Enhanced Household Air Conditioning Access Data for More Targeted Federal Support Against Extreme Heat

While access to cooling is the most protective factor against extreme heat events, the U.S. Census lacks granular, residential data to determine who has access to air conditioning (AC). The addition of a question about household access to working AC to the Census American Community Survey, a nationally representative survey on the social, economic, housing, and demographic characteristics of the population, would have life-saving impacts.

This is especially essential as the U.S. is experiencing more frequent and intense extreme heat events, and extreme heat now kills more people than all other weather-related hazards. Many vulnerable demographics — including people who are elderly, low-income, African-American, socially isolated, as well as those with preexisting health conditions— are exposed to high temperatures within their homes.

Better data on working AC infrastructure in American homes would improve how the federal government and its state and local partners target local social services and interventions, such as emergency responder deployment during high-heat events, as well as distribute federal assistance funds, such as the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), and funding from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) along with the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL).

Challenge and Opportunity

In 2019, the U.S. Census Bureau acknowledged the danger of heat by issuing the Community Resilience Estimates (CRE) for Heat. The CRE for Heat is a measure that combines 10 questions from the existing American Community Survey questions. The questions ask about:

- Financial hardship

- Older residents living alone

- Crowding

- Whether the home is a mobile home, boat, or recreational vehicle

- Employment status for those under 65 years old

- Whether a resident has a disability

- Whether a resident has health insurance

- Access to a vehicle

- Connection via broadband internet access

- Communication barriers

However, the CRE for Heat lacks a question about air conditioning, the most important protective factor. Indoor temperature regulation is essential for mitigating heat illness and death on extremely hot days – temperatures above 86°F indoors can easily become dangerous and deadly.

Currently, the best information on residential AC is provided by the biennial American Housing Survey (AHS). In 2019, the AHS reported that 8.8% (11.6 million households) of all U.S. housing units have no form of AC. However, this information has three significant weaknesses. First, the American Housing Survey is based on 2,000 homes sampled across a metropolitan area. The sampling process generates an average across high-, medium-, and low-income residents; therefore, it overestimates the presence of AC in lower-income households. American households with higher incomes are more likely to have access to AC: 92.2% of households with incomes greater than $100,000 have some form of AC, compared with 88.9% of households with incomes less than $30,000. Second, lower-income households may have broken AC systems or units and lack money for repairs, skewing collected data. Third, the AHS fails to consider how poverty constrains electricity consumption. Many lower-income households reduce or abstain from using their AC in fear of costly electricity bills that trigger shutoffs. For instance, a 2022 report found that nearly 20% of households earning less than $25,000 reported keeping their indoor temperatures at levels that felt unsafe for several months of the year. These three weaknesses of the AHS data underscore the need for fine-grained information on who has access to working AC, especially in lower-income households.

The U.S. Census American Community Survey (ACS), on the other hand, samples 3.5 million addresses every year in a nationally representative annual survey. The ACS asks about housing characteristics, costs, and conditions (including heating) but not about AC nationwide. The equivalent survey administered in the four Island Areas of Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and American Samoa — known as the “Island Areas Census” — included an AC question until 2010. This is an important precedent for adding a similar question to all Census surveys and should expedite the process. However, adding the term “working” (or a similar word) to the air-conditioning question would enhance its ability to capture low-income homes with broken systems as well as households that cannot use their existing AC due to energy insecurity.

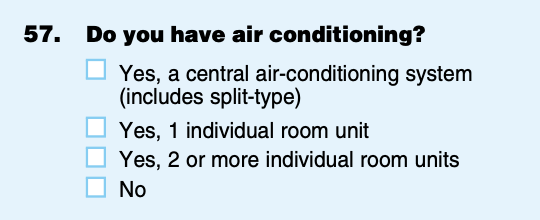

Former question on air-conditioning in the American Community Survey for U.S. Island Areas

Better Information for Better Distribution of LIHEAP and WAP Funding

In addition to helping emergency responders, city planners, and public health departments, information collected on the presence of working AC could help ensure that the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Low Income Heat Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) and Department of Energy’s (DOE) Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) serve the most vulnerable residents.

LIHEAP, administered by the Office of Community Services (OCS) within the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), is designed to “assist low-income households, particularly those in the lowest incomes, that pay a high proportion of household income for home energy, primarily in meeting their home energy needs.” LIHEAP is a targeted block grant program whereby states distribute their funds across three programs that subsidize home energy heating or cooling costs; fund payment in crises; and support home weatherization (limited to 15% of funds unless a state requests a waiver to increase their percentage to 25%). The largest proportion of the funds subsidizes lower-income, vulnerable residents’ energy spending. While LIHEAP is an important federal program that impacted 7.1 million American households in 2023, only approximately 20% of eligible households received LIHEAP assistance, and the program is currently facing budget shortfalls of $2 billion.

By expanding cooling assistance, LIHEAP is being asked to do more with less: 24 of 50 states now include cooling assistance, and 9.8% of funds subsidized cooling costs. As extreme heat events become more frequent and severe and households become more energy insecure in the face of rising energy prices, more states will need to expand cooling assistance programs. Data on where households are most vulnerable — that is, those households without working AC or the financial ability to operate their AC — would enable targeted distribution of federal funds. Therefore, adding a Census question on household access to working AC would provide critical information to ensure LIHEAP funds serve the most vulnerable households.

Unlike LIHEAP, WAP’s sole focus is weatherization. Many weatherization improvements that help in cold weather also improve indoor thermal comfort during warm summer months. These improvements include fixing broken AC; adding insulation in walls, attics, and crawlspaces; and replacing leaky, inoperable windows. Compared to LIHEAP, WAP serves a much smaller number of homes — 35,000 homes annually versus LIHEAP’s 7.1 million (as of FY2023). Knowing the number of individual households in a census tract in need of investments in heat resilience adaptation and air-conditioning would enable much more targeted delivery of limited federal resources. Further, DOE can use this information to predict future grid demand and enhance necessary resilience measures for hotter summers.

Plan of Action

To save lives in the face of growing extreme heat, the Census should add a question about working AC to the American Community Survey. This could be executed as follows:

Recommendation 1. The Office of Community Services in the Administration for Children and Families (OCS ACF) requests the addition of a question about access to working AC at the census tract level to the American Community Survey. This would directly aid the LIHEAP program’s mandate to identify and serve vulnerable individuals, and benefit other programs like DOE’s WAP as well as programs authorized by the IRA and BIL.

Recommendation 2. Legal staff in the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Census Bureau review the proposal to determine whether it meets legislative requirements.

Recommendation 3. After a successful legal review, OMB and the Census Bureau, in consultation with the Interagency Council on Statistical Policy Subcommittee for the American Community Survey, determine whether the request merits consideration.

Recommendation 4. Subject matter experts across relevant federal government programs (i.e. LIHEAP and WAP) and external institutions (housing experts, extreme heat experts, social vulnerability experts) identify ways to ask the question. The Census Bureau conducts interviews to determine which wording produces the most accurate results. Because a similar question (but lacking the term “working”) is used on the American Community Survey for Island Areas, this process may be expedited. A potential example of the new question is below:

Do you have working air air-conditioning?

- Yes, a central air conditioning system (includes split-type)

- Yes, 1 individual room unit

- Yes, 2 or more individual room units

- No, my air conditioning system is non-functional or broken

- No, I cannot afford to run my air-conditioning system

- No, I do not have any air-conditioning system

Recommendation 5. The Census Bureau solicits public comment on the question and request OMB’s approval for field testing.

Recommendation 6. The Census Bureau and ACF OCS review the results and decide whether to recommend adding the new survey question. Through the Federal Register Notice, the Census Bureau solicits public comment. Public comments inform the final decision that is made in consultation with the OMB and the Interagency Council on Statistical Policy Subcommittee on the American Community Survey.

Recommendation 7. If approved by OMB, the Census Bureau adds the question to its materials, and implementation begins at the start of the following calendar year (October).

Recommendation 8. The Community Resilience Estimates (CRE) for Heat is updated with information about AC as it becomes available. This tool can be shared, along with refined guidance, with state-level administrators of programs like LIHEAP and WAP to target investments to the households most vulnerable to overheating and resulting heat illness and death. The CDC could integrate AC coverage within its existing syndromic surveillance programs on extreme heat, as an additional layer of “risk” for targeted public health deployment during high-heat events.

Conclusion

The U.S. lacks fine-scaled data to determine whether households can access working AC systems/units and operate them during extreme heat events. Adding a question to the American Community Survey will provide life-saving information for emergency responders, social service providers, and city staff as extreme heat events become more frequent and intense. This fine-scaled information will also aid in distributing LIHEAP and WAP funding and increase the federal government’s ability to protect the most vulnerable residents from life-threatening extreme heat events.

This idea of merit originated from our Extreme Heat Ideas Challenge. Scientific and technical experts across disciplines worked with FAS to develop potential solutions in various realms: infrastructure and the built environment, workforce safety and development, public health, food security and resilience, emergency planning and response, and data indices. Review ideas to combat extreme heat here.

FAS is launching the Center for Regulatory Ingenuity (CRI) to build a new, transpartisan vision of government that works – that has the capacity to achieve ambitious goals while adeptly responding to people’s basic needs.

This runs counter to public opinion: 4 in 5 of all Americans, across party lines, want to see the government take stronger climate action.

Cities need to rapidly become compact, efficient, electrified, and nature‑rich urban ecosystems where we take better care of each other and avoid locking in more sprawl and fossil‑fuel dependence.

Hurricanes cause around 24 deaths per storm – but the longer-term consequences kill thousands more. With extreme weather events becoming ever-more common, there is a national and moral imperative to rethink not just who responds to disasters, but for how long and to what end.