Improving Government Capacity: Unleashing the capacity, creativity, energy, and determination of the public sector workforce

Peter Bonner is a Senior Fellow at FAS.

Katie: Peter, first, can you explain what government capacity means to you?

Peter: What government capacity means to me is ensuring that the people in the public sector, federal government primarily, have the skills, the tools, the technologies, the relationships, and the talent that help them meet their agency missions they need to do their jobs.

Those agency missions are really quite profound. I think we lose sight of this: if you’re working at the EPA, your job is to protect human health in the environment. If you’re working at the Department of the Interior, it’s to conserve and protect our natural resources and cultural heritage for the benefit of the public. If you’re working for HHS, you’re enhancing the health and well-being of all Americans. You’re working for the Department of Transportation, you’re ensuring a safe and efficient transportation system. And you can get into the national security agencies about protecting us from our enemies, foreign and domestic. These missions are amazing. Building that capacity so that the people can do their jobs better and more effectively is a critical and noble undertaking. Government employees are stewards of what we hold in common as a people. To me, that’s what government capacity is about.

Mr. Bonner’s Experience and Ambitions at FAS

You’ve had a long career in government – but how is it that you’ve come to focus on this particular issue as something that could make a big difference?

I’ve spent a couple of decades building government capacity in different organizations and roles, most recently as a government executive and political appointee as an associate director at the Office of Personnel Management. Years ago I worked as a contractor with a number of different companies, building human capital and strategic consulting practices. In all of those roles, in one way or another, it’s been about building government capacity.

One of my first assignments when I worked as a contractor was working on the Energy Star program, and helping to bridge the gaps between the public sector interests – wanting to create greater energy efficiency and reduce energy usage to address climate change – to the private sector interests – making sure their products were competitive and using market forces to demonstrate the effectiveness of federal policy. This work promoted energy efficiency across energy production, computers, refrigerators, HVAC equipment, even commercial building and residential housing. Part of the capacity building piece of that was working with the federal staff and the federal clients who ran those programs, but also making sure they had the right sets of collaboration skills to work effectively with the private sector around these programs and work effectively with other federal agencies. Agencies not only needed to work collaboratively wih the private sector, but across agencies as well. Those collaboration skills–those skills to make sure they’re working jointly inter-agency – don’t always come naturally because people feel protective about their own agency, their own budgets, and their own missions. So that’s an example of building capacity.

Another project early on I was involved in was helping to develop a training program for inspectors of underground storage tanks. That’s pretty obscure, but underground storage tanks have been a real challenge in the nation in creating groundwater pollution. We developed an online course using simulations on how to detect leaks and underground storage tanks. The capacity building piece was getting the agencies and tank inspectors at the state and local level to use this new learning technology to make their jobs easier and more effective.

Capacity building examples abound – helping OPM build human capital frameworks and improve operating processes, improving agency performance management systems, enhancing the skills of Air Force medical personnel to deal with battlefield injuries, and on. I’ve been doing capacity building through HR transformation, learning, leadership development, strategy and facilitation, human centered design, and looking at how do you develop HR and human capital systems that support that capacity building in the agencies. So across my career, those are the kinds of things that I’ve been involved in around government capacity.

What brought you to FAS and what you’re doing now?

I left my job as the associate director for HR Solutions at the Office of Personnel Management last May with the intent of finding ways to continue to contribute to the effective functioning of the federal government. This opportunity came about from a number of folks I’d worked with while at OPM and elsewhere.

FAS is in a unique position to change the game in federal capacity building through thought leadership, policy development, strategic placement of temporary talent, and initiatives to bring more science and technical professionals to lead federal programs.

I’m really trying to help change the game in talent acquisition and talent management and how they contribute to government capacity. That ranges from upfront hiring in the HR arena through to onboarding and performance management and into program performance.

I think what I’m driven by at FAS is to really unleash the capacity, the creativity, the energy, the determination of the public sector workforce to be able to do their jobs as efficiently and effectively as they know how. The number of people I know in the federal government that have great ideas on how to improve their programs in the bottom left hand drawer of their desk or on their computer desktop, that they can never get around to because of everything else that gets in the way.

There are ways to cut through the clutter to help make hiring and talent management effective. Just in hiring: creative recruiting and sourcing for science and technical talent, using hiring flexibilities and hiring authorities on hand, equipping HR staffing specialists and hiring managers with the tools they need, working across agencies on common positions, accelerating background checks are all ways to speed up the hiring process and improve hiring quality.

It’s the stuff that gets in the way that inhibits their ability to do these things. So that unleashing piece is the real reason I’m here. When it comes to the talent management piece changing, if you can move the needle a little bit on the perception of public sector work and federal government work, because the perception, the negative perception of what it’s like to work in the federal government or the distrust in the federal government is just enormous. The barriers there are profound. But if we can move the needle on that just a little bit, and if we can change the candidate experience of the person applying for a federal job so that they, while it may be arduous, results in a positive experience for them and for the hiring manager and HR staffing specialist, that then becomes the seed bed for a positive employee experience in the federal job. That then becomes the seed bed for an effective customer experience because the linkage between employee experience and customer experience is direct. So if we can shift the needle on those things just a little bit, we then start to change the perception of what public sector work is like, and tap into that energy of what brought them to the public sector job in the first place, which by and large is the mission of the agency.

Using Emerging Technologies to Improve Government Capacity

How do you see emerging technologies assisting or helping that mission?

The emerging technologies in talent management are things that other sectors of the economy are working with and that the federal government is quickly catching up on. Everybody thinks the private sector has this lock picked. Well, not necessarily. Private sector organizations also struggle with HR systems that effectively map to the employee journey and that provide analytics that can guide HR decision-making along the way.

A bright spot for progress in government capacity is in recruiting and sourcing talent. Army Corps of Engineers, Department of Energy are using front end recruiting software to attract people into their organizations. The Climate Corps, for example, or the Clean Energy Corps at Department of Energy. So they’re using those front end recruiting systems to bring people in and attract people in to submit the resumes and their applications that can again, create that positive initial candidate experience, then take ’em through the rest of the process. There’s work being done in automating and developing more effective online assessments from USA Hire, for example, so that if you’re in a particular occupation, you can take an online test when you apply and that test is going to qualify you for the certification list on that job.

Those are not emerging technologies but they are being deployed effectively in government. The mobile platforms to quickly and easily communicate with the applicants and communicate with the candidates at different stages of the process. Those things are coming online and already online in many of the agencies.

In addition to some experimentation with AI tools, I think one of the more profound pieces around technologies is what’s happening at the program level that is changing the nature of the jobs government workers do that then impacts what kind of person an HR manager is looking for.

For example, while there are specific occupations focused on machine learning, AI, and data analytics, data literacy and acumen and using these tools going to be part of everyone’s job in the future. So facility with those analytic tools and with the data visualization tools that are out there is going to have a profound impact on the jobs themselves. Then you back that up to, okay, what kind of person am I looking for here? I need somebody with that skill set coming in. Or who can be easily up-skilled into that. That’s true for data literacy, data analytics, some of the AI skill sets that are coming online. It’s not just the technologies within the talent management arena, but it’s the technologies that are happening in the front lines and the programs that then determine what kind of person I’m looking for and impact those jobs.

The Significance of Permitting Reform for Hiring

You recently put on a webinar for the Permitting Council. Do you mind explaining what that is and what the goal of the webinar was?

The Permitting Council was created under what’s called the Fast 41 legislation, which is legislation to improve the capacity and the speed at which environmental permits are approved so that we can continue with federal projects. Permitting has become a real hot button issue right now because the Inflation Reduction Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law created all of these projects in the field, some on federal lands, some on state and local lands, and some on tribal or private sector lands, that then create the need to do an environmental permit of some kind in order to get approval to build.

So under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, we’re trying to create internet for all, for example, and particularly provide internet access in rural communities where they haven’t had it before, and people who perhaps couldn’t afford it. That requires building cell towers and transmission lines on federal lands, and that then requires permits, require a permitting staff or a set of permitting contractors to actually go in and do that work.

