State Department Arms Control Board Declares Cold War on China

After planning the war against Iraq, former Assistant Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz now heads the State Department’s International Security Advisory Board that recommends a Cold War against China.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A report from an advisory board to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has recommended that the United States beefs up its nuclear, conventional, and space-based posture in the Pacific to counter China.

The report, which was first described in the Washington Times, portrays China’s military modernization and intentions in highly dramatic terms that appear go beyond the assessments published so far by the Defense Department and the intelligence community.

Although the Secretary of State asked for recommendations to move US-Chinese relations away from competition and conflict toward greater transparency, mutual confidence and enhanced cooperation, the board instead has produced a report that appears to recommend policies that would increase and deepen military competition and in essence constitute a small Cold War with China.

China’s “Creeping” Nuclear Doctrine

Although the report China’s Strategic Modernization – written by the International Security Advisory Board (ISAB) – deals with China’s overall military modernization, its focus is clearly on nuclear forces. What underpins China’s expansion of its offensive nuclear capabilities, the report says, is an “emerging creep toward a Chinese assured destruction capability” to create a “mutual vulnerability relationship” with the United States.

The objective is, an interpretation the authors say is supported by “numerous Chinese military statements,” for Beijing to get enough nuclear capability “to subject the United States to coercive nuclear threats to limit potential US intervention in a regional conflict” over Taiwan and oilfields in the South China Sea.

Yet “assured destruction,” to the extent that means confidence in a retaliatory capability against the United States and Russia, has been Chinese nuclear policy for decades. Increasing US and Russian nuclear capabilities, however, convinced Chinese planners that their deterrent might not survive. The current deployment of three long-range ballistic missile versions of the mobile DF-31 is supposed to restore the survivability of their strategic deterrent.

The “mutual vulnerability relationship” the authors say China is trying to create to deter the United States from defending Taiwan or limit US escalation options is a curious argument because it implies that the United States has not been vulnerable to Chinese nuclear threats in the past. In fact, US bases and allies in the Western Pacific have been vulnerable to Chinese attacks since the 1970s and the Continental United States since the early 1980s.

It is tempting to read the authors’ use of the terms “assured destruction” and “mutual vulnerability relationship” as borrowed components of “mutual assured destruction,” or MAD, the term for the nuclear relationship that existed between the United States and the Soviet Union during much of the Cold War.

But in responding to China’s nuclear modernization and policy, it is very important not to resort to Cold War-like worst-case analysis. To that end, two of the best analyzes on Chinese nuclear policy are Iain Johnston’s China’s New ‘Old Thinking:’ The Concept of Limited Deterrence, and Michael S. Chase and Evan Medeiros’ China’s Evolving Nuclear Calculus: Modernization and Doctrinal Debate. The ISAB members should read them.

Misperceptions or Just Out of Touch

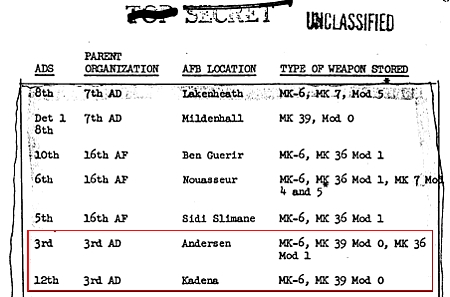

The report contains several claims about Chinese nuclear forces and recommendations for counter-steps that appear out of sync with what the US intelligence community has stated and steps that the US has already taken. Some of the most noteworthy are listed below followed by my remarks:

* “By 2015, China is projected to have in excess of 100 nuclear-armed missiles…that could strike the United States.” Actually, the projection the intelligence community has made in public is for 60 ICBMs by 2010 and “about 75 to 100 warheads deployed primarily against the United States” by 2015. The ISAB report talks about targeting of the US “homeland.” If that includes Guam, then the force could reach a little above 100 by 2015 (it’s about 70 today). If “homeland” means the Continental United States, which has been the focus of the intelligence community’s projection, then a force carrying 75-100 warheads would likely include 20 DF-5As and 40-55 DF-31A. China so far is thought to have deployed fewer than 10 DF-31As.

* Some of the missiles “may be MIRVed” by 2015. What the intelligence community has said is that China has had the capability to MIRV its silo-based missiles for years but has not yet done so. MIRV on the mobile missiles, however, represents significant technical hurdles and “would be many years off,” according to the CIA, and “would probably require nuclear testing to get something that small.” Instead, if Chinese planners determine that the US missile defense system would degrade the effectiveness of the Chinese force, they “could use a DF-31 type RV for a multiple-RV payload for the CSS-4 in a few years,” the CIA stated in 2002. Even so, a multiple-RV payload is not necessarily the same as MIRV.

* China’s “substantial expansion” of its nuclear posture “includes development and deployment of…tactical nuclear arms, encompassing enhanced radiation weapons, nuclear artillery, and anti-ship missiles.” That would certainly be news if it were true, but the intelligence community hasn’t talked much about Chinese tactical nuclear weapons and what it has said has been contradictory, ranging from China might have some to “there is no evidence” that they have any. Several of China’s tests reportedly involved enhanced radiation or tactical warhead designs, but whether China is working on fielding tactical nuclear weapons has not been confirmed. China did conduct what appeared to be operational tests of tactical bombs in the past, which they might have fielded, but ISAB does not mention bombs.

* China’s modernization includes “a growing capability for Conventional Precision Strike and other anti-access/area-denial capabilities” including “submarine-launched ballistic missiles.” That China would use nuclear missiles on its future strategic submarines for “anti-access/area-denial” capabilities is news to me and would, if it were true, represent a dramatic change in Chinese nuclear policy. But I haven’t seen anything that suggests its true, and the overwhelming expectation is that China will use its SSBNs as a retaliatory strike force, if and when they manage to operationalize it.

* The US “should reaffirm its formal security guarantees to allies, including the nuclear umbrella.” The US does that regularly when it extends the security agreement with South Korea and Japan. In addition, in response to the North Korean nuclear test in October 2006, President Bush reaffirmed that “The United States will meet the full range of our deterrent and security commitments.” One week later, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice arrived in Tokyo where she emphasized the nuclear component by saying that “the United States has the will and the capability to meet the full range – and I underscore full range – of its deterrent and security commitments to Japan.”

* The US should “pursue new missile defense capabilities, including taking full advantage of space,” to counter China’s growing nuclear capability. For a State Department advisory committee to recommend using missile defenses to counter Chinese nuclear missiles is, to say the least, interesting given that the State Department has publicly stated and assured the Chinese that the missile defense system “it is not directed against China.”

* The US should “publicly reaffirm its commitment to retain a forward-based US military presence in East Asia.” The US has actually done that quite explicitly over the past seven years by shifting the majority of its aircraft carrier battle groups and nuclear attack submarines to bases in the Pacific, by beginning to forward deploy nuclear attack submarines to Guam, by sending strategic B-2 and B-52 bombers on extended deployments to Guam, and by forward deploying the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN-75) to Japan. The Pentagon describes the recent Valiant Shield exercises as “the largest Pacific exercise since the Vietnam War.”

|

Pacific Exercises Now Biggest Since Vietnam War |

|

| While ISAB recommends increasing the US military posture in the Pacific to counter China, the Pentagon says recent exercises, including the thee carrier battle group Valiant Shield 06, are now the largest since the Vietnam War.

|

.

* “For almost two decades, the United States has allowed its nuclear posture – its stockpile, infrastructure, and expertise – to deteriorate and atrophy across the board.” Although the stockpile is much smaller compared with the Cold War and industrial-scale production of new nuclear warheads has ceased, ISAB’s characterization of the US nuclear posture is way off.

Instead, during the nearly two decades the authors describe (assuming that means since 1990), the US has deployed eight new SSBNs, deployed 336 Trident II D-5 SLBM on its entire SSBN fleet, deployed 21 B-2 stealth bombers, deployed the Advanced Cruise Missile, deployed the hard-target kill W88 warhead (including in the Pacific), deployed three modified nuclear weapons (B61-10, B61-11 and W76-1), completely overhauled the Minuteman III ICBM force, deployed two new classes of nuclear-powered attack submarines capable of launching nuclear cruise missiles, deployed a modern nuclear command and control system with new satellites and command centers, modernized the Strategic War Planning System (now called ISPAN), created a “living SIOP” strategic nuclear war plan with broadened targeting against China and new strike options against regional adversaries, and built a multi-billion dollar Science Based Stockpile Stewardship Program to certify the reliability of the nuclear stockpile without nuclear testing and provide weapons designers with unprecedented knowledge about warhead aging and the skills and tools to refurbish existing warheads or build modified ones.

