At 11th Hour, New START Data Reaffirms Importance of Extending Treaty

Just four months before the New START treaty is set to expire, the latest set of so-called aggregate data published by the State Department shows the treaty is working and that both countries – despite tense military and political rhetoric – are keeping their vast strategic nuclear arsenals within the limits of the treaty.

The treaty caps the number of long-range strategic missiles and heavy bombers the two countries can possess to 800, with no more than 700 launchers and 1,550 warheads deployed. The treaty entered into force in February 2011, into effect in February 2018, and is set to expire on February 5, 2021 – unless the two countries agree to extend it for an additional five years.

Twice a year, the two countries have exchanged detailed data on their strategic forces. Of that data, the public gets to see three sets of numbers twice a year (1 March and 1 October): the aggregate data of deployed launchers, warheads attributed to those launchers, and total launchers. This time, the web-version helpfully includes the full data set (including a breakdown of US forces; it would be helpful is Moscow could also publish its breakdown) but the PDF-version does not.

This is the final set of periodic six-month aggregate data to be released, although a final set will probably be released if the treaty expires in February. If the treaty is extended for another five years, an additional ten data sets would probably be released.

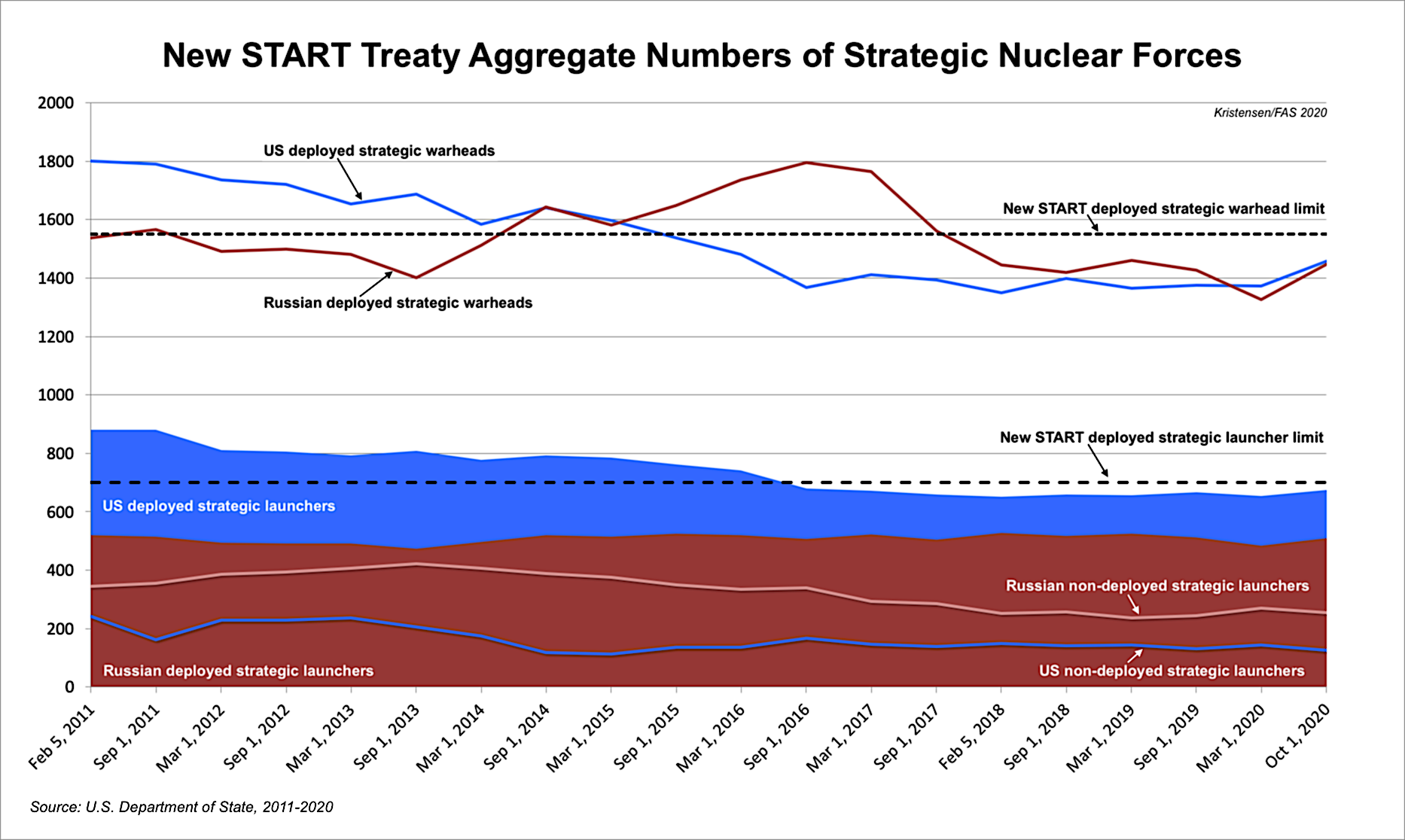

The nearly ten years of aggregate data published so far looks like this:

