The Medicare Advance Healthcare Directive Enrollment (MAHDE) Initiative: Supporting Advance Care Planning for Older Medicare Beneficiaries

Taking time to plan and document a loved one’s preferences for medical treatment and end-of-life care helps respect and communicate their wishes to doctors while reducing unnecessary costs and anxiety. There is currently no federal policy requiring anyone, including Medicare beneficiaries, to complete an Advance Healthcare Directive (AHCD), which documents an individual’s preferences for medical treatment and end-of-life care. At least 40% of Medicare beneficiaries do not have a documented AHCD. In the absence of one, medical professionals may perform major and costly interventions unknowingly against a patient’s wishes.

To address this gap, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) should launch the Medicare Advance Healthcare Directive Enrollment (MAHDE) Initiative to support all adults over age 65 who are enrolled in Medicare or Medicare Advantage plans to complete and annually renew, at no extra cost, an electronic AHCD made available and stored on Medicare.gov or an alternative secure digital platform. MAHDE would streamline the process and make it easier for Medicare enrollees to complete and store directives and for healthcare providers to access them when needed. CMS could also work with the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) to expand Advance Care Planning (ACP) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures to include all Medicare Advantage plans caring for beneficiaries aged 65 and older.

AHCDs save families unnecessary heartache and confusion at times of great pain and vulnerability. They also aim to improve healthcare decision-making, patient autonomy, and function as a long-term cost-saving strategy by limiting undesired medical interventions among older adults.

Challenge and Opportunity

Advance healthcare directives document an individual’s preferences for medical treatment in medical emergencies or at the end of life.

AHCDs typically include two parts:

- Identifying a healthcare proxy or durable power of attorney, who will make decisions about an individual’s health when they are unable to.

- A living will, which describes the treatments an individual wants to receive in emergencies—such as CPR, breathing machines, and dialysis—as well as decisions on organ and tissue donation.

Other documents complement AHCDs and help communicate treatment wishes during emergencies or at the end of life. These include do-not-resuscitate orders, do-not-hospitalize orders, and Physician (or Medical) Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment forms, along with similar portable medical order forms for seriously ill or frail individuals (e.g., Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment, Physician Orders for Scope of Treatment, and Transportable Physician Orders for Patient Preferences). These forms are all designed to honor an individual’s healthcare preferences in a future medical emergency.

With the U.S. aging population projected to reach more than 20% of the total population by 2030, addressing end-of-life care challenges is increasingly urgent. As people age, their healthcare needs become more complex and expensive. Notably, 25% of all Medicare spending goes toward treating people in the last 12 months of their life. However, despite commonly receiving more aggressive treatments, many older adults prefer less intensive medical interventions and prioritize quality of life over prolonging life. This discrepancy between care received and a patient’s wishes is common, highlighting the need for clear and proactive communication and planning around medical preferences. Research shows patients with ACPs are less likely to receive unwanted and aggressive treatments in their last weeks of life, are more likely to enroll in hospice for comfort-focused care, and are less likely to die in hospitals or intensive care units.

Established ACP Policies and Support Mechanisms

Historically, some federal policies have underscored the importance of patient decision-making rights and the role of AHCDs in helping patients receive their desired care. These policies reflect the ongoing effort to empower patients to make informed decisions about their healthcare, particularly in end-of-life situations.

The Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA), a federal law introduced in 1990 as a part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, was created to ensure that patients are informed of their rights regarding medical care and their ability to make decisions about that care, especially in situations where they are no longer able to make decisions for themselves.

The Act requires hospitals, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), home health agencies, hospice programs, and health maintenance organizations to:

- Inform patients of their rights to make decisions under state law about their medical care, including accepting or refusing treatment.

- Periodically inquire whether a patient has completed a legally valid AHCD and make note in their medical record.

- Not discriminate against patients who do or do not have an advance directive.

- Ensure AHCDs and other documented care wishes are carried out, as permitted by state law.

- Provide education to staff, patients, and the community about AHCDs and the right to make their own medical decisions.

