New Declassification Reforms Are Classified

Legislative measures to improve the process of declassifying classified national security information were introduced by Sen. Ron Wyden in the pending intelligence authorization act for FY2022. But they were included in the classified annex so their substance and import are not publicly known.

“I remain deeply concerned about the failures of the Federal Government’s obsolete declassification system,” Sen. Wyden wrote in a statement that was included in the new Senate Intelligence Committee report on the intelligence bill. “I am therefore pleased that the classified annex to the bill includes several amendments I offered to advance efforts to accelerate declassification and promote declassification reform.”

But the nature of those amendments has not been disclosed. “As absurd as it is to be opaque about the topic of declassification I’m afraid I can’t tell you more right now,” a Committee staffer said. “Sorry.”

“Putting aside the irony of declassification amendments found only in a classified annex, I can confirm that we’re tracking it,” said an intelligence community official.

It requires some effort to think of declassification reforms that could themselves be properly classified. The idea seems counterintuitive. But there are agency declassification guides that are classified because they detail the precise boundaries of classified information. And any directive to declassify an entirely classified topical area would have to begin by identifying the classified subject matter that is to be declassified.

“True perfection seems imperfect,” says the Tao Te Ching (trans. Stephen Mitchell), and “true straightness seems crooked.” Still, some things are truly crooked.

Nuclear Secrecy: In Defense of Reform

One of the stranger features of nuclear weapons secrecy is the government’s ability to reach out and classify nuclear weapons-related information that has been privately generated without government involvement. This happened most recently in 2001.

The roots of this constitutionally questionable policy are investigated in Restricted Data, a book by science historian Alex Wellerstein that sheds new light on the origins and development of nuclear secrecy.

One might suppose that nuclear secrecy is merely incidental to the larger history of nuclear weapons, but Wellerstein demonstrates that the subject is rich and dynamic and consequential enough to merit a history of its own.

He traces nuclear secrecy back to the Manhattan Project (or shortly before) when the most basic questions were first posed: what is a nuclear secret? what is the role of “information” in creating nuclear weapons? what can secrecy accomplish and what are its hazards? when and how are secrets to be disclosed?

Answers to such questions naturally varied. The basic idea of the atomic bomb did not actually involve any secrets, according to physicist Hans Bethe. But when it came to the hydrogen bomb, he said, “this time we have a real secret to protect.”

Wellerstein is not just an accomplished historian who has done his archival homework, he is also a lively storyteller. And he leavens his narrative with surprising observations and insights. We learn, for example, that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn read a copy of the official Smyth Report on the atomic bomb while on his way to the Gulag. Elsewhere Wellerstein writes that declassification can be a way of reinforcing classification: “the release of some information [is] used to uphold the importance of not releasing other information. . . . disclosure could be a form of control as well.”

Challenges to nuclear secrecy quickly came from many directions: Soviet spies, recalcitrant scientists, careless bureaucrats, and eventually “anti-secrecy” activists.

Wellerstein devotes a particularly engaging chapter to the “anti-secrecy” efforts of Howard Morland, the late Chuck Hansen, and Bill Arkin who all, for their own diverse reasons, defied or circumvented secrecy controls.

He gives less focused attention to more conventional attempts to reform and reduce nuclear secrecy, which he seems to consider less significant than the antagonistic efforts to discover classified matters.

Maybe because I was present on the periphery of the Openness Initiative led by Secretary of Energy Hazel O’Leary in 1993-97, I found Wellerstein’s treatment of it to be somewhat cursory and understated. From my perspective, the O’Leary Openness Initiative represented the single biggest discontinuity in the history of nuclear secrecy since the 1945 Smyth Report that first described the production of the atomic bomb.

Within a fairly short period of time, O’Leary declassified and disclosed (as Wellerstein notes) a complete list of nuclear explosive tests and their yields; inventories of highly enriched uranium and weapons-grade plutonium; most of the previously classified research on inertial confinement fusion; and a wealth of other historical and contemporary nuclear weapons-related information that had been sought by researchers and advocates. The final report of a year-long Fundamental Classification Policy Review launched by O’Leary and intended to reboot classification policy somehow did not make it into Wellerstein’s notes or bibliography. A copy is here.

Outside critics of secrecy who join the government will often adapt themselves to the status quo, Wellerstein writes. They find that secrecy is “sticky” and hard to dislodge. Yet O’Leary dislodged it repeatedly.

The date of her 1993 Openness press conference — it was December 7 — remains fresh in memory because a Washington Times columnist called it “the most devastating single attack on the underpinnings of the U.S. national security structure since Japan’s lightning strike” on Pearl Harbor. That can’t have been pleasant for her. But O’Leary came back and did it again with more declassified disclosures a few months later. And then again.

So one lesson for secrecy reform that emerges from the O’Leary Openness Initiative is that it matters who is in charge. Given a choice between an opportunity to wordsmith a classification policy regulation or to select an agency head who is committed to open government, it is clear what the right move would be. Good policy statements can be ignored or subverted. Good leaders will often get the job of reform done.

A second lesson here is that “nuclear secrecy” is not an undifferentiated mass of information and that not all nuclear secrets are equally important or equally in demand.

O’Leary’s use of the management jargon of “stakeholders” reflected the reality that different groups had different interests in reducing nuclear secrecy and that different secrets were sought by each. Environmentalists wanted environmental information. Laser fusion scientists wanted fusion technology. Arms controllers wanted stockpile data. Historians wanted other things. And so on. Interestingly, there was also plenty of stuff that no one wanted. There is a good deal of classified technical data that has little or no policy relevance or historical significance — or that everyone agrees is properly withheld.

It can be difficult to think clearly about nuclear secrecy and to set aside what one wishes were true in order to acknowledge what actually appears to be the case. As startling and unprecedented as O’Leary’s disclosures were, the lasting impact of the Openness Initiative was limited, as Wellerstein assesses. Her disclosures were not reversed (they couldn’t be), but her successors resembled her predecessors more than they resembled her. What’s worse is that mere “facts” like those that she released seem to have less traction on the political process than ever before.

Wellerstein does an outstanding job of explaining how we got where we are today, and his analysis will help inform where we might realistically hope to go in the future. Restricted Data is bound to be the definitive work on the history of nuclear secrecy.

* * *

Last month marked 30 years since the classified Pentagon nuclear rocket program codenamed Timberwind was disclosed without authorization. See “Secret Nuclear-Powered Rocket Being Developed for ‘Star Wars'” by William J. Broad, New York Times, April 3, 1991.

In those days before the world wide web and the proliferation of online news and opinion, the story’s appearance on the front page of the New York Times (“above the fold”) commanded wide attention and soon led to formal declassification of the program followed by its termination.

* * *

There is no shortage of secrets remaining at the Department of Energy, according to one recent account. See “If You Want To Hide A Classified Program, Try The Department Of Energy” by Brett Tingley, The Drive: The Warzone, May 13.

A Self-Correcting Classification System?

Those persons who have authorized access to classified information that they believe is improperly classified are “encouraged and expected” to challenge the classification of that information (Executive Order 13526, section 1.8).

Sometimes they do. And every once in a while, their challenges lead to declassification of the information.

A new report from the Government Accountability Office notes one recent example of a “classification challenge about military personnel overseas.” In that case, “as a result of the formal classification challenge, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy ultimately decided to declassify the information.” See National Security: DOD and State Have Processes for Formal and Informal Challenges to the Classification of Information, GAO-21-294, April 16, 2021.

The procedures for identifying and challenging over-classification have the potential to multiply existing oversight of the classification system many times over. Instead of just a bare handful of overseers at the Information Security Oversight Office and a few other places, all of the more than four million cleared personnel in government and industry could be mobilized to help evaluate the classified information that they handle, to recognize unnecessary classification, and to challenge it.

Ideally, such internal classification challenges would make the classification system at least partially self-correcting, as it was in the recent case cited by GAO.

But although the GAO reported that procedures for classification challenges are in place at the Department of Defense, that is only superficially accurate. The actual practice of formal classification challenges is highly localized in just a few corners of DoD and is totally absent from most others.

Of the 633 formal classification challenges that were reported by DOD in FY2016, there were a wildly disproportionate 496 challenges from US Pacific Command alone and another 126 from the Missile Defense Agency. (The reported numbers do not include challenges that are handled informally without leaving any record.)

Meanwhile, of the 677 DOD classification challenges that were reported in FY 2017, there were no more than 3 in all of the large DoD intelligence agencies.

The reason for this vast disparity among DoD agencies is not clear but it is probably not just a statistical fluke. Rather, it appears that a few DOD components are encouraging (or at least tolerating) classification challenges while most others are oblivious to or unaware of the procedure — if they are not actively discouraging it.

The good news here is that there is vast room for improvement.

If those DOD (and other) agencies and organizations that are not reporting classification challenges were directed to actively promote and encourage such challenges, it could go a long way toward improving classification policy generally.

Currently, however, things are moving in the other direction. DoD officials told GAO that they now “had few, if any, formal classification challenges.” They said “they relied more on informal classification challenges” with no identifiable impact.

But even if only 5-10% of the contested classifications are actually overturned (the number was 17.5% in 2016, according to ISOO), classification challenges could be an effective mechanism for enhancing the quality of classification decisions.

* * *

The new GAO report was prompted by a request from Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) asking GAO to assess the procedures for challenging classification, including the options available to Congress.

GAO found that while Members of Congress can initiate challenges to classification at DOD and State, Members cannot appeal denials of their challenges (or failure to act) to the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel. Senator Murphy’s own attempt to do so last year was rebuffed. (Senator’s Challenge to War Powers Secrecy Blocked, Secrecy News, September 11, 2020).

To rectify this situation and to enhance congressional oversight of classification policy, Sen. Murphy and Sen. Ron Wyden introduced The Transparency in Classification Act (S. 932).

“Overclassification for political purposes undermines Congress’s ability to hold the executive branch accountable and unnecessarily keeps the American public in the dark,” said Sen. Murphy. “Regardless of the administration, protecting the integrity of the classification system is a matter of national security.”

* * *

The activities of the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel — which considers appeals of classification challenges and of Mandatory Declassification Review requests that have been denied — have been severely curtailed by the COVID-19 pandemic as well by longstanding logistical and administrative problems.

Between September 2020 and March 2021, the Panel decided on only four appeals. More than a thousand appeals are pending.

2020 Declassification Deadline Remains in Force

Classified records that turn 25 years old this year will be automatically declassified on December 31 — despite requests from agencies to extend the deadline due to the pandemic — unless the records are reviewed and specifically found to be subject to an authorized exemption.

Mark A. Bradley, the director of the Information Security Oversight Office, notified executive branch agencies last week that there is no basis in law or policy for deferring the automatic declassification deadline.

“Several agencies have expressed concerns that, due to diminished operational capacity and capability, they would likely be unable to complete declassification reviews of their 25-year old classified permanent records before the onset of automatic declassification on December 31, 2020. These agencies have requested some form of relief, such as a declassification delay or waiver,” Mr. Bradley said in his November 20 letter.

But the executive order that governs declassification and the implementing regulations “do not permit the declassification delays or waivers requested in this instance,” he wrote.

Mr. Bradley advised agencies “to adopt a risk-based approach and prioritize the review of their most sensitive records” in order to identify the most important information that might be exempt from automatic declassification.

But the fact remains that any “Originating agency information in 25-year old permanent records that are not reviewed prior to December 31, 2020 will be automatically declassified,” he wrote.

Mr. Bradley’s letter emphasized that automatic declassification applies only to information in records held by the originating agency, but not to information that originated with other agencies. Such other agency “equity” information is supposed to be referred to those agencies for their subsequent review.

Yet although the letter does not mention it, under the terms of the executive order (sec. 3.3d(3)) the identification of information generated by another agency is also supposed to be completed in advance of the December 31 deadline. It is unclear whether an agency’s failure to identify information for referral to other agencies prior to the deadline would nullify the referral and eliminate the opportunity for subsequent review.

While records that have been automatically declassified can in principle be reclassified, that is easier said than done. Though automatic declassification can be performed in bulk, reclassification is only permitted on a document by document basis, requiring in each case a written justification by the agency head.

Last week, the State Department announced the publication of the latest volume of the Foreign Relations of the United States series documenting the Iran hostage crisis of 1979-80.

Few if any of the newly published records were subject to automatic declassification. Instead, “The declassification review of this volume . . . began in 2010 and was completed in 2018,” the editors wrote.

Trump Jr: “Declassify Everything!!!”

On November 8 Donald J. Trump Jr., the President’s oldest son, tweeted: “DECLASSIFY EVERYTHING!!!” adding “We can’t let the bad actors get away with it.”

This was not an actual policy proposal and it was not seriously intended for classification officials or even for Trump’s own father, who as President is the one ultimately responsible for classification policy.

Rather, it was directed at Trump Jr.’s 6.4 million Twitter followers, telling them that classification is a corrupt process that protects “bad actors” and that must therefore be discredited and dismantled. It’s a juvenile notion but not, given the size and malleability of Trump’s audience, an inconsequential one.

To the extent that national security classification is in fact required, for example, to protect advanced military technologies, the conduct of diplomacy or the collection of intelligence, it is important to establish and maintain the legitimacy of classification policy. For the same reason, abuse of classification authority can itself be a threat to national security.

The current executive order on classification policy (sect. 1.7a(1)) directs that “in no case shall information be classified . . . in order to conceal violations of law.”

But this is merely a limitation on the classifier’s mental state — which is unverifiable — and not on classification itself. It is entirely permissible for classified information to conceal violations of law, according to a judicial interpretation of the executive order, as long as the information is not classified with that specific purpose (“in order to”) in mind. This is a standard that has never been enforced and that is probably unenforceable.

So one step that the incoming Biden Administration could take to enhance the integrity and accountability of classification policy would be to direct that classification may not conceal violations of US law at all, whether or not that is the intent of classifying. (It is probably necessary to specify “US” law since classified intelligence collection may often involve the violation of foreign laws.)

Donald Trump is the first president since George H.W. Bush who made no formal changes to the executive order on classification policy.

Instead, Trump often defied or disregarded existing classification and declassification policies, withholding previously public information (e.g. the number of nuclear warheads dismantled each year) and disclosing normally classified information (e.g. an actual application for counterintelligence surveillance) when it advanced his political interests to do so.

But it seems that arbitrary secrecy combined with selective declassification is not the way to stop “bad actors.”

Senator’s Challenge to War Powers Secrecy Blocked

Last January the Trump Administration formally notified Congress under the War Powers Act of a US drone strike that killed Iranian Maj. Gen. Qasem Soleimani.

But unlike all known prior War Powers Act notifications, the report on the Soleimani killing was classified in its entirety. (Previous reports sometimes included a classified annex together with the unclassified notification.)

Senator Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) said that was unacceptable. “There’s a veil being pulled over the foreign policy of this country,” he told the Washington Post. See “Six months later, Democrats keep working to unearth a big national security secret” by Greg Sargent, The Washington Post Plum Line, July 21, 2020.

Senator Murphy asked the White House to reconsider the classification. “It is critical that decisions regarding the use of force consistent with the War Powers Act be provided in unclassified form to the American people,” he wrote. He received no response.

So he turned to the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel (ISCAP), a group of executive branch agency representatives that is authorized by executive order to decide appeals of challenges to classification.

The initiative failed. Last month the ISCAP said that it would not consider such an appeal from Senator Murphy or from any other member of Congress.

The ISCAP refusal leaves the War Powers Act report on Soleimani fully classified and it keeps the public in the dark about the asserted legal and factual basis for killing him. But it highlights an important gap in classification policy that could be corrected in a new Administration and a new Congress.

* * *

When information is classified improperly or unnecessarily, the opportunities for correcting such actions are quite limited.

A provision for government employees to formally challenge the classification of certain information was introduced in President Clinton’s 1995 executive order 12958 (section 1.9) and has remained in effect until the present (executive order 13526, section 1.8). The provision states:

“Authorized holders of information who, in good faith, believe that its classification status is improper are encouraged and expected to challenge the classification status of the information. . . .”

Importantly, this provision was not intended as a courtesy or a privilege. In fact, it was not intended for the sake of the challengers at all. Rather, the purpose of such classification challenges was to promote the integrity of the classification system and to help make the system self-correcting, as far as possible. That’s why potential challengers are “encouraged and expected” to present challenges even if they don’t personally care about the issue at all.

There were 954 such challenges in fiscal year 2016, according to the Information Security Oversight Office, and 167 of those resulted in the classification being overturned in whole or in part. In FY 2017, there were 721 challenges, 58 of which led to changes in classification.

No member of Congress had ever invoked this provision before. But Senator Murphy had some reason to believe that such a classification challenge could be effective in the case of the Soleimani war powers report.

The sticking point was the definition of “authorized holders of [classified] information,” who are the only ones that can present a classification challenge under the executive order.

One would suppose that a member of Congress who is in possession of a classified report that was officially provided to him or her by the executive branch would certainly qualify as an “authorized holder.” In fact, the executive branch has a binding legal obligation to provide certain classified defense and intelligence information to Congress.

But it turns out that the executive order (in section 6.1c) narrowly defines an “authorized holder of classified information” as one who has been vetted by an agency and found eligible for access. (Oddly, this limiting definition was only added in 2009.) Since Members of Congress are cleared for classified information by virtue of their office and do not undergo agency vetting, they are not “authorized persons” for purposes of the executive order.

This does not make any sense from a policy point of view. Just as executive branch employees and contractors are “encouraged and expected” to point out potential errors in classification, so should Members of Congress be, and for the same reasons.

But the classification challenge procedure is constrained by the language of the executive order, said Mark Bradley, director of the Information Security Oversight Office and executive secretary of the ISCAP.

“We have to do what the Order says, not what we want,” said Mr. Bradley, who early in his career served as an aide to Senator Daniel P. Moynihan.

* * *

Mr. Bradley suggested that Senator Murphy could direct his challenge to the Public Interest Declassification Board, which unlike the ISCAP is specifically authorized to review congressional challenges to the classification of certain records.

But the PIDB is a much weaker body than the ISCAP. While the ISCAP can “decide” on classification challenges (subject to appeal), the PIDB can only review and “recommend.” And while the ISCAP has actually overturned existing classifications on numerous occasions, no PIDB recommendation has ever had the same effect.

The PIDB did previously handle one congressional request for declassification review, said John Powers of the ISOO and PIDB staff, in or around 2014. For the most part, the subject document in that case turned out to be properly classified, substantively and procedurally, in the PIDB’s view. But the Board forwarded a limited redaction proposal that would have allowed partial release to the Obama White House for consideration. The White House did not act on it.

Senator Murphy turned to the PIDB to request declassification review of classified intelligence concerning foreign interference in the upcoming US elections, the Washington Post reported yesterday.

* * *

The statement by ISOO director Mark Bradley cited above — “We have to do what the Order says, not what we want” — is worth further consideration.

What he was saying is that those who are responsible for enforcing checks and balances have to follow a code of conduct and have to adhere to a set of principles, whether or not they personally agree with the outcome in a particular case.

The problem is that those who abuse the system to classify (or sometimes to selectively declassify) information improperly recognize no such constraint. This discrepancy is vexatious.

It means that the checks and balances of the current system are most effective when they are least necessary. When everyone is acting in good faith and with an honest commitment to shared (constitutional) values, most disagreements can be resolved over time. Some compromise is usually possible.

But when good faith and principled self-restraint are lacking, and one side aims to maximize its power at any cost, the current structure of checks and balances has proved to be largely helpless.

Even if the ISCAP had agreed to consider Senator Murphy’s classification challenge, and if it had actually agreed with him that all or part of the War Powers Act notification concerning the Soleimani killing was not properly classified, that might not have been the end of the story.

“Panel decisions are committed to the discretion of the Panel,” according to the executive order (sect. 5.3e), “unless changed by the President.” But that means that a hypothetical ISCAP decision to declassify the notification could be overruled by the same White House that classified the whole thing in the first place.

So while good policies are necessary, they are not enough. For our constitutional system of government to work, we also need officials who are, if not the “angels” that James Madison spoke of, at least dedicated public servants who share a common purpose.

Senator Murphy’s office said that he would soon introduce legislation to authorize and require the ISCAP to consider classification challenges from Congress.

* * *

The current infrastructure for declassifying classified records that are no longer sensitive is already being overwhelmed by a deluge of historical records that are accumulating faster than they can be processed. This situation was discussed in a September 9 hearing before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and is the subject of new legislation (S. 3733) introduced by Senators Wyden and Moran.

That is an issue of efficiency and productivity that probably has a technological solution, as the Public Interest Declassification Board has argued.

A harder problem is over-classification, in which information is classified improperly or unnecessarily, or at a higher level than is warranted. Such classification errors can be corrected, at least hypothetically, through classification challenges, Freedom of Information Act requests, and other means.

A still harder problem concerns information that is properly classified — in the sense that it meets the criteria of the executive order — but nevertheless belongs in the public domain because of its fundamental policy importance. Examples include classified reports of torture, mass surveillance, or foreign election interference.

To the extent that such information is “properly classified” in a formal sense, it is currently beyond the reach of the Freedom of Information Act, mandatory declassification review, or classification challenges. When it does become public, that is often due to unauthorized disclosures. While agency heads may declassify classified information in the public interest as a matter of discretion (under section 3.1d of the executive order), they rarely do so and there is no mechanism for asking or inducing them to.

So along with adequate basic functionality and improved procedures for challenging improper classification, any future classification system also needs to tackle the problem of “properly classified” information that should not be classified.

Crisis of Credibility in Secrecy Policy

Obsolete secrecy procedures and growing political abuse have left the national security classification system in a state of disarray and dysfunction.

Most government agencies “still rely on antiquated information security management practices,” according to a new annual report from the Information Security Oversight Office (ISOO). “These practices have not kept pace with the volume of digital data that agencies create.”

“Agencies are not applying or testing advanced technologies that would enable more precise classification and declassification, facilitate information sharing, and improve national security,” the ISOO report to the President said. “Classification and declassification actions are still performed manually, which is neither sustainable nor desirable in the digital age.”

“As the volume of records requiring [declassification] review increases, agencies are making more errors, putting Classified National Security Information at risk and eroding trust in the system,” ISOO said.

As damning as these and other ISOO findings may be, they hardly begin to capture the crisis of credibility that is facing the classification system today.

An effective classification system depends on a presumption of good faith on the part of classifiers, checked by independent oversight, and some consensual understanding of the meaning of national security. All of these factors are in doubt, absent, or undergoing swift transformation. Meanwhile, classification today is openly wielded as an instrument of political power.

“Conversations with me, they’re highly classified,” said President Trump last week. “I told that to the Attorney General before. I will consider every conversation with me, as President, highly classified.”

That remark is a wild departure from previous policy. However broadly it may have been construed in the past, classification was always supposed to apply to information that was plausibly related to national security (a necessary condition, though not a sufficient one). Even the most sensitive conversations with the President about tax policy or health care, for example, could not have been considered classified information.

In this case, President Trump was objecting to the publication of the new book by former national security adviser John Bolton, which he dismissed at the same time as a “compilation of lies and made-up stories.”

But Bolton’s lies, if that’s what they were, would not normally qualify as classified information either.

In principle, it’s possible that “lies and made-up stories” could be classified, though only to the extent that they were generated by the government itself (perhaps in the form of cover stories, or other official statements of misdirection). But any lies that Bolton might tell on his own are beyond the scope of classification, since they are not “owned by, produced by or for, or. . . under the control of” the US Government, as required by the executive order on classification.

President Trump may or may not understand such rudiments of national security classification. But by twisting classification policy into a weapon for political vendettas, the President is discrediting the classification system and accelerating its disintegration.

As for Bolton, the astonishing fact is that he is the second of Trump’s national security advisors (after Gen. Michael Flynn) to be accused of lying and criminal activity.

“If the [Bolton] book gets out, he’s broken the law,” the President said. “And I would think that he would have criminal problems.” Indeed, a court said on Saturday that Bolton might have “expose[d] himself to criminal liability.”

Second only to the President, the national security advisor is really the principal author and executor of classification policy. So when NSAs like Flynn and Bolton are disgraced (or worse), their disrepute reflects upon and attaches to the classification system to some degree.

Ironically, Mr. Bolton was more attentive to and more engaged in classification policy than many of his predecessors. He makes a tacit appearance (unnamed) in the new ISOO annual report, which notes: “In FY 2018, the ISCAP [Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel] received a request from the National Security Advisor to resolve a declassification dispute between the Departments of Defense and State.” That action, to Bolton’s credit, freed up all or parts of 60 documents for publication in the Foreign Relations of the United States series, over the objections of the Department of Defense.

The way to begin restoring credibility to classification policy is not hard to envision, though it may be difficult or impossible to implement under current circumstances. Like law enforcement, the classification system needs to be insulated from partisan political interference. Classification policy needs to adhere to well-defined national security principles (though the scope and application of these principles will be debatable). A properly functioning classification and declassification system will prove its integrity by sometimes producing outcomes that are politically unwelcome or inconvenient to the Administration. And since errors are inevitable, the classification system also requires a robust oversight and error-correction process.

* * *

Last week, the Senate Intelligence Committee blocked an effort by Senator Ron Wyden to restructure and strengthen the declassification system. A Wyden amendment to the FY 2021 intelligence authorization act would have designated the Director of National Intelligence as the Executive Agent for declassification, tasking him to establish and carry out government-wide declassification requirements. The Wyden amendment failed 7-8 with all Republican members opposed.

By rejecting his amendment (without offering any alternative), the Committee “failed to reform a broken, costly declassification system,” Sen. Wyden said in a dissenting statement appended to the June 17 report on the intelligence bill.

* * *

While dismissing concerns about classification policy, the Senate Intelligence Committee roused itself to address the threat from unidentified flying objects, an issue that it said requires more focused government attention.

The Committee called on the Director of National Intelligence to provide detailed reporting on “unidentified aerial phenomena (also known as ‘anomalous aerial vehicles’), including observed airborne objects that have not been identified.”

“The Committee remains concerned that there is no unified, comprehensive process within the Federal Government for collecting and analyzing intelligence on unidentified aerial phenomena, despite the potential threat,” the new Committee report said.

PIDB Urges Modernization of Classification System

How can the national security classification and declassification system be fixed?

That depends on how one defines the problem that needs fixing. To the authors of a new report from the Public Interest Declassification Board (PIDB), the outstanding problem is the difficulty of managing the expanding volume of classified information and declassifying a growing backlog of records.

“There is widespread, bipartisan recognition that the Government classifies too much information and keeps it classified for too long, all at an exorbitant and unacceptable cost to taxpayers,” said the PIDB, a presidential advisory board. Meanwhile, “Inadequate declassification contributes to an overall lack of transparency and diminished confidence in the entire security classification system.”

The solution to this problem is to employ technology to improve the efficiency of the classification and declassification processes, the PIDB said.

“The time is ripe for envisioning a new approach to classification and declassification, before the accelerating influx of classified electronic information across the Government becomes completely unmanageable,” the report said. “The Government needs a paradigm shift, one centered on the adoption of technologies and policies to support an enterprise-level, system-of-systems approach.”

See A Vision for the Digital Age: Modernization of the U.S. National Security Classification and Declassification System, Public Interest Declassification Board, May 2020.

The report’s diagnosis is not new and neither is its call for employing new technology to improve classification and declassification. The PIDB itself made similar recommendations in a 2007 report.

Recognizing the persistent lack of progress to date, the new report therefore calls for the appointment of an Executive Agent who would have the authority and responsibility for designing and implementing a newly transformed classification system. (The Director of National Intelligence, who is already Security Executive Agent for security clearance policy, would be a likely choice.)

Those who care enough about these issues to read the PIDB report will find lots of interesting commentary along with plenty to doubt or disagree with. For example, in my opinion:

* The useful idea of appointing an Executive Agent is diminished by making him or her part of an Executive Committee of agency leaders. The whole point of creating a “czar”-like Executive Agent is to reduce the friction of collective decision making and to break through the interagency impasse. An Executive Committee would make that more difficult.

* The PIDB report would oddly elevate the Archivist of the United States, who is not even an Original Classification Authority, into a central role “in modernizing the systems used across agencies for the management of classified records.” That doesn’t make much sense. (An official said the intended purpose here was merely to advance the mission of the Archives in preserving historical records.)

* The report equivocates on the pivotal question of whether or not (or for how long) agencies should retain “equity” in, or ownership of, the records they produce.

* The report does not address resource issues in a concrete way. How much money should be invested today to develop the recommended technologies in order to reap savings five and ten years from now? It doesn’t say. Who should supply the classified connectivity among classifying agencies that the report says is needed? Exactly which agency should request the required funding in next year’s budget request? That is not discussed, and so in all likelihood it is not going to happen.

But the hardest, most stubborn problem in classification policy has nothing to do with efficiency or productivity. What needs updating and correcting, rather, are the criteria for determining what is properly classified and what must be disclosed. And since there is disagreement inside and outside government about many specific classification actions — e.g., should the number of US troops in Afghanistan be revealed or not? — a new mechanism is needed to adjudicate such disputes. This fundamental issue is beyond the scope of the PIDB report.

The Public Interest Declassification Board will hold a virtual public meeting on June 5 at 11 am.

Modernization of Secrecy System is Stalled

Today’s national security classification system “relies on antiquated policies from another era that undercut its effectiveness today,” the Information Security Oversight Office told the President in a report released yesterday.

Modernizing the system is a “government-wide imperative,” the new ISOO annual report said.

But that is a familiar refrain by now. It is much the same message that was delivered with notable urgency by ISOO in last year’s annual report which found that the secrecy system is “hamstrung by old practices and outdated technology.”

The precise nature of the modernization that is needed is a subject of some disagreement. Is it a matter of improving efficiency in order to cope with expanding digital information flows? Or have the role of secrecy and the proper scope of classification changed in a fundamental way?

Whatever the goal, no identifiable progress has been made over the past year in overcoming those obsolete practices, and no new investment has been made in a technology strategy to help modernize national security information policy. In fact, ISOO’s own budget for secrecy oversight has been reduced.

Even agencies that are making use of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, and predictive analytics in other areas have not considered their application to classification or declassification, ISOO said. “These technologies remain untapped in this area.”

At some point, the failure to update secrecy policy becomes a choice to let the secrecy system fail.

“We’re ringing the alarm bells as loud as we can,” said ISOO director Mark A. Bradley.

Leaks of Classified Info Surge Under Trump

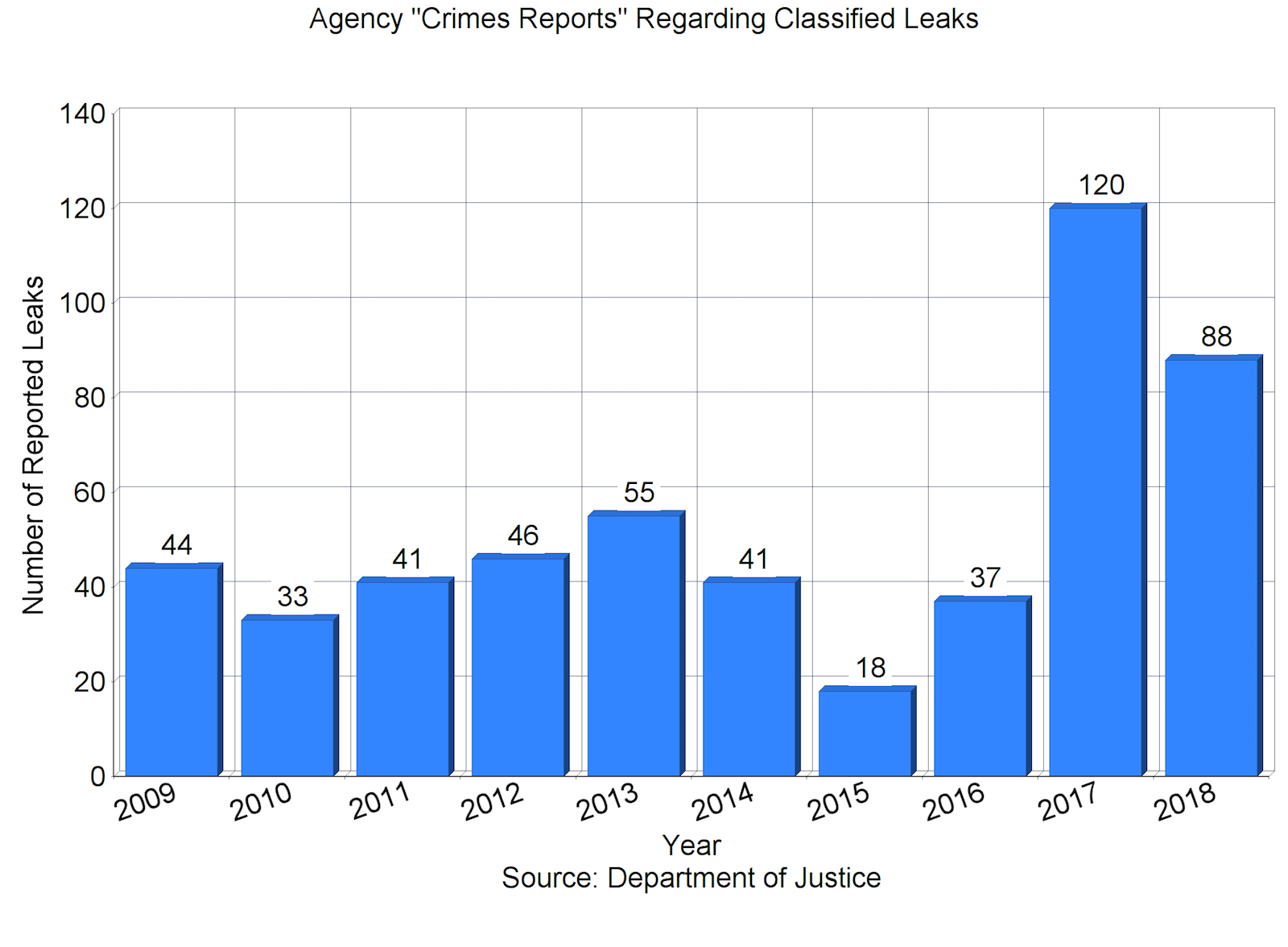

The number of leaks of classified information reported as potential crimes by federal agencies reached record high levels during the first two years of the Trump Administration, according to data released by the Justice Department last week.

Agencies transmitted 120 leak referrals to the Justice Department in 2017, and 88 leak referrals in 2018, for an average of 104 per year. By comparison, the average number of leak referrals during the Obama Administration (2009–2016) was 39 per year.

There are a “staggering number of leaks,” then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions said at an August 4, 2017 briefing about efforts to prevent the unauthorized disclosures.

“Referrals for investigations of classified leaks to the Department of Justice from our intelligence agencies have exploded,” AG Sessions said at that time. He outlined several steps that the Administration would take to combat leaks of classified information, including tripling the number of active leak investigations by the FBI.

“We had about nine open investigations of classified leaks in the last 3 years,” he told the House Judiciary Committee at a November 2017 hearing. “We have 27 investigations open today.” (Some of those investigations pertain to leaks that occurred before President Trump took office.)

“We intend to get to the bottom of these leaks. I think it reached—has reached epidemic proportions. It cannot be allowed to continue,” Sessions said then, “and we will do our best effort to ensure that it does not continue.”

But it has continued. Despite preventive efforts, the 2018 total of 88 leak referrals was still higher than any reported pre-Trump figure. (The previous high in recent decades had been 55 referrals in 2013 and in 2007. The lowest was 18 in 2015.)

*

Not all leaks of classified information generate such criminal referrals. Disclosures that are inadvertent, insignificant, or officially authorized would not be reported to the Justice Department as suspected crimes.

Meanwhile, only a fraction of the classified leaks that are reported by agencies ever result in an investigation, and only a portion of those lead to identification of a suspect and even fewer to a prosecution.

“While DOJ and the FBI receive numerous media leak referrals each year, the FBI opens only a limited number of investigations based on these referrals,” the FBI told Congress in 2009. “In most cases, the information included in the referral is not adequate to initiate an investigation.”

The newly released aggregate data on classified leak referrals serve as a reminder that leaks of classified information are a “normal,” predictable occurrence. There is not a single year in the past decade and a half for which data are available when there were no such criminal referrals.

But the data as released leave several questions unanswered. They do not reveal how many of the referrals actually triggered an FBI investigation. They do not indicate whether the leaks are evenly distributed across the national security bureaucracy or concentrated in one or more “problem” agencies (or congressional committees). And they do not distinguish between leaks that simply “hurt our country,” as the Attorney General put it, and those that are complicated by a significant public interest in the information that was disclosed.

Classified Anti-Terrorist Ops Raise Oversight Questions

Last February, the Secretary of Defense initiated three new classified anti-terrorist operations intended “to degrade al Qaeda and ISIS-affiliated terrorists in the Middle East and specific regions of Africa.”

A glimpse of the new operations was provided in the latest quarterly report on the U.S. anti-ISIS campaign from the Inspectors General of the Department of Defense, Department of State, and US Agency for International Development.

The three classified programs are known as Operation Yukon Journey, the Northwest Africa Counterterrorism overseas contingency operation, and the East Africa Counterterrorism overseas contingency operation.

Detailed oversight of these programs is effectively led by the DoD Office of Inspector General rather than by Congress.

“To report on these new contingency operations, the DoD OIG submitted a list of questions to the DoD about topics related to the operations, including the objectives of the operations, the metrics used to measure progress, the costs of the operations, the number of U.S. personnel involved, and the reason why the operations were declared overseas contingency operations,” the joint IG report said.

DoD provided classified responses to some of the questions, which were provided to Congress.

But “The DoD did not answer the question as to why it was necessary to designate these existing counterterrorism campaigns as overseas contingency operations or what benefits were conveyed with the overseas contingency operation designation.”

Overseas contingency operations are funded as “emergency” operations that are not subject to normal procedural requirements or budget limitations.

“The DoD informed the DoD OIG that the new contingency operations are classified to safeguard U.S. forces’ freedom of movement, provide a layer of force protection, and protect tactics, techniques, and procedures. However,” the IG report noted, “it is typical to classify such tactical information in any operation even when the overall location of an operation is publicly acknowledged.”

“We will continue to seek answers to these questions,” the IG report said.

Accounting Board Okays Deceptive Budget Practices

Government agencies may remove or omit budget information from their public financial statements and may present expenditures that are associated with one budget line item as if they were associated with another line item in order to protect classified information, the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board concluded last week.

Under the newly approved standard, government agencies may “modify information required by other [financial] standards” in their public financial statements, omit otherwise required information, and misrepresent the actual spending amounts associated with specific line items so that classified information will not be disclosed. (Accurate and complete accounts are to be maintained separately so that they may be audited in a classified environment.)

See Classified Activities, Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards (SFFAS) 56, Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board, October 2018.

The new policy was favored by national security agencies as a prudent security measure, but it was opposed by some government overseers and accountants.

Allowing unacknowledged modifications to public financial statements “jeopardizes the financial statements’ usefulness and provides financial managers with an arbitrary method of reporting accounting information,” according to comments provided to the Board by the Department of Defense Office of Inspector General.

Properly classified information should be redacted, not misrepresented, said the accounting firm Kearney & Company. “Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) should not be modified to limit reporting of classified activities. Rather, GAAP reporting should remain the same as other Federal entities and redacted for public release or remain classified.”

The new policy, which extends deceptive budgeting practices that have long been employed in intelligence budgets, means that public budget documents must be viewed critically and with a new degree of skepticism.

A classified signals intelligence program dubbed “Vesper Lillet” that recently became the subject of a fraud indictment was ostensibly sponsored by the Department of Health and Human Services, but in reality it involved a joint effort of the National Reconnaissance Office and the National Security Agency.

See “Feds allege contracting fraud within secret Colorado spy warehouse” by Tom Roeder, The Gazette (Colorado Springs), October 5, 2018.