Reduce, Repurpose, Recharge: Establishing a Collaborative Doctrine of Groundwater Management in the Ogallala Aquifer

Summary

Climate change has resulted in extreme and irregular rain events across the United States. Consequently, farmers in the High Plains region have been increasingly dependent on the Ogallala Aquifer for water supplies. With an estimated value of $35 billion, this aquifer supports one-fifth of the nations’ wheat, corn, cotton, and cattle. The Ogallala once held enough water to fill Chicago’s Sears Tower over 2,000 times. Today, the aquifer has lost 30% of its supply — and it is being recharged at half the rate it is being depleted. The consequence of inaction is 70% aquifer depletion by 2060, which will reduce crop output by 30–40%.

This $14 billion loss to the High Plains agricultural production may be slowed and eventually reversed by (1) reducing Ogallala use, (2) repurposing existing supplies, and (3) recharging the aquifer. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), in collaboration with the Department of the Interior (DOI) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), should accordingly create the Reduce, Repurpose, Recharge Initiative (RRRI), a voluntary program designed to keep farmers engaged in groundwater conservation. This multi-state program will provide financial incentives to participating farmers in exchange for pledges to limit groundwater withdrawal and participate in training that will equip them with knowledge needed to fulfill those pledges. The RRRI will also make expert advisors available to consult with farmers on policies and funding opportunities related to groundwater conservation. Finally, this program will connect farmers across state lines, allowing them to learn from each other and work together on sustainable management of the Ogallala. The program should be funded through the various water-sustainability budgets of the DOI and USDA, as well as through FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities grant program.

Challenge and Opportunity

Climate-change-induced droughts have increased the nation’s dependence on groundwater as a source for agriculture, industry, and domestic use. Excessive groundwater pumping has led to land subsidence and deterioration of water quality, increasing water-use cost and jeopardizing crop yield. The problem is especially acute in the Ogallala Aquifer of the High Plains region. The aquifer underlies eight states of the nation’s breadbasket — including Nebraska, Kansas, and Texas — and spans 175,000 square miles. Dependence on the Ogallala has depleted its supply by 30% to date, as shown in Figure 1. 90% of water withdrawn from the Ogallala is used for agricultural irrigation.

Strategic plans for the USDA and DOI make it clear that drought preparedness and water conservation/sustainability are national priorities. Multiple federal efforts exist to advance these priorities. Publicly accessible platforms hosting and providing groundwater data exist at the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), and the cross-agency National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS) partnership. The 2018 Farm Bill strengthened technical- and financial-assistance programs to help individual farms implement water-conservation technology; the bill also created an incentive program for agriculture-to-wetland conversion. From 2011–2018, the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) ran the Ogallala Aquifer Initiative (OAI) to “support targeted, local efforts to conserve the availability of water, both its quantity and quality, in each of the States” covering the Ogallala. The OAI was successful in meeting its water-conservation goals. Recent surveys found that 93% of agricultural producers in the High Plains region believe that water conservation is important.

These past and ongoing initiatives demonstrate that federal will and stakeholder buy-in for aquifer conservation and restoration are there. The key need is for a program that provides farmers the incentives and technical assistance needed to minimize groundwater reliance, ending the tragedy of the commons in the Ogallala once and for all.

Plan of Action

USDA, DOI, and FEMA should launch a joint program designed to embed the three pillars of groundwater conservation — Reduce, Repurpose, and Recharge — into the practices of farmers in Ogallala states. The RRRI will provide a financial incentive to farmers in exchange for farmer commitments to:

- Achieve specified water-conservation targets.

- Participate in training opportunities and workshops teaching best practices for water conservation and aquifer recharge.

To succeed, the RRRI will require enthusiastic, voluntary participation from farmers across the High Plains region. Participation should be voluntary because studies have shown that voluntary programs are significantly more effective than mandates in achieving water-conservation goals. In a comparative case study about implementing

In a comparative case study about implementing a voluntary versus mandated water restriction, farmers under the voluntary restriction conserved more water relative to the mandatory regulation. A survey of these farmers attributed the group-education component of the voluntary program as the driving force for their restriction. Another survey similarly found that farmers’ altruistic views of water conservation led to longer-lasting participation in water-conservation activities. A comprehensive review of the outcomes of different water policies found that educational programs about water conservation were more effective in water use reduction and improving attitudes towards water conservation relative to mandatory water use restrictions.

To encourage voluntary participation, farmers who enroll in the RRRI would receive a financial incentive. The exact nature of the incentive would need to be determined by the implementing agencies, but could include preferential price setting, preferential market placement, or subsidies based on crop type. In exchange, farmers would agree to an initial water-use assessment performed by field experts (either employees or contractors of USDA or DOI). An appointed advisor (again, either employees or contractors of USDA or DOI) would then work with each farmer to establish long-term (5-year) water-conservation targets based on the assessment results. Each participating farmer would meet quarterly with their advisor to review their water-conservation plan, assess progress towards targets, make mutually agreeable target adjustments, and discuss challenges and solutions. Advisors would also be available in between quarterly meetings for interim questions and concerns.

Farmers who enroll in the RRRI would also commit to attending group trainings and workshops designed to help them identify and implement best water-conservation practices. These learning opportunities would be led by experts sourced from existing agricultural committees (e.g., NRCS Conservation Planners and Technical Service Providers, State Technical Committees, etc.) and water-conservation groups (e.g., Ogallala Water Coordinated Agriculture Project, Groundwater Protection Council, etc.). The group-education curriculum would cover the three tenets of groundwater conservation: reduce, repurpose, and recharge. Table 1 provides a brief description of each tenet, along with examples of aligned activities and potential sources of funding for those activities. The curriculum would teach farmers how each tenet contributes to groundwater conservation, existing and emerging technologies and practices that farmers can implement to achieve each tenet, and financial vehicles available to fund implementation. An added benefit of the group education will be the establishment of a community of farmers across the Ogallala states in which ideas and experiences can be shared.

| Tenet | Definition | Example activities | Potential funding source(s) |

| Reduce | Minimizing water needs for existing systems | More efficient irrigation | NRCS’s Agricultural Management Assistance and Conservation Innovation Grants |

| Repurpose | Move away from water-intensive practices | Switch to less water-intensive crops | NRCS’s Regional Conservation Partnership Program andConservation Stewardship Program |

| Recharge | Replenish groundwater source (aquifer) | Capture excess stormwater; convert agricultural land to wetlands | FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities Grant; NRCS’s Agricultural Conservation Easement Program |

The RRRI should be established as a multi-agency collaboration. Each involved agency (USDA, DOI, and FEMA) can provide unique expertise. USDA can leverage its research arm, NIFA, to produce up-to-date technology recommendations and scientific assessments. USDA’s NRCS can provide the underlying technical and financial support for realizing the RRRI tenets. DOI can rely on USGS’s existing groundwater database and the NIDIS’s affiliated expert community of data scientists to support the granular, up-to-date groundwater measurements needed to assess water-conservation progress. DOI’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) can ensure the RRRI tenets are enacted (in parallel with implementation on privately owned farmland) across public lands in the High Plains region. Finally, FEMA can collaborate with NIDIS and with USDA’s Risk Management Agency (RMA) to formally assess risks of drought and Ogallala depletion — assessments that can be used to make the case for the RRRI to farmers, funders, and policymakers.

Early actions needed to launch the RRRI include:

- Appoint a joint USDA/DOI task force to refine program goals and implementation strategy.

- Create teams of technical and financial experts to build the group-education curriculum.

- Identify people working at the interface of water conservation, land use, and drought preparedness who could serve as potential advisors.

- Recruit an initial cohort of farmers for a pilot version of the program. One pool to draw on for initial recruitment consists of the respondents to Lauer and Sanderson’s 2019 survey of producer attitudes in the Ogallala region.

- Socialize the proposal for RRRI with the House Agriculture Committee staff for authorization. The RRRI would fit well as part of the upcoming (in 2023) Farm Bill renewal.