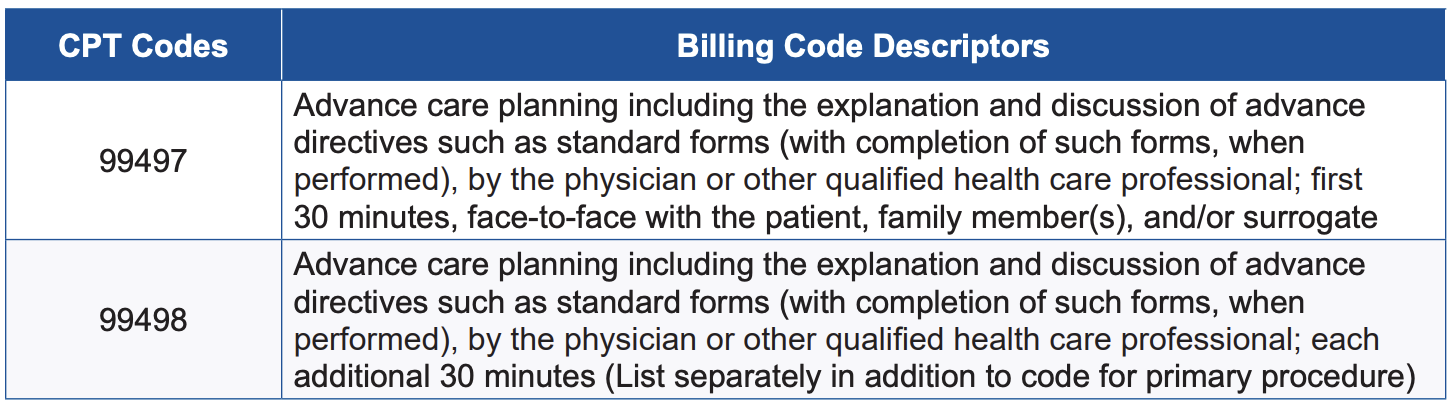

It also directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services to research and assess the implementation of this law and its impact on health decision-making. Additionally, to encourage physicians and qualified health professionals to facilitate ACP conversations and complete AHCDs, CMS introduced and approved two new billing codes in 2016, allowing qualified health providers to bill CMS for advance care planning as a separate service regardless of diagnosis, place of service, or how often services are needed (Figure 1). These codes were expanded in 2017 with the temporary Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G0505, followed by CPT code 99483, to offer care planning and cognitive assessment services that include advance care planning for Medicare beneficiaries with cognitive impairment.

Figure 1. Two primary CPT codes and billing descriptors for advance care planning reimbursement. (Source: CMS Medicare Learning Network Fact Sheet)

In 2022, ACP was introduced as one of four key components of the Care for Older Adults (COA) initiative within the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measures. HEDIS is a proprietary set of clinical care performance measures developed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), a private, nonprofit accreditation organization that creates standardized measures to help health plans assess and report on the quality of care and services. HEDIS evaluates areas such as chronic disease management, preventive care, and care utilization, enabling reliable comparisons of health plan performance and identifying areas for improvement. It is reported that 235 million Americans are enrolled in plans that report HEDIS results, and reporting HEDIS measures is mandatory for Medicare Advantage plans.

The COA initiative includes the ACP measure as a reporting requirement for Medicare Special Needs Plans (SNPs), which are plans designed for individuals who have complex care needs, are eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, have disabling or chronic conditions, and/or live in an institution. The report includes the percentage of Medicare Advantage members within a specified population who participate in ACP discussions each year. This population currently includes:

- Adults aged 65–80 with advanced illness, signs of frailty, or those receiving palliative care.

- All adults aged 81 and older.

HEDIS measures contribute to the overall STAR rating of Medicare Advantage and other health plans, which helps beneficiaries choose high-quality plans, enables highly rated plans to attract more members, and influences the funding and bonuses CMS provides to these plans.

Despite the PSDA, CMS provider reimbursement codes that incentivize physicians and qualified health professionals to facilitate advance care planning, and its recent inclusion in HEDIS measures for Medicare Special Needs Plans, there remain many barriers to completing AHCDs.

Barriers to AHCD Completion

Although Medicare provides health and financial security to nearly all Americans aged 65 and older, completing a comprehensive AHCD is not universally expected within this population. Conversations about treatment decisions in future emergencies and end-of-life care are often avoided for various cultural, religious, financial, and mental health reasons. When they do happen, preferences are more often shared with loved ones but not documented or communicated to healthcare professionals. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that only about half of Medicare beneficiaries have completed an AHCD. Studies show that of those who have, most do so in conjunction with estate planning, which may explain increasing cultural and socioeconomic disparities in the completion of AHCDs.

