Barriers to Building: A Framework for the Next Era of Electricity Policy

The American power grid in 2025 faces a set of challenges unlike any in recent memory. The United States is deploying clean energy far too slowly to meet load growth, avoid spikes in electricity prices, and combat climate change. To get within striking distance of the Paris climate goals and plan for the lowest electricity costs, we must build 70 to 125 gigawatts of clean energy per year, much higher than the record 50 gigawatts built in 2024.

Grid upgrades, too, are proceeding far too slowly. To meet growing electricity demand and integrate new clean power at lowest cost, transmission capacity must more than double within regions and increase more than four-fold between regions by 2035. But large transmission projects frequently take 7 to 15 years from initial planning to in-service operation and only 322 miles of new high-voltage transmission lines were completed in 2024—the third slowest year of new construction in the last 15 years.

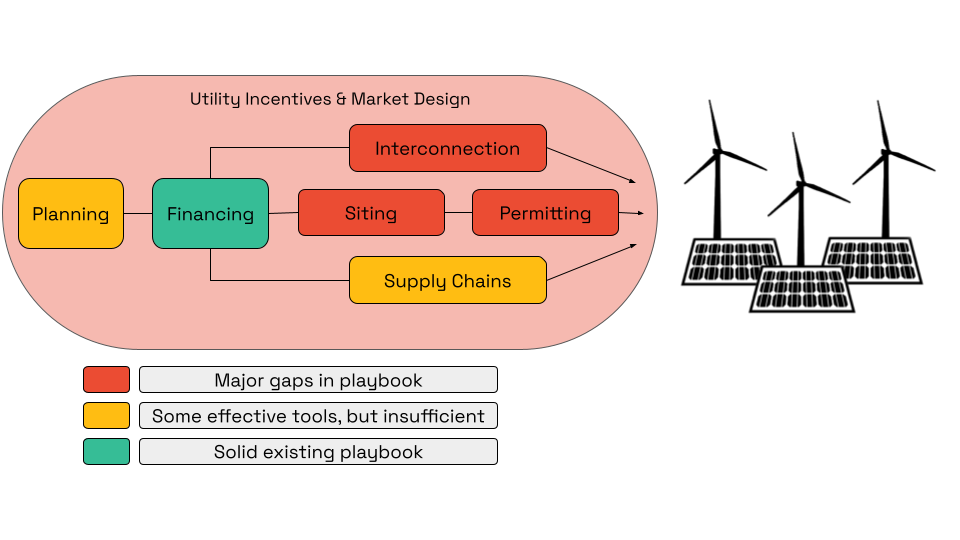

Even before the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) gutted federal clean energy incentives, non-cost challenges like uncertain and lengthy interconnection and siting processes, local restrictions on development, and supply chain bottlenecks led to lower levels of clean energy deployment than projected and slowed down grid upgrades. Now, clean energy and transmission face additional cost and financing barriers from Congressional rollbacks and permitting restrictions from the Trump Administration.

Past federal and state clean energy policies, including the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) as well as state renewable portfolio standards, have leaned heavily on financial incentives to drive deployment and incentivize grid upgrades and expansion. These incentives successfully attracted massive investment in clean energy projects, but they largely did not grapple with non-cost challenges—like siting restrictions—to building projects.

Political challenges have made it difficult to pass, implement, and defend clean energy policies. A mismatch between public needs, government programs, and industry incentives has led to unsatisfactory outcomes and degraded public trust in the government.

Now, policymakers, industry, and the advocacy community are paying more attention to non-financial issues that can impede deployment, like siting and permitting. The abundance movement, for example, has identified two causes of America’s building problem: ineffective government programs and burdensome permitting processes. This diagnosis is incomplete. Getting to a world where we can build things quickly and make government work will require us to identify the full suite of problems, not just these convenient two.

To maximize clean energy deployment, we must address the project development barriers that slow down investment and construction. And to build more durable and effective energy policies, we must interrogate and address the political barriers that have held us back from smart policymaking and implementation that can withstand political change. Overcoming these challenges is necessary to address the climate crisis, rein in rising utility bills, and ensure that government can deliver on its energy promises to the public it serves.

