We Can’t Build Things if We Don’t Fix Government Hiring

In the last three years, the Biden Administration has passed a wave of legislation to address infrastructure, climate, and economic vulnerabilities: the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and the CHIPS and Science Act (CHIPS). These key laws provide funding and support to rebuild bridges, increase internet access, replace aging water systems, invest in clean energy technologies, build advanced semiconductor factories, and much more. These projects can improve the lives of all Americans, but all have one common implementation bottleneck: permitting.

Permits underpin many of these projects because they are required for the use of land and other resources under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, and other laws. This means that before building can begin, environmental specialists, scientists, engineers, attorneys, and other experts need to form federal agency permitting teams to conduct environmental assessments, analyses, community engagement, and legal reviews to provide the required permits and authorizations.

Prior to these new bills passing, the federal permitting workforce was already overwhelmed, according to agency professionals. With the implementation of BIL, IRA, and CHIPS, the demand for permitting has only ballooned, driven by these investments in our future; changing laws, regulations, and policies impacting permitting; and the need for more environmental reviews and authorizations. Additionally, improving existing processes and technology tools to increase transparency and manage the permitting workload has engendered complexity. Not only does this further the need for new talent and skill sets that vary from traditional permitting teams, but it also leads to thousands of new customers beginning new, modernized processes. The Permitting Dashboard, owned by the Permitting Council, illustrates the status of some permitting projects and shows over 7,400 permitting projects planned, in progress, or paused as of September 2024. These demands far exceed the current workforce capacity.

The federal government is looking to address their surge hiring needs, but have run into challenges. In FY24, there were just under 11,000 full time employee permitting roles anticipated to be hired. However, hiring efforts have run into a number of barriers. Process delays caused by siloed ownership across the hiring process and outdated job descriptions; finding, selecting, or creating an assessment strategy; a need to reclassify roles; required multi-stakeholder reviews; and background checks have all slowed progress. Many of these have been exacerbated by the need for interdisciplinary permitting roles. Appropriation delays, misunderstanding regarding hiring flexibilities and authorities, and insufficient candidate pools have presented additional challenges for HR leaders, hiring managers, and HR specialists to navigate together. Additionally, the type of permitting work conducted and thus, the hiring needs, vary across agencies based on their mission and role in the permitting process, presenting challenges for collaboration and centralized solutions. Outdated federal hiring policies limit agency’s ability to recruit in a more competitive and geographically dispersed manner.

Most of these hiring challenges are not unique to permitting. Rather, they illustrate the pain points experienced by hiring managers, HR specialists, and HR leaders across government. Permitting hiring challenges are merely a microcosm of federal hiring and can serve as an example to identify critical talent reforms.

In the short term, all agencies involved in the permitting process need to prioritize hiring for permitting roles. The Biden Administration, agency leadership, and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) need to be focused on finding solutions to address these process bottlenecks, and agencies should be looking for opportunities to collaborate and support their shared hiring goals through activities such as, pooled hiring, shared certifications, and standardized agency job descriptions. Implementation of the guidance and recommendations in a recent OPM-OMB Memo on Improving the Federal HIring Experience will help close many of these hiring challenges for agency permitting teams.

Without the permitting workforce needed for implementation, the American public will not reap the benefits of this new legislation. A diversified energy portfolio, improved and safe transportation systems, rural broadband access, resilient supply chains, and clean, accessible water will remain unattainable. The federal hiring process is the linchpin to onboarding this critical talent, and agency leaders are key to prioritizing these efforts. Our nation has not had this opportunity for decades; we do not want to let this moment pass. But if we are not able to build the government capacity needed for implementation, the impact of this historic legislation will go unrealized.

Fixing federal permitting requires the right (digital) tools for the job. We built an inventory of them.

A recent wave of historic federal investments in climate resilience, the clean energy transition, and new infrastructure charges the government with delivering on a broad range of ambitions. Those efforts will succeed or fail based on our government’s ability to implement—that is, to responsibly permit, site, build, and deploy key infrastructure and related projects. Given the importance of federal permitting in that equation, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) and the Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC) are collaborating to take advantage of a key window of opportunity for permitting innovation.

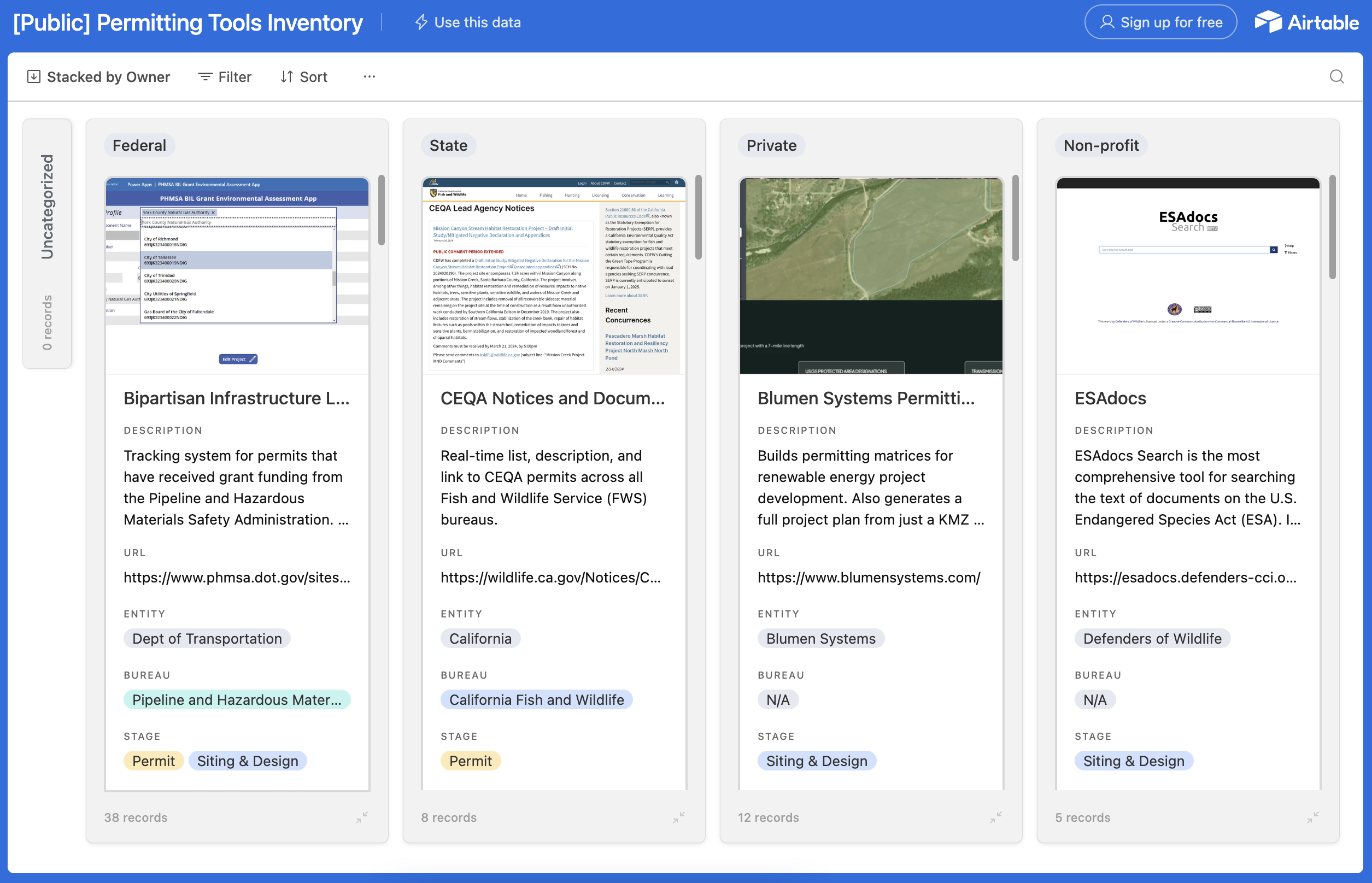

As part of our efforts, we are focused on documenting the status quo in permitting technology, identifying bright spots and best practices where they exist, and making recommendations for center-of-government entities that can help agencies build, buy, and deploy better tools and processes. The latest of those efforts is an inventory of digital environmental permitting tools; a beta version of this inventory is now available. We built the inventory to provide a snapshot of the permitting technology landscape, and to open lines of dialogue for cross-application and cross-agency learning.

Permitting tools in this inventory range widely in intended use cases and maturity levels. Most agency permitting tools we found are single-agency built and used, and in many cases, could be improved by reducing feature fragmentation and improving content reliability (more on that below!).

Why we built this inventory

Systems and digital tools play an important role at every stage of the permitting process. From project siting and design, to permit application steps and post-permit activities, agencies use digital tools for an array of tasks throughout the permitting “life-cycle”—including for things like permit data collection and application development, analysis, surveys, and impact assessments, as well as public comment processes and post-permit monitoring. With the assistance of those tools, members of the public learn about the details of proposed projects and provide input through online public commenting platforms; in turn, agencies receive, store, and analyze community input and recommendations.

Understanding and improving how the federal government builds, buys, and deploys the technology that enables those activities can play a key role in accelerating permit timelines, lowering costs, expanding access to key information, and improving the rigor of permitting analysis. We built this inventory to enhance our collective understanding of how that software is used in the federal permitting process—and to open lines of dialogue for cross-agency and cross-sector learning.

The inventory is currently in draft form; a final version will be shared in the coming weeks.

Historic federal investments in climate resilience, the clean energy transition, and new infrastructure will hinge on the government’s ability to efficiently permit, site, and build key projects. That’s why EPIC and the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) are collaborating on strategies and resources to help accelerate permitting innovation.

It’s clear that there is ample momentum, dedicated resources, and an urgency among federal leaders to act to accelerate permitting’s speed and efficiency. In a recent public comment, we argued that National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) reforms should be conceived, developed, and deployed with the end users in mind. Similarly, agencies should consider how reforms and permitting modernization projects might leverage technology to improve how agency permitting teams, project sponsors, and the affected public engage with the process.

