A Peer Support Service Integrated Into the 988 Lifeline

A peer support option should be integrated into the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline so that 988 service users can choose to connect with specialists based on a shared lived experience. As people and communities become more siloed, the risk of mortality and morbidity increases. Social connectedness is a critical protective factor. A peer support service would allow individuals to receive support built on a lived experience that is common to both the service user and the specialist. It should be free and easily accessible through phone call and text messaging. This service is especially timely, following the 2020 rollout of the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, as well as recent peer support initiatives at the federal and state levels.

While the efficacy of peer support is most known with mental illness, it has successfully helped a range of individuals including cancer patients, people experiencing homelessness, racial minorities, veterans, and formerly incarcerated people. The peer support service should provide support for all kinds of lived experience, including experiences with: disability resulting from poor physical or mental health, substance use, suicidal ideation, veteran-connected disability, financial insecurity, homelessness, domestic violence and family court, nonnuclear family structures or living alone, former incarceration, and belonging to racial or ethnic minority groups. The service should be a preventative intervention as well as complimentary assistance for those in recovery or treatment.

Challenge and Opportunity

The United States faces an “epidemic of loneliness and isolation.” While individuals from all backgrounds are afflicted, the most vulnerable and underserved members of society have suffered the most. A range of challenging circumstances cause this suffering, including poor physical or mental health, nontraditional living conditions, and historic inequality. Not having anyone who shares one’s lived experience is isolating. These challenging life circumstances take an emotional toll, and they become risk factors for a slew of physical and mental health conditions that increase morbidity and decrease life expectancy.

In addition to the social costs, these outcomes have an increasingly devastating economic impact. Health care costs are projected to account for 20% of the U.S. economy by 2031. Psychiatric hospitalizations are steadily increasing, and a shortage of psychiatric inpatient beds is rampant.

Social connectedness alleviates physical and mental burdens. Peer support offers a cost-effective intervention for prevention and recovery. It reduces spending on both physical and mental illnesses, and it reduces psychiatric hospitalizations, saving an average of $4.76 for every $1 spent on peer support. In a New York City-based peer support program, service users saved about $2,000 per month in Medicaid costs and had 2.9 fewer hospitalizations per year.

Telephone-based peer support has life-saving outcomes, too. Over telephone, peer support led to a 15% increase in women’s mammography screening rates, with the highest increase among women of low-to-middle income. Telephone-based peer support increased breastfeeding rates by 14% and reduced breastfeeding dissatisfaction by 10% among first-time mothers, and it led to a 10% change in diet among patients with heart disease. While peer support would not solve national crises of homelessness or rising healthcare costs, it would ease them by fostering community empowerment and self-reliance and reducing federal intervention.

In 2023, SAMHSA rolled out “National Model Standards for Peer Support Certification”. This guide provides recommendations for how each state can integrate its own “peer mental health workforce across all elements of the healthcare system.” In its current form, SAMHSA’s strategy targets lived experiences with substance use and mental health. A broader scope would assist and empower more underserved members of the community. Following the momentum of SAMHSA’s initiative, now is the most optimal time to integrate a peer support service into the 988 Lifeline.

Peer support exists in the U.S., but services are spread thin across private and nonprofit sectors. The Restoring Hope for Mental Health and Well-Being Act of 2022 authorized $1.7 trillion in funding until FY2027 for various health initiatives, including peer support mental health services. This funding relies on organizations and institutions to independently implement peer support services based on community needs. However, a fragmented system can result in underuse, limited accessibility, and a varied quality of service, with pockets of the United States lacking any service at all. It also poses privacy concerns about how individuals’ data are stored and used, as well as cybersecurity vulnerabilities with smaller organizations that may lack a robust security infrastructure.

A peer support service that is integrated into the 988 Lifeline would ensure that all Americans have equal access to a high-quality, confidential peer support network. The standardization of the 988 Lifeline is a prime example of successful implementation. Its transition from a 10-digit number to a three-digit dial led to a 33% average increase in in-state call volume over four months. Standardization shifted funding from primarily private and nonprofit initiatives and donations to stable public sector support. As a result, call pickup rates rose from 70% to 93%, and wait times dropped from 2 minutes 20 seconds to just 35 seconds.

The 988 Lifeline also adheres to privacy and confidentiality protocols in line with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Security Rule. Under these protocols, the 988 Lifeline retains minimal information about callers and texters, and this information stays private and securely stored. A peer support service with similar safeguards would help both service users and peer support workers (PSWs) feel safe when sharing sensitive information.

Peer support for mental health has gained traction recently. The National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI) offers peer-to-peer courses, although these are currently limited in their duration and available locations. Last year, Congress expressed an interest in peer support mental health services: a “Supporting All Students Act” was proposed in the Senate for “peer and school-based mental health support.” This endeavor especially targets the escalating suicide crisis among youths in the form of a peer-to-peer suicide prevention. The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction also recently introduced Peer-to-Peer Suicide Prevention Grants. The federal and state-level governments clearly recognize the value of peer support work. Still, they underutilize its potential.

Loneliness and isolation are at an all-time high in the United States. However, they stem from a multitude of causes. An empathic connection with a peer who has lived the same experience has immense potential for healing and recovery in both the PSW and the service user. The 988 Lifeline should include an integrated peer support service for both mental health and a broad range of lived experiences. While there exist some peer support services for conditions not related to mental health, these are not standardized or easily accessible to the entire American population. Many peer-operated warmlines (i.e., support lines) exist. However, they are spread across dozens of phone numbers and websites with varied and limited sources of funding. A single peer support service integrated into the 988 Lifeline would make peer support universally available. This service would address the emotional toll that accompanies a wide range of challenging life circumstances.

In short, a peer support service integrated into the 988 Lifeline would make the efforts of existing peer support organizations even more effective as it would:

- Standardize training, quality of care, and confidentiality,

- Expand the kinds of lived experience that are available for peer support, and

- Maximize the distribution of high-quality services across the U.S., with a focus on reaching high-risk populations.

Action Plan

The peer support service should begin by covering only a few kinds of lived experiences. After this implementation, the service should be expanded to cover a broader range of experiences.

Recommendation 1. Create a Peer Support Task Force (PSTF).

A PSTF should be established within SAMHSA. The secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should work with SAMHSA’s assistant secretary for mental health and substance use to establish this temporary task force.

The PSTF should lead the implementation of the peer support service, acting as an interagency task force that coordinates with partners across the public, private, and nonprofit sectors. This partnership will ensure that different lived experiences are accounted for and that existing resources are used effectively. The PSTF should collaborate with federal agencies, including the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Indian Health Service (IHS), as well as with advocacy organizations like NAMI and the American Cancer Society that champion the needs of people with specific lived experiences.

The PSTF should be charged with the following recommendations to start.

Recommendation 2. Integrate a peer support option into the 988 Lifeline.

Under the authority of the PSTF, integrating a peer support option into the 988 Lifeline could bypass additional Congressional action.

In the first pass, the integrated peer support option should cover only a few kinds of lived experiences (e.g., suicide and behavioral crises, veteran-connected disability).

- Before scaling the peer support service across the United States, the PSTF should implement a pilot program to test and refine protocols. The PSTF should select 988 Lifeline centers in states that already have a strong peer support program, and it should pilot peer support call and text services. The pilot program should select a few peer support needs to test first (e.g., suicide and behavioral crises, veteran-connected disability), as a narrow scope will be easier to assess for the first pass.

- The PSTF should then incorporate feedback from this pilot program as it scales up and integrates a peer support option into the nationwide 988 Lifeline.

