Fixing Impact: How Fixed Prices Can Scale Results-Based Procurement at USAID

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) currently uses Cost-Plus-Fixed-Fee (CPFF) as its de facto default funding and contracting model. Unfortunately, this model prioritizes administrative compliance over performance, hindering USAID’s development goals and U.S. efforts to counter renewed Great Power competition with Russia, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and other competitors. The U.S. foreign aid system is losing strategic influence as developing nations turn to faster and more flexible (albeit riskier) options offered by geopolitical competitors like the PRC.

To respond and maintain U.S. global leadership, USAID should transition to heavily favor a Fixed-Price model – tying payments to specific, measurable objectives rather than incurred costs – to enhance the United States’ ability to compete globally and deliver impact at scale. Moreover, USAID should require written justifications for not choosing a Fixed-Price model, shifting the burden of proof. (We will use “Fixed-Price” to refer to both Firm Fixed Price Contracts and Fixed Amount Award Grants, wherein payments are linked to results or deliverables.)

This shock to the system would encourage broader adoption of Fixed-Price models, reducing administrative burdens, incentivizing implementers (of contracts, cooperative agreements, and grants) to focus on outcomes, and streamlining outdated and inefficient procurement processes. The USAID Bureau for Management’s Office of Acquisition and Assistance (OAA) should lead this transition by developing a framework for greater use of Firm Fixed Price (FFP) contracts and Fixed Amount Award (FAA) grants, establishing criteria for defining milestones and outcomes, retraining staff, and providing continuous support. With strong support from USAID leadership, this shift will reduce administrative burdens within USAID and improve competitiveness by expanding USAID’s partner base and making it easier for smaller organizations to collaborate.

Challenge and Opportunity

Challenge

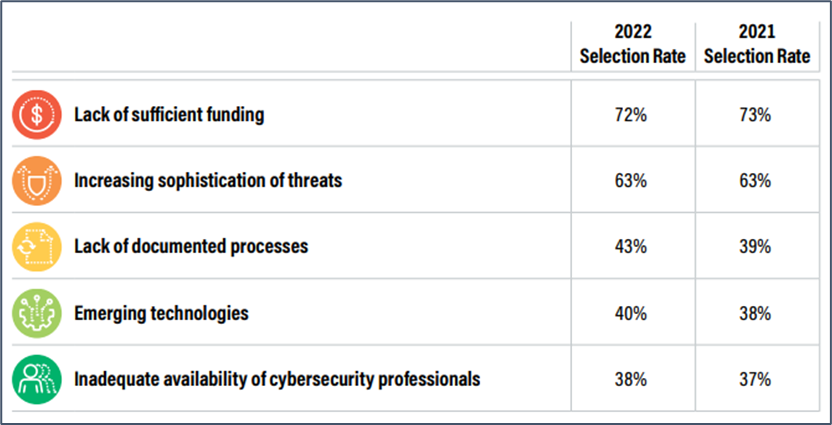

The U.S. remains the largest donor of foreign assistance around the world, accounting for 29% of total official development assistance from major donor governments in 2023. Its foreign aid programs have paid dividends over the years in American jobs and economic growth, as well as an unprecedented and unrivaled network of alliances and trading partners. Today, however, USAID has become mired once again in procurement inefficiencies, reversing previous trends and efforts at reform and blocking – for years – sensible initiatives such as third country national (TCN) warrants, thereby reducing the impact of foreign aid for those it intends to help and impeding the U.S. Government’s (USG) ability to respond to growing Great Power Competition.

Foreign aid serves as a critical instrument of foreign policy influence, shaping geopolitical landscapes and advancing national interests on the global stage. No actor has demonstrated this more clearly than the PRC, whose rise as a major player in global development adds pressure on the U.S. to maintain its leadership. Notably, China has increased its spending of foreign assistance for economic development by 525% in the last 15 years. Through the Belt & Road Initiative, its Digital Silk Road, alternative development banks, and increasingly sophisticated methods of wielding its soft power, the PRC has built a compelling and attractive foreign assistance model which offers quick, low-cost solutions without the governance “strings” attached to U.S. aid. While it seems to fulfill countries’ needs efficiently, hidden costs include long-term debt, high lifecycle expenses, and potential Chinese ownership upon default.

By contrast, USAID’s Cost-Plus-Fixed-Fee (CPFF) foreign assistance model – in which implementers are guaranteed to recover their costs and earn a profit – mainly prioritizes tracking receipts over achieving results and therefore often fails to achieve intended outcomes, with billions spent on programs that lack measurable impact or fail to meet goals. Implementers are paid for budget compliance, regardless of results, placing all performance risk on the government.

The USG invented CPFF to establish fair prices where no markets existed. However, its use has now extended far beyond this purpose – including for products and services with well-established commercial markets. The compliance infrastructure necessary to administer USAID awards and adhere to the documentation/reporting requirements favors entrenched contractors – as noted by USAID Administrator Samantha Power – stifles innovation, and keeps prices high, thereby encumbering America’s ability to agilely work with local partners and respond to changing conditions. (Note: USAID typically uses “award” to refer to contracts, cooperative agreements, and grants. We use “award” in this same manner to refer to all three procurement mechanisms. We use “Fixed-Price Awards” to refer to fixed-price grants and contracts. “Fixed Amount Awards,” however, specifically refers to a fixed-price grant.)

In light of the growing Great Power Competition with China and Russia – and threats by those who wish to undermine the US-led liberal international order – as well as the possibility of further global shocks like COVID-19 or the war in Ukraine, USAID must consider whether its current toolset can maintain a position of strategic strength in global development. Furthermore, amid declining Official Development Assistance (ODA) – 2% year-over-year – and a global failure to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it is critical for USAID to reconcile the gap between its funding and lack of results. Without change, USAID funding will largely continue to fall short of objectives. The time is now for USAID to act.

Opportunity

While USAID cannot have a de jure default procurement mechanism, CPFF has become the de facto default procurement mechanism, but it does not have to be. USAID has other mechanisms to deploy funding at its disposal. In fact, at least two alternative award and contract pricing models exist:

- Time and materials (T&M): The implementer proposes a set of fully loaded (i.e., inclusive of salary, benefits, overhead, plus profit) hourly rates for different labor categories and the USG pays for time incurred – not results delivered.

- Fixed-Price (Firm Fixed Price, FFP, for contracts, or Fixed Amount Award, FAA/Fixed Obligation Grants, FOG, for grants): The implementer proposes a set fee and is paid for milestones or results (not receipts).

While CPFF simply reimburses providers for costs plus profit, the Fixed-Price alternatives tie funding to achieving milestones, promoting efficiency and accountability. The Code of Federal Regulations (§ 200.1) permits using Fixed-Price mechanisms whenever pricing data can establish a reasonable estimate of implementation costs.

USAID has acknowledged the need to adapt funding mechanisms to better support local and impact-driven organizations and enhance cost-effectiveness. USAID has already started supporting these goals by incorporating evidence-based approaches and transitioning to models that emphasize cost-effectiveness and impact. As an example, in the Biden administration, USAID’s Office of the Chief Economist (OCE) issued the Promoting Impact and Learning with Cost-Effectiveness Evidence (PILCEE) award, which aims to enhance USAID’s programmatic effectiveness by promoting the use of cost-effectiveness evidence in strategic planning, policy-making, activity design, and implementation. Progress, though, remains limited. Funding disbursed based on performance milestones has remained unchanged since Fiscal Year (FY) 2016. In FY 2022, Fixed Amount Awards represented only 12.4% of new awards, or 1.4% by value.

An October 2020 Stanford Social Innovation Review article by two USAID officials argued that the Agency could enhance its use of Fixed Amount Awards by promoting “performance over compliance”. Other organizations have already begun to make this shift: the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) and The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria – among others – have invested in increasing results-based approaches and embedding different results-based instruments into their procurement processes for increased aid effectiveness.

To shift USAID into an Agency that invests in impact at scale, we propose going one step further, and making Fixed-Price awards the de facto default procurement mechanism across USAID by requiring procurement officials to provide written justification for choosing CPFF.

This would build on the work completed during the first Trump administration under Administrator Mark Green, including the creation of the first Acquisition and Assistance Strategy, designed to “empower and equip [USAID] partners and staff to produce results-driven solutions” by, inter alia, “increasing usage of awards that pay for results, as opposed to presumptively reimbursing for costs”, and the promotion of the Pay-for-Results approach to development.