What this inventory includes

This inventory catalogs more than sixty permitting applications (software) across federal and state agencies, non-profit organizations, and private companies. Aside from the state-level tools, all applications we cataloged apply to federal NEPA permitting. We included state tools because they are examples federal and private developers can learn from.

While many software programs are used throughout the environmental permitting process, this compilation only includes those tools that are expressly intended for steps in the permitting process. The inventory emphasizes applications that are publicly accessible or advertised, rather than a comprehensive list of internal systems. We sourced these applications from staff interviews with the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), the Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Department of Energy (DOE)—as well as through federal agency permitting websites, Google keyword searches1, and snowball sampling from private companies.

What we learned

Much of what we discovered as we found, analyzed, and cataloged the permitting tools in the inventory wasn’t surprising—and we see ample opportunity for more learning and improvements across tools. Initial take-aways from our analysis include:

Bright spots exist among the many permitting tools out there—including applications that center user needs and leverage innovative technology. Much of the innovation we see in permitting tools is happening in the private sector—but with major potential for federal use cases. For instance, breakthroughs in geospatial analysis and machine learning-empowered decision support are improving methods for siting and designing projects, reducing the time spent conducting feasibility studies, and on-the-ground surveying. Moreover, Artificial Intelligence (AI) text analysis and user-centered design are enabling rapid document writing, public comment processing, and easy to navigate databases. Real-time remote sensing and geospatial imaging innovations have also expanded the frontier of post-permit monitoring.

Permitting tools in this inventory range widely in intended use cases and maturity levels. Applications we found span project siting and design, permitting, and post-permit activities—and range in age from two months to more than twenty years of active use. The most frequent intended user base of federal tools appears to be decision makers and officials, as opposed to field staff or public stakeholders. The public sector has primarily built project record databases, informational sites, and webforms for permit application development purposes. In contrast, the private sector’s tools are generally oriented toward pre-permitting geospatial analysis and scenario planning, as well as public comment submission and processing.

Most agency permitting tools we found are single-agency (including single-bureau) built and used. Over the past five years, several agencies have built permitting tools that incorporate transparency and public engagement best practices by making project information available online. Yet these tools—and the vast majority of others inventoried—are siloed across organizations since most are single-agency built and used, with the exception of the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) Database, which encompasses all federal permitting agencies. That reality makes missed opportunities for interagency coordination around permitting data the norm.

Content reliability issues and feature fragmentation are common, which could have implications for timeliness and implementation.

Content reliability. Nearly every agency’s NEPA-permitted project database had significant gaps in important content—including tens of thousands of missing projects and the absence of dates, documents, and geospatial location data. Because the data collected during permit development and project implementation isn’t systematically captured, stored, or made available in an interoperable system, that information is lost both to science as well as to data-driven adaptive management practices from which future permitting decisions would benefit. Without complete information, the public can’t adequately review projects in their own communities and agencies can’t perform permitting workflows at the pace, rigor, and scale needed to meet national environmental and infrastructure goals.

Feature fragmentation. Despite numerous common steps and data needs across tool users, agency workflows, and permitting stages, we found numerous instances of application features spread over multiple programs rather than in a consolidated application. This fragmentation is often the result of tools built in silos by different departments and/or at different points in time. Fragmentation increases confusion throughout the permitting process because users (including agency staff) must know the exact source of a particular piece of information, both to search for and record it. With multiple entry points, we often see inconsistent record-keeping and reporting as well as missing information.

Looking ahead

Forthcoming work from FAS and EPIC will build on this inventory with focused recommendations on how federal agencies can leverage technology as a core tool in permitting modernization efforts. More broadly, our teams are also working to support federal agencies in their efforts to innovate across a host of permitting policy, talent, data, and systems challenges. The North Star of this work is to empower leaders in and around government to plan, site, and build key environmental restoration and infrastructure projects faster, better, and at lower cost in the months and years ahead.

Is your tool missing from our permitting inventory? Interested in learning more about this work? Share your tools and any additional information with us!

This research was made possible with the generous support of Arnold Ventures.

Improving Environmental Outcomes from Infrastructure by Addressing Permitting Delays

Summary

With the Biden-Harris Administration and Congress together pursuing major infrastructure investments, there is an important question as to how best maximize potential economic and environmental benefits of new infrastructure. Reforming the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) is one of the most straightforward and impactful ways to do so. Currently, many major infrastructure projects are delayed due to significant, NEPA-mandated requirements for environmental-impact review. Such delays are frequently exacerbated by vague statutory requirements and exceptional litigation risks. Updated guidance for environmental reviews under NEPA, coupled with strategic judiciary reforms, could expedite infrastructure approval while improving environmental outcomes.

Congress and the Biden-Harris Administration should strive to clarify environmental regulatory requirements and standing for litigation under NEPA. Specific recommended actions include (i) establishing well-defined and transparent processes for public input on governmental environmental-impact statements, (ii) shortening the statute of limitations for litigation under NEPA from two years to 60– 120 days, and (iii) requiring that plaintiffs against governmental records of decision must have previously submitted public input on relevant environmental-impact statements.