Investing in “Privacy-at-the-Sensor” Civic Technologies to Advance Next-Gen American Infrastructure

Summary

The National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Department of Energy (DOE) should invest in a cohort of civic technologies that advance the next generation of American infrastructure while prioritizing individual privacy protections.

Our nation’s infrastructure is in urgent need of upkeep and replacement. The next generation of American infrastructure should be designed and built to be resilient, energy efficient, and integrate harmoniously with network communications, autonomous vehicles, and other “smart” systems. Emerging civic technologies — such as sensors, computers, and software that can support billing and payment, manage public resources, monitor integrity of structures, track traffic flows, and more — can improve the performance of future infrastructure and improve community livability. However, the public often believes that civic technologies invade individual privacy and enrich tech companies. Public distrust has disrupted multiple civic-technology projects around the world.

The federal government should invest in a suite of research and development (R&D) activities to develop new, sensor-based civic technologies that inherently preserve privacy in a manner verifiable by citizens. The federal government should also invest in complementary activities to promote adoption and acceptance of such “privacy-at-the-sensor” technologies. Such activities could include setting standards for the privacy properties of civic technologies, establishing technology test beds, funding public grants to encourage adoption of privacy-preserving sensing technologies, and creating partnerships with external stakeholders interested in civic technologies.

Digital IDs for Securing Personal Information

Digital driver’s licenses can offer greater protection of personal information, and some states are already skipping the line at the DMV

From submitting personal information over email to scheduling telehealth appointments, safe and verifiable forms of personal identification are crucial. While physical driver’s licenses are standard, they can be stolen or forged. To improve security and ease of use, some states have developed digital driver’s license programs, and even the federal government has signaled its interest in digital IDs. The most common form of digital ID – a mobile driver’s license, or mDL – allows the license holder to authorize the sharing of only those personal details that are absolutely necessary for specific types of transactions. For example, when purchasing alcohol at a liquor store, a mDL could show only a person’s name and age, and hide other personal information, such as an address, and even an exact birth date. Furthermore, forging digital identification is more difficult than forging traditional ID because of public key cryptography, where virtual information, in this case a driver’s license, is encrypted, and can only be decrypted through a virtual verification system that authenticates the ID. This technology is more advanced than the barcodes used to verify identification on traditional driver’s licenses. These systems can help prevent forgery and reduce underage purchases of products such as alcohol and tobacco.

Beyond typical uses of physical driver’s licenses, mDLs could be helpful in the healthcare and finance sectors. Applying digital identification to patient records can increase the accuracy of electronic health records, and also make medical records more accessible to patients. A streamlined authentication process enabled by digital identification can improve banks’ fraud management and support their compliance with verification guidelines that foster financial companies’ abilities to identify their customers as potential money laundering risks. Deploying verified forms of digital identification can improve users’ experiences and modernize operations for institutions moving toward digital services.

Given the success of mDLs in states like Illinois, Oklahoma, and Louisiana, Congress is laying the groundwork for the widespread adoption of digital identification. In Louisiana, drivers can get a mDL by paying $5.99 to download the LA Wallet app, and since the app’s launch in 2018, it is being used by 670,000 residents – nearly 20% of all Louisiana drivers. Louisianans can also upload their COVID-19 vaccination status into the app, or verify their identities when registering for the Disaster Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program in the wake of a hurricane. LA Wallet is the first mDL app legalized by a state government, and Louisiana has set the standard for how mDLs could operate nationally. In December 2020, Congress passed the REAL ID Modernization Act, which updated federal identification guidelines, authorized the use of electronic driver’s licenses, and established the beginnings of protections against unwarranted smartphone seizure by law enforcement when using a mobile identification app. The act gives states a deadline of October 1, 2021 for all Americans to be issued a REAL ID-compliant driver’s license, which can be switched to a REAL ID-compliant mDLs.

These proposed digital solutions for identification are not without their downsides. mDLs have been flagged by civil society groups, like the American Civil Liberties Union, that are raising concerns about surveillance risks. One such risk is unwarranted police access to non-ID content on phones when mobile driver’s licenses are presented to police officers during traffic stops. Another risk is that because the licenses would be linked to the Department of Motor Vehicles and an app developer, the issuer or verifier could use their direct access to personal information, such as where people are shopping or visiting, for unlawful purposes – like the federal government observing and prosecuting activity, such as purchasing marijuana, that is legal in a particular state. Additionally, if this technology becomes a legal requirement rather than an opt-in choice, it could further disadvantage people in vulnerable communities who do not own smartphones.

A mDL is just one option for more secure identification systems, and in order to make mDLs widely available, issues such as (i) having reliable internet access to use the app, (ii) the affordability of smartphones should mDLs become required, and (iii) the guarantee that user information is secure from unauthorized tracking must be addressed before a federalized system is put in place.

This CSPI Science and Technology Policy Snapshot expands upon a scientific exchange between Congressman Bill Foster (D, IL-11) and his new FAS-organized Science Council.

Countering China’s Monopolization of African Nations’ Digital Broadcasting Infrastructure

Summary

The majority of people living in the African continent access their news and information from broadcasted television and radio. As African countries follow the directive from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) to migrate from analog to digital broadcasting, there is an urgent need to sequester the continent’s broadcast signal distributors (BSDs).1 BSDs provide the necessary architecture for moving broadcasted content (e.g., television and radio) into the digital sphere.

Most BSDs in Africa are owned and operated by Chinese companies. Of 23 digitally migrated countries, only four BSDs (Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, and Zimbabwe) are officially known to be outside the influence of China-based companies. The implicit capture of the BSD marketplace by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) threatens African democracies and could undermine international partnerships among African nations and with the United States. Excessive Chinese control over African BSDs also raises security concerns and impedes establishment of a robust, competitive, and rules-based global market in communications infrastructure.

