U.S. Energy Security Compacts: Enhancing American Leadership and Influence with Global Energy Investment

This policy proposal was incubated at the Energy for Growth Hub and workshopped at FAS in May 2024.

Increasingly, U.S. national security priorities depend heavily on bolstering the energy security of key allies, including developing and emerging economies. But U.S. capacity to deliver this investment is hamstrung by critical gaps in approach, capability, and tools.

The new administration should work with Congress to give the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) the mandate and capacity to lead the U.S. interagency in implementing ‘Energy Security Compacts’, bilateral packages of investment and support for allies whose energy security is closely tied to core U.S. priorities. This would require minor amendments to the Millennium Challenge Act of 2003 to add a fourth business line to MCC’s Compact operations and grant the agency authority to coordinate an interagency working group contributing complementary tools and resources.

This proposal presents an opportunity to deliver on global energy security, an issue with broad appeal and major national security benefits. This initiative would strengthen economic partnerships with allies overseas, who consistently rank energy security as a top priority; enhance U.S. influence and credibility in advancing global infrastructure; and expand growing markets for U.S. energy technology. This proposal is built on the foundations and successes of MCC, a signature achievement of the G.W. Bush administration, and is informed by lessons learned from other initiatives launched by previous presidents of both parties.

Challenge and Opportunity

More than ever before, U.S. national security depends on bolstering the energy security of key allies. Core examples include:

- Securing physical energy assets: In countries under immediate or potential military threat, the U.S. may seek to secure vulnerable critical energy infrastructure, restore energy services to local populations, and build a foundation for long-term restoration.

- Countering dependence on geostrategic competitors: U.S. allies’ reliance on geostrategic competitors for energy supply or technologies poses short- and long-term threats to national security. Russia is building large nuclear reactors in major economies including Turkey, Egypt, India, and Bangladesh; has signed agreements to supply nuclear technology to at least 40 countries; and has agreed to provide training and technical assistance to at least another 14. Targeted U.S. support, investment, and commercial diplomacy can head off such dependence by expanding competition.

- Driving economic growth and enduring diplomatic relationships: Many developing and emerging economies face severe challenges in providing reliable, affordable electricity to their populations. This hampers basic livelihoods; constrains economic activity, job creation, and internet access; and contributes to deteriorating economic conditions driving instability and unrest. Of all the constraints analyses conducted by MCC since its creation, roughly half identified energy as a country’s top economic constraint. As emerging economies grow, their economic stability has an expanding influence over global economic performance and security. In coming decades, they will require vast increases in reliable energy to grow their manufacturing and service industries and employ rapidly growing populations. U.S. investment can provide the foundation for market-driven growth and enduring diplomatic partnerships.

- Diversifying supply chains: Many crucial technologies depend on minerals sourced from developing economies without reliable electricity. For example, Zambia accounts for about 4% of global copper supply and would like to scale up production. But recurring droughts have shuttered the country’s major hydropower plant and led to electricity outages, making it difficult for mining operations to continue or grow. Scaling up the mining and processing of key minerals in developing economies will require investment in improving power supply.

The U.S. needs a mechanism that enables quick, efficient, and effective investment and policy responses to the specific concerns facing key allies. Currently, U.S. capacity to deliver such support is hamstrung by key gaps in approach, capabilities, and tools. The most salient challenges include:

A project-by-project approach limits systemic impact: U.S. overseas investment agencies including the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), and the Export-Import Bank (EXIM) are built to advance individual commercial energy transactions across many different countries. This approach has value–but is insufficient in cases where the goal is to secure a particular country’s entire energy system by building strong, competitive markets. That will require approaching the energy sector as a complex and interconnected system, rather than a set of stand-alone transactions.

Diffusion of tools across the interagency hinders coordination. The U.S. has powerful tools to support energy security–including through direct investment, policy support, and technical and commercial assistance–but they are spread across at least nine different agencies. Optimizing deployment will require efficient coordination, incentives for collaboration; and less fragmented engagement with private partners.

Insufficient leverage to incentivize reforms weakens accountability. Ultimately, energy security depends heavily on decisions made by the partner country’s government. In many cases, governments need to make tough decisions and advance key reforms before the U.S. can help crowd in private capital. Many U.S. agencies provide technical assistance to strengthen policy and regulatory frameworks but lack concrete mechanisms to incentivize these reforms or make U.S. funding contingent on progress.

Limited tools supporting vital enabling public infrastructure blocks out private investment. The most challenging bottleneck to modernizing and strengthening a power sector is often not financing new power generation (which can easily attract private investment under the right conditions), but supporting critical enabling infrastructure including grid networks. In most emerging markets, these are public assets, wholly or partially state-owned. However, most U.S. energy finance tools are designed to support only private sector-led investments. This effectively limits their effectiveness to the generation sector, which already attracts far more capital than transmission or distribution.

To succeed, an energy security investment mechanism should:

- Enable investment highly tailored to the specific needs and priorities of partners;

- Provide support across the entire energy sector value chain, strengthening markets to enable greater direct investment by DFC and the private sector;

- Co-invest with partner countries in shared priorities, with strong accountability mechanisms.

Plan of Action

The new administration should work with Congress to give the Millennium Challenge Corporation the mandate to implement ‘Energy Security Compacts’ (ESCs) addressing the primary constraints to energy security in specific countries, and to coordinate the rest of the interagency in contributing relevant tools and resources. This proposal builds on and reflects key lessons learned from previous efforts by administrations of both parties.

Each Energy Security Compact would include the following:

- A process led by MCC and the National Security Council (NSC) to identify priority countries.

- An analysis jointly conducted by MCC and the partner country on the key constraints to energy security.

- Negotiation, led by MCC with support from NSC, of a multi-year Energy Security Compact, anchored by MCC support for a specific set of investments and reforms, and complemented by relevant contributions from the interagency. The Energy Security Compact would define agency-specific responsibilities and include clear objectives and measurable targets.

- Implementation of the Energy Security Compact, led by MCC and NSC. To manage this process, MCC and NSC would co-lead an Interagency Working Group comprising representatives from all relevant agencies.

- Results reporting, based on MCC’s top-ranked reporting process, to the National Security Council and Congress.

This would require the following congressional actions:

- Amend the Millennium Challenge Act of 2003: Grant MCC the expanded mandate to deploy Energy Security Compacts as a fourth business line. This should include language applying more flexible eligibility criteria to ESCs, and broadening the set of countries in which MCC can operate when implementing an ESC. Give MCC the mandate to co-lead an interagency working group with NSC.

- Plus up MCC Appropriation: ESCs can be launched as a pilot project in a few markets. But ultimately, the model’s success and impact will depend on MCC appropriations, including for direct investment and dedicated staff. MCC has a track record of outstanding transparency in evaluating its programs and reporting results.

- Strengthen DFC through reauthorization. The ultimate success of ESCs hinges on DFC’s ability to deploy more capital in the energy sector. DFC’s congressional authorization expires in September 2025, presenting an opportunity to enhance the agency’s reach and impact in energy security. Key recommendations for reauthorization include: 1) Addressing the equity scoring challenge; and 2) Raising DFC’s maximum contingent liability to $100 billion.

- Budget. The initiative could operate under various budget scenarios. The model is specifically designed to be scalable, based on the number of countries with which the U.S. wants to engage. It prioritizes efficiency by drawing on existing appropriations and authorities, by focusing U.S. resources on the highest priority countries and challenges, and by better coordinating the deployment of various U.S. tools.

This proposal draws heavily on the successes and struggles of initiatives from previous administrations of both parties. The most important lessons include:

- From MCC: The Compact model works. Multi-year Compact agreements are an effective way to ensure country buy-in, leadership, and accountability through the joint negotiation process and the establishment of clear goals and metrics. Compacts are also an effective mechanism to support hard infrastructure because they provide multi-year resources.

