Small Arms in Iraq Vulnerable to Theft and Diversion

By Matthew Buongiorno

Scoville Fellow

Shortly after the United States invaded Iraq and disbanded its army, the Bush Administration concluded that a key to stabilizing the country was the creation of a self-sufficient and effective Iraqi Security Force (ISF). To this end, the Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund (IRRF) – later succeeded by the Iraq Security Forces Fund (ISFF) – was established as a train-and-equip program charged with quickly delivering weaponry to the ISF. While the ad hoc program was successful in quickly supplying large quantities of weapons to the ISF, it lacked the stringent accountability procedures applied to other U.S. arms transfer programs and, consequently, may have failed to prevent the diversion of U.S. weapons.

Recognizing the dangers associated with poorly secured weaponry, the United States has taken several important steps to improve stockpile security and accountability procedures for U.S.-origin and U.S.-funded weapons transferred to Iraq. These steps are assessed in the latest edition of the Public Interest Report.

The article draws on documents retrieved by the Federation of American Scientists via the Freedom of Information Act. These documents, as well as additional documents not cited in the article but of relevance to the debate over security and accountability procedures in Iraq, are posted below:

▪ Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) Compliance with Section 1228 of FY08 NDAA

United States Moves Rapidly Toward New START Warhead Limit

|

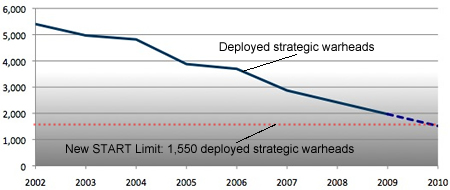

| Current pace of U.S. strategic warhead downloading could reach New START limit in 2010. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The United States appears to be moving toward early implementation of the New START treaty signed with Russian less than one month ago.

The rapid implementation is evident in the State Department’s latest fact sheet, which declares that the United States as of December 31, 2009, deployed 1,968 strategic warheads.

The New START force level of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads is not required to be reached until 2017 at the earliest. But at the current downloading rate, the United States could reach the limit before the end of this year.

Since the signing of the Moscow Treaty in 2002, the United States has removed an average of 490 warheads each year from ballistic missiles and bomber bases, for a total of approximately 3,436 warheads. There are now only a few hundred strategic warheads left at U.S. bomber bases, with most of the deployed warheads concentrated on ballistic missiles.

The last time the United States deployed less than 2,000 strategic warheads was in 1956. The peak was nearly 12,790 deployed strategic warheads in 1987.

The rapid downloading of U.S. strategic forces illustrates just how confident the military is in the capability of U.S. nuclear forces to provide a credible deterrent even at the New START level. Several thousand non-deployed warheads in storage can be loaded back onto missiles and bombers if necessary.

Even so, the rapid downloading gives the Obama administration a strong basis to argue at the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference that it is serious about moving forward on nuclear arms control.

Additional information: United States Reaches Moscow Treaty Warhead Level Early | Obama and the Nuclear War Plan

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Recommendations for the U.S. Delegation to the NPT Review Conference

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) has endured as the cornerstone of the non-proliferation regime and remains the only legally binding multilateral agreement on nuclear disarmament. In May 2010, the NPT Review Conference met at the United Nations and provided a critical opportunity to advance the vision President Obama laid out of a world free of nuclear weapons.

U.S. Defense Department sold more than $15 billion in arms in the first quarter of Fiscal Year 2009, report reveals

By Matt Schroeder

Arms sold by the Defense Department to foreign recipients totaled more than $15 billion in the first quarter of Fiscal Year 2009, according to a report obtained by the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). The quarterly report, which is dated February 2009 and is required by Section 36(a) of the Arms Export Control Act, indicates that defense articles and services sold through Defense Department Security Assistance programs from October through December 2008 were worth approximately $15.79 billion[1]. The United Arab Emirates was the largest buyer, accounting for $7 billion of sales. Saudi Arabia was a distant second with $1.87 billion, and Iraq was third with $947 million in sales. The remaining top ten recipients are listed in the table below. Sales to the top ten countries accounted for more than 80% of total sales, and nearly 89% of unclassified arms sales. These data show that a handful of countries continue to account – in dollar value terms – for the vast majority of arms sold through the US Defense Department.

| DSCA Security Assistance Sales

1 October 2008 through 31 December 2008 |

|

| Country | Total Estimated Case Value |

| United Arab Emirates | $7,017,276,438 |

| Saudi Arabia | $1,874,981,657 |

| Iraq | $947,469,859 |

| NAMO | $871,283,087 |

| Egypt | $479,317,918 |

| South Korea | $476,861,899 |

| Switzerland | $303,522,255 |

| Turkey | $258,385,648 |

| Canada | $255,271,952 |

| Colombia | $219,957,504 |

| Source: Quarterly report required under Section 36(a) of the Arms Export Control Act, February 2009. Table compiled by the Federation of American Scientists. | |

The report contains new or more detailed data on the following:

• Foreign Military Sales (FMS) Direct Credits and Grant Apportionment for FY09 as of 31 December 2008.

• Foreign Military Sales projections for FY09 as of 31 December 2008.

• Foreign Military Construction Sales, 1 October 2008 through 31 December 2008.

• Security Assistance Surveys authorized between 1 October and 31 December 2008.

• Waivers of nonrecurrent cost (NC) recoupment charges, 1 October 2008 through 31 December 2008. Note: this section contains detailed commodity data.

Much of this data is not available in other reports, or is not as detailed. For example, the Section 36(a) report contains specific data on missile sales, most of which are redacted in the most comprehensive publicly available source of data, the Annual Military Assistance Report (i.e. Section 655 report).[2] Data on sales of other commodities are also notably more specific than comparable data in the Annual Military Assistance Report. For example, the Section 36(a) report reveals that an October 2008 ammunition sale to Israel consisted of HEDP, White Star & Practice 40 mm ammunition valued at $9,897,682. Comparable data on ammunition (deliveries) in the Annual Military Assistance Report is aggregated into commodity categories that are so broad (e.g. “cartridge, 37 mm to 75 mm”) that the data are almost meaningless.

The Section 36(a) report is not a substitute for the Annual Military Assistance Report. It only includes disaggregated data[3]. on sales agreements, not actual deliveries, and only on a small sub-set of Defense Department arms sales (i.e. sales of Major Defense Equipment valued at $1 million or more). Furthermore, the data on commercial sales were withheld from public release by the Department of State [To the State Department’s credit, however, they recently posted a CSV file containing the data on commercial exports in the FY08 Section 655 report. CSV files are readily convertable into excel spreadsheets, databases, and other use-friendly research tools].

In short, the Section 36(a) report is a useful supplement to the Annual Military Assistance Report, and its narrow and specific commodity categorization is a model for other reports, many of which, like the Annual Military Assistance Report, are in dire need of an overhaul (See Eight Recommendations for Improving Transparency in US Arms Transfers).

The FAS has submitted requests for more recent editions of the Section 36(a) report, and will post them on the Strategic Security Blog and our U.S. Arms Transfers: Government Data webpage as they become available.

Click here for a pdf version of this summary.

[1] A more complete accounting of the value of arms sales in FY2009 will be released within the next couple months as part of the “supporting information” in the Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations. Data from previous years is available on the Federation of American Scientists’ website.

[2] It should be noted that the commodity-specific data in the Section 36(a) report is on agreements (i.e. accepted Letters of Offer and Acceptance) while the data on Defense Department exports in the Section 655 report is on arms that were delivered to the foreign recipient.

[3] By disaggregated data, we are referring to country-specific data that is disaggregated by commodity.

Hardly a Jump START

Four months past a “deadline” imposed by the expiration of the old START treaty and amid much fanfare, President Obama announced that he and Russian President Medvedev had agreed on a new arms control treaty. I am not as excited as most are about the treaty and much of the following might be interpreted as raining on the parade so let me begin by saying that the negotiation of this treaty is an important step. While not as big a step as I had hoped for, it is an essential step.

Whatever the actual reductions mandated by the treaty—and they are modest—it was vital to get the United States and Russia talking about nuclear weapons again. The U.S. and Russia have at least 95% of the world’s nuclear weapons and they have to lead the world in nuclear reductions. Without this first step there cannot be a second step and there are many steps between where we are today and a world free of nuclear weapons.

The Bush administration did not simply dismiss arms control as irrelevant but argued that negotiating agreements was actually counter productive, potentially creating confrontation where it would not otherwise arise. Avoid talking and let sleeping dogs lie was the philosophy. The Bush administration had the best of both worlds, from its perspective, by negotiating the nearly meaningless Strategic Offensive Reduction Treaty, SORT, sometimes called the Moscow Treaty, that simply allowed each side to declare their plans for what they were going to do anyway and contained no verification provisions.

This treaty is different. The White House has released summaries of the main features of the treaty, not the full text, but it is clear this is a real treaty with real limits and real verification. This treaty and, more importantly, the process that produced it, gets the arms control train back on the track.

Even so, this treaty is a modest step. Hans Kristensen has described the numbers and their implications for the nuclear force structure. The treaty makes some modest reductions from the SORT limits but not large enough changes to make a qualitative difference in the nuclear standoff between the legacy forces of the two Cold War superpowers. (If anyone can explain to me why we and the Russians continue to need over a thousand nuclear bombs, each five to twenty five times more powerful than the bomb that flattened Hiroshima, pointed at each other, please send me an email. I want to know what the beef between us is that makes that seem proportionate.)

The treaty does not even approach territory that would call for a fundamental rethinking of how we deploy our nuclear weapons. As the military would say, the treaty protects the force structure. That is, we will still have a triad of bombers and both land-based and sea-based ballistic missiles, another obsolete artifact of the Cold War that dates back to fears of a disarming first strike from the Soviet Union (and inter-Service competition). Even Air Force advocacy groups such as the Mitchell Institute have considered eliminating the nuclear mission for the manned bomber and moving from a triad to a dyad of land- and sea-based missiles. In fact, the treaty contains a peculiar counting rule that increases the importance of bombers: each bomber counts only as one nuclear bomb although the B-52 can carry 20 nuclear-armed cruise missiles and the Russian bombers, for example the Backfire and Blackjack, have similar payloads. If we define corn as a type of tree, then suddenly Iowa would be covered in forests. If we define a bomber with 20 bombs as a single bomb, then suddenly we get a substantial reduction in the nuclear of weapons. (Hans discusses the numbers in more detail.) This rule reportedly resulted from Russia’s refusal to allow the necessary on-site inspections at its bomber bases but it creates an important caveat on any claim of “reductions.”

The treaty apparently does not address in any way nuclear weapon alert levels. Most of the deployed weapons both sides will have under the treaty will be continuously ready to launch within minutes. The treaty does nothing to restrict both nuclear powers to a no-first-use capability. If we wanted to reduce the threat that Russia and the U.S. pose to one another, we would be far better off to ignore the numbers of weapons but take weapons off alert so the current treaty has that exactly wrong.

Non-deployed warheads are not covered by the treaty at all as far as I can tell from the summaries. Both sides will still retain thousands of nuclear weapons not mounted on missiles and these are not even counted, much less limited, by the treaty. Apparently the verification of reserve warhead limits was too intrusive. While inspection of warhead dismantlement facilities is allowed, I cannot tell from the summary exactly what is going to be verified. I believe that the dismantlement itself will not be monitored.

One of the strengths of the treaty is that it limits actual missile warheads and provides for the verification of deployed missile warheads. In the past, there has been no way to verify warhead numbers so treaties resorted to “counting rules,” that is, those things that could be counted, namely bombers, submarines, and missile silos, were counted and each launcher was simply assumed to have a certain number of nuclear warheads associated with it. For example, if a type of missile had been tested with eight warheads, then all missiles of that type would be counted as having eight warheads regardless of the number actually mounted on top. Thus, in previous treaties, limits on the number of warheads were indirect. With this treaty, on-site inspections will allow each side to confirm though a limited number of spot-checks the number of missile warheads actually mounted on missiles.

The U.S. has wanted to keep the number of launchers high while accommodating modest reductions in the number of warheads. It has done this up to now by removing (or off-loading) warheads from multiple warhead missiles. The Russians have objected that this creates worrying breakout potential: the U.S. could reactivate reserve warheads and quickly mount them back atop the existing missiles, called uploading. In a crisis, this creates instability: if the one side sees the other uploading warheads, there is a strong incentive to strike before the process can proceed to completion. This is the argument the Russians used for limits on launchers. (Plus, of course, the Russians are short of money and want to reduce the number of their missiles anyway so better to get the Americans to come along with them.) The U.S. accepted the Russian launcher number but was unwilling to proportionately cut warheads. This creates a ratio of launchers and warheads that is not terrible but could be better. Having several warheads atop each missile makes them relatively more attractive targets of a disarming surprise first strike; this is called first strike instability. So the conflicting goals of Russia and the U.S. have forced them into trading one form of crisis instability for another. Note that, if reserve warheads were verifiably eliminated, the Russian fear of uploading would be addressed.

Given the very modest nature of the treaty, it should sail through ratification, in a normal political climate. But this is not a normal political climate. As Secretary Clinton pointed out, past arms control treaties have been ratified by the Senate by 90 votes or more. But after the passage of the health care bill, the Republicans may be unwilling to give President Obama a foreign policy success. Senator McCain has said that there will be no more cooperation in the Senate for the rest of the year. We shall see. But clearly, the Senate Republicans’ no-compromise tactics may doom treaty ratification. One thing seems certain to me: the Republicans have shown remarkable party discipline in the Senate so treaty ratification will either fail or it will succeed with close to one hundred votes. It depends on a political decision by the minority caucus.

I did not attend the White House briefing on the treaty but Hans did and reports that, according to the administration, many shortcomings of the treaty resulted from Russian resistance to intrusive verification measures. If true, this bodes ill for future dramatic achievements, for example, limits on non-deployed warheads or verifying the dismantlement of nuclear warheads. The Russians may, in part, be cautious about intrusive verification because it might reveal strategic vulnerabilities. If this is so, then the U.S. could do much to allay those fears by moving away from a counterforce capability that threatens Russian central nuclear forces every minute of the day.

After all this complaining, I have to repeat my first point: this is an important treaty, it gets us back on track, it should be welcomed, and ratified. I wish it had been bolder, I wish it had taken bigger steps, I wish it had made qualitative as well as quantitative changes, but it moves entirely in the right direction.

What next? This has long been described as a transitional treaty. It was meant to be a bridge between the expired START treaty and the next treaty, which is going fundamentally reshape the nuclear relationship of the Cold War legacy nuclear powers. We can hope so. The treaty has a ten-year lifetime with the option to extend for another five. If this is all we do for the next decade, it will, indeed, be disappointing. We cannot think we are done, these laurels are far too small to rest on comfortably. This treaty must be considered what it was sold as a year ago: a stopgap to paste over the expiration of START while the transformational treaty is negotiated. Alas, given the difficulty of negotiating this modest instrument, it may take ten years to get the next treaty.

If this treaty is a preview of the soon-to-be released nuclear posture review (NPR), then we will know that transformation of the nuclear danger is merely a theoretical aspiration not an actual goal of the administration. If, on the other hand, the NPR calls for unilaterally reducing the alert rate of our nuclear forces, reduces the counterforce emphasis on nuclear weapons and their deployment, and lays out clear steps the U.S. intends to take soon toward a world free of nuclear weapons, then it could form the basis for a truly transformational next treaty with Russia. Much of the wariness of the Russians is perfectly justified by the constant treat of a disarming U.S. first strike. We have to change that reality first and then we can institutionalize it with a treaty.

Also, we must carefully weigh the domestic political price tag that the treaty is going to carry. Even before the this treaty got out of the gate, or the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty was warmed up, the administration came in with a budget that included a $700M top up to the national labs. This was widely considered a minimum down payment to get the labs and conservative Senators on board supporting the treaties. It may well be, especially in light of recently released letters from the lab directors, that a new warhead development program (and not just a new warhead, but an ongoing program to institutionalize continuing production of new warheads into the indefinite future) will be the price for either treaty. I am not convinced that that price is worth paying. (It might if we did it right but that seems unlikely. I will write again on that topic.) In any case, if the treaty is not ratified, I think it is fair to use substantial budget cuts to make certain that the labs don’t start new warhead production.

The treaty is going to be signed in Prague on 8 April. That is a Thursday, so I think we should be gracious and let the negotiators take that Friday and the rest of the weekend off but I hope that, on Monday 12 April, they will be back at work negotiating the real treaty, the one that changes fundamentally the insane calculus of the nuclear standoff between the U.S. and Russia.

[In the above, I made a slight edit. In the original version from this morning, I said that “warheads” were counted, thinking that it was clear this meant missile warheads as opposed to bombs on bombers but some readers were confused. I now say “missile warheads.”]

New START Treaty Has New Counting

|

| An important new treaty reduces the limit for deployed strategic warheads but not the number. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The White House has announced that it has reached agreement with Russia on the New START Treaty. Although some of the documents still have to be finished, a White House fact sheet describes that the treaty limits the number of warheads on deployed ballistic missiles and long-range bombers on both sides to 1,550 and the number of missiles and bombers capable of launching those warheads to no more than 700.

The long-awaited treaty is a vital symbol of progress in U.S.-Russian relations and an important additional step in the process of reducing and eventually perhaps even achieving the elimination nuclear weapons. It represents a significant arms control milestone that both countries should ratify as soon as possible so they can negotiate deeper cuts.

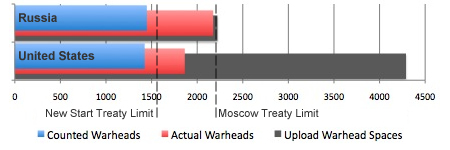

Yet while the treaty reduces the legal limit for deployed strategic warheads, it doesn’t actually reduce the number of warheads. Indeed, the treaty does not require destruction of a single nuclear warhead and actually permits the United States and Russia to deploy almost the same number of strategic warheads that were permitted by the 2002 Moscow Treaty.

The major provisions of the New START Treaty are:

- 1,550 deployed strategic warheads: Warheads on deployed ICBMs and deployed SLBMs count toward this limit and each deployed heavy bomber equipped for nuclear armaments counts as one warhead toward this limit.

- A limit of 700 deployed ICBMs, deployed SLBMs, and deployed heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments.

- A limit of 100 non-deployed ICBM launchers (silos), SLBM launchers (tubes), and heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments.

These limits don’t have to be met until 2017, and will remain in effect for three years until the treaty expires in 2020 (assuming ratification occurs this year). Once it is ratified, the 2002 Moscow Treaty (SORT) falls away.

Verification Extended

The most important part of the new treaty is that it extends a verification regime at least a decade into the future. The inspections and other verification procedures in this Treaty will be simpler and less costly to implement than the old START treaty, according to the White House.

This includes on-site inspections. Each side gets a total of 18 per year, ten of which are actual warhead counts of deployed missiles and the remaining eight being “Type 2” inspections of storage and dismantlement facilities.

Exchange of missile test telemetry data has been limited partly because it is not as necessary for verification as previously; there are other means for collecting this information. Even so, the treaty includes exchange of telemetry data for five test flights each year.

The Fine Print: Limits Versus Reductions

The White House fact sheet states that the new limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads is 74% lower than the 6,000 warhead limit of the 1991 START Treaty, and 30% lower than the 2,200 deployed strategic warhead limit of the 2002 Moscow Treaty.

That is correct, but the limit allowed by the treaty is not the actual number of warheads that can be deployed. The reason for this paradox is a new counting rule that attributes one weapon to each bomber rather than the actual number of weapons assigned to them. This “fake” counting rule frees up a large pool of warhead spaces under the treaty limit that enable each country to deploy many more warheads than would otherwise be the case. And because there are no sub-limits for how warheads can be distributed on each of the three legs in the Triad, the “saved warheads” from the “fake” bomber count can be used to deploy more warheads on fast ballistic missiles than otherwise.

| Under the New START Treaty That’s One Nuclear Bomb! |

|

| The New START Treaty counts each nuclear bomber as one nuclear weapon even though U.S. and Russian bombers are equipped to carry up to 6-20 weapons each. This display at Barksdale Air Base shows a B-52 with six Air Launched Cruise Missiles, four B-61-7 bombs, two B83 bombs, six Advanced Cruise Missiles (now retired), and eight Air Launched Cruise Missiles. Russian bombers can carry up to 16 nuclear weapons. |

.

The Moscow Treaty attributed real weapons numbers to bombers. The United States defined that weapons were counted as “operationally deployed” if they were “loaded on heavy bombers or stored in weapons storage areas of heavy bomber bases.” As a result, large numbers of bombs and cruise missile have been removed from U.S. bomber bases to central storage sites over the past five years, leaving only those bomber weapons that should be counted against the 2,200-warhead Moscow Treaty limit.

Since the new treaty attributes only one warhead to each bomber, it no longer matters if the weapons are on the bomber bases or not; it’s the bomber that counts not the weapons. As a result, a base with 22 nuclear tasked B-52 bombers will only count as 22 weapons even though there may be hundreds of weapons on the base.

According to U.S. officials, the United States wanted the New START Treaty to count real warhead numbers for the bombers but Russia refused to prevent on-site inspections of weapons storage bunkers at bomber bases. As a result, the 36 bombers at the Engels base near Saratov will count as only 36 weapons even though there may be hundreds of weapons at the base.

If the New START Treaty counting rule is used on today’s postures, then the United States currently only deploys some 1,650 strategic warheads, not the actual 2,100 warheads; Russia would be counted as deploying about 1,740 warheads instead of its actual 2,600 warheads. In other words, the counting rule would “hide” approximately 450 and 860 warheads, respectively, or 1,310 warheads. That’s more warheads that Britain, China, France, India, Israel, and Pakistan possess combined!

| Dodging The Issue |

|

|

Update March 30: Ellen Tauscher, the U.S. Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security, was asked at a press briefing to explain the rationale behind the “fake” bomber warhead counting rule, but dodged the issue: “Well, I think what we want to do right now is talk about why this is an important treaty….” Increased transparency of bomber weapons would greatly improve the importance of the new treaty; the U.S. and Russia have more bomber warheads than the total nuclear weapon inventory of all other nuclear weapon states combined. If they have to use an arbitrary bomber warhead number because it’s too hard to verify, why chose 1? Why not 10 (as START I did) or 12, the medium loading capacity of U.S. and Russian bombers? |

The paradox is that with the “fake” bomber counting rule the United States and Russia could, if they chose to do so, deploy more strategic warheads under the New START Treaty by 2017 than would have been allowed by the Moscow Treaty by 2012.

Force Structure Changes

How the new treaty and the “fake” counting rule will affect U.S. and Russian nuclear force structures depends on decisions that will be made in the near future. In the negotiations both Russia and the United States resisted significant changes to their nuclear forces structures.

Russia resisted restrictions on warheads numbers to keep some degree of parity with the United States. It achieved this by the “fake” bomber weapon count and the delivery platform limit that is higher than what Russia deploys today. Under the New START Treaty, Russia can deploy more strategic warheads on its ballistic missiles than it would have been able to under the Moscow Treaty, although it probably won’t do so due to retirement of older systems. It can continue all its current and planned force structure modernizations.

The United States resisted restrictions on its upload capability, which it achieved by the high limit on delivery platforms. The “fake” bomber count enables more weapons to be deployed on ballistic missiles and more weapons to be retained at bomber bases than would have been possible under the Moscow Treaty. The SLBM-heavy (in terms of warheads) U.S. posture “eats up” a large portion of the 1,550 warhead limit, so the U.S. Nuclear Posture Review soon to be completed will probably reduce the warhead loading on each SLBM, and possible cut about 100 missiles from the ICBM force. The incentive to limit bomber weapons further is gone with the new treaty, although it could happen for other reasons. All current and planned modernizations can continue.

Although Russia has thousands of extra weapons in storage, all its deployed missiles are thought to be loaded to near capacity. As a result, under the New START Treaty, Russia will have little upload capacity. The United States, on the other hand, has only a portion of its available warheads deployed and lots of empty spaces on its missiles. The large pool of reserve warheads available for potential upload creates a significant disparity in the two postures so it is likely that the Nuclear Posture Review will reduce the size of the reserve.

| Estimated U.S. and Russian Strategic Warheads, 2017 |

|

| Although the New START Treaty reduces the limit for deployed strategic warheads, a “fake” bomber weapon counting rule enables both countries to continue to deploy as many weapons as under the Moscow Treaty. A high limit for delivery vehicles protects a significant U.S. upload capacity, whereas Russia will have essentially none. Future force structure decisions might affect the exact numbers but this graph illustrates the paradox. |

.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The New START Treaty is an important achievement in restarting relations with Russia after the abysmal decline during the Bush administration. And extending and updating the important verification regime creates a foundation for transparency and confidence building.

The treaty will also, if ratified quickly and followed up by additional reductions, assist in strengthening the international nonproliferation regime and efforts to prevent other countries from developing nuclear weapons.

The United States and Russia must be careful not to “oversell” the treaty as creating significant reductions in nuclear arsenals and strategic delivery systems. Although the treaty reduces the limit, the achievement is undercut by a new counting rule that enables both countries to deploy as many strategic warheads as under the Moscow Treaty.

Indeed, the New START Treaty is not so much a nuclear reductions treaty as it is a verification and confidence building treaty. It is a ballistic missile focused treaty that essentially removes strategic bombers from arms control.

The good news is that a modest treaty will hopefully be easier to ratify.

Because the treaty protects current force structures rather than reducing them, it will inevitably draw increased attention to the large inventories of non-deployed weapons that both countries retain and can continue to retain under the new treaty. Whereas the United States force structure is large enough to permit uploading of significant numbers of reserve warheads, the Russian force is too small to provide a substantial upload capacity. Even with a significant production of new missiles, it is likely that Russia’s entire Triad will drop to around 400 delivery vehicles by 2017 – fewer than the United States has today in its ICBM leg alone. That growing disparity makes it imperative that the forthcoming U.S. Nuclear Posture Review reduces the number of delivery vehicles and reserve warheads.

To that end it is amazing to hear some people complaining that the U.S. deterrent is dilapidating and that the United States doesn’t gain anything from the New START Treaty. In the words of one senior White House official, the United States came away as a “clean winner.”

Because the treaty does not force significantly deeper reductions in the number of nuclear weapons compared with the Moscow Treaty, it is important that presidents Obama and Medvedev at the signing ceremony in Prague on 8 April commit to seeking rapid ratification and achieving additional and more drastic nuclear reductions.

See also Ivan Oelrich’s blog.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

CTBT ratification and fact-twisting arguments

By: Alicia Godsberg

On Friday, February 5 the EastWest Institute (EWI) held a seminar at their office in New York to discuss its recently released report on the CTBT, entitled, “The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty: New Technology, New Prospects?” Speaking at the event for the pro-CTBT ratification camp was Ambassador Robert T. Grey, Jr. (Director, Bipartisan Security Group and U.S. Representative to the Conference on Disarmament from 1998-2001) and against was Stephen Rademaker (Senior Council, BGR Government Affairs and Assistant Secretary of State from 2002-2006). The seminar also hosted many representatives of the NGO disarmament community as well as several diplomats from UN missions, including from Iran, Egypt, and South Korea.

Mr. Rademaker articulated familiar reasons for opposing U.S. ratification of the CTBT: it won’t ensure entry into force of the Treaty; the Treaty is unverifiable; the U.S. may need to test in the event the nuclear weapon stockpile becomes unreliable; there is no agreed definition of a “zero yield” nuclear test; and Russia (and possibly China) does not conform to the U.S. definition of absolutely zero yield, enabling them to benefit from such tests while the U.S. adheres to a stricter standard and (presumably) falls behind in knowledge. The fact that each of these assertions has been proven untrue does not stop these talking points from surfacing at every turn. (more…)

Changing the Nuclear Posture: moving smartly without leaping

Release of the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) is delayed once again. Originally due late last year, in part so it could inform the on-going negotiations on the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty Follow-on (START-FO), after a couple of delays it was supposed to be released today, 1 March, but last week word got out that it will be coming out yet another 2-4 weeks later. Some reports are that the delay reflects deep divisions within the administration over the direction of the NPR. That means that there is really only one person left whose opinion matters and that is the president.

We can only hope that President Obama makes clear that he meant what he said in Prague and elsewhere. This NPR is crucial. If it is incremental, if it relegates a world free of nuclear weapons to an inspiring aspiration, then we are stuck with our current nuclear standoff for another generation. This is the time to decisively shift direction. But we should not be paralyzed by thinking that the only movement available is a giant leap into the unknown. We need to move decisively in the right direction, sure, but we can do that in steps. (more…)

Missile Watch – February 2010

Missile Watch

A publication of the FAS Arms Sales Monitoring Project

Vol. 3, Issue 1

February 2010

Editor: Matt Schroeder

Contributing Author: Matt Buongiorno

Graphics: Alexis Paige

Contents:

Afghanistan: No recent discoveries of shoulder-fired, surface-to-air missiles in insurgent arms caches

Eritrea: UN slaps arms embargo on major missile proliferator

Iraq: Fewer public reports of seized shoulder-fired missiles in Iraq, but MANPADS still a threat

Ireland: Alleged plot to shoot down a police helicopter may have involved surface-to-air missile

Myanmar: 300 shoulder-fired missiles in insurgent arsenal, claims Thai Colonel

North Korea: North Korean arms shipment included MANPADS, Thai report confirms

Peru: Igla missiles stolen from Peruvian military arsenals, claims alleged trafficker

Spain: Failed assassination attempts underscore the risks for terrorists of relying on black market missiles

United States: Congress to receive DHS report on anti-missile systems for commercial airliners in February

United States: Documents from trial of the “Prince of Marbella” reveal little about his access to shoulder-fired missiles

United States: No new international MANPADS sales since 1999

Venezuela: U.S. receives “assurances” from Russia regarding controls on shoulder-fired missiles sold to Venezuela, but questions remain

This issue of Missile Watch features big news out of Thailand. A North Korean arms shipment seized by Thai officials in December contained “five crates of MANPADS SAM[s]”, according to an official Thai government report. The report, which was obtained by Bloomberg News in late January, appears to confirm North Korea as an illicit source of shoulder-fired, surface-to-air missiles. Depending on the origins and model of the missiles, this case could have profound implications for international efforts to curb missile trafficking. Also notable are reports of a Peruvian trafficking ring that stole at least seven Strela and Igla missiles from government arsenals and sold them to Colombian rebels, and of insurgent arsenals in Myanmar that contain 300 missiles – a stockpile comparable in size to the holdings of many small states. These reports illustrate the continued availability of illicit missiles to armed groups despite a decade-long international campaign to strengthen export controls and secure government stockpiles.

The news isn’t all bad, however. Recent reports suggest that most armed groups continue to rely – often clumsily – on older first-generation infra-red seeking missiles, which are difficult to use effectively and often malfunction, as evidenced by the Basque terrorist group ETA’s failed attempts to shoot down the Spanish Prime Minister’s plane in 2001. This is not the first failed terrorist missile attack, and it will not be the last. In 2002, for example, an al-Qaeda affiliated group in Kenya armed with two SA-7b missiles missed an Israeli airliner as it was leaving Mombasa. The more of these spectacular failures that come to light, the less demand there will be amongst armed groups for first and second generation missiles. Or at least that is the hope. In those comparatively rare cases when terrorists are able to acquire and effectively use newer missiles, modern anti-missile technology may provide an effective last line of defense, as illustrated by the recent “multiple IR engagement” thwarted by the missile defense system on a Chinook helicopter reportedly operating in Iraq.[1] Whether this last line of defense will be extended to commercial airliners will be determined, in part, by Congress’ reaction to Department of Homeland Security’s long-awaited report on its Counter-MANPADS program, which will be delivered to key congressional committees this month.

Also encouraging are recent actions taken against missile trafficking and the governments that facilitate it. The same month that the Thai government moved against missile trafficking in their country, the UN Security Council imposed an arms embargo on Eritrea, the supplier of thousands of weapons, including surface-to-air missiles, to the militant Somali group al Shebab. The embargo comes none too soon. A spokesman for the group recently threatened to come to the aid of their “Muslim brothers” in Yemen,[2] an apparent reference to the al Qaeda affiliate responsible for the failed attack on the US-bound airliner in December. Extensive involvement in Yemen’s civil war by al Shebab would be very bad for the Yemeni government and its western allies, especially if the militants bring their missiles. It remains to be seen if the embargo will motivate Eritrea to stop arming Somali militants, or at least stop arming them with sophisticated light weapons.

Country Reports

Afghanistan: No Recent Discoveries of Shoulder-fired Antiaircraft Missiles in Insurgent Arms Caches, Confirms ISAF Spokesperson

Afghanistan: No Recent Discoveries of Shoulder-fired Antiaircraft Missiles in Insurgent Arms Caches, Confirms ISAF Spokesperson

No MANPADS were found in seized insurgent arms caches in late 2009, according to the US military. A spokesperson from the International Security Assistance Force Joint Command (IJC) told the Federation of American Scientists that “[t]he ISAF Joint Command intelligence section is not aware of any man-portable surface-to-air missile finds by ISAF units since the IJC’s inception in October 2009.”[3] To date, the ISAF has largely been spared the problems associated with the widespread proliferation of surface-to-air missiles that has plagued Coalition forces operating in Iraq (see Missile Watch #3: Black Market Missiles Still Common in Iraq).

While the reasons for the difference in illicit missile activity in Iraq and Afghanistan are not entirely clear, one likely factor is availability. Shortly after the US invasion, hundreds of missiles were looted from unsecured arms depots scattered across Iraq. Much of the looting, notes Government Accountability Office in a 2007 report, “…was conducted by organized elements that were likely aided or spearheaded by Iraqi military personnel,”[4] – future members of insurgent groups. There is no comparable domestic source of missiles for the Taliban. The absence of a convenient domestic source would not preclude acquisition of shoulder-fired missiles on the international black market, however, and there is strong evidence that the Taliban has acquired missiles – namely Chinese HN-5s – from sources abroad, but their numbers appear to be limited. The extent to which these missiles have been used against ISAF aircraft is unknown. Publicly available information on insurgent activity suggests, however, that few if any of the missiles have been used successfully.

Eritrea: UN Slaps Arms Embargoes on Major Missile Proliferator

Eritrea: UN Slaps Arms Embargoes on Major Missile Proliferator

After years of supplying weapons to Somali militants in violation of UN Security Council resolutions, the UN has slapped an arms embargo on the government of Eritrea. Resolution 1907, which was approved by a 13-1 vote in the Security Council in December,[5] imposes a ban on the international transfer of arms to and from Eritrea. It also authorized UN member states to inspect cargo crossing their territory if a violation is suspected, and to seize and dispose of any illicit weapons that are discovered.

Eritrea ranks high on the list of MANPADS proliferators. In recent years, UN investigators have documented shipments containing dozens of MANPADS from Eritrea to Somalia in violation of a long-standing UN arms embargo. In 2007, an SA-18 missile “delivered by Eritrea,” according to UN investigators,[6] was used by Somali militants to shoot down a Belarusian cargo aircraft departing from Mogadishu. The Eritrean government has denied the accusations, but additional evidence collected by investigators in recent years appears to support the earlier claims. An SA-18 Igla missile “found in Somalia” by UN investigators, for example, was later traced back to a shipment of Russian weaponry delivered to Eritrea in 1995.[7]

Iraq: Fewer public reports of seized shoulder-fired missiles in Iraq, but MANPADS still a threat

Iraq: Fewer public reports of seized shoulder-fired missiles in Iraq, but MANPADS still a threat

Publicly available reports of shoulder-fired, surface-to-air missiles discovered in insurgent arms caches in Iraq dropped off precipitously in 2009, but the reason for this decline is unclear. A survey of English-language media and US military sources yielded information on only a handful of illicit MANPADS recovered from arms caches in 2009, as opposed to dozens in previous years (See Missile Watch #3: Black Market Missiles Still Common in Iraq). Given the rigor of US and Iraqi efforts to recover illicit weapons and dismantle arms trafficking networks, it is possible that terrorists and insurgents did indeed have access to fewer missiles in 2009. It is also possible, however, that seized MANPADS simply are not being reported as frequently, possibly for security reasons. When queried about the apparent decrease, a representative from Multi-National Forces-Iraq declined to comment, saying only that “[f]or operational security, we are unable to provide such details…”[8]

Regardless of the reason for the decline in reported seizures, MANPADS remain a threat in Iraq, as evidenced by a recent incident in which a Chinook military helicopter was engaged by “multiple IR MANPADS.” The attack, which was first reported by Aviation Week’s David Fulghum, was reportedly thwarted by the helicopter’s anti-missile system.[9]

Ireland: Alleged plot to shoot down a police helicopter may have involved surface-to-air missiles

Ireland: Alleged plot to shoot down a police helicopter may have involved surface-to-air missiles

In December, the Belfast Telegraph reported that “[d]issident republicans” had obtained an unspecified surface-to-air missile and were “…planning to use it to shoot down a helicopter full of police officers…” The article provides no additional details on the missile or the alleged plot, although an unidentified “police source” suggests that the “missile” may instead be a rocket-propelled grenade: “They [the dissidents] have access to rocket-propelled grenades or other surface-to-air missile [sic] and one of their priorities is to take out a helicopter.”[10] The Irish government and the Independent Monitoring Commission declined to comment on the story, and an email to the author of the Telegraph article went unanswered.

Too little information is available to assess the accuracy of the Telegraph’s claims. Yet even if Irish dissidents have access to a missile, a successful attack is far from guaranteed. Like many terrorist and insurgents worldwide, armed groups in Ireland have a long, largely unsuccessful history of illicit activity involving shoulder-fired missiles. Repeated attempts by the IRA to acquire Stinger missiles in the United States ended in jail time for many of the would-be missile traffickers,[11] and even when the group succeeded in procuring missiles with help of the Libyan government,[12] the IRA never effectively incorporated the missiles into its campaign against the British.[13] In the late 1990s, the group reportedly supplied some of its missiles to the Basque group ETA, who also failed to use them effectively (See below: “Spain: Alleged ETA member reveals details of failed attempts to assassinate Spanish prime minister”).

Myanmar: 300 shoulder-fired missiles in insurgent arsenal, claims Thai Colonel

Myanmar: 300 shoulder-fired missiles in insurgent arsenal, claims Thai Colonel

A Thai military official interviewed by the International Herald Tribune in November claimed that the United Wa State Army, a Burmese insurgent group, possesses 300 “shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missiles”[14] – a stockpile that is comparable in size to those of many small states. No additional details on the missiles were provided.

According to Jane’s Information Group, the Wa’s missile holdings consist of older SA-7s acquired in the early 1990s from “Cambodian black market sources,” and more sophisticated HN-5Ns from China.[15] These reports appear to be a decade old, however, so it is possible that the composition of the Wa’s current missile stockpile is very different.

If Colonel Peeranate’s estimate is accurate and the missiles are operational, the Wa’s missile stockpile is one of the largest non-state arsenals in the world. Little is known about the security of the Wa’s weapons, but the general lack of accountability and formal controls on insurgent arms caches and the size of the stockpile raises concerns about theft, loss and diversion, and the possibility that some of the missiles will end up on the black market.

North Korea: North Korean arms shipment included man-portable air defense systems, Thai report confirms

North Korea: North Korean arms shipment included man-portable air defense systems, Thai report confirms

The Federation of American Scientists has learned that a cargo plane loaded with weapons from North Korea that was grounded in Bangkok in December contained man-portable air defense systems. According to a Thai report to the UN Security Council obtained by Bloomberg in January, the cargo contained “five crates of MANPADS SAM[s]”. The manufacturer, model and year of the MANPADS are not identified.[16] This information is required to fully assess the implications of the seizure, and to craft strategies for preventing similar shipments.

It is possible that the missiles were manufactured in North Korea, which has produced the Chinese HN-5 and the Soviet SA-14 and SA-16 under license,[17] and the Soviet SA-7 and US Stinger missile, which it reverse-engineered from missile technology acquired from Egypt in the 1970s and from the Afghan Mujahideen in the 1980s, respectively.[18] Another possibility is that the missiles were foreign-made and were transiting through, or were re-exported from, North Korea. This scenario could also have profound implications, depending on the origin and age of the missiles. Newly manufactured foreign missiles would suggest a recent government-to-government sale to North Korea – an egregious violation of the spirit if not the letter of international agreements on controlling MANPADS – or diversion from government stockpiles, which would likely be indicative of serious shortcomings in stockpile security policies and practices.

North Korea as a source of illicit MANPADS poses a significant challenge for policymakers since few if any of the diplomatic carrots and sticks used to secure MANPADS elsewhere would be effective vis-a-vis the Hermit Kingdom. Interdiction efforts associated with UN Security Council Resolution 1874 will likely make it more difficult to traffic in weaponry from North Korea, but shoulder-fired missiles are easy to smuggle, and adequately screening the contents of every plane and ship departing from North Korea would be impossible. The best that can reasonably be hoped for is that vigilance by North Korea’s neighbors and robust patrolling of international waters will limit North Korea’s arms smuggling in the near term, and that prioritization of the MANPADS proliferation threat by the six-party nations in negotiations with North Korean officials will yield a longer term solution.

The Thai report identifies Mahrabad Airport in Iran as the aircraft’s destination, although Thai officials have subsequently stated that Sri Lanka and the United Arab Emirates were also listed as stops in the flight documentation.[19] The Iranians have denied any involvement in the transfer, pointing out that they have no need for the shipment since Iran’s defense industry produces its own “modern weapons”.[20] But it is possible that the Iranians had ordered the weapons not for their own use but for their proxies in Lebanon or elsewhere. Foreign missiles would allow the Iranians to provide like-minded armed groups with much-needed air defense systems while maintaining plausible deniability regarding their role in the transfer. A similar strategy was pursued by the United States during the clandestine campaign to arm and train the Afghan Mujahideen during the Soviet occupation.[21] If the North Korean weapons were bound for Iran, they may have been intended for a similar purpose.

Peru: Igla missiles stolen from Peruvian Military, claims alleged trafficker

Peru: Igla missiles stolen from Peruvian Military, claims alleged trafficker

A self-proclaimed “logistics specialist” for Colombian rebels reportedly obtained seven Stela and Igla surface-to-air missiles from the arsenals of the Peruvian military according to the Miami Herald and the Lima-based La Republica newspaper. Ecuadorian national Freddy Torres allegedly acquired the missiles, along with other weapons, from a trafficking ring comprised of members of the Peruvian air force, army and police.[22] Four of the missiles were purchased between May and October 2008 and the remaining three were purchased in 2009, according to Juan Tamayo of the Miami Herald. Each of the missiles was reportedly purchased for “the sum of 45,000 US dollars.”[23]

Assuming man-portable Strela and Igla missiles were indeed stolen from Peruvian arsenals and sold to Colombian rebels, this case could have significant implications. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) has tried unsuccessfully for years to acquire missiles capable of countering the Colombian armed forces growing fleet of fixed and rotary-wing aircraft, which are critical to its counter-insurgency operations. While a handful of Strela and Iglas will not turn the tide of the war in the FARC’s favor, the missiles could be very disruptive to Colombian air operations, at least in the short term.

Of greater consequence is the potential terrorist threat from the missiles. In the hands of a trained operator, a well-maintained missile poses a significant threat to civilian planes, including airliners; at least 45 civilian aircraft have been shot down by man-portable air defense systems worldwide since 1975.[24] The missiles are of significant value to the FARC’s war against the Colombian government and therefore the rebels are unlikely to use the missiles against commercial airliners. However, they could be used against high-value civilian targets such top government or military officials. The missiles could also be stolen or sold on the black market, where they would they could be acquired by terrorists with designs on an airliner.

The missile theft is also a critical test of the region’s commitment to combating the shoulder-fired missile threat. In 2005, the 35 members of the Organization of American States (OAS) adopted AG/RES.2145, a set of guidelines that urges member states to, inter alia, “…adopt and maintain strict national controls and security measures on Man-Portable Air Defense Systems and their essential equipment.” These guidelines include specific, rigorous stockpile security measures, such as separate storage of missiles and launchers, 24-hour surveillance, and strict controls on access to missiles.[25] The diversion of multiple missiles over a period of months raises serious questions about the Peruvian government’s implementation of these guidelines and the security of the rest of its missile stockpile, which numbers in the hundreds, according to Jane’s Information Group.[26] A robust response to this incident would show the region and the world that the OAS and its member states take the illicit trade in terrorist technology seriously and are willing to match rhetoric with action.

Spain: Failed assassination attempts underscore the risks for terrorists of relying on black market missiles

Spain: Failed assassination attempts underscore the risks for terrorists of relying on black market missiles

Intelligence obtained from an alleged member of the Basque terrorist group ETA revealed three failed attempts to shoot down the Spanish prime minister’s plane with a shoulder-fired, surface-to-air missile acquired from the Irish Republican Army in 1999. According to the Telegraph, the plots came to light after the arrest of the suspected ETA member, who reportedly told Spanish investigators that the group had tried three times in April and May 2001 to shoot down the plane but that the missile had malfunctioned each time. A letter addressed to the IRA discovered in the suspect’s home reportedly complains about defective missiles allegedly sold to ETA by IRA members based in Germany.[27] The missiles were seized from an ETA arms cache by French authorities in 2004.[28]

Media reports do not indicate whether authorities believe that the missiles used in the botched attack was indeed faulty or was used incorrectly. Contrary to popular belief, shoulder-fired missiles aren’t simply point-and-shoot weapons; they require training to use effectively, and it is not clear what training, if any, ETA members received in the operation of the missiles. Regardless of the reason for the failed attacks, this case underscores the risks for terrorists of relying on black market missiles, especially when the missiles are first generation technology that is nearing the end (or is past) its estimated shelf life and may have been tampered with or stored improperly. It is hoped that ETA’s bumbling – along with other spectacular failures like the unsuccessful missile attack on an Israeli airliner in Kenya in 2002 – will reduce black market demand for the most widely available (i.e. first generation) shoulder-fired missiles as terrorists recognize the folly of planning high-profile attacks around weapon systems that they do not fully understand and that may not function properly.

United States: Congress to receive DHS report on anti-missile systems for commercial airliners in February

United States: Congress to receive DHS report on anti-missile systems for commercial airliners in February

The Federation of American Scientists has learned that a long-awaited report on the feasibility of installing anti-missile systems on commercial airliners is nearly finished, and will be delivered to Congress in February. “The report is nearing the end of review; we are still expecting a February delivery to Hill staff,” a DHS spokesperson confirmed in a correspondence with the Federation of American Scientists. The report, which will be sent to the House and Senate Appropriations Committees, summarizes the results of a program launched in 2003 to assess the “…viability, economic costs and effectiveness of adapting existing technology from military to commercial aviation use.” As noted in the last issue of Missile Watch, the response from Congress to the report will be a critical indicator of whether its early enthusiasm for outfitting commercial airliners with anti-missile systems – a multi-billion dollar undertaking – has survived DHS’ lengthy evaluation process and a constant barrage of competing agenda items.

United States: Documents from trial of the “Prince of Marbella” contain additional information on shoulder-fired missiles

Court documents recently obtained by the Federation of American Scientists provide some additional insight into the historic case of famed arms trafficker Monzer Al Kassar, but many important questions remain unanswered. In 2007, Kassar was arrested after allegedly agreeing to sell thousands of weapons, including shoulder-fired, surface-to-air missiles, to undercover informants posing as members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). A year later, Kassar was extradited to the United States and tried in New York, where he was convicted of, inter alia, conspiring to “acquire and export anti-aircraft missiles.”[29] The surprising arrest and conviction of Kassar brought an abrupt end to the career of one of the most prolific traffickers in recent history. According to the US government, clients of Kassar’s have included armed groups in Bosnia, Brazil, Croatia, Cyprus, Iraq, Iran, and Somalia, among others.[30]

Hundreds of court documents obtained by the Federation of American Scientists provide additional insight into the case, including Kassar’s offer to sell MANPADS to Colombian rebels. Summaries of phone conversations between Kassar and the DEA informants indicate that Kassar “…spoke about various types of surface-to-air missile systems– including SAM-7s, SAM-16s, and SAM-18s – and the systems’ respective abilities to destroy U.S. helicopters.” Previously released documents only reference the SA-7, a first generation Soviet-era missile that is easier to acquire and less capable than the SA-16 and SA-18. However, none of the documents reveal whether Kassar actually had access to the missiles, or – if he did – how many he had or where he acquired them. The Federation of American Scientists will continue to research these questions and report any additional findings in future issues of Missile Watch.

United States: No New International MANPADS Sales since 1999, says Raytheon

A spokesperson for the US defense firm Raytheon recently told the Federation of American Scientists that the U.S. government has not entered into new deals for Stinger MANPADS with foreign clients since 1999. In an email correspondence, Raytheon official Ty Blanchard told said that “[s]ince 1999, the U.S. government has denied requests from non-NATO countries asking for Stinger MANPADS. We have not had any requests from NATO countries in the last ten years.”[31]

This record of restraint illustrates the disparity in the policies of the major arms exporting states. Even as the US has curtailed international sales of man-portable Stingers, other countries have sold advanced systems to governments with dubious stockpile security and end-use controls.[32] Failure to align the policies of exporting countries could erode nascent global standards for MANPADS exports and undo much of the progress toward eliminating the terrorist missile threat achieved to date.

Venezuela: U.S. receives “assurances” from Russia regarding controls on shoulder-fired missiles sold to Venezuela, but key questions remain

Venezuela: U.S. receives “assurances” from Russia regarding controls on shoulder-fired missiles sold to Venezuela, but key questions remain

The Federation of American Scientists has learned that US officials have received “assurances” from the Russian government regarding end-use controls on SA-24 MANPADS sold to Venezuela, but detailed information on the nature and implementation of these controls remain scant. This information is critical to determining whether the SA-24s and the “thousands” of additional missiles[33] that Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez claims to be importing are in danger of being diverted to armed groups in the region or elsewhere.

In response to a query about the sale, a State Department spokeswoman told the Federation of American Scientists that U.S. officials “…have expressed our concerns to the Russian government on the control and security of arms transferred to Venezuela” and that they have “…received assurances from the Russian government that the deal conforms with end-use controls that meet international standards.”[34] The official did not indicate whether Russia has provided the US government with a list of specific controls, or the extent to which these controls have been implemented. The Russian and Venezuelan governments have yet to respond to requests from the Federation of American Scientists for additional information.

The most prominent set of ‘international standards’ on MANPADS controls are the Elements for Export Controls of MANPADS. Under the Elements, Russia has agreed to “…satisfy itself of the recipient government’s willingness and ability to implement effective measures for secure storage, handling, transportation, use of MANPADS material, and disposal or destruction of excess stocks to prevent unauthorised access and use.”[35] A more detailed set of procedures is laid out in an annex to the OSCE’s Best Practice Guide on National Procedures for Stockpile Management and Security of MANPADS, which the Russian government helped to draft. Minimally, the Russian government should ensure that Venezuela’s stockpile security and end-use policies and practices conform to the Wassenaar Arrangement’s Elements and the OSCE’s Best Practice Guide, and the Organization of American States’ Guidelines for Control and Security of MANPADS. Given the history of diversion from Venezuela’s arsenals,[36] regular on-site inventories and inspections by Russian officials are also merited. Failure to take these steps would raise serious questions about the Russian government’s commitment to implementing key international agreements and guidelines, including guidelines it helped to draft.

Additional News & Resources (11/ 2009- 1/2010)

- “Sarachandran jailed for 26 years for trying to aid Tamil Tigers,” National Post, 23 January 2010.

- “Helo-Protecting Advanced Sensors Hurried,” Aviation Week, 21 January 2010.

- “More Advanced SAMs Emerging in Combat Zones,” Aviation Week, 13 January 2010.

- “Missile defense: post DHS,” Avionics Intelligence, 7 January 2010.

- “R.O. CONGO: 750,000 dangerous items demolished in two years,” Mines Advisory Group, 11 December 2009.

- “Albanian Press Review – December 1,” Balkan Insight, 1 December 2009. The article includes a brief reference to an article in the Albanian newspaper Gazeta Tema about alleged transfers of MANPADS from Albania to Hezbollah. The full article is available on Gazeta Tema’s website, but it is in Albanian.

- “Cyprus Confronts Its MANPADS Menace,” OSCE Magazine,December 2009.

- “Powder Keg – Unfettered arms flows reflect Sudan’s instability,” Jane’s Intelligence Review, December 20009. The article includes a brief reference to the recent acquisition of SA-16 missiles by the SPLA.

- “Somali pirates seize Maran Centaurus oil tanker sailing from Saudi Arabia,” Times Online, 30 November 2009. The article includes a brief reference to reports of pirates using shoulder-fired, surface-to-air missiles. The report is probably in the Korea Times that the pirates had acquired Stinger missiles from al Qaeda. Missile Watch has been unable to substantiate these claims.

- “Arrests Made in Case Involving Conspiracy to Procure Weapons, Including Anti-Aircraft Missiles,” US Department of Justice, 23 November 2009.

- “Protecting Civil Aviation from MANPADS,” Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, 23 November 2009.

- “CSTO member nations coordinate positions on SALW and MANPADS”, Asia Plus, 20 November 2009.

Matt Schroeder is the Manager of the Arms Sales Monitoring Project at the Federation of American Scientists. Since joining FAS in February 2002, he has written more than 80 books, articles and other publications on US arms transfers, arms export policies, and the illicit arms trade. He is a co-author of the book The Small Arms Trade (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2007), and a consultant for the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey.

Matt Buongiorno is currently serving as a Scoville Fellow at the Federation of American Scientists where he is working on small arms issues, U.S. nuclear policy issues, and Iranian nuclear issues. In addition to his work with FAS, Matt is staffing the 2010 National Model United Nations, a conference in New York that draws over 4,000 students and aspiring diplomats. He earned a B.A. in economics and political science from Texas Christian University in 2009.

Missile Watch is a quarterly publication by the Arms Sales Monitoring Project at the Federation of American Scientists that tracks the illicit proliferation and use of man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS), and international efforts to combat the terrorist threat from shoulder-fired missiles.

To sign up for Missile Watch, go to /press/subscribe.html.

[1]David Fulghum, “Laser Saves Helo in Multi-SAM Ambush,” Aviationweek.com, 7 January 2010.

[2]“Yemen slams Shebab pledge to send fighters,” AFP, 2 January 2010.

[3]Correspondence with Major Steve Cole, spokesman for the IJC, 5 January 2010.

[4]DOD Should Apply Lessons Learned Concerning the Need for Security over Conventional Munitions Storage Sites to Future Operations Planning, Government Accountability Office, March 2007, p. 7.

[5]Colum Lynch, “U.N. Security Council orders arms embargo on Eritrea,” The Washington Post, 24 December 2009.

[6]Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia, S/2007/436, 18 July 2007, p. 15.

[7]Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia, S/2008/274, 24 April 2008, p. 24-25.

[8]Correspondence with MNF-Iraq, 19 November 2009. FOIA requests for similar information have also been denied. In January, US Central Command denied the release of six documents responsive to a Freedom of Information Act request filed by the FAS for information on “man-portable air defense systems collected or seized by Iraqi Security Forces or Coalition forces from 1 January 2007 to 1 June 2008.”

[9]David Fulghum, “Laser Saves Helo in Multi-SAM Ambush,” Aviationweek.com, 7 January 2010. While US Army officials did not identify the location of the attack, “…other military sources indicate it was in Iraq,” according to Fulghum.

[10]Deborah McAleese, “New Dissident Target…a Police Helicopter; Plan to Blast Lightly-armoured PSNI Chopper out of the Sky,” Belfast Telegraph, 2 December 2009.

[11]See Schroeder, Stohl and Smith, The Small Arms Trade (Oneworld Publications, 2007), p. 98-103.

[12]Smuggling efforts involving Libya were more fruitful. In the 1970s and 80s, the group acquired several MANPADS as part of a series of weapons shipments allegedly arranged by the Libyan government. But even these shipments were vulnerable to interdiction. The Eskund, for example, which reportedly contained 150 tons of weaponry, including 20 SA-7 missiles, was seized by French authorities in 1987.

[13]See Ian Bruce, “Why They’re Never Short of a Gun,” The Herald (Glasgow), 26 January 1998.

[14]“A Rebel Stronghold in Myanmar on Alert,” International Herald Tribune, 6 November 2009.

[15]“United Wa State Army (UWSA),” Jane’s World Insurgency and Terrorism, updated 11 November 2009 and Anthony Davis, “Myanmar heat turned up with SAMS from China,” Jane’s Defense Weekly, 28 March 2001.

[16]Some media reports identified the missiles as Chinese HN-5s, but these claims have not been corroborated.

[17]O’Halloran and Foss, Jane’s Land-based Air Defense 2008-2009 (Cambridge University Press, 2008), p. 22.

[18]O’Halloran and Foss, p. 22 and Schroeder, Stohl, Smith, The Small Arms Trade, p. 88.

[19]Daniel Ten Kate, “Thailand Urges UN Action on N. Korean Arms Cache as Cost Rises,” Bloomberg, 3 February 2010.

[20]“Seized Weapons Plane in Thailand not Heading for Iran: Official,” Tehran Times, 3 February 2010.

[21]The Central Intelligence Agency purchased weapons, including MANPADS, from Eastern European countries and China, refraining from sending more effective US Stinger missile until the final years of the campaign.

[22]Juan Tamayo, “Farc Rebels’ Missile Purchase Raises Concerns,” Miami Herald, 16 February 2010 and “Stolen Peruvian Arms Sold to Colombian Rebels,” EFE, 13 January 2010.

[23]Tamayo, “FARC Rebels’ Missile Purchase Raises Concerns”

[24]US Government data provided to the Federation of American Scientists, January 2010.

[25]Denying MANPADS to Terrorists: Control and Security of MAN-Portable Air Defense Systems, Adopted 7 June 2005, available at /asmp/campaigns/MANPADS/2005/OASmanpads.pdf.

[26]See “Peru,” Jane’s World Armies, posted 8 January 2010.

[27]Fiona Govan, “Spanish PM saved from assassination by faulty IRA missile,” Telegraph, 18 January 2010.

[28]“French police find anti-aircraft missiles in ETA cache,” Associated Press Worldstream, 5 October 2004.

[29]“International Arms Trafficker Monzer al Kassar and Associate Sentenced on Terrorism Charges,” US Attorney’s Office, Southern District of New York, 24 February 2009.

[30]United States of America –v. – Mozer Al Kassar, a/k/a “Abu Munawar,” a/k/a “El Taous,” Tareq Mousa al Gahzi, and Luis Felipe Moreno Godoy, June 2007, p. 1.

[31]Correspondence with Ty Blanchard, Raytheon’s business development manager for army advanced programmes, 2 February 2010.

[32]See, for example, Andrei Chang, “China ships more advanced weapons to Sudan,” UPI Asia, 28 March 2008.

[33]“Chavez: Venezuela acquires thousands of missiles,” Associated Press, 7 December 2009. According to the Associated Press, Chavez claimed in early December 2009 that “[t]housands of missiles…”and rocket launchers, reportedly Russian-made, “…are arriving” in Venezuela, although he did not identify the type of missiles and rockets.

[34]Correspondence with State Department officials, 12 January 2010. The full response from the State Department reads as follows: “Russia is a major supplier of arms to Venezuela. We have expressed our concerns to the Russian government on the control and security of arms transferred to Venezuela. We have received assurances from the Government of Russia that the deal conforms with end-use controls that meet international standards. Particularly given reports of Venezuelan-origin [weapons] surfacing in neighboring countries, we urge the Government of Venezuela to implement strict controls to prevent the diversion of arms and ammunition.”

[35]These measures include monthly physical inventories of all imported missiles and launchers, storage of missiles and launchers in separate locations, continuous (24-hour) surveillance, and limiting storage site access to two people with proper security clearances, among others.

[36]For a partial list of recent reports, see footnote 5 in “Securing Venezuela’s Arsenals,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, 24 August 2009.

Eight Recommendations for Improving Transparency in US Arms Transfers

Transparency is essential for effective congressional and public oversight of arms exports. Without complete and accurate data on the quantity, type and recipients of exported defense articles and services, it is impossible to assess the extent to which arms transfers further national security and foreign policy.

Nuclear Doctrine and Missing the Point.

The government’s much anticipated Nuclear Posture Review, originally scheduled for release in the late fall, then last month, then early February is now due out the first of March. The report is, no doubt, coalescing into final form and a few recent newspaper articles, in particular articles in Boston Globe and Los Angeles Times, have hinted at what it will contain.

Before discussing the possible content of the review, does yet another release date delay mean anything? I take the delay of the release as the only good sign that I have seen coming out of the process. Reading the news, going to meetings where government officials involved in the process give periodic updates, and knowing something of the main players who are actually writing the review, what jumps out most vividly to me is that no one seems to share President Obama’s vision. And I mean the word vision to have all the implied definition it can carry. The people in charge may say some of the right words, but I have not yet discerned any sense of the emotional investment that should be part of a vision for transforming the world’s nuclear security environment, of how to make the world different, of how to escape old thinking. As I understand the president, his vision is truly transformative. That is why he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. His appointees who are developing the Nuclear Posture Review, at least the ones I know anything about, are incredibly smart and knowledgeable, but they are also careful, cautious, and, I suspect, incrementalists who might understand intellectually what the president is saying but don’t feel it (and, in many cases, fundamentally don’t really agree with it). A transformative vision not driven by passion will die. As far as I can see (and, I admit, I am not the least bit connected so perhaps I simply cannot see very far) the only person in the administration working on the review who really feels the president’s vision is the president. Much of what I hear from appointees in the administration has, to me at least, the feel of “what the president really means is…” If the cause of the delay is that yet more time is needed to find compromise among centers of power, reform is in trouble because we will see a nuclear posture statement that is what it is today neatened up around the edges. But if the delay is because the president is not getting the visionary document he demands, delay might be the only hopeful sign we are getting.

Now, onto the possible content of the review: The main question to be addressed by the review is what the nuclear doctrine and policy of the United States ought to be. This has sparked a secondary debate about just how specific any declaration of policy should be and the value of declaratory policy at all.

Some hints coming out of the administration suggest that the new review may explicitly state that the sole purpose of nuclear weapons be specifically limited to countering enemy nuclear weapons, what we and others have called a “minimal deterrence” doctrine. Currently, the United States claims that chemical and biological weapons may merit nuclear attack and that could go away with the current review.

Most reports leaking out from the review participants hint that the NPR almost certainly will not include a declaration that the United States will not be the first to use nuclear weapons. The current U.S. policy is to intentionally maintain ambiguity about how and when we might use nuclear weapons, to keep the bad guys guessing. The new review could keep that basic idea and still be a little less ambiguous around the edges.