Where Are The Non-Military Policy Recommendations?

One of the most striking features of the report is its almost complete focus on military options and the absence of other policy components. It contains no analysis of or recommendations for how to engage China on nuclear arms control or confidence building measures to limit or influence the nuclear modernization, operations and policy. It is almost as if there must be another unknown chapter to the report.

Although the authors believe there are a number of measures the US should take to reduce the prospect for misunderstanding and the chance of miscalculation, those recommendations are few and limited to continuing existing Track II discussions, military-to-military contacts, and asking the Chinese to be more transparent.

The report concludes that China does not desire a conflict with the United States, and describes a disconnect between the political and military leadership, and a “clear paranoia and misperceptions about US intentions….” Without presenting any analysis, it concludes that the US ability to shape or change Chinese choices related to its strategic modernization may be “very constrained” and that there is no point in trying to “educate” the Chinese.

On the contrary, the report concludes that the US should “reject” Chinese arms control proposals because they will constrain US military freedom. And US arms transfer to allied countries in the region “should be an important dimension of US non-proliferation policy.” Indeed, the “most important” policy recommendation is for the United States to “demonstrate its resolve to remain militarily strong….”

And in a recommendation blatantly “imported” from the Cold War, the authors say the US should “focus” its research and development on “high technology military capabilities” that China doesn’t have to “demonstrate to Beijing that trying to get ahead of the United States is futile (much the way SDI did against the Soviet Union.”

The report essentially capitulates on non-military policy options toward China.

So What Exactly Was ISAB Asked To Do?

The advisory board was asked to come up with ideas that could “move the US-China security relationship toward greater transparency and mutual confidence, enhance cooperation, and reduce the likelihood of misunderstanding or miscalculation that can contribute to competition or conflict.” That’s a quote!

Instead, the authors appear to have produced a paper that would – if implemented – likely move the US-Chinese security relationship in the opposite direction by deepening military competition and mistrust.

Indeed, the review looks more like the kind one would expect from the Pentagon rather than the State Department, which is supposed to pursue a wider set of policies and different agenda than the military. It is all the more striking given that the charter for ISAB – which used to be called the Arms Control and Nonproliferation Advisory Board (ACNAB) – describes that the board is supposed to “advise with and make recommendations to the Secretary of State on United States arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament policies and activities.”

The Secretary’s hope has been for ISAB to provide “independent insight, advice, and innovation,” and serve as “a single advisory board, dealing with scientific, military, diplomatic, political, and public diplomacy aspects of arms control, disarmament, international security, and nonproliferation, would provide valuable independent insight and advice….”

Concluding Remarks

The militaristic focus of ISAB’s report and its lack of recommendations for arms control and broader public diplomacy to defuse rather than continuing and deepening the competitive and mistrustful relationship between the United States and China suggest that ISAB has failed to live up to its charter.

No matter what one might think of China’s military modernization, the ISAB appears instead to have drawn up a very effective plan for a Cold War with China.

Although the authors correctly state up front that the US-Chinese relationship “differs fundamentally from the US-Soviet relationship and the strategic rivalry of the Cold War,” they nonetheless land on a set of recommendations and observations that strongly resemble a China-version of the Reagan administration’s aggressive military posture against the Soviet Union.

If implemented or allowed to color US policy toward China, the policy recommendations would continue and very likely lead to a deepening of military competition and adversarial relationship between the United States and China – exactly the opposite of what the Board was asked to come up with. It is precisely reports like this that create the “deep paranoia and misperceptions about US intentions” in the Chinese military.

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice should denounce the ISAB report to make it clear that the core of US policy toward China is not containment and Cold War posturing. And one of the first acts of the next Secretary should be to appoint a new advisory board that can – and will – develop recommendations that can “move the US-China security relationship toward greater transparency and mutual confidence, enhance cooperation, and reduce the likelihood of misunderstanding or miscalculation that can contribute to competition or conflict.” Mission not accomplished!

Background Information: ISAB Report: China’s Strategic Modernization | Chinese Nuclear Forces 2008 | US Nuclear Forces 2008 | FAS/NRDC Report: Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning

Nuclear Policy Paper Embraces Clinton Era “Lead and Hedge” Strategy

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new nuclear policy paper National Security and Nuclear Weapons in the 21st Century published quietly Tuesday by the Defense and Energy Departments embraces the “lead and hedge” strategy of the first Clinton administration for how US nuclear forces and policy should evolve in the future.

Yet the “leading” is hard to find in the new paper, which seems focused on hedging.

Instead of offering different alternative options for US nuclear policy, the paper comes across as a Cold War-like threat-based analysis that draws a line in the sand against congressional calls for significant changes to US nuclear policy.

Strong Nuclear Reaffirmation

The paper presents a strong reaffirmation of an “essential and enduring” importance of nuclear weapons to US national security. Russia, China and regional “states of concern” – even terrorists and non-state actors – are listed as justifications for hedging with a nuclear arsenal “second to none” with new warheads that can adapt to changing needs.

Even within the New Triad – a concept presented by the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review as a way to decrease the role of nuclear weapons and increasing the role of conventional weapons and missile defense – the new paper states that nuclear weapons “underpin in a fundamental way these new capabilities.”

In defining the role of nuclear weapons, the paper borrows from and builds on statements, guidance and assertions about the role of nuclear weapons issued by the Clinton and Bush administrations during the past 15 years. This consensus seeking style presents a strong reaffirmation of the continued importance – even prominence – of nuclear weapons in US national security.

Threat-Based Analysis After All

Officials have argued for years that US military planning is no longer based on specific threats and that the security environment is too uncertain to predict them with certainty. But there is nothing uncertain about who the threats are in this paper, which seems to place renewed emphasis on threat-based analysis. The earlier version from 2007 did not mention Russia and China by name, but both countries and their nuclear modernizations are prominently described in the new paper.

Russia is said to have a broad nuclear modernization underway of all major weapons categories, increased emphasis on nuclear weapons in its national security policy and military doctrine, possess the largest inventory of non-strategic nuclear weapons in the world, and re-incorporated theater nuclear options into its military planning. This modernization, resumption of long-range bomber patrols, threats to target US missile defense systems in Europe with nuclear weapons, have created “considerable uncertainty” about Russia’s future course that makes it “prudent” for the US to hedge.

China is said to be the only major nuclear power that is expanding the size of its nuclear arsenal, qualitatively and quantitatively modernizing its nuclear forces, developing and deploying new classes of missiles, and upgrading older systems. The paper repeats the assessment from the 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review that “China has the greatest potential to compete militarily with the United States and field disruptive technologies that could, over time, offset traditional U.S. military advantages.” To that end, the paper indirectly points to China as having influenced the US force level planned for 2012 in “retaining a sufficient margin over countries with expanding nuclear arsenals….”

Regional “states of concern” – formerly known as rogue states – with (or developing) weapons of mass destruction are also highlighted in the paper as an enduring mission for US nuclear weapons. This broadened role for US nuclear weapons, which evolved during the 1990s and in 2003 led to incorporation of nuclear strike options into the US strategic war plan, focuses on Iran, North Korea and Syria. But the paper warns that a significant change in the “alignment among states of concern” in the future may require “adjustments to US deterrent capabilities.”

“Violent extremists and non-state actors” – commonly known as terrorists – are also listed as potential missions for US nuclear weapons. Most analysts agree that terrorists cannot or do not need to be affected by nuclear threats, so the paper instead declares that it is US policy “to hold state sponsors of terrorism accountable for the actions of their proxies.”

In addition to these potential threats, the paper describes how regional dynamics lead other nations, “such as India and Pakistan, to attach similar significance to their nuclear forces.” Israel is not mentioned in the paper.

And if all of this fails to impress, the paper also includes France and the United Kingdom to show that they have already committed themselves to extending and maintaining modern nuclear forces well into the 21st century.