- From MCC: Investments should be based on rigorous analysis. MCC’s Constraints Analyses identify the most important constraints to economic growth in a given country. That same rigor should be applied to energy security, ensuring that U.S. investments target the highest impact projects, including those with the greatest positive impact on crowding in additional private sector capital.

- From Power Africa: Interagency coordination can work. Coordinating implementation across U.S. agencies is a chronic challenge. But it is essential to ESCs–and to successful energy investment more broadly. The ESC proposal draws on lessons learned from the Power Africa Coordinator’s Office. Specifically, joint-leadership with the NSC focuses effort and ensures alignment with broader strategic priorities. A mechanism to easily transfer funds from the Coordinator’s Office to other agencies incentivizes collaboration, and enables the U.S. to respond more quickly to unanticipated needs. And finally, staffing the office with individuals seconded from relevant agencies ensures that staff understand the available tools, how they can be deployed effectively, and how (and with whom) to work with to ensure success. Legislative language creating a Coordinator’s Office for ESCs can be modeled on language in the Electrify Africa Act of 2015, which created Power Africa’s interagency working group.

Conclusion

The new administration should work with Congress to empower the Millennium Challenge Corporation to lead the U.S. interagency in crafting ‘Energy Security Compacts’. This effort would provide the U.S. with the capability to coordinate direct investment in the energy security of a partner country and contribute to U.S. national priorities including diversifying energy supply chains, investing in the economic stability and performance of rapidly growing markets, and supporting allies with energy systems under direct threat.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

MCC’s model already includes multi-year Compacts targeting major constraints to economic growth. The agency already has the structure and skills to implement Energy Security Compacts in place, including a strong track record of successful investment across many energy sector compacts. MCC enjoys a strong bipartisan reputation and consistently ranks as the world’s most transparent bilateral development donor. Finally, MCC is unique among U.S. agencies in being able to put large-scale grant capital into public infrastructure, a crucial tool for energy sector support–particularly in emerging and developing economies. Co-leading the design and implementation of ESCs with the NSC will ensure that MCC’s technical skills and experience are balanced with NSC’s view on strategic and diplomatic goals.

This proposal supports existing proposed legislative changes to increase MCC’s impact by expanding the set of countries eligible for support. The Millennium Challenge Act of 2003 currently defines the candidate country pool in a way that MCC has determined prevents it from “considering numerous middle-income countries that face substantial threats to their economic development paths and ability to reduce poverty.” Expanding that country pool would increase the potential for impact. Secondly, the country selection process for ESCs should be amended to include strategic considerations and to enable participation by the NSC.

Mobilizing Innovative Financial Mechanisms for Extreme Heat Adaptation Solutions in Developing Nations

Global heat deaths are projected to increase by 370% if direct action is not taken to limit the effects of climate change. The dire implications of rising global temperatures extend across a spectrum of risks, from health crises exacerbated by heat stress, malnutrition, and disease, to economic disparities that disproportionately affect vulnerable communities in the U.S. and in low- and middle-income countries. In light of these challenges, it is imperative to prioritize a coordinated effort at both national and international levels to enhance resilience to extreme heat. This effort must focus on developing and implementing comprehensive strategies to ensure the vulnerable developing countries facing the worst and disproportionate effects of climate change have the proper capacity for adaptation, as wealthier, developed nations mitigate their contributions to climate change.

To address these challenges, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) should mobilize finance through environmental impact bonds focused on scaling extreme heat adaptation solutions. USAID should build upon the success of the SERVIR joint initiative and expand it to include a partnership with NIHHIS to co-develop decision support tools for extreme heat. Additionally, the Bureau for Resilience, Environment, and Food Security (REFS) within the USAID should take the lead in tracking and reporting on climate adaptation funding data. This effort will enhance transparency and ensure that adaptation and mitigation efforts are effectively prioritized. By addressing the urgent need for comprehensive adaptation strategies, we can mitigate the impacts of climate change, increase resilience through adaptation, and protect the most vulnerable communities from the increasing threats posed by extreme heat.

Challenge

Over the past 13 months, temperatures have hit record highs, with much of the world having just experienced their warmest June on record. Berkeley Earth predicts a 95% chance that 2024 will rank as the warmest year in history. Extreme heat drives interconnected impacts across multiple risk areas including: public health; food insecurity; health care system costs; climate migration and the growing transmission of life-threatening diseases.

Thus, as global temperatures continue to rise, resilience to extreme heat becomes a crucial element of climate change adaptation, necessitating a strategic federal response on both domestic and international scales.

Inequitable Economic and Health Impacts

Despite contributing least to global greenhouse gas emissions, low- and middle-income countries experience four times higher economic losses from excess heat relative to wealthier counterparts. The countries likely to suffer the most are those with the most humidity, i.e. tropical nations in the Global South. Two-thirds of global exposure to extreme heat occurs in urban areas in the Global South, where there are fewer resources to mitigate and adapt.

The health impacts associated with increased global extreme heat events are severe, with projections of up to 250,000 additional deaths annually between 2030 and 2050 due to heat stress, alongside malnutrition, malaria, and diarrheal diseases. The direct cost to the health sector could reach $4 billion per year, with 80% of the cost being shouldered by Sub-Saharan Africa. On the whole, low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) in the Global South experience a higher portion of adverse health effects from increasing climate variability despite their minimal contributions to global greenhouse emissions, underscoring a clear global inequity challenge.

This imbalance points to a crucial need for a focus on extreme heat in climate change adaptation efforts and the overall importance of international solidarity in bolstering adaptation capabilities in developing nations. It is more cost-effective to prepare localities for extreme heat now than to deal with the impacts later. However, most communities do not have comprehensive heat resilience strategies or effective early warning systems due to the lack of resources and the necessary data for risk assessment and management — reflected by the fact that only around 16% of global climate financing needs are being met, with far less still flowing to the Global South. Recent analysis from Climate Policy Initiative, an international climate policy research organization, shows that the global adaptation funding gap is widening, as developing countries are projected to require $212 billion per year for climate adaptation through 2030. The needs will only increase without direct policy action.

Opportunity: The Role of USAID in Climate Adaptation and Resilience

As the primary federal agency responsible for helping partner countries adapt to and build resilience against climate change, USAID announced multiple commitments at COP28 to advance climate adaptation efforts in developing nations. In December 2023, following COP28, Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry and USAID Administrator Power announced that 31 companies and partners have responded to the President’s Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience (PREPARE) Call to Action and committed $2.3 billion in additional adaptation finance. Per the State Department’s December 2023 Progress Report on President Biden’s Climate Finance Pledge, this funding level puts agencies on track to reach President Biden’s pledge of working with Congress to raise adaptation finance to $3 billion per year by 2024 as part of PREPARE.

USAID’s Bureau for Resilience, Environment, and Food Security (REFS) leads the implementation of PREPARE. USAID’s entire adaptation portfolio was designed to contribute to PREPARE and align with the Action Plan released in September 2022 by the Biden Administration. USAID has further committed to better integrating adaptation in its Climate Strategy for 2022 to 2030 and established a target to support 500 million people’s adaptation efforts.

This strategy is complemented by USAID’s efforts to spearhead international action on extreme heat at the federal level, with the launch of its Global Sprint of Action on Extreme Heat in March 2024. This program started with the inaugural Global Heat Summit and ran through June 2024, calling on national and local governments, organizations, companies, universities, and youth leaders to take action to help prepare the world for extreme heat, alongside USAID Missions, IFRC and its 191-member National Societies. The executive branch was also advised to utilize the Guidance on Extreme Heat for Federal Agencies Operating Overseas and United States Government Implementing Partners.