Permitting has been, from a talent perspective, underresourced. They have not had the capacity, they have not had the staff even to keep up with the permits necessitated by these new pieces of legislation. So getting the right people hired, getting them in place, getting the productive environmental scientists, community planners, the scientists of different types, marine biologists, landscape folks, the fish and wildlife people who can advise on how best to do those environmental impact statements or categorical exclusions as a result of the National Environmental Protection Act – it has been a challenge. Building that capacity in the agencies that are responsible for permitting is really a high leverage point for these pieces of legislation because if I can’t build the cell tower, I then don’t realize the positive results from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. And you can think of the range of things that those pieces of legislation have fostered around the country from clean water systems in underserved communities, to highways, to bridges, to roads, to airports.

Another example is offshore wind. So you need marine biologists to be able to help do the environmental impact statements around building the wind turbines offshore and examine the effect on the marine habitats. It’s those people that the Department of Interior, the Department of Energy, and Department of Commerce need to hire to come in and run those programs and do those permits effectively. That’s what the Permitting Council does.

One of the things that we worked with with OPM and the Permitting Council together on is creating a webinar so that we got the hiring managers and the HR staffing specialists in the room at the same time to talk about the common bottlenecks that they face in the hiring process. After doing outreach and research, we created journey maps and a set of personas to identify a couple of the most salient and common challenges and high leverage challenges that they face.

Overcoming Hiring Bottlenecks for Permitting Talent, a webinar presented to government hiring managers, May 2024

Looking at the ecosystem within hiring, from what gets in the way in recruiting and sourcing, all the way through to onboarding, to focusing in on the position descriptions and what do you do if you don’t have an adequate position description upfront when you’re trying to hire that environmental scientist to the background check process and the suitability process. What do you do when things get caught in that suitability process? And if you can’t bring those folks on board in a timely fashion you risk losing them.

We focused on a couple of the key challenges in that webinar, and we had, I don’t know, 60 or 70 people who were there, the hiring managers and HR staffing specialists who took away from that a set of tools that they can use to accelerate and improve that hiring process and get high quality hires on quickly to assist with the permitting.

The Permitting Council has representatives from each of the agencies that do permitting, and works with them on cross agency activities. The council also has funding from some of these pieces of legislation to foster the permitting process, either through new software or people process, the ability to get the permits done as quickly as possible. So that’s what the webinar was about. I We’re talking about doing a second one to look at the more systemic and policy related changes, challenges in permitting hiring.

The Day One Project 2025

FAS has launched its Day One Project 2025, a massive call for nonpartisan, science-based policy ideas that a next presidential administration can utilize on “day one” – whether the new administration is Democrat or Republican. One of the areas we’ve chosen to focus on is Government Capacity. Will you be helping evaluate the ideas that are submitted?

I’ve had input into the Day One Project, and particularly around the talent pieces in the government capacity initiative, and also procurement and innovation in that area. I think the potential of that to help set the stage for talent reform more broadly, be it legislative policy, regulatory or the risk averse culture we have in the federal government. I think the impact of that Day One Project could be pretty profound if we get the right energy behind it. So one of the things that I’ve known for a while, but has come clear to me over the past five months working with FAS, is that there are black boxes in the talent management environment in the federal government. What I mean by that is that it goes into this specialized area of expertise and nobody knows what happens in that specialized area until something pops out the other end.

How do you shed light on the inside of those black boxes so it’s more transparent what happens? For instance: position descriptions when agencies are trying to hire someone. Sometimes what happens with position descriptions is that the job needs to be reclassified because it’s changed dramatically from the previous position description. Well, I know a little about classification and what happens in the classification process, but to most people looking from the outside to hiring managers, that’s a black box. Nobody knows what goes on. I mean, they don’t know what goes on within that classification process to know that it’s going to be worthwhile for them once they have the position description at the other end and are able to do an effective job announcement. Shedding light on that, I think has the potential to increase transparency and trust between the hiring manager and the HR folks or the program people and the human people.

If we’re able to create that greater transparency. If we’re able to tell the candidates when they come in and apply for a job where they are in the hiring process and whether they made the cert list or didn’t make the cert list. And if they are in the CT list, what’s next in terms of their assessment and the process? If they’ve gone through the interview, where are we in the decision deliberations about offering me the job? Same thing in suitability. Those are many black boxes all the way, all the way across. And creating transparency and communication around it, I think will go a long way, again, to moving that needle on the perception of what federal work is and what it’s like to work in the system. So it’s a long answer to a question that I guess I can summarize by saying, I think we are in a target rich environment here. There’s lots of opportunity here to help change the game.

Revitalizing Federal Jobs Data: Unleashing the Potential of Emerging Roles

Emerging technologies and creative innovation are pivotal economic pillars for the future of the United States. These sectors not only promise economic growth but also offer avenues for social inclusion and environmental sustainability. However, the federal government lacks reliable and comprehensive data on these sectors, which hampers its ability to design and implement effective policies and programs. A key reason for this data gap is the outdated and inadequate job categories and classifications used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

The BLS is the main source of official statistics on employment, wages, and occupations in the U.S. Part of the agency’s role is to categorize different industries, which helps states, researchers and other outside parties measure and understand the size of certain industries or segments of the economy. Another BLS purpose is to use the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system to categorize and define jobs based on their duties, skills, and education requirements. This is how all federal workers and contracted federal workers are classified. For an agency to create and fill a role, it needs a classification or SOC. State and private employers also use the classifications and data to allocate funding and determine benefits related to different kinds of positions.

Where no classification (SOC) or job exists, it is unclear whether hiring and contracting happen according to programmatic intent and in a timely manner. This is particularly concerning to some employers and federal agencies that need to align numerous jobs with the provisions of Justice 40, the Inflation Reduction Act and the newly created American Climate Corps. Many of the roles imagined by the American Climate Corps do not have classifications. This poses a significant barrier for effective program and policy design related to green and tech jobs.

The SOC system is updated roughly once every 10 years. There is not a set comprehensive review schedule for that or the industry categories. Updates are topical, with the last broad revision taking place in 2018. Unemployment reports and data related to wages are updated annually, and other topics less predictably. Updates and work on the SOC systems and categories for what are broadly defined as “green jobs” stopped in 2013 due to sequestration. This means that the BLS data may not capture the current and future trends and dynamics of the green and innovation economies, which are constantly evolving and growing.Because the BLS does not have a separate category for green jobs, it identifies them based on a variety of industry and occupation codes. The range spans restaurant industry SOCs to construction. Classifying positions this way cannot reflect the cross-cutting and interdisciplinary nature of green jobs. Moreover, the process may not account for the variations and nuances of green jobs, such as their environmental impact, social value, and skill level. For example, if you want to work with solar panels, there is a construction classification, but nothing for community design, specialized finance, nor any complementary typographies needed for projects at scale.

Similarly, the BLS does not have a separate category for tech jobs. It identifies them based on the “Information and Communication Technologies” occupational groups of the SOC system. Again, this approach may not adequately reflect the diversity and complexity of tech jobs, which may involve new and emerging skills and technologies that are not yet recognized by the BLS. There are no classifications for roles associated with machine learning or artificial intelligence. Where the private sector has a much-discussed large language model trainer role, the federal system has no such classification. Appropriate skills matching, resource allocation, and the ability to measure the numbers and impacts of these jobs on the economy will be difficult if not impossible to fully understand. Classifying tech jobs in this manner may not account for the interplay and integration of tech jobs with other sectors, such as health care, education, and manufacturing.

These data limitations have serious implications for policy design and evaluation. Without accurate and timely data on green and tech jobs, the federal government may not be able to assess the demand and supply of these jobs, identify skill gaps and training needs, allocate resources, and measure the outcomes and impacts of its policies and programs. This will result in missed opportunities, wasted resources, and suboptimal outcomes.

