DIA Estimates For Chinese Nuclear Warheads

During a Hudson Institute conference on Russian and Chinese nuclear modernizations, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lt. Gen. Robert Ashley said in prepared remarks: “Over the next decade, China is likely to at least double the size of its nuclear stockpile…”

This projection is new and significantly above recent public statements by US government agencies. But how reliable is it and how have US agencies performed in the past?

The public record is limited because estimates are normally classified and agencies and officials are reluctant to say too much. But a few examples exist from declassified documents and public statements. These estimates vary considerably – some seemed downright crazy.

But before analyzing DIA’s projection for the future, let’s examine what the estimated Chinese nuclear stockpile looks like today.

Current Chinese Stockpile Estimate

While warning the Chinese stockpile will “at least double” over the next decade, Lt. Gen. Ashley’s prepared remarks did not say what it is today. But in the follow-up Q/A session, he added: “We estimate…the number of warheads the Chinese have is in the low couple of hundreds.

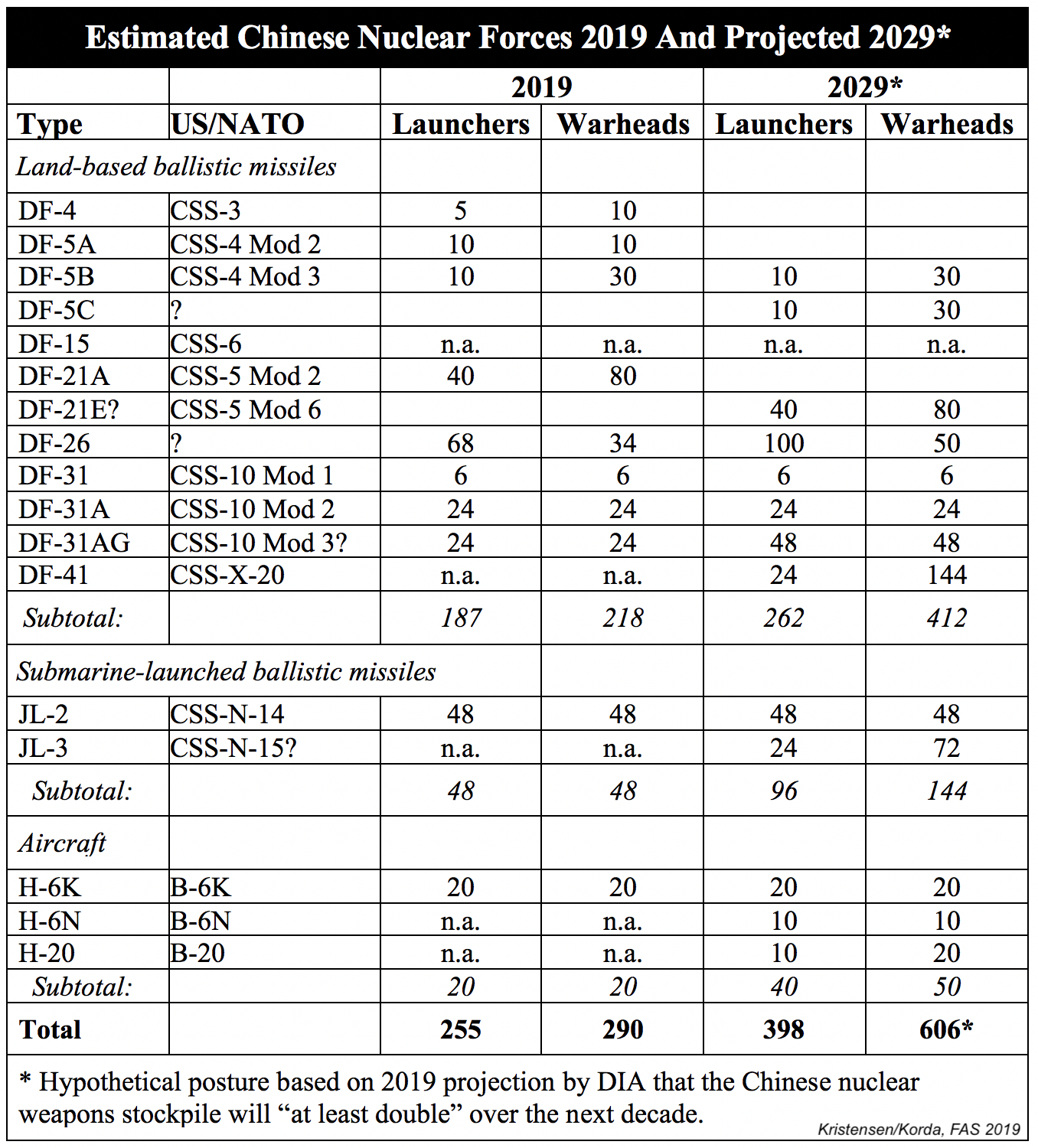

That estimate is close to statements made by DOD and STRATCOM nearly a decade ago. In our forthcoming Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces (scheduled for publication in July 2019), we estimate the Chinese stockpile now includes approximately 290 warheads and is likely to surpass the size of the French nuclear stockpile (~300 warheads) in the near future.

Earlier Chinese Stockpile Estimates

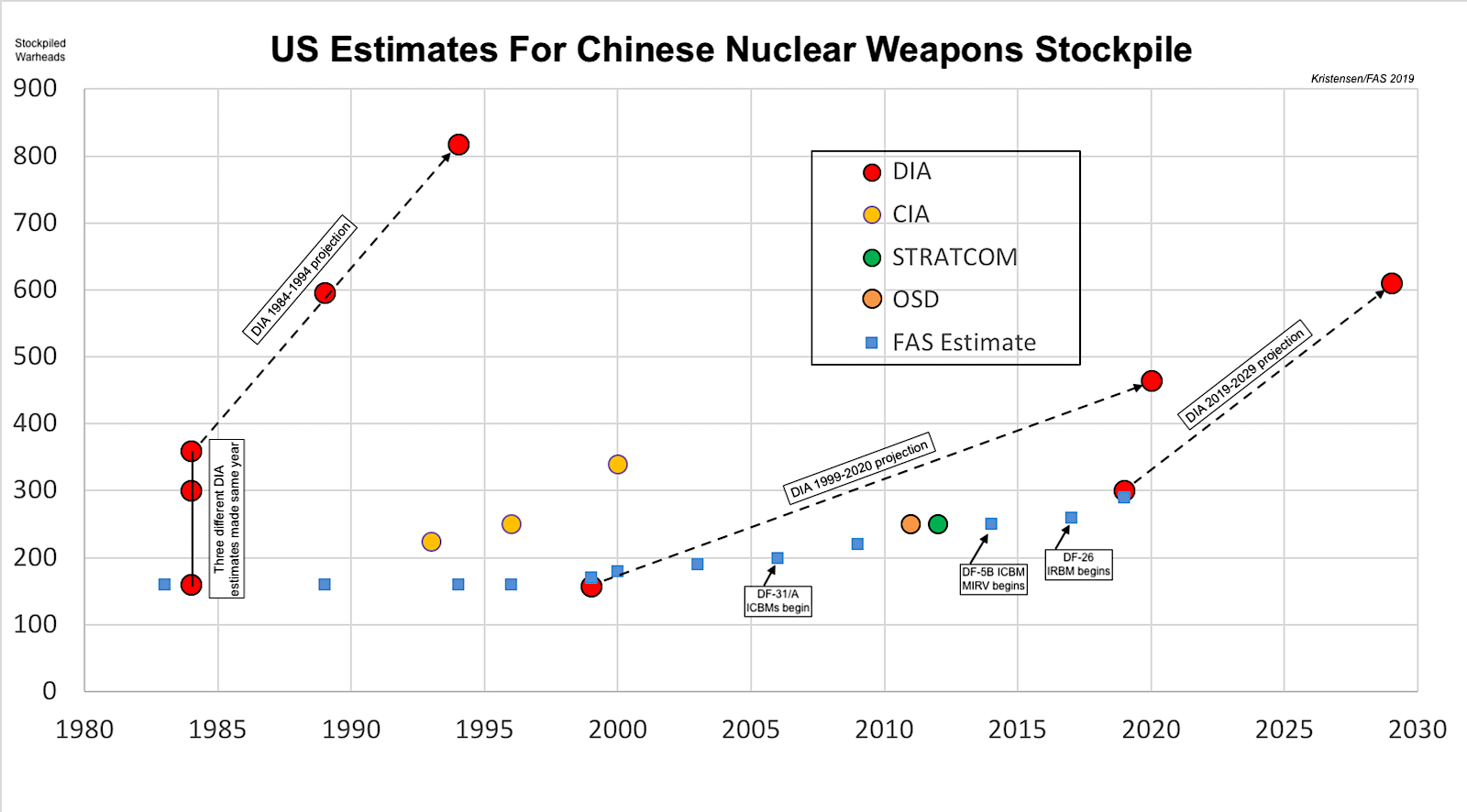

Earlier projections made by US agencies of China’s nuclear stockpile have varied considerably. DIA’s estimates have consistently been higher – even extraordinarily so – than that of other agencies (see graph below). The wide range reflects an enormous uncertainty and lack of solid intelligence, which makes it even more curious why DIA would make them. This record obviously raises questions about DIA’s latest projection.

In April 1980s, for example, DIA published a Defense Estimate Brief with the title: Nuclear Weapons Systems in China. The brief, which was prepared by the China/Far East Division of the Directorate for Estimates and approved by DIA’s deputy assistant director for estimates, projected an astounding growth for China’s nuclear arsenal that included everything from ICBMs, MRBMs, SRBMs, bombs, landmines, and air-to-surface missiles. The brief concluded a curious double estimate of 150-160 warheads in the text and 360 warheads in a table and projected an increase from 596 warheads in 1989 to as many as 818 by 1994. The brief was partially redacted for many years but it has since been possible to reconstruct in its entirety because of inconsistencies in the processing of different FOIA requests.