These trends “clearly indicate the continued relevance of nuclear weapons, both today and in the foreseeable future,” the paper concludes. Therefore, it asserts, it is prudent that the United States maintains a viable nuclear capability that is “second to none” well into the 21st century.

Sizing a “Second to None” Nuclear Arsenal

“Second to none” means a US arsenal that is better than Russia’s arsenal. At the same time, the paper states that the criteria for sizing the US arsenal “are no longer based on the size of Russian forces and the accumulative targeting requirements for nuclear strike plans.” This has been said before and has confused many; some officials have even claimed that target plans do not affect the size of the arsenal at all. So the paper adds a lot of new information – probably the most interesting and valuable part of the paper – to clarify the situation:

| “Prior to the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review, force sizing considerations were based on target defeat criteria with the objective of rendering a nuclear-armed adversary incapable of prosecuting conflict, and terminating any conflict on terms favorable to the United States. U.S. Forces were sized to defeat all credible nuclear-armed adversary targets, and the United States retained a small reserve to ensure sufficient capability to deter further aggression in any post-exchange, post-conflict environment. Weapons were dedicated to specific targets, and the requirements for target defeat did not change dramatically year-to-year….” The 2001 NPR “made distinctions among the contingencies for which the United States must be prepared. These contingencies were categorized as immediate, potential, or unexpected….” “Instead, the size of the U.S. nuclear force is now based on the ability of the operationally deployed force, the force structure, and the supporting nuclear infrastructure to meet a spectrum of political and military goals. These considerations reflect the view that the political effects of U.S. strategic forces, particularly with respect to both central strategic deterrence and extended deterrence, are key to the full range of requirements for these forces and that those broader goals are not reflected fully by military targeting requirements alone.” |

.

Still confused? What I think they are trying to say is that the target sets for some contingencies no longer have to be covered by operationally deployed nuclear warheads on a day-by-day basis.

What has permitted this change is not a deletion of strike plans against the Russian target base per ce (which has shrunk considerably since the 1980s), but rather the extraordinary flexibility that has been added to the nuclear planning system and the weapons themselves over the past decade and a half. This flexible targeting capability – which ironically was started in the late 1980s in an effort to hunt down Soviet mobile missile launchers – has since produced a capability to rapidly target or retarget warheads in adaptively planned scenarios. Put simply, it is no longer necessary to “tie down” entire sections of the force to a particular scenario or group of targets (although some targets due to their characteristics necessitate use of certain warheads).

The more flexible war plan that exists today, which the 1,700-2,200 operational deployed strategic warhead level of the SORT agreement is sized to meet, is “a family of plans applicable to a wider range of scenarios” with “more flexible options” for potential use “in a wider range of contingencies.” And although they are no longer the same kind of strike plans that existed in the 1980s, some of them still cover Russia to meet the guidance of the Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy document from 2004:

| “U.S. nuclear forces must be capable of, and be seen to be capable of, destroying those critical war-making and war-supporting assets and capabilities that a potential enemy leadership values most and that it would rely on to achieve its own objectives in a post-war world.” |

.

Concluding Observations

The political motivation for this paper is Congress’ demand for a comprehensive review of US nuclear policy before considering whether to approve industrial-scale production of new nuclear warheads. To that end, the paper presents the Defense and Energy department’s nuclear weapons requirement “logic” in an attempt to create a basis for anyone who is considering changing US nuclear weapons policy, strategy, and force structure.

The paper says the US has already made “historic reductions” in its deployed nuclear forces – a fact given the Cold War only happened once and has been over for two decades – and comes tantalizingly close to acknowledging that the warhead level set by the SORT agreement essentially is the START III level framework agreed to by Presidents Clinton and Yeltsin in Helsinki in 1997.

Indeed, by closely and explicitly aligning itself with policies pursued by the Clinton and first Bush administrations, the paper seeks to tone down the controversial aspects of the current administration’s nuclear policy and portray it as a continuation of long-held positions. Whether that will help ease congressional demands for change remains to be seen.

Yet for a paper that portrays to describe the role of nuclear weapons “in the 21st century” – a period extending further into the future than the nuclear era has lasted so far – is comes across as strikingly status quo. A better title would have been “in the first decade of the 21st century.”

It offers no options for changing the role of nuclear weapons or reducing their numbers beyond the SORT agreement – it even states that “no decisions have been made about the number or mix of specific warheads to be fielded in 2012.” The only option for reducing further, the paper indicates, is if Congress approves production of new nuclear warheads (including the RRW that Congress has rejected) that can replace the current types. And even that would require a production far above the currently planned level.

The central message of the paper seems to be that two decades of nuclear decline is coming to an end and that all nuclear weapon states will retain, prioritize, and modernize their nuclear forces for the indefinite future. The US should follow their lead, the paper indicates, and “maintain a credible deterrent at these lower levels” for the long haul. To do that, the United States needs nuclear forces “second to none” “that can adapt to changing needs.”

Background Information: National Security and Nuclear Weapons in the 21st Century | US Nuclear Forces 2008 | 2001 Nuclear Posture Review Report (reconstructed)

War in Georgia and Repercussions for Nuclear Disarmament Cooperation with Russia

In an earlier blog post, arguments were discussed from a 12 June 08 meeting of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs for and against the signing of a civilian nuclear cooperation agreement (123 Agreement) with Russia. At the time, the most salient issues were our ability to influence Russia’s position vis-à-vis Iran’s nuclear ambitions and the possibility that the 123 Agreement would restart domestic reprocessing, reversing 30 years of US policy. Since then, a full scale military operation has taken place between Russia and Georgia, a newly democratic ally of the U.S. who sent 2,000 troops to support U.S. efforts in Iraq. Now both Russian and American leaders want to remove the 123 Agreement from consideration for the time being, so as not to allow current events to color any debates about passing the legislation. Those in favor of the 123 Agreement believe that it would open up greater cooperation with Russia on issues such as pressuring Iran on its nuclear program. Whether this is true or not, if the 123 Agreement is now off the table because of Russia’s actions in Georgia, how much has this conflict damaged our ability to cooperate with Russia on nuclear arms control in the future? (more…)

Presidential Candidates Need to See Beyond Warhead Numbers

By Hans M. Kristensen and Ivan Oelrich

Barack Obama has put forward an inspiring nuclear security policy that promises to reinstate nuclear disarmament as a central goal of U.S. national security and foreign policy. This vision has been shared by all presidents since the Cuban Missile Crisis, except for George W. Bush.

If he is elected the next president, Obama’s policy would be a refreshing break with the gung-ho and divisive policies that have characterized the current administration.

Even so, it is important to consider the intent of Obama’s policy and look ahead to how it could be implemented and even improved.

The Role of Nuclear Weapons

The part of the policy that deals with existing nuclear weapons (versus proliferation) is very much focused on numbers. When both the United States and Russia clearly have far, far more nuclear weapons than either could conceivably need, it is tempting to ignore details and just make big cuts in numbers. But to move the process convincingly toward diminishing the salience – and eventually toward abolition – of nuclear weapons it is necessary to develop a vision for what role the nuclear weapons should play in U.S. national security policy. Short of some very general statements, Presidents traditionally leave this matter to the Secretary of Defense and the National Security Council. This practice has gotten us into a lot of trouble in the past as policy and military planners transformed vague presidential guidance into excessive and dangerous nuclear postures.

Other than a pledge to negotiate with Russia about ending high alert of nuclear weapons, there is nothing in Obama’s policy that suggests the role of nuclear weapons would be any different under him than under Bush or Clinton. Clearly, this is a shortcoming of his proposal. Statements from Senator McCain are even more worrying: he has said he will ask the military for a review and to report back on the minimum number needed, implying quite clearly that the military, not the president, will make important decisions about what role nuclear weapons ought to have.

The (first) Bush and Clinton administrations significantly changed the role of U.S. nuclear weapons from deterring and destroying Soviet and Chinese nuclear and large-scale conventional forces to deterring use and acquisition of all forms of weapons of mass destruction in all adversarial countries with such capabilities. Moreover, in response to 9/11, the Bush administration rushed forward a highly aggressive preemption doctrine that included nuclear strikes.

