Trump Administration Again Refuses To Disclose Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Size

The Trump administration has denied a request from the Federation of American Scientists to disclose the size of the US nuclear weapons stockpile and the number of dismantled warheads.

The denial was made by the Department of Defense Formerly Restricted Data Declassification Working Group (FDR DWG) in response to a petition from Steven Aftergood, director of the FAS Project on Government Secrecy, “that the Department of Energy (and the Department of Defense) authorize declassification of the size of the total U.S, nuclear stockpile and the number of weapons dismantled as of the end of fiscal year 2020.”

The decision to deny release of the data contradicts past US disclosure of such information, undercuts US criticism of secrecy in other nuclear-armed states, and weakens US ability to document its adherence to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. As Aftergood explained in the petition letter:

[su_quote]We believe that the reasons that led to the previous declassifications of stockpile information are still valid. The benefits of declassification are substantial while the detrimental consequences, if any, are insignificant.

As the first nuclear weapons state, the United States should strive to set a global example for clarity and transparency in nuclear weapons policy by disclosing its current stockpile size. Ambiguity is not helpful to anyone in this context.

Far from diminishing security, a credible USG account of its stockpile size both enhances deterrence and serves as a confidence building measure. Even if other nations do not immediately follow our lead, stockpile declassification sends a valuable message. And at a time when the future of US nuclear weapons policy is under discussion in Congress and elsewhere, stockpile disclosure also helps to provide a factual foundation for ongoing public deliberation.[/su_quote]

In its denial letter, the DOD Formerly Restricted Data Declassification Working Group (FDR DWG) did not respond to these points and gave no reason for the denial other than stating that “the information requested cannot be declassified at this time.”

Stockpile Size and Developments

The decision to deny declassification of the warhead stockpile and dismantlement numbers contradicts the publication of such data between 2010 and 2017 during which the Obama administration released annual numbers as well as the entire history of the stockpile size going back to 1945.

The decision also contradicts the decision in 2018 to declassify the data for 2017, the first year of the Trump administration.

In 2019, however, the Trump administration suddenly, and without explanation, decided to withhold the stockpile data.

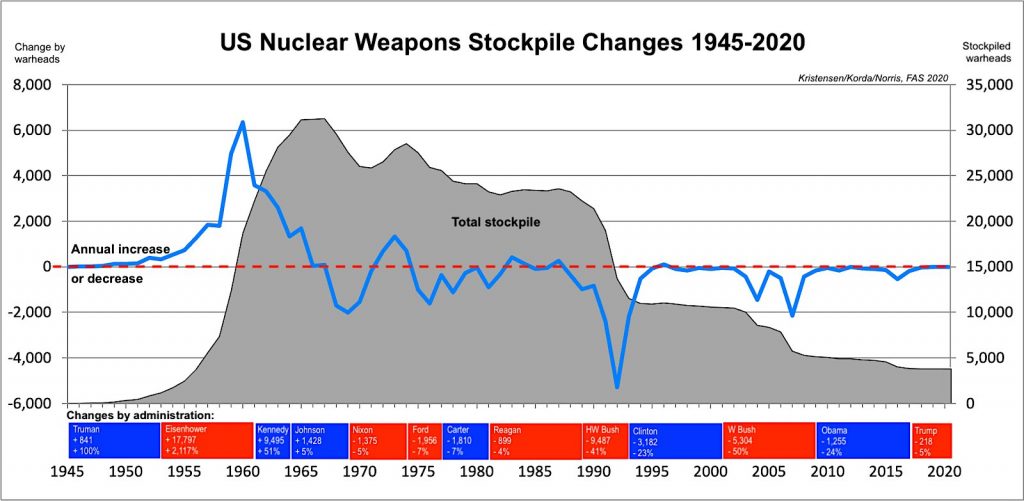

The available data shows significant fluctuations in the size of the US stockpile over the years depending on how the various administrations increased or decreased the number of nuclear weapons. The graph below shows the size of the stockpile over the years and the in- and out-flux of warheads from the stockpile. As far as we can gauge, the stockpile has remained relatively stable for the past three years at around 3,800 warheads. And the number of warheads dismantled per year is probably currently in the order of 300-350.

The size of the US nuclear weapons stockpile has fluctuated considerably over the years but remained relatively stable during the Trump administration. Click on image to view full size.

Implications and Recommendations

The decision by the Trump administration to deny declassification of the nuclear weapons stockpile size and dismantlement numbers contradict release of such data in the past for no apparent reason.

The increased secrecy of the US nuclear weapons arsenal comes at a time when the Trump administration has been criticizing China for “its secretive, nuclear crash buildup…” The administration’s criticism would carry a lot more weight if it didn’t hide its own stockpile behind a “great wall of secrecy.”

In addition to undercutting the US ability to push for greater transparency among other nuclear-armed states, the decision to classify warhead stockpile and dismantlement data also weakens the ability of the United States to demonstrate good faith on its efforts to continue to reduce its nuclear arsenal in the context of the upcoming review conference of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The decision enables conspiracists to spread false rumors that the United States is secretly increasing its nuclear arsenal.

The incoming Biden administration should overturn the Trump administration’s excessive and counterproductive nuclear secrecy and restore transparency of the US nuclear warhead stockpile and dismantlement data.

Background Information:

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Widespread Blurring of Satellite Images Reveals Secret Facilities

Want to know how to make a satellite imagery analyst instantly curious about something?

Blur it out.

Google Earth occasionally does this at the request of governments that want to keep prying eyes away from some of their more sensitive military or political sites. France, for example, has asked Google to obscure all imagery of its prisons after a French gangster successfully conducted a Hollywood-inspired jailbreak involving drones, smoke bombs, and a stolen helicopter(!)—and Google has agreed to comply by the end of 2018. In similar fashion, an old Dutch law requires Dutch companies to blur their satellite images of military and royal facilities—even to the point where a satellite imagery provider once doctored an image of Volkel Air Base after it was purchased by FAS’ very own Hans Kristensen.

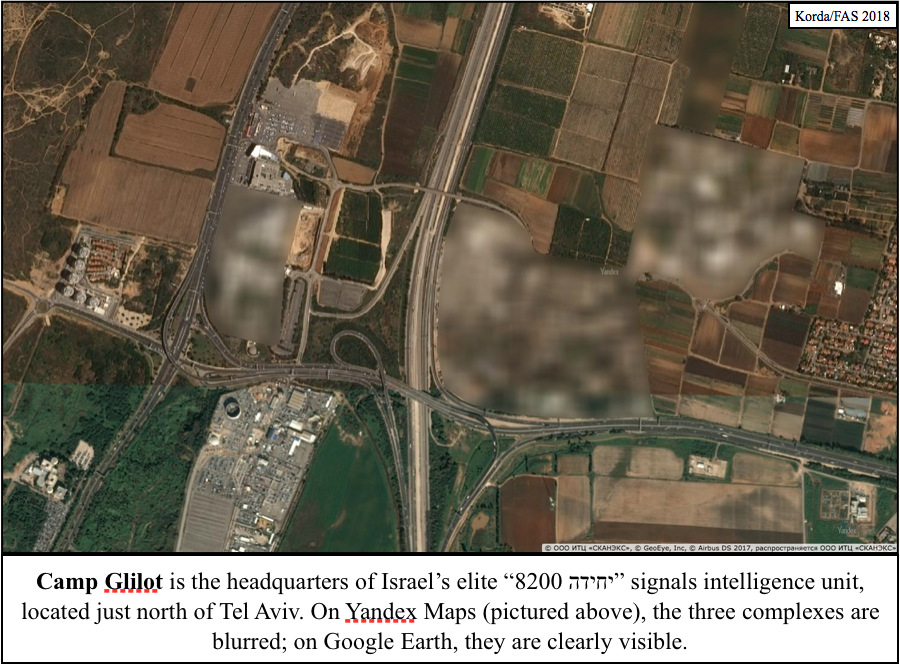

Yandex Maps—Russia’s foremost mapping service—has also agreed to selectively blur out specific sites beyond recognition; however, it has done so for just two countries: Israel and Turkey. The areas of these blurred sites range from large complexes—such as airfields or munitions storage bunkers—to small, nondescript buildings within city blocks.

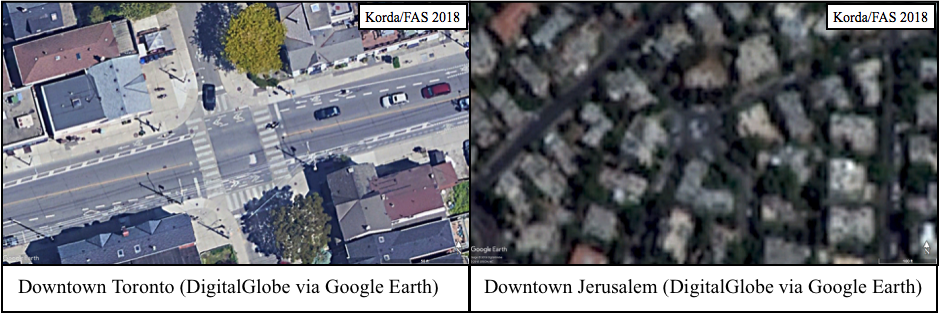

Although blurring out specific sites is certainly unusual, it is not uncommon for satellite imagery companies to downgrade the resolution of certain sets of imagery before releasing them to viewing platforms like Yandex or Google Earth; in fact, if you trawl around the globe using these platforms, you’ll notice that different locations will be rendered in a variety of resolutions. Downtown Toronto, for example, is always visible at an extremely high resolution; looking closely, you can spot my bike parked outside my old apartment. By contrast, imagery of downtown Jerusalem is always significantly blurrier; you can just barely make out cars parked on the side of the road.

As I explained in my previous piece about geolocating Israeli Patriot batteries, a 1997 US law known as the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment (KBA) prohibits US companies from publishing satellite imagery of Israel at a Ground Sampling Distance lower than what is commercially available. This generally means that US-based satellite companies like DigitalGlobe and viewing platforms like Google Earth won’t publish any images of Israel that are better than 2m resolution.

Foreign mapping services like Russia’s Yandex are legally not subject to the KBA, but they tend to stick to the 2m resolution rule regardless, likely for two reasons. Firstly, after 20 years the KBA standard has become somewhat institutionalized within the satellite imagery industry. And secondly, Russian companies (and the Russian state) are surely wary of doing anything to sour Russia’s critical relationship with Israel.

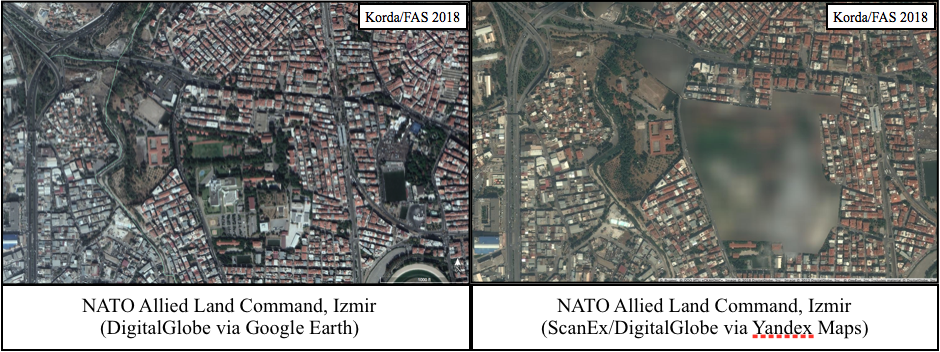

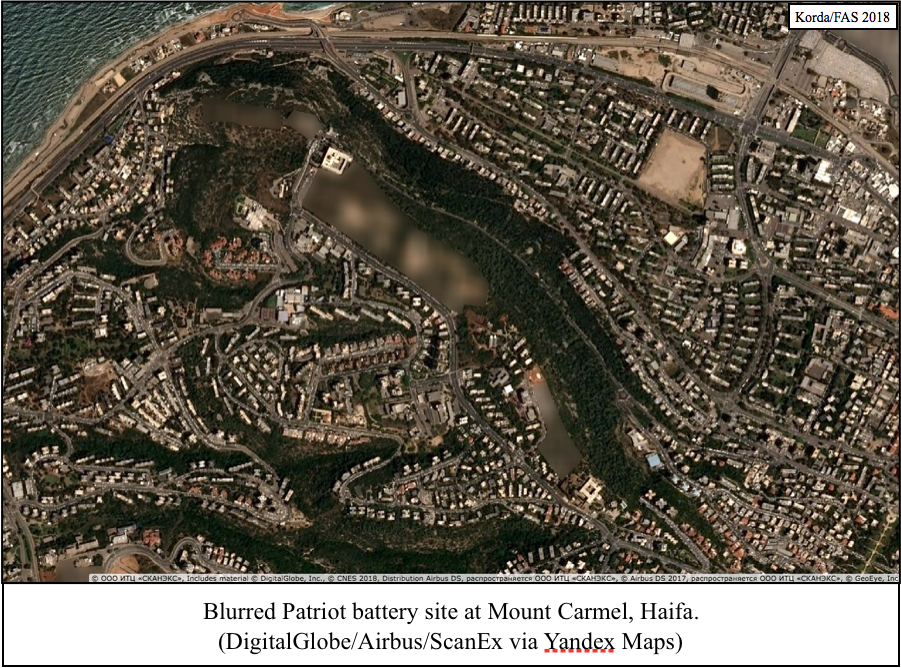

However, Yandex has taken a step well beyond simply downgrading its Israeli imagery, as is typical for most mapping services. Yandex itself—or perhaps its imagery provider ScanEx—has blurred out specific military installations in their entirety. Interestingly, it has done the same to Turkey, a country that benefits from no special standards and is therefore almost always shown in very high resolution.

This blurring is almost certainly the result of requests from both Israel and Turkey; it seems highly unlikely that a Russian company would undertake such a time-consuming task of its own volition. Fortunately (from an OSINT perspective), this has had the unintended effect of revealing the location and exact perimeter of every significant military facility within both countries, if one is obsessive curious enough to sift through the entire map looking for blurry patches. Matching the blurred sites to un-blurred (albeit downgraded) imagery available through Google Earth is a method of “tipping and cueing,” in which one dataset is used to inform a more detailed analysis of a second dataset.

My complete list of blurred sites in both Israel and Turkey totals over 300 distinct buildings, airfields, ports, bunkers, storage sites, bases, barracks, nuclear facilities, and random buildings—prompting several intriguing points of consideration:

- Included in the list of Yandex’s blurred sites are at least two NATO facilities: Allied Land Command (LANDCOM) in Izmir, and Incirlik Air Base, which hosts the largest contingent of US B61 nuclear gravity bombs at any single NATO base.

- Strangely, no Russian facilities have been blurred—including its nuclear facilities, submarine bases, air bases, launch sites, or numerous foreign military bases in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, or the Middle East.

- Although none of Russia’s permanent military installations in Syria have been blurred, almost the entirety of Syria is depicted in extremely low resolution, making it nearly impossible to utilize Yandex for analyses of Syrian imagery. By contrast, both Crimea and the entire Donbass region are visible at very high resolutions, so this blurring standard applies only selectively to Russia’s foreign adventures.

- All four Israeli Patriot batteries that I identified using radar interference in my previous post have been blurred out, confirming that these sites do indeed have a military function.

Putting aside the geopolitical intrigue of Russia’s relations with both Israel and Turkey, Yandex’s actions are a prime example of what is known as the Streisand Effect. In 2003, Barbra Streisand attempted to sue a photographer who posted photos of her Malibu mansion online, claiming $10 million in damages and demanding that the innocuous photo be taken down. Her actions completely backfired: not only did Streisand lose the case and have to cover the defendant’s legal fees, but the attention raised by her lawsuit directed significant traffic to the photo in question. Before the lawsuit, the photo had only been viewed six times (including twice by Streisand’s lawyers); a month later, the photo had accumulated over 420,000 views—a prime example of how attempting to obscure something is actually likely to result in unwanted attention.

So too with Yandex. By complying with requests to selectively obscure military facilities, the mapping service has actually revealed their precise locations, perimeters, and potential function to anyone curious enough to find them all.