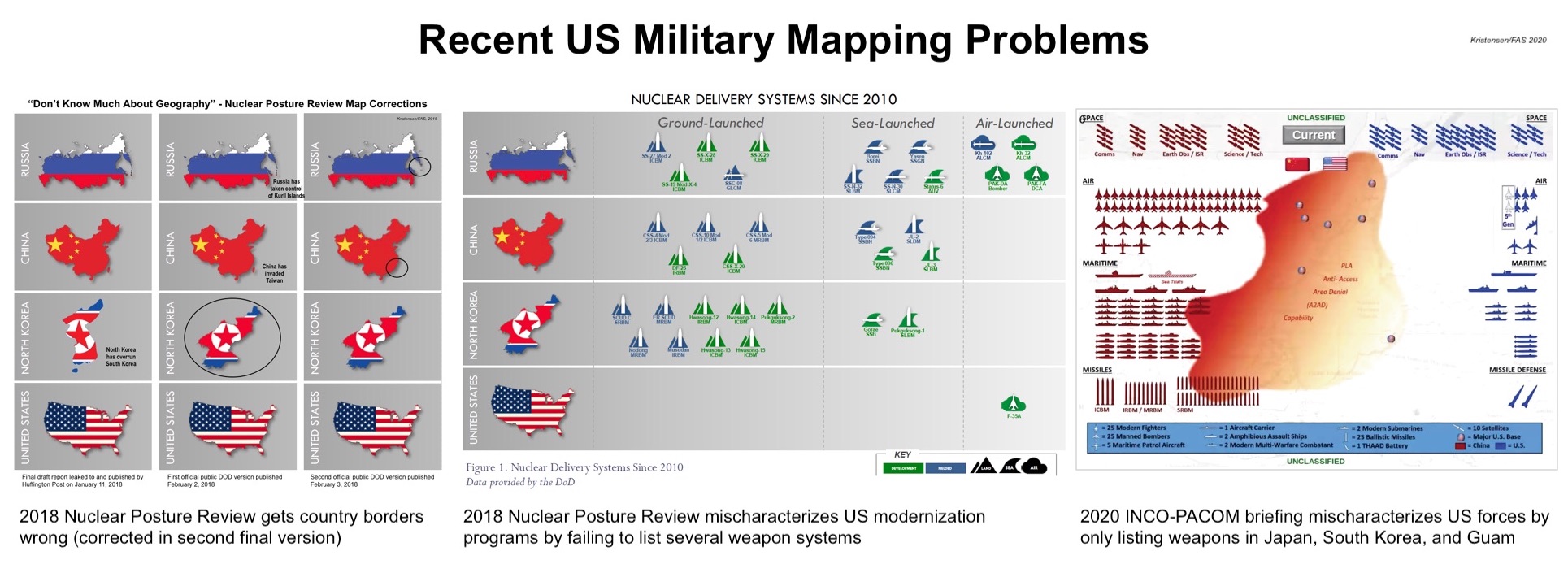

NNSA Removes F/A-18F Super Hornet From Nuclear Bomb Fact Sheet

The F/A-18F is a two-seat version of the F/A-18E. Image: US Department of Defense

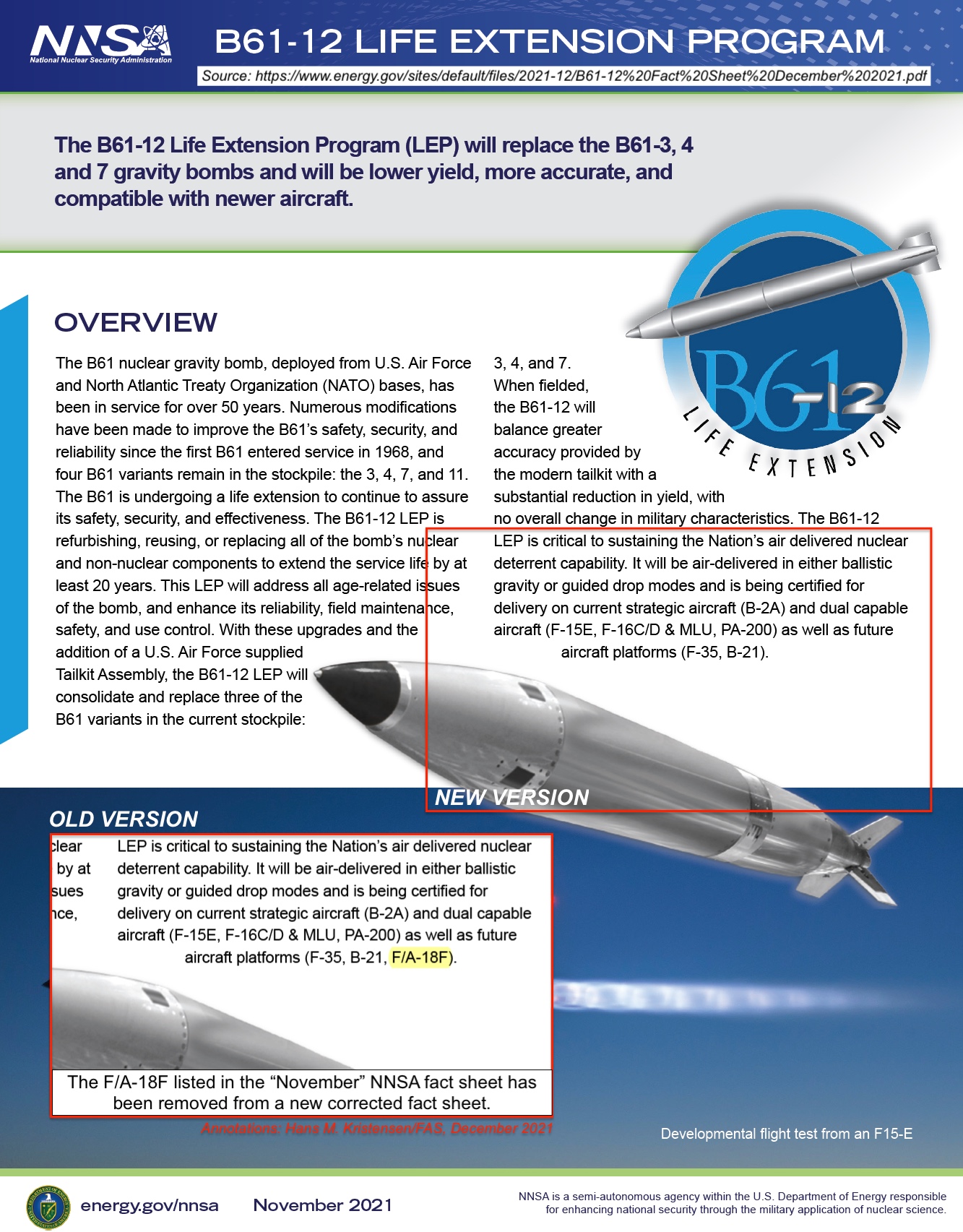

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has quietly removed the F/A-18F Super Hornet from its B61-12 nuclear bomb fact sheet.

No public explanation has been offered for why the aircraft was removed or added in the first place.

The F/A-18F was added to a “November 2021” fact sheet published in early December, which listed the aircraft as one of three future aircraft platforms for the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb (see image below). An earlier version from 2018 did not mention the F/A-18F.

NNSA in 2021 added, and then deleted, the F/A-18F Super Hornet from its B61-12 nuclear bomb fact sheet.

The reason for including the F/A-18F was not stated. It could potentially indicate anticipated sale to Germany to replace its aging Tornado aircraft in the “nuclear sharing” strike mission, or that the U.S. Navy was planning to reintroduce nuclear capability on aircraft carriers (unlikely).

In response to questions from me, NNSA initially said neither of those were the reason for including the F/A-18F in the fact sheet. But after coordinating with the Defense Department, NNSA asked me to ignore that explanation saying the listing of the F/A-18 in the fact sheet was a mistake.

I have also asked the Defense Department, but it has not responded yet. Update: DOD said “there is not a requirement for the F/A-18F to be certified to carry the B61-12.”

What’s Going On?

The 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) considered many new nuclear weapons, but only two made it into the public version of the document as “nuclear supplements”: the low-yield W76-2 Trident warhead and the nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N). The W76-2 is already deployed, and the Biden administration’s NPR is currently considering whether to continue the SLCM-N. Doing so would violate the 1992 Presidential Nuclear Initiative.

One of the ideas proposed was reintroducing nuclear weapons on the aircraft carriers, an idea pushed by some former officials. The military rejected the idea. The carriers were denuclearized by the 1994 Nuclear Posture Review, the Navy does not want nukes back on them, but it would in any case probably have been the F-35C – not the F/A-18F.

F/A-18 aircraft (background) used to be tasked with delivering nuclear bombs from aircraft carriers. The image shows B61 (left) and B43 nuclear bomb trainers on the deck of USS America (CV-66) during the 1991 Gulf War. Image: US Navy.

Instead, the appearance of the F/A-18F in the NNSA fact sheet probably reflected preparations to support Germany’s anticipated purchase the aircraft for its nuclear mission, and that the fact sheet was likely corrected because the German government has not publicly announced its selection of the F/A-18 (and the Parliament has not yet agreed to pay for it).

There is a lot of opposition in Germany to nuclear weapons and the question of whether to continue participation in the nuclear-sharing mission is politically sensitive. In 2020, Der Spiegel reported that the German defense minister had informed the Pentagon that Germany intended to buy the F/A-18 to replace the current Tornados (PA-200) in the “nuclear-sharing” strike mission. The report caused an uproar because the Parliament had not been informed or agreed. The minister later denied that a decision had been made, at least officially.

Pressure has been building on Germany to continue the nuclear-sharing mission. During the negotiations of the new coalition government, NATO secretary general Johan Stoltenberg issued what appeared to be an empty threat that “the alternative is that we easily end up with nuclear weapons in other countries in Europe, also to the east of Germany.”

The threat appeared empty because NATO had just endorsed a new defense plan to protect against “the growing threat from Russia’s missile systems” that included “improving the readiness” of NATO nuclear forces. Why NATO would choose to deploy its nuclear forces further east closer to those missiles is unclear. Moreover, deployment of nuclear weapons further east would require NATO consensus, which seems unlikely. But the threat was heard in Moscow and Stoltenberg later had to walk back his threat by reassuring that “We have no plans of stationing any nuclear weapons in other countries than [those that] already have these nuclear weapons….”

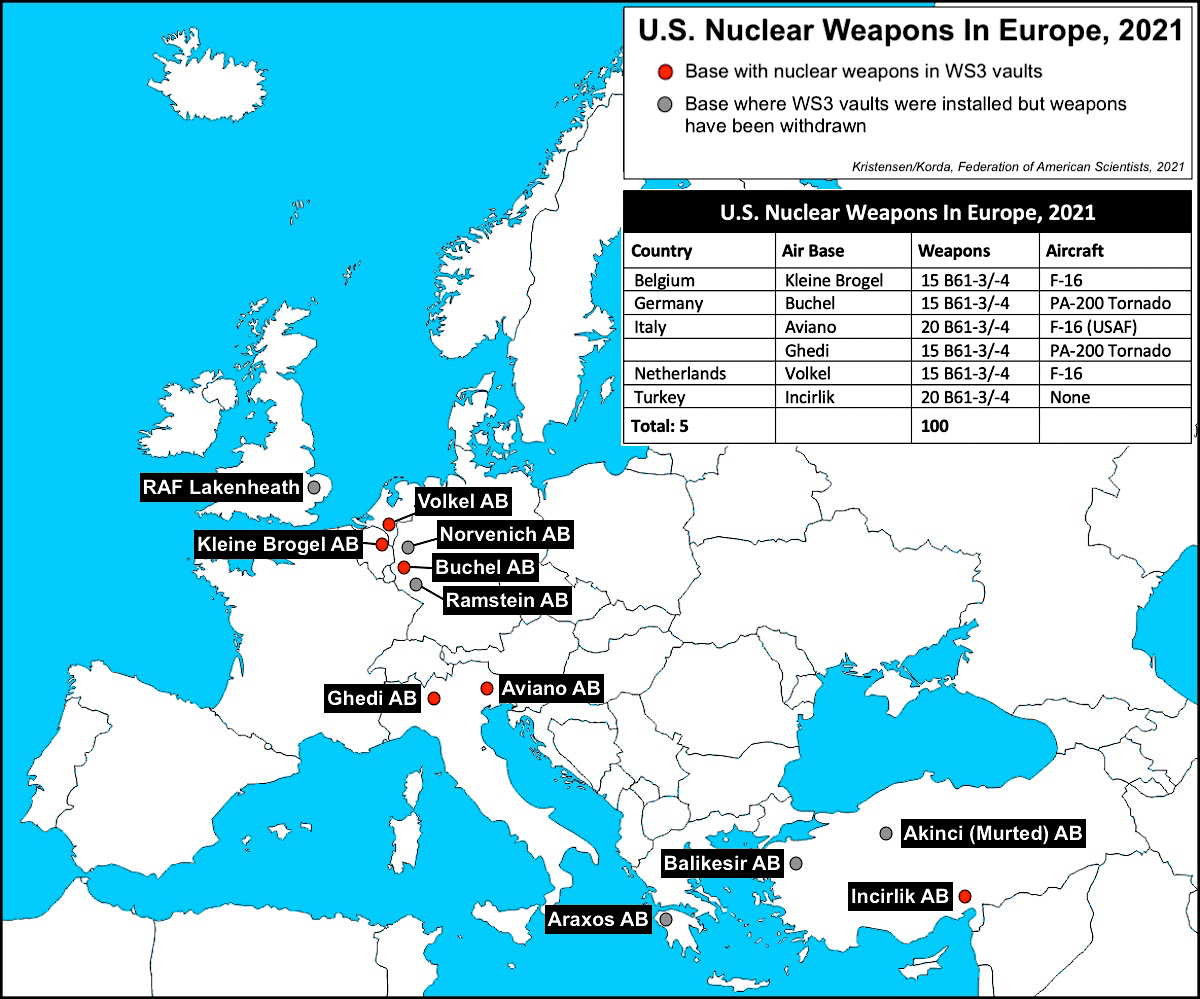

The tactical nuclear weapons mission in Europe was recently exercised in the Steadfast Noon exercise held in northern Italy in October. The exercise included German Tornado fighter-bombers. There are an estimated 100 US non-strategic B61 nuclear bombs deployed in Europe, including about 15 at Buchel Air Base in Germany (see map below).

The US Air Force deploys an estimated 100 B61 nuclear bombs at five bases in six European NATO countries. There are no nuclear weapon storage facilities in the new Eastern European NATO countries.

The pressure apparently worked: The new German coalition government took office with a program that agreed to continue Germany’s participation in the nuclear-sharing mission. Although the US Navy has decided to end production of the F/A-18E/F after this year to focus resources on the F-35C, Boeing could continue production for foreign customers, including Germany. And Boeing officials reportedly expect Germany to issue a letter of request for the F/A-18F Super Hornet and EA-18G Growler in early 2022.

The F/A-18F has been removed from the fact sheet for now, but if Germany submits a formal request to buy the aircraft, NNSA will have to update the fact sheet once again.

Additional information:

- NNSA B61-12 Fact Sheet

- Video Shows Earth-Penetrating Capability of B61-12 Nuclear Bomb

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: United States nuclear weapons, 2021

- FAS overview: Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

After Trump Secrecy, Biden Administration Restores US Nuclear Weapons Transparency

[Updated] The Biden administration yesterday afternoon declassified the number of nuclear weapons the United States possesses. The act reverses the secrecy of the Trump administration, which denied release of the number for three years, and restores the nuclear transparency of the Obama administration.

FAS’ Steve Aftergood asked for this information in March 2021. We have still not received an official response.

Although a victory for nuclear transparency, the data shows only very limited nuclear weapons reductions in recent years – a stark reminder of the international nuclear climate, domestic policies, and that a lot more work is needed to reduce nuclear dangers.