- The PSTF should coordinate with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to add a caller menu option for peer support into the 988 Lifeline. (E.g., “Press 4 for peer support.”)

- The PSTF should coordinate with the FCC and U.S. Digital Service to implement a telephone triage, so the service user can submit a request for a specific kind of peer support and then be routed to a PSW on shift who has a lived experience that best matches the submitted request.

- The PSTF should facilitate the 988 Lifeline’s partnership with existing local and national peer support organizations and warmlines. Partnering with these existing organizations would bolster the 988 Lifeline’s capacity to provide peer support. Furthermore, states that already have a strong peer support certification in place could easily integrate their trained PSWs into the 988 Lifeline services using their existing infrastructure and expertise.

- The PSTF should coordinate with the FCC to incorporate a peer support text messaging option within the 988 Lifeline’s text and chat services. (For example, service users could text “PEER” to 9-8-8 and be routed to a PSW on shift.)

- The PSTF should implement a public campaign to the general public clarifying that the 988 Lifeline will remain as a suicide and crisis hotline, but it will also provide access to broader peer support services. The available peer support services should be clearly outlined on the 988 Lifeline website.

PSWs should work in call centers alongside 988 Lifeline phone and text specialists.

Recommendation 3. Develop an action plan to fund and sustain the integration of the peer support service.

The peer support service would need funding to become integrated into the 988 Lifeline. The government has recently approved funds for mental health initiatives, such as with the Restoring Hope for Mental Health and Well-Being Act of 2022. In 2023, HHS announced an additional $200 million in funding for the 988 Lifeline, but overall, HHS has granted almost $1.5 billion in total toward the 988 Lifeline. Similar avenues of funding should help jumpstart the integration of the peer support service.

For continued maintenance, fees for the peer support service should apply in a similar fashion to 9-1-1. That is, service users should not pay each time they access the 988 Lifeline or its integrated peer support service. Some U.S. states have already passed 9-8-8 implementation legislation that allows a monthly flat fee to be collected through telephone and wireless service providers, as permitted in the “National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020”. The remaining states should be encouraged to pass similar legislation. The fee should remain in an account that is spent only for the maintenance of the 988 Lifeline and peer support services. If a fee is collected, then the FCC should provide an annual report on these fees and their usage.

Funding for the peer support service’s integration into the 988 Lifeline would entail the following:

- Maintenance of the peer support service

- Financial compensation for trainers who will train and mentor the PSWs

- Recruitment of trainers and PSWs

- The development of training resources for PSWs

Recommendation 4. Establish state-level standardized peer support training and certification.

PSWs should learn skills that are commonly taught to 988 Lifeline specialists, including active listening and recovery-oriented language. They should learn how to share their own stories, navigate challenging conversations, maintain boundaries, and self-care. Their training should be standardized at the state level, and it should be based on the “National Model Standards for Peer Support Certification” established by SAMHSA.

While most U.S. states have some version of peer support certification for mental health and/or substance use recovery, the PSTF should work with advocacy organizations to ensure that the state-level standardized training accounts for the peer support needs and demographics of each state. The peer support training should address the needs of people with a diverse range of lived experiences. Peer support needs can also be studied using caller outcome data that are recorded by 988 Lifeline specialists.

The PSTF should recruit trainers who will train and mentor the PSWs. To start, the PSTF should liaise within SAMHSA and with existing peer support organizations to coordinate this recruitment.

Recommendation 5. Establish a nation-wide system for the recruitment and training of PSWs.

Recruit individuals who would like to use their own lived experience to help other community members. Recruitment should occur through hospitals, clinics, as well as peer-run and community-based organizations to maximize recruitment pathways.

Current 988 Lifeline phone and text specialists could also be good candidates for the peer support service. Many are motivated by their own lived experiences and are already trained to handle calls across multiple helplines. 988 Lifeline specialists are instructed to focus on the service user seeking help and not share about themselves. However, specialists’ own lived experiences––if they are comfortable sharing them––represent untapped potential.

Once recruited, individuals who are training to become PSWs should attend live training sessions online with a peer cohort.

Recommendation 6. Expand the peer support service to cover a diverse range of lived experiences.

After successfully establishing the peer support service, it should be expanded upon to provide support for a broad and diverse range of lived experiences. The available peer support services should continue to be updated and outlined on the 988 Lifeline website.

Conclusion

A peer support service should be integrated into the 988 Lifeline. A service that caters to all kinds of lived experience paves way for a more empowered and self-reliant community. It fosters a societal mindset of helping each other based on shared lived experience in an empathic and healthy way. Peer support empowers both the PSW and the service user. While the service user finds empathy and understanding, the PSW finds a renewed sense of purpose and confidence. In this way, peer support would alleviate loneliness and isolation that result from a variety of causes while instilling longer-term resilience into the community.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

A service user refers to any individual who uses the peer support service for assistance.

Peer support work can be empowering and healing for those in recovery. However, as with any emotionally challenging work, PSWs benefit from ongoing support and supervision. Some interactions can be draining, especially if they hit too close to home. It is common for 988 Lifeline call centers to have a trained staff member, such as a psychologist or therapist, on call for such situations. A PSW could use this resource to debrief or process as needed. Additionally, during recruitment, PSW candidates should be screened to ensure they are comfortable speaking about their own lived experience and helping others who are going through the same experience.

Most PSWs would be compensated in the same way as their 988 Lifeline call and text specialist counterparts. They would be compensated with rigorous ongoing training, support, and resources for recovery and self-care in return for their time. They would also benefit from a social support system of fellow PSWs. Some individuals who may be ideal candidates for peer support work may struggle to find employment and health insurance. They will be less likely to volunteer if they do not have a living wage. To maximize the range of lived experiences available, certain individuals should be eligible for financial compensation.

A service user’s phone call or text should be routed to a 988 Lifeline peer support operator or telephone triage, where the service user is asked to say aloud (or type) what kind of support they are searching for (e.g., “I want to speak with someone who has been in prison.”) Then, the service user’s call (or text) would be routed to a PSW (under an alias) anywhere in the United States who 1) is currently on shift and 2) has a lived experience that is closest to the service user’s request. Each PSW would have associated keywords, such as “former incarceration,” “PTSD,” or “living alone,” which means that they are trained to connect with any service user about those lived experiences. The PSW would follow the service user’s lead in the conversation, and the PSW could share parts of their own lived experience when appropriate.

Text messaging can be more accessible than a phone line for youths and people with disabilities. The 988 Lifeline includes a text messaging option for this same reason.

It is true that both the regular 988 Lifeline and peer support service would provide resources and emotional support. By incorporating peer support into the 988 Lifeline, existing local and national peer support organizations would be eligible to partner with the 988 Lifeline and bolster its capacity to provide peer support. This endeavor will help with some staffing concerns. Furthermore, the peer support service would cover a diverse range of lived experiences extending beyond mental health. Therefore, more individuals may be motivated to join the 988 Lifeline staff to share their unique lived experience and help others who feel the same way.

Integrating a versatile peer support service into the 988 Lifeline transforms the latter into a service that every single American can use. (Every American has some unique lived experience.) The service’s versatility may help incentivize the remaining states to pass legislation to collect a 988 Lifeline fee through telephone and wireless service providers.

Finally, peer support is a cost-effective, preventative intervention. It should help remove the burden on other federal services, thereby reducing overall spending in time.

