NATO Strategic Concept: One Step Forward and a Half Step Back

|

| NATO General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen presents the alliance’s new Strategic Concept |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new Strategic Concept adopted today by NATO represents one step forward and a half step backward for the alliance’s nuclear weapons policy.

The forward-leaning part of the nuclear policy pledges to actively try to create the conditions for further reducing the number of and reliance on nuclear weapons, recommits to the ultimate goal of nuclear disarmament, and reaffirms that circumstances in which the alliance could contemplate using its nuclear weapons are “extremely remote.”

But the strategy fails to present any steps that reduce the number of or reliance on nuclear weapons. As such, the new Strategic Concept – Active Engagement, Modern Defence – falls short of the Obama administration’s recent Nuclear Posture Review.

Even so, there are important changes in the document that hint of things to come.

The Role of Nuclear Weapons

The new Strategic Concept does not explicitly reduce the role of NATO’s nuclear weapons. Instead, it echoes the Obama administration’s formulation that “as long as nuclear weapons exist,” NATO will remain a nuclear alliance.

And the formulation in the 1999 Strategic Concept that “NATO’s nuclear forces no longer target any country” is gone from the new document. Instead, it states that NATO “does not consider any country to be its adversary.”

Overall, the 2010 document is far less explicit than the 1999 document about what the role of nuclear weapons is. The previous document explicitly described the role “to preserve peace and prevent coercion and war of any kind…by ensuring uncertainty in the mind of any aggressor about the nature of the Allies’ response to military aggression,” and “demonstrate that aggression of any kind is not a rational option.”

The new document, in contrast, describes the role of nuclear weapons in very general terms, essentially with no specifics, and as part of an overall mix of nuclear and conventional capabilities.

Gone is the previous language about U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe providing an essential political and military link between Europe and North America, or that sub-strategic forces provide a link with strategic forces.

Instead, the document states that it is the strategic forces of the United States, in particular, and to some extent Britain and France, that provide the “supreme guarantee of the security of the Alliance”.

US Nuclear Forces in Europe

Combined, these significant changes could be seen as hints of an attempt to lessen the importance the alliance attributes to having U.S. tactical nuclear weapons forward deployed in Europe.

To be sure, the document still contains what appears to be a commitment to some form of U.S. nuclear presence in Europe, by committing to “the broadest possible participation of Allies in collective defence planning on nuclear roles, in peacetime basing of nuclear forces, and in command, control and consultation arrangements.” (Emphasis added)

|

But this is vague language compared with the 1999 document. It could simply be met by Allies taking part in Nuclear Planning Group meetings, deployment of some U.S. dual-capable aircraft in Europe but without weapons, and Allies continuing to be part of the decision making process for potential use of nuclear weapons.

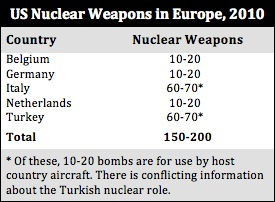

The number of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe today is down to 150-200 B61 bombs deployed at six bases in five countries (see table).

The Role of Russia

In the years between the 1999 and 2010, NATO unilaterally reduced the number of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Europe by more than half, from 480 to 150-200 B61 bombs. The 1999 Strategic Concept did not mention Russia at all as a factor for sizing the U.S. deployment.

The new Strategic Concept, in contrast, returns Russia to a central position for how the Alliance sizes the number of U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

“In any future reductions,” NATO declares, “our aim should be to seek Russian agreements to increase transparency on its nuclear weapons in Europe and relocate these weapons away from the territory of NATO members.”

Moreover, “Any further steps must take into account the disparity with the greater Russian stockpiles of short-range nuclear weapons.”

While seeking to achieve reductions in Russian tactical nuclear weapons is important – it has more than 5,000 of them, formally linking the U.S. deployment in Europe to Russia seems to contradict the policy of the past two decades that the U.S. weapons in Europe are not directed against Russia. And NATO has repeatedly made unilateral reductions without demanding Russian reductions. Indeed, the new Strategic Concept declares that “NATO poses no threat to Russia,” and that the Alliance “does not consider any country to be its adversary.”

So to begin now to argue that the size of the U.S. arsenal in Europe is linked to Russia after all resembles the Cold War policy when NATO looked to Russia for sizing the U.S. arsenal in Europe.

Moreover, Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons posture is less tied to the U.S. nuclear posture in Europe and more to Russia’s perception of countering NATO’s superior conventional forces and defending the long border with China. Since those factors determine the size of the large Russian tactical nuclear weapons arsenal, it is hard to see why Moscow would agree to reduce its tactical nuclear weapons in return for reductions of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.

The Future

The changes in the new Strategic Concept are many and important. The language could hint that NATO may be preparing the ground for the withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe. But the way forward is muddled with preconditions on Russian reductions.

A joint communiqué from the Lisbon Summit might make things clearer tomorrow but it will require a new deterrence review in 2011 for NATO to translate what the Strategic Concept means for NATO’s nuclear posture.

Conditioning future reductions on Russia could be a roadblock, so hopefully the vague “aim to seek” and “taking into account” formulations don’t imply tit-for-tat reciprocity. The success of the unilateral withdrawals in the early 1990s suggests that a unilateral withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe would be more effective in stimulating a Russian response.

The Obama administration sees the emergence of a “new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture” that “make[s] possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” The new Strategic Concept seems to agree, so hopefully the Obama administration can now become more assertive in pushing for a withdrawal of the last U.S. tactical nuclear weapons from Europe so it can focus on an agreement to reduce U.S. and Russian tactical nuclear weapons in general.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The U.S. should continue its voluntary moratorium on explosive nuclear weapons tests and implement further checks on the president’s ability to call for a resumption of nuclear testing.

This missile launch provides an opportunity to further examine China’s nuclear posture and activities, including the type of missile, how it fits into China’s nuclear modernization, and where it was launched from.

Known as Steadfast Noon, the two-week long exercise involves more than 60 aircraft from 13 countries and more than 2,000 personnel.

Increasing women in leadership roles is important for gender parity and bringing in new perspectives, but it does not guarantee peace.