Using Other Transactions at DOE to Accelerate the Clean Energy Transition

Summary

The Department of Energy (DOE) should leverage its congressionally granted other transaction authority to its full statutory extent to accelerate the demonstration and deployment of innovations critical to the clean energy transition. To do so, the Secretary of Energy should encourage DOE staff to consider using other transactions to advance the agency’s core missions. DOE’s Office of Acquisition Management should provide resources to educate program and contracting staff on the opportunity that other transactions present. Doing so would unlock a less used but important tool in demonstrating and accelerating critical technology developments at scale with industry.

Challenge and Opportunity

OTs are an underleveraged tool for accelerating energy technology.

Our global and national clean energy transition requires advancing novel technology innovations across transportation, electricity generation, industrial production, carbon capture and storage, and more. If we hope to hit our net-zero emissions benchmarks by 2030 and 2050, we must do a far better job commercializing innovations, mitigating the risk of market failures, and using public dollars to crowd in private investment behind projects.

The Biden Administration and the Department of Energy, empowered by Congress through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), have taken significant steps to meet these challenges. The Loan Programs Office, the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, the Office of Technology Transitions, and many more dedicated public servants are working hard towards the mission set forward by Congress and the administration. They are deploying a range of grants, procurement contracts, and tax credits to achieve their goals, and there are more tools at their disposal to accelerate a just, clean energy transition. The large sums of money appropriated under BIL and IRA require new ways of thinking about contracting and agreements.

Congress gives several federal agencies the authority to use flexible agreements known as other transactions (OTs). Importantly, OTs are defined by what they are not. They are not a government contract or grant, and thus not governed by the Federal Acquisitions Regulations (FAR). Historically, NASA and the DoD have been the most frequent users of other transaction authorities, including for projects like the Commercial Orbital Transportation System at NASA which developed the Falcon 9 space vehicle, and the Global Hawk program at DARPA.

In contrast, the Department of Energy has infrequently used OTs, and even when it has, the programs have achieved no notable outcomes in support of their agency mission. When the DOE has used OTs, the agency has interpreted their authority as constraining them to cost-sharing research agreements. This restricts the creativity of agency staff in executing OTs. All the law says is that an OT is not a grant or contract. By limiting itself to cost sharing research agreements, DOE is preemptively foreclosing all other kinds of novel partnerships. This is critical because some nascent climate-solution technologies may face a significant market failure or a set of misaligned incentives that a traditional research and development transaction (R&D) may not fix.

This interpretation has hampered DOE’s use of OTs, limited its ability to engage small businesses and nontraditional contractors, and prevented DOE from fully pursuing its agency mission and the administration’s climate goals.

Exploring further use of OTs would open up a range of possibilities for the agency to help address critical market failures, help U.S. firms bridge the well-documented valleys of death in technology development, and fulfill the benchmarks laid out in the DOE’s Pathways to Commercial Liftoff.