After implementing the action plan outlined in this memo, a subsequent memo should outline how to integrate peer support work into the community in person and on a large scale. Incorporating peer support into the 988 Lifeline would show its effectiveness to the public, policymakers, and healthcare professionals. This credibility would bolster endeavors to integrate peer support work into community settings throughout the country (e.g., behavioral health centers, hospitals and emergency rooms, and community clinics). These endeavors could also lead to professionalizing peer support, so PSWs can be reimbursed through Medicaid programs and health insurance.

Antitrust in the AI Era: Strengthening Enforcement Against Emerging Anticompetitive Behavior

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) has revolutionized business practices, enabling companies to process vast amounts of data and automate complex tasks in ways previously unimaginable. However, while AI has gained much praise for its capabilities, it has also raised various antitrust concerns. Among the most pressing is the potential for AI to be used in an anticompetitive manner. This includes algorithms that facilitate price-fixing, predatory pricing, and discriminatory pricing (harming the consumer market), as well as those which enable the manipulation of wages and worker mobility (harming the labor market). More troubling perhaps is the fact that the overwhelming majority of the AI landscape is controlled by just a few market players. These tech giants—some of the world’s most powerful corporations—have established a near-monopoly over the development and deployment of AI. Their dominance over necessary infrastructure and resources makes it increasingly challenging for smaller firms to compete.

While the antitrust enforcement agencies—the FTC and DOJ—have recently begun to investigate these issues, they are likely only scratching the surface. The covert and complex nature of AI makes it difficult to detect when it is being used in an anticompetitive manner. To ensure that business practices remain competitive in the era of AI, the enforcement agencies must be adequately equipped with the appropriate strategies and resources. The best way to achieve this is to (1) require the disclosure of AI technologies during the merger-review process and (2) reinforce the enforcement agencies’ technical strategy in assessing and mitigating anticompetitive AI practices.

Challenge & Opportunity

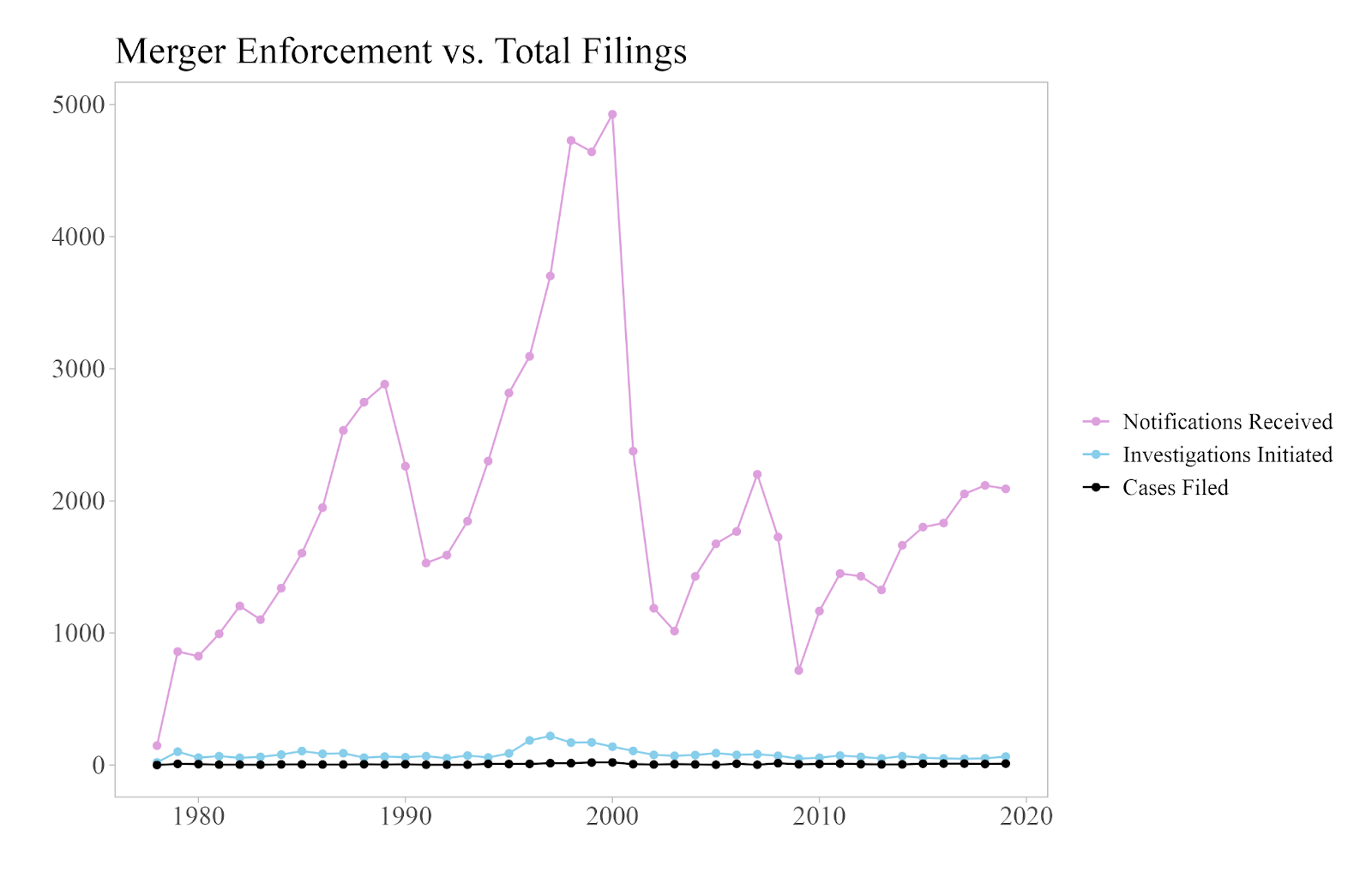

Since the late 1970s, antitrust enforcement has been in decline, in part due to a more relaxed antitrust approach put forth by the Chicago school of economics. Both the budgets and the number of full-time employees at the enforcement agencies have steadily decreased, while the volume of permitted mergers and acquisitions has risen (see Figure 1). This resource gap has limited the ability of the agencies to effectively oversee and regulate anticompetitive practices.

Changing attitudes surrounding big business, as well as recent shifts in leadership at the enforcement agencies—most notably President Biden’s appointment of Lina Khan to FTC Chair—have signaled a more aggressive approach to antitrust law. But even with this renewed focus, the agencies are still not operating at their full potential.

This landscape provides a significant opportunity to make some much-needed changes. Two areas for improvement stand out. First, agencies can make use of the merger review process to aid in the detection of anticompetitive AI practices. In particular, the agencies should be on the look-out for algorithms that facilitate price-fixing, where competitors use AI to monitor and adjust prices automatically, covertly allowing for tacit collusion; predatory pricing algorithms, which enable firms to undercut competitors only to later raise prices once dominance is achieved; and dynamic pricing algorithms, which allow firms to discriminate against different consumer groups, resulting in price disparities that may distort market competition. On the labor side, agencies should screen for wage-fixing algorithms and other data-driven hiring practices that may suppress wages and limit job mobility. Requiring companies to disclose the use of such AI technologies during merger assessments would allow regulators to examine and identify problematic practices early on. This is especially useful for flagging companies with a history of anticompetitive behavior or those involved in large transactions, where the use of AI could have the strongest anticompetitive effects.

Second, agencies can use AI to combat AI. Research has demonstrated that AI can be more effective in detecting anticompetitive behavior than other traditional methods. Leveraging such technology could transform enforcement capabilities by allowing agencies to cover more ground despite limited resources. While increasing funding for these agencies would be requisite, AI nonetheless provides a cost-effective solution, enhancing efficiency in detecting anticompetitive practices, without requiring massive budget increases.