For Medicare beneficiaries who wish to complete an AHCD with a physician or qualified health professional, Medicare only covers planning as part of the annual wellness visit. If ACP is provided outside of this visit, the beneficiary must meet the Medicare Part B deductible, which is $240 in 2024, before coverage begins. If the deductible has not been met through other Part B services (such as doctor visits, preventive care, mental health services, or outpatient procedures), the beneficiary is responsible for the deductible and a 20% coinsurance payment. Additionally, some states may require attorney services or notarization to legally validate an AHCD, which could incur extra costs.

These additional costs can make it challenging for many Medicare beneficiaries to complete an AHCD when they want to. Furthermore, depending on the complexity of their situation and readiness to make decisions, many patients may need more than one visit with their clinical provider to make decisions about critical illness and end of life care, creating more out-of-pocket expenses.

AHCDs can also vary widely, are not uniform across states, and are often stored in paper formats that can be easily lost or damaged, or are embedded in bulky, multipage estate plans. Efforts to centralize AHCDs have been made through state-based AHCD registries, but their availability and management vary significantly and there is limited data on their use and effectiveness. Additionally, private ACP programs through initiatives like the Uniform Health-Care Decisions Act (UHCDA), the Five Wishes program, MyDirectives, and the U.S. Advance Care Plan Registry (USACPR), among others, have contributed to broadening ACP accessibility and awareness. However, data from private ACP programs are not widely published or have shown variable results. The UHCDA, first drafted and approved in 1993 by the Uniform Law Commission—a nonprofit organization focused on promoting consistency in state laws—was updated in 2023 and aims to address these variations in state AHCD policies, however with varying degrees of success. The Five Wishes program reports 40 million copies of their paper and digital advance directives in circulation nationwide, and their digital program recently launched a partnership with MyDirectives, a leader in digital advance care planning, to facilitate electronic access to legally recognized ACP documents. Unfortunately, data on completion and storage of these directives is not consistently reported across all users.

Despite efforts by numerous organizations to improve ACP completion, access, and usability, the lack of updated federal policy supporting advance care planning makes it difficult for patients to complete them and healthcare providers to quickly locate and interpret them in critical situations. When AHCDs are not available, incomplete, or hard to find, medical professionals may be unaware of patients’ care preferences during urgent moments, leading to treatment decisions that may not align with the patients’ wishes.