Combined Forces

The latest set of this data shows the situation as of October 1, 2020. As of that date, the two countries possessed a combined total of 1,564 accountable strategic missiles and heavy bombers, of which 1,185 launchers were deployed with 2,904 warheads. That is a slight increase in the number of deployed launchers and warheads compared with six months ago (note: the combined warhead number is actually about 100 too high because each deployed bomber is counted as one weapon even though neither country’s bombers carry weapons under normal circumstances).

Compared with March 2020, the data shows the two countries combined increased the total number of strategic launchers by 10, increased combined deployed strategic launchers by 45, and increased the combined deployed strategic warheads by 205. Of these numbers, only the “10” is real; the other changes reflect natural fluctuations as launchers move in and out of maintenance or are being upgraded.

In terms of the total effect of the treaty, the data shows the two countries since February 2011 have cut 425 strategic launchers from their combined arsenals, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 218, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 433. However, it is important to remind that this warhead reduction is but a fraction (less than 6 percent) of the estimated 8,110 warheads that remain in the two countries combined nuclear weapons stockpiles (less than 4 percent if counting their total combined inventories of 12,170 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The United States

The data shows the United States currently possessing 800 strategic launchers, the maximum number allowed by the treaty, of which 675 are deployed with 1,457 warheads attributed to them. This is an increase of 20 deployed strategic launchers and 84 deployed strategic warheads over the past 6 months. These are not actual increases but reflect normal fluctuations caused by launchers moving in and out of maintenance. The United States has not reduced its total inventory of strategic launchers since 2017.

The warhead numbers are interesting because they reveal that the United States now deploys 1,009 warheads on the 220 deployed Trident missiles on the SSBN fleet. That’s an increase of 82 warheads compared with March and the first time since 2015 that the United States has deployed more than 1,000 warheads on its submarines, or an average of 4-5 warheads per deployed missile. Overall, this accounts for nearly 70 percent of all the 1,457 warheads attributed to the deployed strategic launchers (nearly 72 percent if excluding the “fake” 50 bomber weapons included in the official count).

The New START data reveals that the United States as of October 1, 2020 deployed over 1,000 warheads on its fleet of ballistic missile submarines.

Compared with February 2011, the United States has reduced its inventory of strategic launchers by 324, deployed launchers by 207, and deployed strategic warheads by 343. While important, the warhead reduction represents only a small fraction (about 9 percent) of the 3,800 warheads that remain in the U.S. stockpile (less than 6 percent if counting total inventory of 5,800 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian Federation

The New START data shows Russia with an inventory of 764 strategic launchers, of which 510 are deployed with 1,447 warheads attributed to them. Compared with six months ago, this is an increase of 25 deployed launchers and 121 deployed strategic warheads. The change reflects fluctuations caused by launcher maintenance and upgrade work to new systems.

Compared with February 2011, Russia has cut its inventory of strategic launchers by 101, deployed launchers by 11, and deployed strategic warheads by 90. This modest warhead reduction represents about 2 percent of the estimated 4,310 warheads that remain in Russia’s nuclear weapons stockpile (not even 3 percent if counting the total inventory of 6,370 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) Russian warheads).

Compared with 2011, the Russian reductions accomplished under New START are smaller than the U.S. reductions because Russia had fewer strategic forces than the United States when the treaty entered into force in 2011.

Build-up, What Build-up?

With frequent claims by U.S. officials and nuclear weapons advocates that Russia is increasing its nuclear arsenal, it is interesting that despite a significant modernization program, the New START data shows this increase is not happening in the size of Russia’s accountable strategic nuclear forces. (The number of strategic-range nuclear forces outside New START is minuscule.)

