Costs Come First in a Reset Climate Agenda

Key Takeaways

- The costs of climate policy influence whether reforms benefit society, as well as their likelihood of passage and durability. Four ways to categorize climate policy costs are: negative-cost policies (pro-growth policies with climate co-benefits); low-cost policies (costs below domestic climate benefits); medium-cost policies (costs below global climate benefits); and high-cost policies (costs above global climate benefits). Cross-partisan alignment is most evident among pro-abundance progressives and pro-market conservatives.

- Negative- and low-cost policies align with domestic self-interest and comprise a growing share of the abatement curve. For example, market liberalization in permitting, siting, electricity regulation, and certain transportation applications lower energy costs and have profound emissions benefits. A prominent low-cost policy is emissions transparency. Negative- and low-cost policies hold the most potential for durable reforms and are often technocratic in nature.

- Chronic underconsideration of costs has induced an overselection of high-cost policies and underpursuit of low- and negative-cost policies. Legislative policies, such as subsidies and fuel mandates or bans, often receive no ex ante cost-benefit analysis before adoption. Interventions receiving cost-benefit analysis, especially regulation, tend to underestimate costs.

- Innovation policy – namely public support for research, development, and early-stage deployment – can align with domestic self-interest and address legitimate market deficiencies. By contrast, industrial policy for mature technology carries high costs, often erodes social welfare, and is not politically durable. Notably, public support for mature technologies in the Inflation Reduction Act was not durable, but support remained for nascent industry.

- We recommend that a reset climate agenda focus on abatement results over symbolic outcomes, prioritize state capacity for technocratic institutions, and emphasize cost considerations in policy formulation and maintenance. Negative cost policies warrant prioritization, with an emphasis on mobilizing beneficiaries like consumer, non-incumbent supplier, and taxpayer groups to overcome the lobbying clout of entrenched interests. Robust benefit-cost analysis should precede any cost-additive policies and be periodically reconducted to guide adjustments.

Introduction

Public policy involves tradeoffs. The primary tradeoff for climate change mitigation is economic cost. Secondary tradeoffs include commercial freedom, consumer choice, and the quality or reliability of goods and services. Political movements seeking to address a collective action problem, such as climate change, are prone to overlook the consequences of tradeoffs on other parties, like consumers and taxpayers. This paper posits that the cost tradeoffs of climate change mitigation have been underappreciated in the formation of public policy. This has resulted in an overselection of high cost policies that are not politically durable and may erode social welfare. It also results in overlooking low or negative-cost policies that are durable and hold deep abatement potential. These policies can have broad political appeal because they align with the self-interest of the United States, however they typically require dispersed beneficiaries to overcome the concentrated lobby of entrenched interests.

A core, normative objective of public policy is to improve social welfare, which “encourages broadminded attentiveness to all positive and negative effects of policy choices”. Environmental economics determines the welfare effects of climate change mitigation policy by the net of its abatement benefits less the costs. The conventional technique to determine abatement benefits is the social cost of carbon (SCC). The barometer for whether climate policy benefits society is to determine whether abatement benefits exceed costs. Accounting for full social welfare effects requires consideration of co-benefits as well, granted these tend to be conventional air emissions with existing mitigation mechanisms covered under the Clean Air Act. Nevertheless, accounting for costs is essential to ensure climate policy benefits society.

Abatement costs also have a discernable bearing on the likelihood and durability of policy reforms. Climate policies exhibit patterns of passage, mid-course adjustments, and political resilience across election cycles based on the constituency support levels linked to benefit-allocation and cost imposition. This paper develops four policy classifications as a function of their abatement benefit-cost profile, and uses this framework to examine the political economy, abatement effectiveness, and economic performance of select past and potential policy instruments.

Political Economy and Policy Taxonomy

The translation of climate policy concepts into legitimate policy options in the eyes of policymakers can be viewed through the Overton Window. That is, politicians tend to support policies when they do not unduly risk their electoral support. The Overton Window for climate policy is constantly shifting within and across political movements with the foremost factor being cost.

In a 2024 survey of voters, the most valued characteristics of energy consumption were 37% for energy cost, 36% for power availability, 19% for climate effect, 6% for U.S. energy security effect, and 1% for something else. Democrats slightly valued energy cost and power availability more than climate effects. Independents and Republicans heavily valued energy cost and power availability more than climate effect.

Progressives have long exhibited greater prioritization of climate change policy, but cost concerns are driving an overhaul of the progressive Overton Window on climate change. In California, which contains perhaps the most climate-concerned electorate in the U.S., progressives have begun a “climate retreat” to recalibrate policy as “[e]lected officials are warning that ambitious laws and mandates are driving up the state’s onerous cost of living”. Nationally, a new progressive thought leadership think tank is encouraging Democrats to downplay climate change for electoral benefit. Importantly, they find that 61% of battleground voters acknowledge that “climate change is at least a very serious problem,” but that “it is far less important than issues like affordability.”

Similarly, veteran progressive thought leaders, such as the Progressive Policy Institute, now stress that “energy costs come first” in a new approach to environmental justice. While emphasising the continued importance of GHG emissions reductions, those policy leaders are making energy affordability the top priority, amid a broader Democratic messaging pivot from climate to the “cheap energy” agenda. The rise of cost-conscious progressives is particularly notable because the progressive electorate has expressed a higher willingness to pay to mitigate climate change than moderate and conservative electoral segments.

Economic tradeoffs, namely costs and more government control, has long been the central concern on climate policy for the conservative movement. The conventional climate movement messaged on fear and the need for economic sacrifice, which is the antithesis of the conservative electoral mantra: economic opportunity. Yet the conservative climate Overton Window emerged with a series of state and federal policy reforms when climate change mitigation aligned with expanded economic opportunity. However, pro-climate conservative thought leaders remain opposed to high cost policies, such as calling to phase out Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) subsidies for mature technologies.

Many leading conservative thought leaders continue to challenge the climate agenda writ large because of its association with high cost policies. For example, President Trump’s 2025 Climate Working Group report was expressly motivated by concerns over “access to reliable, affordable energy” while acknowledging that climate change is a real challenge. Similarly, a 2025 American Enterprise Institute report finds that the public is most interested in energy cost and reliability and unwilling to sacrifice much financially to address climate change. Meanwhile, climate-conscious conservative thought leaders like the Conservative Coalition for Climate Solutions and the R Street Institute continue to emphasize a market-driven, innovation-focused policy agenda that prioritizes American economic interests and drives a cleaner, more prosperous future. Altogether, it indicates a conservative Overton Window on negative and low-cost climate change mitigation.

While cost is driving the Overton Window within each political movement, it also buoys the potential for alignment across political movements. Political movements are not monoliths, but rather exhibit major subsets within each movement. The progressive movement has seen gains in popularity among its populist left flank, often identified as the “democratic socialist” wing, which contributes to ongoing debate about Democrats’ ideological direction. Climate policy initiated by this wing, however, is associated with high economic tradeoffs (e.g., degrowth) and has prompted a backlash within the progressive movement. By contrast, a subset of the progressive movement, sometimes labelled “abundance progressives,” has emerged to support a more pro-market, pro-development posture. This movement is especially responsive to energy cost concerns, and is an emerging substitute for the anti-development traditions of the progressive environmental movement. Overall, variances in the progressive movement are fairly straightforward to categorize linearly on the economic policy spectrum.