Plan of Action

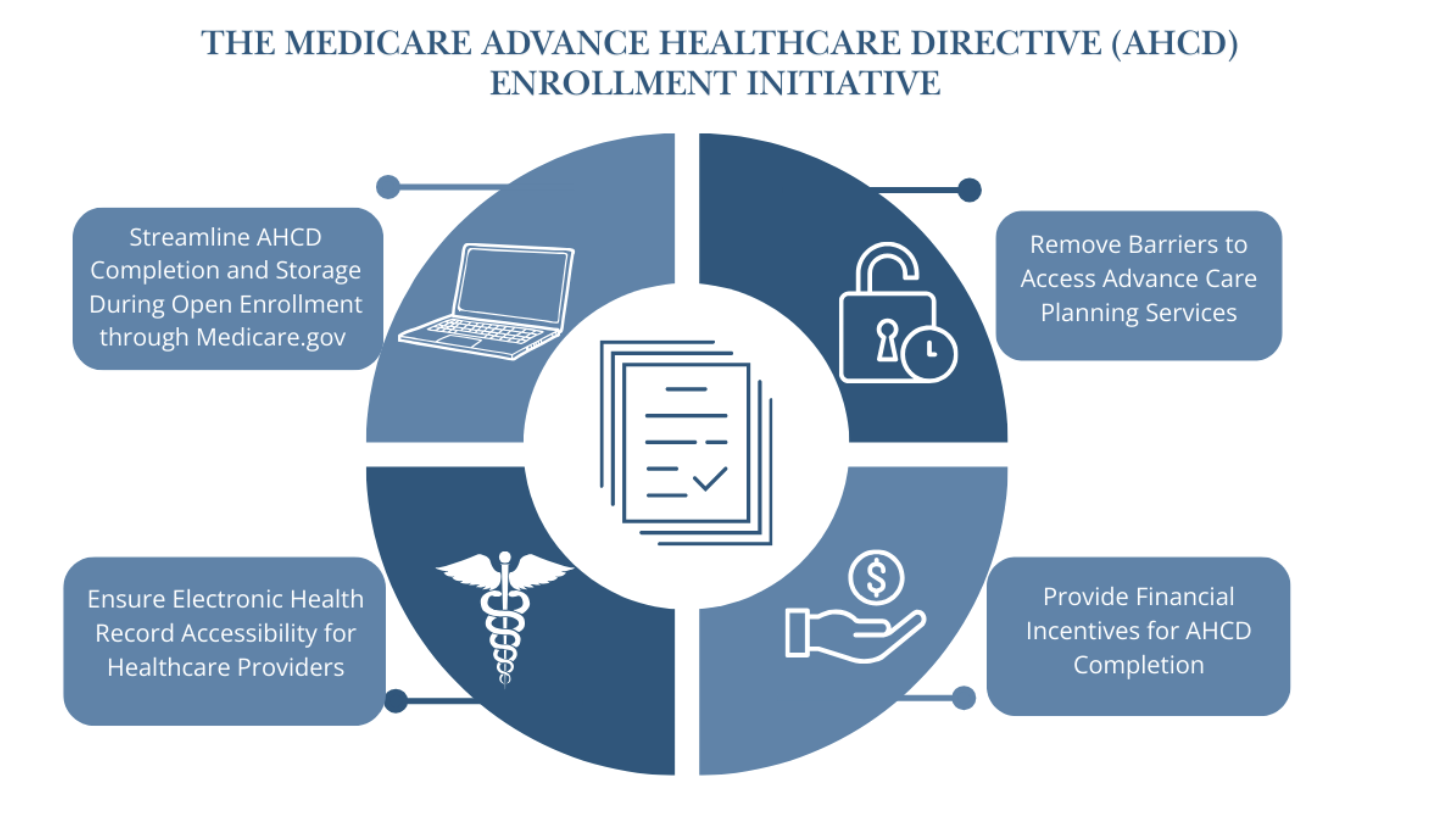

To support all Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older in documenting their end-of-life care preferences, encourage the completion of AHCDs, and improve accessibility of AHCDs for healthcare professionals, CMS should launch the Medicare Advance Healthcare Directive Enrollment Initiative to focus on the following four interventions.

Recommendation 1. Streamline the process of AHCD completion and electronic storage during open enrollment through Medicare.gov or an alternative CMS-approved secure ACP digital platform.

To provide more clarity and support to fulfill patients’ wishes in their end-of-life care, CMS should empower all adults over the age of 65 enrolled in Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans to complete an electronic AHCD and renew it annually, at no extra cost, during Medicare’s designated open enrollment period. Though electronic completion is preferred, paper options will continue to be available and can be submitted for electronic upload and storage.

Supporting the completion of an AHCD during open enrollment presents a strategic opportunity to integrate AHCD completion into overall discussions about healthcare options. New open enrollment tools can be made easily available on Medicare.gov or in partnership with an existing digital ACP platform such as the USACPR, the newly established Five Wishes and MyDirectives partnership, or a centralized repository of state registries, enabling beneficiaries to complete and safely store their directives electronically. User-friendly tools and resources should be tailored to guide beneficiaries through the process and should be age-appropriate and culturally sensitive.

Building on this approach, some states are also taking steps to integrate electronic ACP completion and storage into healthcare enrollment processes. For example, in 2022, Maryland unanimously passed legislation that mandates payers to offer ACP options to all members during open enrollment and at regular intervals thereafter. It also requires payers to receive notifications on the completion and updates of ACP documents. Additionally, providers are required to use an electronic platform to create, upload, and store AHCDs.

An annual electronic renewal process during open enrollment would allow Medicare beneficiaries to review their own selections and make appropriate changes to ensure their choices are up to date. The annual review will also allow for educational opportunities around the risks and benefits of life-extending efforts through the secure Medicare enrollment portal and is a time interval that accounts for the abrupt changes in health status as individuals age. The electronic enhancements also provide a better fit with the modern technological healthcare landscape and can be completed in person or via a telehealth ACP visit with a physician or qualified health professional. Updates to AHCDs can also be made at any time outside of the open enrollment period.

CMS could also work across state lines and in collaboration with private ACP organizations, the UHCDA, and state-appointed AHCD representatives to develop a universal template for advance directives that would be acceptable nationwide. Alternatively, Medicare.gov could provide tailored, state-specific electronic forms to meet state legal requirements, like the downloadable forms provided by organizations such as AARP, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization for Americans over 50, and CaringInfo, a program of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Either approach would ensure AHCDs are legally compliant while centralizing access to the correct forms for easy completion and secure electronic storage.

Recommendation 2. Remove barriers to access advance care planning services.

CMS should remove the deductible and 20% coinsurance when beneficiaries engage in voluntary ACP services with a physician or other qualified health professional outside of their yearly wellness visit.

The current deductible and coinsurance requirements may discourage participants from completing their AHCDs with the guidance of a medical provider, as these costs can be prohibitive. This is similar to how higher cost-sharing and out-of-pocket health expenses often result in cost-related nonadherence, reducing healthcare engagement and prescription medication adherence. When individuals face higher out-of-pocket costs for care, they are more likely to delay treatments, avoid doctor visits, and fill fewer prescriptions, even if they have insurance coverage. Removing deductibles and coinsurance for ACP visits would allow individuals to complete or update their AHCDs as needed, without financial strain and with support from their clinical team, like preventive services.

Additionally, CMS could consider continued health provider education on facilitating ACPs and partnership with organizations like Institute of Healthcare Improvement’s The Conversation Project, which encourages open discussions about end-of-life care preferences. Partnering with Evolent (formerly Vital Decisions) could also support ongoing telehealth discussions between behavioral health specialists and older adults, focusing on late-life and end-of-life care preferences to encourage formal AHCD completion. Internal studies of the Evolent program, aimed at Medicare Advantage beneficiaries, demonstrated an average savings of $13,956 in the final six months of life and projected a potential Medicare spending reduction of up to $8.3 billion.

These enhancements recognize advance care planning as an ongoing process of discussion and documentation that ensures a patient’s care and interventions reflect their values, beliefs, and preferences when unable to make decisions for themselves. It also emphasizes that goals of care are dynamic, and as they evolve, beneficiaries should feel supported and empowered to update their AHCDs affordably and with guidance from educational tools and trained professionals when needed.

Recommendation 3. Ensure electronic accessibility for healthcare providers.

CMS should also integrate the Medicare.gov AHCD storage system or a CMS-approved alternative with existing electronic health records (EHRs).

EHR systems in the United States currently lack full interoperability, meaning that when patients move through the continuum of care—from preventive services to medical treatment, rehabilitation, ongoing care maintenance—and between healthcare systems, their medical records, including AHCDs, may not transfer with them. This makes it challenging for healthcare providers to efficiently access these directives and deliver care that aligns with a patient’s wishes when the patient is incapacitated. To address this, CMS could encourage the integration of the Medicare.gov AHCD storage system or an alternative CMS-approved secure ACP digital platform to interface with all EHRs.

This storage platform could operate as an external add-on feature, allowing AHCDs to be accessible through any EHR, regardless of the healthcare system. Such external add-ons are typically third-party tools or modules that integrate with existing EHR systems to extend functionality, often addressing needs not covered by the core system. These add-ons are commonly used to connect EHRs with tools like clinical decision support systems, telehealth platforms, health information exchanges, and patient communication tools.

Such a universal, electronic system would prevent AHCDs from being misplaced, make them easily accessible across different states and health systems, and allow for easy updates. This would ensure that Medicare beneficiaries’ end-of-life care preferences are consistently honored, regardless of where they receive care.

Recommendation 4. Provide financial incentives for AHCD completion.

CMS should offer financial incentives for completing an AHCD, including options like tax credits, reduced or waived copayments and deductibles, prescription rebates, or other health-related subsidies.

Medicare’s increasing monthly premiums and cost-sharing requirements are often a substantial burden, especially for beneficiaries on fixed incomes. Nearly one in four Medicare enrollees age 65 and older report difficulty affording premiums, and almost 40% of those with incomes below twice the federal poverty level struggle to cover these costs. Additional financial burdens arise from extended care beyond standard coverage limits.

For example, in 2024, Medicare requires beneficiaries to pay $408 per day for inpatient, rehabilitation, inpatient psychiatric, and long-term acute care between days 61–90 of a hospital stay, totaling $11,832. Beyond 90 days, beneficiaries incur $816 per day for up to 60 lifetime reserve days, amounting to $48,720. Once these lifetime reserve days are exhausted, patients bear all inpatient costs, and these reserve days are never replenished again once they are used. Although the average hospital length of stay is typically shorter, inpatient days under Medicare do not need to be consecutive. This means if a patient is discharged and readmitted within a 60-day period, these patient payment responsibilities still apply and will not reset until there has been at least a 60-day break in care.