The United States should therefore consider the following actions to support African civil society, media regulators, and legislators in securing an information ecosystem that advances democratic values:

- Creating a Program on Traditional and Digital Media Literacy within the Department of State’s Bureau of African Affairs 2021 Africa Regional Democracy Fund.

- Supporting a Regional Digital Broadcasting Coordinator for each of the five African sub-regional groups, via the Digital Ecosystem Fund and the Digital Connectivity and Cybersecurity Partnership.

- Enhancing U.S.-based competitiveness by expanding the Digital Attaché Program to promote alternative BSDs in Africa.

- Leveraging the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit proposed in the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act to advance a regulatory and liability framework governing the relationships among BSDs, content producers, and constitutional protections.

Police Misconduct and Violence: Let the Data Talk

Limited insight into police misconduct makes it difficult to improve policing, but a national registry could help

Police misconduct and violence have vaulted to the forefront of the national discourse on civil rights and safety. Researchers have found that Black people are three and a half times more likely to be killed by police when not holding a weapon, or not attacking, than white people. Tragically, one out of every thousand Black men in the U.S. will be killed by police violence.

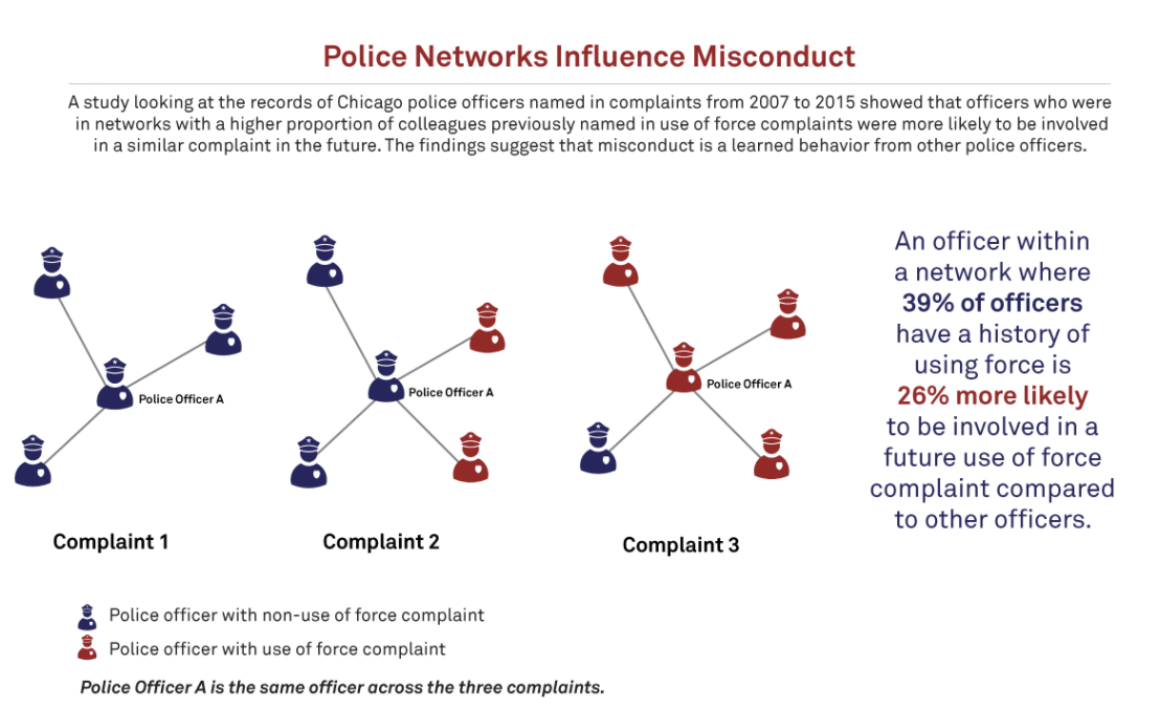

While the removal of offending police officers from their positions would be a straightforward solution, it is rarely easy to permanently expel bad actors from police departments. Yale researchers found that police officers who are fired for misconduct from one department are often hired by another department within three years. These officers also tend to move to smaller departments that serve communities with greater numbers of people of color. To make matters worse, these officers’ bad behavior can spread through the departments in which they work. For example, as depicted in Figure 1, officers involved in excessive force complaints were more likely to work with officers with histories of similar complaints. Because of this behavioral trend and the difficulty of removing transgressive officers, it is unsurprising that law enforcement misconduct and violence remains largely unresolved by police departments or policymakers.

Officers with use of force complaints on their records can set a trend of behavior in their departments where other officers become more likely to receive use of force complaints in the future. Figure reproduced from Ouellet, Hasimi, Gravel, and Papachristos 2019, Criminology and Public Policy.

To keep harmful police misconduct from spreading throughout new police departments, some researchers and policymakers suggest developing a national registry for police behavior. This independent registry would catalogue misconduct among police officers and be available for policymakers and police department leadership to use for decision-making about hiring, training, or policing duties. Currently, a less comprehensive National Decertification Index records officers who have engaged in misconduct severe enough to lose their state policing certifications – typically a requirement to work in a police department. The goal of the Index is to prevent former police officers who were guilty of misconduct from being rehired without their new departments knowing about their prior misconduct. Unfortunately, there is a significant amount of police misconduct that does not result in decertification, such as illegal searches and use of excessive force, but that is still important to track. Tracking all police misconduct in a national registry for police behavior could serve as a significant resource in the effort to reduce destructive policing practices.

However, a national registry of police behavior would face several challenges. For example, each police department has different protocols for complaint records. And even when officer misconduct is reported and addressed by the community, recommendations from civilian review boards on officer misconduct are adopted infrequently. Police unions can also create obstacles to weeding out bad actors in police departments. For a national registry of police behavior to be maximally effective in helping to reform policing, additional measures need to be taken in parallel.