The success of these recommendations hinges on the enforcement agencies employing technologists who have a deep understanding of AI. Their knowledge on algorithm functionality, the latest insights in AI, and the interplay between big data and anticompetitive behavior is instrumental. A detailed discussion of the need for AI expertise is covered in the following section.

Plan Of Action

Recommendation 1. Require Disclosure of AI Technologies During Merger-Review.

Currently, there is no formal requirement in the merger review process that mandates the reporting of AI technologies. This lack of transparency allows companies to withhold critical information that may help agencies determine potential anticompetitive effects. To effectively safeguard competition, it is essential that the FTC and DOJ have full visibility of businesses’ technologies, particularly those that may impact market dynamics. While the agencies can request information on certain technologies further in the review process, typically during the second request phase, a formalized reporting requirement would provide a more proactive approach. Such an approach would be beneficial for several reasons. First, it would enable the agencies to identify anticompetitive technologies they might have otherwise overlooked. Second, an early assessment would allow the agencies to detect and mitigate risk upfront, rather than having to address it post-merger or further along in the merger review process, when remedies may be more difficult to enforce. This is particularly applicable with regard to deep integrations that often occur between digital products post-merger. For instance, the merger of Instagram and Facebook complicated the FTC’s subsequent efforts to challenge Meta. As Dmitry Borodaenko, a former Facebook engineer, explained:

“Instagram is no longer viable outside of Facebook’s infrastructure. Over the course of six years, they integrated deeply… Undoing this would not be a simple task—it would take years, not just the click of a button.”

Lastly, given the rapidly evolving nature of AI, this requirement would help the agencies identify trends and better determine which technologies are harmful to competition, under what circumstances, and in which industries. Insights gained from one sector could inform investigations in other sectors, where similar technologies are being deployed. For example, the DOJ recently filed suit against RealPage, a property management software company, for allegedly using price-fixing algorithms to coordinate rent increases among competing landlords. The case is the first of its kind, as there had not been any previous lawsuit addressing price-fixing in the rental market. With this insight, however, if the agencies detect similar algorithms during the merger review process, they would be better equipped to intervene and prevent such practices.

There are several ways the government could implement this recommendation. To start, The FTC and DOJ should issue interpretive guidelines specifying that anticompetitive effects stemming from AI technologies are within the purview of the Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) Act, and that accordingly, such technologies should be disclosed in the pre-merger notification process. In particular, the agencies should instruct companies to report detailed descriptions of all AI technologies in use, how they might change post-merger, and their potential impact on competition metrics (e.g., price, market share). This would serve as a key step in signaling to companies that AI considerations are integral during merger review. Building on this, Congress could pass legislation mandating AI disclosures, thereby formalizing the requirement. Ultimately, in a future round of HSR revisions, the agencies could incorporate this mandate as a binding rule within the pre-merger framework. To avoid unnecessary burden on businesses, reporting should only be required when AI plays a significant role in the company’s operations or is expected to post-merger. What constitutes a ‘significant role’ should be left to the discretion of the agencies but could include AI systems central to core functions such as pricing, customer targeting, wage-setting, or automation of critical processes.

Recommendation 2. Reinforce the FTC and DOJ’s Technical Strategy in Assessing and Mitigating Anticompetitive AI Practices.

Strengthening the agencies’ ability to address AI requires two actions: integrating computational antitrust strategies and increasing technical expertise. A wave of recent research has highlighted AI as a powerful tool in helping detect anticompetitive behavior. For instance, scholars at the Stanford Computational Antitrust Project have demonstrated that methods such as machine learning, natural language processing, and network analysis can assist with tasks, ranging from uncovering collusion between firms to distinguishing digital markets. While the DOJ has already partnered with the Project, the FTC could benefit by pursuing a similar collaboration. More broadly, the agencies should deepen their technical expertise by expanding workshops and training with AI academic leaders. Doing so would not only provide them with access to the most sophisticated techniques in the field, but would also help bridge the gap between academic research and real-world implementation. Examples may include the use of machine learning algorithms to identify price-fixing and wage-setting; sentiment analysis, topic modeling, and other natural language processing tools to detect intention to collude in firm communications; or reverse-engineering algorithms to predict outcomes of AI-driven market manipulation.

Leveraging such computational strategies would enable regulators to analyze complex market data more effectively, enhancing the efficiency and precision of antitrust investigations. Given AI’s immense power, only a small—but highly skilled—team is needed to make significant progress. For instance, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) recently stood up a Data, Technology and Analytics unit, whereby they implement machine learning strategies to investigate various antitrust matters. For the U.S. agencies to facilitate this, the DOJ and FTC should hire more ML/AI experts, data scientists, and technologists, who could serve several key functions. First, they could conduct research on the most effective methods for detecting collusion and anticompetitive behavior in both digital and non-digital markets. Second, based on such research, they could guide the implementation of selected AI solutions in investigations and policy development. Third, they could perform assessments of AI technologies, evaluating the potential risks and benefits of AI applications in specific markets and companies. These assessments would be particularly useful during merger review, as previously discussed in Recommendation 1. Finally, they could help establish guidelines for transparency and accountability, ensuring the responsible and ethical use of AI both within the agencies and across the markets they regulate.

To formalize this recommendation, the President should submit a budget proposal to Congress requesting increased funding for the FTC and DOJ to (1) hire technology/AI experts and (2) provide necessary training for other selected employees on AI algorithms and datasets. The FTC may separately consider using its 6(b) subpoena powers to conduct a comprehensive study of the AI industry or of the use of AI practices more generally (e.g., to set prices or wages). Finally, the agencies should strive to foster collaboration between each other (e.g., establishing a Joint DOJ-FTC Computational Task Force), as well as with those in academia and the private sector, to ensure that enforcement strategies remain at the cutting edge of AI advancements.

Conclusion

The nation is in the midst of an AI revolution, and with it comes new avenues for anticompetitive behavior. As it stands, the antitrust enforcement agencies lack the necessary tools to adequately address this growing threat.

However, this environment also presents a pivotal opportunity for modernization. By requiring the disclosure of AI technologies during the merger review process, and by reinforcing the technical strategy at the FTC and DOJ, the antitrust agencies can strengthen their ability to detect and prevent anticompetitive practices. Leveraging the expertise of technologists in enforcement efforts can enhance the agencies’ capacity to monitor levels of competition in markets, as well as allow them to identify patterns between certain technologies and violations of antitrust.

Given the rapid pace of AI advancement, a proactive effort triumphs over a reactive one. Detecting antitrust violations early allows agencies to save both time and resources. To protect consumers, workers, and the economy more broadly, it is imperative that the FTC and DOJ adapt their enforcement strategies to meet the complexities of the AI era.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Using Pull Finance for Market-driven Infrastructure and Asset Resilience

The incoming administration should establish a $500 million pull-financing facility to ensure infrastructure and asset resiliency with partner nations by catalyzing the private sector to develop cutting-edge technologies. The increasing frequency of extreme weather events, which caused over $200 billion in global economic losses in 2023, is disrupting global supply chains and exacerbating migration pressures, particularly for the U.S. Investing in climate resilience abroad offers a significant opportunity for U.S. businesses in technology, engineering, and infrastructure, while also supporting job creation at home.

Pull-finance mechanisms can maximize the efficiency and impact of U.S. investments, fostering innovation and driving sustainable solutions to address global vulnerabilities. Unlike traditional funding which second-guesses the markets by supporting only selected innovators, pull financing drives results by relying on the market to efficiently allocate resources to achievement, fostering competition and rewarding the most impactful solutions. Managed and steered by the U.S. government, the pull-financing facility would fund infrastructure and asset resiliency results delivered by the world’s cutting-edge innovators, mitigating the effects of extreme weather events and ultimately supporting U.S. interests abroad.