To change the role of nuclear weapons requires direct, sustained intervention by the next president. Therefore, both Senators Obama and McCain need to think hard about what his guidance would be on such issues as:

* Should the United States abandon its current policy of deterring all forms of weapons of mass destruction and only use nuclear weapons to deter use of nuclear weapons?

* Should the United States adopt a no-first-use policy or is it still necessary to retain the option to strike first?

* Should the United States retain counterforce targeting, return to countervalue targeting, or develop another concept for what facilities to target with nuclear weapons?

* Should the United States significantly lower and change the damage expectancy required for nuclear strikes?

* Should the United States abandon its policy of being capable of holding all potential targets at risk or is a more limited range sufficient today?

* Should the United States discontinue the practice of having nuclear weapons operationally deployed – including operating daily under a fully executable plan – or could sufficient deterrence be retained by a far less operational posture?

* Should the United States complete the 1991-1992 reductions and withdraw the remaining tactical nuclear weapons from Europe and instead rely on long-range weapons to provide a nuclear umbrella to our NATO allies?

|

No to No-First-Use |

|

|

Defense Secretary William Cohen of the Clinton administration rejected a no-first-use policy. Will an Obama administration be any different? |

If the next president doesn’t address such fundamental policy issues in his first guidance, the outcome of the next Nuclear Posture Review will almost certainly be little more than status quo at lower levels, leaving in place a posture of excessive nuclear capabilities that the United States doesn’t need but which locks it into a warfighting deterrence posture that works against a vision for deep cuts and disarmament.

The End Goal

The component of Obama’s policy that deals with deep nuclear cuts and disarmament comes with important caveats. One is a pledge to “maintain a strong deterrent as long as nuclear weapons exist,” a position the Bush administration also shares, but which presents a particular conundrum for a policy that seeks nuclear disarmament: if all nuclear weapon states insist on having nuclear weapons as long as nuclear weapons exist, how can we ever get to zero? That would leave U.S. nuclear policy (and nuclear disarmament) hostage to any country that had just one nuclear weapons, even if our conventional capabilities are more than sufficient to deter anyone who can be deterred (Iran and North Korea being obvious examples).

At some point in the process, some of the nuclear weapon states – eventually all – have to be prepared to relinquish the weapons. This is not unheard of; Belarus, Kazakhstan, South Africa and Ukraine have already gone to zero. A “disarmament-president” has to think this conundrum carefully through.

Getting to deep cuts and certainly to global elimination of nuclear weapons might require wholesale revision of the role that military forces play in the world. The national security of the United States – and many other large military powers – is deeply rooted in a military posture aimed at threatening other countries if they do things we don’t like.

|

“As Long As |

|

|

Would an Iran with a few nuclear weapons prevent the United States and others from going to zero even though they have overwhelming conventional capabilities? |

It is very hard see why other nuclear powers – some of which are our or other nuclear powers’ potential adversaries – would agree to move beyond deep cuts to actual nuclear disarmament as long as the United States pursues military superiority and unconstrained forward offensive operations. Would Russia and China agree to deep nuclear cuts when we’re developing conventional prompt global strike long-range weapons with hard target kill capability that can threaten their remaining forces?

Would Japan agree to the United States eliminating the nuclear umbrella as long as China modernizes and builds up it conventional capabilities? Would Israel agree to disarmament as long as they are surrounded by conventionally armed potential enemies?

Many government and military officials therefore effectively dismiss disarmament by saying: not until there is peace and brotherhood among men. In other words, certainly not in our lifetime or that of our children. Obama’s policy to some extend acknowledges this with a second caveat by talking about the “long road” toward elimination of nuclear weapons.

Ideally, these threats and insecurities must be addressed in a broader context of the relations between states and of the legitimacy of force but, no, all the world’s security problems do not have to be solved before we can consider the elimination of nuclear weapons. Three points are important particularly from a U.S. perspective.

First, there is no need to give some fifth-rate country like North Korea a veto over U.S. nuclear policy. North Korea may very well be developing nuclear weapons to deter the United States but that does not mean the United States, with overwhelming conventional military superiority, needs to have nuclear weapons to deter North Korea, even North Korea’s nuclear use.

Second, the nuclear disarmament of the big nuclear powers will make the nuclear disarmament of troublesome regimes like Iran and North Korea easier, not harder. Some Iranians talk of their nuclear program making them a “world power,” a conceit that would be completely laughable except the established nuclear powers do, in fact, often attach such significance to simply owning nuclear weapons. Delegitimizing nuclear weapons reduces their appeal. North Korea provides a different example: the United States, China, and Russia publicly claim that North Korea’s nuclear weapon program is intolerable, a concern that has only slowly impressed itself on the North Koreans. But imagine that China, the North’s only real patron, had eliminated its own weapons; would the Chinese tolerate their tiny neighbor’s nuclear program then?

Third, and probably most important, while global nuclear disarmament may depend on significant changes in the world’s attitudes toward the use and legitimacy of force, working toward nuclear disarmament can do much to bring about those very changes. Short of willingness to jumpstart the process by taking bold unilateral steps like big reductions in warhead numbers and success in changing the mindsets of all the nuclear powers and their allies, the “long road” might be very long indeed.

Despite these shortfalls, the nuclear policy Obama has put forward would, if it became U.S. policy, be a huge step forward in restoring traditional U.S. nuclear policy priorities and curtailing the role and salience of nuclear weapons in the world. By addressing the issues we have described, it could even be the beginning of the end for nuclear weapons.

Background: Obama’s Plan for a 21st Century Military | Missions for Nuclear Weapons After the Cold War

STRATCOM Cancels Controversial Preemption Strike Plan

|

|

The controversial preemption strike plan CONPLAN 8022 has been canceled and the mission instead merged with the main U.S. strategic war plan. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. military has canceled a controversial war plan designed to strike adversaries promptly – even preemptively – with conventional and nuclear weapons. The strike plan was known as Concept Plan (CONPLAN) 8022 and first entered into effect in the summer of 2004 to provide the president with a prompt, global strike capability against time-urgent and mobile targets.

CONPLAN 8022 was the first attempt to operationalize the “Global Strike” mission assigned to U.S. Strategic Command in January 2003. The mission was triggered by new White House guidance following the terrorist attacks in September 2001 and fear of proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

Lack of leadership and definition has since placed Global Strike in limbo, with little progress and prompt effects instead being incorporated into other existing strike plans. “Global Strike” is now described as a much broader mission synonymous with the “New Triad” first articulated by the Bush administration’s 2001 Nuclear Posture Review.

CONPLAN 8022’s Short Life

Like its mission, CONPLAN 8022’s life was prompt and brief. STRATCOM completed the first version of the plan in November 2003, based on White House and Pentagon guidance issued in response to 9/11. The requirement was to develop a plan that could be used to strike high-value and mobile weapons of mass destruction (WMD) targets quickly with conventional or nuclear weapons before they could be used against the United States and its allies.

The Global Strike mission was formally assigned to STRATCOM in January 2003 and, in June 2004, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and CJCS General Richard Myers issued the “Alert Order” that ordered STRATCOM to put CONPLAN 8022 into effect. In July 2004, STRATCOM commander General E. Cartwright reported to Congress that Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld had “just signed the Interim Global Strike Alert Order, which provides the President a prompt, global strike capability” (see Global Strike Chronology for more details).

|

Figure 1: |

|

|

One of General James Cartwright’s (left) first acts after taking over as commander of STRATCOM in July 2004 was to withdraw CONPLAN 8022, developed by his predecessor Admiral James Ellis (right). |

Shortly after CONPLAN 8022 was brought up to full operational status, however, General Cartwright “withdrew” the plan in the fall of 2004, according to a document provided by STRATCOM in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. It is still murky what the term “withdrawn” implies, because several public documents and personal communication with STRATCOM continued to refer to CONPLAN 8022 after the fall of 2004. Cartwright has since declined to explain why he “withdrew” the plan, but his public statements in 2004-2006 suggest that he was concerned that the only actual prompt weapons in the plan were nuclear, and that this was not a credible posture.

As a concept plan, moreover, CONPLAN 8022 was not intended to be in effect continuously but designed to be brought into effect if necessary. After the plan was brought up to full operational status in 2004, it is possible that CONPLAN 8022 was “withdrawn” or returned to concept status once more. As of March 2006, STRATCOM told me, the plan “was still in its original version, with no revisions.”

But a year later, in July 2007, STRATCOM informed me that CONPLAN “8022 doesn’t exist.” When asked if the plan had been canceled or just deactivated, the officer said “there is no such plan anymore.” It “was underway, but didn’t go anywhere.”

|

Figure 1: |

|

|

Even slow bomber deployments, like this B-2 deploying to Guam in 2006, are described as “Global Strike.” |

Global Strike Confusion

After cancellation of CONPLAN 8022 there has been significant confusion about what Global Strike actually is. After initially being “sold” as an urgent, unique and separate mission for limited, short-duration, quick-strike options against high-value and mobile targets not covered by other existing plans, Global Strike is now described as many things, ranging from Special Operations Forces raids (boots on the ground) to the traditional nuclear posture of long-range strategic nuclear weapons. Even slow bomber deployments are called Global Strike these days (see Figure 1 and 2; for an example of a recent Global Reach mission described as Global Strike, go here).

Some call it Global Strike, others call it Prompt Global Strike, while others again call it Conventional Prompt Global Strike, depending on who is talking and what weapon program is being promoted. General Cartwright sometimes tried to clarify the structure by saying Prompt Global Strike was a conventional subset of Global Strike, which was a subset of the strategic war plan. But his efforts seem to have had little impact on the debate.

|

Figure 3: |

|

|

Slow B-52 bomber have conducted several Global Strike exercises, such as this quick-launch practice at Minot AFB in 2007, even though the platform is clearly not a prompt weapon. |

A recent GAO report found that the different Services and agencies have very different understandings of what Global Strike means. The varied interpretation of Global Strike, GAO concluded, “affects their ability to clearly distinguish the scope, range, and potential use of capabilities needed to implement global strike and under what conditions global strike would be used in U.S. military operations.” In response to the GAO findings, STRATCOM agreed to “develop a common, universally accepted concept and definition for ‘Global Strike’.”

Congress has been generally reluctant to fund new exotic weapons for the Global Strike mission. Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) planning has identified, according to GAO, 94 program elements that would provide funding for 135 programs, projects, and activities having possible application for Global Strike. But for now, more than five years after STRATCOM was assigned the Global Strike mission, the Department of Defense concedes that “global strike, as a validated and executable concept, has not matured to the point that it is an extant executable capability….”

Unfortunately, the GAO report only discusses the conventional aspects of Global Strike, even though it was the nuclear option that originally triggered Congressional interest in the mission. After I disclosed in 2005 that preemptive global strike options were being incorporated into a revision of the Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations (JP 3-12), more than a dozen members of Congress – including Ellen Tauscher and Jack Reed – objected in a letter to the president to what they considered to be a dangerous change of U.S. nuclear policy. Yet the nuclear option today remains the only executable prompt component of Global Strike.

“Global Strike” or just global strike

Despite the cancellation of CONPLAN 8022 and confusion over the Global Strike mission, however, planning for quick-reaction, short-duration strikes against high-value and fleeting (mobile) targets has continued at STRATCOM, officials confirm.

Instead of a separate CONPLAN, the Global Strike mission is being incorporated into the existing strategic war plan known as OPLAN 8044, offered to regional combatant commanders, and can probably also be found in the new Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction plan known as CONPLAN 8099. The combat employment portion of OPLAN 8044, previously called the SIOP (Single Integrated Operational Plan), was renamed in 2003 to reflect that the “single” top-heavy SIOP has been taken apart and converted into “a family of plans.” Compared with the SIOP, OPLAN 8044 includes “more flexible options” for potential use in a “wider range of contingencies,” according to military documents.

The “family of plans” is the result of a reorganization that has been underway since the early 1990s, when STRATCOM began to create “adaptive planning” missions tailored against rogue states armed with WMD. Back then, the first STRATCOM commander General George Lee Butler described how the SIOP was “evolving to a collection of far more differentiated retaliatory choices, tailored to a threat environment of greater nuance and complexity.”

The Bush administration adopted “tailored” as a central planning objective in its 2001 Nuclear Posture Review that ordering the development of a “New Triad” with more strike capabilities and options. Curiously, the offensive leg of the “New Triad” with its nuclear, conventional and non-kinetic strike capabilities has now become synonymous with Global Strike. Before CONPLAN 8022 was withdrawn, the Pentagon’s Strategic Deterrence Joint Operating Concept, for which STRATCOM was the lead agent, portrayed Global Strike as separate from nuclear strike capabilities (although it wasn’t). In the updated version from December 2006, however, Global Strike is portrayed as synonymous with the offensive leg in the New Triad (see figure 1).

|

Figure 4: |

|

|

|

| “Direct Means” list (2004): – Force projection – Nuclear strike capabilities – Active and passive defenses – Global Strike – Strategic deterrence information operations – Inducement operations – Space control |

“Direct Means” list (2006): – Force projection – Active and passive defenses – Global Strike (nuclear, conventional, non-kinetic) – Strategic communications |

| Nuclear and non-nuclear offensive weapons have been merged under Global Strike in the 2006 STRATCOM-led Joint Operating Concept. The 2004 version, by contrast, listed the capabilities as separate. In the 2006 revision, however, the Global Strike mission description begins with nuclear and appear synonymous with the offensive leg of the “New Triad.” | |

To implement, maintain and execute the Global Strike mission, STRATCOM established the Joint Functional Component Command for Space and Global Strike (later changed to Joint Functional Component Command for Global Strike and Integration, JFCC GSI). The Concept of Operations document for the new command shows that its responsibilities reach far beyond Global Strike to all strategic strike planning for OPLAN 8044. Through JFCC GSI, STRATCOM is transforming its formerly secluded strategic nuclear strike enterprise into an integrated planning and strike service for national-level and regional combatant commanders. For JFCC SGI, that means integrating STRATCOM’s global strike capabilities into theater operations. A separate CONPLAN 8022 and OPLAN 8044, by contrast, would have constituted separation of planning.

STRATCOM’s current fact sheet on JFCC GSI – all that has survived from several pages previously posted on the command’s web site – shows a component command that has responsibility for the full range of strike capabilities in a planning architecture with Global Strike intertwined with traditional deterrence.

Some Implications

The Global Strike mission was launched with much fervor on the heels of a new preemption strategy following the 2001 terrorist attacks. But it is hard to take seriously the claim that Global Strike – meaning unique prompt strike capabilities other than those already in the inventory – is essential for national security when, more than five years after the mission was established, the Pentagon still hasn’t developed an executable capability or even a succinct definition for what Global Strike means.

In hindsight it seems that rather than developing a unique preemptive plan, planners have instead incorporated the concept into the remnants of the strategic war plan. This “integration” has become the guiding principle for military planning despite its slow start, and has reinvigorated the strategic planning community by creating requirements for an increased number of strike options and contingencies.

Mixed in with this morass of increasingly diffuse global strike capabilities are nuclear weapons, which ought to be clearly and unequivocally identified as a last resort that is separate from the dynamic Global Strike mission. The GAO report notes that “nuclear systems would be part of the portfolio” but doesn’t examine this part of Global Strike. Hopefully Congress’ Strategic Posture Review Commission and the next administration’s Nuclear Posture Review will.

Background information: Global Strike Chronology | Global Strike Concept of Operations | GAO: Strengthen Implementation of Global Strike

The RISOP is Dead – Long Live RISOP-Like Nuclear Planning

|

| Launch control officers at Minot Air Force Base practice launching their high-alert ICBM. But the hypothetical Russian nuclear strike plan that originally led to the requirement to have nuclear forces on alert has been canceled. So why are the ICBMs still on alert? |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

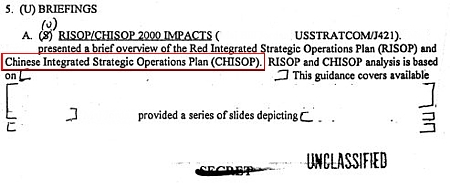

The U.S. military has canceled the Red Integrated Strategic Offensive Plan (RISOP), a hypothetical Russian nuclear strike plan against the United States created and used for decades by U.S. nuclear war planners to improve U.S. nuclear strike plans against Russia.