On the contrary, the New START data shows that Russia has 165 deployed strategic launchers less than the United States, a significant gap that exceeds the size of an entire US Air Force ICBM wing. It is significant that Russia despite its modernization programs has not sought to reduce this gap by deploying more strategic launchers. Instead, the Russian launcher deficit has been increasing by one-third since its lowest point in February 2018. One factor that could change this is if the Trump administration kills New START and Russia believes the threat made by Marshall Billingslea, the Trump administration’s Special Presidential Envoy for Arms Control, that the United States might increase its nuclear forces if New START expires.

The New START data shows that Russia’s nuclear modernization program has not been trying increase the number of launchers despite a sizable gap compared with the US arsenal.

Instead, the Russian military appears to try to compensate for the launcher gap by increasing the number of warheads that can be carried on the newer missiles that are replacing older types (Yars and Bulava). Many of these warheads are not deployed on the missiles under normal circumstance, however, but stored and could potentially be uploaded onto launchers in a crisis. The United States also has such an upload capability for its larger inventory of launchers and therefore is not at a strategic disadvantage.

Two of Russia’s new strategic nuclear weapons (Avangard and Sarmat) are covered by New START if formally incorporated. Other types, which have become a sticking point for the Trump administration, are in relatively small numbers (if they have even been deployed yet) and do not appear capable of upsetting the strategic balance in the foreseeable future. The treaty includes provisions for including new weapon types.

