DOE 4.0: Rethinking Program Design for a Clean Energy Future

DOE’s mission and operations have undergone at least three iterations: starting as the Atomic Energy Commission after World War II (1.0), evolving into the Department of Energy during the 1970s Energy Crisis to focus on a wider range of energy research & development (2.0), and then expanding into demonstration and deployment over the last 20 years (3.0). The evolution into DOE 3.0 began with the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which authorized the Loan Programs Office (LPO), and accelerated with the infusion of funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Finally, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) crystallized DOE 3.0’s dual mandate to not only drive U.S. leadership in science and technology innovation (as under DOE 1.0 and 2.0), but also directly advance U.S. industrial development and decarbonization through project financing and other support for infrastructure deployment.

While DOE continues to support the full spectrum of research, development, demonstration, and deployment (RDD&D) activities under this dual mandate, the agency is now undergoing another transformation under the Trump administration, as a large number of career staff leave the agency and programs and budgets are overhauled. The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is launching a new initiative to envision the DOE 4.0 that emerges after these upheavals, with the goals of identifying where DOE 3.0 missed opportunities and how DOE 4.0 can achieve the real-world change needed to address the interlocking crises of energy affordability, U.S. competitiveness, and climate change.

Crucial to these goals is rethinking program design and implementation to ensure that DOE’s tools are fit for purpose. BIL and IRA introduced new types of programs and assistance mechanisms, such as Regional Hubs and “anchor customer” capacity contracts, to try to meet the differing needs of demonstration and deployment activities compared to R&D. Some were a clear success, while others faced implementation challenges. At the same time, the majority of funding from these two bills was still implemented using traditional grants and cooperative agreements, which did not always align with the needs of the commercial-scale projects they sought to support. Based on lessons learned from the Biden administration, this report provides recommendations to DOE to improve the implementation of different types of assistance and identifies opportunities to expand the use of flexible and novel approaches. To that end, this report also advises Congress on how to improve the design of legislation for more effective implementation.

The ideas and insights in this report were informed by conversations with former DOE staff who played a role in implementing many of these programs and experts from the broader clean energy policy community.

Distribution of BIL and IRA Funding

Before diving into program design, it’s helpful to first understand the range of technologies and activities that BIL and IRA programs were meant to address, especially where that funding was concentrated and where there may have been gaps, since programs should be tailored to the purpose.

Authorizations and Appropriations

Congress intentionally provided the lion’s share of BIL and IRA funding to demonstration and deployment activities. The table above shows the distribution of BIL and IRA authorizations and appropriations for DOE. The table excludes DOE’s revolving loan programs – the Tribal Energy Financing Program (TEFP), the Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loan Program (ATVM), the Title XVII Innovative Energy Loan Guarantee Program (Title 1703), the Title XVII Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Financing Program (Title 1706) – which are discussed in the following section.1 The Carbon Dioxide Transportation infrastructure Finance and Innovation program (CIFIA) was included in the table above because that program’s appropriations could be used for both grants and loan credit subsidies.

The technology areas that received the most DOE funding from BIL and IRA (excluding loans) were building decarbonization, grid infrastructure, clean power – combining solar, wind, water, geothermal, and nuclear power, energy storage systems, and technology neutral programs – carbon management, and manufacturing and supply chains, which each received over $10 billion in funding.

Below is a breakdown of the funding distribution for each sector/technology.

Grid Infrastructure received a total of $14.9 billion, second only to building decarbonization. All of the funding went towards demonstration and deployment programs, the majority ($10.5 billion) of which went towards the Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnerships (GRIP) program. The remainder of the funding went towards Grid Resilience State and Tribal formula grants, the Energy Improvement in Rural and Remote Areas, Transmission Facilitation Program, and transmission siting and planning programs. No funding went to R&D or workforce programs. Grid infrastructure was also eligible for the Title 17 and Tribal loans programs.

Power Generation received a total of $13.2 billion, with funding unevenly distributed across technologies and stages of innovation. Nuclear power received the largest share, with over $9.2 billion allocated to the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program and the Civil Nuclear Credit Program, supporting demonstration of advanced reactors and production incentives to maintain existing nuclear plants, respectively. Geothermal energy received the least funding among power generation technologies, with only $84 million allocated to the Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) Demonstration Program and no other support for R&D or deployment.

Modest amounts were provided for RD&D in solar ($80 million), wind ($100 million), and water power technologies ($146 million). For deployment, hydropower also received production and efficiency incentives to support existing facilities ($754 million); wind energy received funding for Interregional and Offshore Wind Electricity Transmission Planning and Development ($100 million); and solar qualified for the Renew America’s Schools program ($500 million). To complement these technologies, $505 was provided for energy storage demonstration programs to enable reliable deployment of variable renewables.

Power generation was also eligible for the Title 17 and Tribal loan programs.

Manufacturing and Supply Chains received $10.8 billion in funding from BIL and IRA. The majority of that funding, $6.3 billion, went towards battery supply chains, primarily for the Battery Materials Processing Program ($3 billion) and the Battery Manufacturing and Recycling Program ($3 billion). Additional focus areas for funding included EV manufacturing ($2 billion), advanced energy manufacturing and recycling ($750 million), high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) supply chains for nuclear power plants ($700 million), and heat pump manufacturing ($250 million). Energy manufacturing and supply chains are eligible for Title 1703 loans, while EV and battery manufacturing and supply chains are eligible for ATVM loans.

Critical Minerals received a total of $6.9 billion, of which $6 billion was allocated for the Battery Materials Processing Program and the Battery Manufacturing and Recycling Program, which funded demonstration and commercial-scale critical minerals processing and recycling projects. The remainder of the funding went to R&D programs on mining, processing, and recycling technologies; technologies to recover critical minerals from coal-based industry, mining and mine waste, and other industries; and technologies that use less critical minerals or replace them with alternatives. Critical minerals were also eligible for all of DOE’s revolving loan programs, except for CIFIA.

Industrial Decarbonization and Efficiency received a total of $7.5 billion. Six ($6.0) billion of this funding went towards the Industrial Demonstrations Program (IDP), which was sector and solution agnostic and accepted projects for both new facilities and retrofits, making the money extremely flexible. Much smaller funding amounts were allocated to deployment and workforce programs like rebates for energy efficient technologies and systems, decarbonizing energy manufacturing and recycling facilities, and Industrial Training and Assessment Centers. No funding was allocated to R&D programs.

Hydrogen and Clean Fuels received $8 billion for the Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs program to support near-term demonstration and commercialization of hydrogen production, transportation, and usage. Hydrogen and clean fuels were also eligible for all of the loan programs, except for CIFIA. Investment across the full research-to-deployment (RDD&D) continuum was lacking. Dedicated funding for clean fuels besides hydrogen was also missing.

EVs and Transportation funding from BIL and IRA was largely focused on light-duty personal EVs. By contrast, investments in medium- and heavy-duty vehicles and urban transportation were limited.

EV manufacturing and supply chains received $8.3 billion in funding. The largest single allocations went to the Battery Materials Processing and Battery Manufacturing & Recycling Programs ($6 billion), strengthening domestic battery supply chains for EVs. Domestic Manufacturing Conversion grants ($5 billion), further supported downstream manufacturing of advanced EV technologies. Additional funding supported R&D for battery recycling and second-life applications. EV and battery manufacturing were also eligible for ATVM loans.

A notable new focus for DOE under BIL was the deployment of EV charging infrastructure. Charging infrastructure was eligible for $1.05 billion in DOE funding through the Renew America’s Schools program and the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant Program. DOE played a key role in the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation’s implementation of the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Formula Program, funded by DOT ($5 billion), and other charging programs. This marks a shift from DOE’s previous focus on developing vehicle technologies and fuels to a broader focus on all of the technology and infrastructure needs for widespread EV adoption.