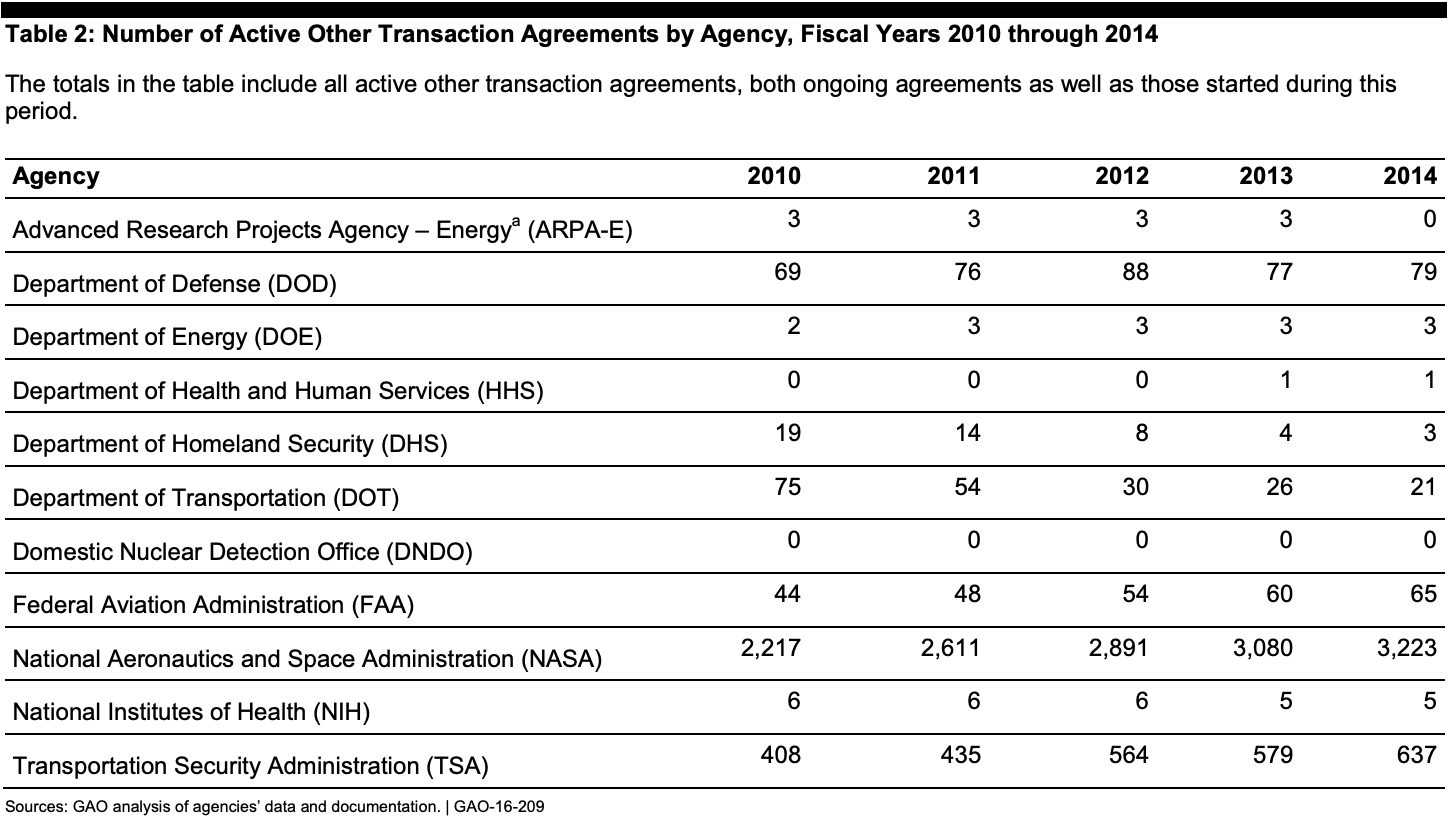

According to a GAO report from 2016, the DOE has only used OTs a handful of times since they had the authority updated in 2005, nearly two decades ago. Compare the DOE’s use of OTs to other agencies in the four-year period in the table below (the most recent for which there is open data).

From GAO-16-209

Almost every other agency uses OTs at a significantly higher rate, including agencies that have smaller overall budgets. While quantity of agreements is not the only metric to rely on, the magnitude of the discrepancy is significant.

Other agencies have made significant changes since 2014, most notably the Department of Defense. A 2020 CSIS report found that DoD use of OTs for R&D increased by 712% since FY2015, including a 75% increase in FY2019. This represents billions of dollars in awards, much of which went to consortia, including for both prototyping and production transactions. While the DOE does not have the same budget or mission as DoD, the sea change in culture among DoD officials willing to use OTs over the past few years is instructive. While DoD did receive expanded authority in the FY2015 and 2016 NDAA, this alone did not account for the massive increase. A cultural shift drove program staff to look at OTs as ways to quickly prototype and deploy solutions that could advance their missions, and support from leadership enabled staff to successfully learn how and when to use OTs.

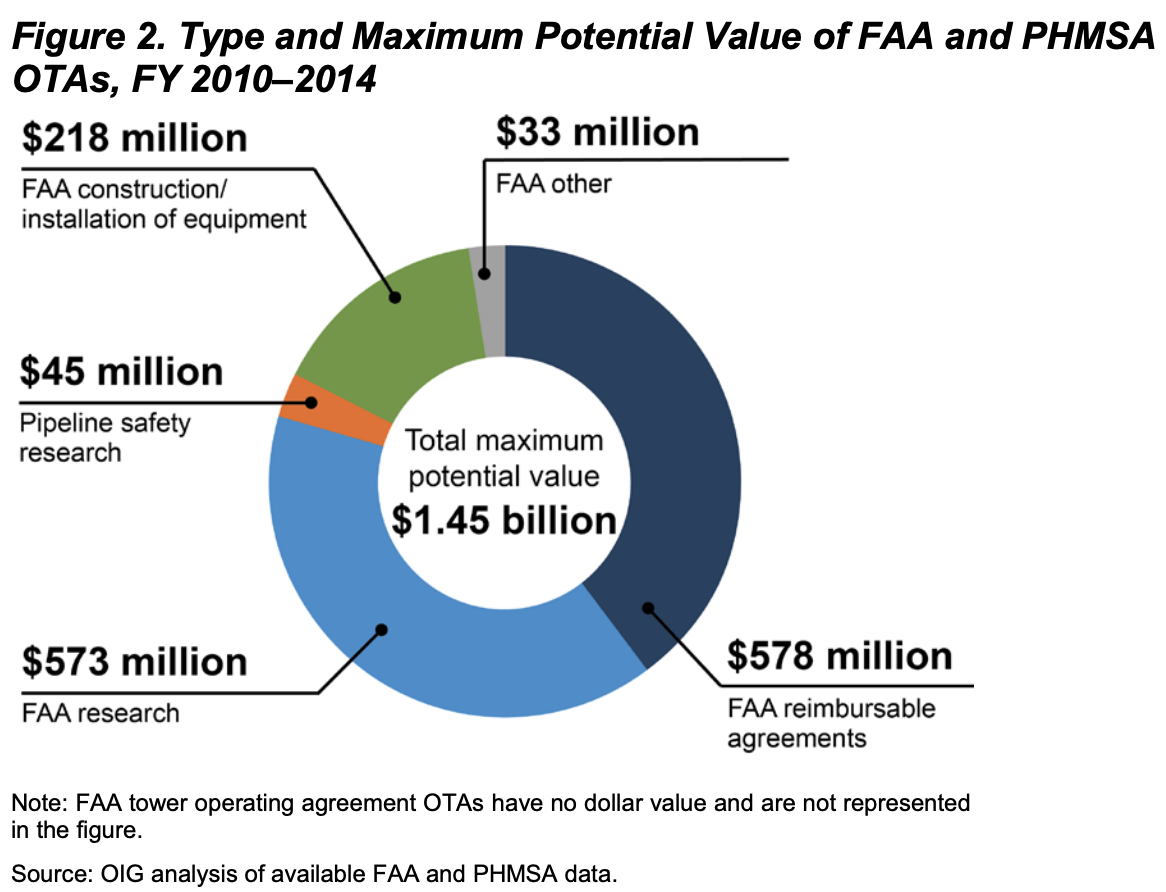

The Department of Transportation (DOT) only uses OTs for two agencies, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHIMSA). Like DOE, the FAA is not restricted in what it can and can’t use OTs for. It is authorized to “carry out the functions of the Administrator and the Administration…on such terms and conditions as the Administrator may consider appropriate.” Unlike DOE, the FAA and DOT have used their authority for several dozen transactions a year, totaling $1.45 billion in awards between 2010 and 2014.