In early 2025, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) set out to identify and categorize these barriers through research and interviews with experts and practitioners. Following this research, at the 2025 Climate Week NYC, FAS convened a group of researchers, advocates, industry leaders, and policymakers to solicit feedback on this framework.

The outcome of that convening allowed us to ground-truth the following report—which we intend to use as a rubric for state-level electricity policies and efforts to rethink federal energy policy. We should ask: to what extent do new policies under consideration reduce the major barriers to building clean energy and transmission while addressing the shortcomings that have made past policy less durable?

A future paper will detail the priority solutions that make progress on each of the project development barriers while improving our toolkit to overcome the political barriers that impede durable policy.

Contents

Project Development Barriers: Making it Harder to Build

Clean energy technologies are mature and cost competitive, if not least cost, across the country. Yet we are not building clean energy as fast as necessary, and in many places we are building new gas plants instead, raising costs for customers and intensifying the climate crisis. This trend is the result of several barriers that make it more difficult to build clean energy.

Interconnection

The Barrier

The interconnection process is one of the most significant constraints on clean energy deployment in the United States. At the end of 2023, nearly 2,600 gigawatts (GW) of generation and storage were queued, which is more than double the U.S. installed capacity (~1,280 GW). Today’s grid was built around a small number of large, centralized fossil fuel plants; the grid must now accommodate thousands of diverse, geographically distributed projects. Processes that were designed for a handful of large plants per year are now evaluating orders of magnitude more proposals, each with more complex grid interactions. These processes are not able to adequately handle the current grid, nor have they kept pace with development in grid planning and analysis tools. The result is a massive backlog of projects waiting to interconnect to the grid and a review system that is fundamentally misaligned with the scale and pace of the energy transition.

Developer experience confirms that interconnection challenges rank among the most decisive barriers to clean energy buildout. In the 2024 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) developer survey, respondents ranked interconnection delays and network upgrade costs higher than permitting, supply chain constraints, or workforce shortages as reasons for project cancellations or deferrals. Many projects face cost uncertainty on the order of tens to hundreds of millions of dollars as interconnection studies shift responsibility for broad system upgrades onto single developers. Interconnection costs are rising, and it is difficult for developers to predict what their interconnection bill will be at the end of the process. This unpredictability increases financing risk, reduces developer participation, and leads to large-scale attrition.

Outdated processes for evaluating and approving new projects have led to enormous project delays, averaging 4-5 years from request to commercial operation. This delay has raised prices and led some grid operators to keep old, expensive coal plants online in lieu of new capacity. Both of these trends benefit incumbent transmission and generation companies, who have significant decision-making power over the entities that control interconnection, making it difficult to update the processes. Clean energy projects also face higher interconnection costs than gas projects because they are more likely to need transmission upgrades to connect to the grid, which increases the chances of project cancellation.

These barriers have direct system-wide consequences. Only about 15 to 20 percent of projects that enter the queue ultimately reach commercial operation, meaning most of the clean energy capacity counted as “planned” will not materialize unless interconnection processes are reformed. Long queue timelines and uncertainty also make it more difficult to finance projects. The result is slower emissions reductions, delayed IRA-driven investment and job creation, and higher costs for consumers as operators extend the life of aging coal and gas resources to meet growing load.

The Past Playbook

Federal interconnection policy has largely gone through the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). In 2023, FERC issued Order 2023, which made significant changes intended to speed up interconnection and increase certainty for new projects. The rule (1) replaced outdated serial studies, in which operators study projects one by one as their applications come in, with cluster studies, in which operators study projects in batches, (2) required grid operators to speed up study timelines and imposed penalties for failing to meet deadlines, and (3) directed grid operators to update rules to reflect technological advancements, like grid-enhancing technologies and hybrid solar-plus-storage projects. Some grid operators have gone further than Order 2023 to improve interconnection processes, and some states have pushed grid operators for more ambitious reform. In addition to FERC rules, the federal government has also provided limited resources to grid operators to improve interconnection processes.

