The Data We Take for Granted: Telling the Story of How Federal Data Benefits American Lives and Livelihoods

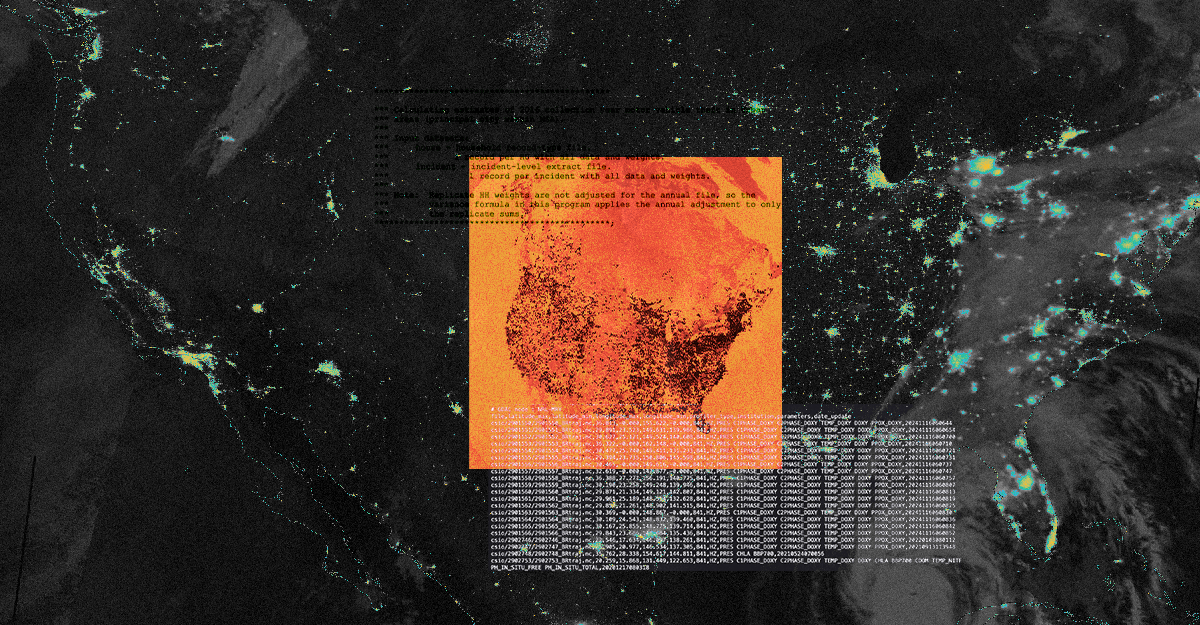

Across the nation, researchers, data scientists, policy analysts and other data nerds are anxiously monitoring the demise of their favorite federal datasets. Meanwhile, more casual users of federal data continue to analyze the deck chairs on the federal Titanic, unaware of the coming iceberg as federal cuts to staffing, contracting, advisory committees, and funding rip a giant hole in our nation’s heretofore unsinkable data apparatus. Many data users took note when the datasets they depend on went dark during the great January 31 purge of data to “defend women,” but then went on with their business after most of the data came back in the following weeks.

Frankly, most of the American public doesn’t care about this data drama.

However, like many things in life, we’ve been taking our data for granted and will miss it terribly when it’s gone.

As the former U.S. Chief Data Scientist, I know first-hand how valuable and vulnerable our nation’s federal data assets are. However, it took one of the deadliest natural disasters in U.S history to expand my perspective from that of just a data user, to a data advocate for life.

Twenty years ago this August, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans. The failure of the federal flood-protection infrastructure flooded 80% of the city resulting in devastating loss of life and property. As a data scientist working in New Orleans at the time, I’ll also note that Katrina rendered all of the federal data about the region instantly historical.

Our world had been turned upside down. Previous ways of making decisions were no longer relevant, and we were flying blind without any data to inform our long-term recovery. Public health officials needed to know where residents were returning to establish clinics for tetanus shots. Businesses needed to know the best locations to reopen. City Hall needed to know where families were returning to prioritize which parks they should rehabilitate first.

Normally, federal data, particularly from the Census Bureau, would answer these basic questions about population, but I quickly learned that the federal statistical system isn’t designed for rapid, localized changes like those New Orleans was experiencing.

