China’s Expanding Missile Training Area: More Silos, Tunnels, and Support Facilities

The Chinese military appears to be significantly expanding the number of ballistic missiles silos under construction in a new sprawling training area in the northern part of central China.

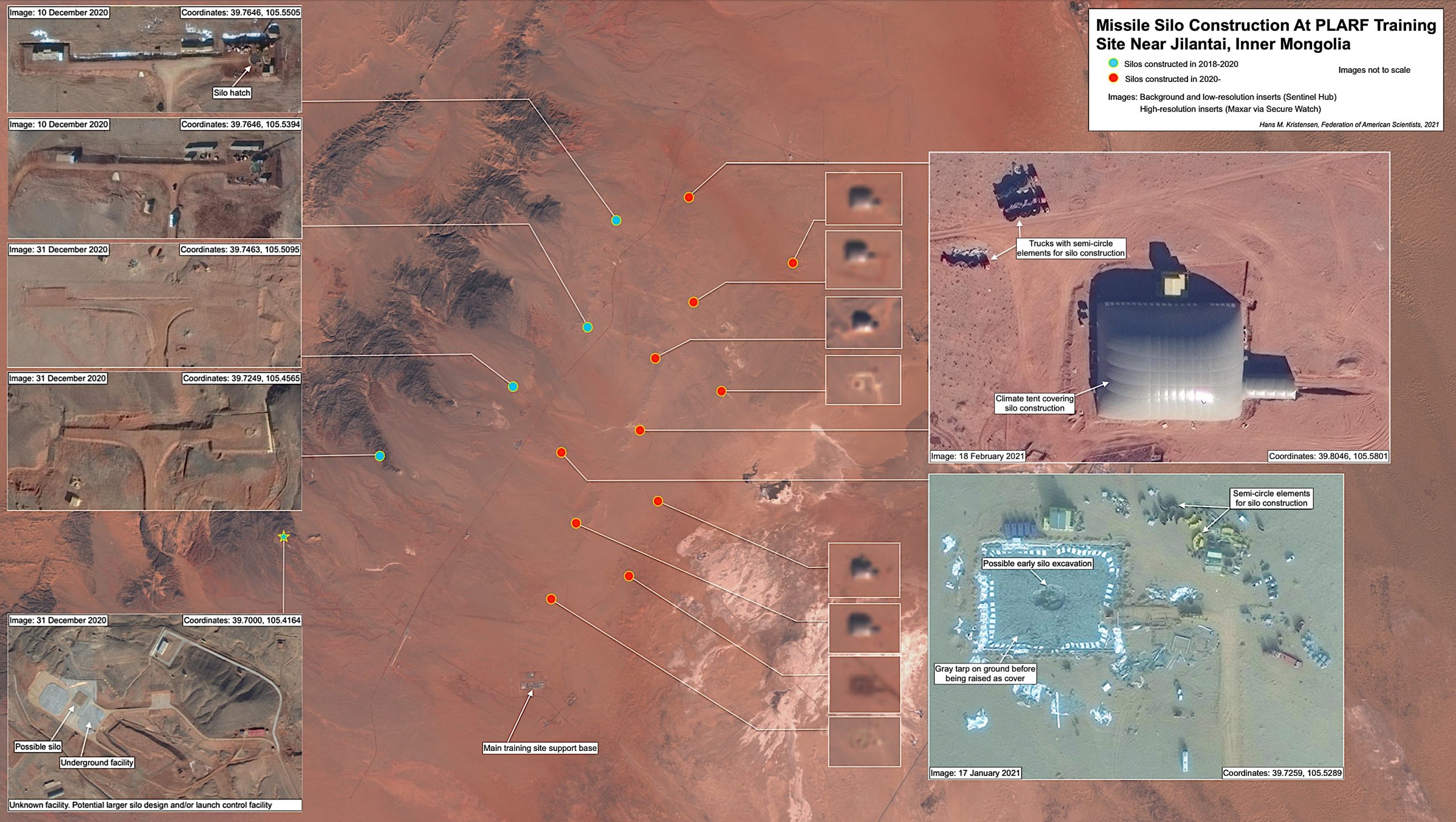

Recent satellite images indicate that at least 16 silos are under construction, a significant expansion in just a few years since a silo was first described in the area.

The satellite images also reveal unique tunnels potentially constructed to conceal missile launch units or loading operations.

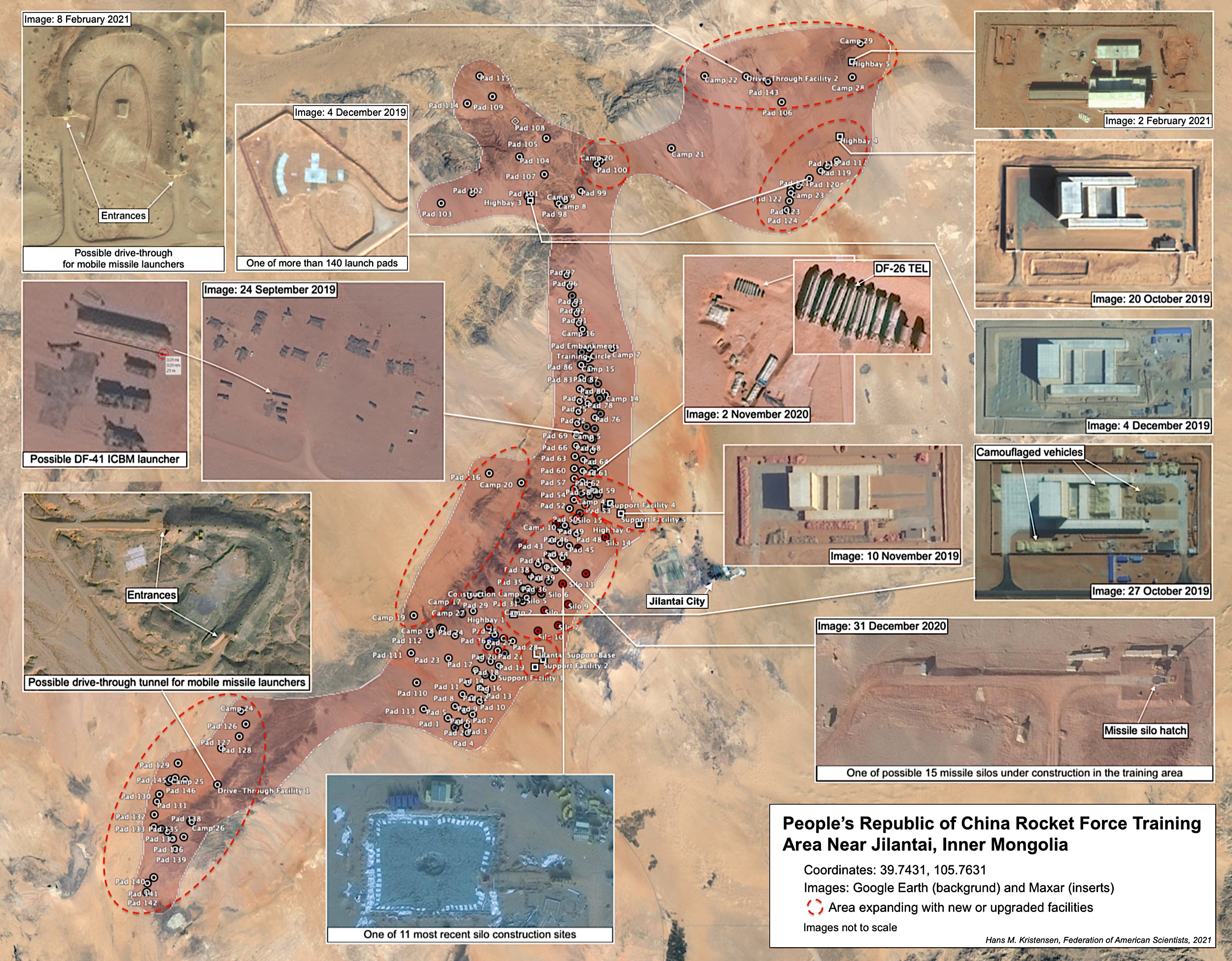

The training area, located east of the city of Jilantai in the Inner Mongolia province, is used by the People’s Republic of China Rocket Force (PLARF) to train missile crews and fine-tune procedures for operating road-mobile missile launchers and their support vehicles.

The Jilantai PLARF Training Area

The Jilantai training area stretches for 140 kilometers (87 miles) over an area of nearly 2,090 square-kilometers (800 square miles) of desert and mountain ranges. It is a relatively new training area with most facilities added after 2013 and has since expanded to well over 140 missiles launch pads used by launch units to practice launch and loading procedures, more than two dozen campgrounds where launch units stay for a short period before moving on, five high-bay garages servicing launchers and support vehicles operating in the area, and a large supply base with adjacent support facilities (see image).

Click on image to view full size. To download an updated Google Earth placemark file with all facilities in the Jilantai training area, click here.

The training area is very active and is currently expanding in several regions, especially to the north and south as well as in the center. The expansion includes new high-bay facilities that handle launchers and missiles, a vast number of pads used by launchers and their support vehicles, missile silos, camping areas used by launch units, and underground facilities to hide and protect launchers.

Mapping the area took quite a lot of work spread out over the past two years. Unfortunately, Google Earth only has very limited and outdated image coverage of the area. Only the north-eastern sector has fairly recent images (2019). The vast majority of the imagery is still from 2013 and 2014. This is a surprise, given how much interest there is in this area. Instead, thanks to funding support from my funders listed at the bottom of this article, I used a subscription to Maxar’s Secure Watch service to get access to updated high-resolution imagery. The service is too expensive to use to search large areas and Planet Labs has a hefty price to even get access to low-resolution imagery. Fortunately, the European Sentinel Hub Playground offers free low-resolution imagery that served as a useful tool to detect new structures (the imagery is updated every five days) that could then be examined more closely with Maxar images.

Monitoring this area provides a wealth of information about how PLARF operates its mobile missiles units, the vehicles that are involved in the operations, and what structures and features to look for in the actual base deployment areas throughout China. It also provides important clues about China’s current and future nuclear modernization and helps assessing claims made by US defense officials about China’s capabilities.

Silo Construction

One of the most important new developments in the Jilantai training area is the construction of a significant number of facilities that appear to be silos intended for ballistic missiles. In the future we might see missile test launches from these silos.

Nearly all of the silos appear to be smaller than the type used for the large DF-5 ICBM in the base areas. The Department of Defense says that Jilantai “is probably being used to at least develop a concept of operations for silo basing” the DF-41.

At least 16 silos appear to be under construction (see image below). They vary in dimensions and construction has so far happened in three phases: the first silo facility started construction in 2016, four “Russia-type” silos followed in 2018-2020, and construction of an additional 11 silos began in late-2020. All of the silos are located in the center of the training area within a 10×20-kilometer (12×7-mile) area. The silos are spaced 2.2-4.4 kilometers (1.4-2.7 miles) apart, enough to ensure, presumably, that no two of them can be destroyed in a single one nuclear attack.

The first silo began construction in 2016 with what appears to include a silo and several underground facilities (39.7000, 105.4164). The outline and features are similar, but not the same, as the new silo constructed at the Wuzhai Test Launch Complex (38.888, 111.5975). It has not been confirmed that the Jilantai facility is a silo and construction was covered by a large building for several years. But equipment visible on satellite photos in 2019 appear to show semi-circle structures potentially used to build the silo walls. If so, it might be intended for a DF-5 size missile.

The second phase of silo construction began in June 2018 and now seems nearly complete. This includes four silos along the western side of the central training area. During construction, the silos were covered by a building similar to the first silo. These four silos look very similar to Russian silos with little surface infrastructure, a turn-road for trucks bringing in a missile, a 30-meter missile loading pad, and a silo lid with a diameter of about 6 meters (20 feet).

This second phase began shortly before the Pentagon’s annual report on Chinese military developments in 2018 reported that “China appears to be considering additional DF-41 launch options, including rail-mobile and silo basing.”

It was this second phase I described in an article in September 2019, a discovery that was later credited in the Defense Department’s 2020 report to Congress on Chinese military and security developments. According to the report, the size of these silos “precludes use by the DF-5 and may support concept development for a silo-based DF-41 or one of China’s smaller ICBMs,” such as the DF-31A.

The third and so far biggest silo construction phase began in late-2020 and has expanded quickly to a total of 11 silos during the first two months of 2021. Construction is still early but satellite images indicate the silos are similar in size to the four constructed in the second phase. However, the construction sites look different. Whereas the previous silos were covered by solid buildings, construction of the new silos appears to involve a climate tent or possibly an inflated bubble structure.

The silo construction at Jilantai coincides with possible construction of silos near Sundian in the Henan province.

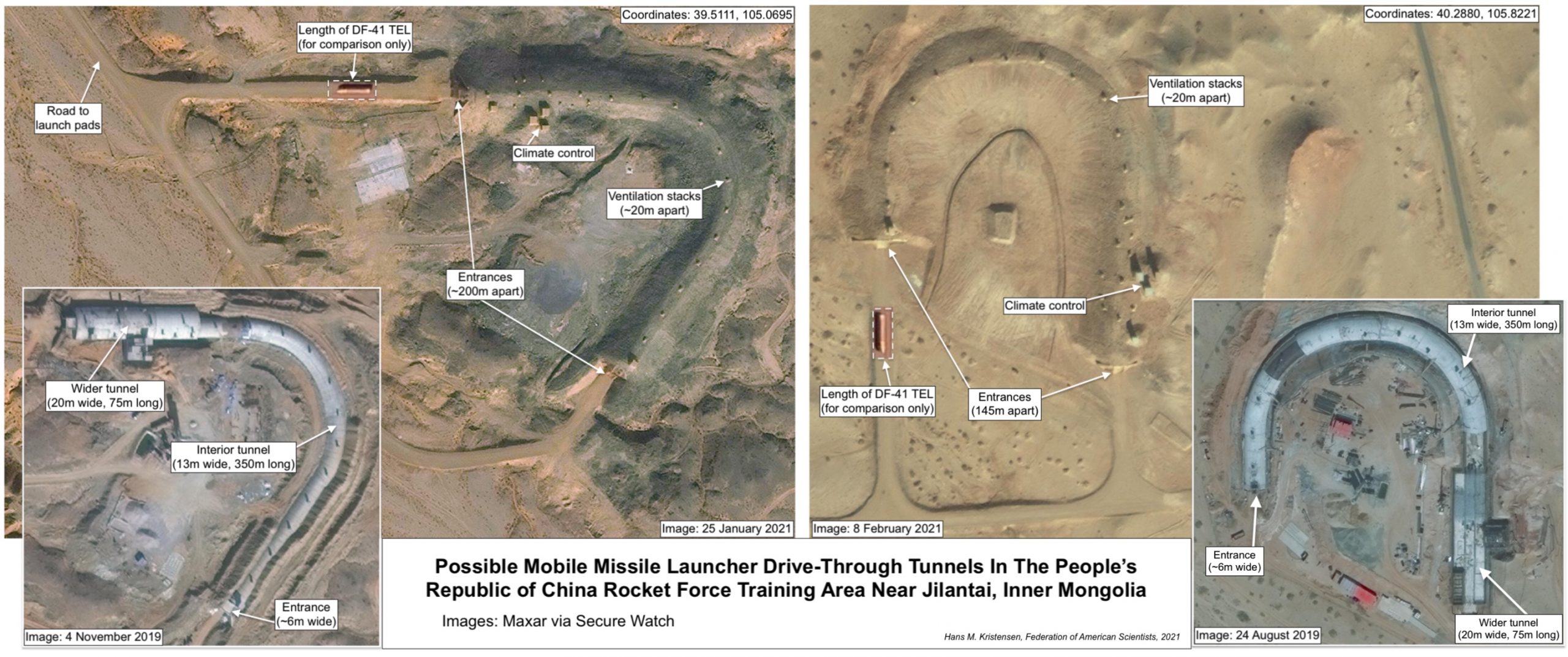

Drive-Through Tunnels

Some of the most interesting new facilities found in the training area include two drive-through tunnels that might be intended for use by mobile launchers. The precise function is unknown, but the physical dimensions and locations suggest the tunnels may serve as field hideouts for launchers or missile reload facilities. Mobile launchers are highly vulnerable when operating in the open.

The two tunnels discovered so far are located at each end of the training area that are under expansion with new facilities and additional launch pads (see image below).

The tunnels are approximately 350 meters (1,148 feet) long and could hypothetically hold a dozen DF-41 launchers. More likely it would hold a smaller number plus their support vehicles. The entrances are about six meters wide and tall, more than sufficient for a large launcher.

Each tunnel has two entrances, and one end has a 75-meter section that is wider than the rest of the tunnel (20 meters vs. 13 meters). The wide section could potentially serve as a missile reload area or personnel quarters. Adjacent to the wide section is a square building with three taller structures that might be for surface access or house a climate control system.

These types of tunnels might also potentially be under construction in the operational brigade base area, although I haven’t fund any yet.

Summary and Implications

The PLARF training near Jilantai provides a unique window into China’s nuclear posture. China currently operates 18-20 silos, a number that could nearly double with the construction of the silos in the Jilantai training area. Whereas as the existing silos are large to accommodate the old liquid-fueled DF-5 ICBM, all but one of the new silos at Jilantai are smaller and appear designed to accommodate the newer and slimmer solid-fuel ICBMs, such as the DF-41 (and potentially DF-31A).

The construction of so many silos (16 have been found so far) in a training area is curious (there are only two training silos at the Wuzhai Test Launch Complex). One would imagine that a couple of silos would provide sufficient training. One potential explanation might be that China is experimenting with several different types of silos designs to determine which type(s) eventually will be constructed in the various brigade base areas. The Pentagon asserted in 2020 that Jilantai “is probably being used to at least develop a concept of operations for silo basing” the DF-41. To that end, the silos could potentially even achieve some actual operational capability.

It should be pointed out that even if China doubles or triples the number of ICBM silos, it would only constitute a fraction of the number of ICBM silos operated by the United States and Russia. The US Air Force has 450 silos, of which 400 are loaded. Russia has about 130 operational silos. In comparison, the 16 new silos under construction at Jilantai correspond to less than one-third of a single squadrons in a single US ICBM wing.

Yet for China, given its nuclear policy of “minimum deterrence,” the construction of a relatively large number of silos at Jilantai is important. Once the operational concept is developed, one could potentially see construction of a couple of new silo clusters at a couple of brigade bases elsewhere in China. Since the construction so far is not about achieving parity with the United States (or even near-parity), why is China doing this and what is driving the development? There are several potential explanations (or possibly a combination of them; listed in no particular order):

Increased protection of retaliatory capability: China is concerned that its current ICBM silos are too vulnerable to US (or Russian) attack. By increasing the number of silos, more ICBMs could potentially survive a preemptive strike and be able to launch their missiles in retaliation. China’s development of its current road-mobile solid-fuel ICBM force was, according to the US Central Intelligence Agency, fueled by the US Navy’s deployment of Trident II D5 missiles in the Pacific. This action-reaction dynamic is most likely a factor in China’s current modernization.

Overcoming potential effects of US missile defenses: Concerns that missile defenses might undermine China’s retaliatory capability have always been prominent. China has already decided to equip its DF-5B ICBM with multiple warheads (MIRV); each missile can carry up to five. The new DF-41 ICBM is also capable of MIRV and the future JL-3 SLBM will also be capable of carrying multiple warheads. By increasing the number of silos-based solid-fuel missiles and the number of warheads they carry, China would seek to ensure that they can continue to penetrate missile defense systems.

Transition to solid-fuel silo missiles: China’s old liquid-fuel DF-5 ICBMs take too long to fuel before they can launch, making them more vulnerable to attack. Handling liquid fuel is also cumbersome and dangerous. By transitioning to solid-fuel missile silos, survivability, operational procedures, and safety of the ICBM force would be improved.

Transitioning to a peacetime missile alert posture: China’s missiles are thought to be deployed without nuclear warheads installed under normal circumstances. US and Russian ICBMs are deployed fully ready and capable of launching on short notice. Because military competition with the United States is increasing, China can no longer be certain it would have time to arm the missiles that will need to be on alert to improve the credibility of China deterrent. The Pentagon in 2020 asserted that the silos at Jilantai “provide further evidence China is moving to a LOW posture.”

Balancing the ICBM force: Eighty percent of China’s ICBMs are mobile and increasing in numbers. Since China is increasing its overall ICBM force, the silo-based portion also has to be increased to serve a credible role.

Increasing China’s nuclear strike capability: China’s “minimum deterrence” posture has historically kept nuclear launchers at a relatively low level. But the Chinese leadership might have decided that it needs more missiles with more warheads to hold more adversarial facilities at risk. The United States, India, and Russia are all modernizing their nuclear arsenal and improving or increasing their weapons.

Improving quick-strike conventional capability: Although the silos at Jilantai are thought to be intended for nuclear missiles, one option could potentially also be (I am not suggesting it is) to begin to deploy conventional ballistic missiles in silos. Doing so would provide a very quick strike capability, not at strategic range but for targets at medium- or intermediate-range.

National prestige: China is getting richer and more powerful. Big powers have more missiles, so China needs to have more missiles too to underpin its status as a great power.

The construction of more than a dozen silos for modern solid-fuel missiles at Jilantai indicates that China may be seeking to increase reliance on silo-based missiles in its nuclear posture. Whether that is the result of the overall increase of its arsenal, a sense of increased vulnerability, or a different thinking about the role that quick-strike ICBMs will serve in the future remains to be seen. But it is a clear reminder about the dynamic of deterrence that continues to fuel nuclear modernization, and the Jilantai training area provides a unique window into China’s efforts.

Background information:

• Chinese nuclear forces, 2020

• China’s New DF-26 Missile Shows Up At Base In Eastern China

• New Missile Silo And DF-41 Launchers Seen In Chinese Nuclear Missile Training Area

• Chinese DF-26 Missile Launchers Deploy To New Missile Training Area

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.