Building Decarbonization and Efficiency received the most non-loan funding from BIL and IRA at $15.2 billion. The largest share of this funding, $12 billion, went towards deployment and affordability programs such as the Home Energy Efficiency Rebate Program, High-Efficiency Electric Home Rebate Program, and the Weatherization Assistance Program – all of which aim to reduce energy costs for low-income households by increasing the energy efficiency of their homes. Additional funding supported workforce training and the improvement of building codes. Little to no funding went to R&D and demonstration programs, signaling the relative maturity of building decarbonization and efficiency technologies compared to other sectors. District heating and cooling facilities are eligible for TEFP loans.

Carbon Management received a total of $11.6 billion. The majority of the funding went towards demonstration and deployment activities, of which $2.1 billion went towards CIFIA to support the deployment of transportation infrastructure, $2.5 billion went towards carbon storage validation and testing, $3.0 billion went towards carbon capture pilots and demonstrations, and $3.5 billion went towards the development of Regional Direct Air Capture (DAC) Hubs. Carbon management was also eligible for loans from the Title 17 programs.

Loans

DOE’s loan programs operate differently from the way authorizations and appropriations work for traditional assistance programs, which is why they are not included in the chart above. These programs receive both a certain amount of loan authority, which set limits on the size of their portfolios, and appropriations for program administration and credit subsidies, which allows the office to provide low-cost financing. The IRA appropriated $13.8 billion total for these four programs and provided an additional $310 billion in loan authority for Title 1703, Title 1706, and TFP. CIFIA was established in the IRA without a cap on its loan authority. The IRA also repealed the cap on ATVM’s loan authority, which remains uncapped.2

During the four years of the Biden administration, the Loan Programs Office (LPO), now renamed the Office of Energy Dominance Financing (EDF), issued a total of 24 loans and 28 conditional commitments, worth over $100 billion in total. Energy storage, battery manufacturing, clean power, and the grid received the greatest number of loans and conditional commitments, while nuclear energy, carbon management, and non-battery or EV manufacturing received the least. No loans were issued for CIFIA, which is why that program is not shown in the following figures.

Program Design & Implementation

Flexible Contracting Mechanisms: Grants vs. Other Transactions

The majority of BIL and IRA funding (excluding loans) was implemented in the form of grants and cooperative agreements governed by 2CFR 200 and 2CFR 910. Even for programs for which the legislation did not specify the exact type of assistance mechanism that DOE should use (i.e., unspecified or “financial assistance”), the agency largely defaulted to those grants and cooperative agreements. One argument for this approach was that program officers and contracting officers are trained and experienced in using these mechanisms, which may have helped programs deploy faster.

However, these grants were originally designed for R&D programs and faced some drawbacks when used for demonstration and deployment programs. 2CFR 200 and 2CFR 910 are almost 200 pages long, requiring extensive compliance that smaller organizations and organizations new to federal applications may not be equipped to navigate. Additionally, some terms and conditions required by those rules (e.g. for intellectual property, real property, and program income) were not compatible with private sector needs for demonstration and commercial-scale projects. Most consequentially, they require a termination for convenience clause, which allows the government to cancel an award without providing a reason. The Trump administration is now using that clause to terminate awards.

Alternatively, DOE could have more frequently used its Other Transaction Authority (OTA) to enter into contracts without 2CFR regulations, allowing the agency to negotiate contracts more like the private sector would, developing terms and conditions as they make sense for the purpose of the specific purpose. This can enable DOE to design and implement more creative arrangements, such as for demand-pull or market-shaping mechanisms. DOE could have also leveraged OTs to make process improvements, rethink the traditional solicitation and evaluation process, and potentially accelerate implementation.3

DOE 3.0 missed a major opportunity to leverage these benefits of OTs. The few exceptions were the Hydrogen Demand Initiative (H2DI), the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program, and Partnership Intermediary Agreements. Towards the end of the Biden administration, DOE discussed transitioning some of OCED’s awards to OT agreements, but did not get a chance to follow through before the presidential transition.4

DOE 4.0 should pick up where DOE 3.0 and deploy OTs more broadly among demonstration and deployment programs to overcome the challenges of traditional financial assistance regulations and processes. Congress should ensure that future authorizing legislation is designed to enable this flexibility–for example, by not specifying the type of assistance that DOE should use to implement new programs.

Flexible Funding

BIL and IRA authorized and appropriated funding for a wide range of programs, many with very specific goals and eligible uses. That approach allows Congress to provide detailed direction to DOE on legislators’ priorities. However, DOE should also be able to respond dynamically to industries and markets as they develop. For example, when BIL and IRA were being developed, next-generation geothermal technologies were still quite nascent and received very little funding from these bills. Within two years though, the technology rapidly advanced, thanks to the success of the first few demonstration projects, and now shows enormous potential for meeting clean, firm energy demand, but DOE has limited funding available to support the industry.

In future legislation, Congress should consider establishing a few flexible funding programs that would give DOE a greater range of options to support the development of energy technologies and infrastructure as the agency’s experts know best. This could look like a pooled pot of funding with broad authority for DOE to use across technologies and/or activities, such as a single fund for demonstration and deployment activities broadly, or a single fund for grid infrastructure needs. If Congress is wary about this, legislators could start with creating flexible funding programs designed to fit within the scope of a single DOE office, before testing programs that cross multiple offices, which may come with intra-agency coordination challenges.

Program Design: Regional Hubs

The Hydrogen Hubs and Regional Direct Air Capture (DAC) Hubs were a new type of program established by BIL, designed to fund clusters of projects located in different regions rather than individual, unrelated projects. BIL invested $7 billion and $3.5 billion in these programs, respectively, and they made some of the largest awards by dollar amount – on the order of $1 billion per award – out of all of the BIL and IRA programs.

The hub approach aimed to foster an industrial ecosystem, including not only multiple projects aiming to deploy the technology, but also future suppliers, offtakers, labor organizations, academic partners, and state, local, and Tribal governments. Concentrated regional investment and greater coordination would not only accelerate commercialization of hydrogen and DAC technologies but also help distribute the benefits of new clean energy industries across the nation.

Due to the ambitious size and complexity of their goals, the Hydrogen Hubs and DAC Hubs required, and still require, a long timeline to develop. The structure and oversight DOE applied to the hub development process also extended timelines further. When the Trump administration began re-evaluating Biden-era programs and Congress started looking for funds to rescind, these two programs became appealing targets because of the large amount of funding they held and the lack of on-the-ground deployment progress – even though that was to be expected based on the program timeline.5

Project cancellations and funding rescissions are a massive waste of both federal and private sector resources. In the future, before creating any other large-scale programs modeled on the Hydrogen Hubs and DAC Hubs, policymakers should first determine whether there is long-term bipartisan commitment to the program’s goals to avoid the possibility that a change of administration will jeopardize the program. If that commitment isn’t guaranteed, this model may simply be too risky to use; other types of assistance may be easier to implement or more resilient to changes in administration.

An alternate regional hub model that Congress and DOE could consider is the CHIPS and Science Act’s Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs and NSF Engines. These programs had a much lower level of ambition, providing awards – on the order of tens of millions instead of one billion – to seed early-stage innovation, build a research ecosystem, and support workforce development, rather than deploying specific technologies.

Program Design: Demand-Pull

Demand-pull mechanisms have emerged in conversations between FAS and former DOE staff as a very underutilized but promising tool for enabling the scaling and deployment of clean energy technologies and large-scale infrastructure projects. Confidence in long-term offtake is a requirement for private lenders to provide financing at a viable rate for projects. DOE can help provide that certainty through a wide range of tools, including purchase commitments and capacity contracts, contracts-for-difference, and other financial arrangements.

By unlocking private sector investment, demand-pull mechanisms can reduce or eliminate the need for DOE to provide additional financing for project construction. However, public sector funding is still useful for pre-construction stages of project development, such as planning, siting, and permitting, which can be hard to get private sector financing for when other risks to a long-term revenue model have not been addressed yet.

