Response to Critiques Against Fordow Analysis

by Ivanka Barzashka and Ivan Oelrich

Our article “A Technical Evaluation of the Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant” published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists on November 23 and its technical appendix, an Issue Brief, “Calculating the Capacity of Fordow”, published on the FAS website, have sparked quite a discussion among the small community that follows the technical details of Iran’s program, most prominently by Joshua Pollack and friends on armscontrolwonk.com (on December 1 and December 6) and by David Albright and Paul Brannan at ISIS, who have dedicated two online reports (from November 30 and December 4) to critiquing our work.

Before addressing the arguments and exposing the fallacies in ISIS’s critique directly, we strongly encourage interested parties to read our Issue Brief, in which we have presented our reasoning, calculations, and assumptions in a clear and straight-forward way that we believe anyone with some arithmetic skills and a pocket calculator can follow and reproduce. We published a quick first version of our Issue Brief on 1 December. The 4 December ISIS rebuttal was based on this first version. We published an expanded version of the Issue Brief on 7 December. The second version adds to the first version, but everything in the first brief is also in the second one. The second version includes additional examples and further details on how we carried out our calculations (as well as cleaning up some formatting, for example, all the tables in the first version were in different formats; if nothing else, the revision at least looks much prettier). References to equations and page numbers below pertain to the revised Issue Brief.

In our Bulletin piece, we concluded that Fordow is ill-suited for either a commercial or military program and we speculated that it would make most sense if it were one of several facilities planned. The latter conclusion has been de facto supported by Iran’s recent declaration of 10 additional planned enrichment sites. Although ISIS explicitly states that our assessment of Fordow is unrealistic, the authors are not clear what their broader argument is. They seem to imply that Fordow alone is sufficient for a viable breakout option, which in the context of our Bulletin article would make Iranian intentions clear-cut but would, however, undermine the need for additional facilities.

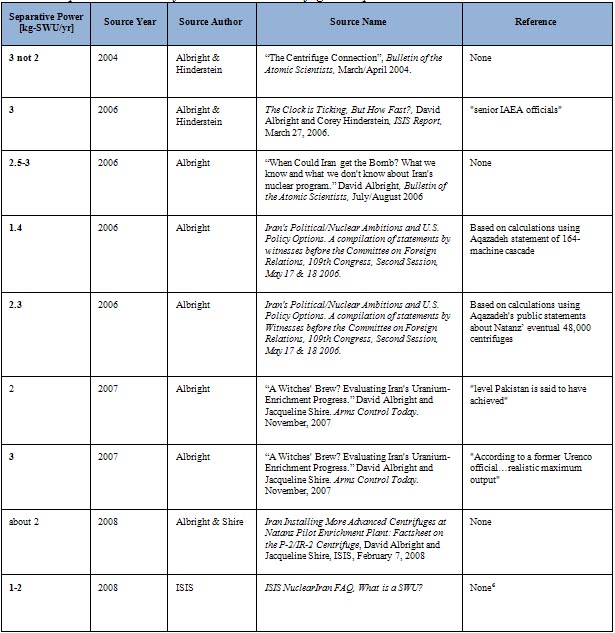

Albright and Brannan state that we “appear to assume” that Fordow would perform worse than Natanz. Quite the contrary, we state clearly in our Issue Brief that “We use well- documented, publicly available data from official IAEA reports and one assertion: The best estimate of the near term capacity of the Fordow facility is the most recent capacity of the Nantanz facility, scaled by size.” In the December 4 ISIS report, this statement is corrected to say we “significantly underestimate the performance of the Natanz facility.” The basis of their argument is that our calculation of the IR-1’s effective separative capacity of about 0.44 kg-SWU/yr, lower by a factor of three, four, or more than previously published estimates (see Table 1 of the Issue Brief), is not characteristic of and seriously underestimates Iran’s capabilities. We argue that previous speculations on the separative capacity of the IR-1 simply cannot explain IAEA data on the actual performance of IR-1 cascades at Natanz, which we consider to be the only credible open-source information available.

