Summer, Wrapped: The 2025 “State of the Heat”

Earlier this year, FAS sounded the alarm that federal reductions in force, funding pauses and freezes, program elimination, and other actions were stalling or setting back national preparedness for extreme heat – just as summer was kicking into gear. The areas we focused on included:

- Leadership and governance infrastructure

- Key personnel and their expertise

- Data, forecasts, and information availability

- Funding sources and programs for preparedness, risk mitigation and resilience

- Progress towards heat policy goals

With summer 2025 in the rearview mirror, we’re taking a look back to see how federal actions impacted heat preparedness and response on the ground, what’s still changing, and what the road ahead looks like for heat resilience. Consider this your 2025 State of the Heat.

2025 State of the Heat

The State of Summer: How Hot Was It and How Did Communities Cope?

Summer didn’t feel as sweltering this year as it has the past couple of years. That’s objectively true – but only because the summers of 2023 and 2024 were true scorchers.

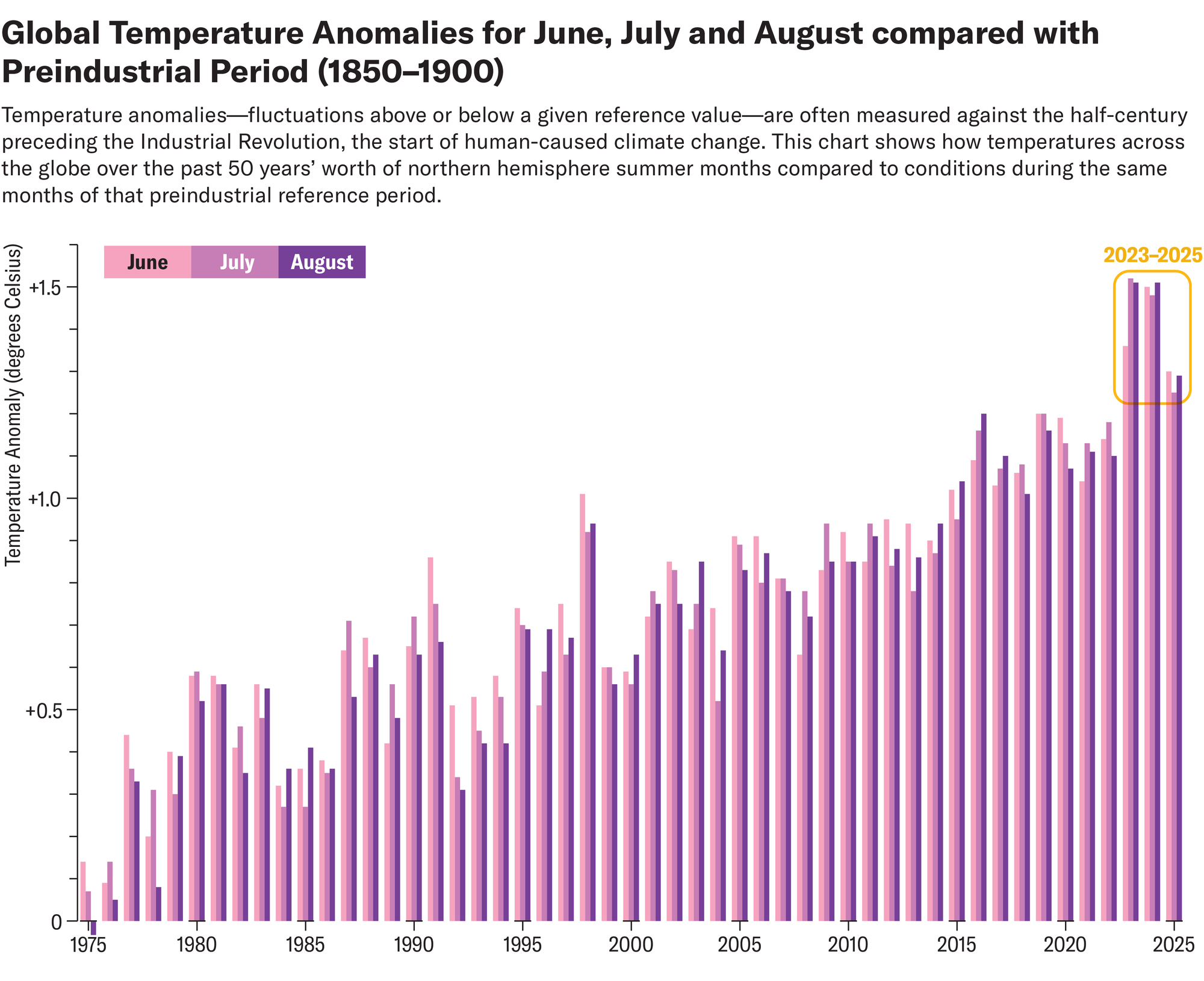

Summer 2025 was cooler than the past two summers, but still the third-hottest on record. Credit: Amanda Montañez in Scientific American; Source: Copernicus Climate Change Service (data)

Summer 2025 was still the third-hottest on record. High temperature records were shattered across the country. Eight states broke their all-time heat records for June, and in July almost the entire country – including Alaska – saw above-average temperatures. Temperature extremes continued into September. Places like the San Francisco Bay Area experienced their hottest temperatures of the year even as the season turned to autumn. In addition, humidity was a particularly potent threat. One hundred twenty million people experienced near-record humidity this summer alongside temperature extremes. Humidity and heat are a deadly combination because sweating is less effective when humidity is high, raising the risk of overheating and experiencing heat-related illness. This heat led to spikes in heat-related illnesses and hospitalizations, longer droughts, road buckling and damage, and even a federal energy emergency in June 2025.

Since January 2025, and continuing over the course of the summer, FAS’s Climate and Health team has been in regular touch with local and state government officials involved in heat preparedness, response, and resilience. These officials generally shared that heat management activities continued successfully in most places throughout the summer despite disruptions to federal funding and programs. Officials emphasized three specific developments that helped enable that continuity:

- Tools like the National Weather Service’s HeatRisk tool remained functional. HeatRisk is a critical tool for subnational governments to understand risks, inform and coordinate partners, and design thresholds for emergency response alerts and actions. Further, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Heat and Health Tracker, which monitors heat-related visits in emergency departments across the country, was brought back online following reversals in CDC reductions in force.

- Some key sources of federal funds, like American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding, remained available. Many local governments – particularly in places without large emergency management programs and Hazard Mitigation Assistance Program (HMGP) funds – have used ARPA funding to support heat response.

- Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) funding was released after considerable advocacy from the external community and members of Congress. This funding is critical to support home energy assistance for cooling bills.

Yet this continuity is fragile:

- The future of the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) and the CDC’s Climate and Health program remains uncertain and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and CDC have faced notable staffing cuts and could face more cuts, jeopardizing the maintenance and existence of tools like HeatRisk and the Heat and Health Tracker.

- Officials are also concerned about their ability to keep robust heat response programs going in a more austere funding landscape. For example, ARPA funding must be spent by December 31, 2026, and many officials are expecting a steep funding cliff that could lead to cuts to heat-related programs. We are already seeing evidence of this in Miami-Dade County, which eliminated its Chief Heat Officer position as a part of an effort to close a $400 million funding gap that emerged in part as ARPA funds were exhausted. Additional cuts to, and restrictions on, federal health preparedness programs and emergency management programs will also impact the staffing capacity of state and local governments. For example, one of the state officials FAS was working with on heat lost their job because of state budget shortfalls, and others have worried about their future job security.

- Finally, while the LIHEAP program is currently intact, and has bipartisan support in Congress, it could be undermined by Executive Branch pocket rescissions and reductions in force.

The State of Federal Heat Governance: What Changed?

The federal heat landscape continues to be highly dynamic. While extreme heat is no longer a stated priority of the federal government, both this Administration and Congress have acknowledged heat’s risks. Against this backdrop, federal agencies are advancing a mixed bag of heat-related policies. For example:

- The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) continues to pursue a heat rule. This rule, which was initiated under the Biden Administration and is a top priority for worker advocates, was included on the Trump Administration’s Unified Agenda as a regulation in development. However, given comments made at summer hearings on this rule, recent reporting has hypothesized that OSHA may model the rule after Nevada’s newer and weaker “performance-based” standards. This rule includes no “trigger temperatures” above which certain protections are required. An evaluation of the Nevada rule’s effectiveness will be limited by cuts to the staff at the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and less funding for NIOSH’s research.

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommits to research on extreme heat and health. The NIH’s Climate Change and Health (CCH) Initiative was reintroduced as the Program on Health and Extreme Weather (HEW). The HEW Program’s strategic framework eliminates language directly referencing climate change and greenhouse gases and aligns with the Department of Health and Human Services’ broader MAHA strategy. As both houses of Congress rejected cuts to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), there could be funding available through NIEHS for studies on the outcomes of heat exposure, long-term health risks, and preventative measures.

- The Government Accountability Office (GAO) says the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) needs to evaluate its role in addressing extreme heat. A recent GAO report recommended that FEMA improve its benefit-cost analysis for heat, identify heat mitigation projects it might fund, and evaluate its role in heat response – all recommendations from FAS’s 2025 Heat Policy Agenda. FEMA agreed to act partially on the recommendations, citing changes made to HMGP to make extreme heat projects ineligible for standalone funding as a barrier to full action.

- The Department of Energy acknowledges heatwaves as a particular risk. In July, the Department of Energy published a report entitled A Critical Review of the Science of Climate Change. This report has been widely discredited for cherry-picking and misrepresenting scientific studies. However, it is notable that even as the report minimizes the risks of greenhouse gas emissions, it emphasizes the importance of taking action on extreme heat, stating that “heatwaves have important effects on society that must be addressed” and that “inability to afford energy leaves low-income households exposed to weather extremes”. While there are partisan disagreements on how to secure that affordable energy, the report demonstrates that heat risk is an area of consensus between the parties that merits further pursuit.

- The ongoing government shutdown could be used by the Trump Administration to continue their mass firing of federal workers. With the status of Appropriations negotiations stalled, the Office of Management and Budget has asked agencies to prepare contingency plans, and has threatened mass layoffs of furloughed employees. Given that most heat-related activities are not statutorily authorized, this could lead to further cuts to the federal heat workforce. On Friday October 10th, hundreds of workers were laid off across Health and Human Services, including at the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics and the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response.

Congressional actions are also shaping what’s possible for nationwide heat preparedness. To start, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) cut funding necessary to mitigate extreme heat’s impacts as well as respond to the negative health consequences of heat. Impacts include:

Beyond OBBBA, Congressional appropriations proposals for Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 represent a mixed bag for federal heat policy. The House and the Senate proposals diverge in key ways, and will need to be rectified. Some of the things we are tracking include:

State of the Future: What Comes Next for Heat Policy

Looking ahead, it is essential that the federal government maintains its role as a data collector, steward, and analyst, supports heat-related research and development, supports social services for the most vulnerable American households facing extreme heat. and continues to make investments in state, local, territorial, and tribal (SLTT) governments and their heat mitigation infrastructure and preparedness capacity. At the same time, SLTT governments are rapidly innovating in heat policy, and will be sites of innovation to watch this next year. Our team is tracking promising signs in three key areas:

- More places are standing up heat governance infrastructure. A growing number of state, regional, and local plans acknowledge extreme heat as a risk; at the same time, more and more communities are developing standalone heat preparedness, response, or action plans (see heatplans.org to learn more, and read our “Framework for a Heat Ready Nation” to learn about progress in the Sunbelt region). New heat plans that launched in 2025 include Lincoln-Lancaster Heat Response Plan, the Low Country Heat Action Plan Toolkit, Orange County, NC’s Heat Action Plan, and King County’s Extreme Heat Mitigation Strategy. Many more plans are in the development pipeline. Further, more networks of local governments, including the Ten Across Network and Climate Mayors, are making heat technical assistance a priority.

- More places are expanding their extreme heat protections. Policies that protect people from extreme heat exposure inside of their homes, inside of schools, and at the workplace are also starting to see uptake. LA County set an indoor temperature maximum of 82°F for rental units, creating a legal right to cooling for tenants. Meanwhile, the state of California recently enacted a law that all homes should be able to attain and maintain safe indoor temperatures, without specifying that limit. New Jersey now restricts utilities from shutting off the power due to non-payment from June 15 through August 31; New Jersey is also providing direct utility relief to New Jersey ratepayers. New York State became the first state in the country to regulate extreme heat in schools, setting a maximum temperature threshold of 88F for safe school operations. Finally, in Boston and in New Orleans, ordinances passed that require basic protections from heat, like rest breaks, for all city workers and city contractors. Scaling up these policies that minimize heat overexposure will be critical to be ready for hotter heat seasons to come.

- Regional networks are forming to advance evidence-based public health measures. In light of rollbacks to public health infrastructure at the federal level, two regional networks have formed to coordinate across state public health departments, the West Coast Health Alliance and the Northeast Public Health Collaborative. While the initial focus is on developing evidence-based recommendations on vaccines and combining forces on vaccine procurement for their populations, we will be tracking how these networks address other public health efforts under threat, such as the health risks of extreme heat.

Protecting Americans from extreme heat will require a multiplicity of leadership across the levels of government in the United States and the capacity to connect hundreds of diverse organizations and experts around a shared solution set. To meet this moment, FAS will develop the 2026 State & Local Heat Policy Agenda, a blueprint for polycentric action towards a Heat Ready Nation. The 2026 Heat Policy Agenda will align the growing heat community around a shared set of objectives and equip state and local decision makers with the strategies they can deploy for heat season 2026 and beyond. We are focused on strategies that (1) build government capacity to address the threat of extreme heat and (2) ensure every American can be safe from heat in their homes, in their workplaces, and in their communities.

Over the next couple of months, the FAS team will be documenting the policy levers available at the state and local levels to address extreme heat and crafting model guidance, model executive orders, model legislation, and financing models. Want to be a part of this effort? Reach out to Grace Wickerson at gwickerson@fas.org if you want to contribute by:

- Identifying promising extreme heat policies as well as evidence for their effectiveness.

- Offering your expertise on potential heat-related policy interventions.

- Sharing about heat-related advocacy efforts and potential technical assistance needs.

- Raising your hand as an extreme heat champion inside of state or local government.

Report Outlines Urgent, Decisive Action on Extreme Heat

‘Framework for a Heat-Ready Nation’ puts heat emergencies on the same footing as other natural disasters, reimagines how governments respond

Washington, D.C. – July 22, 2025 – Shattered heat records, heat domes, and prolonged heat waves cause thousands of deaths and hundreds of billions of dollars in lost productivity, damages, and economic disruptions. In 2023 alone, at least 2,300 people died from extreme heat, and true mortality could be greater than 10,000 annually. Workplaces are seeing $100 billion in lost productivity each year. Increased wear and tear on aging roads, bridges, and rail is increasing maintenance costs, with road maintenance costs expected to balloon to $26 billion annually by 2040. Extreme heat also puts roughly two-thirds of the country at risk of a blackout.

Extreme heat events that were uncommon in many places are becoming routine and longer lasting – and communities across the United States remain highly vulnerable.

To help prepare, the Federation of American Scientists has drawn upon experts from Sunbelt states to identify decisive actions to save lives during extreme heat events and prepare for longer heat seasons. The Framework for a Heat-Ready Nation, released today, calls for local, state, territory, Tribal, and federal governments to collaborate with community organizations, private sector partners and research institutions.

“The cost of inaction is not merely economic; it is measured in preventable illness, deaths and diminished livelihoods,” the report authors say. “Governments can no longer afford to treat extreme heat as business as usual or a peripheral concern.”

The Framework for a Heat-Ready Nation focuses on five measures to protect people, their livelihoods, and their communities:

- Establish leaders with responsibility and authority to address extreme heat. Leaders must coordinate actions across all relevant agencies and with non-governmental partners.

- Accurately assess extreme heat and its impacts in real time. Use the data to inform thresholds that trigger emergency response protocols, safeguards, and pathways to financial assistance.

- Prepare for extreme heat as an acute emergency as well as a chronic risk. Local governments should consider developing heat-response plans and integrating extreme temperatures into their long-term capital planning and resilience planning.

- When extreme heat thresholds are crossed, local, state, territory, Tribal and federal governments should activate response plans and consider emergency declarations. There should be a transparent and widely understood process for emergency responses to extreme heat that focus on protecting lives and livelihoods and safeguarding critical infrastructure.

- Develop strategies to plan for and finance long-term extreme heat impact reduction. Subnational governments can incentivize or require risk-reduction measures like heat-smart building codes and land-use planning, and state, territory, Tribal and federal governments can dedicate funding to support local investments in long-term preparedness.

Extreme heat in the Sunbelt region of the United States is a harbinger of what’s coming for the rest of the country. But the Sunbelt is also advancing solutions. In April 2025, representatives from states, cities, and regions across the U.S. Interstate 10 corridor from California to Florida, convened in Jacksonville, Florida for the Ten Across Sunbelt Cities Extreme Heat Exercise. Attendees worked to understand the available levers for government heat response, discussed their current efforts on extreme heat, and identified gaps that hinder both immediate response and long-term planning for future extreme heat events.

Through an analysis of efforts to date in the Sunbelt, gaps in capabilities, and identified opportunities, and analysis of previous calls to action around extreme heat, the Federation of American Scientists developed the Framework for a Heat-Ready Nation.

The report was produced with technical support from the Ten Across initiative associated with Arizona State University, and funding from the Natural Resources Defense Council.

###

About FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address national challenges. More information about FAS work at fas.org.

It’s Summer, America’s Heating Up, and We’re Even More Unprepared

Summer officially kicked off this past weekend with the onset of a sweltering heat wave. As we hit publish on this piece, tens of millions of Americans across the central and eastern United States are experiencing sweltering temperatures that make it dangerous to work, play, or just hang out outdoors.

The good news is that even when the mercury climbs, heat illness, injury, and death are preventable. The bad news is that over the past five months, the Trump administration has dismantled essential preventative capabilities.

At the beginning of this year, more than 70 organizations rallied around a common-sense Heat Policy Agenda to tackle this growing whole-of-nation crisis. Since then, we’ve seen some encouraging progress. The new Congressional Extreme Heat Caucus presents an avenue for bipartisan progress on securing resources and legislative wins. Recommendations from the Heat Policy Agenda have already been echoed in multiple introduced bills. Four states, California, Arizona, New Jersey, and New York, now have whole-of-government heat action plans, and there are several States with plans in development. More locally, mayors are banding together to identify heat preparedness, management, and resilience solutions. FAS highlighted examples of how leaders and communities across the country are beating the heat in a Congressional briefing just last week.

But these steps in the right direction are being forestalled by the Trump Administration’s leap backwards on heat. The Heat Policy Agenda emphasized the importance of a clear, sustained federal governance structure for heat, named authorities and dedicated resourcing for federal agencies responsible for extreme heat management, and funding and technical assistance to subnational governments to build their heat readiness. The Trump Administration has not only failed to advance these goals – it has taken actions that clearly work against them.

The result? It’s summer, America’s heating up, and we’re deeply unprepared.

The heat wave making headlines today is just the latest example of how extreme heat is a growing problem for all 50 states. In just the past month, the Pacific Northwest smashed early-summer temperature records, there were days when parts of Texas were the hottest places on Earth, and Alaska – yes, Alaska – issued its first-ever heat advisory. Extreme heat is deadlier than hurricanes, floods, and tornadoes combined, and is exacerbating a mental-health crisis as well. By FAS’ estimates, extreme heat costs the nation more than $162 billion annually, costs that have made extreme heat a growing concern to private markets.

To build a common understanding of the state of federal heat infrastructure, we analyzed the status of heat-critical programs and agencies through public media, government reports, and conversations with stakeholders. All known impacts are confirmed via publicly available sources. We highlight five areas where federal capacity has been impacted:

- Leadership and governance infrastructure

- Key personnel and their expertise

- Data, forecasts, and information availability

- Funding sources and programs for preparedness, risk mitigation and resilience

- Progress towards heat policy goals

This work provides answers to many of the questions our team has been asked over the last few months about what heat work continues at the federal level. With this grounding, we close with some options and opportunities for subnational governments to consider heading into Summer 2025.

What is the Current State of Federal Capacity on Extreme Heat?

Loss of leadership and governance infrastructure

At the time of publication, all but one of the co-chairs for the National Integrated Heat Health Information System’s (NIHHIS) Interagency Working Group (IWG) have either taken an early retirement offer or have been impacted by reductions in force. The co-chairs represented NIHHIS, the National Weather Service (NWS), Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The National Heat Strategy, a whole-of-government vision for heat governance crafted by 28 agencies through the NIHHIS IWG, was also taken offline. A set of agency-by-agency tasks for Strategy implementation (to build short-term readiness for upcoming heat seasons, as well as to strengthen long-term preparedness) was in development as of early 2025, but this work has stalled. There was also a goal to formalize NIHHIS via legislation, given that its existence is not mandated by law – relevant legislation has been introduced but its path forward is unclear. Staff remain at NIHHIS and are continuing the work to manage the heat.gov website, craft heat resources and information, and disseminate public communications like Heat Beat Newsletter and Heat Safety Week. Their positions could be eliminated if proposed budget cuts to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are approved by Congress.

Staffing reductions and actualized or proposed changes to FEMA and HHS, the federal disaster management agencies implicated in addressing extreme heat, are likely to be consequential in relation to extreme heat this summer. Internal reports have found that FEMA is not ready for responding to even well-recognized disasters like hurricanes, increasing the risk for a mismanaged response to an unprecedented heat disaster. The loss of key leaders at FEMA has also put a pause to efforts to integrate extreme heat within agency functions, such as efforts to make extreme heat an eligible disaster. FEMA is also proposing changes that will make it more difficult to receive federal disaster assistance. The Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), HHS’ response arm, has been folded into the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which has been refocused to focus solely on infectious diseases. There is still little public information for what this merger means for HHS’ implementation of the Public Health Service Act, which requires an all-hazards approach to public health emergency management. Prior to January 2025, HHS was determining how it could use the Public Health Emergency authority to respond to extreme heat.

Loss of key personnel and their expertise

Many key agencies involved in NIHHIS, and extreme heat management more broadly, have been impacted by reductions in force and early retirements, including NOAA, FEMA, HHS, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), and the Department of Energy (DOE). Some key agencies, like FEMA, have lost or will lose almost 2,000 staff. As more statutory responsibilities are put on fewer workers, efforts to advance “beyond scope” activities, like taking action on extreme heat, will likely be on the back burner.

Downsizing at HHS has been acutely devastating to extreme heat work. In January, the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity (OCCHE) was eliminated, putting a pause on HHS-wide coordination on extreme heat and the new Extreme Heat Working Group. In April, the entire staff of the Climate and Health program at CDC, the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), and all of the staff at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) working on extreme heat, received reduction in force notices. While it appears that staff are returning to the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health, they have lost months of time that could have been spent on preparedness, tool development, and technical assistance to local and state public health departments. Sustained funding for extreme heat programs at HHS is under threat, the FY2026 budget for HHS formally eliminates the CDC’s Climate and Health Program, all NIOSH efforts on extreme heat, and LIHEAP.

Risks to data, forecasts, and information availability, though some key tools remain online

Staff reductions at NWS have compromised local forecasts and warnings, and some offices can no longer staff around-the-clock surveillance. Staff reductions have also compromised weather balloon launches, which collect key temperature data for making heat forecasts. Remaining staff at the NWS are handling an increased workload at one of the busiest times of the year for weather forecasting. Reductions in force, while now reversed, have impacted real-time heat-health surveillance at the CDC, where daily heat-related illness counts have been on pause since May 21, 2025 and the site is not currently being maintained as of the date of this publication.

Some tools remain online and available to use this summer, including NWS/CDC’s HeatRisk (a 7-day forecast of health-informed heat risks) and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Heat-Related EMS Activation Surveillance Dashboard (which shows the number of heat-related EMS activations, time to patient, percent transported to medical facilities, and deaths). Most of the staff that built HeatRisk have been impacted by reductions in force. The return of staff to the CDC’s Climate and Health program is a bright spot, and could bode well for the tool’s ongoing operations and maintenance for Summer 2025.

Proposed cuts in the FY26 budget will continue to compromise heat forecasting and data. The budget proposes cutting budgets for upkeep of NOAA satellites crucial to tracking extreme weather events like extreme heat; cutting budgets for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s LandSat program, which is used widely by researchers and private sector companies to analyze surface temperatures and understand heat’s risks; and fully defunding the National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network, which funds local and state public health departments to collect heat-health illness and death data and federal staff to analyze it.

Rollbacks in key funding sources and programs for preparedness, risk mitigation and resilience

As of May 2025, both NIHHIS Centers of Excellence – the Center for Heat Resilient Communities and the Center for Collaborative Heat Monitoring – received stop work orders and total pauses in federal funding. These Centers were set to work with 26 communities across the country to either collect vital data on local heat patterns and potential risks or shape local governance to comprehensively address the threat of extreme heat. These communities represented a cross-cut of the United States, from urban to coastal to rural to agricultural to tribal. Both Center’s leadership plans to continue the work with the selected communities in a reduced capacity, and continue to work towards aspirational goals like a universal heat action plan. Future research, coordination, and technical assistance at NOAA on extreme heat is under fire with the proposed total elimination of NOAA Research in the FY26 budget.

At FEMA, a key source of funding for local heat resilience projects, the Building Resilience Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program, has been cancelled. BRIC was the only FEMA Resilience grant that explicitly called out extreme heat in its Notice of Funding Opportunity, and funded $13 million in projects to mitigate the impacts of extreme heat. Many states have also faced difficulties in getting paid by FEMA for grants that support their emergency management divisions, and the FY26 budget proposes cuts to these grant programs. The cancellation of Americorps further reduces capacity for disaster response. FEMA is also dropping its support for improving building codes that mitigate disaster risk as well as removing requirements for subnational governments to plan for climate change.

At HHS, a lack of staff at CDC has stalled payments from key programs to prepare communities for extreme heat, the Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) grant program and the Public Health Preparedness and Response program. BRACE is critical federal funding for state and local climate and health offices. In states like North Carolina, the BRACE program funds live-saving efforts like heat-health alerts. Both of these programs are proposed to be totally eliminated in the FY26 budget. The Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) is also slated for elimination, despite being the sole source of federal funding for health care system readiness. HPP funds coalitions of health systems and public health departments, which have quickly responded to heat disasters like the 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Domes and established comprehensive plans for future emergencies. The National Institutes of Health’s Climate and Health Initiative was eliminated and multiple grants paused in March 2025. Research on extreme weather and health may proceed, according to new agency guidelines, yet overall cuts to the NIH will impact capacity to fund new studies and new research avenues. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, which funds research on environmental health, faces a 36% reduction in its budget, from $994 million to $646 million.

Access to cool spaces is key to preventing heat-illness and death. Yet cuts, regulatory rollbacks, and program eliminations across the federal government are preventing progress towards ensuring every American can afford their energy bills. At DOE, rollbacks in energy efficiency standards for cooling equipment and the ending of the EnergyStar program will impact the costs of cooling for consumers. Thankfully, DOE’s Home Energy Rebates survived the initial funding freezes and the funding has been deployed to states to support home upgrades like heat pumps, insulation, air sealing, and mechanical ventilation. At HUD, the Green and Resilient Retrofits Program has been paused as of March 2025, which was set to fund important upgrades to affordable housing units that would have decreased the costs of cooling for vulnerable residents. At EPA, widespread pauses and cancellations in Inflation Reduction Act programs have put projects to provide more affordable cooling solutions on pause. At the U.S. Department of Agriculture, all grantees for the Rural Energy for America Program, which funds projects that provide reliable and affordable energy in rural communities, have been asked to resubmit their grants to receive allocated funding. These delays put rural community members at risk of extreme heat this summer, where they face particular risks due to their unique health and sociodemographic vulnerabilities. Finally, while the remaining $400 million in LIHEAP funding was released for this year, it faces elimination in FY26 appropriations. If this money is lost, people will very likely die and utilities will not be able to cover the costs of unpaid bills and delay improvements to the grid infrastructure to increase reliability.

Uncertain progress towards heat policy goals

Momentum towards establishing a federal heat stress rule as quickly as possible has stalled. The regulatory process for the Heat Injury and Illness Prevention in Outdoor and Indoor Work Settings is proceeding, with hearings that began June 16 and are scheduled to continue until July 3. It remains to be seen how the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) will proceed with the existing rule as written. OSHA’s National Emphasis Program (NEP) for Heat will continue until April 6, 2026. This program focuses on identifying and addressing heat-related injuries and illnesses in workplaces, and educating employers on how they can reduce these impacts on the job. To date, NEP has conducted nearly 7,000 inspections connected to heat risks, which lead to 60 heat citations and nearly 1,400 “hazard alert” letters being sent to employers.

How Can Subnational Governments Ready for this Upcoming Heat Season?

Downscaled federal capacity comes at a time when many states are facing budget shortfalls compounded by federal funding cuts and rescissions. The American Rescue Plan Act, the COVID-19 stimulus package, has been a crucial source of revenue for many local and state governments that enabled expansion in services, like extreme heat response. That funding must be spent by December 2026, and many subnational governments are facing funding cliffs of millions of dollars that could result in the elimination of these programs. While there is a growing attention to heat, it is still often deprioritized in favor of work on hazards that damage property.

Even in this environment, local and state governments can still make progress on addressing extreme heat’s impacts and saving lives. Subnational governments can:

- Conduct a data audit to ensure they are tracking the impacts of extreme heat, like emergency medical services activations, emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and deaths, and tracking expenditures dedicated to any heat-related activity.

- Develop a heat preparedness and response plan, to better understand how to leverage existing resources, capacities, and partnerships to address extreme heat. This includes understanding emergency authorities available at the local and state level that could be leveraged in a crisis.

- Use their platforms to educate the public about extreme heat and share common-sense strategies that reduce the risk of heat-illness, and public health departments can target communications to the most vulnerable.

- Ensure existing capital planning and planned infrastructure build-outs prioritize resilience to extreme heat and set up cooling standards for new and existing housing and for renters. Subnational governments can also leverage strategies that reduce their fiscal risk, such as implementing heat safety practices for their own workforces and encouraging or requiring employers to deploy these practices as a way to reduce workers compensation claims.

FAS stands ready to support leaders and communities in implementing smart, evidence-based strategies to build heat readiness – and to help interested parties understand more about the impacts of the Trump administration’s actions on federal heat capabilities. Contact Grace Wickerson (gwickerson@fas.org) with inquiries.

Position On H.Res.446 – Recognizing “National Extreme Heat Awareness Week”

The Federation of American Scientists supports H.Res. 446, which would recognize July 3rd through July 10th as “National Extreme Heat Awareness Week”.

The resolution is timely, as the majority of heat-related illness and death in the United States occurs from May to September. If enacted, H.Res. 446 would raise awareness about the dangers of extreme heat, enabling individuals and communities to take action to better protect themselves this year and for years to come.

“Extreme heat is one of the leading causes of weather-related mortality and a growing economic risk,” said Grace Wickerson, Senior Manager for Climate and Health at the Federation of American Scientists. “We applaud Rep. Lawler and Rep. Stanton’s efforts to raise awareness of the threat of extreme heat with this resolution and the launch of the new Extreme Heat Caucus.”

Position On H.R.3738 – Heat Management Assistance Grant Act of 2025

The Federation of American Scientists supports H.R. 3738 of the 119th Congress, titled the “Heat Management Assistance Grant Act of 2025.”

The Heat Management Assistance Grant Act of 2025 creates the Heat Management Assistance Grant (HMAG) Program, a quick release of Federal Emergency Management Agency grants to state, local, tribal, and territorial governments for managing heat events that could become major disasters. This resourcing can be used for responses to extreme heat events, including supplies, personnel, and public assistance. HMAG is modeled after the Fire Management Assistance Grant program, which similarly deploys quick funding to activities that prevent wildfires from becoming major disaster events. The bill also creates a definition for an extreme heat event, which informs subnational leaders on when they can ask for assistance.

“Heat emergencies, such as the 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Dome and 2024 power outage following Hurricane Beryl in Texas, demonstrate a critical need for government assistance for heat-affected communities. Yet to date, there has been no federal pathway for rapidly resourcing heat response,” said Grace Wickerson, Senior Manager for Climate and Health at the Federation of American Scientists. “The Heat Management Assistance Grant Act of 2025 is a critical step in the right direction to unlock the resources needed to save lives, and aligns with key recommendations from our 2025 Heat Policy Agenda.”

Position On The Heating and Cooling Relief Act of 2025

The Federation of American Scientists supports The Heating and Cooling Relief Act of 2025. With summer right around the corner, it is more important than ever to ensure life-saving home cooling is affordable to all Americans.

The Heating and Cooling Relief Act of 2025 helps mitigate the negative health impacts of extreme heat through necessary modernizations of the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP). The bill includes key provisions of the 2025 Heat Policy Agenda, including ensuring LIHEAP is reauthorized at a level to meet the demand from all eligible households, expanding emergency assistance authorities and funding to cover heating and cooling support during extreme temperature events, preventing energy shutoffs for LIHEAP beneficiaries, increasing the share of funding that can go towards preventative weatherization measures, and requiring the following studies:

- A study on safe residential temperature standards for federally assisted housing in consultation with the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and strategies to keep housing within safe temperature ranges.

- A study from State Energy Offices that receive federal funds on pathways to retrofit the low-income housing stock to ensure it is adapted to rising temperatures, such as through efficient cooling systems and passive cooling.

“Access to affordable energy is crucial for health security, especially during extreme temperatures. Yet 1 in 6 households can’t afford their energy bills, and the costs of heating and cooling homes are continuing to climb,” says Grace Wickerson, Senior Manager, Climate and Health. “The Federation of American Scientists is proud to support the Heating and Cooling Relief Act of 2025 bill to bring down the cost of energy for Americans through immediate relief as well as forward-thinking investments in resilience.”

2025 Heat Policy Agenda

It’s official: 2024 was the hottest year on record. But Americans don’t need official statements to tell them what they already know: our country is heating up, and we’re deeply unprepared.

Extreme heat has become a national economic crisis: lowering productivity, shrinking business revenue, destroying crops, and pushing power grids to the brink. The impacts of extreme heat cost our Nation an estimated $162 billion in 2024 – equivalent to nearly 1% of the U.S. GDP.

Extreme heat is also taking a human toll. Heat kills more Americans every year than hurricanes, floods, and tornadoes combined. The number of heat-related illnesses is even higher. And even when heat doesn’t kill, it severely compromises quality of life. This past summer saw days when more than 100 million Americans were under a heat advisory. That means that there were days when it was too hot for a third of our country to safely work or play.

We have to do better. And we can.

Attached is a comprehensive 2025 Heat Policy Agenda for the Trump Administration and 119th Congress to better prepare for, manage, and respond to extreme heat. The Agenda represents insights from hundreds of experts and community leaders. If implemented, it will build readiness for the 2025 heat season – while laying the foundation for a more heat-resilient nation.

Core recommendations in the Agenda include the following:

- Establish a clear, sustained federal governance structure for extreme heat. This will involve elevating, empowering, and dedicating funds to the National Interagency Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS), establishing a National Heat Executive Council, and designating a National Heat Coordinator in the White House.

- Amend the Stafford Act to explicitly define extreme heat as a “major disaster”, and expand the definition of damages to include non-infrastructure impacts.

- Direct the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to consider declaring a Public Health Emergency in the event of exceptional, life-threatening heat waves, and fully fund critical HHS emergency-response programs and resilient healthcare infrastructure.

- Direct the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to include extreme heat as a core component of national preparedness capabilities and provide guidance on how extreme heat events or compounding hazards could qualify as major disasters.

- Finalize a strong rule to prevent heat injury and illness in the workplace, and establish Centers of Excellence to protect troops, transportation workers, farmworkers, and other essential personnel from extreme heat.

- Retain and expand home energy rebates, tax credits, LIHEAP, and the Weatherization Assistance Program, to enable deep retrofits that cut the costs of cooling for all Americans and prepare homes and other infrastructure against threats like power outages.

- Transform the built and landscaped environment through strategic investments in urban forestry and green infrastructure to cool communities, transportation systems to secure safe movement of people and goods, and power infrastructure to ready for greater load demand.

The way to prevent deaths and losses from extreme heat is to act before heat hits. Our 60+ organizations, representing labor, industry, health, housing, environmental, academic and community associations and organizations, urge President Trump and Congressional leaders to work quickly and decisively throughout the new Administration and 119th Congress to combat the growing heat threat. America is counting on you.

Executive Branch

Federal agencies can do a great deal to combat extreme heat under existing budgets and authorities. By quickly integrating the actions below into an Executive Order or similar directive, the President could meaningfully improve preparedness for the 2025 heat season while laying the foundation for a more heat-resilient nation in the long term.

Streamline and improve extreme heat management.

More than thirty federal agencies and offices share responsibility for acting on extreme heat. A better structure is needed for the federal government to seamlessly manage and build resilience. To streamline and improve the federal extreme heat response, the President must:

- Establish the National Integrated Heat-Health Information System (NIHHIS) Interagency Committee (IC). The IC will elevate the existing NIHHIS Interagency Working Group and empower it to shape and structure multi-agency heat initiatives under current authorities.

- Establish a National Heat Executive Council comprising representatives from relevant stakeholder groups (state and local governments, health associations, infrastructure professionals, academic experts, community organizations, technologists, industry, national laboratories, etc.) to inform the NIHHIS IC.

- Appoint a National Heat Coordinator (NHC). The NHC would sit in the Executive Office of the President and be responsible for achieving national heat preparedness and resilience. To be most effective, the NHC should:

- Work closely with the IC to create goals for heat preparedness and resilience in accordance with the National Heat Strategy, set targets, and annually track progress toward implementation.

- Each spring, deliver a National Heat Action Plan and National Heat Outlook briefing, modeled on the National Hurricane Outlook briefing, detailing how the federal government is preparing for forecasted extreme heat.

- Find areas of alignment with efforts to address other extreme weather threats.

- Direct the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the National Guard Bureau, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to create an incident command system for extreme heat emergencies, modeled on the National Hurricane Program.

- Direct the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to review agency budgets for extreme heat activities and propose crosscut budgets to support interagency efforts.

Boost heat preparedness, response, and resilience in every corner of our nation.

Extreme heat has become a national concern, threatening every community in the United States. To boost heat preparedness, response, and resilience nationwide, the President must:

- Direct FEMA to ensure that heat preparedness is a core component of national preparedness capabilities. At minimum, FEMA should support extreme heat regional scenario planning and tabletop exercises; incorporate extreme heat into Emergency Support Functions, the National Incident Management System, and the Community Lifelines program; help states, municipalities, tribes, and territories integrate heat into Hazard Mitigation Planning; work with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to provide language-accessible alerts via the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System; and clarify when extreme heat becomes a major disaster.

- Direct FEMA, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), and other agencies that use Benefit-Cost Analysis (BCA) for funding decisions to ensure that BCA methodologies adequately represent impacts of extreme heat, such as economic losses, learning losses, wage losses, and healthcare costs. This may require updating existing methods to avoid systematically and unintentionally disadvantaging heat-mitigation projects.

- Direct FEMA, in accordance with Section 322 of the Stafford Act, to create guidance on extreme heat hazard mitigation and eligibility criteria for hazard mitigation projects.

- Direct agencies participating in the Thriving Communities Network to integrate heat adaptation into place-based technical assistance and capacity-building resources.

- Direct the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to form a working group on accelerating resilience innovation, with extreme heat as an emphasis area. Within a year, the group should deliver a report on opportunities to use tools like federal research and development, public-private partnerships, prize challenges, advance market commitments, and other mechanisms to position the United States as a leader on game-changing resilience technologies.

Usher in a new era of heat forecasting, research, and data.

Extreme heat’s impacts are not well-quantified, limiting a systematic national response. To usher in a new era of heat forecasting, research, and data, the President must:

- Direct the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Weather Service (NWS) to expand the HeatRisk tool to include Alaska, Hawaii, and U.S. territories; provide information on real-time health impacts; and integrate sector-specific data so that HeatRisk can be used to identify risks to energy and the electric grid, health systems, transportation infrastructure, and more.

- Direct NOAA, through NIHHIS, to rigorously assess the impacts of extreme heat on all sectors of the economy, including agriculture, energy, health, housing, labor, and transportation. In tandem, NIHHIS and OMB should develop metrics tracking heat impact that can be incorporated into agency budget justifications and used to evaluate federal infrastructure investments and grant funding.

- Direct the NIHHIS IC to establish a new working group focused on methods for measuring heat-related deaths, illnesses, and economic impacts. The working group should create an inventory of federal datasets that track heat impacts, such as the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) datasets and power outage data from the Energy Information Administration.

- Direct NWS to define extreme heat weather events, such as “heat domes”, which will help unlock federal funding and coordinate disaster responses across federal agencies.

Protect workers and businesses from heat.

Americans become ill and even die due to heat exposure in the workplace, a moral failure that also threatens business productivity. To protect workers and businesses, the President must:

- Finalize a strong rule to prevent heat injury and illness in the workplace. The Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA)’s August 2024 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking is a crucial step towards a federal heat standard to protect workers. OSHA should quickly finalize this standard prior to the 2025 heat season.

- Direct OSHA to continue implementing the agency’s National Emphasis Program on heat, which enforces employers’ obligation to protect workers against heat illness or injury. OSHA should additionally review employers’ practices to ensure that workers are protected from job or wage loss when extreme heat renders working conditions unsafe.

- Direct the Department of Labor (DOL) to conduct a nationwide study examining the impacts of heat on the U.S. workforce and businesses. The study should quantify and monetize heat’s impacts on labor, productivity, and the economy.

- Direct DOL to provide technical assistance to employers on tailoring heat illness prevention plans and implementing cost-effective interventions that improve working conditions while maintaining productivity.

Prepare healthcare systems for heat impacts.

Extreme heat is both a public health emergency and a chronic stress to healthcare systems. Addressing the chronic disease epidemic will be impossible without treating the symptom of extreme heat. To prepare healthcare systems for heat impacts, the President must:

- Direct the HHS Secretary to consider using their authority to declare a Public Health Emergency in the event of an extreme heat wave.

- Direct HHS to embed extreme heat throughout the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), including by:

- Developing heat-specific response guidance for healthcare systems and clinics.

- Establishing thresholds for mobilizing the National Disaster Medical System.

- Providing extreme heat training to the Medical Reserve Corps.

- Simulating the cascading impacts of extreme heat through Medical Response and Surge Exercise scenarios and tabletop exercises.

- Direct HHS and the Department of Education to partner on training healthcare professionals on heat illnesses, impacts, risks to vulnerable populations, and treatments.

- Direct the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to integrate resilience metrics, including heat resilience, into its quality measurement programs. Where relevant, environmental conditions, such as chronic high heat, should be considered in newly required screenings for the social determinants of health.

- Direct the CDC’s Collaborating Office for Medical Examiners and Coroners to develop a standard protocol for surveillance of deaths caused or exacerbated by extreme heat.

Ensure affordably cooled and heat-resilient housing, schools, and other facilities.

Cool homes, schools, and other facilities are crucial to preventing heat illness and death. To prepare the build environment for rising temperatures, the President must:

Promote Housing and Cooling Access

- Direct HUD to protect vulnerable populations by (i) updating Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards to ensure that manufactured homes can maintain safe indoor temperatures during extreme heat, (ii) stipulating that mobile home park owners applying for Section 207 mortgages guarantee resident safety in extreme heat (e.g., by including heat in site hazard plans and allowing tenants to install cooling devices, cool walls, and shade structures), and (iii) guaranteeing that renters receiving housing vouchers or living in public housing have access to adequate cooling.

- Direct the Federal Housing Finance Agency to require that new properties must adhere to the latest energy codes and ensure minimum cooling capabilities in order to qualify for a Government Sponsored Enterprise mortgage.

- Ensure access to cooling devices as a medical necessity by directing the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to include high-efficiency air conditioners and heat pumps in Publication 502, which defines eligible medical expenses for a variety of programs.

- Direct HHS to (i) expand outreach and education to state Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) administrators and subgrantees about eligible uses of funds for cooling, (ii) expand vulnerable populations criteria to include pregnant people, and (iii) allow weatherization benefits to apply to cool roofs and walls or green roofs.

- Direct agencies to better understand population vulnerability to extreme heat, such as by integrating the Census Bureau’s Community Resilience Estimates for Heat into existing risk and vulnerability tools and updating the American Community Survey with a question about cooling access to understand household-level vulnerability.

- Direct the Department of Energy (DOE) to work with its Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) contractors to ensure that home energy audits consider passive cooling interventions like cool walls and roofs, green roofs, strategic placement of trees to provide shading, solar shading devices, and high-efficiency windows.

- Extend the National Initiative to Advance Building Codes (NIABC), and direct agencies involved in that initiative to (i) develop codes and metrics for sustainable and passive cooling, shade, materials selection, and thermal comfort, and (ii) identify opportunities to accelerate state and local adoption of code language for extreme heat adaptation.

Prepare Schools and Other Facilities

- Direct the Department of Education to collect data to better understand how schools are experiencing and responding to extreme heat, and to strengthen education and outreach on heat safety and preparedness for schools. This should include sponsored sports teams and physical activity programs. The Department should also collaborate with USDA on strategies to braid funding for green and shaded schoolyards.

- Direct the Administration for Children and Families to develop extreme heat guidance and temperature standards for Early Childhood Facilities and Daycares.

- Direct USDA to develop a waiver process for continuing school food service when extreme heat disrupts schedules during the school year.

- Direct the General Services Administration (GSA) to identify and pursue opportunities to demonstrate passive and resilient cooling strategies in public buildings.

- Direct the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to increase coordination with long-term care facilities during heat events to ensure compliance with existing indoor temperature regulations, develop plans for mitigating excess indoor heat, and build out energy redundancy plans, such as back-up power sources like microgrids.

- Direct the Bureau of Prisons, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to collect data on air conditioning coverage in federal prisons and detention facilities and develop temperature standards that ensure thermal safety of inmates and the prison and detention workforce.

- Direct the White House Domestic Policy Council to create a Cool Corridors Federal Partnership, modeled after the Urban Waters Federal Partnership. The partnership of agencies would leverage data, research, and existing grant programs for community-led pilot projects to deploy heat mitigation efforts, like trees, along transportation routes.

Legislative Branch

Congress can support the President in combating extreme heat by increasing funds for heat-critical federal programs and by providing new and explicit authorities for federal agencies.

Treat extreme heat like the emergency it is.

Extreme heat has devastating human and societal impacts that are on par with other federally recognized disasters. To treat extreme heat like the emergency it is, Congress must:

- Institutionalize and provide long-term funding for the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS), the NIHHIS Interagency Committee (IC), and the National Heat Executive Council (NHEC), including functions and personnel. NIHHIS is critical to informing heat preparedness, response, and resilience across the nation. An IC and NHEC will ensure federal government coordination and cross-sector collaboration.

- Create the National Heat Commission, modeled on the Wildfire Mitigation and Management Commission. The Commission’s first action should be creating a report for Congress on whole-of-government solutions to address extreme heat.

- Adopt H.R. 3965, which would amend the Stafford Act to explicitly include extreme heat in the definition of “major disaster”. Congress should also define the word “damages” in Section 102 of the Stafford Act to include impacts beyond property and economic losses, such as learning losses, wage losses, and healthcare costs.

- Direct and fund FEMA, NOAA, and CDC to establish a real-time heat alert system that aligns with the World Meteorological Organization’s Early Warnings for All program.

- Direct the Congressional Budget Office to produce a report assessing the costs of extreme heat to taxpayers and summarizing existing federal funding levels for heat.

- Appropriate full funding for emergency contingency funds for LIHEAP and the Public Health Emergency Program, and increase the annual baseline funding for LIHEAP.

- Update the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act to prohibit residential utilities from shutting off beneficiaries’ power during periods of extreme heat due to overdue bills.

- Adopt S. 2501, which would keep workers safe by requiring basic labor protections, such as water and breaks, in the event of indoor and outdoor extreme temperatures.

- Establish sector-specific Centers of Excellence for Heat Workplace Safety, beginning with military, transportation, and farm labor.

Build community heat resilience by readying critical infrastructure.

Investments in resilience pay dividends, with every federal dollar spent on resilience returning $6 in societal benefits. Our nation will benefit from building thriving communities that are prepared for extreme heat threats, adapted to rising temperatures, and capable of withstanding extreme heat disruptions. To build community heat resilience, Congress must:

- Establish the HeatSmart Grids Initiative as a partnership between DOE, FEMA, HHS, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the North American Electric Reliability Corporation, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). This initiative will ensure that electric grids are prepared for extreme heat, including risk of energy system failures during extreme heat and the necessary emergency and public health responses. This program should (i) perform national audits of energy security and building-stock preparedness for outages, (ii) map energy resilience assets such as long-term energy storage and microgrids, (iii) leverage technologies for minimizing grid loads such as smart grids and virtual power plants, and (iv) coordinate protocols with FEMA’s Community Lifelines and CISA’s Critical Infrastructure for emergency response.

- Update the LIHEAP formula to better reflect cooling needs of low-income Americans.

- Amend Title I of the Elementary & Secondary Education Act to clarify that Title I funds may be used for school infrastructure upgrades needed to avoid learning loss; e.g., replacement of HVAC systems or installation of cool roofs, walls, and pavements and solar and other shade canopies, green roofs, trees and green infrastructure to keep school buildings at safe temperatures during heat waves.

- Direct the HHS Secretary to submit a report to Congress identifying strategies for maximizing federal childcare assistance dollars during the hottest months of the year, when children are not in school. This could include protecting recent increased childcare reimbursements for providers who conform to cooling standards.

- Direct the HUD Secretary to submit a report to Congress identifying safe residential temperature standards for federally assisted housing units and proposing strategies to ensure compliance with the standards, such as extending utility allowances to cooling.

- Direct the DOT Secretary to conduct an independent third-party analysis of cool pavement products to develop metrics to evaluate thermal performance over time, durability, road subsurface temperatures, road surface longevity, and solar reflectance across diverse climatic conditions and traffic loads. Further, the analysis should assess (i) long-term performance and maintenance and (ii) benefits and potential trade-offs.

- Fund FEMA to establish a new federal grant program for community heat resilience, modeled on California’s “Extreme Heat and Community Resilience” program and in line with H.R. 9092. This program should include state agencies and statewide consortia as eligible grantees. States should be required to develop and adopt an extreme heat preparedness plan to be eligible for funds.

- Authorize and fund a new National Resilience Hub program at FEMA. This program would define minimum criteria that must be met for a community facility to be federally recognized as a resilience hub, and would provide funding to subsidize operations and emergency response functions of recognized facilities. Congress should also direct the FEMA Administrator to consider activities to build or retrofit a community facility meeting these criteria as eligible activities for Section 404 Hazard Mitigation Grants and funding under the Building Resilience Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program.

- Authorize and fund HHS to establish an Extreme Weather Resilient Health System Grant Program to prepare low-resource healthcare institutions (such as rural hospitals or federally qualified health centers) for extreme weather events.

- Fund the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to establish an Extreme Heat program and clearinghouse for design, construction, operation, and maintenance of buildings and infrastructure systems under extreme heat events.

- Fund HUD to launch an Affordable Cooling Housing Challenge to identify opportunities to lower the cost of new home construction and retrofits adapted to extreme heat.

- Expand existing rebates and tax credits (including HER, HEAR, 25C, 179D, Direct Pay) to include passive cooling tech such as cool walls, pavements, and roofs (H.R. 9894), green roofs, solar glazing, and solar shading. Revise 25C to be refundable at purchase.

- Authorize a Weatherization Readiness Program (H.R. 8721) to address structural, plumbing, roofing, and electrical issues, and environmental hazards with dwelling units unable to receive effective assistance from WAP, such as for implementing cool roofs.

- Fund the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) Urban and Community Forestry (UCF) Program to develop heat-adapted tree nurseries and advance best practices for urban forestry that mitigates extreme heat, such as strategies for micro forests.

Leveraging the Farm Bill to build national heat resilience.

Farm, food, forestry, and rural policy are all impacted by extreme heat. To ensure the next Farm Bill is ready for rising temperatures, Congress should:

- Double down on urban forestry, including by:

- Reauthorizing the UCF Grant program.

- Funding and directing the USFS UCF Program to support states, locals and Tribes on maintenance solutions for urban forests investments.

- Funding and authorizing a Green Schoolyards Grant under the UCF Program.

- Reauthorize the Farm Labor Stabilization and Protection Program, which supports employers in improving working conditions for farm workers.

- Reauthorize the Rural Emergency Health Care Grants and Rural Hospital Technical Assistance Program to provide resources and technical assistance to rural hospitals to prepare for emerging threats like extreme heat

- Direct the USDA Secretary to submit a report to Congress on the impacts of extreme heat on agriculture, expected costs of extreme heat to farmers (input costs and losses), consumers and the federal government (i.e. provision of SNAP benefits and delivery of insurance and direct payment for losses of agricultural products), and available federal resources to support agricultural and food systems adaptation to hotter temperatures.

- Authorize the following expansions:

- Agriculture Conservation Easement Program to include agrivoltaics.

- Environmental Quality Incentives Program to include facility cooling systems

- The USDA’s 504 Home Repair program to include funding for high-efficiency air conditioning and other sustainable cooling systems.

- The USDA’s Community Facilities Program to include funding for constructing resilience centers.These resilience centers should be constructed to minimum standards established by the National Resilience Hub Program, if authorized.

- The USDA’s Rural Business Development Grant program to include high-efficiency air conditioning and other sustainable cooling systems.

Funding critical programs and agencies to build a heat-ready nation.

To protect Americans and mitigate the $160+ billion annual impacts of extreme heat, Congress will need to invest in national heat preparedness, response, and resilience. The tables on the following pages highlight heat-critical programs that should be extended, as well as agencies that need more funding to carry out heat-critical work, such as key actions identified in the Executive section of this Heat Policy Agenda.