Medicare coverage for skilled nursing facilities is similarly limited: While Medicare fully covers the first 20 days when transferred from a qualified inpatient stay (at least three consecutive inpatient days, excluding the day of discharge), days 21–100 require a copayment of $204 per day, totaling $16,116. After 100 days, all SNF costs fall to the beneficiary. These costs are significant, and without out-of-pocket maximums, they can create financial hardship.

Some of these costs can be subsidized with Medicare Supplemental Insurance, or Medigap plans, but they come with additional premiums. By regularly educating patients and families of these costs—and offering tax credits, waived or reduced copayments and deductibles, prescription rebates, or account credits—CMS could provide substantial financial relief while encouraging the completion of AHCDs.

Encourage Expansion of the NCQA’s ACP HEDIS Measure

Finally, the MAHDE Initiative can be coupled with the expansion of the HEDIS measure to establish a comprehensive strategy for advancing proactive healthcare planning among Medicare beneficiaries. By encouraging both the accessibility and completion of AHCDs, while also integrating ACP as a quality measure for all Medicare Advantage enrollees aged 65 and older, CMS would embed ACP into standard patient care. This approach would incentivize health plans to prioritize ACP and help align patients’ care goals with the services they receive, fostering a more patient-centered, value-driven model of care within Medicare.

Figure 2. Four key features of the Medicare Advance Healthcare Directive Enrollment (MAHDE) Initiative. This initiative should also work in tandem with efforts to encourage the NCQA to expand ACP HEDIS measures to include all Medicare Advantage beneficiaries aged 65 and older. (Source: Dr. Tiffany Chioma Anaebere)

Conclusion

When patients and their families are clear on their goals of care, it is much less challenging for medical staff to navigate crises and stressful clinical situations. In unfortunate cases when these decisions have not been discussed and documented before a patient becomes incapacitated, doctors witness families struggle deeply with these choices, often leading to intense disagreements, conflict, and guilt. This uncertainty can also result in care that may not align with the patient’s goals.

Physicians and other qualified health professionals should continue to be trained on best practices to facilitate ACP with patients, and more importantly, the system should be redesigned to support these conversations early and often for all older Americans. The MAHDE Initiative is feasible, empowers patients to engage in ACP, and will reduce medical costs nationwide by allowing patients to be educated about their options and choose the care they want in future emergencies and at the end of life.

Starting an AHCD enrollment initiative with the Medicare population older than age 65 and achieving success in this group can pave the way for expanding ACP efforts to other high-need groups and, eventually, the general population. This approach fosters a healthcare environment where, as a nation, we become more comfortable discussing and managing healthcare decisions during emergencies and at the end of life.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

No. While the MAHDE Initiative will encourage all adults over age 65 who are enrolled in Medicare or Medicare Advantage plans to complete or renew an electronic AHCD annually through Medicare.gov or an alternative CMS-approved secure ACP digital platform, it will not be a requirement for receiving Medicare benefits or care.

Working alongside state-specific submission guidelines, Medicare beneficiaries can securely complete their AHCD on their own or during a visit with a qualified medical provider or health professional, either in person or through telehealth.

- Online submission: An accessible electronic version will be available on Medicare.gov or an alternative CMS-approved secure ACP digital platform, allowing individuals to complete and submit their AHCD online, with guidance from their care provider as needed.

- Paper version: Alternatively, individuals can also choose to complete a paper version of the AHCD, which can then be submitted to Medicare or a CMS-approved alternative for well-digitized electronic upload, storage, and access by healthcare professionals on Medicare.gov.

Review, updates, or to or confirm “no change” to these directives can be made annually online or by resubmitting updated paper forms during open enrollment or anytime as desired. Flexible options aim to make the process of AHCD completion accessible and convenient for all Medicare beneficiaries.

The author does not endorse specific products, individuals, or organizations. Any references are intended as examples or options for further exploration, not as endorsements or formal recommendations.

The Federation of American Scientists supports Congress’ ongoing bipartisan efforts to strengthen U.S. leadership with respect to outer space activities.

By preparing credible, bipartisan options now, before the bill becomes law, we can give the Administration a plan that is ready to implement rather than another study that gathers dust.

Even as companies and countries race to adopt AI, the U.S. lacks the capacity to fully characterize the behavior and risks of AI systems and ensure leadership across the AI stack. This gap has direct consequences for Commerce’s core missions.

As states take up AI regulation, they must prioritize transparency and build technical capacity to ensure effective governance and build public trust.