Argument #1: Adopting Ad Hoc Values

Expert guesses on the IR-1 separative capacity vary greatly, as illustrated in Table 1 of our Brief. For example, since 2006 Albright continuously sites values in the 2 to 3 kg-SWU/yr range, which are either not referenced or are attributed to untraceable sources (e.g. “senior IAEA officials”, “former Urenco official”). The lowest value that Albright has cited was in a footnote on his prepared statement for the Foreign Relations Committee in 2006, which is 1.4 kg-SWU/yr, based on calculations of a 164-machine cascade described in an Iranian official’s interview (this number is consistent with Garwin’s estimate using the same data). Albright characterizes the 1.4 value as “relatively low output” and this number is never used in breakout scenario estimates. In the same footnote, he calculates a higher capacity of 2.3 kg SWU/yr based on Aqazadeh’s ballpark figures on the performance of the total planned 48,000 centrifuges. Since then, the most recent and most widely referenced value for the separative power of an IR-1 that ISIS uses in breakout assessments is 2 kg-SWU/yr. When given the choice between a higher value attributed to unnamed sources and values he calculates himself, Albright consistently chooses the higher values. This is especially misleading when dealing with weapon production scenarios, which evaluate what Iran can currently achieve.

However, in their critique of our Bulletin article, Albright and Brannan adopt significantly lower values for the separative power: 0.6-0.7 kg SWU/yr (which they say is “undoubtedly too low”) and 1.0-1.5 kg-SWU/yr (which they say is “reasonable for new IR-1 centrifuge cascades”). They do not explain their reasoning for the latter value, except that the upper boundary is close to “Iran’s stated goal.” Perhaps, the authors are referring to Albright’s 2006 estimate based on the Aqazadeh statement, but now pick the lower value of 1.4 kg-SWU/yr that Albright had calculated but dismissed. Although Albright and Brannan do not reveal the data or go through the calculations for their former value, they do allude to their method, which we will discuss below.

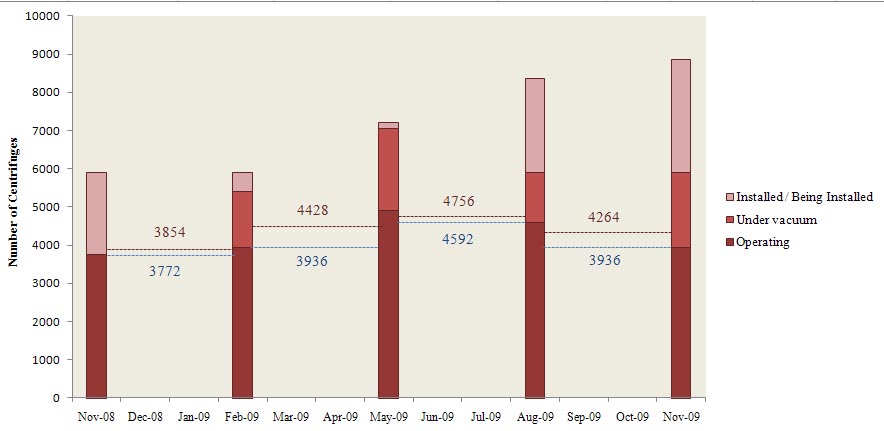

The authors arrive at the 0.6-0.7 kg-SWU/yr based on “the average output over nine months in 2009.” We believe that even this “undoubtedly too low” value has been miscalculated. There are two major sources of difference with the FAS 0.44 kg-SWU/yr value: (1) ISIS uses Iranian logbook data, which does not account for the hold up of material while FAS uses independently calibrated data in the IAEA reports, (2) ISIS does not account for the change in the number of machines in the 9 month period cited (we believe ISIS was referring to 31 January to 30 October 2009). On the other hand, FAS uses the values of independently recorded data (unfortunately, you have to look for them in the footnotes of the IAEA reports) and accounts for the holdup as described in our Issue Brief. In addition, we look at data since the last IAEA physical inventory in 2008, from 18 November 2008 to 30 October 2009 (the entire period for which calibrated data are available).