Challenge and Opportunity

The increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events pose significant risks to global economic stability, with direct implications for U.S. interests. In 2023 alone, natural disasters caused over $200 billion in global economic losses with much of the damage concentrated in regions critical to global supply chains. U.S. businesses that depend on these supply chains face rising costs and disruptions, which translate into higher costs for U.S. businesses and consumers, undermining economic competitiveness.

Beyond the economic dimension, these vulnerabilities exacerbate socio-political pressures. Climate-induced displacement is accelerating, with 32.6 million people internally displaced by disasters in 2022. Most displaced individuals that cross borders migrate to countries neighboring their own, which are ill-equipped to handle the influx, often further destabilizing fragile states. For the U.S., this translates into increased migration pressures at its southern border, where natural disasters are already a driving force behind migration from Central America. Addressing these root causes through proactive resiliency investments abroad would reduce long-term strain on the U.S. and bolster stability in strategically important regions.

In addition to economic and social risks, resilience is now a key front in global competition. The People’s Republic of China has rapidly expanded its influence in developing nations through initiatives like the Belt and Road, financing over $200 billion in energy and infrastructure projects since 2013. A significant portion of these projects focus on resiliency investments, enabling China to position itself as a partner of choice for nations with asset and infrastructure exposure. This growing influence comes at the expense of U.S. global leadership.

In the context of these challenges, it is especially concerning that much of the U.S.’s existing spending may not be achieving the results it could. A recent audit of USAID climate initiatives highlights concerns around limited transparency and effectiveness in its development funding. The inefficient use of this funding is leaving opportunities on the table for U.S. businesses and workers. Global investments in adaptation and resiliency are projected to reach $500 billion annually by 2050. Resilience projects abroad could open substantial markets for American engineering, technology, and infrastructure firms. For instance, U.S.-based companies specializing in resilient agriculture, flood defense systems, advanced irrigation technologies, and energy infrastructure stand to benefit from increased demand. Domestically, the manufacturing and export of these solutions could generate significant economic activity, supporting high-quality jobs and revitalizing industrial sectors.

Pull finance presents an opportunity to increase the cost effectiveness of resiliency funding—and ensure this funding achieves U.S. interests. Pull finance mechanisms like results-based financing and Advance Market Commitments (AMC) reward successful solutions that meet specific criteria, promoting private sector engagement and market-driven problem-solving. Unlike traditional “push” financing, which funds chosen teams or projects directly, pull financing sets a goal and allows any innovator who reaches it to claim the reward, fostering competitive problem-solving without pre-selected winners. This approach includes various mechanisms – such as prize challenges, milestone payments, advance market commitments, and subscription models – each suited to different issues and industries.

Pull financing is particularly effective for addressing complex challenges with unclear or emerging solutions, or in areas with limited commercial incentives. It has proven successful in various contexts, such as the first Trump Administration’s rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines through Operation Warp Speed and GAVI’s introduction of the pneumococcal vaccine in low-income countries. These initiatives highlight how pull financing can stimulate breakthrough innovations that efficiently address immediate needs in collaboration with private actors through effective incentives.

Pull finance can be used to efficiently advance infrastructure and asset resilience goals while also providing opportunities for U.S. innovators and industry. By stimulating demand for critically needed technologies for development like resilient seeds and energy storage solutions, as detailed in Box 1, well-designed pull finance would help link U.S. technology innovators to addressing needs of U.S. partners. As such, pull finance can play a critical role in positioning the U.S. as a partner of first choice for countries seeking to access U.S. innovation to meet resilience needs.

What would the design of a pull financing mechanism look like in practice?

Resilient Seeds

Agriculture in Africa is highly susceptible to extreme weather events, with limited adoption of effective farming technologies. Developing new seed varieties capable of withstanding these events and optimizing resource use has the potential to yield significant societal benefits.

While push financing can support the development of resource-efficient and productive seeds, it often lacks the ability to ensure they meet essential quality standards, like flavor and appearance, and are user-friendly across farming, transport and marketing stages. In contrast, pull financing can effectively incentivize private sector innovation across all critical dimensions, including end-user take-up.

A pull mechanism for resilient seeds, using a milestone payment mechanism, could cover a portion of R&D costs initially, with additional payments tied to successful lab trials. Depending on the obstacles to scaling – whether they arise from the innovator/distributor side or the farmer side – a small per-user payment to the innovator or per-user subsidy could help sustain market demand.

The design and scale of a pull financing mechanism to promote the rollout of new seeds and crop varieties will largely depend on the market readiness of the various seed types involved. Establishing effective pull mechanisms for seed development is estimated to cost between $50 million and $100 million, aiming for significant outreach to farmers. Along with supporting improved livelihoods for farmers, this small investment would open opportunities for U.S. technology innovators and companies.

Pull Finance Initiative for Infrastructure and Asset Resiliency in the Caribbean

The Caribbean is one of the regions most vulnerable to extreme weather events, making it critical to engage the private sector in developing and adopting technologies suited to Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Challenges such as limited demand and high costs hinder innovation and investment in these small markets, leaving key areas like agriculture and access underserved. Overcoming these market failures requires innovative approaches to create sustainable incentives for private sector involvement.

Pull finances offers a promising solution to drive resiliency in SIDS. By tying payments to measurable outcomes, this approach will incentivize the development and deployment of technologies that might otherwise remain inaccessible.

For example, pull finance could be used to stimulate the creation of energy storage solutions designed to withstand extreme weather conditions in remote areas. This could be help address the critical needs of SIDS’ such as Guyana which face energy security challenges linked to extreme weather conditions, especially in remote and dispersed areas. Energy storage technologies exist, but companies are not motivated to invest in tailored innovation for local needs because end-users cannot pay prices that compensate for innovation efforts. Pull finance could address this by committing to purchase an amount large enough that nudges companies to develop a tailored product, without raising market prices. Success would require partnerships with local SMEs, caps in installation costs, and specifications on storage capacity, along with relevant technology partners such as those in the U.S.. This approach would support immediate adaptation needs and lay the foundation for sustainable, market-driven solutions that ensure long-term resilience for SIDS.

Plan of Action

The new administration should establish a dedicated pull-financing facility to accelerate the scale-up and deployment of development solutions with partner nations. In line with other major U.S. climate initiatives, this facility could be managed by USAID’s Bureau for Resilience, Environment and Food Security (REFS), with significant support from USAID’s Innovation, Technology, and Research (ITR) Hub, in partnership with the U.S. Department of State. By leveraging USAID’s deep expertise in development and SPEC’s strategic diplomacy, this collaboration would ensure the facility addresses LMIC-specific needs while aligning with broader U.S. objectives.

The recent audit of USAID climate initiatives referenced above highlights concerns on the limited transparency and effectiveness in its climate funding. Thus, we recommend that USAID assesses the impact of its climate spending under the 2020-2024 administration and reallocates a portion of funds from less effective or stalled initiatives to this new facility. We recognize that it may be challenging to quickly identify $500 million in underperforming projects to close and reassign. Therefore, in addition to reallocating existing resources, we strongly recommend appealing to new funding for this initiative. This approach will ensure the new facility has the financial backing it needs to drive meaningful outcomes. Additional resources could also be sourced from large multilateral organizations such as the World Bank.