There are three primary use cases for demand-pull mechanisms: building shared infrastructure, demonstrating innovative technologies, and expanding industrial capacity.

Shared infrastructure projects require a large number of customers and can sometimes struggle with securing them: customers are afraid to commit without the developer demonstrating that they’ve secured other customers first. DOE can help address this challenge by serving as an anchor customer for these projects and help attract additional customers. This also makes it easier to finance the project.

A successful example of this from BIL is the Transmission Facilitation Program, which authorized DOE to purchase up to 50% of the planned capacity of large-scale transmission lines for up to 40 years. Once the transmission line is built, DOE can then sell capacity contracts to actual customers who need to use the transmission line and recoup the agency’s investment. This approach could be used for other types of shared infrastructure, such as hydrogen or carbon dioxide transportation, or even large clean, firm power plants (e.g., nuclear) for their generation capacity.

First-of-a-kind projects often struggle to secure offtakers due to the unproven nature of their technology and the lack of a pre-existing market. For example, H2DI was designed to complement the Hydrogen Hubs program by directly supporting demand for select hydrogen producers and also helping establish a transparent strike price for the nascent market that would benefit all hydrogen producers. Other demonstration programs (e.g. IDP) would have also benefited from DOE support for demand and market formation.

Lastly, the development of new industrial capacity for producing energy technologies and their inputs can also face demand challenges because while there may be a pre-existing global market, the domestic market may be small or nonexistent, and existing offtakers may not be willing to reroute their supply chains without market or policy pressure to do so. This was most obvious with the critical minerals and battery supply chain projects that DOE tried to support.

One successful model from the IRA was the HALEU availability program. DOE set up indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contracts with companies developing HALEU production capacity and set aside $1 billion to procure HALEU from the five fastest movers. The purchase commitment created demand certainty, while the competitive model incentivized faster project development and ensured that the DOE’s funding would only go towards the most viable projects. More programs like this would be transformative for domestic supply chain development.

In designing demand-side support programs for these latter two categories, DOE must tailor the programs to the unique challenges of different technologies or commodities, and whether or not there are additional goals of domestic market formation and/or market stabilization. For example, auctions are a great tool for price discovery, while contracts-for-difference can help projects hedge against price volatility and overcome domestic price premiums.

There are also double-sided market maker programs where DOE serves as an intermediary between producers and buyers, entering into long-term offtake commitments with project developers up front to provide demand certainty, and then reselling the product to buyers on a shorter-term basis when the project comes online This helps make supply chain connections and address mismatches between project developer vs. buyer timelines. For example, for low-carbon cement and concrete, buyers typically procure building materials on a short-term basis as needed for each project, but developers of first-of-a-kind production facilities require long-term offtake commitments in order to secure project financing.

Authorizing language and/or appropriations can be a barrier to DOE using demand-pull mechanisms. To address this issue, Congress should factor the following considerations into the design of legislation:

- Flexible Authorities. Due to the variety of demand-pull mechanisms and the need to tailor them to the unique market challenges of different technologies or commodities, they are best implemented using OT agreements. Statutory language that prescribes the exact type(s) of assistance (e.g., grants) for a program can prevent DOE from using demand-pull. Instead, Congress should provide clear goals for a program to achieve and leave DOE with the flexibility to determine the best type of assistance mechanism.

- Budget Scoring and Timelines. Demand-pull mechanisms often involve multi-year advance commitments of funding, but the exact amount and timing of transactions may be uncertain, since it is conditional upon project performance and overall market conditions (e.g. contracts-for-difference payments are based on the market price at the time of the transaction). This results in budget scoring issues. Legally binding commitments of money can typically only be made if the agency has enough funding to obligate the full amount of the contract when it is signed, even if that funding probably won’t be paid out until much later.6 This results in the need for a significant amount of upfront funding, which can be difficult to obtain from Congress, and long timelines before the outcome of that funding is fully realized, which can make it difficult to manage congressional expectations. These long timelines also mean that no-year funding is ideal for DOE to be able to run demand-pull programs without the funding expiring.7

- Revenue Management. Some demand-pull mechanisms are designed with the potential for revenue generation, so legislation should ideally be designed to include the authorization of a revolving fund to allow revenue to be reused for program costs. Alternatively, DOE may contract with an external entity to manage the program funds, as it did with H2DI, so that the revenue can stay with the partner entity and be reused.

Program Design: Prizes

Unlike most financial assistance, which operates on a cost-reimbursement basis and requires cost-share, prizes reward performance and are awarded after activities are completed and criteria have been met. This means there are no strings attached to the funding and no IP requirements, making these programs easier for applicants to work with.8 Prizes are also of a fixed amount, which incentivizes innovators to find least-cost solutions in order to maximize revenue from the award. On the flip side, innovators are responsible for any cost overruns, and DOE is not required to shoulder that risk.

In the past DOE has used prizes wrongly to try and reach potential applicants that struggle with the application process for traditional assistance. It’s important to keep in mind the best use cases for prize programs. For example, prize programs rely on clear milestones, but are agnostic on the approach, making them great for interdisciplinary innovation. They can be beneficial for incentivizing new innovators to get involved with problem areas that don’t have many pre-existing solvers. They are also well-suited for small dollar amount awards that otherwise may not be worth the administrative overhead, since the overhead costs for prize programs are lower than traditional assistance programs once they have been designed.

Moving forward, DOE should keep in mind best practices for designing equitable prize programs. Prize programs should ideally be designed as stage-gated competitions with incremental prize payments for each phase, rather than one big payment at the end, so that innovators with fewer financial resources can participate. For example, the first stage could be the submission of a whitepaper with a proposed plan for developing and testing the technology, then the second stage could be lab work, and so on. Participants would be whittled down between each stage to hone in on the most competitive projects.

Program Design: Loans

DOE 4.0’s loan programs could be improved by setting clearer expectations on risk, clearer guidance on State Energy Financing Institution (SEFI) projects, and a strategy for using additional tools such as equity.

Risk Tolerance. Discrepancies between statutory language and congressional oversight for DOE’s loan programs have historically made it difficult for the agency to determine the right balance of risk. For example, Title 1703 is designed by legislation to fund innovative, higher-risk, hard infrastructure projects that the private sector is typically reluctant to fund. A high-risk, high-reward program should, by nature, be allowed to have some failed projects and still be considered a success. However, Congress has historically been extremely critical of any defaulted loans, making DOE hesitant to use Title 1703 and ATVM to its full potential.

DOE 3.0 made some attempts to improve communications on its approach to risk management, but the agency could do more to communicate the success of its loan programs. Congressional authorizers should help the agency by building risk into the statute of DOE’s loan programs and budgets and better managing the expectations of oversight members.

State Energy Financing Institution (SEFI) Projects. Another area of reform that DOE 4.0 should tackle is the SEFI-supported projects under Title 17, authorized by BIL, which allows DOE to finance any energy project that also receives “meaningful financial support” from a SEFI, such as state energy offices or green banks. However, ambiguity in the statute behind this new carveout caused confusion among states on how exactly to partner with DOE’s loan program. What is considered meaningful financial support? What qualifies as a SEFI? To clarify these questions from states, either DOE 4.0 should create model SEFI guidance or Congress should amend the statute with clear definitions.

Equity and Other Financing Tools. The Trump administration’s restructuring of the Lithium Americas Thacker Pass loan to include an equity warrant, which gives DOE the right to acquire equity of the company at a set price in the future, has raised questions as to what DOE’s role should be if it were to become an equity owner in a company and what guardrails and visibility is needed in such a scenario.9 Policymakers may also want to consider the risks and benefits of expanding DOE’s loan program authorities to include direct equity investments and other financing tools that agencies like the International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) have access to.10

Program Design: Technical Assistance

DOE 4.0 should expand its technical assistance offerings in three primary ways: technical advising and verification, navigating federal funding, and talent and workforce needs.

Technical Advising and Verification. DOE’s in-house scientific and engineering expertise is a major draw for funding applicants. For example, according to FAS conversations with former agency staff, the project developers behind Vogtle Units 3 and 4, which received a loan guarantee from DOE, would seek advice from LPO engineers when they had engineering questions. Private investors, who may lack the expertise needed for technical due diligence, often use DOE awards as a proxy for assessing project risk. As a result, some project developers will apply for DOE funding to prove their credibility to private financiers and negotiate lower financing rates.

In the face of potential budget cuts, DOE 4.0 could leverage this strength by offering project certifications that would entail the same technical support and verification as a demonstration award or loan, without the funding support. This would provide a similar market signal to private investors, without costing DOE as much – just staff time. And since DOE is not taking on any project risk, the application and negotiation process could also be simplified and streamlined to align better with private-sector timelines.

Navigating Federal Funding. DOE should dedicate increased resources to conducting outreach to underserved communities, small businesses, innovators, and new applicants about funding opportunities and shepherding them through the application process. For example, despite awareness of available funding opportunities, some Native American tribal organizations in Alaska were unable to pursue them due to a lack of bandwidth or expertise to participate in resource-intensive (and often times confusing) application processes, and the awards sizes were too small to make them worth the costs of external private consultants to support. Community Navigator Programs and other forms of technical assistance could help communities overcome these barriers to accessing federal support. PIAs can also help with reaching small businesses and new applicants to apply for programs.

Talent and Workforce Needs. DOE has had success with placing talent at state energy offices and other critical energy organizations like public utility commissions through the Energy Innovator Fellowship to embed expertise in under-resourced offices. DOE should consider expanding this program or establishing new programs to place experts at other institutions, such as grid operators, investor owned utilities, and local governments, to advise and support them in adopting new energy technologies and accelerating infrastructure deployment.

Program Design: Community Benefit Plans

For all of its demonstration and deployment programs, DOE 3.0 introduced a new requirement that awardees create community benefit plans (CBPs) to ensure that communities would share in the benefits of local clean energy projects. CBPs have been both lauded and criticized by community and labor organizations: they praised their intent, but expressed frustration over their limited influence on companies’ plans and that allowable cost limits constrained what could be included in awards. Where CBPs were most effective, they encouraged developers to consider local communities and jobs, though this often required significant internal coordination to use DOE’s funding contracts as leverage. At the same time, CBPs were seen as an additional administrative burden on program implementation, contributing to delays. Under the Trump administration, CBPs will no longer be enforced and are no longer required for future funding opportunities.

DOE 4.0 presents an opportunity to restore and improve CBPs as a mechanism for both distributing the benefits of federally-funded projects and improving project quality. To maximize impact, DOE 4.0 should focus on a smaller set of high-priority outcomes with clear, measurable success metrics. DOE 3.0’s broad mandate, which spanned jobs, justice, climate, and deployment across multiple programs, sometimes diluted effectiveness and created confusion for staff managing both program design and operations. In DOE 4.0, these outcomes should be closely linked to actual project success, whether through facilitating social license to ease permitting, or supporting workforce development to train and retain workers, as developers themselves emphasized when aligning with program goals. Providing actionable guidance, including templates and real-world examples of successful community benefits plans, can further improve project outcomes. The advocacy community can help lay the groundwork for DOE 4.0 by documenting successful case studies and model agreement language. Congress could help embed key priorities in statute, providing clear, practical guidance that reflects DOE’s administrative capacity and enhances the likelihood of successful implementation.

Additionally, it is critical that future CBP mechanisms account for community preferences, including local prohibitions on certain technologies and other expressions of community priorities. By proactively respecting local concerns, DOE can foster trust and strengthen the long-term impact of projects. DOE 4.0 will also need to navigate tensions around labor preferences. While the department cannot explicitly require union labor, questions about labor practices may signal preferences that vary across states, including right-to-work contexts. This underscores the importance of sensitivity to local norms and expectations.

Where resources allow, DOE 4.0 should hire and dedicate staff with expertise in labor engagement and community partnerships to review applications and provide technical assistance, supporting applicants in navigating the CBP process and designing high-quality, community-centered projects. Technical assistance needs to be done carefully though to avoid perceptions of bias and influencing the award selection process.

Lastly, clear and consistent guidance across DOE offices is essential. For example, applicants have reported a lack of clarity about what activities qualify as “allowable costs” in CBPs, and different offices have applied inconsistent standards. Establishing a unified, expansive approach to allowable costs—including activities that indirectly support clean energy workforce development, such as community child care programs—can unlock transformative opportunities for local communities. This standardization should be done for other aspects as well. In general, official guidance needs to find a better middle ground between the overly technical, lengthy documents and vague webinars produced by DOE 3.0, so that ideally applicants can understand requirements without staff intervention.

Conclusion

Good program design is fundamental to effectively engaging with researchers, industry, state and local governments, and communities, in order to realize the full potential of DOE funding. Though much of the real-world impact of BIL and IRA is still yet to come, DOE can already begin learning from the challenges and successes of program design and implementation under the Biden administration. The recommendations in this report are just as applicable to the remaining funding from BIL and IRA that DOE has yet to implement, as they are to future programs. Moving forward, Congress has the opportunity to reconsider the way that programs are designed in future legislation, especially those targeting demonstration and deployment activities, and make sure that DOE has clear direction and the right authorities and flexibility to maximize the impact of federal funding.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Arjun Krishnaswami for coining the idea of DOE 4.0 and his insightful feedback throughout the development and execution of this project. The authors would also like to thank Kelly Fleming for her leadership of the clean energy team while she was at FAS. Additional gratitude goes to Claire Cody at Clean Tomorrow, Gene Rodrigues, Keith Boyea, Kyle Winslow, Raven Graf and all the other individuals and organizations who helped inform this report through participating in workshops and interviews and reviewing an earlier draft.

Appendix A. Acronyms

Appendix B. BIL and IRA Funding Distribution Methodology

The funding distribution heat map at the beginning of the report includes all of the BIL and IRA programs with funding authorized and/or appropriated directly to DOE, excluding loan programs. The following were not included in this table:

- Loan programs, which are funded differently than traditional programs;

- Tax credits that DOE helped design (e.g., 45X), which are also funded through a different mechanism; and

- Programs implemented by DOE, but funded by other agencies’ appropriations, such as the Methane Emissions Reduction Program funded by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Programs were tagged according to their sector or technology area, their activity area, and type of assistance based on key words in their statutory language. Programs could be tagged with multiple sectors/technologies, activity areas, and/or types of assistance.

To determine the amount of funding for each sector/technology and activity area combination, all of the programs with the corresponding tags were included in the sum. Because of this duplicative counting, the sum of the dollar amounts in the table exceeds the total amount of funding for all of these programs. Sector/technology totals were calculated without this duplication, which is why those amounts are less than what one would obtain by summing all of the activity area amounts for a sector/technology.

Activity area categories:

- “R&D” includes funding for programs covering research, development, and/or pre-commercial pilots.

- “Demonstration” includes funding for demonstration and commercial pilot programs using innovative technologies.

- “Deployment” includes funding for project planning, financing, and offtake; siting and permitting; and the development of standards or codes.

- “Workforce” includes educational outreach, training programs, apprenticeships, and other workforce development programs.

- “Energy Access and Affordability” refers to funding to lower the cost of energy for low-income households and to support the development or improvement of energy infrastructure for rural and remote areas and tribal nations. Some of these programs involve multiple sectors/technologies (see below).

- “National Labs Infrastructure” refers to programs funding construction and facility upgrades at national labs.

Sector/technology categories:

- “Grid infrastructure” refers to programs focused on any part of the transmission network between power generation facilities and consumer households or facilities, plus the planning, operations, and management of grid and the interconnection of new generation or loads to the grid. These were primarily programs implemented by the former Grid Deployment Office or the Office of Electricity.