Such a change would unlock benefits for both the USG and for global development, including:

- Better alignment of risk and reward by ensuring implementers are paid only when they deliver on pre-agreed milestones. The risk of not achieving impact would no longer be solely borne by the USG, and implementers would be highly incentivized to achieve results.

- Promotion of a results-driven culture by shifting focus from administrative oversight to actual outcomes. By agreeing to milestones at the start of an award, USAID would give implementers flexibility to achieve results and adapt more nimbly to changing circumstances and place the focus on performing and reporting results, rather than administrative reporting.

- Diversification of USAID’s partner base by reducing the administrative burden associated with being a USAID implementer. This would allow the Agency to leverage the unique strengths, contextual knowledge, and innovative approaches of a diverse set of development actors. By allowing the Agency to work more nimbly with small businesses and local actors on shared priorities, it would further enhance its ability to counter current Great Power Competition with China and Russia.

- Incentivization of cost efficiency, motivating implementers to reduce expenses if they want to increase their profits, without extra cost to the USG.

- Facilitation of greater progress by USAID and the USG toward the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in ways likely to attract more meaningful and substantive private sector partnerships and leverage scarce USG resources.

Plan of Action

Making Fixed-Price the de facto default option for both grants and contracts would provide the U.S. foreign aid procurement process a necessary shock to the system. The success of such a large institutional shift will require effective change management; therefore, it should be accompanied with the necessary training and support for implementing staff. This would entail, inter alia, establishing a dedicated team within OAA specialized in the design and implementation of FFPs and FAAs; and changing the culture of USAID procurement by supporting both contracting and programming staff with a robust change management program, including training and strong messaging from USAID leadership and education for Congressional appropriators.

Recommendation 1. Making Fixed-Price the de facto “default” option for both grants and contracts, and tying payments to results.

Fixed-Price as the default option for both grants and contracts would come at a low additional cost to USAID (assuming staff are able to be redistributed). The Agency’s Senior Procurement Executive, Chief Acquisition Officer (CAO), and Director for OAA should first convene a design working group composed of representatives from program offices, technical offices, OAA, and the General Counsel’s office tasked with reviewing government spending by category to identify sectors exempt from the “Fixed-Price default” mandate, namely for work that lacks deep commercial markets (e.g., humanitarian assistance or disaster relief). This working group would then propose a phased approach for adopting Fixed-Price as the default option across these sectors. After making its recommendations, the working group would be disbanded and a more permanent dedicated team would carry this effort forward (see Recommendation 2).

Once reset, Contract and Agreement Officers would justify any exceptions (i.e., the choice of T&M or CPFF) in an explanatory memo. The CAO could delegate authority to supervising Contracting Officers or other acquisition officials to approve these exceptions. To ensure that the benefits of Fixed-Price results-based contracting reach all levels of awardees, this requirement should become a flow-down clause in all prime awards. This will require additional training for the prime award recipient’s own overseers.

Recommendation 2. Establishing a dedicated team within USAID’s OAA, or the equivalent office in the next administration, specialized in the design and implementation of FFPs and FAAs.

To facilitate a smooth transition, USAID should create a dedicated team within OAA specialized in designing and implementing FFPs and FAAs using existing funds and personnel. This team would have expertise in the choices involved in designing Fixed-Price agreements: results metrics and targets, pricing for results, and optimizing payment structures to incentivize results.

They would have the mandate and resources necessary to support expanding the use of and the amount of funding flowing through high-quality FFPs and FAAs. They would jumpstart the process and support Acquisition and Program Officers by developing guidelines and procedures for Fixed-Price models (along with sector-specific recommendations), overseeing their design and implementation, and evaluating effectiveness. As USAID will learn along the way about how to best implement the Fixed-Price model across sectors, this team will also need to capture lessons learned from the initial experiences to lower the costs and increase the confidence of Acquisition and Assistance Officers using this model going forward.

Recommendation 3. Launching a robust change management program to support USAID acquisition, assistance, program, and legislative and public affairs staff in making the shift to Fixed-Price grant and contract management.

Successfully embedding Fixed-Price as the default option will entail a culture shift within USAID, requiring a multi-faceted approach. This will include the retraining of Contracts and Agreements Officers and their Representatives – who have internalized a culture of administrative compliance and been evaluated primarily on their extensive administrative oversight skills – and promoting a reorganization of the culture of Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) and Collaboration, Learning and Adaptation (CLA) to prioritize results over reporting. Setting contracting and agreements staff up for success requires capacity building in the form of training, toolkits, and guidelines on how to implement Fixed-Price models across USAID’s diverse sectors. Other USG agencies make greater use of Fixed-Price awards, and alternative training for both government and prime contractor overseers exists. OAA’s Professional Development and Training unit should adapt existing training from these other agencies, specifically ensuring it addresses how to align payments with results.

Furthermore, the broader change management program should seek to create the appropriate internal incentive structure at the Agency for Acquisition and Assistance staff, motivating and engaging them in this significant restructuring of foreign aid. To succeed at this, the mandate for change needs to come from the top, reassuring staff that the Fixed-Price model does not expose individuals, the Agency, or implementers to undue legal or financial liability.

While this change will not require a Congressional Notification, the Office of Legislative & Public Affairs (LPA) should join this effort early on, including as part of the design working group. LPA would also play a guiding role in both internal and external communications, especially in educating members of Congress and their staffs on the importance and value of this change to improve USAID effectiveness and return on taxpayer dollars. Entrenched players with significant investments in existing CPFF systems will resist this effort, including with political lobbying; LPA will play an important role informing Congress and the public.

Conclusion

USAID’s current reliance on CPFF has proven inadequate in driving impact and must evolve to meet the challenges of global development and Great Power Competition. To create more agile, efficient, and results-driven foreign assistance, the Agency should adopt Fixed-Price as the de facto default model for disbursing funds, prioritizing results over administrative reporting. By embracing a results-based model, USAID will enhance its ability to respond to global shocks and geopolitical shifts, better positioning the U.S. to maintain strategic influence and achieve its foreign policy and development objectives while fostering greater accountability and effectiveness in its foreign aid programs. Implementing these changes will require a robust change management program, which would include creating a dedicated team within OAA, retraining staff and creating incentives for them to take on the change, ongoing guidance throughout the award process, and education and communication with Congress, implementing partners, and the public. This transformation is essential to ensure that U.S. foreign aid continues to play a critical role in advancing national interests and addressing global development challenges.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

The revisions to the Code of Federal Regulations, specifically the Uniform Guidance (2 CFR 200) provision, represent an exciting opportunity for USAID and its partners. These changes, which took effect on October 1, 2024, align with the Office of Management & Budget’s vision for enhanced oversight, transparency, and management of USAID’s foreign assistance. This update opens the door to several significant improvements in key reform areas: simplified requirements for federal assistance; reduced burdens on staff and implementing partners; and the introduction of new tools to support USAID’s localization efforts. The updated regulations will reduce the need for exception requests to OMB, speeding up timelines between planning and budget execution. This regulatory update presents a valuable opportunity for USAID to streamline its aid practices, pave the way for the adoption of the Fixed-Price model, and create a performance-driven culture at USAID. For these changes to come into full effect, USAID will need to ensure the necessary flow-down and enforcement of them through accompanying policies, guidance, and training. USAID will also need to ensure that these changes flow down and are incorporated into both prime and sub-awards.

Wider adoption of Fixed-Price could expand USAID’s pool of qualified local partners, enhancing engagement with diverse implementers and facilitating more sustainable, locally-driven development outcomes. Fixed-Price grants and contracts disburse payments based on achieving pre-agreed milestones rather than on incurred costs, reducing the administrative burden of compliance. This simplified approach enables local organizations –many of which often lack the capacity to manage complex cost-tracking requirements –to be more competitive for USAID programs and to be better prepared to manage USAID awards. By linking payments to results rather than detailed expense documentation, the Fixed-Price model gives local organizations greater flexibility and autonomy in achieving their objectives, empowering them to leverage their contextual knowledge and innovative approaches more effectively. This results in a partnership where local actors can operate independently and adapt quickly to changing circumstances, without the bureaucratic burdens traditionally associated with USAID funding.