To enhance the facility’s impact, we recommend the active participation of agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOOA), particularly through the Climate and Societal Interactions Division (CSI) in the Steering Committee,

We propose that this facility draw on the example of the UK’s planned Climate Innovation Pull Facility (CIPF), a £185 million fund which aims to fund development-relevant pull finance projects in LMICs such as those proposed by the Center for Global Development and Instiglio. This can be achieved through the following steps:

Recommendation 1. Establish the pull-finance facility, governance and administration with an initial tranche of $500 million.

The initiative proposes establishing a pull-finance facility with an initial fund of $500 million. This facility will be overseen by a steering board chaired by USAID and comprising senior representatives from USAID, the State Department, NOOA , which will set the strategic direction and make final project selections.

A facility management team, led by USAID, will be responsible for ensuring the successful implementation of the facility, including the selection and delivery of 8 to 16 projects. The final number of projects will depend on the launch readiness of prioritized technologies and their potential impact, with the selection process guided by criteria that align with the facility’s strategic goals. The facility management team will also be responsible for contracting with project and evaluation partners, compliance with regulations, risk management, monitoring and evaluation, as well as payouts. Additionally, the facility management team will provide incubation support for selected initiatives, including technical consultations, financial modeling, contracting expertise, and feasibility assessments.

Designing pull financing mechanisms is complex and requires input from specialized experts, including scientists, economists, and legal advisors, to identify suitable market gaps and targets. An independent Technical Advisory Group (TAG) led by USAID and comprised of such experts should be established to provide technical guidance and quality assurance. The TAG will identify priority resilience topics, such as reducing crop-residue burning or developing resilient crops. It will also focus on sectors where the U.S. can enhance its global competitiveness, which faces high upfront costs and risks. Additionally, the TAG will be responsible for technical review and recommendations of the shortlisted project proposals to inform final selection, as well as provide general advice and challenge to the facility management team and steering board.

We suggest starting with $500 million as the minimum required to be credible and relevant as well as responsive to the scale of global need. Further, experience shows that pull mechanisms need to be of sufficient scale to sustainably shift markets. For instance, GAVI’s pneumococcal vaccine AMC entailed a $1.5 billion commitment and Frontier’s carbon capture AMC likewise entails over $1 billion in commitments.

Recommendation 2. Set up a performance management system to measure, assess and ensure impact.

The U.S. pull financing facility will implement a robust monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) framework to track and enhance its impact and drive ongoing improvement through feedback and learning.

The facility manager will develop a logical framework (logframe) that includes key performance indicators (KPIs) and a progress and risk dashboard to track monthly performance. These tools will enable effective monitoring of progress, assessment of impact, and proactive risk management, allowing for quick responses to unexpected challenges or underperformance.

Monthly check-ins with an independent evaluation partner, along with oversight from a dedicated MEL committee, will ensure consistent and rigorous evaluation as well as continuous learning. Additionally, knowledge management and dissemination activities will facilitate the sharing of insights and best practices across the program.

Recommendation 3. Establish a knowledge management hub to facilitate the sharing of results and insights and ensure coordination across pull-financing projects.

The hub will work closely with community partners and stakeholders – such as industry and tech leaders and manufacturers – in areas like resiliency-focused finance and innovation to build strong support and develop resources on essential topics, including the effectiveness of pull financing and optimal design strategies. Additionally, the hub will promote collaboration across projects focused on similar technological and production advancements, generating synergies that enhance their collective impact and benefits.

Once the proof of concept is established through clear evidence and learning, the facility will likely secure further stakeholder buy-in and attract additional funding for a scale up phase covering a larger portfolio of projects.

Conclusion

The federal government should establish a $500 million pull-financing facility to accelerate technologies for resilience in the face of growing development challenges. This initiative will unlock high-return investments and increase cost effectiveness of resiliency spending, driving economic and geopolitical goals. Managed and steered by USAID and the State Department, with support from NOOA, the facility would foster breakthroughs in critical areas like resilient infrastructure, energy, and technology, benefiting both U.S. businesses and our international partners. By investing strategically, the U.S. can ensure both national and global stability.

The authors thank FAS for the reviews and feedback, along with Ranil Dissanayake, Florence Oberholtzer, and Laura Mejia Villada for their valuable contribution to this piece.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Pull financing mechanisms, such as prize competitions, milestone payments, and Advanced Market Commitments (AMCs) often face regulatory and legal challenges due to their dependency on successful outcomes for funding disbursement (CGD, 2021; CGD, 2023). First, it can make cashflow management challenging as federal law requires that legally binding financial commitments be made if the necessary appropriated funds are available, resulting in upfront scoring of costs, even if the actual expenditures occur years later. The uncertainty surrounding innovation and payouts can also create risk aversion, as most funding accounts are not “no-year” accounts, meaning committed funds can expire if competition goals are unmet within the designated timeframe.

To mitigate these constraints, agencies can use budgetary workarounds like no-year appropriations, allowing them to reallocate de-obligated funds from canceled competitions to new initiatives. Other options include employing credit-type scoring to discount costs based on the likelihood of non-payment and making non-legally binding commitments backed by third parties, such as international institutions, to avoid these challenges altogether.

The entire fund is expected to span a maximum of five () years. The initial 12 months will concentrate on identifying eight (8) to 16 projects through comprehensive due diligence and providing incubation support. In the subsequent four (4) years, the focus will shift to project delivery.

In contrast to the traditional push-funding approach of the CFDA program, our proposed pull-finance initiative introduces a unique market-shaping component aimed at driving key infrastructure and resilience solutions to fruition. In contrast to CFDA, pull finance addresses demand-side risks by providing demand-side guarantees of a future market for the technology or solution. It also mitigates R&D risk by combining incentives for research and development, ensuring that a viable market exists once the technology is developed. This approach helps accelerate market creation and innovation in high-risk, high-innovation sectors where demand or technological maturity is uncertain.

A National Guidance Platform for AI Acquisition

Streamlining the procurement process for more equitable, safe, and innovative government use of AI

The federal government’s approach to procuring AI systems serves two critical purposes: it not only shapes industry and academic standards but also determines how effectively AI can enhance public services. By leveraging its substantial purchasing power responsibly, the government can encourage high-quality, inclusive AI solutions that address diverse citizen needs while setting a strong precedent for innovation and accountability. Guidance issued in October 2024 by the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) gives recommendations on how agencies should use AI systems, focusing on public trust and data transparency. However, it is unclear how these guidelines align with general procurement regulations like the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR).

To reduce bureaucratic hurdles and encourage safe government innovation, the General Services Administration (GSA) should develop a digital platform that guides federal agencies through an “acquisition journey” for AI procurement. This recommendation is for streamlining guidance for procuring AI systems and should not be confused with the use of AI to simplify the procurement process. The platform should be intuitive and easy to navigate by clearly outlining the necessary information, requirements, and resources at each process stage, helping users understand what they need at any point in the procurement lifecycle. Such a platform would help agencies safely procure and implement AI technologies while staying informed on the latest guidelines and adhering to existing federal procurement rules. GSA should take inspiration from Brazil’s well-regarded Public Procurement Platform for Innovation (CPIN). CPIN helps public servants navigate the procurement process by offering best practices, risk assessments, and contract guidance, ensuring transparency and fairness at each stage of the procurement process.

Challenges and Opportunities

The federal government’s approach to AI systems is a crucial societal benchmark, shaping standards that ripple through industries, academia, and public discourse. Along with shaping the market, the government also faces a delicate balancing act when it comes to its own use of AI: it must harness AI’s potential to dramatically enhance efficiency and effectiveness in public service delivery while simultaneously adhering to the highest AI safety and equity standards. As such, the government’s handling of AI technologies carries immense responsibility and opportunity.