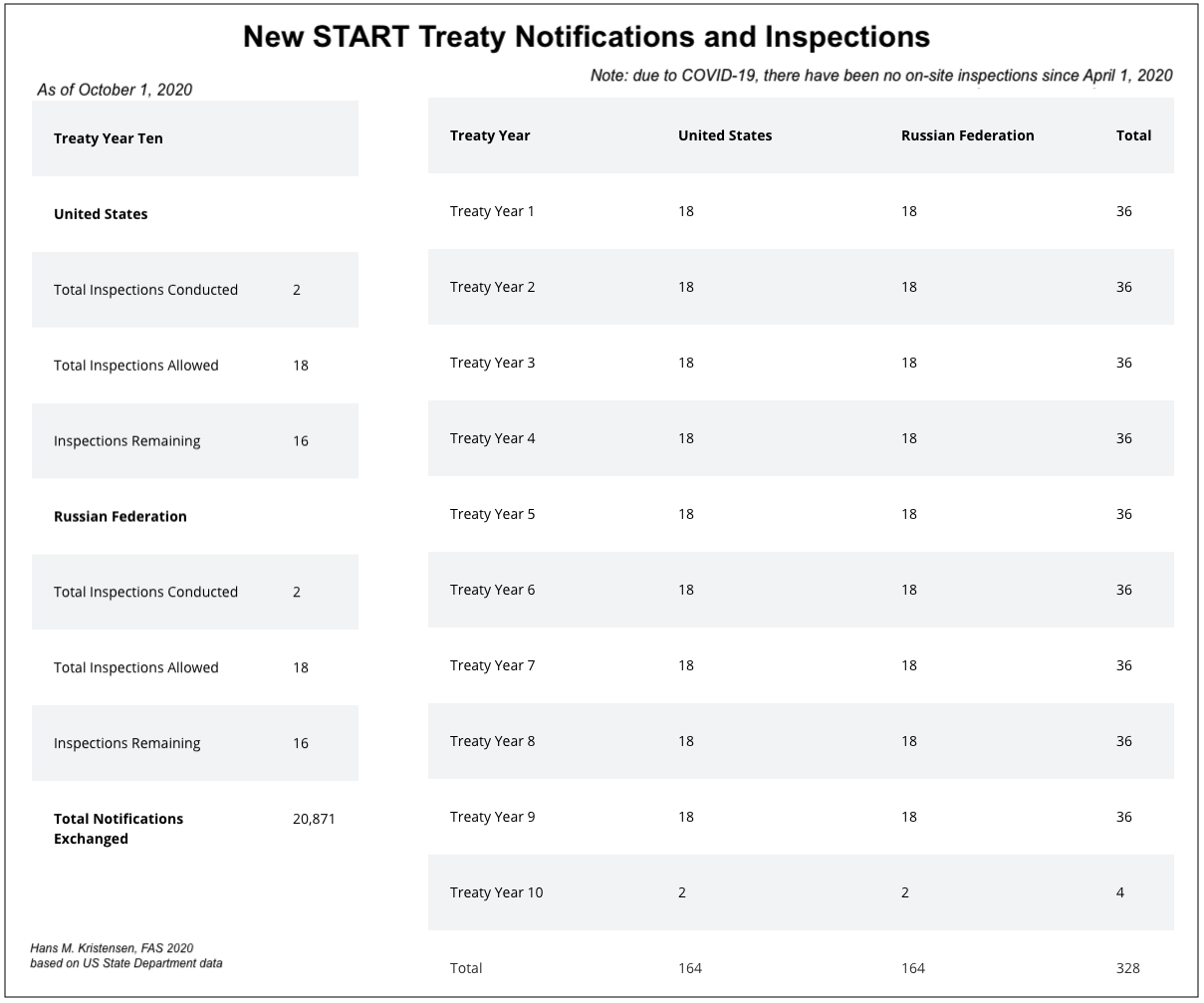

Inspections and Notifications

In addition to the New START data, the U.S. State Department has also updated the overview of part of its treaty verification activities. The data shows that the two sides since February 2011 have carried out 328 on-site inspections of each other’s strategic nuclear forces and exchanged 20,871 notifications of launcher movements and activities. Nearly 1,200 of those notifications were exchanged since March 5, 2020.

Importantly, due to the Coronavirus outbreak, there have been no on-site inspections conducted since April 1, 2020. Treaty opponents might use this to argue that compliance with the treaty cannot be determined or that it shows it’s irrelevant. Both claims would be wrong because National Technical Means of verification also provide insight to activities on the ground, but that on-site inspections provide valuable additional data.

This inspection and notification regime and record are crucial parts of the treaty and increasingly important for US-Russian strategic relations as other treaties and agreements have been scuttled.

The 11th Hour

Time is now quickly running out for New START with only a little over four months remaining before the treaty expires on February 5, 2021. Rather than working to secure extension, the Trump administration instead has introduced last-minute conditions that threaten to derail extension.

Russia and the United States can and should extend the New START treaty as is by up to 5 more years. Once that is done, they should continue negotiations on a follow-on treaty with additional limitations and improved verification. It is essential both sides act responsibly and do so to preserve this essential cornerstone of strategic stability.

The fact that Marshall Billingslea has already threatened to increase US nuclear forces if Russia doesn’t agree to the US conditions for extending the treaty only reaffirms how important New START is for keeping a lid on US and Russian strategic nuclear forces and for providing transparency and predictability on the status and plans for the arsenals.

Additional background information:

Status of world nuclear forces, September 2020

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Crowdsourcing the Verification of Nuclear Safeguards

The possibility of mobilizing members of the public to collect information — “crowdsourcing” — to enhance verification of international nuclear safeguards is explored in a new report from Sandia National Laboratories.

“Our analysis indicates that there are ways for the IAEA [International Atomic Energy Agency] to utilize data from crowdsourcing activities to support safeguards verification,” the authors conclude.

But there are a variety of hurdles to overcome.

“Some implementations of crowdsourcing for safeguards are legally or ethically uncertain, and must be carefully considered prior to adoption.”

Crowdsourced information, like other information, has to be independently verified, particularly since it is susceptible to error, manipulation and deception.

The report builds on previous work cited in a bibliography. See Power of the People: A Technical, Ethical and Experimental Examination of the Use of Crowdsourcing to Support International Nuclear Safeguards Verification by Zoe N. Gastelum, et al, Sandia National Laboratories, October 2017.

Monitoring Nuclear Testing is Getting Easier

The ability to detect a clandestine nuclear explosion in order to verify a ban on nuclear testing and to detect violations has improved dramatically in the past two decades.

There have been “technological and scientific revolutions in the fields of seismology, acoustics, and radionuclide sciences as they relate to nuclear explosion monitoring,” according to a new report published by Los Alamos National Laboratory that describes those developments.

“This document… reviews the accessible literature for four research areas: source physics (understanding signal generation), signal propagation (accounting for changes through physical media), sensors (recording the signals), and signal analysis (processing the signal).”

A “signal” here is a detectable, intelligible change in the seismic, acoustic, radiological or other environment that is attributable to a nuclear explosion.

The new Los Alamos report “is intended to help sustain the international conversation regarding the [Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty] and nuclear explosive testing moratoria while simultaneously acknowledging and celebrating research to date.”

“The primary audience for this document is the next generation of research scientists that will further improve nuclear explosion monitoring, and others interested in understanding the technical literature related to the nuclear explosion monitoring mission.”

See Trends in Nuclear Explosion Monitoring Research & Development — A Physics Perspective, Los Alamos National Laboratory, LA-UR-17-21274, June 2017.