On the whole, the USAID approach to climate change adaptation is aimed at predicting, preparing for, and mitigating the impacts of climate change in partner countries. The two main components of USAID’s approach to adaptation include climate risk management and climate information services. Climate risk management involves a “light-touch, staff-led process” for assessing, addressing, and adaptively managing climate risks in non-emergency development funding. The climate information services translate data, statistical analyses, and quantitative outputs into information and knowledge to support decision-making processes. Some climate information services include early warning systems, which are designed to enable governments’ early and effective action. A primary example of a tool for USAID’s climate information services efforts is the SERVIR program, a joint development initiative in partnership with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to provide satellite meteorology information and science to partner countries.

Additionally, as the flagship finance initiative under PREPARE, the State Department and USAID, in collaboration with the U.S. Development Finance Corporation (DFC), have opened an Adaptation Finance Window under the Climate Finance for Development Accelerator (CFDA), which aims to de-risk the development and scaling of companies and investment vehicles that mobilize private finance for climate adaptation.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1: Mobilize private capital through results-based financing such as environmental impact bonds

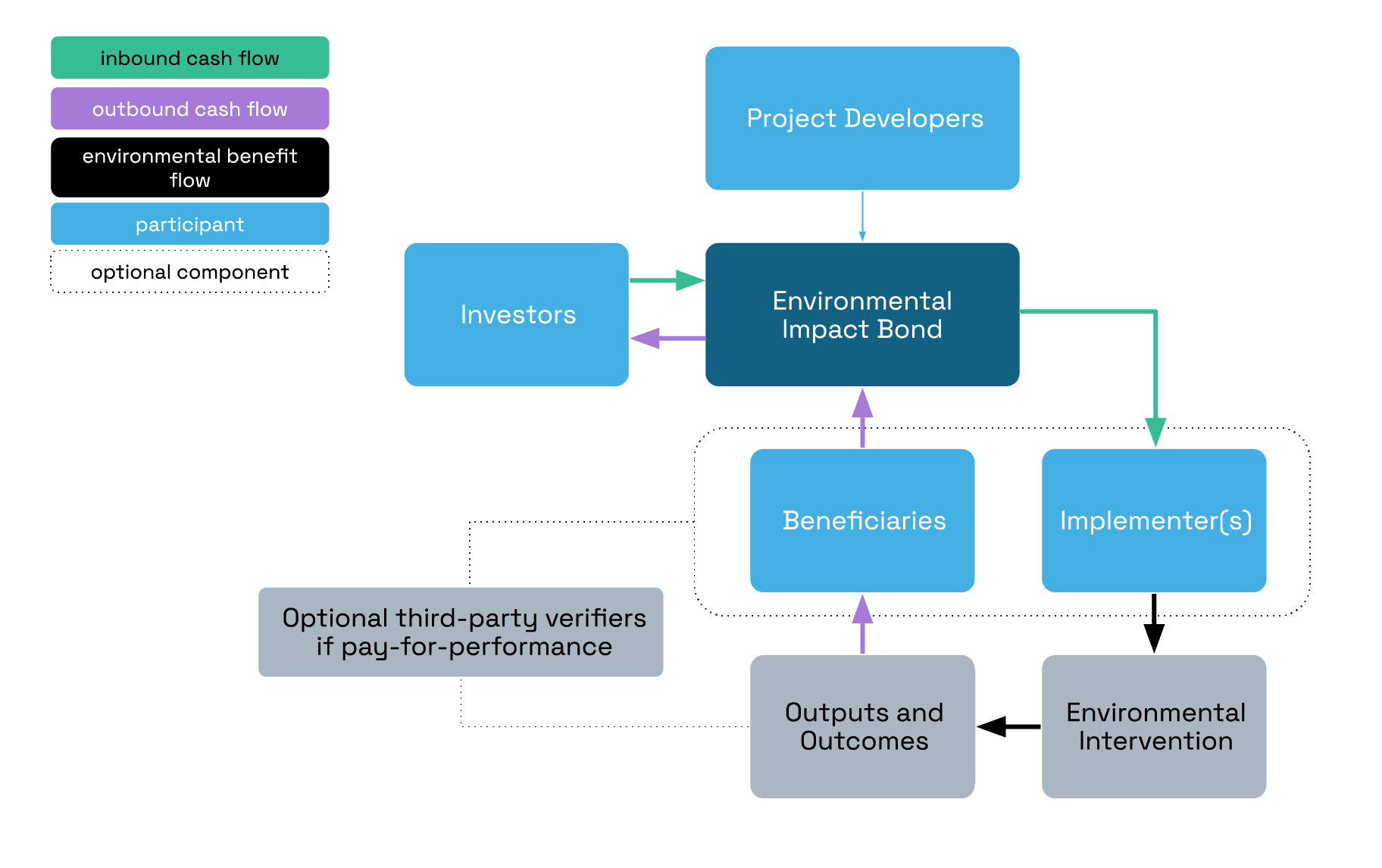

Results-based financing (RBF) has long been a key component of USAID’s development aid strategy, offering innovative ways to mobilize finance by linking payments to specific outcomes. In recent years, Environmental Impact Bonds (EIBs) have emerged as a promising addition to the RBF toolkit and would greatly benefit as a mechanism for USAID to mobilize and scale novel climate adaptation. Thus, in alignment with the PREPARE plan, USAID should launch an EIB pilot focused on extreme heat through the Climate Finance for Development Accelerator (CFDA), a $250 million initiative designed to mobilize $2.5 billion in public and private climate investments by 2030. An EIB piloted through the CFDA can help unlock public and private climate financing that focuses on extreme heat adaptation solutions, which are sorely needed.

With this EIB pilot, the private sector, governments, and philanthropic investors raise the upfront capital and repayment is contingent on the project’s success in meeting predefined goals. By distributing financial risk among stakeholders in the private sector, government, and philanthropy, EIBs encourage investment in pioneering projects that might struggle to attract traditional funding due to their novel or unproven nature. This approach can effectively mobilize the necessary resources to drive climate adaptation solutions.

This approach can effectively mobilize the necessary resources to drive climate adaptation solutions.

Overview of EIB structure, including cash flow (purple and green arrows) and environmental benefits (black arrows).

Adapted from Environmental Impact Bonds: a common framework and looking ahead

The USAID EIB pilot should focus on scaling projects that facilitate uptake and adoption of affordable and sustainable cooling systems such as solar-reflective roofing and other passive cooling strategies. In Southeast Asia alone, annual heat-related mortality is projected to increase by 295% by 2030. Lack of access to affordable and sustainable cooling mechanisms in the wake of record-shattering heat waves affects public health, food and supply chain, and local economies. An EIB that aims to fund and scale solar-reflective roofing (cool roofs) has the potential to generate high impact for the local population by lowering indoor temperature, reducing energy use for air conditioning, and mitigating the heat island effect in surrounding areas. Indonesia, which is home to 46.5 million people at high risk from a lack of access to cooling, has seen notable success in deploying cool roofs/solar-reflective roofing through the Million Cool Roof Challenge, an initiative of the Clean Cooling Collaborative. The country is now planning to scale production capacity of cool roofs and set up its first testing facility for solar-reflective materials to ensure quality and performance. Given Indonesia’s capacity and readiness, an EIB to scale cool roofs in Indonesia can be a force multiplier to see this cooling mechanism reach millions and spur new manufacturing and installation jobs for the local economy.

To mainstream EIBs and other innovative financial instruments, it is essential to pilot and explore more EIB projects. Cool roofs are an ideal candidate for scaling through an EIB due to their proven effectiveness as a climate adaptation solution, their numerous co-benefits, and the relative ease with which their environmental impacts can be measured (such as indoor temperature reductions, energy savings, and heat island index improvements). Establishing an EIB can be complex and time-consuming, but the potential rewards make the effort worthwhile if executed effectively. Though not exhaustive, the following steps are crucial to setting up an environmental impact bond:

Analyze ecosystem readiness

Before launching an environmental impact bond, it’s crucial to conduct an analysis to better understand what capacities already exist among the private and public sectors in a given country to implement something like an EIB. Additionally working with local civil society organizations is important to ensure climate adaptation projects and solutions are centered around the local community.

Determine the financial arrangement, scope, and risk sharing structure

Determine the financial structure of the bond, including the bond amount, interest rate, and maturity date. Establish a mechanism to manage the funds raised through the bond issuance.

Co-develop standardized, scientifically verified impact metrics and reporting mechanism

Develop a robust system for measuring and reporting the environmental impact projects; With key stakeholders and partner countries, define key performance indicators (KPIs) to track and report progress.

USAID has already begun to incubate and pilot innovative financing mechanisms in the global health space through development impact bonds. The Utkrisht Impact Bond, for example, is the world’s first maternal and newborn health impact bond, which aims to reach up to 600,000 pregnant women and newborns in Rajasthan, India. Expanding the use case of this financing mechanism in the climate adaptation sector can further leverage private capital to address critical environmental challenges, drive scalable solutions, and enhance the resilience of vulnerable communities to climate impacts.

Recommendation 2: USAID should expand the SERVIR joint initiative to include a partnership with NIHHIS and co-develop decision support tools such as an intersectional vulnerability map.

Building on the momentum of Administrator Power’s recent announcement at COP28, USAID should expand the SERVIR joint initiative to include a partnership with NOAA, specifically with NIHHIS, the National Integrated Heat Health Information System. NIHHIS is an integrated information system supporting equitable heat resilience, which is an important area that SERVIR should begin to explore. Expanded partnerships could begin with a pilot to map regional extreme heat vulnerability in select Southeast Asian countries. This kind of tool can aid in informing local decision makers about the risks of extreme heat that have many cascading effects on food systems, health, and infrastructure.

Intersectional vulnerabilities related to extreme heat refer to the compounding impacts of various social, economic, and environmental factors on specific groups or individuals. Understanding these intersecting vulnerabilities is crucial for developing effective strategies to address the disproportionate impacts of extreme heat. Some of these intersections include age, income/socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender, and occupation. USAID should partner with NIHHIS to develop an intersectional vulnerability map that can help improve decision-making related to extreme heat. Exploring the intersectionality of extreme heat vulnerabilities is critical to improving local decision-making and helping tailor interventions and policies to where it is most needed. The intersection between extreme heat and health, for example, is an area that is under-analyzed, and work in this area will contribute to expanding the evidence base.

The pilot can be modeled after the SERVIR-Mekong program, which produced 21 decision support tools throughout the span of the program from 2014-2022. The SERVIR-Mekong program led to the training of more than 1,500 people, the mobilization of $500,000 of investment in climate resilience activities, and the adoption of policies to improve climate resilience in the region. In developing these tools, engaging and co-producing with the local community will be essential.

Recommendation 3: USAID REFS and the State Department Office of Foreign Assistance should work together to develop a mechanism to consistently track and report climate funding flow. This also requires USAID and the State Department to develop clear guidelines on the U.S. approach to adaptation tracking and determination of adaptation components.

Enhancing analytical and data collection capabilities is vital for crafting effective and informed responses to the challenges posed by extreme heat. To this end, USAID REFS, along with the State Department Office of Foreign Assistance, should co-develop a mechanism to consistently track and report climate funding flow. Currently, both USAID and the State Department do not consistently report funding data on direct and indirect climate adaptation foreign assistance. As the Department of State is required to report on its climate finance contributions annually for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and biennially for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the two agencies should report on adaptation funding at similarly set, regular interval and make this information accessible to the executive branch and the general public. A robust tracking mechanism can better inform and aid agency officials in prioritizing adaptation assistance and ensuring the US fulfills its commitments and pledges to support global adaptation to climate change.

The State Department Office of Foreign Assistance (State F) is responsible for establishing standard program structures, definitions, and performance indicators, along with collecting and reporting allocation data on State and USAID programs. Within the framework of these definitions and beyond, there is a lack of clear definitions in terms of which foreign assistance projects may qualify as climate projects versus development projects and which qualify as both. Many adaptation projects are better understood on a continuum of adaptation and development activities. As such, this tracking mechanism should be standardized via a taxonomy of definitions for adaptation solutions.

Therefore, State F should create standardized mechanisms for climate-related foreign assistance programs to differentiate and determine the interlinkages between adaptation and mitigation action from the outset in planning, finance, and implementation — and thereby enhance co-benefits. State F relies on the technical expertise of bureaus, such as REFS, and the technical offices within them, to evaluate whether or not operating units have appropriately attributed funding that supports key issues, including indirect climate adaptation.

Further, announced at COP26, PREPARE is considered the largest U.S. commitment in history to support adaptation to climate change in developing nations. The Biden Administration has committed to using PREPARE to “respond to partner countries’ priorities, strengthen cooperation with other donors, integrate climate risk considerations into multilateral efforts, and strive to mobilize significant private sector capital for adaptation.” Co-led by USAID and the U.S. Department of State (State Department), the implementation of PREPARE also involves the Treasury, NOAA, and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). Other U.S. agencies, such as USDA, DOE, HHS, DOI, Department of Homeland Security, EPA, FEMA, U.S. Forest Service, Millennium Challenge Corporation, NASA, and U.S. Trade and Development Agency, will respond to the adaptation priorities identified by countries in National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and nationally determined contributions (NDCs), among others.

As USAID’s REFS leads the implementation of the PREPARE and hosts USAID’s Chief Climate Officer, this office should be responsible for ensuring the agency’s efforts to effectively track and consistently report climate funding data. The two REFS Centers that should lead the implementation of these efforts include the Center for Climate-Positive Development, which advises USAID leadership and supports the implementation of USAID’s Climate Strategy, and the Center for Resilience, which supports efforts to help reduce recurrent crises — such as climate change-induced extreme weather events — through the promotion of risk management and resilience in the USAID’s strategies and programming.

In making standardized processes to prioritize and track the flow of adaptation funds, USAID will be able to more effectively determine its progress towards addressing global climate hazards like extreme heat, while enhancing its ability to deliver innovative finance and private capital mechanisms in alignment with PREPARE. Additionally, standardization will enable both the public and private sectors to understand the possible areas of investment and direct their flows for relevant projects.

USAID uses the Standardized Program Structure and Definitions (SPSD) system — established by State F — to provide a common language to describe climate change adaptation and resilience programs and therefore enable the comparison and analysis of budget and performance data within a country, regionally or globally. The SPSD system uses the following categories: (1) democracy, human rights, and governance; (2) economic growth; (3) education and social services; (4) health; (5) humanitarian assistance; (6) peace and security; and (7) program development and oversight. Since 2016, climate change has been in the economic growth category and each climate change pillar has separate Program Areas and Elements. The SPSD consists of definitions for foreign assistance programs, providing a common language to describe programs. By utilizing a common language, information for various types of programs can be aggregated within a country, regionally, or globally, allowing for the comparison and analysis of budget and performance data.

Using the SPSD program areas and key issues, USAID categorizes and tracks the funding for its allocations related to climate adaptation as either directly or indirectly addressing climate adaptation. Funding that directly addresses climate adaptation is allocated to the “Climate Change—Adaptation” under SPSD Program Area EG.11 for activities that enhance resilience and reduce the vulnerability to climate change of people, places, and livelihoods. Under this definition, adaptation programs may have the following elements: improving access to science and analysis for decision-making in climate-sensitive areas or sectors; establishing effective governance systems to address climate-related risks; and identifying and disseminating actions that increase resilience to climate change by decreasing exposure or sensitivity or by increasing adaptive capacity. Funding that indirectly addresses climate adaptation is not allocated to a specific SPSD program area. It is funding that is allocated to another SPSD program area and also attributed to the key issue of “Adaptation Indirect,” which is for adaptation activities. The SPSD program area for these activities is not Climate Change—Adaptation, but components of these activities also have climate adaptation effects.

In addition to the SPSD, the State Department and USAID have also identified “key issues” to help describe how foreign assistance funds are used. Key issues are topics of special interest that are not specific to one operating unit or bureau and are not identified, or only partially identified, within the SPSD. As specified in the State Department’s foreign assistance guidance for key issues, “operating units with programs that enhance climate resilience, and/or reduce vulnerability to climate variability and change of people, places, and/or livelihoods are expected to attribute funding to the Adaptation Indirect key issue.”

Operating units use the SPSD and relevant key issues to categorize funding in their operational plans. State guidance requires that any USAID operating unit receiving foreign assistance funding must complete an operational plan each year. The purpose of the operational plan is to provide a comprehensive picture of how the operating unit will use this funding to achieve foreign assistance goals and to establish how the proposed funding plan and programming supports the operating unit, agency, and U.S. government policy priorities. According to the operational plan guidance, State F does an initial screening of these plans.

MDBs play a critical role in bridging the significant funding gap faced by vulnerable developing countries that bear a disproportionate burden of climate adaptation costs—estimated to reach up to 20 percent of GDP for small island nations exposed to tropical cyclones and rising seas. MDBs offer a range of financing options, including direct adaptation investments, green financing instruments, and support for fiscal adjustments to reallocate spending towards climate resilience. To be most sustainably impactful, adaptation support from MDBs should supplement existing aid with conditionality that matches the institutional capacities of recipient countries.

In January 2021, President Biden issued an Executive Order (EO 14008) calling upon federal agencies and others to help domestic and global communities adapt and build resilience to climate change. Shortly thereafter in September 2022, the White House announced the launch of the PREPARE Action Plan, which specifically lays out America’s contribution to the global effort to build resilience to the impacts of the climate crisis in developing countries. Nineteen U.S. departments and agencies are working together to implement the PREPARE Action Plan: State, USAID, Commerce/NOAA, Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Treasury, DFC, Department of Defense (DOD) & U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), International Trade Administration (ITA), Peace Corps, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Energy (DOE), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Department of Transportation (DOT), Health and Human Services (HHS), NASA, Export–Import Bank of the United States (EX/IM), and Department of Interior (DOI).

Congress oversees federal climate financial assistance to lower-income countries, especially through the following actions: (1) authorizing and appropriating for federal programs and multilateral fund contributions, (2) guiding federal agencies on authorized programs and appropriations, and (3) overseeing U.S. interests in the programs. Congressional committees of jurisdiction include the House Committees on Foreign Affairs, Financial Services, Appropriations, and the Senate Committees on Foreign Relations and Appropriations, among others.

Transforming On-Demand Medical Oxygen Infrastructure to Improve Access and Mortality Rates

Summary

Despite the World Health Organization’s (WHO) designation of medical oxygen as an essential medicine in 2017, oxygen is still not consistently available in all care settings. Shortages in medical oxygen, which is essential for surgery, pneumonia, trauma, and other hypoxia conditions in vulnerable populations, existed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and persist today. By one estimate, pre-pandemic, only 20% of patients in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) who needed medical oxygen received it. The pandemic tremendously increased the need for oxygen, further compounding access issues as oxygen became an indispensable treatment. During the peak of the pandemic, dozens of countries faced severe oxygen shortages due to patient surges impacting an already fragile infrastructure.

The core driver of this challenge is not a lack of funding and international attention but rather a lack of infrastructure to buy oxygen, not just equipment. Despite organizations such as Unitaid, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Clinton Health Access Initiative, UNICEF, WHO and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) prioritizing funding and provisions of medical oxygen, many countries still face critical shortages. Even fewer LMICs, such as Brazil, are truly oxygen self-sufficient. A broken and inequitable global oxygen delivery infrastructure inadvertently excludes low-income and rural area representation during the design phase. Furthermore, the current delivery infrastructure is composed of many individual funders and private and public stakeholders who do not work in a coordinated fashion because there is no global governing body to establish global policy, standards, and oversight; identify waste and redundancy; and ensure paths to self-sufficiency. As a result, LMICs are at the mercy of other nations and entities who may withhold oxygen during a crisis or fail to adequately distribute supply. It is time for aid organizations and governments to become more efficient and effective at solving this systemic problem by establishing global governance and investing in and enabling LMICs to become self-sufficient by establishing national infrastructure for oxygen generation, distribution, and delivery.

We propose transforming current interventions by centering the concept known as Oxygen as a Utility (OaaU), which fundamentally reimagines a country’s infrastructure for medical oxygen as a public utility supported by private investment and stable prices to create a functionable, equitable market for a necessary public health good. With the White House Covid Response Team shuttering in the coming months, USAID’s Bureau for Global Health has a unique opportunity to take a global leadership role in spearheading the development of an accessible, affordable oxygen marketplace. USAID should convene a global public-private partnership and governing coalition called the Universal Oxygen Coalition (UOC), pilot the OaaU model in at least two target LMICs (Tanzania and Uttar Pradesh, India), and launch a Medical Oxygen Grand Challenge to enable necessary technological and infrastructure innovation.

Challenge and Opportunity

There is no medical substitute for oxygen, which is used to treat a wide range of acute respiratory distress syndromes, such as pneumonia and pneumothorax in newborns, and noncommunicable diseases, such as asthma, heart failure, and COVID-19. Pneumonia alone is the world’s biggest infectious killer of adults and children, claiming the lives of 2.5 million people, including 740,180 children, in 2019. The COVID-19 pandemic compounded the demand for oxygen, and exposed the lack thereof, with increased death tolls in countries around the world as a result.

For every COVID-19 patient who needs oxygen, there are at least five other patients who also need it, including the 7.2 million children with pneumonia who enter LMIC hospitals each year. [Ehsanur et al, 2021]. Where it is available, there are often improperly balanced oxygen distribution networks, such as high-density areas being overstocked while rural areas or tertiary care settings go underserved. Only 10% of hospitals in LMICs have access to pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy, and those better-resourced hospitals tend to be in larger cities closer to existing oxygen delivery providers.

This widespread lack of access to medical oxygen in LMICs threatens health outcomes and well-being, particularly for rural and low-income populations. The primary obstacle to equitable oxygen access is lack of the necessary digital infrastructure in-country. Digital infrastructure provides insights that enable health system managers and policymakers to effectively establish policy, manage the supply of oxygen to meet needs, and coordinate work across a complex supply chain composed of various independent providers. Until replicable and affordable digital infrastructure is established, LMICs will not have the necessary resources to manage a national oxygen delivery system, forecast demand, plan for adequate oxygen production and procurement, safeguard fair distribution, and ensure sustainable consumption.

Oxygen can be delivered in a number of forms—via concentrators, cylinders, plants, or liquid—and the global marketplace encompasses many manufacturers and distributors selling in multiple nations. Most oxygen providers are for-profit organizations, which are not commercially incentivized to collaborate to achieve equal oxygen access, despite good intentions. Many of these same manufacturers also sell medical devices to regulate or deliver oxygen to patients, yet maintaining the equipment across a distributed network remains a challenge. These devices are complex and costly, and there are often few trained experts in-country to repair broken devices. Instead of recycling or repairing devices, healthcare providers are often forced to discard broken equipment and purchase new ones, contributing to greater landfill waste and compounding health concerns for those who live nearby.

Common contributing causes for fragmented oxygen delivery systems in LMICs include:

- No national digital infrastructure to connect, track, and monitor medical oxygen supply and utilization, like an electrical utility to forecast demand and ensure reliable service delivery.

- No centralized way to monitor manufacturers, distributors, and the various delivery providers to ensure coordination and compliance with local policy.

- In many cases, no established local policy for oxygen and healthcare regulation or no means to enforce local policy.

- Lack of purchasing options for healthcare providers, who are often forced to buy whichever oxygen devices are available versus the type of source oxygen that best fits their needs (i.e., concentrator or liquid) due to cumbersome tender systems and lack of coordination across markets.

- Lack of trained experts to maintain and repair devices, including limited national standardized certification programs, resulting in the premature disposal of costly medical devices contributing to waste issues. Further, lack of maintenance fuels the vicious cycle of LMICs requiring more regular funding to buy oxygen devices, which can increase reliance on third parties to sustain oxygen needs rather than domestic demand and marketplaces.

Medical oxygen investment is a unique opportunity to achieve global health outcomes and localization policy objectives. USAID invested $50 million to expand medical oxygen access through its global COVID-19 response for LMIC partners, but this investment only scratches the surface of what is needed to deliver self-sustainment. In response to oxygen shortages during the peaks of the pandemic, the WHO, UNICEF, the World Bank, and other donors shipped hundreds of thousands of oxygen concentrators to help LMICs deal with the rise in oxygen needs. This influx of resources addressed the interim need but did not solve the persisting healthcare system and underlying oxygen infrastructure problems. In 2021, the World Bank made emergency loans available to LMICs to help them shore up production and infrastructure capabilities, but not enough countries applied for these loans, as the barriers to solve these infrastructure issues are complex, difficult to identify without proper data and digital infrastructure to identify supply chain gaps, and hard to solve with a single cash loan.

Despite heavy attention to the issue of oxygen access in LMICs, current spending does not go far enough to set up sustainable oxygen systems in LMICs. Major access and equity gaps still persist. In short, providing funding alone without a cohesive, integrated industrial strategy cannot solve the root problem of medical oxygen inequality.

USAID recently announced an expanded commitment in Africa and Asia to expand medical oxygen access, including market-shaping activities and partnerships. Since the pandemic began, USAID has directed $112 million in funding for medical oxygen to 50 countries and is the largest donor to The Global Fund, which has provided the largest international sums of money (more than $600 million) to increase medical oxygen access in over 80 countries. In response to the pandemic’s impacts on LMICs, the ACT-Accelerator (ACT-A) Oxygen Emergency Taskforce, co-chaired by Unitaid and the Wellcome Trust, has provided $700 million worth of oxygen supplies to over 75 countries and catalyzed large oxygen suppliers and NGO leaders to support LMICs and national healthcare ministries. This task force has brought together industry, philanthropy, NGO, and academic leaders. While USAID is not a direct partner, The Global Fund is a primary donor to the task force.

Without a sea change in policy, however, LMICs will continue to lack the support required to fully diagnosis national oxygen supply delivery system bottlenecks and barriers, establish national regulation policies, deploy digital infrastructures, change procurement approaches, enable necessary governance changes, and train in-country experts to ensure a sustained, equitable oxygen supply chain. To help LMICs become self-sufficient, we need to shift away from offering a piecemeal approach (donating money and oxygen supplies) to a holistic approach that includes access to a group of experts , funding for oxygen digital infrastructure systems, aid to develop national policy and governance mechanisms, and support for establishing specialty training and certification programs so that LMICs can self-manage their own medical oxygen supply chain. Such a development policy initiative relies on the Oxygen as a Utility framework, which focuses on creating a functional, equitable market for medical oxygen as a necessary public good. When achieved successfully, OaaU facilitates one fair rate for end-to-end distribution within a country, like other public utilities such as water and electricity.

A fully realized OaaU model within a national economy would integrate and streamline most aspects of oxygen delivery, from production to distribution of both the oxygen and the devices that dispense it, to training of staff on when to administer oxygen, how to use equipment, and equipment maintenance. This proposed new model coordinates industry partners, funders, and country leaders to focus on end-to-end medical oxygen delivery as an affordable, accessible utility rather than an in-kind development good. OaaU centers predictability, affordability, and efficiency for each stakeholder involved in creating sustainable LMIC medical oxygen supply chains. At its core, OaaU is about increasing both access and reliability by providing all types of oxygen at negotiated, market-wide, affordable, and predictable prices through industry partners and local players. This new business model would be sustainable by charging subscription and pay-per-use fees to serve the investment by private sector providers, each negotiated by Ministries of Health to empower them to manage their own country’s oxygen needs. This new model will incorporate each stakeholder in an LMIC’s healthcare system and facilitate an open, market-based negotiation to achieve affordable, self-sufficient medical oxygen supply chains.

Initial investment is needed to create a permanent oxygen infrastructure in each LMIC to digitally transform the tender system from an equipment and service or in-kind aid model to buying oxygen as a utility model. An industry business model transformation of this scale will require multistakeholder effort to include in-country coordination. The current oxygen delivery infrastructure is composed of many individual funders and private and public stakeholders who do not work in a coordinated fashion. At this critical juncture for medical oxygen provision, USAID’s convening power, donor support, and expertise should be leveraged to better direct this spending to create innovative opportunities. The Universal Oxygen Coalition would establish global policy, standards, and oversight; identify waste and redundancy; and ensure viable paths to oxygen self-sufficiency in LMICs. The UOC will act similarly to electric cooperatives, which aggregate supplies to meet electricity demand, ensuring every patient has access to oxygen, on demand, at the point of care, no matter where in the world they live.

Plan of Action

To steward and catalyze OaaU, USAID should leverage its global platform to convene funders, suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, health systems, financial partners, philanthropy, and NGOs and launch a call to action to mobilize resources and bring attention to medical oxygen inequality. USAID’s Bureau for Global Health, along with the its Private Sector Engagement Points of Contact, and the State Department’s Office of Global Partnerships should spearhead the UOC coalition. Using USAID’s Private Sector Engagement Strategy and EDGE fund as a model, USAID can serve as a connector, catalyzer, and lead implementer in reforming the global medical oxygen marketplace. The Bureau for Global Health should organize the initial summit, calls to action, and burgeoning UOC coalition because of its expertise and connections in the field. We anticipate that the UOC would require staff time and resources, which could be funded by a combination of private and philanthropic funding from UOC members in addition to some USAID resources.

To achieve the UOC vision, multiple sources of funding could be leveraged in addition to Congressional appropriation. In 2022, State Department and USAID funding for global health programs, through the Global Health Programs (GHP) account, which represents the bulk of global health assistance, totaled $9.8 billion, an increase of $634 million above the FY21 enacted level. In combination with USAID’s leading investments in The Global Fund, USAID could deploy existing authorities and funding from Development Innovation Ventures’ (DIV) and leverage Grand Challenge models like Saving Lives at Birth to create innovation incentive awards already authorized by Congress, or the newly announced EDGE Fund focused on flexible public-private sector partnerships to direct resources toward achieving equitable oxygen access for all. These transformative investments would also serve established USAID policy priorities like localization. UOC would work with USAID and the Every Breath Counts Initiative to reimagine this persistent problem by bringing essential players—health systems, oxygen suppliers, manufacturers and/or distributors, and financial partners—into a unified holistic approach to ensure reliable oxygen provision and sustainable infrastructure support.

Recommendation 1. USAID’s Bureau for Global Health should convene the Universal Oxygen Coalition Summit to issue an OaaU co-financing call to action and establish a global governing body.

The Bureau for Global Health should organize the summit, convene the UOC coalition, and issue calls to action to fund country pilots of OaaU. The UOC coalition should bring together LMIC governments; local, regional, and global private-sector medical oxygen providers; local service and maintenance companies; equipment manufacturers and distributors; health systems; private and development finance; philanthropy organizations; the global health NGO community; Ministries of Health; and in-country faith-based organizations.

Once fully established, the UOC would invite industry coalition members to join to ensure equal and fair representation across the medical oxygen delivery care continuum. Potential industry members include Air Liquide, Linde, Philips, CHART, Praxair, Gulf Cryo, Air Products, International Futures, AFROX, SAROS, and GCE. Public and multilateral institutions should include the World Bank, World Health Organization, UNICEF, USAID country missions and leaders from the Bureau for Global Health, and selected country Ministries of Health. Funders such as Rockefeller Foundation, Unitaid, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Clinton Health Access Initiative, and Wellcome Trust, as well as leading social enterprises and experts in the oxygen field such as Hewatele and PATH, should also be included.

UOC members would engage and interact with USAID through its Private Sector Engagement Points of Contact, which are within each regional and technical bureau. USAID should designate at least two points of contact from a regional and technical bureau, respectively, to lead engagement with UOC members and country-level partners. While dedicated funds to support the UOC and its management would be required in the long term either from Congress or private finance, USAID may be able to deploy staff from existing budgets to support the initial stand-up process of the coalition.

Progress and commitments already exist to launch the UOC, with Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors planning to bring fiscal sponsorship as well as strategy and planning for the formation of the global coalition to the UOC with PATH providing additional strategic and technical functions for partners. The purpose of the UOC through its fiscal sponsor is to act as the global governing body by establishing global policy, standards, oversight controls, funding coordination, identifying waste & redundancy, setting priorities, acting as advisor and intermediary when needed to ensure LMIC paths to self-sufficiency are available. UOC would oversee and manage country selection, raising funding, and coordination with local Ministries of Health, funders, and private sector providers.

Other responsibilities of the UOC may include:

- Issue feasibility studies to assess technology gaps in target countries. This research would inform future challenges, contracts, prioritization, design, and focus.

- Advise LMICs on identifying barriers and knowing best next steps.

- Establish an official framework of best practices for OaaU that includes core metrics of success and replicable models.

The first UOC Summit will issue a call to action to make new, significant commitments from development banks, philanthropies, and aid agencies to co-finance OaaU pilot programs, build buy-in within target LMICs, and engage in market-shaping activities and infrastructure investments in the medical oxygen supply chain. The Summit could occur on the sidelines of the Global COVID-19 Summit or the United Nations General Assembly. Summit activities and outcomes should include:

- Announce the launch and secure financial commitments from public and private funds for piloting OaaU in at least one national context.

- Identify and prioritize criteria for selecting pilot locations (regions or nations) for OaaU and select the initial country(s) for holistic oxygen self-sufficiency investment.

- Create the UOC Board representing manufacturers, global health experts, LMIC leaders, funders, multilateral institutions, and health providers who are empowered to identify geographic areas most in need of oxygen investment, issue market-specific grants and open innovation competitions, and leverage pooled public and private funds.

- Research, prioritize, and select at least two models of OaaU within a national marketplace to focus attention of all stakeholders on fixing the oxygen marketplace.

Recommendation 2. The UOC should establish country prioritization based on need and readiness and direct raised funds toward pilot programs.

USAID should co-finance an OaaU pilot model through investments in domestic supply chain streamlining and leverage matched funds from development bank, private, and philanthropic dollars. This fund should be used to invest in the development of a holistic oxygen ecosystem starting in Tanzania and in Uttar Pradesh, India, so that these regions are prepared to deliver reliable oxygen supply, catalyzing broad demand, business activity, and economic development.

The objective is to deliver a replicable global reference model for streamlining the supply chain and logistics, eventually leading to equitable oxygen catering to the healthcare needs that can be rolled out in other LMICs and improve lives for the deprived. The above sites are prioritized based on their readiness and need as determined by the 2020 PATH Market Research Study supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. We estimate that $495 million for the pilots in both nations would provide oxygen for 270 million people, which equates to less than $2 per person. The UOC should:

- Invest in local providers: This will generate economic development and high-paying jobs in-country and throughout the supply chain.

- Spur localized innovation and digital transformation: Foster locally driven innovation by in-country and regional systems integrators, especially in digital transformation of oxygen generation, distribution, and delivery. Solutions should include new digital tools for aggregation of supply and demand and real-time command and control to radically improve access to medical oxygen on demand.

- Create an in-country deployment coalition for each pilot country: Because oxygen marketplaces are unique to each context, having a market-based deployment coalition in each country that involves private, public, and social sector partners is critical to coordinating the deployment of resources and maintaining implementation efforts. The deployment coalition could be operated out of or supervised by a USAID Country Mission.

- Provide pilot model funding to enable Ministries of Health and the deployment coalition to streamline and fix supply chains.

- Issue calls to action for interested parties and stakeholders to submit plans to address both the immediate medical oxygen needs in the country of choice and the long-term infrastructure barriers. These plans could help inform strategy for deploying resources and making oxygen infrastructure investments.

This effort will result in a sustainable oxygen grid in LMICs to produce revenue via subscription and pay-per-use model, reducing the need for aid organization or donor procurement investment on an annual basis. To create the conditions for OaaU, the UOC will need to make a one-time investment to create infrastructure that can provide the volume of oxygen a country needs to become oxygen self-sufficient. This investment should be backed by the World Bank via volume usage guarantees similar to volume usage guarantees for electricity per country. The result will shift the paradigm from buying equipment to buying oxygen.

Recommendation 3. The UOC and partner agencies should launch the Oxygen Access Grand Challenge to invest in innovations to reduce costs, improve maintenance, and enhance supply chain competition in target countries.

We envision the creation of a replicable solution for a self-sustaining infrastructure that can then serve as a global reference model for how best to streamline the oxygen supply chain through improved infrastructure, digital transformation, and logistics coordination. Open innovation would be well-suited to priming this potential market for digital and infrastructure tools that do not yet exist. UOC should aim to catalyze a more inclusive, dynamic, and sustainable oxygen ecosystem of public- and private-sector stakeholders.

The Grand Challenge platform could leverage philanthropic and private sector resources and investment. However, we also recommend that USAID deploy some capital ($20 million over four years) for the prize purse focused on outcomes-based technologies that could be deployed in LMICs and new ideas from a diverse global pool of applicants. We recommend the Challenge focus on the creation of digital public goods that will be the digital “command and control” backbone of a OaaU in-country. This would allow a country’s government and healthcare system to know their own status of oxygen supply per a country grid and which clinic used how much oxygen in real time and bill accordingly. Such tools do not yet exist at affordable, accessible levels in LMICs. However, USAID and its UOC partners should scope and validate the challenge’s core criteria and problems, as they may differ depending on the target countries selected.

Activities to support the Challenge should include:

- Assessing technology and cost gaps in target partner countries in healthcare infrastructure, with a particular focus on supply chains and oxygen provision. This research would inform the Challenge design and focus.

- Creating partnerships with LMICs to implement promising innovations in pilots and secure advanced market commitments from healthcare ministries, the private sector, and multilateral or private financing to ensure viable pathways to scale for solutions.

- Establishing an official framework of best practices for OaaU that includes core metrics of success and replicable models that interested healthcare ministries could use to develop a system in their own nations.

Conclusion

USAID can play a catalytic role in spearheading the creation and sustainment of medical oxygen through a public utility model. Investing in new digital tools for aggregation of supply and demand and real-time command and control to radically improve access to medical oxygen on demand in LMICs can unlock better health outcomes and improve health system performance. By piloting the OaaU model, USAID can prove the sustainability and scalability of a solution that can be a global reference model for streamlining medical oxygen supply chain and logistics. USAID and its partners can begin to create sustained change and truly equitable oxygen access. Through enhancing existing public-private partnerships, USAID can also cement a resilient medical oxygen system better prepared for the next pandemic and better equipped to deliver improved health outcomes.

References

- Pneumonia in Children Statistics – UNICEF DATA

- Ann Danaiya Usher (2021). Medical oxygen crisis: a belated COVID-19 response. The

Lancet, World Report. - Lam F., Stegmuller A.,Chouz V.B., Grahma H.R. (2021). Oxygen systems strengthening as

an intervention to prevent childhood deaths due to pneumonia in low-resource settings:

systematic review, meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness. BMJ Global Health Journals - AD Usher: Medical Oxygen crisis: a belated COVID-19 response (2021) The Lancet Global

Health. - Nair H, Simoes EA, Rudan I, Gessner BD, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Zhang JS et al.