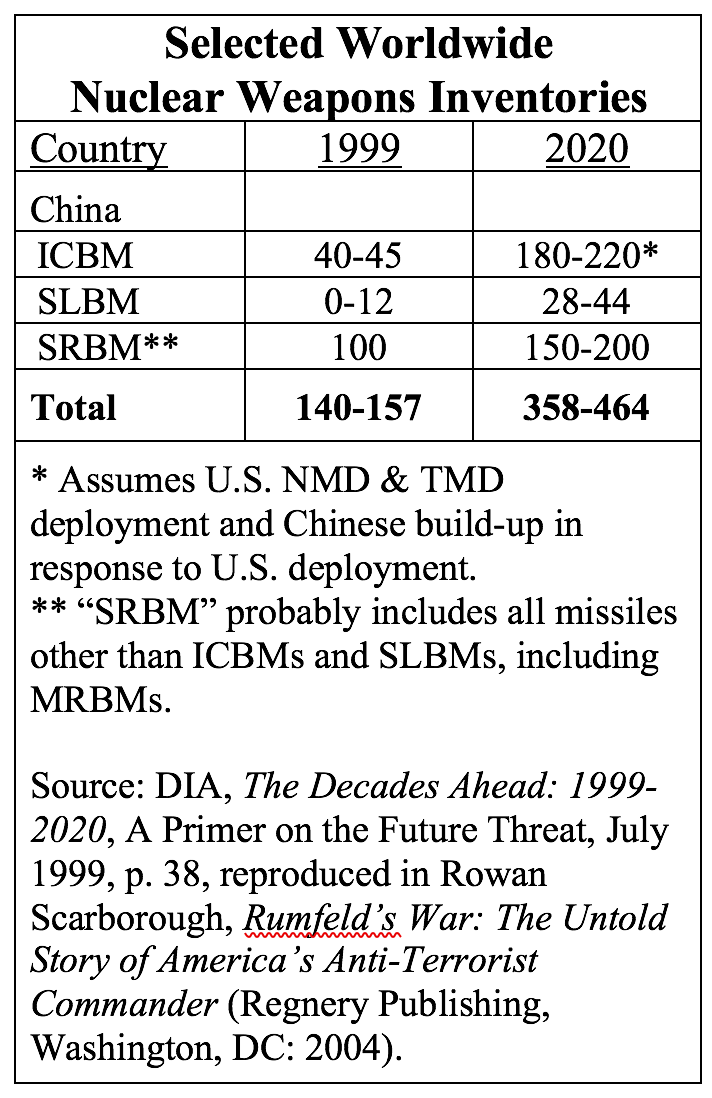

In the 1990s, CIA published three estimates, all significantly lower than the DIA projection from 1984. But DIA apparently was reworking its methodology because in 1999 it published A Primer On The Future Threat that was lower than the CIA estimate but projected an increase of the Chinese stockpile from 140-157 warheads to 358-464 warheads in 2020. The Primer predicted that deployment of US missile defenses would cause China to significantly increase its ICBM force, a prediction that has come through to some extent and is now ironically used by DIA and others to warn of a growing Chinese nuclear threat against the United States.

In the 1990s, CIA published three estimates, all significantly lower than the DIA projection from 1984. But DIA apparently was reworking its methodology because in 1999 it published A Primer On The Future Threat that was lower than the CIA estimate but projected an increase of the Chinese stockpile from 140-157 warheads to 358-464 warheads in 2020. The Primer predicted that deployment of US missile defenses would cause China to significantly increase its ICBM force, a prediction that has come through to some extent and is now ironically used by DIA and others to warn of a growing Chinese nuclear threat against the United States.

Following an intense debate in 2010 about Senate approval of the New START treaty, then-principle deputy undersecretary of defense for policy James Miller told Congress in 2011: “China is estimated to have only a few hundred nuclear weapons….”

And when false rumors flared up in 2012 that China had hundreds – even thousands – of warheads more than commonly assumed, STRATCOM commander Gen Kehler rebutted the speculations saying: “I do not believe that China has hundreds or thousands more nuclear weapons than what the intelligence community has been saying,” which is “that the Chinese arsenal is in the range of several hundred” nuclear warheads.

Since then, China has started to deploy the modified silo-based DF-5B ICBM that is equipped with multiple warheads (MIRV) – part of the response to the US missile defenses that DIA predicted in 1999, and deployed a significant number of dual-capable DF-26 IRBMs. Even so, Ashley’s most recent statement roughly matches the estimates made by Miller and Kehler nearly a decade ago, when he says: “We estimate…the number of warheads the Chinese have is in the low couple of hundreds.”

How Could The Chinese Stockpile More Than Double?

Although Ashley predicted a significant expansion of the Chinese stockpile, he did not explain the assumptions that go into that assessment. What would China have to do in order to more than double its stockpile over the next decade?

There are several potential options. China could field a significant number of additional launchers, or deploy significantly more MIRVs on some of its missiles, or – if the MIRV increase is less dramatic – a combination of more launchers and more MIRV. It seems likely to be the latter option.

Additional MIRVing seems to be an important factor. China is developing the road-mobile DF-41 ICBM that is said to be capable of carrying MIRV. It is also developing a third modification of the silo-based DF-5 (DF-5C) that may have additional MIRV capability compared with the current DF-5B. Finally, the next-generational JL-3 SLBM could potentially have MIRV capability, although I have yet to see solid sources saying so. There are many rumors about up to 10 MIRV per DF-41 (even unreliable rumors about MIRV on shorter-range systems), but if China’s decision to MIRV is a response to US missile defenses (which DIA and DOD have stated for years), then it seems more likely that the number of warheads on each missile is low and the extra spaces used for decoys.

China is also expanding its SSBN fleet, which could potentially double in size over the next decade if the production of the next-generation Type-096 gets underway in the early-2020s. And China reportedly has reassigned a nuclear mission to its bombers, is developing a new nuclear-capable bomber, and an air-launched ballistic missile that might have a nuclear option. Assuming a few bomber squadrons would a nuclear capability by the late-2020s, that could help explain DIA’s projection as well. Altogether, that adds up to a hypothetical arsenal that could potentially look like this in order to “at least double” the size of the stockpile:

Conclusions

Whether DIA’s projection comes through of a Chinese stockpile “at least double” the size of the current inventory remains to be seen. Given DIA’s record of worst-case predictions, there are good reasons to be skeptical. It would, at a minimum, be good to hear what the coordinated Intelligence Community assessment is. Does the Director of National Intelligence agree with this projection?

That said, the Chinese leadership has obviously decided that its “minimum deterrent” requires more weapons. To that end, the debate over how much is enough, what the Chinese intentions are, and what the US response should be, are important reminders that the Chinese leadership needs to be more transparent about what its modernization plans are. Lack of basic information from China fuels worst-case assumptions in the United States that can (and will) be used to justify defense programs that increase the threat against China. The recommendation by the Nuclear Posture Review to develop a new nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile is but one example. Both sides have an interest in limiting this action-reaction cycle.

Even if DIA’s projection of a more than doubling of the Chinse stockpile were to happen, that would still not bring the inventory anywhere near the size of the US or Russian stockpiles. They are currently estimated at 4,330 and 3,800 warheads, respectively – even more, if counting retired, but still largely intact, warheads awaiting dismantlement.

But despite the much smaller Chinese arsenal, a significant expansion of the stockpile would likely make US and Russia even more reluctant to reduce their arsenals – a reduction the Chinese government insists is necessary first before it will join a future nuclear arms limitation agreement. So while China’s motivation for increasing its arsenal may be to reduce the vulnerability of its deterrent, it may in fact also cause the United States and Russian to retain larger arsenals than otherwise and even increase their capabilities to threaten China.

Whether DIA’s projection pans out or not, it is an important reminder of the increasingly dynamic nuclear competition that is in full swing between the large nuclear weapons states. The pace and scope of that competition are intensifying in ways that will diminish security and increase risks for all sides. Strengthening deterrence is not always beneficial and even smaller arsenals can have significant effects.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Pentagon Slams Door On Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Transparency

The Pentagon has decided not to disclose the current number of nuclear weapons in the Defense Department’s nuclear weapons stockpile. The decision, which came as a denial of a request from FAS’s Steven Aftergood for declassification of the 2018 nuclear weapons stockpile number, reverses the U.S. practice from the past nine years and represents an unnecessary and counterproductive reversal of nuclear policy.

The United States in 2010 for the first time declassified the entire history of its nuclear weapons stockpile size, a decision that has since been used by officials to support U.S. non-proliferation policy by demonstrating U.S. adherence to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), providing transparency about U.S. nuclear weapons policy, counter false rumors about secretly building up its nuclear arsenal, and to encourage other nuclear-armed states to be more transparent about their arsenals.

Importantly, the U.S. also disclosed the number of warheads dismantled each year back to 1994. This disclosure helped document that the United States was not hiding retired weapons but actually dismantling them. In 2014, the United States even declassified the total inventory of retired warheads still awaiting dismantlement at that time: 2,500.

The 2010 release built on previous disclosures, most importantly the Department of Energy’s declassification decisions in 1996, which included – among other issues – a table of nuclear weapons stockpile data with information about stockpile numbers, megatonnage, builds, retirements, and disassemblies between 1945 and 1994. Unfortunately, the web site is poorly maintained and the original page headlined “Declassification of Certain Characteristics of the United States Nuclear Weapon Stockpile” no longer has tables, another page is corrupted, but the raw data is still available here. Clearly, DOE should fix the site.

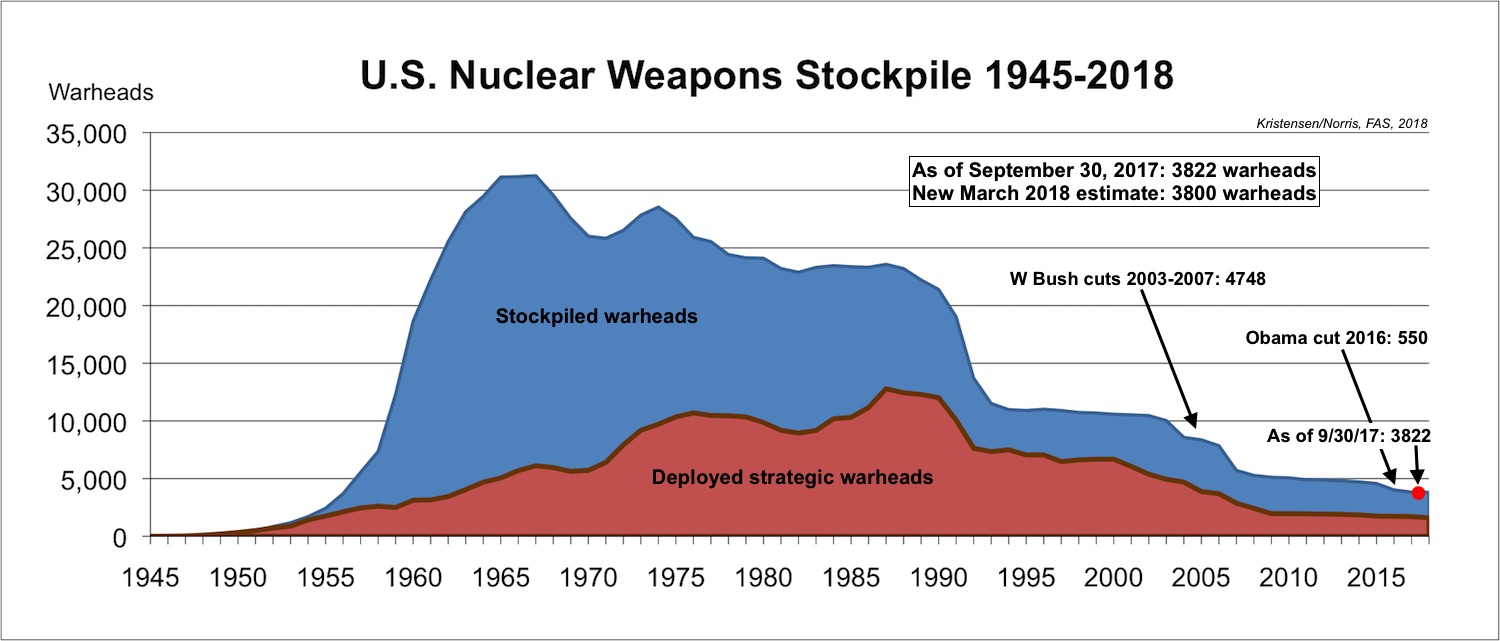

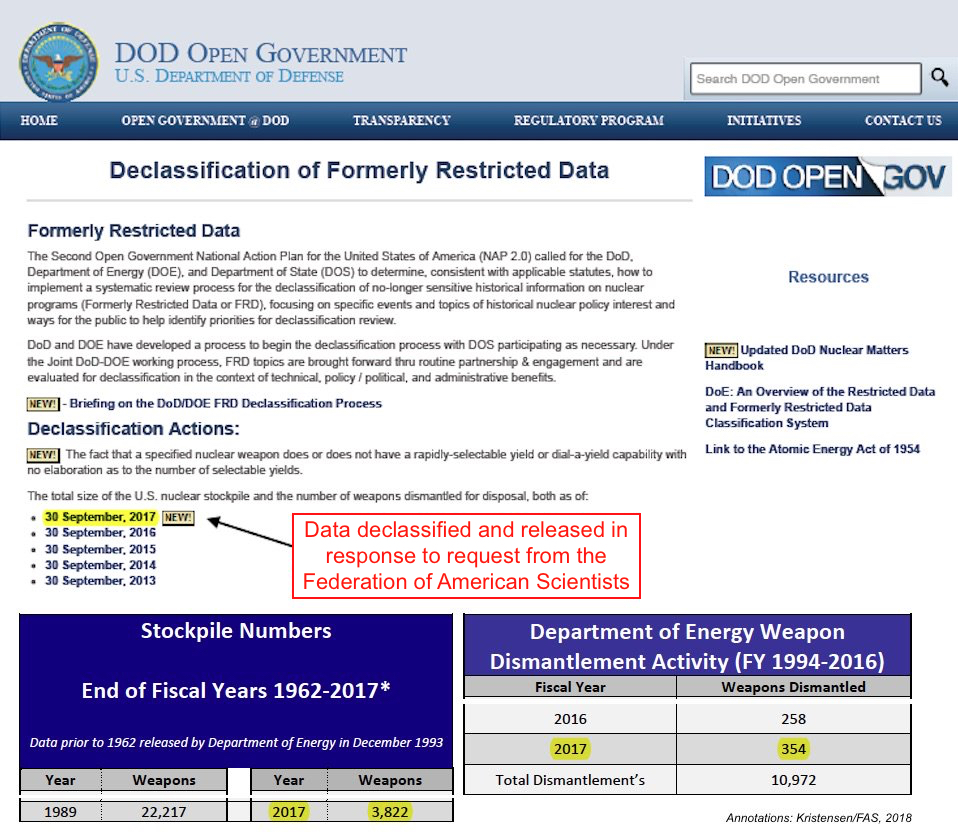

The decision in 2010 to disclose the size of the stockpile and the dismantlement numbers did not mean the numbers would necessarily be updated each subsequent year. Each year was a separate declassification decision that was announced on the DOD Open Government web site. The most recent decision from 2018 in response to a request from FAS showed the stockpile number as of September 2017: 3,822 stockpiled warheads and 354 dismantled warheads.

The 2017 number was extra good news because it showed the Trump administration, despite bombastic rhetoric from the president, had continued to reduce the size of the stockpile (see my analysis from 2018).

Since 2010, Britain and France have both followed the U.S. example by providing additional information about the size of their arsenals, although they have yet to disclose the entire history of their warhead inventories. Russia, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea have not yet provided information about the size or history of their arsenals.

FAS’ Role In Providing Nuclear Transparency

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has been tracking nuclear arsenals for many years, previously in collaboration with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). The 5,113-warhead stockpile number declassified by the Obama administration in 2010 was only 13 warheads off the FAS/NRDC estimate at the time.

We provide these estimates on our web site, on our Strategic Security Blog, and in publications such as the bi-monthly Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and the annual nuclear forces chapter in the SIPRI Yearbook. The work is used extensively by journalists, NGOs, scholars, parliamentarians, and government officials.

With the Pentagon decision to close the books on the stockpile, and the rampant nuclear modernization underway worldwide, the role of FAS and others in documenting the status of nuclear forces will be even more important.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The Pentagon’s decision not to disclose the 2018 nuclear weapons stockpiled and dismantled warhead numbers is unnecessary and counterproductive.

The United States or its allies are not suffering or at a disadvantage because the nuclear stockpile numbers are in the public. Indeed, there seems to be no rational national security factor that justifies the decision to reinstate nuclear stockpile secrecy.

The decision walks back nearly a decade of U.S. nuclear weapons transparency policy – in fact, longer if including stockpile transparency initiatives in the late-1990s – and places the United States is the same box as over-secretive nuclear-armed states, several of which are U.S. adversaries.

The decision also puts the United States in an even more disadvantageous position for next year’s nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) review conference where the administration will be unable to report progress on meeting its Article VI obligations. Instead, this decision, as well as decisions to withdraw from the INF treaty, start producing new nuclear weapons, and the absence of nuclear arms control negotiations, needlessly open up the United States to criticism from other Parties to the NPT – a treaty the United States needs to protect and strengthen to curtail nuclear proliferation.

The decision also puts U.S. allies like Britain and France in the awkward position of having to reconsider their nuclear transparency policies as well or be seen to be out of sync with their largest military ally at a time of increased East-West hostilities.

With this decision, the Trump administration surrenders any pressure on other nuclear-armed states to be more transparent about the size of their nuclear weapon stockpiles. This is curious since the Trump administration had repeatedly complained about secrecy in the Russian and Chinese arsenals. Instead, it now appears to endorse their secrecy.

The decision will undoubtedly fuel suspicion and worst-case mindsets in adversarial countries. Russia will now likely argue that not only has the United States obscured conversion of nuclear launchers under the New START treaty, it has now decided also to keep secret the number of nuclear warheads it has available for them.

Finally, the decision also makes it harder to envision achieving new arms control agreements with Russia and China to curtail their nuclear arsenals. After all, if the United States is not willing to maintain transparency of its warhead inventory, why should they disclose theirs?

It is yet unclear why the decision not to disclose the 2018 stockpile number was made. There are several possibilities:

- Is it because the chaos and incompetence in the Trump administration have enabled hardliners and secrecy zealots to reverse a policy they disagreed with anyway?

- Is it a result of the Nuclear Posture Review’s embrace of Great Power Competition with Cold War-like instincts to increase reliance on nuclear weapons, kill arms control treaties, increase secrecy, and scuttle policies that some say appease adversaries?

- Is it because of a Trump administration mindset opposing anything created by president Obama?

- Or is it because the United States has secretly begun to increase the size of its nuclear stockpile? (I don’t think so; the stockpile appears to have continued to decrease to now at or just below 3,800 warheads.)

The answer may be as simple as “because it can” with no opposition from the White House. Whatever the reason, the decision to reinstate stockpile secrecy caps a startling and rapid transformation of U.S. nuclear policy. Within just a little over two years, the United States under the chaotic and disastrous policies of the Trump administration has gone from promoting nuclear transparency, arms control, and nuclear constraint to increasing nuclear secrecy, abandoning arms control agreements, producing new nuclear weapons, and increasing reliance on such weapons in the name of Great Power Competition.

This is a historic policy reversal by any standard and one that demands the utmost effort on the part of Congress and the 2020 presidential election candidates to prevent the United States from essentially going nuclear rogue but return it to a more constructive nuclear weapons policy.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

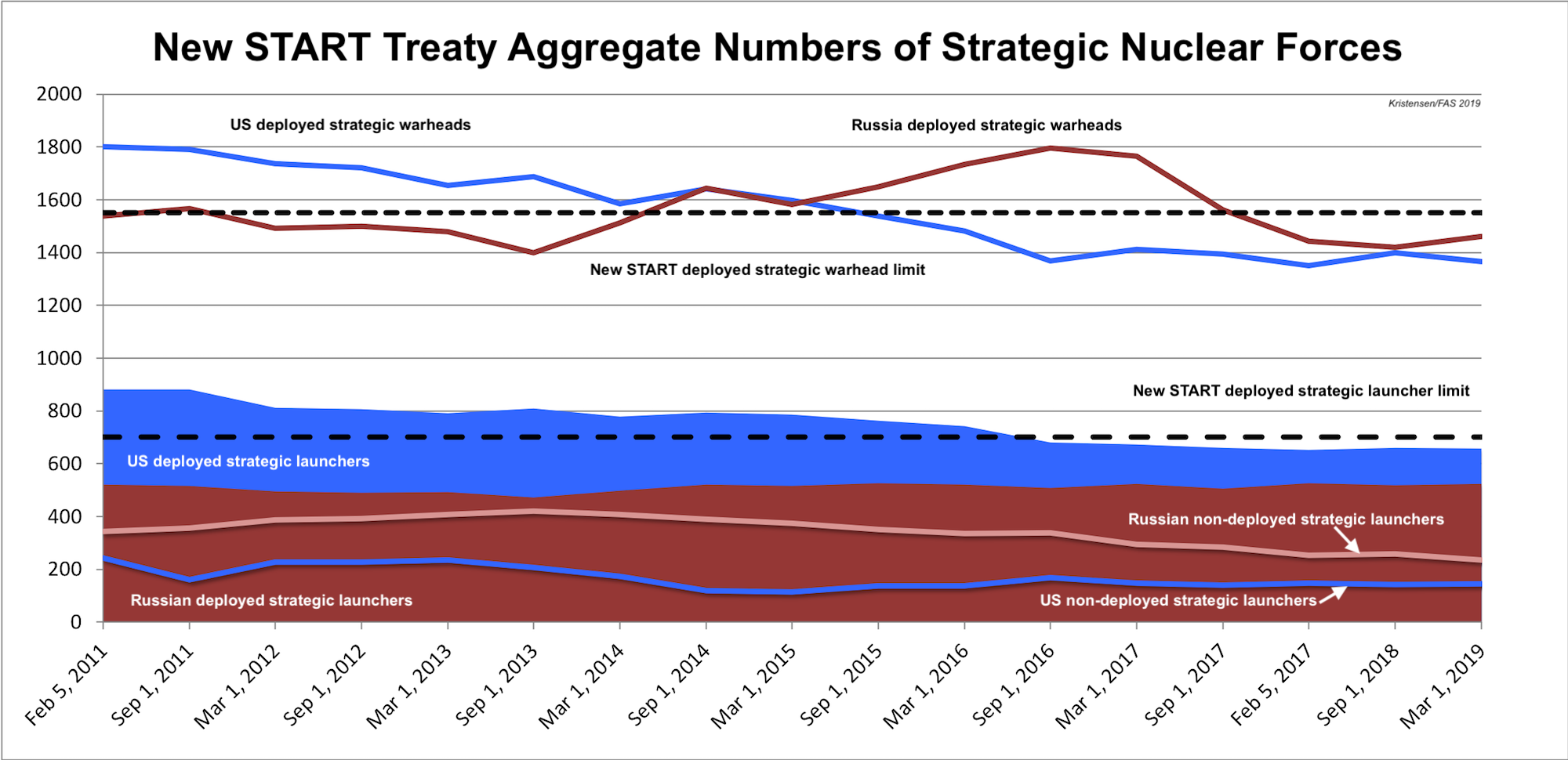

Despite Obfuscations, New START Data Shows Continued Value Of Treaty

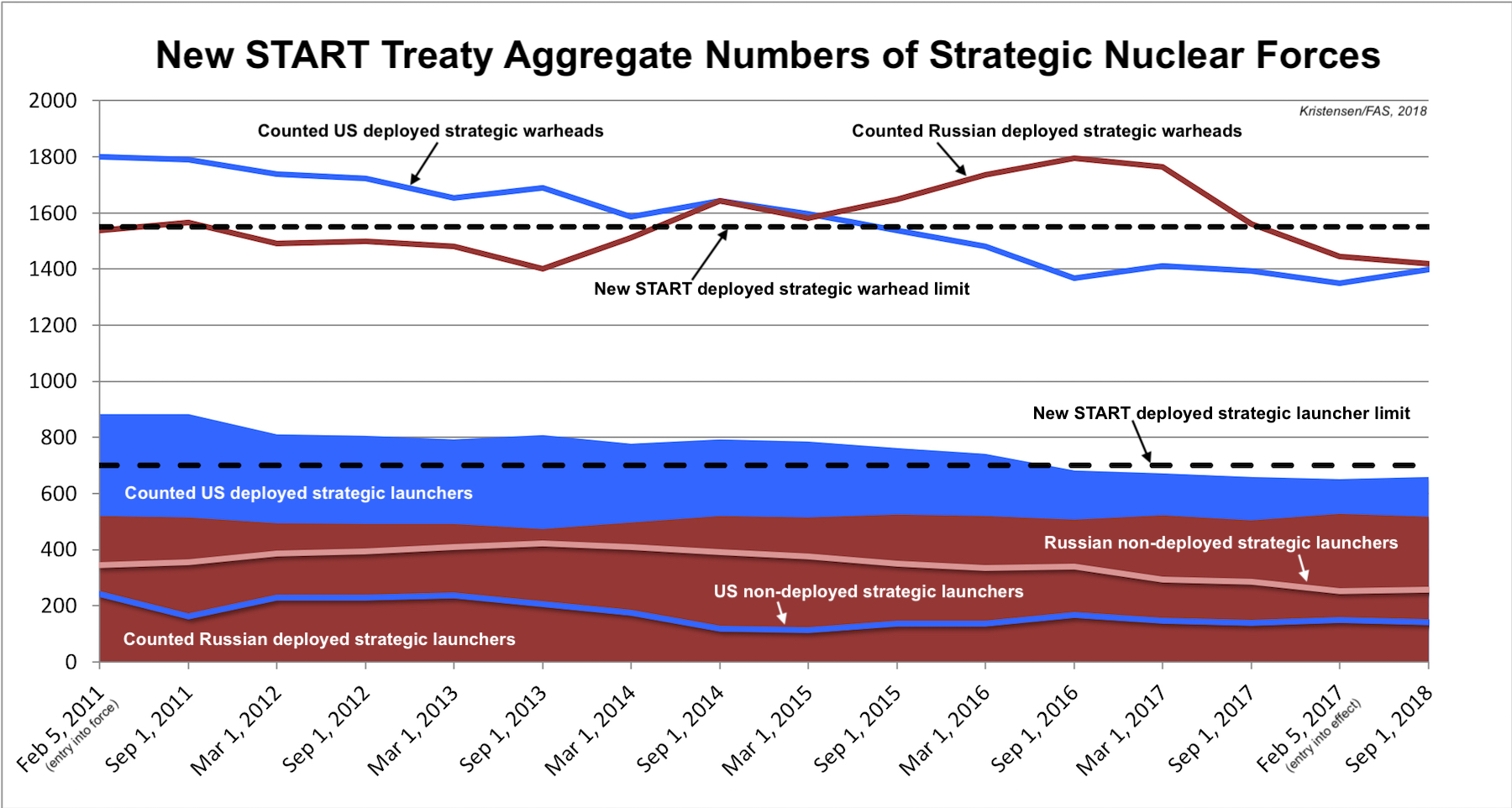

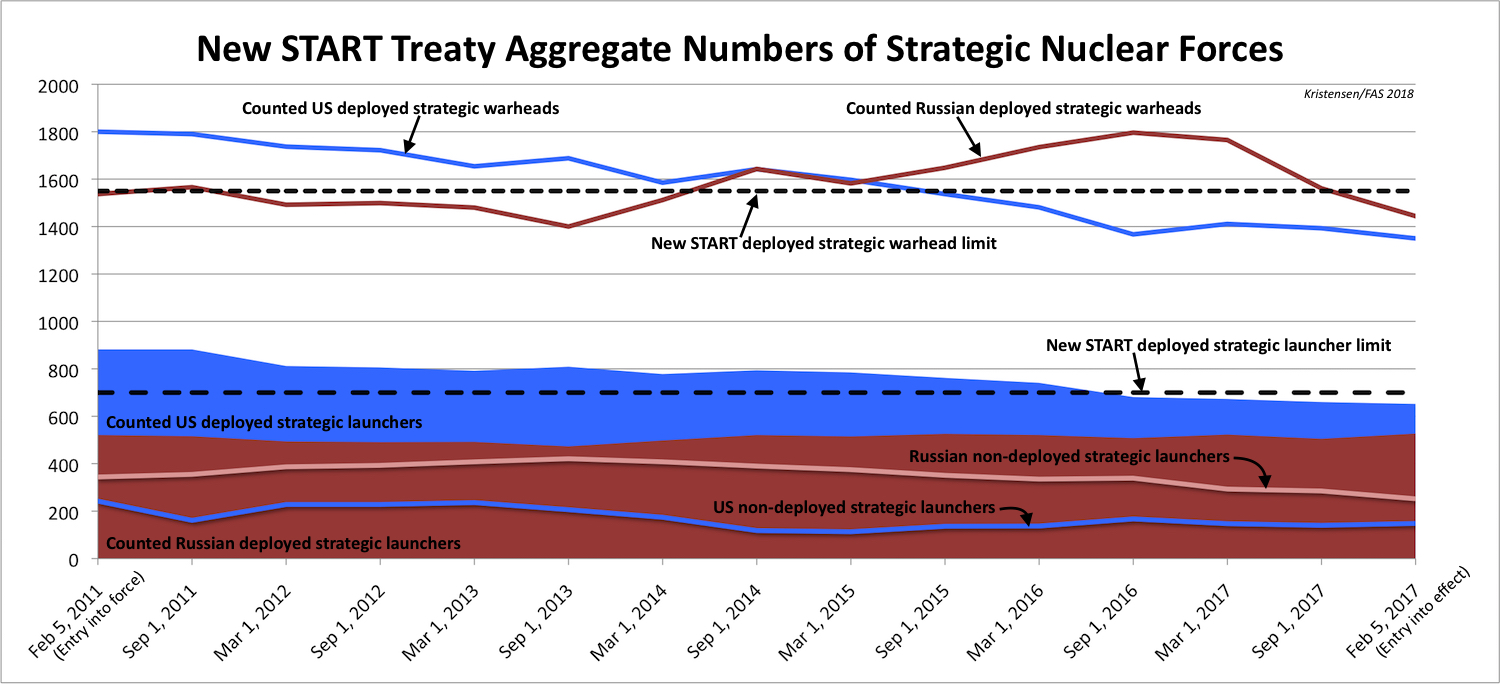

The latest set of New START treaty aggregate data released by the US State Department shows Russia and the United States continue to abide by the limitations of the New START treaty. The data shows that Russia and the United States combined have cut a total of 429 strategic launchers since February 2011, reduced the number of deployed launchers by 223, and reduced the number of warheads attributed to those launchers by 511.

The good news comes despite efforts by officials in Moscow and Washington to create doubts about the value of New START by complaining about lack of irreversibility, weapon systems not covered by the treaty, or other unrelated treaty compliance and behavioral matters. These complaints are part of the ongoing bickering between Russia and the United States and appear intended – they certainly have that effect – to create doubt about the value of extending New START for five years beyond 2021.

Playing politics with New START is irresponsible and counterproductive. While the treaty has facilitated coordinated and verifiable reductions and provides for on-site inspections and a continuous exchange of notifications about strategic offensive nuclear forces, the remaining arsenals are large, undergoing extensive modernizations, and demand continued limits and verification.

By the Numbers

The latest New START data shows that the United States and Russia combined, as of March 1st, 2019, deployed a total of 1,180 strategic launchers (long-range ballistic missiles and heavy bombers) with a total of 2,826 warheads attributed to them (see chart below). These two arsenals constitute more strategic launchers and warheads than all the world’s other seven nuclear-armed states possess combined.

For Russia, the data shows 524 deployed strategic launchers with 1,461 warheads. That’s a slight increase of 7 launchers and 41 warheads compared with September 2018. Russia is currently 176 launchers and 89 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

The United States deploys 656 strategic launchers with 1,365 warheads attributed to them, or a slight decrease of 3 launchers and 33 warheads compared with September 2018. The United States is currently 44 launchers and 185 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

These increases and decreases since September 2018 are normal fluctuations in the arsenals due to maintenance and upgrades and do not reflect an increase or decrease of the threat level.

It is important to remind, that the Russian and US nuclear forces reported under New START are only a portion of their total stockpiles of nuclear weapons, currently estimated at 4,350 for Russia and 3,800 for the United States (6,850 and 6,460, respectively, if also counting retired warheads awaiting dismantlement).

Build-Up, What Build-Up

Despite frequent claims by some about a Russian nuclear “buildup,” the New START data does not show such a development. On the contrary, it shows that Russia’s strategic offensive nuclear force level – despite ongoing modernization – is relatively steady. Deteriorating relations have so far not caused Russia (or the United States) to increase strategic force levels or slowed down the reductions required by New START. On the contrary, both sides seem to be continuing to structure their central strategic nuclear forces in accordance with the treaty’s limitations and intentions.

That said, both countries are working on modifications to their strategic nuclear arsenals. Russia has been working for a long time – even before New START was signed – to develop exotic intercontinental-range weapons to overcome US ballistic missile defense systems. These exotic weapons, which are not deployed or covered by the treaty, include a ground-launched nuclear-powered cruise missile (Burevestnik) and a submarine-launched torpedo-like drone (Poseidon). An ICBM-launched glide-vehicle commonly known as Avangard is close to initial deployment but would likely supplement the current ICBM force rather than increasing it. The new weapons are limited in numbers and insufficient to change the overall strategic balance or challenge extension of New START. The treaty provides for adding new weapon types if agreed by the two parties, although neither side has formally proposed to do so.

Russia is not at an advantage in terms of overall strategic nuclear forces, nor does it appear to try to close the significant gap the New START data shows exists in the number of strategic launchers – 132 in US favor by the latest count. To put things in perspective, 132 launchers is nearly the equivalent of a US ICBM wing, more than six Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, or twice the size of the entire US nuclear bomber fleet. If the tables were turned, US officials and hardliners would be screaming about a disadvantage. Astoundingly, some are still trying to make that case despite the US advantage. Given the launcher asymmetry, one could also suspect that Russia might seek to retain more non-deployed launchers for potential redeployment to be able to rapidly increase the force if necessary. Instead, the New START data shows that Russia has continued to decrease its non-deployed launchers by 185 since the peak of 421 in 2013.

Russian strategic modernization has been slower than expected with delays and less elaborate base upgrades and is stymied by a weak economy and corruption in government and defense industry. Russia is compensating for this asymmetry by maximizing warhead loadings on its new missiles, but the New START data indicates that Russia since 2016 has been forced to reduce the normal warhead loading on some of its ballistic missiles in order to meet the treaty limit for deployed warheads. This demonstrates New START has a real constraining effect on Russian strategic forces.

Having said that, Russia could – like the United States – upload large numbers of non-deployed nuclear warheads onto deployed launchers if a decision was made to break out of the New START limits. Those launchers would include initially bombers, then sea-launched ballistic missiles, and in the longer term the ICBMs.

The United States has dismantled and converted more launchers than Russia because the United States had more of them when the treaty was signed, not because Washington was handed a “bad deal,’ as some defense hardliners have claimed. But Russia has complained – including in an unprecedented letter to the US Congress – that it is unable to verify that launchers converted by the US can’t be returned to nuclear use. The New START treaty does not require irreversibility and the US insists conversions have been carried out as required by the treaty rules that Russia agreed to. Discussions continue in Bilateral Consultative Committee (BCC).

Verification and Notifications

Although not included in the formal aggregate data, the State Department has also disclosed the total number of inspections and notifications conducted under the treaty. Since February 2011, this has included 294 onsite inspections (3 each since September) and 17,516 notifications (up about 1,100 since September 2018). This data flow is essential to providing confidence and reassurance that the strategic force level of the other side indeed is what they say it is. It also provides each side invaluable insight into structural and operational matters that complements and expands what is possible to ascertain with national technical means.

US SSBN in drydock. Russia says it cannot verify conversion of US strategic launchers. Click on image to see full size.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Although bureaucrats and Cold Warriors in both Washington and Moscow currently are busy raising complaints and uncertainties about the New START treaty, there is no way around the basic fact: the treaty is strongly in the national security interest of both countries – as well as that of their allies.

But the treaty expires in February 2021 and the two sides could – if their leadership was willing to act – extend it with the stroke of a pen.

Unfortunately, Russian claims that it is incapable of confirming US conversion of strategic launchers, US complaints that new exotic Russian weapons circumvent the treaty, Russia’s violation and the US decision to withdraw from the INF treaty, as well as the growing political animosity and bickering between East and West, have combined to increase the pressure on New START and put extension in doubt.

The idea that the INF debacle somehow requires a reevaluation of the value of New START is ridiculous. INF regulates regional land-based missiles whereas New START regulates the core strategic nuclear forces. Why would anyone in either country in their right mind jeopardize limits and verification of strategic forces that threaten the survival of the nation over a disagreement about regional forces that cannot? That seems to be the epidemy of irresponsible behavior.

And the disagreements about conversion of launchers and need to add new intercontinental forces to the treaty can and should be resolved within the BCC.

But it all captures well the danger of Cold War mindsets where nationalistic bravado and chest-thumping override deliberate rational strategy for the benefit of national and international security. Bad times are not an excuse for sacrificing treaties but reminders of the importance of preserving them. Arms limitation treaties are not made with friends (you don’t have to) but with potential adversaries in order to limit their offensive nuclear forces and increase transparency and verification. If officials focus on complaining and listing problems, well guess what, that’s what we’re going to get.

Additional information:

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Chinese DF-26 Missile Launchers Deploy To New Missile Training Area

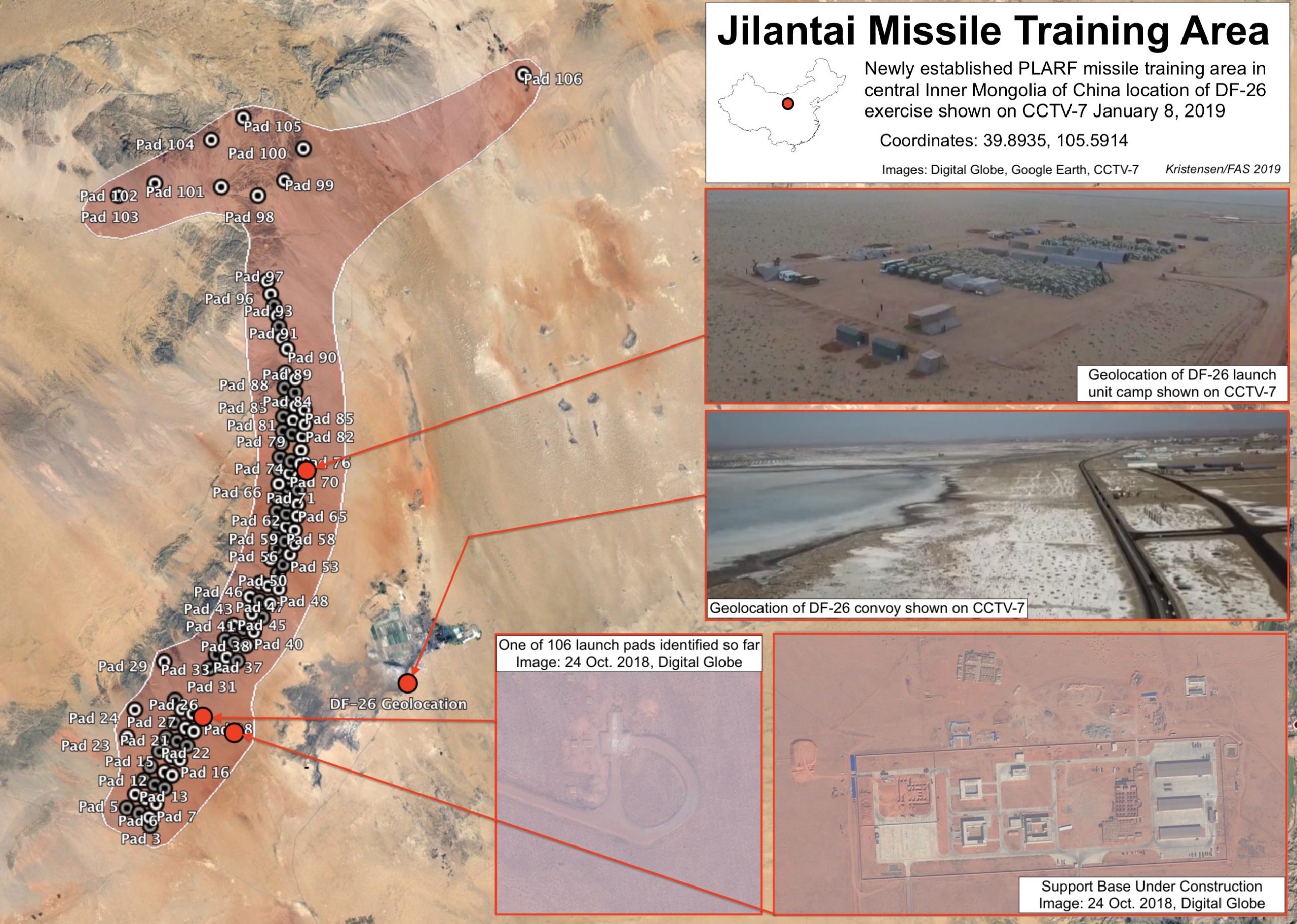

[Updated Jan 31, 2019] Earlier this month, the Chinese government outlet Global Times published a report that a People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) unit with the new DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile had carried out an exercise in the “Northwest China’s plateau and desert areas.” The article made vague references to a program previously aired on China’s CCTV-7 that showed a column of DF-26 launchers and support vehicles driving on highways, desert roads, and through mountain streams.

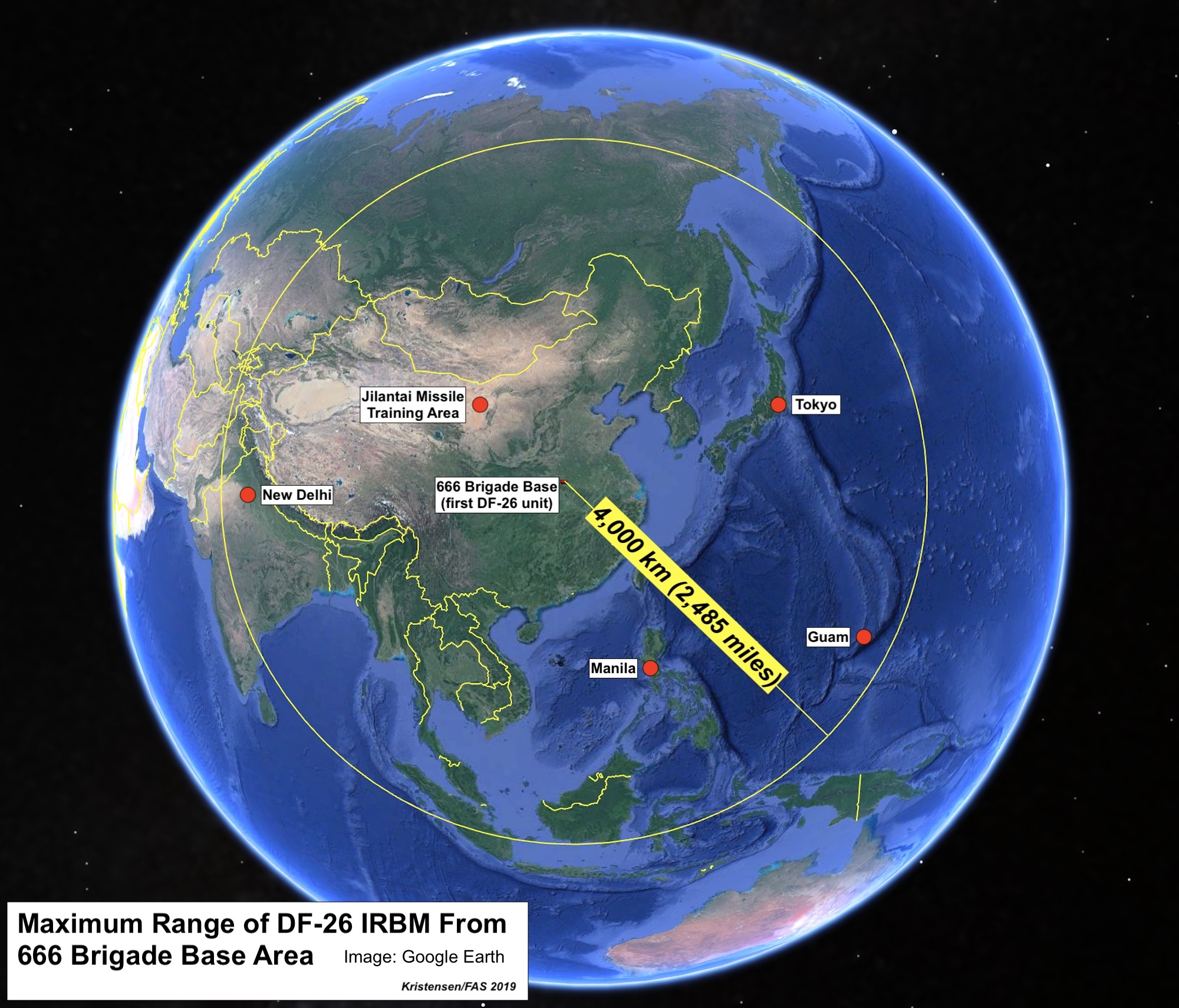

As it turns out, the exercise may have been west of Beijing, but the actual location is in upper Central China. Several researchers (for example Sean O’Connor) have been attempting to learn more about the unit. By combining scenes from the CCTV-7 program with various satellite imagery sources, I was able to geolocate the DF-26s to the S218 highway (39.702137º, 105.731469º) outside the city of Jilantai (Jilantaizhen) roughly 100 km north of Alxa in the Inner Mogolia province in the northern part of central China (see image below).

The DF-26s appear to have been visiting a new missile training area established by PLARF since 2015. By combining use of Google Earth, Planet, and Terra Server, each of which has unique capabilities needed to scan vast areas and identifying individual facilities, as well as analyzing images purchased from Digital Globe, I have so far been able to identify more than 100 launch pads used by launchers and support vehicles during exercises, a support base, a landing strip, and at least eight launch unit camp sites covering an area of more than 1,000 square kilometers (400 square miles) along a 90-kilometer (55-mile) corridor (see image below). A Google Earth placemark file (kml) with all these locations is available for download here.

The Chinese military has for decades been operating a vast missile training area further west in the Qinghai province, which I profiled in an article a decade ago. They also appear to operate a training area further west near Korla (Beyingol). The best unclassified guide for following Chinese missile units is, of course, the indispensable PLA Rocket Force Leadership and Unit Reference produced by Mark Stokes at the Project 2049 Institute.

It is not clear if the DF-26 unit that exercised in the Jilantai training area is or will be permanently based in the region. It is normal for Chinese missile units to deploy long distances from their home base for training. The first brigade (666 Brigade) is thought to be based some 1,100 kilometers (700 miles) to the southeast near Xinyang in southern Henan province. This was not the first training deployment of the brigade. The NASIC reported in 2017 that China had 16+ DF-26 launchers and it is building more. The CCTV-7 video shows an aerial view of a launch unit camp with TEL tents, support vehicles, and personnel tents. A DF-26 is shown pulling out from under a camouflage tent and setting up on a T-shaped concrete launch pad (see image below). More than 100 of those pads have been identified in the area.

The support base at the training area does not have the outline of a permanent missile brigade base. But several satellite images appear to show the presence of DF-16, DF-21, and DF-26 launchers at this facility. One image purchased from Digital Globe and taken by one of their satellites on October 24, 2018, shows the base under construction with what appears to be two DF-16 launchers (h/t @reutersanders) parked between two garages. Another photo taken on August 16, 2017, shows what appears to be 22 DF-21C launchers with a couple of possible DF-26 launchers as well (see below).

The DF-26, which was first officially displayed in 2015, fielded in 2016, and declared in service by April 2018, is an intermediate-range ballistic missile launched from a six-axle road-mobile launchers that can deliver either a conventional or nuclear warhead to a maximum distance of 4,000 kilometers (2,485 miles). From the 666 Brigade area near Xinyang, a DF-26 IRBM could reach Guam and New Delhi (see map below). China has had the capability to strike Guam with the nuclear DF-4 ICBM since 1980, but the DF-4 is a moveable, liquid-fuel missiles that takes a long time to set up, while the DF-26 is a road-mobile, solid-fuel, dual-capable missile that can launch quicker and with greater accuracy. Moreover, DF-26 adds conventional strike to the IRBM range for the first time.

The 666 Brigade is in range of U.S. sea- and air-launched cruise missiles as well as ballistic missiles. But the DF-26 is part of China’s growing inventory of INF-range missiles (most of which, by far, are non-nuclear), a development that is causing some in the U.S. defense community to recommend the United States should withdraw from the INF treaty and deploy quick-launch intermediate-range ballistic missiles in the Western Pacific. Others (including this author) disagree, saying current and planned U.S. capabilities are sufficient to meet national security objectives and that engaging China in an INF-race would make things worse.

See also: FAS Nuclear Notebook on Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2018

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Mixed Messages On Trump’s Missile Defense Review

President Trump personally released the long-overdue Missile Defense Review (MDR) today, and despite the document’s assertion that “Missile Defenses are Stabilizing,” the MDR promotes a posture that is anything but.

Firstly, during his presentation, Acting Defense Secretary Shanahan falsely asserted that the MDR is consistent with the priorities of the 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS). The NSS’ missile defense section notes that “Enhanced missile defense is not intended to undermine strategic stability or disrupt longstanding strategic relationships with Russia or China.” (p.8) During Shanahan’s and President Trump’s speeches, however, they made it clear that the United States will seek to detect and destroy “any type of target,” “anywhere, anytime, anyplace,” either “before or after launch.” Coupled with numerous references to Russia’s and China’s evolving missile arsenals and advancements in hypersonic technology, this kind of rhetoric is wholly inconsistent with the MDR’s description of missile defense being directed solely against “rogue states.” It is also inconsistent with the more measured language of the National Security Strategy.

Secondly, the MDR clearly states that the United States “will not accept any limitation or constraint on the development or deployment of missile defense capabilities needed to protect the homeland against rogue missile threats.” This is precisely what concerns Russia and China, who fear a future in which unconstrained and technologically advanced US missile defenses will eventually be capable of disrupting their strategic retaliatory capability and could be used to support an offensive war-fighting posture.

Thirdly, in a move that will only exacerbate these fears, the MDR commits the Missile Defense Agency to test the SM-3 Block IIA against an ICBM-class target in 2020. The 2018 NDAA had previously mandated that such a test only take place “if technologically feasible;” it now seems that there is sufficient confidence for the test to take place. However, it is notable that the decision to conduct such a test seems to hinge upon technological capacity and not the changes to the security environment, despite the constraints that Iran (which the SM-3 is supposedly designed to counter) has accepted upon its nuclear and ballistic missile programs.

Fourthly, the MDR indicates that the United States will look into developing and fielding a variety of new capabilities for detecting and intercepting missiles either immediately before or after launch, including:

- Developing a defensive layer of space-based sensors (and potentially interceptors) to assist with launch detection and boost-phase intercept.

- Developing a new or modified interceptor for the F-35 that is capable of shooting down missiles in their boost-phase.

- Mounting a laser on a drone in order to destroy missiles in their boost-phase. DoD has apparently already begun developing a “Low-Power Laser Demonstrator” to assist with this mission.

There exists much hype around the concept of boost-phase intercept—shooting down an adversary missile immediately after launch—because of the missile’s relatively slower velocity and lack of deployable countermeasures at that early stage of the flight. However, an attempt at boost-phase intercept would essentially require advance notice of a missile launch in order to position US interceptors within striking distance. The layer of space-based sensors is presumably intended to alleviate this concern; however, as Laura Grego notes, these sensors would be “easily overwhelmed, easily attacked, and enormously expensive.”

Additionally, boost-phase intercept would require US interceptors to be placed in very close proximity to the target––almost certainly revealing itself to an adversary’s radar network. The interceptor itself would also have to be fast enough to chase down an accelerating missile, which is technologically improbable, even years down the line. A 2012 National Academy of Sciences report puts it very plainly: “Boost-phase missile defense—whether kinetic or directed energy, and whether based on land, sea, air, or in space—is not practical or feasible.”

Overall, the Trump Administration’s Missile Defense Review offers up a gamut of expensive, ineffective, and destabilizing solutions to problems that missile defense simply cannot solve. The scope of US missile defense should be limited to dealing with errant threats—such as an accidental or limited missile launch—and should not be intended to support a broader war-fighting posture. To that end, the MDR’s argument that “the United States will not accept any limitation or constraint” on its missile defense capabilities will only serve to raise tensions, further stimulate adversarial efforts to outmaneuver or outpace missile defenses, and undermine strategic stability.

During the upcoming spring hearings, Congress will have an important role to play in determining which capabilities are actually necessary in order to enforce a limited missile defense posture, and which ones are superfluous. And for those superfluous capabilities, there should be very strong pushback.

New START Numbers Show Importance of Extending Treaty

By Hans M. Kristensen

The latest New START treaty aggregate numbers published by the State Department earlier today show a slight increase in U.S. deployed strategic forces and a slight decrease in Russian deployed strategic forces over the past six months.

The data shows that the United States and Russia as of September 1, 2018 combined deployed a total of 1,176 strategic launchers with 2,818 attributed warheads. In addition, the two countries also had a total of 399 non-deployed launchers for a total of 1,576 strategic launchers.

Combined, the two countries have reduced their deployed strategic forces by 227 launchers and 519 warheads since 2011.

The warheads counted by the New START treaty are only a portion of the total warhead numbers possessed by the two countries. The Russian military stockpile includes an estimated 4,350 warheads while the United States has about 3,800.

The release of the data comes at a particular important time when the United States and Russia are considering whether to extend the New START treaty for another five years beyond 2021 when it expires. The treaty is under attack from defense hawks in Congress and the Trump administration is weighing whether to extend New START in light of Russia’s alleged violation of other agreements.

The data reaffirms that Russia, despite its modernization program, is not increasing its strategic nuclear forces but continue to limit them in compliance with the limitations of New START. In our latest Nuclear Notebook on Russia forces, we estimate that the New START limits recently caused Russia to reduce the number of warheads deployed on several of its strategic missiles.

Deployed Warheads

The data shows that the United States as of September 1 deployed 1,398 warheads on its strategic launchers. This is an increase of 48 warheads since February. Since 2011, the United States has offloaded 402 attributed warheads from its force.

The 1,398 is not the actual number of warheads deployed because bombers are artificially attributed one weapon each even though they don’t carry any weapons in peacetime. The actual number of deployed warheads is closer to 1,350.

Russia was counted with 1,420 deployed strategic warheads, a reduction of 24 warheads from February, and a total of 117 attributed warheads offloaded since 2011. Russian bombers also do not carry weapons so the Russian number is probably closer to 1,370 deployed strategic warheads.

These changes don’t reflect one country building up and the other reducing its forces, but are caused by fluctuations when launchers move in and out of maintenance or old launchers are retired or new ones added.

Deployed Launchers

The data shows the United States deployed 659 strategic launchers, an increase of 7 since February, and a total reduction of 223 launchers since 2011.

Russia deployed 517 strategic launchers, 142 fewer than the United States. That is 10 launchers less than in February, and a total reduction of 4 launchers since 2011.

Non-Deployed Launchers

The data also shows how many non-deployed launchers the two countries have. These are either empty launchers that are in reserve or overhaul or have not yet been destroyed.

The United States had 141 non-deployed launchers, which included empty ICBM silos, bombers in overhaul, and empty missile tubes on SSBNs in overhaul or refit. Since 2011, the United States has destroyed 101 non-deployed launchers.

Russia was counted with 258 non-deployed launchers. This includes empty ICBM silos, empty missile tubes on SSBNs in overhaul, and bombers in overhaul. Since 2011, Russia has destroyed 86 non-deployed launchers.

Essential Verification In Troubled Times

The treaty includes an important verification system that requires the United States and Russia to exchange vast amounts of data about the numbers and operations of their strategic forces and allows them to inspect each other’s facilities.

Since the treaty entered into effect in 2011, the two countries have exchanged 16,444 notifications about launcher movements and telemetry data; 1,603 since February this year.

Data released by the State Department shows that U.S. and Russian inspectors have conducted a total of 277 on-site inspections of each other’s strategic forces and facilities since the treaty entered into force in 2011. So far this year, U.S. officials have inspected Russian facilities 13 times compared with 12 Russian inspections of U.S. facilities.