Iranian logbook data have been shown to slightly underestimate the amount of feed and more significantly overestimate the product. Essentially, Iran is putting more uranium in their machines and less enriched product is coming out than their material accounting algorithm shows, which effectively means that separative power calculated with Iranian logbook data is expected to overestimate the actual effective separative power per machine. This is why indendently calibrated data, if IAEA physical inventory data are not available, provides a more realistic estimate.

Albright and Brannan take an average of enriched product as reported by Iranian logbook estimates from February to October 2009 (an overestimated value), then they simply divide by the number of months to obtain a monthly average, also ignoring the fact that the number of machines varies from month to month. ISIS does not consider the amount of feed that has been reported to enter the cascades under the same set of data, but simply adopt 0.4 percent as the concentration of the waste stream. Although that number is indeed present in a footnote in IAEA reports (GOV/2009/35), it is not the overall concentration of the waste, but shows that particles of depleted uranium “down to 0.4% U-235 enrichment” have been measured. The difference between the ISIS lowest estimate and the FAS estimate is not as significant as the fact that Albright and Brannan dismiss the effective capacity of the IR-1 altogether.

Argument #2: Iran operates fewer machines when the IAEA is not looking

The number of centrifuges in the period is not only a difference between ISIS and FAS’s calculations but is also Albright and Brannan’s basis for dismissal of a smaller number altogether. The “number of centrifuges used in the derivation is from IAEA safeguards reports and exceeds the quantity of those centrifuges that are actually enriching.” In personal communication with Scott Kemp (as posted on Pollack’s blog), Albright has also speculated that cascades are not being operated continuously. This makes little sense. Do the Iranians wait until inspectors arrive to turn on their machines? (If this is so, then our problem with Iranian enrichment can be solved quite easily: just stop inspections and Iran will stop enriching altogether.) Additional reasons given in a recent Albright and Shire analysis published in Arms Control Today include: Iran is keeping cascades in reserve in case of cascade failures or if it decides to “produce higher enriched uranium” or Iranian experts are focusing on getting Fordow running. All of these arguments seem weak. In the November 30 report, ISIS make yet another conjecture –“a significant fraction of these 4,000 machines are likely also not enriching or are broken.” As far as we can tell, the ultimate basis for this claim is that otherwise ISIS’ higher per machine capacity does not make sense. However, we discuss the one bit of numerical evidence Albright and Brannan provide for their speculations below.

Based on IAEA reports, even if we assume the minimum number of machines for each reporting period, instead of taking averages, the SWUs per machine will increase from 0.44 to 0.47, which of course, has a negligible effect on breakout scenarios. For the ISIS argument to become important, we have to believe that half or more of the machines reported by the IAEA to be operational in fact are not.

Moreover, remember that the basis of our argument is that recent performance at Natanz is the best predictor of near-term performance at Fordow. ISIS not only rejects our calculation of Natanz performance but rejects our assertion about it being the best predictor of Fordow. The implication of the ISIS critique is that, while there might be severe problems at Natanz, these will not be repeated at Fordow. This may or may not be true. Perhaps the centrifuges at Natanz perform poorly and are very unreliable and Iran has figured out all those problems and will only install 2.0 kg-SWU machines at Fordow (although we have no hard evidence that IR-1s of that capacity exist). Alternatively, perhaps there are systematic problems with centrifuge production and cascade operation and this is the best the Iranians can do in the near-term. Our assertion hinges on Iranian improvements being incremental and evolutionary and on not seeing dramatic, revolutionary improvements at Fordow. If this is wrong, then our assertion for Fordow is wrong, but our estimates of Natanz’s capacity would still be correct.

The ISIS paper presents an additional argument to show that per machine capacity was increasing: daily average enrichment stayed constant at 2.75 kg of low enriched UF6 from June to October 2009, while the number of centrifuges dropped from 4920 to 3936. (There is the problem that we will set aside for the moment: Either the IAEA data are suspect or they are not, but one should not dismiss them in one case and base arguments on them in another.) We are back to estimating average number of machines per given period. We have three data points: 31 May – 4920 machines operating, 12 August – 4592, and 2 November – 3936. We disagree slightly with ISIS here: From 31 May to 31 July (not 12 August) the average daily enrichment is about 2.77 kg UF6 (according to Iranian logbook data, not calibrated measurements) and similarly, about 2.47 kg UF6 from 31 July to 30 October (not 2 November). Note that material balance and centrifuge counts were taken on different days, thus the difference in day count. So, technically the average daily uranium hexafluoride product decreased as the number of machines decreased.

However, there are several larger problems with this argument. First and foremost, it depends on Iranian logbook data, which has been demonstrated to be inaccurate (plus, of course, IAEA inspection data that ISIS tells us is unreliable). Taking averages for the number of machines operating in each period and a concentration for the product of 3.49% (as the 2008 PIV), we get a slight decrease from 0.51 kg-SWU/yr (18 November 2008 to 31 May 2009) to 0.46 kg-SWU/yr (31 May to 31 July), followed by a jump to 0.59 kg SWU/yr per machine (31 July to 30 October), that is, a sudden more than a quarter increase, according to Iranian logbook data. However, if we look at the independently calibrated measurements, the increase is only from 0.43 (18 November 2008 to 2 August 2009) to 0.49 kg SWU/yr (2 August to 30 October 2009). Also, note a negative holdup for August-November 2009; this could mean that the Iranians have started feeding the leaked material back into the cascades and are salvaging some of the lost separative work. Finally, we do not know the enrichment concentrations definitively for those short periods. For example, a shift in enrichment from 3.49% as we assumed to, for example, just 3.63% in one case and 3.23% in the other would, by itself, account for all of the difference in separative work and set the average separative capacity per machine for the 2 periods to approximately 0.5 kg SWU/yr. Therefore, the ISIS numerical example is not necessarily indicative of an increased per machine capacity.

We believe the lesson here is that short term logbook data are not reliable. Over time, an overestimate during one period will balance an underestimate in another and we will get closer to actual values but on short time scales we need to be wary of Iranian self-reporting. We concede, whenever we are given the choice, we rely on measurements conducted by IAEA on-site inspectors rather than Iranian logbook entries.

Argument #3: Misrepresenting the FAS Calculation

Albright and Brannan have succinctly expressed the basis of their critique: “We were unable to understand the problems in the FAS calculation.” On this point, we agree wholeheartedly.

Here is their argument according to the second paragraph of their 4 December posting: (1) They use our separative work number of 0.44 kg-SWU/yr to calculate what we would predict to be the output of Natanz; (2) This number turns out to be about half of what Natanz is actually producing; (3) QED, our separative work number must be wrong.

But part of their input data is that “[t]he authors also assert that the tails assay at Fordow should be 0.25 percent” when we never say any such thing (we do show example calculations using low, that is to say, global industry standard, tails assay). In fact, we calculate the tails assay at Natanz as 0.46%. Indeed, in the very next paragraph, they say that “FAS appears to have forced a U-235 mass balance by adjusting the tails assay in Table 2 in their assessment to 0.46 percent as a way to get the masses to match. But the situation at Natanz is quite complex.” On this point, we admit we are guilty as charged. When they say we “forced” the tails assay, what they mean is that we used the mass balance equation. And if the laws of conservation of mass do not apply in Natanz, then we concede that the situation there is quite complex indeed. (And, moreover, no calculation that anyone could make would be useful even in theory.)

Albright and Brannan are more specific: “For example, calculating the mass balance on the uranium 235 (uranium 235 in the feed should equal the uranium 235 in the product and tails) is not possible based on the available information. This requires assigning values in a formula that are impossible to substantiate.” Going to equation 5 on p. 8 of the Issue Brief and following the references, the reader can see that all of the values on the right hand side of the equation appear in IAEA reports. (And presumably as an alternative to “assigning values in a formula that are impossible to substantiate,” we would do better to accept values credited to “senior IAEA officials.”) If one uses our actual tails assay rather than the incorrectly asserted tails assay and the proper number of centrifuges and the difference between Iranian logbook data and actual IAEA measurements, all of the differences disappear. (As they have to, since we calculated the 0.44 kg-SWU/yr value in the first place based on these same numbers.)

In the end, an important scientific principle has been demonstrated here: if one takes several variables from one of our examples and several more variables from a separate example and combines them randomly, nonsense results.

Argument #4: ISIS Is Right Because the White House Says So

The most compelling support for the ISIS estimate that “using 3,000 IR-1 centrifuges, and starting with natural uranium, Iran could produce enough weapons-grade uranium for one bomb in roughly one year” that the authors give is that it is similar to the White House September 25 briefing statement that Fordow is capable of producing HEU for one to two bombs a year. First, this is a classic example of argumentum ad verecundiam – we are not about to accept White House numbers without checking their math. Moreover, it must be clarified that the US government’s statement is fairly vague and does not give details on this assumed breakout scenario (whether HEU is enriched from LEU or natural uranium and whether a crude or sophisticated weapon is assumed). What the government said was:

“[..] if you want to use the facility in order to produce a small amount of weapons-grade uranium, enough for a bomb or two a year, it’s the right size. And our information is that the Iranians began this facility with the intent that it be secret, and therefore giving them an option of producing weapons-grade uranium without the international community knowing about it.”

Let’s focus on paragraphs 6 and 7 from the November 30 ISIS report. In paragraph 8, the authors state that the White House scenario is unlikely to assume a breakout scenario using low-enriched uranium, since such a diversion would be likely discovered because LEU would have to be sneaked out of Natanz, which is under IAEA safeguards. They interpret the White House statement that weapons grade uranium would be enriched “without the international community knowing” means that this scenario would necessarily involve enrichment of natural uranium to HEU levels. But it must be noted that such a scenario would require a secret conversion facility as well, since the conversion plant at Esfahan is also under safeguards.

In paragraph 7, Albright and Brannan critique our assessment for “appearing to assume” that breakout scenarios considered depend on “activities not being discovered”, in apparent contradiction to their assumption in paragraph 6, that emphasized the importance of the clandestine function of Fordow. ISIS further argue that if Iran was “breaking out,” Fordow would likely sustain military attack better than Natanz. Our Bulletin argument was this: if Iran’s HEU production was likely to be discovered (such as if a diversion from Natanz were detected), speed is of the essence. They may be better off kicking out inspectors and going full-speed ahead at a facility such as Natanz with a large capacity, rather than proceeding with an option would take a year or more at Fordow. If Fordow’s capacity was significantly increased or if there were other similar facilities, this judgment may change.

Conclusion

As we have shown ISIS’s critiques of our Bulletin analysis and its underlying technical assessment are completely unsubstantiated. First, their track record of using higher vaguely referenced values and dismissing values based on physical data and their own calculations, just because they are inconsistent with their previous assessments, is troubling. Second, they greatly misrepresent FAS’s technical argument, which is clearly described in our Issue Brief. Third, Albright and Brannan seem to pick and chose assumptions to suit their argument at hand: on one hand they assert that IAEA data do not provide a good account of what is going on at Natanz to advance one point, but at the same time cite these data to support other points.

Overall, it is hard to see the bigger argument that ISIS is making by attacking our premise regarding Natanz’s capacity (and consequently Fordow’s), but not specifically address our conclusions on Iranian intentions vis-à-vis Fordow. It seems Albright and Brannan are interested only in defending their use of a higher separative capacity by attempting to undermine our argument. They do not discuss how our Bulletin conclusions would change if their shorter time estimates were correct, but simply dismiss our analysis altogether.

Ultimately, the reason we engage in discussions over these numbers is because we believe that overestimating Iran’s enrichment potential will provide us with a skewed perception of Tehran’s intent and strategic planning. It is indeed important to be able to make a realistic assessment of Iran’s current capacity and future potential. However, this is best done using neither Poisson statistics nor arguments of authority, but a good look at readily available hard data.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.