The Republican electorate views capitalism far more favorably than Democrats, but with modest decline in recent years. Republicans have trended away from consistently conservative positions associated with limited government, which historically emphasized the rule of law and a strict cost-benefit justification for government intervention in the market economy. They have migrated towards right-wing populism associated with the Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement. Right-wing populism is hard to operationalize for economic policy because it is not a standalone ideology, but a movement vaguely attached to conservative ideology. Generally, the “America First” orientation of MAGA implies positions based on the self-interest of the U.S., with the Trump administration prioritizing cost reductions in energy policy.

MAGA is further to the right of conventional conservatives on environmental regulation and general government reform. For example, conservatives have noted the contrast between conservative “limited, effective government” and the Department of Government Efficiency’s “gutted, ineffective government” reform approach. On the other hand, MAGA will occasionally back leftist policy instruments, such as coal subsidies, wind restrictions, executive orders to override state policies, and emergency authorities for fossil power plants. These are often justified to counteract the leftist policies passed by progressives (e.g., renewables subsidies, fossil restrictions, emergency authorities for renewables), resulting in dueling versions of industrial policy. In other words, ostensible overlap between MAGA and progressives on policy instrument choice actually reflects the use of similar tools used for conflicting purposes (e.g., restrictive permitting or subsidies for opposing resources; i.e. picking different “winners and losers”). Nevertheless, the disciplinary agent for right-wing energy populism has been cost concerns, which have influenced the Trump administration to pursue more traditionally conservative energy policies like permitting reform and lowering electric transmission costs.

This political economy identifies the broadest cross-movement Overton Window between moderate or “abundance progressives” and traditional conservatives. Regardless, both broad movements exhibit cost sensitivity and growing prioritization of U.S. self–interest. Distinguishing the domestic SCC from global SCC is essential to determine what policies are consistent with the self-interest of the U.S. versus the world as a whole. Traditionally, the U.S. government only considers domestic effects in cost-benefit analysis, yet the vast majority of domestic climate change abatement benefits accrue globally.

The first SCC, developed under the Obama administration, relied solely on a global SCC. Leading conservative scholars, including the former regulatory leads for President George W. Bush, criticized the use of the global SCC only to set federal regulations. They argued for a “domestic duty” to refocus regulatory analysis on domestic costs and benefits. Similarly, the first Trump administration used a domestic SCC. Although the second Trump administration moved to discard the SCC outright, this appears to be part of a regulatory containment strategy, not a reflection of the conservative movement’s dismissal of the negative effects of climate change. In other words, even if the SCC is not the explicit basis for policymaking, it is a useful heuristic for policymakers.

The proper value of the SCC is the subject of intense scholarly and political debate. It has fluctuated between $42/ton under President Obama, $1-$8/ton under President Trump, and $190/ton under the Biden administration (all values for 2020). The main methodological disagreement has been over whether to use a domestic or global SCC, with the Trump administration position guided by “domestic self-interest.” This suggests the original domestic and global SCC values may approximate the Overton Window parameters the best. This underscores the following policy taxonomy that characterizes climate abatement policies by cost relative to domestic and global SCC levels:

- Class I policy: negative abatement costs. Such policies are widely viewed as “no regrets” by scholars and political actors across the spectrum because they constitute sound economic policy that happens to carry climate co-benefits. The Overton Window is most robust for Class I policy. It typically takes the form of fixing government failure, such as permitting reform.

- Class II policy: positive abatement costs below the domestic SCC. These low-cost policies often fall within the Overton Window, because they advance U.S. self-interest (i.e., positive domestic net benefits). Class II policies have a small abatement cost range (e.g., up to $8/ton). One estimate puts them at 4-14 times smaller than the global SCC.

- Class III policy: abatement costs between the domestic SCC and global SCC. These medium-cost policies improve global social welfare, but are not in the self-interest of the U.S., excluding co-benefits. Most cost-additive policies that pass a global SCC test fall in this range, underscoring why climate change is an especially challenging strategic problem; those incurring abatement costs do not accrue most abatement benefits. Class III policies face inconsistent domestic support and often require international reciprocation to be in the self-interest of the U.S.

- Class IV policy: abatement costs exceeding the global SCC. These high-cost policies fail a climate-only cost-benefit test. In other words, Class IV policies erode social welfare, excluding co-benefits. Class IV policies may be effective at reducing emissions, but often leave society worse off. Class IV policies are challenging to pass and are hardest to sustain.

Policy Applications

There are myriad policies across the abatement cost spectrum. This analysis applies to particularly popular domestic policies already pursued or readily considered. This includes policies targeting the environmental market failure via direct abatement (GHG regulation) and indirect abatement (public spending, clean technology mandates, and fuel bans). It also includes policies targeting non-climate market failure, yet hold deep climate co-benefits (innovation policy). The analysis also examines policies that correct government failure and have major climate co-benefits (permitting, siting, and electric regulation reform).

Fuel Mandates and Bans

For the last two decades, the most prevalent climate policy type in the U.S. has been state level fuel mandates and bans. Last decade, the environmental movement came to prefer policies that explicitly promote or remove fuels or technologies, not emissions. This is despite ample evidence in the economics literature that market-based policies are more effective and carry far lower abatement costs. Nevertheless, the most common domestic climate policy instrument this century has been state renewable portfolio standards (RPS). The literature notes several key findings from RPS:

- RPS has substantial but diminishing abatement efficacy. RPS compliance drove the bulk of initial renewables deployment, but declined to 35% of U.S. renewables capacity additions in 2023. This reflects the improved economics of renewable energy, which went from an infant industry in the 2000s to a mature technology and the preferred choice of voluntary markets by the 2020s. Renewables also exhibit declining marginal abatement as penetration levels grow. This underscores the environmental underperformance of policies promoting fuel, not emissions reductions.

- Binding RPS increases costs, with large state variances based on target stringency and carveouts. RPS compliance costs average 4% of retail electricity bills in RPS states and reach 11-12% of retail bills in states with solar carve-outs. Stringency is a key factor, as some RPS are not binding due to strong market forces, whereas binding RPS increases costs. Abatement cost estimates of RPS vary widely, with one prominent study placing compliance with RPS from 1990-2015 at $60-$200/ton. Within the Mid-Atlantic region alone, implied states’ RPS compliance costs in 2025 ranged from $11/tonne to $66/tonne, with solar carveout compliance clocking in at $70/tonne to $831/tonne. The future abatement cost of renewables integration is highly sensitive to RPS stringency and technology cost assumptions, with one estimate of implied abatement costs ranging from zero (nonbinding) to $63/tonne at 90% requirement in 2050. This evidence qualifies RPS as a class II to class IV policy, depending on its design.

- States with stringent RPS face challenging compliance targets, prompting calls for reforms to mitigate cost. Compliance with interim targets has generally been strong but stringent RPS states are beginning to fall behind on their targets. For example, renewable energy credit (REC) costs are nearing alternative compliance payment levels. To reduce costs, popular reform ideas have included delaying compliance timelines, adopting a clean energy standard to capture broader resource eligibility, or making RECs emissions weighted.