The cancellation appears to substantiate the claim made by Bush administration and military official, that the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review removed Russia as an immediate contingency for U.S. nuclear strike planning. But implementing the shift was not a high priority, lasting almost the entire first term of the administration.

Despite the shift, however, declassified documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act also show that RISOP-like and “red” analysis continues, and that that the cancellation was necessary to allow STRATCOM to broaden nuclear strike planning beyond Russia.

A Brief RISOP History

The RISOP dates back to the 1960s shortly after the first SIOP (Single Integrated Operational Plan), the Cold War name for the overall U.S. strategic war plan. An important element of refining and improving the effectiveness of the SIOP was to “wargame” it against the Soviet Union and more recently Russia. To do that, planners at Joint Staff and Strategic Air Command (SAC) developed a hypothetical Soviet War plan based on the latest intelligence about Soviet/Russian doctrine, strategy and weapons capabilities. To assist with coordination and planning, Joint Staff established the Red Planning Board (RPB), which included members of all the services and key agencies but was chaired by Joint Staff.

|

Figure 1: |

|

|

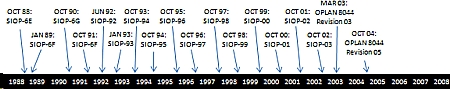

RISOP updates coincided with SIOP updates. The following declassified (heavily redacted) briefings show the content and structure of the 1996, 1997 and 1998 RISOP plans: * Joint Staff RISOP-96 Brief, April 1995 |

RISOP was based on the latest intelligence about Soviet/Russian nuclear strategy and forces, but the declassified documents show that Joint Staff and STRATCOM did not consider it an intelligence appraisal of those capabilities. Nor did it represent a judgment on the most likely Russian geopolitical intentions. Instead, RISOP was described as one of many possible and plausible courses of action based on Defense Intelligence Agency estimates of Russia force employment consistent with their military doctrine. But since planners probably didn’t want to wargame SIOP against anything but the “real” threat, RISOP most likely was the best possible estimate of the Russian posture.

RISOP was primarily a U.S. nuclear war planning tool. As a detailed opposing force threat plan, it was used by SAC and later STRATCOM in computer simulations to evaluate updates to the SIOP plan; RISOP updates coincided with SIOP updates. RISOP was also used to conduct force structure, arms control, and continuity of government analysis, and to carry out communications studies and prelaunch survivability computations and other strategic analysis.

The Slow Wheels of Change

Responsibility for production of RISOP was transferred from Joint Staff to STRATCOM in late 1996. The RPB was maintained, however, to ensure, among other things, that STRATCOM didn’t “cook the books,” as one of the declassified briefings put it. But the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) changed the planning assumptions against Russia. Whereas the RISOP plans of the late 1990s (see Figure 1) envisioned Russian nuclear attacks against the United States, its allies, and China, those assumptions were clearly out of sync with the political and military realities in Russia. The NPR instead determined that “a [nuclear strike] contingency involving Russia, while plausible, is not expected,” and that the size of the operational U.S. nuclear arsenal is “not driven by an immediate contingency involving Russia.” Thus, the overall planning assumption shifted from urgent to plausible.

|

Table 1: |

|

Dec 2001: NPR completed

|

But despite statements about the importance of ending the adversarial relationship with Russia, changing the nuclear planning against Russia apparently was not a priority and would have to wait almost the entire first term of the Bush administration. The NPR was completed in late 2001, the NPR Implementation Plan published in March 2003, the new Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy (NUWEP) signed in April 2004, and a new Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan nuclear supplement issued in December 2004, formally removing the requirement for the RISOP. Finally, in February 2005, four years and two months after the NPR, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued the instruction that formally cancelled the RISOP and the RPB (see Table 1).

Despite the policy change toward Russia, the RPB had not made any changes to the RISOP since 1998, following President Clinton’s PDD-60 directive that removed the requirement to plan for protracted nuclear war with Russia. As one Joint Staff official remarked in an email: “Sometimes the wheels of change move slowly.”

The “New” Nuclear Planning

The new planning guidance was laid out in the nuclear supplement to the Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan (JSCP), formally known as CJCSI 3110.04B or JSCP-N (see Figure 2 for earlier JSCP-N), which was published on December 31, 2004. This document instructed STRATCOM to “perform broader campaign level analysis than the previous requirement which focused on the RISOP.” In the words of the RPB, STRATCOM’s “red attack plan may also be broader than the scope of the RISOP.”

|

Figure 2: |

|

|

|

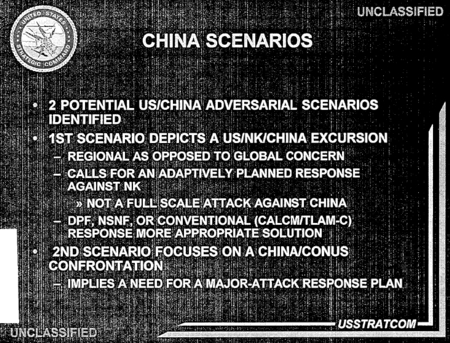

This broadening probably reflects the efforts to expand strike planning beyond Russia with increased focus on China and regional states armed with weapons of mass destruction (WMD). A “notable change” for the strike plan put in effect in March 2003 (OPLAN 8044 Revision 03) included executable strike options against regional states, options that were probably carried forward into the current OPLAN 8044 Revision 05.

Of course, Russia didn’t just disappear from the planning requirements. The NPR itself warned that although the country no longer is considered an immediate contingency, “Russia’s nuclear forces and programs, nevertheless, remain a concern. Russia faces many strategic problems around its periphery and its future course cannot be charted with certainty.” The NPR concluded that “U.S. planning must take this into account.” In addition, the NPR hedged, “in the event that U.S. relations with Russia significantly worsen in the future, the U.S. may need to revise its nuclear force levels and posture.” Relations have certainly not improved.

The previous JSCP-N from January 2000, which was updated in July 2001 (see here for chronology of nuclear guidance), required Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) and Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) to provide information to the Joint Staff for use in RISOP development. But the new JSCP-N moved this role to STRATCOM by directing that DIA and DISA “will support USSTRATCOM directly by providing data for red analysis.” The JSCP-N directs STRATCOM to perform three levels of analysis for the strike plans:

Phase I: Consequence of Execution Analysis

Phase II: Campaign Level Analysis

Phase III: Intelligence Assessment Analysis

Campaign Analysis is “a campaign level analysis to provide a stochastic check of the deterministic models used for the revision report consequences of execution analysis and to assess OPLAN 8044, REVISION XX’s [formerly SIOP] capability to comply with approved guidance. Such analysis will encompass various scenarios and may include the potential contribution of SACEUR’s MCOs [Major Combat Operations] as required.”

Despite the cancellation of RISOP, a 2004 STRATCOM briefing stated, STRATCOM “will continue to produce RISOP-like analysis,” and “procedures for requesting data and providing products will remain the same.” As before, use of the data will support prelaunch survivability analysis for ICBMs and bombers, base survivability of SSBN bases, and command, control and communication vulnerability and survivability analysis. All to ensure that U.S. nuclear forces will survive and endure against any nuclear adversary, including Russia.

Comments

U.S. nuclear forces were placed on high alert to counter the Soviet nuclear threat, and the effectiveness of the strike plan for their potential use continuously refined and improved by wargaming it against the RISOP. Now that Russia is not considered a nuclear threat and the RISOP has been canceled, how long will it be before the alert posture is canceled as well?

The U.S. strategic war plan – OPLAN 8044 Revision 05 – is currently structured around a reduced but more flexible posture with the same overall Triad structure as during the Cold War and over 1,000 nuclear warheads on high alert. Surprisingly, although RISOP was canceled in 2005, no revision has been made to OPLAN 8044 since October 2004 – the first time in U.S. post-Cold War nuclear history that the nation’s strategic war plan has not been overhauled at least once per year (see Figure 3).

|

Figure 3: |

|

| STRATCOM has not published an updated U.S. strategic war plan since October 2004, breaking with a historical pattern of annual overhauls. The change probably reflects development of a new plan structure and more flexible adaptive planning capabilities. |

.

