The DOE’s Proactive FY25 Budget Is Another Workforce Win On the Way to Staffing the Energy Transition

The DOE has spent considerable time in the last few years focused on how to strengthen the Department’s workforce and deliver on its mission – including running the largest basic science research engine in the country, and managing a wide range of decarbonization efforts through clean energy technology innovation, demonstration, and deployment. In general, their efforts have been successful – in no small part because they have been creative and have had access to tools like the Intergovernmental Personnel Act and the Direct Hire Authority that supported the Clean Energy Corps.

It’s no surprise then, that the agency’s FY 2025 budget looks to continue investing in the current and future science and energy workforce. The budget suggests DOE offices are thinking proactively about departmental capacity – in both the federal workforce, and beyond it through workforce development programs that actively grow the pool of future scientists.

Current BIL and IRA Talent

As seen below, several DOE offices across the science, innovation and infrastructure domains have requested increases in program direction funding in FY 2025. Program direction funds are an under-valued but critical resource for enabling the energy transition: DOE must be able to recruit and retain expert staff with a high level of technical proficiency who can meet the multi-faceted demands of public service – reviewing proposals, building bridges with industry, maintaining user facilities, and overseeing execution of complex federal technology programs.

These requests also reflect a larger strategy, motivated by the constraints put on federal management funding by IIJA and IRA. First, while those pieces of legislation poured resources into federal energy innovation, they also limited program direction funds to 3% of account spending, which was highly constraining from a talent perspective – even with the creative use of hiring mechanisms like IPAs and various fellowships. In the final energy spending bill for FY 2024, this was raised to 5% and extended the funds connected to IIJA funding from expiring in 2026 to FY 2029 – a much-needed adjustment to the legislation.

Extensions to and increases in program direction funds are vital for DOE. If the levels of appropriated PD funds don’t match the programs and mandate of offices, it jeopardizes their ability to provide oversight, project management, and effective stewardship of taxpayer dollars. New program direction funding is similarly important for offices like the Grid Deployment Office, a new office formed from a combination of programs from IIJA and IRA and the Office of Electricity. The FY 2025 request includes a $40 million increase above FY 2023, including $30 million for a new microgrid initiative intended to strengthen grid reliability and resilience in high risk regions. The Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains is a more extreme example: because of its recent creation, it needs a sharp increase in program direction funds. In FY24 the office received only $1 million in PD funds, while its FY 2025 PD request is $20 million – a much more appropriate number to support the total office budget request of $113 million. These requests are important and necessary for the long-term ability of DOE to continue to fortify U.S. energy independence and innovation.

Future Workforce

Offices are also focused on building pathways for early career scientists to grow their expertise. The Office of Science (SC), DOE’s central hub for basic science research and National Lab oversight, is a prime example. First, SC’s program direction funding is incredibly low for an office of its size and magnitude, and it has steadily declined over the past several years to less than 3% of the SC appropriations as of FY 2023. The FY 2025 request increase of 8% will help remedy this.

SC has also focused on increasing funding for their workforce development programs, and specifically the Workforce Development for Teachers and Scientists (WDTS) and its Reaching a New Energy Sciences Workforce (RENEW) programs. Both received an increase of $1-2 million – although one of WDTS’s other programs, the Science Undergraduate Laboratory Internship (SULI), was reduced by about $1 million. For most of the WDTS programs, high housing and living costs are cited as a reason for the need for increasing support. These high costs have been cited as a barrier to workforce development at many of the National Labs as well. Congress should explore opportunities to be creative with stipends and program accessibility – to ensure that SC can continue to support workforce development at all levels.

DOE’s FY25 Budget Request Remains Committed to the U.S. Transition to Clean Energy

The Biden Administration has prioritized the clean energy transition as a core element of its governing agenda, via massive legislative victories like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), and through its ongoing whole-of-government focus on clean innovation. The Administration has continued to push for further investments, but faces a difficult fiscal environment in Congress – which has meant shortfalls for many priority areas like funding for CHIPS and Science. In March, the Administration released the FY 2025 budget request for the Department of Energy (DOE), and with it seeks to extend the gains of the past few years. This blog post highlights a selection of priority proposals in the FY 2025 request.

Scaling Clean Energy Technologies

BIL and IRA gave DOE a new mandate to support the demonstration, deployment, and commercialization of clean energy technologies, and established the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) to achieve this. OCED is tasked with managing a range of large-scale commercial demonstration programs, which provide cost-share funding on the order of $50 to $500 million. OCED’s $30 billion portfolio of BIL- and IRA-funded programs include the Industrial Demonstrations Program, which recently announced selections for award negotiations; the Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs; the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Projects; and others.

Now that the majority of its BIL and IRA funding has been awarded, OCED is looking to continue building on this momentum, but annual appropriations have not been easy. OCED last year sought to significantly ramp up its annual appropriations to $215 million, but appropriators ended up providing only $50 million in new funding to OCED – nearly 50% less than FY23. Such an outcome hinders OCED’s ability to launch first-of-a-kind demonstration programs in new areas or expand existing programs, particularly since several OCED programs (like most IIJA and IRA initiatives) are vastly oversubscribed. For instance, OCED’s Industrial Demonstrations program provided awards of $6.3 billion, but received 411 concept papers requesting over $60 billion in federal funding with $100 billion in matching private dollars. Other programs at OCED, including the Energy Improvements in Rural and Remote Areas and the Clean Hydrogen Hubs, were similarly oversubscribed.

For FY 2025, OCED is again proposing a funding ramp-up to $180 million. This includes a new extreme heat demonstration program in collaboration with DOE’s Office of State and Community Energy Programs (SCEP). SCEP has requested $35 million to lead the planning and design phases, while OCED’s request of $70 million will fund the federal cost-share for three to six community-scale demonstration projects. The new program will provide much needed funding for solutions to address extreme heat, which is the top weather-related cause of death for Americans and is only expected to worsen with global temperatures increasing each year.

In addition to OCED’s portfolio, BIL funded a $5 billion Grid Innovation Program (GRIP) managed by the Grid Deployment Office (GDO). GRIP focuses on central grid infrastructure, but GDO also has a portfolio of work on microgrids, which improve resiliency by enabling communities to maintain electricity access even when the larger grid goes down. BIL established some programs that can be used to fund certain components of microgrids or to purchase microgrid capacity, but these programs are unable to fund full scale microgrid demonstration projects. For FY 2025, GDO is requesting $30 million for a new Microgrid Generation and Design Deployment Program that will fill that gap.

Complementary to these large-scale demonstration programs are a suite of small-scale pilot demonstration programs managed by offices under the Under Secretary for Science and Innovation (S4), which provide grants that are typically less than $20 million.

Within the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE), the Geothermal Technologies Office (GTO) has been running a rolling funding opportunity for enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) pilot demonstrations, authorized by BIL and funded by annual appropriations. For FY 2025, GTO is requesting continued funding for this program so that they can support additional greenfield demonstration projects.

EGS is important as a future source of clean, firm energy, but it’s not the only promising next-generation geothermal technology, as closed-loop geothermal has also demonstrated the potential to be cost-competitive with EGS. Currently, only EGS projects are eligible in GTO’s program, despite the fact that BIL and prior legislation intended a more inclusive approach. As such, the Federation of American Scientists has joined with the next-generation geothermal community—including organizations representing both EGS and closed-loop geothermal companies—to call on DOE to take a tech agnostic approach and expand the scope of the program to include all next-generation technologies. We also call on Congress to adopt report language directing DOE to include demonstration projects using closed-loop and other next-generation geothermal technologies, and to appropriate at least GTO’s full budget request of $156 million.

Other proposed demonstration activities across the DOE enterprise include:

- Demonstration programs for reservoir thermal energy storage and thermal energy networks within GTO’s low temperature and coproduced resources portfolio ($24 million);

- Demonstration of wind hybrid systems, which use wind energy to produce hydrogen for energy storage or direct industrial usage, by the Wind Energy Technologies Office ($23.5 million);

- Expansion of in-water demonstrations of grid-scale wave energy devices at the Water Power Technologies Office’s testing facility PacWave ($50 million);

- Validation and demonstration of heat pumps and energy efficiency retrofits in commercial and residential buildings by the Building Technologies Office ($27 million and $32.5 million, respectively);

- Demonstration and validation of a new grid technology by the Office of Electricity ($7 million); and

- Support from the Office of Nuclear Energy to help address the technical, operational, and regulatory challenges facing five potential future demonstration projects, as a part of the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program ($142.5 million).

Tech Transitions and FESI

The Office of Technology Transitions (OTT) was established in 2015 to get the most out of DOE’s RD&D portfolio by better aligning the Department’s science research enterprise with industry and public needs. A core part of OTT’s mission is to expand the commercial impact of DOE’s research investments by developing viable market pathways for technologies coming out of the National Labs. Despite having a relatively small budget, OTT’s mission is crucial for the rapid acceleration of the energy transition.

In FY 2024, however, OTT’s budget was cut by 10% which put a damper on the Office’s ability to carry out its mission. In response, in FY25, OTT is seeking $7.1 million more than its $20 million budget from the previous fiscal year in an attempt to ramp up funding for its programs. This increase also includes a separate funding line item of $3 million for the Foundation of Energy Security and Innovation (FESI), the DOE-affiliated 501(c)3 nonprofit organization established in the CHIPS and Science Act. FESI has significant potential to complement DOE’s mission by being a flexible tool to accelerate clean energy innovation and commercialization. Since the Foundation is a non-federal entity, it can catalyze public-private collaboration and raise private and philanthropic capital to put towards specific projects like funding pilot wells for next-generation geothermal power or filling funding gaps for pilot-scale technologies along the innovation pipeline, for example.

In addition to overseeing the standing up of FESI, OTT facilitates five main programs including the Technology Commercialization Fund, the Energy I-Corps Program, the Lab Partnering Service, the EnergyTech University Prize, and the Technology Commercialization Internship Program. Each of these programs is designed to increase industry and innovator access to the Labs while also bolstering the commercial pathway for emerging energy technologies, and together they’re vital to the success of clean energy technology commercialization.

Opportunities for Support Through Congressional Control Points

The FY 2025 DOE request also looks to support the vital work of several new offices by establishing Congressional control points – meaning they’d be treated as standalone entities in appropriations, rather than subaccounts of other offices. Last year’s request sought new control points for the Office of State and Community Energy Programs, Federal Energy Management Program, and Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains, but Congress has yet to act.

It’s an incredibly wonky topic, but it’s actually pretty important: establishing control points for these offices can help create a baseline for future funding and maintain institutional consistency. Becoming standalone offices can also help them carry out their missions, by giving them the authority to engage with other partners including federal agencies, creating more pathways for collaboration with energy-intensive agencies like the Defense Department.

President Looks to Education Innovation in the FY25 Budget Request

On March 11, 2024, the President released his budget for Fiscal Year 2025, and it spells good news for advocates and educators who are concerned about research and development opportunities and infrastructure in the education sector. New funding caps imposed by the Fiscal Responsibility Act have tempered many advocates’ expectations. However, by requesting increases for key federal education R&D programs across multiple agencies, the Biden-Harris administration has signaled that it continues to value investments in education innovation, even in a budget-conscious political climate.

An analysis of the proposal by the Alliance for Learning Innovation (ALI) found a lot to like. The President’s Budget would send $815.5 million to the Institute for Education Sciences (IES) to invest in education research, development, dissemination, and evaluation. This is $22.5 million higher than IES received in Fiscal Year 2024. This includes $38.5 million for Statewide Longitudinal Data Systems, a 35 percent increase over Fiscal Year 2024.

Notably, the President is asking for $52.7 million to grow the Accelerate, Transform, and Scale (ATS) Initiative at IES. This is 76 percent higher than the $30 million IES originally put into the initiative in 2023 when Congress directed the agency to “use a portion of its fiscal year 2023 appropriation to support a new funding opportunity for quick turnaround, high-reward scalable solutions intended to significantly improve outcomes for students.”

The ATS Initiative, widely regarded as a pilot for a possible National Center for Advanced Development in Education, is inspired by Advanced Research Project Agencies across the federal government – and around the world – that build insights from basic research to develop and scale breakthrough innovations. Like ARPAs, ATS invests in big ideas that emerge from interdisciplinary, outside-the-box collaboration. It aims to solve the nation’s steepest challenges in education.

The President’s request for ATS includes $2 million for a new research and development center on how generative artificial intelligence is being used in classrooms across the U.S. According to the Congressional Justification for IES, this new center will “develop and test innovative uses of this technology and will establish best practices for evidence building about generative AI in education that not only address the effectiveness of the technology for learning, but also consider issues of bias, fairness, transparency, trust and safety.”

Outside of IES, the President’s Budget calls for additional investments in education innovation. For example, it requests $269 million for the Education Innovation and Research program, housed at the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Elementary and Secondary Education. If fulfilled, this would be a $10 million increase over last year. The President also wants Congress to send $100 million to the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education to expand R&D infrastructure at four-year Historically Black Colleges or Universities, Tribally Controlled Colleges or Universities, and Minority-Serving Institutions.

The Biden-Harris administration’s support for education R&D is also reflected in its requests for the National Science Foundation (NSF). The President’s Budget requests $1.3 billion for the NSF’s Directorate for STEM Education – $128 million above its Fiscal Year 2024 level. Moreover, it includes $900 million to fund the important work of NSF’s newest directorate, authorized in the CHIPS and Science Act: the Technology, Innovation, and Partnerships (TIP) Directorate. TIP runs important R&D initiatives, such as the VITAL Prize Challenge and America’s Seed Fund, that support teaching and learning innovations.

ALI looks forward to advocating for a robust investment in education R&D in Fiscal Year 2025. The President’s Budget provides a solid marker for the coalition’s efforts.

Firefighting Workforce Benefits from FY25 Budget Request but Sustained Investments are Necessary to Address the Wildfire Crisis

Despite growing federal spending on wildfire suppression, wildfires continue to grow in size and severity in the U.S. Nearly 100,000 structures have been wiped out by wildfires nationwide in the last two decades. Impacts of fires go far beyond what the flames touch; smoke from uncontrolled fires is worsening human health from coast to coast.

We know uncontrolled wildfire is costly, but a full accounting of just how costly is elusive given currently available data. Federal spending on wildfire suppression has exceeded $1 billion every year since 2011, with spending sometimes as high as $4 billion; longer-term costs imposed on livelihoods, ecosystem services, and health are estimated to be much higher.

Investments in prevention (including beneficial fire to reduce highly flammable vegetation) are essential for decreasing these skyrocketing costs in the long-term. The Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission, which submitted a detailed report to Congress in 2023 with recommendations for improving how we manage wildland fire, noted that the historic focus on putting out fires without substantial investment in risk mitigation “perpetuates a reactive and expensive cycle and consigns ourselves to an ever-increasing catalog of loss.”

In the last decade, the U.S. has made significant investments to address the wildfire crisis, including the historic investments in hazardous fuels reduction through the IRA and IIJA. But discretionary funding via the annual appropriations cycle has provided additional opportunities for Congress to make down payments on a more wildfire-resilient future. These investments include doubling of wildfire funding for the Department of Interior (DOI) and the U.S. Forest Service from fiscal year 2011 to 2020 (although much of this funding was for suppression-related activities).

The president’s FY 2025 budget would add to this growth via modest but important increases for sustaining or enhancing wildfire work at specific agencies. Areas of focused investment include increases to support pay, health and wellbeing, and housing for wildland firefighters in recognition that “the federal government must provide a level of pay that is competitive with the compensation provided by state, local, and private employers.” The FY 2025 budget would also include increased or sustained funds for certain programs at the Federation Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to improve community capacity for wildfire preparedness. It also supports certain Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) programs that concern wildfire smoke.

Wildfire in the FY25 Request

Below are a few highlights from the president’s FY 2025 budget concerning key activities at select agencies with relevance to wildfire. These highlights are just a sampling and do not constitute a comprehensive assessment of wildfire appropriations in the FY 2025 president’s budget at these or other agencies. The full spectrum of federal entities that undertake wildland fire activities is broader and includes NASA, NOAA, DOD, and CDC among others.

U.S. Forest Service

- INCREASE: $2.6 billion for the Wildland Fire Management account, an increase of 10% from FY 2024. This includes $216 million “to further build on the base pay increases” in the IIJA and “a $10 million investment in health and wellbeing services for wildland firefighters.”

- INCREASE: $207 million for Hazardous Fuels programs in the National Forest System account, an increase of 18% from FY 2024.

- INCREASE: $2.3 billion for the Wildfire Suppression Operations Reserve Fund, an increase of 4% from FY 2024. This fund, which went into effect in 2020, was designed to reduce borrowing from agency mitigation budgets to meet suppression needs.

Department of the Interior

- INCREASE: $569 million total for Preparedness, a 16% increase from FY 2024. The majority of this increase focuses on workforce capacity, wellbeing, and compensation for wildland firefighters.

- INCREASE: Fuels Management would be funded at $288 million, a 34% from FY 2024 increase primarily comprising firefighter compensation.

Federal Emergency Management Agency

- INCREASE: $385 million each for Assistance to Firefighters Grants and Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response (SAFER) Grants, 19% increases above FY 2024

- INCREASE: $375 million for Emergency Management Performance Grants, a 17% increase above FY 2024

- INCREASE: A 14% increase above FY 2024 for the Disaster Relief Fund Major Disasters Allocation, an increase FEMA attributes to “updated estimates for major disasters” developed with impacted communities.

- $1 billion is set aside for Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) through the Major Disasters Allocation. These funding levels for BRIC, which supports community investment in risk reduction for wildfire and other disasters, are consistent with FY 2023 and relatively standard for the program.

- NEW INVESTMENT: A total of $7 million for the modernization of the National Emergency Response Information System (NERIS) data analytics platform, which will replace a legacy system and serve as a decision-support tool for fire and emergency responders.

Environmental Protection Agency

- FLAT: Sustained funding for the Wildfire Smoke Preparedness grant program, created in 2023 and funded at $7 million in FY 2024.

- INCREASE: 6% increase in Categorical Grants to support air pollution control agencies in activities including “implementing, attaining, maintaining, and enforcing the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for criteria pollutants.” One of these criteria pollutants is PM2.5, found in wildfire smoke.

The Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission released its report to Congress in September 2023, likely too late for its 148 recommendations to be considered thoroughly in agency budget development. While this budget request lays a foundation for important Commission recommendations such as pay increases and housing for federal wildland firefighters, significant additional investments will still be needed in the years to come. The Commission noted that “investments at a similar and sustained scale (to the IRA and IIJA) in federal land management agencies and programs are needed to successfully and proactively reduce growing wildfire risk,” and recommended strong support for wildland fire management through land management agencies to the tune of $85-95 billion total in the next decade (almost triple what has already been invested). Additionally, it recommended funding to support other agencies with critical roles in addressing the wildfire crisis including FEMA, NOAA, and EPA.

While agency budget documents give us a general sense of the magnitude of investments in wildland fire at each agency, we don’t actually have a clear picture of wildfire spending across the federal government as a whole. As Taxpayers for Common Sense found, there is no single federal definition of what falls under the category of wildfire spending. Federal entities such as the Department of Agriculture, DOI, and FEMA use different budget structures to describe their direct and indirect spending on wildland fire (although DOI does package all of its wildfire spending into a department-wide budget).

Consequently, agencies, Congress, and the public are limited in their ability to assess wildland fire spending government-wide. An important Commission recommendation is thus that Congress “fund agency budgets offices to create crosscuts to better track all federal wildfire spending.” We highlighted this recommendation for Congress (along with other Commission recommendations on wildfire spending and budgeting) in a recent joint letter with The Pew Charitable Trusts, Taxpayers for Common Sense, and Megafire Action.

There is no magic bullet for solving our wildfire crisis, but sustained investments that strategically leverage science, technology, data, and the workforce and emphasize prevention can pave the way to a more resilient future.

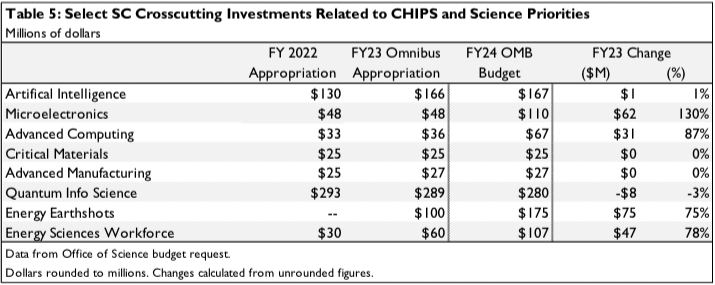

CHIPS and Science Funding Gaps Continues to Stifle Scientific Competitiveness

The bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act sought to accelerate U.S. science and innovation, to let us compete globally and solve problems at home. The multifold CHIPS approach to science and tech reached well beyond semiconductors: it authorized long-term boosts for basic science and education, expanded the geography of place-based innovation, mandated a whole-of-government science strategy, and other moves.

But appropriations in FY 2024, and the strictures of the Fiscal Responsibility Act in FY 2025, make clear that we’re falling well short of CHIPS aspirations. The ongoing failure of the U.S. to invest comes at a time when our competitors continue to up their investments in science, with China pledging 10% growth in investment, the EU setting forth new strategies for biotechnology and manufacturing, and Korea’s economy approaching 5% R&D investment intensity, far more than the U.S.

Research Agency Funding Shortfalls

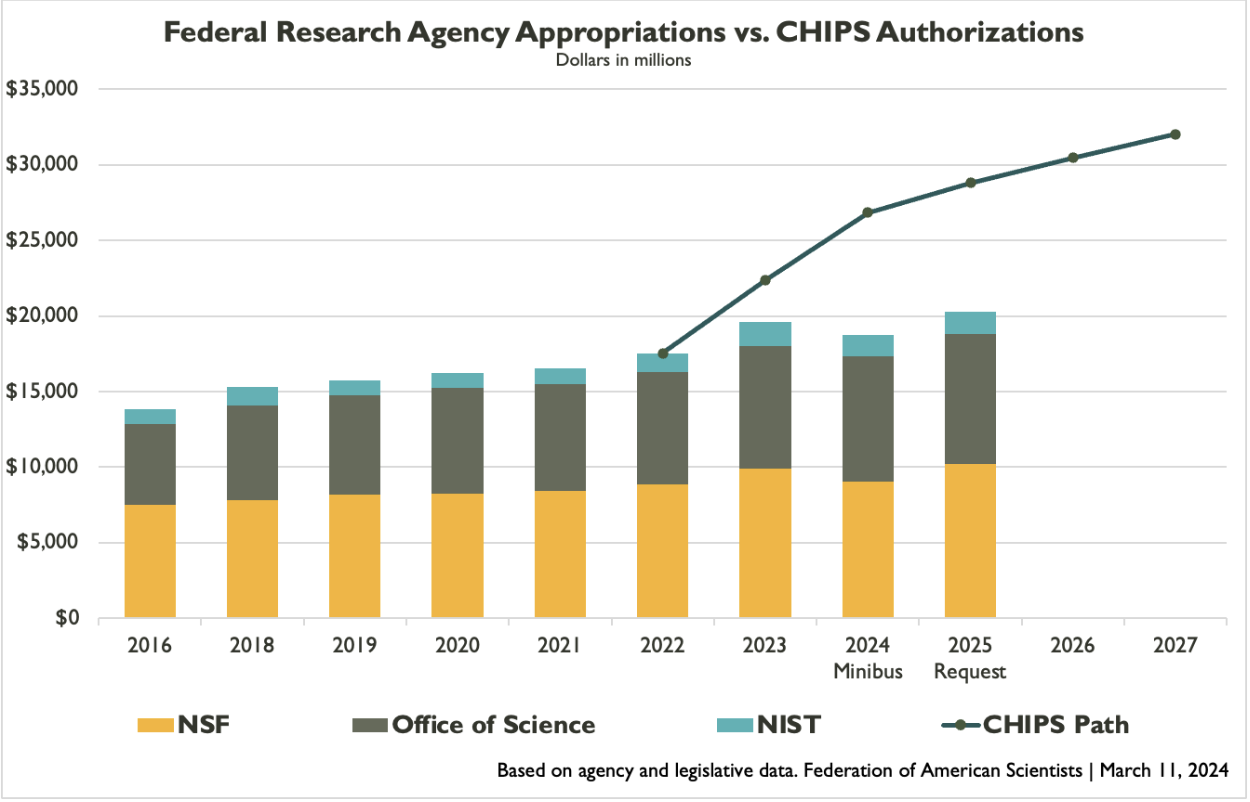

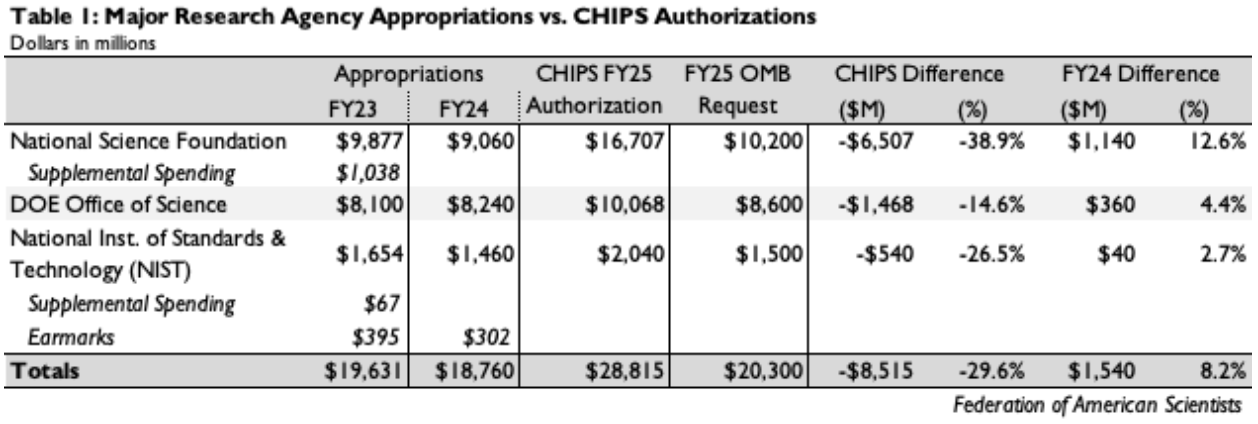

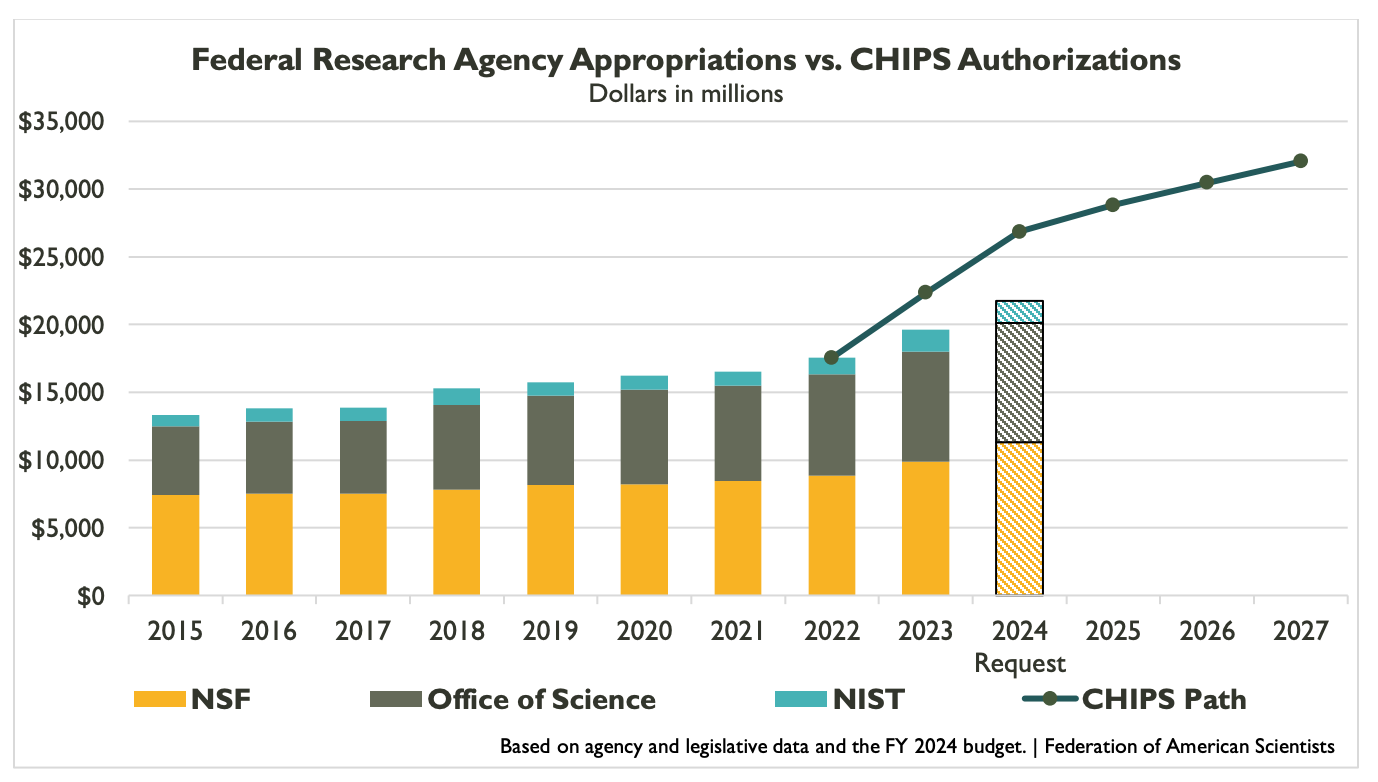

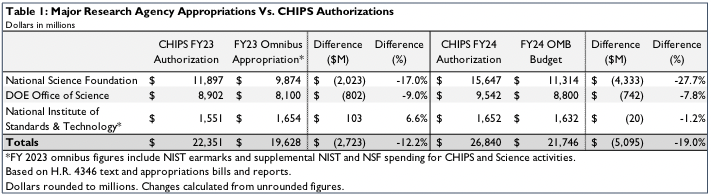

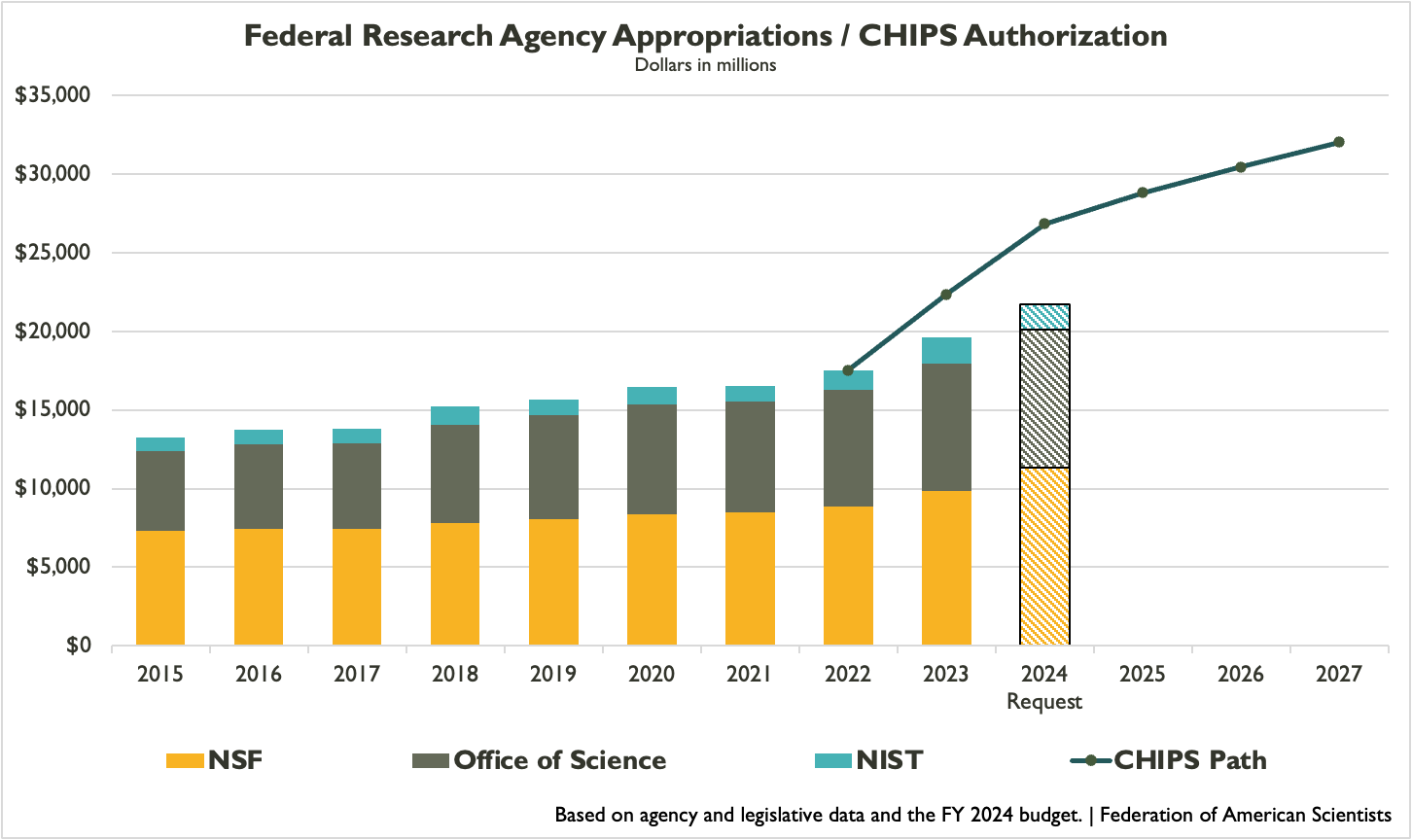

In the aggregate, CHIPS and Science authorized three research agencies – the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Department of Energy Office of Science (DOE SC), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) – to receive $26.8 billion in FY 2024 and $28.8 billion in FY 2025, representing substantial growth in both years. But appropriations have increasingly underfunded the CHIPS agencies, with a gap now over $8 billion (see graph).

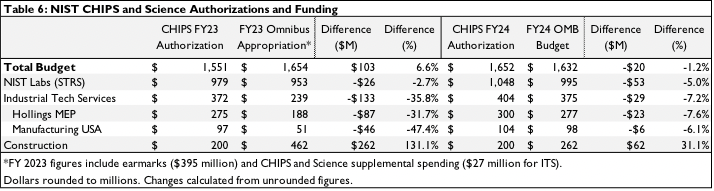

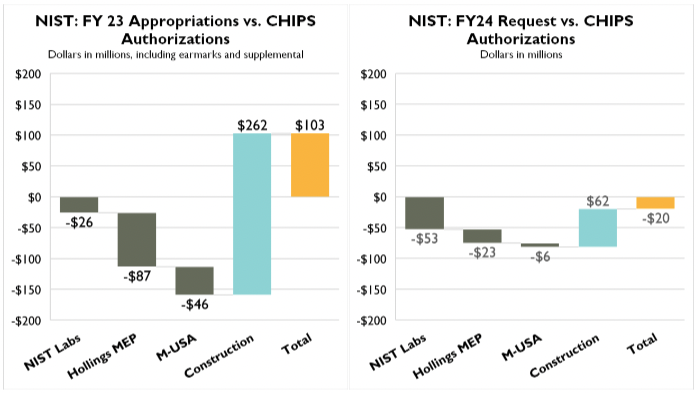

The table below shows agency funding data in greater detail, including FY 2023 and FY 2024 appropriations, the FY 2025 CHIPS authorization, and the FY 2025 request.

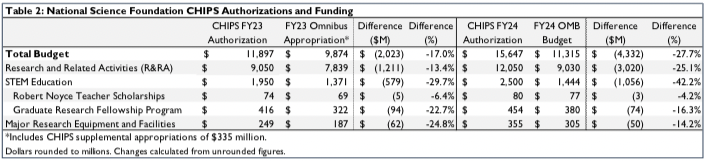

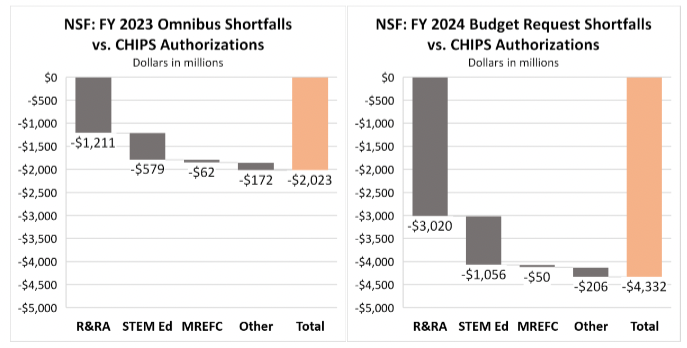

The National Science Foundation is experiencing the largest gap between CHIPS targets and actual appropriations following a massive year-over-year funding reduction in FY 2024. That cut is partly the result of appropriators rescuing NSF in FY 2023 with over $1 billion in supplemental spending to support both NSF base activities and implementation of the Technology, Innovation and Partnerships Directorate (TIP). While that spending provided NSF a welcome boost in FY 2023, it could not be replicated in FY 2024, and NSF only received a modest boost in base appropriations. As a result, the full year-over-decline for NSF amounted to over $800 million, which will likely mean cutbacks in both core and TIP (the exact distribution is to be determined though Congress called for an even-handed approach). It also means a CHIPS shortfall of $6.5 billion in both FY 2024 and FY 2025.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology also requires some additional explanation. Like NSF, NIST received some supplemental spending for both lab programs and industrial innovation in FY 2023, but NIST also has been subject to quite substantial earmarks in FY 2023 and FY 2024, as seen in the table above. The presence of earmarks in FY 2024 meant, in practice, a nearly $100 million reduction in funding for core NIST lab programs, which cover a range of activities in measurement science and emerging technology areas.

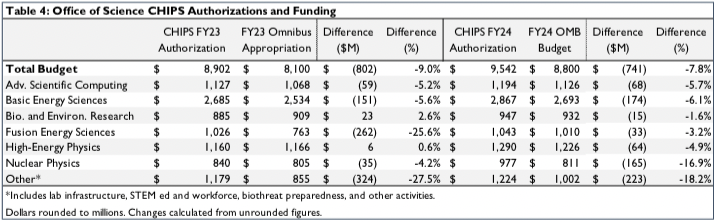

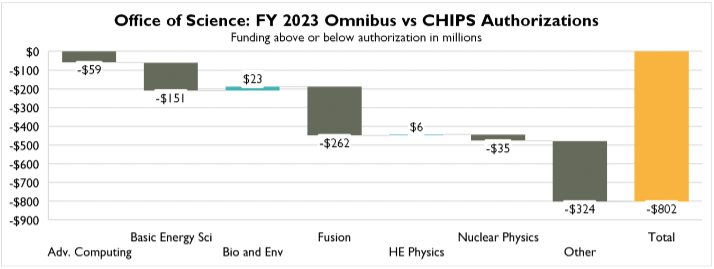

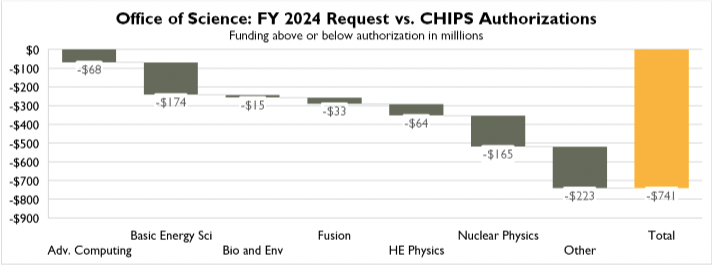

The Department of Energy’s Office of Science fared better than the other two in the omnibus with a modest increase, but still faces a $1.5 billion shortfall below CHIPS targets in the White House request.

Select Account Shortfalls

National Science Foundation

Core research. Excluding the newly-created TIP Directorate, purchasing power of core NSF research activities in biology, computing, engineering, geoscience, math and physical sciences, and social science dropped by over $300 million between FY 2021 and FY2023. If the FY 2024 funding cuts are distributed proportionally across directorates, their collective purchasing power would have dropped by over $1 billion all-in between FY 2021 and the present, representing a decline of more than 15%. This would also represent a shortfall of $2.9 billion below the CHIPS target for FY 2024, and will likely result in hundreds of fewer research awards.

STEM Education. While not quite as large as core research, NSF’s STEM directorate has still lost over 8% of its purchasing power since FY 2021, and remains $1.3 billion below its CHIPS target after a 15% year-over-year cut in the FY 2024 omnibus. This cut will likely mean hundreds of fewer graduate fellowships and other opportunities for STEM support, let alone multimillion-dollar shortfalls in CHIPS funding targets for programs like CyberCorps and Noyce teacher scholarships. The minibus did allocate $40 million for the National STEM Teacher Corps pilot program established in CHIPS, but implementing this carveout will pose challenges in light of funding cuts elsewhere.

TIP Programs. FY 2023 funding fell over $800 million shy of the CHIPS target for the new technology directorate, which had been envisioned to grow rapidly but instead will now have to deal with fiscal retrenchment. Several items established in CHIPS remain un- or under-funded. For instance, NSF Entrepreneurial Fellowships have received only $10 million from appropriators to date out of $125 million total authorized, while Centers for Transformative Education Research and Translation – a new initiative intended to research and scale educational innovations – has gotten no funding to date. Also underfunded are the Regional Innovation Engines (see below).

Department of Energy

Microelectronics Centers. While the FY 2024 picture for the Office of Science (SC) is perhaps not quite as stark as it is for NSF – partly because SC didn’t enjoy the benefit of a big but transient boost in FY 2023 – there remain underfunded CHIPS priorities throughout. One more prominent initiative is DOE’s Microelectronics Science Research Centers, intended to be a multidisciplinary R&D network for next-generation science funded across the SC portfolio. CHIPS authorized these at $25 million per center per year.

Fission and Fusion. Fusion energy was a major priority in CHIPS and Science, which sought among other things expansion of milestone-based development to achieve a fusion pilot plant. But following FY 2024 appropriations, the fusion science program continues to face a more than $200 million shortfall, and DOE’s proposal for a stepped-up research network – now dubbed the Fusion Innovation Research Engine (FIRE) centers – remains unfunded. CHIPS and Science also sought to expand nuclear research infrastructure at the nation’s universities, but the FY 2024 omnibus provided no funding for the additional research reactors authorized in CHIPS.

Clean Energy Innovation. CHIPS Title VI authorized a wide array of energy innovation initiatives – including clean energy business vouchers and incubators, entrepreneurial fellowships, a regional energy innovation program, and others. Not all received a specified funding authorization, but those that did have generally not yet received designated line-item appropriations.

NIST

In addition to the funding challenges for NIST lab programs described above – which are critical for competitiveness in emerging technology – NIST manufacturing programs also continue to face shortfalls, of $192 million in the FY 2024 omnibus and over $500 million in the FY 2025 budget request.

Regional Innovation

As envisioned when CHIPS was signed, three major place-based innovation and economic development programs – EDA’s Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs (Tech Hubs), NSF’s Regional Innovation Engines (Engines), and EDA’s Distressed Area Recompete Pilot Program (Recompete) – would be moving from exclusively planning and selection into implementation phases as well in FY25. But with recent budget announcements, some implementation may need to be scaled back from what was originally planned, putting at risk our ability to rise to the confluence of economic and industrial challenges we face.

EDA Tech Hubs. In October 2023, the Biden-Harris administration announced the designation of 31 inaugural Tech Hubs and 29 recipients of Tech Hubs Strategy Development Grants from nearly 400 applicants. These 31 Tech Hubs designees were chosen for their potential to become global centers of innovation and job creators. Upon announcement, the designees were then able to apply to receive implementation grants of $40-$70 million to each of approximately 5-10 of the designated Tech Hubs. Grants are expected to be announced in summer 2024.

The FY 2025 budget request for Tech Hubs includes $41 million in discretionary spending to fund additional grants to the existing designees, and another $4 billion in mandatory spending – spread over several years – to allow for additional Tech Hubs designees and strategy development grants. CHIPS and Science authorized the Hubs at $10 billion in total, but the program has only received 5% of this in actual appropriations to date. The FY25 request would bring total program funding up to 46% of the authorization.

The ambitious goal of Tech Hubs is to restore the U.S. position as a leader in critical technology development, but this ambition is dependent on our ability to support the quantity and quality of the program as originally envisioned. Without meeting the funding expectations set in CHIPS, the Tech Hubs’ ability to restore American leadership will be vastly limited.

NSF Engines. In January 2024, NSF announced the first NSF Engines awards to 10 teams across the United States. Each NSF Engine will receive an initial $15 million over the next two years with the potential to receive up to $160 million each over the next decade.

Beyond those 10 inaugural Engines awards, a selection of applicants were invited to apply for NSF Engines development awards, with each receiving up to $1 million to support team-building, partnership development, and other necessary steps toward future NSF Engines proposals. NSF’s initial investment in the 10 awardee regions is being matched almost two to one in commitments from local and state governments, other federal agencies, private industry, and philanthropy. NSF previously announced 44 Development Awardees in May 2023.

To bolster the efforts of NSF Engines, NSF also announced the Builder Platform in September 2023, which serves as a post-award model to provide resources, support, and engagement to awardees.

The FY25 request level for NSF Engines is $205 million, which will support up to 13 NSF Regional Innovation Engines. While this $205 million would be a welcome addition – especially in light of the funding risks and uncertainty in FY24 mentioned above – total funding to date is considerably below CHIPS aspirations, accounting for just over 6% of authorized funding.

EDA Recompete. The EDA Recompete Program, authorized for up to $1 billion in the CHIPS and Science Act, aims to allocate resources towards economically disadvantaged areas and create good jobs. By targeting regions where prime-age (25-54 years) employment lags behind the national average, the program seeks to revitalize communities long overlooked, bridging the gap through substantial and flexible investments.

Recompete received $200 million in appropriations in 2023 for the initial competition. This competition received 565 applications, with total requests exceeding $6 billion. Of those applicants, 22 Phase 1 Finalists were announced in December 2023.

Recompete Finalists are able to apply for the Phase 2 Notice of Funding Opportunity and are provided access to technical assistance support for their plans. In Phase 2, EDA will make approximately 4-8 implementation investments, with awarded regions receiving between $20 to $50 million on average.

Alongside the 22 Finalists, Recompete Strategy Development Grant recipients were announced. These grants support applicant communities in strategic planning and capacity building.

Following a shutout in FY 2024 appropriations, Recompete funding in the FY25 request is $41 million, bringing total funding to date to $241 million or just over 24% of authorized funding.

Congress will soon have the chance to rectify these collective shortfalls, with FY 2025 appropriations legislation coming down the pike soon. But the November elections throw substantial uncertainty over what was already a difficult situation. If Congress can’t muster the votes necessary to properly fund CHIPS and Science programs, U.S. competitiveness will continue to suffer.

CHIPS and Science: FY24 Research Appropriations Short by Over $7 Billion

When Congress adopted the CHIPS and Science Act (P.L. 117-167) in 2022 on a bipartisan basis, it was intended to strengthen the United States’ ability to compete and to invest in solutions for national challenges. Beyond semiconductors, CHIPS and Science took an array of concrete steps to strengthen innovation: it provided strategic focus for the federal R&D enterprise, created investments in U.S. workers and regions, expanded the funding toolkit, and authorized boosts for science and education across the spectrum.

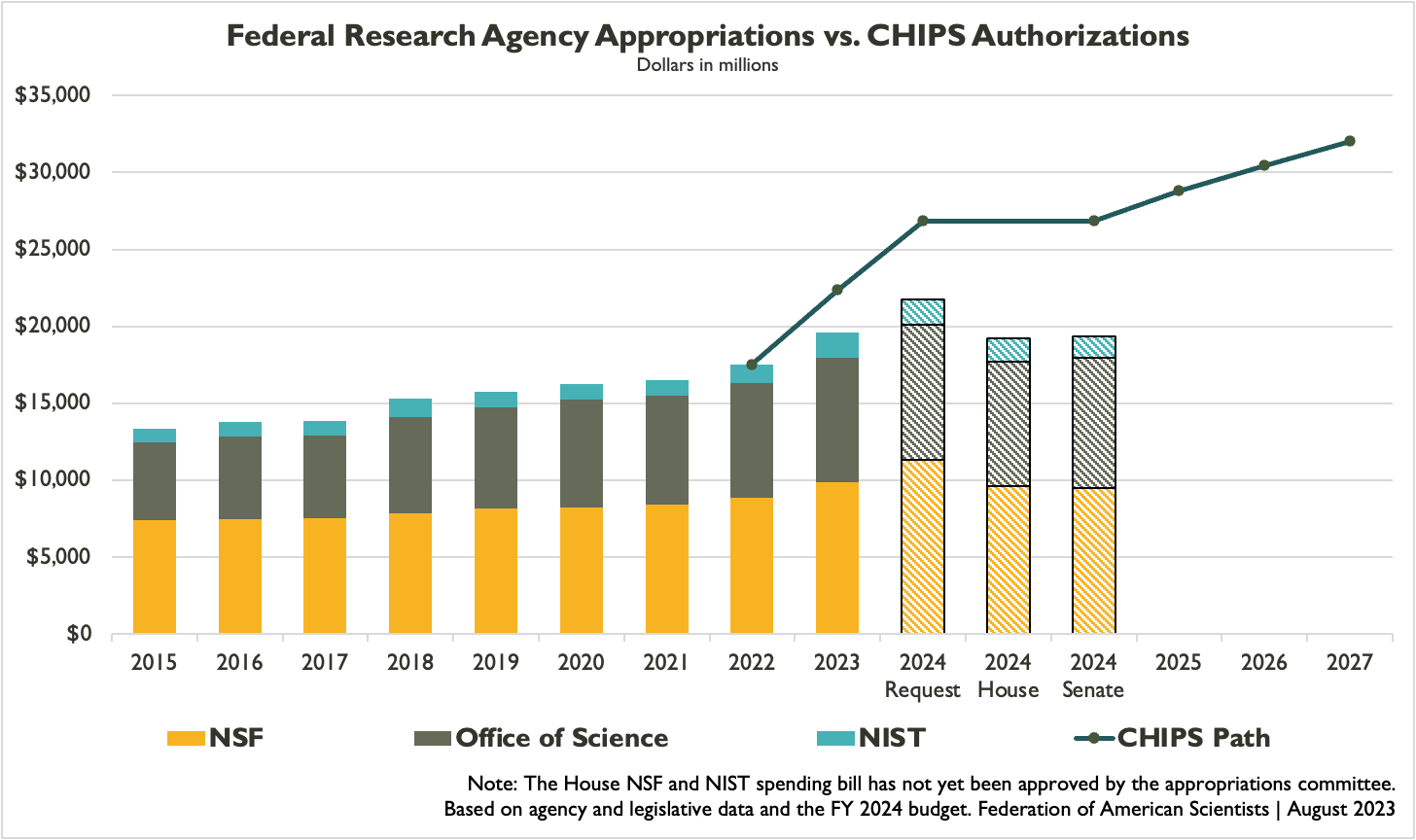

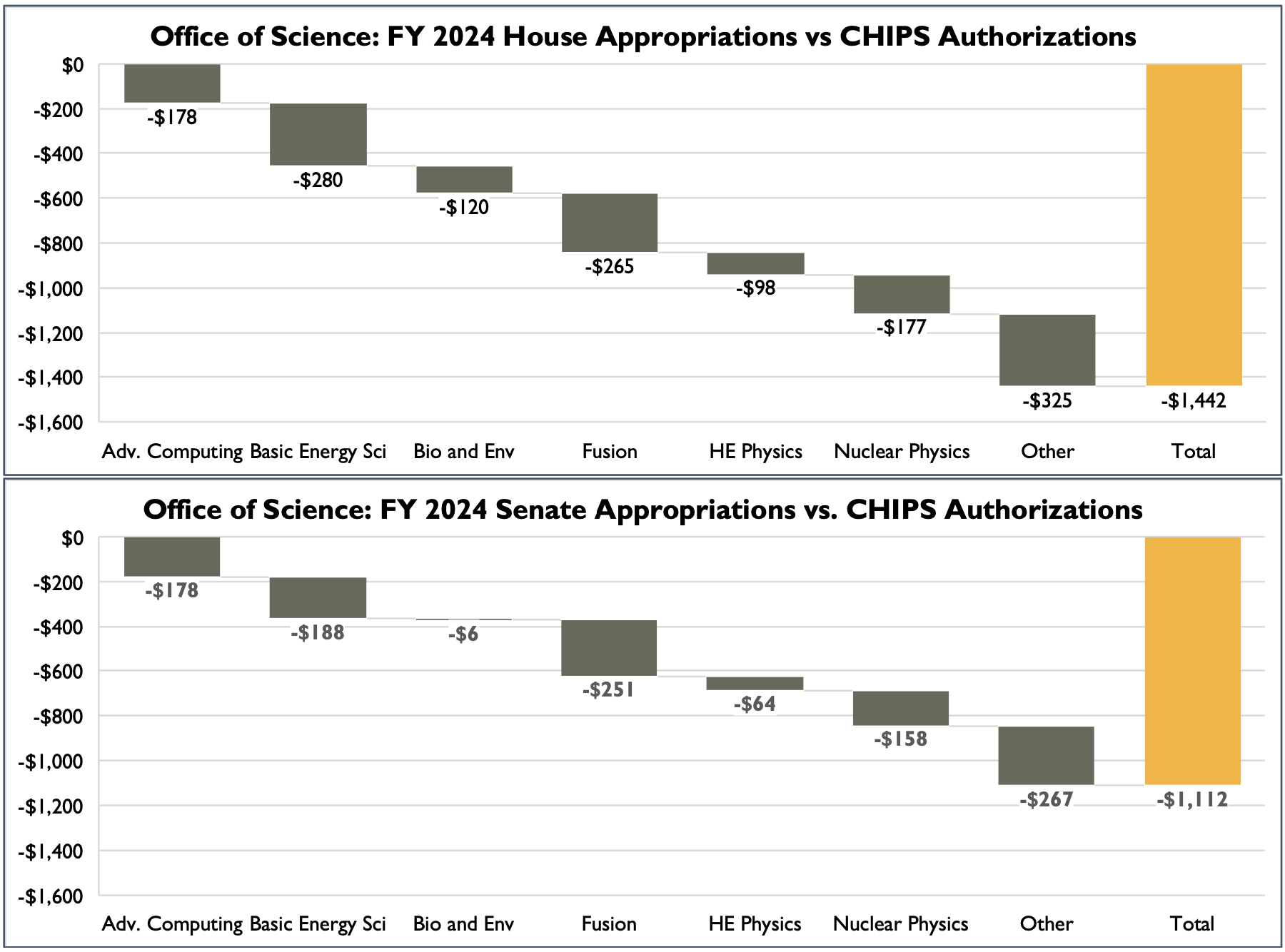

Such a varied approach is critical in the race for technological and economic advantage, as other nations mount challenges to U.S. leadership – particularly China, which has seized the lead in several key technology areas after years of accelerated investment. But despite this impetus, appropriations for research agencies have fallen quite short of the CHIPS and Science targets. Following an FY 2023 omnibus shortfall of nearly $3 billion, FY 2024 appropriations to date for research agencies are approximately $7.5 billion below authorized levels (see graph).

This report provides a detailed breakdown of accounts and programs for these agencies and compares current appropriations against those authorized by CHIPS and Science, as a reference and resource for policymakers and advocates.

CHIPS and Science Background

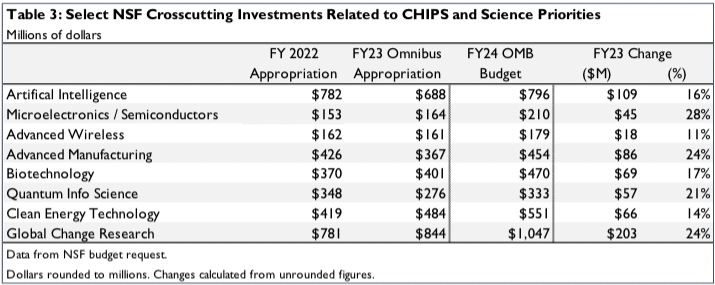

CHIPS and Science took manifold steps to strengthen the U.S. science enterprise. A conceptual throughline is the establishment of key technology focus areas and societal challenges defined in Section 10387, shown in the table below. While not the only priorities for federal R&D, these focus areas provide a framework to guide certain investments, particularly those by the National Science Foundation’s new technology directorate.

These key technology areas are also relevant for long-term strategy development by the Office of Science and Technology Policy and the National Science and Technology Council, as directed by CHIPS and Science. Several of the technology areas also appear on the Defense Department’s Critical Technologies list.

While much of the focus has been on semiconductors, the activities covered in this report constitute the bulk of the “and Science” portion of CHIPS and Science. While a full index of all provisions is not the goal here, it’s worth remembering the sheer variety of activities authorized in CHIPS and Science, which cut across areas including:

- Fundamental science and curiosity-driven research funded by science agencies at federal labs, universities, and companies. CHIPS and Science covered multiple disciplines but has a particular emphasis on the physical sciences, math and computer science, and engineering. Several of these disciplines have fallen dramatically within the federal portfolio in recent decades.

- Use-inspired research, translation, and production. Elements of CHIPS and Science sought to expand the ability of federal agencies to make strategic investments in emerging technologies, move new advances through the innovation chain, and work with external partners to enable the manufacture of new technologies and strengthen supply chains.

- Regional innovation. A major element of the above is emphasis on expanding the geographic footprint of federal investment, most notably through the new Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs program. The program received $500 million out of an authorized $10 billion in the FY 2023 omnibus.

- STEM education and workforce. The Act expands or creates numerous programs to foster STEM skills, opportunity and experience among students and young researchers, including through entrepreneurial fellowships, student and educator support, and apprenticeships and worker upskilling initiatives.

- Research facilities and instrumentation at national labs and universities across the country, including modernization of aging infrastructure, construction of cutting-edge user facilities, and grants for mid- scale research infrastructure projects.

Aggregate Agency Appropriations

In the aggregate, CHIPS and Science authorized three research agencies – the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Department of Energy Office of Science (DOE SC), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) – to receive $26.8 billion in FY 2024, a $4.5 billion boost from the FY 2023 authorizations. House and Senate appropriations to this point – including the House Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies bill, which was not adopted by the Appropriations Committee before the August break – amount to somewhat above $19 billion in both, representing a more than $7 billion or approximately 28% shortfall, in each (see Table 1 below). In fact, these aggregates represent not only a shortfall below the FY 2024 authorization, but a reduction of $250 million and $421 million, respectively, below FY 2023 appropriations, when factoring in FY 2023 NSF and NIST funding provided as supplemental.

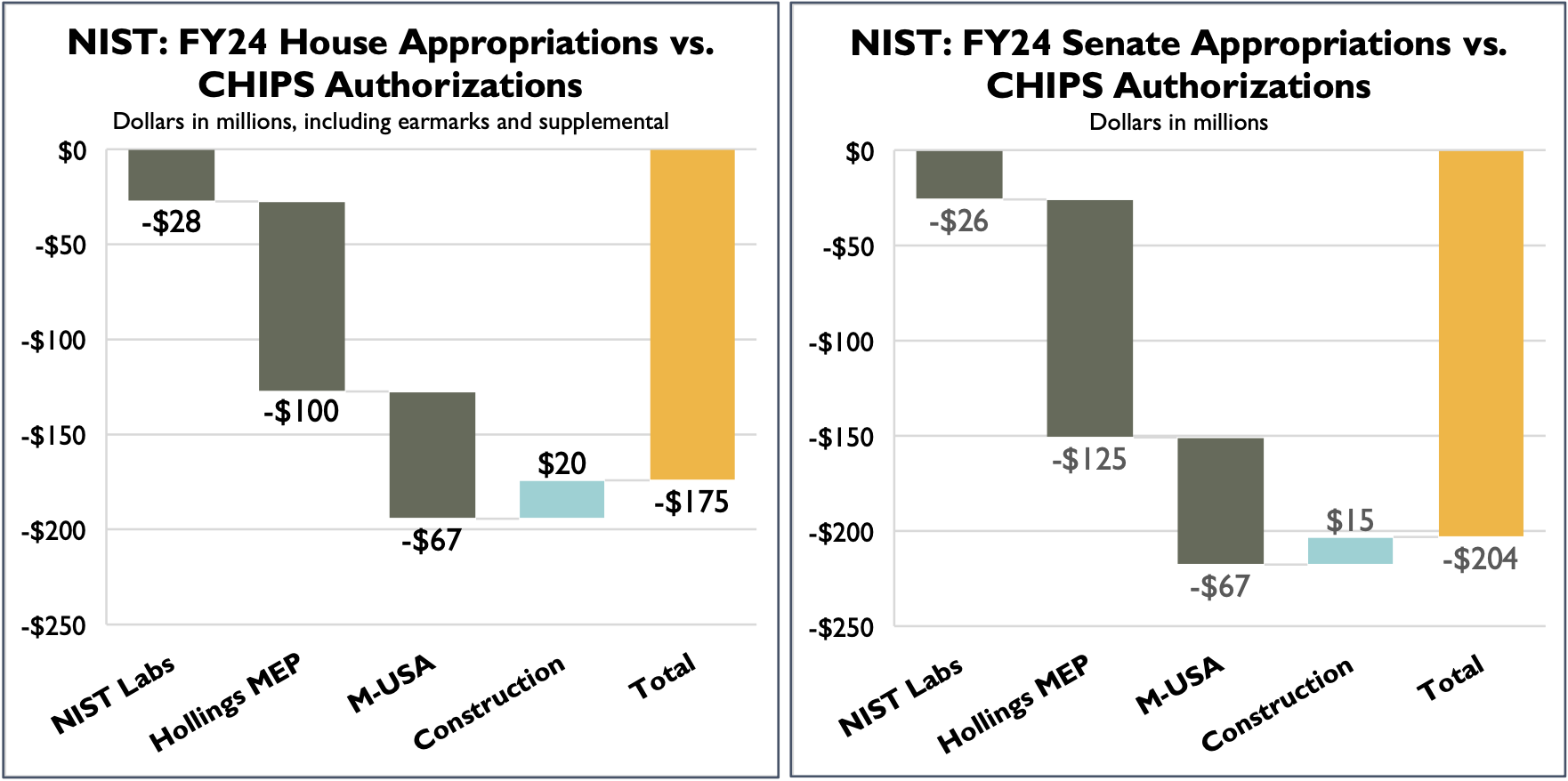

The gap for NIST grows larger when accounting for earmarks, which amounted to approximately $119 million in the House and $199 million in the Senate. Excluding earmarks, the NIST appropriation totals for FY 2024 result in shortfalls below the authorization of $294 million or 18% in the House, and $403 million or 24% in the Senate.

Agency Breakdowns

National Science Foundation

NSF is at the core of the CHIPS and Science goals in manifold ways. It boasts a long-term track record of excellence in discovery science at U.S. universities and is the first or second federal funder of research in several tech-relevant science and engineering disciplines. It also seeks to boost the talent pipeline by engaging with underserved research institutions and student populations, supporting effective STEM education approaches, and providing fellowships and other opportunities to students and teachers.

CHIPS and Science also expanded NSF’s ability to drive technology, innovation, and advanced manufacturing, augmenting existing innovation programs like the Engineering Research Centers and the Convergence Accelerators with new activities like the Regional Innovation Engines.

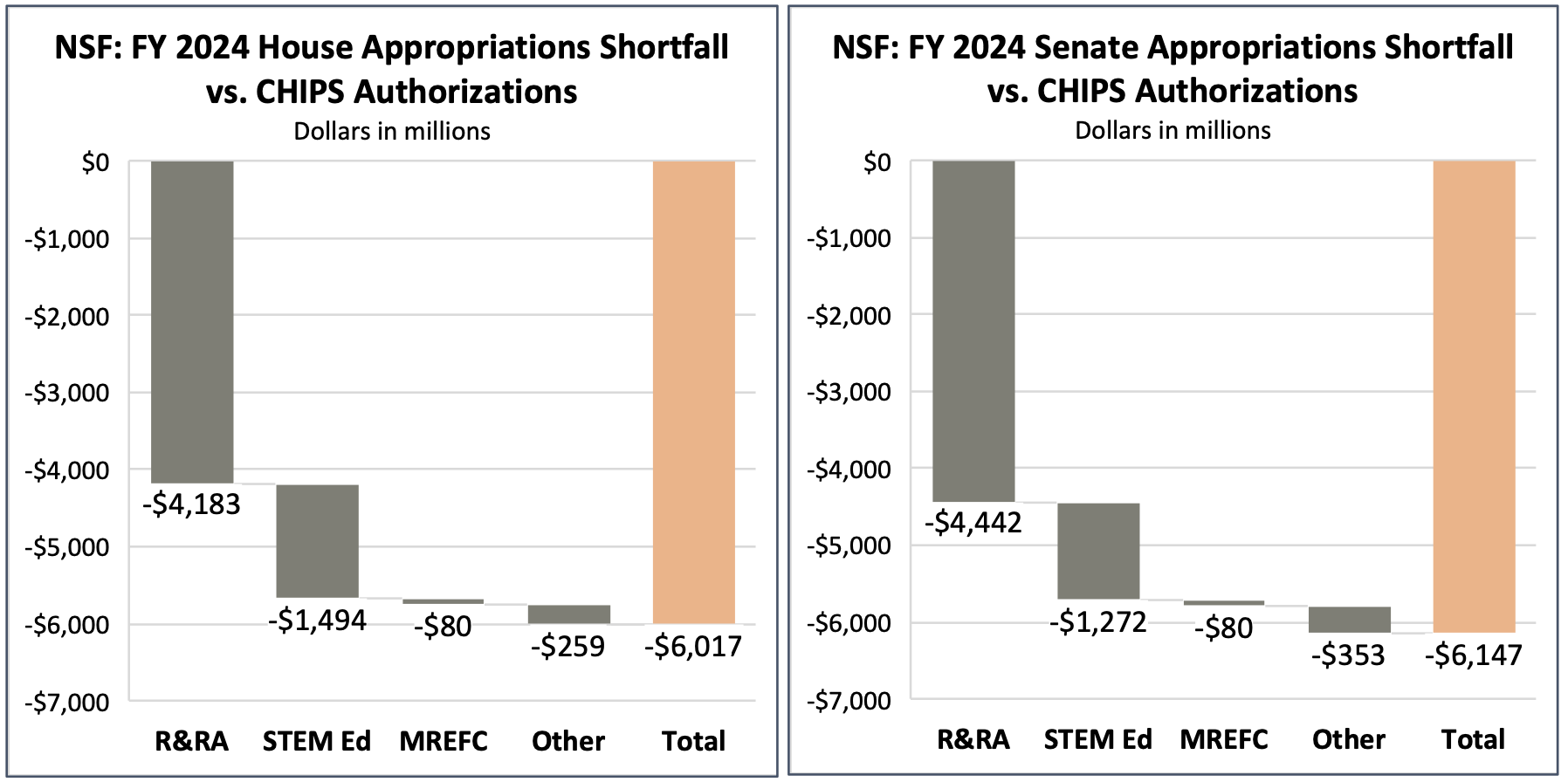

As seen in Table 2, the FY 2024 appropriations for NSF are roughly $6 billion or 39% below the CHIPS and Science authorization. The agency toplines are also 2.5% and 3.8% below FY 2023 figures in total, including FY 2023 supplemental spending.

In both the House and the Senate, FY24 Appropriations fall far short of CHIPS authorizations across research and education accounts.

Research & Related Activities (R&RA). R&RA is the primary research account for NSF, supporting grants, centers, instrumentation, data collection, and other activities across seven research directorates including the new Technology, Innovation, and Partnerships (TIP) directorate. These directorates play a foundational role in driving U.S. leadership in biology, computing and information science, engineering, geoscience, math and computer science, and social science, as well as integrated and international programs. R&RA can likely absorb substantial additional funding: the agency must routinely leave thousands of high-scoring grant proposals on the table for lack of funding. For instance, in FY 2021, NSF had to leave unfunded over 4,000 proposals amounting to $4.1 billion ranked “Very Good” or better.

In report language, Senate appropriators encourage NSF to initiate a contract with the National Academies to pursue a CHIPS and Science-mandated assessment of the key technology focus areas. For FY 2024, Senate appropriators have provided the same funding as FY 2023 for the Regional Innovation Engines, quantum information science activities, and AI research. The EPSCoR program received $275 million, a $20 million increase. House appropriators have not yet released appropriations report language for NSF.

STEM Education. The Directorate for STEM Education houses NSF activities across K-12, tertiary education, learning in informal settings, and outreach to underserved communities. CHIPS and Science authorized increased funding for multiple individual programs including Graduate Research Fellowships, Robert Noyce Teacher Fellowships Program, CyberCorps, and the new Centers for Transformative Education Research and Translation, among others. These programs serve an array of functions, including STEM teacher recruitment, support for the federal cybersecurity workforce, and support for a range of learners and institutions including veterans and underrepresented minorities.

Senate appropriators provided a mix of small changes, flat funding, or trims from FY 2023 levels to several NSF STEM programs including graduate and Noyce fellowships, the HBCU Undergraduate Program and the Centers for Research Excellence in Science and Technology (CREST). In most cases these figures were all well short of CHIPS and Science targets. Notably, Senate appropriators provided $40 million for a National STEM Teacher Corps pilot program and encouraged NSF to establish a Centers for Transformative Education Research and Translation, both authorized in CHIPS and Science.

Department of Energy Office of Science

The Office of Science (SC) is the largest funder of the physical sciences including chemistry, physics, and materials, all of which contribute to the technology priorities in CHIPS and Science. In addition to funding Nobel prizewinning basic research and large-scale science infrastructure, the Office also funds workforce development, use-inspired research, and user facilities that provide tools for tens of thousands of users each year, including hundreds of small and large businesses that use these services to drive breakthroughs. More than two thirds of SC-funded R&D is performed at national labs. SC also supports workforce development and educational activities for students and faculty to expand skills and experience.

As seen in Table 3, topline FY 2024 appropriations have been over $1 billion or at least 12% short of the CHIPS authorization in both chambers. House appropriations have been flat from the FY 2023 omnibus while Senate appropriators have provided SC with a 4% increase overall.

Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) funds research in AI, computational science, mathematics, and networking. Among CHIPS and Science priorities, ASCR will begin to establish a dedicated Quantum Network along with other research, testbeds, and applications in FY 2024. CHIPS and Science authorized $31.5 million in FY 2024 for the QUEST Act, to give U.S. researchers access to quantum hardware and research cloud resources, while House appropriators have provided up to $15 million. CHIPS also authorized $100 million for provision of quantum network infrastructure. Senate appropriators directed DOE to provide an update on its plan to sustain U.S. leadership in advanced computing including in AI, zettascale computing, and quantum computing.

Basic Energy Sciences (BES), the largest SC program, supports fundamental science disciplines with relevance for several CHIPS technology areas including materials, microelectronics, AI, and others, as well as extensive user facilities and other novel initiatives. CHIPS and Science authorizations for FY 2024 included research and innovation hubs related to artificial photosynthesis ($100 million) and energy storage ($120 million). Both committees funded the innovation hubs on these topics at $20 million and $25 million, respectively. CHIPS also authorized $50 million per year for carbon materials and storage research in coal-rich U.S. regions.

Biological and Environmental Research (BER) supports research in biological systems science including genomics and imaging, and in earth systems science and modeling. BER programs have fared quite differently in appropriations, with House appropriators reducing funding by $82 million or 9% below FY 2023 omnibus levels, while BER would receive a $32 million or 4% boost in the Senate.

Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) supports research into matter at high densities and temperatures to lay the groundwork for fusion as a future energy source. Appropriations thus far have provided far less than requested for public-private partnerships to support and expand the domestic fusion industry. The Milestone-Based Development Program, to develop technology roadmaps and achieve progress toward fusion pilot plants, would receive $35 million in the House and not less than $25 million in the Senate, versus a combined request of $135 million for the milestone program and the Innovation Network for Fusion Energy (INFUSE) program, which enables industry partnerships with national labs and American universities.

Energy Earthshots are a crosscutting DOE initiative to tackle challenges at the nexus of basic and applied R&D through multidisciplinary team science, thus enabling DOE to better achieve progress in the CHIPS- identified advanced energy technology focus area. Appropriations thus far would dramatically scale back SC’s Earthshot investments from FY 2023 levels. House appropriators would provide $20 million and Senate appropriators $67 million for SC’s portion of the Earthshot initiative, versus FY 2023 funding of $100 million and an FY 2024 request level of $175 million. Ongoing Earthshots address hydrogen, energy storage, carbon removal, enhanced geothermal, offshore wind, industrial heat, and clean fuels, with additional projects anticipated in FY 2024.

Quantum Information Science is a priority for both CHIPS and Science and in the Administration’s request, but appropriations remain limited. House appropriators have provided not less than $245 million, same as the FY 2023 omnibus level, while the Senate provided a $10 million or 4% increase.

National Institute of Standards and Technology

While smaller than the other agencies covered here, NIST plays a critical role in the U.S. industrial ecosystem as the lead agency in measurement science and standards-setting, as well as funder of world-class physical science research and user facilities. NIST R&D activities cover several CHIPS And Science technology priorities including cybersecurity, advanced communications, AI, quantum science, and biotechnology. NIST also boasts a wide-ranging system of manufacturing extension centers in all 50 states and Puerto Rico, which help thousands of U.S. manufacturers grow and innovate every year.

As seen in Table 4, the NIST appropriation – which doesn’t include mandatory semiconductor funding – is 11% to 12% below the CHIPS and Science level for FY 2024. These figures include earmarks of $119 million and $199. Excluding earmarks, the NIST shortfalls are 18% in the House and 24% in the Senate.

Scientific and Technical Research Services (STRS) is the account for NIST’s national measurement and standards laboratories, which pursue a wide variety of CHIPS and Science-relevant activities in cybersecurity, AI, quantum information science, advanced communications, engineering biology, resilient infrastructure, and other realms. STRS also funds two user facilities, the NIST Center for Neutron Research and the Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology.

Excluding FY 2024 House and Senate earmarks, NIST lab programs would receive cuts of approximately $50 million under current appropriations.

House report language for NIST has not yet been adopted, but Senate appropriators approved the requested $5 million increase for quantum information science, while providing cybersecurity funding no less than FY 2023 levels and holding AI research flat at FY 2023 enacted levels. Critical and emerging technology investments received a $12 million increase versus the requested $20 million boost.

Industrial Technology Services is the overarching account funding the Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) and the Manufacturing USA innovation network. As can be seen in Table 4, these programs collectively faced a much greater authorization shortfall than NIST lab programs.

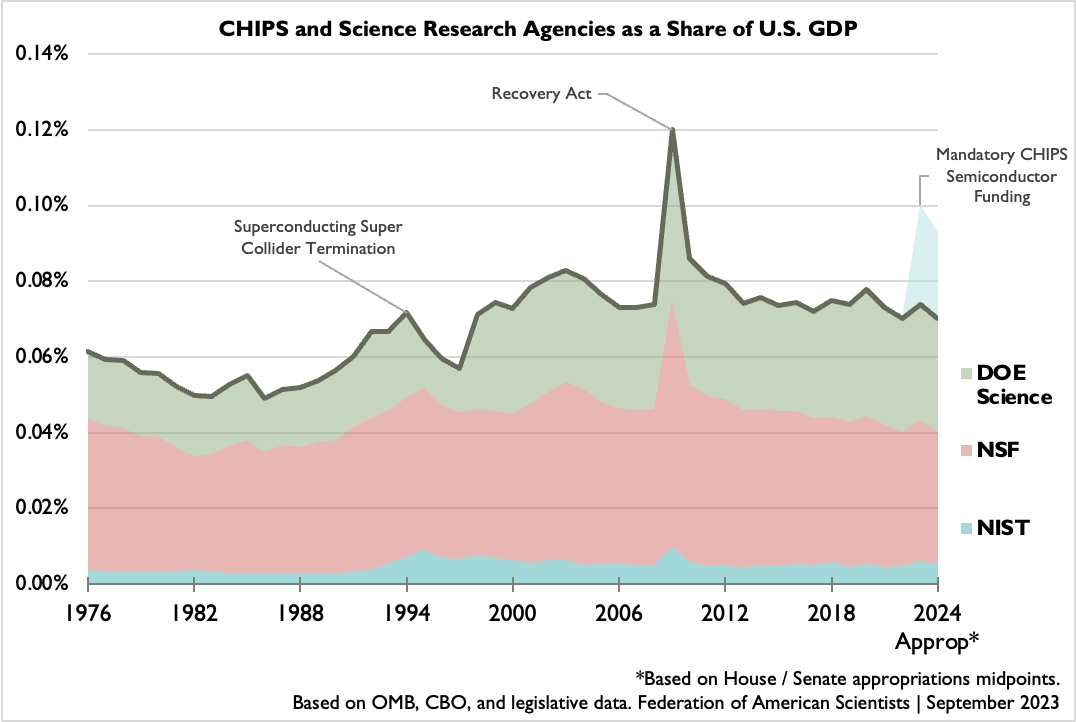

Appropriations in Historical Context

Relative funding for NSF, SC and NIST has evolved over the decades, as seen in the graph on the following page. As a share of the U.S. economy, funding for the three agencies experienced marked decline in the late 1970s and early 1980s, dropping to 0.05% of U.S. GDP in the mid-1980s. Beginning in the later Reagan era and continuing into the Clinton era, the three agencies experienced a recovery and rise through the late 1990s tech bubble.

After peaking in FY 2003 at 0.083 percent of GDP, the three agencies have undergone a period of relative funding stagnation. Apart from the transient Recovery Act funding spike, agencies’ combined funding has wavered around 0.075% of GDP. Much of this stagnant is due to the discretionary caps under the Budget Control Act, which took effect beginning in FY 2012.

CHIPS and Science provided NIST mandatory funding specifically earmarked for semiconductor R&D and industry incentives but left the range of other technology priorities to be funded through annual discretionary appropriations, which as described have been limited. Under current appropriations, agency discretionary budgets would likely drop to near 0.07% of U.S. GDP, their lowest point in 25 years.

Government Shutdowns Are ‘Science Shutdowns’

Government shutdowns are “Science Shutdowns” – a wildly expensive and ineffective tactic that slows or stops scientific progress at the expense of everyday Americans.

Agencies are busy preparing contingency plans for a government shutdown as Congress spars for political points. FAS would like to draw attention to the danger and absurdity of this tactic as it relates to science, as well as our nation’s safety, competitiveness, and cost burden.

There are four (4) primary results of any government shutdown, and each affect science, which is why we refer to government shutdowns as “Science Shutdowns”:

1. Ongoing Experiments / Activities Requiring Ongoing Observation are Disrupted.

This isn’t just an aggravation to researchers; stoppage destroys work underway at considerable costs to the public. Some examples:

The Department of Commerce will cease operational activity related to most research activities at the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

During a shutdown, researcher access to certain federally funded user facilities and scientific infrastructure can be restricted. When this happens, it can mean lost experiments, disrupted projects, and missed opportunities for students and U.S. industry. (See: FAS work in Social Innovation, specifically STEM Education and Education R&D.)

The Department of Energy’s nuclear verification work––particularly work involving international partnerships––is likely to be restricted. This could have implications for U.S. leadership on non-proliferation, arms control, and risk reduction. (While Nuclear weapons deployments, security, and transportation operations would be largely unaffected due to national security exemptions and funding contingencies, this is still a dangerous situation. See: FAS’s work in Nuclear Weapons.)

2. New initiatives can’t continue (or begin).

Science and technology undergird a large percentage of entrepreneurial startups and economic clusters across the country. Stopping or slowing these businesses impact local communities of all sizes, in every state.

One example: Functionally all SBA (Small Business Administration) lending activity and program support will cease. Small businesses across the country will lose access to this critical source of financing. SBA lending is used to finance growth, but also (critically) to provide working capital for small businesses. Government shutdowns delay Tech Hubs and Engines Type 2 funding, disrupting ecosystem building efforts across the country (See: FAS work in Ecosystems and Entrepreneurship).

3. Funding Decisions are Halted and Delayed.

Shutdowns can mean funding agencies like the National Science Foundation and National Institute of Health (NIH) must furlough most of their staff. This results in delays and rescheduling of review panels, the people responsible for evaluating the effectiveness of a new medicine, for example. Stoppages ultimately delay award decisions and slow advances.

Such delays can affect thousands of American researchers and students and disrupt vital research in many crucial areas. One example limited by a shutdown pause is emerging research in the bioeconomy, a growing part of our global competitiveness. (See: FAS work in Science Policy and bioeconomy, specifically.)

4. Upgrades, Repairs, and Modernization of National Research Infrastructure at Labs and Universities are Frozen.

Labs across the country are continuously upgrading facilities to leverage the latest technology to remain competitive and secure. A government shutdown arrests this necessary work.

Bottom line: A government shutdown is a science shutdown; the decision to pull the plug on government funding incur steep costs on wind-down and re-start, and leads to massive general waste and disruption. We must work together to find resolutions that do not involve holding science hostage during a government shutdown.

The bold vision of the CHIPS and Science Act isn’t getting the funding it needs

Originally published May 17, 2023 in Brookings.

The legislative accomplishments of the previous session of Congress have given advocates of more robust innovation and industrial development investments much to be excited about. This is especially true for the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act (CHIPS), which committed the nation not just to compete with China over industrial policy and talent, but to advance broad national goals such as manufacturing productivity and economic inclusion while ramping up federal investment in science and technology.

Most notably, CHIPS authorized rising spending targets for key anchors of the nation’s innovation ecosystem, including the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). In that regard, the act’s passage was a breakthrough—including for an expanded focus on place-based industrial policy.

However, it’s become clear that this breakthrough is running into headwinds. In spite of ongoing rhetorical support for the act’s goals from many political leaders, neither the FY 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act nor the Biden administration’s FY 2024 budget request have delivered on the intended funding targets. This year’s omnibus funding remained nearly $3 billion short of the authorized levels for research agencies, while the 2024 budget request undershoots agency targets by over $5 billion. And with the debt ceiling crisis coming to a head this month—and House legislation on the table that would substantially roll back federal spending—it’s even harder to be optimistic about the odds of fulfilling the CHIPS and Science Act’s vision of resurgent investment in American competitiveness.

Instead, delivery on the CHIPS and Science Act paradigm can only be fractional as of now, with a $3 billion (and growing) funding gap for research and less than 10% of the five-year place-based vision funded to date.

All of which underscores how much work remains to be done if the nation is going to deliver on the promise of a rejuvenated innovation and place-based industrial strategy. Leaders need to make an energetic and bipartisan reassertion of the CHIPS vision without delay if the government is to truly follow through on its bold promises.

CHIPS has a broad, Innovative policy menu to support renewed American Competitiveness

Recently, Rep. Frank Lucas (R-Okla.), chair of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, rightly pointed out that the “science” portion of the CHIPS and Science Act (i.e., separate from its subsidies for semiconductor factories) will be “the engine of America’s economic development for decades to come.” One way the act seeks to achieve this is by creating the Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships at NSF, and focusing it on an evolving set of technological and social priorities (see Tables 1a + 1b). These won’t just drive NSF technology work, but will guide the development of a more concerted whole-of-government strategy.

| Table 1b: Societal, national, and geostrategic challenges | |

|---|---|

| U.S. national security | Climate change and sustainability |

| Manufacturing and industrial productivity | Inequitable access to education, opportunity, services |

| Workforce development and skill gaps | |

In light of these priorities, it’s no mistake that Congress placed the NSF, the Energy Department’s Office of Science, NIST, and the Economic Development Administration (EDA) at the core of the “science” portion of the act. The first three agencies are major funders of research and infrastructure for the physical science and engineering disciplines that undergird many of these technology areas. The EDA, meanwhile, is the primary home for place-based initiatives in economic development.

Meanwhile, in keeping with the larger strategy of countering the nation’s science and technology drift, Congress adopted five years of rising “authorizations” for these core innovation agencies. However, it bears remembering that these authorizations are not actual funding, but multiyear funding targets that, if fully funded year by year, would result in an aggregate budget doubling. In short, Congress has declared that the national budget for science and technology should go up, not down, over the next five years.

It’s also worth noting that the act seeks to boost investment in many different areas, including:

- Fundamental science and curiosity-driven research funded by science agencies at federal labs, universities, and companies.

- Use-inspired research, translation, and production to expand the ability of federal agencies to invest in emerging technology, enter partnerships, and drive manufacturing innovation.

- STEM education and workforce development to create or expand programs to foster opportunities and up-skilling.

- Research facilities and instrumentation at national labs and universities across the country, including modernization of aging research infrastructure.

- Regional innovation to broaden the nation’s innovation map.

The upshot: Supporters are not wrong in seeing the CHIPS and Science Act as a major moment of aspiration for U.S. innovation efforts and ecosystems.

Government Appropriations are falling short on CHIPS funding by billions of dollars

Yet for all the act’s valuable programs and focus areas, not all is well. As of now, there have been two rounds of proposed or adopted funding policy for CHIPS research agencies—and the results are mixed to disappointing as details a new funding update on the CHIPS and Science Act from the Federation of American Scientists.

The first funding round was the FY 2023 omnibus package Congress adopted last December. There, the aggregate appropriations for the NSF, Office of Science, and NIST amounted to $2.7 billion—a 12% shortfall below the aggregate FY 2023 target of $22.4 billion.

Table 2: Major research agency appropriations vs. CHIPS authorizations

| CHIPS FY23 Authorizations | FY23 Omnibus Appropriation* | Difference ($M) | Difference (%) | CHIPS FY24 Authorizations | FY24 OMB Budget | Difference ($M) | Difference (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Science Foundation | $11,897 | $9,874 | ($2,023) | -17.0% | $15,647 | $11,314 | ($4,333) | -27.7% |

| DOE Office of Science | $8,902 | $8,100 | ($802) | -9.0% | $9,542 | $8,800 | ($742) | -7.8% |

| National Institute of Standards & Technology | $1,551 | $1,654 | $103 | 6.6% | $1,652 | $1,632 | ($20) | -1.2% |

| Totals | $22,351 | $19,628 | ($2,723) | -12.2% | $26,840 | $21,746 | ($5,095) | -19.0% |

| Dollars in millions | *FY23 omnibus figures include NIST earmarks and supplemental NIST and NSF spending for CHIPS and Science activities | |||||||

Then, in March, amid what was already a yawning funding gap, the White House released its FY 2024 budget proposal. That proposal would have the three CHIPS research agencies falling further behind: $5.1 billion, or 19% below the act’s authorization.

In both the omnibus and the budget, NSF funding was the biggest miss. This can be divided into a few segments:

- Core research directorates. Most NSF science research is channeled through six research directorates that focus on biology, computing and information science, engineering, geoscience, math and computer science, or social science, alongside offices focused on multiple crosscutting activities. This research lays a foundation for innovative advances and funds several mechanisms for industrial research partnerships, roughly in line with the CHIPS and Science Act’s broader industrial innovation goals. Funding for these collective activities stood at about $591 million (8% below the authorized level) in FY 2023 and $846 million (10% below the authorized level) in the FY 2024 budget request.

- Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP). This new directorate established in CHIPS is meant to support translational, use-inspired, and solutions-oriented research and development through a variety of novel modes and models, including the NSF’s Regional Innovation Engines (more on these below), translation accelerators, entrepreneurial fellowships, and test beds. Authorizers set a TIP funding target of $1.5 billion in FY 2023 and $3.4 billion in FY 2024—the most ambitious CHIPS appropriations targets by far. However, actual funding was $620 million short in FY 2023 and $2.2 billion short in the FY 2024 budget request.

- STEM education. The NSF’s Directorate for STEM Education houses activities across K-12 education, tertiary education, informal learning settings, and outreach to underserved communities. CHIPS authorized boosts for multiple directorate programs, including Graduate Research Fellowships, Robert Noyce Teacher Scholarships, and CyberCorps Scholarships, while establishing new Centers for Transformative Education Research and Translation to conduct education research and development. Collectively, these STEM education activities fell $579 million short of their $1.4 billion authorized level in the FY 2023 omnibus, and $1.1 billion short in the FY 2024 budget request.

With these shortfalls at NSF and other agencies, it will be difficult for federal science and innovation programs to have the transformative impact that CHIPS envisioned.

Funding for place-based industrial policy programs is also coming up short

In addition to decreased agency support, actual funding for what we call the “place-based industrial policy” in the CHIPS and Science Act is also coming up short, by even greater relative margins. Where the agency research funding gaps are a substantial restraint on innovative capacity, the diminished place-based funding is an out-and-out emergency.

These programs are important because after years of uneven economic progress across places, CHIPS saw Congress finally accelerating large-scale, direct investments to unlock the innovation potential of underdeveloped places and regions. Thanks to some of those investments, including several new challenge grants, scores of state and local leaders across the country have thrown themselves headlong into the design of ambitious strategies for building their own innovation ecosystems.

Yet for all of the legitimate excitement and interest of stakeholders in literally every state, the numbers that permit actual implementation are not all good. Looking at several of the most visible new place-based programs, the funding news is so far mixed to outright disappointing.

- Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs: Authorized at $10 billion over five years, the program received just $500 million in the FY 2023 omnibus—one-quarter of its authorized level for the year. This has greatly limited the resources available to the EDA for “development” grants to build out the program’s 20 forecasted hubs. Currently, the EDA is planning to make only five to 10 much smaller development grants instead of the authorized 20 very large grants, with more uncertainty ahead. Meanwhile, a $4 billion request in the president’s FY 2024 budget for mandatory funding outside the normal appropriations process (as opposed to discretionary spending, which is funded through annual spending bills) faces long odds.

- Regional Innovation Engines: This NSF program received $200 million in FY 2023 appropriations, and would receive $300 million under the FY 2024 request. It was authorized somewhat differently than other CHIPS line items, receiving a joint $6.5 billion authorization over five years for the Engines along with NSF’s newly authorized Translation Accelerators program. If one counts $3.25 billion as the five-year Engines authorization, then the program has received only about 6% of its authorization so far, or 15% if it receives the FY 2024 request level.

- Distressed Area Recompete Pilot Program: This EDA program—designed to deliver grants to distressed communities to connect workers to good jobs—is a relative bright spot funding-wise. Authorized at $1 billion over the FY 2022 to FY 2026 period, the program received its full $200 million in FY 2023 and has secured the same amount in the FY 2024 request. With that said, the program could still be under threat if the debt ceiling face-off leads to spending cuts.

Table 3: Placed-based innovation authorized in CHIPS and Science Act

| Program | What It Does | CHIPS and Science Authorizations | Appropriation So Far | FY24 OMB Budget | Percent of Authorization Funded To Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDA Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs | Planning grants to be awarded to create regional technology hubs focusing on technology development, job creation, and innovation capacity across the U.S. | $10 billion over five years | $500 million | $48.5 million discretionary; $4 billion mandatory | 5% |

| EDA Recompete Pilot Program | Investments in communications with large prime age (25-54) employment gaps | $1 billion over five years | $200 million | $200 million | 20% |

| NSF Regional Innovation Engines | Up to 10 years of funding for each Engine (total ~$160 million per) to build a regional ecosystem that conducts translatable use-inspired research and workforce development | $3.25 billion* over five years | $200 million | $300 million | 6% |

| NIST Manufacturing Extension Partnership | A network of centers in all 50 states and Puerto Rico to help small and medium-sized manufacturers compete | $575 million | $188 million | $277 million | 68% |

| NIST Manufacturing USA | Program office for nationwide network of public-private manufacturing innovation institutes | $201 million | $51 million | $98 million | 53% |

| Totals (including MEP and M-USA FY23 authorizations) | $15 billion | $1.1 billion | 8% | ||

| * The NSF Regional Innovation Engines is assumed to have received 50% of a $6.5 billion CHIPS and Science Act provision that also authorized the Translation Accelerators program | |||||

Besides these new CHIPS programs, two established mainstays of place-based development in the manufacturing domain are also facing funding challenges.

- NIST Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership: This program was slated for sizable boosts, with a $275 million authorization in FY 2023 and $300 million in FY 2024. The FY 2023 appropriation ended up $87 million short, while the FY 2024 request seeks a degree of catch-up, to within $23 million of the authorization. The request would support the National Supply Chain Optimization and Intelligence Network, to be established in FY 2023, and expand workforce up-skilling, apprenticeships, and partnerships with historically Black colleges and universities, minority-serving institutions, and community colleges.

- NIST Manufacturing USA: This program received $51 million in FY 2023 (about half of what was authorized), while the FY 2024 request again gets closer to the authorization, at $98 million. In FY 2024, NIST seeks to establish Manufacturing USA test beds, support a new NIST-sponsored institute to be completed in FY 2023, and further assist small manufacturers with prototyping and scaling of new technologies. As with all FY 2024 initiatives, outcomes depend partly on how tough the debt ceiling deal is for annual appropriations.

Overall, the current and likely future funding shortfalls facing many of the nation’s authorized place-based investments appear set to diminish the reach of these programs.

Should funding for critical technology areas be mandatory?

The CHIPS and Science Act establishes a compelling vision for U.S. innovation and place-based industrial policy, but that vision is already being hampered by tight funding. And now, the looming debt ceiling crisis is only going to make the situation worse.

Nor are there any silver bullets to resolve the situation. Somehow, Congress has to keep in sight the long-term vision for U.S. economic and military security, and find the political will to make the near-term financial commitments necessary for U.S. innovators, firms, and regions.

But it’s not just up to Congress. As we’ve seen, the White House budget also contains sizable funding shortfalls for research agencies. Federal agencies and the Office of Management and Budget will be formulating their FY 2025 budgets this summer in preparation for release next year. As they do so, they should prioritize long-term U.S. competitiveness across strategic technology areas and geographies more so than they have to date.

Lastly, while the mandatory spending proposal mentioned above for the Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs program may not get anywhere this year, mandatory funding as a mechanism for science and innovation investment is not a bad idea in principle. Nor is this the first time policymakers have pitched such an idea: The Obama administration attempted to make aggressive use of mandatory spending to supplement its base research and development requests, and congressional leaders have also floated the idea in recent years. Given the long-term nature of science and innovation, sustained and predictable support would be a boon, and a mandatory funding stream could provide much-needed stability.

Given all this, the moment may be approaching try again to leverage mandatory funding of innovation programs. With caps on discretionary spending on the horizon but bipartisan support for the CHIPS technology agenda still in place, the time to consider a mandatory funding measure may have arrived. Such a measure—structured by, say, a “Critical Technology and National Security Fund”—would go a long way toward ensuring more sustained, stable support for critical technologies in economic and military security. This is exactly the kind of support that CHIPS provides for the semiconductor industry, which is far from the only advanced technology sector subject to global competition.

In short, as we enter the summer months and face down a looming budget crisis, Congress should do for the “science” part of its watershed bill what it did with the “chips” part. Leaders in Washington must move now to ensure that we can deliver on the commitments set forth in the CHIPS and Science Act—all of them.

CHIPS and Science Funding Update: FY 2023 Omnibus, FY 2024 Budget Both Short by Billions

See PDF for more charts.