Incomplete Upgrades at RAF Lakenheath Raise Questions About Suspected US Nuclear Deployment

Satellite imagery of RAF Lakenheath reveals new construction of a security perimeter around ten protective aircraft shelters in the designated nuclear area, the latest measure in a series of upgrades as the base prepares for the ability to store U.S. nuclear weapons. However, U.S. budget documents indicate that forthcoming upgrades to security and command and control are required before the base can accommodate a nuclear mission. These projects introduce more questions than answers about RAF Lakenheath’s nuclear status and what its role will be in the NATO nuclear strike mission.

In addition to these upgrades, the United Kingdom recently announced plans to expand its nuclear posture by adding a nuclear role for the Royal Air Force through the purchase of 12 F-35As from the United States to join NATO’s nuclear sharing mission; a further reduction in the “independence” of the UK deterrent.

Combined, these changes mark a departure from decades of nuclear policy and underscore a broader shift in NATO nuclear posture in response to tensions with Russia.

Are There New U.S. Nukes in the UK?

In July 2025, a set of two USAF C-17 flights directly from Kirtland AFB to RAF Lakenheath in Suffolk, England, triggered widespread rumors that nuclear weapons had been shipped to the base. While the indicators are strong, other Air Force budget documents raise questions about whether the necessary nuclear upgrades at the base have been completed to allow deployment yet.

Aside from Türkiye, each NATO country that hosts U.S. nuclear weapons has purchased the F-35A Lightning II to replace its legacy aircraft in the nuclear delivery role. In 2022, RAF Lakenheath became the first European base to receive the F-35A, and its 48th Fighter Wing remains the only USAF wing to operate both the F-15E and the F-35A nuclear-capable fighter aircraft. Years of accumulating evidence now point to the preparation of U.S.-operated RAF Lakenheath to receive U.S. B61 nuclear gravity bombs, marking the first time in nearly 20 years that the USAF nuclear mission has returned to the United Kingdom.

Then, on July 17, 2025, analysts tracked the flight of a C-17 nuclear transport plane associated with the Prime Nuclear Airlift Force from Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico to RAF Lakenheath. The direct flight from the USAF nuclear weapons depot at Albuquerque did not overfly other countries on its way to Lakenheath, a strong indicator that the aircraft could have been carrying nuclear materials. A second similar flight took place a few days later on July 23. During these dates, several signs, such as increased security measures at RAF Lakenheath, suggest that these flights could have been the first transfer of nuclear weapons to the base. Despite these strong indicators, several factors regarding additional command and security features raise doubts that a weapons shipment has already occurred.

First and foremost, if nuclear weapons were to be deployed, we would expect to see a completed security perimeter around the designated nuclear area at RAF Lakenheath similar to what other nuclear bases across Europe have received (see figure 1). The FY25 USAF Military Construction Budget included a project for establishing a “Surety mission Protective Aircraft Shelter Barrier System,” which will consist of fencing, security gates, access and perimeter control roads, entry control points, and cybersecurity. The Air Force document states that the project is “required to provide a permanent perimeter security system around 22 Protective Aircraft Shelters that will be used to support the Surety mission.” Without these additional features, according to the US Air Force, “Royal Air Force Lakenheath lacks the physical security measures needed to protect Surety assets within the Protective Aircraft Shelters from unauthorized access, theft, damage, sabotage, or unauthorized use.”

Notably, satellite imagery from Planet Laboratories does reveal the initial construction of a secure fencing perimeter in the designated nuclear area that began as early as February 2025. However, the construction is taking place around ten, not 22, of the protective aircraft shelters, as the FY26 budget had indicated. Meanwhile, there is no mention of this fencing project in the FY23 or FY24 budgets, and the FY25 budget states that construction for this project is set to start in May 2026, with completion anticipated for October 2029. There is also no mention of a fencing or “security barrier” project in the FY26 budget estimate. Additionally, the FY25 budget indicates that $185 million was requested and authorized for this project, but only $5 million was appropriated, meaning the project wasn’t cancelled, but Congress only released that number out of the total authorized funds. It is possible that the funding for this project could have been redesignated to come from a different budget, but it is nevertheless an odd discrepancy.