“A ban on all nuclear tests is the oldest item on the nuclear arms control agenda,” the Congressional Research Service noted last year. “Three treaties that entered into force between 1963 and 1990 limit, but do not ban, such tests. In 1996, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), which would ban all nuclear explosions. In 1997, President Clinton sent the CTBT to the Senate, which rejected it in October 1999.”

Seeking Verifiable Destruction of Nuclear Warheads

A longstanding conundrum surrounding efforts to negotiate reductions in nuclear arsenals is how to verify the physical destruction of nuclear warheads to the satisfaction of an opposing party without disclosing classified weapons design information. Now some potential new solutions to this challenge are emerging.

Based on tests that were conducted by the Atomic Energy Commission in the 1960s in a program known as Cloudgap, U.S. officials determined at that time that secure and verifiable weapon dismantlement through visual inspection, radiation detection or material assay was a difficult and possibly insurmountable problem.

“If the United States were to demonstrate the destruction of nuclear weapons in existing AEC facilities following the concept which was tested, many items of classified weapon design information would be revealed even at the lowest level of intrusion,” according to a 1969 report on Demonstrated Destruction of Nuclear Weapons.

But in a newly published paper, researchers said they had devised a method that should, in principle, resolve the conundrum.

“We present a mechanism in the form of an interactive proof system that can validate the structure and composition of an object, such as a nuclear warhead, to arbitrary precision without revealing either its structure or composition. We introduce a tomographic method that simultaneously resolves both the geometric and isotopic makeup of an object. We also introduce a method of protecting information using a provably secure cryptographic hash that does not rely on electronics or software. These techniques, when combined with a suitable protocol, constitute an interactive proof system that could reject hoax items and clear authentic warheads with excellent sensitivity in reasonably short measurement times,” the authors wrote.

See Physical cryptographic verification of nuclear warheads by R. Scott Kemp, et al,Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published online July 18.

More simply put, it’s “the first unspoofable warhead verification system for disarmament treaties — and it keeps weapon secrets too!” tweeted Kemp.

See also reporting in Science Magazine, New Scientist, and Phys.org.

In another recent attempt to address the same problem, “we show the viability of a fundamentally new approach to nuclear warhead verification that incorporates a zero-knowledge protocol, which is designed in such a way that sensitive information is never measured and so does not need to be hidden. We interrogate submitted items with energetic neutrons, making, in effect, differential measurements of both neutron transmission and emission. Calculations for scenarios in which material is diverted from a test object show that a high degree of discrimination can be achieved while revealing zero information.”

See A zero-knowledge protocol for nuclear warhead verification by Alexander Glaser, et al, Nature, 26 June 2014.

But the technology of nuclear disarmament and the politics of it are two different things.

For its part, the U.S. Department of Defense appears to see little prospect for significant negotiated nuclear reductions. In fact, at least for planning purposes, the Pentagon foresees an increasingly nuclear-armed world in decades to come.

A new DoD study of the Joint Operational Environment in the year 2035 avers that:

“The foundation for U.S. survival in a world of nuclear states is the credible capability to hold other nuclear great powers at risk, which will be complicated by the emergence of more capable, survivable, and numerous competitor nuclear forces. Therefore, the future Joint Force must be prepared to conduct National Strategic Deterrence. This includes leveraging layered missile defenses to complicate adversary nuclear planning; fielding U.S. nuclear forces capable of threatening the leadership, military forces, and industrial and economic assets of potential adversaries; and demonstrating the readiness of these forces through exercises and other flexible deterrent operations.”

See The Joint Operating Environment (JOE) 2035: The Joint Force in a Contested and Disordered World, Joint Chiefs of Staff, 14 July 2016.

Crowd-Sourcing the Treaty Verification Problem

Verification of international treaties and arms control agreements such as the pending Iran nuclear deal has traditionally relied upon formal inspections backed by clandestine intelligence collection.

But today, the widespread availability of sensors of many types complemented by social media creates the possibility of crowd-sourcing the verification task using open source data.

“Never before has so much information and analysis been so widely and openly available. The opportunities for addressing future [treaty] monitoring challenges include the ability to track activity, materials and components in far more detail than previously, both for purposes of treaty verification and to counter WMD proliferation,” according to a recent study from the JASON defense science advisory panel. See Open and Crowd-Sourced Data for Treaty Verification, October 2014.

“The exponential increase in data volume and connectivity, and the relentless evolution toward inexpensive — therefore ubiquitous — sensors provide a rapidly changing landscape for monitoring and verifying international treaties,” the JASONs said.

Commercial satellite imagery, personal radiation detectors, seismic monitors, cell phone imagery and video, and other collection devices and systems combine to create the possibility of Public Treaty Monitoring, or PTM.

“The public unveiling and confirmation of the Natanz nuclear site in Iran was an important early example of PTM,” the report said. “In December 2002, the Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), an independent policy institute in Washington, DC, released commercial satellite images of Natanz, and based on these images assessed it to be a gas-centrifuge plant for uranium isotope separation, which turned out to be correct.”

An earlier archetype of public arms control monitoring was the joint verification project initiated in the late 1980s by the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Federation of American Scientists and the Soviet Academy of Sciences to devise acceptable methods for verifying deep reductions in nuclear weapons. The NRDC actually installed seismic monitors around Soviet nuclear test sites.

In the 1990s, John Pike’s Public Eye project pioneered the use of declassified satellite images and newly available commercial imagery for public interest applications.

Recently, among many other examples, commercial satellite imagery has been used to track development of China’s submarine fleet, as discussed in this report by Hans Kristensen of FAS.

Jeffrey Lewis and his colleagues associated with the Armscontrolwonk.com website are regularly using satellite imagery and related analytic tools to advance public understanding of international military programs.

“The reason that open source data gathering [for treaty verification] is an easier problem is that, increasingly, at least some of it will happen as a matter of course,” the JASONs said. More and more people carry mobile phones, are connected to the Internet, and actively use social media. Even with no specific effort to create incentives or crowd-sourcing mechanisms there is likely to be a wealth of images and sensor data publicly and freely shared from practically every country and region in the world.”

The flood of open source data naturally does not solve all verification problems. Much of the data collected may be of poor quality, and some of it may be erroneous or even deliberately deceptive.

There are “enormous difficulties still to be faced and work to be done before claiming confidence in the reliability of data obtained from open sources,” the JASON report said.

“The validity of the original data is especially problematic with social media, in that eyewitnesses are notoriously unreliable (especially when reporting on unanticipated or extreme events) and there can be strong reinforcement of messages — whether true or not — when a topic ‘goes viral’ on the Internet.”

“In addition to such errors, taken here to be honest mistakes and limitations of sensors, there is the possibility of willful deception and spoofing of the raw data, including through conscious insertion or duplication of false information.”

“Key to validating the findings of open sources will be confirming the independence of two or more of the sources. Multi-reporting — ‘retweeting’ — or posting of the same information is no substitute for establishing credibility.”

On the other hand, the frequent repetition of information “can provide an indication of importance or urgency… The occurrence of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake was first noted in the United States as an anomalous increase in text-messaging.” Because the information moved at near light speed, it arrived before the seismic waves could reach US seismic stations.

“Commercial satellites have also provided valuable data for analysis of (non-)compliance with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and open sources proved valuable in detecting the use of chemical weapons in Aleppo, and in subsequent steps to remove such weapons from Syria. They also informed the world about the Russian troop movements and threats to Ukraine.”

While the US Government should take steps to promote and exploit open source data collection, the report said, it should do so cautiously. “It is crucial that citizens or groups not be put at risk by encouraging open-source activities that might be interpreted as espionage. The line between open source sensors and ‘spy gear’ is thin.”

In short, the JASON report concluded, “Rapid advances in technology have led to the global proliferation of inexpensive, networked sensors that are now providing significant new levels of societal transparency. As a result of the increase in quality, quantity, connectivity and availability of open information and crowd-sourced analysis, the landscape for verifying compliance with international treaties has been greatly broadened.”

* * *

Among its recommendations, the JASON report urged the government to “promote transparency and [data] validation by… keeping open-source information and analysis open to the maximum degree possible and appropriate.”

Within the U.S. intelligence community, such transparency has notably been embraced by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency under its director Robert Cardillo.

But the Central Intelligence Agency has chosen to move in the opposite direction by shutting off much of the limited public access to open source materials that previously existed. Generations of non-governmental analysts who were raised on products of the Foreign Broadcast Information Service now must turn elsewhere, since CIA terminated public access to the DNI Open Source Center in 2013.

FAS has asked the Obama Administration to restore and increase public access to open source analyses from the DNI Open Source Center as part of the forthcoming Open Government National Action Plan.