The explanation might be that major overhauls are no longer necessary because today’s plan has become flexible enough to accommodate changes on a ongoing basis without a need for a new revision; a “living SIOP.” OPLAN 8044 now consists of a family of plans applicable in a wider range of scenarios, with more flexible options to defeat adversaries in a wider range of contingencies than during the Cold War. Cancellation of RISOP might have reduced the focus on Russia, but it was also part of a broadening of nuclear strike planning to other potential adversaries.

The s l o w cancellation of the Russian-focused RISOP and the continuation of RISOP-like and red nuclear war planning for a broader and more flexible war plan should be an important lesson for the next president: unless he keeps his eye on the issue and pays continuous attention to how and when the military translates his initial guidance into a myriad of war planning requirements and strike options, the future U.S. nuclear posture – and with it the hope of significantly reducing the role and salience of nuclear weapons in the world – will only change v e r y slowly and not necessarily in the direction he had intended.

Dutch Government Rejects Blue Ribbon Review Findings

|

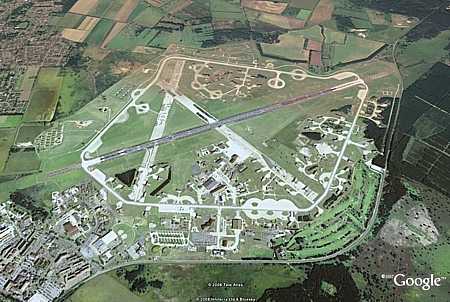

| The nuclear base at Volkel is pixeled out on Google Earth (why, Google?). Click on image to download map of the base (note: 1 MB). Image: GoogleEarth (outline and label added) |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Dutch Government today rejected the findings of the U.S. Air Force’s Blue Ribbon Review, saying the safety and security at the nuclear weapons base at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands “are in good order.”

The Blue Ribbon Review final report in February concluded that “most” nuclear sites in Europe do not meet U.S. safety requirements and that it would take “significant additional resources” to bring them up to standard. The disclosure of the findings has led to calls in some European countries that the remaining tactical nuclear weapons should be withdrawn.

During a meeting earlier today in the Defense Committee of the Dutch Parliament, Defense Minister Eimert van Middelkoop responded to a question from Krista van Velzen (Socialist Party) about the findings of the Blue Ribbon Review:

“Ms. van Velzen asked a question about the American report concerning the storage of nuclear weapons and Volkel. Insofar as this is relevant, safety and security at Volkel are in good order, but the government of the Netherlands does not make any announcements concerning the presence or absence of nuclear weapons embodying that single Dutch nuclear mission.” (unofficial translation)

|

Figure 1: |

|

| Dutch Defense Minister Eimert van Middelkoop (left) met with U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates in October 2007. Afghanistan was on the agenda, but isn’t it time to talk about the withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe? |

.

Although Mr. Middelkoop refused to confirm or deny whether there are nuclear bombs at the base, he did confirm that the Netherlands still has a nuclear mission. It would have been more interesting to hear his explanation for why that mission is still needed. The enemy is gone, the weapons would take “months” to ready for strike, and the U.S. Air Force would like to see the weapons withdrawn. The deployment increasingly looks like nuclear social welfare for a small group of NATO bureaucrats.

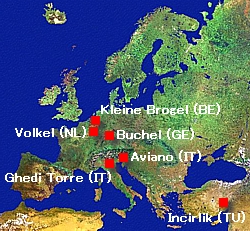

There are an estimated 10-20 U.S. B61 nuclear bombs stored at Volkel Air Base for delivery by Dutch F-16 fighter jets, part of an arsenal of approximately 200 nuclear bombs at six bases in five European countries.

Previous reports: USAF Report: “Most” Nuclear Sites in Europe do not Meet US Security Requirements (FAS, June 2008) | U.S. Nuclear Weapons Withdrawn From the United Kingdom (FAS, June 2008) | United States Removes Nuclear Weapons from German Base, Documents Indicate (FAS, July 2007) | U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe (NRDC, 2005)

U.S. Nuclear Weapons Withdrawn From the United Kingdom

More than 100 U.S. nuclear bombs have been withdrawn from RAF Lakenheath, the forward base of the U.S. Air Force 48th Fighter Wing. Image: GoogleEarth

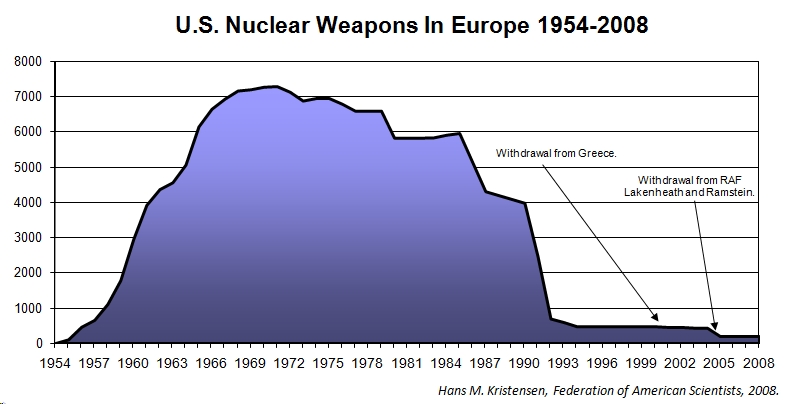

The United States has withdrawn nuclear weapons from the RAF Lakenheath air base 70 miles northeast of London, marking the end to more than 50 years of U.S. nuclear weapons deployment to the United Kingdom since the first nuclear bombs first arrived in September 1954.

The withdrawal, which has not been officially announced but confirmed by several sources, follows the withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base in Germany in 2005 and Greece in 2001. The removal of nuclear weapons from three bases in two NATO countries in less than a decade undercuts the argument for continuing deployment in other European countries.

Status of European Deployment

I have previously described that President Bill Clinton in November 2000 authorized the Pentagon to deploy 110 nuclear bombs at Lakenheath, part of a total of 480 nuclear bombs authorized for Europe at the time.

US Nuclear Weapons in Europe 2008

President George Bush updated the authorization in May 2004, which apparently ordered the withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base in Germany. The withdrawal from Lakenheath might also have been authorized by the Bush directive, or by an update issued within the past three years. This reduction and consolidation in Europe was hinted by General James Jones, the NATO Supreme Commander at Europe at the time, when he stated in a testimony to a Belgian Senate committee: “The reduction will be significant. Good news is on the way.”

Last week I reported that security deficiencies found by the U.S. Air Force Blue Ribbon Review at “most” sites were likely to lead to further consolidation of the weapons, and that “significant changes” were rumored at Lakenheath.

Withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from three European bases since 2001 means that two-thirds of the arsenal is now on the southern flank.

The withdrawal from Lakenheath means that the U.S. nuclear weapons deployment overseas is down to only two U.S. Air Force bases (Aviano AB in Italy and Incirlik in Turkey) plus four other national European bases in Belgium, Germany, Holland and Italy, for a total of six bases in Europe. It is estimated that there are 150-240 B61 nuclear bombs left in Europe, two-thirds of which are based on NATO’s southern flank (see Table 1).

Some Implications

Why NATO and the United States have decided to keep these major withdrawals secret is a big puzzle. The explanation might simply be that “nuclear” always means secret, that it was done to prevent a public debate about the future of the rest of the weapons, or that the Bush administration just doesn’t like arms control. Whatever the reason, it is troubling because the reductions have occurred around the same time that Russian officials repeatedly have pointed to the U.S. weapons in Europe as a justification to reject limitations on Russia’s own tactical nuclear weapons.

In fact, at the very same time that preparations for the withdrawal from Ramstein and Lakenheath were underway, a U.S. State Department delegation visiting Moscow clashed with Russian officials about who had done enough to reduce its non-strategic nuclear weapons. General Jones’ “good news” could not be shared.

While NATO boasts about its nuclear reductions since the Cold War, the Alliance is more timid about the reductions in recent years.

By keeping the withdrawals secret, NATO and the United States have missed huge opportunities to engage Russia directly and positively about reductions to their non-strategic nuclear weapons, and to improve their own nuclear image in the world in general.

The news about the withdrawal from Lakenheath comes at an inconvenient time for those who advocate continuing deployment of U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe. By following on the heels of the withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base in 2004-2005 and Greece in 2001, the Lakenheath withdrawal raises the obvious question at the remaining nuclear sites: If they can withdraw, why can’t we?