- “Power: Technology Neutral” refers to programs supporting power generation or storage that any zero-emission generation technology was eligible for.

- “Power: Solar Energy”, “Power: Wind Energy”, “Power Hydro and Marine Energy”, “Power: Geothermal Energy”, “Power: Nuclear Energy”, and “Power: Energy Storage Systems” refers to programs focused on the underlying technologies and the demonstration and deployment of power generation and storage facilities using these technologies. Demonstration and deployment programs for the manufacturing of these energy technologies and input materials and components (e.g. battery manufacturing or HALEU fuel) were not included in these categories, but rather under the “Manufacturing and Supply Chains” category.

- “EV Charging Infrastructure” refers to programs supporting charging infrastructure for EVs of any weight class.

- “Critical Minerals” refers to programs supporting the mining, processing, recycling, and recovery from non-traditional sources of materials on either DOE’s Critical Materials List or the U.S. Geological Service’s Critical Minerals list.

- “Manufacturing and Supply Chains” refers to programs supporting the manufacturing of energy technologies and their input components and materials, as well as advanced manufacturing technologies in general. This category can overlap with both “Critical Minerals” (e.g. the Battery Materials Processing Program) and “Industrial Decarbonization/Efficiency” (e.g. the Advanced Energy Manufacturing & Recycling Grants Program)

- “Industrial Decarbonization & Efficiency” refers to programs supporting the reduction or elimination of carbon emissions from manufacturing industries.

- “Building Decarbonization & Efficiency” refers to programs supporting the reduction or elimination of carbon emissions from building heating, cooling, and electricity consumption. The manufacturing of building technologies was not included in this category, but rather the “Manufacturing and Supply Chains” category.

- “Hydrogen and Clean Fuels” had only one program, the Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs.

- “Carbon Management” refers to programs supporting the capture (point source and direct air), transportation, utilization, and storage of carbon dioxide.

- “Cross-cutting” refers to programs that are not specific to any one sector or technology.

One Year into the Trump Administration: DOE’s FY26 Budget Cuts and the Path Forward

This piece is the last in a series analyzing the current state of play at DOE, one year into the second Trump administration. The first piece covers staff loss and reorganization; the second piece looks at the status of BIL and IRA funding and the impact of award cancellations.

Overview of DOE Funding for FY26

On January 15th, Congress passed the FY26 E&W Appropriations as part of a second minibus along with the Commerce, Justice, Science and the Interior and Environment Appropriations (bill text and joint explanatory statement). Assuming the President signs this package into law, it will dictate DOE’s funding through the rest of FY26, which ends in September, and potentially into FY27 if any continuing resolutions are passed in the next appropriations cycle.

Though the administration originally requested drastic cuts to all of DOE’s offices involved in clean energy RDD&D, the FY26 E&W Bill takes a much more restrained approach to budget cuts and reprograms some BIL funds to bolster EERE, NE, FE, and SC budgets. Notably, Congress increased appropriations levels for SC, NE, and SCEP, despite DOE’s request to zero out the budget for SCEP. Overall, compared to FY25, the FY26 Appropriations enact a 1.4% cut to the agency’s budget – a modest amount compared to DOE’s original request for a steep 7.0% cut.

The passage of the FY26 E&W Appropriations is a major accomplishment for Congress, especially given the short timeline over which the conferenced bill came together and the rejection of the deep cuts advocated for by this administration. Nevertheless, even minor cuts threaten to decelerate progress on energy innovation, manufacturing, and infrastructure necessary for the United States to meet energy demand growth, reliability, affordability, and security challenges – precisely when we need it the most. As we begin the FY27 appropriations process this year, it’s all the more important that Congress not only maintain stable funding levels for DOE, but also begin to rebuild momentum for energy innovation and technological progress.

Reallocation of Unobligated BIL Funds

Section 311 of the FY26 E&W bill repurposes $5.16 billion in unobligated funding from BIL for the following programs:

- $1.28 billion from the Civil Nuclear Credit Program;

- $1.5 billion from the Carbon Dioxide Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation program (CIFIA);

- $1.04 billion from the Regional Direct Air Capture (DAC) Hubs;

- $950 million from the Carbon Capture Large-Scale Pilot Projects and the Carbon Capture Demonstration Projects; and

- $394 million from BIL programs funded through EERE’s account, including those implemented by MESC and SCEP.

The Civil Nuclear Credit Program is a new addition that was not present in either the House or the Senate’s original versions of the E&W bill. The other programs targeted for reallocation and the corresponding amounts were all proposed in either the House and/or the Senate’s original versions of the E&W bill. Notably, funding for the Hydrogen Hubs was spared after conferencing, despite previous inclusion in both chambers’ E&W bills.

The reprogrammed funds are to be used as follows:

- $3.1 billion for NE to be used for the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program;

- $375 million for the Grid Deployment Office “to enhance the domestic supply chain for the manufacture of distribution and power transformers, components, and materials, and electric grid components, including financial assistance, technical assistance, and competitive awards for procurement and acquisition”;

- $1.15 billion for EERE activities;

- $100 million for NE activities;

- $140 million for FE activities;

- $150 million for SC activities; and

- $150 million for Title 17.

These moves reflect Congress’ emphasis on advanced nuclear demonstration projects, growing concern over grid supply chain bottlenecks, and continued commitment to funding EERE activities, as well as skepticism about the goals and execution of carbon management demonstration programs.

Zooming in: EERE Suboffices

DOE’s FY26 budget request proposed a major contraction of the EERE portfolio, explicitly requesting zero funding for four sub-accounts Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies, Solar Energy Technologies, Wind Energy Technologies, and Renewable Energy Grid Integration. For the first three, the Department argued that these technologies had reached sufficient market maturity to rely primarily on private capital—which is definitely not the case for hydrogen and fuel cell technologies, and inconsistent with DOE’s continued funding for more mature technologies such as nuclear, coal, and gas. For Renewable Energy Grid Integration, DOE argued that the work would be absorbed into other programs. DOE also sought to near-eliminate the budget for the Building Technologies Office (BTO) and the Vehicle Technologies Office (VTO) by requesting only $20 million and $25 million, respectively, signaling a broader retreat from technologies that would support electrification, energy efficiency, and affordability.

Congress largely rejected wholesale eliminations in the FY26 bill they passed. Compared to FY24 and FY25 enacted levels, the deepest cuts for FY26 were for Solar Energy Technologies (31%) and Wind Energy Technologies (27%). Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies was also targeted for deep cuts in the original House and Senate appropriations bills, but ended up with only a 6% budget cut after conferencing and passage, putting the office in a better position than many of the other EERE suboffices that lost more than 10% of their annual budget. The only two offices that received budget increases were Geothermal Technologies (27%) and Water Power Technologies (10%), reflecting Congress’ prioritization of clean firm energy technologies.

EERE suboffice funding amounts are dictated in the Joint Explanatory Statement, a report that accompanies annual appropriations bills and provides detailed guidance on how funds are to be allocated within the topline account numbers set by the appropriations bill. Historically, agencies have always adhered to report language; even under full-year continuing resolutions, agencies would still follow the funding guidance set in the prior fiscal year’s report language.

The second Trump administration broke this precedent: DOE’s FY25 spend plan – released more than three-quarters of the way through the fiscal year – shifted more than $1 billion away from core clean energy programs under EERE, disregarding Congressional direction in the FY24 appropriations report.1 DOE moved funding away from Vehicle, Hydrogen and Fuel Cell, Solar, Wind, and Building Technologies, towards Renewable Energy Grid Integration and Water Power, Geothermal, Industrial, and Advanced Materials and Manufacturing Technologies. These actions have raised concerns about whether the administration will attempt to do the same in FY26.

Zooming in: National Labs

The Joint Explanatory Statement does not provide guidance on how DOE allocates funding to national labs, though there tends to be a trickle down effect depending on which offices labs are reliant on funding from. DOE proposed drastic cuts to the FY26 budgets of many national labs, particularly those that get a significant amount of funding from EERE. Under the proposed budget cuts, the national labs would reportedly plan to lay off 3,000 or more scientists and other staff.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) – recently renamed the National Lab of the Rockies, or NLR for short – faces the largest proposed budget cut of 72% because it’s affiliated with EERE and gets the majority of its funding from that office. Such deep cuts would require NLR to lay off up to a third of its staff and shut down many of its facilities and ongoing activities.

With the passage of FY26 appropriations, hopefully, DOE will reconsider funding for national labs and adjust budgets upwards to reflect the much milder cuts that Congress passed.

Long-Term Impacts

Sustained budget cuts to DOE pose significant long-term risks to the nation’s scientific enterprise and ability to compete globally. Because DOE is the federal government’s primary engine for energy research and advanced technology commercialization, reductions in funding have both immediate operational consequences, as well as lasting structural ones.

Budget cuts translate directly into workforce attrition across DOE program offices, national laboratories, and partner institutions. When staffing levels fall, the federal government’s capacity to execute world-leading scientific research diminishes. Essential functions like managing user facilities, overseeing complex R&D portfolios, and ensuring the continuity of long-term research programs are all jeopardized, slowing the pace of innovation and limiting the nation’s ability to respond to emerging scientific and energy challenges.

Loss of program funding and workforce capacity raises a broader strategic concern: the U.S. may no longer retain the scientific and engineering talent necessary to develop next-generation energy technologies. DOE plays a critical role in cultivating and sustaining technical talent pipelines through early-career research programs, national lab fellowships, university partnerships, and long-term R&D initiatives that span decades. When the continuity of these programs is disrupted, students, postdocs, and mid-career researchers may exit the field entirely or shift their expertise abroad, diminishing the domestic talent base. These losses cannot be quickly reversed as rebuilding a skilled scientific workforce takes sustained investment, stability, and opportunity signals that cuts fundamentally undermine.

Attrition is not limited to DOE itself. The broader U.S. science and innovation workforce – spanning clean energy startups, universities, private-sector R&D, and communities that host national laboratories – absorbs the shock of federal retreat. Reduced research funding forces universities to shrink labs, scale back graduate cohorts, and limit collaborations with DOE facilities. National laboratory communities, often in rural or specialized high-tech regions, face economic consequences when jobs disappear or major facilities reduce their operating capacity. The ripple effects of lost researchers, technical staff, and support personnel weaken the entire innovation ecosystem that underpins clean energy deployment.

Quantifying these long-term losses is essential. Each scientist or engineer who leaves the field takes with them years of specialized training, intellectual and institutional capital, and future contributions to technological advancement. The economic value of these foregone innovations – from delayed commercialization timelines to missed breakthrough discoveries – can be substantial. A shrinking innovation pipeline also slows private-sector investment domestically and increases dependence on imported technologies at a moment when global competition in clean energy, advanced computing, and critical minerals is accelerating.

In the long run, sustained budget cuts compromise the United States’ ability to remain a global leader in science and innovation. They jeopardize advancements in energy innovation, undermine national competitiveness, and reduce the nation’s capacity to deliver affordable, secure, and clean energy solutions. Protecting DOE’s workforce and research infrastructure is therefore not only a matter of annual appropriations, but also a long-term investment in America’s economic strength and technological leadership.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

As we begin the second year of the second Trump administration, DOE sits upon the precipice of transformation. Over the past year, the rapid pace and unprecedented scale of changes to the agency’s staff, organizational structure, programs and awards, and budget have generated waves of uncertainty and volatility that has rippled out across the energy sector, destabilizing commercial projects worth billions of dollars, as well as DOE’s relationship with the private sector, state and local governments, its own career staff.

After all these changes, whether DOE transforms for better or worse will depend on the decisions this administration makes over the next three years. Realizing this administration’s priorities of energy dominance and abundance will require DOE to rebuild its technical and organizational capacity to design and implement programs, oversee loans and awards, and engage in public-private and intergovernmental partnerships.

This should start with carefully managing the agency’s reorganization and providing clearer, more detailed explanations to the public on the mandate and internal structure of new offices and where existing programs and activity areas have been moved, and guidance to employees about how the reorganization will impact their roles and the programs on which they work. DOE leadership should then evaluate the functions and capacities missing under the new organizational structure and rehire for those roles, ideally with the reinstatement of remote work flexibility.

As the agency rebuilds internal capacity, it should reorient efforts away from reacting to the previous administration and towards actions that will build the infrastructure necessary to modernize and expand the energy system, ensure reliability and affordability in the face of demand growth, secure energy supply chains, and maintain U.S. leadership in energy innovation. The wave of funding opportunity announcements for BIL critical minerals programs over the past few months was a good start, but that is not DOE’s only mandate. DOE must also restart activities across other technologies and sectors. Luckily, the agency still has $30 billion plus in funding from BIL and IRA that has yet to be awarded. In implementing the remaining funding, DOE can learn from the many lessons learned reports on the previous administration’s experience and adopt internal reforms. The agency should also make sure to adhere closely to the statutory intent behind this funding.

Lastly, stable year-to-year funding is essential for progress. As Congress begins the FY27 appropriations process this month, congress members should also turn their eyes towards rebuilding DOE’s programs and strengthening U.S. energy innovation and reindustrialization. Higher DOE funding levels will be necessary to put the United States back on a growth trajectory with respect to global energy leadership and competitiveness.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Megan Husted and Arjun Krishnaswami for their pivotal roles in shaping the vision for this project, planning and executing the convenings that informed this report, and providing insightful feedback throughout the entire process. The authors would also like to thank Kelly Fleming for her leadership of the project team while she was at FAS. Additional gratitude goes to Colin Cunliff, Keith Boyea, Kyle Winslow, and all the other individuals and organizations who helped inform this report through participating in workshops and interviews and reviewing an earlier draft.

One Year into the Trump Administration: DOE Awards Cancelled and Programs Stalled

This piece is the second in a series of analyzing the current state of play at DOE, one year into the second Trump administration. The previous piece on staff loss and reorganization can be read here.

Introduction

$25.8 billion in BIL appropriations, over a third of the total amount, have yet to be awarded, plus up to $4.3 billion in IRA funding left after OBBBA rescissions. Yet, for the entire first year of the Trump administration, DOE has focused primarily on undoing the work of the prior administration. Politically motivated award cancellations and the delayed distribution of obligated funds have broken the hard-earned trust of the private sector, state and local governments, and community organizations. DOE also carried out a significant internal reorganization that eliminated many of the commercialization and deployment focused offices and moved their programs into other offices, leaving their futures unclear.

The implementation of remaining BIL and IRA funding has been stalled across the board (except for critical minerals-related programs), and the administration has attempted to push the limits of legislative interpretation by redirecting funds for carbon capture and rural and remote energy improvements towards bringing inactive coal power plants back into service and/or extending the life of coal plants near retirement.

Overview of BIL and IRA Funding Status

BIL and IRA appropriated $71 billion and $35 billion, respectively, in funding for DOE clean energy programs. Once appropriated, DOE funding moves through three phases before being received by awardees:

- First, funding is awarded when DOE selects and announces the recipients for a program. Only 57% of BIL funding and 52% of IRA funding was awarded by the end of the previous administration.

- Then, funding is obligated when DOE legally commits the amount to the recipient through a contractual agreement. Obligations may be made in phases over time, especially if the award is of a large amount. Thirty-three percent (33%) of BIL funding has been obligated as of December 17th, 2025.

- Finally, funding is outlayed when the money is paid to the recipient(s) and officially transferred out of the federal government’s account. This can occur in installments over the course of the period of performance or through a single up-front payment. Four point eight percent (4.8%) of BIL funding has been outlayed as of December 17th, 2025.

Under the current administration, at least $11 billion, or 32%, of unobligated IRA funding was rescinded through the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), including the IRA credit subsidy appropriations for DOE’s loan programs, while $5.16 billion in BIL funding was transferred for other purposes by the Fiscal Year 2026 (FY26) Energy and Water Development (E&W) bill. Mass rescissions and reallocations of funding on this scale have been unheard of in the past.

A further $6.8 billion in BIL awards and $2.5 billion in IRA awards have been cancelled by the Department of Energy, primarily because they do not align with the new administration’s priorities. For BIL, the cancellations will impact 17% of awarded funding, 14% of obligated funding, and 3% of outlayed funding. For IRA, the cancellations will impact 7% of awarded funding. While DOE has in the past made one-off cancellations of individual awards for various reasons, mass cancellations on this scale are unprecedented and uniquely destructive to the relationship between DOE and the private sector, not to mention state and local governments and community organizations.

Award Cancellations

The first round of DOE award cancellations were announced in May 2025. The 24 cancelled awards, worth $3.7 billion, all came from OCED programs funded by BIL and IRA. The Industrial Demonstration Program (IDP) was the most severely impacted: 18 awards worth $3 billion, half of the total for the program, were cancelled. The other primary targets from this round of cancellations were the Carbon Capture Demonstrations Program and the Carbon Capture Large-Scale Pilots Program.

In early October 2025, DOE announced the cancellation of another 321 awards, worth over $8 billion. Of those awards, five from the IDP were duplicates from the May announcement. Once again, OCED’s programs were the most heavily impacted, with GDO a close second. The largest awards cancelled were the two west coast Hydrogen Hubs, each worth at least $1 billion and three of the Grid Resilience and Innovation Program (GRIP) awards located in California, Minnesota, and Oregon. Unlike the first round, other DOE awards not funded by BIL or IRA, roughly half of the list, were also cancelled. These awards primarily came from EERE and FE.

Only about 1.5% of the funding for these BIL and IRA awards was outlayed before they were cancelled. Non-BIL and IRA awards fared slightly better, with 38% of funding outlayed before they were cancelled. As a result of these cancellations, awardees may decide to abandon their projects entirely, which would end up wasting the hundreds of millions of dollars of federal funding that has already been spent.

The most direct impact of these cancellations is that communities that were promised jobs and other benefits will no longer get them. DOE is breaking its commitment to companies, workers, and other stakeholders, taking away the economic opportunity that new investments provided.

Moreover, federal funding would not be the only funding wasted: many of the canceled awards came with matching private-sector investments, totaling over $5.7 billion. In order for those private-sector investments to be put to use, project developers would need to seek additional funding to close the gap left by cancelled DOE awards. Even in the best case scenario, that process requires additional time and effort, resulting in delays and higher overall project costs.

The vast majority of these private-sector investments were intended to fund grid resilience and modernization projects. In the face of demand growth and grid reliability challenges, particularly from data centers, it seems counterintuitive to pull funding from these projects rather than doubling down on investments to improve and expand our grid infrastructure. These cancellations also run counter to the administration’s stated priority of “unleashing American energy” and will make it harder to provide the electricity needed to power the AI applications and innovations touted by this administration.

An additional list of projects has been circulating since the beginning of October, said to contain an additional $16 billion worth of projects being considered by DOE for cancellation. In late October 2025, Politico’s E&E News reported that DOE confirmed the cancellation of five of the projects on that list, totaling $718 million in funding, because they were not “economically viable.” All of the projects were funded by the Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains (MESC), which had been largely spared by the previous rounds of cancellations. Four of the cancelled awards were from the Battery Materials Processing and Battery Manufacturing Grant Programs, while the other award came from the Advanced Energy Manufacturing and Recycling Program. Since then, at least one of the projects, a lithium iron phosphate plant in Missouri, has folded, partially as a result of the DOE award cancellation.

In response to the cancellations, most companies are challenging the decision and seeking as much compensation as they can through the courts. The Supreme Court has ruled that challenges to the termination of specific awards must be filed through the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, which is understaffed and struggling with significant backlogs and delays. However, while large companies may be able to wait six months or up to one year for compensation, many small businesses and startups will go under if they cannot get recourse in time and run out of funding to keep paying their employees. Furthermore, the Federal Claims Court does not have the authority to reinstate terminated grants or contracts, which is what companies actually want.

A coalition of energy and environmental organizations filed a lawsuit over seven of the cancelled grants and won, arguing that DOE’s termination decisions were politically motivated and thus illegal, targeting awards primarily because they were located in blue states and/or funded clean energy technologies that the administration opposes. Those seven award cancellations have now been blocked by the judge’s decision, but the hundreds of other cancellations will continue unless additional lawsuits are brought forth.

All of this has resulted in a growing belief across the private sector (and also local governments and community organizations) that federal grants and contracts are no longer guaranteed to survive a change in administration. This destroys the trust built by 50 years of DOE upholding its contracts and commitments to the private sector. The Biden administration expanded this partnership with the private sector further, conducting significant outreach to improve interest from top tier companies in BIL and IRA programs. Now, all of that hard-won trust has been undone.

Members of Congress from both sides of the aisle have been watching these cancellations with concern. Section 301 of the FY26 E&W Bill introduces a new requirement that DOE must notify both the House and Senate Appropriations Committees at least three full business days before the agency issues a letter to terminate a grant, contract, other transaction agreement, or lab call award in excess of $1 million. The same requirement applies to any letter to terminate nonoperational funding for a national lab if the total amount is greater than $25 million.

Loan Cancellations, Delays, and New Terms

In addition to reevaluating and cancelling awards, DOE leadership also reevaluated the loans and conditional commitments made under the Biden administration, slowing down the evaluation process. So far, DOE has publicly terminated a $4.9 billion conditional commitment for the Grain Belt Express transmission. DOE was also reported to have plans to cancel six more conditional commitments and one active loan, totaling $8.5 billion. Former LPO staff have shared that these terminations were mutually agreed upon between the borrowers and DOE due to project economics. Some of this administration’s policies (e.g. the permitting ban on wind energy projects) may have indirectly contributed to worsening project economics.

Under the current administration, DOE has moved some projects that align with the White House’s priorities from conditional commitment to close – namely, AEP’s transmission upgrades and Wabash Valley Resources’ Coal-Powered Fertilizer Facility – and fast tracked a loan to restart the Three Mile Island Crane nuclear unit directly to close. However, for other projects less aligned with this administration’s priorities, DOE appears to be delaying the process to move conditional commitments forward and close out the loans. Former agency staff from the office claim that this is a way to softly cancel loans by putting timelines in limbo and waiting out the borrower, since conditional commitments have a maximum window of two years to either move to close or be rejected.

Changes to the term sheet when closing a loan is another way to force applicants out of the pipeline. Applicants typically receive an initial term sheet with the conditional commitment and then a final term sheet when closing the loan; applicants may not be able to accept or accommodate drastic changes between the two.

Notably, this administration restructured Lithium Americas’ Thacker Pass loan after it was closed, but before funds were disbursed. LPO has the right to restructure loan terms and get new conditions or concessions to protect taxpayer resources if there are concerns, but this is rarely done. LPO negotiated the right to 5% equity in Lithium Americas and 5% equity in the Thacker Pass joint venture in the form of a warrant. The agency statement points to LPO’s loan to Tesla in 2010 as precedent for using warrants. This move raises the question of whether LPO will be negotiating additional equity stakes in future loan agreements, given this administration’s many other equity deals.

Remaining BIL & IRA Funding and Awards

Loans are not the only thing DOE has slow-walked: recipients of active BIL and IRA awards have complained that DOE also delayed the distribution of obligated funds and was not paying invoices in a timely manner. This issue was especially acute in the beginning of 2025, when many grants and contracts were frozen and recipients were told to stop all work while new DOE leadership reviewed their funding. While some projects were allowed to move forward, some remained in limbo even towards the end of 2025, causing significant uncertainty and financial stress to awardees.