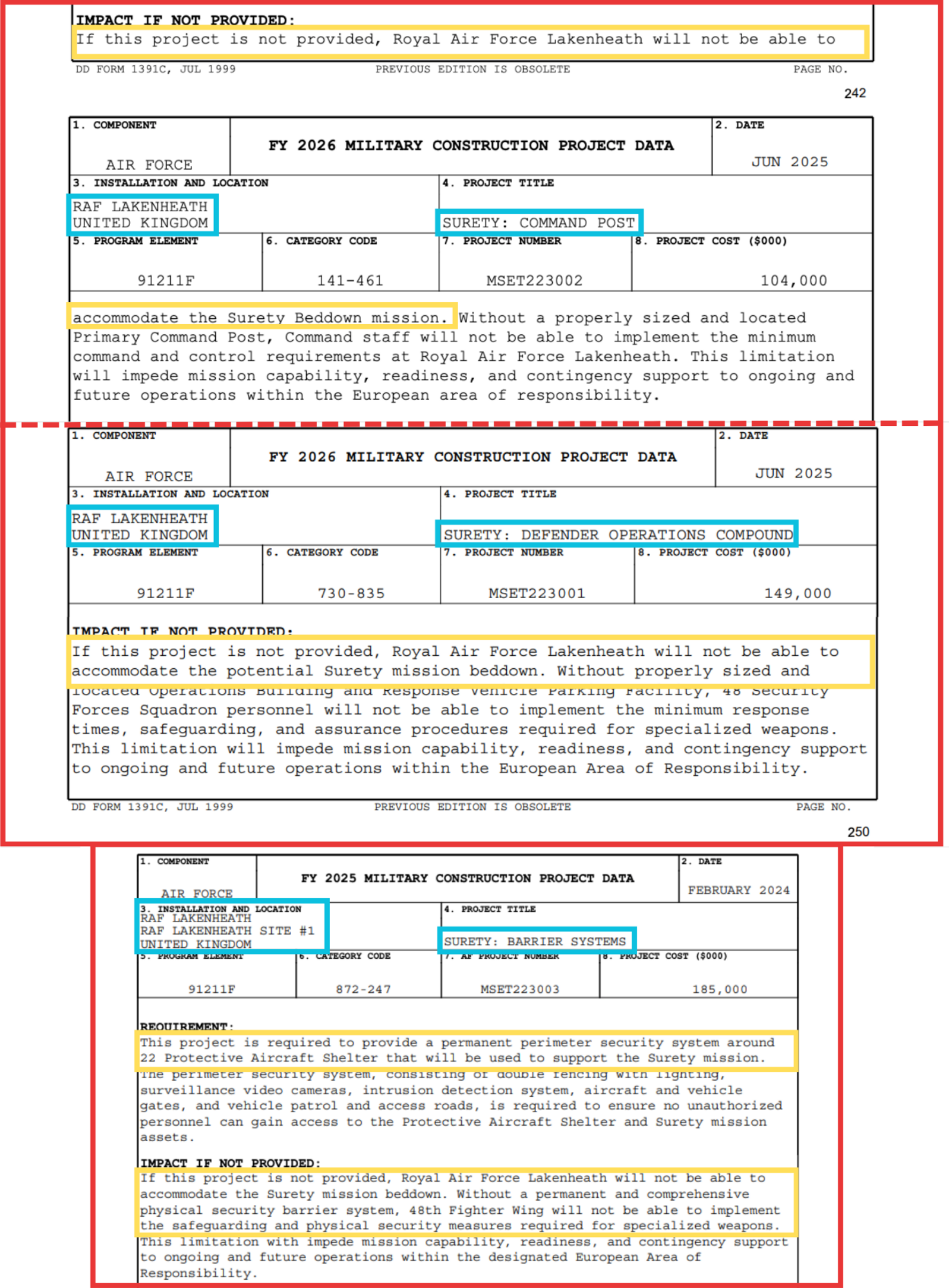

Two other major infrastructure projects outlined in the U.S. Air Force FY26 military construction budget have yet to be completed. The first project is for a “Command Post” at RAF Lakenheath, which will involve replacing and improving security at facilities to meet intelligence security standards, hardening facilities to protect against “collateral effects,” and expanding capacity to accommodate an increase in staff to support the “surety mission” as well as the “Air Force Nuclear Command, Control, and Communications, and Global Aircrew Strategic Network Terminal equipment.” The budget states that “if this project is not provided, Royal Air Force Lakenheath will not be able to accommodate the Surety Beddown mission” (see figure 2). It continues, saying that without this facility, staff “will not be able to implement the minimum command and control requirements at Royal Air Force Lakenheath. This limitation will impede mission capability, readiness, and contingency support to ongoing and future operations within the European area of responsibility.” Construction for the command post is not scheduled to begin until August 2027 and is not expected to be completed until July 2031.

The second project outlined in the FY26 Air Force budget is a “Defender Operations Compound” at RAF Lakenheath, which includes a range of security-related infrastructure, personnel, and operational support, as the existing capacity is deemed “undersized for the current mission.” The purpose of this project is “to provide enhanced security capabilities supporting the potential stationing of specialized weapons at Royal Air Force Lakenheath. Specialized weapons surety includes materiel, personnel, and procedures contributing to the safeguarding and reliability of specialized weapons, and to the assurance that there will be no specialized weapon accidents, incidents, unauthorized weapon detonation, or degradation in performance at the target.” This section of the budget repeated a statement about the importance of this project for Lakenheath to be able to “accommodate the potential Surety mission beddown.” Construction is not scheduled to begin until March 2028 and is not expected to be completed until June 2031. Both of these programs—the Command Post and the Defender Operations Compound—were listed as “future projects” in the FY24 and FY25 budgets.

The ongoing construction of a security perimeter and the pending construction of command and control infrastructure outlined in the budget raise the question of whether the USAF would have deployed gravity bombs to Lakenheath already. Additionally, these uncertainties prompt further questions about whether Lakenheath’s role has shifted from a contingency site to a more permanent or semi-permanent deployment location.

If There Aren’t New U.S. Nukes Now, There Will Be At Some Point

Meanwhile, on June 24, 2025, the United Kingdom announced the purchase of 12 new nuclear-capable F-35As from the United States and its intention to join NATO’s nuclear sharing mission. These aircraft will be based at RAF Marham, an air base near Lakenheath with a similar Cold War nuclear legacy, and the base will also eventually be equipped to host U.S. nuclear gravity bombs in the 2030s.

The United Kingdom retired and destroyed all its nonstrategic gravity bombs in 1998 and has since relied solely on four nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines for its nuclear deterrent. The submarines carry ballistic missiles leased from the United States, and although the warhead has been developed and manufactured by the United Kingdom, the design is similar to the U.S. Navy’s W76 warhead, and the United States also supplies the reentry body. This decision to join the NATO nuclear-sharing mission with dual-capable aircraft equipped with U.S. nuclear bombs increases the United Kingdom’s reliance on the United States and marks a significant departure from decades of UK nuclear strategy and posture, apparently in reaction to the growing concern about Russia.

This plan was first hinted at in the UK’s latest Strategic Defence Review—published on June 2, 2025—which recommended that the Ministry of Defence “commence discussions with the United States and NATO on the potential benefits and feasibility of enhanced UK participation in NATO’s nuclear mission.” Less than a month later, the UK government formally announced its decision to buy the 12 F-35As from the United States. A parliamentary inquiry to the Minister of Armed Forces by the Defence Committee questioned whether the decision is coherent with the UK’s current nuclear doctrine and raised concerns about retaining British nuclear sovereignty, considering that the 12 F-35As will not be able to use their nuclear weapons unless authorized to do so by the president of the United States. The inquiry Chair also commented on how this change is the “most significant defence expansion since the Cold War” and noted that the UK’s Defence Nuclear Enterprise remains outside of meaningful parliamentary inquiry, despite accounting for around 20% of the total defence budget.

Similar to the upgrades taking place at Lakenheath, the future deployment of U.S. gravity bombs to RAF Marham will require significant upgrades to command and control and infrastructure at the base. From specialized tarmacs for the new F-35As, to updating the protective aircraft shelters and specialized WS3 storage vaults for nuclear gravity bombs (which were deactivated in the late-1990s), to improving security perimeters and installations at the base, RAF Marham has a long way to go before the nuclear mission becomes operational in the early 2030s.

The Bigger Picture in Europe

The nuclear upgrades at RAF Lakenheath and RAF Marham contradict statements made by NATO officials just a few years ago. In 2021, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg stated, “We have no plans of stationing any nuclear weapons in any other countries than we already have these nuclear weapons as part of our deterrence.” Two years later, in 2023, then-head of NATO nuclear policy Jessica Cox echoed Stoltenberg’s assurance, saying, “There is no need to change where they are placed.”

The news of a potential deployment of nuclear weapons to RAF Lakenheath and the UK’s purchase of F-35As for the NATO nuclear mission are the latest in a series of developments showing increased nuclear posturing in Europe over the past decade. The deepening crisis with Russia has led to an increase in rhetoric, posture, and operational exercises involving nuclear weapons from the United States and NATO countries. Expansive upgrades to bases storing U.S. nuclear weapons across Europe, enhanced visibility of NATO’s annual tactical nuclear exercise, increased strategic bomber operations, and strategic missile submarines making port visits or surfacing for photo opportunities are just some of the more tangible signals that are raising the profile of nuclear weapons. France, too, has bolstered its nuclear rhetoric, increased spending on its nuclear program, and announced plans to establish another nuclear air base at Luxeuil-Saint-Sauveur in eastern France.

All together, the NATO nuclear upgrades combined with Russia’s own upgrades and nuclear sharing with Belarus, illustrate a deepening reliance on nuclear weapons for security in Europe. The United Kingdom’s entry into the NATO nuclear mission and the likely deployment of U.S. B61 bombs to not one but two bases in the United Kingdom mark the first time since the end of the Cold War that the number of nuclear bases in Europe and the amount of nuclear weapons on European territory could be growing rather than decreasing.

This article was researched and written with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Jubitz Family Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.

While advanced Chinese language proficiency and cultural familiarity remain irreplaceable skills, they are neither necessary nor sufficient for successful open-source analysis on China’s nuclear forces.