- Modest RPS exists in some conservative states but aggressive RPS policy has, generally, only proven popular in progressive states. As of late 2024, 15 states plus the District of Columbia had RPS targets of at least 50% retail sales, and four have 100% RPS. Sixteen (16) states have adopted a broader 100% clean electricity standard, though the broad definition of clean energy dilutes expected abatement performance in some states. Overall, renewable or clean portfolio standards do not appear to hold broad Overton Window alignment potential beyond modest applications.

Micro-mandates have also sprung up, primarily in progressive states. These have often targeted the promotion of nascent or symbolic energy sources that the market would not otherwise provide, with the costs obscured from public view (e.g., rolled into non-bypassable electric customer charges). A good example is offshore wind requirements in the Northeast, which carries a high abatement cost (over $100/ton).

Fuel bans have become increasingly popular climate policy in progressive states and municipalities. Beginning in 2016, a handful of progressive states began banning coal. However, this does not appear to have created much cost or abatement benefit, as evidenced by a lack of commercial interest in coal expansion in areas without such restrictions. In fact, neither federal nor state regulation was responsible for steep emissions declines from coal retirements. Coal retirements were mostly driven by market forces, especially breakthroughs in low-cost natural gas production and high efficiency power plants. Policy factors, like the Mercury and Air Toxics Rule, were secondary drivers of coal plant retirement.

Around 2020, California, New York, and most New England states began adopting partial natural gas bans or de facto bans on new gas infrastructure through highly restrictive permitting and siting practices. Unlike coal restrictions, these laws have markedly decreased commercial activity, namely gas pipeline and power plant development, and in some cases caused economically premature retirements. This has caused “pronounced economic costs and reliability risk.” Resulting pipeline constraints drive steep gas price premiums in these states, which translate into a core driver of elevated electricity prices.

Insufficient pipeline service in the Northeast is especially problematic, as demonstrated by a December 2022 winter storm event that nearly led to an unprecedented loss of the Con Edison gas system in New York City that would have taken weeks or months to restore. Further, preventing gas infrastructure development does not provide a clear abatement benefit, because more infrastructure is needed to meet peak conditions even if gas burn declines. A prominent study found a 130 gigawatt increase in gas generation capacity by 2050 was compatible with a 95% decarbonization scenario.

Progressive states and municipalities have also pursued natural gas consumption bans. This policy may carry exceptional cost, especially for existing buildings, with potentially well over $1 trillion in investment cost to replace gas with electric infrastructure. One estimate put the cost of natural gas bans at over $25,600 per New York City household. A Stanford study projected a 56% electric residential rate increase in California from a natural gas appliance ban. Generally, conservative thought leaders and elected officials have opposed natural gas bans for cost as well as non-pecuniary reasons, including security concerns and the erosion of consumer choice. This applies even for prominent members of the Conservative Climate Caucus. Altogether, gas bans are considered class IV policy with virtually no Overton Window alignment.

GHG Transparency

GHG regulation takes various forms. The least stringent is GHG transparency, which addresses an information deficiency and lowers transaction costs in voluntary markets. This begins with reporting and accounting requirements on emitters (Scope 1 emissions). Public policy can help resolve measurement and verification problems that have eroded confidence in voluntary carbon markets. GHG transparency policy can also standardize terminology and provide indirect emissions platforms. For example, making locational marginal emissions rates on power systems publicly available lets market participants identify the indirect power emissions of power consumption (Scope 2 emissions). Progressives have consistently favored GHG transparency policy, while conservatives have typically supported light-touch versions of it like the Growing Climate Solutions Act.

The second Trump administration recently pursued removal of basic GHG reporting requirements on ideological grounds, specifically repeal of the GHG Reporting Program (GHGRP). This appears to reflect an optical deregulatory agenda over an effective one. Conservative groups have warned of the downsides of GHGRP repeal. Pressure to course correct may prove fruitful, given that the industry the Trump administration aims to assist – oil and natural gas – maintain that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) should retain the GHGRP. A recent analysis found that if states replace the GHGRP, new programs will be more expensive (Figure 2).

Many regulated industry and conservative groups instead support a low compliance cost GHG reporting regime with durability across future administrations. This not only applies to direct emissions reporting but indirect emissions reporting, as in the absence of federal policy industry faces a patchwork of compliance requirements across states and foreign governments. The same economic self-interest rationale justifies a role for limited government in emissions accounting, with an emphasis on the capital market appeal of showcasing the “carbon advantage” of the U.S. in emissions-intensive industries. An example is liquified natural gas, whose export market is enhanced by showcasing its lifecycle emissions advantage over foreign gas and coal.

The abatement effectiveness of GHG transparency has grown appreciably in the 2020s, as voluntary industry initiatives have sharply increased. This policy set enables an efficient “greening of the invisible hand” with staying power, as corporate environmental sustainability efforts appear resilient regardless of political sentiment, unlike corporate social endeavors. In fact, the aggregate willingness to pay for voluntary abatement from producers, consumers, and investors suggests that well-informed domestic markets go a long way towards self-correcting the externality of GHGs (e.g., convergence of the private and social cost curves). Certain voluntary corporate behaviors may even exceed the global SCC, especially commitments to nuclear, carbon capture, and other higher cost abatement generation financed by the largest sources of power demand growth. Well-functioning voluntary carbon markets could yield roughly one billion metric tons of domestic carbon dioxide abatement by 2030. Providing locational marginal emissions data can slash abatement costs from $19-$47/ton down to $8-$9/ton while doubling abatement levels from some power generation sources.

Overall, efficient GHG transparency policy described above is a low-cost mitigation strategy consistent with class II designation. Basic, federal GHG transparency policy may even constitute class I policy, because it avoids the higher compliance cost alternative of a patchwork of state and international standards that would manifest in the absence of federal policy. However, stringent GHG transparency policy may constitute class III or IV policy. Prominent examples include a recent California climate disclosure law and a former Securities and Exchange Commission proposed rule to require emissions disclosure related to assets a firm does not own or control (Scope 3). Such efforts may obfuscate material information on climate-related risk and worsen private-sector led emission mitigation efforts.

Direct GHG Regulation

Classic environmental regulation takes the form of a command-and-control approach. These instruments include applying emissions performance standards or technology-forcing mechanisms, typically for power plants or mobile sources. These policies vary widely in stringency and cost. Overall, command-and-control is widely considered in the economics literature to be an unnecessarily costly approach to reducing GHGs relative to market-based alternatives. It can also result in freezing innovation, by discouraging adoption of new technologies.

Federal command-and-control GHG programs have not been particularly environmentally effective, cost-effective, or demonstrated legal or political durability. The first power plant program was the Clean Power Plan, which was struck down in court, and yet its emissions target was achieved a decade early from favorable market forces and subnational climate policy. The most recent federal command-and-control approaches for GHG regulation were 2024 EPA rules for vehicles and power plants. A 2025 review of these and other federal climate regulations over the last two decades of federal climate regulations found:

- EPA’s cost estimates to be “extraordinarily conservative” with suspect methodology that was prone to error and inconsistent with economic theory;

- Assessed costs of $696 billion compared to regulators’ estimate of $171 billion, or an increase in abatement cost from $122/tonne to $487/tonne; and

- EPA is too optimistic in its assumptions of benefits.

The 2025 review study implies that past federal command-and-control had very high cost – well into class IV range. It has also been a top priority of conservatives to undercut. However, it is possible for modest command-and-control policy with class II or III costs.

Some conservatives, noting EPA’s legal obligation to regulate GHGs and the cost of regulatory uncertainty from decades of EPA policy oscillations between administrations, suggested modest requirements as a better option to replace high cost rules in order to mitigate legal risk and provide industry a predictable, low-cost compliance pathway. For example, conservatives argued that replacing high cost requirements for power plants to adopt carbon capture and storage (CCS) with low cost requirements for heat rate improvements may lower compliance costs more than attempting to repeal the Biden era rule for CCS outright. Similarly, the oil and gas industry opposed stringent GHG regulations on power plants and mobile sources, but often validated alternative low cost compliance requirements.

The first Trump administration pursued modest replace-and-repeal GHG regulation. The second Trump administration has opted for repeal policies and to eliminate the endangerment finding via executive rulemaking. However, regulated industry and many conservative thought leaders believe this is a strategic blunder, given the low odds of legal success, resulting in the perpetuation of “regulatory ping-pong that has plagued Washington, D.C., for decades.” If the courts uphold Massachusetts v. EPA and the associated endangerment finding, this implies that modest command-and-control policy may have durable political alignment potential. Yet this does not hold much abatement potential. In the absence of a legal requirement to regulate GHGs, there is unlikely to be broad political alignment for even modest command-and-control policy. Conservatives tend to view this as a gateway to more costly policies that will probably not meaningfully affect global GHG trajectories.

The 2025 review study understates the full cost of U.S. climate regulations because they exclude state and local levels. Although no comprehensive study of state climate regulation is known, command-and-control state regulations often raise major cost concerns as well. The cost and environmental performance of such state programs varies immensely, often owing to differences in the accuracy of abatement technology costs that regulatory decisions are based upon (e.g., the failure of California’s zero-emission vehicle program compared to success with its low-emission vehicle program). A recent example is California’s rail locomotive mandate, which projected to impose tens of billions of dollars in costs before being withdrawn. State command-and-control regulation is commonplace in progressive states, but not beyond, implying meager Overton Window alignment.

A more economical version of GHG regulation is a system of marketable allowances, or cap-and-trade (C&T). Over three decades of experience with C&T programs reveals two things. First, C&T is environmentally effective and economically cost effective relative to command-and-control policy. Second, C&T performance depends on its design quality and interaction with other policies. Abatement costs depend on stringency and other design features, but C&T in a backstop role is generally close to the domestic SCC, rendering it class II policy. Robust C&T generally falls in the class III policy range. C&T is an example of abatement policy that can be cost-effective on a per unit basis, but given the breadth of its coverage its total costs can be substantial. Recent developments in Pennsylvania indicate a possible preference for policies with higher per-unit abatement costs than C&T, which may reflect a political preference for policies with less cost transparency and lower aggregate costs.

Some environmental C&T complaints are valid, such as emissions leakage, but C&T effectiveness concerns are generally readily fixable design flaws. C&T effectiveness complaints are often the result of interference from other government interventions like fuel mandates, relegating C&T to a backstop role and suppressing allowance prices. Such state interventions triggered anti-competitive concerns in wholesale power markets overseen by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). This prompted conservative state electric regulators to call for a conference to validate mechanisms like C&T as a market-compatible alternative to high cost interventions. Conservative expert testimony at that conference, invited by conservative FERC leadership, explained that interventions layered on top of C&T merely reallocate emissions reduction under a binding cap, which raises costs, creates no additional abatement, and undermines innovation. This implies that such states might increase abatement and lower aggregate costs by upgrading the role of C&T and downgrading the role of costlier interventions.

In the 2000s, bipartisan interest in federal C&T policy arose, but it failed and has not resurfaced. In its absence, states have supplanted federal policy with subnational C&T programs. However, the durability of C&T beyond progressive states is unclear. Moderate states have sometimes joined a regional C&T program under Democratic leadership, but sometimes departed them under Republican leadership. Conservative state groups typically challenge C&T adoption and seek repeal of C&T programs like the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. This suggests that C&T is at the fringe, but typically outside, an Overton Window across political movements.

Permitting and Siting

Permitting policy can base decisions explicitly on GHG criteria, or they can be based on non-GHG factors but hold indirect GHG consequences. Generally, only progressive states and presidents have pursued the former. Federally, these include the Obama administration’s “coal study” and Biden administration’s “pause” on liquified natural gas (LNG). The LNG pause did not provide any apparent emissions benefit, yet carried substantial foregone economic opportunity and strategic value to U.S. allies. Pragmatic progressive thought leaders expressed concern with the pause, noting the creation of economic and security risks, and suggested lifting the pause in exchange for companies to commit to strict, third-party verified methane emissions standards. Relatedly, some conservative thought leaders have supported policy that enables voluntary participation in certified programs that provide market clarity and confidence to harness private willingness to pay for lower GHG products. This has been buttressed by support from an industry-led effort to advance a market for environmentally differentiated natural gas based on a standard, secure certification process.

Permitting constraints on clean technology supply chains can have perverse economic and emissions effects. A prime example is critical minerals, which are essential components to clean energy technologies. A net-zero emission energy transition, relative to current consumption, would increase U.S. annual mineral demand by 121% for copper, 504% for nickel, 2,007% for cobalt, and 13,267% for lithium. Market forces, unsubsidized, are poised to produce a sufficient amount of domestic copper and lithium supply to satiate a large share of domestic demand, but face undue barriers to entry that restrict production far below its potential. To meet net-zero objectives, permitting reform allowing all currently proposed projects to enter the market would lower U.S. import reliance for copper from 74% to 41%, while dropping lithium import reliance from 100% to 51%.

Expanding domestic mining no doubt carries local environmental tradeoffs. However, the U.S. has some of the most stringent and comprehensive mining safeguards in the world. Thus, foregoing development domestically is likely to push mining toward foreign countries with inferior environmental, safety, and child labor protections. It is therefore critical that domestic permitting decisions account for the unintended effects of denying permits, not merely the direct consequences of approving a project.

Permitting and siting constraints on energy infrastructure also impose major costs and foregone abatement. These entry barriers largely exist as environmental safeguards, yet almost always inhibit projects with a superior emissions profile to the legacy resources they replace. In fact, 90% of planned and in progress energy projects on the federal dashboard were clean energy related as of July 2023. In 2023, the ratio of clean energy to fossil projects requiring an environmental impact statement to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was 2:1 for the Department of Energy and nearly 4:1 for the Bureau of Land Management. A 2025 study estimated that bringing down permitting timelines from 60 months to 24 months would reduce 13% of U.S. electric power emissions.

Permitting has proven to be a litmus test for the progressive environmental movement, as the movement bifurcates between anti-development symbolists and pragmatic pro-abundance progressives. While a minority of mainstream environmental groups have become amenable to permitting reform, such as The Nature Conservancy and Audubon Society, the core of progressive environmental groups have not. Instead, new progressive groups like Clean Tomorrow and the Institute for Progress filled the pro-abundance void alongside traditional market-friendly progressive groups like the Progressive Policy Institute. This progressive subset has helped influence moderate Democrats to support permitting reform in a collaborative way with conservatives.

Permitting reform has long been championed by conservatives for its economic benefits, with climate considerations typically a secondary-at-best rationale. Yet permitting reform has become a priority for the newer climate-minded conservative movement. However, permitting has also proven to be a differentiator between conservatives and right-wing populists. The latter engages in forms of government intervention that sometimes contradict conservative principles. For example, the Trump administration enacted an offshore wind energy pause that followed the same problematic blueprint as the Biden administration’s LNG pause. This elevates the importance of technology-neutral permitting reforms with an emphasis on permitting permanence safeguards.

In recent years, a coalition of Republicans, centrist Democrats, and clean energy and abundance advocates have pressed for reform to NEPA. A broad suite of federal permitting reforms with bipartisan appeal was identified in a 2024 report by the Bipartisan Policy Center. Bipartisan alignment led to the passage of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 into law and the Senate passage of the Energy Permitting Reform Act of 2024 (EPRA). Although a 2025 Supreme Court decision suggests executive actions alone may substantially reduce NEPA obstacles, plenty of NEPA and other federal statutory reforms remain of high value and hold considerable bipartisan potential.

The positions of leading progressive, conservative, and centrist thought leadership organizations highlight alignment on various federal permitting and siting reforms. These include statutory changes to NEPA, the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act and the National Historic Preservation Act. Substantive alignment includes reforms that reduce litigation risk (e.g., judicial review reform), limit executive power to stop project approvals and undermine permitting permanence, maintain technology neutrality, strengthen federal backstop siting authority for interstate infrastructure, codify the Seven County decision, and streamline agency practices while ensuring sufficient state capacity.

Despite considerable positive momentum at the federal level, the greatest permitting and siting barriers generally reside at the state and local levels and trending sharply in a more restrictive direction. Wind and solar ordinances have grown by over 1,500% since the late 2000s. Oil and gas pipelines and power plants face mounting permitting and siting restrictions in progressive states, which not only raise costs but do not necessarily reduce emissions. In fact, the New England Independent System Operator said that a lack of natural gas infrastructure in the region has raised prices and pollution by forcing reliance on higher-cost resources like oil-fired power plants. The only major power generation resource with a less restrictive trend is nuclear, as six states recently modified or repealed nuclear moratoria to ease siting.

Motivation for opposing energy infrastructure permitting has included the well-known “not in my backyard” concerns, such as noise, construction disruptions, or land use conflicts. Interestingly, much opposition appears to come from perception, as much as substantiated negative effects. Relatedly, permitting resistance rationales increasingly appear to result from ideological opposition to particular energy sources. Finally, much opposition and most litigation of energy projects comes from non-governmental organizations, not the land owners directly affected. Altogether, this underscores the importance of permitting and siting reform that improves the quality of information to agencies and parties, ties decisionmaking to specific harms not speculative claims, limits standing to affected parties, and creates appeals processes for landowners to challenge obstructive local government laws and decisions. A key tension to overcome is that technology-agnostic legislation has been more likely to advance in states with one or more Republican chamber, yet environmental advocates resist “all-of-the-above” reforms.

Policies that reduce permitting and siting burdens are class I: they boost economic output and are increasingly key to emissions reductions. Permitting and siting policies that are restrictive on fossil development are not particularly effective at reducing emissions and often add considerable cost, granted costs vary widely depending on the nature of the policies and implementation. Effective fossil restrictions can range from class II to class IV policy, while ineffective ones actually increase emissions. The political economy of permitting and siting must overcome the lobby of entrenched suppliers, who seek to maintain competitive moats. An ironic example was incumbent asset owners funding environmental groups to oppose transmission infrastructure in the Northeast that would import emissions-free hydropower.

Electric Regulation

The power industry is at the forefront of energy cost concerns and decarbonization objectives. In the early 2020s, electric rates have risen most in Democratic states. These concerns reoriented progressives towards cost containment, even at the expense of climate objectives. In the 2024 election, cost of living concerns propelled Republicans to widespread victories as President Trump vowed to halve electricity prices. A year later, voter concerns over rising electricity rates in Georgia, New Jersey, and Virginia boosted Democrats in gubernatorial and public service commission (PSC) elections.

At the same time, electricity is arguably the most important sector for climate abatement given its emissions share and the indirect effects of electrifying other sectors, namely transportation and manufacturing. Ample pathways exist to reduce electric costs and emissions simultaneously, primarily by fixing profound government failure embedded in legacy regulation. Electric industrial organization shapes economic and climate outcomes, with market liberalization an advantage for both.

Electric regulation falls into two basic formats. The first is cost-of-service (CoS) regulation, where the role of government is to substitute for the role of competition in overseeing a monopoly utility. The alternative is for regulation to facilitate competition by using the “visible hand” of market rules to enable the “invisible hand” to go to work.

CoS regulation historically applied to power generation, though about a third of states enacted restructuring to introduce competition into power generation and retail services, in response to rising rates and the recognition that these are not natural monopoly services. Nearly all transmission and distribution (T&D) historically and today remains under CoS regulation. Importantly, CoS regulation motivates a utility to expand the regulated rate base upon which it earns a state-approved return. Generally, the main sources of cost discipline problems in the power industry stem from its CoS regulation segments: transmission, distribution, and the portion of generation that remains on CoS rates.

Generally, restructured jurisdictions see greater innovation and downward pressure on the supply portion of customer bills. The economic performance of restructuring is highly sensitive to the quality of implementation. This includes the quality of wholesale energy price formation and capacity market design. It also includes various elements of retail choice implementation. They have also seen improved governance, whereas CoS utilities are prone to cronyism and corruption given the inherent incentives of their business model. Competitive wholesale and retail power markets hold cost and emissions advantages through several mechanisms:

- Markets accelerate capital stock turnover when it is economic. With the brief exception of nuclear retirements, new entry is dominated by zero emission resources or high efficiency gas plants that displace legacy plants with higher emissions rates. Markets usher in new entry and induce retirements in response to economic conditions. Last decade saw markets outperform in the coal-to-gas transition, and this decade with advances in wind, solar, and storage economics. Texas, the most thoroughly restructured state, leads the country in solar, wind, and energy storage additions while placing second in gas additions. A review of restructuring found that competition worked as intended, facilitating new, low-cost entry while “driving inefficient, high-cost generation out of the market.” A new paper evaluating generator-level data found that from 2010–2023, regulated units were 45% less likely to retire than unregulated units.

- Markets encourage power plant operating efficiencies. Competitive generators adopt technologies and practices that use fuel more efficiently and improve environmental performance. The introduction of competition caused nuclear generators to adopt innovative practices to reduce refueling outage times, boosting operating efficiency by 10%. One study found 9% higher operating efficiencies in the thermal power fleet in restructured states. By contrast, CoS utilities sometimes engage in uneconomic operations because they are financially indifferent to market signals, resulting in overoperation of the fossil fleet.

- Markets reflect customer preferences, including clean power. Footprints with retail choice have seen much higher popularity of voluntary clean power programs. Competition lowers the “green premium” and customer choice allocates it equitably. This is critical as the willingness to pay for clean power varies enormously across customers. Notably, most growing power customers are large companies with ambitious corporate emissions reductions targets, which explains their commercial interest in advancing consumer choice.

- Markets better integrate unconventional resources, namely storage, wind, solar, and demand flexibility. The central planning of monopoly utilities struggles to account for the profile of variable (e.g., wind and solar) and use-limited (e.g., storage) resources. Demand flexibility is valuable to integrate more variable supply sources. Wholesale and retail competition are the only structural pairings that have elicited substantial shifts in demand in response to price signals, because they align the incentives of retailers and end-users to reduce consumption during high price periods.