In the same way that Fixed-Price could help USAID diversify its partner base and increase localization, it could also help expand the Agency’s pool of qualified small businesses, enhancing engagement with diverse implementers, and facilitating more sustainable development outcomes while achieving its Congressionally mandated small and disadvantaged business utilization goals. The current extensive use of CPFF favors entrenched implementers who have already paid for the expensive administrative compliance systems it requires. Fixed-Price grants and contracts have fewer administrative burdens enabling new small businesses–many of which often lack the administrative infrastructure necessary to manage complex cost-tracking requirements–to be more competitive for USAID programs and to be better prepared to manage USAID awards.

USAID’s research and development arm, Development Innovation Ventures (DIV), uses fixed-fee awards almost exclusively to fund innovative implementers. Yet proven interventions rarely transition from DIV into mainstream USAID programs. Innovators and impact-first organizations find themselves well suited for USAID’s R&D, but with no path forward due to the use of CPFF at scale.

USAID has historically relied on expensive procedures to ensure implementers are using funding in ways that align with USG policies and procedures. These concerns are reduced, however, when the government pays for outcomes (rather than tracking receipts). For example, the government would no longer need to verify whether the implementer has the proper accounting and reporting systems in place, nor would the government need to spend time negotiating indirect rates nor implementing incurred cost audits. As detailed regulations on the permissibility of specific costs under federal acquisition and assistance don’t apply to Fixed-Price awards and contracts, neither the government nor the implementer needs to spend time examining the allowability of costs. Furthermore, we expect wider use of Fixed-Price models to lead to significantly improved results per dollar spent. This means that, although there would be initial costs associated with strategy implementation, we would expect Fixed-Price to be significantly more cost-effective.

Yes, USAID has made recent efforts to provide more effective aid by incorporating evidence-based approaches and transitioning to models that emphasize cost-effectiveness and impact. In order to do this, during the last Trump administration, USAID elevated the Office of the Chief Economist (OCE) by enlarging its size and mandate. The OCE issued the activity Promoting Impact and Learning with Cost-Effectiveness Evidence (PILCEE), which aims to enhance USAID’s programmatic effectiveness by promoting the use of cost-effectiveness evidence in strategic planning, policy-making, activity design, and implementation. Our approach of establishing a team within OAA would draw on lessons learned from the OCE approach while reducing any associated costs by not establishing an entirely new operating unit.

Building Regional Cyber Coalitions: Reimagining CISA’s JCDC to Empower Mission-Focused Cyber Professionals Across the Nation

State, local, tribal, and territorial governments along with Critical Infrastructure Owners (SLTT/CIs) face escalating cyber threats but struggle with limited cybersecurity staff and complex technology management. Relying heavily on private-sector support, they are hindered by the private sector’s lack of deep understanding of SLTT/CI operational environments. This gap leaves SLTT/CIs vulnerable and underprepared for emerging threats all while these practitioners on the private sector side end up underleveraged.

To address this, CISA should expand the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative (JCDC) to allow broader participation by practitioners in the private sector who serve public sector clients, regardless of the size or current affiliation of their company, provided they can pass a background check, verify their employment, and demonstrate their role in supporting SLTT governments or critical infrastructure sectors.

Challenge and Opportunity

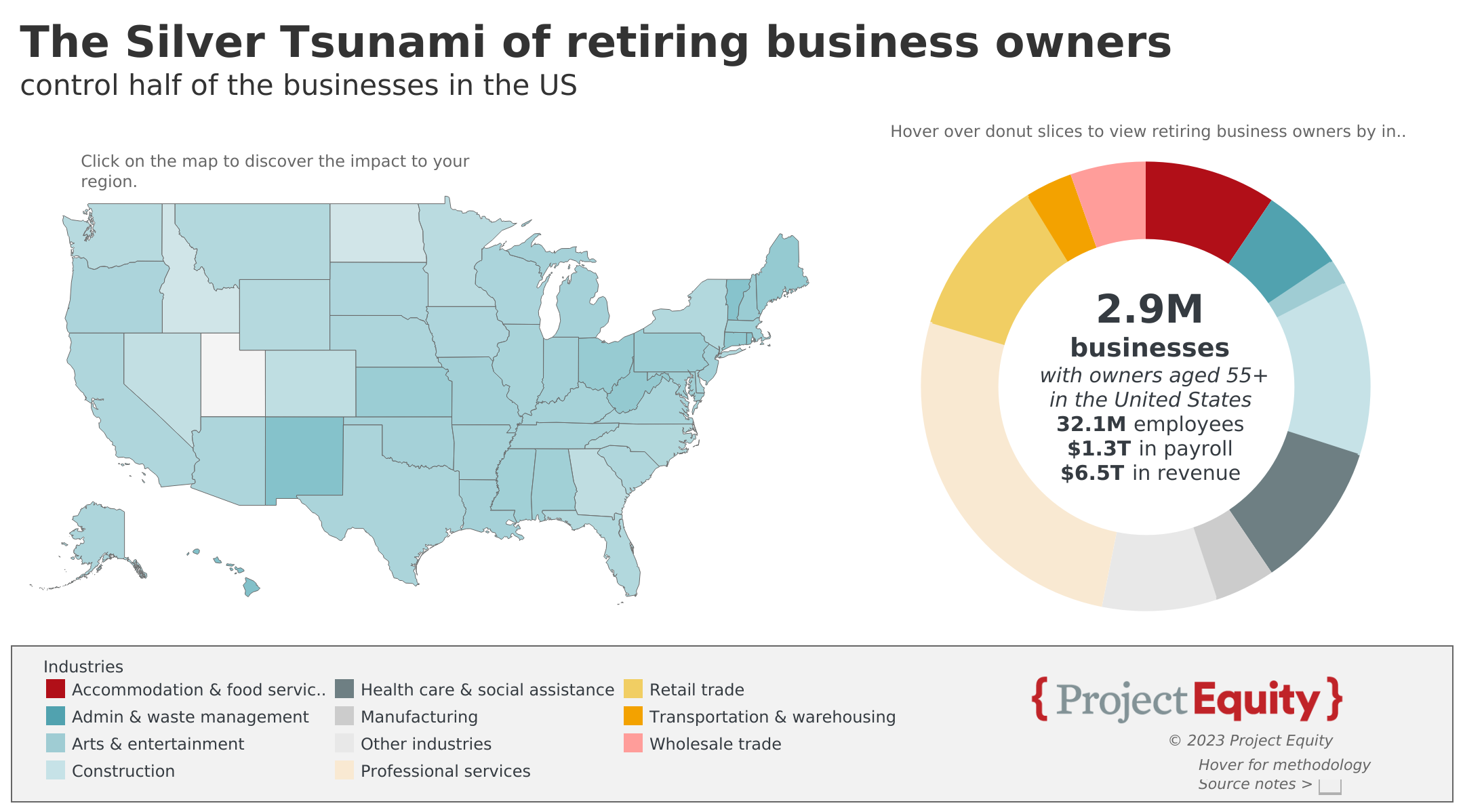

State, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) governments face a significant increase in cyber threats, with incidents like remote access trojans and complex malware attacks rising sharply in 2023. These trends indicate not only a rise in the number of attacks but also an increase in their sophistication, requiring SLTTs to contend with a diverse and evolving array of cyber threats.The 2022 Nationwide Cybersecurity Review (NCSR) found that most SLTTs have not yet achieved the cybersecurity maturity needed to effectively defend against these sophisticated attacks, largely due to limited resources and personnel shortages. Smaller municipalities, especially in rural areas, are particularly impacted, with many unable to implement or maintain the range of tools required for comprehensive security. As a result, SLTTs remain vulnerable, and critical public infrastructure risks being compromised. This urgent situation presents an opportunity for CISA to strengthen regional cybersecurity efforts through enhanced public-private collaboration, empowering SLTTs to build resilience and raise baseline cybersecurity standards.

Average cyber maturity scores for the State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial peer groups are at the minimum required level or below. Source: Center for Internet Security

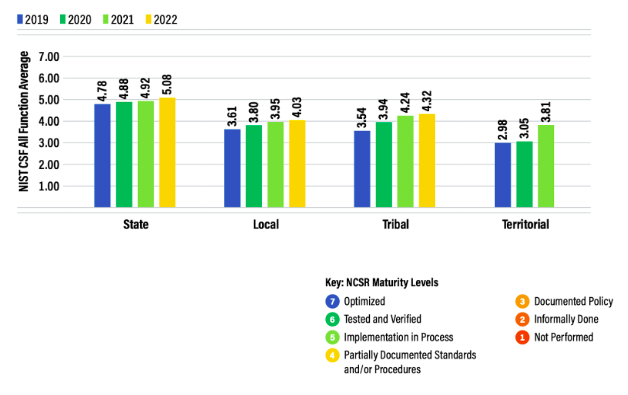

Furthermore, effective cybersecurity requires managing a complex array of tools and technologies. Many SLTT organizations, particularly those in critical infrastructure sectors, need to deploy and manage dozens of cybersecurity tools, including asset management systems, firewalls, intrusion detection systems, endpoint protection platforms, and data encryption tools, to safeguard their operations.

An example of the immense array of different combinations of cybersecurity tools that could comprise a full suite necessary to implement baseline cybersecurity controls. Source: The Software Analyst Newsletter

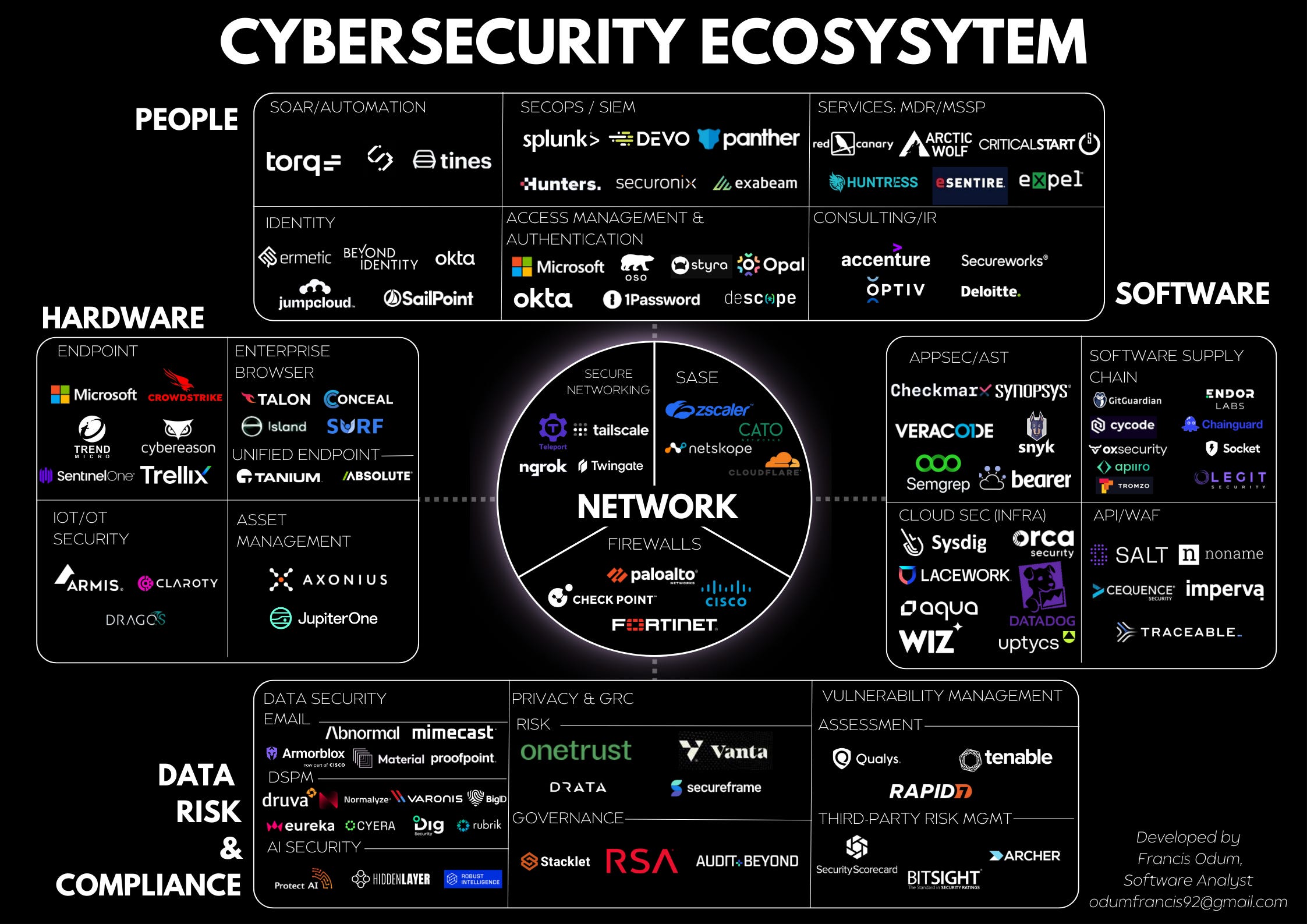

The ability of SLTTs to implement these tools is severely hampered by two critical issues: insufficient funding and a shortage of skilled cybersecurity professionals to operate such a large volume of tools that require tuning and configuration. Budget constraints mean that many SLTT organizations are forced to make difficult decisions about which tools to prioritize, and the shortage of qualified cybersecurity professionals further limits their ability to operate them. The Deloitte-NASCIO Cybersecurity Study highlights how state Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs) are increasingly turning to the private sector to fill gaps in their workforce, procuring staff-augmentation resources to support security control deployment, management of Security Operations Centers (SOCs), and incident response services.

The Top 5 Security Concerns for Nationwide Cybersecurity Review Respondents include lack of sufficient funding and inadequate availability of cybersecurity professionals. Source: Centers for Internet Security.

What Strong Regionalized Communities Would Achieve

This reliance on private-sector expertise presents a unique opportunity for federal policymakers to foster stronger public-private partnerships. However, currently, JCDC membership entry requirements are vague and appear to favor more established companies, limiting participation from many professionals who are actively engaged in this mission.

The JCDC is led by CISA’s Stakeholder Engagement Division (SED) which also serves as the agency’s hub for the shared stakeholder information that unifies CISA’s approach to whole-of-nation operational collaboration. One of the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative’s (JCDC) main goals is to “organize and support efforts that strengthen the foundational cybersecurity posture of critical infrastructure entities,” ensuring they are better equipped to defend against increasingly sophisticated threats.

Given the escalating cybersecurity challenges, there is a significant opportunity for CISA to enhance localized collaboration between the public and private sectors in the form of improving the quality of service delivery that personnel at managed service providers and software companies can provide. This helps SLTTs/CIs close the workforce gap, allows vendors to create new services focused on SLTT/CIs consultative needs, and boosts a talent market that incentivizes companies to hire more technologists fluent in the “business” needs of SLTTs/CIs.

Incentivizing the Private Sector to Participate

With intense competition for market share in cybersecurity, vendors will need to provide good service and successful outcomes in order to retain and grow their portfolio of business. They will have to compete on their ability to deliver better, more tailored service to SLTTs/CIs and pursue talent that is more fluent in government operations, which incentivizes candidates to build great reputations amongst SLTT/CI customers.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Community Platform

To accelerate the progress of CISA’s mission to improve the cyber baseline for SLTT/CIs, the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative (JCDC) should expand into a regional framework aligned with CISA’s 10 regional offices to support increasing participation. The new, regionalized JCDC should facilitate membership for all practitioners that support the cyber defense of SLTT/CIs, regardless of whether they are employed by a private or public sector entity. With a more complete community, CISA will be able to direct focused, custom implementation strategies that require deep public-private collaboration.

Participants from relevant sectors should be able to join the regional JCDC after passing background checks, employment verification, and, where necessary, verification that the employer is involved in security control implementation for at least one eligible regional client. This approach allows the program to scale rapidly and ensures fairness across organizations of all sizes. Private sector representatives, such as solutions engineers and technical account managers, will be granted conditional membership to the JCDC, with need-to-know access to its online resources. The program will emphasize the development of collaborative security control implementation strategies centered around the client, where CISA coordinates the implementation functions between public and private sector staff, as well as between cybersecurity vendors and MSPs that serve each SLTT/CI entity.