From the GAO chart (Table 1), it’s clear that ARPA-E also follows the DOE in deploying very few OTs in support of its mission. Despite being originally envisioned as a high-potential, high-impact funder for technology that is too early in the R&D process for private investors to support, the most recent data shows that ARPA-E does not use OTs flexibly to support high-potential, high-impact tech.

The same GAO report cited above stated that:

“DOE’s regulations—because they are based on DOD’s regulations—include requirements that limit DOE’s use of other transaction agreements…. Officials told us they plan to seek approval from the Office of Management and Budget to modify the agency’s other transaction regulations to better reflect DOE’s mission, consistent with its statutory authority. According to DOE officials, if the changes are approved, DOE may increase its use of other transaction agreements.”

That report was published in 2016, but it is unclear that any changes were sought or approved, though they likely do not need to change any regulations at all to actually make use of their authority.1 The realm of the possible is quite large, and DOE has yet to fully explore the potential benefits to its mission that OTs provide.

DOE can use OTs without any further authority to drive progress in critical technologies.

The good news is that DOE has the ability to use OTs without further guidance from Congress or formally changing any guidelines. Recognizing their full statutory authority would open up use cases for OTs that would help the DOE make meaningful progress towards its agency mission and the administration’s climate goals.

For example, the DOE could use OTs in the following ways:

- Using demand-side support mechanisms to reduce the “green premium” for promising technologies like hydrogen, carbon capture, sustainable aviation fuel, enhanced geothermal, and low-embodied construction materials like steel and concrete

- Coordinating the demonstration of promising technologies through consortia with private industry in support of their commercial liftoff goals

- Organizing joint demonstration projects with the DOT or other agencies with overlapping solution sets

- Rapidly and sustainably meeting critical energy infrastructure needs across rural areas

Given the exigencies of climate change and the need to rapidly decarbonize our society and economy, there are very real instances in which traditional research contracts or grants are not enough to move the needle or unlock a significant market opportunity for a technology. Forward contract acquisitions, pay for delivery contracts, or other forms of transactions that are nonstandard but critical to supporting development of technology are covered under this authority.

One promising area where it seems the DOE is currently using this approach is in supporting the hydrogen hubs initiative. Recently the DOE announced a $1 billion initiative for demand-side support mechanisms to mitigate the risk of market failures and accelerate the commercialization of clean hydrogen technologies. The Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) for the H2Hubs program notes that “other FOA launches or use of Other Transaction Authorities may also be used to solicit new technologies, capabilities, end-uses, or partners.” The DOE could use OTs more frequently as a tool to advance other critical commercial liftoff strategies or to maximize the impact of dollars appropriated to implementation of the BIL and IRA. Some areas that are ripe for creative uses of other transactions include:

- Critical Minerals Consortium: A critical minerals consortium of vendors, nonprofits, academics, and others all managed by a single entity could do more than just mineral processing improvement and R&D. It could take long-term offtake agreements and do forward purchasing of mineral supplies like graphite that are essential to the production of electric vehicle (EV) batteries and other products. This could function similarly to the successful forward contract acquisition for the Strategic Petroleum Reserve executed in June 2023 by DOE.

This demand-pull would complement other recent actions taken to bolster critical minerals like the clean vehicle tax credit and the Loan Program Office’s loans to mineral processing facilities. Such a consortium could come from the existing critical materials institute or be formed by separate entities.

- Geothermal Consortium: Enhanced geothermal systems technology has received neither the attention nor the investment that it should proportional to its potential benefits as a path towards decarbonizing the electric grid. At the same time, legacy oil and natural gas industries have workforces, equipment, and experiences that can easily translate to growing the geothermal energy industry. Recently, the DOE funded the first cross-industry consortium with the $165 million GEODE competition grant awarded to Project Innerspace, Geothermal Rising, and the Society of Petroleum Engineers.

DOE could use other transactions to further support this nascent consortium and increase the demonstration and deployment of geothermal projects. The agency could also use other transactions to organize the sharing of critical subsurface data and resources through a single entity.

- Direct Air Capture (DAC): The carbon removal market faces extremely uncertain long-term demand, and unproven technological innovations may or may not present economically viable means of pulling carbon out of the atmosphere. In order to accelerate the pace of carbon removal innovation, aggregated demand structures like Frontier’s advanced market commitment have stepped up to organize pre-purchasing and offtake agreements between buyers and suppliers. The scale of the problem is such that government intervention will be necessary to capture carbon at a rate that experts believe is necessary to mitigate the worst warming pathways.

A carbon removal purchasing agreement for the DOE’s Regional Direct Air Capture Hubs could function much the same as the proposed hydrogen hubs initiative. It also could take the shape of a consortium of DAC vendors, nonprofits, scientists, and others managed by a single entity that can set standards for purchase agreements. This would cut the negotiation time among potential parties by a significant amount, allowing for cost saving and faster decarbonization.

- Rural Energy Improvements Consortium: The IRA appropriated $1 billion for energy improvements in rural and remote areas. Because of inherent resource limitations, the DOE will not be able to fund every potential compelling project that applies to this grant program. In order to keep the program from making single one-off grants for narrowly tailored projects, it could focus on funding projects with demonstrated catalytic impact. Through OTs, the DOE could encourage promising project developers to form a Rural Energy Improvement/Developers consortium that would not only help create efficiencies in renewable energy development and novel resilient local structures but attract private investment at a scale that each individual developer would not independently attract.

- Hydrogen Fuel Cell Lifespan Consortia: As hydrogen fuel cells start gaining traction across transportation, shipping, and industrial applications, a consortia for fuel cell R&D could help provide new insights into the degradation of fuel cells, organize uniform standards for recycling of fuel cells, and also provide unique financial incentives to hedge against early uncertainty of fuel cell lifespans. As firms invest in new fleets of fuel cell vehicles, it may help them to have an idea of what expected value they can receive for assets as they reach the end of their lifespans. A backstopped guarantee of a minimum price for assets with certain criteria could reduce uncertainty. Such a consortium could be led by the Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains (MESC) and complement existing initiatives to accelerate domestic manufacturing.

- Long Duration Energy Storage (LDES): The DOE commercial liftoff pathway highlights the need to intervene to address stakeholder and investor uncertainty by providing long-term market signals for LDES. The tools they highlight to do so are carbon pricing, greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets, and transmission expansion. While these provide generalizable long-term signals, DOE could leverage OTs to provide more concrete signals for the value of LDES.

DOE could organize an advance market commitment for long-duration energy storage capabilities on federal properties that meet certain storage hour and grid integration requirements. Such a commitment could include the DoD and the General Services Administration (GSA), which own and operate the large portfolio of federal properties, including bases and facilities in hard-to-reach locations that could benefit from more predictable and secure energy infrastructure. Early procurement of capability-meeting but expensive systems could help diversify the market and drive technology down the cost curve to reach the target of $650 per kW and 75% RTE for intra-day storage and $1,100 per kW 55 and 60% RTE for multiday storage.

To use OTs more frequently, the DOE needs to focus on culture and education.

As noted, the DOE does not need additional authorization or congressional legislation to use OTs more frequently. The agency received authority in its original charter in 1977, codified in 42 U.S. Code § 7256, which state:

“The Secretary is authorized to enter into and perform such contracts, leases, cooperative agreements, or other similar transactions with public agencies and private organizations and persons, and to make such payments (in lump sum or installments, and by way of advance or reimbursement) as he may deem to be necessary or appropriate to carry out functions now or hereafter vested in the Secretary.” [emphasis added]

This and other legislation gives DOE the authority to use OTs as the Secretary deems necessary.

Later guidelines in implementation state that other officials at DOE who have been presidentially appointed and confirmed by the Senate are able to execute these transactions. The DOE’s Office of Acquisition Management, Office of General Counsel, and any other legal bodies involved should update any unnecessarily restrictive guidelines, or note that they will follow the original authority granted in the agency’s 1977 charter.

While that would resolve any implementation questions about the ability to use OT at DOE, the agency ultimately needs strong leadership and buy-in from the Secretary in order to take full advantage. As many observers note regarding DoD’s expanding use of OTs, culture is what matters the most. The DOE should take the following actions to make sure the changing of these guidelines empowers DOE public servants to their full potential:

- The Secretary should make clear to DOE leadership and staff that increased use of OTs is not only permissible but actively encouraged.

- The Secretary should provide internal written guidance to DOE leadership and program-level staff on what criteria need to be met for her to sign off on an OT, if needed. These criteria should be driven by DOE mission needs, technology readiness, and other resources like the commercial liftoff reports.

- The Office of Acquisition Management should collaboratively educate relevant program staff, not just contracting staff, on the use of OTs, including by providing cross-agency learning opportunities from peers at DARPA, NASA, DoD, DHS, and DOT.

- DOE should provide an internal process for designing and drawing up an OT agreement for staff to get constructive feedback from multiple levels of experienced professionals.

- DOE should issue a yearly report on how many OTs they agree to and basic details of the agreements. After four years, GAO should evaluate DOE’s use of OTs and communicate any areas for improvement. Since OTs don’t meet normal contracting disclosure requirements, some form of public disclosure would be critical for accountability.

Mitigating risk

Finally, there are many ways to address potential risks involved with executing new OTs for clean energy solutions. While there are no legal contracting risks (as OTs are not guided by the FAR), DOE staff should consider ways to most judiciously and appropriately enter into agreements. For one resource, they can leverage the eight recent reports put together by four different offices of inspector generals on agencies’ usage of other transactions to understand best practices. Other important risk limiting activities include:

- DoD commonly uses consortiums to gather critical industry partners together around challenges in areas such as advanced manufacturing, mobility, enterprise healthcare innovations, and more.

- Education of relevant parties and modeling of agreements after successful DARPA and NASA OTs. These resources are in many cases publicly available online and provide ready-made templates (for example, the NIH also offers a 500-page training guide with example agreements).

Conclusion

The DOE should use the full authority granted to it by Congress in executing other transactions to advance the clean energy transition and develop secure energy infrastructure in line with their agency mission. DOE does not need additional authorization or legislation from Congress in order to do so. GAO reports have highlighted the limitations of DOE’s OT use and the discrepancy in usage between agencies. Making this change would bring the DOE in line with peer agencies and push the country towards more meaningful progress on net-zero goals.

The following examples are pulled from a GAO report but should not be regarded as the only model for potential agreements.

Examples of Past OTs at DOE

“In 2010, ARPA-E entered into an other transaction agreement with a commercial oil and energy company to research and develop new drilling technology to access geothermal energy. Specifically, according to agency documentation, the technology being tested was designed to drill into hard rock more quickly and efficiently using a hardware system to transmit high-powered lasers over long distances via fiber optic cables and integrating the laser power with a mechanical drill bit. According to ARPA-E documents, this technology could provide access to an estimated 100,000 or more megawatts of geothermal electrical power in the United States by 2050, which would help ARPA-E meet its mission to enhance the economic and energy security of the United States through the development of energy technologies.

According to ARPA-E officials, an other transaction agreement was used due to the company’s concerns about protecting its intellectual property rights, in case the company was purchased by a different company in the future. Specifically, one type of intellectual property protection known as “march-in rights” allows federal agencies to take control of a patent when certain conditions have not been met, such as when the entity has not made efforts to commercialize the invention within an agreed upon time frame.33 Under the terms of ARPA-E’s other transaction agreement, march-in rights were modified so that if the company itself was sold, it could choose to pay the government and retain the rights to the technology developed under the agreement. Additionally, according to DOE officials, ARPA-E included a United States competitive clause in the agreement that required any invention developed under the agreement to be substantially manufactured in the United States, provided products were also sold in the United States, unless the company showed that it was not commercially feasible to do so. This agreement lasted until fiscal year 2013, and ARPA-E obligated about $9 million to it.”

Examples at DoD

“In 2011, DOD entered into a 2-year other transaction agreement with a nontraditional contractor for the development of a new military sensor system. According to the agreement documentation, this military sensor system was intended to demonstrate DOD’s ability to quickly react to emerging critical needs through rapid prototyping and deployment of sensing capabilities. By using an other transaction agreement, DOD planned to use commercial technology, development techniques, and approaches to accelerate the sensor system development process. The agreement noted that commercial products change quickly, with major technology changes occurring in less than 2 years. In contrast, according to the agreement, under the typical DOD process, military sensor systems take 3 to 8 years to complete, and may not match evolving mission needs by the time the system is complete. According to an official, DOD obligated $8 million to this agreement.”

Other interpretations of the statute have prevented DOE from leveraging OTs, and there seems to be confusion on what is allowed. For example, a commonly cited OTA explainer implies that DOE is statutorily limited to “RD&D projects. Cost sharing agreement required.”

But nowhere in the original statute does Congress require DOE to exclusively use cost sharing agreements, nor is this the case at other agencies where OTs are common practice.

However, the Energy Policy Act of 2005 did require the DOE to issue guidelines for the use of OTs 90 days after the passing of the law, and this is where it gets complicated. They did so, and according to a 2008 GAO report, DOE enacted guidelines which used a specific model called a technology investment agreement (TIA). These guidelines were modeled on the DoD’s then-current guidelines for OTs and TIAs, mandating cost sharing agreements “to the maximum extent practicable” between the federal government and nonfederal parties to an agreement.2 An Acquisition/Financial Assistance Letter issued by senior DOE procurement officials in 2021 defines this explicitly: “Other Transaction Agreement, as used in this AL/FAL, means Technology Investment Agreement as codified at 10 C.F.R., Part 603, pursuant to DOE’s Other Transaction Authority of 42 U.S.C. § 7256.” However, the DOE’s authority as codified in 42 U.S.C. § 7256 (a) and (g) does not define OTs as TIAs, the definition is just a guideline from DOE, and could be changed.

Technology Investment Agreements are used to reduce the barrier to commercial and nontraditional firms’ involvement with mission-critical research needs at DOE. They are particularly useful in that they do not require traditional government accounting systems, which can be burdensome for small or new firms to implement. But that does not mean they are the only instrument that should be used. The law says that TIAs for research projects should involve cost sharing to the “maximum extent practicable.” This does not mean that cost sharing must always occur. There could be many forms of transactions other than grants and contracts in which cost sharing is neither practicable nor feasible.

Furthermore, the DOE is empowered to use OTs for research, applied research, development, and demonstration projects. Development and demonstration projects would not fit neatly in the category of research projects covered by TIAs. So subjecting them to the same guidelines is an unduly restrictive guideline.

Consortia are basically single entities that manage a group of members (to include private firms, academics, nonprofits, and more) aligned around a specific challenge or topic. Government can execute other transactions with the consortium manager, who then organizes the members around an agreed scope. MITRE provides a longer explainer and list of consortia.

How DOE can emerge from political upheaval achieve the real-world change needed to address the interlocking crises of energy affordability, U.S. competitiveness, and climate change.

As Congress begins the FY27 appropriations process this month, congress members should turn their eyes towards rebuilding DOE’s programs and strengthening U.S. energy innovation and reindustrialization.

Politically motivated award cancellations and the delayed distribution of obligated funds have broken the hard-earned trust of the private sector, state and local governments, and community organizations.

Over the course of 2025, the second Trump administration has overseen a major loss in staff at DOE, but these changes will not deliver the energy and innovation impacts that this administration, or any administration, wants.