There is a need to update the BLS job categories and classifications to better reflect the realities and potentials of the green and innovation economies. This can be achieved by implementing the following strategic policy measures:

- Inter-Agency Collaboration: Establish an inter-agency task force, including representatives from the BLS, Department of Energy (DOE), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Education (ED), and the Department of Commerce (DOC), to review and update the current job categories and classifications. This task force would be responsible for ensuring that the classifications accurately reflect the evolving nature of jobs in the green and innovation economies.

- Public-Private Partnerships: Engage in public-private partnerships with industry leaders, academic institutions, and non-profit organizations. These partnerships can provide valuable insights into the changing job landscape and help inform the update of job categories and classifications. They can also facilitate the dissemination and adoption of the updated classifications among employers and workers, as well as the development and delivery of training and education programs related to green and tech jobs.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Conduct regular consultations with stakeholders, including educational institutions, employers, workers, and unions in the green and innovation economies. Their input can ensure that the updated classifications accurately represent the realities and challenges of the job market. They can also provide feedback and suggestions on how to improve the quality and accessibility of the BLS data.

- Regular Updates: Implement a policy for regular reviews and updates of job categories and classifications. The policy should also specify the frequency and criteria for the updates, as well as the roles and responsibilities of the involved agencies and partners.

By updating the BLS job categories and classifications, the federal government can ensure that its data and statistics accurately reflect the current and future job market, thereby supporting effective policy design and evaluation related to green and tech jobs. Accurate and current data that mirrors the ever-evolving job market will also lay the foundation for effective policy design and evaluation in the realms of green and tech jobs. This commitment can contribute to the development of a workforce that not only meets economic needs but also aligns with the nation’s environmental aspirations.

FAS Senior Fellow Jen Pahlka testifies on Using AI to Improve Government Services

Jennifer Pahlka (@pahlkadot) is a FAS Senior Fellow and the author of Recoding America: Why Government is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better. Here is Pahlka’s testimony about artificial intelligence presented today, January 10, 2024, to the full Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs hearing on “Harnessing AI to Improve Government Services and Customer Experience”. More can be found here, here, and here.

How the U.S. government chooses to respond to the changes AI brings is indeed critical, especially in its use to improve government services and customer experience. If the change is going to be for the better (and we can’t afford otherwise) it will not be primarily because of how much or how little we constrain AI’s use. Constraints are an important conversation, and AI safety experts are better suited to discuss these than me. But we could constrain agencies significantly and still get exactly the bad outcomes that those arguing for risk mitigation want to avoid. We could instead direct agencies to dive headlong into AI solutions, and still fail to get the benefit that the optimists expect. The difference will come down to how much or how little capacity and competency we have to deploy these technologies thoughtfully.

There are really two ways to build capacity: having more of the right people doing the right things (including but not limited to leveraging technology like AI) and safely reducing the burdens we place on those people. AI, of course, could help reduce those burdens, but not without the workforce we need – one that understands the systems we have today, the policy goals we have set, and the technology we are bringing to bear to achieve those goals. Our biggest priority as a government should be building that capacity, working both sides of that equation (more people, less burden.)

Building that capacity will require bodies like the US Senate to use a wide range of the tools at its disposal to shape our future, and use them in a specific way. Those tools can be used to create mandates and controls on the institutions that deliver for the American people, adding more rules and processes for administrative agencies and others to comply with. Or they can be used to enable these institutions to develop the capacity they so desperately need and to use their judgment in the service of agreed-upon goals, often by asking what mandates and controls might be removed, rather than added. This critical AI moment calls for enablement.

The recent executive order on AI already provides some new controls and safeguards. The order strikes a reasonable balance between encouragement and caution, but I worry that some of its guidance will be applied inappropriately. For example, some government agencies have long been using AI for day to day functions like handwriting recognition on envelopes or improved search to retrieve evidence more easily, and agencies may now subject these benign, low-risk uses to red tape based on the order. Caution is merited in some places, and dangerous in others, where we risk moving backwards, not forward. What we need to navigate these frameworks of safeguard and control are people in agencies who can tell the difference, and who have the authority to act accordingly.

Moreover, in many areas of government service delivery, the status quo is frankly not worth protecting. We understandably want to make sure, for instance, that applicants for government benefits aren’t unfairly denied because of bias in algorithms. The reality is that, to take just one benefit, one in six determinations of eligibility for SNAP is substantively incorrect today. If you count procedural errors, the rate is 44%. Worse are the applications and adjudications that haven’t been decided at all, the ones sitting in backlogs, causing enormous distress to the public and wasting taxpayer dollars. Poor application of AI in these contexts could indeed make a bad situation worse, but for people who are fed up and just want someone to get back to them about their tax return, their unemployment insurance check, or even their company’s permit to build infrastructure, something has to change. We may be able to make progress by applying AI, but not if we double down on the remedies that failed in the Internet Age and hope they somehow work in the age of AI. We must finally commit to the hard work of building digital capacity.

Applying ARPA-I: A Proven Model for Transportation Infrastructure

Executive Summary

In November 2021, Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which included $550 billion in new funding for dozens of new programs across the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT). Alongside historic investments in America’s roads and bridges, the bill created the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Infrastructure (ARPA-I). Building on successful models like the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Advanced Research Program-Energy (ARPA-E), ARPA-I’s mission is to bring the nation’s most innovative technology solutions to bear on our most significant transportation infrastructure challenges.

ARPA-I must navigate America’s uniquely complex infrastructure landscape, characterized by limited federal research and development funding compared to other sectors, public sector ownership and stewardship, and highly fragmented and often overlapping ownership structures that include cities, counties, states, federal agencies, the private sector, and quasi-public agencies. Moreover, the new agency needs to integrate the strong culture, structures, and rigorous ideation process that ARPAs across government have honed since the 1950s. This report is a primer on how ARPA-I, and its stakeholders, can leverage this unique opportunity to drive real, sustainable, and lasting change in America’s transportation infrastructure.

How to Use This Report

This report highlights the opportunity ARPA-I presents; orients those unfamiliar with the transportation infrastructure sector to the unique challenges it faces; provides a foundational understanding of the ARPA model and its early-stage program design; and empowers experts and stakeholders to get involved in program ideation. However, individual sections can be used as standalone tools depending on the reader’s prior knowledge of and intended involvement with ARPA-I.

- If you are unfamiliar with the background, authorization, and mission of ARPA-I, refer to the section “An Opportunity for Transportation Infrastructure Innovation.”

- If you are relatively new to the transportation infrastructure sector, refer to the section “Unique Challenges of the Transportation Infrastructure Landscape.”

- If you have prior transportation infrastructure experience or expertise but are new to the ARPA model, you can move directly to the sections beginning with “Core Tenets of ARPA Success.”

An Opportunity for Transportation Infrastructure Innovation

In November 2021, Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) authorizing the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) to create the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Infrastructure (ARPA-I), among other new programs. ARPA-I’s mission is to advance U.S. transportation infrastructure by developing innovative science and technology solutions that:

- lower the long-term cost of infrastructure development, including costs of planning, construction, and maintenance;

- reduce the life cycle impacts of transportation infrastructure on the environment, including through the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions;

- contribute significantly to improving the safe, secure, and efficient movement of goods and people; and

- promote the resilience of infrastructure from physical and cyber threats.

ARPA-I will achieve this goal by supporting research projects that:

- advance novel, early-stage research with practicable application to transportation infrastructure;

- translate techniques, processes, and technologies, from the conceptual phase to prototype, testing, or demonstration;

- develop advanced manufacturing processes and technologies for the domestic manufacturing of novel transportation-related technologies; and

- accelerate transformational technological advances in areas in which industry entities are unlikely to carry out projects due to technical and financial uncertainty.