Recommendation 2. Online Training Platform

Currently, CISA provides a multitude of training offerings both online and in-person, most of which are only accessible by government employees. Expanding CISA’s training offerings to include programs that teach practitioners at MSPs and Software Companies how to become fluent in the operation of government is essential for raising the cybersecurity baseline across various National Cybersecurity Review (NCSR) areas with which SLTTs currently struggle. The training platform should be a flexible, learn-at-your-own-pace virtual learning platform, and CISA is encouraged to develop on existing platforms with existing user bases, such as Salesforce’s Trailhead. Modules should enable students around specific challenges tailored to the SLTT/CI operating environment, such as applying patches to workstations that belong to a Police or Fire Department, where the availability of critical systems is essential, and downtime could mean lives.

The platform should offer a gamified learning experience, where participants can earn badges and certificates as they progress through different learning paths. These badges and certificates will serve as a way for companies and SLTT/CIs to understand which individuals are investing the most time learning and delivering the best service. Each badge will correspond to specific skills or competencies, allowing participants to build a portfolio of recognized achievements. This approach has already proven effective, as seen in the use of Salesforce’s Trailhead by other organizations like the Center for Internet Security (CIS), which offers an introductory course on CIS Controls v8 through the platform.

The benefits of this training platform are multifaceted. First, it provides a structured and scalable way to upskill a large number of cybersecurity professionals across the country with a focus on tailored implementation of cybersecurity controls for SLTT/CIs. Second, the badge system incentivizes ongoing participation, ensuring that cybersecurity professionals can continue to maintain their reputation if they choose to move jobs between companies or between the public and private sectors. Third, the platform fosters a sense of community and collaboration around the client, allowing CISA to understand the specific individuals supporting each SLTT/CI organization, in the case that it needs to mobilize a team with both security knowledge and government operations knowledge around an incident response scenario.

Recommendation 3. A “Smart Rolodex”

A Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system should be integrated within CISA’s Office of Stakeholder Engagement to manage the community of cyber defenders more effectively and streamline incident response efforts. The CRM will maintain a singular database of regionalized JCDC members, their current company, their expertise, and their roles within critical infrastructure sectors. This system will act as a “smart Rolodex,” enabling CISA to quickly identify and coordinate with the most suitable experts during incidents, ensuring a swift and effective response. The recent recommendations by a CISA panel underscore the importance of this approach, emphasizing that a well-organized and accessible database is crucial for deploying the right resources in real-time and enhancing the overall effectiveness of the JCDC.

Recommendation 4. Establishment of Merit-Based Recognition Programs

Finally, to foster a sense of mission and camaraderie among JCDC participants, recognition programs should be introduced to increase morale and highlight above-and-beyond contributions to national cybersecurity efforts. Digital badges, emblematic patches, “CISA Swag” or challenge coins will be awarded as symbols of achievement within the JCDC, boosting morale and practitioner commitment to the greater mission. These programs will also enhance the appeal of cybersecurity careers, elevating those involved with the JCDC, and encouraging increased participation and retention within the JCDC initiative.

Cost Analysis

Estimated Costs and Justification

The proposed regional JCDC program requires procuring ~100,000 licenses for a digital communication platform (Based on Slack) across all of its regions and 500 licenses for a popular Customer Relationship Management (CRM) platform(Based on Salesforce) for its Office of Stakeholder Engagement to be able to access records. The estimated annual costs are as follows:

Digital Communication Platform Licenses:

- Standard Plan: $8,700,000 per year (100,000 users at $7.25 per month).

CRM Platform Licenses:

- Professional Tier: $450,000 per year (500 users at $75 per month).

Total Estimated Cost:

- Lower Tier Option (Standard Communication + Professional CRM): $9,150,000 per year.

Buffer for Operational Costs: To ensure the program’s success, a buffer of approximately 15% should be added to cover additional operational expenses, unforeseen costs, and any necessary uplifts or expansions in features or seats. This does not take into consideration volume discounts that CISA would normally expect when purchasing through a reseller such as Carahsoft or CDW.

Cost Justification: Although the initial investment is significant, the potential savings from avoiding cyber incidents should far outweigh these costs. Considering that the average cost of a data breach in the U.S. is approximately $9.48 million, preventing even a few such incidents through this program could easily justify the expenditure.

Conclusion

The cybersecurity challenges faced by State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial (SLTT) governments and critical infrastructure sectors are becoming increasingly complex and urgent. As cyber threats continue to evolve, it is clear that the existing defenses are insufficient to protect our nation’s most vital services. The proposed expansion of the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative (JCDC) to allow broader participation by practitioners in the private sector who serve public sector clients, regardless of the size or current affiliation of their company presents a crucial opportunity to enhance collaboration, particularly among SLTTs, and to bolster the overall cybersecurity baseline.These efforts align closely with CISA’s strategic goals of enhancing public-private partnerships, improving the cybersecurity baseline, and fostering a skilled cybersecurity workforce. By taking decisive action now, we can create a more resilient and secure nation, ensuring that our critical infrastructure remains protected against the ever-growing array of cyber threats.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Establishing a Cyber Workforce Action Plan

The next presidential administration should establish a comprehensive Cyber Workforce Action Plan to address the critical shortage of cybersecurity professionals and bolster national security. This plan encompasses innovative educational approaches, including micro-credentials, stackable certifications, digital badges, and more, to create flexible and accessible pathways for individuals at all career stages to acquire and demonstrate cybersecurity competencies.

The initiative will be led by the White House Office of the National Cyber Director (ONCD) in collaboration with key agencies such as the Department of Education (DoE), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and National Security Agency (NSA). It will prioritize enhancing and expanding existing initiatives—such as the CyberCorps: Scholarship for Service program that recruits and places talent in federal agencies—while also spearheading new engagements with the private sector and its critical infrastructure vulnerabilities. To ensure alignment with industry needs, the Action Plan will foster strong partnerships between government, educational institutions, and the private sector, particularly focusing on real-world learning opportunities.

This Action Plan also emphasizes the importance of diversity and inclusion by actively recruiting individuals from underrepresented groups, including women, people of color, veterans, and neurodivergent individuals, into the cybersecurity workforce. In addition, the plan will promote international cooperation, with programs to facilitate cybersecurity workforce development globally. Together, these efforts aim to close the cybersecurity skills gap, enhance national defense against evolving cyber threats, and position the United States as a global leader in cybersecurity education and workforce development.

Challenge and Opportunity

The United States and its allies face a critical shortage of cybersecurity professionals, in both the public and private sectors. This shortage poses significant risks to our national security and economic competitiveness in an increasingly digital world.

In the federal government, the cybersecurity workforce is aging rapidly, with only about 3% of information technology (IT) specialists under 30 years old. Meanwhile, nearly 15% of the federal cyber workforce is eligible for retirement. This demographic imbalance threatens the government’s ability to defend against sophisticated and evolving cyber threats.

The private sector faces similar challenges. According to recent estimates, there are nearly half a million unfilled cybersecurity positions in the United States. This gap is expected to grow as cyber threats become more complex and pervasive across all industries. Small and medium-sized businesses are particularly vulnerable, often lacking the resources to compete for scarce cyber talent.

The cybersecurity talent shortage extends beyond our borders, affecting our allies as well. As cyber threats from adversarial nation states become increasingly global in nature, our international partners’ ability to defend against these threats directly impacts U.S. national security. Many of our allies, particularly in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia, lack robust cybersecurity education and training programs, further exacerbating the global skills gap.

A key factor contributing to this shortage is the lack of accessible, flexible pathways into cybersecurity careers. Traditional education and training programs often fail to keep pace with rapidly evolving technology and threat landscapes. Moreover, they frequently overlook the potential of career changers and nontraditional students who could bring valuable diverse perspectives to the field.

However, this challenge presents a unique opportunity to revolutionize cybersecurity education and workforce development. By leveraging innovative approaches such as apprenticeships, micro-credentials, stackable certifications, peer-to-peer learning platforms, digital badges, and competition-based assessments, we can create more agile and responsive training programs. These methods can provide learners with immediately applicable skills while allowing for continuous upskilling as the field evolves.

Furthermore, there’s an opportunity to enhance cybersecurity awareness and basic skills among all American workers, not just those in dedicated cyber roles. As digital technologies permeate every aspect of modern work, a baseline level of cyber hygiene and security consciousness is becoming essential across all sectors.

By addressing these challenges through a comprehensive Cyber Workforce Action Plan, we can not only strengthen our national cybersecurity posture but also create new pathways to well-paying, high-demand jobs for Americans from all backgrounds. This initiative has the potential to position the United States as a global leader in cyber workforce development, enhancing both our national security and our economic competitiveness in the digital age.

