US Army Views Chinese Military Tactics

How would China fight a war against the US?

A new US Army publication sets out to answer that question, offering a detailed account of the military tactics China could employ. See Chinese Tactics, Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 7-100.3, August 9, 2021.

The 250-page document is mainly intended to help provide a realistic basis for training of US forces. But in doing so it sheds some new light on China’s military forces, at least as they are perceived by US military observers. It is based primarily on open sources.

“This publication presents PLA [People’s Liberation Army] military theory largely as written and prescribed by the PLAA [PLA Army],” the manual says. “Real world practices of PLA units are . . . generally not included as part of the analysis underpinning this document.”

The description of Chinese military tactics is necessarily speculative to some extent. “The PLA has not participated in an active conflict in nearly half a century, so real-world applications are minimal. [But] available information on Chinese military training exercises and the few recent examples of conflict seem to indicate that PLA practices — including those of the PLAA — conform closely to its military theory.”

As for the command structure of the Chinese military, it “is complex and opaque to outsiders. . . . There are no fewer than ten different national-level command organizations in China, organized across at least three different levels of a complex hierarchy.”

“Deception plays a critical role in every part of the Chinese approach to conflict,” according to the document. “Rather than focusing on defeating the opponent in direct conflict — as most Western militaries do — [Chinese military] stratagems consider deception, trickery, and other indirect, perception-based efforts to be the most important elements of an operation.”

* * *

The current volume on China is the second in a new Army series on foreign military tactics. A previous volume on North Korean Tactics (ATP 7-100.2) was published last year. Two more volumes on Russian Tactics (ATP 7-100.1) and Iranian Tactics (ATP 7-100.4) are expected to appear later this year.

While unclassified, “these assessments are based on the most up-to-date information available,” wrote Army intelligence specialist Jennifer Dunn (“Training Today’s Army for Tomorrow’s Threats,” Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin, Oct-Dec 2020). “Subject matter experts within the Department of Defense and intelligence communities have vetted them, ensuring their veracity and applicability to the greater Army training and intelligence community.”

“It is also essential for the Army, especially for the regionally aligned elements, to thoroughly understand the adversary they are most likely to encounter in future conflicts,” she wrote, in an unwitting paraphrase of Sun Tzu’s famous dictum about knowing the enemy.

* * *

The US government can and should do far more to produce such open source materials on national security and foreign policy, say some members of Congress. A bill (HR 4747) sponsored by Rep. Joaquin Castro and several bipartisan colleagues, would create a new “Open Translation and Analysis Center (OTAC).”

“OTAC would be charged with translating into English important open source foreign-language material from the People’s Republic of China, Russia, and other countries of strategic interest,” according to a July 28 news release. “The translated material would be available on a public website, serving as a key resource for the U.S. and allied governments, media outlets, and academics and analysts around the world.”

“Along with translations, OTAC would provide information to help readers understand the meaning and significance of the published material. It would also produce key analyses of translated material to enhance the understanding of the governments and political systems it covers.”

For decades the US intelligence community provided open source materials to the public through the CIA’s Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS). But that mission has been abandoned by US intelligence and the Open Source Enterprise, the successor to FBIS, has gone completely dark as far as the public is concerned.

Pentagon Sees “Increased Potential” for Nuclear Conflict

The possibility that nuclear weapons could be used in regional or global conflicts is growing, said a newly disclosed Pentagon doctrinal publication on nuclear war fighting that was updated last year.

“Despite concerted US efforts to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in international affairs and to negotiate reductions in the number of nuclear weapons, since 2010 no potential adversary has reduced either the role of nuclear weapons in its national security strategy or the number of nuclear weapons it fields. Rather, they have moved decidedly in the opposite direction,” the Department of Defense document said.

“As a result, there is an increased potential for regional conflicts involving nuclear-armed adversaries in several parts of the world and the potential for adversary nuclear escalation in crisis or conflict.”

The publication presents an overview of U.S. nuclear strategy, force structure, targeting and operations. See Joint Nuclear Operations, JP 3-72, April 2020.

The document replaces a 2019 edition titled Nuclear Operations that was briefly disclosed and then withdrawn from a DoD website. (See “DoD Doctrine on Nuclear Operations Published, Taken Offline,” Secrecy News, June 19, 2019.)

