Clean Water: Protecting New York State Private Wells from PFAS

This memo responds to a policy need at the state level that originates due to a lack of relevant federal data. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has a learning agenda question that asks,“To what extent does EPA have ready access to data to measure drinking water compliance reliably and accurately?” This memo fills that need because EPA doesn’t measure private wells.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are widely distributed in the environment, in many cases including the contamination of private water wells. Given their links to numerous serious health consequences, initiatives to mitigate PFAS exposure among New York State (NYS) residents reliant on private wells were included among the priorities outlined in the annual State of the State address and have been proposed in state legislation. We therefore performed a scenario analysis exploring the impacts and costs of a statewide program testing private wells for PFAS and reimbursing the installation of point of entry treatment (POET) filtration systems where exceedances occur.

Challenge and Opportunity

Why care about PFAS?

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a class of chemicals containing millions of individual compounds, are of grave concern due to their association with numerous serious health consequences. A 2022 consensus study report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine categorized various PFAS-related health outcomes based on critical appraisal of existing evidence from prior studies; this committee of experts concluded that there is high confidence of an association between PFAS exposure and (1) decreased antibody response (a key aspect of immune function, including response to vaccines) (2) dyslipidemia (abnormal fat levels in one’s blood), (3) decreased fetal and infant growth, and (4) kidney cancer, and moderate confidence of an association between PFAS exposure and (1) breast cancer, (2) liver enzyme alterations, (3) pregnancy-induced high blood pressure, (4) thyroid disease, and (5) ulcerative colitis (an autoimmune inflammatory bowel disease).

Extensive industrial use has rendered these contaminants virtually ubiquitous in both the environment and humans, with greater than 95% of the U.S. general population having detectable PFAS in their blood. PFAS take years to be eliminated from the human body once exposure has occurred, earning their nickname as “forever chemicals.”

Why focus on private drinking water?

Drinking water is a common source of exposure.

Drinking water is a primary pathway of human exposure. Combining both public and private systems, it is estimated that approximately 45% of U.S. drinking water sources contain at least one PFAS. Rates specific to private water supplies have varied depending on location and thresholds used. Sampling in Wisconsin revealed that 71% of private wells contained at least one PFAS and 4% contained levels of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) or perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), two common PFAS compounds, exceeding Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) of 4 ng/L. Sampling in New Hampshire, meanwhile, found that 39% of private wells exceeded the state’s Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQS), which were established in 2019 and range from 11-18 ng/L depending on the specific PFAS compound. Notably, while the EPA MCLs represent legally enforceable levels accounting for the feasibility of remediation, the agency has also released health-based, non-enforceable Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs) of zero for PFOA and PFOS.

PFAS in private water are unregulated and expensive to remediate.

In New York State (NYS), nearly one million households rely on private wells for drinking water; despite this, there are currently no standardized well testing procedures and effective well water treatment is unaffordable to many New Yorkers. As of April 2024, the EPA has established federal MCLs for several specific PFAS compounds and mixtures of compounds and its National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) require public water systems to begin monitoring and publicly reporting levels of these PFAS by 2027; if monitoring reveals exceedances of the MCLs, public water systems must also implement solutions to reduce PFAS by 2029. In contrast, there are no standardized testing procedures or enforceable limits for PFAS in private water. Additionally, testing and remediating private wells are both associated with high costs which are unaffordable to many well owners; prices range in hundreds of dollars for PFAS testing and can cost several thousands of dollars for the installation and maintenance of effective filtration systems.

How are states responding to the problem of PFAS in private drinking water?

Several states, including Colorado, New Hampshire, and North Carolina, have already initiated programs offering well testing and financial assistance for filters to protect against PFAS.

- After piloting its PFAS Testing and Assistance (TAP) program in one county in 2024, Colorado will expand it to three additional counties in 2025. The program covers the expenses of testing and a $79 nano pitcher (point-of-use) filter. Residents are eligible if PFOA and/or PFOS in their wells exceeds EPA MCLs of 4 ng/L; filters are free if their household income is ≤80% of the area median income and offered at a 30% discount if this income criteria is not met.