- Markets induce lower-cost environmental compliance and better environmental lobbying behavior. Restructuring reoriented the incentives to influence and comply with public policy. Notably, competitive enterprises pursue more innovative, lower-cost compliance pathways that tend to deepen abatement. Monopoly utilities have a track record of lobbying for higher cost environmental laws. For example, monopolies have a preference for command-and-control regulation that pads their rate base, and have opposed market-based policies like the 1990 Clean Air Act amendments.

Electric cost increases are multifaceted, prompting many misdiagnoses that blame markets for non-market problems. Utilities have begun pushing campaigns in restructured states to revert back to CoS regulation, whereas the growing consumer segment – namely data centers and industrials – are organizing campaigns to expand consumer choice. Independent economic assessments warn against a return to CoS regulation, and instead encourage state regulators to implement restructuring better. This includes better market design, consumer exposure to wholesale prices, and effective coordination with transmission investment.

T&D costs, generally, are the core driver of electricity cost pressures nationwide. Over the last two decades, utility capital spending on distribution has increased 2.5 times while nearly tripling for transmission. This reflects profound flaws in CoS regulation of T&D, resulting in overinvestment in inefficient infrastructure and underinvestment in cost-effective infrastructure. This projects to worsen, given T&D expansion needed to meet grid reliability criteria as a result of aging infrastructure, turnover in the generation fleet, and load growth.

T&D expansion is also central to abatement. Even partial transmission reforms can reduce carbon dioxide emissions by hundreds of million of tons per year. This explains why progressives have made reforms that expand transmission a top priority. This needs to be reconciled with the cost concerns of consumers and conservatives to result in durable policy. Consumers and conservatives have a budding transmission agenda rooted in upgrading the existing system, removing barriers to voluntary transmission development, using sound economic practices for mandatorily planned transmission, streamlined permitting and siting, and improved governance. A particularly promising frontier is reforms to enhance the existing system, given the expedience of their cost relief and consistency with a Trump administration directive.

Recent federal regulatory actions have demonstrated bipartisan willingness to improve transmission policy and the related issue of interconnection, which has emerged as a major cost and emissions issue. In 2023, FERC passed Order 2023 on a bipartisan basis to reduce barriers to new power plants trying to interconnect to regional transmission systems. Subsequent reforms were motivated by a coalition of consumer groups and the center-right R Street Institute. In 2024, FERC passed Order 1920-A on a bipartisan basis to improve economic practices in regional transmission development. EPRA, a gamechanger for interregional transmission development, passed the Senate with bipartisan support in 2024.

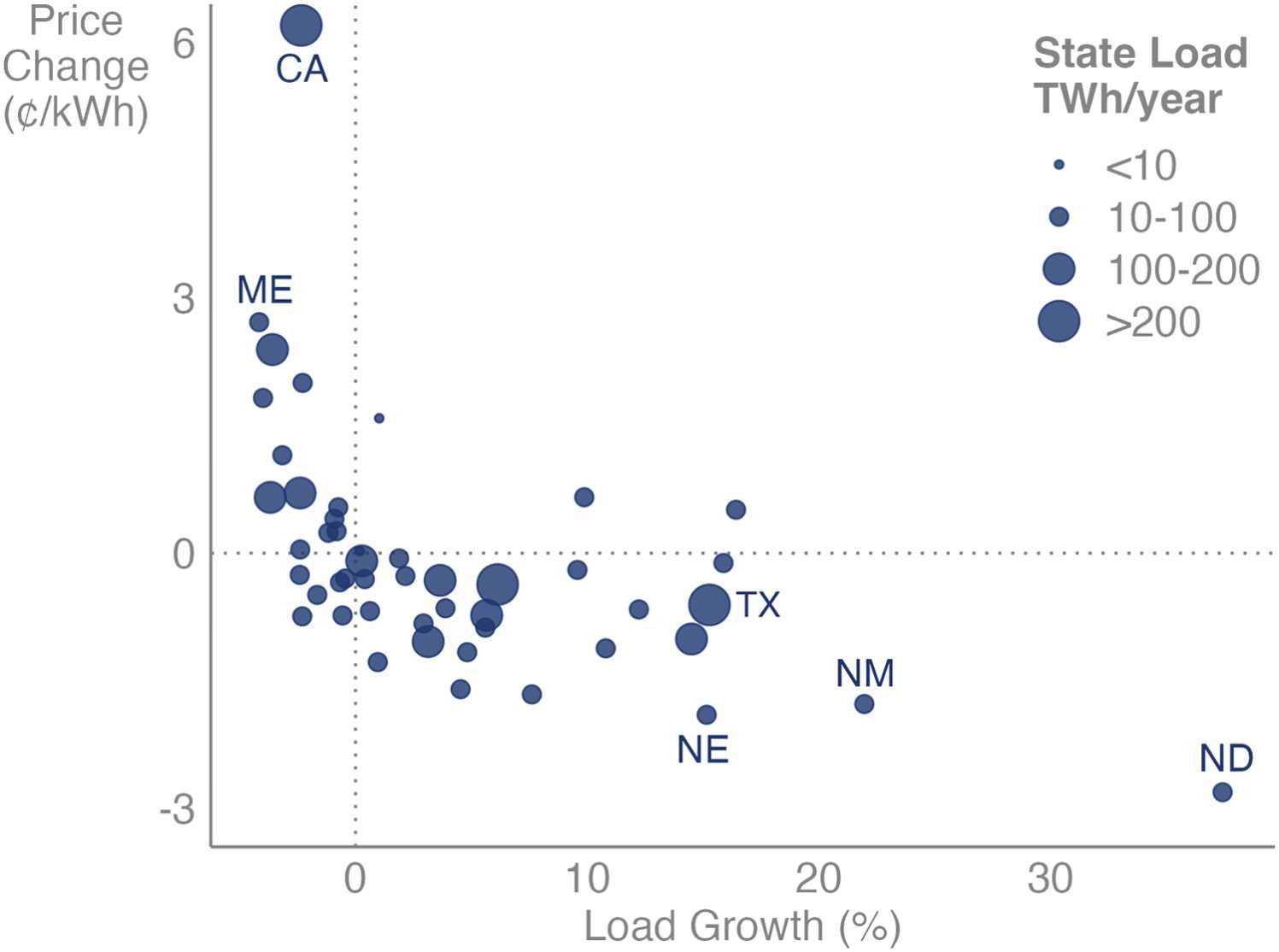

Demand growth has sparked reliability concerns over tight supply margins and recently put upward pressure on wholesale market prices. However, states with the greatest price decreases typically had increasing demand from 2019 to 2024 (Figure 3). This shows the importance of infrastructure utilization on electric rate pressures, as many areas had supply slack previously. The past may not be prologue. Emerging conditions show supply-constrained scenarios where marginal generation and T&D costs increase steeply to meet new load increase. The Energy Information Administration observes steady retail price increases and projects further rises to exceed inflation.

Source: Wiser et al., 2025.

In an era of resurgent power demand growth, the states poised to keep rates and emissions down have wholesale competition, retail competition, efficient generator interconnection processes, economical T&D practices, and low permitting and siting barriers. The only state that reasonably accomplishes all of these is Texas, which is experiencing the most commercial interest among competitive suppliers and growing power consumers. Texas has experienced industry-leading clean energy investment and earned the distinction of Newsweek’s “greenest state” in 2024.

All aforementioned electric reforms are considered class I policy. Despite cost-reduction appeal, power industry reforms have proven challenging for two reasons. First, reforms are highly technical in nature and face limited state capacity among legislative advisors and technocratic agencies, namely PSCs and FERC. For example, recent FERC and PSC activities reveal that these entities do not have the bandwidth or expertise to properly implement existing transmission policy, much less reform it. Secondly, reforms face strong resistance from incumbent utilities who hold concentrated interests in the status quo, creating a strong lobbying incentive. By contrast, the beneficiaries of reform, especially consumers, are dispersed interests that do not organize as effectively as a lobbying force.

Although the Texas electricity experiment and associated federal power market reforms under President George W. Bush is a conservative legacy, most restructured states are progressive. This reflects significant bipartisan historic appeal. However, traditional conservatives have sometimes conflated pro-utility positions as the “pro-business” position, while it is unclear whether right-wing populist influences will catalyze pro-market reforms by challenging the status quo or retrench monopoly utility interests based on technocratic market skepticism (e.g., Project 2025). CoS utilities also commonly oppose cost-effective T&D reform, especially vertically-integrated utilities, which is consistent with their financial incentives to expand rate base and deter lower-cost imports from third parties. Nonetheless, the political economy of bipartisan electric regulatory reform remains promising, given voters’ prioritization of reducing electricity costs.

Public Spending

Government spending occurs through direct spending outlays or indirect spending through tax expenditures. Spending takes the form of industrial policy or innovation policy. The economics literature is historically critical of industrial policy, while positive literature on industrial policy usually conflates it with innovation policy. A distinguishing element is that innovation policy selects policy instruments suited to specific market failures, namely the positive externalities of knowledge spillovers and learning-by-doing. These generally apply to research and development (R&D) and early stage technologies, including those in demonstration stage and infant industries that have not achieved economies of scale.

Predictably, progressives have been consistent backers of robust innovation policy, while conservatives typically scrutinize such expenses closely. Although differences of opinion exist on optimal funding levels, historically conservatives and progressives have agreed on a role for the government in supporting R&D. There is also a history of good governance agreement, such as a joint project between the Center for American Progress and the Heritage Foundation in 2013 on improving the performance of the national lab system. Improving outcomes-based Department of Energy program performance may have broad appeal, including better performance metrics, stronger linkages to private sector needs, and program reevaluation to determine government investment phase-out. Improvements to state capacity are paramount in this regard.

Conservatives are often critical of public spending on infant industry, where government failure can outweigh market failure. For example, policymakers often struggle to identify when to end industry support, while industry engages in rent-maintenance behavior even after it has achieved maturity. Historic evidence indicates that direct subsidies and tax exemptions for infant energy industry continue well after the targeted technologies mature. Conservative and progressive scholars have historically framed the merits over subsidies for infant industry as a debate over government versus market failure.

Since innovation policy targets non-climate market failures (e.g., knowledge spillovers) it may have a high static abatement cost. However, it is an inexpensive abatement policy when accounting for dynamic effects, because of induced innovation and learning-by-doing. Importantly, innovation policy holds massive climate benefits, because achieving abatement cost parity between clean and emitting resources is central to clean technology market adoption. Efficient R&D policy can be classified as class I policy, because the upfront cost of the policy is outweighed by long-term cost savings. Demonstration and infant industry support falls into class II-III range, depending on its implementation, and often exhibits substantial durability.

In recent years, climate-minded conservatives have shown stronger inclinations of public spending for innovation policy. However, there is a stark difference between conservatives and right-wing populism on innovation policy. Conservatives note that the adverse consequences of Department of Government Efficiency’s “gutted, ineffective government” approach to the Department of Energy is inconsistent with limited, effective government practice. The economic self-interest benefits of innovation policy may induce a course-correction with MAGA, which has not deliberately targeted innovation policy insomuch as sacrificing it amid a rash government downsizing exercise.

In contrast to innovation policy, industrial policy aims to directly promote a given industry, typically using mature technology, with interventions untethered to any underlying market failure (e.g., negative emissions externality). This generally takes the form of public spending on mature industries. For decades, traditional conservatives and climate-minded conservative scholars have been critical of green industrial policy for carrying high costs with modest emissions reductions.

The most relevant case study in climate industrial policy versus innovation policy is the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022. IRA represented the “largest federal response to climate change to date.” It consisted mostly of subsidies for mature technologies, especially wind, solar, and electric vehicles (EVs). It also contained subsidies for infant industry. IRA was passed exclusively by Democrats, with Republicans voicing concerns over its cost. Republicans then passed the One Big Beautiful Big Act (OBBBA) in 2025, which phased-out subsidies for mature technologies, but generally retained those for infant industry. This underscores the political durability of innovation policy and the fragility of industrial policy.

A broader debrief on IRA and OBBBA reveals:

- Disregard for cost considerations preceded passage of the IRA. All known ex ante modeling of IRA’s abatement benefits before it passed ignored costs. This left Congress unequipped to weigh the merits and tradeoffs of the policy. A simplistic abatement cost technique in 2022 yielded a cost of $72/tonne for the renewable energy subsidies. A more sophisticated modeling exercise in 2023 projected an average abatement cost of $83/tonne. IRA could have been identified as a high abatement cost policy (class IV) before it passed. Before passage, R Street Institute analysis suggested meager additionality from subsidies and identified permitting and electric regulation flaws as the determining factors of energy emissions trajectories, yet Congress neglected those reforms.

- IRA abatement cost estimates escalated sharply after passage. The total abatement cost of IRA subsidies to taxpayers rose from $336/tonne in 2024 to $600/tonne in 2025. The initial 2022 IRA renewables subsidy cost estimate of $72/tonne rose to $142/tonne in 2024 and $208/tonne in 2025. The EV subsidy came in at $1,626/tonne. It is possible that this is understated, since the direction of the emissions effect of EV subsidies may depend on recipient qualifications, especially when accounting for the behavioral tendencies of EV adopters. The subsidies also undermined developer cost reduction in two ways: 1) motivated development in the least efficient areas and 2) weakened incentives for innovation that lowers costs, which translates into long-term cost increases relative to an unsubsidized baseline.

- Government failure precluded most of the anticipated climate benefits of the IRA. IRA abatement was overstated in 2022, because models understated artificial constraints on the core abatement driver: wind and solar deployment. The Energy Information Administration’s renewables projections in 2025, which reflected IRA subsidies, were close to their no-IRA estimates from 2022. Risk, not cost, has consistently been the barrier to wind and solar. A Brookings Institution analysis found that artificial barriers to entry were the leading causes of wind and solar project cancellations from 2016-2023, whereas the lowest cause was “lack of funding.” Renewables subsidies primarily constituted a wealth transfer from taxpayers to suppliers. One analysis suggested 80-90 percent of clean energy backed by the IRA would have occurred anyways. An S&P Global forecast projected OBBBA to cause a 15 percent decline in wind, solar, and battery storage capacity by 2035.