Stockpile Numbers

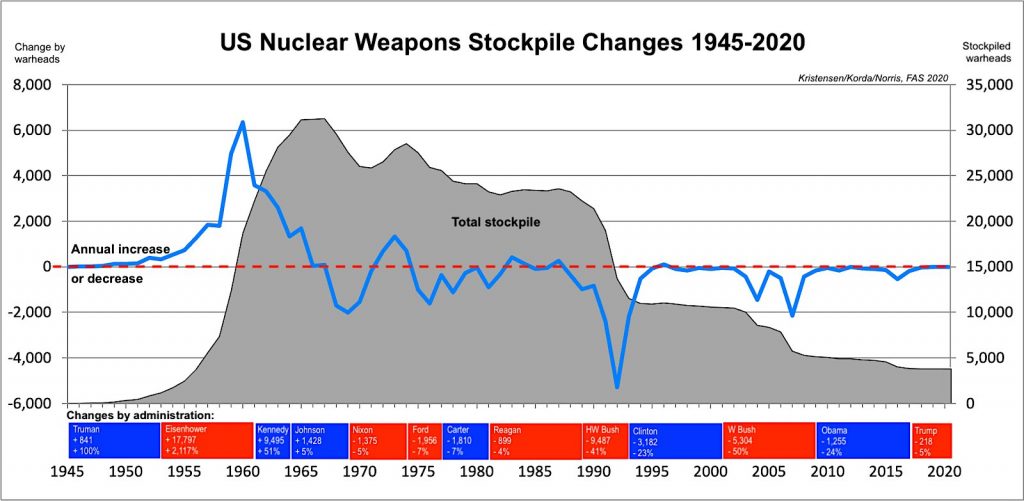

According to the new data, the United States possessed a total of 3,750 nuclear warheads in the Department of Defense nuclear weapons stockpile as of September 2020. That number is only 50 warheads less than our estimate of 3,800 warheads from early this year.

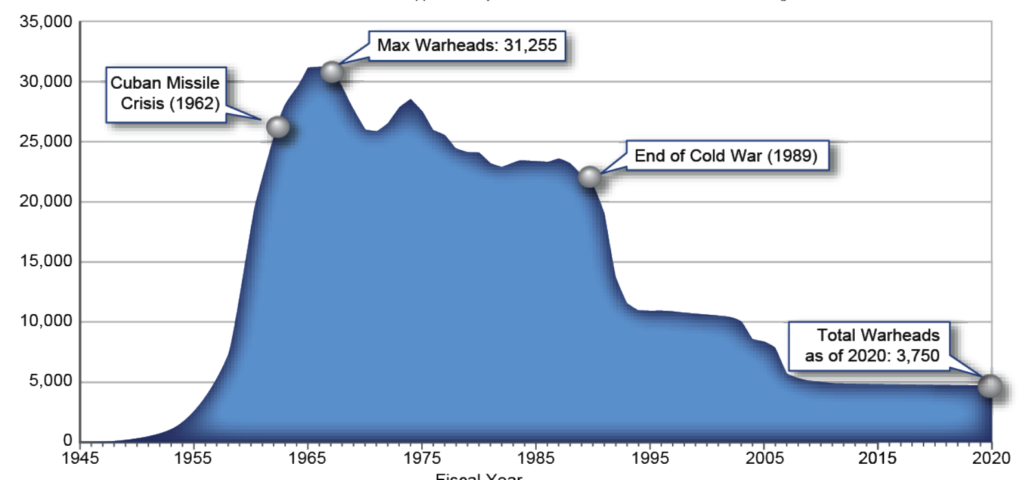

The 3,750-warhead number is only 72 warheads fewer than in September 2017, the last number made available before the Trump administration closed the books.

That reduction is by any measure mediocre. In its announcement about the new stockpile numbers, the US Department of State highlights that the current stockpile of 3,750 warheads “represents an approximate 88 percent reduction in the stockpile from its maximum (31,255) at the end of fiscal year 1967, and an approximate 83 percent reduction from its level (22,217) when the Berlin Wall fell in late 1989.” While that is true and an amazing accomplishment, the fact remains that the vast majority of that reduction happened in two phases during the H.W. Bush and W. Bush administrations. Since 2008 the reduction has been slow and limited. The trend is that the reduction is decreasing and leveling out.

A peculiar revelation in the new data is that it shows that the stockpile increased by 20 warheads between September 2018 and September 2019 when Trump was in office. The increase is not explained but one possibility is that it reflects the production of the new W76-2 low-yield warhead that the Trump administration rushed into production in response to what it said was Russia’s plans for first-use of tactical nuclear weapons. The first W76-2 was produced in February 2019, NNSA was scheduled to deliver all the warheads by end of Fiscal Year 2019, but the W76-2 wasn’t completed until June 2020. Arkin and Kristensen reported in January 2020 that the first W76-2s had been deployed, which was later confirmed by the Pentagon.

It is possible (but unconfirmed) that the 20-warhead stockpile increase between 2018 and 2019 was caused by production of the Trump administration’s W76-2 low-yield Trident warhead. Image: NNSA.

The Trump administration’s brief increase of the stockpile is only the second time the United States has increased its number of nuclear warheads since the Cold War. The first time was in 1995-1996 when the Clinton administration increased the stockpile by 107 warheads. Since the W76-2 production continued after September 2019, the increase of 20 warheads should not be misinterpreted as being the final number of W76-2 warheads. After the 2018-2019 increase, the stockpile number dropped again by 55 warheads.

Update: Another possibility for the brief stockpile increase is that a small number of retired warheads were returned to the stockpile. This could potentially be B83-1 bombs that the Trump administration decided to retain instead of retiring with the fielding of the B61-12. It could potentially also be retired warheads brought in as feedstock for new weapon systems such as the planned nuclear sea-launched cruise missile. We just don’t know at this point.

Apparently, the nuclear modernization program supported by both Republicans and most Democrats, will result in significant additional reductions of the stockpile. In 2016, the former head of the Navy’s Strategic Systems Program, Vice Admiral Terry Benedict, said that once the W76-1 warhead production was completed by the end of FY2019, the W76-0 warheads that had not been converted to W76-1 would be retired and the total number of W76 warheads in the stockpile decrease by nearly 50%.

At the same time, the Pentagon’s Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs, Arthur T. Hopkins, told Congress that production and fielding of the B61-12 bomb would “result in a nearly 50 percent reduction in the number of nuclear gravity bombs in the stockpile” and “facilitate the removal from the stockpile of the last megaton-class weapon––the B83-1.”

Production of the W76-1 has now been completed but the promised reduction is not yet visible in the stockpile data – unless the excess warheads were gradually removed during the production years. The B61-12 has not been fielded yet so the gravity bomb reduction presumably will not happen until the mid-2020s.

Whatever the number of the additional stockpile reduction is, it is not planned to be nice to Kremlin and Beijing but because the US military doesn’t need the excess warheads anymore. Whether Russia and China’s nuclear increases will cause the Biden administration to change the plan outlined by Benedict and Hopkins will be decided by the Nuclear Posture Review.

Dismantlement Numbers

The data also shows that the United States as of September 2020 had about 2,000 retired warheads in storage awaiting dismantlement. Retired warheads are owned by the Department of Energy and not part of the DOD stockpile.

That number matches the available data. Former Secretary of State John Kerry said in 2015 that there were about 2,500 retired weapons left (as of September 2014). Since then, 1,432 warheads have been dismantled and an additional 967 weapons retired, which would leave just over 2,000 warheads in the dismantlement queue.

Approximately 2,000 retired warheads away dismantlement, including the B83 megaton gravity bomb. More are expected to follow during the next decade. Image: NNSA.

In our estimate from early this year, we thought the dismantlement queue had dropped to 1,750 warheads because we assumed the annual dismantlement rate had remained around 300. But as the data shows, both the Trump and Biden administrations reduced the number of warheads being dismantled per year.

In 2016, NNSA stated that it “will increase weapons dismantlement by 20 percent starting in FY 2018” and that the “accelerated rate will allow NNSA to complete the dismantlement commitment a year early, before the end of FY 2021.” NNSA reaffirmed in 2018, that all warheads retired prior to 2009 would be dismantled by end-FY 2022.

This pledge appears to have faded from recent documents after the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review was published. Instead, the annual number of warheads dismantled has decreased since FY 2018. Is it still the goal? Some of the warheads that should have been dismantled but are still with us reportedly include the W84 warheads from the ground-launched cruise missiles that were eliminated by the 1987 INF treaty and retired well before 2009.

Many of the warheads in the current dismantlement queue were retired after 2009. At the current rate of 184 warheads dismantled per year, it will take more than a decade to dismantle the current backlog. Once the excess W76s and old gravity bombs enter the queue, it will take even longer.

In Context

We commend the Biden administration for reversing the Trump administration’s shortsighted and counterproductive nuclear secrecy and restore transparency to the US nuclear weapons stockpile. This decision is a heavy lifting at a time when so-called Great Power Competition is overtaking defense and arms control analysis. The Federation of American Scientists has for years advocated for increased transparency of nuclear arsenals and have worked to provide that through our estimates of nuclear weapons arsenals.

Although the recent reductions shown in stockpile and dismantlement data are modest, to put it mildly, we believe declassification is the right decision because making the record public will help US diplomats make the case that the United States is continuing its efforts to reduce nuclear arsenals and increase nuclear transparency. This is especially important in the context of the upcoming January 2022 Review Conference for the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. Dissatisfaction with the lackluster disarmament progress – and a belief that the nuclear-armed states are walking back decades of arms control progress with their excessive nuclear modernization programs and dangerous changes to operations and strategy – have fueled support for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

The decision to disclose the stockpile and dismantlement data will also enhance the US credibility when urging other nuclear-armed states to be more transparent about their arsenals. We have no illusions that Russia or China will follow the example in the short term, but keeping the US numbers secret will certainly not help. And over time, the disclosure can help shape discussions and norms about nuclear transparency to shape future decisions. This is also important because the Trump secrecy recently provided cover for the United Kingdom to reduce information about its nuclear forces.

Hardliners will no doubt criticize the Biden administration’s decision to disclose the stockpile and dismantlement data. They will argue that past nuclear transparency has not given the United States any leverage, that nuclear-armed states previously have not followed the example, and it that makes the United States look naive – even irresponsible – in view of Russia and China’s nuclear secrecy and build-up.

On the contrary: without transparency the United States has no case. Past transparency has given the United States leverage to defend its record and promote its policies in international fora, dismiss rumors and exaggerations about its nuclear arsenal, and publicly and privately challenge other nuclear-armed states’ secrecy and promote nuclear transparency. And since the disclosure does not reveal any critical national security information, there is no reason to classify the stockpile and dismantlement data.

Hardliners obviously will have to acknowledge that the data shows that there has been no unilateral US disarmament but only a very modest reduction in recent years. And although there appear to be additional unilateral reductions built into the modernization programs, those are actually programs that have been supported and defended by the hardliners.

Now it is up to the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review to articulate how and to what extent those plans support and strengthen US national security and nonproliferation objectives. Arms control obviously will have to be part of that assessment. The declassified stockpile and dismantlement data will help make the case that additional reductions are both needed and possible.

Background Information:

- US Department of State, Transparency in the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Stockpile, Fact Sheet, October 5, 2021

- “United States Nuclear Forces, 2021,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March/April 2021

- “Pentagon Slams Door On Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Transparency,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, April 17, 2019

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American Scientists global arsenal page

This article was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

What Is the Sole Purpose of U.S. Nuclear Weapons?

Summary

- Prior to assuming office, President Biden indicated that he would establish that “the sole purpose of our nuclear arsenal is to deter—and, if necessary, retaliate for—a nuclear attack against the United States and its allies.”

- Sole purpose should be understood as a central component of an integrated deterrence strategy that can effectively manage the risk of nuclear escalation in a limited conflict as well as the rising stability risks from nonnuclear weapons.

- Sole purpose could significantly reduce the risk of unintended escalation and increase the credibility of more flexible and realistic nonnuclear response options in a range of importance contingencies.

- In order to attain its intended benefits, declaratory policy must be reflected in force structure and planning.

- The president’s existing language on sole purpose provides considerable flexibility for the administration to define the doctrine, but does not itself provide clear guidance for strategy, force structure, or for related declaratory policies like “no first use.”

- Defining sole purpose is a critical task for the administration’s defense policy review.

- As a central component of an integrated defense policy that will strengthen US deterrence and assurance credibility, sole purpose should be defined at the level of the NDS.

- A sole type definition would state that the United States would consider nuclear use in response to a certain type of attack, having modest effects on a narrow set of plans but few effects on force structure.

- A sole function definition would define what is and what is not a requirement of deterrence, potentially removing certain strategic or nonstrategic roles of nuclear weapons.

Depending on how it is defined, sole purpose could have transformational effects on nearly every aspect of nuclear weapons policy or relatively modest effects. It could accommodate or incorporate a range of related policy options, like a deterrence-only posture or no first use.

- Fully implementing a sole purpose policy is critical to attaining its benefits.

- A simple declaratory statement is not a complete sole purpose policy. Because any statement is likely to be ambiguous, sole purpose should also consist of a set of presidential directives that determine how the policy will be affect force structure and planning.

- By eliminating one or more of the requirements that structure US nuclear forces, a sole function definition could potentially have significant effects on a range acquisition decisions and plans.

- If the president concludes that sole purpose has implications for force structure or force posture, the administration should ensure that these changes are made before the presidential term is concluded.

- Following a decision to adopt sole purpose, civilian officials should review existing operational plans and concepts to ensure that they comport with the president’s guidance for escalation management of a conflict with a nuclear-armed adversary.

- Embedding the policy in plans, force structure, and allied consultations is critical to achieving its benefits and reducing the risk that it is reversed by a future president, which would be highly risky.

- If defined, implemented, and communicated as a part of an effective integrated deterrence posture, sole purpose could strengthen assurance of allies.

- Some allies will be understandably apprehensive about any shift in US nuclear weapons policy in the current environment.

- Allies should be consulted closely as sole purpose is being defined, as it is released, and as it is being implemented.

In January 2021, President Biden assumed office after having made unusually explicit commitments to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in US national security strategy. In his primary articulation of his campaign’s foreign policy, BJoseph R. Biden, “Why American Must Lead Again: Rescuing US Foreign Policy after Trump,” Foreign Affairs 99 (2020): 64.iden declared that “the sole purpose of the US nuclear arsenal should be deterring—and if necessary, retaliating against—a nuclear attack.”1 Since assuming office, Biden has not repeated the pledge, though his initial national security guidance and his Secretary of State have reiterated the goal of reducing reliance on nuclear weapons.2 As the Pentagon begins its review of nuclear weapons policy, Biden and his national security officials will have to determine whether to adopt sole purpose and, if so, what it means. The established language on sole purpose offers the administration considerable latitude in how it chooses to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons. Depending on how sole purpose is defined and implemented, it could have transformative consequences for nuclear force structure and strategy, or it could end up as a rhetorical commitment that has few practical effects at all.

Though the language dates back decades, there has never been a precise or agreed definition of sole purpose. The first published use of the phrase is in a piece Albert Einstein related to the eminent journalist Raymond Swing that was published in the Atlantic in 1947. Einstein argued while the United States must stockpile the bomb, it should forswear its use. “Deterrence should be the only purpose of the stockpile of bombs.” If the United Nations were granted international control over atomic energy, as President Truman had proposed, it should be “for the sole purpose of deterring an aggressor or rebellious nations from making an atomic attack.3 Since the idea was popularized in the 1960s, sole purpose has become a persistent staple in ongoing debates about the role of nuclear weapons, but it has rarely been attached to a precise definition or a plan to implement it.

Sole purpose is more ambiguous than other declaratory policy proposals (such as no first use) because it purports to define, or constrain, the purpose of nuclear weapons. Depending on how the terms of the statement are defined and how the statement is implemented in practice, its effects could be broad, narrow, restrictive, permissive, or ambiguous. For example, President Biden’s sole purpose language could be construed to proscribe nuclear weapons from performing a wide range of functions or from being used in wide ranges of contingencies. Slight variations in the wording of a sole purpose declaration can produce dramatically different policies and be perceived differently by allies and adversaries, who will examine the policy closely. Depending on how sole purpose is defined and implemented, sole could reduce or eliminate requirements for each piece of the triad or for nuclear use in a variety of different contingency plans.

Sole purpose is one potential option in declaratory policy, that aspect of nuclear weapons policy that publicly communicates when and why the United States would consider the use of nuclear weapons. It can be combined with or can subsume a range of other potential declaratory policy options. Because the president has sole authority to order the use of a nuclear weapon, only the president can set limits on that power. Though changes in declaratory policy should consider the views of civilian national security officials, uniformed military officials, members of Congress, US allies, and the American public, the president should provide clear guidance on how to modify US declaratory policy. Like all presidents, President Biden should provide clear guidance to the officials conducting the national defense strategy about nuclear declaratory policy.

Because sole purpose could potentially be defined in many different ways, some definitions will be better or worse. Advocates or opponents should be clear about what constitutes a better or worse definition. The administration should not accept the argument that a good definition is one that preserves existing force structure or plans, maintains ambiguity for its own sake, or comports with the preferences of certain allies or services. This piece argues that a good definition of sole purpose is one that assists with the development and implementation of a credible, integrated posture by which the United States and its allies deter aggression and nuclear use; reflects the president’s preferences about how to manage escalation in limited conflicts with nuclear-armed adversaries as well as his assessment of the requirements of deterring a major strategic attack; reduces the risk of misperception and adversary nuclear first use incentives; and can be implemented in force structure and plans so that it is resilient to leadership changes in the United States. Because the president has expressed a preference to reduce the nation’s reliance on nuclear weapons, a good definition of sole purpose should help to do so in ways consistent with his preferences.

This piece examines the range of options available to officials working to define sole purpose and reduce reliance on nuclear weapons. It explores the practical implications of different definitions of sole purpose and the steps necessary to ensure that they are implemented in a way that is responsible, effective, and most likely to endure over time. There are two central arguments. First, sole purpose should not be understood as a nuclear declaratory policy but as critical component in an integrated deterrence strategy. Understood in this way, sole purpose is not only a valuable means of reducing the risk of nuclear escalation and of meeting US commitments to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons but because it is a substantive judgment about how US nuclear and nonnuclear forces can best manage escalation in a limited conflict with a nuclear-armed adversary. Second, an effective sole purpose policy cannot simply be a sentence in a paragraph on nuclear declaratory policy. If the administration is serious about attaining the benefits of sole purpose, the policy should be comprised of the declaratory statement, additional language to clarify and contextualize the policy, and a set of directives that communicate the president’s guidance for how the policy should affect force structure and plans.

Each of these arguments is critical for attaining the benefits of sole purpose and for maintaining an effective deterrence posture. Sole purpose will be a contentious idea under any circumstances. Allied governments, advocates of various aspects of the current nuclear weapons policies, and political opponents are understandably concerned about the president’s statements. Clearly defining the policy, articulating how it will strengthen an integrated deterrence policy, and moving forward with implementation will help to convince allies and many deterrence experts that sole purpose will increase rather than decrease deterrence credibility.

First New START Data After Extension Shows Compliance

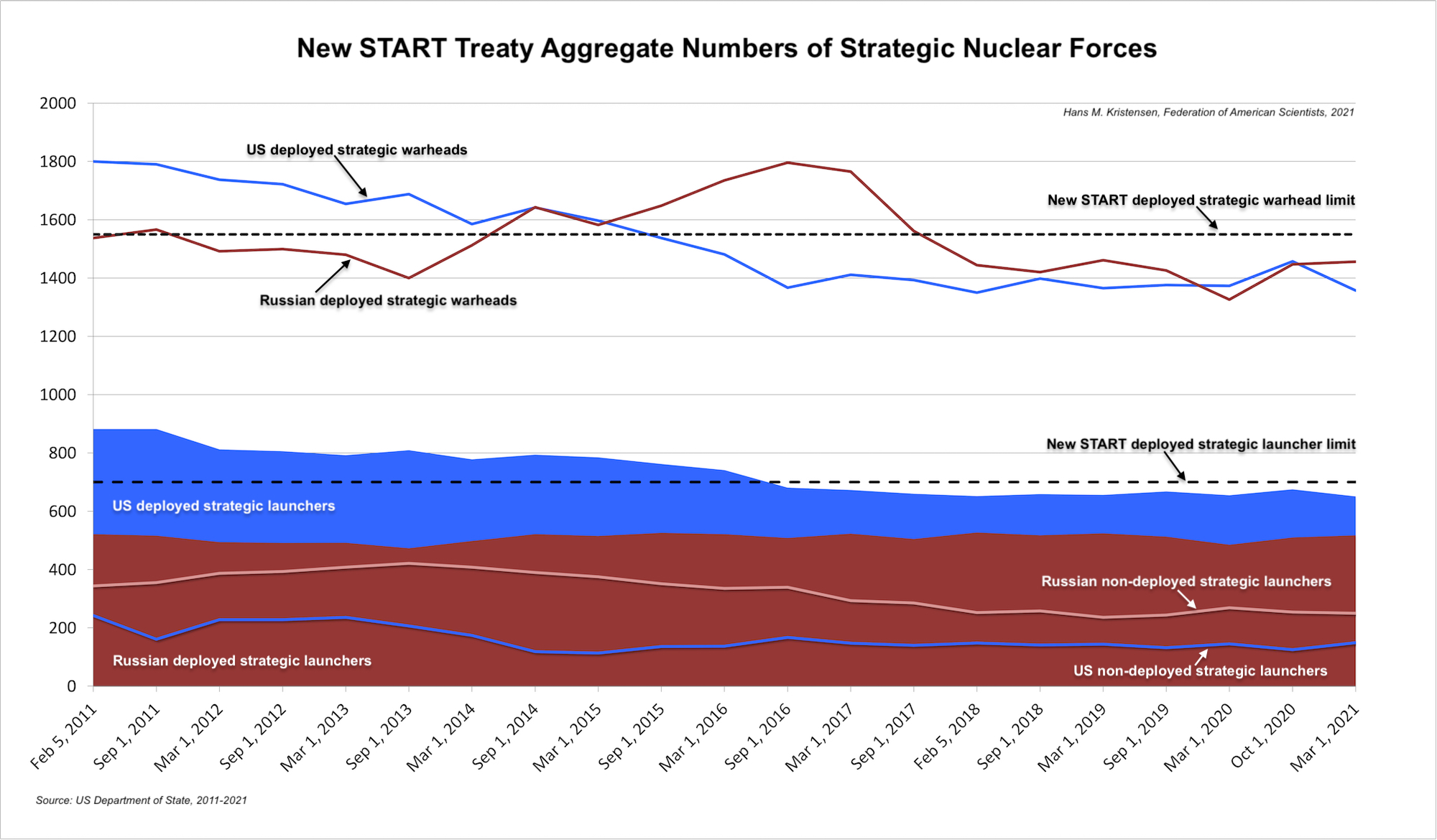

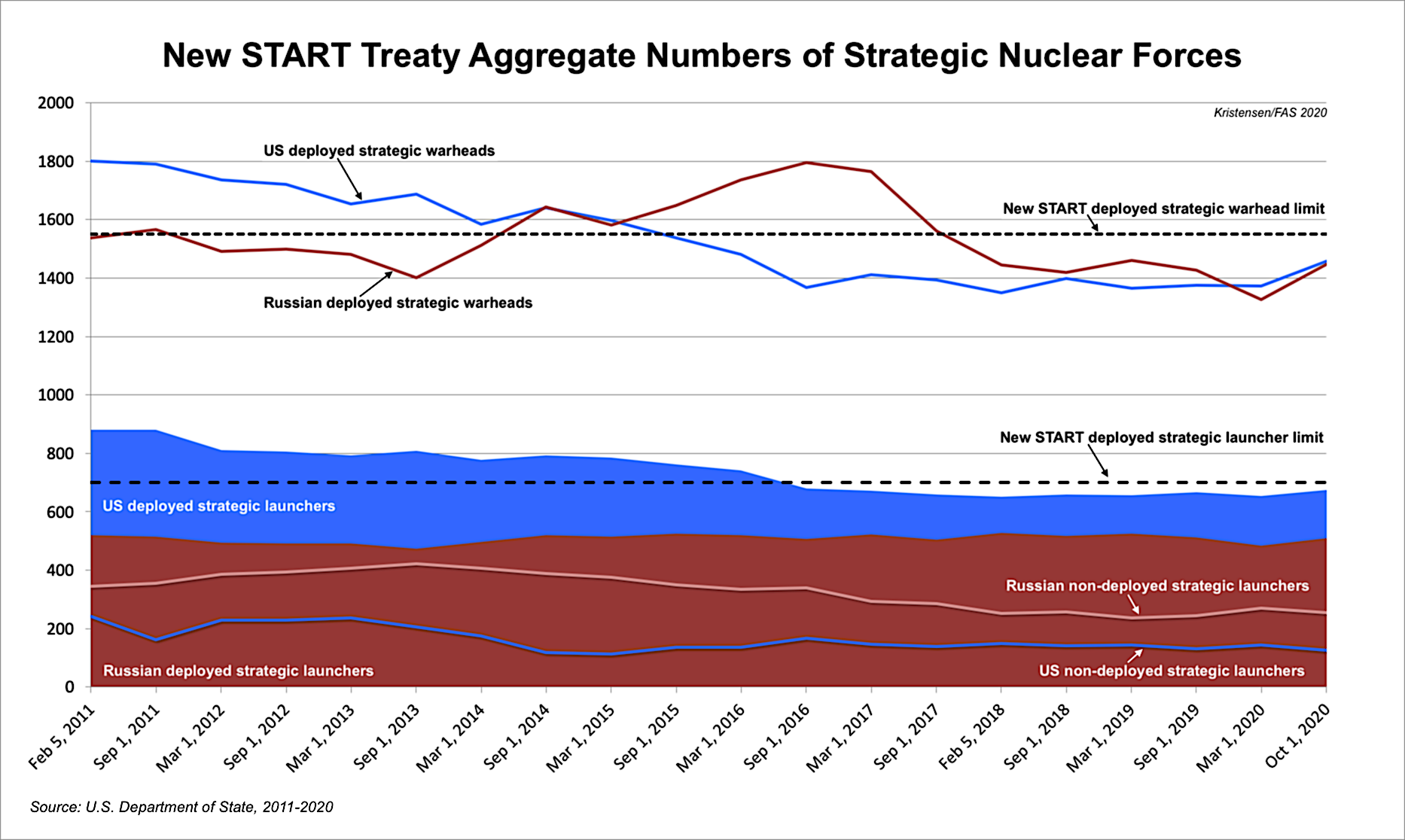

The first public release of New START aggregate numbers since the United States and Russia in February extended the agreement for five years shows the treaty continues to limit the two nuclear powers strategic offensive nuclear forces.

Continued adherence to the New START limits is one of the few positive signs in the otherwise frosty relations between the two countries.

The ten years of aggregate data published so far looks like this:

Combined Forces

The latest set of this data shows the situation as of March 1, 2021. As of that date, the two countries possessed a combined total of 1,567 accountable strategic missiles and heavy bombers, of which 1,168 launchers were deployed with 2,813 warheads. That is a slight decrease in the number of deployed launchers and warheads compared with six months ago (note: the combined warhead number is actually about 100 too high because each deployed bomber is counted as one weapon even though neither country’s bombers carry weapons under normal circumstances).

Compared with September 2020, the data shows the two countries combined increased the total number of strategic launchers by 3, decreased combined deployed strategic launchers by 17, and decreased the combined deployed strategic warheads by 91. Of these numbers, only the “3” is real; the other changes reflect natural fluctuations as launchers move in and out of maintenance or are being upgraded.

In terms of the total effect of the treaty, the data shows the two countries since February 2011 combined have cut 422 strategic launchers from their arsenals, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 235, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 524. However, it is important to remind that this warhead reduction is but a fraction (just over 6 percent) of the estimated 8,297 warheads that remain in the two countries combined nuclear weapons stockpiles (just over 4 percent if counting their total combined inventories of 11,807 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The United States

The data shows the United States currently possessing 800 strategic launchers, exactly the maxim number allowed by the treaty, of which 651 are deployed with 1,357 warheads attributed to them. This is a decrease of 24 deployed strategic launchers and 100 deployed strategic warheads over the past 6 months. These are not actual decreases but reflect normal fluctuations caused by launchers moving in and out of maintenance. The United States has not reduced its total inventory of strategic launchers since 2017.

The aggregate data does not reveal how many warheads are attributed to the three legs of the triad. The full unclassified data set will be released later. But if one assumes the number of deployed bombers and deployed ICBMs are the same as in the September 2020 data, then the SSBNs carry 909 warheads on 200 deployed Trident II SLBMs. That is a decrease of 100 warheads on the SSBN force compared with September, or an average of 4-5 warheads per deployed missile. Overall, this accounts for 67 percent of all the 1,357 warheads attributed to the deployed strategic launchers (nearly 70 percent if excluding the “fake” 50 bomber weapons included in the official count).

The New START data indicates that the United States as of March 1, 2021 deployed approximately 909 warheads on ballistic missile onboard its strategic submarines.

Compared with February 2011, the United States has reduced its inventory of strategic launchers by 324, deployed launchers by 231, and deployed strategic warheads by 443. While important, the warhead reduction represents only a small fraction (about 12 percent) of the 3,800 warheads that remain in the U.S. stockpile (less than 8 percent if counting total inventory of 5,800 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian Federation

The New START data shows Russia with an inventory of 767 strategic launchers, of which 517 are deployed with 1,456 warheads attributed to them. Compared with six months ago, this is an increase of 7 deployed launchers and 9 deployed strategic warheads. The change reflects fluctuations caused by launcher maintenance and upgrade work to new systems.

Compared with February 2011, Russia has cut its inventory of strategic launchers by 98, deployed launchers by 4, and deployed strategic warheads by 81. This modest warhead reduction represents less than 2 percent of the estimated 4,497 warheads that remain in Russia’s nuclear weapons stockpile (only 1.3 percent if counting the total inventory of 6,257 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) Russian warheads).

Compared with 2011, the Russian reductions accomplished under New START are smaller than the U.S. reductions because Russia had fewer strategic forces than the United States when the treaty entered into force in 2011.

Build-up, What Build-up?

With frequent claims by U.S. officials that Russia is increasing its nuclear arsenal, which may be happening in some categories, it is interesting that despite a significant modernization program, the New START data shows this increase is not happening in the size of Russia’s accountable strategic nuclear forces. (The number of strategic-range nuclear forces outside New START is minuscule.)

On the contrary, the New START data shows that Russia has 134 deployed strategic launchers less than the United States, a significant gap roughly equal to the number of missiles in an entire US Air Force ICBM wing. It is significant that Russia despite its modernization programs so far has not sought to reduce this gap by deploying more strategic launchers. Instead, the Russian launcher deficit has been increasing by nearly one-third since its lowest point in February 2018.

Although Russia is modernizing its nuclear forces, such as those of this SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24, Yars) ICBM exercise near Bernaul, this has not yet resulted in an increase of its strategic nuclear weapons.

Instead, the Russian military appears to try to compensate for the launcher disparity by increasing the number of warheads that can be carried on the newer missiles (SS-27 Mod 2, Yars, and SS-N-32, Bulava) that are replacing older types (SS-25, Topol, and SS-N-18, Vysota). Thanks to the New START treaty limit, many of these warheads are not deployed on the missiles under normal circumstance but are stored and could potentially be uploaded onto the launchers in a crisis. The United States also has such an upload capability for its larger inventory of launchers and therefore is not at a strategic disadvantage.

Two of Russia’s new strategic nuclear weapons (SS-19 Mod 4, Avangard, and SS-29, Sarmat) are covered by New START if formally incorporated. Other types (Poseidon nuclear-powered torpedo, and Burevestnik nuclear-powered ground-launched cruise missile) are not yet deployed and appear to be planned in relatively small numbers. They do not appear capable of upsetting the strategic balance in the foreseeable future. The treaty includes provisions for including new weapon types, if the two sides agree.

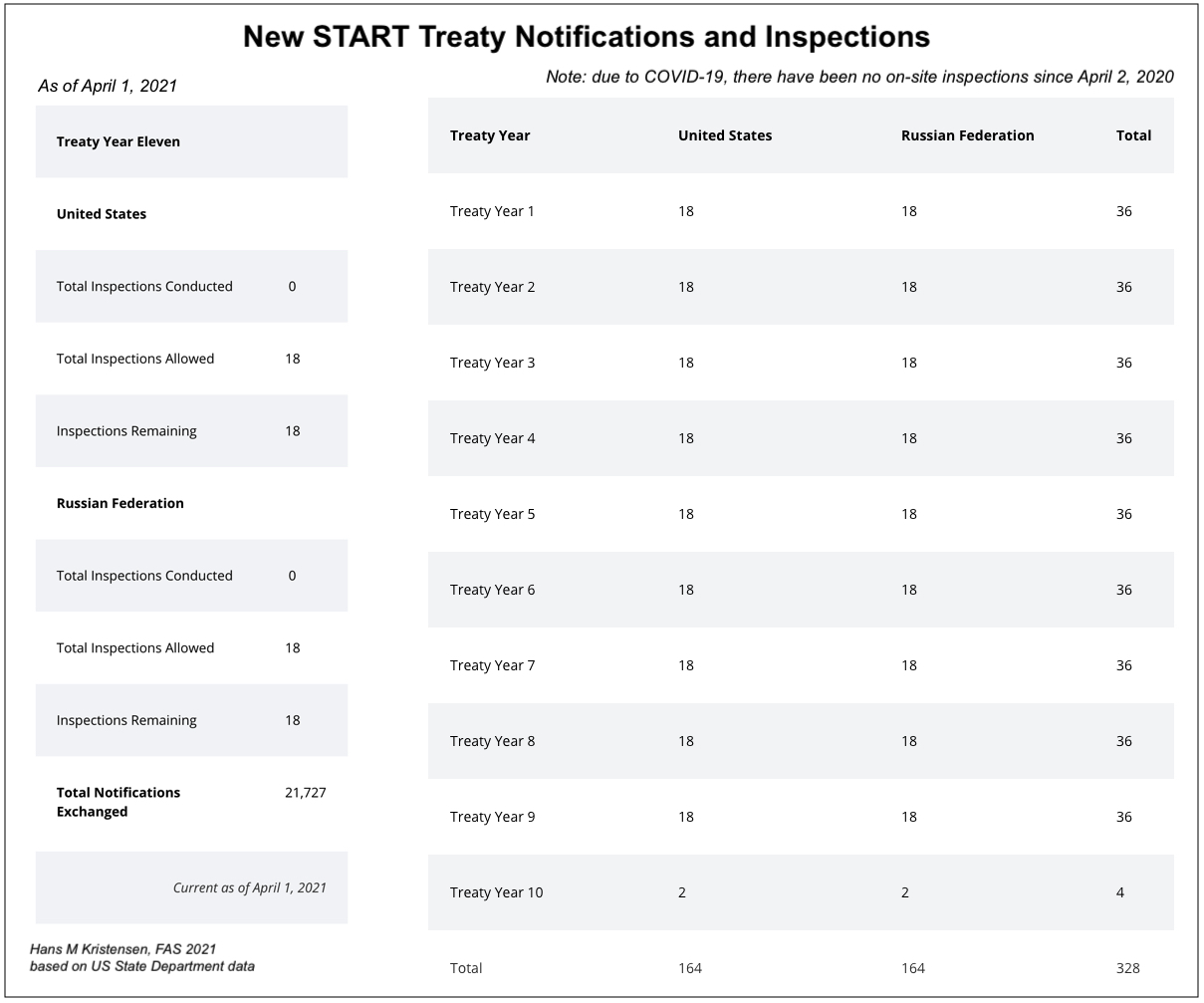

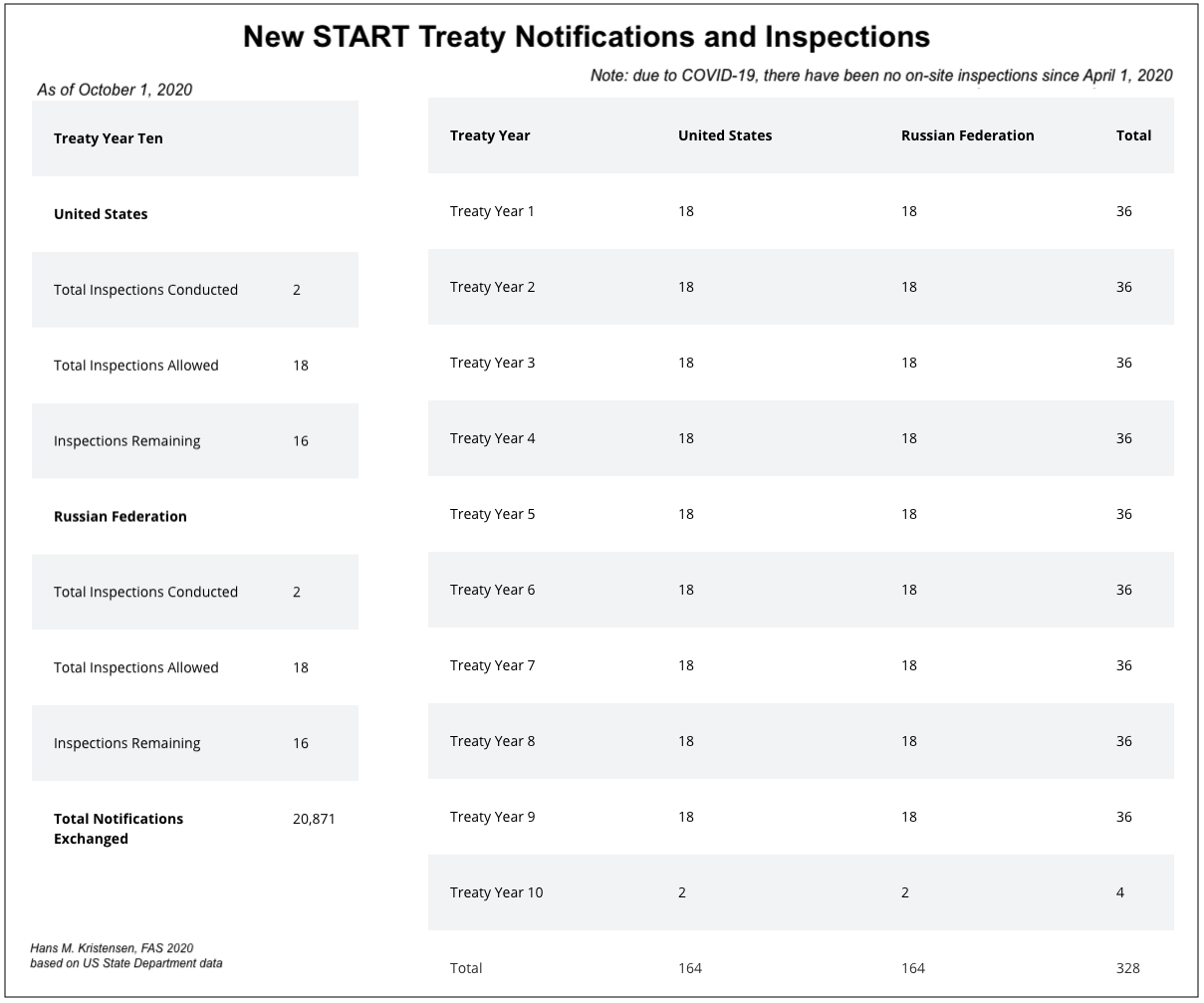

Inspections and Notifications

In addition to the New START data, the U.S. State Department has also updated the overview of part of its treaty verification activities. The data shows that the two sides since February 2011 have carried out 328 on-site inspections of each other’s strategic nuclear forces and exchanged 21,727 notifications of launcher movements and activities. Nearly 860 of those notifications were exchanged since September 2020.

Importantly, due to the Coronavirus outbreak, there have been no on-site inspections conducted since April 1, 2020. Instead, notification exchanges and National Technical Means of verification have provided adequate verification. Nonetheless, on-site inspection can hopefully be resumed soon.

This inspection and notification regime and record are crucial parts of the treaty and increasingly important for U.S.-Russian strategic relations as other treaties and agreements have been scuttled.

Looking Ahead

Although the New START treaty has been extended for five years and it appears to be working, that is no reason to be complacent. The United States and Russia should undertake detailed and ongoing negotiations about what a follow-on treaty will look like, so they are ready well before the five-year extension runs out. The incompetent and brinkmanship negotiation style of the Trump administration fully demonstrated the risks and perils of waiting to the last minute. The Biden administration can and should do better.

Additional information:

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NNSA Nuclear Plan Shows More Weapons, Increasing Costs, Less Transparency

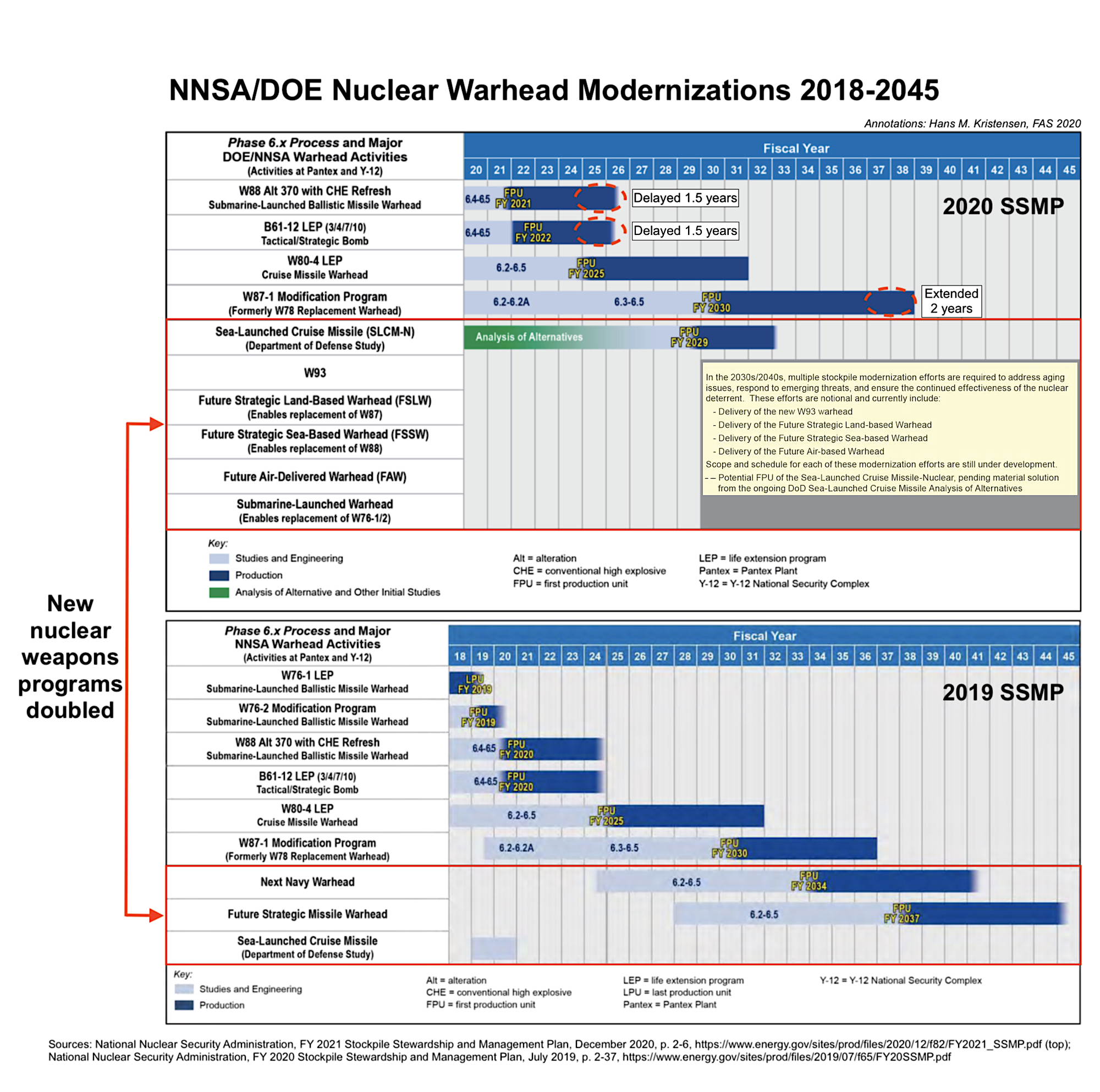

The National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA’s) new Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) doubles the number of new nuclear warhead programs compared with the previous plan from 2019. The plan shows nuclear weapons advocates taking full advantage of the Trump administration to boost nuclear weapon programs.

The new plan also shows significantly increasing nuclear weapons costs projected for the next two decades. These additional costs reflect the steadily growing ambitions of the nuclear modernization programs in response to the embrace of the Great Power Competition strategy articulated in the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy and Nuclear Posture Review.

Moreover, the 2020 SSMP significantly reduces the information available to the public about NNSA’s nuclear weapons activities by cutting by nearly half the size of the public version of the plan and omitting information that used to be included in previous SSMP reports.

More Nuclear Weapons

The new NNSA report doubles the number of new nuclear weapons modernization programs compared with the previous SSMP plan from 2019. This includes the recently reported W93 navy warhead, a new nuclear sea-launched cruise missile, and two future warheads that appear to be derived from what was previously called the Reliable Replacement Warheads. “In addition to these warheads,” the SSMP states, “a replacement air-delivered warhead and submarine-launched warhead (for the W76-1/2) will be needed in the 2040s.” Some of these future warheads were indicated in the DOD’s Nuclear Matters Handbook, which was published earlier this year.

The 2020 NNSA plan lists twice as many new nuclear weapons as the previous plan from 2019. Click on figure to view full size.

The navy gets four of the six new warheads. The first of these is the new nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N) advocated by the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review. Congress has funded a study for this weapon and NNSA plans to begin production in 2029, but it remains to be seen if the new Biden administration will continue it. If so, the missile might be equipped with a modified W80 cruise missile warhead (perhaps a W80-5 modification) for deployment on Virginia-class attack submarines.

The second navy warhead is the W93, which was announced by NNSA in February. Importantly, the W93 is not listed as a replacement for the W76 or W88 warheads, which are listed to be replaced by two other warheads, but as a supplement. This fits the description in the navy’s talking points on the new warhead.

The third navy warhead is the Submarine Launched Warhead (SLW) slated to replace the W76-1 and W76-2. This indicates that the SLW might have flexible yield settings to cover both the medium/high-yield mission of the W76-1 and the low-yield mission of the W76-2, or that they will produce two yield versions of it, or that the W76-2 mission will simply fall away.

The fourth navy warhead is the Future Strategic Sea-Based Warhead (FSSW), which is listed as a replacement of the W88, the highest-yield ballistic missile warhead, which is currently being life-extended under the Alt 370 program.

Four of the six new nuclear weapon programs listed in the new NNSA plan are for the US Navy. (Image: US Navy)

The ICBM force gets one new warhead – known as Future Strategic Land-Based Warhead (FSLW) – to replace the W87. It is unclear from the SSMP if the if the new warhead is intended to replace both versions of the W87 or only the W87-0. The W87-1 will still have a lot of life left in it in the 2040s, so it probably initially means replacing the W87-0. If it replaces both, then the ICBM force would go to a single warhead instead of the two currently arming it.

The bombers get a new weapon, known as the Future Air-Delivered Warhead (FAW). The weapon was previously known as the B61-13. The weapon is a follow-on to the B61-12, which will begin rolling off the projection line in late-2021.

The new warhead focus appears to continue the trend to somewhat break with the post-Cold War approach by moving away from simple life-extension of existing warheads to instead produce weapons based on significantly modified or even new designs with new military capabilities. The 2018 Nuclear Posture Review removed restrictions in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review on new warheads with new military capabilities. Instead, the 2020 SSMP more overtly justifies new requirement to be able to quickly design and produce new nuclear weapons with “enhanced military capabilities” and “responding to increased threats” in a Great Power Competition context.

The W93, for example, will “address the changing strategic environment” and “improve…flexibility to address future threats,” according to the SSMP. And the new future ballistic missile warheads will “support threats anticipated in 2030 and beyond.” Likewise, part of the justification to increase warhead pit production capacity to at least 80 pits per year is “Renewed competition among global powers that may lead to changes in deterrent requirements.”

Growing Costs

Underpinning all of these nuclear weapons maintenance and modernization plans is a sprawling nuclear weapons complex that is scheduled to increase significantly with new bomb-making factories and support facilities. This includes boosting the warhead pit production capacity at the Los Alamos National Laboratory and adding a second pit production factory at the Savannah River Site to produce no fewer than 80 new pits per year by 2030. The new pits will feed the W87-1 production and the new future warheads.

The NNSA budget began to increase during the Obama administration and the Trump administration has increased it significantly since and is proposing an additional increase of 19 percent in the FY2021 budget.

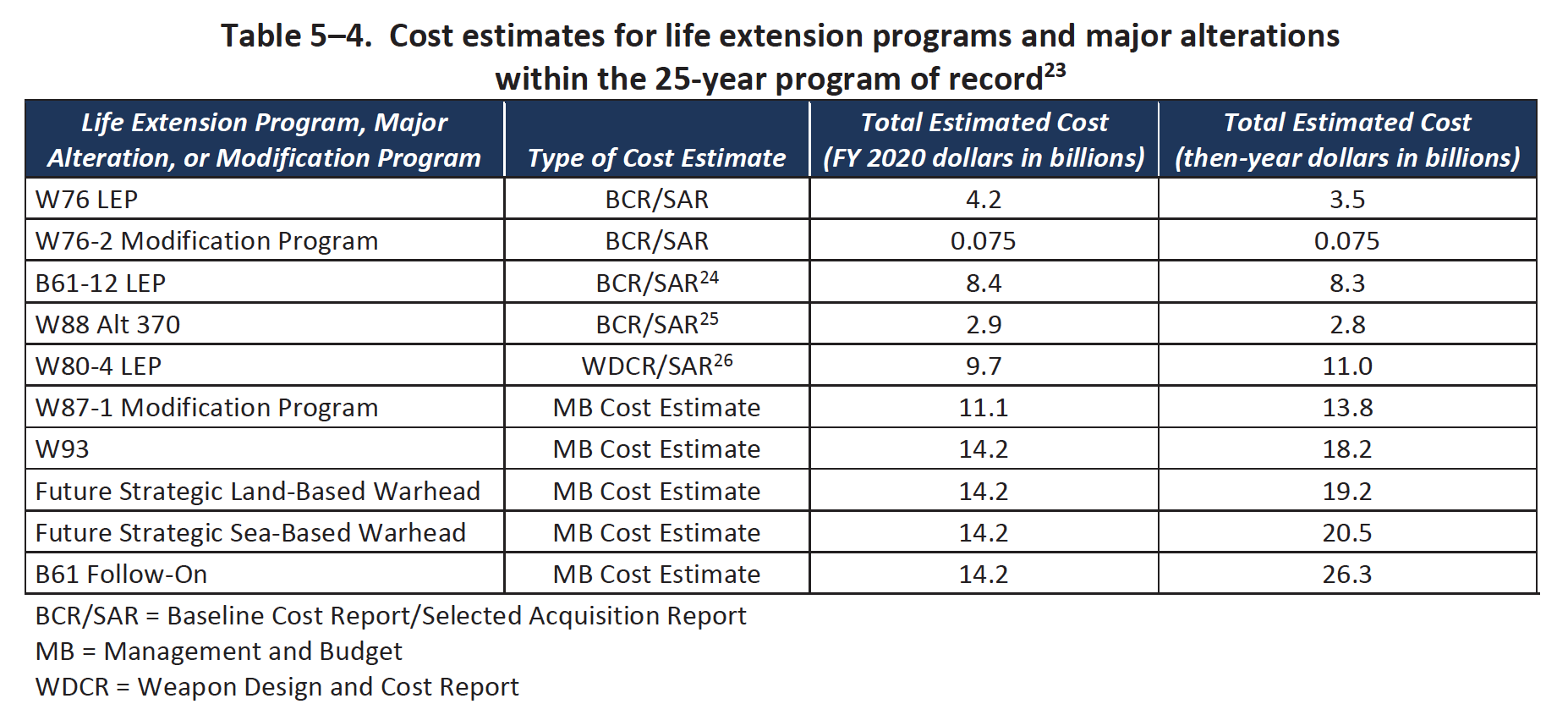

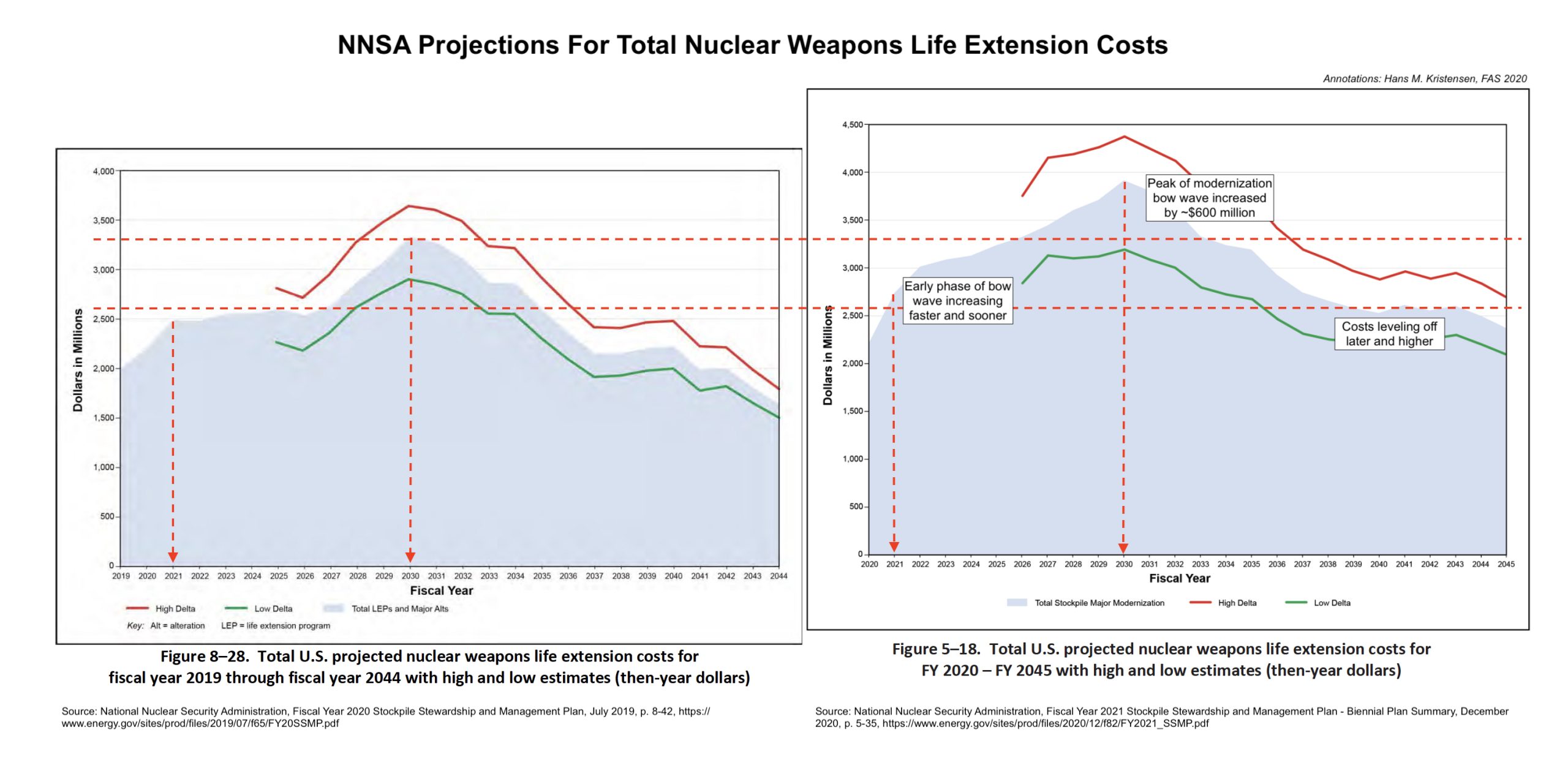

The trend is that warhead modernization programs are becoming more and more expensive. The current LEPs are twice as expensive as the W76-1 LEP, and the new warheads in the SSMP are projected to cost three-and-a-half times that amount (see figure below). Once the programs get underway, the early estimates will likely prove to be too low. The reason for this dramatic increase is that the nuclear laboratories and the military add more and more bells and whistles and new components to more advanced warhead designs that increase complexity and cost.

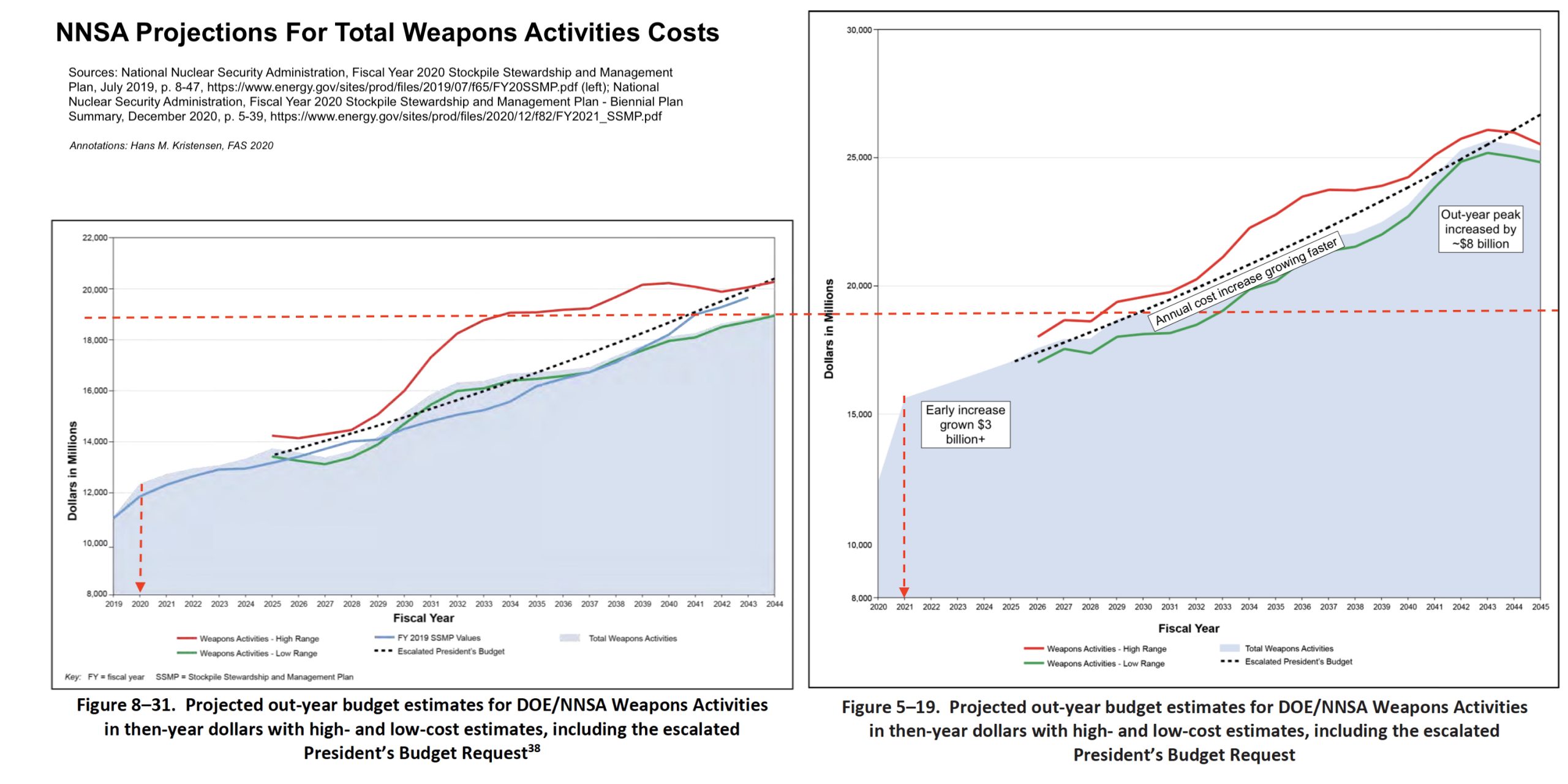

The 2020 SSMP shows increased costs for nuclear weapons life-extensions compared with the previous SSMP (in then-year dollars). A rough comparison of the two reports shows that the cost bow wave peak in 2030 is about $600 million higher than projected last year, the early phase of the bow wave increases faster and sooner, and the future costs are leveling off later and higher than projected in the 2019 report (see figure below).

NNSA cost projection for warhead life-extension programs is increasing. Click on figure to view full size.

Similarly, the cost projection for total Weapons Activities in the 2020 SSMP shows a significant increase across the board. The peak projected for the early-2040s has increased by approximately $8 billion, the increase in the early 2020s has increased by more than $3 billion, and the annual cost increase is growing faster than projected in the 2019 SSMP.

Reducing Nuclear Transparency

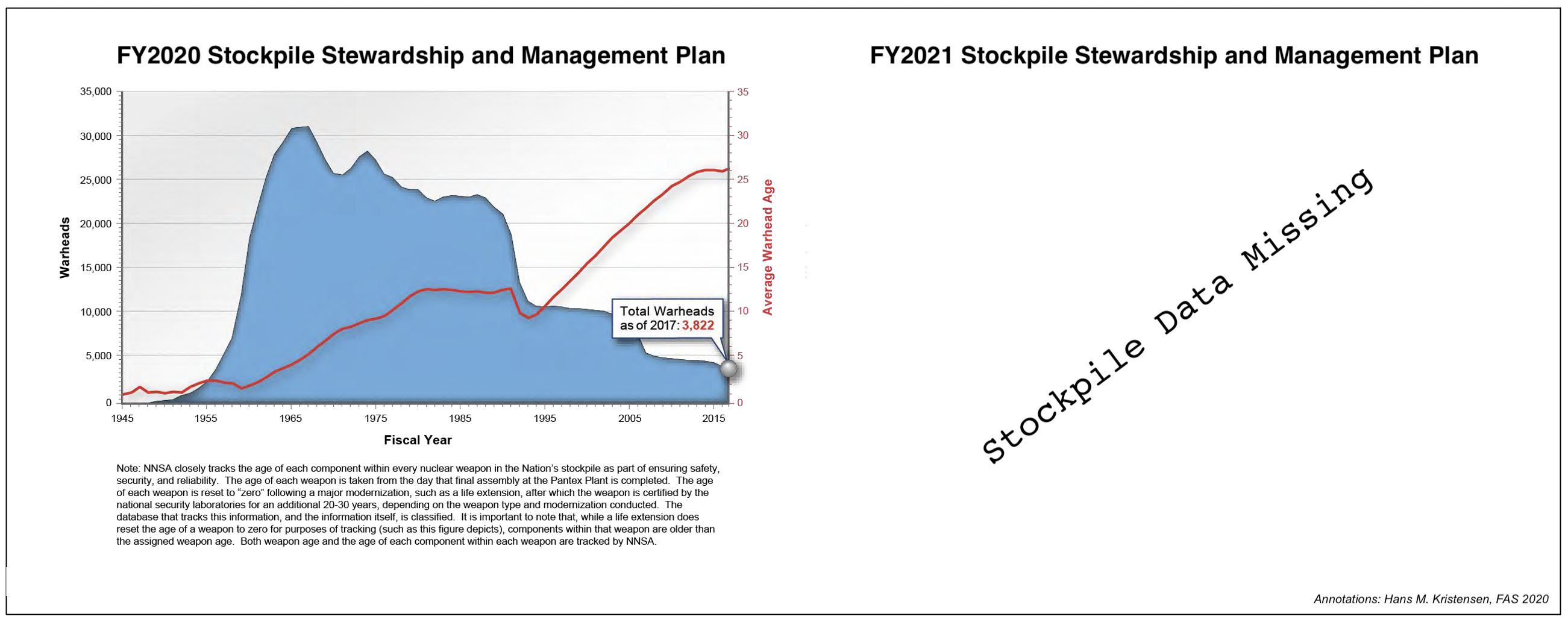

The 2020 SSMP significantly reduces nuclear weapons information made available to the public. Contrary to the 2019 SSMP, the new report is not a full report but a plan summary. It is only about half the size of 2019 SSMP (192 pages versus 364). Important information that was previously made available is not included at all or significantly reduced.

One example of omitted information is the United States nuclear weapons stockpile, which is completely missing from the new report. The 2019 SSMP included a chart that showed the history and size of the stockpile and the average age of stockpiled warheads. The omission of the stockpile data coincides with the Trump administration’s refusal to declassify the stockpile data for the past two years.

The new NNSA plan no longer includes nuclear weapons stockpile data. Click on image to view full size.

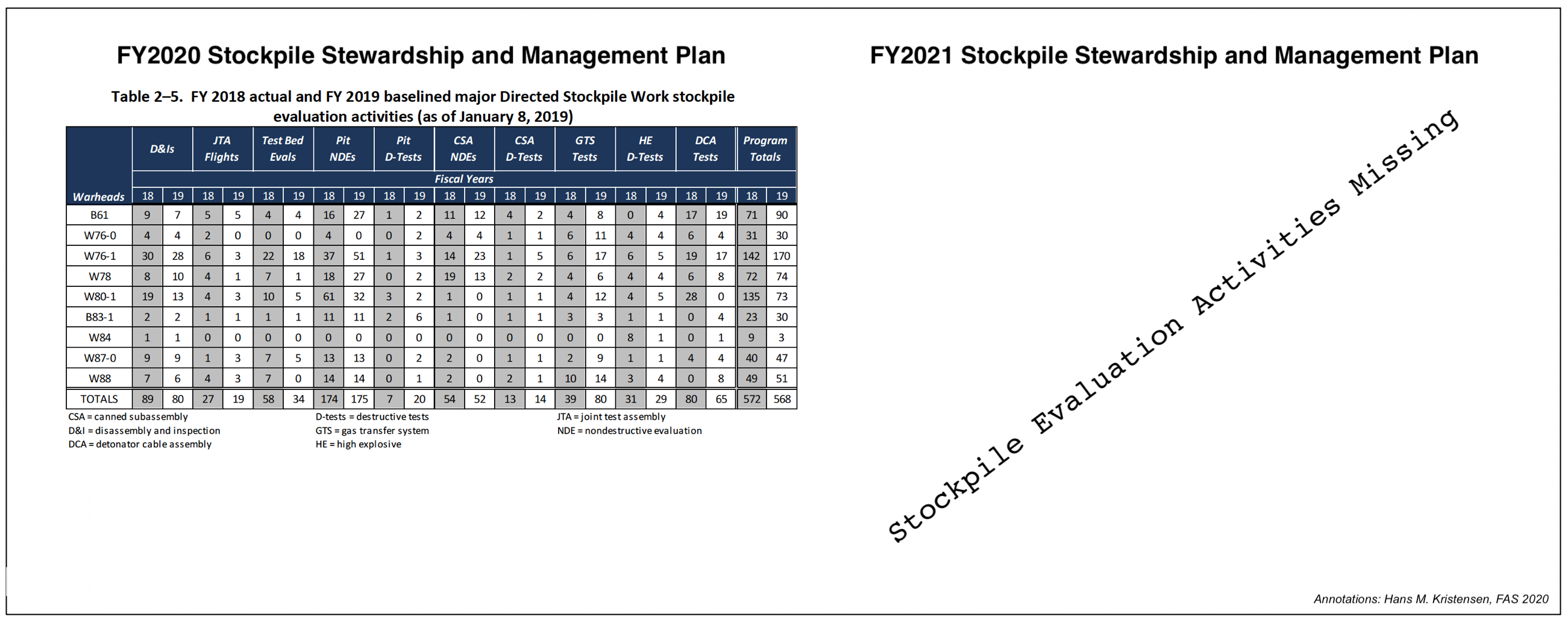

Another example of omitted information is data about warhead sustainment activities. The 2019 SSMP includes two charts that showed the number of such activities for each warhead as well as the total number of sustainment tests. Such information is not included in the 2020 version.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) deserves credit for publishing the 2020 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP). Other nuclear-armed states should follow the example to increase transparency of their nuclear weapons activities to avoid misunderstandings, reduce worst-case planning, and increase trust. That said, the new SSMP shows some concerning trends.

First, the plan shows a nuclear modernization program that goes well beyond modernizing the existing nuclear deterrent to increasing the types – and in the future potentially the number – of nuclear weapons and enhancing their military capabilities as part of growing competition with other nuclear-armed states.

Second, the plan shows nuclear weapon modernization programs where costs are not only increasing but doing so faster. The plan shows that NNSA anticipates that significant additional funding is required in the years ahead. The increased costs to the taxpayers come at a time when the US economy is buckling under the strain of the COVID-19 pandemic. And the nuclear modernization costs compete with funding for other high-priority programs.

Third, the NNSA plan continues a worrisome trend of increased secrecy by significantly reducing the type and amount of information previously made available in SSMP reports about nuclear modernization programs and activities. This reduces the public’s ability to monitor government programs, ask questions, and make informed decisions.

The 2020 SSMP is a timely reminder that the incoming Biden administration must trim and adjust the nuclear weapons modernization program to make it more affordable, sustainable, and justifiable. It must do so in a way that safeguards US national security and that of its allies while reducing international tension and military competition. Some adjustments can be unilateral, others bilateral, while some will require broader international cooperation.

Background information:

2020 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan – Biennial Plan Summary

2019 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan

FAS Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear forces, 2020

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Trump Administration Again Refuses To Disclose Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Size

The Trump administration has denied a request from the Federation of American Scientists to disclose the size of the US nuclear weapons stockpile and the number of dismantled warheads.

The denial was made by the Department of Defense Formerly Restricted Data Declassification Working Group (FDR DWG) in response to a petition from Steven Aftergood, director of the FAS Project on Government Secrecy, “that the Department of Energy (and the Department of Defense) authorize declassification of the size of the total U.S, nuclear stockpile and the number of weapons dismantled as of the end of fiscal year 2020.”

The decision to deny release of the data contradicts past US disclosure of such information, undercuts US criticism of secrecy in other nuclear-armed states, and weakens US ability to document its adherence to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. As Aftergood explained in the petition letter:

[su_quote]We believe that the reasons that led to the previous declassifications of stockpile information are still valid. The benefits of declassification are substantial while the detrimental consequences, if any, are insignificant.

As the first nuclear weapons state, the United States should strive to set a global example for clarity and transparency in nuclear weapons policy by disclosing its current stockpile size. Ambiguity is not helpful to anyone in this context.

Far from diminishing security, a credible USG account of its stockpile size both enhances deterrence and serves as a confidence building measure. Even if other nations do not immediately follow our lead, stockpile declassification sends a valuable message. And at a time when the future of US nuclear weapons policy is under discussion in Congress and elsewhere, stockpile disclosure also helps to provide a factual foundation for ongoing public deliberation.[/su_quote]

In its denial letter, the DOD Formerly Restricted Data Declassification Working Group (FDR DWG) did not respond to these points and gave no reason for the denial other than stating that “the information requested cannot be declassified at this time.”

Stockpile Size and Developments

The decision to deny declassification of the warhead stockpile and dismantlement numbers contradicts the publication of such data between 2010 and 2017 during which the Obama administration released annual numbers as well as the entire history of the stockpile size going back to 1945.

The decision also contradicts the decision in 2018 to declassify the data for 2017, the first year of the Trump administration.

In 2019, however, the Trump administration suddenly, and without explanation, decided to withhold the stockpile data.

The available data shows significant fluctuations in the size of the US stockpile over the years depending on how the various administrations increased or decreased the number of nuclear weapons. The graph below shows the size of the stockpile over the years and the in- and out-flux of warheads from the stockpile. As far as we can gauge, the stockpile has remained relatively stable for the past three years at around 3,800 warheads. And the number of warheads dismantled per year is probably currently in the order of 300-350.

The size of the US nuclear weapons stockpile has fluctuated considerably over the years but remained relatively stable during the Trump administration. Click on image to view full size.

Implications and Recommendations

The decision by the Trump administration to deny declassification of the nuclear weapons stockpile size and dismantlement numbers contradict release of such data in the past for no apparent reason.

The increased secrecy of the US nuclear weapons arsenal comes at a time when the Trump administration has been criticizing China for “its secretive, nuclear crash buildup…” The administration’s criticism would carry a lot more weight if it didn’t hide its own stockpile behind a “great wall of secrecy.”

In addition to undercutting the US ability to push for greater transparency among other nuclear-armed states, the decision to classify warhead stockpile and dismantlement data also weakens the ability of the United States to demonstrate good faith on its efforts to continue to reduce its nuclear arsenal in the context of the upcoming review conference of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The decision enables conspiracists to spread false rumors that the United States is secretly increasing its nuclear arsenal.

The incoming Biden administration should overturn the Trump administration’s excessive and counterproductive nuclear secrecy and restore transparency of the US nuclear warhead stockpile and dismantlement data.

Background Information:

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

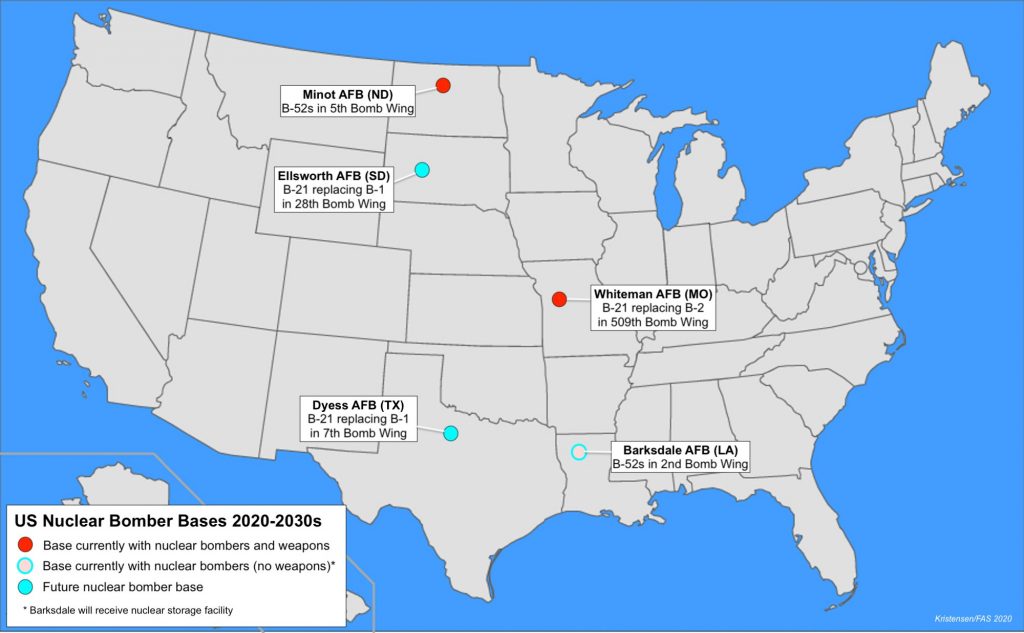

USAF Plans To Expand Nuclear Bomber Bases

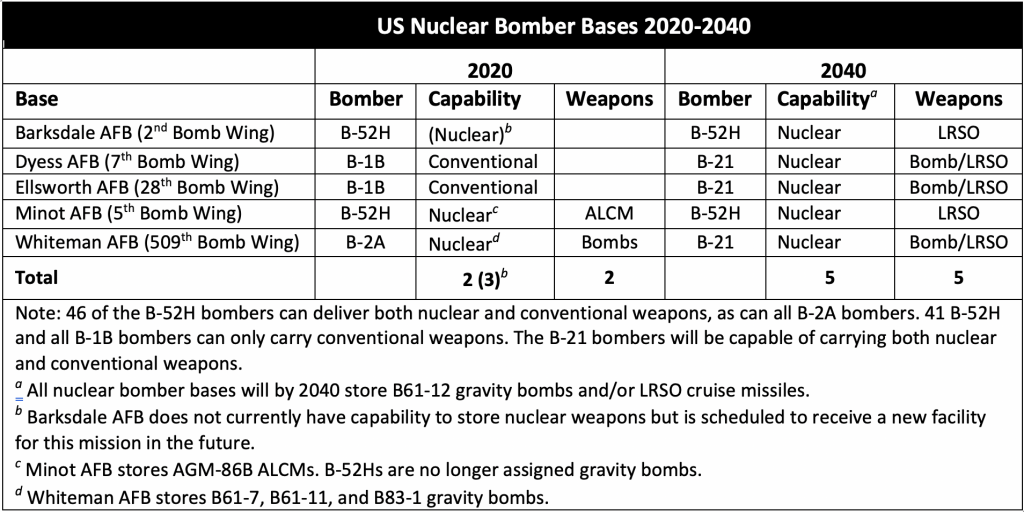

The US Air Force is working to expand the number of strategic bomber bases that can store nuclear weapons from two today to five by the 2030s.

The plan will also significantly expand the number of bomber bases that store nuclear cruise missiles from one base today to all five bombers bases by the 2030s.

The expansion is the result of a decision to replace the non-nuclear B-1B bombers at Ellsworth AFB and Dyess AFB with the nuclear B-21 over the next decade-and-a-half and to reinstate nuclear weapons storage capability at Barksdale AFB as well.

The expansion is not expected to increase the total number of nuclear weapons assigned to the bomber force, but to broaden the infrastructure to “accommodate mission growth,” Air Force Global Strike Command Commander General Timothy Ray told Congress last year.

Nuclear Bomber Base Expansion

The Air Force announced in May 2018 that the B-21 would replace the B-1B and B-2A bombers and be deployed at Ellsworth AFB, Dyess AFB, and Whiteman AFB. The commander of the strategic bomber force later explained in a video address to the B-1B bases that “the B-21 will bring significant changes to each location, to include the reintroduction of nuclear mission requirements.”

Since the B-1B was replaced in the nuclear war plan by the B-2A in 1997 and all B-1B bombers were denuclearized in 2011, the effect of the B-21 bomber program is that nuclear bomber operations will increase from the three bases today to five bases in the future (see map):

The Air Force plans to increase nuclear weapons storage capacity at bomber bases from two locations today to five in the future. Click map to view full size.

The Air Force previously planned for the B-21 to replace the B-2A no later than 2032 and the B-1Bs no later than 2036, though those dates may have shifted some since.

The effect of the integration of the B-21 is that bases with nuclear stealth bombers will increase from one today (Whiteman AFB) to three in the future.

The modernization plan also appears to significantly expand the location of nuclear cruise missiles from one base today (Minot AFB) to all five bomber bases by the late-2030s. The LRSO is scheduled to begin entering the arsenal in 2030 (see table):

The US Air Force plans a significant expansion of nuclear bomber bases and their capabilities. Click table to view full size.

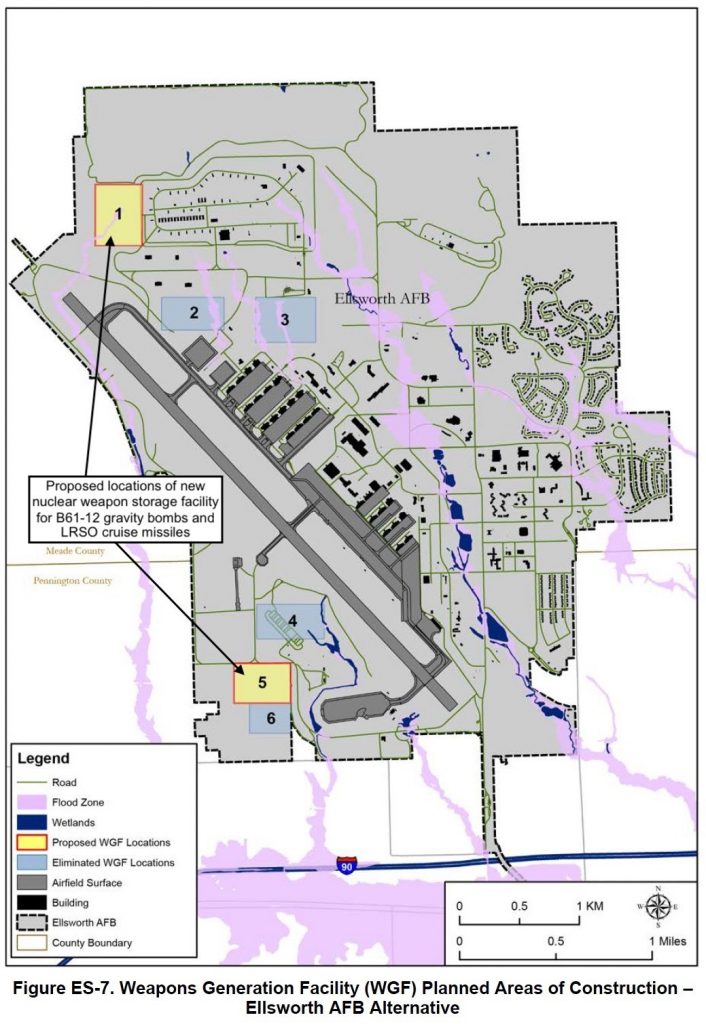

Nuclear Storage Facilities

A key element of the base upgrades to operate the B-21 involves the construction of a new nuclear weapons storage facility at each base: a Weapons Generation Facility (WGF). The new facility is different than the Weapons Storage Areas (WSAs) that that the Air Force built during the Cold War because it will integrate maintenance and storage mission sets into the same facility. The WGF will have a footprint of roughly 35 acres and include an approximately 52,000-square-foot (4,860 square meters) building as well as a 17,600 square-foot munitions maintenance building. The Air Force says the WGF will be “unique to the B-21 mission” and designed to provide a “safer and more secure location for the storage of Air Force nuclear munitions.”

An WGF is also under construction at F.E. Warren AFB for storage of ICBM warheads.

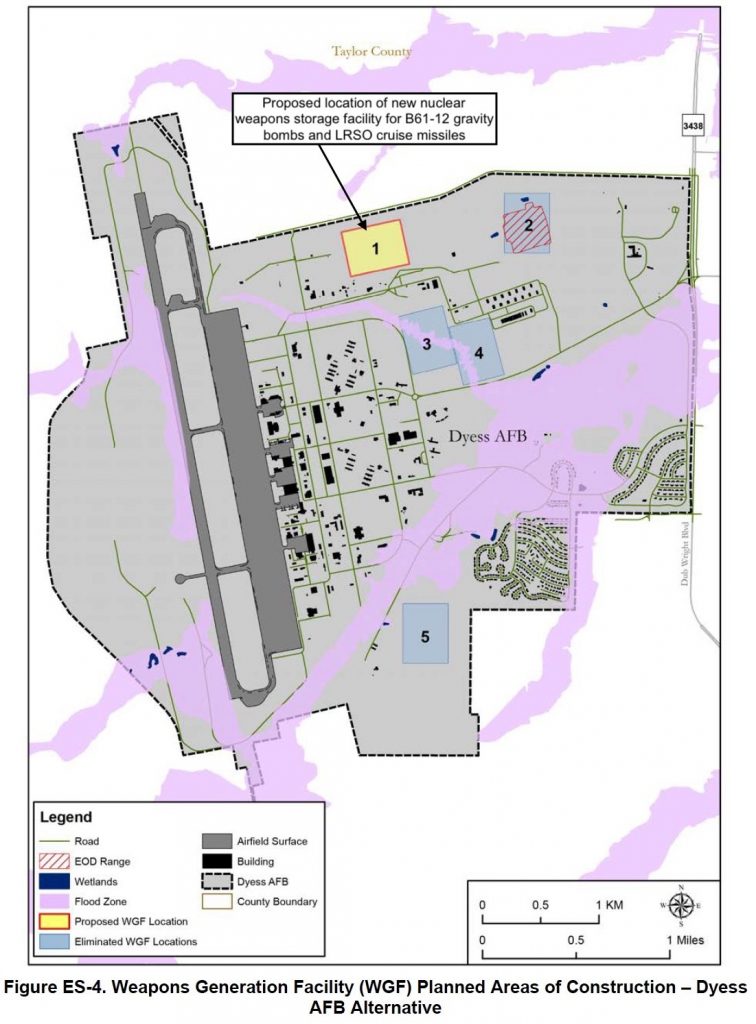

A draft Environmental Impact Statement recently posted by the Air Force shows the planned location of the nuclear weapons storage facility at Dyess and Ellsworth air force bases. At Dyess AFB, the intension is to build facility at the northern end of the base near the current munitions depot (see map below):

The Air Force plans to add nuclear weapons storage capacity to Dyess Air Force Base in Texas. Click on map to view full size.

At Ellsworth AFB, the Air Force has identified two preferred locations: one at the northern end near the munitions depot, and one at the southern end near the aircraft alert apron (see map below):

The Air Force plans to add nuclear weapons storage capacity to Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota. Click on map to view full size.

Although Barksdale AFB is not scheduled to receive the B-21, preparations are underway to reinstate the capability to store nuclear weapons at the base. The capability was lost when the Air Force last decade consolidated operational nuclear ALCM storage at Minot AFB. Once completed, the new WGF will enable the base to store nuclear LRSO cruise missiles for delivery by the B-52s.

Nuclear Bomber Force Increase

The B-21 bomber program is expected to increase the overall size of the US strategic bomber force. The Air Force currently operates about 158 bombers (62 B-1B, 20 B-2A, and 76 B-52H) and has long said it plans to procure at least 100 B-21 bombers. That number now appears [https://www.airforcemag.com/article/strategy-policy-9/] to be at least 145, which will increase the overall bomber force by 62 bombers to about 220. There are currently nine bomber squadrons, a number the Air Force wants to increase to 14 (each base has more than one squadron).

During an interview with reporters in April, the head of AFGSC, General Timothy Ray, reportedly said the 220 number was a “minimum, not a ceiling” and added: “We as the Air Force now believe it’s over 220.” Whether Congress will agree to pay for that many B-21s remains to be seen.

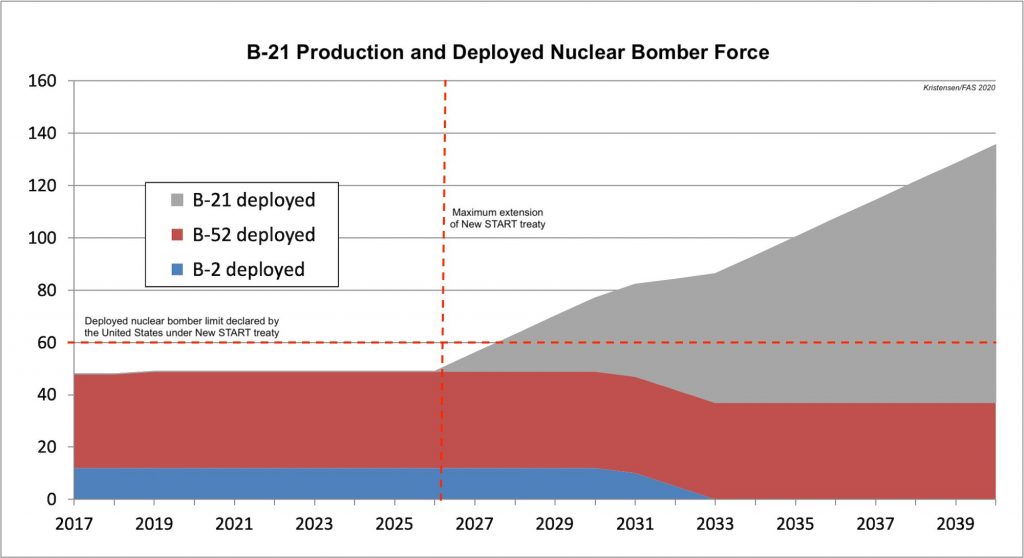

The fielding of large numbers of nuclear-capable B-21 bombers has implications for the future development of the US nuclear arsenal. Under the New START treaty, the United States has declared it will deploy no more than 60 nuclear bombers. Although the treaty will lapse in 2026 (after a five-year maximum extension), it serves as the baseline for long-term nuclear force structure planning.

Unless the Air Force limits the number of nuclear-equipped B-21 bombers to the number of B-2As operated today, the number of nuclear bombers would begin to exceed the 60 deployed nuclear bomber pledge by 2028 (assuming an annual production of nine aircraft and two-year delay in deployment of the first nuclear unit). By 2035, the number of deployed nuclear bombers could have doubled compared with today (see graph below):

Unless nuclear B-21 bombers are not limited, the future nuclear bomber force could significantly exceed the bomber force under the current New START treaty. Click graph to view full size.

It is difficult to imagine a military justification for such an increase in the number of nuclear bombers – even without New START. One would hope that the number of nuclear B-21s will be limited to well below the total number. Although the New START treaty would have expired before this becomes a a legal issue, it would already now send the wrong message to other nuclear-armed states about US long-term intensions, deepen suspicion and “Great Power Competition,” and could complicate future arms control talks.

In the short term, the incoming Biden administration should commit the United States to not increase the number of nuclear bombers beyond those planned under the New START treaty, and it should urge Russia to make a similar declaration about the size of its nuclear bomber force.

See also: Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear force, 2020

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Environmental Assessment Reveals New Details About the Air Force’s ICBM Replacement Plan

Any time a US federal agency proposes a major action that “has the potential to cause significant effects on the natural or human environment,” they must complete an Environmental Impact Statement, or EIS. An EIS typically addresses potential disruptions to water supplies, transportation, socioeconomics, geology, air quality, and other factors in great detail––meaning that one can usually learn a lot about the scale and scope of a federal program by examining its Environmental Impact Statement.

What does all this have to do with nuclear weapons, you ask?

Well, given that the Air Force’s current plan to modernize its intercontinental ballistic missile force involves upgrading hundreds of underground and aboveground facilities, it appears that these actions have been deemed sufficiently “disruptive” to trigger the production of an EIS.

To that end, the Air Force recently issued a Notice of Intent to begin the EIS process for its Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program––the official name of the ICBM replacement program. Usually, this notice is coupled with the announcement of open public hearings, where locals can register questions or complaints with the scope of the program. These hearings can be influential; in the early 1980s, tremendous public opposition during the EIS hearings in Nevada and Utah ultimately contributed to the cancellation of the mobile MX missile concept. Unfortunately, in-person EIS hearings for the GBSD have been cancelled due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic; however, they’ve been replaced with something that might be even better.

The Air Force has substituted its in-person meetings for an uncharacteristically helpful and well-designed website––gbsdeis.com––where people can go to submit comments for EIS consideration (before November 13th!). But aside from the website being just a place for civic engagement and cute animal photos, it is also a wonderful repository for juicy––and sometimes new––details about the GBSD program itself.

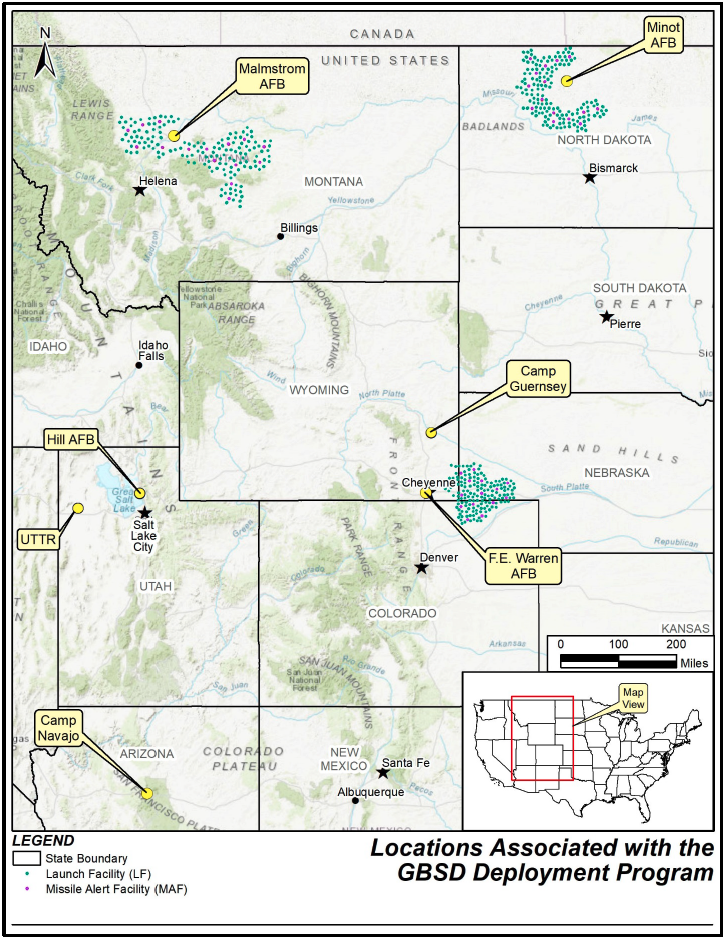

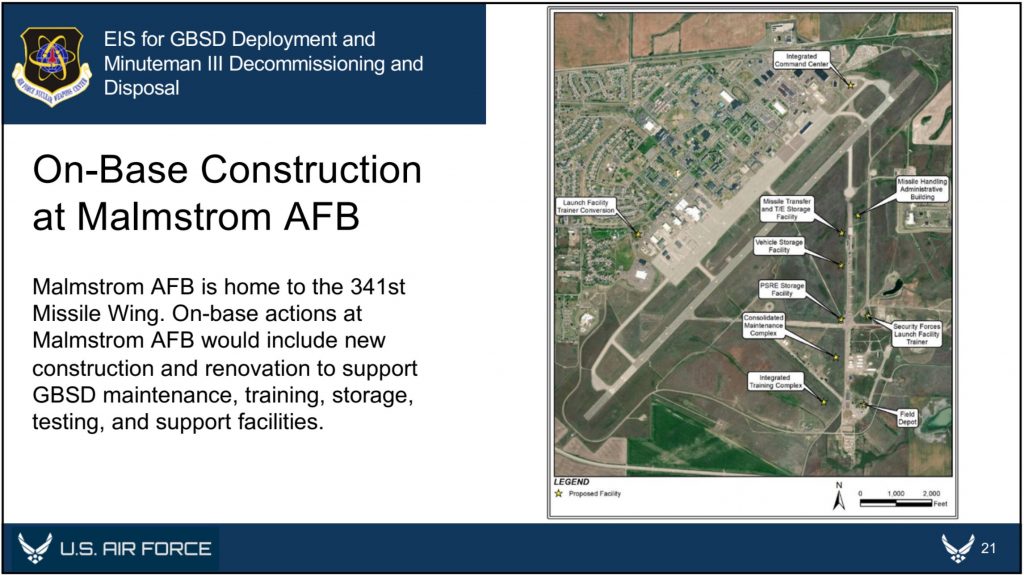

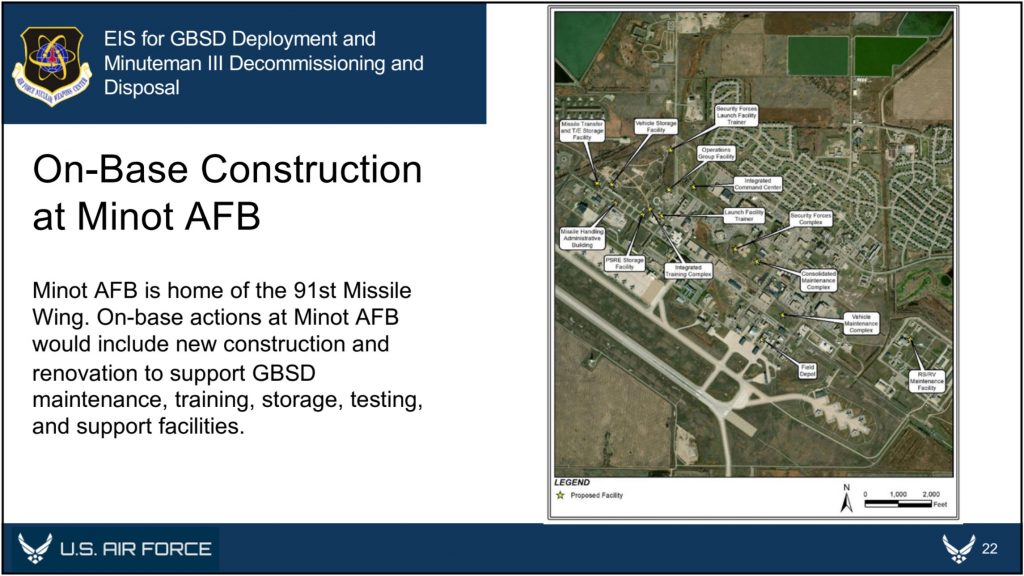

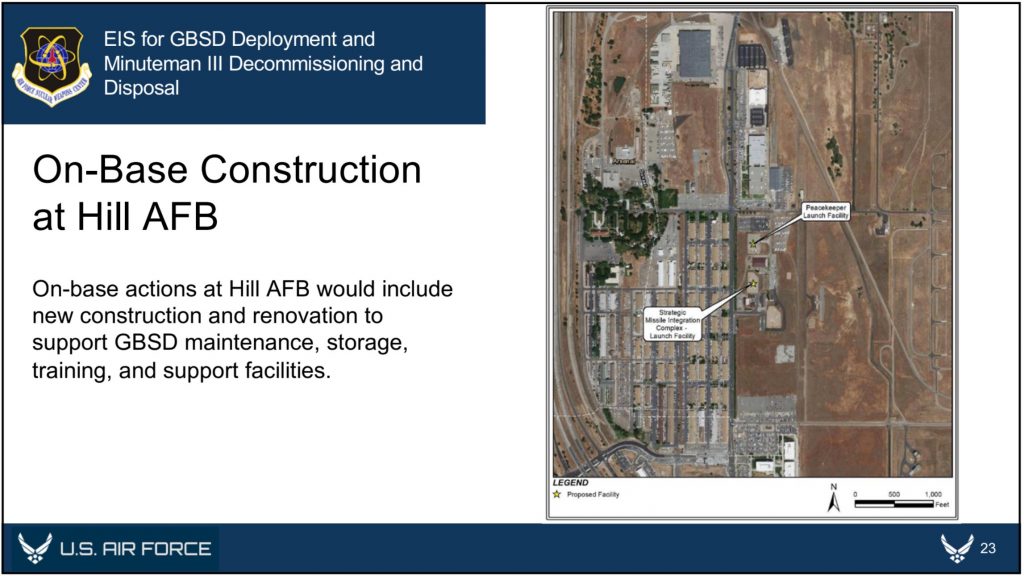

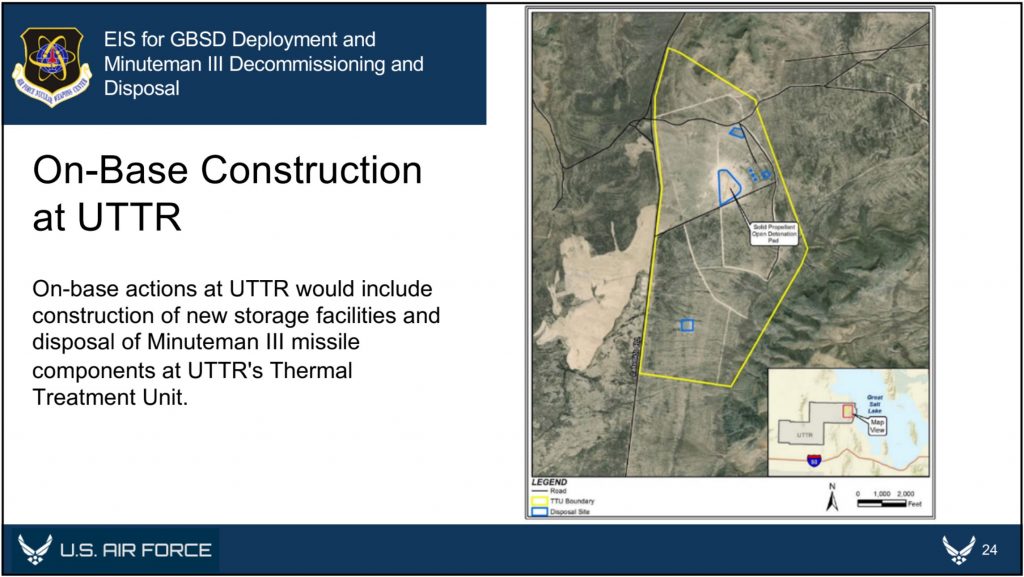

The website includes detailed overviews of the GBSD-related work that will take place at the three deployment bases––F.E. Warren (located in Wyoming, but responsible for silos in Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska), Malmstrom (Montana), and Minot (North Dakota)––plus Hill Air Force Base in Utah (where maintenance and sustainment operations will take place), the Utah Test and Training Range (where missile storage, decommissioning, and disposal activities will take place), Camp Navajo in Arizona (where rocket boosters and motors will be stored), and Camp Guernsey in Wyoming (where additional training operations will take place).

Taking a closer look at these overviews offers some expanded details about where, when, and for how long GBSD-related construction will be taking place at each location.

For example, previous reporting seemed to indicate that all 450 Minuteman Launch Facilities (which contain the silos themselves) and “up to 45” Missile Alert Facilities (each of which consists of a buried and hardened Launch Control Center and associated above- or below-ground support buildings) would need to be upgraded to accommodate the GBSD. However, the GBSD EIS documents now seem to indicate that while all 450 Launch Facilities will be upgraded as expected, only eight of the 15 Missile Alert Facilities (MAF) per missile field would be “made like new,” while the remainder would be “dismantled and the real property would be disposed of.”

Currently, each Missile Alert Facility is responsible for a group of 10 Launch Facilities; however, the decision to only upgrade eight MAFs per wing––while dismantling the rest––could indicate that each MAF could be responsible for up to 18 or 19 separate Launch Facilities once GBSD becomes operational. If this is true, then this near-doubling of each MAF’s responsibilities could have implications for the future vulnerability of the ICBM force’s command and control systems.

The GBSD EIS website also offers a prospective construction timeline for these proposed upgrades. The website notes that it will take seven months to modernize each Launch Facility, and 12 months to modernize each Missile Alert Facility. Once construction begins, which could be as early as 2023, the Air Force has a very tight schedule in order to fully deploy the GBSD by 2036: they have to finish converting one Launch Facility per week for nine years. It is expected that construction and deployment will begin at F.E. Warren between 2023 and 2031, followed by Malmstrom between 2025 and 2033, and finally Minot between 2027 and 2036.

Although it is still unclear exactly what the new Missile Alert Facilities and Launch Facilities will look like, the EIS documents helpfully offer some glimpses of the GBSD-related construction that will take place at each of the three Air Force bases over the coming years.

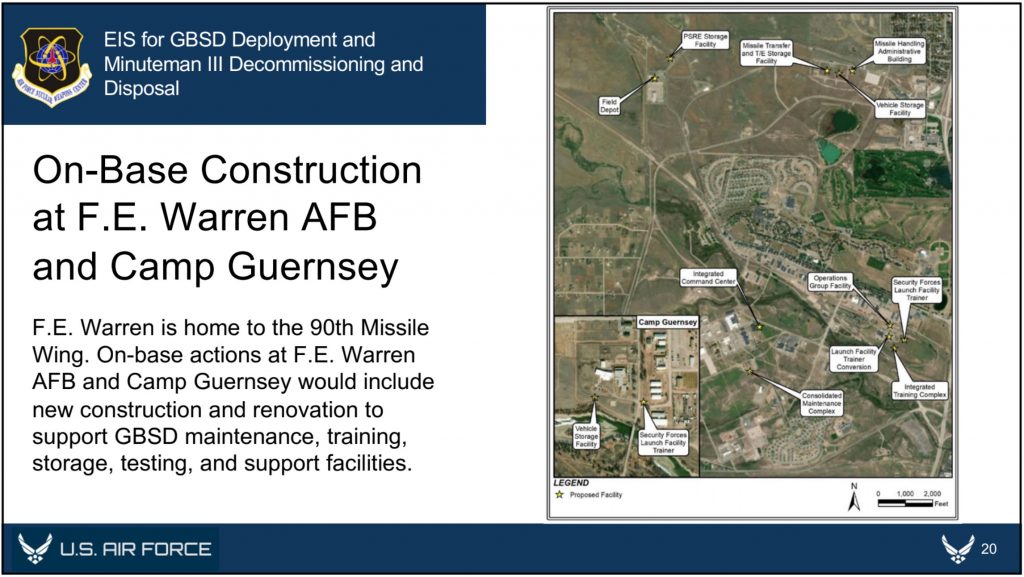

In addition to the temporary workforce housing camps and construction staging areas that will be established for each missile wing, each base is expected to receive several new training, storage, and maintenance facilities. With a single exception––the construction of a new reentry system and reentry vehicle maintenance facility at Minot––all of the new facilities will be built outside of the existing Weapons Storage Areas, likely because these areas are expected to be replaced as well. As we reported in September, construction has already begun at F.E. Warren on a new underground Weapons Generation Facility to replace the existing Weapons Storage Area, and it is expected that similar upgrades are planned for the other ICBM bases.

Finally, the EIS documents also provide an overview of how and where Minuteman III disposal activities will take place. Upon removal from their silos, the Minutemen IIIs will be transported to their respective hosting bases––F.E. Warren, Malmstrom, or Minot––for temporary storage. They will then be transported to Hill Air Force Base, the Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR), or Camp Najavo, in Arizona. It is expected that the majority of the rocket motors will be stored at either Hill AFB or UTTR until their eventual destruction at UTTR, while non-motor components will be demilitarized and disposed of at Hill AFB. To that end, five new storage igloos and 11 new storage igloos will be constructed at Hill AFB and UTTR, respectively. If any rocket motors are stored at Camp Navajo, they will utilize existing storage facilities.

After the completion of public scoping on November 13th (during which anyone can submit comments to the Air Force via Google Form), the next public milestone for the GBSD’s EIS process will occur in spring 2022, when the Air Force will solicit public comments for their Draft EIS. When that draft is released, we should learn even more about the GBSD program, and particularly about how it impacts––and is impacted by––the surrounding environment. These particular aspects of the program are growing in significance, as it is becoming increasingly clear that the US nuclear deterrent––and particularly the ICBM fleet deployed across the Midwest––is uniquely vulnerable to climate catastrophe. Given that the GBSD program is expected to cost nearly $264 billion through 2075, Congress should reconsider whether it is an appropriate use of public funds to recapitalize on elements of the US nuclear arsenal that could ultimately be rendered ineffective by climate change.

Additional background information:

- United States nuclear forces, 2020

-

Construction of New Underground Nuclear Warhead Facility At Warren AFB

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Image sources: Air Force Global Strike Command. 2020. “Environmental Impact Statement for the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent Deployment and Minuteman III Decommissioning and Disposal: Public Scoping Materials.”

US Officials Give Confusing Comparisons Of US And Russian Nuclear Forces

October 22, 2020 [updated]

In their effort to paint the New START treaty as insufficient and a bad deal for the United States and its allies, Trump administration official have recently made statements suggesting the treaty limits the US nuclear arsenal more than it limits the Russian arsenal.

New START imposes the same restrictions on US and Russian strategic nuclear forces.

During a virtual conference organized by the Heritage Foundation on October 13, Marshall Billingslea, special presidential envoy for arms control, stated: “What we’ve indicated to the Russians is that we are in fact willing to extend the New START Treaty for some period of time provided that they agree to a limitation, a freeze, in their nuclear arsenal. We’re willing to do the same. I don’t see how it’s in anyone’s interests to allow Russia to build up its inventory of these tactical nuclear weapons systems with which they like to threaten NATO…We cannot agree to a construct that leaves unaddressed 55 percent or more of the Russian arsenal.”

One week later, in an interview on National Public Radio, Billingslea added: “The New START treaty constraints…92 percent of the entire U.S. arsenal, of our deterrent” but “only covers 45 percent or less of the Russian arsenal…”

Finally, on October 21, Secretary of State Michal Pompeo repeated this talking point: “President Trump has made clear that the New START Treaty by itself is not a good deal for the United States or our friends or allies. Only 45 percent of Russia’s nuclear arsenal is subject to numerical limits, posing a threat to the United States and our NATO allies. Meanwhile, that agreement restricts 92 percent of America’s arsenal that is subject to the limits contained in the New START agreement.”

Pompeo and Billingslea didn’t specify what they meant by “arsenal” and the reaction from nuclear weapons analysts – ourselves included – was bewilderment. Most assumed “arsenal” was referring warheads, but the numbers don’t seem to fit with the percentages and descriptions in the statements. Interestingly, the percentages and categories seem to work better for launchers, unless one does a back-of-the-envelope calculation.

Matching Comparison With Warheads

Our first step was to analyze the statements and see if we could make them fit with our understanding of the size and composition of the nuclear arsenals. If we assume the percentages and descriptions refer to warhead numbers, then we see the following potential options:

Option 1: The 45% refers to New START warhead limit for deployed strategic warheads (1,550). If this were the case, then Russia’s entire stockpile would only consist of 3,445 warheads, which we doubt. Our estimate is 4,310. For the United States, 1,550 would only constitute 41% of the US stockpile, not 92% as stated by Billingslea.

Option 2: The 45% refers to the number of strategic warheads that can be loaded onto ICBMs and SLBMs but not bomber weapons. New START counts actual numbers of warheads on deployed ICBMs and SLBMs, but not those on bomber bases. According to our estimate of Russian forces, their ICBMs can load 1,136 warheads and SLBMs can load 720 warheads, a total of 1,856 warheads. That would constitute 43% of the total stockpile of 4,310 warheads (our estimate). It would of course be embarrassing if the US officials have been using our numbers instead of those of the US Intelligence Community. Even so, that methodology does not fit with the 92% comparison used for the United States. US ICBMs and SLBMs can load a maximum of 2,720 warheads, by our estimate, or 72% of the stockpile. And Billingslea explicitly says the US comparison includes the “entire” arsenal.

Option 3: The 45% refers to the total number of strategic warheads in the Russian arsenal (deployed and non-deployed). If that were the case, then the remaining 55% of 3,025 warheads would be non-strategic warheads, far more than the “up to 2,000” stated in the Nuclear Posture Review. And it would imply a total stockpile of 5,500 warheads, far more than the number of warhead spaces on launchers.

Option 4: The percentage numbers come from a simplistic back-of-the-envelope calculation. The Russian 45% is 1,550 (New START limit) / 1,550 (reserve) + 2,000 (tactical). The US 92% is 1,550 (New START limit) / 1,550 (reserve) + 150 (tactical). Those numbers don’t fully match the stockpiles and statements but can explain the comparison. (We are indebted to Pavel Podvig for suggesting this option.)

Billingslea and Pompeo both compared the Russian restrictions to those affecting the US arsenal, but they described it differently.

Billingslea said New START “constraints…92 percent of the entire U.S. arsenal, of our deterrent…” (emphasis added). Since we know the approximate size of the total US stockpile (about 3,800 warheads), 92% would constitute 3,496 warheads, far more than the treaty’s limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads. But the count would be close to the number of strategic warheads that can be loaded onto strategic launchers (3,570 by our estimate), leaving about 300 non-strategic warheads.

Pompeo said that New START “restricts 92 percent of America’s arsenal that is subject to the limits” (emphasis added), which is different than what Billingslea said because it doesn’t appear to include non-deployed strategic warheads or tactical warheads, two categories that are not subject to the treaty limits.

Matching Comparison With Launchers

Our next step was to analyze the statements to see how they compare with the number of launchers that can deliver nuclear warheads. New START limits both sides to no more than 800 strategic launchers in total, of which no more than 700 can be deployed at any given time.

In the latest set of aggregate numbers released by the US State Department, the United States is listed with exactly 800 launchers in total, of which 675 are deployed. Russia is listed with a total of 764 launchers, of which 510 are deployed.

While complaining about limits on US and Russian weapons, neither Billingslea nor Pompeo mentions this US strategic advantage of 165 deployed launchers, a number that exceeds the number of Minuteman IIIs in one missile wing and corresponds to more than half of the entire Russian ICBM force.

For the United States, if the 800 total strategic launchers constitute 92% of all US nuclear launchers (“entire” arsenal), then that would imply the existence of another 70 launchers, which potentially could refer to non-strategic fighter-bombers assigned missions with gravity bombs.

For Russia, if the 764 total strategic launchers constitute 45% of all its nuclear launchers, that would potentially imply that Russia has 1,698 total nuclear launchers, of which 934 would be launchers of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

We don’t yet know if this is the case. But the percentages mentioned by Billingslea and Pompeo appear to fit better if they refer to launchers than warheads, unless one applies the Option 4 calculation described above. The Trump administration has been particularly critical about Russia’s development of new types of strategic-range weapons that are not covered by the New START treaty, just like it has criticized that Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons are not covered by any arms control agreement.

Context and Recommendations

The comparisons and descriptions of Russian and US nuclear forces presented by Billingslea and Pompeo are confusing. Some might suspect “fuzzy math” but until we see otherwise, we suspect the comparisons use real data. Option 4 above might represent the most likely explanation although it doesn’t fully match the stockpiles and descriptions provided by the officials.

When it comes to nuclear negotiations, it is incredibly important to be precise with official words and statements, in order to avoid misunderstandings or mischaracterizations. Unfortunately, the Trump administration has a habit of cherry-picking or spinning statistics in an apparent attempt to make existing and equitable arms control agreements seem like “bad deals” for the United States. Given this track record, we should view their statements here with skepticism and ask for clarification if they’re referring to warheads or launchers. We have done so but have not yet heard back from the State Department.

A one-year extension of New START is better than no extension, but it’s worse than a five-year extension because it creates uncertainty about the commitment to continue to limit force levels and unnecessarily shortens the time available to negotiate follow-on arrangements. There is no technical need to shorten the extension. If a new deal is made, the old one will fall away.