The current document no longer includes some of the more unfiltered and enthusiastic language about achieving “decisive results” through nuclear strikes and “prevail[ing] in conflict” that appeared in the 2019 version. The statement that “The President authorizes the use of nuclear weapons” was changed to a more restrained declaration that “Only the President can authorize the use of nuclear weapons.”

Meanwhile, new material has been added, including an assessment that the threat from potential adversaries has grown even as the US nuclear posture is said to have been moderated:

“While the United States has continued to reduce the number and salience of nuclear weapons, others, including Russia and China, have moved in the opposite direction. They have added new types of nuclear capabilities to their arsenal, increased the salience of nuclear forces in their strategies and plans, and engaged in increasingly aggressive behavior.”

“Russia’s strategic nuclear modernization has increased, and will continue to increase, its warhead delivery capability, which provides Russia with the ability to rapidly expand its deployed warhead numbers.”

“China continues to increase the number, capabilities, and protection of its nuclear forces.”

“North Korea’s continued pursuit of nuclear weapons capabilities poses the most immediate and dire proliferation threat to international security and stability.”

“Iran’s development of increasingly long-range ballistic missile capabilities, and its aggressive strategy and activities to destabilize neighboring governments, raises questions about its long-term commitment to forgoing nuclear weapons capability.”

Given the mounting threat, DoD said, “Flexible and limited US nuclear response options can play an important role in restoring deterrence following limited adversary nuclear escalation.”

The updated document gives expanded attention to the role of intelligence in potential nuclear conflict including “knowledge of an adversary decision maker’s perceptions of benefits, costs, and consequences of restraint” and “information about adversary assets, capabilities, and vulnerabilities.” Intelligence is also needed for post-strike damage assessments.

Strategic messaging is key to deterring conflict, DoD said, though this often seems to involve the threat of force. “The ability to communicate US intent, resolve, and associated military capabilities in ways that are understood by adversary decision makers is vital. Direct military means include: forward presence, force projection, active and passive defense, strategic communications/messaging, and nuclear forces.”

DoD asserts that its system of nuclear command and control is “ready, reliable, and effective at meeting today’s strategic deterrence requirements. There are no gaps or seams that adversaries could exploit.” Maybe so.

“Possibly the greatest challenge confronting the joint force in a nuclear conflict is how to operate in a post-NUDET [nuclear detonation] radiological environment,” DoD said. “By design, nuclear weapons are highly destructive and have harmful effects that conventional weapons do not have. Commanders must plan for and implement protective measures to mitigate these effects and continue operations.”

Joint Nuclear Operations is not available in DoD’s online public library of Joint Publications. But a copy of the April 2020 document was released to the Federation of American Scientists last week under the Freedom of Information Act.

* * *

The Biden Administration adopted a somewhat conciliatory tone concerning nuclear weapons policy in its March 2021 Interim National Security Strategic Guidance:

“As we re-engage the international system, we will address the existential threat posed by nuclear weapons. We will head off costly arms races and re-establish our credibility as a leader in arms control. That is why we moved quickly to extend the New START Treaty with Russia. Where possible, we will also pursue new arms control arrangements. We will take steps to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, while ensuring our strategic deterrent remains safe, secure, and effective and that our extended deterrence commitments to our allies remain strong and credible.”

But even some simple changes from past practice remain to be accomplished. For now, at least, the Biden Administration is still adhering to the Trump policy of classifying the size of the US nuclear stockpile rather than following the Obama policy of disclosing it.

Army Program Seeks to Heighten Soldiers’ Cognition

A properly trained soldier can distinguish a vegetarian from a meat-eater based on their smell, a new Army publication says, since “different diets produce different human odors.”

He or she can to determine the age, gender and even the mental state of a target by studying their footprints.

Not simply a warrior, the ideal soldier is also an intelligence analyst, a cultural anthropologist, and a student of human nature with the ability to confront and overcome adversity — Sherlock Holmes and Leatherstocking and a bit of Tarzan, all in one.

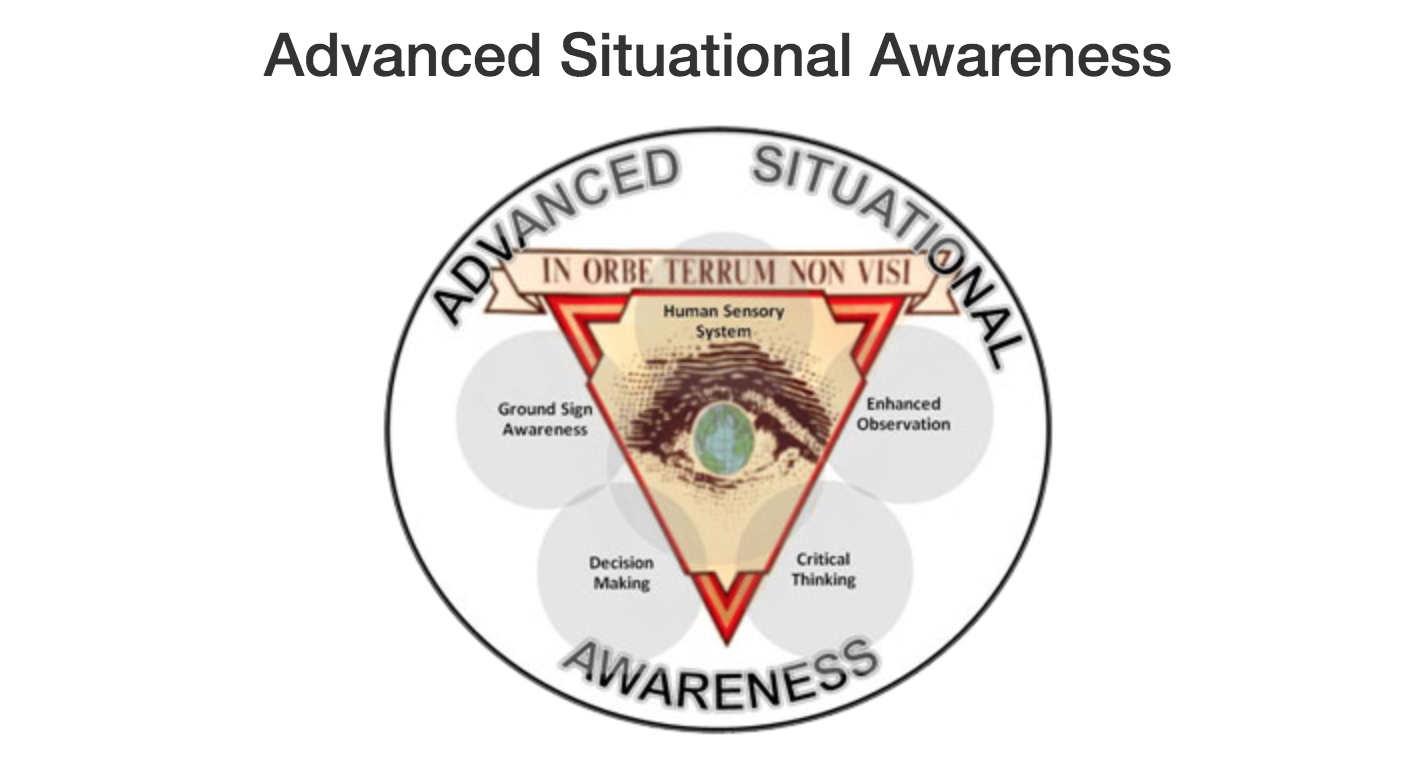

That, at any rate, seems to be the goal of the US Army’s Advanced Situational Awareness program, which trains soldiers to discern even subtle anomalies in the combat environment, to swiftly assess their implications, and to act decisively in response.

Advanced Situational Awareness “optimizes human performance through building the skills necessary to develop agile, resilient, adaptive, and innovative Soldiers who thrive in conditions of uncertainty and chaos.”

The program was described in Advanced Situational Awareness, US Army Training Circular TC 3-22.69, 316 pages, April 2021.

The Military Role in Combating COVID-19

There is a bewildering amount of official guidance on the role of the military in circumstances such as the current pandemic. But the practical impact of that guidance, whatever it may be, is unclear. Like the proverbial war plan that cannot survive first contact with the enemy, Pentagon doctrine on infectious disease seems to have been overtaken by events.

“The mission of DOD in a pandemic is to preserve U.S. combat capabilities and readiness and to support U.S. government efforts to save lives, reduce human suffering, and slow the spread of infection,” according to a 2019 Army manual.

To help accomplish that, another military manual offered a “prioritized and tiered [list of] infectious diseases [to] assist the military research community in focusing on the development of vaccine, prophylactic drugs, diagnostic capabilities, and surveillance efforts.”

Pandemic influenza was among the highest priority diseases, posing a “high operational risk,” but unfortunately the intended military research response appears to have lagged.

Who is in charge?

Well, “USNORTHCOM [US Northern Command] exercises coordinating authority for planning of DOD efforts in support of the USG response to pandemic influenza and infectious disease,” says a Pentagon publication (JP 3-40) on Joint Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction.

What is NORTHCOM doing?

“DoD has nearly 11,000 personnel dedicated to COVID-19 operations nation-wide, with nearly 2,500 in the New York City area,” according to an April 10 news release. “DOD is providing expeditionary medical care in several states across the country.”

“NORTHCOM is out there working furiously to carry out its many missions, implementing at least five different operations plans simultaneously,” according to military researcher William M. Arkin.

But “Implementing might be too strong of a word,” he wrote, “because even though these plans run in the hundreds of pages, most are thrown out the window almost as soon as they are taken off the shelf, useful in laying out how things should be organized but otherwise too rigid — or fanciful — to apply to the real world.”

In a new piece, Arkin surveyed 19 operational military plans that in theory govern NORTHCOM activities. Most of them are not publicly available, and some are classified.

“Is there any reason you can imagine that the pandemic response plan shouldn’t be public? Or the plan for Defense Support of Civil Authorities?” Arkin doesn’t think so.

One of the plans he turned up, a 2017 NORTHCOM draft on Pandemic Influenza and Infectious Disease Response, identified what it termed “critical vulnerabilities” including:

“Lack of communication and synchronization among partners and stakeholders, inability or unwillingness to share information / biosurveillance data, limited detection capabilities, and limited laboratory confirmatory testing.”

That particular plan from 2017 “seemingly never went beyond the draft stage,” said Arkin.

The Urgency of Military History

The task of the military historian differs from that of the academic historian because military history has an operational dimension. It is supposed to help inform current military operations with the lessons and the perspectives of the past.

“The historian must always bear in mind that the whole purpose of the history office is to help the warfighter by serving as an advisor and presenting critical documentation when needed,” according to a new US Air Force Handbook on the subject. “The mission drives what is important for the historian, not the historian’s particular interest. ”

The military historian also is responsible for identifying and assembling the raw materials of future scholarship. Contrary to what “many new historians may incorrectly assume, documentation will not automatically arrive in the office. The historian must seek it.” See Aerospace Historian Operations in Peace and War, Air Force Handbook 84-106, April 2, 2020.

But operationally, history can only do so much.

“Military history does not produce solutions for problems and does [not] guarantee success on the battlefield,” an Army manual on the subject explains. “An approach with these goals leads to frustration and biased or inaccurate history.”

“Rather, military history affords an understanding of the dynamics to shape the present and enables Soldiers the perspective of viewing current and future problems with ideas of how similar challenges were confronted in the past. . . If history rarely provides concrete answers, it offers insight and understanding.”

“Historians know that Army history records triumphs, challenges, and failures. Army historians do not judge operations and actions; they seek to tell the full story so that others learn from it.” See Military History Operations, ATP 1-20, US Army, June 2014.

Life Underground: US Army Subterranean Operations

Subterranean operations involving the use of tunnels and underground facilities pose growing challenges to the U.S. military, a new Army manual indicates.

“Today, over 10,000 known subterranean facilities exist around the world,” the manual says.

“Whether to protect vital assets and capabilities, mitigate weapon system and sensor overmatch, to strengthen a larger defensive position, or simply to be used for transportation in our largest cities, subterranean systems continue to be expanded and relied upon throughout the world. Therefore, our Soldiers and leaders must be prepared to fight and win in this environment.”

See Subterranean Operations, Army Techniques Publication ATP 3-21.51, November 2019.

Logistical issues aside, subterranean operations can have adverse effects on soldiers’ emotional, moral, and spiritual health, the Army manual said.

“Subterranean environments may reduce a Soldier’s sense of purpose and commitment, causing them to lose combat effectiveness sooner than anticipated due to the psychological and physiological stress of these environments.”

“As a result, Soldiers may have powerful emotional reactions. These may include an overwhelming sense of fear or momentary loss of their moral compass leading to illegal or immoral actions.”

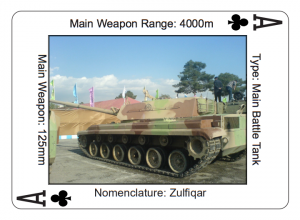

Army Playing Cards Feature Iranian Weapons

In a not very subtle sign of the times, the U.S. Army has produced a deck of playing cards featuring weaponry used or held by Iran in order to familiarize soldiers with Iran’s inventory of weapons and presumably to facilitate their recognition on the battlefield.

The Iran collection follows similar decks of playing cards illustrated with Chinese and Russian weapons.

Another set of U.S. Army playing cards featuring North Korean weapons systems is forthcoming.

DoD Doctrine on Nuclear Operations Published, Taken Offline

The Joint Chiefs of Staff briefly published and then removed from public access a new edition of their official doctrine on the use of nuclear weapons. But a public copy was preserved. See Joint Publication 3-72, Nuclear Operations, June 11, 2019.

The document presents an unclassified, mostly familiar overview of nuclear strategy, force structure, planning, targeting, command and control, and operations.

“Using nuclear weapons could create conditions for decisive results and the restoration of strategic stability,” according to one Strangelovian passage in the publication. “Specifically, the use of a nuclear weapon will fundamentally change the scope of a battle and create conditions that affect how commanders will prevail in conflict.”

The document might have gone unremarked, but after publishing it last week the Joint Chiefs deleted it from their public website. A notice there states that it (JP 3-72) is now only “available through JEL+” (the Joint Electronic Library), which is a restricted access site. A local copy remains publicly available on the FAS website.

USAF Seeks “Resilient” Nuclear Command and Control

The US Air Force last week updated its guidance on the command and control of nuclear weapons to include protection against electromagnetic pulse and cyber attack, among other changes. See Air Force Nuclear Command, Control, and Communications (NC3), Air Force Instruction 13-550, April 16, 2019.

“This is a complete revision to the previous version of this instruction,” the new guidance states. “It revises the command relationships, roles and responsibilities, the governance structure, and addresses resourcing, architecture and configuration management, resilience, and assessments.”

“Resilience” here pertains particularly to “two of the most broadly applied challenges: hardening against the effects of electromagnetic pulse and threats in the cyberspace domain.” These topics were scarcely mentioned at all in the previous version of the Air Force Instruction that was issued in 2014, nor did the term resilience appear in the earlier document.

Several new classified directives on nuclear command and control have been issued in recent years (such as Presidential Policy Directive-35 and others) and their content is reflected at least indirectly and in part in the new unclassified USAF guidance.

A broader modernization of the nation’s entire nuclear command, control and communications system is underway at U.S. Strategic Command, costing a projected $77 billion over the coming decade. See “STRATCOM to design blueprint for nuclear command, control and communications” by Sandra Erwin, Space News, March 29, 2019.

Contractors: All Major Military Operations Rely on Them

Military contractors are such an integral part of U.S. military forces that “most military operations will include contracted support,” a newly updated Pentagon manual explains.

In fact, “While some limited-duration operations, such as noncombatant evacuation operations, may use limited contracted support, all major operations will involve significant contracted support.”

Aside from their prominent role in logistics, contractors also provide linguist, signal and security services.

In some circumstances, contractors may even substitute for US military forces. “The use of contracted support as an alternative to deploying US forces may have other benefits, including minimizing the military footprint in the operational area, reducing force operational tempo, and improving domestic US political support or buy-in,” the manual said.

Contractors are considered indispensable, and they can sometimes be used to circumvent policy restrictions on military deployments. “The continual introduction of high-tech equipment, coupled with force structure and manning reductions, mission-specific force cap restrictions, and high operating tempo, means contracted support will augment military forces in most operations.”

Among the various types of military contractors are armed private security contractors (PSCs) that are used to guard personnel and facilities. “PSC-provided services, more than any other contracted service, can have a direct impact (sometimes a very negative impact) on civil-military aspects of the operation,” the Pentagon manual cautioned.

As a general matter, vigilant oversight is needed to ensure the integrity of the contracting process, since “the procurement of supplies and services in support of military operations can be prone to fraud, waste, and abuse (FWA), even more so in a foreign contingency where there are many contracts with local firms.” See Operational Contract Support, Joint Publication 4-10, March 4, 2019.

Military Deception: A Handbook

Military tacticians use deception to induce an opponent to act against his own interests, or to refrain from acting when it would be advantageous. The theory and techniques of military deception were detailed this week in a new Army publication for military planners that also implicitly illuminates the role of deception in other contexts.

In one form, deception may increase an adversary’s uncertainty so as to hinder decision-making. In another form, it may decrease uncertainty to encourage the adversary to make a decision that is mistaken.

“Ambiguity-increasing deception is designed to generate confusion and cause mental conflict in the enemy decision maker. Anticipated effects of ambiguity-increasing deception can include a delay to making a specific decision, operational paralysis, or the distribution of enemy forces to locations far away from the intended location of the friendly efforts,” the Army manual said.

Deceptive actions “can cause the target to delay a decision until it is too late to prevent friendly mission success. They can place the target in a dilemma for which no acceptable solution exists. They may even prevent the target from taking any action at all. This type of deception is typically successful with an indecisive decision maker who is known to avoid risk.”

On the other hand, “Ambiguity-decreasing deceptions manipulate and exploit an enemy decision maker’s pre-existing beliefs and bias through the intentional display of observables that reinforce and convince that decision maker that such pre-held beliefs are true. Ambiguity-decreasing deceptions cause the enemy decision maker to be especially certain and very wrong… Planners often have success using these deceptions with strong-minded decision makers who are willing to accept a higher level of risk.”

Even deception has limits and rules, according to the Army. For one thing, the U.S. military is not supposed to deliberately practice deception against the U.S. government or the public.

“Deception activities, including planning efforts, are prohibited from explicitly or implicitly targeting, misleading, or attempting to influence the U.S. Government, U.S. Congress, the U.S. public, or the U.S. news media. Legal staff review all deception activities to eliminate, minimize, or mitigate the possibility that such influence might occur.”

Nor, according to international convention, should instruments of negotiation be abused as tools of deception.

“Flags of truce must not be used surreptitiously to obtain military information or merely to obtain time to affect a retreat or secure reinforcements, or to feign a surrender in order to surprise an enemy.”

See Army Support to Military Deception, Field Manual 3-13.4, 26 February 2019.

By its nature, the effectiveness of military deception depends on secrecy. Specific applications of military deception are addressed in classified publications such as DoD Instruction S-3604.01. The latest (2017) version of Joint Publication 3-13.4 on Military Deception is restricted in distribution.

But the new Army manual is unclassified and was published without restriction.

Defense Primers, and More from CRS

“The President does not need the concurrence of either his military advisors or the U.S. Congress to order the launch of nuclear weapons,” the Congressional Research Service reminded readers last month in an updated “defense primer” on “Command and Control of Nuclear Forces.”

The CRS defense primer series consists of two-page introductions to a variety of basic military and intelligence topics. The primers do not generally present information that is altogether new to specialists, but they are a convenient way to increase national security literacy among non-specialist members of Congress and the public.

Recently updated items in the series include the following.

Defense Primer: Commanding U.S. Military Operations, CRS In Focus, updated December 20, 2018

Defense Primer: Intelligence Support to Military Operations, CRS In Focus, updated December 20, 2018

Defense Primer: U.S. Defense Industrial Base, CRS In Focus, updated December 20, 2018

Defense Primer: Procurement, CRS In Focus, updated December 20, 2018

Defense Primer: Information Operations, CRS In Focus, updated December 18, 2018

Defense Primer: Cyberspace Operations, CRS In Focus, updated December 18, 2018

Defense Primer: President’s Constitutional Authority with Regard to the Armed Forces, CRS In Focus, updated December 17, 2018

*

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

The Special Counsel Investigation After the Attorney General’s Resignation, CRS Legal Sidebar, January 2, 2019

Government Expenditures on Defense Research and Development by the United States and Other OECD Countries: Fact Sheet, updated December 19, 2018

Executive Branch Ethics and Financial Conflicts of Interest: Disclosure, CRS Legal Sidebar, January 2, 2019

DHS’s Cybersecurity Mission–An Overview, CRS In Focus, updated December 19, 2018

New U.S. Policy Regarding Nuclear Exports to China, CRS In Focus, December 17, 2018

Congress’s Authority to Influence and Control Executive Branch Agencies, updated December 19, 2018