ARPA-I is the newest addition to a long line of successful ARPAs that continue to deliver breakthrough innovations across the defense, intelligence, energy, and health sectors. The U.S. Department of Defense established the pioneering Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in 1958 in response to the Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite to develop and demonstrate high-risk, high-reward technologies and capabilities to ensure U.S. military technological superiority and confront national security challenges. Throughout the years, DARPA programs have been responsible for significant technological advances with implications beyond defense and national security, such as the early stages of the internet, the creation of the global positioning system (GPS), and the development of mRNA vaccines critical to combating COVID-19.

In light of the many successful advancements seeded through DARPA programs, the government replicated the ARPA model for other critical sectors, resulting in the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) within the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy within the Department of Energy, and, most recently, the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Health (ARPA-H) within the Department of Health and Human Services.

Now, there is the opportunity to bring that same spirit of untethered innovation to solve the most pressing transportation infrastructure challenges of our time. The United States has long faced a variety of transportation infrastructure-related challenges, due in part to low levels of federal research and development (R&D) spending in this area; the fragmentation of roles across federal, state, and local government; risk-averse procurement practices; and sluggish commercial markets. These challenges include:

- Roadway safety. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, an estimated 42,915 people died in motor vehicle crashes in 2021, up 10.5% from 2020.

- Transportation emissions. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the transportation sector accounted for 27% of U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2020, more than any other sector.

- Aging infrastructure and maintenance. According to the 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure produced by the American Society of Civil Engineers, 42% of the nation’s bridges are at least 50 years old and 7.5% are “structurally deficient.”

The Fiscal Year 2023 Omnibus Appropriations Bill awarded ARPA-I its initial appropriation in early 2023. Yet even before that, the Biden-Harris Administration saw the potential for ARPA-I-driven innovations to help meet its goal of net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, as articulated in its Net-Zero Game Changers Initiative. In particular, the Administration identified smart mobility, clean and efficient transportation systems, next-generation infrastructure construction, advanced electricity infrastructure, and clean fuel infrastructure as “net-zero game changers” that ARPA-I could play an outsize role in helping develop.

For ARPA-I programs to reach their full potential, agency stakeholders and partners need to understand not only how to effectively apply the ARPA model but how the unique circumstances and challenges within transportation infrastructure need to be considered in program design.

Unique Challenges of the Transportation Infrastructure Landscape

Using ARPA-I to advance transportation infrastructure breakthroughs requires an awareness of the most persistent challenges to prioritize and the unique set of circumstances within the sector that can hinder progress if ignored. Below are summaries of key challenges and considerations for ARPA-I to account for, followed by a deeper analysis of each challenge.

- Federal R&D spending on transportation infrastructure is considerably lower than other sectors, such as defense, healthcare, and energy, as evidenced by federal spending as a percentage of that sector’s contribution to gross domestic product (GDP).

- The transportation sector sees significant private R&D investment in vehicle and aircraft equipment but minimal investment in transportation infrastructure because the benefits from those investments are largely public rather than private.

- Market fragmentation within the transportation system is a persistent obstacle to progress, resulting in reliance on commercially available technologies and transportation agencies playing a more passive role in innovative technology development.

- The fragmented market and multimodal nature of the sector pose challenges for allocating R&D investments and identifying customers.

Lower Federal R&D Spending in Transportation Infrastructure

Federal R&D expenditures in transportation infrastructure lag behind those in other sectors. This gap is particularly acute because, unlike for some other sectors, federal transportation R&D expenditures often fund studies and systems used to make regulatory decisions rather than technological innovation. The table below compares actual federal R&D spending and sector expenditures for 2019 across defense, healthcare, energy, and transportation as a percentage of each sector’s GDP. The federal government spends orders of magnitude less on transportation than other sectors: energy R&D spending as a percentage of sector GDP is nearly 15 times higher than transportation, while health is 13 times higher and defense is nearly 38 times higher.

Public Sector Dominance Limits Innovation Investment

Since 1990, total investment in U.S. R&D has increased by roughly 9 times. When looking at the source of R&D investment over the same period, the private and public sectors invested approximately the same amount of R&D funding in 1982, but today the rate of R&D investment is nearly 4 times greater for the private industry than the government.

While there are problems with the bulk of R&D coming from the private sector, such as innovations to promote long-term public goods being overlooked because of more lucrative market incentives, industries that receive considerable private R&D funding still see significant innovation breakthroughs. For example, the medical industry saw $161.8 billion in private R&D funding in 2020 compared to only $61.5 billion from federal funding. More than 75% of this private industry R&D occurred within the biopharmaceutical sector where corporations have profit incentives to be at the cutting edge of advancements in medicine.

The transportation sector has one robust domain for private R&D investment: vehicle and aircraft equipment manufacturing. In 2018, total private R&D was $52.6 billion. Private sector transportation R&D focuses on individual customers and end users, creating better vehicles, products, and efficiencies. The vast majority of that private sector R&D does not go toward infrastructure because the benefits are largely public rather than private. Put another way, the United States invests more than 50 times the amount of R&D into vehicles than the infrastructure systems upon which those vehicles operate.

Market Fragmentation across Levels of Government

Despite opportunities within the public-dominated transportation infrastructure system, market fragmentation is a persistent obstacle to rapid progress. Each level of government has different actors with different objectives and responsibilities. For instance, at the federal level, USDOT provides national-level guidance, policy, and funding for transportation across aviation, highway, rail, transit, ports, and maritime modes. Meanwhile, the states set goals, develop transportation plans and projects, and manage transportation networks like the interstate highway system. Metropolitan planning organizations take on some of the planning functions at the regional level, and local governments often maintain much of their infrastructure. There are also local individual agencies that operate facilities like airports, ports, or tollways organized at the state, regional, or local level. Programs that can use partnerships to cut across this tapestry of systems are essential to driving impact at scale.

Local agencies have limited access and capabilities to develop cross-sector technologies. They have access to limited pools of USDOT funding to pilot technologies and thus generally rely on commercially available technologies to increase the likelihood of pilot success. One shortcoming of this current process is that both USDOT and infrastructure owner-operators (IOOs) play a more passive role in developing innovative technologies, instead depending on merely deploying market-ready technologies.

Multiple Modes, Customers, and Jurisdictions Create Difficulties in Efficiently Allocating R&D Resources

The transportation infrastructure sector is a multimodal environment split across many modes, including aviation, maritime, pipelines, railroads, roadways (which includes biking and walking), and transit. Each mode includes various customers and stakeholders to be considered. In addition, in the fragmented market landscape federal, state, and local departments of transportation have different—and sometimes competing—priorities and mandates. This dynamic creates difficulties in allocating R&D resources and considering access to innovation across these different modes.

Customer identification is not “one size fits all” across existing ARPAs. For example, DARPA has a laser focus on delivering efficient innovations for one customer: the Department of Defense. For ARPA-E, it is less clear; their customers range from utility companies to homeowners looking to benefit from lower energy costs. ARPA-I would occupy a space in between these two cases, understanding that its end users are IOOs—entities responsible for deploying infrastructure in many cases at the local or regional level.

However, even with this more direct understanding of its customers, a shortcoming of a system focused on multiple modes is that transportation infrastructure is very broad, occupying everything from self-healing concrete to intersection safety to the deployment of electrified mobility and more. Further complicating matters is the rapid evolution of technologies and expectations across all modes, along with the rollout of entirely new modes of transportation. These developments raise questions about where new technologies and capabilities fit in existing modal frameworks, what actors in the transportation infrastructure market should lead their development, and who the ultimate “customers” or end users of innovation are.

Having a matrixed understanding of the rapid technological evolution across transportation modes and their potential customers is critical to investing in and building infrastructure for the future, given that transportation infrastructure investments not only alter a region’s movement of people and goods but also fundamentally impact its development. ARPA-I is poised to shape learnings across and in partnership with USDOT’s modes and various offices to ensure the development and refinement of underlying technologies and approaches that serve the needs of the entire transportation system and users across all modes.

Core Tenets of ARPA Success

Success using the ARPA model comes from demonstrating new innovative capabilities, building a community of people (an “ecosystem”) to carry the progress forward, and having the support of key decision-makers. Yet the ARPA model can only be successful if its program directors (PDs), fellows, stakeholders, and other partners understand the unique structure and inherent flexibility required when working to create a culture conducive to spurring breakthrough innovations. From a structural and cultural standpoint, the ARPA model is unlike any other agency model within the federal government, including all existing R&D agencies. Partners and other stakeholders should embrace the unique characteristics of an ARPA.

Cultural Components

ARPAs should take risks.

An ARPA portfolio may be the closest thing to a venture capital portfolio in the federal government. They have a mandate to take big swings so should not be limited to projects that seem like safe bets. ARPAs will take on many projects throughout their existence, so they should balance quick wins with longer-term bets while embracing failure as a natural part of the process.

ARPAs should constantly evaluate and pivot when necessary.

An ARPA needs to be ruthless in its decision-making process because it has the ability to maneuver and shift without the restriction of initial plans or roadmaps. For example, projects around more nascent technology may require more patience, but if assessments indicate they are not achieving intended outcomes or milestones, PDs should not be afraid to terminate those projects and focus on other new ideas.

ARPAs should stay above the political fray.

ARPAs can consider new and nontraditional ways to fund innovation, and thus should not be caught up in trends within their broader agency. As different administrations onboard, new offices get built and partisan priorities may shift, but ARPAs should limit external influence on their day-to-day operations.

ARPA team members should embrace an entrepreneurial mindset.

PDs, partners, and other team members need to embrace the creative freedom required for success and operate much like entrepreneurs for their programs. Valued traits include a propensity toward action, flexibility, visionary leadership, self-motivation, and tenacity.

ARPA team members must move quickly and nimbly.

Trying to plan out the agency’s path for the next two years, five years, 10 years, or beyond is a futile effort and can be detrimental to progress. ARPAs require ultimate flexibility from day to day and year to year. Compared to other federal initiatives, ARPAs are far less bureaucratic by design, and forcing unnecessary planning and bureaucracy on the agency will slow progress.

Collegiality must be woven into the agency’s fabric.

With the rapidly shifting and entrepreneurial nature of ARPA work, the federal staff, contractors, and other agency partners need to rely on one another for support and assistance to seize opportunities and continue progressing as programs mature and shift.

Outcomes matter more than following a process.

ARPA PDs must be free to explore potential program and project ideas without any predetermination. The agency should support them in pursuing big and unconventional ideas unrestricted by a particular process. While there is a process to turn their most unconventional and groundbreaking ideas into funded and functional projects, transformational ideas are more important than the process itself during idea generation.

ARPA team members welcome feedback.

Things move quickly in an ARPA, and decisions must match that pace, so individuals such as fellows and PDs must work together to offer as much feedback as possible. Constructive pushback helps avoid blind alleys and thus makes programs stronger.

Structural Components

The ARPA Director sets the vision.

The Director’s vision helps attract the right talent and appropriate levels of ambition and focus areas while garnering support from key decision-makers and luminaries. This vision will dictate the types and qualities of PDs an ARPA will attract to execute within that vision.

PDs can make or break an ARPA and set the technical direction.

Because the power of the agency lies within its people, ARPAs are typically flat organizations. An ARPA should seek to hire the best and most visionary thinkers and builders as PDs, enable them to determine and design good programs, and execute with limited hierarchical disruption. During this process, PDs should engage with decision-makers in the early stages of the program design to understand the needs and realities of implementers.

Contracting helps achieve goals.

The ARPA model allows PDs to connect with universities, companies, nonprofits, organizations, and other areas of government to contract necessary R&D. This allows the program to build relationships with individuals without needing to hire or provide facilities or research laboratories.

Interactions improve outcomes.

From past versions of ARPA that attempted remote and hybrid environments, it became evident that having organic collisions across an ARPA’s various roles and programs is important to achieving better outcomes. For example, ongoing in-person interactions between and among PDs and technical advisors are critical to idea generation and technical project and program management.

Staff transitions must be well facilitated to retain institutional knowledge.

One of ARPA’s most unique structural characteristics is its frequent turnover. PDs and fellows are term-limited, and ARPAs are designed to turn over those key positions every few years as markets and industries evolve, so having thoughtful transition processes in place is vital, including considering the role of systems engineering and technical assistance (SETA) contractors in filling knowledge gaps, cultivating an active alumni network, and staggered hiring cycles so that large numbers of PDs and fellows are not all exiting their service at once.

Scaling should be built into the structure.

It cannot be assumed that if a project is successful, the private sector will pick that technology up and help it scale. Instead, an ARPA should create its own bridge to scaling in the form of programs dedicated to funding projects proven in a test environment to scale their technology for real-world application.

Technology-to-market advisors play a pivotal role.

Similarly to the dedicated funding for scaling described above, technology-to-market advisors are responsible for thinking about how projects make it to the real world. They should work hand in hand with PDs even in the early stages of program development to provide perspectives on how projects might commercialize and become market-ready. Without this focus, technologies run the risk of dying on the vine—succeeding technically, but failing commercially.

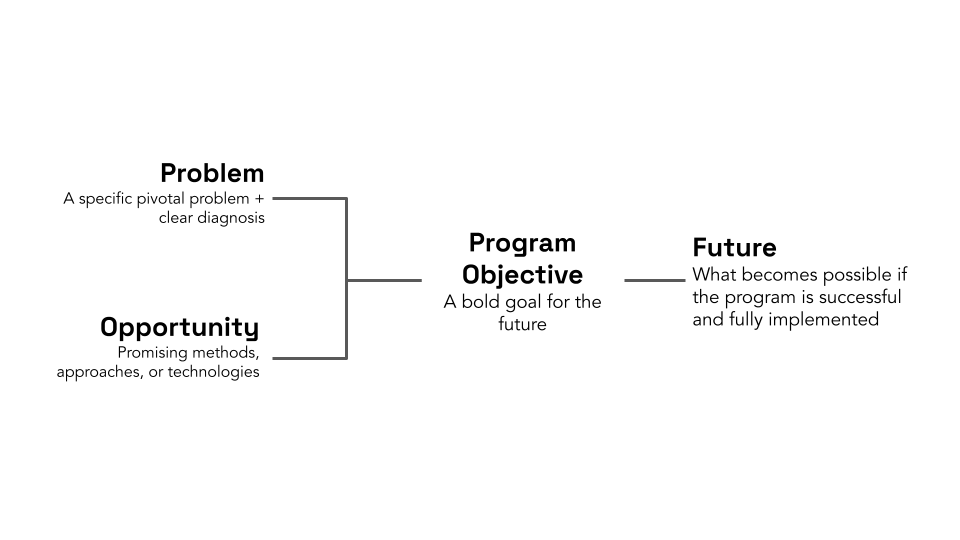

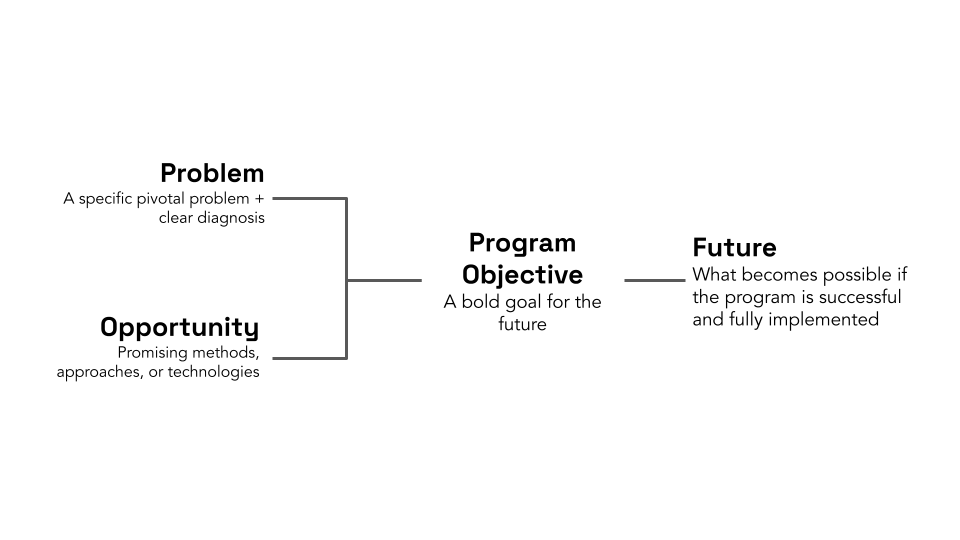

A Primer on ARPA Ideation

Tackling grand challenges in transportation infrastructure through ARPA-I requires understanding what is unique about its program design. This process begins with considering the problem worth solving, the opportunity that makes it a ripe problem to solve, a high-level idea of an ARPA program’s fit in solving it, and a visualization of the future once this problem has been solved. This process of early-stage program ideation requires a shift in one’s thinking to find ideas for innovative programs that fit the ARPA model in terms of appropriate ambition level and suitability for ARPA structure and objectives. It is also an inherently iterative process, so while creating a “wireframe” outlining the problem, opportunity, program objectives, and future vision may seem straightforward, it can take months of refining.

Common Challenges

No clear diagnosis of the problem

Many challenges facing our transportation infrastructure system are not defined by a single problem; rather, they are a conglomeration of issues that simultaneously need addressing. An effective program will not only isolate a single problem to tackle, but it will approach it at a level where something can be done to solve it through root cause analysis.

Thinking small and narrow

On the other hand, problems being considered for ARPA programs can be isolated down to the point that solving them will not drive transformational change. In this situation, narrow problems would not cater to a series of progressive and complementary projects that would fit an ARPA.

Incorrect framing of opportunities:

When doing early-stage program design, opportunities are sometimes framed as “an opportunity to tackle a problem.” Rather, an opportunity should reflect a promising method, technology, or approach already in existence but which would benefit from funding and resources through an advanced research agency program.

Approaching solutions solely from a regulatory or policy angle

While regulations and policy changes are a necessary and important component of tackling challenges in transportation infrastructure, approaching issues through this lens is not the mandate of an ARPA. ARPAs focus on supporting breakthrough innovations in developing new methods, technologies, capabilities, and approaches. Additionally, regulatory approaches to problem-solving can often be subject to lengthy policy processes.

No explicit ARPA role

An ARPA should pursue opportunities to solve problems where, without its intervention, breakthroughs may not happen within a reasonable timeframe. If the public or private sector already has significant interest in solving a problem, and they are well on their way to developing a transformational solution in a few years or less, then ARPA funding and support might provide a higher value-add elsewhere.

Lack of throughline

The problems identified for ARPA program consideration should be present as themes throughout the opportunities chosen to solve them as well as how programs are ultimately structured. Otherwise, a program may lack a targeted approach to solving a particular challenge.

Forgetting about end users

Human-centered design should be at the heart of how ARPA programs are scoped, especially when considering the scale at which designers need to think about how solving a problem will provide transformational change for everyday users.

Being solutions-oriented

Research programs should not be built with predetermined solutions in mind; they should be oriented around a specific problem to ensure that any solutions put forward are targeted and effective.

Not being realistic about direct outcomes of the program

Program objectives should not simply restate the opportunity, nor should they jump to where the world will be many years after the program has run its course. They should separate the tactical elements of a program and what impact they will ultimately drive. Designers should consider their program as one key step in a long arc of commercialization and adoption, with a firm sense of who needs to act and what needs to happen to make a program objective a reality.

Keeping these common mistakes in mind throughout the design process ensures that programs are properly scoped, appropriately ambitious, and in line with the agency’s goals. With these guideposts in mind, idea generators should begin their program design in the form of a wireframe.

Wireframe Development

The first phase in ARPA program development is creating a program wireframe, which is an outline of a potential program that captures key components for consideration to assess the program’s fit and potential impact. The template below shows the components characteristic of a program wireframe.

To create a fully fleshed-out wireframe, program directors work backward by first envisioning a future state that would be truly transformational for society and across sectors if it were to be realized. Then, they identify a clearly-articulated problem that needs solving and is hindering progress toward this transformational future state. During this process, PDs need to conduct extensive root cause analysis to consider whether the problem they’ve identified is exacerbated by policy, regulatory, or environmental complications—as opposed to those that technology can already solve. This will inform whether a problem is something that ARPA-I has the opportunity to impact fundamentally.

Next, program directors identify a promising opportunity—such as a method, approach, or technology—that, if developed, scaled, and implemented, would solve the problem they articulated and help achieve their proposed future state. When considering a promising opportunity, PDs must assess whether it front-runs other potential technologies that would also need developing to support it and whether it is feasible to achieve concrete results within three to five years and with an average program budget. Additionally, it is useful to think about whether an opportunity considered for program development is part of a larger cohort of potential programs that lie within an ARPA-I focus area that could all be run in parallel.

Most importantly, before diving into how to solve the problem, PDs need to articulate what has prevented this opportunity from already being solved, scaled, and implemented, and what explicit role or need there is for a federal R&D agency to step in and lead the development of technologies, methods, or approaches to incentivize private sector deployment and scaling. For example, if the private sector is already incentivized to, and capable of, taking the lead on developing a particular technology and it will achieve market readiness within a few years, then there is less justification for an ARPA intervention in that particular case. On the other hand, the prescribed solution to the identified problem may be so nascent that what is needed is more early-stage foundational R&D, in which case an ARPA program would not be a good fit. This area should be reserved as the domain of more fundamental science-based federal R&D agencies and offices.

One example to illustrate this maturity fit is DARPA investment in mRNA. While the National Institutes of Health contributed significantly to initial basic research, DARPA recognized the technological gap in being able to quickly scale and manufacture therapeutics, prompting the agency to launch the Autonomous Diagnostics to Enable Prevention and Therapeutics (ADEPT) program to develop technologies to respond to infectious disease threats. Through ADEPT, in 2011 DARPA awarded a fledgling Moderna Therapeutics with $25 million to research and develop its messenger RNA therapeutics platform. Nine years later, Moderna became the second company after Pfizer-BioNTech to receive an Emergency Use Authorization for its COVID-19 vaccine.

Another example is DARPA’s role in developing the internet as we know it, which was not originally about realizing the unprecedented concept of a ubiquitous, global communications network. What began as researching technologies for interlinking packet networks led to the development of ARPANET, a pioneering network for sharing information among geographically separated computers. DARPA then contracted BBN Technologies to build the first routers before becoming operational in 1969. This research laid the foundation for the internet. The commercial sector has since adopted ARPANET’s groundbreaking results and used them to revolutionize communication and information sharing across the globe.

Wireframe Refinement and Iteration

To guide program directors through successful program development, George H. Heilmeier, who served as the director of DARPA from 1975 to 1977, used to require that all PDs answer the following questions, known as the Heilmeier Catechism, as part of their pitch for a new program. These questions should be used to refine the wireframe and envision what the program could look like. In particular, wireframe refinement should examine the first three questions before expanding to the remaining questions.

- What are you trying to do? Articulate your objectives using absolutely no jargon.

- How is it done today, and what are the limits of current practice?

- What is new in your approach, and why do you think it will be successful?

- Who cares? If you are successful, what difference will it make?

- What are the risks?

- How much will it cost?

- How long will it take?

- What are the midterm and final “exams” to check for success?

Alongside the Heilmeier Catechism, a series of assessments and lines of questioning should be completed to pressure test and iterate once the wireframe has been drafted. This refinement process is not one-size-fits-all but consistently grounded in research, discussions with experts, and constant questioning to ensure program fit. The objective is to thoroughly analyze whether the problem we are seeking to solve is the right one and whether the full space of opportunities around that problem is ripe for ARPA intervention.

One way to think about determining whether a wireframe could be a program is by asking, “Is this wireframe science or is this science fiction?” In other words, is the proposed technology solution at the right maturity level for an ARPA to make it a reality? There is a relatively broad range in the middle of the technological maturity spectrum that could be an ARPA program fit, but the extreme ends of that spectrum would not be a good fit, and thus those wireframes would need further iteration or rejection. On the far left end of the spectrum would be basic research that only yields published papers or possibly a prototype. On the other extreme would be a technology that is already developed to the point that only full-scale implementation is needed. Everything that falls between could be suitable for an ARPA program topic area.

Once a high-impact program has been designed, the next step is to rigorously pressure test and develop a program until it resembles an executable ARPA program.

Applying ARPA Frameworks to Transportation Infrastructure Challenges

By using this framework, any problem or opportunity within transportation infrastructure can be evaluated for its fit as an ARPA-level idea. Expert and stakeholder idea generation is essential to creating an effective portfolio of ARPA-I programs, so idea generators must be armed with this framework and a defined set of focus areas to develop promising program wireframes. An initial set of focus areas for ARPA-I includes safety, climate and resilience, and digitalization, with equity and accessibility as underlying considerations within each focus area.

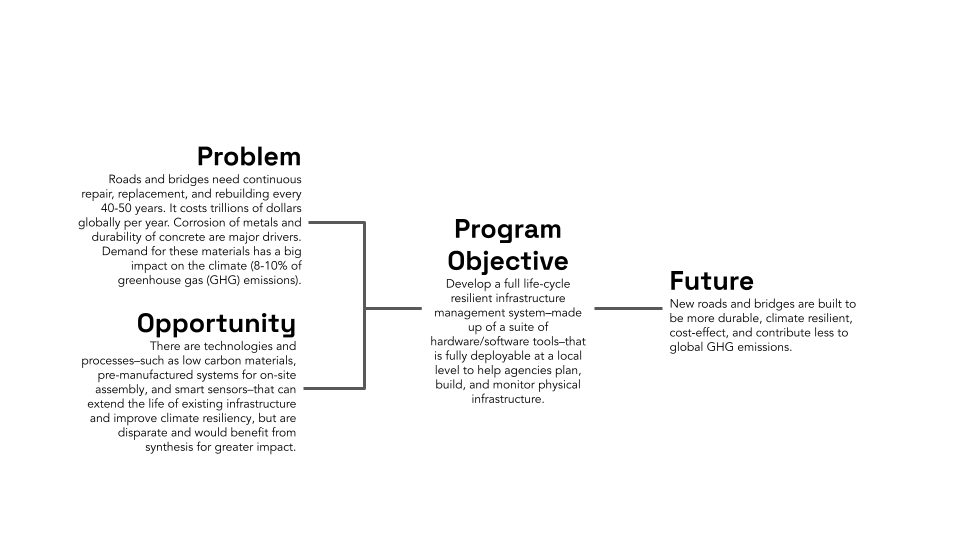

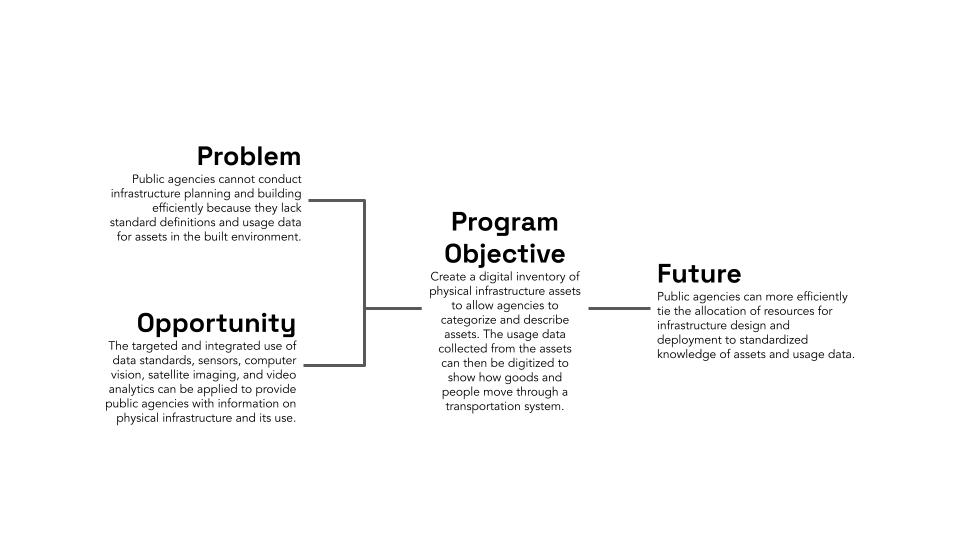

There are hundreds of potential topic areas that ARPA-I could tackle; the two wireframes below represent examples of early-stage program ideas that would benefit from further pressure testing through the program design iteration cycle.

Note: The following wireframes are samples intended to illustrate ARPA ideation and the wireframing process, and do not represent potential research programs or topics under consideration by the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Next-Generation Resilient Infrastructure Management

A Digital Inventory of Physical Infrastructure and Its Uses

Wireframe Development Next Steps

After initial wireframe development, further exploration is needed to pressure test an idea and ensure that it can be developed into a viable program to achieve “moonshot” ambitions. Wireframe authors should consider the following factors when iterating:

- The Heilmeier Catechism questions (see page 14) and whether the wireframe needs to be updated or revised as they seek to answer each of the Heilmeier Catechism questions

- Common challenges wireframes face (see page 11) and whether any of them might be reflected in the wireframe

- The federal, state, and local regulatory landscape and any regulatory factors that will impact the direction of a potential research program

- Whether the problem or technology already receives significant investment from other sources (if there is significant investment from venture capital, private equity, or elsewhere, then it would not be an area of interest for ARPA-I)

- Adjacent areas of work that might inform or affect a potential research program

- The transportation infrastructure sector’s unique challenges and landscape

- How long will it take?

- Existing grant programs and opportunities that might achieve similar goals

Wireframes are intended to be a summary communicative of a larger plan to follow. After further iteration and exploration of the factors outlined above, what was first just a raw program wireframe should develop into more detailed documents. These should include an incisive diagnosis of the problem and evidence and citations validating opportunities to solve it. Together, these components should lead to a plausible program objective as an outcome.

Conclusion

The newly authorized and appropriated ARPA-I presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to apply a model that has been proven successful in developing breakthrough innovations in other sectors to the persistent challenges facing transportation infrastructure.

Individuals and organizations that would work within the ARPA-I network need to have a clear understanding of the unique circumstances, challenges, and opportunities of this sector, as well as how to apply this context and the unique ARPA program ideation model to build high-impact future innovation programs. This community’s engagement is critical to ARPA-I’s success, and the FAS is looking for big thinkers who are willing to take on this challenge by developing bold, innovative ideas.

To sign up for future updates on events, convenings, and other opportunities for you to work in support of ARPA-I programs and partners, click here.

To submit an advanced research program idea, click here.

Advanced Research Priorities in Transportation

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has identified several domains in the transportation and infrastructure space that retain a plethora of unsolved opportunities ripe for breakthrough innovation.

Transportation is not traditionally viewed as a research- and development-led field, with less than 0.7% of the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) annual budget dedicated to R&D activities. The majority of DOT’s R&D funds are disbursed by modal operating administrators mandated to execute on distinct funding priorities rather than a collective, integrated vision of transforming the nation’s infrastructure across 50 states and localities.

Historically, a small percentage of these R&D funds have supported and developed promising, cross-cutting initiatives, such as the Federal Highway Administration’s Exploratory Advanced Research programs deploying artificial intelligence to better understand driver behavior and applying novel data integration techniques to enhance freight logistics. Yet, the scope of these programs has not been designed to scale discoveries into broad deployment, limiting the impact of innovation and technology in transforming transportation and infrastructure in the United States.

As a result, transportation and infrastructure retain a plethora of unaddressed opportunities – from reducing the 40,000 annual vehicle-related fatalities, to improving freight logistics through ports, highways, and rail, to achieving a net zero carbon transportation system, to building infrastructure resilient to the impacts of climate change and severe weather. The reasons for these persistent challenges are numerous: low levels of federal R&D spending, fragmentation across state and local government, risk-averse procurement practices, sluggish commercial markets, and more. When innovations do emerge in this field, they suffer from two valleys of death: one to bring new ideas out of the lab into commercialization, and the second to bring successful deployments of those technologies to scale.

The United States needs a concerted national innovation pipeline designed to fill this gap, exploring early-stage, moonshot research while nurturing breakthroughs from concept to deployment. An Advanced Research Projects Agency-Infrastructure would deliver on this mission. Modeled after the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E), the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Infrastructure (ARPA-I) will operate nimbly and with rigorous program management and deep technical expertise to tackle the biggest infrastructure challenges and overcome entrenched market failures. Solutions would cut across traditional transportation modes (e.g. highways, rail, aviation, maritime, pipelines etc) and would include innovative new infrastructure technologies, materials, systems, capabilities, or processes.

The list of domain areas below reflects priorities for DOT as well as areas where there is significant opportunity for breakthrough innovation:

Key Domain Areas

Metropolitan Safety

Despite progress made since 1975, dramatic reductions in roadway fatalities remain a core, persistent challenge. In 2021, an estimated 42,915 people were killed in motor vehicle crashes, with an estimated 31,785 people killed in the first nine months of 2022. The magnitude of this challenge is articulated in DOT’s most recent National Roadway Safety Strategy, a document that begins with a statement from Secretary Buttigieg: “The status quo is unacceptable, and it is preventable… Zero is the only acceptable number of deaths and serious injuries on our roadways.”

Example topical areas include but are not limited to: urban roadway safety; advanced vehicle driver assistance systems; driver alcohol detection systems; vehicle design; street design; speeding and speed limits; and V2X (vehicle-to-everything) communications and networking technology.

Key Questions for Consideration:

- What steps can be taken to create safer urban mobility spaces for everyone, and what role can technology play in helping create the future we envision?

- What capabilities, systems, and datasets are we missing right now that would unlock more targeted safety interventions?

Rural Safety

Rural communities possess their own unique safety challenges stemming from road design and signage, speed limits, and other factors; and data from the Federal Highway Administration shows that “while only 19% of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, 43% of all roadway fatalities occur on rural roads, and the fatality rate on rural roads is almost 2 times higher than on urban roads.”

Example topical areas include but are not limited to: improved information collection and management systems; design and evaluation tools for two-lane highways and other geometric design decisions; augmented visibility; mitigating or anti-rollover crash solutions; and enhanced emergency response.

Key Questions for Consideration:

- How can rural-based safety solutions address the resource and implementation issues that are faced by local transportation agencies?

- How can existing innovations be leveraged to support the advancement of road safety in rural settings?

Resilient & Climate Prepared Infrastructure

Modern roads, bridges, and transportation are designed to withstand storms that, at the time of their construction, had a probability of occurring once in 100 years; today, climate change has made extreme weather events commonplace. In 2020 alone, the U.S. suffered 22 high-impact weather disasters that each cost over $1 billion in damages. When Hurricane Sandy hit New York City and New Jersey subways with a 14-foot storm surge, millions were left without their primary mode of transportation for a week. Meanwhile, rising sea levels are likely to impact both marine and air transportation, as 13 of the 47 largest U.S. airports have at least one runway within 12 feet of the current sea level. Additionally, the persistent presence of wildfires–which are burning an average of 7 million acres annually across the United States, more than double the average in the 1990s–dramatically reshapes the transportation network in acute ways and causes downstream damage through landslides, flooding, and other natural events.

These trends are likely to continue as climate change exacerbates the intensity and scope of these events. The Department of Transportation is well-positioned to introduce systems-level improvements to the resilience of our nation’s infrastructure.

Example topical areas include but are not limited to: High-performance long-life, advanced materials that increase resiliency and reduce maintenance and reconstruction needs, especially materials for roads, rail, and ports; nature-based protective strategies such as constructed marshes; novel designs for multi-modal hubs or other logistics/supply chain redundancy; efficient and dynamic mechanisms to optimize the relocation of transportation assets; intensive maintenance, preservation, prediction, and degradation analysis methods; and intelligent disaster-resilient infrastructure countermeasures.

Key Questions for Consideration:

- How can we ensure that innovations in this domain yield processes and technologies that are flexible and adaptive enough to ward against future uncertainties related to climate-related disasters?

- How can we factor in the different climate resilience needs of both urban and rural communities?

Digital Infrastructure

Advancing the systems, tools, and capabilities for digital infrastructure to reflect and manage the built environment has the power to enable improved asset maintenance and operations across all levels of government, at scale. Advancements in this field would make using our infrastructure more seamless for transit, freight, pedestrians, and more. Increased data collection from or about vehicle movements, for example, enables user-friendly and demand-responsive traffic management, dynamic curb management for personal vehicles, transit and delivery transportation modes, congestion pricing, safety mapping and targeted interventions, and rail and port logistics. When data is accessible by local departments of transportation and municipalities, it can be harnessed to improve transportation operations and public safety through crash detection as well as to develop Smart Cities and Communities that utilize user-focused mobility services; connected and automated vehicles; electrification across transportation modes, and intelligent, sensor-based infrastructure to measure and manage age-old problems like potholes, air pollution, traffic, parking, and safety.

Example topical areas include but are not limited to: traffic management; curb management; congestion pricing; accessibility; mapping for safety; rail management; port logistics; and transportation system/electric grid coordination.

Key Questions for Consideration:

- How might we leverage data and data systems to radically improve mobility and our transportation system across all modes?

Expediting and Upgrading Construction Methods

Infrastructure projects are fraught with expensive delays and overrun budgets. In the United States, fewer than 1 in 3 contractors report finishing projects on time and within budgets, with 70% citing coordination at the site of construction as the primary reason. In the words of one industry executive, “all [of the nation’s] major projects have cost and schedule issues … the truth is these are very high-risk and difficult projects. Conditions change. It is impossible to estimate it accurately.” But can process improvements and other innovations make construction cheaper, better, faster, and easier?

Example topical areas include but are not limited to: augmented forecasting and modeling techniques; prefabricated or advanced robotic fabrication, modular, and adaptable structures and systems such as bridge sub- and superstructures; real-time quality control and assurance technologies for accelerated construction, materials innovation; new pavement technologies; bioretention; tunneling; underground infrastructure mapping; novel methods for bridge engineering, building information modeling (BIM), coastal, wind, and offshore engineering; stormwater systems; and computational methods in structural engineering, structural sensing, control, and asset management.

Key Questions for Consideration:

- What innovations are more critical to the accelerated construction requirements of the future?

Logistics

Our national economic strength and quality of life depend on the safe and efficient movement of goods throughout our nation’s borders and beyond. Logistic systems—the interconnected webs of businesses, workers, infrastructure processes, and practices that underlie the sorting, transportation, and distribution of goods must operate with efficiency and resilience. . When logistics systems are disrupted by events such as public health crises, extreme weather, workforce challenges, or cyberattacks, goods are delayed, costs increase, and Americans’ daily lives are affected. The Biden Administration issued Executive Order 14017 calling for a review of the transportation and logistics industrial base. DOT released the Freight and Logistics Supply Chain Assessment in February 2022, spotlighting a range of actions that DOT envisions to support a resilient 21st-century freight and logistics supply chain for America.

Topical areas include but are not limited to: freight infrastructure, including ports, roads, airports, and railroads; data and research; rules and regulations; coordination across public and private sectors; and supply chain electrification and intersections with resilient infrastructure.

Key Questions for Consideration: