Air Force Briefing Shows Nuclear Modernizations But Ignores US and UK Programs

Click to view large version. Full briefing is here.

By Hans M. Kristensen

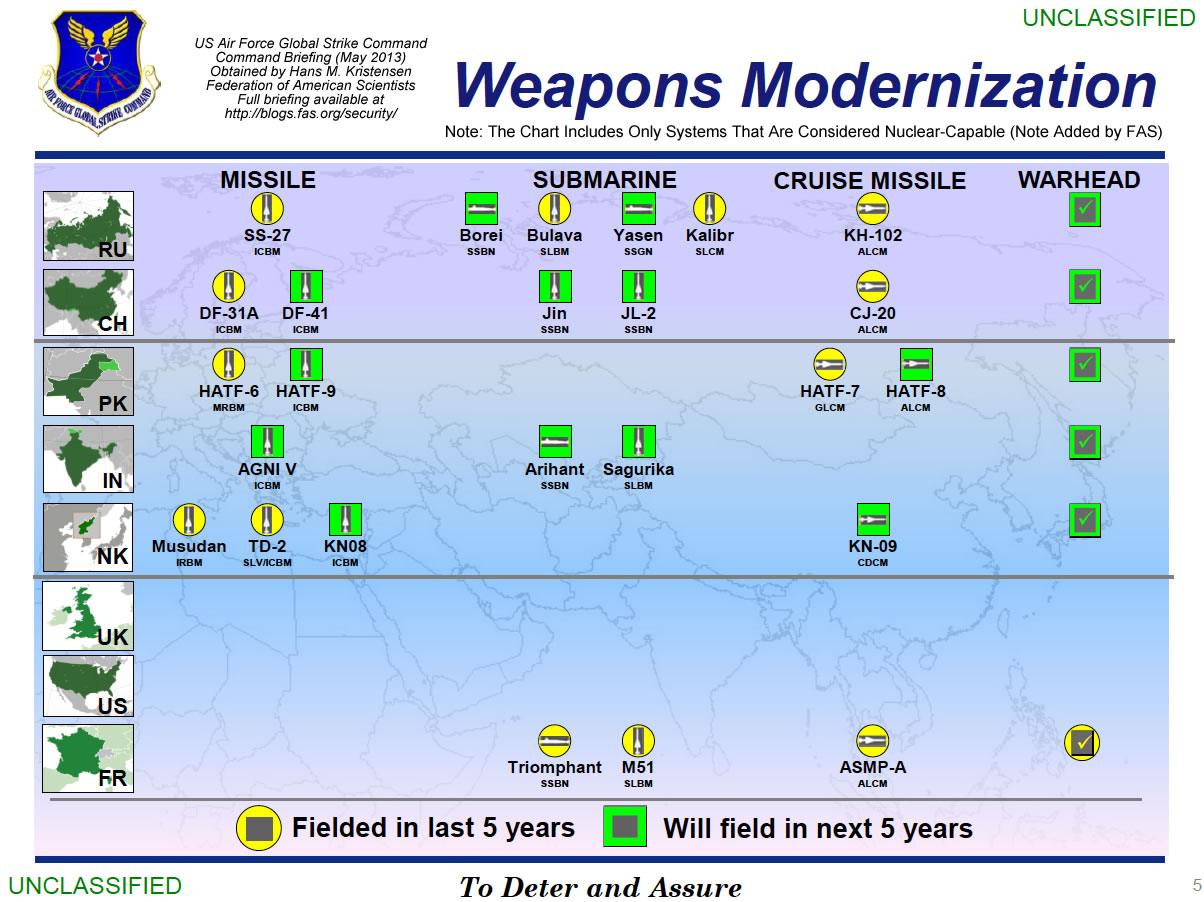

China and North Korea are developing nuclear-capable cruise missiles, according to U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC).

The new Chinese and North Korean systems appear on a slide in a Command Briefing that shows nuclear modernizations in eight of the world’s nine nuclear weapons states (Israel is not shown).

The Chinese missile is the CJ-20 air-launched cruise missile for delivery by the H-6 bomber. The North Korean missile is the KN-09 coastal-defense cruise missile. These weapons would, if for real, be important additions to the nuclear arsenals in Asia.

At the same time, a closer look at the characterization used for nuclear modernizations in the various countries shows generalizations, inconsistencies and mistakes that raise questions about the quality of the intelligence used for the briefing.

Moreover, the omission from the slide of any U.S. and British modernizations is highly misleading and glosses over past, current, and planned modernizations in those countries.

For some, the briefing is a sales pitch to get Congress to fund new U.S. nuclear weapons.

Overall, however, the rampant nuclear modernizations shown on the slide underscore the urgent need for the international community to increase its pressure on the nuclear weapon states to curtail their nuclear programs. And it calls upon the Obama administration to reenergize its efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons.

Russia

![]()

The briefing lists seven Russian nuclear modernizations, all of which are well known and have been underway for many years. Fielded systems include SS-27 ICBM, Bulava SLBM, Kalibr SLCM, and KH-102 ALCM.

It is puzzling, however, that the briefing lists Bulava SLBM and Kalibr SLCM as fielded when their platforms (Borei SSBN and Yasen SSGN, respectively) are not. The first Borei SSBN officially entered service in January 2013.

Nuclear Cruise Missile For Yasen SSGN

It is the first time I’ve seen a U.S. government publication stating that the non-strategic Kalibr land-attack SLCM is nuclear (in public the Kalibr is sometimes called Caliber). The first Yasen SSGN, the Severodvinsk, test launched the Kalibr in November 2012. The weapon will also be deployed on the Akula-class SSGN. The Kalibr SLCM, which is dual-capable, will probably replace the aging SS-N-21, which is not. There are no other Russian non-strategic nuclear systems listed in the AFGSC briefing.

A new warhead is expected within the next five years, but since no new missile is listed the warhead must be for one of the existing weapons.

China

![]()

The briefing lists six Chinese nuclear modernizations: DF-31A ICBM, DF-41 ICBM, Jin SSBN, JL-2 SLBM, CJ-20 ALCM, and a new warhead.

The biggest surprise is the CJ-20 ALCM, which is the first time I have ever seen an official U.S. publication crediting a Chinese air-launched cruise missile with nuclear capability. The latest annual DOD report on Chinese military modernization does not do so.

H-6 with CJ-20. Credit: Chinese Internet.

The CJ-20 is thought to be an air-launched version of the 1,500+ kilometer ground-launched CJ-10 (DH-10), which the Air Force in 2009 reported as “conventional or nuclear” (the AFGSC briefing does not list the CJ-10). The CJ-20 apparently is being developed for delivery by a modified version of the H-6 medium-range bomber (H-6K and/or H-6M) with increased range. DOD asserts that the H-6 using the CJ-20 ALCM in a land-attack mission would be able to target facilities all over Asia and Russia (east of the Urals) as well as Guam – that is, if it can slip through air defenses.

The elusive DF-41 ICBM is mentioned by name as expected within the next five years. References to a missile known as DF-41 has been seen on and off for the past two decades, but disappeared when the DF-31A appeared instead. The latest DOD report does not mention the DF-41 but states that, “China may also be developing a new road-mobile ICBM, possibly capable of carrying a multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV).” (Emphasis added).

AFGSC also predicts that China will field a new nuclear warhead within the next five years. MIRV would probably require a new and smaller warhead but it could potentially also refer to the payload for the JL-2.

Pakistan

![]()

Pakistan is listed with five nuclear modernizations, all of which are well known: Hatf-8 (Shaheen II) MRBM, Hatf-9 (NASR) SRBM, Hatf-7 (Babur) GLCM, Hatf-8 (Ra’ad) ALCM, and a new warhead. Two of them (Hatf-8 and Hatf-7) are listed as fielded.

The briefing mistakenly identifies the Hatf-9 as an ICBM instead of what it actually is: a short-range (60 km) ballistic missile.

The new warhead might be for the Hatf-9.

India

![]()

India is listed with four nuclear modernizations, all of which are well known: Agni V ICBM, Arihant SSBN, “Sagurika” SLBM, and a new warhead. The U.S. Intelligence Community normally refers to “Sagurika” as Sagarika, which is known as K-15 in India.

Neither the Agni III nor Agni IV are listed in the briefing, which might indicate, if correct, that the two systems, both of which were test launched in 2012, are in fact technology development programs intended to develop the technology to field the Agni V.

The U.S. Intelligence Community asserts that the Agni V will be capable of carrying multiple warheads, as recently stated by an India defense industry official – a dangerous development that could well motivate China to deploy multiple warheads on some of its missiles and trigger a new round of nuclear competition between India and China.

The new warhead might be for the SLBM and/or for Agni V.

North Korea

![]()

North Korea is listed with five nuclear modernizations: Musudan IRBM, TD-2 SLV/ICBM, KN-08 ICBM, KN-09 CDCM, and a warhead.

The biggest surprise is that AFGSC asserts that the KN-09 is nuclear-capable. There are few public reports about this weapon, but the South Korean television station MBC reported in April that it has a range of 100-120 km. MBC showed KN-09 as a ballistic missile, but AFGSC lists it as a CDCM (Coastal Defense Cruise Missile).

The Musudan IRBM is listed as “fielded” even though the missile, according to the U.S. Intelligence Community, has never been flight tested. In this case, “fielded” apparently means it has appeared but not that it is operational or necessarily deployed with the armed forces.

The Mushudan is listed as “fielded,” similar to the Russian SS-27, even though the North Korean missile has never been flight tested.

The KN-08 ICBM, which was displayed at the May 2012 parade, was widely seen by non-governmental analysts to be a mockup. But AFGSC obviously believes the weapon is real and expected to be “fielded” within the next five years. There were rumors in January 2013 that North Korea had started moving KN-08 launchers around the country at the beginning of a saber-rattling campaign that lasted through March.

Finally, the AFGSC briefing also predicts that North Korea will field a nuclear warhead within the next five year. Whether this refers to North Korea’s first weaponized warhead or newer types is unclear.

United Kingdom

![]()

The UK section does not include any weapons modernizations, which doesn’t quite capture what’s going on. For example, Britain is deploying the modified W76-1/Mk4A, which British officials have stated will increase the targeting capability of the Trident II D5 SLBM. Accordingly, a warhead icon has been added to the U.K. bar above.

Moreover, although the final approval has not been given yet, Britain is planning construction of a new SSBN to replace the current fleet of four Vanguard-class SSBNs. The missile section is under development in the United States. The new submarine will also receive the life-extended D5 SLBM.

United States

![]()

The U.S. section also does not show any nuclear modernizations, which glosses over important upgrades.

For example, the Minuteman III ICBM is in the final phases of a decade-long multi-billion dollar life-extension program that will extend the weapon to 2030. Privately, Air Force officials are joking that everything except the shell is new. Accordingly, a fielded ICBM icon has been added to the U.S. bar.

Moreover, full-scale production and deployment of the W76-1/Mk4A warhead on the Trident II D5 SLBM is underway. The combination of the new reentry body with the D5 increases the targeting capability of the weapon. Accordingly, a fielded warhead icon has been added to the U.S. bar.

In addition, from 2017 the U.S. Navy will begin deploying a modified life-extended version of the D5 SLBM (D5LE) on Ohio-class SSBNs. Production of the D5LE is currently underway, which will be “more accurate” and “provide flexibility to support new missions,” according to the navy and contractor. Accordingly, a forthcoming SLBM icon has been added to the U.S. bar.

Finally, the United States has begun design of a new SSBN class, a long-range bomber, a long-range cruise missile, a fighter-bomber, a guided standoff gravity bomb, and is studying a replacement-ICBM.

Hardly the dormant nuclear enterprise portrayed in the briefing.

France

![]()

France is listed with four nuclear modernizations, all well known: Triomphant SSBN, M51 SLBM, ASMP-A ALCM, and a new warhead.

The introduction of the ASMP-A is complete but the M51 SLBM is still replacing M45 SLBMs on the SSBN fleet.

The warhead section only appears to include the TNA warhead for the ASMP-A but ignores that France from 2015 will begin replacing the TN75 warhead on the M51 SLBM with the new TNO.

What is Meant by Nuclear and Fielded?

The AFGSC briefing is unclear and somewhat confusing about what constitutes a nuclear-capable weapon system and when it is considered “fielded.”

AFGSC confirmed to me that the slide only lists nuclear-capable weapon systems.

Air Force regulations are pretty specific about what constitutes a nuclear-capable unit. According to Air Force Instruction 13-503 regarding the Nuclear-Capable Unit Certification, Decertification and Restriction Program, a nuclear-capable unit is “a unit or an activity assigned responsibilities for employing, assembling, maintaining, transporting or storing war reserve (WR) nuclear weapons, their associated components and ancillary equipment.”

This is pretty straightforward when it comes to Russian weapons but much more dubious when describing North Korean systems. Russia is known to have developed miniaturized warheads and repeatedly test-flown them on missiles that are operationally deployed with the armed forces.

North Korea is a different matter. It is known to have detonated three nuclear test devices and test-launched some missiles, but that’s pretty much the extent of it. Despite its efforts and some worrisome progress, there is no public evidence that it has yet turned the nuclear devices into miniaturized warheads that are capable of being employed successfully by its ballistic or cruise missiles. Nor is there any public evidence that nuclear-armed missiles are operationally deployed with the armed forces.

Moreover, the U.S. Intelligence Community has recently issued strong statements that cast doubt on whether North Korea has yet mastered the technology to equip missile with nuclear warheads. James Clapper, the director of National Intelligence, testified before the Senate on April 18, 2013, that despite its efforts, “North Korea has not, however, fully developed, tested, or demonstrated the full range of capabilities necessary for a nuclear-armed missile.”

So how can the AFGSC briefing label North Korean ballistic missiles as nuclear-capable – and also conclude that the KN-09 cruise missile is nuclear-capable?

There are similar questions about the determination of when a weapon system is “fielded.” Does it mean it is fielded with the armed forces or simply that it has been seen? For example, how can a North Korean Musudan IRBM be considered fielded similarly to a Russia SS-27 ICBM?

Or how can the Musudan IRBM be identified as already “fielded” when it has not been flight tested and only displayed on parade, when the KN-08 is identified as not “fielded” even though it has also not been flight tested, also been displayed on parade, and even moved around North Korea?

Finally, how can the Russian Bulava SLBM and Kalibr SLCM be listed as “fielded” when their delivery platforms (Borei SSBN and Yasen SSGN, respectively) are listed as not fielded?

These inconsistencies cast doubt on the quality of the AFGSC briefing and whether it represents the conclusion of a coordinated Intelligence Community assessment, or simply is an effort to raise money in Congress for modernizing U.S. bombers and ICBMs.

Implications and Recommendations

There are still more than 17,000 nuclear weapons in the world and all the nuclear weapon states are busy maintaining and modernizing their arsenals. After Russia and the United States have insisted for decades that nuclear cruise missiles are essential for their security, the AFGSC briefing claims that China and North Korea are now trying to follow their lead.

For some, the AFGSC briefing will be (and probably already is) used to argue that nuclear threats against the United States and its allies are increasing and that Congress therefore should oppose further reductions of U.S. nuclear forces and instead approve modernizations of the remaining arsenal.

But Russia is not expanding its nuclear forces, the nuclear arsenals of China and Pakistan are much smaller than U.S. forces, and North Korea is in its infancy as a nuclear weapon state.

Instead, the rampant nuclear modernizations shown in the briefing symbolize struggling arms control and non-proliferation regimes that appear inadequate to turn the tide. They are being undercut by recommitments of a small group of nuclear weapon states to retain and improve nuclear forces for the indefinite future. The modernizations are partially being sustained by non-nuclear weapon states – often the very same who otherwise say they want nuclear disarmament – that insist on being protected by nuclear weapons.

The AFGSC briefing shows that there’s an urgent need for the international community to increase its pressure on the nuclear weapon states to curtail their nuclear programs. Especially limitations on MIRVed missiles are urgently needed. For its part, the Obama administration must reenergize its efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons.

There have been many nice speeches about reducing nuclear arsenals but too little progress on limiting the endless cycle of modernizations that sustain them.

Document: Air Force Global Strike Command Command Briefing

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Reflecting on NATO Security in the Context of a Rising China

The future promises to be far more challenging than the past for international security analysts. The security challenges that we will face will be increasingly complex, transnational, and interrelated. This will make their mitigation all the more difficult. But, the reality of this changing security landscape should not cause us to give pause and adopt a Pangloss-like outlook toward our present condition. Insecurity is not a given – security can always be made by those with the will and intellect to do so. In any given context, making security simply requires accurately identifying and prioritizing threats to international security and then developing the requisite mitigations. In this respect, the profession remains largely unchanged from its Cold War origins.