To date, federal efforts have largely fallen short of what’s necessary to reform interconnection processes to enable adequate buildout of clean energy, and in most places states have limited tools. For one, FERC rules rely on effective implementation from grid operators, which has been a mixed bag. Order 2023 also strayed from making more fundamental changes to the interconnection process, like fixed entry fees that provide certainty to developers or proactive modeling and transparency of information to allow projects to connect quickly in places with transmission headroom. It fully does not address the fundamental problem that rising, variable interconnection costs are killing projects. The federal government has limited resources to support grid operators through, for example, funding for increased staffing or new technology to automate studies.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The next era of energy policy must radically transform the way we connect projects to the grid to enable faster, greater deployment of clean energy, including through an expanded role for federal and state governments. Policy must shorten study timelines using automation and other new technology, enable smarter planning with proactive modeling and greater transparency for developers, increase upfront cost certainty, and reduce the amount that projects end up paying for interconnection. And in addition, the next playbook must address governance and decision-making structures that favor incumbents who benefit from a congested grid.

Siting & Permitting

The Barrier

Siting and permitting processes have become two of the most visible friction points in the clean energy buildout. While federal policy receives the most attention, most clean energy siting and permitting decisions are made at the state and local level, where zoning boards, planning commissions, county supervisors, and community members have significant influence over whether a project proceeds. In many states, local jurisdictions have adopted new ordinances that restrict or outright ban wind, solar, and transmission development. According to recent analyses, roughly one-fifth of U.S. counties now have formal restrictions on clean energy, and many more are considering them. Even in states with strong climate and clean energy targets, municipal-level land use rules can effectively halt projects that align with statewide goals.

These local barriers are often rooted in concerns about landscape change, perceived impacts on property values, agricultural land use, wildlife, or community identity. But they are also a reflection of who benefits and who bears the immediate impacts of clean energy development. Benefits like lower system-wide electricity prices, cleaner air, and national decarbonization progress tend to be distributed widely, while the visual and land-use impacts are concentrated locally. Developers may not readily have the resources to meet community needs to come to agreement on projects, and federal and state governments often do not have adequate resources to support community benefits. Misinformation and disinformation—spread by incumbent interests who stand to lose money with greater clean energy or transmission deployment—also seed opposition in communities.

Permitting requirements add an additional layer of delay and uncertainty. Most clean energy projects, particularly solar and storage projects—which make up the bulk of new planned capacity—rarely trigger major federal environmental statutes and primarily deal with state-level permitting. Developers must navigate state statutes governing clean water, conservation, and environmental impacts, which serve important purposes but are often still implemented through outdated processes (e.g., many states still require paper permits; in Arizona, digitization reduced timelines for one permit process by 91 percent) administered by understaffed agencies. Projects such as transmission lines, offshore wind facilities, pumped storage hydropower, nuclear plants, geothermal projects, and any project on federal land or receiving federal grants generally must also navigate federal permitting processes. When new projects trigger federal review, they must comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and sometimes other federal permitting statutes, like the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the National Historic Preservation Act, and the Endangered Species Act. These reviews can take multiple years, particularly when agencies have limited staffing or when studies must coordinate across several state and federal entities and jurisdictions.

Delays from local siting and state and federal permitting translate directly into cost escalation and canceled projects. Developers report that siting challenges can add years to development schedules and millions of dollars in carrying costs before a shovel ever hits the ground. For technologies like wind and solar, where the business model depends on tight capital cost margins, extended pre-construction periods can be the difference between a viable project and one that never breaks ground. Transmission development is even more exposed: large lines can spend a decade or more navigating route identification, landowner negotiations, environmental review, and litigation. Without new transmission capacity, interconnection backlogs grow, power costs increase, and states are forced to rely on older fossil resources simply because they are already in place.

Yet, the challenge isn’t so simple. It is not simply “local opposition” or “slow permitting.” It is that the scale of clean energy land use today is fundamentally different from the past century of centralized fossil energy development. We are building more projects, in more places, at a pace that communities have not previously experienced.

The Past Playbook

Siting and permitting reforms have increasingly been part of the federal and state policy agenda. Reforms have largely focused on process changes and improving coordination across agencies, with some focus on building capacity for analysis and review in some federal agencies and states. In general, these reforms are insufficient and not widespread enough to match the urgency and scale of the U.S. energy transition.

The federal government has pursued a range of reforms over the past few years to improve the permitting process for projects that involve federal land, funding, or regulatory triggers. Key cross-agency initiatives include the Coordinated Interagency Transmission Authorizations and Permits Program, which made the Department of Energy (DOE) the lead agency for coordinating environmental review and permitting for transmission lines, and FAST-41, which aims to align multiple agency reviews and reduce duplicative permitting processes. Agencies have taken additional steps to improve individual permitting processes. For example, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) designated solar and wind energy zones on public lands to reduce conflicts and expedite approvals, and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management modernized offshore wind leasing and programmatic NEPA reviews (although the Trump Administration overhauled these reforms by halting all offshore wind leasing).

Several states have attempted to reduce delays and uncertainty by centralizing siting authority and standardizing permitting rules. For example, New York’s Office of Renewable Siting and Massachusetts’ Energy Facilities Siting Board can override local opposition for large projects, while other states provide model ordinances to guide counties on setbacks, noise, and environmental protection. DOE has also helped states: the agency provided a small amount of technical assistance to states to help local governments with planning, siting, and permitting decisions and a larger tranche of funding for transmission projects to provide benefits to local communities to help with siting and community buy-in. In some places, these reforms have improved consistency across counties and reduced the influence of NIMBY-driven delays.

This playbook, while directionally correct, has fallen short of what is necessary. Local restrictions on clean energy continue to proliferate, siting power plants and large transmission lines remains a major challenge, and many state and federal permitting processes still pose significant barriers. Existing efforts have several gaps: (1) many states have not addressed local restrictions on development, (2) process improvements, especially at the state level, have happened in a piecemeal fashion and have not extended to the full suite of state-level permitting requirements, (3) existing efforts often do not cover the full set of solutions (e.g., broken permitting for customer-owned solar is a huge impediment that keeps U.S. solar costs much higher than other countries), (4) governments and developers have insufficient tools to ensure that local communities get what they want out of projects, and (5) efforts to increase state and federal government capacity (i.e., hiring and training the right staff and increasing analytical capabilities) have fallen far short of what is needed to have a fast, effective, and responsible permitting and siting process.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The next era of energy policy must wrestle with the fundamental siting and permitting challenges and introduce new frameworks for planning, permitting, and building projects. That means upfront planning to make major decisions about tradeoffs between clean energy, water, conservation, and other goals, expanding the tools and resources necessary to ensure that local communities benefit from projects, dramatically improving government capacity to do siting and permitting well, and taking a holistic approach across federal, state, and local governments to prevent new bottlenecks from emerging.

Misaligned Incentives

The Barrier

Most clean energy and grid upgrade projects are financed by private capital and procured or built by companies, either utilities or independent power producers. The profit motives of those financiers and companies determines the solutions they invest in, within the bounds of policy requirements. Across states and regions, outdated utility regulations and market designs have created flawed incentives that have limited investment in some necessary solutions and resulted in overinvestment in others. Utilities have wielded significant political power, built by lobbying with ratepayer money, to maintain today’s incentive structure.

For example, in vertically integrated states, utilities are incentivized to prioritize capital expenditures that earn them the highest returns, within the bounds of commission approval. This incentive structure deprioritizes solutions like increasing imports of clean energy through new transmission and leveraging distributed resources like customer-owned solar.

Most commissions are often not well-equipped or willing to ensure that utilities pursue the full toolkit. In most states, utility planning is driven by the utilities, who conduct detailed analysis and provide proposals on planning and ratemaking to their commissions. Commissions have more limited capacity to conduct analysis and interrogate utility proposals.

Organized markets also have flawed incentive structures. For example, incentive structures in organized markets were generally designed around an electricity grid made up of a small number of large power plants. As a result, market rules and incentive structures provide limited to no support for distributed energy resources, which makes it harder to finance these projects. Governance structures exacerbate this issue. In some organized markets, incumbent generators have significant decision-making power in important determinants of clean energy deployment, including interconnection and transmission planning. Some organized markets have maintained rules that make it difficult to connect new power plants.

Misaligned incentives reduce the effectiveness of other policy solutions. For example, tax credits to reduce the cost of clean energy projects are most effective if utility companies have a profit incentive to build those projects instead of other generation types. The effectiveness of bulk transmission grant programs is limited by the willingness of utility companies to collaborate on projects.

The Past Playbook

Federal policy has largely ignored utility incentive structures and instead attempted to influence private-sector behavior by working within existing incentive structures (e.g., by making it easier for utility companies to use tax credits to build clean energy). Federal agencies have attempted to overcome misaligned incentives through regulations (e.g., pollution standards on power plants that require generation owners to make changes). Some efforts to change incentives structures (e.g., the Clean Electricity Payment Program included in the 2021 Build Back Better Bill) have gained momentum but failed to pass.

Many states have also used tools that operate within existing incentive structures, like renewable portfolio standards that require utilities to procure an increasing share of their electricity from clean sources. States have attempted to change incentive structures to varying extents. More than 15 states have adopted some form of performance-based ratemaking to align utility incentives with desired outcomes. However, these efforts vary in how comprehensively they have changed the dominant incentives for companies.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The next era of energy policy must reform incentives to realign private sector interests with public benefit, including affordable bills, reliability, and decarbonization. To achieve the scale, speed, and depth of transformation needed to address the challenges facing our grid, policy must address misaligned incentives for distribution utilities, generation owners, and integrated utilities in different regulatory contexts. That requires a greater focus on realigning incentive structures at the state and regional level (through organized market reform) as well as creative federal tools to directly change incentives or help states and organized markets to do so. Increasing regulator scrutiny of utilities and bolstering capacity at commissions must also play a larger role moving forward to ensure that utilities are focusing on the best solutions, not just what is most profitable. Greater use of publicly owned or publicly financed projects can also ensure investment in solutions that are underutilized by private companies.

Financing

The Barrier

The federal government has created new financial barriers for clean energy projects. OBBBA’s changes to tax incentives and increased regulatory and permitting uncertainty make clean energy projects more expensive and harder to finance. Macroeconomic changes like persistent inflation and other uncertainty, including on tariffs and interest rates, have also affected investment.

While the clean energy industry has continued to move forward (2025 investment in solar, storage, and wind is similar to 2024 levels, and the industry is benefiting from demand growth, as many projects are able to find offtakers like tech companies willing to pay higher prices), the full effects of federal policy changes are likely delayed, as the tax credits have not fully expired. Moving forward, financing may become a larger barrier. In addition, rising utility bills have opened a conversation about the cost of private finance for grid projects and whether there are alternative approaches that come with lower costs for customers.

Financing less mature clean energy technologies, like advanced nuclear, enhanced geothermal, and aggregated distributed generation (i.e., virtual power plants), remains a major issue.

The Past Playbook

Financial support has played a dominant role in the federal energy policy playbook. Tax incentives, which were dramatically expanded by the IRA and pared down by OBBBA, have been central to energy policy for decades. Grant and loan programs, also dramatically expanded by the IRA, have also been a core driver of clean energy deployment, grid upgrades, and large-scale demonstrations and commercialization of advanced energy technologies. States have also used tax incentives, grant programs, and green banks to finance and incentivize clean energy and grid projects. This model has largely been successful at deploying mature technologies like wind, solar, and storage, but it has fallen short when it comes to commercializing some newer clean energy technologies. Gaps also remain in financial support for projects that struggle to get private capital.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Financing and financial support should continue to be a major pillar of clean energy policy. The next era must incorporate a broader, more diverse set of financing tools in the capital stack, including state-led public financing for more types of projects and state efforts to create demand certainty for clean energy by leveraging procurement and working with corporate buyers.

Grid Planning

The Barrier

Today, the U.S. bulk transmission system faces significant constraints that limit where new clean energy projects can be built and threaten reliability. Congestion already causes curtailment of low-cost low-carbon power, higher consumer electricity prices, and dampened investment in clean energy. Many regions with abundant clean energy resources simply do not have enough high-voltage transmission capacity to deliver that power to population centers. As a result, developers are increasingly unable to move generation projects forward even when siting, permitting, financing, and interconnection queue positions are in place.

These challenges stem in large part from fragmented and inadequate planning processes. Coordinated planning is essential to ensure that transmission is expanded in the right places and that new clean energy investments flow to areas with sufficient transmission capacity. Despite the need for coordination, the United States conducts virtually no interregional transmission planning, and regional planning has been lacking in many regions. The result is piecemeal grid planning, as transmission providers and developers focus on smaller lines which meet near-term needs and are profitable within their own footprint. Planning for these smaller lines is easier as fewer parties are involved. Where we have successfully built larger regional lines, they are the result of transmission providers conducting robust planning processes. And because no unified authority or planning framework exists to shepherd large, high-impact projects across regions, the U.S. has built essentially zero major interregional transmission lines in recent history.

Lack of coordination between transmission and generation planning also creates inefficiencies and prevents smart development. In deregulated markets (and some vertically integrated states), transmission and generation planning processes occur largely in isolation without systematic processes to align long-term clean energy expansion with major grid upgrades.

Together, these gaps make expanding the transmission system an inefficient process at best, and an unworkable process at worst, at precisely the moment when the need for additional capacity is growing most rapidly.

The Past Playbook

Policymakers have made progress in addressing transmission planning bottlenecks, but these reforms remain far short of what’s needed. FERC Order 1920 is the most significant recent step: it requires long-term, forward-looking, multi-value regional planning. It was designed to improve transparency in the planning stages and help regions identify beneficial projects earlier. Yet the rule stops at regional borders and thereby doesn’t meaningfully advance interregional planning.

A patchwork of state and regional efforts has emerged alongside federal reforms. New Mexico created a new entity called the Renewable Energy Transmission Authority to map and finance new lines. Similarly, Colorado created the Colorado Electric Transmission Authority to plan and develop transmission lines to meet power needs, unlock clean energy, and lower costs. California conducts long-term transmission planning intended to incorporate transmission needs to accommodate clean energy deployment required to meet the state’s climate goals. Federal tools like National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors (NIETCs) were designed to accelerate siting of critically important lines, and part of DOE’s Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnerships (GRIP) funding has helped bring utilities, states, and developers together to plan large projects. On the interregional front, DOE has conducted analysis to demonstrate where new capacity would create the greatest benefits and inform planning.

These efforts certainly make progress and will likely result in expansion of local and regional transmission capacity. The magnitude of progress will depend in large part on how transmission providers implement Order 1920—for most regions, compliance filings will be submitted this month (December 2025) or by June 2026.

However, this playbook had significant gaps and pitfalls. Lack of interregional planning is the most glaring gap, but other tools had limitations, too. GRIP had limited funding and power to solve cost allocation disputes. NIETCs did not translate into built infrastructure. In many places transmission planning will not take into account the long-term clean energy expansion required for deep decarbonization, leaving high-value opportunities—like pairing wind resources with long-distance transmission—unrealized. The result is a set of reforms that move in the right direction but still fall short.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The next era of energy policy must tackle interregional planning, while following through on Order 1920 with effective implementation. We must require transmission providers to plan decisively for futures with significant load growth and levels of clean energy deployment necessary for deep decarbonization. Future federal policy must also expand the government’s tools to bring parties to the table for smart, effective planning. In parallel, states should continue to use creative policies, like Colorado and New Mexico’s transmission authorities, to strategically plan new transmission lines to maximize benefits. And the next era must also include national, forward-looking land-use planning for clean energy deployment, in sync with transmission planning.

Supply Chains

The Barrier

Grid components, such as electrical steel and transformers, are necessary to increase grid capacity to support additional generation and load. However, grid component supply chains are still suffering from disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and lack of domestic manufacturing capacity. The rising demand for grid components and battery technology have further stressed supply chains, drawing out lead times and increasing prices. For example, across transmission and distribution equipment, the lead time for components averaged 38 weeks in 2023, nearly double from the year prior, with costs escalating nearly 30 percent year-over-year. Bottlenecks in the supply chains from upstream suppliers to manufacturers among these components risk power system stability, the ability to deploy clean energy, and the ability to build new industrial production and technology facilities at scale.

The Past Playbook

Federal policy has increasingly focused on building secure supply chains for clean energy technologies. The IRA included tax credits, grant programs, and loan authority to build out domestic supply chains for clean energy and storage technologies. The federal government has also used demand-side pressure to bolster supply chains (e.g., through a bonus tax incentive for clean energy projects that use domestic content and Build America Buy America requirements on federal grant programs). These policies led to major investment in domestic supply chains.

This playbook was quite successful at building out domestic supply chains for some industries, but it had major gaps. For example, the IRA and BIL included no dedicated support for grid components, and the minimal support that was embedded in larger programs was insufficient. Federal demand-side programs were structured as incentives for downstream industries to use domestic content, but this design had too much uncertainty to sufficiently derisk upstream domestic supply chains.

Today’s programs have also struggled to respond quickly when conditions change. For example, the federal government had limited tools with which to respond when the utility industry faced a debilitating shortage of large power transformers or when it became clear that incentives were not large enough to drive domestic investment for some clean energy components.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The next era of energy policy must build on the same financial tools to support secure supply chains that enable clean energy deployment and grid upgrades. The playbook must include policies that more directly create demand for domestic components to provide certainty for manufacturers and derisk new investments. Future policy must also provide more flexible and dynamic tools to rapidly address supply chain shortages as they arise.

Political Barriers: Making it Harder to Pass, Implement, and Defend Policy

Clean energy advocates have focused on economic competitiveness, climate, and public health benefits as the winning messages to support and defend policies. The BIL and IRA came out of this model, and the architects of those policies hoped that the industry that benefitted from these policies would step up to defend them. While this strategy has enabled passage of significant new policies, it has failed to withstand changing political dynamics. The swift rollback of major parts of BIL and IRA is the prime example. Our ability to successfully implement and defend clean energy policies—and make further progress—has been hampered by several key political barriers. The next era of clean energy policy must address these barriers to be successful.

Energy Affordability

The Barrier

Rapidly rising utility bills have become an urgent cost-of-living issue. People pay 13 percent more for electricity in 2025 than they did in 2022, and nearly 40 percent of households sometimes have to choose between paying for food and medicine or keeping the lights on.

Rising electricity prices are a political barrier to some clean energy policies. For example, states have struggled to follow through on procurement of advanced clean energy technologies like nuclear and offshore wind as prices have risen. New York recently cancelled a planned transmission line, using affordability as a justification. Clean energy opponents are using prices to oppose climate policies, even though deployment of wind and solar has generally reduced rates. Concerns about electricity affordability make it difficult to justify major grid infrastructure investments under current regulatory and ratemaking structures, as additional spending to update the grid will lead to near-term bill increases. High prices also make it difficult to replace direct fossil fuel use in vehicles, buildings, and factories with electricity.

The Past Playbook

Federal energy policy has largely dealt with affordability in two ways.

First, the federal government has provided important but limited direct assistance to struggling households through the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which helps households pay for energy, and the Weatherization Assistance Program, which funds energy- and cost-saving home improvements. However, these programs are significantly underfunded and oversubscribed—many households that need support do not get it.

Second, federal financial support results in long-term savings. IRA incentives for low-cost clean energy were projected to reduce generation costs, which in the long term translates to lower prices. Tax incentives and grant programs for distributed energy resources and home energy improvements save energy and costs for customers that make upgrades. However, this approach falls short in two ways: (1) it does not address the root causes of rising electricity bills, which means bills will continue to rise, and (2) the benefits are long term and do not show up on peoples’ bills on politically relevant timelines.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The next era of energy policy must provide sufficient and swift relief for customers that are on the edge of catastrophe due to rising costs, make it easier to deploy cheap, clean energy to reduce generation costs, and target the root causes of high and rising bills to unlock a sustainable utility ratemaking regime that allows for major new investments in the grid without harming regular people. The new playbook must also include more effective cross-sector tools to cut total system and household costs, including by transferring planned spending on gas infrastructure to home electrification and grid upgrades where possible.

Incumbent Interests

The Barrier

Many solutions, including adding new generation in organized markets, relying more on regional and interregional transmission, and deploying distributed and demand-side solutions, threaten the profits of incumbent interests under current market and regulatory structures. For example, utilities make money through a return on qualified capital investments in things like power plants and distribution infrastructure. Increasing bulk transmission capacity to connect the Southeast with other regions would lead to more imports of lower cost clean energy, which would reduce the utilities’ reliance on local generation. That makes it harder for the utilities to justify capital expenditures in new power plants, which is how the utilities make a profit, so new transmission poses a threat to the business model. As a result, Southeastern utilities are opposed to policies that would expand bulk transmission to better connect different regions, even though these policies would reduce costs and increase reliability. These dynamics make it politically difficult to pursue policies that expand transmission capacity.

The Past Playbook

Federal clean energy policy has largely avoided changing incumbent incentive structures or decision-making processes at the state and regional level. Instead, policymakers have used financial incentives to bring incumbents to the table and increase their investment in clean energy and grid upgrades. As a result, the misaligned incentives described above, combined with decision-making structures that reward incumbents over innovation, make it difficult to fully address the barriers to clean energy deployment and grid upgrades at the necessary scale.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The next era of clean energy policy must address governance issues through reform of regional grid operators and public utility commissions. Strengthening the role of regulators is critical to reining in incumbent interests where they do not align with public benefit. It must also realign industry incentives (e.g., through performance-based ratemaking) where possible with affordability and decarbonization goals.

Delayed Impact

The Barrier

Another major political barrier is the lengthy time it takes to get from enactment and implementation to tangible benefits for people. Transforming major sectors of the economy is a time-intensive, multi-stage project, and climate advocates have accordingly focused on long-term goals, such as 100 percent clean electricity by 2035 or net-zero emissions by 2050. The IRA and BIL were made up primarily of multi-year (even some decadal) programs to drive major changes in the economy. As a result, the largest benefits were projected to come in the late 2020s and early 2030s, far outside the window of political memory. That mismatch makes it difficult for the public to understand the point of policies and in turn makes those policies hard to defend.

Where policies do have near-term benefits, those benefits have often been delayed by the implementation process. Successfully shifting the private sector requires precise policy and new programs, which take time to implement. Implementation of new programs can also run up against the government typically works, and that friction causes delays. Implementation delays make it difficult to connect the dots between policy and tangible improvements to peoples’ lives.

The Past Playbook

Policymakers have used three dominant approaches to overcoming this barrier. First, they tout near-term signs of economic change. For example, the Biden administration consistently cited private-sector investment in clean energy as a key metric to convince the public that the IRA and BIL were driving benefits for people. Second, they rely on the quickest economic changes to demonstrate impact. For example, the IRA and BIL drove a near-term increase in construction jobs. Real and announced job creation was the dominant message to support and defend these policies. Third, they cite projected benefits. For example, the Biden administration frequently cited the 1.5 million jobs and the $27 to $33 billion in energy cost savings that the IRA was projected to drive.

Attention to long-term impact is important for addressing long-term problems like climate change and load growth. However, politics runs on instant gratification. As of late 2024, only 39 percent of Americans had heard of the IRA. And federal energy policy failed to make a near-term dent in the issue that was most visible for people: utility bills.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The next era of clean energy policy must tangibly and visibly benefit people in the short term. The playbook must include a better balance of policies geared toward long-term transformation of the economy and policies focused on pressing issues for regular people. That means including programs that are designed for quick implementation and real-world change.

Conclusion: What’s Next?

The power sector sits at an inflection point. The challenges facing the grid are immediate, interconnected, and solvable but only if we confront the real sources of delay and dysfunction. Accelerating clean energy deployment requires moving beyond our old playbook—dominated by financial incentives and regulations that see-saw based on the political winds—toward a new approach that addresses both project development barriers that slow investment and construction and political barriers that impede durable policymaking. Building durable, effective energy policy demands a clear-eyed assessment of the barriers that have undermined smart policymaking and implementation.

In a forthcoming publication, we will move from diagnosis to action, detailing policy solutions that can unlock faster, more reliable project development while expanding the policy toolkit needed to overcome the political barriers that have prevented durable reform. Together, these solutions aim to strengthen grid reliability, rein in rising utility bills, and put the United States back on a credible path to decarbonization. These stakes could not be higher, and the opportunity to build a more affordable, resilient, and clean energy system has never been more urgent.

How DOE can emerge from political upheaval achieve the real-world change needed to address the interlocking crises of energy affordability, U.S. competitiveness, and climate change.

As Congress begins the FY27 appropriations process this month, congress members should turn their eyes towards rebuilding DOE’s programs and strengthening U.S. energy innovation and reindustrialization.

Politically motivated award cancellations and the delayed distribution of obligated funds have broken the hard-earned trust of the private sector, state and local governments, and community organizations.

Over the course of 2025, the second Trump administration has overseen a major loss in staff at DOE, but these changes will not deliver the energy and innovation impacts that this administration, or any administration, wants.