Policymakers, community members, and police departments are exploring policy options for policing, and national registries of misconduct and complaints could help indicate trends of behavior in officers, aiding decision-makers in their pursuit of more just policing systems.

This CSPI Science and Technology Policy Snapshot expands upon a scientific exchange between Congressman Bill Foster (D, IL-11) and his new FAS-organized Science Council.

Creating an API Standard for Election Administration Systems to Strengthen U.S. Democracy

Summary

To bring nationwide access to voter tools, the Biden-Harris administration should direct the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to establish a standard application programming interface (API) for election administration systems.

Our democracy is most representative when the greatest number of Americans vote, but access is hindered by manual, form-based operations that make it difficult for citizens to register to vote or access a ballot. As Americans faced a global pandemic and an overwhelmed postal service, the 2020 election amplified the importance of digital tools for voters to register, apply for absentee ballots, and track their ballot status. It also highlighted the deficiencies in (or lack of) these capabilities from locality to locality. Further, state legislatures have begun passing sweeping voter suppression measures that further limit ballot access.

With the next federal election rapidly approaching in 2022, the time to take steps at the federal level to expand voting access is now. While proposed legislation would mandate making these functions available online, without incentives or standards, these tools would remain available only on local government websites, which suffer from discoverability and usability hurdles. Creating a standard API for election administration systems will enable civic groups and other outside organizations to create consistent, discoverable and innovative nationwide voter tools that interoperate directly with local voter rolls, resulting in a more participatory electorate and a stronger, more representative democracy.

Expanding the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to Fund Local News

The Biden administration can respond to the rise in disinformation campaigns and ensure the long-term viability of American democracy by championing an expanded Corporation for Public Broadcasting to transform, revive, and create local public service newsrooms around the country.

Local newsrooms play key roles in a democracy: informing communities, helping set the agenda for local governments, grounding national debates in local context, and contributing to local economies; so it is deeply troubling that the market for local journalism is failing in the United States. Lack of access to credible, localized information makes it harder for communities to make decisions, hampers emergency response, and creates fertile ground for disinformation and conspiracy theories. There is significant, necessary activity in the academic, philanthropic, and journalism sectors to study and document the hollowing out of local news and sustain, revive, and transform the landscape for local journalism. But the scope of the problem is too big to be solely addressed privately. Maintaining local journalism requires treating it as a public good, with the scale of investment that the federal government is best positioned to provide.

The United States has shown that it can meet the opportunities and challenges of a changing information landscape. In the 1960s, Congress established the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), creating a successful and valuable public media system in response to the growth of widely available corporate radio and TV. But CPB’s purview hasn’t changed much since then. Given the challenges of today’s information landscape, it is time to reimagine and grow CPB.

The Biden administration should work with Congress to revitalize local journalism in the United States by:

- Passing legislation to evolve the CPB into an expanded Corporation for Public Media. CPB’s current mandate is to fund and support broadcast public media. An expanded Corporation for Public Media would continue to support broadcast public media while additionally supporting local, nonprofit, public-service-oriented outlets delivering informational content to meet community needs through digital, print, or other mediums.

- Doubling CPB’s annual federal budget allocation, from $445 to $890 million, to fund greater investment in local news and digital innovation. The local news landscape is the subject of significant interest from philanthropies, industry, communities, and individuals. Increased federal funding for local, nonprofit, and public-service-oriented news outlets could stimulate follow-on investment from outside of government.

Challenge and Opportunity

Information systems are fracturing and shifting in the United States and globally. Over the past 20 years, the Internet disrupted news business models and the national news industry consolidated; both shifts have contributed to the reduction of local news coverage. American newsrooms have lost almost a quarter of their staff since 2008. Half of all U.S. counties have only one newspaper or information equivalent, and many counties have no local information source. The media advocacy group Free Press estimates that the national “reporting gap”, which they define as the wages of the roughly 15,000 reporting roles lost since the peak of journalism in 2005, stands at roughly $1 billion a year.

The depletion of reputable local newsrooms creates an information landscape ripe for manipulation. In particular, the shrinking of local newsrooms can exacerbate the risk of “data voids”, when good information is not available via online search and instead users find “falsehoods, misinformation, or disinformation”. In 2019, the Tow Center at the Columbia Journalism School documented 450 websites masquerading as local news outlets, with titles like the East Michigan News, Hickory Sun, and Grand Canyon Times But instead of publishing genuine journalism, these sites were distributing algorithmically generated, hyperpartisan, locally tailored disinformation. The growing popularity of social media as news sources or conduits to news sources — more than half of American adults today get at least some news from social media — compounds the problem by making it easier for disinformation to spread.

Studies show that the erosion of local journalism has negative impacts on local governance and democracy, including increased voter polarization, decreased accountability for elected officials to their communities, and decreased competition in local elections. Disinformation narratives that take root in the information vacuum left behind when local news outlets fold often disproportionately target and impact marginalized people and people of color. Erosion of local journalism also threatens public safety. Without access to credible and timely local reporting, communities are at greater risk during emergencies and natural disasters. In the fall of 2020, for instance, emergency response to wildfires threatening communities in Oregon was hampered by the spread of inaccurate information on social media. These problems will only become more pronounced if the market for local journalism continues to shrink.

These are urgent challenges and the enormity of them can make them feel intractable. Fortunately, history presents a path forward. By the 1960s, with the rise of widely available corporate TV and radio, the national information landscape had changed dramatically. At the time, the federal government recognized the need to reduce the potential harms and meet the opportunities that these information systems presented. In particular, then-Chair of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Newton Minow called for more educational and public-interest programming, which the private TV market wasn’t producing.18 Congress responded by passing the Public Broadcasting Act in 1967, creating the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). CPB is a private nonprofit responsible for funding public radio and television stations and public-interest programming. (Critically, CPB itself does not produce content.) CPB has a mandate to champion diversity and excellence in programming, serve all American communities, ensure local ownership and independent operation of stations, and shield stations from the possibility of political interference. Soon after its creation, CPB established the independent entities of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and National Public Radio (NPR).

CPB, PBS, NPR, and local affiliate stations collectively developed into the national public media system we know today. Public media is explicitly designed to fill gaps not addressed by the private market in educational, youth, arts, current events, and local news programming, and to serve all communities, including populations frequently overlooked by the private sector. While not perfect, CPB has largely succeeded in both objectives when it comes to broadcast media. CPB supports1 about 1,500 public television and radio broadcasters, many of which produce and distribute local news in addition to national news. CPB funds much-needed regional collaborations that have allowed public broadcasters to combine resources, increase reporting capacity, and cover relevant regional and localized topics, like the opioid crisis in Appalachia and across the Midwest. CPB also provides critical — though, currently too little — funding to broadcast public media for historically underserved communities, including Black, Hispanic, and Native communities.

Public media and CPB’s funding and support is a consistent bright spot for the struggling journalism industry.25 More than 2,000 American newspapers closed in the past 15 years, but NPR affiliates added 1,000 local part- and full-time journalist positions from 2011–2018 (though these data are pre-pandemic).26 Trust in public media like PBS remains high compared to other institutions; and local news is more trusted than national news.27,28 There is clear potential for CPB to revive and transform the local news landscape: it can help to develop community trust, strengthen democratic values, and defend against disinformation at a time when all three outcomes are critical.

Unfortunately, the rapid decline of local journalism nationwide has created information gaps that CPB — an institution that has remained largely unchanged since its founding more than 50 years ago — does not have the capacity to fill. Because its public service mandate still applies only to broadcasters, CPB is unable to fund stand-alone digital news sites. The result is a dearth of public-interest newsrooms with the skills and infrastructure to connect with their audiences online and provide good journalism without a paywall. CPB also simply lacks sufficient funding to rebuild local journalism at the pace and scope needed. Far too many people in the United States — especially members of rural and historically underserved communities — live in a “news desert”, without access to any credible local journalism at all.2

The time is ripe to reimagine and expand CPB. Congress has recently demonstrated bipartisan willingness to invest in local journalism and public media. Both major COVID-19 relief packages included supplemental funding for CPB. The American Rescue Act and the CARES Act provided $250 million and $75 million, respectively, in emergency stabilization funds for public media. Funds were prioritized for small, rural, and minority-oriented public-media stations.30 As part of the American Rescue Plan, smaller news outlets were newly and specifically made eligible for relief funds—a measure that built on the Local News and Emergency Information Act of 2020 previously introduced by Senator Maria Cantwell (D-WA) and Representative David Cicilline (D-RI) and supported by a bipartisan group. Numerous additional bills have been proposed to address specific pieces of the local news crisis. Most recently, Senators Michael Bennet (D-CO), Amy Klobuchar (D-MI), and Brian Schatz (D-HI), along with Representative Marc Veasy (DTX) reintroduced the Future of Local News Commission Act, calling for a commission “to study the state of local journalism and offer recommendations to Congress on the actions it can take to support local news organizations”.

These legislative efforts recognize that while inspirational work to revitalize local news is being done across sectors, only the federal government can bring the level of scale, ambition, and funding needed to adequately address the challenges laid out above. Reimagining and expanding CPB into an institution capable of bolstering the local news ecosystem is necessary and possible; yet it will not be easy and would bring risks. The United States is amid a politically uncertain, difficult, and even violent time, with a rapid, continued fracturing of shared understanding. Given how the public media system has come under attack in the “culture wars” over the decades, many champions of public media are understandably wary of considering any changes to the CPB and public media institutions and initiatives. But we cannot afford to continue avoiding the issue. Our country needs a robust network of local public media outlets as part of a comprehensive strategy to decrease blind partisanship and focus national dialogues on facts. Policymakers should be willing to go to bat to expand and modernize the vision of a national public media system first laid out more than fifty years ago.

Plan of Action

The Biden administration should work with Congress to reimagine CPB as the Corporation for Public Media: an institution with the expanded funding and purview needed to meet the information challenges of today, combat the rise of disinformation, and strengthen community ties and democratic values at the local level. Recommended steps towards this vision are detailed below.

Recommendation 1. Expand CPB’s Purview to Support and Fund Local, Nonprofit, Public Service Newsrooms.

Congress should pass legislation to reestablish the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) as the Corporation for Public Media (CPM), expanding the Corporation’s purview from solely supporting broadcast outlets to additionally supporting local, nonprofit newsrooms of all types (digital, print, broadcast).

The expanded CPM would retain all elements of the CPB’s mandate, including “ensuring universal access to non-commercial, high-quality content and telecommunications services that are commercial free and free of charge,” with a particular emphasis on ensuring access in rural, small town, and urban communities across the country. Additionally, CPB “strives to support diverse programs and services that inform, educate, enlighten and enrich the public”, especially addressing the needs of underserved audiences, children, and minorities.

Legislation expanding the CPB into the CPM must include criteria that local, nonprofit, public-service newsrooms would need to meet to be considered “public media” and become eligible for federal funding and support. Broadly, local, nonprofit newsrooms should mean nonprofit or noncommercial newsrooms that cover a region, state, county, city, neighborhood, or specific community; it would not include individual reporters, bloggers, documentarians, etc. Currently, CPB relies on FCC broadcasting licenses to determine which stations might be eligible to be considered public broadcasters. The Public Broadcasting Act lays out additional eligibility requirements, including an active community advisory board and regularly filed reports on station activities and spending. Congress should build on these existing requirements when developing eligibility criteria for CPM funding and support.

In designing eligibility criteria, Congress could also draw inspiration from the nonprofit Civic Information Consortium (CIC) being piloted in New Jersey. The CIC is a partnership between higher education institutions and newsrooms in the state to strengthen local news coverage and civic engagement, seeded with an initial $500,000 in funding. The CPM could require that to be eligible for CPM funding, nonprofit public-service newsrooms must partner with local, accredited universities.39 Requiring that an established external institution be involved in local news endeavors selected for funding would (i) decrease risks of investing in new and untested newsrooms, (ii) leverage federal investment by bringing external capabilities to bear, and (iii) increase the impact of federal funding by creating job training and development opportunities for local students and workers. Though, of course, this model also brings its own risks, potentially putting unwelcome pressure on universities to act as public media and journalism gatekeepers.

An expanded CPM would financially support broadcast, digital, and print outlets at the local and national levels. Once eligibility criteria are established, clear procedures would need to be established for funding allocation and prioritization (see next section for recommended prioritizations). For instance, procedures should explain how factors such as demonstrated need and community referrals will factor into funding decisions. Procedures should also ensure that funding is prioritized towards local newsrooms that serve communities in “news deserts”, or places at risk of becoming news deserts, and historically underserved communities, including Black, Hispanic, Native, and rural communities.

Congress could consider tasking the proposed Future of Local News Act commission with digging deeper into how CPB could be evolved into the CPM in a way that best positions it to address the disinformation and local news crises. The commission could also advise on how to avoid two key risks associated with such an evolution. The first is the perpetual risk of government interference in public media, which CPB’s institutional design and norms have historically guarded against. (For example, there are no content or viewpoint restrictions on public media today—and there should not be in the future.) Second, expanding CPB’s mandate to include broadly funding local, nonprofit newsrooms would create a new risk that disinformation or propaganda sites, operating without journalistic practices, could masquerade as genuine news sites to apply for CPM funding. It will be critical to design against both of these risks. One of the most important factors in CPB’s success is its ethos of public service and the resulting positive norms; these norms and its institutional design are a large part of what makes CPB a good institutional candidate to expand. In designing the new CPM, these norms should be intentionally drawn on and renewed for the digital age.

Numerous digital outlets would likely meet reasonable eligibility criteria. One recent highlight in the journalism landscape is the emergence of many nonprofit digital outlets, including almost 300 affiliated with the Institute for Nonprofit News. (These sites certainly have not made up for the massive numbers of journalism jobs and outlets lost over the past two decades.) There has also been an increase in public media mergers, where previously for-profit digital sites have merged with public media broadcasters to create mixed-media nonprofit journalistic entities. As part of legislation expanding the CPB into the CPM, Congress should make it easier for public media mergers to take place and easier for for-profit newspapers and sites to transition to nonprofit status, as the Rebuild Local News Coalition has proposed.

Recommendation 2. Double CPB’s Yearly Appropriation from $445 to $890 million.

Whether or not CPB is evolved into CPM, Congress should (i) double (at minimum) CPB’s next yearly appropriation from $445 to $890 million, and (ii) appropriate CPB’s funding for the next ten years up front. The first action is needed to give CPB the resources it needs to respond to the local news and disinformation crises at the necessary scale, and the second is needed to ensure that local newsrooms are funded over a time horizon long enough to establish themselves, develop relationships with their communities, and attract external revenue streams (e.g., through philanthropy, pledge drives, or other models). The CPB’s current appropriation is sufficient to fund some percentage of station operational and programming costs at roughly 1,500 stations nationwide. This is not enough. Given that Free Press estimates the national “reporting gap” as roughly $1 billion a year, CPB’s annual budget appropriation needs to be at least doubled. Such increased funding would dramatically improve the local news and public media landscape, allowing newsrooms to increase local coverage and pay for the digital infrastructure needed to better meet audiences where they are—online. The budget increase could be made part of the infrastructure package under Congressional negotiation, funded by the Biden administration’s proposed corporate tax increases, or separately funded through corporate tax increases on the technology sector.

The additional appropriation should be allocated in two streams. The first funding stream (75% of the additional appropriation, or $667.5 million) should specifically support local public-service journalism. If Free Press’s estimates of the reporting gap are accurate, this stream might be able to recover 75% of the journalism jobs (somewhere in the range of 10,000 to 11,000 jobs) lost since the industry’s decline began in earnest—a huge and necessary increase in coverage. Initial priority for this funding should go to local journalism outlets in communities that have already become “news deserts”. Secondary priority should go to outlets in communities that are at risk of becoming news deserts and in communities that have been historically underserved by media, including Black, Hispanic, Native, and rural communities. Larger, well-funded public media stations and outlets should still receive some funding from this stream (particularly given their role in surfacing local issues to national audiences), but with less of a priority focus. This funding stream should be distributed through a structured formula — similar to CPB’s funding formulas for public broadcasting stations — that ensures these priorities, protects news coverage from government interference, and ensures high-quality news.

The second funding stream (25% of additional appropriation, or $222.5 million) should support digital innovation for newsrooms. This funding stream would help local, nonprofit newsrooms build the infrastructure needed to thrive in the digital age. Public media aims to be accessible and meet audiences where they are. Today, that is often online. Though the digital news space is dominated by social media and large tech companies, public media broadcasters are figuring out how to deliver credible, locally relevant reporting in digital formats. NPR, for instance, has successfully digitally innovated with platforms like NPR One. But more needs to be done to expand the digital presence of public media. CPB should structure this funding stream as a prize challenge or other competitive funding model to encourage further digital innovation.

Finally, the overall additional appropriation should be used as an opportunity to encourage follow-on investment in local news, by philanthropies, individuals, and the private sector. There is significant interest across the board in revitalizing American local news. The attention that comes with a centralized, federally sponsored effort to reimagine and expand local public media can help drive additional resources and innovation to places where they are most needed. For instance, philanthropies might offer private matches for government investment in local news. Such an initiative could draw inspiration from the existing and successful NewsMatch program, a funding campaign where individuals donate to a nonprofit newsroom and their donation is matched by funders and companies.

Conclusion

Local news is foundational to democracy and the flourishing of communities. Yet with the rise of the Internet and social media companies, the market for local news is failing. There is significant activity in the journalistic, philanthropic, and academic sectors to sustain, revive, and transform the local news landscape. But these efforts can’t succeed alone. Maintaining local journalism as a public good requires the scale of investment that only the federal government can bring.

In 1967, our nation rose to meet a different moment of disruption in the information environment, creating public media broadcasting through the Public Broadcasting Act. Today, there is a similar need for the Biden administration, Congress, and CPB to reimagine public media for the digital age. They should champion an expanded Corporation for Public Media to better meet communities’ information needs; counter the rising tide of disinformation; and transform, revive, and create local, public-service newsrooms around the country.

Mitigating Doxing Risks: Strategies to Prevent Online Threats from Translating to Offline Harms

Summary

The Biden-Harris Administration should act to address and minimize the risks of malicious doxing, given the rising frequency of online harassment inciting offline harms. This proposal recommends four parallel and mutually reinforcing strategies that can improve protections, enforcement, governance, and awareness around the issue.

The growing use of smartphones, social media, and other channels for finding and sharing information about people have made doxing increasingly widespread and dangerous in recent years. A 2020 survey by the Anti-Defamation League found that 44% of Americans reported experiencing online harassment. 28% of Americans reported experiencing severe online harassment, which includes doxing as well as sexual harassment, stalking, physical threats, swatting, and sustained harassment. In addition, a series of disturbing events in 2020 suggest that some instances of coordinated doxing efforts have reached a level of sophistication that poses a serious threat to U.S. national security. The pronounced spike in doxing cases against election officials, federal judges, and local government officials should serve as evidence for the severity and urgency of this issue. Meanwhile, private citizens have faced elevated doxing risks as disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic and tensions around contentious sociopolitical issues have provoked cycles of online harassment.

While several states have proposed anti-doxing bills over the past year, most states do not offer adequate protections for doxing victims or mechanisms to hold perpetrators accountable. The doxing regulations that do exist are inconsistent across state lines, and partially applicable federal laws—such as the Interstate Communications Statute and the Interstate Stalking Statute—neither fully address the doxing problem nor are sufficiently enforced. New federal legislation is a crucial step for ensuring that doxing risks and harms are appropriately addressed, and must come with complementary governance structures and enforcement capabilities in order to be effective.

Prioritize Funding for High-Speed Internet Connectivity that Rural Communities Can Afford to Adopt

Summary

Access to high-speed internet is essential for all Americans to participate in society and the economy. The American Jobs Plan (AJP) proposal to build high-speed broadband infrastructure to achieve 100% high-speed internet coverage is critical for reaching unserved and underserved communities. Yet widespread access to high-speed broadband infrastructure is insufficient. Widespread adoption is required for individuals and communities to realize the benefits of being online. Federal programs that have recently funded new broadband infrastructure—namely the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Connecting America Fund Phase II (CAF II) and Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF) reverse auctions—have not adequately tied the input of broadband infrastructure funding to the desired outcome of broadband adoption. Consequently, funding has gone to internet service providers (ISPs) that offer expensive internet service that communities are unlikely to adopt. To use the AJP’s broadband infrastructure funds most effectively, the Biden-Harris Administration should prioritize affordability in funding allocation and ensure that all recipients of federal subsidies, grants, or loans meet requirements for affordable service. Doing so will support widespread internet adoption and contribute to the AJP’s stated aims of reducing the price of internet service, holding ISPs accountable, and saving taxpayers money.

Section 230 Is Essential to the Internet’s Future

Summary

Section 230 is not a gift to Big Tech, and eliminating it will not solve the problems that Big Tech is causing. Those problems stem from a severe lack of competition. Repealing Section 230 will exacerbate those problems.

Section 230 is critical to the proper functioning of the Internet. To rein in Big Tech, the law should be supported, not weakened or repealed. The Trump Administration’s executive order on Section 230 should be repealed. Further, action to limit the power of large tech companies should be taken on three fronts: antitrust, privacy, and interoperability.

A Strategy to Blend Domestic and Foreign Policy on Responsible Digital Surveillance Reform

Summary

Modern data surveillance has been used to systematically silence free expression, destroy political dissidents, and track ethnic minorities before placement in concentration camps. China’s surveillance-export system is providing a model of authoritarian stability and security to the 80+ countries using its technology, a number that will grow in the aftermath of COVID-19 as the technology spreads to the half of the world still to come online. This technology is shifting the balance of power between democratic and autocratic governance. Meanwhile, the purported US model is un-democratic at best: a Wild West absent of accountability and full of black box, NDA-protected public-private partnerships between law enforcement and surveillance companies. Our system continues to oppress marginalized communities in the US, muddying our moral claims abroad with hypocrisy. Surveillance undermines the privacy of everyone, but not equally. Most citizens remain unaware of, unaffected by, or disinterested in the daily violence propagated by the unregulated acquisition and use of surveillance. The lack of coordination between state and local agencies and the federal government around surveillance has created a deeply unregulated surveillance-tech environment and a discordant international agenda. Digital surveillance policy reform must coordinate both domestic and foreign imperatives. At home, it must be oriented toward solving a racial equity issue which produces daily harm. Abroad, it must be motivated by preserving 21st century democracy and human rights.

Digitizing State Courts

To overcome the unprecedented backlog of court cases created by the pandemic, courts must be reimagined. Rather than strictly brick-and-mortar operations, court must consider themselves digital platforms. To accomplish this, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) – with support from 18F, U.S. Digital Service, the Legal Services Corporation, and the State Justice Institute – must build and fund professional and technical capacity at the state level to develop and adopt standardized digital infrastructure for courts and other justice agencies. Due to the replicable nature of this solution across states, the federal government is perfectly positioned to lead this effort, which will be more cost effective than if each court system attempted this work on their own. The estimated cost is $1 billion.

This once-in-a-generation investment will allow courts to collect granular, raw data, which can help overcome the current backlog, increase access to the justice system, inform policies that drive down mass incarceration, improve transparency, and seed a public and private revolution in justice technology that improves access to justice for all Americans.

Challenge and Opportunity

The COVID-19 pandemic brought physical shutdowns to American courts and an unprecedented backlog of cases. In Connecticut, pending civil and criminal cases jumped 200 percent, and many trials are not scheduled to start until 2021. As of June, New York City had 39,200 criminal cases in backlog. Meanwhile, San Diego, California has 20,000 criminal cases waiting to be heard. These are just a small sample of a widespread national trend.

In an attempt to manage this moment, courts rapidly moved online and opened Slack channels and Zoom accounts. Quick action like this should be applauded. However, these solutions are undercut by the justice system’s long-term lack of investment in digital infrastructure.

Across the country, courts fail at data collection, publication, and use. States like California, Colorado, and Florida passed laws in recent years to collect more data created by the justice system, but they are in the minority. Many states still operate on paper and have little-to-no digital data. In Massachusetts, a state that spent over $75 million to digitize court infrastructure, courts still don’t electronically track judges’ decisions, bail rates, or even a party’s gender. Nationally, a 2015 study found that 26 state court systems could not provide “an accurate report on how many cases were filed and disposed in any given year” — the most basic of court data. Meanwhile, public trust in the courts recently fell by double digits and the U.S. ranks 36th globally on access to civil justice— behind Rwanda and on par with Kazakhstan.

This lack of reusable data puts a ceiling on our understanding of individual courts and what courts can do with technology. Without data, software solutions like those that help analyze a court’s caseload, automate court processes, or provide assistance to people representing themselves without an attorney, are out of reach. While the relationship between data and improved court understanding and efficiency has been well-known for at least 30 years, the existing failures of the justice system compounded by the pandemic demand sweeping action.

Plan of Action

To fix this systemic problem at its foundation, the DOJ should support state courts in the adoption of open data standards, modern data collection methods, and application programming interfaces (APIs). Collectively, this is the digital infrastructure needed to help courts manage the tens of thousands of cases that have piled up, become more efficient, and increase access to justice.

This approach is different from how justice system actors currently conceptualize managing information. Currently, agencies generally think about data only in its finished form: a court order, a pamphlet, or a website. Thinking as a digital platform requires justice system leaders to consider data not only in its end form, but as raw data that is accurate, publicly available, secure, and reusable.

To make this a reality, the reconstituted Office of Access to Justice in the DOJ, with support from 18F, U.S. Digital Service, the Legal Services Corp., and the State Justice Institute, needs to offer grant and technical support so local court systems can digitize court data and services. To do this, three layers must be created: information, platform, and presentation. This proposal supports the creation of the first two layers, setting the foundation for the development of the third.

The information layer encompasses all of a justice system’s structured and unstructured data, including case filing and case outcome data. Creating this layer means collecting and cleaning the standardized data that exists across court systems, but also turning unstructured data – like court rules and orders that are usually housed in PDFs or on paper – into structured data. Creating this layer is time-consuming and painstaking, but the process is replicable across jurisdictions, which is why funding and technical support from the federal government is important and more cost effective than relying on each state to recreate this process. The National Center for State Courts published open data standards for courts in 2019. By using these standards across the country, court-to-court and state-to-state comparisons become possible, which can better inform local need and complementary federal support.

The platform layer gives the data utility. This includes the adoption of data management processes and software and APIs. This creates a multitude of benefits. Most significantly, it allows courts to quantify and manage the case backlog by giving them ready access to usable information about what types of cases are pending, for how long, and why. Having readily useable data will also increase transparency by allowing administrators, policymakers, and researchers to dig into how courts function.

Publicly available, structured data also lowers the barrier to entry for entrepreneurs and researchers building solutions to mass incarceration and the access-to-justice gap, thus creating the presentation layer. We’ve already seen this in other markets: data from weather.gov informs weather forecasts on our devices and local government transit data populates real-time information on map applications. For courts, this layer may include a court data portal where the public can see, in real time, what’s happening at the court. The presentation layer could come in the form of a text message reminder system that helps people appear for their court date, which would decrease bench warrants and pre-trial detention. This data will also assist the adoption of online dispute resolution software, which allows courts to quickly resolve high-volume, low-stakes cases without requiring in-court hearings, saving time, money, and trouble.

Conclusion

By focusing on data infrastructure, localities will have the information to uncover and tackle the most pressing issues that they face. However, if the justice system continues on its current path, fewer people will have access to the courts, people will continue to languish in prison, and faith in the justice system will continue to erode.

Compliance as Code and Improving the ATO Process

A wide-scale cyber-attack in 2020 impacted a staggering number of federal agencies, including the agency that oversees the United States nuclear weapons arsenal. Government officials are still determining what information the hackers may have accessed, and what they might do with it.

The fundamental failure of federal technology security is the costly expenditure of time and resources on processes that do not make our systems more secure. Our muddled compliance activities allow insecure legacy systems to operate longer, increasing the risk of cyber intrusions and other system meltdowns. The vulnerabilities introduced by these lengthy processes have grave consequences for the nation at large.

In federal technology, the approval to launch a new Information Technology (IT) system is known as an Authority to Operate (ATO). In its current state, the process of obtaining an ATO is resource-intensive, time-consuming, and highly cumbersome. The Administration should kick-start a series of immediate, action-oriented initiatives to incentivize and operationalize the automation of ATO processes (also known as “compliance as code”) and position agencies to modernize technology risk management as a whole.

Challenge and Opportunity

While the compliance methodologies that currently comprise the ATO process contribute to managing security and risk, the process itself causes delays to the release of new systems. This perpetuates risk by extending the use of legacy—but often less secure—systems and mires agencies with outdated, inefficient workflows.

To receive an ATO, government product owners across different agencies are required to demonstrate compliance with similar standards and controls, but the process of providing statements of compliance or “System Security Plans” (SSPs) is redundant and siloed. In addition, SSPs are often hundreds of pages long and oriented toward one-time generation of compliance paperwork over an outdated, three-year life cycle. There are few examples of IT system reciprocity or authorization partnerships between federal agencies, and many are reluctant to share their SSPs with sister organizations that are pushing similar or even identical IT systems through their respective ATO processes. This siloed approach results in duplicative assessments and redundancies that further delay progress.

The next administration should shift from static compliance to agile security risk management that meets the challenges of the ever-changing threat landscape. The following Plan of Action advances that goal through specific directives for the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Office of the Federal CIO (OFCIO), General Services Administration (GSA), Technology Transformation Service (TTS), and other agencies.

Plan of Action

The Office of Federal Chief Information Officer (OFCIO) should serve as the catalyst of several of activities aimed at addressing inefficiencies in the ATO attainment process.

OFCIO should draft an OMB Compliance as Code Memorandum that initiates two major activities.

First, the Memorandum will direct GSA to create a Center of Excellence within the Technology Transformation Service (TTS). The goals and actions of the Center of Excellence are detailed under “Action Two” below. Second, the Memorandum should require Cabinet-level agencies to draft brief “exploration and implementation plans” that describe how the agency or agencies might explore and adopt compliance as code to create efficiencies and reduce burden.1

OFCIO should offer guidance for the types of explorations that agencies might consider. These might include:

- The integration of development, security and operations (DevSecOps)2 in major systems to allow for the automated validation of security controls.

- The identification of a pilot system or application within each agency that can be leveraged for the conversion of SSPs into a machine-readable format that allows for experimentation with compliance automation.

- The appointment of a single, accountable leader within each agency to guide and oversee compliance as code explorations as well as provide regular reporting to agency Chief Information Officers.

During the plan review process, the OFCIO should collaborate with the Resource Management Offices (RMOs) at OMB to identify agencies that offer the most effective plans and innovations.3 Finally, OFCIO should consider releasing a portion of the agency plans publicly with the goal of spurring research and collaboration with industry.

The General Services Administration should create a Cybersecurity Compliance Center of Excellence.

OMB should commission the creation of a Cybersecurity Compliance Center of Excellence at the General Services Administration (GSA). Joining the six other Centers of Excellence, the Cybersecurity Compliance Center of Excellence (CCCE) would serve to accelerate the adoption of compliance as code solutions, analyze current compliance processes and artifacts, and facilitate cross-agency knowledge-sharing of cybersecurity compliance best practices. In addition, OMB should direct GSA to establish a Steering Committee representative of the Federal Government that leverages the expertise of agency Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs), Deputy CISOs, and Chief Data Officers (CDOs) as well as representatives from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

The CCCE Steering Committee will research potential paths to propagate compliance as code that are not overly burdensome to agencies, deliberate on these initiatives, and guide and oversee agency innovations. The ultimate goal for the Steering Committee will be to devise a strategy and series of practices to increase compliance as code adoption via the Cybersecurity Compliance Center of Excellence and OMB oversight.

The following sections detail potential opportunities for CCCE Steering Committee investigation and evaluation:

Study IT System Acquisition Rules for Vendor Compliance Information. The Steering Committee should review existing acquisition guidance and consider drafting a new acquisition rule that would require software vendors to provide ATO-relevant, machine-readable compliance information to customer agencies. The data package could include control implementation statements, attestation data and evidence guidance for the relevant NIST controls.4 In addition, the new system and process improvements should be agile enough to allow the incorporation of controls unique to a particular application or service.

Shifting the responsibility of managing compliance information from agencies to vendors

saves time and taxpayer dollars spent in the duplicative discovery, creation, and maintenance

of control implementation guidance for common software. The rule would be doubly

effective in time saved if the vendor’s compliance data package has common reciprocity

between agencies, allowing for faster adoption of software government wide.5 Finally, the

format of the data package should be open sourced, fungible and accessible.

Examine and Improve the Utility of System Security Plans (SSPs). System Security Plans are the baseline validator of a system’s security compliance and a comprehensive summary of an IT system’s security details.6 OMB and the CCCE Steering Committee should direct agencies to investigate the reusability and transmutability of System Security Plans (SSPs) across the Federal Government. A research-focused task force, composed of federal data scientists, compliance subject matter experts, auditors, and CISOs, should research how SSPs are utilized and draft recommendations on how best to improve their utility. The research task force would collect a percentage of agency SSPs, compare time-to-ATOs for various government organizations, and develop a common taxonomy that will allow for reciprocity between government agencies.

Create a Federal Compliance Library. The Steering Committee should investigate the creation of an inter-agency Federal Compliance Library. The library, most likely hosted by NIST, would support cross-agency compliance efforts by offering vetted pre-sets, templates, and baselines for various IT systems. A Federal Compliance Library accelerates the creation and sharing of compliance documentation and allows for historical knowledge and best practices to have impact beyond one agency. These common resources would free up agency compliance resources to focus on authorization materials that require novel documentation.

Explore Open Security Controls Assessment Language (OSCAL). The Steering Committee should explore the value added by mandating the conversion of agency SSP components to machine readable code such as Open Security Controls Assessment Language (OSCAL).7 OSCAL allows for the automated monitoring of control implementation effectiveness while making documentation updates easier and more efficient.

Conclusion

Federal compliance processes are ripe for innovation. The current system is costly and perpetuates risk while trying to control for it. The Plan of Action detailed above creates a crossagency collaborative environment that will spur localized innovations which can be tested and perfected before scaling government wide.