What has changed is the theoretical disposition of international security analysts. Our current generation is far more open to the theorization of security as an essentially contested concept. This has transformed the nature of the international security discourse. It now openly embraces the notion that security is tied to the social construction of security threats. It is therefore valid to intervene in the debate over how China’s rise affects international security from a social constructivist perspective. Doing so requires recognizing that security is subjective and only meaningful in the presence of a referent object. As a consequence, we must start our analysis with the question: “Whose security are we talking about?”

For the purpose of this article, the discussion will be restricted to NATO member states.

From this perspective, China’s rise is but one of many important variables in the post-Cold War international security discourse. In fact, China is not alone in terms of rising power and prestige. Other important countries include the other BRICSI countries – Brazil, Russia, India, South Africa, and Indonesia. Their collective rise is shifting the global balance of power away from the NATO region and forcing major structural changes to global and regional security architectures.

To avert a systemic breakdown, the resident and emerging major powers will need to reach a strategic compromise. This might even require the construction of a new order that better accommodates the rising powers’ interests without sacrificing too much of the incumbents’. But, reaching such a compromise will not be easy.

If the two sides find themselves unable to forge an amicable solution, one or more of the emerging powers could make a revisionist move. In the decades ahead, international security analysts must therefore remain attentive to any signals that the rising power(s) are no longer willing or able to accept the notion that “international peace is more important than any other national objective.” In the end, it is the possible rejection of the status quo by one or more of these emerging powers that most threatens international peace and stability.

But there is far more to the story of international security in the 21st Century than just the rise of these emerging powers. The world is also witnessing other major changes across multiple levels and units of analysis in the international security domain. Chief among these are the Nanotechnology, Biotechnology, Robotics and Information and Communication technologies (NBRIC) revolution, the rise of non-state security actors, the emergence of high-end non-traditional security (NTS) threats (such as climate change and emerging infectious disease), the advent of new high-end countermeasures (like ballistic missile defense), the increasingly irrelevance of the chemical and biological weapons non-proliferation regimes, the ongoing threat posed by North Korea, and the appearance of high-end, non-lethal, destructive weapon capabilities (cyber and EMP). Any of these could potentially destabilize the current status quo.

From the perspective of China, these changes present both opportunities and challenges. For example, the rise of non-state security actors presents a threat to the traditional state monopoly on violence. This certainly does not benefit an authoritarian government that can now be brought under surveillance (or even strategically challenged) by non-state actors. However, it also provides China with new export buyers for emerging technologies (such as cyber, precision manufacturing tools, drones, etc.) that could promote domestic economic growth while at the same time empowering others to undertake activities abroad that serendipitously benefit Chinese interests. For these reasons, NATO member states will be watching to see how China responds.

However, China is only part of the story. NATO member states must contend with the larger set of resident and emerging security challenges that threaten the status quo. This has led NATO member states (and many others) to securitize against a widening range of possible security threats to ostensibly protect their security. At times, this has included even partnering with China. But, the consequences of these moves are not all positive. Whereas individual securitizations may increase the security of one referent object (states), they can at the same time increase the insecurity of others (individuals). This state-human security dilemma is itself a major challenge for NATO.

In fact, according to a recent report, global democracy is now at a standstill. This is largely the result of the international community’s post-September 11th penchant for securitization. In the last decade, the transatlantic community has even witnessed major declines across a number of important democracy measures (such as freedom of the press) in key NATO member states and their allies. Efforts to counter the threat posed by NBRICs and traditional Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRNs) also threaten to undermine commercial innovation. This represents a serious challenge to NATO’s economic security in an age where the return to economic growth is necessary to pull Europe and North America out of the global recession.

These pose serious, although often overlooked, security challenges for NATO. The indirect effects of an increasingly securitized NATO might well lead to growing societal pressures within its member states to change course on certain national security policies. The failure by some governments to acquiesce to these calls for change in the name of security could further empower state and non-state actors to challenge the security policies of NATO member states. Not only would this undermine efforts to confront serious security issues abroad, but it could also lead to new security threats on the domestic front (like Anonymous).

Finding the right balance between security and civil liberties will be key for NATO. But, there is no certainty that its member states will be able to do so. If they cannot, NATO could be forced to contend with a growing domestic backlash against its securitizing moves. In that event, it would be even more difficult for NATO member states to counter a rising China. But, whether China could capitalize on such an opportunity is itself a matter of debate. To do so, China will need to overcome its own internal security challenges, which include declining economic growth, widespread environmental degradation, an aging population, and rising ethnic tensions – just to name a few.

So, what is the best path forward for NATO? The answer to this question hinges on the opening question to this article: “Whose security are we talking about?” This is a question that NATO needs to keep at the forefront as its member states respond to an increasingly complex international security landscape.

Michael Edward Walsh is the Director of the Emerging Technologies and High-End Threats Project at the Federation of American Scientists. He is also the President of the Pacific Islands Society, a Senior Fellow at the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Studies of Georgetown University, and a non-resident WSD-Handa Fellow at Pacific Forum CSIS.

Chinese Nuclear Developments Described (and Omitted) by DOD Report

By Hans M. Kristensen

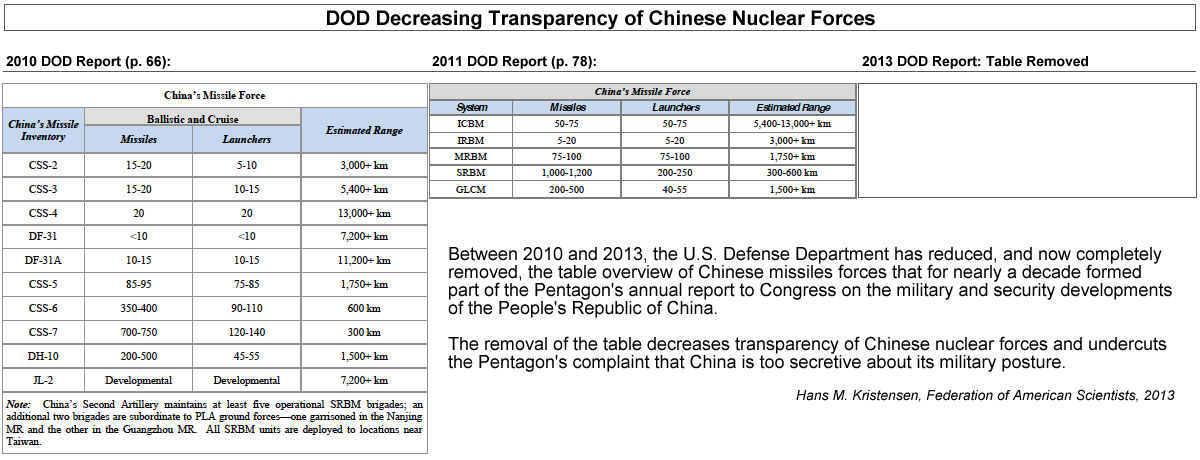

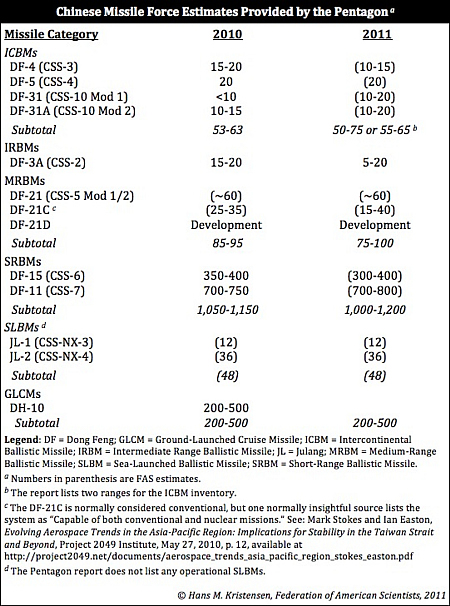

Going, going, gone! In its latest annual report to Congress on the military and security developments of the People’s Republic of China, the Pentagon has removed the last public authoritative overview of Chinese nuclear forces.

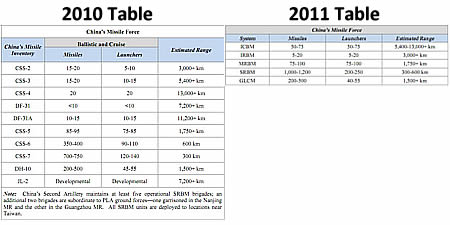

Until 2010, the annual reports included a table with a detailed breakdown of the different types of ballistic missiles that enabled the public to monitor the development of China’s nuclear modernization. In 2011, however, things began to change when a less detailed table was included that only showed overall categories of missiles. That version appeared in 2012 as well, but the 2013 report includes no table at all of China’s missile forces.

The tidbits of information left in the report indicate an ICBM force that is modernizing but leveling out and an SSBN force that is approaching functional capability.

Land-Based Nuclear Forces

DOD reports the same number of ICBMs as last year, 50-75. The Pentagon considers a missile with a range of at least 5,500 km to be an ICBM, so this number includes the DF-5A, DF-31A, DF-31 and DF-4. Of these, only the DF-5A and DF-31A can reach the continental United States.

The 50-75 ICBMs is the same number DOD has reported for the past three years, which indicates that the ICBM force level has leveled out for now. But DOD predicts that additional DF-31As will be deployed over the next two-three years.

The report also repeats the prediction from previous years that China “may also be developing” a new road-mobile ICBM that is “possible capable of” carrying MIRVed warheads. The U.S. Intelligence Community has for several decades assessed that China has a capability to develop and deploy MIRV but that it has not yet done so. One sentence in the report comes close to saying that that’s about to change with “The new generation of mobile missiles, with warheads consisting of MIRVs and penetration aids,” but the report does not confirm widespread rumors (see here and here) that a 10-warhead DF-41 ICBM was test launched last year. All appeared to feed off this article. Many MIRV reports appear to confuse warheads with decoys and penetration aids.

The report does not provide an update of nuclear medium-range missiles, except confirming that a few aging liquid-fuel DF-3As are still operational. They will likely be retired within the next few years.

As one would imagine, the new and increasingly mobile missile force requires updating the command and control system. The DOD report states that China has done so and states that “improved communications links” means that “the ICBM units now have better access to battlefield information, uninterrupted communications connecting all command echelons, and the unit commanders are able to issue orders to multiple subordinates at once, instead of serially via voice commands.”

At the same time, further increases in the number of mobile ICBMs, the DOD report states, “will force the PLA to implement more sophisticated command and control systems and processes that safeguard the integrity of nuclear release authority for a larger, more dispersed force.”

Sea-Based Nuclear Forces

The DOD report states that China has added a third Jin-class (Type 094) SSBN to its fleet and that two more are in various stages of construction. Their nuclear ballistic missile, the Julang-2, is not yet operational, however, but the report indicates that has missile program has overcome technical difficulties, completed a series of successful testing in 2012, and appears ready to reach initial operational capability in 2013.

There is no confirmation of the rumor that the JL-2 has a capability to carry multiple warheads.

The single Xia-class (Type 92) SSBN that China built back in the early 1980s has never been fully operational. It is still afloat, moored at the Jianggezhuang naval base near Qingdao in the Shandong province. The boat will likely be retired, along with its Julang-1 SLBMs, once the Jin-class SSBNs become fully operational.

Moreover, the report predicts that China within the next decade might begin construction of a new class of SSBNs, known as the Type 096. If so, that suggests that the Jin-class design may not have been considered a success.

A Jin-class (top) ballistic missile submarine and Shang-class attack submarine are seen docked at the naval base near Longpo on Hainan Island in this DigitalGlobe/GoogleEarth satellite image from June 27, 2012. Jin-class SSBN were first seen at Hainan in February 2008.

Once fully operational, the DOD report states, SSBNs based at Hainan Island “would then be able to conduct nuclear deterrence patrols.” But now China will operate the SSBN fleet remains to be seen. It might begin to mimic deterrence patrols of other nuclear weapon states, but it seems unlikely that China will begin to deploy nuclear-armed missiles on its SSBNs under normal circumstance because the Central Military Commission is unlikely to hand over nuclear warheads to the armed forces unless in an emergency.

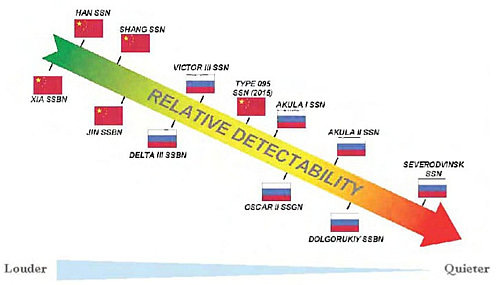

Moreover, Chinese SSBNs are relatively noisy (see graph below) and vulnerable to enemy anti-submarine capabilities, so it seems contrary to China’s core strategic objective of protecting its retaliatory nuclear capability to send some of it out to sea where it can be sunk by enemy attack submarines.

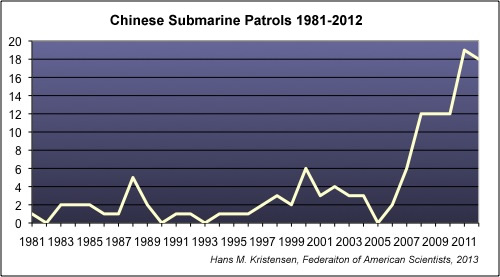

This vulnerability is compounded by the fact that Chinese SSBNs have never conducted a deterrence patrol (see below), which makes the Chinese navy woefully inexperienced in operating an SSBN effectively and safely.

Data obtained from U.S. Naval Intelligence under the Freedom of Information Act shows that Chinese missile submarines have never conducted a deterrent patrol. The attack submarine fleet is more active, with patrols having more than quadrupled over the past decade from around four per year to approximately eighteen patrols last year (see graph).

The increase in general-purpose submarine patrols has coincided with the introduction of the Chang-class (Type 093) nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN) from 2005, but probably also reflects operations by more advanced diesel-electric submarines. The introduction of Type 093 SSNs has been slow, however, with only two in service and four improved version under construction to replace the remaining aging first-generation Han-class (Type 091) class SSNs.

Within the next decade, the DOD report predicts, China will likely begin construction of a new class of nuclear-powered attack submarines (Type 096), which might be equipped with land-attack cruise missiles.

Air-Based Nuclear Forces

The DOD report does not explicitly credit the Chinese air force with a nuclear capability but it probably has a limited secondary mission with nuclear gravity bombs. The H-6 medium-range bomber was used to carry out a dozen nuclear tests in the 1970s and 1980s.

The report states that China is modifying the H-6 to “a new variant that possesses greater range and will be armed with a long-range cruise missile.” Elsewhere the report states that H-6 upgrades “may provide the capability to carry new, longer-range cruise missiles.” So whether the H-6 upgrades involve one or more types of long-range cruise missiles is a little unclear.

So far the air-launched cruise missiles have not been credited with nuclear capability, although the ground-launched DH-10 (which is not mentioned in the DOD report) was described as “conventional or nuclear” by the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center in 2009.

Conclusions and Implications

Chinese nuclear modernizations continue with modest pace with focus on safeguarding a retaliatory capability by replacing land-based liquid-fuel missiles with solid-fuel versions, increasing mobile ICBMs, and building a small fleet of ballistic missile submarines.

The size of the ICBM force appears to be leveling out for now, although more may be deployed in the future. And once the 36 JL-2 SLBMs on the three Jin-class SSBNs become operational, they will increase the Chinese nuclear ballistic missile force by approximately 27 percent compared with the current inventory.

Yet because older types are also being retired, the impact on the size of the total nuclear weapons stockpile so far appears to be modest. Earlier this year, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Global Affairs, Madelyn Creedon, testified before the Senate that despite China’s nuclear force modernizations, “we estimate that it has not substantially increased its nuclear warhead stockpile in the past year…” Moreover, STRATCOM Commander General Kehler last year rejected claims by some that China has hundreds or thousands more nuclear weapons than the “several hundred” estimated by the U.S. Intelligence Community.