As for the remaining unobligated BIL and IRA funds, DOE has not issued any new funding opportunity announcements (FOAs), except for critical minerals-related programs, which have been favored by this administration, and a repurposing of BIL funding to support coal power plants:

- FE issued two FOAs for piloting byproduct critical minerals and materials recovery and mine technology proving grounds. MESC issued an FOA for a rare earth elements demonstration facility and a notice of intent to issue an FOA for round three of the Battery Materials Processing and Battery Manufacturing and Recycling Grant Program.

- FE issued an $525 million FOA “to expand and reinvigorate America’s coal industry.” Up to $175 million of funding would come from BIL funding for energy improvements in rural and remote areas. The remaining $350 million would come from BIL funding for the Carbon Capture Demonstration Projects Program and the Carbon Capture Large-Scale Pilot Projects, which both have unobligated balances as a result of prior award cancellations. Critics have questioned the legality of repurposing the carbon capture program funds in this way, since the FOA allows federal funding to be used for near-term reliability upgrades “without requiring immediate Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage (CCUS) installation,” even though the Congress specifically directed this funding to be used “to demonstrate the construction and operation of six facilities to capture carbon dioxide from coal electric generation facilities, coal electric generation facilities, natural gas electric generation facilities, and industrial facilities” and specifically two of each kind.1

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Megan Husted and Arjun Krishnaswami for their pivotal roles in shaping the vision for this project, planning and executing the convenings that informed this report, and providing insightful feedback throughout the entire process. The authors would also like to thank Kelly Fleming for her leadership of the project team while she was at FAS. Additional gratitude goes to Colin Cunliff, Keith Boyea, Kyle Winslow, and all the other individuals and organizations who helped inform this report through participating in workshops and interviews and reviewing an earlier draft.

Appendix: Methodology for BIL and IRA Funding Analysis

Data on total BIL and IRA appropriations and award amounts was obtained from the archived Invest.gov website created by the Biden administration’s White House. Loan amounts were not included, since loan authority is separate from appropriations. The archived Invest.gov website has not been updated since the end of the Biden administration. As of December 17th, 2025, the Trump administration has not made any new awards yet with BIL or IRA funding, so the data should be accurate up to that date.

Data on obligations and outlays came from the Department of Treasury’s USA Spending database. The total amount of obligations and outlays of BIL funding for DOE was determined by filtering for the Disaster Emergency Fund Codes for Infrastructure Spending associated with BIL and DOE as the Awarding Agency. All assistance awards and contracts that resulted from these filters were included in the total amounts.

The obligations and outlays for cancelled BIL and IRA awards in October were determined by searching the database for each unique award ID found in the list obtained by Latitude Media. The total amount of obligations and outlays for cancelled BIL and IRA awards in May was determined by searching the database for the awardees in the list reported by The New York Times and matching the award amounts, award location, and/or award description. All available data up until December 17th, 2025 was included. USA Spending tracks the amount of obligations and outlays for each award that came from BIL; this data was used to determine whether or not a cancelled award was funded by BIL. Whether or not a cancelled award was funded by the IRA was determined based on whether or not the award description explicitly mentions IRA and/or searching official DOE announcements and other public documents for the specific award using the recipient name and award description available on USA Spending. Any remaining awards were assumed to be funded by neither BIL nor IRA.

In this report, the total amount of unobligated funding rescinded by OBBBA is a minimum estimate. The minimum rescission amount for every loan program listed in Section 50402 of the OBBBA was determined by subtracting the total funding obligated from the loan program account between FY23 and FY25 (found on USA Spending) from the total appropriations for the program from the IRA (found in the bill text). The minimum rescission amount for every other program listed in Section 50402 of the OBBBA was determined by subtracting the total funding awarded for the program from the total appropriations for the program (both obtained from Invest.gov).

What’s New for Nukes in the New NDAA?

At the time of publication, the NDAA had passed both chambers of Congress but had not yet been signed by the president. The Act, S. 1071, was signed into law on December 18.

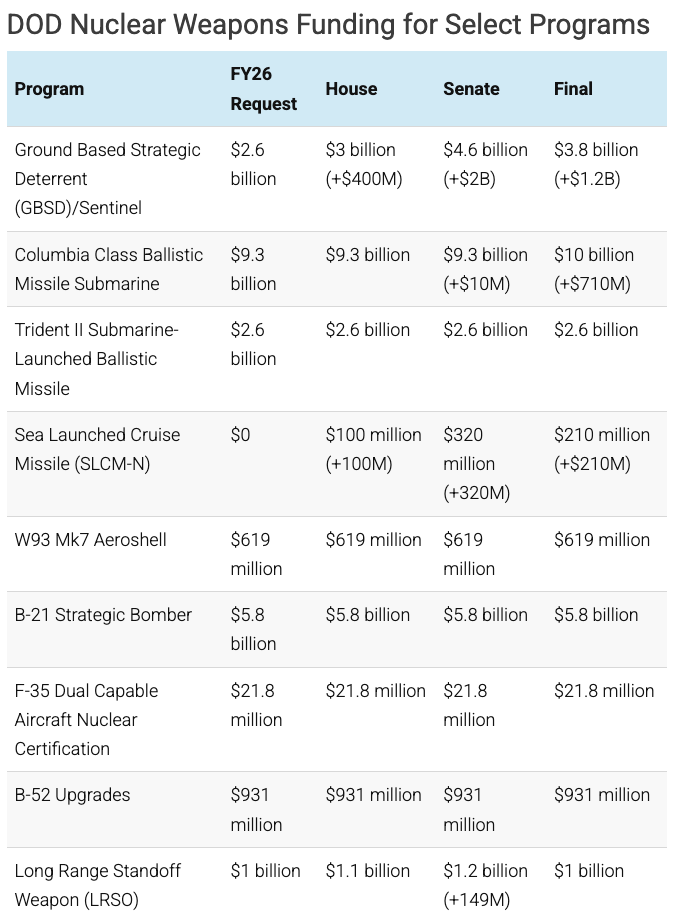

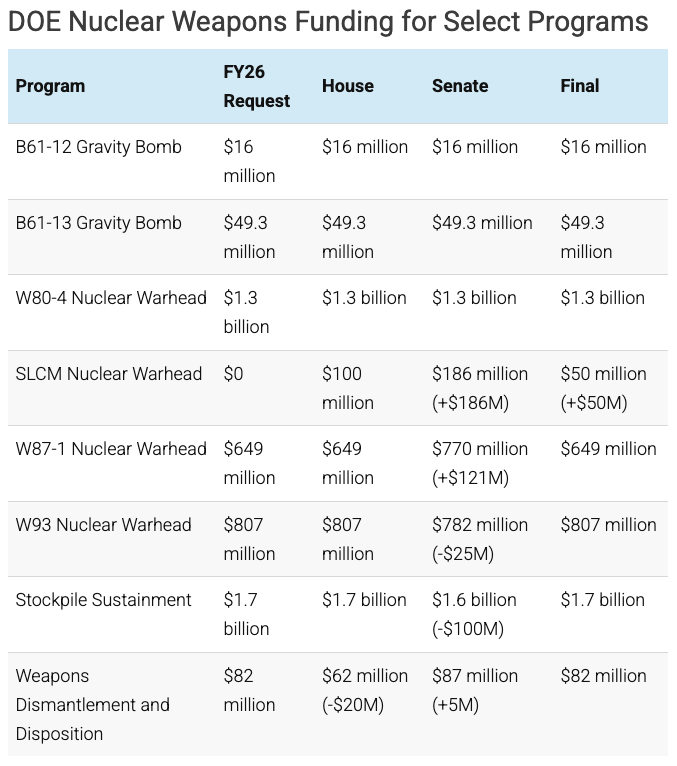

Congress’ new annual defense spending package, passed on December 17, authorizes $8 billion more than the Trump administration requested, for a total of $901 billion. The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them. Below is an overview of provisions of note in the new NDAA related to nuclear weapons.

Sentinel / Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles