Culture Blast at the Kurt Vonnegut Museum

Charlotte Yeung is a Purdue student and New Voices in Nuclear Weapons fellow at FAS. Her multimedia show, Culture Blast, opens this week at the Kurt Vonnegut Museum in Indianapolis.

Best known for his anti-war novel Slaughterhouse-Five (1969), Kurt Vonnegut’s experience serving in World War II informed his work and his life. He acted as a powerful spokesman for the preservation of our Constitutional freedoms, for nuclear arms control, and for the protection of the earth’s fragile biosphere throughout the 1980s and 1990s. He remained engaged in these issues throughout his life.

FAS: Tell us about this project and its goals…

Charlotte: My exhibit, Culture Blast, weaves Kurt Vonnegut’s stance on nuclear weapons with current issues we face today. It serves as a space for preservation and linkage, asking the viewer to connect Vonnegut’s concerns to the modern day. It is also a place of artistic protest and education, meant to inform the viewer of the often ignored complexity of nuclear weapons and how they affect many different parts of society. I worked with Lovely Umayam and the team at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) to ideate and research what underpins this exhibit.

Why this medium?

I explore nuclear history and literary protest through blackout poetry, free verse, and digital illustration – contemporary forms of written and visual art that carries on Vonnegut’s artistic protest into the modern day.

In particular, I wanted to create art that can be accessible to everyone and not just people who go to the museum. Seeing a photo of a pencil drawing or a statue online is experiencing just the surface-level nature of a work of art. It lacks the other sensory components like seeing how the art fits with the wider space and how others react to it. A similar issue comes up if my poems were spoken word. That art form lives off of a crowd. My digital art and poetry is meant to be seen in both a museum setting and online setting. Viewers can watch a time lapse of my art and see the process of creating this work. The poetry is meant to be read rather than performed.

Can you share some of the backstory on a few of the multimedia pieces? How did the concept evolve as you worked on them?