The U.S. federal government procures AI for numerous different tasks—from analyzing weather hazards and expediting benefits claims to processing veteran feedback. Positive impacts could potentially include faster and more accurate public services, cost savings, better resource allocation, improved decision-making based on data insights, and enhanced safety and security for citizens. However, risks can include privacy breaches, algorithmic bias leading to unfair treatment of certain groups, over-reliance on AI for critical decisions, lack of transparency in AI-driven processes, and cybersecurity vulnerabilities. These issues could erode public trust, inhibit the adoption of beneficial AI, and exacerbate existing social inequalities.

The federal government has recently published several guidelines on the acquisition and use of AI systems within the federal government, specifically how to identify and mitigate systems that may impact public trust in these systems. For example:

- OMB Memo M-24-10 (2024): Guides federal agencies on the use of artificial intelligence. It emphasizes responsible AI development and deployment, focusing on key principles such as safety, security, fairness, and transparency. The memo outlines requirements for AI governance, risk management, and public transparency in federal AI applications.

- OMB Memo M-24-18 (2024): Provides Guidance on AI acquisitions, such as transparency, continued guidance for incident reporting on rights and safety impacting AI, data management, and specific advice for AI-based biometrics.

- Agency Memos (2024): Per M-24-10, many U.S. agencies have published their internal strategies for AI use.

- AI Use Case Inventory (2024): Requires agencies to perform an annual inventory of AI systems with information on Procurement Instrument Identifiers and potential for rights or safety impacts.

- Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence (2023) This requires agencies to adopt trustworthy and responsible AI practices. It mandates using AI safety standards, including rigorous testing, auditing, and privacy protections across federal systems.

- Executive Order 13960 (2020) promotes the use of trustworthy artificial intelligence in government and outlines the responsibilities of agencies to ensure their AI use is ethical, transparent, and accountable. It includes the need for agencies to consider risks, fairness, and bias in AI systems.

This guidance, coupled with the already extensive set of general procurement regulations such as the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR ), can be overwhelming for public servants. In conversations with the author of this memo, stakeholders, including agency personnel and vendors, frequently noted that they needed clarification about when impact and risk assessments should occur in the FAR process.

How can government agencies adequately follow their mandate to provide safe and trustworthy AI for public services while reducing the bureaucratic burden that can result in an aversion to government innovation? A compelling example comes from Brazil. The Public Procurement Platform for Innovation (CPIN), managed by the Brazilian Ministry of Development, Industry, Commerce, and Services (MDIC), is an open resource designed to share knowledge and best practices on public procurement for innovation. In 2023, the platform was recognized by the Federal Court of Auditors (TCU—the agency that oversees federal procurement) as an essential new asset in facilitating public service. The CPIN helps public servants navigate the procurement process by diagnosing needs and selecting suitable contracting methods through questionnaires. Then, it orients agencies through a procurement journey, identifying what procurement process should be used, what kinds of dialogue the agency should have with potential vendors and other stakeholders, guidance for risk assessments, and contract language. The platform is meant to guide public servants through each stage of the procurement process, ensuring they know their obligations for transparency, fairness, and risk mitigation at any given time. CPIN is open to the public and is meant to be a resource, not new requirements that supplant existing mandates by Brazilian authorities.

Here in the U.S., the Office of Federal Procurement (OFFP) within the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in partnership with the General Services Administration (GSA) and the Council of Chief AI Officers (CAIO), should develop a similar centralized resource to help federal agencies procure AI technologies safely and effectively. This platform would ensure agencies have up-to-date guidelines on AI acquisition integrated with existing procurement frameworks.

This approach is beneficial because:

- Public-facing access reduces information gaps between government entities, vendors, and stakeholders, fostering transparency and leveling the playing field for mid- and small-sized vendors.

- Streamlined processes alleviate complexity, making it easier for agencies to procure AI technologies.

- Clear guidance for agencies throughout each step of the procurement process ensures that they complete essential tasks such as impact evaluations and risk assessments within the appropriate time frame.

GSA has created similar tools before. For example, the Generative AI Acquisition Resource Guide assists federal buyers in procuring and implementing generative AI technologies by describing key considerations, best practices, and potential challenges associated with acquiring generative AI solutions. However, this digital platform would go one step further and align best practices, recommendations, and other AI considerations within the processes outlined in the FAR and other procurement methods.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Establish a Working Group led by the OMB OFPP, with participation from GSA, OSTP, and the CAIO Council, tasked with systematically mapping all processes and policies influencing public sector AI procurement.

This includes direct AI-related guidance and tangential policies such as IT, data management, and cybersecurity regulations. The primary objective is identifying and addressing existing AI procurement guidance gaps, ensuring that the forthcoming platform can provide clear, actionable information to federal agencies. To achieve this, the working group should:

Conduct a thorough review of current mandates (see the FAQ for a non-exhaustive list of current mandates), executive orders, OMB guidance, and federal guidelines that pertain to AI procurement. This includes mapping out the requirements and obligations agencies must meet during acquisition. Evaluate if these mandates come with explicit deadlines or milestones that need to be integrated into the procurement timeline (e.g., AI risk assessments, ethics reviews, security checks)

Conduct a gap analysis to identify areas where existing AI procurement guidance needs to be clarified, completed, or updated. Prioritize gaps that can be addressed by clarifying existing rules or providing additional resources like best practices rather than creating new mandates to avoid unnecessary regulatory burdens. For example, guidance on handling personally identifiable information within commercially available information, guidance on data ownership between government and vendors, and the level of detail required for risk assessments.

Categorize federal guidance into two main buckets: general federal procurement guidance (e.g., Federal Acquisition Regulation [FAR]) and agency-specific guidelines (e.g., individual AI policies from agencies such as DoD’s AI Memos or NASA’s Other Transaction Authorities [OTAs]). Ensure that agency-specific rules are clearly distinguished on the platform, allowing agencies to understand when general AI acquisition rules apply and when specialized guidance takes precedence. Since the FAR may take years to update to reflect agency best practices, this could help give visibility to potential gaps.

Recommendation 2. The OMB OFPP-GSA-CAIO Council Working Group should convene a series of structured engagements with government and external stakeholders to co-create non-binding, practical guidance addressing gaps in AI procurement to be included in the platform.

These stakeholders should include government agency departments (e.g., project leads, procurement officers, IT departments) and external partners (vendors, academics, civil society organizations). The working group’s recommendations should focus on providing agencies with the tools, content, and resources they need to navigate AI procurement efficiently. Key focus areas would include risk management, ethical considerations, and compliance with cybersecurity policies throughout the procurement process. The guidance should also highlight areas where more frequent updates will be required, particularly in response to rapid developments in AI technologies and federal policies.

Topics that these stakeholder convenings could cover include:

Procurement Process

- Acquisition Pathways: What acquisition methods (e.g., FAR, Other Transaction Authorities [OTA], and joint acquisition programs) can be leveraged for procuring AI? Identify the most appropriate mechanisms for different AI use cases. For example, agencies looking to develop an advanced AI system with the help of external researchers may want to consider OTA if that is available to them.

- Integrating New Guidance: How can recent AI-related guidance from OMB memos (like M-24-10 and M-24-18) be incorporated into existing procurement frameworks, especially within the FAR?

- Stakeholder Responsibilities: Clearly define the roles and obligations of each party in the AI procurement process, from agency departments (such as project teams, procurement offices, and IT) to vendors and contractors. Determine who manages AI-related risks, evaluates AI systems, and ensures compliance with relevant policies.