What is at stake is not whether NATO should be protected with nuclear weapons, but why it is still necessary to deploy tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. Japan and South Korea are also covered by the U.S. nuclear umbrella, but without tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Asia. The benefits from withdrawing the remaining non-strategic nuclear weapons from Europe far outweigh the costs, risks and political objectives of keeping them there. The only question is: who will make the first move?

Previous reports: USAF Report: “Most” Nuclear Sites in Europe do not Meet US Security Requirements (FAS, June 2008) | United States Removes Nuclear Weapons from German Base, Documents Indicate (FAS, July 2007) | U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe (NRDC, 2005)

USAF Report: “Most” Nuclear Weapon Sites In Europe Do Not Meet US Security Requirements

|

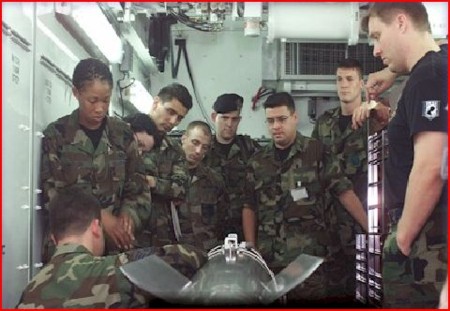

| Members of the 704 Munition Support Squadron at Ghedi Torre in Italy are trained to service a B-61 nuclear bomb inside a Munitions Maintenance Truck. Security at “most” nuclear bases in Europe does not meet DOD safety requirements, a newly declassified U.S. Air Force review has found. Withdrawal from some is rumored. Image: USAF |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen [article updated June 26 following this report]

An internal U.S. Air Force investigation has determined that “most sites” currently used for deploying nuclear weapons in Europe do not meet Department of Defense security requirements.

A summary of the investigation report was released by the Pentagon in February 2008 but omitted the details. Now a partially declassified version of the full report, recently obtained by the Federation of American Scientists, reveals a much bigger nuclear security problem in Europe than previously known.

As a result of these security problems, according to other sources, the U.S. plans to withdraw its nuclear custodial unit from at least one base and consolidate the remaining nuclear mission in Europe at fewer bases.

European Nuclear Safety Deficiencies Detailed

The national nuclear bases in Europe, those where nuclear weapons are stored for use by the host nation’s own aircraft, are at the center of the findings of the Blue Ribbon Review (BRR), the investigation that was triggered by the notorious incident in August 2007 when the U.S. Air Force lost track of six nuclear warheads for 36 hours as they were flow across the United States without the knowledge of the military personnel in charge of safeguarding and operating the nuclear weapons.

|

Figure 1: |

|

|

“Most” nuclear sites in Europe don’t meet DOD security standards, according to the Blue Ribbon Review report. |

The final report of the investigation – Air Force Blue Ribbon Review of Nuclear Weapons Policies and Procedures – found that “host nation security at overseas nuclear-capable units varies from country to country in terms of personnel, facilities, and equipment.” The report describes that “inconsistencies in personnel, facilities, and equipment provided to the security mission by the host nation were evident as the team traveled from site to site….Examples of areas noted in need of repair at several of the sites include support buildings, fencing, lighting, and security systems.”

The situation is significant: “A consistently noted theme throughout the visits,” the BRR concluded, “was that most sites require significant additional resources to meet DOD security requirements.” Despite overall safety standards and close cooperation and teamwork between U.S. Air Force personnel and their host nation counterparts, the inspectors found that “each site presents unique security challenges.”

Specific examples of security issues discovered include conscripts with as little as nine months active duty experience being used protect nuclear weapons against theft.

Inspections can hypothetically detect deficiencies and inconsistencies, but the BRR team found that U.S. Air Force inspectors are hampered in performing “no notice inspections” because the host nations and NATO require advance notice before they can visit the bases. If crews know when the inspection will occur, their performance might not reflect the normal situation at the base.

Many of the safety issues discovered are precipitated by the fact that the primary mission of the squadrons and wings is not nuclear deterrence but real-world conventional operations in support of the war on terrorism and other campaigns. This dual-mission has created a situation where many nuclear positions are “one deep,” and where rotations, deployments, and illnesses can cause shortfalls.

The review recommended consolidating the bases to “minimize variances and reduce vulnerabilities at overseas locations.”

USAFE Commander Visits Nuclear Bases

In light of the findings about Air Force nuclear security, General Roger Brady, the USAFE Commander, on June 11 visited Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium and Volkel Air Base in Holland. Both bases store U.S. nuclear weapons for delivery by their national F-16 fighters.

.

A news story on a USAF web site notes that the weapons security issues found by the BRR investigation were “at other bases,” suggesting that Büchel Air Base in Germany or Ghedi Torre Air Base in Italy were the problem. Even so, the BRR found problems at “most sites,” visits to Kleine Brogel and Volkel were described in the context of these findings. Two commanders of the 52 Fighter Wing at Spangdahlem Air Base, which controls the 701st and 703rd Munitions Support Squadrons at the national bases, were also present “to witness both units for the first time.”

Withdrawal and Consolidation

The deficiencies at host nation bases apparently have triggered a U.S. decision to withdraw the Munition Support Squadron (MUNSS) from one of the national bases.

Four MUNSS are currently deployed a four national bases in Europe: the 701st MUNSS at Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium, the 702nd MUNSS at Büchel Air Base in Germany, the 703rd MUNSS at Volkel Air Base in Holland, and the 704th MUNSS at Ghedi Torre in Italy (see top image).

It is not yet known which base it is, but sources indicate that it might involve the 704th MUNSS at Ghedi Torre in Northern Italy.

Status of Nuclear Weapons Deployment [June 26: warhead estimate updated here]

The number and location of nuclear weapons in Europe are secret. However, based in previous reports, official statements, declassified documents and leaks, a best estimate can be made that the current deployment consists of approximately 150-240 B61 nuclear bombs (see update here). The most recent public official statement was made by NATO Vice Secretary General Guy Roberts in an interview with the Italian RAINEWS in April 2007: “We do say that we’re down to a few hundred nuclear weapons.”

|

Table 1: |

|

|

Derived from more extensive table. Click table or here to download the full table. |

The U.S. weapons are stored in underground vaults, known as WS3 (Weapon Storage and Security System), at bases in Belgium, Germany, Holland, Italy, and Turkey. Most of the weapons are at U.S. Air Force bases, but Belgium, Germany, Holland and Italy each have nuclear weapons at one of their national air bases.

The weapons at each of the national bases are under control of a U.S. Air Force MUNSS in peacetime but would, upon receipt of proper authority from the U.S. National Command Authority, be handed over to the national Air Force at the base in a war for delivery by the host nation’s own aircraft. This highly controversial arrangement contradicts both the Non-Proliferation Treaty and NATO’s international nonproliferation policy.

Implications and Observations

The main implication of the BRR report is that the nuclear weapons deployment in Europe is, and has been for the past decade, a security risk. But why it took an investigation triggered by the embarrassing Minot incident to discover the security problems in Europe is a puzzle.

Since the terrorist attacks in September 2001, billions of dollars have been poured into the Homeland Security chest to increase security at U.S. nuclear weapons sites, and a sudden urge to improve safety and use control of nuclear weapons has become a principle justification in the administration’s proposal to build a whole new generation of Reliable Replacement Warheads.

But, apparently, the nuclear deployment in Europe has been allowed to follow a less stringent requirement.

This contradicts NATO’s frequent public assurances about the safe conditions of the widespread deployment in Europe. Coinciding with the dramatic reduction of nuclear weapons in Europe after the Cold War 15 years ago, “a new, more survivable and secure weapon storage system has been installed,” a NATO fact sheet from January 2008 states. “Today, the remaining gravity bombs associated with DCA [Dual-Capable Aircraft] are stored safely in very few storage sites under highly secure conditions.”

Apparently they are not. Yet despite the BRR findings, the NATO Nuclear Planning Group meeting in Brussels last week did not issue a statement. But at the previous meeting in June 2007 the group reaffirmed the “great value” of continuing the deployment in Europe, “which provide an essential political and military link between the European and North American members of the Alliance.”