Vaccine news stories hosting malware disseminated across Spanish-language Twitter

Key Highlights

- News websites publishing stories on a pause in the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine trials hosted malware files. At the center of the network was the Spanish-language Sputnik News link mundo.sputniknews.com.

- The news of a possible adverse reaction to the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine resulted in a spike of social media activity. The vaccine is one of the most high profile in development, making any significant news story about it a hot topic on social media. Because it was all but guaranteed that discussion about the vaccine online would explode, hiding malware in articles about the day’s hottest topic brings significant vulnerability to unwitting readers.

- Analysis detected malware associated with popular news sites covering Oxford-AstraZeneca related stories. This discovery was made by scanning 15,820 URLs covering the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. The scans returned 53 sites hosting malware within the AstraZeneca conversation. The placement of malware in these sites may provide opportunities for perpetrators to manipulate additional web traffic to unwitting users in order to inorganically amplify stories that could cast doubt on the efficacy of particular vaccines.

- Notably, Russian state-sponsored media, Sputnik News, was identified as a large component of this network.

Malware hosted within popular news stories about COVID-19 vaccine trials

On September 8, 2020 Oxford University and AstraZeneca placed their COVID-19 vaccine (AZD1222) development on hold. During Phase 3 trials, a woman in the United Kingdom experienced an adverse neurological condition consistent with a rare spinal inflammatory disorder known as transverse myelitis. As is typical with large-scale vaccine trials, the woman’s condition triggered a pause in the trial, lasting until September 12, at which time the trial was officially resumed. Analysis was conducted on the Twitter conversation surrounding the AstraZeneca adverse reaction event and detected social media posts spreading malware and malicious software via links embedded within those posts. One possible goal of the perpetrators is to identify the audience that is most interested in the issue of vaccines in order to micro-target the group with future items of interest, possibly to artificially tilt the conversation for or against certain vaccines.

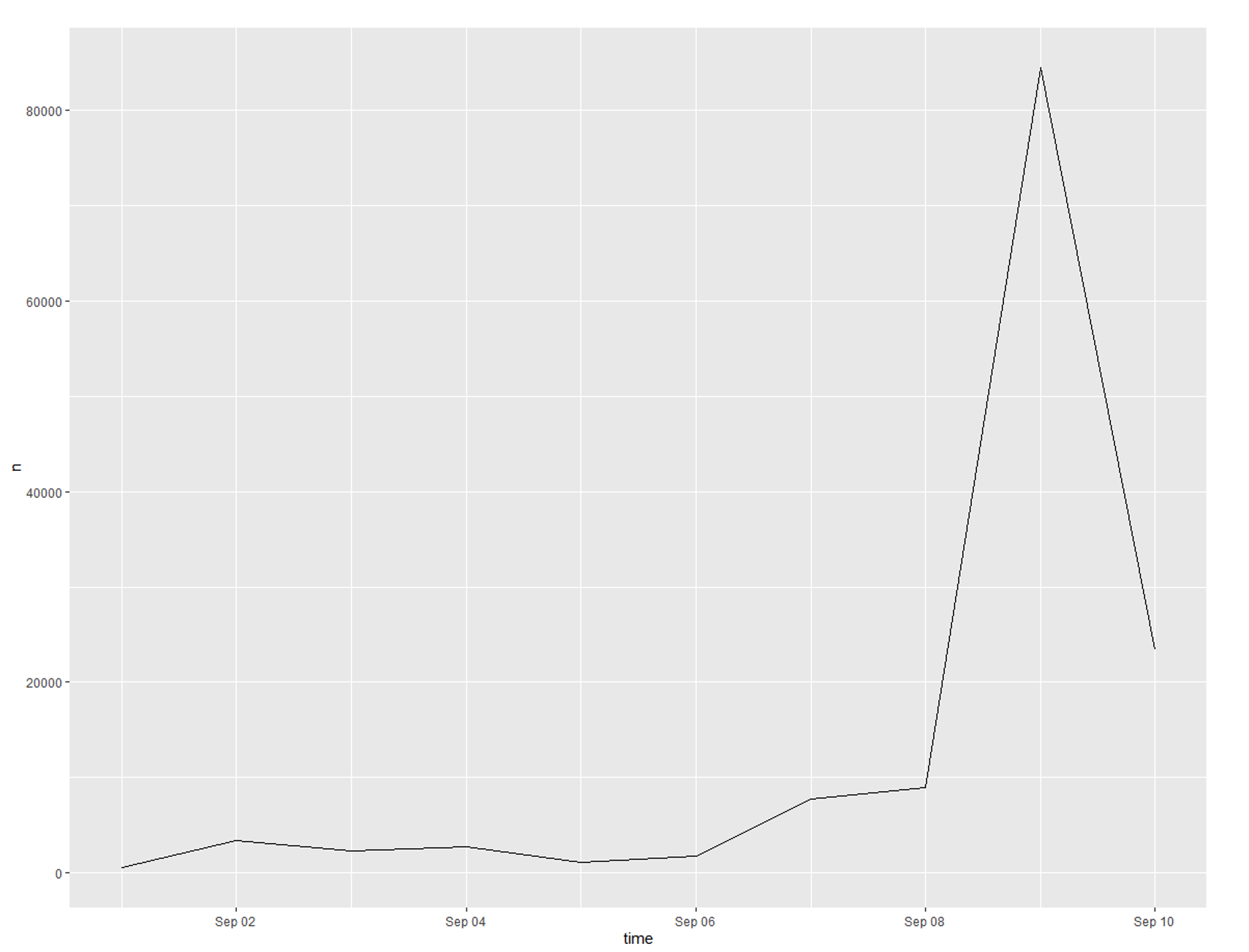

Seen in Figure 1, our analysis includes 136,597 tweets from September 2nd – 12th. Tweets were collected from the Twitter developer’s API using keyword searches for “AstraZeneca”, “AZN”, “AZD1222” and the stock symbol “$AZN”. Beginning on the 8th, coinciding with the adverse event report, there is a large increase in the volume of tweets, with over 80,000 tweets identified on September 9th.

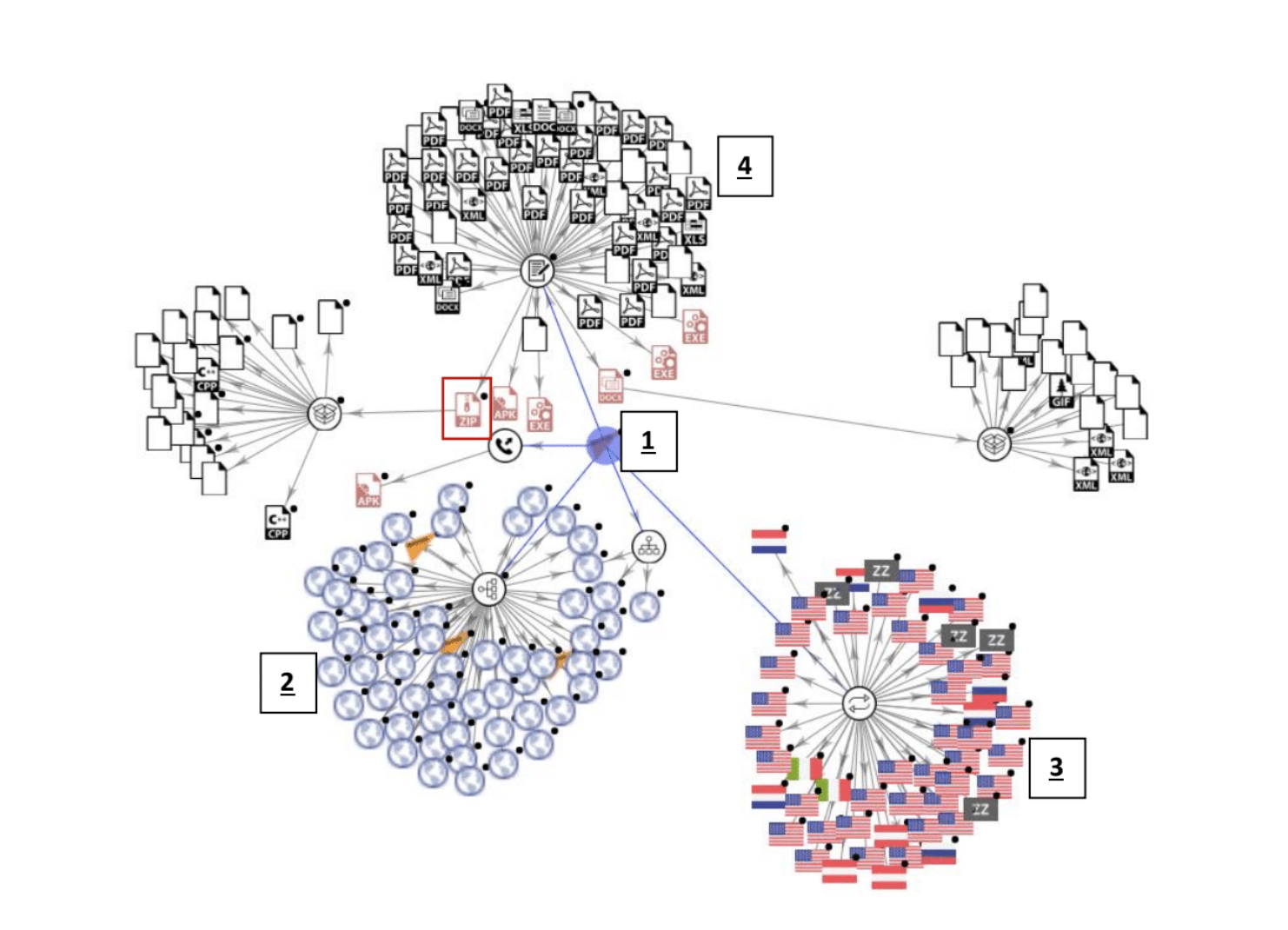

Within all collected tweets, 15,820 unique URLs were discovered (approximately 11.5% of tweets contained a URL). Most Twitter users utilize URLs within their tweets with the intent to flag or to redirect their audience to a related news story as shown in Figure 2. This particular URL for the popular news site, Stat News was shared in 1,265 tweets.

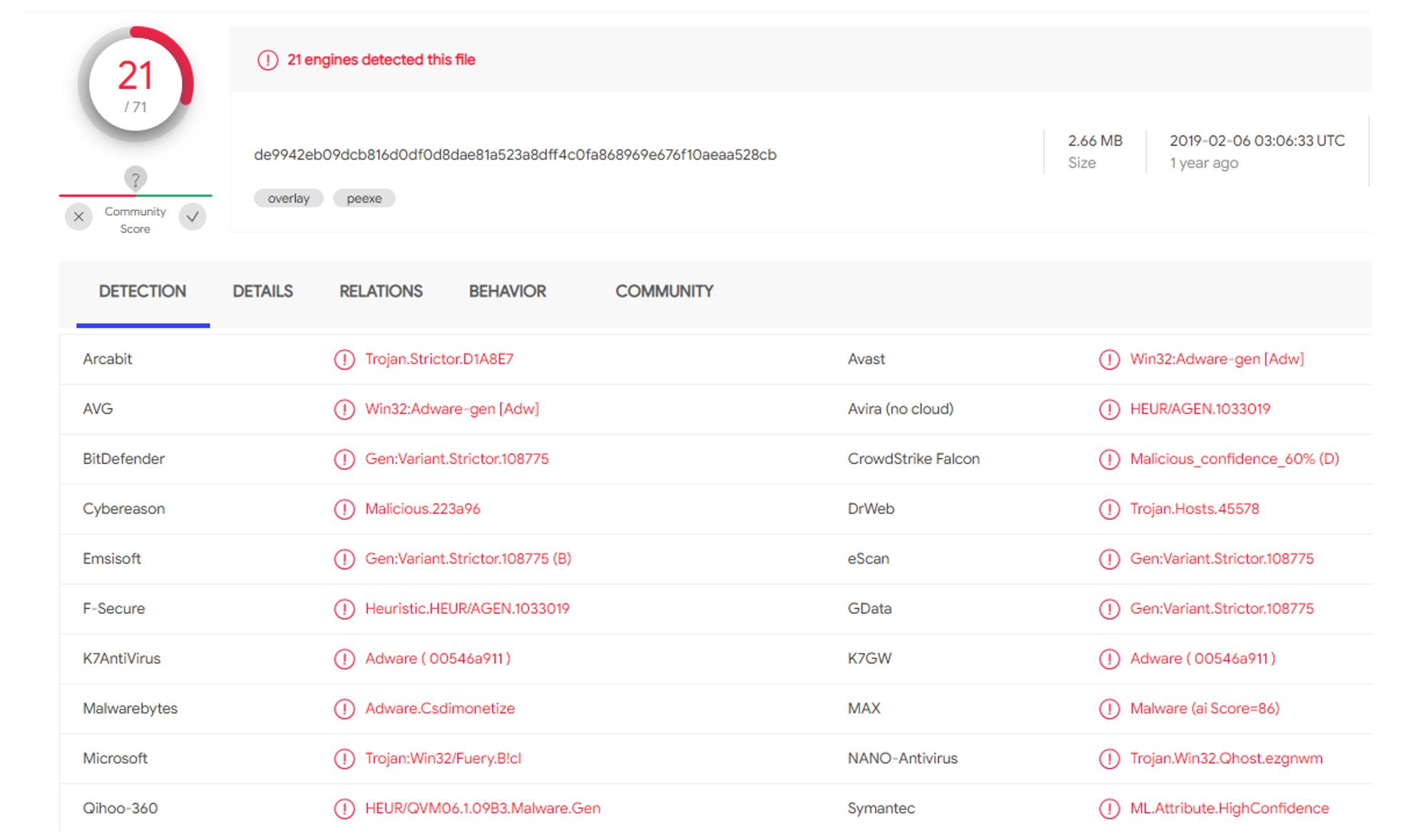

These tweets can also serve as vectors for the spread of malware. Malware can be loaded onto a webpage whose URL is shared with others. This is a technique that is of increasing concern in the spread of disinformation and propaganda. Through the open source malware detection platform VirusTotal (www.virustotal.com), we detected 53 sites hosting malware within the AstraZeneca conversation. Four URLs in particular were returned as malicious from the domain of Russian state sponsored Spanish-language Sputnik News (mundo.sputniknews.com). We deciphered that these set of domains were hosting seven distinct malware packages. Seen below in figure 3, these include executable files, android phone-specific malware, Microsoft Office XML, and a zipped folder rated as malicious. Notably, Russia’s Sputnik news site rests at the center of the malicious network.

With mundo.sputnik news at the center of this network (1), series of website links (2), connected IP addresses by nation (3), and the group of both malicious and non-malicious files (4). Examination of the details for the zipped folder of malware highlighted revealed 21 unique detections within that single file. As seen on figure 4, we detected a series of malware files.

The malware is designed to access nearly all intel-based hardware running on MS Windows. It accesses core system components including kernel32.dll, shell32.dll, and netmsg.dll files on a host machine, and accesses multiple critical registry files, and creates multiple mutex files during this process.

Mutexes are best understood in an example: web browsers maintain a history log of sites visited. With multiple browser windows open, each browser process will try to update the history file, but only one can lock and update the file at a time. By registering the file with a mutex object, the different processes know when to wait to access the file until other processes have finished updating it.

The analysis indicates the AstraZeneca conversation on Spanish-language SputnikNews is being used to spread malware specifically designed to monitor unwitting user behavior on their personal devices. This is particularly significant considering the outreach by Russian vaccine efforts to Latin American audiences and governments.

With COVID-19 vaccine efforts being among the hottest news topics on any given day, a halt to the vaccine process was all but guaranteed to create a huge spike in social media mentions. The spike in daily tweet numbers seen in figure 1 shows how popular that topic is, but also how vulnerable the conversation is.

With multiple outlets reporting on any given news story, it is often difficult to parse what sites are safe and which are potential dangers. For less savvy internet users, this consideration might not even come into play, which leaves them vulnerable to malware and virus attacks for little more than just clicking on the wrong news story.

While we do not know how many people were infected by the malware we found, we can say that the wrong person clicking the wrong link could have disastrous effects. One feature in particular could capture sensitive information on a user’s screen, like addresses, to credit card numbers, identification, or even confidential information in sectors like banking, or government. While we were able to catch the malware in advance, those without the same robust security would be at a much steeper risk.

This malware technique can also be used to identify users who are interested in vaccine stories in order to target them with future vaccine news. Micro-targeting allows for companies to define specific, rigid user profiles in order to create an audience for content and ads. If users are placed within one of these audiences, companies placing ads are able to send them content tailored for their interests. For instance, if someone is flagged as being interested in vaccine news, they might be a targeted recipient of an ad buy meant to highlight misleading, false, or sponsored news about the development of another vaccine. Since ads often appear organically in social media feeds, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between an article your friend shared and an article a company paid to place in front of you.

Methodology

We performed a combination of social network analysis, anomalous behavior discovery and malware detection. We scanned 15,820 topic specific URLs run through an open source malware detection platform VirusTotal (www.virustotal.com). The scans returned 53 sites hosting malware within the AstraZeneca conversation.

For more about the FAS Disinformation Research Group and to see previous reports, visit the project page here.

The Federation of American Scientists applauds the United States for declassifying the number of nuclear warheads in its military stockpile and the number of retired and dismantled warheads.

North Korea may have produced enough fissile material to build up to 90 nuclear warheads.

Secretary Austin’s likely certification of the Sentinel program should be open to public interrogation, and Congress must thoroughly examine whether every requirement is met before allowing the program to continue.

Researchers have many questions about the modernization of Pakistan’s nuclear-capable aircraft and associated air-launched cruise missiles.