- Wind, solar, and EV tax credit phaseouts should lower costs and increase economic productivity, despite increasing electricity prices. Price and cost are related, but not the same thing. The phase-out of subsidies under OBBBA will put upward pressure on electricity prices. However, it will likely lower costs by restoring dynamic cost management incentives and removing distortions so investment reflects economic fundamentals. Electricity subsidies shift cost burdens from power generators and ratepayers to taxpayers. Because taxpayer funding is expensive – tax collection imposes considerable deadweight loss on the economy – the net effect of taxpayer subsidies tends to shrink economic output. The Tax Foundation projected that IRA would reduce U.S. gross domestic product by 0.2 percent, while OBBBA would increase long-run GDP by 1.2 percent, granted energy tax credits were only one factor in these analyses.

The takeaway from IRA and OBBBA is that subsidies for mature technologies are high cost, likely to erode social welfare, and not politically durable. Efficient public spending for RD&D, however, enhances social welfare and falls in the Overton Window due to its value for economic self-interest. Late-stage infant industry is at the fringe of the Overton Window. It is the area where conservative and progressive scholars have historically had contrasting views on whether market failure outweighs government failure, yet political outcomes have largely supported infant industry.

Generally, the literature finds strong evidence of opportunity cost neglect in public policy, which “creates artificially high demand for public spending.” The IRA was a case-in-point. Meanwhile, the opportunity cost of public spending is rapidly rising given the dire fiscal trajectory of the United States. In 2025, moderate experts emphasized a pivot away from unsustainable and ineffective “Green New Deal thinking” for clean technology subsidies in favor of an innovation-driven strategy.

Takeaways

This analysis finds chronic flaws of cost considerations in ex ante policy analysis. Many medium and high-cost policies have passed without any robust accounting of costs at all (e.g., IRA, fuel bans). Interventions with cost-benefit analysis have had a tendency to underestimate costs (e.g., regulation). These flaws contribute to public misconception and play into political economy dynamics that tend to incent policies with hidden costs over those with transparent ones.

High-cost policies have typically only been enacted by progressive governments and have come under greater scrutiny as energy costs escalate. This calls their social welfare effects and durability into question. It has cast climate action in the public eye as requiring deep economic sacrifice.

Conservatives have been hesitant to engage on climate policy outright, largely over dire economic tradeoff perceptions. Such concerns have instigated a conservative backlash to climate policy, including to policies that are compatible with U.S. economic interests. This has been exacerbated by right-wing populism, which often strays from limited government conservatism in pursuit of cultural identity objectives. For example, in a 2024 piece promoting energy affordability, the Heritage Foundation correctly attributed cost increases to renewable energy mandates, but incorrectly presumed that a broad shift towards renewable energy and away from fossil fuels would always increase costs.

High abatement cost policies not only risk reducing aggregate social welfare, but they create distributional concerns. Policies that raise energy costs tend to be regressive. This has challenged the social justice narrative of progressives, prompting a rethink by progressive leaders to take a “cost-first approach to [the] clean energy transition.” Although subsidies are a common response to lower burdens on low-income households, the most popular green subsidies pursued have exacerbated distributional concerns. Specifically, renewables subsidies favored by progressives have been challenged by conservatives as “green corporate welfare.” Progressives have also faced criticism for EV tax credits for disproportionately benefiting wealthy households.

Encouragingly, negative- and low-cost policies comprise a rising share of the abatement curve. The Overton Window for pursuing such policies has grown remarkably for “abundance progressives” and conventional conservatives. However, populist subsets within both movements challenge the potential for political alignment. Enacting negative-cost policies also faces the collection active problem of dispersed beneficiaries versus a concentrated incumbent supplier lobby favoring the status quo. Mobilizing consumer and taxpayer groups is an underappreciated strategy to enact these policies.

This analysis is far from comprehensive. A notable omission from this paper is transportation policy, the largest GHG sector in the U.S. A scan of the transportation literature underscores major abatement potential for negative and low-cost policies, including reducing government barriers to efficient heavy-duty transportation like railways, shipping, and heavier trucking. Further, the electrification of transportation requires extensive fixes to government failure, such as liberalizing markets to enable competitive charging infrastructure, which lowers costs. The merits of innovation and GHG transparency policy, previously discussed, also appear to hold promise for transportation applications such as aviation fuel. The transportation sector has also been the target of GHG regulation, mostly in progressive states, which warrants close assessment of costs. For example, one study identified a vast abatement cost range for fuel standards ($60-$2,272/tonne).

A shortcoming of this analysis is that it only characterizes costs by their efficiency (i.e., $/ton). Political decisions are highly sensitive to aggregate cost and its visibility to the public, which our taxonomy does not characterize. It is possible that efficient, transparent, and higher aggregate cost policies (e.g., C&T) fare less favorably in some political settings than inefficient, opaque, and sometimes lower aggregate cost policies (e.g., RPS solar carveouts).

Despite the limitations of this analysis, the sample of policies evaluated is sufficient to support the thesis. That is, a retooled climate policy agenda that prioritizes cost considerations should elevate social welfare and achieve greater abatement by selecting more durable policies.

Conclusion

Abatement costs have huge bearing on whether climate policies benefit society, their likelihood of passage, and whether they prove politically durable. Most abatement need not come from dedicated climate policy, per se, but rather sound economic policy that carries deep climate co-benefits. Chronic disregard for cost considerations has led to an overselection of high-cost policies and underpursuit of low- and negative-cost policies. This has undermined policy durability and exacerbated political polarization over climate change abatement.

This paper finds extensive abatement opportunities within negative-cost policies. These largely constitute fixes to government failure and include permitting, siting, and power regulation reforms. This analysis also finds considerable low-cost policies that are compatible with U.S. economic self-interests. These policies primarily spur voluntary private sector abatement through efficient innovation policy and GHG transparency.

We offer three sets of recommendations moving forward for influencers of the climate policy agenda:

- Focus on results. Climate change abatement is a function of global GHG concentrations. Too much attention pursues symbolic objectives, like preventing fossil fuel infrastructure. This tends to undermine abatement goals and impose high costs.

- Emphasize cost considerations in policy agenda setting, formulation, and maintenance. Negative abatement cost policies should take top priority, with an emphasis on mobilizing beneficiaries. Robust cost-benefit analyses should precede all cost-additive policies and be reconducted periodically to guide policy adjustments.

- Prioritize quality state capacity. The net benefits of abatement policies are sensitive to government capacity and performance. Public management is in great jeopardy in an era of institutional decay. Negative-cost policies are often highly technocratic and require sufficient staffing expertise and accountable management at public institutions like DOE, FERC, PSCs, and permitting and siting agencies.

In an era of energy affordability precedence, a reset climate agenda should anchor itself in good policy basics. That is, a sober-minded return to results-driven, net-benefits prioritized policy. This should improve the durability of climate policy and ensure it enhances social welfare. Executing reforms well requires a recommitment to improving the quality of institutions as much as the policy itself.

Our environmental system was built for 1970s-era pollution control, but today it needs stable, integrated, multi-level governance that can make tradeoffs, share and use evidence, and deliver infrastructure while demonstrating that improved trust and participation are essential to future progress.

Durable and legitimate climate action requires a government capable of clearly weighting, explaining, and managing cost tradeoffs to the widest away of audiences, which in turn requires strong technocratic competency.

The American administrative state, since its modern creation out of the New Deal and the post-WWII order, has proven that it can do great things. But it needs some reinvention first.

Remaining globally competitive on critical clean technologies requires far more than pointing out that individual electric cars and rooftop solar panels might produce consumer savings.