We explored proxies for repopulation: Night lights data from NASA, traffic patterns from the local regional planning commission, and even water and electricity hookups from utilities. It turned out that our most effective proxy came from an unexpected source: a direct mail marketing company. In other words, we decided to use junk mail data to track repopulation.

Access to direct mail company Valassis’ monthly data updates was transformative, like switching on a light in a dark room. Spring Break volunteers, previously surveying neighborhoods to identify which houses were occupied or not, could now focus on repairing damaged homes. Nonprofits used evidence of returning residents to secure grants for childcare centers and playgrounds.

Even the police chief utilized this “junk mail” data. The city’s crime rates were artificially inflated because they used a denominator of annual Census population estimates that couldn’t keep pace with the rapid repopulation. Displaced residents had been afraid to return because of the sky-high crime rates, and the junk mail denominator offered a more timely, accurate picture.

I had two big realizations during this tumultuous period:

- Though we might be able to Macgyver some data to fill the immediate need, there are some datasets that only the federal government can produce, and

- I needed to expand my worldview from being just a data user, to also being an advocate for the high quality, timely, detailed data we need to run a modern society.

Today, we face similar periods of extreme change. Socio-technological shifts from AI are reshaping the workforce; climate-fueled disasters are coming at a rapid pace; and federal policies and programs are undergoing massive shifts. All of these changes will impact American communities in different ways. We’ll need data to understand what’s working, what’s not, and what we do next.

For those of us who rely on federal data in small or large ways, it’s time to champion the federal data we often take for granted. And, it’s also going to be critical that we, as active participants in this democracy, take a close look at the downstream consequences of weakening or removing any federal data collections.

There are upwards of 300,000 federal datasets. Here are just three that demonstrate their value:

- Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS): The NCVS is a sample survey produced through a collaboration between the Department of Justice and the Census Bureau that asks people if they’ve been victims of crime. It’s essential because it reveals the degree to which different types of crimes are underreported. Knowing the degree to which crimes like intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and hate crimes tend to be under-reported helps law enforcement agencies better interpret their own crime data and protect some of their most vulnerable constituents.

- NOAA’s ARGO fleet of drifting buoys: Innovators in the autonomous shipping industry depend on NOAA data such as that collected by the Argo Fleet of drifting buoys – an international collaboration that measures global ocean conditions. These detailed data train AI algorithms to find the safest and most fuel-efficient ocean routes.

- USGS’ North American Bat Monitoring Program: Bats save the American agricultural industry billions of dollars annually by consuming insects that damage crops. Protecting this essential service requires knowing where bats are. The USGS North American Bat Monitoring Program database is an essential resource for developers of projects that could disturb bat populations – projects such as highways, wind farms, and mining operations. This federal data not only protects bats but also helps streamline permitting and environmental impact assessments for developers.

If your work relies on federal data like these examples, it’s time to expand your role from a data user to a data advocate. Be explicit about the profound value this data brings to your business, your clients, and ultimately, to American lives and livelihoods.

That’s why I’m devoting my time as a Senior Fellow at FAS to building EssentialData.US to collect and share the stories of how specific federal datasets can benefit everyday Americans, the economy, and America’s global competitiveness.

EssentialData.US is different from a typical data use case repository. The focus is not on the user – researchers, data analysts, policymakers, and the like. The focus is on who ultimately benefits from the data, such as farmers, teachers, police chiefs, and entrepreneurs.

A good example is the Department of Transportation’s T-100 Domestic Segment Data on airplane passenger traffic. Analysts in rural economic development offices use these data to make the case for airlines to expand to their market, or for state or federal investment to increase an airport’s capacity. But it’s not the data analysts who benefit from the T-100 data. The people who benefit are the cancer patient living in a rural county who can now fly directly from his local airport to a metropolitan cancer center for lifesaving treatment, or the college student who can make it back to her home town for her grandmother’s 80th birthday without missing class.

Federal data may be largely invisible, but it powers so many products and services we depend on as Americans, starting with the weather forecast when we get up in the morning. The best way to ensure that these essential data keep flowing is to tell the story of their value to the American people and economy. Share the story of your favorite dataset with us at EssentialData.US. Here’s a direct link to the form.

It takes the average person over 9 hours and costs $160 to file taxes each year. IRS Direct File meant it didn’t have to.

To fight the climate crises, we must do more than connect power plants to the grid: we need new policy frameworks and expanded coalitions to facilitate the rapid transformation of the electricity system.