Behavioral Economics Megastudies are Necessary to Make America Healthy

Through partnership with the Doris Duke Foundation, FAS is advancing a vision for healthcare innovation that centers safety, equity, and effectiveness in artificial intelligence. Inspired by work from the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) and Arizona State University (ASU) symposiums, this memo explores new research models such as large-scale behavioral “megastudies” and how they can transform our understanding of what drives healthier choices for longer lives. Through policy entrepreneurship FAS engages with key actors in government, research, academia and industry. These recommendations align with ongoing efforts to integrate human-centered design, data interoperability, and evidence-based decision-making into health innovation.

By shifting funding from small underpowered randomized control trials to large field experiments in which many different treatments are tested synchronously in a large population using the same objective measure of success, so-called megastudies can start to drive people toward healthier lifestyles. Megastudies will allow us to more quickly determine what works, in whom, and when for health-related behavioral interventions, saving tremendous dollars over traditional randomized controlled trial (RCT) approaches because of the scalability. But doing so requires the government to back the establishment of a research platform that sits on top of a large, diverse cohort of people with deep demographic data.

Challenge and Opportunity

According to the National Research Council, almost half of premature deaths (< 86 years of age) are caused by behavioral factors. Poor diet, high blood pressure, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and tobacco use are the primary causes of early death for most of these people. Yet, despite studying these factors for decades, we know surprisingly little about what can be done to turn these unhealthy behaviors into healthier ones. This has not been due to a lack of effort. Thousands of randomized controlled trials intended to uncover messaging and incentives that can be used to steer people towards healthier behaviors have failed to yield impactful steps that can be broadly deployed to drive behavioral change across our diverse population. For sure, changing human behavior through such mechanisms is controversial, and difficult. Nonetheless studying how to bend behavior should be a national imperative if we are to extend healthspan and address the declining lifespan of Americans at scale.

Limitations of RCTs

Traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which usually test a single intervention, are often underpowered, and expensive, and short-lived, limiting their utility even though RCTs remain the gold standard for determining the validity of behavioral economics studies. In addition, because the diversity of our population in terms of biology, and culture are severely limiting factors for study design, RCTs are often conducted on narrow, well-defined populations. What works for a 24-year-old female African American attorney in Los Angeles may not be effective for a 68-year-old male white fisherman living in Mississippi. Overcoming such noise in the system means either limiting the population you are examining through demographics, or deploying raw power of numbers of study participants that can allow post study stratification and hypothesis development. It also means that health data alone is not enough. Such studies require deep personal demographic data to be combined with health data, and wearables. In essence, we need a very clear picture of the lives of participants to properly identify interventions that work and apply them appropriately post-study on broader populations. Similarly, testing a single intervention means that you cannot be sure that it is the most cost-effective or impactful intervention for a desired outcome. This further limits the ability to deploy RCTs at scale. Finally, the data sometimes implies spurious associations. Therefore, preregistration of endpoints, interventions, and analysis of such studies will make for solid evidence development even if the most tantalizing outcomes come from sifting through the data later to develop new hypotheses that can be further tested.

Value of Megastudies

Professors Angela Duckworth and Katherine Milkman, at the University of Pennsylvania, have proposed an expansion of the use of megastudies to gain deeper behavioral insights from larger populations. In essence, megastudies are “massive field experiments in which many different treatments are tested synchronously in a large sample using a common objective outcome.” This sort of paradigm allows independent researchers to develop interventions to test in parallel against other teams. Participants are randomly assigned across a large cohort to determine the most impactful and cost-effective interventions. In essence, the teams are competing against each other to develop the most effective and practical interventions on the same population for the same measurable outcome.

Using this paradigm, we can rapidly assess interventions, accelerate scientific progress by saving time and money, all while making more appropriate comparisons to bend behavior towards healthier lifestyles. Due to the large sample sizes involved and deep knowledge of the demographics of participants, megastudies allow for the noise that is normal in a broad population that normally necessitates narrowing the demographics of participants. Further, post study analysis allows for rich hypothesis generation on what interventions are likely to work in more narrow populations. This enables tailored messaging and incentives to the individual. A centralized entity managing the population data reduces costs and makes it easier to try a more diverse set of risk-tolerant interventions. A centralized entity also opens the door to smaller labs to participate in studies. Finally, the participants in these megastudies are normally part of ongoing health interactions through a large cohort study or directly through care providers. Thus, they benefit directly from participation and tailored messages and incentives. Additionally, dataset scale allows for longer term study design because of the reduction in overall costs. This enables study designers to determine if their interventions work well over a longer period of time or if the impact of interventions wane and need to be adjusted.

Funding and Operational Challenges

But this kind of “apples to apples” comparison has serious drawbacks that have prevented megastudies from being used routinely in science despite their inherent advantage. First, megastudies require access to a large standing cohort of study participants that will remain in the cohort long term. Ideally, the organizer of such studies should be vested in having positive outcomes. Here, larger insurance companies are poor targets for organizing. Similarly, they have to be efficient, thus, government run cohorts, which tend to be highly bureaucratic, expensive, and inefficient are not ideal. Not everything need go through a committee. (Looking at you, All of Us at NIH and Million Veterans Program at the VA).

Companies like third party administrators of healthcare plans might be an ideal organizing body, but so can companies that aim to lower healthcare costs as a means of generating revenue through cost savings. These companies tend to have access to much deeper data than traditional cohorts run by government and academic institutions and could leverage that data for better stratifying participants and results. However, if the goal of government and philanthropic research efforts is to improve outcomes, then they should open the aperture on available funds to stand up a persistent cohort that can be used by many researchers rather than continuing the one-off paradigm, which in the end is far more expensive and inefficient. Finally, we do not imply that all intervention types should be run through megastudies. They are an essential, albeit underutilized tool in the arsenal, but not a silver bullet for testing behavioral interventions.

Fear of Unauthorized Data Access or Misuse

There is substantial risk when bringing together such deep personal data on a large population of people. While companies compile deep data all the time, it is unusual to do so for research purposes and will, for sure, raise some eyebrows, as has been the case for large studies like the aforementioned All of Us and the Million Veteran’s Program.

Patients fear misuse of their data, inaccurate recommendations, and biased algorithms—especially among historically marginalized populations. Patients must trust that their data is being used for good, not for marketing purposes and determining their insurance rates.

Icons © 2024 by Jae Deasigner is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Need for Data Interoperability

Many healthcare and community systems operate in data silos and data integration is a perennial challenge in healthcare. Patient-generated data from wearables, apps, or remote sensors often do not integrate with electronic health record data or demographic data gathered from elsewhere, limiting the precision and personalization of behavior-change interventions. This lack of interoperability undermines both provider engagement and user benefit. Data fragmentation and poor usability requires designing cloud-based data connectors and integration, creating shared feedback dashboards linking self-generated data to provider workflows, and creating and promoting policies that move towards interoperability. In short, given the constantly evolving data integration challenge and lack of real standards for data formats and integration requirements, a dedicated and persistent effort will have to be made to ensure that data can be seamlessly integrated if we are to draw value from combining data from many sources for each patient.

Additional Barriers

One of the largest barriers to using behavioral economics is that some rural, tribal, low-income, and older adults face access barriers. These could include device affordability, broadband coverage, and other usability and digital literacy limitations. Megastudies are not generally designed to bridge this gap leaving a significant limitation of applicability for these populations. Complicating matters, these populations also happen to have significant and specific health challenges unique to their cohorts. As the use of behavioral economic levers are developed, these communities are in danger of being left behind, further exacerbating health disparities. Nonetheless, insight into how to reach these populations can be gained for individuals in these populations that do have access to technology platforms. Communications will have to be tailored accordingly.

External motivators have been consistently shown to be the essential drivers of behavioral change. But motivation to sustain a behavior change and continue using technology often wanes over time. Embedding intrinsic-value rewards and workplace incentives may not be enough. Therefore, external motivations likely have to be adjusted over time in a dynamic system to ensure that adjustments to the behavior of the individual can be rooted in evidence. Indeed, study of the dynamic nature of driving behavioral change will be necessary due to the likelihood of waning influence of static messaging. By designing reward systems that tie personal values and workplace wellness programs sustained engagement through social incentives and tailored nudges may keep users engaged.

Plan of Action

By enabling a private sector entity to create a research platform using patient data combined with deep demographic data, and an ethical framework for access and use, we can create a platform for megastudies. This would allow the rapid testing of behavioral interventions that steer people towards healthier lifestyles, saving money, accelerating progress, and better understanding what works, in whom, and when for changing human behavior.

This could have been done through either the All of Us program or Million Veterans program or a different large cohort study, but neither program has the deep demographic and lifestyle data required to stratify their population. Both are mired in bureaucratic lethargy that is common in large scale government programs. Health insurance companies and third-party administrators of health insurance can gather such data, be nimbler, create a platform for communicating directly with patients, coordinate with their clinical providers. But one could argue that neither entity has a real incentive to bend behavior and encourage healthy lifestyles. Simply put, that is not their business.

Recommendation 1. Issue a directive to agencies to invest in the development of a megastudy platform for health behavioral economics studies.

The White House of HHS Secretary should direct the NIH or ARPA-H to develop a plan for funding the creation of a behavioral economics megastudy platform. The directive should include details on the ethical and technical framework requirements as well as directions for development of oversight of the platform once it is created. The platform should be required to establish a sustainability plan as part of the application for a contract to create the megastudy platform.

Recommendation 2. Government should fund the establishment of a megastudy platform.

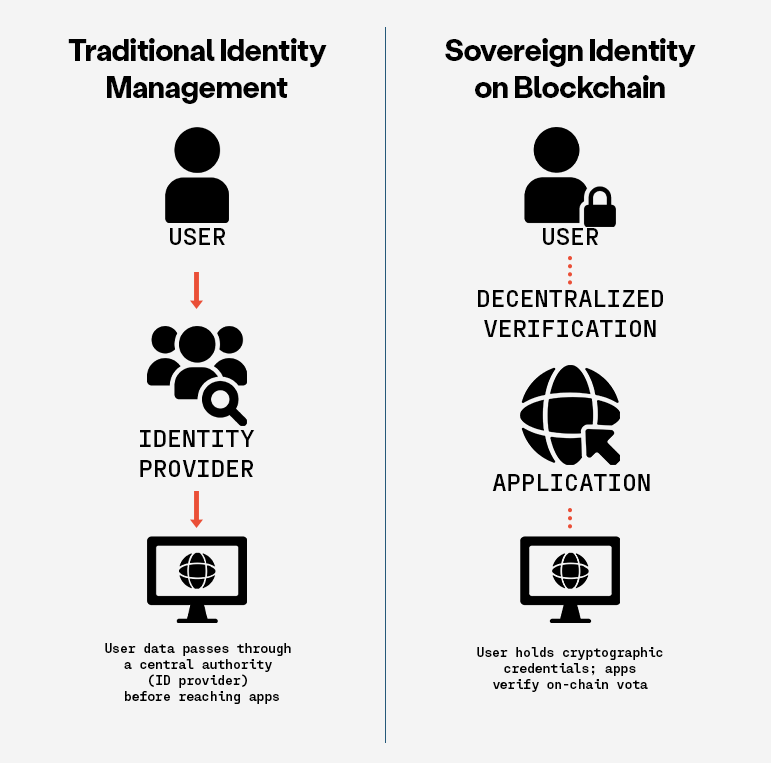

ARPA-H and/or DARPA should develop a program to establish a broad research platform in the private sector that will allow for megastudies to be conducted. Then research teams can, in parallel, test dozens of behavioral interventions on populations and access patient data. This platform should have required ethical rules and be grounded in data sovereignty that allows patients to opt out of participation and having their data shared.

Data sovereignty is one solution to the trust challenge. Simply put, data sovereignty means that patients have access to the data on themselves (without having to pay a fee that physicians’ offices now routinely charge for access) and control over who sees and keeps that data. So, if at any time, a participant changes their mind, they can get their data and force anyone in possession of that data to delete it (with notable exceptions, like their healthcare providers). Patients would have ultimate control of their data in a ‘trust-less’ way that they never need to surrender, going well past the rather weak privacy provisions of HIPAA, so there is no question that they are in charge.

We suggest that using blockchain and token systems for data transfer would certainly be appropriate. Data held in a federated network to limit the danger of a breach would also be appropriate.

Recommendation 3. The NIH should fund behavioral economics megastudies using the platform.

Once the megastudy platform(s) are established, the NIH should make dedicated funds available for researchers to test for behavioral interventions using the platform to decrease costs, increase study longevity, and improve speed and efficiency for behavioral economics studies on behavioral health interventions.

Conclusion

Randomized controlled trials have been the gold standard for behavioral research but are not well suited for health behavioral interventions on a broad and diverse population because of the required number of participants, typical narrow population, recruiting challenges, and cost. Yet, there is an urgent need to encourage and incentivize d health related behaviors to make Americans healthier. Simply put, we cannot start to grow healthspan and lifespan unless we change behaviors towards healthier choices and habits. When the U.S. government funds the establishment of a platform for testing hundreds of behavioral interventions on a large diverse population, we will start to better understand the interventions that will have an efficient and lasting impact on health behavior. Doing so requires private sector cooperation and strict ethical rules to ensure public trust.

This memo produced as part of Strengthening Pathways to Disease Prevention and Improved Health Outcomes.

The utility issues of accelerated, unadulterated AI uptake are not limited to legality. From use to testing to deployment, the scaffolding for responsible integration of AI into high-risk use cases is just not there.

The Federation of American Scientists supports Congress’ ongoing bipartisan efforts to strengthen U.S. leadership with respect to outer space activities.

By preparing credible, bipartisan options now, before the bill becomes law, we can give the Administration a plan that is ready to implement rather than another study that gathers dust.

Even as companies and countries race to adopt AI, the U.S. lacks the capacity to fully characterize the behavior and risks of AI systems and ensure leadership across the AI stack. This gap has direct consequences for Commerce’s core missions.