(2013) Global and regional burden of hospital admissions for severe acute lower respiratory

infections in young children in 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet 381: 1380–90.

10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61901-1 - Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE et al. (2012) Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: An updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 379: 2151–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1

- UNEP report. Africa waste management outlook. (2018)

- T Duke, SM Gramham, NN Cherian, AS Ginsburg, M English, S Howie, D Peel, PM Enarson,

IH Wilson, and W Were, the Union Oxygen Systems Working Group (2010) Oxygen is an

essential medicine: A call for international action. - Unitaid press release. COVID-19 emergency impacting more than half a million people in low-

and middle-income countries every day, as demand surges (2021)

The OaaU approach integrates and streamlines most aspects of oxygen delivery, just as integrated power grids grew into public utilities through government investment and public-private partnerships built on technological development to manage them. With an OaaU approach, investments would be made in oxygen digital grid design, build, interoperable connectivity across markets, staff training, demand forecasting and development of a longitudinal sustainable plan. Through this model, an increased number of oxygen suppliers would compete through auctions designed to drive down cost. Governments would receive a lower fixed price in exchange for offering a firm commitment to purchase a pre-established amount of oxygen, services, and equipment to provide oxygen over a long-time horizon. Financial partners guarantee the value of these commitments to reduce the risk that countries will default on their payments, seeking to encourage the increased competition that turns the wheels of this new mechanism. Providing a higher-quality, lower-cost means of obtaining medical oxygen would be a relief for LMICs. Additionally, we would anticipate the government to play a greater role in regulation and oversight which would provide price stability, affordability, and adequate supply for markets—just like how electricity is regulated.

First, oxygen is a complex product that can be generated by concentrators, cylinders, plants, and in liquid oxygen form. For a country to become oxygen self-sufficient, it needs all types of oxygen, and each country has its own unique combination of needs based on healthcare systems, population needs, and existing physical infrastructure. If a country has an excellent transportation system, then delivery of oxygen is the better choice. But if a country has a more rural population and no major highways, then delivery is not a feasible solution.

The oxygen market is competitive and consists of many manufacturers, each of which bring added variations to the way oxygen is delivered. While WHO-UNICEF published minimal technical specifications and guidance for oxygen therapy devices in 2019, there remains variation in how these devices are delivered and the type of data produced in the process. Additionally, oxygen delivery requires an entire system to ensure it safely reaches patients. In most cases, these systems are decentralized and independently run, which further contributes to service and performance variation. Due to layers of complexity, access to oxygen includes multiple challenges in availability, quality, affordability, management, supply, human resources capacity, and safety. National oversight through a digital oxygen utility infrastructure that requires the coordination and participation of the various oxygen delivery stakeholders would address oxygen access issues and enable country self-sustainment.

Given that oxygen provides areturn of US $50 per disability-adjusted life year, medical oxygen investment is a meaningful opportunity for development banks, foreign assistance agencies, and impact investors. The OaaU business model transformation will be a major step toward oxygen availability in the form of oxygen on-demand in LMICs. Reliable, affordable medical oxygen can strengthen the healthcare infrastructure and improve health outcomes. Recent estimates indicate every year about 120–156 million cases of acute lower respiratory infections occur globally in children under five, with approximately 1.4 million resulting in death. More than 95% of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (Nair, 2013; Lui, 2012).

Unlike prior approaches, OaaU is a business model transformation from partial solutions to integrated solutions with all types of oxygen, just like the electricity sector transformed into an integrated grid of all types of electricity supply. From there, the medical facilities will buy oxygen, not equipment—just like you buy amounts of electricity, not a nuclear power plant.

Saving 3.1 Million Lives a Year with a President’s Emergency Plan to Combat Acute Childhood Malnutrition

Summary

Like HIV/AIDS, acute childhood malnutrition is deadly but easily treatable when the right approach is taken. Building on the success of PEPFAR, the Biden-Harris Administration should launch a global cross-agency effort to better fund, coordinate, research, and implement malnutrition prevention and treatment programs to save millions of children’s lives annually and eventually eliminate severe acute malnutrition.

Children with untreated severe acute malnutrition are 9 to 11 times more likely to die than their peers and suffer from permanent setbacks to their neurodevelopment, immune system, and future earnings potential if they survive. Effective programs can treat children for around $60 per child with greater than 90 percent recovery rates. However, globally, only about 25–30 percent of children with moderate and severe acute malnutrition have access to treatment. Every year, 3.1 million children die due to malnutrition-related causes, and 45% of all deaths of children under five are related to malnutrition, making it the leading cause of under-five deaths.

In 2003, a similar predicament existed: the HIV/AIDS epidemic was causing millions of deaths in sub-Saharan Africa and around the world, despite the existence of highly effective treatment and prevention methods. In response, the Bush Administration created the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). PEPFAR has proven a major global health success, saving an estimated 30 million lives since 2003 through over $100 billion in funding.

The Biden-Harris Administration should establish a President’s Emergency Plan for Acute Childhood Malnutrition (PEPFAM) in the Office of Global Food Security at the State Department to clearly elevate the problem of acute childhood malnutrition, leverage new and existing food security and health programs to serve U.S. national security and humanitarian interests, and save the lives of up to 3.1 million children around the world, every year. PEPFAM could serve as a catalytic initiative to harmonize the fight against malnutrition and direct currently fragmented resources toward greater impact.

Challenge and Opportunity

United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2.2 outlines goals for reducing acute malnutrition, ambitiously targeting global rates of 5 percent by 2025 and 3 percent (a “virtual elimination”) by 2030. Due to climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, and conflicts like the war in Ukraine, global rates of malnutrition remain at 8 percent and are forecast to become worse, not better. Globally, 45.4 million children suffer from acute malnutrition, 13.6 million of whom are severely acutely malnourished (SAM). If current trends persist until 2030, an estimated 109 million children will suffer from permanent cognitive or physiological stunting, despite the existence of highly effective and relatively cheap treatment.

Providing life-saving treatment around the world serves a core American value of humanitarianism and helps meet commitments to the SDGs. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) recently announced a commitment to purchase ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), a life-saving food, on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly, demonstrating a prioritization of global food security. Food security is also a priority for the Biden Administration’s approach to national security. The newly released National Security Strategy dedicates an entire section to food insecurity, highlighting the urgency of the problem and calling on the United States and its global partners to work to address acute needs and tackle the extraordinary humanitarian burden posed by malnutrition. The Office of Global Food Security at the U.S. Department of State also prioritizes food security as an issue of national security, leading and coordinating diplomatic engagement in bilateral, multilateral, and regional contexts. At a time when the United States is competing for its vision of a free, open, and prosperous world, addressing childhood malnutrition could serve as a catalyst to achieve the vision articulated in the National Security Strategy and at the State Department.

“People all over the world are struggling to cope with the effects of shared challenges that cross borders—whether it is climate change, food insecurity, communicable diseases, terrorism, energy shortages, or inflation. These shared challenges are not marginal issues that are secondary to geopolitics. They are at the very core of national and international security and must be treated as such.”

U.S. 2022 National Security Strategy

Tested, scalable, and low-cost solutions exist to treat children with acute malnutrition, yet the platform and urgency to deliver interventions at scale does not. Solutions such as community management of acute malnutrition (CMAM), the gold standard approach to malnutrition treatment, and other intentional strategies like biofortification could dramatically lower the burden of global childhood malnutrition. Despite the 3.1 million preventable deaths that occur annually related to childhood malnutrition and the clear threat that food insecurity poses to U.S. national security, we lack an urgent platform to bring these low-cost solutions to bear.