compliance.

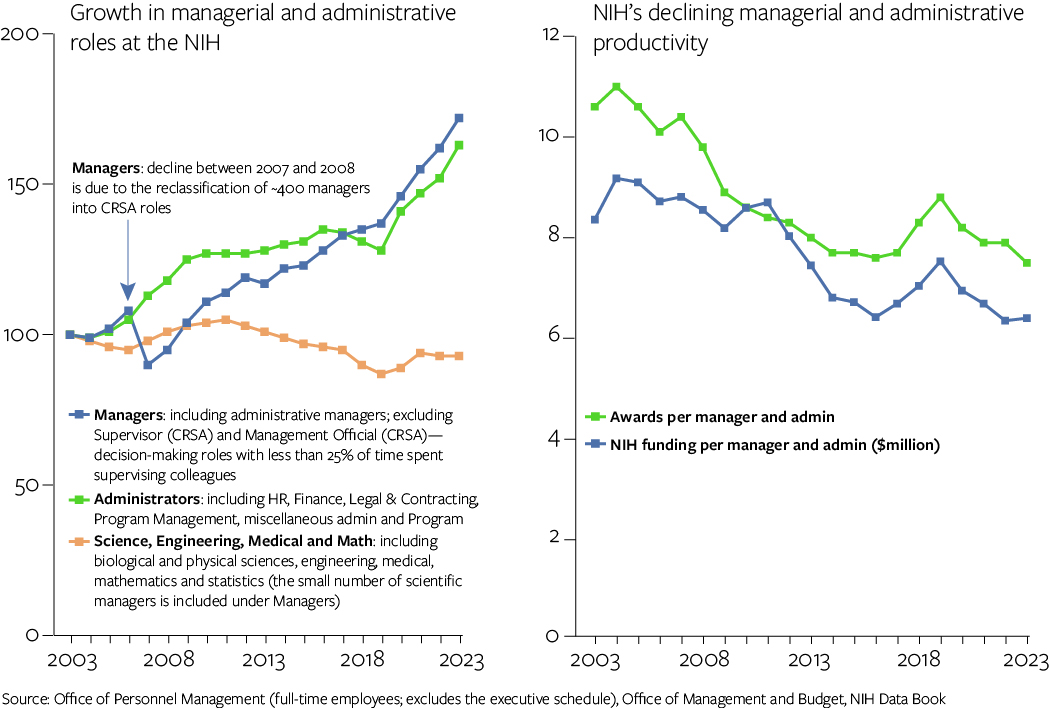

Judging by the steady rise in research administration requirements that face universities, the problem is getting worse. Federal rules and policies affecting research have multiplied ninefold in two decades— from 29 in 2004 to 255 in 2024, with half of the increase just in the last five years. It is no coincidence that the bureaucratic overhead is also expanding in funding agencies. At the National Institutes of Health (NIH), for instance, the growth of managers and administrators has significantly outpaced scientific roles and research funding activity (see figure).

The question is: just how much of universities’ $100 billion-plus annual research spend (more than half of it funded by the federal government) is hobbled by excess management and administration? To answer this, we must understand:

- Which bureaucratic activities are wasteful, or have a poor return on time and effort?

- How much time do bureaucratic activities take up, and what is the cost overall?

- Which activities are not required by the law or regulations, but are imposed by overly risk-averse legal counsel, compliance, and other administrators at agencies or universities?

- Which activities, rules, and processes should be eliminated or reimagined, and how?

- What portion of the overhead budget isn’t spent on research administration or management?

Plan of Action

The current administration aims to make government-funded research more efficient and productive. Recently, the director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) vowed to “reduce administrative burdens on federally funded researchers, not bog them down in bureaucratic box checking.” To that end, I propose a systematic effort that measures bureaucratic excess, quantifies the payoff from eliminating specific aspects of this burden, and improves accountability for results.

The president should issue an Executive Order directing the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to develop a Bureaucratic Burden report within 180 days of signing. The report should detail specific steps agencies will take to reduce administrative requirements. Agencies must participate in this effort at the leadership level, launching a government-wide effort to reduce bureaucracy. Furthermore, all research agencies should work together to develop a standardized method for calculating burden within both agencies and funded institutes, create a common set of policies that will streamline research processes, and establish clear limits on overhead spending to ensure full transparency in research budgets.

OMB and OSTP should create a cross-agency Research Efficiency Task Force within the National Science and Technology Council to conduct this work. This team would develop a shared approach and lead the data gathering, analysis, and synthesis using consistent measures across agencies. The Task Force’s first step would be to establish a bureaucratic baseline, including a detailed view of the managerial and administrative footprint within federal research agencies and universities that receive research funding, broken down into core components. The measurement approach would certainly vary between government agencies and funding recipients.

Key agencies, including the NIH, National Science Foundation, NASA, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Energy, should:

- Count personnel at each level—managers, administrators, and intramural scientists—along with their compensation;

- Document management layers from executives to frontline staff and supervisor ratios;

- Calculate time spent on administrative work by all staff, including researchers, to estimate total compliance costs and overhead.

- Task Force agencies should also hire an independent contractor(s) to analyze the administrative burden at a representative sample of universities. Through surveys and interviews, they should measure staffing, management structures, researcher time allocation, and overhead costs to size up the bureaucratic footprint across the scientific establishment.

Next, the Task Force should launch an online consultation with researchers and administrators nationwide. Participants could identify wasteful administrative tasks, quantify their time impact, and share examples of efficient practices. In parallel, agency leaders should submit to OMB and OSTP their formal assessment of which bureaucratic requirements can be eliminated, along with projected benefits.

Finally, the Task Force should produce a comprehensive estimate of the total cost of unnecessary bureaucracy and propose specific reforms. Its recommendations will identify potential savings from streamlining agency practices, statutory requirements, and oversight mechanisms. The Task Force should also examine how much overhead funding supports non-research activities, propose ways to redirect these resources to scientific research, and establish metrics and a public dashboard to track progress.

Some of this information may have already been gathered as part of ongoing reorganization efforts, which would expedite the assessment.

Within six months, the group should issue a public report that would include:

- A detailed estimate of the unnecessary costs of research bureaucracy.

- The cost gains from rolling back or adjusting specific burdens.

- A synthesis of harder-to-quantify benefits from these moves, such as faster approval cycles, better decision-making, and less conservatism in research proposals;

- A catalog of innovative research management practices, with a four-year timeline for studying and scaling them.

- A proposed approach for regular tracking and reporting on bureaucratic burden in science.

- A prioritized list of changes that each agency should make, including a clear timeline for making those changes and the estimated cost savings.

These activities would serve as the start of a series of broad reforms by the White House and research funding agencies to improve federal funding policies and practices.

Conclusion

This initiative will build an irrefutable case for reform, provide a roadmap for meaningful improvement, and create real accountability for results. Giving researchers and administrators a voice in reimagining the system they navigate daily will generate better insights and build commitment for change. The potential upside is enormous: millions of research days could be freed from paperwork for lab work, strengthening America’s capacity to innovate and lead the world. With committed leadership, this administration could transform how the US funds and conducts research, delivering maximum scientific return on every federal dollar invested.

This memo produced as part of the Federation of American Scientists and Good Science Project sprint. Find more ideas at Good Science Project x FAS

Reform Government Operations for Significant Savings and Improved Services

The federal government is dramatically inefficient, duplicative, wasteful, and costly in executing the common services required to operate. However, the new Administration has an opportunity to transform government operations to save money, improve customer experience, be more efficient and effective, consolidate, reduce the number of technology platforms across government, and have significantly improved decision-making power. This should be accomplished by adopting and transforming to a government-wide shared service business model involving the collective efforts of Congress, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), General Services Administration (GSA), and oversight agencies, and be supported by the President Management Agenda (PMA). In fact, this is a real opportunity for the newly created Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) to realize a true systemic transformation to a better and more streamlined government.

Challenge and Opportunity

The federal government is the largest employer in the world with many disparate mission-centric functions to serve the American people. To execute mission objectives, varied mission support functions are necessary, yet costly with many disconnected and inefficient layers added over many years. For example, a hiring action costs over $10,000 in the federal government vs. $4,000 in the private sector, and transactions such as paying an invoice cost hundreds of dollars compared to $1–2 in other sectors. Many support functions—such as travel management, FOIA management, background investigations, human resources, financial management, facilities management, and more — are equally costly and inefficient.

