Rising China Sells More Weapons

“In 2018, China’s arms sales increased, continuing a trend that enabled China to become the world’s fastest-growing arms supplier during the past 15 years,” according to the 2019 China Military Power report published by the Department of Defense. “From 2013 through 2017, China was the world’s fourth-largest arms supplier, completing more than $25 billion worth of arms sales.”

“Arms transfers also are a component of China’s foreign policy, used in conjunction with other types of military, economic aid, and development assistance to support broader foreign policy goals,” the Pentagon report said. “These include securing access to natural resources and export markets, promoting political influence among host country elites, and building support in international forums.”

Needless to say, the United States and other countries have long done the same thing, using arms exports as an instrument of foreign policy and political influence. Up to a point, however, US arms sales are regulated by laws that include human rights and other considerations. See U.S. Arms Sales and Human Rights: Legislative Basis and Frequently Asked Questions, CRS In Focus, May 2, 2019.

To assist soldiers in identifying Chinese weapons in the field, the US Army has produced a deck of “playing cards” featuring various weapons systems.

“The Worldwide Equipment Identification Playing Cards enable Soldiers to be able to readily identify enemy equipment and distinguish the equipment from friendly forces. Cards can be used at every level and across all services.” See Worldwide Equipment Identification Cards: China Edition, US Army TRADOC, April 2019.

USAF Seeks “Resilient” Nuclear Command and Control

The US Air Force last week updated its guidance on the command and control of nuclear weapons to include protection against electromagnetic pulse and cyber attack, among other changes. See Air Force Nuclear Command, Control, and Communications (NC3), Air Force Instruction 13-550, April 16, 2019.

“This is a complete revision to the previous version of this instruction,” the new guidance states. “It revises the command relationships, roles and responsibilities, the governance structure, and addresses resourcing, architecture and configuration management, resilience, and assessments.”

“Resilience” here pertains particularly to “two of the most broadly applied challenges: hardening against the effects of electromagnetic pulse and threats in the cyberspace domain.” These topics were scarcely mentioned at all in the previous version of the Air Force Instruction that was issued in 2014, nor did the term resilience appear in the earlier document.

Several new classified directives on nuclear command and control have been issued in recent years (such as Presidential Policy Directive-35 and others) and their content is reflected at least indirectly and in part in the new unclassified USAF guidance.

A broader modernization of the nation’s entire nuclear command, control and communications system is underway at U.S. Strategic Command, costing a projected $77 billion over the coming decade. See “STRATCOM to design blueprint for nuclear command, control and communications” by Sandra Erwin, Space News, March 29, 2019.

Electronic Warfare, and More from CRS

Noteworthy new publications from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Defense Primer: Electronic Warfare, CRS In Focus, updated April 12, 2019

U.S. Military Electronic Warfare Research and Development: Recent Funding Projections, CRS Insight, April 15, 2019

Assessing Commercial Disclosure Requirements under the First Amendment, April 23, 2019

The National Institutes of Health (NIH): Background and Congressional Issues, updated April 19, 2019

The Federal Communications Commission: Current Structure and Its Role in the Changing Telecommunications Landscape, April 18, 2019

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress, April 23, 2019

Can the President Close the Border? Relevant Laws and Considerations, CRS Legal Sidebar, April 12, 2019

Central American Migration: Root Causes and U.S. Policy, CRS In Focus, March 27, 2019

Cooperative Security in the Middle East: History and Prospects, CRS In Focus, updated April 11, 2019

International Criminal Court: U.S. Response to Examination of Atrocity Crimes in Afghanistan, CRS Insight, updated April 16, 2019

Nuclear Cooperation: Part 810 Authorizations, CRS In Focus, April 18, 2019

U.S. War Costs, Casualties, and Personnel Levels Since 9/11, CRS In Focus, April 18, 2019

Pentagon Blocks Declassification of 2018 Nuclear Stockpile

For the first time in years, the Department of Defense has denied a request to declassify the current size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile.

