Urgent: Move US Nuclear Weapons Out Of Turkey

Should the U.S. Air Force withdraw the roughly 50 B61 nuclear bombs it stores at the Incirlik Air Base in Turkey? The question has come to a head after Turkey’s invasion of Syria, Erdogan’s increasingly authoritarian leadership and deepening discord with NATO, Trump’s inability to manage U.S. security interests in Europe and the Middle East, and war-torn Syria only a few hundred miles from the largest U.S. nuclear weapons storage site in Europe.

According to The New York Times, State and Energy Department (?) officials last weekend quietly reviewed plans for evacuating the weapons from Incirlik. “Those weapons, one senior official said, were now essentially Erdogan’s hostages. To fly them out of Incirlik would be to mark the de facto end of the Turkish-American alliance. To keep them there, though, is to perpetuate a nuclear vulnerability that should have been eliminated years ago.”

That review is long overdue! [Actually, I’ve heard there have been several reviews and a lively internal debate since the 2016 coup attempt.] Some of us have been calling for withdrawal for years (see here and here), but officials have resisted saying it wasn’t as bad as it looked and that the deployment still served a purpose. They were wrong. And by waiting so long to act, the United States has painted itself into a corner where the choice between nuclear security and abandoning Turkey has become unnecessarily stark and urgent.

The situation is even more untenable because Incirlik in just a few years is scheduled to receive a large shipment of the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb, which would be a recommitment to nuclear deployment in Turkey.

This year is the 60th anniversary of the first deployment of nuclear weapons to Turkey. It is time to bring them home.

Nuclear Weapons At Incirlik

The specific reference in the New York Times article made by officials to nuclear weapons at Incirlik is the most recent and authoritative confirmation that nuclear weapons are still stored at the base. That confirms what I have been hearing and sources at US Air Forces Europe confirmed the report, telling William Arkin the weapons are still there. There have been rumors the weapons were removed after the coup attempt in 2016 (and some really bad disinformation that they had been moved to Romania). All of those rumors were wrong. An article on the official Incirlik Air Base web site even confirms that the mission of the 39th Operations Support Squadron is “to orchestrate and control US, Turkish, and coalition forces operating at Incirlik Airbase in the execution of full-spectrum airpower and nuclear deterrent operations” (emphasis added). Given that the article will likely be removed now that I have pointed this out, it is reproduced in full below:

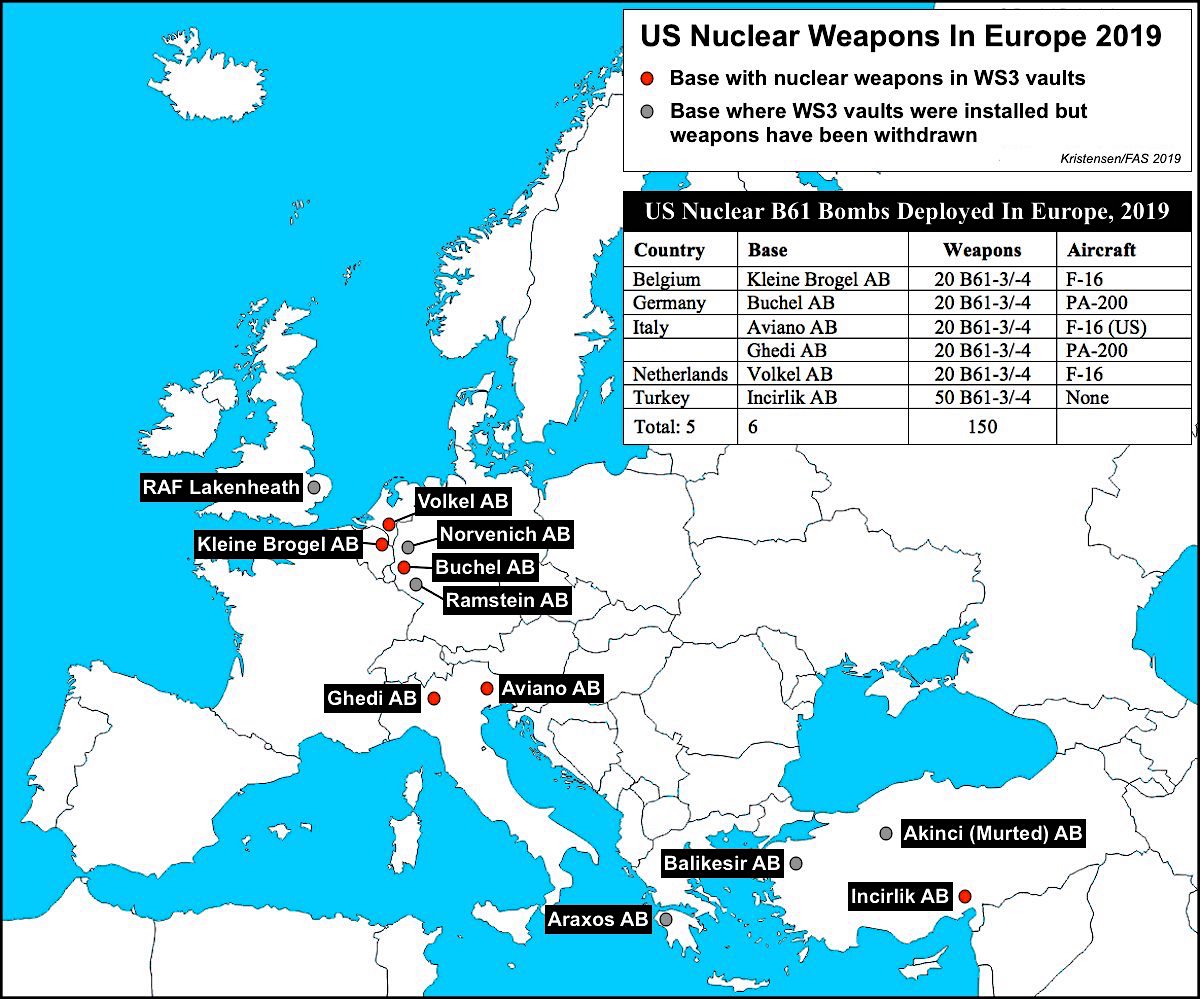

I have estimated for the past several years that the Air Force stores about 50 B61 nuclear gravity bombs at Incirlik, one-third of the 150 nuclear weapons currently deployed in Europe (see figure below). This estimate has been used by a wide range of news reports and commentators. The number of bombs at Incirlik has decreased over the past two decades from 90 in 2000. In those days, 40 of the 90 bombs were earmarked for delivery by Turkish F-16s. Those 40 bombs used to be stored in 6 vaults at both Akinci AB and Balikesir AB (20 at each) until they were moved to Incirlik when the US Air Force withdrew its Munition Support Squadrons from the Turkish bases in 1996. The 40 “Turkish” bombs remained at Incirlik until around 2005 when they were shipped back to the United States as part of the Bush administration’s unilateral nuclear reduction in Europe.

The US Air Force stores 150 nuclear bombs at six bases in five NATO countries. Click on map to view full size.

The remaining 50 bombs are for use by US jets, even though Turkey never allowed the US Air Force to permanently base fighter-squadrons at Incirlik. Jets would have to fly in during a crisis to pick up the weapons or they would have to be shipped to other locations before use. As a result, the nuclear posture at Incirlik has been more a storage site than a fighter-bomber base during the past two decades.

Although the Turkish participation in the NATO nuclear sharing mission was lessened (some would say mothballed) by the withdrawal of the “Turkish” weapons, the Turkish F-16s continued to serve a nuclear role. Despite local reports that F-16s never had a nuclear role, the US Air Force in 2010 informed Congress that “Turkey uses Turkish F-16s to execute their nuclear mission,” and that some of the F-16s would be upgraded to be able to deliver the new B61-12 bomb until the F-35A could take over the nuclear strike mission in the 2020s. That is now not going to happen after the Trump administration canceled the F-35 sale.

In 2015, satellite images revealed construction of a new security perimeter around most of the aircraft shelters with nuclear weapons storage vaults. Of the 25 shelters that originally were equipped with vaults, only 21 were included in the new security area with a capacity to store up to a maximum of 84 nuclear bombs. Normally only about two bombs are stored in each vault, for a total of inventory of 40-50 bombs at Incirlik.

The nuclear weapons mission areas at Incirlik AB include the “NATO Area” where nuclear weapons are stored and the nuclear weapons maintenance unit that manages the underground storage vaults

As recently as last month, Vice Chief Staff of the Air Force, Gen. Stephen W. Wilson, visited Incirlik and was given tours of the various functions and facilities at the base. One of these was Protective Aircraft Shelter H-2 inside the “NATO Area” where he spoke to members of the 39th Security Force that protects the nuclear weapons (see below). He was likely also shown the inside of the shelter and the weapons in the vault.

Last month, the Air Force Chief of Staff was taken to a nuclear weapons storage shelter at Incirlik AB. Click on image to view full size.

Recent Activities

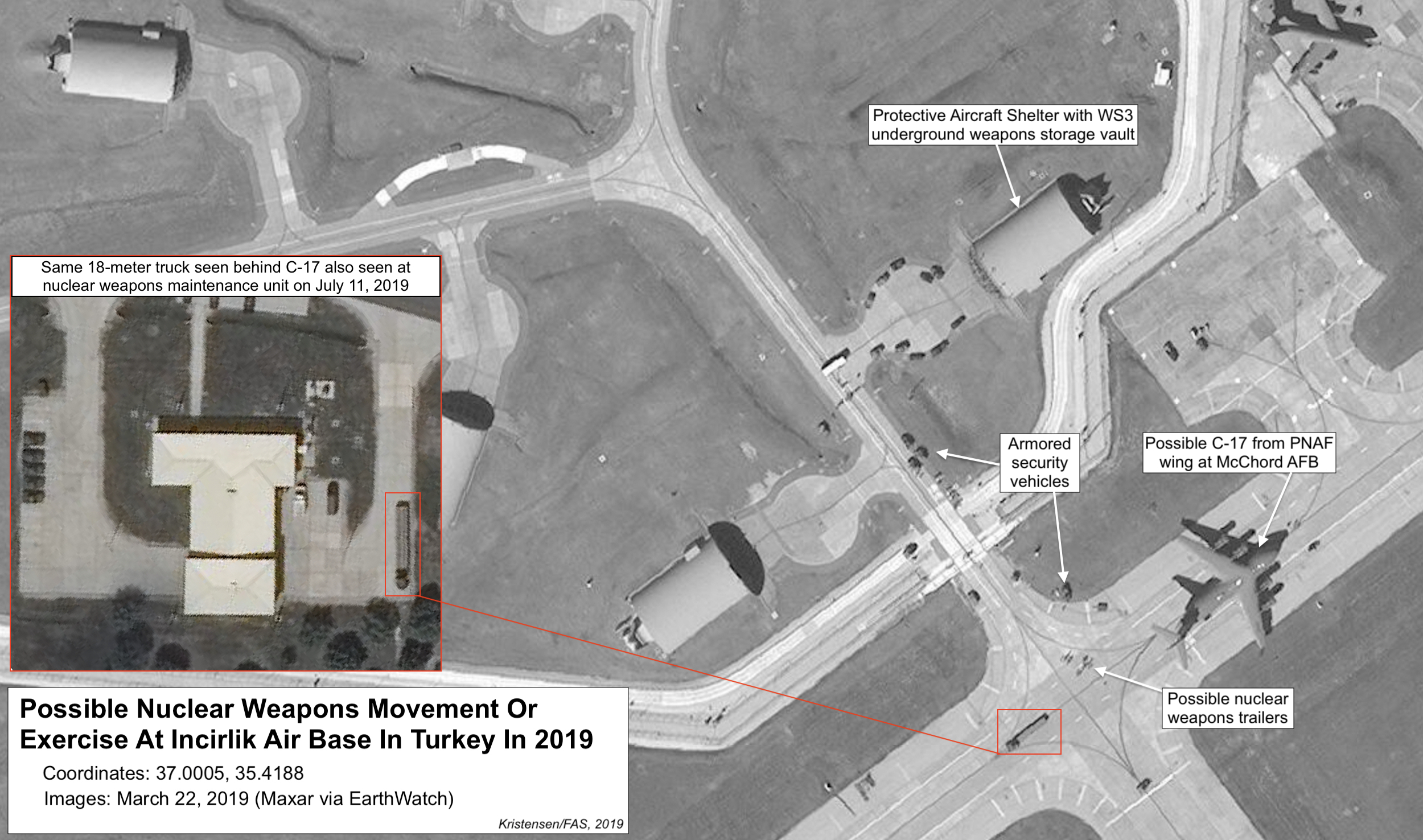

If the Air Force decided to withdraw the B61 bombs from Incirlik, it would look pretty much like activities captured by Maxar’s satellites in 2019 and 2017. Those images show what appears to be either actual nuclear weapons movements or training to remove them.

One photo from March 22, 2019, shows a C-17 transport aircraft – likely from the 4th Airlift Squadron of the 62nd Airlift Wing at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington – parked right outside the main gate to the NATO Area. The 4th Airlift Squadron, which is the only unit in the Air Force that is qualified to airlift nuclear weapons, flies Prime Nuclear Airlift Force (PNAF) and Emergency Nuclear Airlift Operations (ENAO) missions (see images below).

The satellite image shows the C-17 and gate area surrounded by armored vehicles and armed guards of the 39th Security Force as well as technicians to protect and carry out the weapon movement. One of the unique vehicles seen is an 18-meter truck lined up with the loading pad of the C-17. The same type of truck can be seen parked at the weapons maintenance unit building a few months later (see image below).

This Maxar satellite image acquired via Earth Watch shows what appears to be a nuclear weapons movement or exercise in March 2019. Click on image to view full size.

Another set of Maxar satellite photos of a possible nuclear weapons movement or exercise is from December 2017. A Nuclear Security Inspection that year (and 2014) reportedly included weapons emergency evacuation drills. The scenario on the 2017 image is similar to that on the 2019 image: a C-17 parked outside the gate, security vehicles surrounding the scene, and transporters for moving weapons. But the 2017 photos are unique because they were taken moments apart as the satellite passed overhead. As a result, movements become visible: On the first image, a possible weapons trailer towed behind a truck in a column of armored security vehicles is moving toward the outer gate of the NATO Area. On the second photo, the column has passed through the gate onto the tarmac and the towed trailer is turning toward the rear of the C-17. The aircraft shadow shows the loading ramp is open and ready to receive the weapons (see image below).

This unique double-image shows what appears to be a nuclear weapons movement or exercise in December 2017. Click on image to view full size.

The Task At Hand: Withdraw The Weapons!

The B61 nuclear bombs at Incirlik should have been withdrawn long ago but tradition, Cold War thinking, and bureaucratic inertia prevented officials from doing the right thing. Now things have come to a head where the United States is faced with the choice of securing its weapons or be seen as abandoning Turkey.

Withdrawing the weapons does not, of course, mean the United States is abandoning Turkey. That relationship is already in serious trouble and keeping the weapons at Incirlik based on the idea that it will somehow counterweight Turkey’s further drift away from NATO is probably an illusion. That boat seems to have sailed; the relationship is likely to deteriorate whether or not there are nuclear weapons at Incirlik. That is the reality the Air Force must relate to now.

Another argument against withdrawal will be that moving them out of Turkey will cause the other members of the so-called nuclear sharing arrangement (Belgium, Germany, Holland, Italy) to question why they should continue to store U.S. nuclear weapons. Withdrawal from Turkey could, so the argument goes, trigger a domino effect of withdrawal from other countries as well.

But the withdrawal of U.S. nuclear bombs from Greece in 2001 and from England five years later did not cause the other countries to demand withdrawal as well or the collapse of NATO. If they truly believe deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons is important for NATO security, then they will stay. If the mission falls with withdrawal from Turkey, then they obviously don’t think it’s important and the weapons should be withdrawn from all the countries anyway. The U.S. extended deterrence posture in Europe can adequately be maintained with advanced conventional forces backed up by strategic forced in the background.

The B61 bombs at Incirlik could easily be dispersed to empty storage vaults in the other countries. Space is not a problem. There are a total of 96 empty weapon slots in the active WS3 vaults in Belgium, Germany, Holland, and Italy. Moreover, there are 25 empty and inactive WS3 vaults with room for 100 bombs at RAF Lakenheath. But public and parliamentary opposition would likely prevent increasing the number of nuclear bombs stored in those countries. If the order goes out to evacuate Incirlik, it seems more likely the bombs would be returned to the United States.

There will be some people who will argue that deteriorating relations with Russia and Moscow’s alleged increased reliance on a so-called “escalate-to-deescalate” strategy of using tactical nuclear weapons first prevent the United States from reducing – certainly withdrawing – its tactical nuclear weapons from Europe. Those are curiously the same people who also argue that the United States should deploy a new low-yield warhead on its strategic submarines and a new nuclear cruise missile on its attack submarines to better counter Russian tactical nuclear weapons – a thinking that was recently endorsed by the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review. That seems to signal to the European allies that the United States actually no longer believes the deployment of B61 nuclear bombs in Europe is credible and that other and better weapons are needed.

Whatever one might think about U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe, Turkey is no longer an acceptable location. Erdogan’s confrontational and authoritarian leadership is rapidly undermining Turkey’s status as a reliable NATO ally, and the deteriorating security situation in the region presents a real physical threat to the weapons at Incirlik. That threat is real and the U.S. military sees it as real. So much so that an extra security force squadron deployed to Incirlik from Aviano Air Base in Italy to beef up nuclear security in response to “regional turmoil and government instability” according to USAF source, and Ohio Army National Guard military police reportedly were dispatched to Incirlik specifically to increase base security.

The security threat to the weapons at Incirlik is urgent and the continued deployment of nuclear weapons at the location is unjustifiable and incompatible with U.S. nuclear security standards. If you don’t believe that, ask yourself this question: If there were no U.S. nuclear weapons in Turkey and someone asked for them to be deployed to Incirlik, would the Pentagon approve?

I doubt it. It’s time to face reality and withdraw the weapons from Turkey before they have to be evacuated under fire.

Additional information:

- US nuclear weapons, 2019

- Tactical nuclear weapons, 2019

- Upgrades At US Bases In Europe Acknowledge Security Risk (2015)

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.