Conclusion

Climate-change-induced droughts have increased farmer dependence on groundwater, resulting in a 30% depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer to date. Under current management practices, depletion of the Ogallala will reach 70% by 2060. We can solve the problem. The technology, technical expertise, programmatic and data infrastructure, and financial support for groundwater conservation exist. The key need is to directly connect farmers with — and motivate them to use — these resources. A joint USDA/DOI/FEMA program founded in the “Reduce, Repurpose, Recharge” tenets of water conservation can do just that for farmers across the High Plains region. By coupling financial incentives with tailored water-conservation targets, technical expertise, and group educational opportunities, the RRRI will meaningfully advance the long-term security of the critically important Ogallala—and the farmers whose livelihoods depend on it.

Based on the budget for the Ogallala Aquifer Initiative, the RRRI would require $25 million per year for 10-20 years to support the program’s staff and cover travel costs. This funding can be drawn from water-sustainability discretionary funds already allocated at USDA and DOI as well as FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities grant program.

Publications from the Ogallala Water Coordinated Agriculture Project cite numerous examples of existing technologies that can promote sustainable groundwater management, including irrigating with recycled water (i.e., direct non-potable reuse) and shifting to dryland irrigation.

The sandy soils of the High Plains are ideal for managed aquifer recharge as they allow for fast infiltration.

With no existing federal regulation on groundwater use, the country needs a pilot program to demonstrate the effectiveness of an interstate groundwater use policy to create precedent for future policymaking and begin to optimize water use policies at such a large scale. The Ogallala Aquifer is the largest and most productive aquifer in the world and conserving the agriculture it supports is required for a sustainable future.

While the federal government has regulations in place dictating water quality through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act, water-allocation policy is left up to the states. Between the eight states above the Ogallala Aquifer, there are four distinct doctrines that define groundwater law, some in direct conflict with one another. State authority over water resources makes it difficult for the federal government to implement mandatory groundwater conservation measures. Voluntary programs like RRRI are an effective mechanism to reach groundwater conservation goals without infringing on states’ water rights.

Increasing Capacity and Community Engagement for Environmental Data

Summary

Environmental justice (EJ) is a priority issue for the Biden Administration, yet the federal government lacks capacity to collect and maintain data needed to adequately identify and respond to environmental-justice (EJ) issues. EJ tools meant to resolve EJ issues — especially the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s EJSCREEN tool — are gaining national recognition. But knowledge gaps and a dearth of EJ-trained scientists are preventing EJSCREEN from reaching its full potential. To address these issues, the Administration should allocate a portion of the EPA’s Justice40 funding to create the “AYA Research Institute”, a think tank under EPA’s jurisdiction. Derived from the Adinkra symbol, AYA means “resourcefulness and defiance against oppression.” The AYA Research Institute will functionally address EJSCREEN’s limitations as well as increase federal capacity to identify and effectively resolve existing and future EJ issues.

Challenge and Opportunity

Approximately 200,000 people in the United States die every year of pollution-related causes. These deaths are concentrated in underresourced, vulnerable, and/or minority communities. The EPA created the Office of Environmental Justice (OEJ) in 1992 to address systematic disparities in environmental outcomes among different communities. The primary tool that OEJ relies on to consider and address EJ concerns is EJSCREEN. EJSCREEN integrates a variety of environmental and demographic data into a layered map that identifies communities disproportionately impacted by environmental harms. This tool is available for public use and is the primary screening mechanism for many initiatives at state and local levels. Unfortunately, EJSCREEN has three major limitations:

- Missing indicators. EJSCREEN omits crucial environmental indicators such as drinking-water quality and indoor air quality. OEJ states that these crucial indicators are not included due to a lack of resources available to collect underlying data at the appropriate quality, spatial range, and resolution.

- Small areas are less accurate. There is considerable uncertainty in EJSCREEN environmental and demographic estimates at the census block group (CBG) level. This is because (i) EJSCREEN’s assessments of environmental indicators can rely on data collected at scales less granular than CBG, and (ii) some of EJSCREEN’s demographic estimates are derived from surveys (as opposed to census data) and are therefore less consistent.

- Deficiencies in a single dataset can propagate across EJSCREEN analyses. Environmental indicators and health outcomes are inherently interconnected. This means that subpar data on certain indicators — such as emissions levels, ambient pollutant levels in air, individual exposure, and pollutant toxicity — can compromise the reliability of EJSCREEN results on multiple fronts.

These limitations must be addressed to unlock the full potential of EJSCREEN as a tool for informing research and policy. More robust, accurate, and comprehensive environmental and demographic data are needed to power EJSCREEN. Community-driven initiatives are a powerful but underutilized way to source such data. Yet limited time, funding, rapport, and knowledge tend to discourage scientists from engaging in community-based research collaborations. In addition, effectively operationalizing data-based EJ initiatives at a national scale requires the involvement of specialists trained at the intersection of EJ and science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). Unfortunately, relatively poor compensation discourages scientists from pursuing EJ work — and scientists who work on other topics but have interest in EJ can rarely commit the time needed to sustain long-term collaborations with EJ organizations. It is time to augment the federal government’s past and existing EJ work with redoubled investment in community-based data and training.

Plan of Action

EPA should dedicate $20 million of its Justice40 funding to establish the AYA Research Institute: an in-house think tank designed to functionally address EJSCREEN’s limitations as well as increase federal capacity to identify and effectively resolve existing and future EJ issues. The word AYA is the formal name for the Adinkra symbol meaning “resourcefulness and defiance against oppression” — concepts that define the fight for environmental justice.

The Research Institute will comprise three arms. The first arm will increase federal EJ data capacity through an expert advisory group tasked with providing and updating recommendations to inform federal collection and use of EJ data. The advisory group will focus specifically on (i) reviewing and recommending updates to environmental and demographic indicators included in EJSCREEN, and (ii) identifying opportunities for community-based initiatives that could help close key gaps in the data upon which EJSCREEN relies.

The second arm will help grow the pipeline of EJ-focused scientists through a three-year fellowship program supporting doctoral students in applied research projects that exclusively address EJ issues in U.S. municipalities and counties identified as frontline communities. The program will be three years long so that participants are able to conduct much-needed longitudinal studies that are rare in the EJ space. To be eligible, doctoral students will need to (i) demonstrate how their projects will help strengthen EJSCREEN and/or leverage EJSCREEN insights, and (ii) present a clear plan for interacting with and considering recommendations from local EJ grassroots organization(s). Selected students will be matched with grassroots EJ organizations distributed across five U.S. geographic regions (Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, Southwest, and West) for mentorship and implementation support. The fellowship will support participants in achieving their academic goals while also providing them with experience working with community-based data, building community-engagement and science-communication skills, and learning how to scale science policymaking from local to federal systems. As such, the fellowship will help grow the pipeline of STEM talent knowledgeable about and committed to working on EJ issues in the United States.

The third arm will embed EJ expertise into federal decision making by sponsoring a permanent suite of very dominant resident staff, supported by “visitors” (i.e., the doctoral fellows), to produce policy recommendations, studies, surveys, qualitative analyses, and quantitative analyses centered around EJ. This model will rely on the resident staff to maintain strong relationships with federal government and extragovernmental partners and to ensure continuity across projects, while the fellows provide ancillary support as appropriate based on their skills/interest and Institute needs. The fellowship will act as a screening tool for hiring future members of the resident staff.

Taken together, these arms of the AYA Research Institute will help advance Justice40’s goal of improving training and workforce development, as well as the Biden Administration’s goal of better preparing the United States to adapt and respond to the impacts of climate change. The AYA Research Institute can be launched with $10 million: $4 million to establish the fellowship program with an initial cohort of 10 doctoral students (receiving stipends commensurate with typical doctoral stipends at U.S. universities), and $6 million to cover administrative expenses and staff expert salaries. Additional funding will be needed to maintain the Institute if it proves successful after launch. Funding for the Institute could come from Justice40 funds allocated to EPA. Alternatively, EPA’s fiscal year (FY) 2022 budget for science and technology clearly states a goal of prioritizing EJ — funds from this budget could hence be allocated towards the Institute using existing authority. Finally, EPA’s FY 2022 budget for environmental programs and management dedicates approximately $6 million to EJSCREEN — a portion of these funds could be reallocated to the Institute as well.