While these functions are critical to helping government programs achieve their mission, over many years they have grown costly and inefficient through high staffing ratios, duplication of technology platforms, disparate data systems, lack of standardization, and poor modernization. Congress focuses on individual agencies independently and not holistically on the opportunity for government-wide efficiency. Because improving operations has no mandate and GSA serves only in a coordinating role, agencies are free to approach operations any way they wish, resulting in a lack of standardization and the interoperability of systems. Many systems are still operating on extremely old software code, and the Administration and Congress lack government-wide data capacity to have the facts they need to govern. With a burdening national debt, we need to streamline government. To illustrate this opportunity, the federal government operates hundreds of human resources functions, whereas Walmart, the second largest U.S. employer with two million employees, operates just two, one for American and one for Europe.

There are several small examples in government demonstrating the ability to realize large cost savings and improved services. When the NASA shared services operations were established, it saved over $200 million through consolidation in their first several years. The consolidation of federal payroll services from 24 to 4 functions saved over $3.2 billion. The Technology CEO Council report “The Government We Need” estimated savings of over $1 trillion by the federal government moving to shared services. Commercial sector entities such as Johnson & Johnson saved approximately $2 billion in just two years.

Plan of Action

Over 85% of Fortune 500 companies and growing numbers of public sector governments around the world have committed to shared services as a mainstream business model. Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, Singapore, and others have realized significant reduction in cost and improved delivery. While shared services have been attempted in many forms since the 1980s in the federal government, implementation has been inconsistent and incomplete due to Congressional and Administration inattention. As part of past PMAs, a GSA Office of Shared Solutions and Performance (OSSPI) was established, along with a Technology Management Fund (TMF) to support modernization, yet little action has been taken to set goals and achieve results. Most government shared service centers operate on antiquated technology platforms, are at high risk of failure, and are in critical need of modernization.

Immediate legislative and executive action are necessary to enable robust, cross-government benefits. Transforming government into an efficient and effective operation will take time, measurement, and accountability. It’s important that this be done correctly and begin by building the requisite capacity to realize success and regularly report to the Administration and Congress. To ensure success, the following initial actions should be taken:

- Congress should make the consolidation of common service operating and business models statutorily mandatory and provide resources for GSA to conduct the appropriate analysis, design, and transformation to consolidated common services.

- The Administration should install the leadership with the responsibility, authority, and accountability for transforming government operations. This would be a Senate-confirmed Commissioner of Government Operations at GSA directing operations with policy authority resting with the OPM Deputy Director for Management (DDM).

- The Administration should enhance GSA/OSSPI to create an effective governance structure and increase their capacity and role. Governance would be structured through the DDM, the GSA Commissioner for government operations, the establishment of a Shared Services Advisory Board (SSAB) made up of agency Deputy Secretaries, and the inclusion of the existing chief operating councils. OSSPI would take on the lead role for transformation and operations oversight and have the staff resources and authority necessary to execute.

- Congress should direct and the Administration should conduct a deep analysis and design the most effective operating and business models. It is necessary to identify current resources, cost, and performance as well as benchmarks against other entities. This would be led by GSA and conducted by an independent, non-conflicted entity. Based on this analysis GSA would design optimized models, provide a clear business case, and prepare a transformation/modernization plan. The Commission would then approve and recommend further Congressional and/or executive action required to implement the transformation. In parallel, GSA would develop selected government staff and managers to participate in the analysis and transformation process.

- The Administration, through OMB and GSA, should implement the multi–year transformation and modernization effort and implement, measure, report results, and realize the requisite Return on Investment (ROI).

These initial activities should cost approximately $80 million and be cost-neutral by allocating funding from existing redundant operational and modernization efforts. This would fund cross-government analysis, GSA operations, government staff training, and transformation planning with an ROI to the taxpayer. Impacted federal staff would be retrained in new associated shared services roles and/or other mission support functions where needed.

Conclusion

The time to act boldly is now. The Administration needs to immediately begin reducing costs and improving services to taxpayers and government programs through the implementation of a shared services business model with strong leadership, a proven approach, and accountability to demonstrate results. Trillions of dollars fed back into supporting governments financial needs are necessary and attainable.