“After careful consideration. . . it was determined that the requested information cannot be declassified at this time,” wrote Andrew P. Weston-Dawkes of the Department of Energy in a letter conveying the DoD decision not to disclose the number of warheads in the U.S. arsenal at the end of Fiscal Year 2018 or the number that had been dismantled.

The Federation of American Scientists had sought declassification of the latest stockpile figures in an October 1, 2018 petition. It is this request that was denied.

Because the current size of the U.S. nuclear stockpile constitutes so-called “Formerly Restricted Data,” which is a classification category under the Atomic Energy Act, its declassification requires the concurrence of both the Department of Energy and the Department of Defense. In this case, DOE did not object to declassification but DOD did.

* * *

The size of the current stockpile was first declassified in 2010. It was one of a number of breakthroughs in open government that were achieved in the Obama Administration. (Until that time, only the size of the historic stockpile through 1961 had been officially disclosed, which was done in 1993.)

“Increasing the transparency of our nuclear weapons stockpile, and our dismantlement, as well, is important to both our nonproliferation efforts and to the efforts we have under way to pursue arms control that will follow the new START treaty,” said a Pentagon official at a May 2010 press briefing on the decision to release the information.

In truth, the size of the U.S. nuclear stockpile was not such a big secret even when it was classified. Before the 2009 total of 5,113 warheads was declassified in 2010, Hans Kristensen and Robert Norris of FAS had estimated it at 5,200 warheads. Likewise, while the 2013 total turned out to be 4,804 warheads, their prior open source estimate was not too far off at 4,650 warheads.

But even if it is partly a formality, classifying stockpile information means that officials cannot publicly discuss it or be effectively questioned in public about it.

* * *

But why now? Why is the Pentagon reverting to the pre-Obama practice of keeping the total stockpile number and the number of dismantled weapons classified? Why could the FY 2017 total (3,822 warheads) be disclosed, while the FY 2018 total cannot?

No reason was provided in the latest denial letter, and none of the decision makers was available to explain the rationale behind it.

But another official said the problem was that one of the main purposes of the move to declassify the stockpile total — namely, to set an example of disclosure that other countries would follow — had not been reciprocated as hoped.

“Stockpile declassification has not led to greater openness by Russia,” the official said.

“Anyway, it’s not a bilateral world anymore,” he said. And so DoD would also be looking for greater transparency from China than has been realized up to now.

Have new U.S. nuclear weapons programs played a role in incentivizing greater secrecy? “I doubt it,” this official said. “If anything, it’s the reverse. The US government has a motive to make it clear where it’s headed.”

* * *

“I think we should have more communication with Russia,” said U.S. Army Gen. Curtis Scaparrotti, the retiring Supreme Allied Commander Europe. “It would ensure that we understand each other and why we are doing what we’re doing.”

But for now, that’s not the direction in which things are moving, and not only with respect to stockpile secrecy. See “US-Russia chill stirs worry about stumbling into conflict” by Robert Burns, Associated Press, April 14.

Pentagon Cancels Contract for JASON Advisory Panel

Updated below

In a startling blow to the system of independent science and technology advice, the Department of Defense decided not to renew its support for the JASON defense science advisory panel, it was disclosed yesterday.

“Were you aware that [the JASON contract] has been summarily terminated by the Pentagon?”

That was one of the first questions asked by Rep. Jim Cooper, chair of the House Armed Services Committee Strategic Forces Subcommittee, at a hearing yesterday (at about 40’20”).

NNSA Administrator Lisa Gordon-Hagerty replied that she was aware that the Pentagon had taken some action, and said that she had asked her staff to find out more. She noted that NNSA has an interest in maintaining the viability of the JASON panel, particularly since “We do have some ongoing studies with JASON.”

In fact, JASON performs technical studies for many agencies inside and outside of the national security bureaucracy and it is highly regarded for the quality of its work.

So why is the Pentagon threatening its future?

Even to insiders, the DoD’s thought process is obscure and uncertain.

“To understand it you first have to understand the existing contract structure,” one official said. “This is a bit arcane, but MITRE currently has an Indefinite Delivery / Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) contract with the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), the purpose of which is to manage and operate the JASON effort. However, you don’t actually do anything with an IDIQ contract; rather, the purpose of the IDIQ contract [is to] have Task Orders (TO’s) placed on it. These TO’s are essentially mini-contracts in and of themselves, and all the actual work is performed according to the TO’s. This structure allows any government agency to commission a JASON study; conceptually, all you need to do is just open another TO for that study. (The reality is slightly more complicated, but that’s the basic idea).”

“The underlying IDIQ contract has a 5-year period of performance, which just expired on March 31. Last November, OSD started the process of letting a new 5-year IDIQ contract with essentially the same structure so that the cycle could continue. They decided to compete the contract, solicited bids, and were going to announce the contract award in mid-March. Instead, what happened is that about two weeks ago (March 28, two days before the expiration of the existing IDIQ contract) they announced that they were canceling the solicitation and would not be awarding another contract at all. Instead, they offered to award a single contract for a single study without the IDIQ structure that allows other agencies to commission studies.”

But “I do not know the reason” for the cancellation, the official said.

And so far, those who do know are not talking. The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Research and Engineering) “would not answer any questions or discuss the matter in any way whatsoever.”

The news was first reported in “Storied Jason science advisory group loses contract with Pentagon” by Jeffrey Mervis and Ann Finkbeiner in Science magazine, and was first noticed by Stephen Young.

The JASON panel has performed studies (many of which are classified) for federal agencies including the National Nuclear Security Administration, the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Reconnaissance Office, as well as the Census Bureau and the Department of Health and Human Services.

Lately, the Department of Agriculture denied a Freedom of Information Act request for a copy of a 2016 JASON report that it had sponsored entitled “New Techniques for Evaluating Crop Production.” The unclassified report is exempt from disclosure under the deliberative process privilege, USDA lawyers said. That denial is under appeal.

The Pentagon move to cancel the JASON contract appears to be part of a larger trend by federal agencies to limit independent scientific and technical advice. As noted by Rep. Cooper at yesterday’s hearing, the Navy also lately terminated its longstanding Naval Research Advisory Committee.

Update, 4/25/19: National Public Radio and Defense News reported that the National Nuclear Security Administration has posted a solicitation to take over the JASON contract from the Department of Defense.

Leaks of Classified Info Surge Under Trump

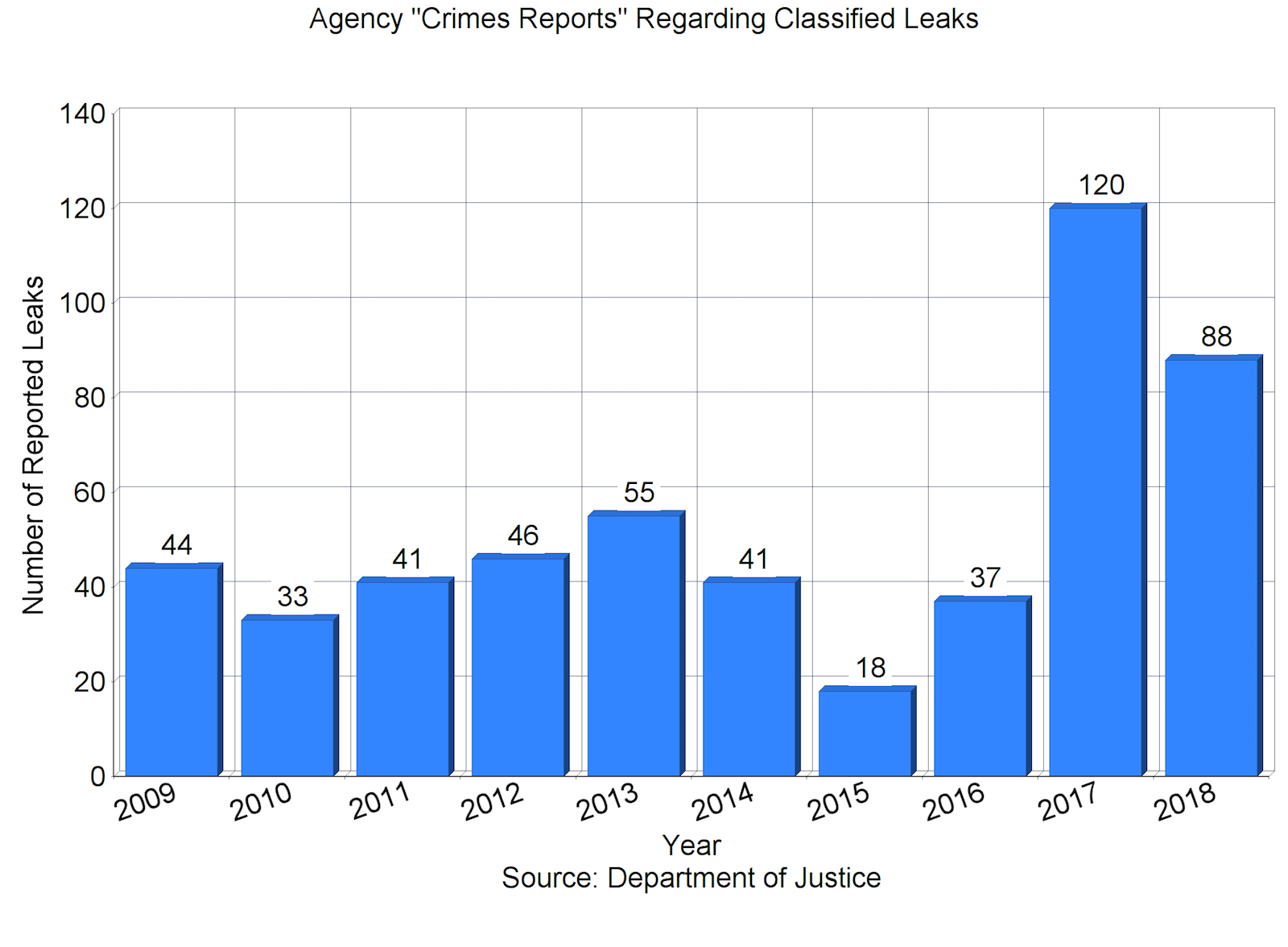

The number of leaks of classified information reported as potential crimes by federal agencies reached record high levels during the first two years of the Trump Administration, according to data released by the Justice Department last week.

Agencies transmitted 120 leak referrals to the Justice Department in 2017, and 88 leak referrals in 2018, for an average of 104 per year. By comparison, the average number of leak referrals during the Obama Administration (2009–2016) was 39 per year.

There are a “staggering number of leaks,” then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions said at an August 4, 2017 briefing about efforts to prevent the unauthorized disclosures.

“Referrals for investigations of classified leaks to the Department of Justice from our intelligence agencies have exploded,” AG Sessions said at that time. He outlined several steps that the Administration would take to combat leaks of classified information, including tripling the number of active leak investigations by the FBI.

“We had about nine open investigations of classified leaks in the last 3 years,” he told the House Judiciary Committee at a November 2017 hearing. “We have 27 investigations open today.” (Some of those investigations pertain to leaks that occurred before President Trump took office.)

“We intend to get to the bottom of these leaks. I think it reached—has reached epidemic proportions. It cannot be allowed to continue,” Sessions said then, “and we will do our best effort to ensure that it does not continue.”

But it has continued. Despite preventive efforts, the 2018 total of 88 leak referrals was still higher than any reported pre-Trump figure. (The previous high in recent decades had been 55 referrals in 2013 and in 2007. The lowest was 18 in 2015.)

*

Not all leaks of classified information generate such criminal referrals. Disclosures that are inadvertent, insignificant, or officially authorized would not be reported to the Justice Department as suspected crimes.

Meanwhile, only a fraction of the classified leaks that are reported by agencies ever result in an investigation, and only a portion of those lead to identification of a suspect and even fewer to a prosecution.

“While DOJ and the FBI receive numerous media leak referrals each year, the FBI opens only a limited number of investigations based on these referrals,” the FBI told Congress in 2009. “In most cases, the information included in the referral is not adequate to initiate an investigation.”

The newly released aggregate data on classified leak referrals serve as a reminder that leaks of classified information are a “normal,” predictable occurrence. There is not a single year in the past decade and a half for which data are available when there were no such criminal referrals.

But the data as released leave several questions unanswered. They do not reveal how many of the referrals actually triggered an FBI investigation. They do not indicate whether the leaks are evenly distributed across the national security bureaucracy or concentrated in one or more “problem” agencies (or congressional committees). And they do not distinguish between leaks that simply “hurt our country,” as the Attorney General put it, and those that are complicated by a significant public interest in the information that was disclosed.

Navy Torpedoes Scientific Advisory Group

This week the U.S. Navy abruptly terminated its own scientific advisory group, depriving the service of a source of internal critique and evaluation.

The Naval Research Advisory Committee (NRAC) was established by legislation in 1946 and provided science and technology advice to the Navy for the past 73 years. Now it’s gone.

The decision to disestablish the Committee was announced in a March 29 Federal Register notice, which did not provide any justification for eliminating it. Phone and email messages to the office of the Secretary of the Navy seeking more information were not returned.

“I think it’s a shortsighted move,” said one Navy official, who was not part of the decisionmaking process.

This official said that the Committee had been made vulnerable by an earlier effort to reduce the number of Navy advisory committees. Instead of remaining an independent entity, the NRAC was redesignated as a sub-committee of the Secretary of the Navy Advisory Panel, which provides policy advice to the Secretary. It was a poor fit for the NRAC technologists, the official said, since they don’t do policy and were thus “misaligned.” When the Secretary decided to eliminate the Panel, the NRAC was swept away with it.

Did the NRAC do or say something in particular to trigger the Navy’s wrath? If so, it’s unclear what that might have been. “This is the most highly professional crew I’ve seen,” the Navy official said. “They stay between the lines.”

The NRAC was the Navy counterpart to the Army Science Board and the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board. It has no obvious replacement.

“This will leave the Navy without an independent and objective technical advisory body, which is not in the best interests of the Navy or the nation,” said a Navy scientist.

According to the NRAC website (which is still online for now), “The Naval Research Advisory Committee (NRAC) is an independent civilian scientific advisory group dedicated to providing objective analyses in the areas of science, research and development. By its recommendations, the NRAC calls attention to important issues and presents Navy management with alternative courses of action.”

Its mission was “To know the problems of the Navy and Marine Corps, keep abreast of the current research and development programs, and provide an independent, objective assessment capability through investigative studies.”

A 2017 report on Autonomous and Unmanned Systems in the Department of the Navy appears to be the NRAC’s most recent unclassified published report.

Under Secretary of the Navy Thomas B. Modly ordered disestablishment of the NRAC in a 21 February 2019 memo.

“This was a sudden and unexpected move according to people I know,” said the Navy scientist. “I have not yet seen an explanation for its termination.”

DNI: IC Should be “Model Employer” for Disabled Persons

New policy guidance from the Director of National Intelligence directs the U.S. intelligence community to provide equal opportunities “for the hiring, placement, and advancement of qualified individuals with disabilities,” as required by law.

“IC elements shall be model employers for individuals with disabilities,” wrote DNI Dan Coats. See Employment of Individuals with Disabilities, Intelligence Community Policy Guidance 110.1, February 26, 2019.

As of 2017, 7.9% of the U.S. intelligence community workforce was made up of persons with disabilities, compared to an 8.99% disability rate in the federal workforce and 17.5% in the overall civilian labor force. (A disability is “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of an individual.”)

“Persistent workplace challenges continue to exist for women, minorities, and persons with disabilities in the IC. Unfortunately, the IC’s aggressive efforts to improve diversity and inclusion are not having their intended effects,” according to a 2017 ODNI report on the subject (that pre-dated the appointment of Gina Haspel as CIA Director).

While many of the challenges facing disabled persons are generic and widespread, some are unique to intelligence agencies.

“Employees with disabilities may… be specifically challenged by sitting for a polygraph. Participants expressed concern that certain disabilities, such as mobility limitations or respiratory impairments, may impact polygraph testing results.”

The premise of the declared IC policy on diversity and inclusion is that it benefits the country by enabling the employment of qualified persons who would otherwise be excluded from the workforce or denied full participation. Of all disfavored groups, disabled persons reflect the broadest cross section of the public.

“A disability can happen to anyone, at any point in life, and is the one variable that crosses all demographic lines,” the ODNI study said. “Greater diversity exists among persons with disabilities than for any other demographic group, but they may be the least understood by society at large, and by extension, by decision makers and the general workforce within the IC.”

Declassified U2 Photos Open a New Window into the Past

Updated below

Archaeologists are using declassified imagery captured by U2 spy planes in the 1950s to locate and study sites of historical interest that have since been obscured or destroyed.

This work extends previous efforts to apply CORONA spy satellite imagery, declassified in the 1990s, to geographical, environmental and historical research. But the U2 imagery is older and often of higher resolution, providing an even further look back.

“U2 photographs allowed us to present a more complete picture of the archaeological landscape than would have otherwise been possible,” wrote archaeologists Emily Hammer and Jason Ur in a new paper. See Near Eastern Landscapes and Declassified U2 Aerial Imagery, Advances in Archaeological Practice, published online March 12, 2019.

The exploitation of U2 imagery required some ingenuity and entrepreneurship on the authors’ part, especially since the declassified images are not very user-friendly.

“Logistical and technical barriers have for more than a decade prevented the use of U2 photography by archaeologists,” they noted. “The declassification included no spatial index or finding aid for the planes’ flight paths or areas of photographic coverage. The declassified imagery is not available for purchase or download; interested researchers must photograph the original negatives at the NARA II facility in College Park, Maryland.”

Since no finding aids existed, the authors created them themselves. Their paper also contains links to web maps to help other researchers locate relevant film cans and order them for viewing in College Park.

“These [U2] photographs are a phenomenal historical resource,” said Professor Ur. “Have a look at Aleppo in 1959 and Mosul in 1958. These places are now destroyed.”

Update: Related work involving declassified aerial imagery in the UK was described in “Use of archival aerial photographs for archaeological research in the Arabian Gulf” by Richard N. Fletcher et al, Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 48 (2018): 75–82:

- Summary

A valuable archaeological and historical resource is contained within recently declassified aerial imagery from the UK’s Joint Aerial Reconnaissance Intelligence Centre (JARIC), now held at the National Collection of Aerial Photography in Edinburgh (NCAP). A project at UCL-Qatar has begun to exploit this to acquire and research the historical aerial photography of Qatar and the wider Gulf region. The JARIC collection, comprising perhaps as many as 25 million photographs from British intelligence sources in the twentieth century, mainly from Royal Air Force reconnaissance missions, is known to include large quantities of aerial photography from the Gulf that have never been seen outside intelligence circles, dating from 1939 to 1989. This paper will demonstrate how others may gain access to this valuable resource, not only for the Gulf but for the entire MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region. We will explore the research value of these resources and demonstrate how they enrich our understanding of the area. The archive is likely to be of equal value to archaeologists and historians of other regions.

Enforcing Compliance with Congressional Subpoenas

The House Judiciary Committee said that it will meet this week to authorize a subpoena for release (to Congress) of the complete Mueller report, without redactions, as well as the supporting evidence gathered by the now-concluded Special Counsel investigation.

If a subpoena is issued, what happens then?

“When Congress finds an inquiry blocked by the withholding of information by the executive branch, or where the traditional process of negotiation and accommodation is inappropriate or unavailing, a subpoena — either for testimony or documents — may be used to compel compliance with congressional demands,” a new report from the Congressional Research Service explains. “The recipient of a duly issued and valid congressional subpoena has a legal obligation to comply, absent a valid and overriding privilege or other legal justification.”

However, “the subpoena is only as effective as the means by which it may be enforced. Without a process by which Congress can coerce compliance or deter non-compliance, the subpoena would be reduced to a formalized request rather than a constitutionally based demand for information.”

Today, Congress has a limited set of tools at its disposal to enforce subpoenas.

“Congress currently employs an ad hoc combination of methods to combat non-compliance with subpoenas,” including criminal contempt citations and civil enforcement. “But these mechanisms do not always ensure congressional access to requested information,” CRS said.

To compel executive branch compliance with a subpoena, additional steps may be necessary.

“There would appear to be several ways in which Congress could alter its approach to enforcing committee subpoenas issued to executive branch officials,” the new CRS report said.

“These alternatives include the enactment of laws that would expedite judicial consideration of subpoena-enforcement lawsuits filed by either house of Congress; the establishment of an independent office charged with enforcing the criminal contempt of Congress statute; or the creation of an automatic consequence, such as a withholding of appropriated funds, triggered by the approval of a contempt citation. In addition, either the House or Senate could consider acting on internal rules of procedure to revive the long-dormant inherent contempt power as a way to enforce subpoenas issued to executive branch officials.”

In any case, “Congress’s ability to issue and enforce its own subpoenas is essential to the legislative function and an ‘indispensable ingredient of lawmaking’,” CRS said (quoting a 1975 US Supreme Court opinion). See Congressional Subpoenas: Enforcing Executive Branch Compliance, March 27, 2019.

* * *

Other noteworthy new publications from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Congressional Participation in Litigation: Article III and Legislative Standing, updated March 28, 2019

Assessing NATO’s Value, updated March 28, 2019

FY2020 Defense Budget Request: An Overview, CRS Insight, updated March 26, 2019

Defense Primer: Military Use of the Electromagnetic Spectrum, CRS In Focus, March 27, 2019

Defense Primer: U.S. Policy on Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems, CRS In Focus, March 27, 2019

Iraq: Issues in the 116th Congress, March 26, 2019

Free Speech and the Regulation of Social Media Content, March 27, 2019

The Longest “Emergency”: 40 Years and Counting

Yesterday, the Department of Justice announced that an Australian man had been sentenced to 24 months in prison for illegally exporting aircraft parts and other items to Iran without a license, in violation of a law known as the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). The case relied on a 1979 declaration of national emergency that remains in force.

The IEEPA, which gives the President the power to regulate certain economic transactions, can only be used under conditions of a national emergency. But it is the most frequently used of all of the reported 123 emergency statutes that have been adopted under the National Emergencies Act.

A major new report from the Congressional Research Service documents the history and application of the IEEPA as a tool of presidential emergency power. See The International Emergency Economic Powers Act: Origins, Evolution, and Use, March 20, 2019.

The “emergency” that made it possible to apply the IEEPA against the Austrailian exporter who was sentenced yesterday is the first, the oldest and the longest emergency ever declared under the National Emergencies Act. It was pronounced by President Carter in response to the seizure of the U.S. embassy by Iran in 1979.

“Six successive Presidents have renewed that emergency annually for nearly forty years,” CRS noted, and it “may soon enter its fifth decade… As of March 1, 2019, that emergency is still in effect, largely to provide a legal basis for resolving matters of ownership of the Shah’s disputed assets.”

In ordinary language, a condition that persists for decades cannot properly be termed an “emergency.”

Such “permanent emergencies are unacceptable,” wrote Elizabeth Goitein of the Brennan Center for Justice in a March 17 Wall Street Journal op-ed. “Once approved by Congress, states of emergency should expire after six months unless Congress votes to renew them,” she suggested, “and no emergency should exceed five years. Conditions lasting that long are not unforeseen or temporary, which are basic elements of an emergency.”

* * *

Some other noteworthy new publications from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Evaluating DOD Strategy: Key Findings of the National Defense Strategy Commission, CRS In Focus, March 19, 2019

International Trophy Hunting, March 20, 2019

U.S. Global Health Assistance: FY2017-FY2020 Request, CRS In Focus, updated March 14, 2019

U.S. Health Care Coverage and Spending, CRS In Focus, updated March 21, 2019

Federal Disaster Assistance for Agriculture, CRS In Focus, updated March 19, 2019

Europe’s Refugee and Migration Flows, CRS In Focus, updated March 20, 2019

U.S. Intelligence Community (IC): Appointment Dates and Appointment Legal Provisions for Selected IC Leadership, CRS In Focus, updated March 19, 2019

Proposed Air Force Acquisition of New F-15EXs, CRS Insight, March 19, 2019

Judicial Nomination Statistics and Analysis: U.S. District and Circuit Courts, 1977-2018, March 21, 2019

A Low-Yield, Submarine-Launched Nuclear Warhead: Overview of the Expert Debate, CRS In Focus, March 21, 2019

Demolishing and Creating Norms of Disclosure

By refusing to disclose his tax returns, President Trump has breached — and may have demolished — the longstanding norm under which sitting presidents and presidential candidates are expected to voluntarily disclose their federal tax returns. At the same time, there is reason to think that new norms of disclosure can be created.

The conditions under which Congress could legally obtain President Trump’s federal tax returns were reviewed in a new assessment from the Congressional Research Service.

CRS “analyzes the ability of a congressional committee to obtain the President’s tax returns under provisions of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC); whether the President or the Treasury Secretary might have a legal basis for denying a committee request for the returns; and, if a committee successfully acquires the returns, whether those returns legally could be disclosed to the public.” See Congressional Access to the President’s Federal Tax Returns, CRS Legal Sidebar, March 15, 2019.

Against this backdrop of defiant presidential secrecy, it is interesting to note that the Department of Defense yesterday disclosed the amount of its FY2020 request for the Military Intelligence Program (MIP), as it has now done for several years. This is a practice that was adopted for the first time by the Obama Administration, even though no law or regulation required it. To the contrary, it had previously been considered classified information. (Disclosure of the budget request for the National Intelligence Program, which also occurred yesterday, has been required by statute since 2010.)

Today, disclosure of the MIP budget request and other intelligence budget information is such a regular event that it is taken for granted. It is one of several new milestones in disclosure of national security information that were achieved in the Obama years, many of which survive to the present.

* * *

Some other new and updated publications from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Arms Control and Nonproliferation: A Catalog of Treaties and Agreements, updated March 18, 2019

Direct Overt U.S. Aid Appropriations for and Military Reimbursements to Pakistan, FY2002-FY2020, updated March 12, 2019

Nord Stream 2: A Fait Accompli?, CRS In Focus, March 18, 2019

U.S. Global Health Assistance: FY2017-FY2020 Request, CRS In Focus, updated March 14, 2019

Low Interest Rates, Part III: Potential Causes, CRS Insight, March 15, 2019

Farm Debt and Chapter 12 Bankruptcy Eligibility, CRS Insight, March 15, 2019

Huawei v. United States: The Bill of Attainder Clause and Huawei’s Lawsuit Against the United States, CRS Legal Sidebar, March 14, 2019

Special Counsels, Independent Counsels, and Special Prosecutors: Legal Authority and Limitations on Independent Executive Investigations, updated March 13, 2019