- The New Hampshire (NH) PFAS Removal Rebate Program for Private Wells offers greater flexibility and higher cost coverage than Colorado PFAS TAP, with reimbursements of up to $5000 offered for either point-of-entry or point-of-use treatment system installation and up to $10,000 offered for connection to a public water system. Though other residents may also participate in the program and receive delayed reimbursement, households earning ≤80% of the area median family income are offered the additional assistance of payment directly to a treatment installer or contractor (prior to installation) so as to relieve the applicant of fronting the cost. Eligibility is based on testing showing exceedances of the EPA MCLs of 4 ng/L for PFOA or PFOS or 10 ng/L for PFHxS, PFNA, or HFPO-DA (trademarked as “GenX”).

- The North Carolina PFAS Treatment System Assistance Program offers flexibility similar to New Hampshire in terms of the types of water treatment reimbursed, including multiple point-of-entry and point-of-use filter options as well as connection to public water systems. It is additionally notable for its tiered funding system, with reimbursement amounts ranging from $375 to $10,000 based on both the household’s income and the type of water treatment chosen. The tiered system categorizes program participants based on whether their household income is (1) <200%, (2) 200-400%, or (3) >400% the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). Also similar to New Hampshire, payments may be made directly to contractors prior to installation for the lowest income bracket, who qualify for full installation costs; others are reimbursed after the fact. This program uses the aforementioned EPA MCLs for PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, or HFPO-DA (“GenX”) and also recognizes the additional EPA MCL of a hazard index of 1.0 for mixtures containing two or more of PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, or PFBS.

An opportunity exists to protect New Yorkers.

Launching a program in New York similar to those initiated in Colorado, New Hampshire, and North Carolina was among the priority initiatives described by New York Governor Kathy Hochul in the annual State of the State she delivered in January 2025. In particular, Hochul’s plans to improve water infrastructure included “a pilot program providing financial assistance for private well owners to replace or treat contaminated wells.” This was announced along with a $500 million additional investment beyond New York’s existing $5.5 billion dedicated to water infrastructure, which will also be used to “reduce water bills, combat flooding, restore waterways, and replace lead service lines to protect vulnerable populations, particularly children in underserved communities.” In early 2025, the New York Legislature introduced Senate Bill S3972, which intended to establish an installation grant program and a maintenance rebate program for PFAS removal treatment. Bipartisan interest in protecting the public from PFAS-contaminated drinking water is further evidenced by a hearing focused on the topic held by the NYS Assembly in November 2024.

Though these efforts would likely initially be confined to a smaller pilot program with limited geographic scope, such a pilot program would aim to inform a broader, statewide intervention. Challenges to planning an intervention of this scope include uncertainty surrounding both the total funding which would be allotted to such a program and its total costs. These costs will be dependent on factors such as the eligibility criteria employed by the state, the proportion of well owners who opt into sampling, and the proportion of tested wells found to have PFAS exceedances (which will further vary based on whether the state adopts EPA MCLs or NYS Department of Health MCLs, which are 10 ng/L for PFOA and PFOS). We allay the uncertainty associated with these numerous possibilities by estimating the numbers of wells serviced and associated costs under various combinations of 10 potential eligibility criteria, 5 possible rates (5, 25, 50, 75, and 100%) of PFAS testing among eligible wells, and 5 possible rates (5, 25, 50, 75, and 100%) of PFAS>MCL and subsequent POET installation among wells tested.

Scenario Analysis

Key findings

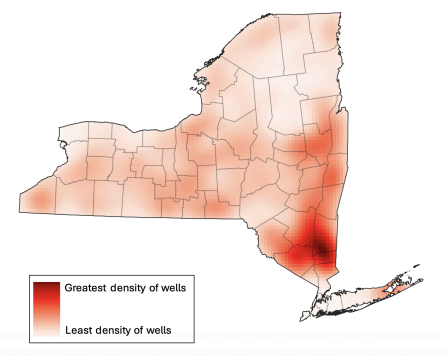

- Over 900,000 residences across NYS are supplied by private drinking wells (Figure 1).

- The three most costly scenarios were offering testing and installation rebates for (Table 1):

- Every private well owner (901,441 wells; $1,034,403,547)

- Every well located within a census tract designated as disadvantaged (based on NYS Disadvantaged Community (DAC) criteria) AND/OR belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000 (725,923 wells; $832,996,643)

- Every well belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000 (705,959 wells; $810,087,953)

- The three least costly scenarios were offering testing and installation rebates for (Table 1):

- Every well located within a census tract in which at least 51% of households earn below 80% of the area median income (22,835 wells; $26,191,688)

- Every well belonging to a household earning <100% of the Federal Poverty Level (92,661 wells; $106,328,398)

- Every well located within a census tract designated as disadvantaged (based on NYS Disadvantaged Community (DAC) criteria) (93,840 wells; $107,681,400)

- Of six income-based eligibility criteria, household income <$150,000 included the greatest number of wells, whereas location within a census tract in which at least 51% of households earn below 80% the area median income (a definition of low-to-moderate income used for programs coordinated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development), included the fewest wells. This amounts to a cost difference of $783,896,265 between these two eligibility scenarios.

- Six income-based criteria varied dramatically in terms of their inclusion of wells across NYS which fall within either disadvantaged or small communities (Table 2):

- For disadvantaged communities, this ranged from 12% (household income <100% federal poverty level) to 79% (income <$150,000) of all wells within disadvantaged communities being eligible.

- For small communities, this ranged from 2% (census tracts in which at least 51% of households earn below 80% area median income) to 83% (income <$150,000) of all wells within small communities being eligible.

Plan of Action

New York State is already considering a PFAS remediation program (e.g., Senate Bill S3972). The 2025 draft of the bill directed the New York Department of Environmental Conservation to establish an installation grant program and a maintenance rebate program for PFAS removal treatment, and establishes general eligibility criteria and per-household funding amounts. To our knowledge, S3972 did not pass in 2025, but its program provides a strong foundation for potential future action. Our suggestions below resolve some gaps in S3972, including additional detail that could be followed by the implementing agency and overall cost estimates that could be used by the Legislature when considering overall financial impacts.

Recommendation 1. Remediate all disadvantaged wells statewide

We recommend including every well located within a census tract designated as disadvantaged (based on NYS Disadvantaged Community (DAC) criteria) and/or belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000 as the eligibility criteria which protects the widest range of vulnerable New Yorkers. Using this criteria, we estimate a total program cost of approximately $833 million, or $167 million per year if the program were to be implemented over a 5-year period. Even accounting for the other projects which the state will be undertaking at the same time, this annual cost falls well within the additional $500 million which the 2025 State of the State reports will be added in 2025 to an existing $5.5 million state investment in water infrastructure.

Recommendation 2. Target disadvantaged census tracts and household incomes

Wells in DAC census tracts accounts for a variety of disadvantages. Including NYS DAC criteria helps to account for the heterogeneity of challenges experienced by New Yorkers by weighing statistically meaningful thresholds for 45 different indicators across several domains. These include factors relevant to the risk of PFAS exposure, such as land use for industrial purposes and proximity to active landfills.

Wells in low-income households account for cross-sectoral disadvantage. The DAC criteria alone is imperfect:

- Major criticisms include its underrepresentation of rural communities (only 13% of rural census tracts, compared to 26% of suburban and 48% of urban tracts, have been DAC-designated) and failure to account for some key stressors relevant to rural communities (e.g., distance to food stores and in-migration/gentrification).

- Another important note is that wells within DAC communities account for only 10% of all wells within NYS (Table 2). While wells within DAC-designated communities are important to consider, including only DAC wells in an intervention would therefore be very limiting.

- Whereas DAC designation is a binary consideration for an entire census tract, place-based criteria such as this are limited in that any real community comprises a spectrum of socioeconomic status and (dis)advantage.

The inclusion of income-based criteria is useful in that financial strain is a universal indicator of resource constraint which can help to identify the most-in-need across every community. Further, including income-based criteria can widen the program’s eligibility criteria to reach a much greater proportion of well owners (Table 2). Finally, in contrast to the DAC criteria’s binary nature, income thresholds can be adjusted to include greater or fewer wells depending on final budget availability.

- Of the income thresholds evaluated, income <$150,000 is recommended due to its inclusion not only of the greatest number of well owners overall, but also the greatest percentages of wells within disadvantaged and small communities (Table 2). These two considerations are both used by the EPA in awarding grants to states for water infrastructure improvement projects.

- As an alternative to selecting one single income threshold, the state may also consider maximizing cost effectiveness by adopting a tiered rebate system similar to that used by the North Carolina PFAS Treatment System Assistance Program.

Recommendation 3. Alternatives to POETs might be more cost-effective and accessible

A final recommendation is for the state to maximize the breadth of its well remediation program by also offering reimbursements for point-of-use treatment (POUT) systems and for connecting to public water systems, not just for POET installations. While POETs are effective in PFAS removal, they require invasive changes to household plumbing and prohibitively expensive ongoing maintenance, two factors which may give well owners pause even if they are eligible for an initial installation rebate. Colorado’s PFAS TAP program models a less invasive and extremely cost-effective POUT alternative to POETs. We estimate that if NYS were to provide the same POUT filters as Colorado, the total cost of the program (using the recommended eligibility criteria of location within a DAC-designated census tract and/or belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000) would be $163 million, or $33 million per year across 5 years. This amounts to a total decrease in cost of nearly $670 million if POUTs were to be provided in place of POETs. Connection to public water systems, on the other hand, though a significant initial investment, provides an opportunity to streamline drinking water monitoring and remediation moving forward and eliminates the need for ongoing and costly individual interventions and maintenance.

Conclusion

Well testing and rebate programs provide an opportunity to take preventative action against the serious health threats associated with PFAS exposure through private drinking water. Individuals reliant on PFAS-contaminated private wells for drinking water are likely to ingest the chemicals on a daily basis. There is therefore no time to waste in taking action to break this chain of exposure. New York State policymakers are already engaged in developing this policy solution; our recommendations can help both those making the policy and those tasked with implementing it to best serve New Yorkers. Our analysis shows that a program to mitigate PFAS in private drinking water is well within scope of current action and that fair implementation of such a program can help those who need it most and do so in a cost-effective manner.

While the Safe Drinking Water Act regulates the United States’ public drinking water supplies, there is no current federal government to regulate private wells. Most states also lack regulation of private wells. Introducing new legislation to change this would require significant time and political will. Political will to enact such a change is unlikely given resource limitations, concerns around well owners’ privacy, and the current time in which the EPA is prioritizing deregulation.

Decreasing blood serum levels is likely to decrease negative health impacts. Exposure via drinking water is particularly associated with elevated serum PFAS levels, while appropriate water filtration has demonstrated efficacy in reducing serum PFAS levels.

We estimated total costs assuming that 75% of eligible wells are tested for PFAS and that of these tested wells, 25% are both found to have PFAS exceedances and proceed to have filter systems installed. This PFAS exceedance/POET installation rate was selected because it falls between the rates of exceedances observed when private well sampling was conducted in Wisconsin and New Hampshire in recent years.

For states which do not have their own tools for identifying disadvantaged communities, the Social Vulnerability Index developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) may provide an alternative option to help identify those most in need.

This year’s Red Sky Summit was an opportunity to further consider what the role of fire tech can and should be – and how public policy can support its development, scaling, and application.

Promising examples of progress are emerging from the Boston metropolitan area that show the power of partnership between researchers, government officials, practitioners, and community-based organizations.

FAS supports the bipartisan Regional Leadership in Wildland Fire Research Act under review in the House, just as we supported the earlier Senate version. Rep. David Min (D-CA) and Rep. Gabe Evans (R-CO) are leading the bill.

The current wildfire management system is inadequate in the face of increasingly severe and damaging wildfires. Change is urgently needed