The complete deletion of the table overview of China’s missile forces is striking because the Pentagon for years has been complaining about a lack of transparency in China’s military modernization. Ironically, this complaint was repeated when the Pentagon briefed this year’s report. Said Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for East Asia, David Helvey:

“So what – what concerns me – is the extent to which China’s military modernization occurs in – in the absence of the type of openness and transparency that others are certainly asking of China and the potential implications and consequences of that lack of transparency on the security calculations of others in the region. And so it’s that uncertainty, I think, that’s of greater concern.”

Instead of assisting Chinese nuclear secrecy, the United States should push for transparency and accountability. Authoritative overviews of Chinese nuclear force developments are important to enable the public to assess implications of China’s nuclear modernization and to counter attempts by those who use the uncertainty created by lack of information to hype the threat in order to justify excessive military spending.

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

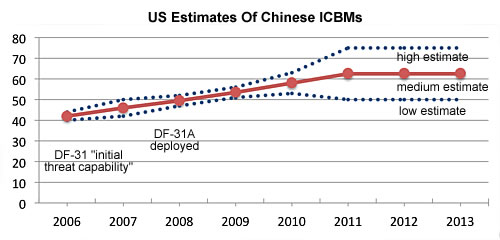

Chinese ICBM Force Leveling Out?

By Hans M. Kristensen

The size of China’s intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) force appears to be leveling out instead of increasing.

During Thursday’s Senate Armed Services Committee hearing on Current and Future Worldwide Threats, Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) director Lieutenant General Michael T. Flynn told the lawmakers:

China’s nuclear arsenal currently consists of approximately 50-75 ICBMs, including the silo-based CSS-4 (DF-5); the solid-fueled, road-mobile CSS-10 Mod 1 and 2 (DF-31 and DF-31A); and the more limited CSS-3 (DF-3) [sic*].

The force level of 50-75 ICBMs is the same as the U.S. Defense Department reported in 2012 and 2011, slightly up from a medium estimate of 55-65 ICBMs reported in 2010 and rising since the DF-31 and DF-31A first started deploying in 2006-2008. But instead of continuing to increase, the force level estimate has been steady for the past three years at a medium estimate of about 63 ICBMs.

Of the 50-75 ICBMs reported for the past three years, “less than 50” can reach the continental United States, according to DIA. Twenty of those are the silo-based DF-5A. That means that China has deployed fewer than 30 DF-31As, six years after it first started fielding the new missile. DOD stopped providing detailed breakdowns of the Chinese missile force in 2011, but the actual DF-31A number might only be around 20 (2-3 brigades) because the total ICBM estimate also includes DF-4 and DF-31, neither of which can reach the continental United States from their deployment areas in China.

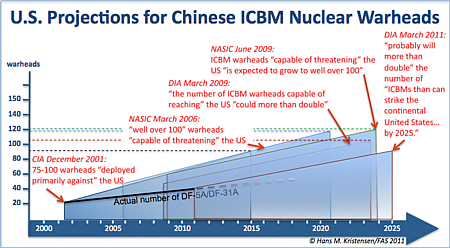

This year’s DIA assessment does not include the prediction from previous years that the number of Chinese ICBMs that can strike the continental United States “probably will more than double…by 2025” to around 100 missiles. This estimate has continued to slide. In 2001 CIA predicted deployment of 75-100 ICBMs “deployed primarily against the United States” by 2015, a prediction that seems in doubt if the the current trend continues.

This year’s DIA threat assessment is also interesting because it doesn’t mention the fabled DF-41, a possible MIRVed ICBM that was rumored to have been test-launched in August 2012. Nor are any of the other new potential launchers identified.

Finally, introduction of China’s new Jin-class SSBN continues to slide; DIA projects the ballistic missile submarine “may reach initial operational capability around 2014,” or four-seven years later than the intelligence community predicted in 2006. Apparently, there have been problems with the Julang-2 missile.

* Note: The designation “DF-3” for the CSS-3 is a typo. It should have been DF-4, for the ageing 5,400-km liquid-fueled ICBM. The DF-3 is an intermediate-range, liquid-fueled ballistic missile that is being retired. Neither the DF-3 nor the DF-21, a more modern medium-range ballistic missile, is mentioned in the testimony.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

STRATCOM Commander Rejects High Estimates for Chinese Nuclear Arsenal

|

| STRATCOM Commander estimates that China has “several hundred” nuclear warheads. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The commander of U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) has rejected claims that China’s nuclear arsenal is much larger than commonly believed.

“I do not believe that China has hundreds or thousands more nuclear weapons than what the intelligence community has been saying, […] that the Chinese arsenal is in the range of several hundred” nuclear warheads.

General Kehler’s statement was made in an interview with a group of journalists during the Deterrence Symposium held in Omaha in early August (the transcript is not yet public, but was made available to me).

General Kehler’s statement comes at an important time because much higher estimates recently have created a lot of news media attention and are threatening to become “facts” on the Internet. A Georgetown University briefing last year hypothesized that the Chinese arsenal might include “as many as 3,000 nuclear warheads,” and General Victor Yesin, a former commander of Russia’s Strategic Rocket Forces, recently published an article on the Russian web site vpk-news in which he estimates that the Chinese nuclear weapons arsenal includes 1,600-1,800 nuclear warheads.

In contrast, Robert S. Norris and I have published estimates of the Chinese nuclear weapons inventory for years, and we currently set the arsenal at approximately 240 warheads. That estimate – based in part on statements from the U.S. intelligence community, fissile material production estimates, and our assessment of the composition of the Chinese nuclear arsenal – obviously comes with a lot of uncertainly and assumptions, but we’re pleased to see that it appears to fit with the “several hundred” warheads mentioned by General Kehler.

Like the other nuclear weapon states, China is modernizing its nuclear arsenal, but it is the only one of the five original nuclear powers (P-5) that appears to be increasing the size of its warhead inventory. That increase is modest and appears to be slower than the U.S. intelligence community projected a decade ago. Those who see an interest in exaggerating China’s nuclear developments thrive on secrecy, so it is important that China – and others who know – provide some basic information about trends and developments to avoid exaggerated estimates. The reality is bad enough as it is.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Event: Conference on Using Satellite Imagery to Monitor Nuclear Forces and Proliferators

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Earlier today we convened an exciting conference on use of commercials satellite imagery and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to monitor nuclear forces and proliferators around the world. I was fortunate to have two brilliant users of this technology with me on the panel:

- Tamara Patton, a Graduate Research Assistant at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, who described her pioneering work to use freeware to creating 3D images of uranium enrichment facilities and plutonium production reactors in Pakistan and North Korea. Her briefing is available here.

- Matthew McKinzie, a Senior Scientists with the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Nuclear Program and Lands and Wildlife Program, who has spearheaded non-governmental use of GIS technology since commercial satellite imagery first became widely available. His presentation is available here.

- My presentation focused on using satellite imagery and Freedom of Information Act requests to monitor Chinese and Russian nuclear force developments, an effort that is becoming more important as the United States is decreasing its release of information about those countries. My briefing slides are here.

In all of the work profiled by these presentations, the analysts relied on the unique Google Earth and the generous contribution of high-resolution satellite imagery by DigitalGlobe and GeoEye.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Chinese Mobile ICBMs Seen in Central China

|

| Road-mobile DF-31/31A ICBM launchers deploying to Central China are visible on new commercial satellite images. Click on image for larger version. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Recent satellite images show that China is setting up launch units for its newest road-mobile Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) in central China. Several launchers of the new DF-31/31A appeared at two sites in the eastern part of the Qinghai province in June 2011. This is part of China’s slow modernization of its small (compared with Russia and the United States) nuclear arsenal.

An image taken on June 27, 2011 (see above), shows two DF-31/31A launchers on the launch pads of a small launch unit near Haiyan (36°49’37.12″N, 101° 6’22.97″E). One is positioned in a circular pad with support vehicles surrounding it. The circular pad was added to the facility sometime between 2005 and 2010. The other launcher is on a pad to the north, located next to an x-shaped launch pad and a missile garage. The layout of the Haiyan launch site is similar, yet not identical, to the DF-31 launch unit of the 813 Brigade at Nanyang.

Another image taken on June 6, 2011 (see below), shows six DF-31/31A launchers lined up on the parade ground at the 809 Brigade base in Datong about 50 kilometers (32 miles) to the east (36°56’57.67″N, 101°40’2.63″E). The brigade has been thought to be equipped with the DF-21 medium-range missile, but might be under conversion to the longer range DF-31/31A. It is unclear if the launchers are permanently based in the area or temporarily deployed from the 812 Brigade some 500 kilometers (290 miles) to the southeast.

|

| Six mobile DF-31/31A launchers seen on display at a launch brigade in Datong, Qinghai, in central China in June 2011. Click image for larger version. |

.

With an estimated range of 7,200-plus kilometers (4,470 miles), the DF-31 cannot target the continental United States from Central China. But the modification known as DF-31A can with its estimated range of 11,200-plus kilometers (6,960 miles), reach most of the continental United States from Central China. The DF-31/31A missiles can target all of Russia and India from Central China.

Slow Deployment

Deployment of the DF-31 has been slow since it first entered service in 2006. Less than 10 missiles had been deployed with as many launchers by 2010, and not many more were added in 2011.

The DF-31A began deployment in 2007 with about a dozen missiles on as many launchers by 2010. Also counting 20 silo-based DF-5As, the U.S. intelligence community estimates that China currently has “fewer than 50” missiles that can target the continental United States, suggesting that less that 25 DF-31As are currently deployed. (The number is a little more uncertain now after the Pentagon in 2011 started supporting Chinese nuclear secrecy by no longer providing a breakdown of Chinese missile forces in its annual report on Chinese military power).

As older missiles with shorter range are retired and replaced by the DF-31/31A over the next decade, a greater portion of the Chinese missile force will be able to target the continental United States, perhaps twice as many by 2025. But even then, the Chinese force will be small compared with that of Russia and the United States.

Also visit: IMINT & Analysis and Project 2049

Analysis made possible by generous grants from the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Ploughshares Fund.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

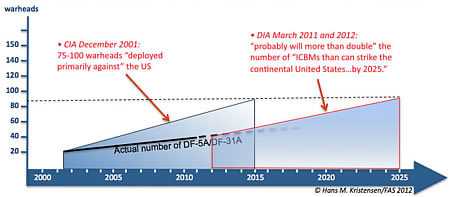

Chinese Nuclear Modernization: Smaller and Later

|

| DIA threat assessment shows slower Chinese nuclear modernization. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

At about the same time nuclear arms reduction opponents last week incorrectly accused the Obama administration of considering “reckless” cuts in nuclear forces that would leave the United States “with fewer warheads than China,” Congress received its annual threat assessment from the U.S. intelligence community.

China’s nuclear arsenal is at a size that makes comparison with U.S. nuclear force level meaningless – even at the lowest level feared by the critics – but the threat assessment showed that China’s nuclear force modernization has been slower than predicted during the Bush administration.

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs)

Back in December 2001, the Central Intelligence Agency predicted that China’s ICBM force “deployed primarily against the United States” would increase to “75 to 100 warheads” by 2015. At the time, China had 20 single-warhead DF-5A ICBMs with a range to strike the continental United States.

Last week’s threat assessment by the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) repeats the assessment from last year that China currently has “fewer than 50 ICBMs that can strike the United States, but that it probably will more than double that number by 2025.” The expected increase refers to the addition of the DF-31A, a single-warhead mobile ICBM that was first deployed in 2007 after more than two decades of development.

But while the 2001 prediction implied deployment of 55-80 DF-31As by 2015, the number by now is less than 30 (tracking the precise number has become a little harder after the United States last year started to assist Chinese secrecy by no longer providing a breakdown of the missile force in the Pentagon’s annual Chinese military power report).

Moreover, the projection for when the portion of the ICBM force that can strike the continental United States will reach close to 100 has slipped by a decade, from 2015 to 2025.

.

Sea-Launched Ballistic Missile Submarines (SSBNs)

Last week’s threat assessment also showed that China’s modernization of its sea-launched ballistic missile force has been slower than projected a few years ago. China is developing the Julang-2 (JL-2) sea-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) for deployment on its new Jin-class SSBNs. Two submarines have been delivered and a couple more may be under construction.

Development of the JL-2, a sea-based version of the land-based DF-31, has been troubled by setbacks. After projecting in 2006 that the JL-2 would reach initial operational capability in 2007-2010, the Pentagon last year said it was uncertain when the missile would become fully operational on the Jin SSBN. And despite unconfirmed Internet-rumors last year about a JL-2 test launch, the DIA told Congress last week that the JL-2 “may reach initial operational capability by 2014.”

So three decades after China launched its first SSBN – the Xia (Type 092), and nearly a decade after launching the first Jin-class (Type 094) SSBN, it still doesn’t have an operational sea-based nuclear force.

| Chinese Jin-Class SSBNs |

|

| After more than two decades in development, China’s new Jin-class SSBNs – see here Xiaopingdao in March 2011 – are still awaiting their loadout of JL-2 missiles. Image: Google |

.

That’s not to say they’re not trying but development of advanced weapons like the JL-2 is difficult (just look a Russia’s problems with its Bulava SLBM), and predictions have been too optimistic.

Once the Jin/JL-2 weapon system becomes operational, the Chinese military will have to figure out how to operate the force; Chinese SSBNs have never conducted a deterrent patrol, they’re noisy, and would need to hide to provide a real secure second-strike capability.

Implications

The point is not that China is not modernizing its nuclear forces (like the other nuclear weapon states, it unfortunately is) or that the intelligence community makes mistakes. The point is to remind that projections like these always tend to promise too much too soon.

Last week’s threat assessment is probably no different but it is interesting because it shows, when compared with previous assessments, that China’s nuclear modernization has been slower than anticipated a decade ago. And there is no indication that China has embarked upon a nuclear build-up intended to “sprint to parity” with the United States or Russia.

That at least ought to be taken into account by those who use China’s nuclear modernization to argue against deeper U.S. (and, by implication, Russian) nuclear reductions.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

No, China Does Not Have 3,000 Nuclear Weapons

|

| A study from Georgetown University incorrectly suggests that China has 3,000 nuclear weapons.The estimate is off by an order of magnitude. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Only the Chinese government knows how many nuclear weapons China has. As in most other nuclear weapon states, the number is a closely held secret. Even so, it is possible to make best estimates of the approximate size that benefit the public debate.

A recent example of how not to make an estimate is the study recently published by the Asia Arms Control Project at Georgetown University. The study (China’s Underground Great Wall: Challenge for Nuclear Arms Control) suggests that China may have as many as 3,000 nuclear weapons.

Although we don’t know exactly how many nuclear weapons China has, we are pretty sure that it doesn’t have 3,000. In fact, the Georgetown University estimate appears to be off by an order of magnitude.

Fissile Material

The most fundamental problem with the 3,000-warhead estimate is that there is no evidence – at least in the public – that China has produced enough fissile material to build that many warheads. Not even close.

An arsenal of 3,000 two-stage thermonuclear warheads with yields of 300-500 kilotons would require 9-12 tons of weapon-grade plutonium and 45-75 tons of highly-enriched uranium (HEU).

Based on what is known about China’s inventory of fissile materials, how many nuclear weapons could it build?

According to the International Panel on Fissile Materials, China has produced an estimated 2 tons of plutonium for weapons. Some has been consumed in nuclear tests, leaving roughly 1.8 tons. The estimate is consistent with what the U.S. government has stated and theoretically enough for 450-600 warheads.

Total production of HEU is thought to have been approximately 20 tons. Some has been spent in nuclear tests and research reactor fuel, leaving a stockpile of some 16 tons. That’s theoretically enough for roughly 640-1,060 warheads.

Another critical material is Tritium, which is used in thermonuclear weapons. China probably only produces enough Tritium at its High-Flux Engineering Test Reactor (HFETR) in Jiajiang to maintain an arsenal of about 300 weapons.

The U.S. intelligence community concluded in 2009 that China likely has produced enough weapon-grade fissile material to meet its needs for the immediate future. In other words, no vast warhead expansion is in sight.

Nuclear Warheads

With this stockpile of fissile material on hand, how many nuclear weapons might China currently have?

First, it is important to keep in mind that nuclear weapon states do not convert all of their fissile material into nuclear weapons but use part of it for weapons and leave the rest as a reserve for future needs. Therefore, one cannot simply translate the amount of fissile material into weapons.

Second, nuclear warheads need nuclear-capable delivery vehicles, missiles and aircraft that can bring the warheads to their intended targets. Delivery vehicles can give a better idea of the size of a nuclear arsenal. Most of China’s ballistic missiles are conventional or dual-capable, but the Georgetown University study includes all missiles in its 3,000-warhead projection, including short-range DF-11 and DF-15 missiles and medium-range DF-21C missiles.

Taking those and other factors into account, our current estimate is that China has approximately 240 nuclear warheads for delivery by nearly 180 missiles and aircraft. Nearly 140 of the operational missiles are land-based. Less than 50 of those can reach the continental United States.

The 240-warhead estimate also includes warheads produced for China’s ballistic missile submarine force (which is not yet operational), weapons for bombers, and some weapons for spares.

Our estimate is consistent with the estimate made by the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency in 2006: “China currently has more than 100 nuclear warheads.”

Modernization

With its ongoing modernization of its nuclear forces, which includes deployment of three new ICBMs, China will be placing a greater portion of its warheads on ICBMs. The portion of those that can strike the continental United States, according to the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, “probably will more than double…by 2025.” That doesn’t mean the total warhead stockpile will “more than double,” only the portion that is on ICBMs. Only time will tell to what extent that happens, but the U.S. projection for Chinese nuclear weapons has been wrong before.

Indeed, the DIA estimated in 1984 that China had 360 warheads, including non-strategic warheads, and projected that the arsenal would grow to 592 warheads in 1989 and 818 warheads in 1994. This projection never materialized.

Analysis of projections made by the U.S. intelligence community during the past decade for the growth in Chinese ICBM warheads shows that they have so far been too much too soon (see figure below). The Central Intelligence Agency’s 2001 projection of 75-100 ICBM warheads deployed primarily against the United States by 2015 will not come true unless China increases its production and deployment of the DF-31A missile or begins to deploy multiple warheads on its ICBMs. China will probably only do so if the U.S. deploys a ballistic missile defense system that can nullify the Chinese deterrent.

|

| U.S. projections for Chinese ICBM warheads have generally been too much too soon. Click image for larger version. |

.

Satellite Imagery Interpretations

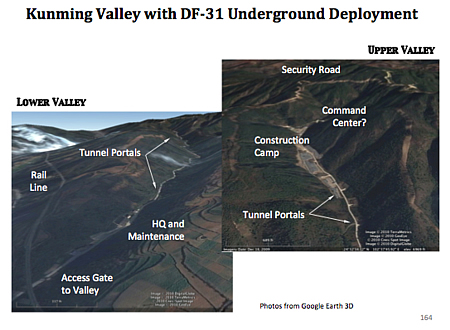

Another issue with the Georgetown University study concerns some of its analysis of commercial satellite imagery. One of the case studies is a series of buildings in a valley south of Kunming in southern China that the study concludes make up an underground deployment site for the DF-31 ICBM (see figure below).

|

| The Georgetown University study suggests that this valley near Kunming in southern China is a DF-31 deployment site. The facility looks more like a munitions depot. It is located at these coordinates: 24.545262°, 102.584378° |

.

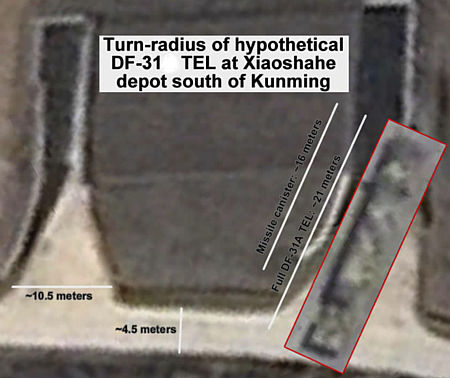

No evidence is presented for this conclusion and the source appears to be a post on the Chinese language web site Sina Military Forum (the link to the story no longer works). “Tunnel portals” in the valley apparently are thought to be for use by DF-31 launchers hiding inside the mountain. Yet the facility does not have any of the characteristics of Chinese DF-31 deployment sites and a minimum of analysis indicates that the portals and roads are too narrow to be used by DF-31 launchers (see figure below). Instead, the buildings in the valley look more like a munitions depot.

|

| This image shows two of the so-called “tunnel portals” identified by the Georgetown University report as being part of a DF-31 deployment site near Kunming. An image of a DF-31/DF-31A launcher is superimposed to illustrate the difficulty it would have turning at the site. The dimensions of the roads indicate that the facility is not for DF-31 launchers, but looks more like a munitions depot.. |

.

Conclusions

The Georgetown University study has collected an impressive amount of scattered information from the Internet about Chinese underground facilities. That is obviously interesting in and of itself, but in terms of assessing Chinese nuclear capabilities, it does the public debate a disservice by disseminating exaggerated and poorly analyzed information.

Readers can obviously read into the report what they want, but a quick Google search for news article headlines about the report shows the damage: “China may have 3000 n-warheads;” “China’s nuclear arsenal ‘many times larger’ than previously thought;” “China ‘hiding up to 3,000 nuclear warheads in secret tunnels.” Many people will not remember the details, but they tend to remember the headlines. A misperception will stick in the public consciousness that China has 3,000 nuclear weapons hidden in tunnels.

But China does not have 3,000 nuclear weapons. It neither has produced the fissile material needed to build that many, not does it have delivery vehicles enough to delivery that many warheads. The Georgetown University study warhead estimate appears to be off by an order of magnitude.

China is in the middle of a significant military modernization and it is important that it is not hyped or exaggerated but analyzed and understood for what is actually happening.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Pentagon’s 2011 China Report: Reducing Nuclear Transparency

|

| The Pentagon’s new report on China’s military forces significantly reduces transparency of China’s missile force by eliminating specific missile numbers previously included in the annual overview. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Pentagon has published its annual assessment of China’s military power (the official title is Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China). I will leave it to others to review the conclusions on China’s general military forces and focus here on the nuclear aspects.

Land-Based Nuclear Missiles

The most noticeable new development compared with last year’s report is that the Pentagon this year has decided to significantly reduce the transparency of China’s land-based nuclear missile force. For the past decade, the Pentagon reports have contained a breakdown of Chinese missiles showing approximately how many they have of each type. Not anymore. This year the details are gone and all we get to see are the overall numbers within each missile range category: ICBMs, IRBM, MRBM, SRBM, and GLCMs.

This is something one would expect the Chinese government to do and not the Pentagon, which has spent the last decade criticizing China for not being transparent enough about its military posture.

What the numbers we’re allowed to see indicate is that China’s missile force has been largely stagnant over the past year. The changes have been in minor adjustments, probably involving:

- Phasing out a few older DF-4s and introducing a few more DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs.

- Reducing the DF-3A force and replacing it with the DF-21 MRBMs (which appears largely unchanged but with greater uncertainty).

- Essentially no increase in number of SRBMs off Taiwan.

- The same number of DH-10 GLCMs.

| Addition: Some news media reports unfortunately misrepresent what the Pentagon report says about Chinese nuclear developments:Washington Times (8/25/11)

Claim: “China expanding its nuclear stockpile” (headline) Fact: The Pentagon report says nothing about China expanding its nuclear stockpile (the word “stockpile” does appear in the report at all) but that it is “qualitatively and quantitatively improving its strategic missile forces.” But it is a “limited nuclear force.” Claim: “Richard Fisher, a China military-affairs analyst, said the report is significant for listing strategic nuclear forces that show an estimated increase of up to 25 new ICBMs, some with multiple warheads, in a year….” Fact: The Pentagon report lists 50-75 and 55-63 ICBMs (both ranges are listed). The medium values are 59-62 ICBMs. The 2010 report listed 53-63 (58) ICBMs. That is an increase of 1-4 ICBMs, not 25, which is the highest end of the estimate. The Pentagon report does not say that China has deployed ICBMs with MIRV, but that it “may be” developing a new mobile ICBM, “possible capable of carrying” MIRV. China has been researching MIRV since the 1980s but so far not chosen to deploy any. The one thing that could drive China to a decision to potentially deploy MIRV in the future would be a U.S. ballistic missile defense system that diminished the effectiveness of China’s nuclear deterrent. Claim: (Fisher) “China will not reveal its missile-buildup plans…so this simply is not the time to be considering further cuts in the U.S. nuclear force, as is the Obama administration’s intention.” Fact: The United States has 5,000 warheads, China 240. Only about 60 of the Chinese warheads can reach the United States, and only half of those can reach all of the United States. Claim: “Advanced China n-missiles on India border, says Pentagon” (headline) Fact: The Pentagon report does not state that China has deployed nuclear missiles on the Indian border. Instead, the report states in general terms that “To strengthen deterrence posture relative to India, the PLA has replaced” DF-3As “with more advanced and survivable” DF-21s. This is a reference to the DF-21 replacing outdated DF-3A brigades at Chuxiong, Jianshui and Kunming in the Yunnan province and near Delingha and Da Qaidam in the Qinghai province. |

.

Trying to reconstruct the table the way it should have been comes with considerable uncertainty, but here is my best estimate (for corrections I will have to rely on individuals in the Pentagon who think that buying into Chinese government secrecy does not advance U.S. or Northeast Asian interests):

|

| Click on table to download larger version. |

.

Ballistic Missile Submarines

The new Jin-class (Type 094) SSBN appears ready but the Pentagon report states that its JL-2 SLBM “has faced a number of problems and will likely continue flight tests.” The Pentagon previously estimated that the Jin/JL-2 system would become operational in 2010 but the new report now states that it is “uncertain” when the new system will become fully operational.

The range of the JL-2 SLBM is extended, somewhat, from 7,200+ km in the 2010 report to 7,400 km in the 2011 report. This does not change the fact that a Jin-class SLBM would have to deploy deep into the Sea of Japan for its JL-2 to be able to strike the Continental United States. Alaska is within range from Chinese waters, but not Hawaii.

The operational status of the old Xia-class (Type 092) SSBN and its JL-1 SLBM “remain questionable.” Neither class has conducted any deterrent patrols yet.

As a result, China does not appear to have any operational sea-launched ballistic missiles at this point.

The report lists only five nuclear attack submarines with the three fleets, down from six last year, suggesting that retirement of the Han-class (Type 091) continues. The Shang-class (Type 093) is operational, and the Pentagon report states that “as many as five third-generation Type 095 SSNs will be added in the coming years.” The U.S. Navy’s intelligence branch estimated in 2009 that the Type 095 will be noisier than the Russian Akula I but quieter than the Victor III.

Chinese attack submarines conducted 12 patrols during all of 2010, the same level as the previous two years.

Underground Facilities

While there has recently been some sensational reporting (see also here) that China since 1995 has built a 5,000-km “great wall” of tunnels under Hebei mountain in the western parts of the Shaanxi province to hide “all of their missiles hundreds of meters underground,” including the DF-5 (CSS-4) ICBM, the reality is probably a little different.

First, as anyone who has spent just a few hours studying satellite images of Chinese military facilities and monitoring the Chinese internet will know, the Chinese military widely uses underground facilities to hide and protect military forces and munitions. Some of these facilities are also used to hide nuclear weapons. The old DF-4, for example, reportedly has existed in a cave-based rollout posture since the 1970s.

The Pentagon report states that China has “developed and utilized UGFs [underground facilities] since deploying its oldest liquid-fueled missile systems and continue today to utilize them to protect and conceal their newest and most modern solid-fueled mobile missiles.” So it is not new but it is also being used for modern missiles.

| Chinese Underground Missile Launcher Facility |

|

| A Chinese mobile missile launcher, possibly for the DF-11 or DF-15 SRBM, emerges from an underground facility at an unknown location. Image: Chinese TV |

.

Second, the particular facility under Hebei mountain appears to be China’s central nuclear weapons storage facility, as recently described by Mark Stokes. The missiles themselves are at the regional bases, although it cannot be ruled out that some may be near Hebei as well. But Stokes estimates that the warheads are concentrated in the central facility with only a small handful of warheads maintained at the six missile bases’ storage regiments for any extended period of time. The missile regiments themselves could also have nearby underground facilities for storing launchers and missiles, although specifics are not known.

One of the Chinese bases with plenty of underground facilities is the large naval base near Yulin on Hainan Island, which I described in 2006 and 2008. The Pentagon report concludes that this base has now been completed and asserts that it is large enough to accommodate a mix of attack and ballistic missile submarines and advanced surface combatants, including aircraft carriers. The report adds that, “submarine tunnel facilities at the base could also enable deployments from this facility with reduced risk of detection.” That would seem to require the submarine exiting from the tunnel submerged; a capability I haven’t seen referenced anywhere yet.

Conclusions

The 2011 Pentagon report shows that China’s nuclear missile force changed little during the past year but appears to continue the slow replacement of old liquid-fueled missiles with new solid-fueled missiles. China’s efforts to develop a sea-launched ballistic missile capability have been delayed.

In an unfortunate change from previous versions of the Pentagon report, the 2011 version significantly reduces the transparency of China’s nuclear missile forces by removing numbers for individual missile types. This change is particularly surprising given the Pentagon’s repeated insistence that China must increase transparency of its military posture. In this case, military secrecy appears to contradict U.S. foreign policy objectives.

The decision to reduce the transparency of China’s missile force is even more troubling because it follows the recent U.S.-Russian decision to significantly curtail the information released to the public under the New START treaty.

The combined effect of these two decisions is that within the past 12 months it has become a great deal harder for the international community to monitor the development of the offensive nuclear missile forces of the United States, Russia and China.

Tell me again whose interest that serves?

See also: 2010 Pentagon Report on China

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Chinese Jin-SSBNs Getting Ready?

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Two of China’s new Jin-class nuclear ballistic missile submarines have sailed to the Xiaopingdao naval base near Dalian, a naval base used to outfit submarines for ballistic missile flight tests.

The arrival raises the obvious question if the Jin-class is finally reaching a point of operational readiness where it can do what it was designed for: launching nuclear long-range ballistic missiles.

The Pentagon reported a year ago that development of the missile – known as the Julang-2 (JL-2) – had run into developmental problems and failed its final test launches.

The Long March to Operational Capability

Even if the Jin subs are in Xiaopingdao to load out for upcoming missile tests and manage to pull it off, the submarines are unlikely to become operational in the sense that U.S. missile submarines are operational when they sail on patrols.

Chinese ballistic missiles submarines have never sailed on a deterrent patrol or deployed with nuclear weapons on board. Chinese nuclear weapons are stored on land in facilities controlled by the Central Military Commission (CMC), and the Chinese military only has a limited capability to communicate with the submarines while at sea.

It is possible, but unknown, that the two submarines are the same two boats that have seen fitting out at the Huludao shipyard for the past several years. One submarine was also seen at Jianggezhuang naval base in August 2010 (see below). Prior to that a Jin-class SSBN was seen seen at Xiaopingdao in March 2009, and at Hainan Island in February 2008. The first Jin-class boat was spotted in July 2007 on a satellite photo from late-2006.

|

| One of the Jin-class SSBNs was seen at Jianggezhuang in August 2010, the first time commercial satellite images have shown a Jin-class submarine at China’s northern fleet submarine base. |

.

And Then What?

Indeed, it is unclear how China intends to utilize the Jin-class submarines once they becomes operational; they are unlikely to be deployed with nuclear weapons on board in peacetime like U.S. missile submarines, so will China use them as surge capability in times of crisis?

Deploying nuclear weapons on Jin-class submarines at sea in a crisis where they would be exposed to U.S. attack submarines seems like a strange strategy given China’s obsession with protecting the survivability of its strategic nuclear forces. The Jin-class SSBN force seems more like a prestige project – something China has to have as a big military power.

Whether it makes sense is another matter.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Chinese Nuclear Forces 2010

|

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

It’s interesting scary what you can find on the Internet: On Thursday, a Canadian calling himself SinoSoldier posted a report on the Pakistani web site Pakistan Defense claiming that China had test launched a JL-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) from a submarine in the Atlantic (!). Different versions allegedly have ranges from 12,000 km to 20,000 km and carry 5-7 warheads as opposed to 10 on the JL-2 SLBM. The source was said to be a report in the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun.

|

| Click image to download |

I haven’t been able to find the original story, but the report in Pakistan Defense is completely wrong: China does not have a JL-3 missile; it does not have a Type 096 submarine; it has never operated a submarine in the Atlantic; its two types of SLBMs (JL-1 and JL-2) have ranges of 1,770 km and 7,200 km, respectively; and they are only equipped with one warhead each.

The flaws in the report unfortunately did not prevent it from being picked up by Undersea Enterprise News Daily, an email newsletter distributed by the U.S. Atlantic submarine fleet headquarters.

Instead, check out our latest Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces, just published for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists by Sage Publications: Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2010 (pdf version)

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.