- NIST AI Risk Management Framework (RMF): Explore how the NIST AI RMF can be integrated into the acquisition process and ensure agencies are equipped to assess AI risks effectively within procurement.

Transparency

- Public Disclosure: Define what information must be shared with the public at various stages of the AI acquisition process. Ensure there is a balance between transparency and protecting sensitive information.

- Data Sharing and Protection: Identify resources to help agencies understand their obligations regarding data sharing and protection under OMB Memo M-24-18 or forthcoming memos from the new administration to ensure compliance with any data security and privacy requirements.

- Risk Communication: Establish when and how to communicate to relevant stakeholders (e.g., the public and civil society) that a potential AI acquisition could impact public trust in AI technologies. Outline the types of transparency that should accompany AI systems that carry such risks.

Resources:

- External Best Practices: Gather and share civil society toolkits, industry best practices, and academic evaluations that can help agencies ensure the trustworthy use of AI. This would provide agencies with access to external expertise to complement federal guidelines and standards. The stakeholder convening should deliberate on whether these best practices will just be linked to the platform or if they need some kind of endorsement from government agencies.

Recommendation 3. The OPPF, in collaboration with GSA and the United States Digital Service (USDS) should then develop an intuitive, easy-to-navigate digital platform that guides federal agencies through an “acquisition journey” for AI procurement.

While the focus of this memo is on the broader procurement of AI systems, this digital platform could also benefit from the incorporation of AI, for example, by using a chatbot that is able to refer government users to the specific regulations governing their use cases. At each process stage, the platform should clearly outline the necessary information collected during the previous phases of this project to help users understand exactly what is needed at any given point in the procurement lifecycle.

The platform should serve as a central repository that unites all relevant AI procurement requirements, guidance from federal regulations (e.g., FAR, OMB memos), and insights from stakeholder convenings (e.g., vendors, academics, civil society). Each procurement stage should feature the most up-to-date guidance, ensuring a comprehensive and organized resource for federal employees.

The system should be designed for ease of navigation, potentially modeled after Brazil’s CPIN, which is organized like a city subway map. Users can begin with a simple questionnaire recommending a specific “subway line” or procurement process. Each “stop” along the line would represent a key stage in the procurement journey, offering relevant guidance, requirements, and best practices for that phase.

OPPF and GSA must regularly update the platform to reflect the latest federal AI and procurement policies and evolving best practices from government, civil society, and industry sources. Regular updates ensure that agencies use the most current information, especially as AI technologies and policies evolve rapidly.

The Federal Acquisition Institute within OFPP should create robust training programs to familiarize public servants with the new platform and how to use it effectively. These programs should explain how the platform supports AI acquisition and links to broader agency AI strategies.

- Roll out the platform gradually through agency-specific capacity-building sessions, demonstrating its utility for different departments. These sessions should show how the resource can help public servants meet their AI procurement needs and align with their agency’s strategic AI goals.

- Develop specialized training modules for different government stakeholders. For example, project teams might focus on aligning AI systems with mission objectives, procurement specialists on contract compliance, and IT departments on technical evaluations and cybersecurity.

- To ensure broad understanding and transparency, host public briefings for external stakeholders such as vendors, civil society organizations, and researchers. These sessions would clarify AI procurement requirements, fostering trust and collaboration between the public and private sectors.

Conclusion

The proposed centralized platform would represent a significant step forward in streamlining and standardizing the acquisition of AI technologies across federal agencies. By consolidating guidance, resources, and best practices into a user-friendly digital interface, this initiative would address gaps in the current AI acquisition landscape without increasing bureaucracy. This initiative supports individual agencies in their AI adoption efforts. It promotes a cohesive, government-wide approach to responsible AI implementation, ultimately benefiting both public servants and the citizens they serve.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

There are so many considerations based on a particular agency’s many needs. A non-exhaustive list of legislation, executive orders, standards and other guidance relating to innovation procurement and agency use of AI can be found here. One approach to top-level simplification and communication is to create something similar to Brazil’s city subway map, discussed above.

The original Brazilian CPIN is designed for general innovation procurement and is agnostic to specific technologies or services. However, this memo focuses on artificial intelligence (AI) in light of recent guidance from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the growing interest in AI from both the Biden Administration and the incoming Trump Administration. Establishing a platform specifically for AI system procurement could serve as a pilot for developing a broader innovation procurement platform.

The platform seeks to ensure responsible public sector AI by mitigating information asymmetries between government agencies and vendors, specifically by:

- Incorporating the latest OMB guidelines on AI system usage, focusing on human rights, safety, and data transparency. These guidelines are seamlessly integrated into each step of the procurement process.

- Throughout the “acquisition journey,” the platform should include clarifying checkpoints where agencies can demonstrate how their procurement plans align with established safety, equity, and ethical standards.

- Prompting agencies to consider how procured AI systems will address context-specific risks by integrating agency-specific guidance (e.g., the Department of Labor’s AI Principles) into the existing AI procurement frameworks.

Enhancing Local Capacity for Disaster Resilience

Across the United States, thousands of communities, particularly rural ones, don’t have the capacity to identify, apply for, and manage federal grants. And more than half of Americans don’t feel that the federal government adequately takes their interests into account. These factors make it difficult to build climate resilience in our most vulnerable populations. AmeriCorps can tackle this challenge by providing the human power needed to help communities overcome significant structural obstacles in accessing federal resources. Specifically, federal agencies that are part of the Thriving Communities Network can partner with the philanthropic sector to place AmeriCorps members in Community Disaster Resilience Zones (CDRZs) as part of a new Resilient Communities Corps. Through this initiative, AmeriCorps would provide technical assistance to vulnerable communities in accessing deeply needed resources.

There is precedent for this type of effort. AmeriCorps programming, like AmeriCorps VISTA, has a long history of aiding communities and organizations by directly helping secure grant monies and by empowering communities and organizations to self-support in the future. The AmeriCorps Energy Communities is a public-private partnership that targets service investment to support low-capacity and highly vulnerable communities in capitalizing on emerging energy opportunities. And the Environmental Justice Climate Corps, a partnership between the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and AmeriCorps, will place AmeriCorps VISTA members in historically marginalized communities to work on environmental justice projects.

A new initiative targeting service investment to build resilience in low-capacity communities, particularly rural communities, would help build capacity at the local level, train a new generation of service-oriented individuals in grant writing and resilience work, and ensure that federal funding gets to the communities that need it most.

Challenge and Opportunity

A significant barrier to getting federal funding to those who need it the most is the capacity of those communities to search and apply for grants. Many such communities lack both sufficient staff bandwidth to apply and search for grants and the internal expertise to put forward a successful application. Indeed, the Midwest and Interior West have seen under 20% of their communities receive competitive federal grants since the year 2000. Low-capacity rural communities account for only 3% of grants from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)’s flagship program for building community resilience. Even communities that receive grants often lack the capacity for strong grant management, which can mean losing monies that go unspent within the grant period.

This is problematic because low-capacity communities are particularly vulnerable to natural disasters from flooding to wildfires. Out of the nearly 8,000 most at-risk communities with limited capacity to advocate for resources, 46% are at risk for flooding, 36% are at risk for wildfires, and 19% are at risk for both.

Ensuring communities can access federal grants to help them become more climate resilient is crucial to achieving an equitable and efficient distribution of federal monies, and to building a stronger nation from the ground up. These objectives are especially salient given that there is still a lot of federal money available through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) that low-capacity communities can tap into for climate resilience work. As of April 2024, only $60 billion out of the $145 billion in the IRA for energy and climate programs had been spent. For the IIJA, only half of the nearly $650 billion in direct formula funding had been spent.