Evidence of Existing Initiatives

While numerous excellent cybersecurity workforce development initiatives exist, they often operate in isolation, lacking cohesion and coordination. ONCD is positioned to leverage its whole-of-government approach and the groundwork laid by its National Cyber Workforce and Education Strategy (NCWES) to unite these disparate efforts. By bringing together the strengths of various initiatives and their stakeholders, ONCD can transform high-level strategies into concrete, actionable steps. This coordinated approach will maximize the impact of existing resources, reduce duplication of efforts, and create a more robust and adaptable cybersecurity workforce development ecosystem. This proposed Action Plan is the vehicle to turn these collective workforce-minded strategies into tangible, measurable outcomes.

At the foundation of this plan lies the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework, developed by NIST. This common lexicon for cybersecurity work roles and competencies provides the essential structure upon which we can build. The Cyber Workforce Action Plan seeks to expand on this foundation by creating standardized assessments and implementation guidelines that can be adopted across both public and private sectors.

Micro-credentials, stackable certifications, digital badges, and other innovations in accessible education—as demonstrated by programs like SANS Institute’s GIAC certifications and CompTIA’s offerings—form a core component of the proposed plan. These modular, skills-based learning approaches allow for rapid validation of specific competencies—a crucial feature in the fast-evolving cybersecurity landscape. The Action Plan aims to standardize and coordinate these and similar efforts, ensuring widespread recognition and adoption of accessible credentials across industries.

The array of gamification and competition-based learning approaches—including but not limited to National Cyber League, SANS NetWars, and CyberPatriot—are also exemplary starting points that would benefit from greater federal engagement and coordination. By formalizing these methods within education and workforce development programs, the government can harness their power to simulate real-world scenarios and drive engagement at a national scale.

Incorporating lessons learned from the federal government’s previous DoE CTE CyberNet program, the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Scholarship for Service Program (SFS), and the National Security Agency’s (NSA) GenCyber camps—the Action Plan emphasizes the importance of early engagement (the middle grades and early high school years) and practical, hands-on learning experiences. By extending these principles across all levels of education and professional development, we can create a continuous pathway from high school through to advanced career stages.

A Cyber Workforce Action Plan would provide a unifying praxis to standardize competency assessments, create clear pathways for career progression, and adapt to the evolving needs of both the public and private sectors. By building on the successes of existing initiatives and introducing innovative solutions to fill critical gaps in the cybersecurity talent pipeline, we can create a more robust, diverse, and skilled cybersecurity workforce capable of meeting the complex challenges of our digital future.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Create a Cyber Workforce Action Plan.

ONCD will develop and oversee the plan, in close collaboration with DoE, NIST, NSA, and other relevant agencies. The plan has three distinct components:

1. Develop standardized assessments aligned with the NICE framework. ONCD will work with NIST to create a suite of standardized assessments to evaluate cybersecurity competencies that:

- Cover the full range of knowledge, skills, and abilities defined in the NICE framework.

- Include both theoretical knowledge tests and practical, scenario-based evaluations.

- Be regularly updated to reflect evolving cybersecurity threats and technologies.

- Be designed with input from both government and industry cybersecurity professionals to ensure relevance and applicability.

2. Establish a system of stackable and portable micro-credentials. To provide flexible and accessible pathways into cybersecurity careers, ONCD will work with DoE, NIST, and the private sector to help develop and support systems of micro-credentials that are:

- Aligned with specific competencies in the NICE framework: NIST, as the national standards-setting body, will issue these credentials to ensure alignment with the NICE framework. This will provide legitimacy and broad recognition across industries.

- Stackable, allowing learners to build towards larger certifications or degrees: These credentials will be designed to allow individuals to accumulate certifications over time, ultimately leading to more comprehensive qualifications or degrees.

- Portable across different sectors and organizations: The micro-credentials will be recognized by both government agencies and private-sector employers, ensuring they have value regardless of where an individual seeks employment.

- Recognized and valued by both government agencies and private-sector employers: By working closely with the private sector—where credentialing systems like those from CompTIA and Google are already advanced—the ONCD will help ensure government-issued credentials are not duplicative but complementary to existing industry standards. NIST’s involvement, combined with input from private-sector leaders, will provide confidence that these credentials are relevant and accepted in both public and private sectors.

- Designed to facilitate rapid upskilling and reskilling in response to evolving cybersecurity needs: Given the rapidly changing landscape of cybersecurity threats, these micro-credentials will be regularly updated to reflect the most current technologies and skills, enabling professionals to remain agile and competitive.

3. Integrate more closely with more federal initiatives. The Action Plan will be integrated with existing federal cybersecurity programs and initiatives, including:

- DHS’s Cybersecurity Talent Management System

- DoD’s Cyber Excepted Service

- NIST’s NICE framework

- NSF’s CyberCorps SFS program

- NSA’s GenCyber camps

This proposal emphasizes stronger integration with existing federal initiatives and greater collaboration with the private sector. Instead of creating entirely new credentialing standards, ONCD will explore opportunities to leverage widely adopted commercial certifications, such as those from Google, CompTIA, and other private-sector leaders. By selecting and promoting recognized commercial standards where applicable, ONCD can streamline efforts, avoiding duplication and ensuring the cybersecurity workforce development approach is aligned with what is already successful in industry. Where necessary, ONCD will work with NIST and industry professionals to ensure these commercial certifications meet federal needs, creating a more cohesive and efficient approach across both government and industry. This integrated public-private strategy will allow ONCD to offer a clear leadership structure and accountability mechanism while respecting and utilizing commercial technology and standards to address the scale and complexity of the cybersecurity workforce challenge.

The Cyber Workforce Action Plan will emphasize strong collaborations with the private sector, including the establishment of a Federal Cybersecurity Curriculum Advisory Board composed of experts from relevant federal agencies and leading private-sector companies. This board will work directly with universities to develop model curricula that incorporate the latest cybersecurity tools, techniques, and threat landscapes, ensuring that graduates are well-prepared for the specific challenges faced by both federal and private-sector cybersecurity professionals.

To provide hands-on learning opportunities, the Action Plan will include a new National Cyber Internship Program. Managed by the Department of Labor in partnership with DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and leading technology companies, the program will match students with government agencies and private-sector companies. An online platform will be developed, modeled after successful programs like Hacking for Defense, where industry partners can propose real-world cybersecurity projects for student teams.

To incentivize industry participation, the General Services Administration (GSA) and DoD will update federal procurement guidelines to require companies bidding on cybersecurity-related contracts to certify that they offer internship or early-career opportunities for cybersecurity professionals. Additionally, CISA will launch a “Cybersecurity Employer of Excellence” certification program, which will be a prerequisite for companies bidding on certain cybersecurity-related federal contracts.

The Action Plan will also address the global nature of cybersecurity challenges by incorporating international cooperation elements. This includes adapting the plan for international use in strategically important regions, facilitating joint training programs and professional exchanges with allied nations, and promoting global standardization of cybersecurity education through collaboration with international standards organizations.

Ultimately, this effort intends to implement a national standard for cybersecurity competencies—providing clear, accessible pathways for career progression and enabling more agile and responsive workforce development in this critical field.

Recommendation 2. Implement an enhanced CyberCorps fellowship program.

ONCD should expand the NSF’s CyberCorps Scholarship for Service program as an immediate, high-impact initiative. Key features of the expanded CyberCorps fellowship program include:

1. Comprehensive talent pipeline: While maintaining the current SFS focus on students, the enhanced CyberCorps will also target recent graduates and early-career professionals with 1–5 years of work experience. This expansion addresses immediate workforce needs while continuing to invest in future talent. The program will offer competitive salaries, benefits, and loan forgiveness options to attract top talent from both academic and private-sector backgrounds.

2. Multiagency exposure and optional rotations: While cross-sector exposure remains valuable for building a holistic understanding of cybersecurity challenges, the rotational model will be optional or limited based on specific agency needs. Fellows may be offered the opportunity to rotate between agencies or sectors only if their skill set and the hosting agency’s environment are conducive to short-term placements. For fellows placed in agencies or sectors where longer ramp-up times are expected, a deeper, longer-term placement may be more effective. Drawing on lessons from the Presidential Innovation Fellows and the U.S. Digital Corps, the program will emphasize flexibility to ensure that fellows can make meaningful contributions within the time frame and that knowledge transfer between sectors remains a core objective.

3. Advanced mentorship and leadership development: Building on the SFS model, the expanded program will foster a strong community of cyber professionals through cohort activities and mentorship pairings with senior leaders across government and industry. A new emphasis on leadership training will prepare fellows for senior roles in government cybersecurity.

4. Focus on emerging technologies: Complementing the SFS program’s core cybersecurity curriculum, the expanded CyberCorps will emphasize cutting-edge areas such as artificial intelligence in cybersecurity, quantum computing, and advanced threat detection. This focus will prepare fellows to address future cybersecurity challenges.

5. Extended impact through education and mentorship: The program will encourage fellows to become cybersecurity educators and mentors in their communities after their service, extending the program’s impact beyond government service and strengthening America’s overall cyber workforce.

By implementing these enhancements to the CyberCorps program as a first step and quick win, the Action Plan will initiate a more comprehensive approach to federal cybersecurity workforce development. The enhanced CyberCorps fellowship program will also emphasize diversity and inclusion to address the critical shortage of cybersecurity professionals and bring fresh perspectives to cyber challenges. The program will actively recruit individuals from underrepresented groups, including women, people of color, veterans, and neurodivergent individuals.

To achieve this, the program will partner with organizations like Girls Who Code and the Hispanic IT Executive Council to promote cybersecurity careers and expand the applicant pool. The Department of Labor, in conjunction with the NSF, will establish a Cyber Opportunity Fund to provide additional scholarships and grants for individuals from underrepresented groups pursuing cybersecurity education through the CyberCorps program.

In addition, the program will develop standardized apprenticeship components that provide on-the-job training and clear pathways to full-time employment, with a focus on recruiting from diverse industries and backgrounds. Furthermore, partnerships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Hispanic-Serving Institutions, and Tribal Colleges and Universities will be strengthened to enhance their cybersecurity programs and create a pipeline of diverse talent for the CyberCorps program.

The CyberCorps program will expand its scope to include an international component, allowing for exchanges with allied nations’ cybersecurity agencies and bringing international students to U.S. universities for advanced studies. This will help position the United States as a global leader in cybersecurity education and training while fostering a worldwide community of professionals capable of responding effectively to evolving cyber threats.

By incorporating these elements, the enhanced CyberCorps fellowship program will not only address immediate federal cybersecurity needs but also contribute to building a diverse, skilled, and globally aware cybersecurity workforce for the future.

Implementation Considerations

To successfully establish and execute the comprehensive Action Plan and its associated initiatives, careful planning and coordination across multiple agencies and stakeholders will be essential. Below are some of the key timeline and funding considerations the ONCD should factor into its implementation.

Key milestones and actions for the first two years

Months 1–6:

- Create the Cyber Workforce Action Plan as a roadmap to implementing ONCD’s NCWES.

- Form interagency working group and private-sector advisory board.

- NIST’s Information Technology Laboratory, in collaboration with industry partners, will begin the development of the standardized assessment system and micro-credentials framework.

- Initiate the Federal Cybersecurity Curriculum Advisory Board.

- Launch the expanded CyberCorps fellowship program recruitment.

Months 7–12:

- Implement pilot programs for standardized assessments and micro-credentials.

- Begin first cohort of expanded CyberCorps fellows.

- Launch diversity and inclusion initiatives, including the “Cyber for All” awareness campaign.

- Initiate the National Cybersecurity Internship Program.

- Begin development of the Cybersecurity Employer of Excellence recognition program.

Months 13–18:

- Pilot standardized assessments and micro-credentials system in select agencies and educational institutions, with full rollout anticipated after evaluation and adjustments based on feedback.

- Expand CyberCorps program and university partnerships.

- Implement private-sector internship and project-based learning programs.

- Launch the International Cybersecurity Workforce Alliance.

Months 19–24:

- Implement tax incentives for industry participation in workforce development.

- Establish the Cybersecurity Development Fund for international capacity building.

- Conduct first annual review of diversity and inclusion metrics in federal cyber workforce.

Program evaluation and quality assurance

Beyond these key milestones, the Action Plan must establish clear evaluation frameworks to ensure program quality and effectiveness, particularly for integrating non-federal education programs into federal hiring pathways. For example, to address OPM’s need for evaluating non-federal technical and career education programs under the Recent Graduates Program, the Action Plan will implement the following evaluation framework:

- Alignment with NICE framework competencies (minimum 80% coverage of core competencies)

- Completion of NIST-approved standardized technical assessments

- Documentation of supervised practical experience (minimum 400 hours)

- Evidence of quality assurance processes comparable to registered apprenticeship programs

- Regular curriculum updates (minimum annually) to reflect current security threats

- Industry partnership validation through the Cybersecurity Employer of Excellence program

The implementation of these criteria will be overseen by the same advisory board established in Months 1-6, expanding their scope to include program evaluation and certification. This approach leverages existing governance structures while providing OPM with quantifiable metrics to evaluate non-federal program graduates.

Budgetary, resource, and personnel needs

The estimated annual budget for the proposed initiative ranges from $125 million to $200 million. This range considers cost-effective resource allocation strategies, including the integration of existing platforms and focused partnerships. Key components of the program include:

- Staffing: A core team of 15–20 full-time employees will oversee the centralized program office, focusing on high-level coordination and oversight. Specialized tasks such as curriculum development and assessment design will be contracted to external partners, reducing the need for a larger in-house team.

- IT infrastructure: Rather than building new systems from scratch, the initiative will use existing platforms and credentialing technologies from private-sector providers (e.g., CompTIA, Coursera). This significantly reduces upfront development costs while ensuring a robust system for managing assessments and credentials.

- Marketing and outreach: A smaller but targeted budget will be allocated for domestic and international outreach to raise awareness of the program. Partnerships with industry and educational institutions will help amplify these efforts, reducing the need for a large marketing budget.

- Grants and partnerships: The program will provide modest grants to universities to support curriculum development, with a focus on fostering partnerships rather than large-scale financial commitments. This allows for more cost-effective collaboration with educational institutions.

- Fellowship programs and international exchanges: The expanded CyberCorps fellowship will begin with a smaller cohort, scaling up based on available funding and demonstrated success. International exchanges will be limited to strategic, high-impact partnerships to ensure cost efficiency while still addressing global cybersecurity needs.

Potential funding sources

Funding for this initiative can be sourced through a variety of channels. First, congressional appropriations via the annual budget process are expected to provide a significant portion of the financial support. Additionally, reallocating existing funds from cybersecurity and workforce development programs could account for approximately 25–35% of the overall budget. This reallocation could include funding from current programs like NICE, SFS, and other workforce development grants, which can be repurposed to support this broader initiative without requiring entirely new appropriations.

Public-private partnerships will also be explored, with potential contributions from industry players who recognize the value of a robust cybersecurity workforce. Grants from federal entities such as DHS, DoD, and NSF are viable options to supplement the program’s financial needs. To offset costs, fees collected from credentialing and training programs could serve as an additional revenue stream.

Finally, the Action Plan and its initiatives will seek contributions from international development funds aimed at capacity-building, as well as financial support from allied nations to aid in the establishment of joint international programs.

Conclusion

Establishing a comprehensive Cyber Workforce Action Plan represents a pivotal move toward securing America’s digital future. By creating flexible, accessible career pathways into cybersecurity, fostering innovative education and training models, and promoting both domestic diversity and international cooperation, this initiative addresses the urgent need for a skilled and resilient cybersecurity workforce.

The impact of this proposal is wide-ranging. It will not only reinforce national security by strengthening the nation’s cyber defenses but also contribute to economic growth by creating high-paying jobs and advancing U.S. leadership in cybersecurity on the global stage. By expanding access to cybersecurity careers and engaging previously underutilized talent pools, this initiative will ensure the workforce reflects the diversity of the nation and is prepared to meet future cybersecurity challenges.

The next administration must make the implementation of this plan a national priority. As cyber threats grow more complex and sophisticated, the nation’s ability to defend itself depends on developing a robust, adaptable, and highly skilled cybersecurity workforce. Acting swiftly to establish this strategy will build a stronger, more resilient digital infrastructure, ensuring both national security and economic prosperity in the 21st century. We urge the administration to allocate the necessary resources and lead the transformation of cybersecurity workforce development. Our digital future—and our national security—demand immediate action.

Teacher Education Clearinghouse for AI and Data Science

The next presidential administration should develop a teacher education and resource center that includes vetted, free, self-guided professional learning modules, resources to support data-based classroom activities, and instructional guides pertaining to different learning disciplines. This would provide critical support to teachers to better understand and implement data science education and use of AI tools in their classroom. Initial resource topics would be:

- An Introduction to AI, Data Literacy, and Data Science

- AI & Data Science Pedagogy

- AI and Data Science for Curriculum Development & Improvement

- Using AI Tools for Differentiation, Assessment & Feedback

- Data Science for Ethical AI Use

In addition, this resource center would develop and host free, pre-recorded, virtual training sessions to support educators and district professionals to better understand these resources and practices so they can bring them back to their contexts. This work would improve teacher practice and cut administrative burdens. A teacher education resource would lessen the digital divide and ensure that our educators are prepared to support their students in understanding how to use AI tools so that each and every student can be college and career ready and competitive at the global level. This resource center would be developed using a process similar to the What Works Clearinghouse, such that it is not endorsing a particular system or curriculum, but is providing a quality rating, based on the evidence provided.

Challenge and Opportunity

AI is an incredible technology that has the power to revolutionize many areas, especially how educators teach and prepare the next generation to be competitive in higher education and the workforce. A recent RAND study showed leaders in education indicating promise in adapting instructional content to fit the level of their students and for generating instructional materials and lesson plans. While this technology holds a wealth of promise, the field has developed so rapidly that people across the workforce do not understand how best to take advantage of AI-based technologies. One of the most crucial areas for this is in education. AI-enabled tools have the potential to improve instruction, curriculum development, and assessment, but most educators have not received adequate training to feel confident using them in their pedagogy. In a Spring 2024 pilot study (Beiting-Parrish & Melville, in preparation), initial results indicated that 64.3% of educators surveyed had not had any professional development or training in how to use AI tools. In addition, more than 70% of educators surveyed felt they did not know how to pick AI tools that are safe for use in the classroom, and that they were not able to detect biased tools. Additionally, the RAND study indicated only 18% of educators reported using AI tools for classroom purposes. Within those 18%, approximately half of those educators used AI because they had been specifically recommended or directly provided a tool for classroom use. This suggests that educators need to be given substantial support in choosing and deploying tools for classroom use. Providing guidance and resources to support vetting tools for safe, ethical, appropriate, and effective instruction is one of the cornerstone missions of the Department of Education. This education should not rest on the shoulders of individual educators who are known to have varying levels of technical and curricular knowledge, especially for veteran teachers who have been teaching for more than a decade.

If the teachers themselves do not have enough professional development or expertise to select and teach new technology, they cannot be expected to thoroughly prepare their students to understand emerging technologies, such as AI, nor the underpinning concepts necessary to understand these technologies, most notably data science and statistics. As such, students’ futures are being put at risk from a lack of emphasis in data literacy that is apparent across the nation. Recent results from the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP), assessment scores show a shocking decline in student performance in data literacy, probability, and statistics skills – outpacing declines in other content areas. In 2019, the NAEP High School Transcript Study (HSTS) revealed that only 17% of students completed a course in statistics and probability, and less than 10% of high school students completed AP Statistics. Furthermore, the HSTS study showed that less than 1% of students completed a dedicated course in modern data science or applied data analytics in high school. Students are graduating with record-low proficiency in data, statistics, and probability, and graduating without learning modern data science techniques. While students’ data and digital literacy are failing, there is a proliferation of AI content online; they are failing to build the necessary critical thinking skills and a discerning eye to determine what is real versus what has been AI-generated, and they aren’t prepared to enter the workforce in sectors that are booming. The future the nation’s students will inherit is one in which experience with AI tools and Big Data will be expected to be competitive in the workforce.

Whether students aren’t getting the content because it isn’t given its due priority, or because teachers aren’t comfortable teaching the content, AI and Big Data are here, and our educators don’t have the tools to help students get ready for a world in the midst of a data revolution. Veteran educators and preservice education programs alike may not have an understanding of the essential concepts in statistics, data literacy, or data science that allow them to feel comfortable teaching about and using AI tools in their classes. Additionally, many of the standard assessment and practice tools are not fit for use any longer in a world where every student can generate an A-quality paper in three seconds with proper prompting. The rise of AI-generated content has created a new frontier in information literacy; students need to know to question the output of publically available LLM-based tools, such as Chat-GPT, as well as to be more critical of what they see online, given the rise of AI-generated deep fakes, and educators need to understand how to either incorporate these tools into their classrooms or teach about them effectively. Whether educators are ready or not, the existing Digital Divide has the potential to widen, depending on whether or not they know how to help students understand how to use AI safely and effectively and have the access to resources and training to do so.

The United States finds itself at a crossroads in the global data boom. Demand in the economic marketplace, and threat to national security by way of artificial intelligence and mal-, mis-, and disinformation, have educators facing an urgent problem in need of an immediate solution. In August of 1958, 66 years ago, Congress passed the National Defense Education Act (NDEA), emphasizing teaching and learning in science and mathematics. Specifically in response to the launch of Sputnik, the law supplied massive funding to, “insure trained manpower of sufficient quality and quantity to meet the national defense needs of the United States.” The U.S. Department of Education, in partnership with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, must make bold moves now to create such a solution, as Congress did once before.

Plan of Action

In the years since the Space Race, one problem with STEM education persists: K-12 classrooms still teach students largely the same content; for example, the progression of high school mathematics including algebra, geometry, and trigonometry is largely unchanged. We are no longer in a race to space – we’re now needing to race against data. Data security, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and other mechanisms of our new information economy are all connected to national security, yet we do not have educators with the capacity to properly equip today’s students with the skills to combat current challenges on a global scale. Without a resource center to house the urgent professional development and classroom activities America’s educators are calling for, progress and leadership in spaces where AI and Big Data are being used will continue to dwindle, and our national security will continue to be at risk. It’s beyond time for a new take on the NDEA that emphasizes more modern topics in the teaching and learning of mathematics and science, by way of data science, data literacy, and artificial intelligence.

Previously, the Department of Education has created resource repositories to support the dissemination of information to the larger educational praxis and research community. One such example is the What Work Clearinghouse, a federally vetted library of resources on educational products and empirical research that can support the larger field. The WWC was created to help cut through the noise of many different educational product claims to ensure that only high-quality tools and research were being shared. A similar process is happening now with AI and Data Science Resources; there are a lot of resources online, but many of these are of dubious quality or are even spreading erroneous information.

To combat this, we suggest the creation of something similar to the WWC, with a focus on vetted materials for educator and student learning around AI and Data Science. We propose the creation of the Teacher Education Clearinghouse (TEC) underneath the Institute of Education Sciences, in partnership with the Office of Education Technology. Currently, WWC costs approximately $2,500,000 to run, so we anticipate a similar budget for the TEC website. The resource vetting process would begin with a Request for Information from the larger field that would encourage educators and administrators to submit high quality materials. These materials would be vetted using an evaluation framework that looks for high quality resources and materials.

For example, the RFI might request example materials or lesson goals for the following subjects:

- An Introduction to AI, Data Literacy, and Data Science

- Introduction to AI & Data Science Literacy & Vocabulary

- Foundational AI Principles

- Cross-Functional Data Literacy and Data Science

- LLMs and How to Use Them

- Critical Thinking and Safety Around AI Tools

- AI & Data Science Pedagogy

- AI and Data Science for Curriculum Development & Improvement

- Using AI Tools for Differentiation, Assessment & Feedback

- Data Science for Safe and Ethical AI Use

- Characteristics of Potentially Biased Algorithms and Their Shortcomings

A framework for evaluating how useful these contributions might be for the Teacher Education Clearinghouse would consider the following principles:

- Accuracy and relevance to subject matter

- Availability of existing resources vs. creation of new resources

- Ease of instructor use

- Likely classroom efficacy

- Safety, responsible use, and fairness of proposed tool/application/lesson

Additionally, this would also include a series of quick start guide books that would be broken down by topic and include a set of resources around foundational topics such as, “Introduction to AI” and “Foundational Data Science Vocabulary”.