Conclusion

The Biden-Harris Administration is making unprecedented investments in environmental justice. The AYA Research Institute is designed to be a force multiplier for those investments. Federally sponsored EJ efforts involve multiple programs and management tools that directly rely on the usability and accuracy of EJSCREEN. The AYA Research Institute will increase federal data capacity and help resolve the largest gaps in the data upon which EJSCREEN depends in order to increase the tool’s effectiveness. The Institute will also advance data-driven environmental-justice efforts more broadly by (i) growing the pipeline of EJ-focused researchers experienced in working with data, and (ii) embedding EJ expertise into federal decision making. In sum, the AYA Research Institute will strengthen the federal government’s capacity to strategically and meaningfully advance EJ nationwide.

Many grassroots EJ efforts are focused on working with scientists to better collect and use data to understand the scope of environmental injustices. The AYA Research Institute would allocate in-kind support to advance such efforts and would help ensure that data collected through community-based initiatives is used as appropriate to strengthen federal decision-making tools like EJSCREEN.

EJSCREEN and CEJST are meant to be used in tandem. As the White House explains, “EJSCREEN and CEJST complement each other — the former provides a tool to screen for potential disproportionate environmental burdens and harms at the community level, while the latter defines and maps disadvantaged communities for the purpose of informing how Federal agencies guide the benefits of certain programs, including through the Justice40 Initiative.” As such, improvements to EJSCREEN will inevitably strengthen deployment of CEJST.

Yes. Examples include the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute and the Asian-Pacific Center for Security Studies. Both entities have been successful and serve as primary research facilities.

To be eligible for the fellowship program, applicants must have completed one year of their doctoral program and be current students in a STEM department. Fellows must propose a research project that would help strengthen EJSCREEN and/or leverage EJSCREEN insights to address a particular EJ issue. Fellows must also clearly demonstrate how they would work with community-based organizations on their proposed projects. Priority would be given to candidates proposing the types of longitudinal studies that are rare but badly needed in the EJ space. To ensure that fellows are well equipped to perform deep community engagement, additional selection criteria for the AYA Research Institute fellowship program could draw from the criteria presented in the rubric for the Harvard Climate Advocacy Fellowship.

A key step will be grounding the Institute in the expertise of salaried, career staff. This will offset potential politicization of research outputs.

EJSCREEN 2.0 is largely using data from the 2020 U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, as well as many other sources (e.g., the Department of Transportation (DOT) National Transportation Atlas Database, the Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) modeling system, etc.) The EJSCREEN Technical Document explicates the existing data sources that EJSCREEN relies on.

The demographic indicators are: people of color, low income, unemployment rate, linguistic isolation, less than high school education, under age 5 and over age 64. The environmental indicators are: particulate matter 2.5, ozone, diesel particulate matter, air toxics cancer risk, air toxics respiratory hazard index, traffic proximity and volume, lead paint, Superfund proximity, risk management plan facility proximity, hazardous waste proximity, underground storage tanks and leaking UST, and wastewater discharge.

The Next Ten Years of Climate Policy, According to Our Experts

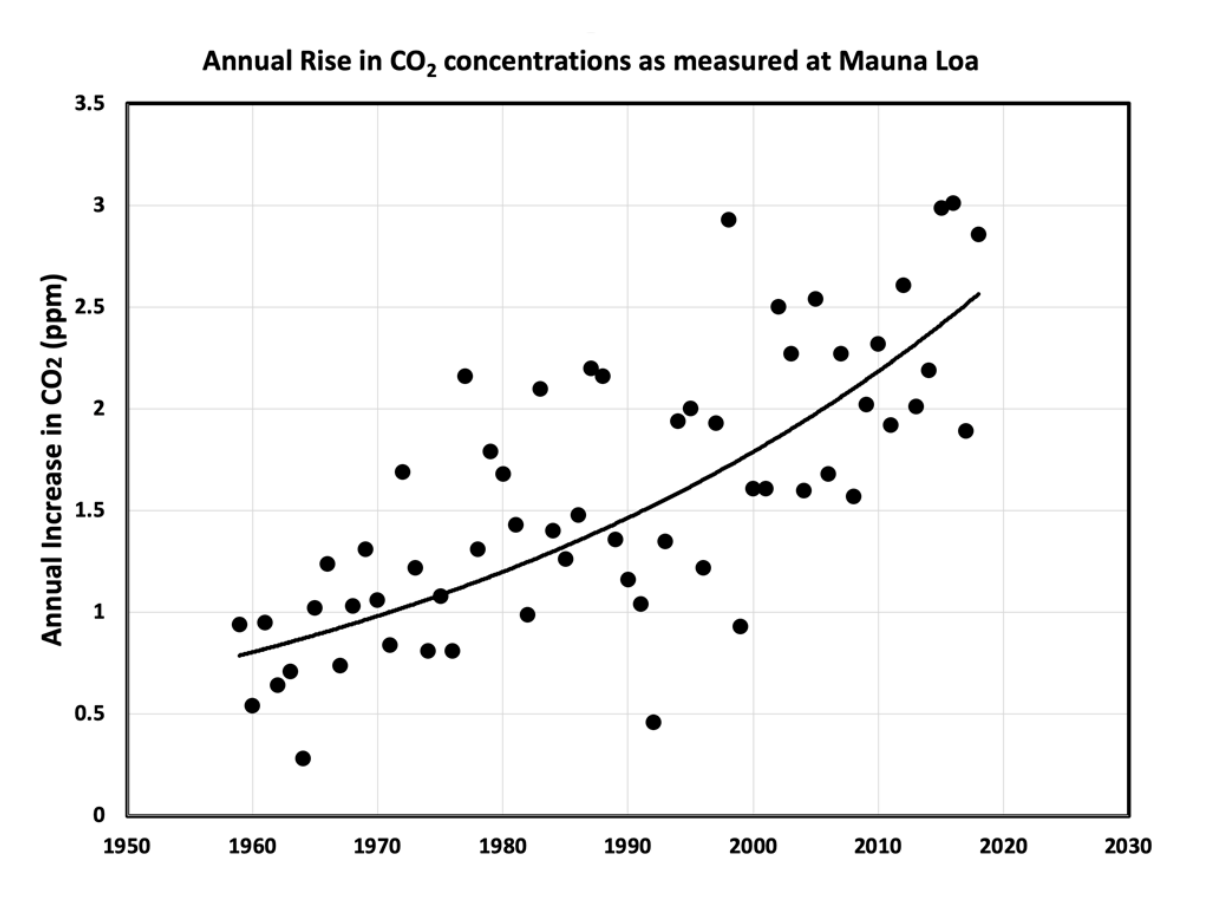

Two weeks ago, the IPCC released their most dire warning yet – that we have just three years to prevent the most catastrophic storms, natural disasters, and droughts human civilization might ever see. We are getting closer and closer to the temperature that scientists have warned us for decades would do irreversible damage to our societies and ecosystems.

But the role of scientists is not just one of town criers, warning us of what will come. Scientists are also activists taking fate into their own hands. Last week, scientists across the world staged sit-ins, held demonstrations, and handcuffed themselves to some of the worst climate offenders to send a bold message: the time for action is now.

As a science policy organization, we seek to bridge the gap between experts and policymakers. We have published dozens of proposals and policy memos outlining bold, perhaps even radical, climate policy ideas that would not only save the world, but will invigorate the U.S. and global economy with it.

Below, our experts, researchers, and staff share some of their thoughts on what the next ten years of climate policy will look like, how scientists can get involved in policymaking, and what they hope to see.

Matt Korda, Senior Research Associate and Project Manager, Nuclear Information Project

Climate change and nuclear weapons have a symbiotic relationship: each threat exacerbates the other. Climate change is setting the stage for conflict between nuclear-armed states, and a recent study suggests that even a regional nuclear war could cause mass global starvation for over a decade. Not to mention the fact that even during peacetime, decades of uranium mining, nuclear testing, and nuclear waste dumping have contaminated some of our planet’s ecosystems beyond repair, displacing entire communities—often communities of color—in the process.

Given the interconnectedness of both the climate crisis and nuclear weapons, we can’t afford for these two existential issues to be tackled in silos. Progressive climate change policies should include demilitarization and disarmament provisions, and progressive nuclear policies should address the climate and humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons. With that in mind, nuclear disarmament activists and climate change activists are natural allies in the fight to mitigate global catastrophic risks.

Ishan Sharma, Fellow and Policy Analyst, Technology & Innovation

The IPCC report is clear that a range of solutions is needed to reduce and remove carbon from the atmosphere, “an essential element of scenarios that limit warming to to 1.5℃ or likely below 2℃ by 2100”.

Across buildings, transport, energy transformation, infrastructure, and industry sectors, climate solutions technologies abound. The question is how to move the needle on their technology readiness levels. Or, in other words, what will spur their adoption at scale?

Let’s start with creating the right liftoff conditions — climate solutions startups have long described the trouble of gaining access to funding given the large upfront costs of hardtech (when compared to software). As a result, many exciting ideas fail to cross the “Valley of Death” and achieve scaled adoption.

But what if we employed new ways of de-risking investments into climate solutions startups that incentivized more capital flows? One example: committing to buy a certain technology in advance, or advanced market commitments (AMCs). AMCs were recently used in Operation Warp Speed to de-risk and galvanize Pfizer, Moderna, and other pharma companies’ investments to produce COVID-19 vaccines. Last week, an alliance of big tech companies under the organization Frontier poured $925 million towards carbon removal, including large portions towards AMCs because by “committing to buy a product early, you can help bring it to market faster”.

Fortunately, the White House Council on Environmental Quality is challenging each agency to leverage its purchasing power in each sustainability plan, turning the federal government into a massive source of clean demand.

There’s also the related problem of scaling this type of innovation across the United States. How do you encourage legacy energy communities to support these transitions into the green economy? One way is to create the right set of economic conditions that incentivizes — and provides for — well paying jobs in new growth sectors.

Currently, there are only a handful of cities with the “industries and a solid base of human capital [to] keep attracting good employers and offering high wages … ecosystems form in these hot cities, complete with innovation companies, funding sources, highly educated workers and a strong service economy.” Spreading innovation to underleveraged regions is difficult for a number of reasons, including training a willing workforce and securing a viable investment ecosystem for startup liftoff.

But if done right, it could be another answer to rising inflation, as it would bring new demand to “stone cold” markets and stabilize prices from the bottom up and middle out.

Fortunately, nascent regional investment efforts like the Economic Development Administration’s Build Back Better Regional Challenge and the Department of Energy’s Energy Program for Innovation Clusters seeks a holistic approach to green development, bringing breakthrough research happening in the labs, training workforces in the locality, empowering startup liftoff, and facilitating spillover economic benefits from climate solutions’ commercialization. Federal assets — from national labs to federally funded R&D at universities to manufacturing innovation institutes — should be brought to bear in supporting this innovation-cluster based approach.

But part of this clean growth climate solution will require coupling our investments in cutting-edge R&D with our investments in manufacturing, in order to produce and commercialize these technologies at scale in the United States. Decades of underinvestment in manufacturing has sacrificed the art of “learning-by-building” — the substantial, value-add interactions that happen when manufacturers are seated at the table with designers.

This is the reason why China-based companies own 80% of the solar panel market share, despite photovoltaic cells’ invention at Bell Labs in 1954. After heavily subsidizing the manufacturing of solar panels, China capitalized on the benefits of learning-by-building, perhaps the most important factor explaining the nearly 100% drop in PV cells’ module costs over the last 30 years.

If America is going to lead on solving climate change with breakthrough R&D, we need to ensure we can produce the technologies at scale — lest we risk losing our competitive and economic advantage. But we also need to think seriously about the additional regulatory structures promoting oil and gas above clean growth expansion.

One example is geothermal energy, which could have already supplied unlimited clean electricity for a cost of around 3¢/kWh, but progress in the field was stunted by entrepreneurial risks of dealing with permitting requirements at up to 2 years of approval timelines. This is despite the Energy Policy Act of 2005 granting oil and gas companies carveouts to perform the same type of drilling geothermal would need. What if we did the same, today, for geothermal?

Another example is the well-known fossil fuels subsidies, which have been rather hard to kill. These subsidies are responsible for as much as 68-78% of the average rate of return for fossil fuel endeavors. But what might a targeted decoupling look like for fossil fuels subsidies? Several researchers have investigated this very question, identifying which are the most high-leverage subsidies to kill. At first place is the intangible drilling costs subsidy (IDC), which “increases [the] U.S.-wide average IRR by 11 and 8 percentage points for oil and gas fields, respectively.” I’m not the first to advocate for the removal of this subsidy, it’s been decades in the making, but those before me underscore the crucial need for attention focused on high-leverage subsidies — chipping away bit-by-bit at the unnecessary market advantage oil and gas has received for nearly a century.

Erica Goldman, Director of Science Policy

My back porch looks out into an urban forest in Silver Spring, MD, actually just a few miles from where Rachel Carson lived and wrote Silent Spring. Over the past few weeks, like all over the DC region, the bare trees behind my house bloomed brilliant pinks and whites and purples, and then went quickly green. Now, the forest gets noisier each day – birds in the morning, frogs and cicadas at night, occasional owls and foxes in intermittent conversation.

Most years, I don’t pay attention to how fast all of this happens. But this year I noticed. I’ve been thinking a lot about thresholds for change, sudden inflection points that make the incremental, exponential. With climate change, these tipping points often signal catastrophe – melting glaciers, intensifying storms, and rising seas. But what if tipping points are the key to positive change as well, and targeted interventions can bring larger than expected returns?

Last week, the California Air Resources Board proposed to raise the sale of new cars that are electric, hydrogen-powered or plug-in hybrids to 100% by 2035. In late 2021, the Federal Sustainability Plan issued the ambitious target for the whole-of-government fleet to be fully electric by the same year. Meanwhile, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law allocates $21 billion over the next five years for the Office of Clean Energy Demonstration, which could dramatically accelerate the pace of deployment of key low-carbon technologies like clean hydrogen, advanced nuclear energy, and carbon capture and storage (CCS) from industrial facilities and power plants. With these kinds of targeted interventions, strategic subsidies, and technologies ready for lift off, might these positive climate tipping points be within reach?

Scientists think maybe. An article in Nature last week showed that the climate pledges made by nations at the COP26 meeting could in fact ensure that global warming does not exceed 2 ºC before 2100 — but only if backed up by short-term policies. Meanwhile, other researchers are studying how to intentionally trigger positive tipping points through social, technological and ecological innovations, policy interventions, public investment, private investment, broadcasting public information, and behavioral nudges.

Taken together, my sense is that positive tipping points give us agency and help “unlock paralysis by complexity,” transcending incrementalism and offering “plausible grounds for hope.” We know what nature is capable of, if we can get smart about how to jumpstart recovery and then get out of the way.

Regulating Probiotic Use and Improving Veterinary Care to Bolster Honeybee Health

This memo is part of the Day One Project Early Career Science Policy Accelerator, a joint initiative between the Federation of American Scientists & the National Science Policy Network.

Summary

One-third of the food Americans eat comes from honeybee-pollinated crops. Honeybees used for commercial pollination operations are routinely treated with antibiotics as a preventative measure against bacterial infections. Pre- and probiotics are marketed to beekeepers to help restore honeybee gut health and improve overall immune function. However, there is little to no federal oversight of these supplements. Apiculture supplements currently on the market are expensive but often ineffective. This leaves unaware farmers wasting money on “snake oil” products while honeybee colonies remain weakened — threatening not just the U.S. agricultural economy, but also the livelihoods of beekeepers and farmers. At the same time, widespread use of antibiotics in apiculture puts honeybees at high risk of spreading antibiotic resistance.

To address these issues, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s Office of Human and Animal Food Operations and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s National Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIFA) should work together to (1) create an FDA review and approval process for pre- and probiotic apiculture products, (2) design educational programs designed to educate veterinarians on best practices for beekeeping health and husbandry, and (3) offer grants to help farmers and apiculturists access high-quality veterinary care for honeybee colonies.

Challenge and Opportunity

Honeybee pollination services are pivotal to the U.S. agricultural economy. It is estimated that about one-third of the food Americans eat comes from crops pollinated by honeybees. Throughout the past decade, beekeepers have suffered colony losses that make commercial apiculture challenging. These colony losses are caused by complex and interconnected issues including the rise of honeybee diseases such as bacterial infections like American Foulbrood or viral infections linked to pests like the Varroa mite, a general increase in hive pests, habitat fragmentation and nutrition loss, and increased use of pesticides and/or pesticide exposure.

The substantial threats posed by bacterial and viral diseases to honeybee colonies have driven commercial beekeeping operations to routinely treat their hives with antibiotics (mainly oxytetracycline). Unfortunately, antibiotic treatment can also (i) compromise honeybee health by wiping out beneficial bacteria in the honeybee microbiome, and (ii) promote antibiotic resistance. Routine use of antibiotics in apiculture hence compounds the challenges mentioned above and further compromises the livelihoods of U.S. farmers and the security of U.S. food systems.

In 2017, the FDA responded to antibiotic overuse in apiculture by amending the Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD) section of the Animal Drug Availability Act of 1996 (ADAA). The 2017 amendment required beekeepers to obtain veterinary approval to treat their colonies with antibiotics against certain diseases. While attractive on paper, the implementation of this policy has encountered challenges in practice. Finding a vet who understands the highly complex dynamics of apiculture has been a substantial challenge for commercial beekeepers, especially in rural areas. Improvements to the implementation of the VFD are needed to contain the spread of antibiotic resistance in apiculture.

Relatedly, researchers, beekeepers, and companies alike have all been on the hunt for a solution to restore honeybee health after antibiotic treatment. Pre- and probiotic therapy has recently been proposed as a promising and cost-effective strategy to enhance human and animal health, particularly to restore beneficial gut bacteria following antibiotic treatment. Several companies have developed pre- and probiotic supplements targeted at commercial apiculturists. Two popular supplements are HiveAliveTM and SuperDFM®-HoneyBeeTM. HiveAliveTM is marketed as a prebiotic and is composed of seaweed, thymol, and lemongrass extracts. Although there is some evidence that HiveAliveTM decreases infectious fungal-spore counts and reduces winter honeybee mortality, the value of this supplement as a honeybee prebiotic (i.e., to boost growth or activity of beneficial gut bacteria prior to antibiotic treatment) has not been tested. SuperDMF®-HoneyBeeTM is marketed as a probiotic that can restore the honeybee gut microbiome. But SuperDMF®-HoneyBeeTM is exclusively composed of microbes — isolated from mammals or the environment — that have never been found in honeybees and therefore are probably incapable of colonizing the bee gut. To date, neither HiveAliveTM nor SuperDFM®-HoneyBeeTM has been scientifically shown to protect or restore the honeybee gut microbiome from adverse effects of antibiotic treatment.

A big part of the reason why pre- and probiotic supplements for honeybees (as well as for other agricultural uses) have not been externally validated is that such products are not subject to FDA or USDA regulation. This lack of federal oversight means that beekeepers interested in using such products have only the manufacturer’s word that the products will work as promised. Federal intervention is needed to protect commercial farmers and beekeepers from predatory companies selling expensive “snake oil” products.

Plan of Action

To ensure the long-term sustainability of U.S. apiculture and agriculture, the FDA and USDA should work together on the following three-part strategy to improve the administration of antibiotics in apiculture and to strengthen the regulation of pre- and probiotic supplements marketed to commercial beekeepers.

Part 1. Educate veterinarians in beekeeping to limit misuse and overuse of antibiotics.

For instance, the USDA’s Office of Pest Management Policy (OPMP) and National Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIFA) could collaborate with the U.S. Honeybee Veterinary Consortium on an annual training program, hosted at the USDA’s Bee Research Laboratory, to educate vets working in agricultural areas on the basics of honeybee disease, prevention, treatment, and post-treatment options. The training could also discuss the latest evidence on the efficacy of pre- and probiotic supplements, ensuring that vets can help beekeepers navigate this emerging marketplace of products. Additionally, for veterinarians who are unable to travel to in-person training, these resources could be made available in an online portal.

Part 2. Strengthen regulation of pre- and probiotics marketed to beekeepers.

Currently, the market for pre- and probiotics targeted at beekeepers is a veritable “wild west”: one that allows the marketing and sale of essentially any product as long as the ingredients included are deemed safe per the Official Publication of the Association of American Feed Control Officials and are either (i) approved for addition to animal feed (per part 573 in Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR 573)), and/or (ii) generally recognized as safe (GRAS) for the intended use (including those listed in 21 CFR 582 and 584). Notably, the efficacy of marketed pre- and probiotics does not have to be demonstrated. Therefore, in alignment with an FDA guidance document recommending stronger oversight of pre- and probiotics targeted at beekeepers, FDA’s Office of New Animal Drug Evaluation (ONADE) should extend its normal animal drug approval process to include pre- and probiotic supplements marketed to beekeepers.

Part 3: Provide apiculturists with better access to high-quality veterinary care.

USDA could create a new Honeybee Veterinary Services Grant Program (HVSGP) that offers rural farmers and beekeepers funding to obtain vet care for their colonies. This program would be modeled after the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA)’s Veterinary Services Grant Program, which provides funding to help rural farmers access high-quality vet care for farm animals. The USDA could also consider launching a parallel Honeybee Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program (HVMLRP; again modeled on an AVMA program), which would help place vets trained in beekeeping husbandry “in high-need rural areas by providing strategic loan repayment help in exchange for service”. Vets participating in this program would agree to provide the following services:

- Quarterly visits to commercial apiaries in need of vet support.

- Prescriptions of antibiotics as appropriate after colony inspection.

- Collection and reporting of data on health and treatment outcomes of serviced hives

Conclusion

Widespread use of antibiotics in commercial beekeeping is a problem for bees, beekeepers, and the larger ecosystem due to the spread of antibiotic resistance and the negative effects of antibiotic treatment on honeybee health. The federal government can mitigate these adverse effects by improving the knowledge and reach of vets trained in best practices for antibiotic treatment in apiculture, as well as by improving regulation of pre- and probiotic supplements purported to restore honeybee gut microbiomes following antibiotic treatment. These actions will collectively secure the health of honeybees — and the livelihoods of farmers who depend on them — for the long term.

Pre- and probiotics should be regulated in both humans and animals. Pre- and probiotic supplements marketed for human use, like those marketed for apicultural use, are poorly regulated and rife with misleading, untested, or simply false claims. While this memo focuses on the apicultural sector, there is certainly a broader need for increased federal intervention with respect to the safety and efficacy of pre- and probiotics.

The FDA’s 2017 amendments to the VFD mean that if a beekeeper needs to administer antibiotics to their honeybees, they must obtain a prescription or feed directive from a licensed veterinarian. Therefore, vets have a new professional incentive to better understand the dynamics of beekeeping husbandry.

In an ideal world, commercial beekeeping would rely on antibiotics only as a last resort. But the reality is that commercial beehives today — due to factors such as a history of intensive antibiotic use in apiculture and the practice of transporting colonies en masse from place to place — are so susceptible to deadly bacteria that imposing major restrictions on antibiotic use in apiculture would seriously compromise U.S. agricultural productivity and the livelihoods of American farmers. Farmers, researchers, and policymakers should continue to collaborate on strategies for phasing out apicultural antibiotic use in the long term. But in the near term, actions should still be taken to promote best practices for apicultural antibiotic treatment and to better regulate supplements that could help minimize adverse impacts of antibiotic treatment on honeybee health.

Yes, these regulations should apply to existing products as well as products developed in the future.

The AVMA’s Veterinary Services Grant Program (VSGP) receives funding annually through Congressional appropriations. This funding was $3.5 million for Fiscal Year 2022 (FY22). The HBVSGP could be launched with a similar amount. HBVSGP funding could come from new Congressional appropriations, and/or from existing USDA programs. For instance, the 2008e Farm Bill designated pollinators and their habitat a priority for the USDA and authorized money for projects that promoted pollinator habitat and health under the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). Money could also be earmarked from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), Agriculture and Food Research Initiative – Education and Workforce Development grant program to encourage the research and development of better pre- and probiotic supplements and continuing education programs in honeybee veterinary care.

Eliminating Childhood Lead Poisoning Worldwide

An estimated 815 million children (one in three) around the globe have dangerous levels of lead in their bloodstream, levels high enough to cause irreversible brain damage and impose severe health, economic, and societal consequences. 96% of these children live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where collectively only about $6–10 million from non-governmental organizations is available each year to address the problem. To help eliminate childhood lead poisoning worldwide, the U.S. Federal Government should (1) add blood lead level (BLL) testing to the USAID-led Demographic and Health Survey Program, (2) create a Grand Challenge for Development to end childhood lead poisoning, and (3) push forward a global treaty on lead control.

Challenge and Opportunity

Lead is a potent toxin that causes irreversible harm to children’s brains and vital organs. Elevated body lead levels result in reduced intelligence, lower educational attainment, behavioral disorders, violent crime, reduced lifetime earnings, anemia, kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease. Impacts of lead on cognitive development are estimated to cause nearly $1 trillion of income loss in LMICs annually. Adverse health effects related to lead poisoning account for 1% of the global disease burden, causing 1 million deaths annually and substantial disability.

This enormous burden of lead poisoning in LMICs is preventable. It results from a combination of sources of exposure, some of the most important being:

- Lead that is intentionally added to paint, spices, cookware, and cosmetics.

- Lead that contaminates the environment from unsafe lead-acid battery and e-waste recycling practices.

- Lead that contaminates drinking water from pipes.

These sources of lead exposure have been effectively regulated in the United States and other high-income countries, which have seen average blood lead levels in their populations decline dramatically over the last 40 years. To achieve the same success, LMICs will need to prioritize policies such as:

- Regulation limiting the lead content of paint available on the market.

- Regulation of lead-acid battery and e-waste recycling.

- Inclusion of lead parameters in national drinking-water-quality standards.

- Regulation of the use of lead compounds in other locally important sources, such as spices, ceramics, cookware, toys, and cosmetics.

LMICs generally face three major barriers to implementing such policies:

- Lack of data on blood lead levels and on the scale and severity of lead poisoning. Most LMICs have no studies measuring blood lead levels. Policymakers are therefore unaware of the extent of the problem and hence unlikely to act in response.

- Lack of data on which sources of lead exposure are the biggest local contributors. Causes of lead poisoning vary spatially, but the vast majority of LMICs have not conducted source-apportionment studies. This makes it difficult to prioritize the most impactful policies.

- Limited access to equipment needed to detect lead in paint, spices, water, other sources, or the environment. Without needed detection capabilities, regulators cannot investigate the lead content of potential sources, nor can they monitor and enforce regulation of known sources.

These barriers are relatively simple to overcome, and when they are overcome do indeed result in action. As an example, at least 20 LMICs introduced legally binding lead paint regulation after the Global Alliance to Eliminate Lead Paint and its partners helped those countries confirm that lead paint was an important source of lead poisoning. Moreover, addressing childhood lead poisoning is in line with the priorities of the Biden Administration and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The Administration has already proposed an ambitious $15 billion plan to address childhood lead poisoning in the United States by eliminating lead pipes and service lines. By contributing to global elimination efforts (for only a fraction of what it will cost to solve the problem domestically), the Administration can multiply its impact on reducing childhood lead poisoning. Doing so would also advance USAID’s mission of “advanc[ing] a free, peaceful, and prosperous world”, since a reduction in childhood lead poisoning worldwide would improve health, strengthen economies, and prevent crime and conflict.

Plan of Action

Lead poisoning, from a variety of sources, affects one in three children worldwide. This is an unacceptable situation that demands action. The United States should adopt a three-part roadmap to help LMICs implement and enforce policies needed to achieve global elimination of childhood lead poisoning.

Recommendation 1. Add blood lead level (BLL) testing to the USAID-led Demographic and Health Survey.

USAID, through its Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), is in an ideal position to address the first barrier that LMICs face to implementing anti-lead poisoning policies: lack of data and awareness. The DHS collects, analyzes, and disseminates accurate and representative data on health in over 90 countries. Including BLL testing in the DHS would:

- Make accurate and representative data on the prevalence and severity of lead poisoning in LMICs available for the first time.

- Draw national and international attention to the immense burdens that childhood lead poisoning continues to impose.

- Determine which LMIC populations are most impacted by childhood lead poisoning.

- Motivate interventions to target the most impacted populations and most important sources of exposure.

- Support quantitative evaluation of interventions that aim to reduce lead exposure.

As such, USAID should add BLL testing of children into the DHS Biomarker Questionnaire for all host countries. This could be done in DHS revision for Phase 9, beginning in 2023. Including BLL testing in the DHS is also the first step to addressing the second barrier that LMICs face: lack of data on sources of lead exposure. BLL data collected through the DHS would reveal which countries and populations have the greatest lead burdens. These data can be leveraged by researchers, governments, and NGOs to investigate key sources of lead exposure.

BLL testing of children is feasible to carry out in the context of the DHS. It was successfully piloted in 1998 and 2002 via the DHS presence in India and Uzbekistan, but not rolled out further. Testing can be carried out using finger-stick capillary sampling and portable analyzers, so venipuncture and laboratory analysis are not required. Further, such testing can be carried out by health technicians who are already trained in capillary blood testing of children for anemia as part of the DHS. The testing can be conducted while questionnaires are administered, and results and any follow-up actions can be shared with the parent/guardian immediately. Alternatively, laboratory lead tests can be added onto sample analysis if blood draws are already being taken. Costs are low in both cases, estimated at around $10 per test.

Recommendation 2. Create a Grand Challenge for Development to end childhood lead poisoning.

Childhood lead poisoning in LMICs is dramatically neglected relative to the scale of the problem. Though childhood lead poisoning costs LMICs nearly $1 trillion annually and accounts for 1% of the global disease burden, only about $6–10 million per year is dedicated to addressing the problem. A USAID-led Grand Challenge for Development to end childhood lead poisoning would mobilize governments, companies, and foundations around generating and implementing solutions. In particular, the Challenge should encourage solutions to the second and third barriers presented above: lack of data on sources of lead exposure and limited detection capacity.

Recommendation 3. Push forward a global treaty on lead control.

A global push is needed to put childhood lead poisoning on the radar of decision-makers across the world and spur implementation and enforcement of policies to address the issue. The Biden Administration should lead an international conference to develop a global treaty on lead control. Such a treaty would set safe standards for lead in a variety of products (building on the Global Alliance to Eliminate Lead Paint’s toolkit for establishing lead-paint laws) and recommend regulatory measures to control sources of lead exposure. The success of the UN’s Partnership for Clean Fuels and Vehicles in bringing about global elimination of leaded gasoline illustrates that international political will to act can indeed be generated around lead pollution.

Conclusion

By implementing this three-part roadmap the Biden administration and USAID can make a historic and catalytic contribution towards global elimination of lead poisoning. There is true urgency; the problem becomes harder to solve each year as more lead enters the environment where it will remain a source of exposure for decades to come. Acting now will improve the health, wellbeing and potential of hundreds of millions of children.

Though relatively little investigation has been done on childhood lead poisoning in LMICs, the studies that do exist have consistently shown very high levels of lead poisoning. A recent systematic reviewidentified studies of background levels of childhood lead exposure in 34 LMICs. According to the review, “[o]f the 1.3 billion children (aged 0–14 years) living in the 34 LMICs with acceptable data on background blood lead levels in children, approximately 632 million…were estimated to have a level exceeding the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] reference value of 5 μg/dL, and 413 million…were estimated to exceed the previous reference value of 10 μg/dL.” Data collected by the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation and analyzed in a joint UNICEF/Pure Earth report published in 2020 similarly concluded that dangerously elevated BLLs affect over 800 million children worldwide.

Major sources of lead poisoning in LMICs include paint, spices, cookware, pottery, pipes, cosmetics, toys, unsafe lead-acid battery recycling, unsafe e-waste recycling, and poorly controlled mining and smelting operations. High-income countries like the United States have relatively low levels of lead poisoning due to strong regulations around these sources of lead poisoning. Most high-income countries have, for instance, banned lead in gasoline and paint, set enforceable standards around the lead content of water, and imposed strong regulations around food adulteration. As a result, median BLLs in high-income countries have declined dramatically (in the United States, from 15ug/dL in the 1970s to <1µg/dL today). LMICs generally lack many of these effective controls around lead exposure and therefore have very high levels of childhood lead poisoning.

The most important thing that can be done to tackle the scourge of childhood lead poisoning is to impose source controls that prevent lead from entering the environment or consumer products. Though the relative contributions of different sources to childhood lead poisoning differ by country, effective policies and interventions tend to include:

- Regulations limiting the lead content of paint available on the market.

- Regulation of lead-acid battery and e-waste recycling practices.

- Inclusion of lead parameters in national drinking-water-quality standards.

- Regulation of the use of lead compounds in other locally important sources, such as spices, ceramics, cookware, toys, and cosmetics.

To enforce these policies, LMICs need testing capacity sufficient to monitor lead levels in potential exposure sources and in the environment. LMICs also need BLL monitoring to track the impact of policies and interventions. Fully eliminating childhood lead poisoning will ultimately involve abatement: i.e., removing lead already in the environment, such as by taking off lead paint already on walls and by replacing lead pipes. However, these interventions are extremely costly, with much lower impact per dollar than preventing lead from entering the environment in the first place.

An extreme lack of awareness, lack of data, and lack of advocacy around childhood lead poisoning in LMICs has created a vicious cycle of inattention. A large part of the problem is that lead poisoning is invisible. Unlike a disease like malaria, which causes characteristic cyclical fevers that indicate their cause, the effects of lead poisoning are more difficult to trace back.

Deploy a National Network of Air-Pollution and CO2 Sensors in 300 American Cities by 2030

Summary

The Biden-Harris Administration should deploy a national network of low-cost, co-located, real-time greenhouse gas (GHG) and air-pollution emission sensors in 300 American cities by 2030 to help communities address environmental inequities, combat global warming, and improve public health. Urban areas contribute more than 70% of total GHG emissions. Aerosols and other byproducts of fossil-fuel combustion — the major drivers of poor air quality — are emitted in huge quantities alongside those GHGs. A “300 by ‘30” initiative establishing a national network of local, ground-level sensors will provide precise and customized information to drive critical climate and air-quality decisions and benefit neighborhoods, schools, and businesses in communities across the nation. Ground-level dense sensor networks located in community neighborhoods also provide a resource that educators can leverage to engage students on co-created “real-time and actionable science”, helping the next generation see how science and technology can contribute to solving our country’s most challenging issues.

Challenge and Opportunity

U.S. cities contribute 70% of our nation’s GHG emissions and have more concentrated air pollutants that harm neighborhoods and communities unequally. Climate change profoundly impacts human health and wellbeing through drought, wildfire, and extreme-weather events, among numerous other impacts. Microscopic air pollutants, which penetrate the body’s respiratory and circulatory systems, play a significant role in heart disease, stroke, lung cancer, and asthma. These diseases collectively cost Americans $800 billion annually in medical bills and result in more than 100,000 Americans dying prematurely each year. Also, health impacts are experienced more acutely for certain communities. Some racial groups and poorer households, especially those located near highways and industry, face higher exposure to harmful air pollutants than others, deepening health inequities across American society.

GHG emissions and ground-level air pollution are both negative products of fossil-fuel combustion and are inextricably linked. But our nation lacks a comprehensive approach to measure, monitor, and mitigate these drivers of climate change and air pollution. Furthermore, key indicators of air quality — such as ground-level pollutant measurements — are not typically considered alongside GHG measurements in governmental attempts to regulate emissions. A coordinated and data-driven approach across government is needed to drive policies that are ambitious enough to simultaneously and equitably tackle both the climate crisis and worsening air-quality inequities in the United States.

Technologies that are coming down in cost enable ground-level, real-time, and neighborhood-scale observations of GHG and air-pollutant levels. These data support cost-effective mapping of carbon dioxide (CO2) and air-quality related emissions (such as PM2.5, ozone, CO, and nitrogen oxides) to aid in forecasting local air quality, conducting GHG inventories, detecting pollution hotspots, and assessing the effectiveness of policies designed to reduce air pollution and GHG emissions. The result can be more successful, targeted strategies to reduce climate impacts, improve human health, and ensure environmental equity.

Pilot projects are proving the value of hyper-local GHG and air-quality sensor networks. Multiple universities, philanthropies, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have launched pilot projectsdeploying local, real-time GHG and air-pollutant sensors in cities including Los Angeles, New York City, Houston, TX, Providence, RI, and cities in the San Francisco Bay Area. In the San Francisco Bay Area, for instance, a dense network of 70 sensors enabled researchers to closely investigate how movement patterns changed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Observations from local air-quality sensors could be used to evaluate policies aimed at increasing electric-vehicle deployment, to demonstrate how CO and NOx emissions from vehicles change day to day, and to prove that emissions from heavy-duty trucks disproportionately impact lower-income neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color. The federal government can and should incorporate lessons learned from these pilot projects in designing a national network of air-quality sensors in cities across the country.

Components of a national air-quality sensor network are in place. On-the-ground sensor measurements provide essential ground-level, high-spatial-density measurements that can be combined with data from satellites and other observing systems to create more accurate climate and air-quality maps and models for regions, states, and the country. Through sophisticated computational models, for instance, weather data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are already being combined with existing satellite data and data from ground-level dense sensor networks to help locate sources of GHG emissions and air-pollution in cities throughout the day and across seasons. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is working on improving these measurements and models by encouraging development of standards for low-cost sensor data. Finally, data from pilot projects referenced above is being used on an ad hoc basis to inform policy. Data showing that CO2 emissions from the vehicle fleet are decreasing faster than expected in cities with granular emissions monitoring are that policies designed to reduce GHG emissions are working as or better than intended. Federal leadership is needed to bring the impacts of such insights to scale on larger and even more impactful levels.

A national network of hyper-local GHG and air-quality sensors will contribute to K–12 science curricula. The University of California, Berkeley partnered with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on the GLOBE educational program. The program provides ideas and materials for K–12 activities related to climate education and data literacy that leverage data from dense local air-quality sensor networks. Data from a national air-quality sensor network would expand opportunities for this type of place-based learning, motivating students with projects that incorporate observations occurring on the roof of their schools or nearby in their neighborhoods to investigate the atmosphere, climate, and use of data in scientific analyses.Scaling a national network of local GHG and air-quality sensors to include hundreds of cities will yield major economies of scale. A national air-quality sensor network that includes 300 American cities — essentially, all U.S. cities with populations greater than 100,000 — will drive down sensor costs and drive up sensor quality by growing the relevant market. Scaling up the network will also lower operational costs of merging large datasets, interpreting those data, and communicating insights to the public. This city-federal collaboration would provide validated data needed to prove which national and local policies to improve air quality and reduce emissions work, and to weed out those that don’t.

Plan of Action

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), in partnership with the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the National Science Foundation (NSF) should lead a $100 million “300 by ’30: The American City Urban Air Challenge” to deploy low-cost, real-time, ground-based sensors by the year 2030 in all 300 U.S. cities with populations greater than 100,000 residents.

The initiative could be organized and managed by region through an expanded NOAA Regional Collaboration Network, under the auspices of NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research. NOAA is responsible for weather and air-quality forecasting and already manages a large suite of global CO2 and global air-quality-related observations along with local weather observations. In a complementary manner, the “300 by ‘30” sensor network would measure CO2, CO (carbon monoxide), NO (nitric oxide), NO2 (nitrogen dioxide), O3 (ozone), and PM2.5 (particulate matter down to 2.5 microns in size) at the neighborhood scale. “300 by ‘30” network operators would coordinate data integration and management within and across localities and report findings to the public through a uniform portal maintained by the federal government. Overall, NOAA would coordinate sensor deployment, network integration and data management and manage the transition from research to operations. NOAA would also work with NIST and EPA to provide uniform formats for collecting and sharing data.

Though NOAA is the natural agency to lead the “300 by ‘30” initiative, other federal agencies can and should play key supporting roles. NSF can support new approaches to instrument design and major innovations in data and computational science methods for analysis of observations that would transition rapidly to practical deployment. NIST can provide technical expertise and leadership in much-needed standards-setting for GHG measurements. NASA can advance the STEM-education portion of this initiative (see below), showing educators and students how to observe GHGs and air quality in their neighborhoods and how to link ground-level observations to observations made from space. NASA can also work with NOAA to merge high-density ground-level and wide-area space-based datasets. BEA can develop local models to provide the nonpartisan, nonpolitical economic information cities will need to inform urban air-policy decisions triggered by insights from the sensor network. Similarly, the EPA can help guide cities in using climate and air-quality information from the sensor network. The CDC can use network data to better characterize public-health threats related to climate change and air pollution, as well as to coordinate responses with state and local health officials.

The “300 by ‘30” challenge should be deployed in a phased approach that (i) leverages lessons learned from pilot projects referenced above, and (ii) optimizes cost savings and efficiencies from increasing the number of networked cities. Leveraging its Regional Collaboration Network, NOAA would launch the Challenge in 2023 with an initial cohort of nine cities (one in each of NOAA’s nine regions). The Challenge would expand to 25 cities by 2024, 100 cities by 2027, and all 300 cities by 2030. The Challenge would also be open to participation by states and territories whose largest cities have populations less than 100,000.

The challenge should also build on NASA’s GLOBE program to develop and share K–12 curricula, activities, and learning materials that use data from the sensor network to advance climate education and data literacy and to inspire students to pursue higher education and careers in STEM. NOAA and NSF could provide additional support in promoting observation-based science education in classrooms and museums, illustrating how basic scientific observations of the atmosphere vary by neighborhood and collectively contribute to weather, air-quality, and climate models.

Recent improvements in sensor technologies are only now enabling the use of dense mesh networks of sensors to precisely pinpoint levels and sources of GHGs and air pollutants in real time and at the neighborhood scale. Pilot projects in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, Houston, Providence, and New York City have proven the value of localized networks of air-quality sensors, and have demonstrated how data from these sensors can inform emissions-reductions policies. While individual localities, states, and the EPA are continuing to support pilot projects, there has never been a national effort to deploy networked GHG and air-quality sensors in all of the nation’s largest cities, nor has there been a concerted effort to link data collected from such sensors at scale.

Although urban areas are responsible for over 70% of national GHG emissions and over 70% of air pollution in urban environments, even cities with existing policy approaches to GHGs and air quality lack the information to rapidly evaluate whether their emissions-reduction policies are effective. Further, COVID-19 has impacted local revenue, strained municipal budgets, and has understandably detracted attention from environmental issues in many localities. Federal involvement is needed to (i) give cities the equipment, data, and support they need to make meaningful progress on emissions of GHGs and air pollutants, (ii) coordinate efforts and facilitate exchange of information and lessons learned across cities, and (iii) provide common standards for data collection and sharing.

A pilot project including a 20-device sensor network was led by U.S. scientists and developed for the City of Glasgow, Scotland as a demonstration for the COP26 climate conference. The City of Glasgow is an active partner in efforts to expand sensor networks, and is one model for how scientists and municipalities can work together to develop needed information presented in a useful format.

Sensors appropriate for this initiative can be manufactured in the United States. A design for a localized network air-quality sensors the size of a shoe box has been described in freely available literature by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley. Domestic manufacture, installation, and maintenance of sensors needed for a national monitoring network will create stable, well-paying jobs in cities nationwide.

Leading scientific societies Optica (formerly OSA) and the American Geophysical Union (AGU) are spearheading the effort to provide “actionable science” to local and regional policymakers as part of their Global Environmental Measurement & Monitoring (GEMM) Initiative. Optica and AGU are also exploring opportunities with the United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) to expand these efforts. GHG- and air-quality-measurement pilot projects referenced above are based on the BEACO2N Network of sensors developed by University of California, Berkeley Professor Ronald Cohen.

Procurement as an Instrument of Policy: Novel Approaches to Climate Challenges

Our roundtable of climate and procurement experts discussed the underutilized role of the federal government as a strategic buyer to overcome market failures in scaling innovative solutions to climate change. Speakers included:

- Andrew Mayock, Federal Chief Sustainability Officer at the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ).

- Thomas Kalil, Chief Innovation Officer at Schmidt Futures

- Dr. Lara Pierpoint, Director of Climate, Actuate

- Jetta Wong, Day One Project Policy Entrepreneur in Residence and SeniorFellow, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF)

Initial Perspectives

The session began with remarks from Thomas Kalil (Schmidt Futures), who provided an introduction into procurement levers, or “demand-pull” mechanisms.

- Economists distinguish between push and pull approaches to innovation. The former is an important, traditional feature of government efforts to promote R&D, such as tax credits or grants to a university researcher or firm that covers costs of a project. The latter involves innovative ways to leverage the role of government as a buyer.

- For example, the Falcon 9 rocket, a partnership between the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and SpaceX, gave the United States an important capability to send rockets to the International Space Station without being dependent on Russia. The NASA-SpaceX contract used payments that were contingent on meeting key milestones, or “milestone- based payments.” NASA got access to this capability at a fraction of the cost as a “business as usual” approach, such as cost-plus contracts.

- Another example was Operation Warp Speed, which applied Nobel laureate Michael Kremer’s solution of “advanced market commitments” — a guarantee to purchase a given volume of a product that doesn’t exist yet — to the market failure of vaccine development.

- Government should utilize financial contingencies based on success, not failure, by identifying where market failures exist and defining metrics of success and the reward (e.g., prize, purchase order, milestone payment, etc.) This would be a powerful new arrow in our quiver to solve the climate crisis. Ideally, demand-pull mechanisms would create a marketplace for outcomes: someone establishes a goal, industry teams compete to meet this goal, investors bet on these teams, and we see who is successful at reaching finish line.

The session then shifted to a discussion from Andrew Mayock (CEQ) about the Bidenadministration’s key priorities in combatting climate change, along with nascent conversations on procurement.

- The federal government is back in action in the procurement area. From Day One of the administration with Executive Order 14008, the President called on agencies to use our buying power to tackle the climate crisis. The power of the executive order and its impact on movement throughout the federal government is noteworthy. It has helped increase transparency and standards, especially with respect to transitioning the full federal fleet of vehicles to zero emissions.

- On October 7th, the administration released a series of agency climate adaptation and resilience plans to deliver on the President’s Day One goals. The White House Council on Environmental Quality played a key role in defining standards and implementing quality reports.

- More recently, the administration’s Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council has been meeting to improve the rules of the game when it comes to procurement. They released the Federal Acquisition Regulation: Minimizing the Risk of Climate Change in Federal Acquisitions for public comment and would welcome your feedback on this.