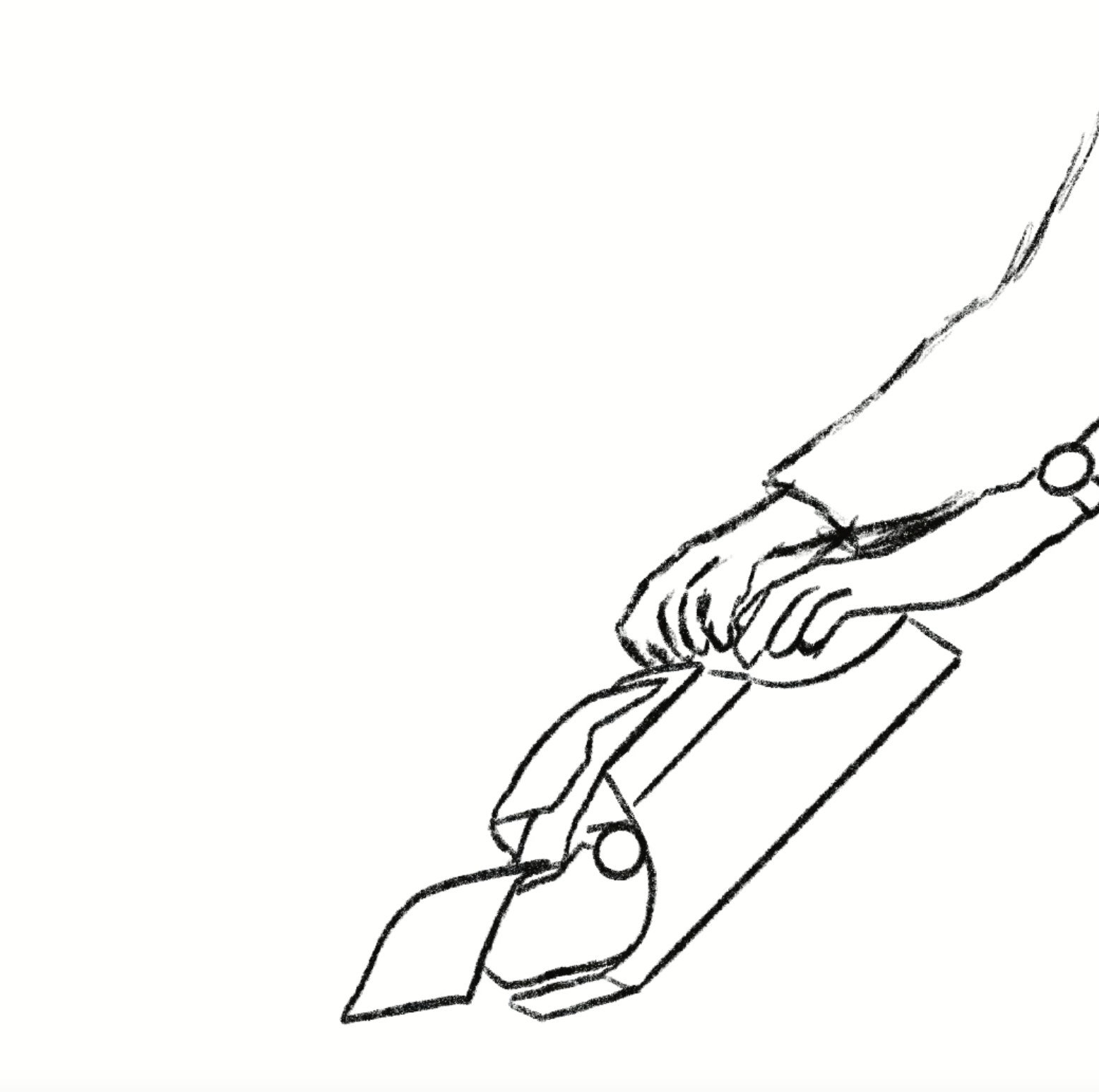

My favorite pair in the collection is Sketch 1 (the typewriter) and the blackout poem Protection in the name of public interest. I drew Vonnegut on his typewriter because I felt this to be the most symbolic image of his artistic protest. Though he wrote and sketched on countless personal notebooks, his work commenting on nuclear weapons can be found in some of his published stories. Vonnegut turned to his literary creativity to reflect on nuclear weapons, in particular scientists’ indifference to the suffering caused by the atom bomb, as seen in works such as Cat’s Cradle and Report on The Barnhouse Effect.

The uncensored version of my poem (Protection in the name of public interest) meditates on the bomb’s harm and also the long association between science and violence. I chose to create a blackout poem because in the immediate aftermath of World War II, the American government censored many of the photos and stories about what happened to the people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in effect erasing the lived experience of these people. It wasn’t until writer John Hersey’s account of the U.S. nuclear attacks, titled Hiroshima, was published in The New Yorker in 1946 that the American public had an uncensored understanding of what had happened in Japan.

In terms of the process, I began this thinking that I would draw a hand and a pencil but Vonnegut is strongly associated with his typewriter so I felt that it wouldn’t be as accurate to draw something else. I knew I would write a blackout poem and link it to censorship but I wasn’t sure what it would be called or what it would say. I ultimately wrote how I felt about the exhibit and what I’ve learned so far in the FAS fellowship and what I wanted to convey. I started blacking out the poem and left the main themes I wanted viewers to have from this exhibit.

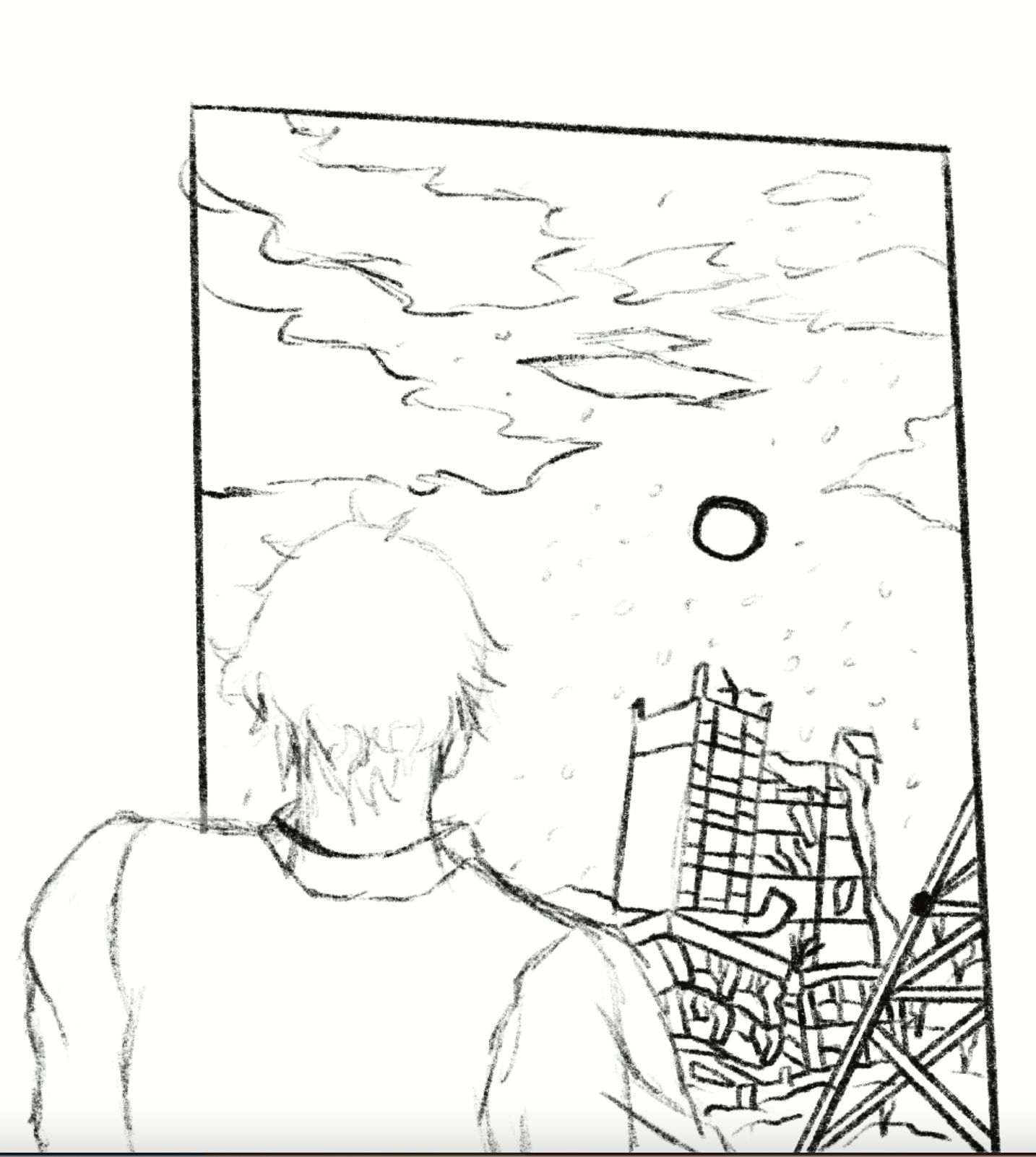

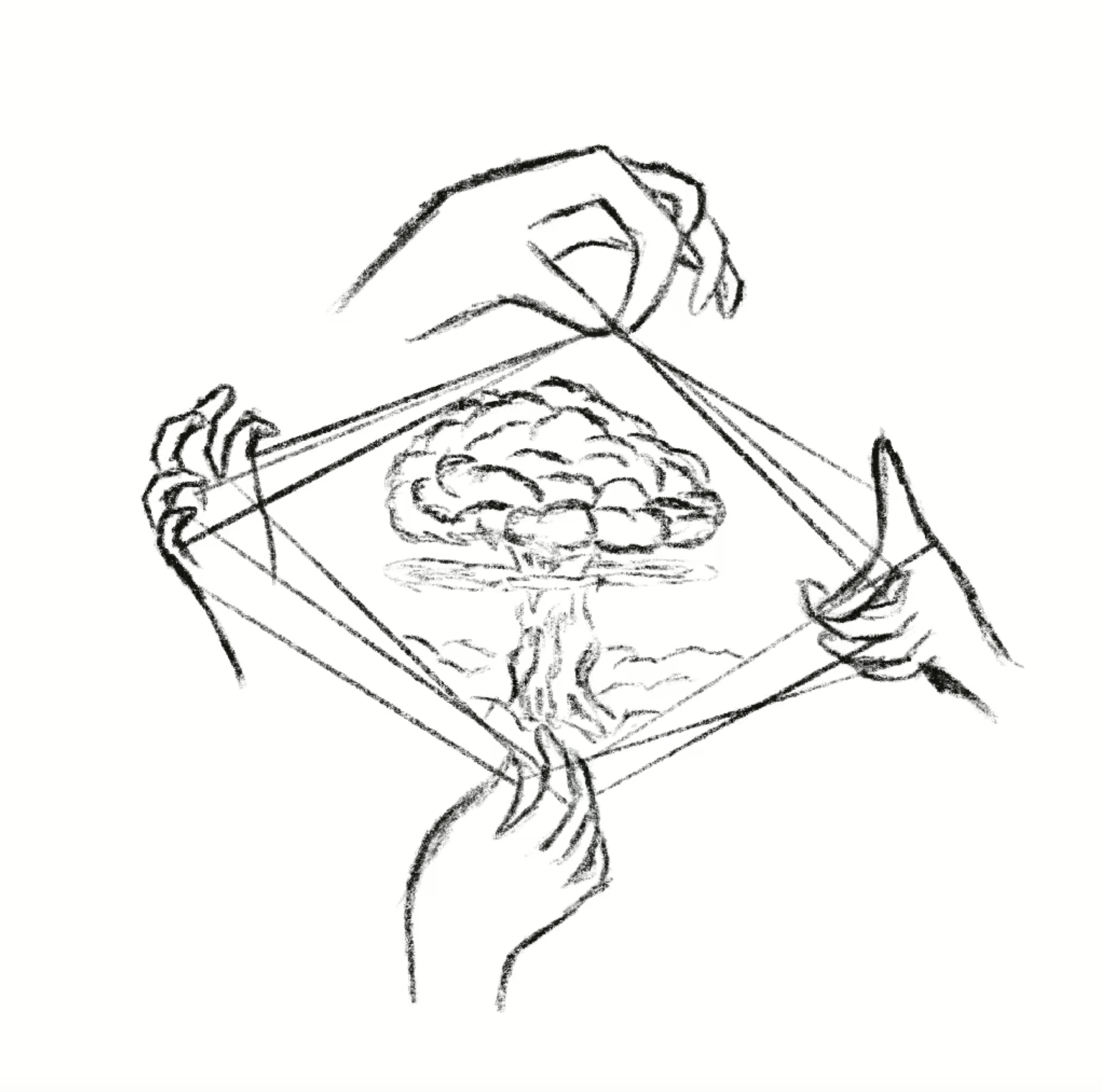

I am very fond of Sketch 2 (the cat’s cradle with the mushroom cloud inside) and the poem Labels. Labels was inspired by a lunch I had last year with a hibakusha, Yoshiko Kajimoto. She was 14 when the bomb fell and she spoke of the following days in vivid detail. I believe it was her testimony in particular that started me on this path towards researching the societal implications of nuclear weapons.

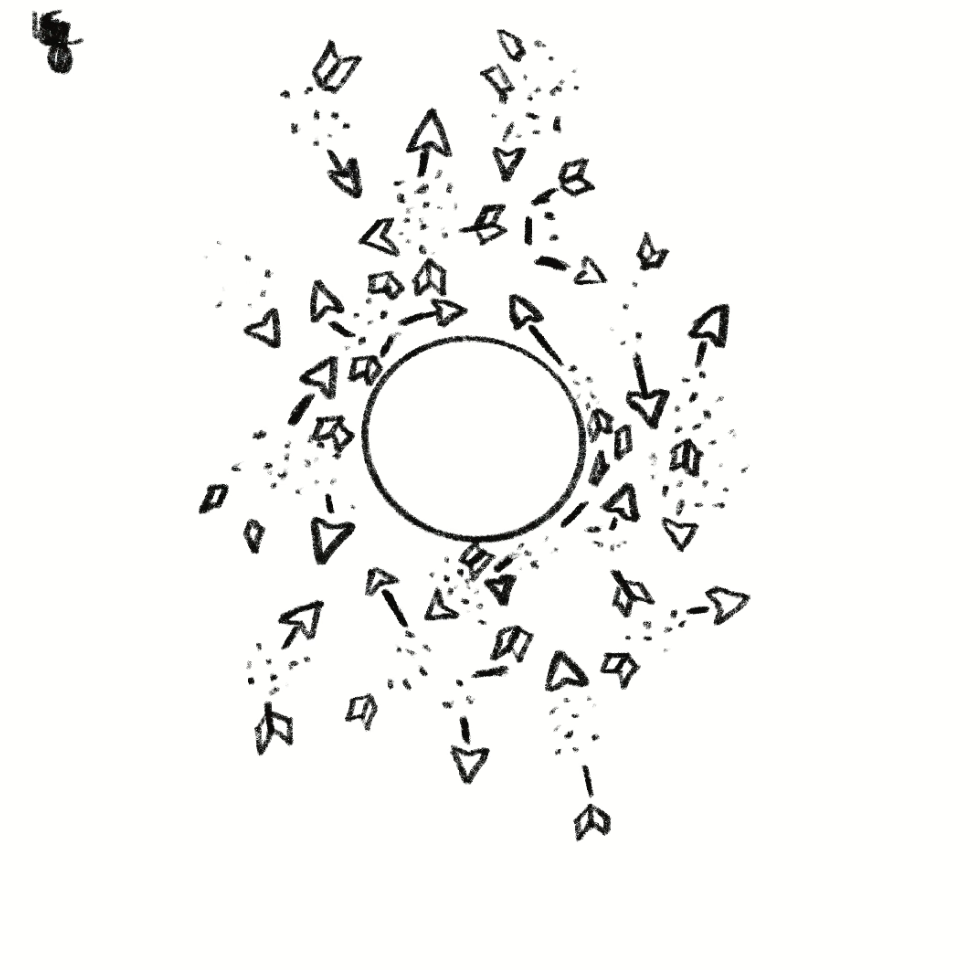

I drew an artistic interpretation of a cat’s cradle seeking to capture a mushroom cloud to communicate the concept of hyperobjects. According to Timothy Morton, a hyperobject is a real event or phenomenon so vast that it is beyond human comprehension. Nuclear weapons are an example of a hyperobject – its existence and use has had devastating ramifications touching different aspects of life that may be hard to fully comprehend all at once.

Nuclear weapons are both deeply present and hidden. On one hand, nuclear weapons are a constant security threat and have left deep scars on cities and bodies ranging from people in Japan to Utah downwinders. On the other hand, some of the information around them is clouded in mystery, and censored by different governments. Nuclear and fallout shelters built for nuclear warfare are considered to be Cold War relics; in the United States, they are largely abandoned or hidden, tucked in the basements of homes and schools, or located far out in the countryside away from cities. Some nuclear bunkers are parking lots in New York City and rumored rooms in DC. Secrecy and hidden locality are reasons why there isn’t as much widespread public knowledge or understanding of nuclear weapons.

Why is nuclear weapon risk a conversation we’re still having today? Where can people new to this issue learn more?

As a young person, I encounter many people my age who ask me why I care about nuclear weapons and why they matter in this day and age. It is, in a sense, meaningless to them. The violence of the bomb cannot be completely understood without hearing about the pain it wrought on people who experienced it firsthand. From burning skin and bodies to radiation poisoning, nuclear weapons have left permanent physical and psychological scars that are rarely spoken about, but have affected generations of families and communities.

I suggest reading more about what happened to individual A-bomb survivors to truly understand the effects of nuclear weapons. Humanizing those affected by war combats the practice of minimizing lives and experience to death counts. Great works to look at include Barefoot Gen (a manga on the Hiroshima bombings inspired by the hibakusha author’s experience), Grave of the Fireflies (a film about children grappling with the effects of the bombing), and the poem Bringing Forth New Life (生ましめんかな) by hibakusha poet Sadako Kurihara (which is about a woman giving birth in the ruins while the midwife dies from injuries in the middle of the process).

I knew the design from the beginning. It had to be a cat’s cradle because Vonnegut equates scientific irreverence to the bomb’s humanitarian effects to a cat’s cradle (an essentially useless game of moving strings with your fingers). The poem centers around hyperobjects, a term I grappled with in a university seminar with Dr. Brite from Purdue’s Honors College. I had never heard of the term before that class but I thought it was fitting for something like nuclear weapons. My research is interdisciplinary in nature and it seeks to analyze the cultural aspects of nuclear weapons that aren’t traditionally used by the political science community.

The third piece I’ll discuss is Sketch 5 and Rebuilding. This sketch of a rose is reminiscent of the Duftwolke roses sent from Germany to Hiroshima after the war as a symbol of rebuilding. It is also symbolic of Vonnegut’s experiences in World War II. He was caught in the firestorm that engulfed Dresden and he sheltered in a slaughterhouse. As one of the remaining survivors, he was forced to burn dead bodies in the aftermath. Vonnegut became an anti-war activist as a result of this experience. He also wrote Slaughterhouse-Five a book that grapples with trauma and PTSD after war. His writing was his way of finding closure and rebuilding, hence the title of the poem.

I wanted to end this collection on an optimistic note because, as dark and grim as war and nuclear weapons can be, there is great resilience in humanity. It takes monumental courage and hope to rebuild a city or mind or soul after facing the devastation of an all-consuming weapon.

I actually drew this while talking with FAS fellows and FAS advisors. I often draw to pay attention to important conversations (so all of my notebooks are filled with drawings). I thought the deep, complex observations about nuclear weapons and ethics and misinformation and other fields was so fascinating and I think as a result, I created my favorite drawing. I felt very hopeful during the conversation, because I saw so many people who were invested in this topic and were actively researching and discussing the implication of nuclear weapons.

Where can people see your show/contact you?

The showcase can be seen at the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library in Indianapolis, Indiana. If someone wants to speak about this topic with me, they can reach me at X or Instagram at @cmyeungg.

The Federation of American Scientists applauds the United States for declassifying the number of nuclear warheads in its military stockpile and the number of retired and dismantled warheads.

North Korea may have produced enough fissile material to build up to 90 nuclear warheads.

Secretary Austin’s likely certification of the Sentinel program should be open to public interrogation, and Congress must thoroughly examine whether every requirement is met before allowing the program to continue.

Researchers have many questions about the modernization of Pakistan’s nuclear-capable aircraft and associated air-launched cruise missiles.