The combined effects of limiting deployed strategic forces and the verification activities requiring professional collaboration between U.S. and Russian officials, mean that the New START treaty has become a beacon of light in the otherwise troubled relations between Russia and the United States, far more so than anyone could have predicted in 2010 when the treaty was signed.

Other background information:

- Russia nuclear forces, 2018

- US nuclear forces, 2018

- Status of world nuclear forces, 2018

- After Seven Years of Implementation, New START Treaty Enters Into Effect

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

USAF: Implementing Arms Control Treaties

The implementation of arms control agreements by the Air Force is detailed in a newly updated directive.

The directive addresses Air Force obligations under New START, US-IAEA Safeguard Agreements, the Chemical Weapons Convention, and the Biological Weapons Convention.

See Implementation of, and Compliance with, Treaties Involving Weapons of Mass Destruction, Air Force Instruction 16-608, September 7, 2018.

Air Force officials are directed to make certain that even their most tightly secured special access programs are in compliance with international obligations. But they are also required to protect information about such programs from “unnecessary or inadvertent” exposure during verification activities.

Nuclear Weapons Maintenance as a Career Path

The US Air Force has published new guidance for training military and civilian personnel to maintain nuclear weapons as a career specialty.

See Nuclear Weapons Career Field Education and Training Plan, Department of the Air Force, April 1, 2018.

An Air Force nuclear weapons specialist “inspects, maintains, stores, handles, modifies, repairs, and accounts for nuclear weapons, weapon components, associated equipment, and specialized/general test and handling equipment.” He or she also “installs and removes nuclear warheads, bombs, missiles, and reentry vehicles.”

A successful Air Force career path in the nuclear weapons specialty proceeds from apprentice to journeyman to craftsman to superintendent.

“This plan will enable training today’s workforce for tomorrow’s jobs,” the document states, confidently assuming a future that resembles the present.

Meanwhile, however, the Air Force will also “support the negotiation of, implementation of, and compliance with, international arms control and nonproliferation agreements contemplated or entered into by the United States Government,” according to a newly updated directive.

See Air Force Policy Directive 16-6, International Arms Control and Nonproliferation Agreements and the DoD Foreign Clearance Program, 27 March 2018.

Despite Rhetoric, US Stockpile Continues to Decline

Click on image to view full size. Full document here.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The US nuclear weapons stockpile dropped to 3,822 warheads by September 2017 – down nearly 200 warheads from the last year of the Obama administration, according to new information released by the Department of Defense in response to a request from the Federation of American Scientists (see here for full document).

Since September 2017, the number has likely declined a little further to about 3,800 warheads as of March 2018. This is the lowest number of stockpiled warheads since 1957 (see graph), although the nuclear weapons and the conventional capabilities that make up today’s arsenal are vastly more capable than back then.

The new data also shows that the United States dismantled 354 warheads during the period October 2016 to September 2017 – the highest number of warheads dismantled in a single year since 2009. Since 1994, the United States has dismantled nearly 11,000 nuclear warheads.

The continued reductions are not the result of new arms control agreements or a change in defense planning, but reflects a longer trend of the Pentagon working to reduce excess numbers of warheads while upgrading the remaining weapons. This trend is as old as the Post Cold war era.

The majority of the warheads retired during the Trump administration’s first year probably included W76-0 warheads no longer needed as feedstock for the Navy’s W76-1 life-extension program.

The reduction has happened despite tensions with Russia, bombastic nuclear statements by President Donald Trump, and Nuclear Posture Review assertions about return of Great Power competition and need for new nuclear weapons.

The apparent disconnect between rhetoric and the stockpile trend illustrates that nuclear deterrence and national security are less about the size of the arsenal than what it, and the overall defense posture, can do and how it is postured.

Although defense hawks home and abroad will likely seize upon the reduction and argue that it undermines deterrence and reassurance, the reality is that it does not; the remaining arsenal is more than sufficient to meet the requirements for national security and international obligations. On the contrary, it is a reminder that there still is considerable excess capacity in the current nuclear arsenal beyond what is needed.

President Trump recently said he expected to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin “in the not-too-distant future to discuss the arms race,” which Trump added “is getting out of control…” He is right. In such discussions he should urge Russia to follow the U.S. example and also disclose the size of its nuclear warhead stockpile, agree to extend the New START treaty for five years, work out a roadmap to resolve INF Treaty compliance issues, and develop new agreements to regulate nuclear and advanced conventional forces.

There is much work to be done.

Additional information:

Declassified stockpile numbers.

Recent FAS Nuclear Notebook on US nuclear forces (written before the new stockpile information became available).

For an overview of all nuclear-armed states, see our Status of World Nuclear Forces.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Crowdsourcing the Verification of Nuclear Safeguards

The possibility of mobilizing members of the public to collect information — “crowdsourcing” — to enhance verification of international nuclear safeguards is explored in a new report from Sandia National Laboratories.

“Our analysis indicates that there are ways for the IAEA [International Atomic Energy Agency] to utilize data from crowdsourcing activities to support safeguards verification,” the authors conclude.

But there are a variety of hurdles to overcome.

“Some implementations of crowdsourcing for safeguards are legally or ethically uncertain, and must be carefully considered prior to adoption.”

Crowdsourced information, like other information, has to be independently verified, particularly since it is susceptible to error, manipulation and deception.

The report builds on previous work cited in a bibliography. See Power of the People: A Technical, Ethical and Experimental Examination of the Use of Crowdsourcing to Support International Nuclear Safeguards Verification by Zoe N. Gastelum, et al, Sandia National Laboratories, October 2017.

After Seven Years of Implementation, New START Treaty Enters Into Effect

Russia and the United States are currently in compliance with the treaty limits of the New START treaty. This table summarizes the evolution of the three weapons categories reported between 2011 and 2018. (Click on graph to view full size.)

By Hans M. Kristensen

[Note: On February 22nd, the US State Department published updated numbers instead of relying on September 2017 numbers. This blog and tables have been updated accordingly.]

Seven years after the New START treaty between Russia and the United States entered into force in 2011, the treaty entered into effect on February 5. The two countries declared they have met the limits for strategic nuclear forces.

At a time when relations between the two countries are at a post-Cold War low and defense hawks in both countries are screaming for new nuclear weapons and declaring arms control dead, the achievement couldn’t be more timely or important.

Achievements by the Numbers

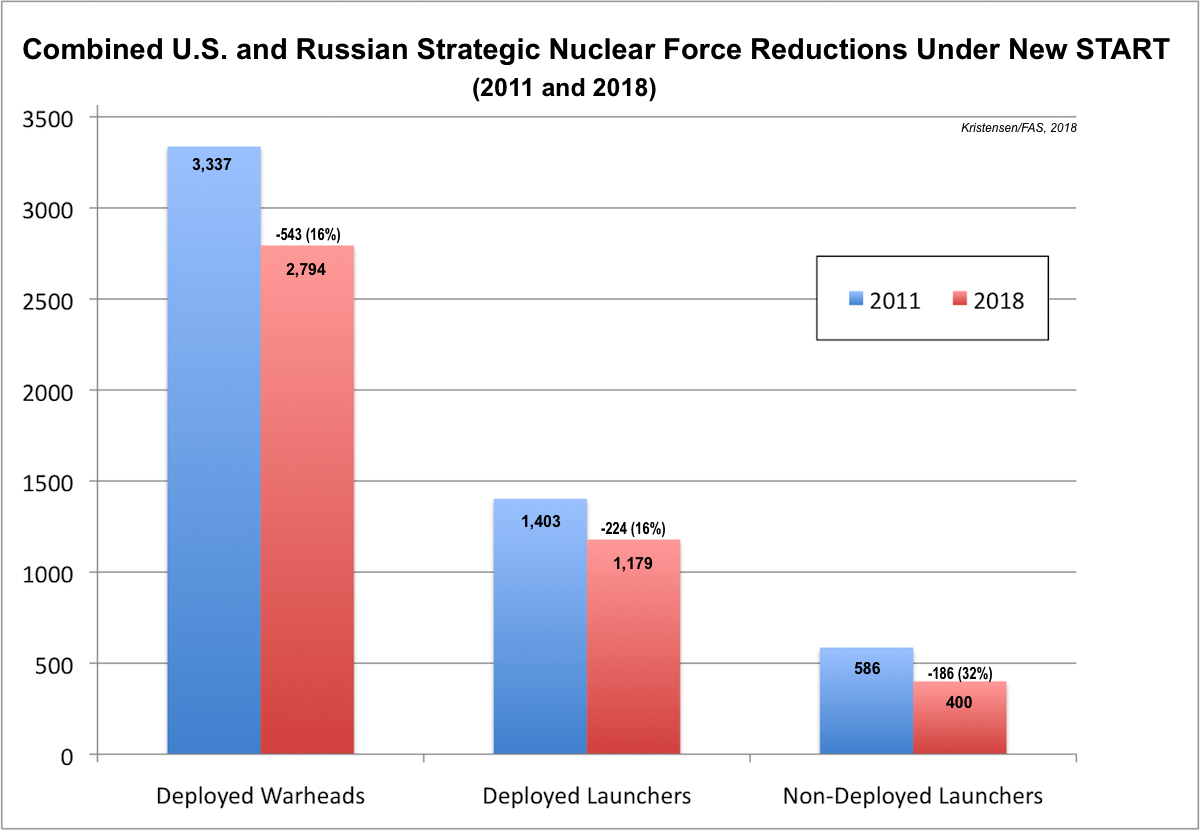

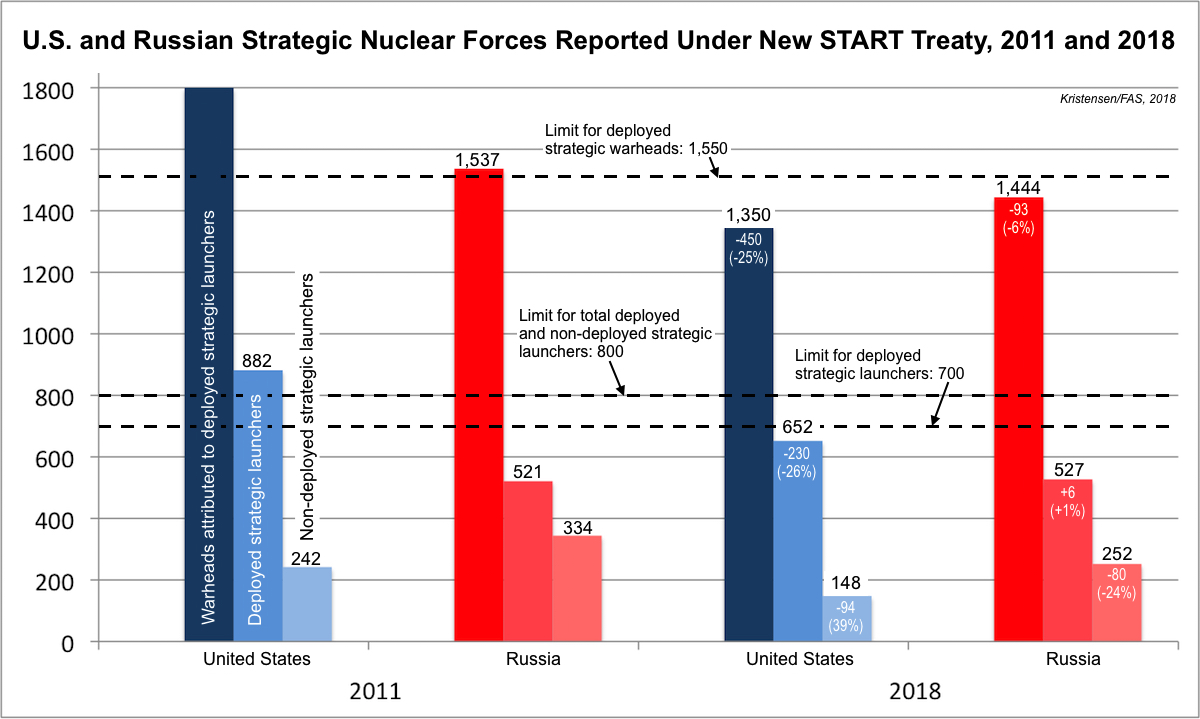

The declarations show that Russia and the United States currently deploy a combined total of 2,794 warheads on 1,179 deployed strategic launchers. An additional 400 non-deployed launchers are empty, in overhaul, or awaiting destruction.

Compare that with the same categories in 2011: 3,337 warheads on 1,403 deployed strategic launchers with an additional 586 non-deployed launchers.

In other words, since 2011, the two countries have reduced their combined strategic forces by: 543 deployed strategic warheads, 224 deployed strategic launchers, and 186 non-deployed strategic launchers. These are modest reductions of about 16 percent over seven years for deployed forces (see chart below).

The New START data shows the world’s two largest nuclear powers have reduced their deployed strategic force by about 15 percent over the past seven years. (Click on graph to view full size.)

The Russian statement reports 1,444 warheads on 527 deployed strategic launchers with another 392 non-deployed launchers.

That means Russia since 2011 has reduced its deployed strategic warheads by 93, or only 6 percent. The number of deployed launchers has increased a little, by 6, while non-deployed launchers have declined by 80, or 24 percent (see chart below).

The Russian numbers hide an important new development: In order to meet the New START treaty limit, the warhead loading on some Russian strategic missiles has been reduced. The details of the download are not apparent from the limited data published by Russia. I am currently working on developing the estimate for how the download is distributed across the Russian strategic forces. The analysis will be published in a subsequent blog, as well in our next FAS Nuclear Notebook and in the 2018 SIPRI Yearbook.

The US statement lists 1,350 warheads on 652 deployed strategic launchers, and 148 non-deployed launchers.

That means the United States since 2011 has reduced its deployed strategic warheads by 450, or 25 percent. The number of deployed launchers has been reduced by 230, or 26 percent, while the number of non-deployed launchers had declined by 94, or 39 percent (see chart below).

US and Russian strategic force structures differ significantly. As a result, the reductions under New START have affected the two countries differently. Russia has significantly fewer launchers so rely on great warhead-loading to maintain rough overall parity. (Click on chart to view full size.)

In Context

The reason for the different reductions is, of course, that the United States in 2011 had significantly more warheads and launchers deployed than Russia. During the New START negotiations, the US military insisted on a higher launcher limit than proposed by Russia. So while Russia by the latest count has 94 deployed warheads more than the United States, the United States enjoys a sizable advantage of 125 deployed strategic launchers more than Russia. Those extra launchers have a significant warhead upload capacity, a potential treaty breakout capability that Russian officials often complain about.

So despite the importance of the New START treaty and its achievements, not least its important verification regime, the declared numbers are a reminder of how far the two nuclear superpowers still have to go to reduce their unnecessarily large nuclear forces. Ironically, because the US military insisted on a higher launcher limit, Russia could – if it decided to do so, although that seems unlikely – build up its strategic launchers to reduce the US advantage, and still be in compliance with the treaty limits. The United States, in contrast, is at full capacity.

But the apparent download of warheads on Russia’s strategic missiles demonstrates an important effect of New START: It actually keeps a lid on the strategic force levels.

Still, not to forget: The deployed strategic warhead numbers counted under New START represent only a portion of the total number of warheads the two countries have in the arsenals. We estimate that the deployed strategic warheads declared by the two countries represent on about one-third of the total number of warheads in their nuclear stockpiles (see here for details).

This all points to the importance of the two countries agreeing to extend the New START treaty for an additional five years before it expires in 2021. Neither can afford to abandon the only strategic limitations treaty and its verification regime. Failing this most basic responsibility would, especially in the current political climate, remove any caps on strategic nuclear forces and potentially open the door to a new nuclear arms race. The warning signs are all there: East and West are in an official adversarial relationship, increasing military posturing, modernizing and adding nuclear weapons to their arsenals, and adjusting their nuclear policies for a return to Great Power competition.

The symbolic importance of New START could not be greater!

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Data Shows Detail About Final Phase of US New START Treaty Reductions

By Hans M. Kristensen

The full unclassified New START treaty data set released by State Department yesterday shows that the US reduction of its nuclear forces to meet the treaty limit had been completed by September 1, 2017, more than four months early before the deadline next month on February 5, 2018.

The data set reveals details about how the final reduction was achieved (see below).

Unfortunately, no official detailed data is released about the Russian force adjustments under New START. Our previous analysis of the overall September 1, 2017 New START data is available here.

Submarines

During that six-month period last year, 20 ballistic missile submarine launch tubes were deactivated, corresponding to four tubes on five Ohio-class submarines. Two of those submarines were in drydock for refueling and not part of the operational force.

In total, the United States has deactivated 56 strategic missile submarine launch tubes since the New START treaty went into effect in 2011, although the first reduction didn’t begin until after September 2016 – more than five years into the treaty.

The USS Louisiana (SSBN-743) returns to Kitsap Submarine Base in Washington on October 15, 2017 after a deterrent patrol in the Pacific Ocean. The submarine carried 20 Trident II missiles with an estimated 90 nuclear warheads.

Of the 280 submarine launch tubes, only 212 were counted as deployed with as many Trident II missiles loaded. The treaty counts a missile as deployed if it is in a launch tube regardless of whether the submarine is deployed at sea. The United States has declared that it will not deploy more than 240 missiles at any time. Assuming each deployed submarine carries a full missile load, the 212 deployed missiles correspond to 10 submarines fully loaded with a total of 200 missiles. The remaining 12 deployed missiles were onboard one or two submarines loading or offloading missiles at the time the count was made.

The data shows that the 212 deployed missiles carried a total of 945 warheads, or an average of 4 to 5 warheads per missile, corresponding to 70 percent of the 1,344 deployed warheads as of September 1, 2017 (the New START count was 1,393 deployed warheads, but 49 bombers counted as 49 weapons don’t actually carry warheads, leaving 1,344 actual warheads deployed). If fully loaded, the 240 deployable SLBMs could carry nearly 2,000 warheads.

The Navy has begun replacing the original Trident II D5 missile with an upgraded version known as Trident II D5LE (LE for life-extension). The upgraded version carries the new Mk6 guidance system and the enhanced W76-1/Mk4A warhead (or the high-yield W88-0/Mk5). In the near future, according to the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), some of the missiles would be equipped with a low-yield version of the W76-1.

The Navy is developing a new fleet of 12 Columbia-class missile submarines to begin replacing the Ohio-class SSBNs in the late-2020s. The Trump NPR states that “at least” 12 will be built. Each Columbia-class SSBN, the first of which will deploy on deterrent patrol in 2031, will have 16 missile tubes for a total of 192, a reduction of one-third from the current number of SSBN tubes. Ten deployable boats will be able to carry 160 Trident II D5LE missiles with a maximum capacity of 1,280 warheads; normally they will likely carry about the same number of warheads as the current force, with an average of about 5 to 6 warheads per missile.

ICBMs

The New START data shows the United States now has just under 400 Minuteman III ICBMs in silos, down from 405 in March 2017. Normally the Air Force strides to have 400 deployed but one missile was undergoing maintenance.

A Minuteman III ICBM is removed from its silo at F.E. Warren AFB on June 2, 2017, the last to be offloaded to bring the United States into compliance with the New START treaty limits.

Although the number of deployed ICBMs had declined from 450 to 400, the total numbers of missiles and silos have not. The data shows the Air Force has the same number of missiles and silos as in March 2017 because 50 empty silos are “kept warm” and ready to load 50 non-deployed missiles if necessary. Reduction of deployed ICBMs started in 2016, five years after the New START was signed. And the actual ICBM force is the same size as when the treaty was signed.

The 399 deployed ICBMs carried 399 W78/Mk12A or W87/Mk21 warheads. Although normally loaded with only one warhead each, the Trump NPR confirms that “a portion of the ICBM force can be uploaded” if necessary. We estimate the ICBM force has the capacity to carry a maximum of 800 warheads.

An ICBM replacement program is underway to build a new ICBM (programmatically called Ground Based Strategic Deterrent) to begin replacing the Minuteman III from 2029. The new ICBM will have enhanced penetration and warhead fuzing capabilities.

Heavy Bombers

The New START data shows the US Air Force has completed the denuclearization of excess nuclear bombers to 66 aircraft. This includes 20 B-2A stealth bombers for gravity bombs and 46 B-52H bombers for cruise missiles. Only 49 of the 66 bombers were counted as deployed as of September 1, 2017. Another 41 B-52Hs have been converted to non-nuclear armament such as the conventional long-range JASSM-ER cruise missile.

The New START treaty counts each of the 66 bombers as one weapon even though each B-2A can carry up to 16 bombs and each B-52H can carry up to 20 cruise missiles. We estimate there are nearly 1,000 bombs and cruise missiles available for the bombers, of which about 300 are deployed at two of the three bomber bases.

The first B-52H bomber was denuclearized under New START in September 2015. Denuclearization of excess nuclear bombers was completed in early 2017.

The bomber force was the first leg of the Triad to begin reductions under New START, starting with denuclearization of the (non-operational) B-52Gs and later excess B-52Hs. The first B-52H war denuclearized in September 2015 and the last of 41 in early 2017. Despite the denuclearization of excess aircraft, however, the actual number of bombers assigned nuclear strike missions under the strategic war plans is about the same today as in 2011.

A new heavy bomber known as the B-21 Raider is under development and planned to begin replacing nuclear and conventional bombers in the mid-2020s. The B-21 will be capable of carrying both the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb and the new LRSO nuclear cruise missile. The Air Force wants at least 100 B-21s but can only make 66 nuclear-capable unless it plans to exceed the size of the current nuclear bomber force.

Looking Ahead

With the completion of the force reductions under New START in preparation for the treaty entering into effect on February 5, 2018, the attention now shifts to what Russia and the United States will do to extend the treaty or replace it with a follow-up treaty. With its on-site inspections and ceilings on deployed and non-deployed strategic forces, extending New START treaty for another five years ought to be a no-brainer for the two countries; anything else would increase risks to strategic stability and international security. If the treaty is allowed to expire in 2021, there will be no – none! – limits on the number of strategic nuclear forces. Unfortunately, right now neither side appears to be doing anything except to blame the other side for creating problems. It is time for Russia and the United States to get out of the sandbox and behave like responsible states by agreeing to extend the New START treaty. February 5 – when the treaty enters into effect just 23 days from now – would be a great occasion for the two countries to announce their decision to extend the treaty.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.